User login

2016 Update on bone health

Prioritize bone health, as osteoporotic fracture is a major source of morbidity and mortality among women. In this article: fracture risk with OC use in perimenopause, data that inform calcium’s role in cardiovascular disease, sarcopenia management, and an emerging treatment.

Most women’s health care providers are aware of recent changes and controversies regarding cervical cancer screening, mammography frequency, and whether a pelvic bimanual exam should be part of our annual well woman evaluation.1 However, I believe one of the most important things we as clinicians can do is be frontline in promoting bone health. Osteoporotic fracture is a major source of morbidity and mortality.2,3 Thus, promoting the maintenance of bone health is a priority in my own practice. It is also one of my many academic interests.

What follows is an update on bone health. In past years, this update has been entitled, “Update on osteoporosis,” but what we are trying to accomplish is fracture reduction. Thus, priorities for bone health consist of recognition of risk, lifestyle and dietary counseling, as well as the use of pharmacologic agents when appropriate. Certain research stands out as informative for your practice:

- a recent study on the risk of fracture with oral contraceptive (OC) use in perimenopause

- 3 just-published studies that inform our understanding of calcium’s role in cardiovascular health

- a review on sarcopenia management

- new data on romosozumab.

Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause

Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Hubbard RA, et al. Oral contraceptive use and fracture risk around the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2016;23(2):166-174.

The use of OCs in women of older reproductive age has increased ever since the cutoff age of 35 years was eliminated.4 Lower doses have continued to be utilized in these "older" women with excellent control of irregular bleeding due to ovulatory dysfunction (and reduction in psychosocial symptoms as well).5

The effect of OC use on risk of fracture remains unclear, and use during later reproductive life may be increasing. To determine the association between OC use during later reproductive life and risk of fracture across the menopausal transition, Scholes and colleagues conducted a population-based case-controlled study in a Pacific Northwest HMO, Group Health Cooperative.

Details of the study

Scholes and colleagues enrolled 1,204 case women aged 45 to 59 years with incident fractures, and 2,275 control women. Potential cases with fracture codes in automated data were adjudicated by electronic health record review. Potential control women without fracture codes were selected concurrently, sampling based on age. Participants received a structured study interview. Using logistic regression, associations between OC use and fracture risk were calculated as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Participation was 69% for cases and 64% for controls. The study sample was 82% white; mean age was 54 years. The most common fracture site for cases was the wrist/forearm (32%). Adjusted fracture risk did not differ between cases and controls for OC use:

- in the 10 years before menopause (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.74-1.11)

- after age 38 years (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.78-1.14)

- over the duration, or

- for other OC exposures.

Related article:

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

Association between fractures and OC use near menopause

The current study does not show an association between fractures near the menopausal transition and OC use in the decade before menopause or after age 38 years. For women considering OC use at these times, fracture risk does not seem to be either reduced or increased.

These results, looking at fracture, seem to be further supported by trials conducted by Gambacciani and colleagues,6 in which researchers randomly assigned irregularly cycling perimenopausal women (aged 40-49 years) to 20 μg ethinyl estradiol OCs or calcium/placebo. Results showed that this low-dose OC use significantly increased bone density at the femoral neck, spine, and other sites relative to control women after 24 months.

In the current Scholes study, the use of OCs in the decade before menopause or after age 38 did not reduce fracture risk in the years around the time of menopause. It is reassuring that their use was not associated with any increased fracture risk.

These findings provide additional clarity and guidance to women and their clinicians at a time of increasing public health concern about fractures. For women who may choose to use OCs during late premenopause (around age 38-48 years), fracture risk around the menopausal transition will not differ from women not choosing this option.

Calcium and calcium supplements: The data continue to grow

Anderson JJ, Kruszka B, Delaney JA, et al. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [published online ahead of print October 11, 2016]. J Am Heart Assoc. pii: e003815.

Billington EO, Bristow SM, Gamble GD, et al. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure: randomised, crossover trial in postmenopausal women [published online ahead of print August 20, 2016]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3744-y.

Crandall CJ, Aragaki AK, LeBoff MS, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and height loss: findings from the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D clinical trial [published online ahead of print August 1, 2016]. Menopause. doi:10.1097 /GME.0000000000000704.

In 2001, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Panel on osteoporosis concluded that calcium intake is crucial to maintain bone mass and should be maintained at 1,000-1,500 mg/day in older adults. The panel acknowledged that the majority of older adults did not meet the recommended intake from dietary sources alone, and therefore would require calcium supplementation. Calcium supplements are one of the most commonly used dietary supplements, and population-based surveys have shown that they are used by the majority of older men and women in the United States.7

More recently results from large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of calcium supplements have been reported, leading to concerns about calcium efficacy for fracture risk and safety. Bolland and colleagues8 reported that calcium supplements increased the rate of cardiovascular events in healthy older women and suggested that their role in osteoporosis management be reconsidered. More recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against calcium supplements for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.9

The association between calcium intake and CVD events

Anderson and colleagues acknowledged that recent randomized data suggest that calcium supplements may be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. Using a longitudinal cohort study, they assessed the association between calcium intake, from both foods and supplements, and atherosclerosis, as measured by coronary artery calcification (CAC).

Details of the study by Anderson and colleagues

The authors studied 5,448 adults free of clinically diagnosed CVD (52% female; age range, 45-84 years) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Baseline total calcium intake was assessed from diet (using a food frequency questionnaire) and calcium supplements (by a medication inventory) and categorized into quintiles based on overall population distribution. Baseline CAC was measured by computed tomography (CT) scan, and CAC measurements were repeated in 2,742 participants approximately 10 years later. Women had higher calcium intakes than men.

