User login

Survey explores mental health, services use in police officers

New research shows that about a quarter of police officers in one large force report past or present mental health problems.

Responding to a survey, 26% of police officers on the Dallas police department screened positive for depression, anxiety, PTSD, or symptoms of suicide ideation or self-harm.

Mental illness rates were particularly high among female officers, those who were divorced, widowed, or separated, and those with military experience.

The study also showed that concerns over confidentiality and stigma may prevent officers with mental illness from seeking treatment.

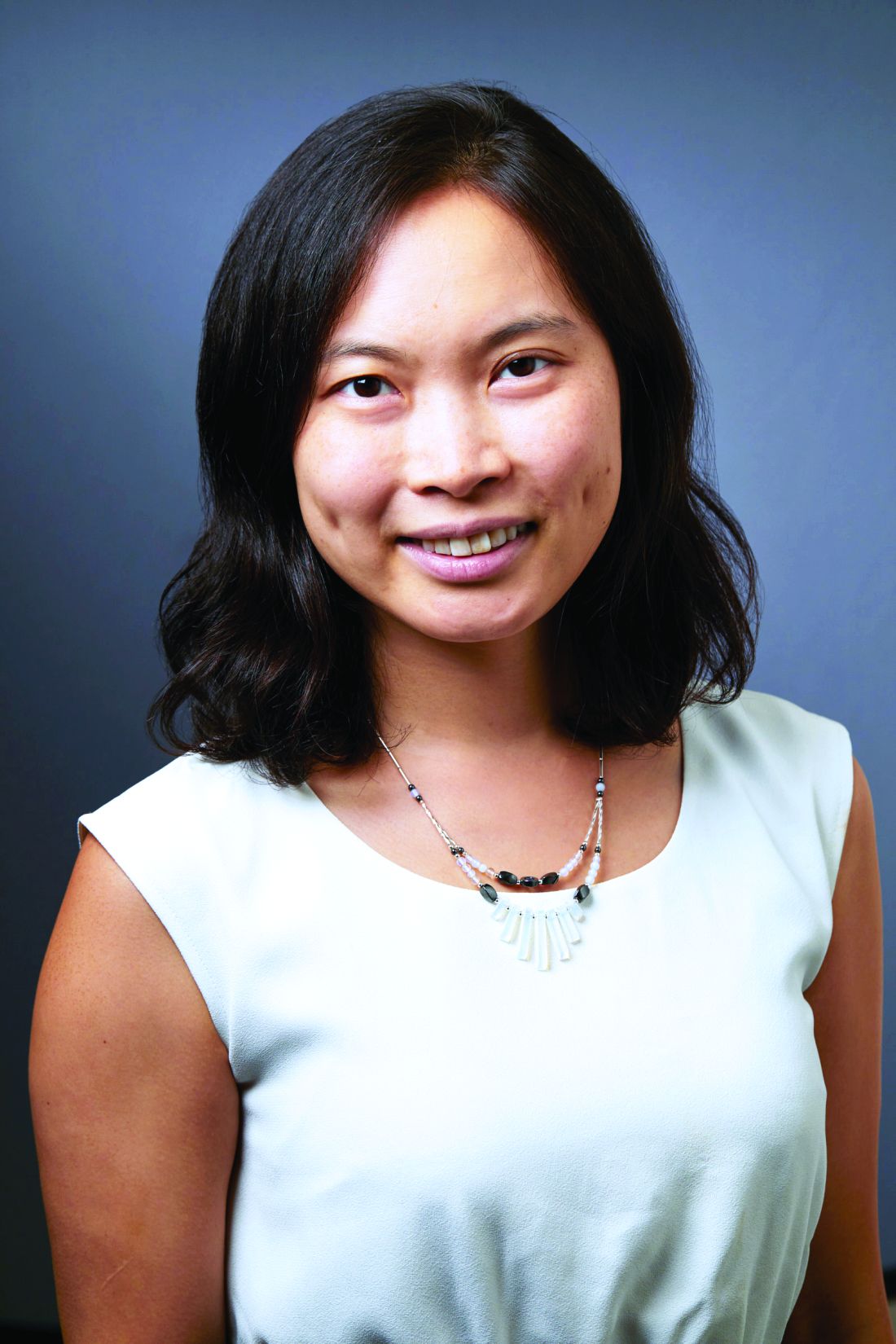

The results underscored the need to identify police officers with psychiatric problems and to connect them to the most appropriate individualized care, author Katelyn K. Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“This is a very hard-to-reach population, and because of that, we need to be innovative in reaching them for services,” she said.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are investigating various aspects of police officers’ well-being, including their nutritional needs and their occupational, physical, and mental health.

The current study included 434 members of the Dallas police department, the ninth largest in the United States. The mean age of the participants was 37 years, 82% were men, and about half were White. The 434 officers represented 97% of those invited to participate (n = 446) and 31% of the total patrol population of the Dallas police department (n = 1,413).

These officers completed a short survey on their smartphone that asked about lifetime diagnoses of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They were also asked whether they experienced suicidal ideation or self-harm during the previous 2 weeks.

Overall, 12% of survey respondents reported having been diagnosed with a mental illness. This, said Jetelina, is slightly lower than the rate reported in the general population.

Study participants who had not currently been diagnosed with a mental illness completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 (GAD-2), and the Primary Care–Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PC-PTSD).

Officers were considered to have a positive result if they had a score of 3 or more (PHQ-2, sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 92%; PC-PTSD-5, sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 85%; GAD-2, sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 83%).

About 26% of respondents had a positive screening for mental illness symptoms, mainly PTSD and depression, which Dr. Jetelina noted is a higher percentage than in the general population.

This rate of mental health symptoms is “high and concerning,” but not surprising because of the work of police officers, which could include attending to sometimes violent car crashes, domestic abuse situations, and armed conflicts, said Dr. Jetelina.

“They’re constantly exposed to traumatic calls for service; they see people on their worst day, 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. That stress and exposure will have a detrimental effect on mental health, and we have to pay more attention to that,” she said.

Dr. Jetelina pointed out that the surveys were completed in January and February 2020, before COVID-19 had become a cause of stress for everyone and before the increase in calls for defunding police amid a resurgence of Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

However, she stressed that racial biases and occupational stress among police officers are “nothing new for them.” For example, in 2016, five Dallas police officers were killed during Black Lives Matter protests because of their race/ethnicity.

More at risk

The study showed that certain subgroups of officers were more at risk for mental illness. After adjustment for confounders, including demographic characteristics, marital status, and educational level, the odds of being diagnosed with a mental illness during the course of one’s life were significantly higher among female officers than male officers (adjusted odds ratio, 3.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-8.68).

Officers who were divorced, widowed, or separated and those who had more experience and held a higher rank were also at greater risk for mental illness.

As well, (aOR, 3.25; 95% CI, 1.38-7.67).

The study also asked participants about use of mental health care services over the past 12 months. About 35% of those who had a current mental health diagnosis and 17% of those who screened positive for mental health symptoms reported using such services.

The study also asked those who screened positive about their interest in seeking such services. After adjustments, officers with suicidal ideation or self-harm were significantly more likely to be interested in getting help, compared with officers who did not report suicidal ideation or self-harm (aOR, 7.66; 95% CI, 1.70-34.48).

Dr. Jetelina was impressed that so many officers were keen to seek help, which “is a big positive,” she said. “It’s just a matter of better detecting who needs the help and better connecting them to medical services that meet their needs.”

Mindfulness exercise

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are conducting a pilot test of the use by police officers of smartwatches that monitor heart rate and oxygen levels. If measurements with these devices reach a predetermined threshold, the officers are “pinged” and are instructed to perform a mindfulness exercise in the field, she said.

