User login

FDA lifts partial clinical hold for some selinexor trials

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of selinexor (KPT-330) in patients with hematologic malignancies.

The partial hold, which was announced on March 10, was placed on all trials of the drug, including those in patients with solid tumor malignancies.

The hold meant that no new patients could be enrolled in selinexor trials.

Patients who were already enrolled and had stable disease or better could remain on selinexor therapy.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on trials of patients with hematologic malignancies, so new patients can be enrolled in these trials and begin receiving selinexor.

The FDA had placed the hold due to a lack of information in the investigator’s brochure, including an incomplete list of serious adverse events associated with selinexor.

Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor, noted that the hold was not the result of patient deaths or any new information regarding the safety profile of selinexor.

In response to the hold, Karyopharm amended the investigator’s brochure, updated informed consent documents, and submitted the documents to the FDA.

“The Karyopharm team worked diligently to update and submit the required documents to the FDA, which allowed the hematology division to expeditiously remove the partial clinical hold,” said Michael G. Kauffman, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Karyopharm.

“We anticipate that the solid tumor divisions will follow suit shortly. Patient enrollment is again underway in our hematologic oncology studies. Our previously disclosed enrollment rates and timelines for both ongoing and planned trials are not expected to be materially impacted.”

About selinexor

Selinexor is a first-in-class, oral, selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound. The drug functions by inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1).

This leads to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus, which subsequently reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function. This is thought to prompt apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

To date, more than 1900 patients have been treated with selinexor.

The drug is currently being evaluated in clinical trials across multiple cancer indications, including in acute myeloid leukemia (SOPRA), in multiple myeloma in combination with low-dose dexamethasone (STORM) and backbone therapies (STOMP), as well as in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (SADAL).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of selinexor (KPT-330) in patients with hematologic malignancies.

The partial hold, which was announced on March 10, was placed on all trials of the drug, including those in patients with solid tumor malignancies.

The hold meant that no new patients could be enrolled in selinexor trials.

Patients who were already enrolled and had stable disease or better could remain on selinexor therapy.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on trials of patients with hematologic malignancies, so new patients can be enrolled in these trials and begin receiving selinexor.

The FDA had placed the hold due to a lack of information in the investigator’s brochure, including an incomplete list of serious adverse events associated with selinexor.

Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor, noted that the hold was not the result of patient deaths or any new information regarding the safety profile of selinexor.

In response to the hold, Karyopharm amended the investigator’s brochure, updated informed consent documents, and submitted the documents to the FDA.

“The Karyopharm team worked diligently to update and submit the required documents to the FDA, which allowed the hematology division to expeditiously remove the partial clinical hold,” said Michael G. Kauffman, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Karyopharm.

“We anticipate that the solid tumor divisions will follow suit shortly. Patient enrollment is again underway in our hematologic oncology studies. Our previously disclosed enrollment rates and timelines for both ongoing and planned trials are not expected to be materially impacted.”

About selinexor

Selinexor is a first-in-class, oral, selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound. The drug functions by inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1).

This leads to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus, which subsequently reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function. This is thought to prompt apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

To date, more than 1900 patients have been treated with selinexor.

The drug is currently being evaluated in clinical trials across multiple cancer indications, including in acute myeloid leukemia (SOPRA), in multiple myeloma in combination with low-dose dexamethasone (STORM) and backbone therapies (STOMP), as well as in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (SADAL).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the partial clinical hold on trials of selinexor (KPT-330) in patients with hematologic malignancies.

The partial hold, which was announced on March 10, was placed on all trials of the drug, including those in patients with solid tumor malignancies.

The hold meant that no new patients could be enrolled in selinexor trials.

Patients who were already enrolled and had stable disease or better could remain on selinexor therapy.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on trials of patients with hematologic malignancies, so new patients can be enrolled in these trials and begin receiving selinexor.

The FDA had placed the hold due to a lack of information in the investigator’s brochure, including an incomplete list of serious adverse events associated with selinexor.

Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor, noted that the hold was not the result of patient deaths or any new information regarding the safety profile of selinexor.

In response to the hold, Karyopharm amended the investigator’s brochure, updated informed consent documents, and submitted the documents to the FDA.

“The Karyopharm team worked diligently to update and submit the required documents to the FDA, which allowed the hematology division to expeditiously remove the partial clinical hold,” said Michael G. Kauffman, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Karyopharm.