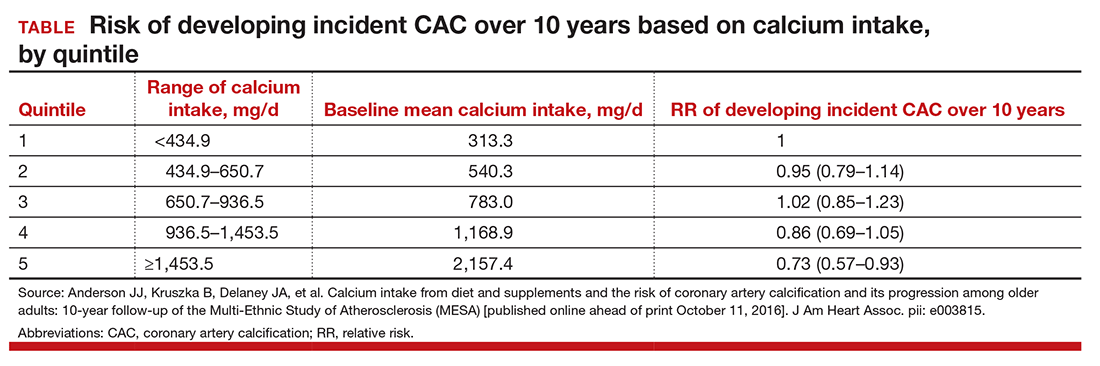

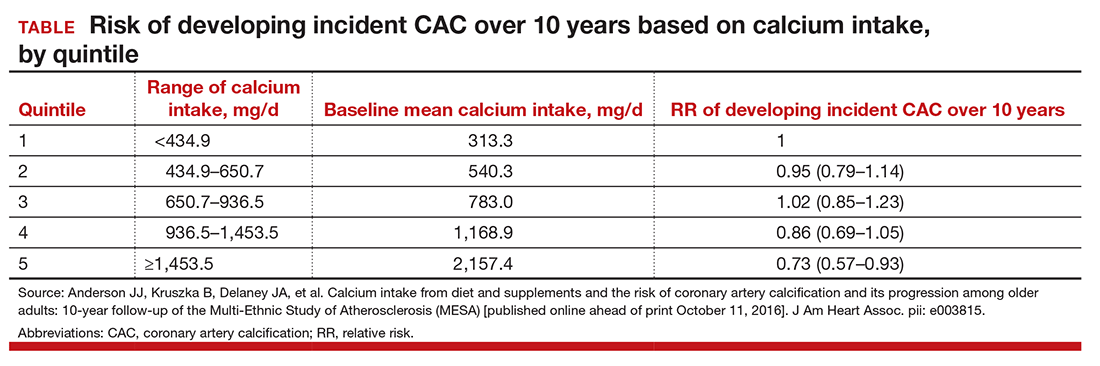

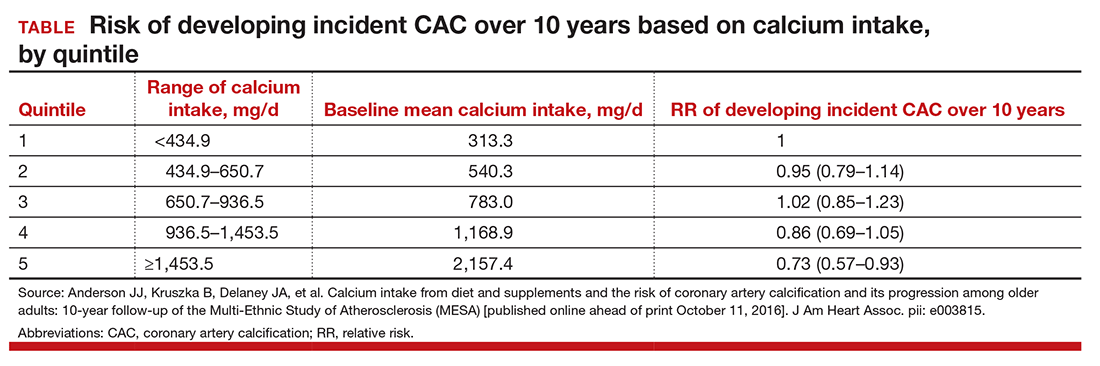

After adjustment for potential confounders, among 1,567 participants without baseline CAC, the relative risk (RR) of developing incident CAC over 10 years, by quintile 1 to 5 of calcium intake is included in the TABLE. After accounting for total calcium intake, calcium supplement use was associated with increased risk for incident CAC (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39). No relation was found between baseline calcium intake and 10-year changes in CAC among those participants with baseline CAC less than zero.

They concluded that high total calcium intake was associated with a decreased risk of incident atherosclerosis over long-term follow-up, particularly if achieved without supplement use. However, calcium supplement use may increase the risk for incident CAC.

Related article:

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

Calcium supplements and blood pressure

Billington and colleagues acknowledged that calcium supplements appear to increase cardiovascular risk but that the mechanism is unknown. They had previously reported that blood pressure declines over the course of the day in older women.10

Details of the study by Billington and colleagues

In this new study the investigators examined the acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure in a randomized controlled crossover trial in 40 healthy postmenopausal women (mean age, 71 years; body mass index [BMI], 27.2 kg/m2). Women attended on 2 occasions, with visits separated by 7 or more days. At each visit, they received either 1 g of calcium as citrate or placebo. Blood pressure and serum calcium concentrations were measured immediately before and 2, 4, and 6 hours after each intervention.

Ionized and total calcium concentrations increased after calcium (P<.0001 vs placebo). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements decreased after both calcium and placebo but significantly less so after calcium (P=.02). The reduction in SBP from baseline was smaller after calcium compared with placebo by 6 mm Hg at 4 hours (P=.036) and by 9 mm Hg at 6 hours (P=.002). The reduction in diastolic blood pressure was similar after calcium and placebo.

These findings indicate that the use of calcium supplements in postmenopausal women attenuates the postbreakfast reduction in SBP by 6 to 9 mm Hg. Whether these changes in blood pressure influence cardiovascular risk requires further study.

Association between calcium, vitamin D, and height loss

Crandall and colleagues looked at the association between calcium and vitamin D supplementation and height loss in 36,282 participants of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D trial.

Details of the study by Crandall and colleagues

The authors performed a post hoc analysis of data from a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate with 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily (CaD) or placebo in postmenopausal women at 40 US clinical centers. Height was measured annually (mean follow-up, 5.9 years) with a stadiometer.

Average height loss was 1.28 mm/yr among participants assigned to CaD, versus 1.26 mm/yr for women assigned to placebo (P=.35). A strong association (P<.001) was observed between age group and height loss. The study authors concluded that, compared with placebo, calcium and vitamin D supplementation used in this trial did not prevent height loss in healthy postmenopausal women.

Adequate calcium is necessary for bone health. While calcium supplementation may not be adequate to prevent fractures, it is also not involved in the inevitable loss of overall height seen in postmenopausal women. Calcium supplementation has been implicated in an increase in CVD. These data seem to indicate that, while calcium supplementation results in higher systolic blood pressure during the day, as well as higher coronary artery calcium scores, greater dietary calcium actually may decrease the incidence of atherosclerosis.

Sarcopenia: Still important, clinical approaches to easily detect it

Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyére O, et al. Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):170.

In last year's update, I reviewed the article by He and colleagues11 on the relationship between sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Sarcopenia, which is the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is important to address in patients. Body composition and muscle strength are directly correlated with bone density, and this is not surprising since bone and muscle share some common hormonal, genetic, nutritional, and lifestyle determinants.12,13 Sarcopenia can be diagnosed via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan looking at lean muscle mass.

The term sarcopenia was first coined by Rosenberg and colleagues in 198914 as a progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass with advancing age. Since then, the definition has expanded to incorporate the notion of impaired muscle strength or physical performance. Sarcopenia is associated with morbidity and mortality from linked physical disability, falls, fractures, poor quality of life, depression, and hospitalization.15

Current research is focusing on nutritional exercise/activity-based and other novel interventions for improving the quality and quantity of skeletal muscle in older people. Some studies demonstrated that resistance training combined with nutritional supplements can improve muscle function.16

Details of the study

Beaudart and colleagues propose some user-friendly and inexpensive methods that can be utilized to assess sarcopenia in real life settings. They acknowledge that in research settings or even specialist clinical settings, DXA or computed tomography (CT) scans are the best assessment of muscle mass.

Anthropometric measurements. In a primary care setting, anthropometric measurement, especially calf circumference and mid-upper arm muscle circumference, correlate with overall muscle mass and reflect both health and nutritional status and predict performance, health, and survival in older people.

However, with advancing age, changes in the distribution of fat and loss of skin elasticity are such that circumference incurs a loss of accuracy and precision in older people. Some studies suggest that an adjustment of anthropometric measurements for age, sex, or BMI results in a better correlation with DXA-measured lean mass.17 Anthropometric measurements are simple clinical prediction tools that can be easily applied for sarcopenia since they offer the most portable, commonly applicable, inexpensive, and noninvasive technique for assessing size, proportions, and composition of the human body. However, their validity is limited when applied to individuals because cutoff points to identify low muscle mass still need to be defined. Still, serial measurements in a patient over time may be valuable.

Related article:

2014 Update on osteoporosis

Handgrip strength, as measured with a dynamometer, appears to be the most widely used method for the measurement of muscle strength. In general, isometric handgrip strength shows a good correlation with leg strength and also with lower extremity power, and calf cross-sectional muscle area. The measurement is easy to perform, inexpensive and does not require a specialist-trained staff.