Results so far “are really exciting,” said Dr. Jetelina. “Officers have found this extremely helpful and feasible, and so the next step is to test if this truly impacts mental illness over time.”

Routine mental health screening of officers might be beneficial, but only if it’s conducted in a manner “respectful of the officers’ needs and wants,” said Dr. Jetelina.

She pointed out that although psychological assessments are routinely carried out following an extreme traumatic call, such as one involving an officer-involved shooting, the “in-between” calls could have a more severe cumulative impact on mental health.

It’s important to provide officers with easy-to-access services tailored for their individual needs, said Dr. Jetelina.

‘Numb to it’

Eighteen patrol officers also participated in a focus group, during which several themes regarding the use of mental health care services emerged. One theme was the inability of officers to identify when they’re personally experiencing a mental health problem.

Participants said they had become “numb” to the traumatic events on the job, which is “concerning,” Dr. Jetelina said. “They think that having nightmares every week is completely normal, but it’s not, and this needs to be addressed.”

Other themes that emerged from focus groups included the belief that psychologists can’t relate to police stressors; concerns about confidentiality (one sentiment that was expressed was “you’re an idiot” if you “trust this department”); and stigma for officers who seek mental health care (participants talked about “reprisal” from seeing “a shrink,” including being labeled as “a nutter” and losing their job).

Dr. Jetelina noted that some “champion” officers revealed their mental health journey during focus groups, which tended to “open a Pandora’s box” for others to discuss their experience. She said these champions could be leveraged throughout the police department to help reduce stigma.

The study included participants from only one police department, although rigorous data collection allows for generalizability to the entire patrol department, say the authors. Although the study included only brief screens of mental illness symptoms, these short versions of screening tests have high sensitivity and specificity for mental illness in primary care, they noted.

The next step for the researchers is to study how mental illness and symptoms affect job performance, said Dr. Jetelina. “Does this impact excessive use of force? Does this impact workers’ compensation? Does this impact dispatch times, the time it takes for a police officer to respond to [a] 911 call?”

Possible underrepresentation

Anthony T. Ng, MD, regional medical director, East Region Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network in Mansfield, Conn., and member of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Communications, found the study “helpful.”

However, the 26% who tested positive for mental illness may be an “underrepresentation” of the true picture, inasmuch as police officers might minimize or be less than truthful about their mental health status, said Dr. Ng.

Law enforcement has “never been easy,” but stressors may have escalated recently as police forces deal with shortages of staff and jails, said Dr. Ng.

He also noted that officers might face stressors at home. “Evidence shows that domestic violence is quite high – or higher than average – among law enforcement,” he said. “All these things add up.”

Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals should be “aware of the unique challenges” that police officers face and be “proactively involved” in providing guidance and education on mitigating stress, said Dr. Ng.

“You have police officers wearing body armor, so why can’t you give them some training to learn how to have psychiatric or psychological body armor?” he said. But it’s a two-way street; police forces should be open to outreach from mental health professionals. “We have to meet halfway.”

Compassion fatigue

In an accompanying commentary, John M. Violanti, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and environmental health at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said the article helps bring “to the forefront” the issue of the psychological dangers of police work.

There is conjecture as to why police experience mental distress, said Dr. Violanti, who pointed to a study of New York City police suicides during the 1930s that suggested that police have a “social license” for aggressive behavior but are restrained as part of public trust, placing them in a position of “psychological strain.”

“This situation may be reflective of the same situation police find themselves today,” said Dr. Violanti.

“Compassion fatigue,” a feeling of mental exhaustion caused by the inability to care for all persons in trouble, may also be a factor, as could the constant stress that leaves police officers feeling “cynical and isolated from others,” he wrote.

“The socialization process of becoming a police officer is associated with constrictive reasoning, viewing the world as either right or wrong, which leaves no middle ground for alternatives to deal with mental distress,” Dr. Violanti said.

He noted that police officers may abuse alcohol because of stress, peer pressure, isolation, and a culture that approves of alcohol use. “Officers tend to drink together and reinforce their own values.”.

Although no prospective studies have linked police mental health problems with childhood abuse or neglect, some mental health professionals estimate that about 25% of their police clients have a history of childhood abuse or neglect, said Dr. Violanti.

He agreed that mindfulness may help manage stress and increase cognitive flexibility in dealing with trauma and crises.

A possible way to ensure confidentiality is a peer support program that allows distressed officers to first talk privately with a trained and trusted peer officer and to then seek professional help if necessary, said Dr. Violanti.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety. Dr. Jetelina, Dr. Ng, and Dr. Violanti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New research shows that about a quarter of police officers in one large force report past or present mental health problems.

Responding to a survey, 26% of police officers on the Dallas police department screened positive for depression, anxiety, PTSD, or symptoms of suicide ideation or self-harm.

Mental illness rates were particularly high among female officers, those who were divorced, widowed, or separated, and those with military experience.

The study also showed that concerns over confidentiality and stigma may prevent officers with mental illness from seeking treatment.

The results underscored the need to identify police officers with psychiatric problems and to connect them to the most appropriate individualized care, author Katelyn K. Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“This is a very hard-to-reach population, and because of that, we need to be innovative in reaching them for services,” she said.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are investigating various aspects of police officers’ well-being, including their nutritional needs and their occupational, physical, and mental health.

The current study included 434 members of the Dallas police department, the ninth largest in the United States. The mean age of the participants was 37 years, 82% were men, and about half were White. The 434 officers represented 97% of those invited to participate (n = 446) and 31% of the total patrol population of the Dallas police department (n = 1,413).

These officers completed a short survey on their smartphone that asked about lifetime diagnoses of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They were also asked whether they experienced suicidal ideation or self-harm during the previous 2 weeks.

Overall, 12% of survey respondents reported having been diagnosed with a mental illness. This, said Jetelina, is slightly lower than the rate reported in the general population.

Study participants who had not currently been diagnosed with a mental illness completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 (GAD-2), and the Primary Care–Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PC-PTSD).

Officers were considered to have a positive result if they had a score of 3 or more (PHQ-2, sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 92%; PC-PTSD-5, sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 85%; GAD-2, sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 83%).

About 26% of respondents had a positive screening for mental illness symptoms, mainly PTSD and depression, which Dr. Jetelina noted is a higher percentage than in the general population.

This rate of mental health symptoms is “high and concerning,” but not surprising because of the work of police officers, which could include attending to sometimes violent car crashes, domestic abuse situations, and armed conflicts, said Dr. Jetelina.

“They’re constantly exposed to traumatic calls for service; they see people on their worst day, 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. That stress and exposure will have a detrimental effect on mental health, and we have to pay more attention to that,” she said.

Dr. Jetelina pointed out that the surveys were completed in January and February 2020, before COVID-19 had become a cause of stress for everyone and before the increase in calls for defunding police amid a resurgence of Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

However, she stressed that racial biases and occupational stress among police officers are “nothing new for them.” For example, in 2016, five Dallas police officers were killed during Black Lives Matter protests because of their race/ethnicity.

More at risk

The study showed that certain subgroups of officers were more at risk for mental illness. After adjustment for confounders, including demographic characteristics, marital status, and educational level, the odds of being diagnosed with a mental illness during the course of one’s life were significantly higher among female officers than male officers (adjusted odds ratio, 3.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-8.68).

Officers who were divorced, widowed, or separated and those who had more experience and held a higher rank were also at greater risk for mental illness.

As well, (aOR, 3.25; 95% CI, 1.38-7.67).

The study also asked participants about use of mental health care services over the past 12 months. About 35% of those who had a current mental health diagnosis and 17% of those who screened positive for mental health symptoms reported using such services.

The study also asked those who screened positive about their interest in seeking such services. After adjustments, officers with suicidal ideation or self-harm were significantly more likely to be interested in getting help, compared with officers who did not report suicidal ideation or self-harm (aOR, 7.66; 95% CI, 1.70-34.48).