“We anticipate that the solid tumor divisions will follow suit shortly. Patient enrollment is again underway in our hematologic oncology studies. Our previously disclosed enrollment rates and timelines for both ongoing and planned trials are not expected to be materially impacted.”

About selinexor

Selinexor is a first-in-class, oral, selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound. The drug functions by inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1).

This leads to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus, which subsequently reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function. This is thought to prompt apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

To date, more than 1900 patients have been treated with selinexor.

The drug is currently being evaluated in clinical trials across multiple cancer indications, including in acute myeloid leukemia (SOPRA), in multiple myeloma in combination with low-dose dexamethasone (STORM) and backbone therapies (STOMP), as well as in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (SADAL).

NCCN launches radiation therapy resource

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) recently launched the NCCN Radiation Therapy Compendium™, which provides a single access point for NCCN recommendations pertaining to radiation therapy.

The compendium provides guidance on all radiation therapy modalities recommended within NCCN guidelines, including intensity modulated radiation therapy, intra-operative radiation therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery/stereotactic body radiotherapy/stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, image-guided radiotherapy, low dose-rate brachytherapy/high dose-rate brachytherapy, radioisotope, and particle therapy.

“As a single source for all radiation therapy recommendations within the NCCN guidelines, the compendium benefits patients with cancer by assisting providers and payers in making evidence-based treatment and coverage decisions,” said Robert W. Carlson, MD, chief executive officer of NCCN.

The NCCN Radiation Therapy Compendium™ includes recommendations for the following 24 cancer types:

Acute myeloid leukemia

Anal cancer

B-cell lymphomas

Bladder cancer

Breast cancer

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphoblastic lymphoma

Colon cancer

Hepatobiliary cancers

Kidney cancer

Malignant pleural mesothelioma

Melanoma

Multiple myeloma

Neuroendocrine tumors

Non-small cell lung cancer

Occult primary cancer

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Penile cancer

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas

Prostate cancer

Rectal cancer

Small cell lung cancer

Soft tissue sarcoma

T-cell lymphomas

Testicular cancer

NCCN said additional cancer types will be published on a rolling basis over the coming months. ![]()

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) recently launched the NCCN Radiation Therapy Compendium™, which provides a single access point for NCCN recommendations pertaining to radiation therapy.

The compendium provides guidance on all radiation therapy modalities recommended within NCCN guidelines, including intensity modulated radiation therapy, intra-operative radiation therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery/stereotactic body radiotherapy/stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, image-guided radiotherapy, low dose-rate brachytherapy/high dose-rate brachytherapy, radioisotope, and particle therapy.

“As a single source for all radiation therapy recommendations within the NCCN guidelines, the compendium benefits patients with cancer by assisting providers and payers in making evidence-based treatment and coverage decisions,” said Robert W. Carlson, MD, chief executive officer of NCCN.

The NCCN Radiation Therapy Compendium™ includes recommendations for the following 24 cancer types:

Acute myeloid leukemia

Anal cancer

B-cell lymphomas

Bladder cancer

Breast cancer

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphoblastic lymphoma

Colon cancer

Hepatobiliary cancers

Kidney cancer

Malignant pleural mesothelioma

Melanoma

Multiple myeloma

Neuroendocrine tumors

Non-small cell lung cancer

Occult primary cancer

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Penile cancer

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas

Prostate cancer

Rectal cancer

Small cell lung cancer

Soft tissue sarcoma

T-cell lymphomas

Testicular cancer

NCCN said additional cancer types will be published on a rolling basis over the coming months. ![]()

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) recently launched the NCCN Radiation Therapy Compendium™, which provides a single access point for NCCN recommendations pertaining to radiation therapy.

The compendium provides guidance on all radiation therapy modalities recommended within NCCN guidelines, including intensity modulated radiation therapy, intra-operative radiation therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery/stereotactic body radiotherapy/stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, image-guided radiotherapy, low dose-rate brachytherapy/high dose-rate brachytherapy, radioisotope, and particle therapy.

“As a single source for all radiation therapy recommendations within the NCCN guidelines, the compendium benefits patients with cancer by assisting providers and payers in making evidence-based treatment and coverage decisions,” said Robert W. Carlson, MD, chief executive officer of NCCN.