Standardized conditions for the test include seating the patient in a standard chair with her forearms resting flat on the chair arms. Clinicians should demonstrate the use of the dynamometer and show that gripping very tightly registers the best score. Six measurements should be taken, 3 with each arm. Ideally, patients should be encouraged to squeeze as hard and tightly as possible during 3 to 5 seconds for each of the 6 trials; usually the highest reading of the 6 measurements is reported as the final result. The Jamar dynamometer, or similar hydraulic dynamometer, is the gold standard for this measurement.

Gait speed measurement. The most widely used tool in clinical practice for the assessment of physical performance is the gait speed measurement. The test is highly acceptable for participants and health professionals in clinical settings. No special equipment is required; it needs only a flat floor devoid of obstacles. In the 4-meter gait speed test, men and women with a gait speed of less than 0.8 meters/sec are described as having a poor physical performance. The average extra time added to the consultation by measuring the 4-meter gait speed was only 95 seconds (SD, 20 seconds).

Loss of muscle mass correlates with loss of bone mass as our patients age. In addition, such sarcopenia increases the risk of falls, a significant component of the rising rate of fragility fractures. Anthropometric measures, grip strength, and gait speed are easy, low-cost measures that can identify patients at increased risk.

Romosozumab: An interesting new agent to look forward to

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1532-1543.

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds sclerostin, increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption. Cosman and colleagues enrolled 7,180 postmenopausal women with a T score of -2.5 to -3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck. Participants were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous injections of romosozumab 210 mg or placebo monthly for 12 months. Thereafter, women in each group received subcutaneous denosumab 60 mg for 12 months--administered every 6 months. The coprimary end points were the cumulative incidences of new vertebral fractures at 12 and 24 months. Secondary end points included clinical and nonvertebral fractures.

Details of the study

At 12 months, new vertebral fractures had occurred in 16 of 3,321 women (0.5%) in the romosozumab group, as compared with 59 of 3,322 (1.8%) in the placebo group (representing a 73% lower risk of fracture with romosozumab; P<.001). Clinical fractures had occurred in 58 of 3,589 women (1.6%) in the romosozumab group, as compared with 90 of 3,591 (2.5%) in the placebo group (a 36% lower fracture risk with romosozumab; P = .008). Nonvertebral fractures had occurred in 56 of 3,589 women (1.6%) in the romosozumab group and in 75 of 3,591 (2.1%) in the placebo group (P = .10).

At 24 months, the rates of vertebral fractures were significantly lower in the romosozumab group than in the placebo group after each group made the transition to denosumab (0.6% [21 of 3,325 women] in the romosozumab group vs 2.5% [84 of 3,327 women] in the placebo group, a 75% lower risk with romosozumab; P<.001). Adverse events, including cardiovascular events, osteoarthritis, and cancer, appeared to be balanced between the groups. One atypical femoral fracture and 2 cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw were observed in the romosozumab group.

Lower risk of fracture

Thus, in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, romosozumab was associated with a lower risk of vertebral fracture than placebo at 12 months and, after the transition to denosumab, at 24 months. The lower risk of clinical fracture that was seen with romosozumab was evident at 1 year.

Of note, the effect of romosozumab on the risk of vertebral fracture was rapid, with only 2 additional vertebral fractures (of a total of 16 such fractures in the romosozumab group) occurring in the second 6 months of the first year of therapy. Because vertebral and clinical fractures are associated with increased morbidity and considerable health care costs, a treatment that would reduce this risk rapidly could offer appropriate patients an important benefit.

Romosozumab is a new agent. Though not yet available, it is extremely interesting because it not only decreases bone resorption but also increases bone formation. The results of this large prospective trial show that such an agent reduces both vertebral and clinical fracture and reduces that fracture risk quite rapidly within the first 6 months of therapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacLaughlin KL, Faubion SS, Long ME, Pruthi S, Casey PM. Should the annual pelvic examination go the way of annual cervical cytology? Womens Health (Lond). 2014;10(4):373–384.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King AB, Tosterson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):465–475.

- Kaunitz AM. Hormonal contraception in women of older reproductive age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1262–1270.

- Kaunitz AM. Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(2 suppl):S32–S37.

- Gambacciani M, Cappagli B, Lazzarini V, Ciaponi M, Fruzzetti F, Genazzani AR. Longitudinal evaluation of perimenopausal bone loss: effects of different low dose oral contraceptive preparations on bone mineral density. Maturitas. 2006;54(2):176–180.

- Bailey R, Dodd K, Goldman J, et al. Estimation of total usual calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):817–822.

- Bolland MJ, Grey A, Reid IR. Calcium supplements and cardiovascular risk: 5 years on. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4(5):199–210.

- Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(9):691–696.

- Bristow SM, Gamble GD, Stewart A, Horne AM, Reid IR. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure and blood coagulation: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial in post-menopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(11):1868–1874.

- He H, Liu Y, Tian Q, Papasian CJ, Hu T, Deng HW. Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(2):473–482.

- Coin A, Perissinotto E, Enzi G, et al. Predictors of low bone mineral density in the elderly: the role of dietary intake, nutritional status and sarcopenia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):802–809.

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1343–1352.

- Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997;127(5 suppl):990S–991S.

- Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyere O, Reginster JY, Biver E. Sarcopenia: Burden and challenges for Public Health. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):45.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):748–759.

- Kulkarni B, Kuper H, Taylor A, et al. Development and validation of anthropometric prediction equations for estimation of lean body mass and appendicular lean soft tissue in Indian men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115(8):1156–1162.

Prioritize bone health, as osteoporotic fracture is a major source of morbidity and mortality among women. In this article: fracture risk with OC use in perimenopause, data that inform calcium’s role in cardiovascular disease, sarcopenia management, and an emerging treatment.

Most women’s health care providers are aware of recent changes and controversies regarding cervical cancer screening, mammography frequency, and whether a pelvic bimanual exam should be part of our annual well woman evaluation.1 However, I believe one of the most important things we as clinicians can do is be frontline in promoting bone health. Osteoporotic fracture is a major source of morbidity and mortality.2,3 Thus, promoting the maintenance of bone health is a priority in my own practice. It is also one of my many academic interests.

What follows is an update on bone health. In past years, this update has been entitled, “Update on osteoporosis,” but what we are trying to accomplish is fracture reduction. Thus, priorities for bone health consist of recognition of risk, lifestyle and dietary counseling, as well as the use of pharmacologic agents when appropriate. Certain research stands out as informative for your practice:

- a recent study on the risk of fracture with oral contraceptive (OC) use in perimenopause

- 3 just-published studies that inform our understanding of calcium’s role in cardiovascular health

- a review on sarcopenia management

- new data on romosozumab.

Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause

Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Hubbard RA, et al. Oral contraceptive use and fracture risk around the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2016;23(2):166-174.

The use of OCs in women of older reproductive age has increased ever since the cutoff age of 35 years was eliminated.4 Lower doses have continued to be utilized in these "older" women with excellent control of irregular bleeding due to ovulatory dysfunction (and reduction in psychosocial symptoms as well).5

The effect of OC use on risk of fracture remains unclear, and use during later reproductive life may be increasing. To determine the association between OC use during later reproductive life and risk of fracture across the menopausal transition, Scholes and colleagues conducted a population-based case-controlled study in a Pacific Northwest HMO, Group Health Cooperative.

Details of the study

Scholes and colleagues enrolled 1,204 case women aged 45 to 59 years with incident fractures, and 2,275 control women. Potential cases with fracture codes in automated data were adjudicated by electronic health record review. Potential control women without fracture codes were selected concurrently, sampling based on age. Participants received a structured study interview. Using logistic regression, associations between OC use and fracture risk were calculated as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Participation was 69% for cases and 64% for controls. The study sample was 82% white; mean age was 54 years. The most common fracture site for cases was the wrist/forearm (32%). Adjusted fracture risk did not differ between cases and controls for OC use:

- in the 10 years before menopause (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.74-1.11)

- after age 38 years (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.78-1.14)

- over the duration, or

- for other OC exposures.