Dr. Jetelina was impressed that so many officers were keen to seek help, which “is a big positive,” she said. “It’s just a matter of better detecting who needs the help and better connecting them to medical services that meet their needs.”

Mindfulness exercise

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are conducting a pilot test of the use by police officers of smartwatches that monitor heart rate and oxygen levels. If measurements with these devices reach a predetermined threshold, the officers are “pinged” and are instructed to perform a mindfulness exercise in the field, she said.

Results so far “are really exciting,” said Dr. Jetelina. “Officers have found this extremely helpful and feasible, and so the next step is to test if this truly impacts mental illness over time.”

Routine mental health screening of officers might be beneficial, but only if it’s conducted in a manner “respectful of the officers’ needs and wants,” said Dr. Jetelina.

She pointed out that although psychological assessments are routinely carried out following an extreme traumatic call, such as one involving an officer-involved shooting, the “in-between” calls could have a more severe cumulative impact on mental health.

It’s important to provide officers with easy-to-access services tailored for their individual needs, said Dr. Jetelina.

‘Numb to it’

Eighteen patrol officers also participated in a focus group, during which several themes regarding the use of mental health care services emerged. One theme was the inability of officers to identify when they’re personally experiencing a mental health problem.

Participants said they had become “numb” to the traumatic events on the job, which is “concerning,” Dr. Jetelina said. “They think that having nightmares every week is completely normal, but it’s not, and this needs to be addressed.”

Other themes that emerged from focus groups included the belief that psychologists can’t relate to police stressors; concerns about confidentiality (one sentiment that was expressed was “you’re an idiot” if you “trust this department”); and stigma for officers who seek mental health care (participants talked about “reprisal” from seeing “a shrink,” including being labeled as “a nutter” and losing their job).

Dr. Jetelina noted that some “champion” officers revealed their mental health journey during focus groups, which tended to “open a Pandora’s box” for others to discuss their experience. She said these champions could be leveraged throughout the police department to help reduce stigma.

The study included participants from only one police department, although rigorous data collection allows for generalizability to the entire patrol department, say the authors. Although the study included only brief screens of mental illness symptoms, these short versions of screening tests have high sensitivity and specificity for mental illness in primary care, they noted.

The next step for the researchers is to study how mental illness and symptoms affect job performance, said Dr. Jetelina. “Does this impact excessive use of force? Does this impact workers’ compensation? Does this impact dispatch times, the time it takes for a police officer to respond to [a] 911 call?”

Possible underrepresentation

Anthony T. Ng, MD, regional medical director, East Region Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network in Mansfield, Conn., and member of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Communications, found the study “helpful.”

However, the 26% who tested positive for mental illness may be an “underrepresentation” of the true picture, inasmuch as police officers might minimize or be less than truthful about their mental health status, said Dr. Ng.

Law enforcement has “never been easy,” but stressors may have escalated recently as police forces deal with shortages of staff and jails, said Dr. Ng.

He also noted that officers might face stressors at home. “Evidence shows that domestic violence is quite high – or higher than average – among law enforcement,” he said. “All these things add up.”

Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals should be “aware of the unique challenges” that police officers face and be “proactively involved” in providing guidance and education on mitigating stress, said Dr. Ng.

“You have police officers wearing body armor, so why can’t you give them some training to learn how to have psychiatric or psychological body armor?” he said. But it’s a two-way street; police forces should be open to outreach from mental health professionals. “We have to meet halfway.”

Compassion fatigue

In an accompanying commentary, John M. Violanti, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and environmental health at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said the article helps bring “to the forefront” the issue of the psychological dangers of police work.

There is conjecture as to why police experience mental distress, said Dr. Violanti, who pointed to a study of New York City police suicides during the 1930s that suggested that police have a “social license” for aggressive behavior but are restrained as part of public trust, placing them in a position of “psychological strain.”

“This situation may be reflective of the same situation police find themselves today,” said Dr. Violanti.

“Compassion fatigue,” a feeling of mental exhaustion caused by the inability to care for all persons in trouble, may also be a factor, as could the constant stress that leaves police officers feeling “cynical and isolated from others,” he wrote.

“The socialization process of becoming a police officer is associated with constrictive reasoning, viewing the world as either right or wrong, which leaves no middle ground for alternatives to deal with mental distress,” Dr. Violanti said.

He noted that police officers may abuse alcohol because of stress, peer pressure, isolation, and a culture that approves of alcohol use. “Officers tend to drink together and reinforce their own values.”.

Although no prospective studies have linked police mental health problems with childhood abuse or neglect, some mental health professionals estimate that about 25% of their police clients have a history of childhood abuse or neglect, said Dr. Violanti.

He agreed that mindfulness may help manage stress and increase cognitive flexibility in dealing with trauma and crises.

A possible way to ensure confidentiality is a peer support program that allows distressed officers to first talk privately with a trained and trusted peer officer and to then seek professional help if necessary, said Dr. Violanti.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety. Dr. Jetelina, Dr. Ng, and Dr. Violanti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New research shows that about a quarter of police officers in one large force report past or present mental health problems.

Responding to a survey, 26% of police officers on the Dallas police department screened positive for depression, anxiety, PTSD, or symptoms of suicide ideation or self-harm.

Mental illness rates were particularly high among female officers, those who were divorced, widowed, or separated, and those with military experience.

The study also showed that concerns over confidentiality and stigma may prevent officers with mental illness from seeking treatment.

The results underscored the need to identify police officers with psychiatric problems and to connect them to the most appropriate individualized care, author Katelyn K. Jetelina, PhD, assistant professor in the department of epidemiology, human genetics, and environmental sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“This is a very hard-to-reach population, and because of that, we need to be innovative in reaching them for services,” she said.

The study was published online Oct. 7 in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are investigating various aspects of police officers’ well-being, including their nutritional needs and their occupational, physical, and mental health.

The current study included 434 members of the Dallas police department, the ninth largest in the United States. The mean age of the participants was 37 years, 82% were men, and about half were White. The 434 officers represented 97% of those invited to participate (n = 446) and 31% of the total patrol population of the Dallas police department (n = 1,413).

These officers completed a short survey on their smartphone that asked about lifetime diagnoses of depression, anxiety, and PTSD. They were also asked whether they experienced suicidal ideation or self-harm during the previous 2 weeks.

Overall, 12% of survey respondents reported having been diagnosed with a mental illness. This, said Jetelina, is slightly lower than the rate reported in the general population.

Study participants who had not currently been diagnosed with a mental illness completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ-2), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 (GAD-2), and the Primary Care–Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PC-PTSD).

Officers were considered to have a positive result if they had a score of 3 or more (PHQ-2, sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 92%; PC-PTSD-5, sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 85%; GAD-2, sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 83%).

About 26% of respondents had a positive screening for mental illness symptoms, mainly PTSD and depression, which Dr. Jetelina noted is a higher percentage than in the general population.

This rate of mental health symptoms is “high and concerning,” but not surprising because of the work of police officers, which could include attending to sometimes violent car crashes, domestic abuse situations, and armed conflicts, said Dr. Jetelina.

“They’re constantly exposed to traumatic calls for service; they see people on their worst day, 8 hours a day, 5 days a week. That stress and exposure will have a detrimental effect on mental health, and we have to pay more attention to that,” she said.

Dr. Jetelina pointed out that the surveys were completed in January and February 2020, before COVID-19 had become a cause of stress for everyone and before the increase in calls for defunding police amid a resurgence of Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

However, she stressed that racial biases and occupational stress among police officers are “nothing new for them.” For example, in 2016, five Dallas police officers were killed during Black Lives Matter protests because of their race/ethnicity.