The NCCN Radiation Therapy Compendium™ includes recommendations for the following 24 cancer types:

Acute myeloid leukemia

Anal cancer

B-cell lymphomas

Bladder cancer

Breast cancer

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphoblastic lymphoma

Colon cancer

Hepatobiliary cancers

Kidney cancer

Malignant pleural mesothelioma

Melanoma

Multiple myeloma

Neuroendocrine tumors

Non-small cell lung cancer

Occult primary cancer

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Penile cancer

Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas

Prostate cancer

Rectal cancer

Small cell lung cancer

Soft tissue sarcoma

T-cell lymphomas

Testicular cancer

NCCN said additional cancer types will be published on a rolling basis over the coming months. ![]()

ASCO reports progress, challenges in cancer care

The US cancer care delivery system is undergoing changes to better meet the needs of cancer patients, but persistent hurdles threaten to slow progress, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

ASCO’s “The State of Cancer Care in America, 2017” report describes areas of progress, including new approaches for cancer diagnosis and treatment, improved data sharing to drive innovation, and an increased focus on value-based healthcare.

However, the report also suggests that access and affordability challenges, along with increased practice burdens, continue to pose barriers to high-value, high-quality cancer care.

The report was published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

Challenges

The report notes that the US population is growing rapidly, changing demographically, and living longer. And all of these factors contribute to a record number of cancer cases/survivors.

It has been estimated that the number of cancer survivors in the US will grow from 15.5 million to 20.3 million by 2026.

Unfortunately, the report says, cancer care is unaffordable for many patients, even those with health insurance.

And significant health disparities persist that are independent of insurance status. Socioeconomic status, geography, and race/ethnicity all impact patient health outcomes.

The report also suggests that oncology practices are facing increased administrative burdens that divert time and resources from their patients.

Progress

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the report paints an optimistic vision about the future of cancer care and highlights activity in the past year aimed at improving care.

For instance, the Food and Drug Administration approved 5 new anticancer therapies, expanded the use of 13, and approved several diagnostic tests in 2016.

In addition, overall cancer incidence and mortality rates were lower in 2016 than in previous decades.

“Since 1991, we’ve been able to save 2.1 million lives because of significant advances in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment—something unimaginable even a decade ago,” said ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD.

“But there’s still more work to be done to ensure that every patient with cancer, no matter who they are or where they live, has access to high-quality, high-value cancer care.”

The report includes a list of recommendations that, ASCO believes, could help bring the US closer to achieving that goal. ![]()

The US cancer care delivery system is undergoing changes to better meet the needs of cancer patients, but persistent hurdles threaten to slow progress, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

ASCO’s “The State of Cancer Care in America, 2017” report describes areas of progress, including new approaches for cancer diagnosis and treatment, improved data sharing to drive innovation, and an increased focus on value-based healthcare.

However, the report also suggests that access and affordability challenges, along with increased practice burdens, continue to pose barriers to high-value, high-quality cancer care.

The report was published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

Challenges

The report notes that the US population is growing rapidly, changing demographically, and living longer. And all of these factors contribute to a record number of cancer cases/survivors.

It has been estimated that the number of cancer survivors in the US will grow from 15.5 million to 20.3 million by 2026.

Unfortunately, the report says, cancer care is unaffordable for many patients, even those with health insurance.

And significant health disparities persist that are independent of insurance status. Socioeconomic status, geography, and race/ethnicity all impact patient health outcomes.

The report also suggests that oncology practices are facing increased administrative burdens that divert time and resources from their patients.

Progress

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the report paints an optimistic vision about the future of cancer care and highlights activity in the past year aimed at improving care.

For instance, the Food and Drug Administration approved 5 new anticancer therapies, expanded the use of 13, and approved several diagnostic tests in 2016.

In addition, overall cancer incidence and mortality rates were lower in 2016 than in previous decades.

“Since 1991, we’ve been able to save 2.1 million lives because of significant advances in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment—something unimaginable even a decade ago,” said ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD.

“But there’s still more work to be done to ensure that every patient with cancer, no matter who they are or where they live, has access to high-quality, high-value cancer care.”

The report includes a list of recommendations that, ASCO believes, could help bring the US closer to achieving that goal. ![]()

The US cancer care delivery system is undergoing changes to better meet the needs of cancer patients, but persistent hurdles threaten to slow progress, according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

ASCO’s “The State of Cancer Care in America, 2017” report describes areas of progress, including new approaches for cancer diagnosis and treatment, improved data sharing to drive innovation, and an increased focus on value-based healthcare.