Related article:

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

Association between fractures and OC use near menopause

The current study does not show an association between fractures near the menopausal transition and OC use in the decade before menopause or after age 38 years. For women considering OC use at these times, fracture risk does not seem to be either reduced or increased.

These results, looking at fracture, seem to be further supported by trials conducted by Gambacciani and colleagues,6 in which researchers randomly assigned irregularly cycling perimenopausal women (aged 40-49 years) to 20 μg ethinyl estradiol OCs or calcium/placebo. Results showed that this low-dose OC use significantly increased bone density at the femoral neck, spine, and other sites relative to control women after 24 months.

In the current Scholes study, the use of OCs in the decade before menopause or after age 38 did not reduce fracture risk in the years around the time of menopause. It is reassuring that their use was not associated with any increased fracture risk.

These findings provide additional clarity and guidance to women and their clinicians at a time of increasing public health concern about fractures. For women who may choose to use OCs during late premenopause (around age 38-48 years), fracture risk around the menopausal transition will not differ from women not choosing this option.

Calcium and calcium supplements: The data continue to grow

Anderson JJ, Kruszka B, Delaney JA, et al. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [published online ahead of print October 11, 2016]. J Am Heart Assoc. pii: e003815.

Billington EO, Bristow SM, Gamble GD, et al. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure: randomised, crossover trial in postmenopausal women [published online ahead of print August 20, 2016]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3744-y.

Crandall CJ, Aragaki AK, LeBoff MS, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and height loss: findings from the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D clinical trial [published online ahead of print August 1, 2016]. Menopause. doi:10.1097 /GME.0000000000000704.

In 2001, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Panel on osteoporosis concluded that calcium intake is crucial to maintain bone mass and should be maintained at 1,000-1,500 mg/day in older adults. The panel acknowledged that the majority of older adults did not meet the recommended intake from dietary sources alone, and therefore would require calcium supplementation. Calcium supplements are one of the most commonly used dietary supplements, and population-based surveys have shown that they are used by the majority of older men and women in the United States.7

More recently results from large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of calcium supplements have been reported, leading to concerns about calcium efficacy for fracture risk and safety. Bolland and colleagues8 reported that calcium supplements increased the rate of cardiovascular events in healthy older women and suggested that their role in osteoporosis management be reconsidered. More recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against calcium supplements for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.9

The association between calcium intake and CVD events

Anderson and colleagues acknowledged that recent randomized data suggest that calcium supplements may be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. Using a longitudinal cohort study, they assessed the association between calcium intake, from both foods and supplements, and atherosclerosis, as measured by coronary artery calcification (CAC).

Details of the study by Anderson and colleagues

The authors studied 5,448 adults free of clinically diagnosed CVD (52% female; age range, 45-84 years) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Baseline total calcium intake was assessed from diet (using a food frequency questionnaire) and calcium supplements (by a medication inventory) and categorized into quintiles based on overall population distribution. Baseline CAC was measured by computed tomography (CT) scan, and CAC measurements were repeated in 2,742 participants approximately 10 years later. Women had higher calcium intakes than men.

After adjustment for potential confounders, among 1,567 participants without baseline CAC, the relative risk (RR) of developing incident CAC over 10 years, by quintile 1 to 5 of calcium intake is included in the TABLE. After accounting for total calcium intake, calcium supplement use was associated with increased risk for incident CAC (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39). No relation was found between baseline calcium intake and 10-year changes in CAC among those participants with baseline CAC less than zero.

They concluded that high total calcium intake was associated with a decreased risk of incident atherosclerosis over long-term follow-up, particularly if achieved without supplement use. However, calcium supplement use may increase the risk for incident CAC.

Related article:

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

Calcium supplements and blood pressure

Billington and colleagues acknowledged that calcium supplements appear to increase cardiovascular risk but that the mechanism is unknown. They had previously reported that blood pressure declines over the course of the day in older women.10

Details of the study by Billington and colleagues

In this new study the investigators examined the acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure in a randomized controlled crossover trial in 40 healthy postmenopausal women (mean age, 71 years; body mass index [BMI], 27.2 kg/m2). Women attended on 2 occasions, with visits separated by 7 or more days. At each visit, they received either 1 g of calcium as citrate or placebo. Blood pressure and serum calcium concentrations were measured immediately before and 2, 4, and 6 hours after each intervention.

Ionized and total calcium concentrations increased after calcium (P<.0001 vs placebo). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements decreased after both calcium and placebo but significantly less so after calcium (P=.02). The reduction in SBP from baseline was smaller after calcium compared with placebo by 6 mm Hg at 4 hours (P=.036) and by 9 mm Hg at 6 hours (P=.002). The reduction in diastolic blood pressure was similar after calcium and placebo.

These findings indicate that the use of calcium supplements in postmenopausal women attenuates the postbreakfast reduction in SBP by 6 to 9 mm Hg. Whether these changes in blood pressure influence cardiovascular risk requires further study.

Association between calcium, vitamin D, and height loss

Crandall and colleagues looked at the association between calcium and vitamin D supplementation and height loss in 36,282 participants of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D trial.

Details of the study by Crandall and colleagues

The authors performed a post hoc analysis of data from a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate with 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily (CaD) or placebo in postmenopausal women at 40 US clinical centers. Height was measured annually (mean follow-up, 5.9 years) with a stadiometer.

Average height loss was 1.28 mm/yr among participants assigned to CaD, versus 1.26 mm/yr for women assigned to placebo (P=.35). A strong association (P<.001) was observed between age group and height loss. The study authors concluded that, compared with placebo, calcium and vitamin D supplementation used in this trial did not prevent height loss in healthy postmenopausal women.

Adequate calcium is necessary for bone health. While calcium supplementation may not be adequate to prevent fractures, it is also not involved in the inevitable loss of overall height seen in postmenopausal women. Calcium supplementation has been implicated in an increase in CVD. These data seem to indicate that, while calcium supplementation results in higher systolic blood pressure during the day, as well as higher coronary artery calcium scores, greater dietary calcium actually may decrease the incidence of atherosclerosis.

Sarcopenia: Still important, clinical approaches to easily detect it

Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyére O, et al. Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):170.

In last year's update, I reviewed the article by He and colleagues11 on the relationship between sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Sarcopenia, which is the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is important to address in patients. Body composition and muscle strength are directly correlated with bone density, and this is not surprising since bone and muscle share some common hormonal, genetic, nutritional, and lifestyle determinants.12,13 Sarcopenia can be diagnosed via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan looking at lean muscle mass.

The term sarcopenia was first coined by Rosenberg and colleagues in 198914 as a progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass with advancing age. Since then, the definition has expanded to incorporate the notion of impaired muscle strength or physical performance. Sarcopenia is associated with morbidity and mortality from linked physical disability, falls, fractures, poor quality of life, depression, and hospitalization.15

Current research is focusing on nutritional exercise/activity-based and other novel interventions for improving the quality and quantity of skeletal muscle in older people. Some studies demonstrated that resistance training combined with nutritional supplements can improve muscle function.16

Details of the study

Beaudart and colleagues propose some user-friendly and inexpensive methods that can be utilized to assess sarcopenia in real life settings. They acknowledge that in research settings or even specialist clinical settings, DXA or computed tomography (CT) scans are the best assessment of muscle mass.