More at risk

The study showed that certain subgroups of officers were more at risk for mental illness. After adjustment for confounders, including demographic characteristics, marital status, and educational level, the odds of being diagnosed with a mental illness during the course of one’s life were significantly higher among female officers than male officers (adjusted odds ratio, 3.20; 95% confidence interval, 1.18-8.68).

Officers who were divorced, widowed, or separated and those who had more experience and held a higher rank were also at greater risk for mental illness.

As well, (aOR, 3.25; 95% CI, 1.38-7.67).

The study also asked participants about use of mental health care services over the past 12 months. About 35% of those who had a current mental health diagnosis and 17% of those who screened positive for mental health symptoms reported using such services.

The study also asked those who screened positive about their interest in seeking such services. After adjustments, officers with suicidal ideation or self-harm were significantly more likely to be interested in getting help, compared with officers who did not report suicidal ideation or self-harm (aOR, 7.66; 95% CI, 1.70-34.48).

Dr. Jetelina was impressed that so many officers were keen to seek help, which “is a big positive,” she said. “It’s just a matter of better detecting who needs the help and better connecting them to medical services that meet their needs.”

Mindfulness exercise

Dr. Jetelina and colleagues are conducting a pilot test of the use by police officers of smartwatches that monitor heart rate and oxygen levels. If measurements with these devices reach a predetermined threshold, the officers are “pinged” and are instructed to perform a mindfulness exercise in the field, she said.

Results so far “are really exciting,” said Dr. Jetelina. “Officers have found this extremely helpful and feasible, and so the next step is to test if this truly impacts mental illness over time.”

Routine mental health screening of officers might be beneficial, but only if it’s conducted in a manner “respectful of the officers’ needs and wants,” said Dr. Jetelina.

She pointed out that although psychological assessments are routinely carried out following an extreme traumatic call, such as one involving an officer-involved shooting, the “in-between” calls could have a more severe cumulative impact on mental health.

It’s important to provide officers with easy-to-access services tailored for their individual needs, said Dr. Jetelina.

‘Numb to it’

Eighteen patrol officers also participated in a focus group, during which several themes regarding the use of mental health care services emerged. One theme was the inability of officers to identify when they’re personally experiencing a mental health problem.

Participants said they had become “numb” to the traumatic events on the job, which is “concerning,” Dr. Jetelina said. “They think that having nightmares every week is completely normal, but it’s not, and this needs to be addressed.”

Other themes that emerged from focus groups included the belief that psychologists can’t relate to police stressors; concerns about confidentiality (one sentiment that was expressed was “you’re an idiot” if you “trust this department”); and stigma for officers who seek mental health care (participants talked about “reprisal” from seeing “a shrink,” including being labeled as “a nutter” and losing their job).

Dr. Jetelina noted that some “champion” officers revealed their mental health journey during focus groups, which tended to “open a Pandora’s box” for others to discuss their experience. She said these champions could be leveraged throughout the police department to help reduce stigma.

The study included participants from only one police department, although rigorous data collection allows for generalizability to the entire patrol department, say the authors. Although the study included only brief screens of mental illness symptoms, these short versions of screening tests have high sensitivity and specificity for mental illness in primary care, they noted.

The next step for the researchers is to study how mental illness and symptoms affect job performance, said Dr. Jetelina. “Does this impact excessive use of force? Does this impact workers’ compensation? Does this impact dispatch times, the time it takes for a police officer to respond to [a] 911 call?”

Possible underrepresentation

Anthony T. Ng, MD, regional medical director, East Region Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network in Mansfield, Conn., and member of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Communications, found the study “helpful.”

However, the 26% who tested positive for mental illness may be an “underrepresentation” of the true picture, inasmuch as police officers might minimize or be less than truthful about their mental health status, said Dr. Ng.

Law enforcement has “never been easy,” but stressors may have escalated recently as police forces deal with shortages of staff and jails, said Dr. Ng.

He also noted that officers might face stressors at home. “Evidence shows that domestic violence is quite high – or higher than average – among law enforcement,” he said. “All these things add up.”

Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals should be “aware of the unique challenges” that police officers face and be “proactively involved” in providing guidance and education on mitigating stress, said Dr. Ng.

“You have police officers wearing body armor, so why can’t you give them some training to learn how to have psychiatric or psychological body armor?” he said. But it’s a two-way street; police forces should be open to outreach from mental health professionals. “We have to meet halfway.”

Compassion fatigue

In an accompanying commentary, John M. Violanti, PhD, of the department of epidemiology and environmental health at the State University of New York at Buffalo, said the article helps bring “to the forefront” the issue of the psychological dangers of police work.

There is conjecture as to why police experience mental distress, said Dr. Violanti, who pointed to a study of New York City police suicides during the 1930s that suggested that police have a “social license” for aggressive behavior but are restrained as part of public trust, placing them in a position of “psychological strain.”

“This situation may be reflective of the same situation police find themselves today,” said Dr. Violanti.

“Compassion fatigue,” a feeling of mental exhaustion caused by the inability to care for all persons in trouble, may also be a factor, as could the constant stress that leaves police officers feeling “cynical and isolated from others,” he wrote.

“The socialization process of becoming a police officer is associated with constrictive reasoning, viewing the world as either right or wrong, which leaves no middle ground for alternatives to deal with mental distress,” Dr. Violanti said.

He noted that police officers may abuse alcohol because of stress, peer pressure, isolation, and a culture that approves of alcohol use. “Officers tend to drink together and reinforce their own values.”.

Although no prospective studies have linked police mental health problems with childhood abuse or neglect, some mental health professionals estimate that about 25% of their police clients have a history of childhood abuse or neglect, said Dr. Violanti.

He agreed that mindfulness may help manage stress and increase cognitive flexibility in dealing with trauma and crises.

A possible way to ensure confidentiality is a peer support program that allows distressed officers to first talk privately with a trained and trusted peer officer and to then seek professional help if necessary, said Dr. Violanti.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Occupational Health and Safety. Dr. Jetelina, Dr. Ng, and Dr. Violanti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Repurposing cardiovascular drugs for serious mental illness

One of the hottest topics now in psychiatry is the possibility of repurposing long-established cardiovascular medications for treatment of patients with serious mental illness, Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, said at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The appeal is multifold. A huge unmet need exists in psychiatry for new and better treatments with novel mechanisms of action. Many guideline-recommended cardiovascular medications have a long track record, including a well-established safety profile with no surprises, and are available in generic versions. They can be developed for a new indication at minimal cost, noted Dr. De Picker, a psychiatrist at the University of Antwerp (Belgium).

The idea of psychiatric repurposing of drugs originally developed for nonpsychiatric indications is nothing new, she added. Examples include lithium for gout, valproate for epilepsy, and ketamine for anesthesiology.

One hitch in efforts to repurpose cardiovascular medications is that, when psychiatric patients have been included in randomized trials of the drugs’ cardiovascular effects, the psychiatric outcomes often went untallied.

Indeed, the only high-quality randomized trial evidence of psychiatric benefits for any class of cardiovascular medications is for statins, where a modest-sized meta-analysis of six placebo-controlled trials in 339 patients with schizophrenia showed the lipid-lowering agents had benefit for both positive and negative symptoms (Psychiatry Res. 2018 Apr;262:84-93). But that’s not a body of data of sufficient size to be definitive, in Dr. De Picker’s view.

Much of the recent enthusiasm for exploring the potential of cardiovascular drugs for psychiatric conditions comes from hypothesis-generating big data analyses drawn from Scandinavian national patient registries. Danish investigators scrutinized all 1.6 million Danes exposed to six classes of drugs of interest during 2005-2015 and determined that those on long-term statins, low-dose aspirin, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or allopurinol were associated with a decreased rate of new-onset depression, while high-dose aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs were associated with an increased rate, compared with a 30% random sample of the country’s population (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019 Jan;1391:68-77).