However, the report also suggests that access and affordability challenges, along with increased practice burdens, continue to pose barriers to high-value, high-quality cancer care.

The report was published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

Challenges

The report notes that the US population is growing rapidly, changing demographically, and living longer. And all of these factors contribute to a record number of cancer cases/survivors.

It has been estimated that the number of cancer survivors in the US will grow from 15.5 million to 20.3 million by 2026.

Unfortunately, the report says, cancer care is unaffordable for many patients, even those with health insurance.

And significant health disparities persist that are independent of insurance status. Socioeconomic status, geography, and race/ethnicity all impact patient health outcomes.

The report also suggests that oncology practices are facing increased administrative burdens that divert time and resources from their patients.

Progress

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the report paints an optimistic vision about the future of cancer care and highlights activity in the past year aimed at improving care.

For instance, the Food and Drug Administration approved 5 new anticancer therapies, expanded the use of 13, and approved several diagnostic tests in 2016.

In addition, overall cancer incidence and mortality rates were lower in 2016 than in previous decades.

“Since 1991, we’ve been able to save 2.1 million lives because of significant advances in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment—something unimaginable even a decade ago,” said ASCO President Daniel F. Hayes, MD.

“But there’s still more work to be done to ensure that every patient with cancer, no matter who they are or where they live, has access to high-quality, high-value cancer care.”

The report includes a list of recommendations that, ASCO believes, could help bring the US closer to achieving that goal. ![]()

New resource designed to help prevent CINV

The Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association (HOPA) has announced the release of a toolkit intended to help prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in cancer patients.

The Time to Talk CINV™ toolkit was designed to facilitate dialogue between patients and their healthcare teams to ensure no patient is needlessly suffering from CINV.

The tools in the kit, which are targeted to both patients and healthcare providers, were created with guidance from patients, caregivers, pharmacists, and nurses.

The entire toolkit is available for free download at TimeToTalkCINV.com.

The toolkit is part of the Time to Talk CINV™ campaign, which is a collaboration between HOPA, Eisai Inc., and Helsinn Therapeutics (US), Inc. (funded by Eisai and Helsinn Therapeutics).

The campaign began in response to results from a survey of cancer patients.

“Our research revealed a vast majority of patients on chemotherapy who experience nausea and vomiting expect to have this side effect, and 95% of these patients said, at some point, chemo-induced nausea and vomiting had an impact on their daily lives,” said Sarah Peters, PharmD, president of HOPA.

“In response to these findings, as well as the finding that healthcare team members are looking for better communication tools, the Time to Talk CINV toolkit was created to facilitate efficient and effective conversations about nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy to ensure that each patient is receiving the right information and effective management approaches.”

The Time to Talk CINV toolkit includes the following resources:

- A list of myths and truths about CINV intended to eliminate common misperceptions

- A checklist of questions patients can ask healthcare providers to better understand CINV

- A chemotherapy side effect tracker, which enables patients to track their experience and report back to their healthcare team

- A communication checklist for the healthcare team outlining best practices for communicating with patients to prevent CINV.

Each tool can be printed or filled out digitally.

Additional information about CINV, including videos and infographics, can be found on the Time to Talk CINV website. ![]()

The Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association (HOPA) has announced the release of a toolkit intended to help prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in cancer patients.

The Time to Talk CINV™ toolkit was designed to facilitate dialogue between patients and their healthcare teams to ensure no patient is needlessly suffering from CINV.

The tools in the kit, which are targeted to both patients and healthcare providers, were created with guidance from patients, caregivers, pharmacists, and nurses.

The entire toolkit is available for free download at TimeToTalkCINV.com.

The toolkit is part of the Time to Talk CINV™ campaign, which is a collaboration between HOPA, Eisai Inc., and Helsinn Therapeutics (US), Inc. (funded by Eisai and Helsinn Therapeutics).

The campaign began in response to results from a survey of cancer patients.

“Our research revealed a vast majority of patients on chemotherapy who experience nausea and vomiting expect to have this side effect, and 95% of these patients said, at some point, chemo-induced nausea and vomiting had an impact on their daily lives,” said Sarah Peters, PharmD, president of HOPA.