Anthropometric measurements. In a primary care setting, anthropometric measurement, especially calf circumference and mid-upper arm muscle circumference, correlate with overall muscle mass and reflect both health and nutritional status and predict performance, health, and survival in older people.

However, with advancing age, changes in the distribution of fat and loss of skin elasticity are such that circumference incurs a loss of accuracy and precision in older people. Some studies suggest that an adjustment of anthropometric measurements for age, sex, or BMI results in a better correlation with DXA-measured lean mass.17 Anthropometric measurements are simple clinical prediction tools that can be easily applied for sarcopenia since they offer the most portable, commonly applicable, inexpensive, and noninvasive technique for assessing size, proportions, and composition of the human body. However, their validity is limited when applied to individuals because cutoff points to identify low muscle mass still need to be defined. Still, serial measurements in a patient over time may be valuable.

Related article:

2014 Update on osteoporosis

Handgrip strength, as measured with a dynamometer, appears to be the most widely used method for the measurement of muscle strength. In general, isometric handgrip strength shows a good correlation with leg strength and also with lower extremity power, and calf cross-sectional muscle area. The measurement is easy to perform, inexpensive and does not require a specialist-trained staff.

Standardized conditions for the test include seating the patient in a standard chair with her forearms resting flat on the chair arms. Clinicians should demonstrate the use of the dynamometer and show that gripping very tightly registers the best score. Six measurements should be taken, 3 with each arm. Ideally, patients should be encouraged to squeeze as hard and tightly as possible during 3 to 5 seconds for each of the 6 trials; usually the highest reading of the 6 measurements is reported as the final result. The Jamar dynamometer, or similar hydraulic dynamometer, is the gold standard for this measurement.

Gait speed measurement. The most widely used tool in clinical practice for the assessment of physical performance is the gait speed measurement. The test is highly acceptable for participants and health professionals in clinical settings. No special equipment is required; it needs only a flat floor devoid of obstacles. In the 4-meter gait speed test, men and women with a gait speed of less than 0.8 meters/sec are described as having a poor physical performance. The average extra time added to the consultation by measuring the 4-meter gait speed was only 95 seconds (SD, 20 seconds).

Loss of muscle mass correlates with loss of bone mass as our patients age. In addition, such sarcopenia increases the risk of falls, a significant component of the rising rate of fragility fractures. Anthropometric measures, grip strength, and gait speed are easy, low-cost measures that can identify patients at increased risk.

Romosozumab: An interesting new agent to look forward to

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1532-1543.

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds sclerostin, increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption. Cosman and colleagues enrolled 7,180 postmenopausal women with a T score of -2.5 to -3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck. Participants were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous injections of romosozumab 210 mg or placebo monthly for 12 months. Thereafter, women in each group received subcutaneous denosumab 60 mg for 12 months--administered every 6 months. The coprimary end points were the cumulative incidences of new vertebral fractures at 12 and 24 months. Secondary end points included clinical and nonvertebral fractures.

Details of the study

At 12 months, new vertebral fractures had occurred in 16 of 3,321 women (0.5%) in the romosozumab group, as compared with 59 of 3,322 (1.8%) in the placebo group (representing a 73% lower risk of fracture with romosozumab; P<.001). Clinical fractures had occurred in 58 of 3,589 women (1.6%) in the romosozumab group, as compared with 90 of 3,591 (2.5%) in the placebo group (a 36% lower fracture risk with romosozumab; P = .008). Nonvertebral fractures had occurred in 56 of 3,589 women (1.6%) in the romosozumab group and in 75 of 3,591 (2.1%) in the placebo group (P = .10).

At 24 months, the rates of vertebral fractures were significantly lower in the romosozumab group than in the placebo group after each group made the transition to denosumab (0.6% [21 of 3,325 women] in the romosozumab group vs 2.5% [84 of 3,327 women] in the placebo group, a 75% lower risk with romosozumab; P<.001). Adverse events, including cardiovascular events, osteoarthritis, and cancer, appeared to be balanced between the groups. One atypical femoral fracture and 2 cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw were observed in the romosozumab group.

Lower risk of fracture

Thus, in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, romosozumab was associated with a lower risk of vertebral fracture than placebo at 12 months and, after the transition to denosumab, at 24 months. The lower risk of clinical fracture that was seen with romosozumab was evident at 1 year.

Of note, the effect of romosozumab on the risk of vertebral fracture was rapid, with only 2 additional vertebral fractures (of a total of 16 such fractures in the romosozumab group) occurring in the second 6 months of the first year of therapy. Because vertebral and clinical fractures are associated with increased morbidity and considerable health care costs, a treatment that would reduce this risk rapidly could offer appropriate patients an important benefit.

Romosozumab is a new agent. Though not yet available, it is extremely interesting because it not only decreases bone resorption but also increases bone formation. The results of this large prospective trial show that such an agent reduces both vertebral and clinical fracture and reduces that fracture risk quite rapidly within the first 6 months of therapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Prioritize bone health, as osteoporotic fracture is a major source of morbidity and mortality among women. In this article: fracture risk with OC use in perimenopause, data that inform calcium’s role in cardiovascular disease, sarcopenia management, and an emerging treatment.

Most women’s health care providers are aware of recent changes and controversies regarding cervical cancer screening, mammography frequency, and whether a pelvic bimanual exam should be part of our annual well woman evaluation.1 However, I believe one of the most important things we as clinicians can do is be frontline in promoting bone health. Osteoporotic fracture is a major source of morbidity and mortality.2,3 Thus, promoting the maintenance of bone health is a priority in my own practice. It is also one of my many academic interests.

What follows is an update on bone health. In past years, this update has been entitled, “Update on osteoporosis,” but what we are trying to accomplish is fracture reduction. Thus, priorities for bone health consist of recognition of risk, lifestyle and dietary counseling, as well as the use of pharmacologic agents when appropriate. Certain research stands out as informative for your practice:

- a recent study on the risk of fracture with oral contraceptive (OC) use in perimenopause

- 3 just-published studies that inform our understanding of calcium’s role in cardiovascular health

- a review on sarcopenia management

- new data on romosozumab.

Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause

Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Hubbard RA, et al. Oral contraceptive use and fracture risk around the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2016;23(2):166-174.

The use of OCs in women of older reproductive age has increased ever since the cutoff age of 35 years was eliminated.4 Lower doses have continued to be utilized in these "older" women with excellent control of irregular bleeding due to ovulatory dysfunction (and reduction in psychosocial symptoms as well).5

The effect of OC use on risk of fracture remains unclear, and use during later reproductive life may be increasing. To determine the association between OC use during later reproductive life and risk of fracture across the menopausal transition, Scholes and colleagues conducted a population-based case-controlled study in a Pacific Northwest HMO, Group Health Cooperative.

Details of the study

Scholes and colleagues enrolled 1,204 case women aged 45 to 59 years with incident fractures, and 2,275 control women. Potential cases with fracture codes in automated data were adjudicated by electronic health record review. Potential control women without fracture codes were selected concurrently, sampling based on age. Participants received a structured study interview. Using logistic regression, associations between OC use and fracture risk were calculated as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Participation was 69% for cases and 64% for controls. The study sample was 82% white; mean age was 54 years. The most common fracture site for cases was the wrist/forearm (32%). Adjusted fracture risk did not differ between cases and controls for OC use:

- in the 10 years before menopause (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.74-1.11)

- after age 38 years (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.78-1.14)

- over the duration, or

- for other OC exposures.

Related article:

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

Association between fractures and OC use near menopause

The current study does not show an association between fractures near the menopausal transition and OC use in the decade before menopause or after age 38 years. For women considering OC use at these times, fracture risk does not seem to be either reduced or increased.