Similarly, the Danish group found that continued use of statins, angiotensin agents, or low-dose aspirin was associated with a decreased rate of new-onset bipolar disorder, while high-dose aspirin and other NSAIDs were linked to increased risk (Bipolar Disord. 2019 Aug;[15]:410-8). What these agents have in common, the investigators observed, is that they act on inflammation and potentially on the stress response system.

Meanwhile, Swedish investigators examined the course of 142,691 Swedes with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or nonaffective psychosis during 2005-2016. They determined that, during periods when those individuals were on a statin, calcium channel blocker, or metformin, they had reduced rates of psychiatric hospitalization and self-harm (JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Apr 1;76[4]:382-90).

Scottish researchers analyzed the health records of 144,066 patients placed on monotherapy for hypertension and determined that the lowest risk for hospitalization for a mood disorder during follow-up was in those prescribed an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. The risk was significantly higher in patients on a beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker, and intermediate in those on a thiazide diuretic (Hypertension. 2016 Nov;68[5:1132-8).

“Obviously, this is all at a very macro scale and we have no idea whatsoever what this means for individual patients, number needed to treat, or which type of patients would benefit, but it does provide us with some guidance for future research,” according to Dr. De Picker.

In the meantime, while physicians await definitive evidence of any impact of cardiovascular drugs might have on psychiatric outcomes, abundant data exist underscoring what she called “shockingly high levels” of inadequate management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with serious mental illness. That problem needs to be addressed, and Dr. De Picker offered her personal recommendations for doing so in a manner consistent with the evidence to date suggestive of potential mental health benefits of some cardiovascular medications.

She advised that, for treatment of hypertension in patients with bipolar disorder or major depression, an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor is preferred as first-line. There is some evidence to suggest lipophilic beta-blockers, which cross the blood-brain barrier, improve anxiety symptoms and panic attacks, and prevent memory consolidation in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. But the Scottish data suggest that they may worsen mood disorders.

“I would be careful in using beta-blockers as first-line treatment for hypertension. They’re not in the guidelines for anxiety disorders. British guidelines recommend them to prevent memory consolidation in PTSD, but do not use them as first-line in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder,” she said. As for calcium channel blockers, the jury is still out, with mixed and inconsistent evidence to date as to the impact of this drug class on mental illness outcomes.

She recommended a very low threshold for prescribing statin therapy in patients with serious mental illness in light of the superb risk/benefit ratio for this drug class. In her younger patients, she turns for guidance to an online calculator of an individual’s 10-year risk of a first acute MI or stroke.

Metformin has been shown to be beneficial for addressing the weight gain and other adverse metabolic effects caused by antipsychotic agents, and there is some preliminary evidence of improved psychiatric outcomes in patients with serious mental illness.

Christian Otte, MD, who also spoke at the session, noted that not only do emerging data point to the possibility that cardiovascular drugs might have benefit in terms of psychiatric outcomes, there is also some evidence, albeit mixed, that the converse is true: that is, psychiatric drugs may have cardiovascular benefits. He pointed to a South Korean trial in which 300 patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome and major depression were randomized to 24 weeks of escitalopram or placebo. At median 8.1 years of follow-up, the group that received the SSRI had a 31% relative risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, acute MI, or percutaneous coronary intervention (JAMA. 2018 Jul 24; 320[4]:350–7).

“Potentially independent of their antidepressant effects, some SSRIs’ antiplatelet effects could be beneficial for patients with coronary heart disease, although the jury is still open regarding this question, with evidence in both directions,” said Dr. Otte, professor of psychiatry at Charite University Medical Center in Berlin.

Dr. De Picker offered an example as well: Finnish psychiatrists recently reported that cardiovascular mortality was reduced by an adjusted 38% during periods when 62,250 Finnish schizophrenia patients were on antipsychotic agents, compared with periods of nonuse of the drugs in a national study with a median 14.1 years of follow-up (World Psychiatry. 2020 Feb;19[1]:61-8).

“What they discovered – and this is quite contrary to what we are used to hearing about antipsychotic medication and cardiovascular risk – is that while the number of cardiovascular hospitalizations was not different in periods with or without antipsychotic use, the cardiovascular mortality was quite strikingly reduced when patients were on antipsychotic medication,” she said.

Asked by an audience member whether she personally prescribes metformin, Dr. De Picker replied: “Well, yes, why not? One of the very nice things about metformin is that it is actually a very safe drug, even in the hands of nonspecialists.

“I understand that maybe psychiatrists may not feel very comfortable in starting patients on metformin due to a lack of experience. But there are really only two things you need to take into account. About one-quarter of patients will experience GI side effects – nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort – and this can be reduced by gradually uptitrating the dose, dosing at mealtime, and using an extended-release formulation. And the second thing is that metformin can impair vitamin B12 absorption, so I think, especially in psychiatric patients, it would be good to do an annual measurement of vitamin B12 level and, if necessary, administer intramuscular supplements,” Dr. De Picker said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SOURCE: De Picker L. ECNP 2020. Session EDU.05.

One of the hottest topics now in psychiatry is the possibility of repurposing long-established cardiovascular medications for treatment of patients with serious mental illness, Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, said at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The appeal is multifold. A huge unmet need exists in psychiatry for new and better treatments with novel mechanisms of action. Many guideline-recommended cardiovascular medications have a long track record, including a well-established safety profile with no surprises, and are available in generic versions. They can be developed for a new indication at minimal cost, noted Dr. De Picker, a psychiatrist at the University of Antwerp (Belgium).

The idea of psychiatric repurposing of drugs originally developed for nonpsychiatric indications is nothing new, she added. Examples include lithium for gout, valproate for epilepsy, and ketamine for anesthesiology.

One hitch in efforts to repurpose cardiovascular medications is that, when psychiatric patients have been included in randomized trials of the drugs’ cardiovascular effects, the psychiatric outcomes often went untallied.

Indeed, the only high-quality randomized trial evidence of psychiatric benefits for any class of cardiovascular medications is for statins, where a modest-sized meta-analysis of six placebo-controlled trials in 339 patients with schizophrenia showed the lipid-lowering agents had benefit for both positive and negative symptoms (Psychiatry Res. 2018 Apr;262:84-93). But that’s not a body of data of sufficient size to be definitive, in Dr. De Picker’s view.

Much of the recent enthusiasm for exploring the potential of cardiovascular drugs for psychiatric conditions comes from hypothesis-generating big data analyses drawn from Scandinavian national patient registries. Danish investigators scrutinized all 1.6 million Danes exposed to six classes of drugs of interest during 2005-2015 and determined that those on long-term statins, low-dose aspirin, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or allopurinol were associated with a decreased rate of new-onset depression, while high-dose aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs were associated with an increased rate, compared with a 30% random sample of the country’s population (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019 Jan;1391:68-77).

Similarly, the Danish group found that continued use of statins, angiotensin agents, or low-dose aspirin was associated with a decreased rate of new-onset bipolar disorder, while high-dose aspirin and other NSAIDs were linked to increased risk (Bipolar Disord. 2019 Aug;[15]:410-8). What these agents have in common, the investigators observed, is that they act on inflammation and potentially on the stress response system.

Meanwhile, Swedish investigators examined the course of 142,691 Swedes with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or nonaffective psychosis during 2005-2016. They determined that, during periods when those individuals were on a statin, calcium channel blocker, or metformin, they had reduced rates of psychiatric hospitalization and self-harm (JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Apr 1;76[4]:382-90).

Scottish researchers analyzed the health records of 144,066 patients placed on monotherapy for hypertension and determined that the lowest risk for hospitalization for a mood disorder during follow-up was in those prescribed an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. The risk was significantly higher in patients on a beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker, and intermediate in those on a thiazide diuretic (Hypertension. 2016 Nov;68[5:1132-8).