These results, looking at fracture, seem to be further supported by trials conducted by Gambacciani and colleagues,6 in which researchers randomly assigned irregularly cycling perimenopausal women (aged 40-49 years) to 20 μg ethinyl estradiol OCs or calcium/placebo. Results showed that this low-dose OC use significantly increased bone density at the femoral neck, spine, and other sites relative to control women after 24 months.

In the current Scholes study, the use of OCs in the decade before menopause or after age 38 did not reduce fracture risk in the years around the time of menopause. It is reassuring that their use was not associated with any increased fracture risk.

These findings provide additional clarity and guidance to women and their clinicians at a time of increasing public health concern about fractures. For women who may choose to use OCs during late premenopause (around age 38-48 years), fracture risk around the menopausal transition will not differ from women not choosing this option.

Calcium and calcium supplements: The data continue to grow

Anderson JJ, Kruszka B, Delaney JA, et al. Calcium intake from diet and supplements and the risk of coronary artery calcification and its progression among older adults: 10-year follow-up of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [published online ahead of print October 11, 2016]. J Am Heart Assoc. pii: e003815.

Billington EO, Bristow SM, Gamble GD, et al. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure: randomised, crossover trial in postmenopausal women [published online ahead of print August 20, 2016]. Osteoporos Int. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3744-y.

Crandall CJ, Aragaki AK, LeBoff MS, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and height loss: findings from the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D clinical trial [published online ahead of print August 1, 2016]. Menopause. doi:10.1097 /GME.0000000000000704.

In 2001, a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Panel on osteoporosis concluded that calcium intake is crucial to maintain bone mass and should be maintained at 1,000-1,500 mg/day in older adults. The panel acknowledged that the majority of older adults did not meet the recommended intake from dietary sources alone, and therefore would require calcium supplementation. Calcium supplements are one of the most commonly used dietary supplements, and population-based surveys have shown that they are used by the majority of older men and women in the United States.7

More recently results from large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of calcium supplements have been reported, leading to concerns about calcium efficacy for fracture risk and safety. Bolland and colleagues8 reported that calcium supplements increased the rate of cardiovascular events in healthy older women and suggested that their role in osteoporosis management be reconsidered. More recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended against calcium supplements for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.9

The association between calcium intake and CVD events

Anderson and colleagues acknowledged that recent randomized data suggest that calcium supplements may be associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. Using a longitudinal cohort study, they assessed the association between calcium intake, from both foods and supplements, and atherosclerosis, as measured by coronary artery calcification (CAC).

Details of the study by Anderson and colleagues

The authors studied 5,448 adults free of clinically diagnosed CVD (52% female; age range, 45-84 years) from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Baseline total calcium intake was assessed from diet (using a food frequency questionnaire) and calcium supplements (by a medication inventory) and categorized into quintiles based on overall population distribution. Baseline CAC was measured by computed tomography (CT) scan, and CAC measurements were repeated in 2,742 participants approximately 10 years later. Women had higher calcium intakes than men.

After adjustment for potential confounders, among 1,567 participants without baseline CAC, the relative risk (RR) of developing incident CAC over 10 years, by quintile 1 to 5 of calcium intake is included in the TABLE. After accounting for total calcium intake, calcium supplement use was associated with increased risk for incident CAC (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.07-1.39). No relation was found between baseline calcium intake and 10-year changes in CAC among those participants with baseline CAC less than zero.

They concluded that high total calcium intake was associated with a decreased risk of incident atherosclerosis over long-term follow-up, particularly if achieved without supplement use. However, calcium supplement use may increase the risk for incident CAC.

Related article:

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

Calcium supplements and blood pressure

Billington and colleagues acknowledged that calcium supplements appear to increase cardiovascular risk but that the mechanism is unknown. They had previously reported that blood pressure declines over the course of the day in older women.10

Details of the study by Billington and colleagues

In this new study the investigators examined the acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure in a randomized controlled crossover trial in 40 healthy postmenopausal women (mean age, 71 years; body mass index [BMI], 27.2 kg/m2). Women attended on 2 occasions, with visits separated by 7 or more days. At each visit, they received either 1 g of calcium as citrate or placebo. Blood pressure and serum calcium concentrations were measured immediately before and 2, 4, and 6 hours after each intervention.

Ionized and total calcium concentrations increased after calcium (P<.0001 vs placebo). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements decreased after both calcium and placebo but significantly less so after calcium (P=.02). The reduction in SBP from baseline was smaller after calcium compared with placebo by 6 mm Hg at 4 hours (P=.036) and by 9 mm Hg at 6 hours (P=.002). The reduction in diastolic blood pressure was similar after calcium and placebo.

These findings indicate that the use of calcium supplements in postmenopausal women attenuates the postbreakfast reduction in SBP by 6 to 9 mm Hg. Whether these changes in blood pressure influence cardiovascular risk requires further study.

Association between calcium, vitamin D, and height loss

Crandall and colleagues looked at the association between calcium and vitamin D supplementation and height loss in 36,282 participants of the Women's Health Initiative Calcium and Vitamin D trial.

Details of the study by Crandall and colleagues

The authors performed a post hoc analysis of data from a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 1,000 mg of elemental calcium as calcium carbonate with 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily (CaD) or placebo in postmenopausal women at 40 US clinical centers. Height was measured annually (mean follow-up, 5.9 years) with a stadiometer.

Average height loss was 1.28 mm/yr among participants assigned to CaD, versus 1.26 mm/yr for women assigned to placebo (P=.35). A strong association (P<.001) was observed between age group and height loss. The study authors concluded that, compared with placebo, calcium and vitamin D supplementation used in this trial did not prevent height loss in healthy postmenopausal women.

Adequate calcium is necessary for bone health. While calcium supplementation may not be adequate to prevent fractures, it is also not involved in the inevitable loss of overall height seen in postmenopausal women. Calcium supplementation has been implicated in an increase in CVD. These data seem to indicate that, while calcium supplementation results in higher systolic blood pressure during the day, as well as higher coronary artery calcium scores, greater dietary calcium actually may decrease the incidence of atherosclerosis.

Sarcopenia: Still important, clinical approaches to easily detect it

Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyére O, et al. Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):170.

In last year's update, I reviewed the article by He and colleagues11 on the relationship between sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Sarcopenia, which is the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is important to address in patients. Body composition and muscle strength are directly correlated with bone density, and this is not surprising since bone and muscle share some common hormonal, genetic, nutritional, and lifestyle determinants.12,13 Sarcopenia can be diagnosed via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan looking at lean muscle mass.

The term sarcopenia was first coined by Rosenberg and colleagues in 198914 as a progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass with advancing age. Since then, the definition has expanded to incorporate the notion of impaired muscle strength or physical performance. Sarcopenia is associated with morbidity and mortality from linked physical disability, falls, fractures, poor quality of life, depression, and hospitalization.15

Current research is focusing on nutritional exercise/activity-based and other novel interventions for improving the quality and quantity of skeletal muscle in older people. Some studies demonstrated that resistance training combined with nutritional supplements can improve muscle function.16

Details of the study

Beaudart and colleagues propose some user-friendly and inexpensive methods that can be utilized to assess sarcopenia in real life settings. They acknowledge that in research settings or even specialist clinical settings, DXA or computed tomography (CT) scans are the best assessment of muscle mass.

Anthropometric measurements. In a primary care setting, anthropometric measurement, especially calf circumference and mid-upper arm muscle circumference, correlate with overall muscle mass and reflect both health and nutritional status and predict performance, health, and survival in older people.