“Obviously, this is all at a very macro scale and we have no idea whatsoever what this means for individual patients, number needed to treat, or which type of patients would benefit, but it does provide us with some guidance for future research,” according to Dr. De Picker.

In the meantime, while physicians await definitive evidence of any impact of cardiovascular drugs might have on psychiatric outcomes, abundant data exist underscoring what she called “shockingly high levels” of inadequate management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with serious mental illness. That problem needs to be addressed, and Dr. De Picker offered her personal recommendations for doing so in a manner consistent with the evidence to date suggestive of potential mental health benefits of some cardiovascular medications.

She advised that, for treatment of hypertension in patients with bipolar disorder or major depression, an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor is preferred as first-line. There is some evidence to suggest lipophilic beta-blockers, which cross the blood-brain barrier, improve anxiety symptoms and panic attacks, and prevent memory consolidation in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. But the Scottish data suggest that they may worsen mood disorders.

“I would be careful in using beta-blockers as first-line treatment for hypertension. They’re not in the guidelines for anxiety disorders. British guidelines recommend them to prevent memory consolidation in PTSD, but do not use them as first-line in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder,” she said. As for calcium channel blockers, the jury is still out, with mixed and inconsistent evidence to date as to the impact of this drug class on mental illness outcomes.

She recommended a very low threshold for prescribing statin therapy in patients with serious mental illness in light of the superb risk/benefit ratio for this drug class. In her younger patients, she turns for guidance to an online calculator of an individual’s 10-year risk of a first acute MI or stroke.

Metformin has been shown to be beneficial for addressing the weight gain and other adverse metabolic effects caused by antipsychotic agents, and there is some preliminary evidence of improved psychiatric outcomes in patients with serious mental illness.

Christian Otte, MD, who also spoke at the session, noted that not only do emerging data point to the possibility that cardiovascular drugs might have benefit in terms of psychiatric outcomes, there is also some evidence, albeit mixed, that the converse is true: that is, psychiatric drugs may have cardiovascular benefits. He pointed to a South Korean trial in which 300 patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome and major depression were randomized to 24 weeks of escitalopram or placebo. At median 8.1 years of follow-up, the group that received the SSRI had a 31% relative risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, acute MI, or percutaneous coronary intervention (JAMA. 2018 Jul 24; 320[4]:350–7).

“Potentially independent of their antidepressant effects, some SSRIs’ antiplatelet effects could be beneficial for patients with coronary heart disease, although the jury is still open regarding this question, with evidence in both directions,” said Dr. Otte, professor of psychiatry at Charite University Medical Center in Berlin.

Dr. De Picker offered an example as well: Finnish psychiatrists recently reported that cardiovascular mortality was reduced by an adjusted 38% during periods when 62,250 Finnish schizophrenia patients were on antipsychotic agents, compared with periods of nonuse of the drugs in a national study with a median 14.1 years of follow-up (World Psychiatry. 2020 Feb;19[1]:61-8).

“What they discovered – and this is quite contrary to what we are used to hearing about antipsychotic medication and cardiovascular risk – is that while the number of cardiovascular hospitalizations was not different in periods with or without antipsychotic use, the cardiovascular mortality was quite strikingly reduced when patients were on antipsychotic medication,” she said.

Asked by an audience member whether she personally prescribes metformin, Dr. De Picker replied: “Well, yes, why not? One of the very nice things about metformin is that it is actually a very safe drug, even in the hands of nonspecialists.

“I understand that maybe psychiatrists may not feel very comfortable in starting patients on metformin due to a lack of experience. But there are really only two things you need to take into account. About one-quarter of patients will experience GI side effects – nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort – and this can be reduced by gradually uptitrating the dose, dosing at mealtime, and using an extended-release formulation. And the second thing is that metformin can impair vitamin B12 absorption, so I think, especially in psychiatric patients, it would be good to do an annual measurement of vitamin B12 level and, if necessary, administer intramuscular supplements,” Dr. De Picker said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SOURCE: De Picker L. ECNP 2020. Session EDU.05.

One of the hottest topics now in psychiatry is the possibility of repurposing long-established cardiovascular medications for treatment of patients with serious mental illness, Livia De Picker, MD, PhD, said at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The appeal is multifold. A huge unmet need exists in psychiatry for new and better treatments with novel mechanisms of action. Many guideline-recommended cardiovascular medications have a long track record, including a well-established safety profile with no surprises, and are available in generic versions. They can be developed for a new indication at minimal cost, noted Dr. De Picker, a psychiatrist at the University of Antwerp (Belgium).

The idea of psychiatric repurposing of drugs originally developed for nonpsychiatric indications is nothing new, she added. Examples include lithium for gout, valproate for epilepsy, and ketamine for anesthesiology.

One hitch in efforts to repurpose cardiovascular medications is that, when psychiatric patients have been included in randomized trials of the drugs’ cardiovascular effects, the psychiatric outcomes often went untallied.

Indeed, the only high-quality randomized trial evidence of psychiatric benefits for any class of cardiovascular medications is for statins, where a modest-sized meta-analysis of six placebo-controlled trials in 339 patients with schizophrenia showed the lipid-lowering agents had benefit for both positive and negative symptoms (Psychiatry Res. 2018 Apr;262:84-93). But that’s not a body of data of sufficient size to be definitive, in Dr. De Picker’s view.

Much of the recent enthusiasm for exploring the potential of cardiovascular drugs for psychiatric conditions comes from hypothesis-generating big data analyses drawn from Scandinavian national patient registries. Danish investigators scrutinized all 1.6 million Danes exposed to six classes of drugs of interest during 2005-2015 and determined that those on long-term statins, low-dose aspirin, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or allopurinol were associated with a decreased rate of new-onset depression, while high-dose aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs were associated with an increased rate, compared with a 30% random sample of the country’s population (Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019 Jan;1391:68-77).

Similarly, the Danish group found that continued use of statins, angiotensin agents, or low-dose aspirin was associated with a decreased rate of new-onset bipolar disorder, while high-dose aspirin and other NSAIDs were linked to increased risk (Bipolar Disord. 2019 Aug;[15]:410-8). What these agents have in common, the investigators observed, is that they act on inflammation and potentially on the stress response system.

Meanwhile, Swedish investigators examined the course of 142,691 Swedes with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or nonaffective psychosis during 2005-2016. They determined that, during periods when those individuals were on a statin, calcium channel blocker, or metformin, they had reduced rates of psychiatric hospitalization and self-harm (JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Apr 1;76[4]:382-90).

Scottish researchers analyzed the health records of 144,066 patients placed on monotherapy for hypertension and determined that the lowest risk for hospitalization for a mood disorder during follow-up was in those prescribed an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. The risk was significantly higher in patients on a beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker, and intermediate in those on a thiazide diuretic (Hypertension. 2016 Nov;68[5:1132-8).

“Obviously, this is all at a very macro scale and we have no idea whatsoever what this means for individual patients, number needed to treat, or which type of patients would benefit, but it does provide us with some guidance for future research,” according to Dr. De Picker.

In the meantime, while physicians await definitive evidence of any impact of cardiovascular drugs might have on psychiatric outcomes, abundant data exist underscoring what she called “shockingly high levels” of inadequate management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with serious mental illness. That problem needs to be addressed, and Dr. De Picker offered her personal recommendations for doing so in a manner consistent with the evidence to date suggestive of potential mental health benefits of some cardiovascular medications.

She advised that, for treatment of hypertension in patients with bipolar disorder or major depression, an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor is preferred as first-line. There is some evidence to suggest lipophilic beta-blockers, which cross the blood-brain barrier, improve anxiety symptoms and panic attacks, and prevent memory consolidation in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. But the Scottish data suggest that they may worsen mood disorders.