However, with advancing age, changes in the distribution of fat and loss of skin elasticity are such that circumference incurs a loss of accuracy and precision in older people. Some studies suggest that an adjustment of anthropometric measurements for age, sex, or BMI results in a better correlation with DXA-measured lean mass.17 Anthropometric measurements are simple clinical prediction tools that can be easily applied for sarcopenia since they offer the most portable, commonly applicable, inexpensive, and noninvasive technique for assessing size, proportions, and composition of the human body. However, their validity is limited when applied to individuals because cutoff points to identify low muscle mass still need to be defined. Still, serial measurements in a patient over time may be valuable.

Related article:

2014 Update on osteoporosis

Handgrip strength, as measured with a dynamometer, appears to be the most widely used method for the measurement of muscle strength. In general, isometric handgrip strength shows a good correlation with leg strength and also with lower extremity power, and calf cross-sectional muscle area. The measurement is easy to perform, inexpensive and does not require a specialist-trained staff.

Standardized conditions for the test include seating the patient in a standard chair with her forearms resting flat on the chair arms. Clinicians should demonstrate the use of the dynamometer and show that gripping very tightly registers the best score. Six measurements should be taken, 3 with each arm. Ideally, patients should be encouraged to squeeze as hard and tightly as possible during 3 to 5 seconds for each of the 6 trials; usually the highest reading of the 6 measurements is reported as the final result. The Jamar dynamometer, or similar hydraulic dynamometer, is the gold standard for this measurement.

Gait speed measurement. The most widely used tool in clinical practice for the assessment of physical performance is the gait speed measurement. The test is highly acceptable for participants and health professionals in clinical settings. No special equipment is required; it needs only a flat floor devoid of obstacles. In the 4-meter gait speed test, men and women with a gait speed of less than 0.8 meters/sec are described as having a poor physical performance. The average extra time added to the consultation by measuring the 4-meter gait speed was only 95 seconds (SD, 20 seconds).

Loss of muscle mass correlates with loss of bone mass as our patients age. In addition, such sarcopenia increases the risk of falls, a significant component of the rising rate of fragility fractures. Anthropometric measures, grip strength, and gait speed are easy, low-cost measures that can identify patients at increased risk.

Romosozumab: An interesting new agent to look forward to

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, et al. Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(16):1532-1543.

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds sclerostin, increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption. Cosman and colleagues enrolled 7,180 postmenopausal women with a T score of -2.5 to -3.5 at the total hip or femoral neck. Participants were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous injections of romosozumab 210 mg or placebo monthly for 12 months. Thereafter, women in each group received subcutaneous denosumab 60 mg for 12 months--administered every 6 months. The coprimary end points were the cumulative incidences of new vertebral fractures at 12 and 24 months. Secondary end points included clinical and nonvertebral fractures.

Details of the study

At 12 months, new vertebral fractures had occurred in 16 of 3,321 women (0.5%) in the romosozumab group, as compared with 59 of 3,322 (1.8%) in the placebo group (representing a 73% lower risk of fracture with romosozumab; P<.001). Clinical fractures had occurred in 58 of 3,589 women (1.6%) in the romosozumab group, as compared with 90 of 3,591 (2.5%) in the placebo group (a 36% lower fracture risk with romosozumab; P = .008). Nonvertebral fractures had occurred in 56 of 3,589 women (1.6%) in the romosozumab group and in 75 of 3,591 (2.1%) in the placebo group (P = .10).

At 24 months, the rates of vertebral fractures were significantly lower in the romosozumab group than in the placebo group after each group made the transition to denosumab (0.6% [21 of 3,325 women] in the romosozumab group vs 2.5% [84 of 3,327 women] in the placebo group, a 75% lower risk with romosozumab; P<.001). Adverse events, including cardiovascular events, osteoarthritis, and cancer, appeared to be balanced between the groups. One atypical femoral fracture and 2 cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw were observed in the romosozumab group.

Lower risk of fracture

Thus, in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, romosozumab was associated with a lower risk of vertebral fracture than placebo at 12 months and, after the transition to denosumab, at 24 months. The lower risk of clinical fracture that was seen with romosozumab was evident at 1 year.

Of note, the effect of romosozumab on the risk of vertebral fracture was rapid, with only 2 additional vertebral fractures (of a total of 16 such fractures in the romosozumab group) occurring in the second 6 months of the first year of therapy. Because vertebral and clinical fractures are associated with increased morbidity and considerable health care costs, a treatment that would reduce this risk rapidly could offer appropriate patients an important benefit.

Romosozumab is a new agent. Though not yet available, it is extremely interesting because it not only decreases bone resorption but also increases bone formation. The results of this large prospective trial show that such an agent reduces both vertebral and clinical fracture and reduces that fracture risk quite rapidly within the first 6 months of therapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacLaughlin KL, Faubion SS, Long ME, Pruthi S, Casey PM. Should the annual pelvic examination go the way of annual cervical cytology? Womens Health (Lond). 2014;10(4):373–384.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King AB, Tosterson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):465–475.

- Kaunitz AM. Hormonal contraception in women of older reproductive age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1262–1270.

- Kaunitz AM. Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(2 suppl):S32–S37.

- Gambacciani M, Cappagli B, Lazzarini V, Ciaponi M, Fruzzetti F, Genazzani AR. Longitudinal evaluation of perimenopausal bone loss: effects of different low dose oral contraceptive preparations on bone mineral density. Maturitas. 2006;54(2):176–180.

- Bailey R, Dodd K, Goldman J, et al. Estimation of total usual calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):817–822.

- Bolland MJ, Grey A, Reid IR. Calcium supplements and cardiovascular risk: 5 years on. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4(5):199–210.

- Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(9):691–696.

- Bristow SM, Gamble GD, Stewart A, Horne AM, Reid IR. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure and blood coagulation: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial in post-menopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(11):1868–1874.

- He H, Liu Y, Tian Q, Papasian CJ, Hu T, Deng HW. Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(2):473–482.

- Coin A, Perissinotto E, Enzi G, et al. Predictors of low bone mineral density in the elderly: the role of dietary intake, nutritional status and sarcopenia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):802–809.

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1343–1352.

- Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997;127(5 suppl):990S–991S.

- Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyere O, Reginster JY, Biver E. Sarcopenia: Burden and challenges for Public Health. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):45.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):748–759.

- Kulkarni B, Kuper H, Taylor A, et al. Development and validation of anthropometric prediction equations for estimation of lean body mass and appendicular lean soft tissue in Indian men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115(8):1156–1162.

- MacLaughlin KL, Faubion SS, Long ME, Pruthi S, Casey PM. Should the annual pelvic examination go the way of annual cervical cytology? Womens Health (Lond). 2014;10(4):373–384.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King AB, Tosterson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22(3):465–475.

- Kaunitz AM. Hormonal contraception in women of older reproductive age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1262–1270.

- Kaunitz AM. Oral contraceptive use in perimenopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(2 suppl):S32–S37.

- Gambacciani M, Cappagli B, Lazzarini V, Ciaponi M, Fruzzetti F, Genazzani AR. Longitudinal evaluation of perimenopausal bone loss: effects of different low dose oral contraceptive preparations on bone mineral density. Maturitas. 2006;54(2):176–180.

- Bailey R, Dodd K, Goldman J, et al. Estimation of total usual calcium and vitamin D intakes in the United States. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):817–822.

- Bolland MJ, Grey A, Reid IR. Calcium supplements and cardiovascular risk: 5 years on. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4(5):199–210.

- Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(9):691–696.

- Bristow SM, Gamble GD, Stewart A, Horne AM, Reid IR. Acute effects of calcium supplements on blood pressure and blood coagulation: secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial in post-menopausal women. Br J Nutr. 2015;114(11):1868–1874.