“I would be careful in using beta-blockers as first-line treatment for hypertension. They’re not in the guidelines for anxiety disorders. British guidelines recommend them to prevent memory consolidation in PTSD, but do not use them as first-line in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder,” she said. As for calcium channel blockers, the jury is still out, with mixed and inconsistent evidence to date as to the impact of this drug class on mental illness outcomes.

She recommended a very low threshold for prescribing statin therapy in patients with serious mental illness in light of the superb risk/benefit ratio for this drug class. In her younger patients, she turns for guidance to an online calculator of an individual’s 10-year risk of a first acute MI or stroke.

Metformin has been shown to be beneficial for addressing the weight gain and other adverse metabolic effects caused by antipsychotic agents, and there is some preliminary evidence of improved psychiatric outcomes in patients with serious mental illness.

Christian Otte, MD, who also spoke at the session, noted that not only do emerging data point to the possibility that cardiovascular drugs might have benefit in terms of psychiatric outcomes, there is also some evidence, albeit mixed, that the converse is true: that is, psychiatric drugs may have cardiovascular benefits. He pointed to a South Korean trial in which 300 patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome and major depression were randomized to 24 weeks of escitalopram or placebo. At median 8.1 years of follow-up, the group that received the SSRI had a 31% relative risk reduction in the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, acute MI, or percutaneous coronary intervention (JAMA. 2018 Jul 24; 320[4]:350–7).

“Potentially independent of their antidepressant effects, some SSRIs’ antiplatelet effects could be beneficial for patients with coronary heart disease, although the jury is still open regarding this question, with evidence in both directions,” said Dr. Otte, professor of psychiatry at Charite University Medical Center in Berlin.

Dr. De Picker offered an example as well: Finnish psychiatrists recently reported that cardiovascular mortality was reduced by an adjusted 38% during periods when 62,250 Finnish schizophrenia patients were on antipsychotic agents, compared with periods of nonuse of the drugs in a national study with a median 14.1 years of follow-up (World Psychiatry. 2020 Feb;19[1]:61-8).

“What they discovered – and this is quite contrary to what we are used to hearing about antipsychotic medication and cardiovascular risk – is that while the number of cardiovascular hospitalizations was not different in periods with or without antipsychotic use, the cardiovascular mortality was quite strikingly reduced when patients were on antipsychotic medication,” she said.

Asked by an audience member whether she personally prescribes metformin, Dr. De Picker replied: “Well, yes, why not? One of the very nice things about metformin is that it is actually a very safe drug, even in the hands of nonspecialists.

“I understand that maybe psychiatrists may not feel very comfortable in starting patients on metformin due to a lack of experience. But there are really only two things you need to take into account. About one-quarter of patients will experience GI side effects – nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort – and this can be reduced by gradually uptitrating the dose, dosing at mealtime, and using an extended-release formulation. And the second thing is that metformin can impair vitamin B12 absorption, so I think, especially in psychiatric patients, it would be good to do an annual measurement of vitamin B12 level and, if necessary, administer intramuscular supplements,” Dr. De Picker said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SOURCE: De Picker L. ECNP 2020. Session EDU.05.

FROM ECNP 2020

Divergent COVID-19 mental health impacts seen in Spain and China

Spain and China used very different public health responses to the COVID-19 crisis, and that has had significant consequences in terms of the mental health as well as physical health of the two countries’ citizens, Roger Ho, MD, reported at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Dr. Ho, a psychiatrist at the National University of Singapore, presented a first-of-its-kind cross-cultural comparative study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in two epicenters on opposite sides of the world. A total of 1,539 participants drawn from the general populations in the two countries completed the online National University of Singapore COVID-19 Questionnaire. The survey was conducted in late February/early March in China and in mid-April in Spain, times of intense disease activity in the countries.

The questionnaire assesses knowledge and concerns about COVID, precautionary measures taken in the last 14 days, contact history, and physical symptoms related to COVID in the last 14 days. The pandemic’s psychological impact was evaluated using the Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R). Participants also completed the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress-21 Scale (DASS-21).

Of note, the pandemic has taken a vastly greater physical toll in Spain than China. As of May 5, there were 83,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China, with a population of 1.39 billion, compared with 248,000 in Spain, with a population of 46.9 million. The Spanish case rate of 5,500 per 1 million population was 100 times greater than China’s; the Spanish mortality rate of 585 per million was 185-fold greater.

Mental health findings

Spaniards experienced significantly higher levels of stress and depression as reflected in DASS-21 subscale scores of 14.22 and 8.65, respectively, compared with 7.86 and 6.38, in Chinese respondents. Spanish subjects also reported greater anxiety levels than the Chinese on the DASS-21 anxiety subscale, although not to a statistically significant extent. Yet, counterintuitively, given the DASS-21 results, the pandemic had a greater adverse psychological impact on the Chinese subjects as reflected in their significantly higher average IES-D score of 30.76 versus 27.64 in Spain. Dr. Ho offered a hypothesis as to why: The survey documented that many Chinese respondents felt socially stigmatized, and that their nation had been discriminated against by the rest of the world because the pandemic started in China.

Satisfaction with the public health response

Spanish respondents reported less confidence in their COVID-related medical services.

“This could be due to the rising number of infected health care workers in Spain. In contrast, the Chinese had more confidence in their medical services, probably because the government quickly deployed medical personnel and treated COVID-19 patients at rapidly built hospitals,” according to Dr. Ho.

Spain and other European countries shared four shortcomings in their pandemic response, he continued: lack of personal protective equipment for health care workers, delay in developing response strategies, a shortage of hospital beds, and inability to protect vulnerable elderly individuals from infection in nursing homes.

Experiencing cough, shortness of breath, myalgia, or other physical symptoms potentially associated with COVID-19 within the past 14 days was associated with worse depression, anxiety, and stress scores in both China and Spain. This underscores from a mental health standpoint the importance of rapid and accurate testing for the infection, Dr. Ho said.

Significantly more Spanish respondents felt there was too much unnecessary worry about COVID-19, suggesting a need for better health education regarding the pandemic.

Use of face masks

Consistent use of face masks regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms was far more common in the Chinese epicenter, where, unlike in Spain, this precautionary measure was associated with significantly lower IES-R and DASS-21 scores.

but for the Spanish, wearing a face mask was associated with higher IES-R scores,” Dr. Ho said. “We understand that it is difficult for Europeans to accept the need to use masks for healthy people because mask-wearing suggests vulnerability to sickness and concealment of identity. The Chinese have a collective culture. They believe they should wear a face mask to protect their health and that of other people.”

Dr. Ho reported no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted with coinvestigators at Huaibei (China) Normal University and Complutense University of Madrid.

SOURCE: Ho R. ECNP 2020, Session ISE01.

Spain and China used very different public health responses to the COVID-19 crisis, and that has had significant consequences in terms of the mental health as well as physical health of the two countries’ citizens, Roger Ho, MD, reported at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Dr. Ho, a psychiatrist at the National University of Singapore, presented a first-of-its-kind cross-cultural comparative study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in two epicenters on opposite sides of the world. A total of 1,539 participants drawn from the general populations in the two countries completed the online National University of Singapore COVID-19 Questionnaire. The survey was conducted in late February/early March in China and in mid-April in Spain, times of intense disease activity in the countries.

The questionnaire assesses knowledge and concerns about COVID, precautionary measures taken in the last 14 days, contact history, and physical symptoms related to COVID in the last 14 days. The pandemic’s psychological impact was evaluated using the Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R). Participants also completed the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress-21 Scale (DASS-21).