- He H, Liu Y, Tian Q, Papasian CJ, Hu T, Deng HW. Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(2):473–482.

- Coin A, Perissinotto E, Enzi G, et al. Predictors of low bone mineral density in the elderly: the role of dietary intake, nutritional status and sarcopenia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):802–809.

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1343–1352.

- Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997;127(5 suppl):990S–991S.

- Beaudart C, Rizzoli R, Bruyere O, Reginster JY, Biver E. Sarcopenia: Burden and challenges for Public Health. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):45.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):748–759.

- Kulkarni B, Kuper H, Taylor A, et al. Development and validation of anthropometric prediction equations for estimation of lean body mass and appendicular lean soft tissue in Indian men and women. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115(8):1156–1162.

FDA approves vaginal insert to treat dyspareunia in menopause

Prasterone (Intrarosa), a vaginal insert containing dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to treat dyspareunia in menopause caused by vulvar and vaginal atrophy, has won Food and Drug Administration approval.

It’s the first FDA-approved product containing the active ingredient prasterone, known also as DHEA. It will be marketed by Endoceutics Inc., a Quebec-based pharmaceutical company focused on women’s health.

The approval is based on the results of two 12-week placebo-controlled trials of 406 healthy, postmenopausal women, ranging in age from 40 to 80 years, who identified dyspareunia as their most bothersome symptom of VVA. During the trials, prasterone reduced the severity of pain experienced during sexual intercourse, when compared with placebo. Safety of the treatment was established in four 12-week placebo-controlled trials and one 52-week open-label trial. The most common adverse events were vaginal discharge and abnormal Pap smear, according to the FDA.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Prasterone (Intrarosa), a vaginal insert containing dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to treat dyspareunia in menopause caused by vulvar and vaginal atrophy, has won Food and Drug Administration approval.

It’s the first FDA-approved product containing the active ingredient prasterone, known also as DHEA. It will be marketed by Endoceutics Inc., a Quebec-based pharmaceutical company focused on women’s health.

The approval is based on the results of two 12-week placebo-controlled trials of 406 healthy, postmenopausal women, ranging in age from 40 to 80 years, who identified dyspareunia as their most bothersome symptom of VVA. During the trials, prasterone reduced the severity of pain experienced during sexual intercourse, when compared with placebo. Safety of the treatment was established in four 12-week placebo-controlled trials and one 52-week open-label trial. The most common adverse events were vaginal discharge and abnormal Pap smear, according to the FDA.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Prasterone (Intrarosa), a vaginal insert containing dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to treat dyspareunia in menopause caused by vulvar and vaginal atrophy, has won Food and Drug Administration approval.

It’s the first FDA-approved product containing the active ingredient prasterone, known also as DHEA. It will be marketed by Endoceutics Inc., a Quebec-based pharmaceutical company focused on women’s health.

The approval is based on the results of two 12-week placebo-controlled trials of 406 healthy, postmenopausal women, ranging in age from 40 to 80 years, who identified dyspareunia as their most bothersome symptom of VVA. During the trials, prasterone reduced the severity of pain experienced during sexual intercourse, when compared with placebo. Safety of the treatment was established in four 12-week placebo-controlled trials and one 52-week open-label trial. The most common adverse events were vaginal discharge and abnormal Pap smear, according to the FDA.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

It’s not easy to identify clinical depression in menopause

The notion that women in midlife are moody is so pervasive that entire Pinterest boards and Facebook pages are dedicated to menopause jokes. For physicians, however, it’s not always so easy to sort out when a patient who says she’s down, or short tempered, might really have major depressive disorder or another serious psychiatric diagnosis.

“The key point is that depressive symptoms are not the same as clinical depression,” said Hadine Joffe, MD, in an interview that recapped her recent presentation at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS). “The causal factors and contributions to depressive symptoms and major depression are different.”

Practically speaking, this means two things. The first message is that treating common menopausal symptoms can have a positive impact on mood. However, it’s also true that clinicians must be educated and vigilant about more serious mood symptoms, and not expect major depression to lift when a patient starts hormone therapy, according to Dr. Joffe, a psychiatrist and director of the women’s hormone and aging research program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Using a novel experimental model, Dr. Joffe and her coinvestigators recently completed work that examined the relationship among daytime and nighttime hot flashes, sleep disturbance, and mood changes. In a small study of 29 healthy premenopausal women, they tracked mood, hormone levels, and sleep fragmentation both before and after suppressing ovarian function with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. The study found independent and significant effects on mood for nighttime (but not daytime) hot flashes, as well as subjective sleep disturbance (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101[10]:3847-55).

“We were struck by the fact that the nighttime hot flashes, separate from the sleep problems, contributed to mood symptoms,” Dr. Joffe said.

This study, though small, validates and extends the notion that multiple symptoms of the menopausal transition contribute to the mild mood symptoms that are common during this phase of a woman’s life, said Dr. Joffe. To date, most of the studies have been large epidemiologic studies, which while important, tend to assess people at one cross-sectional time point annually, and can’t always capture a nuanced and precise view of symptoms and how they relate to hormone levels, she said.

“Perimenopausal hormone changes are dynamic,” said Dr. Joffe, and have wide interindividual variation during the menopausal transition. Overall, though, she said, “clinical studies show that mood is better as ovarian activity is more normalized in perimenopausal women. Conversely, the more abnormal the hormonal profile, the worse the mood.”

Major depression is another story, said Dr. Joffe. “Menopause-specific factors have not, for the most part, been linked,” she said, noting that the best predictors for clinical depression in midlife that have been identified to date are a previous history of clinical depression or anxiety, as well as other traditional psychiatric risk factors such as low socioeconomic status and a low level of social support.

“People often present with all these symptoms all at once; they have mood disturbances, they have hot flashes, they have sleep disturbances. For the people experiencing these symptoms, it matters a lot to be able to have an explanation that’s credible, and defendable, and evidence based,” Dr. Joffe said. “And it also has implications for treatment, of course.”

This real world complexity inevitably intrudes during a clinical encounter, and it’s not an easy task, or a quick one, to tease apart the extent to which the menopausal transition is contributing to depressive symptoms when women have so many other potential stressors.

While acknowledging that it’s very difficult to unpack this in a brief clinic visit, Dr. Shifren also emphasized that it’s critically important. For patients with mild depressive symptoms, hormone therapy or other treatment to address vasomotor symptoms, along with evidence-based treatment of sleep problems, can be of real help.

“That’s very different from women who come in with real depression,” Dr. Shifren said in an interview. “It’s very important not to say, ‘Oh, that’s just a little bit of perimenopause.’ ”

“There is not enough education of general providers about the nuances of mood changes and mental health of women in midlife,” Dr. Montgomery said in an interview. “These are nicely dealt with in publications of the North American Menopause Society,” he said, also noting that the ob.gyn. residency curriculum at Drexel University includes specific modules to address the menopausal transition and menopause. “If you are going to be caring for women in transition, you probably should do a little deeper dive,” he said.

“My advice for clinicians is don’t do this alone,” Dr. Shifren said. If clinicians feel they lack expertise in diagnosing and managing mood disorders, they should establish collaborative relationships with colleagues in mental health. “We can still help with hormone management, sleep management, and keeping in touch with the patient,” she said.

One trick of the trade is to use your nursing staff to follow up with patients, Dr. Shifren said. She will ask a nurse to make a follow-up phone call 2-6 weeks after a patient visit to assess how the woman is faring with symptoms and any treatments that have been initiated or modified. The interval and intensity of follow-up can be modified based on feedback from this call, she said.

The bottom line for Dr. Montgomery is twofold: “Being menopausal does not make you depressed,” he said. “True clinical depression is a rare event, but one that should not be missed.”