Of note, the pandemic has taken a vastly greater physical toll in Spain than China. As of May 5, there were 83,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China, with a population of 1.39 billion, compared with 248,000 in Spain, with a population of 46.9 million. The Spanish case rate of 5,500 per 1 million population was 100 times greater than China’s; the Spanish mortality rate of 585 per million was 185-fold greater.

Mental health findings

Spaniards experienced significantly higher levels of stress and depression as reflected in DASS-21 subscale scores of 14.22 and 8.65, respectively, compared with 7.86 and 6.38, in Chinese respondents. Spanish subjects also reported greater anxiety levels than the Chinese on the DASS-21 anxiety subscale, although not to a statistically significant extent. Yet, counterintuitively, given the DASS-21 results, the pandemic had a greater adverse psychological impact on the Chinese subjects as reflected in their significantly higher average IES-D score of 30.76 versus 27.64 in Spain. Dr. Ho offered a hypothesis as to why: The survey documented that many Chinese respondents felt socially stigmatized, and that their nation had been discriminated against by the rest of the world because the pandemic started in China.

Satisfaction with the public health response

Spanish respondents reported less confidence in their COVID-related medical services.

“This could be due to the rising number of infected health care workers in Spain. In contrast, the Chinese had more confidence in their medical services, probably because the government quickly deployed medical personnel and treated COVID-19 patients at rapidly built hospitals,” according to Dr. Ho.

Spain and other European countries shared four shortcomings in their pandemic response, he continued: lack of personal protective equipment for health care workers, delay in developing response strategies, a shortage of hospital beds, and inability to protect vulnerable elderly individuals from infection in nursing homes.

Experiencing cough, shortness of breath, myalgia, or other physical symptoms potentially associated with COVID-19 within the past 14 days was associated with worse depression, anxiety, and stress scores in both China and Spain. This underscores from a mental health standpoint the importance of rapid and accurate testing for the infection, Dr. Ho said.

Significantly more Spanish respondents felt there was too much unnecessary worry about COVID-19, suggesting a need for better health education regarding the pandemic.

Use of face masks

Consistent use of face masks regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms was far more common in the Chinese epicenter, where, unlike in Spain, this precautionary measure was associated with significantly lower IES-R and DASS-21 scores.

but for the Spanish, wearing a face mask was associated with higher IES-R scores,” Dr. Ho said. “We understand that it is difficult for Europeans to accept the need to use masks for healthy people because mask-wearing suggests vulnerability to sickness and concealment of identity. The Chinese have a collective culture. They believe they should wear a face mask to protect their health and that of other people.”

Dr. Ho reported no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted with coinvestigators at Huaibei (China) Normal University and Complutense University of Madrid.

SOURCE: Ho R. ECNP 2020, Session ISE01.

Spain and China used very different public health responses to the COVID-19 crisis, and that has had significant consequences in terms of the mental health as well as physical health of the two countries’ citizens, Roger Ho, MD, reported at the virtual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Dr. Ho, a psychiatrist at the National University of Singapore, presented a first-of-its-kind cross-cultural comparative study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in two epicenters on opposite sides of the world. A total of 1,539 participants drawn from the general populations in the two countries completed the online National University of Singapore COVID-19 Questionnaire. The survey was conducted in late February/early March in China and in mid-April in Spain, times of intense disease activity in the countries.

The questionnaire assesses knowledge and concerns about COVID, precautionary measures taken in the last 14 days, contact history, and physical symptoms related to COVID in the last 14 days. The pandemic’s psychological impact was evaluated using the Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R). Participants also completed the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress-21 Scale (DASS-21).

Of note, the pandemic has taken a vastly greater physical toll in Spain than China. As of May 5, there were 83,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China, with a population of 1.39 billion, compared with 248,000 in Spain, with a population of 46.9 million. The Spanish case rate of 5,500 per 1 million population was 100 times greater than China’s; the Spanish mortality rate of 585 per million was 185-fold greater.

Mental health findings

Spaniards experienced significantly higher levels of stress and depression as reflected in DASS-21 subscale scores of 14.22 and 8.65, respectively, compared with 7.86 and 6.38, in Chinese respondents. Spanish subjects also reported greater anxiety levels than the Chinese on the DASS-21 anxiety subscale, although not to a statistically significant extent. Yet, counterintuitively, given the DASS-21 results, the pandemic had a greater adverse psychological impact on the Chinese subjects as reflected in their significantly higher average IES-D score of 30.76 versus 27.64 in Spain. Dr. Ho offered a hypothesis as to why: The survey documented that many Chinese respondents felt socially stigmatized, and that their nation had been discriminated against by the rest of the world because the pandemic started in China.

Satisfaction with the public health response

Spanish respondents reported less confidence in their COVID-related medical services.

“This could be due to the rising number of infected health care workers in Spain. In contrast, the Chinese had more confidence in their medical services, probably because the government quickly deployed medical personnel and treated COVID-19 patients at rapidly built hospitals,” according to Dr. Ho.

Spain and other European countries shared four shortcomings in their pandemic response, he continued: lack of personal protective equipment for health care workers, delay in developing response strategies, a shortage of hospital beds, and inability to protect vulnerable elderly individuals from infection in nursing homes.

Experiencing cough, shortness of breath, myalgia, or other physical symptoms potentially associated with COVID-19 within the past 14 days was associated with worse depression, anxiety, and stress scores in both China and Spain. This underscores from a mental health standpoint the importance of rapid and accurate testing for the infection, Dr. Ho said.

Significantly more Spanish respondents felt there was too much unnecessary worry about COVID-19, suggesting a need for better health education regarding the pandemic.

Use of face masks

Consistent use of face masks regardless of the presence or absence of symptoms was far more common in the Chinese epicenter, where, unlike in Spain, this precautionary measure was associated with significantly lower IES-R and DASS-21 scores.

but for the Spanish, wearing a face mask was associated with higher IES-R scores,” Dr. Ho said. “We understand that it is difficult for Europeans to accept the need to use masks for healthy people because mask-wearing suggests vulnerability to sickness and concealment of identity. The Chinese have a collective culture. They believe they should wear a face mask to protect their health and that of other people.”

Dr. Ho reported no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted with coinvestigators at Huaibei (China) Normal University and Complutense University of Madrid.

SOURCE: Ho R. ECNP 2020, Session ISE01.

FROM ECNP 2020

Mental illness tied to increased mortality in COVID-19

A psychiatric diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is linked to a significantly increased risk for death, new research shows.

Investigators found that patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and who had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder had a 50% increased risk for a COVID-related death in comparison with COVID-19 patients who had not received a psychiatric diagnosis.

“Pay attention and potentially address/treat a prior psychiatric diagnosis if a patient is hospitalized for COVID-19, as this risk factor can impact the patient’s outcome – death – while in the hospital,” lead investigator Luming Li, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and associate medical director of quality improvement, Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview.

The study was published Sept. 30 in JAMA Network Open.

Negative impact

“We were interested to learn more about the impact of psychiatric diagnoses on COVID-19 mortality, as prior large cohort studies included neurological and other medical conditions but did not assess for a priori psychiatric diagnoses,” said Dr. Li.

“We know from the literature that prior psychiatric diagnoses can have a negative impact on the outcomes of medical conditions, and therefore we tested our hypothesis on a cohort of patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19,” she added.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed data on 1,685 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between Feb. 15 and April 25, 2020, and whose cases were followed to May 27, 2020. The patients (mean age, 65.2 years; 52.6% men) were drawn from the Yale New Haven Health System.

The median follow-up period was 8 days (interquartile range, 4-16 days) .

Of these patients, 28% had received a psychiatric diagnosis prior to hospitalization. (i.e., cancer, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, MI, and/or HIV).

Psychiatric diagnoses were defined in accordance with ICD codes that included mental and behavioral health, Alzheimer’s disease, and self-injury.

Vulnerability to stress