“In response to these findings, as well as the finding that healthcare team members are looking for better communication tools, the Time to Talk CINV toolkit was created to facilitate efficient and effective conversations about nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy to ensure that each patient is receiving the right information and effective management approaches.”

The Time to Talk CINV toolkit includes the following resources:

- A list of myths and truths about CINV intended to eliminate common misperceptions

- A checklist of questions patients can ask healthcare providers to better understand CINV

- A chemotherapy side effect tracker, which enables patients to track their experience and report back to their healthcare team

- A communication checklist for the healthcare team outlining best practices for communicating with patients to prevent CINV.

Each tool can be printed or filled out digitally.

Additional information about CINV, including videos and infographics, can be found on the Time to Talk CINV website. ![]()

The Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association (HOPA) has announced the release of a toolkit intended to help prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in cancer patients.

The Time to Talk CINV™ toolkit was designed to facilitate dialogue between patients and their healthcare teams to ensure no patient is needlessly suffering from CINV.

The tools in the kit, which are targeted to both patients and healthcare providers, were created with guidance from patients, caregivers, pharmacists, and nurses.

The entire toolkit is available for free download at TimeToTalkCINV.com.

The toolkit is part of the Time to Talk CINV™ campaign, which is a collaboration between HOPA, Eisai Inc., and Helsinn Therapeutics (US), Inc. (funded by Eisai and Helsinn Therapeutics).

The campaign began in response to results from a survey of cancer patients.

“Our research revealed a vast majority of patients on chemotherapy who experience nausea and vomiting expect to have this side effect, and 95% of these patients said, at some point, chemo-induced nausea and vomiting had an impact on their daily lives,” said Sarah Peters, PharmD, president of HOPA.

“In response to these findings, as well as the finding that healthcare team members are looking for better communication tools, the Time to Talk CINV toolkit was created to facilitate efficient and effective conversations about nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy to ensure that each patient is receiving the right information and effective management approaches.”

The Time to Talk CINV toolkit includes the following resources:

- A list of myths and truths about CINV intended to eliminate common misperceptions

- A checklist of questions patients can ask healthcare providers to better understand CINV

- A chemotherapy side effect tracker, which enables patients to track their experience and report back to their healthcare team

- A communication checklist for the healthcare team outlining best practices for communicating with patients to prevent CINV.

Each tool can be printed or filled out digitally.

Additional information about CINV, including videos and infographics, can be found on the Time to Talk CINV website. ![]()

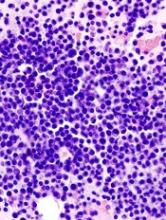

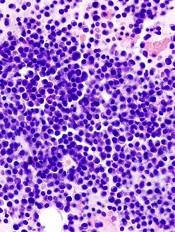

New approach for monitoring minimum residual disease in multiple myeloma

Next-generation sequencing might be useful to monitor for minimum residual disease in multiple myeloma, based on the results of a pilot study of 27 patients.

Of study participants whose multiple myeloma at least partially remitted on therapy, 41% showed evidence of persistent circulating myeloma cells or cell-free myeloma DNA based on next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J rearrangement, compared with 91% of nonresponders or progressors (P less than .001), reported Anna Oberle of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, and her associates. The findings were published in Haematologica.

“Taken together, our pilot study gives valuable biological insights into the circulating cellular and cell-free compartments explorable by ‘liquid biopsy’ in multiple myeloma,” the investigators wrote. Levels of V(D)J-positive circulating myeloma cells and cell-free DNA might decline faster in response to effective therapy than the “relatively inert M-protein,” and might therefore be a better way to immediately estimate treatment efficacy or predict minimum residual disease negativity, they added (Haematologica. 2017 Feb 9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.161414).

Novel multiple myeloma therapies are inducing deeper, longer responses, which highlights the need for minimum residual disease monitoring, the researchers said. Next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J immunoglobulin rearrangement has shown promise but requires painful bone marrow sampling. A minimally invasive alternative is to monitor for circulating myeloma cells (cmc) or cell-free myeloma (cfm). To investigate the feasibility of this technique, the researchers used next-generation sequencing to define the myeloma V(D)J rearrangement in bone marrow and to track sequential peripheral blood samples from multiple myeloma patients before and during treatment. Next-generation sequencing was performed with an Illumina MiSeq sequencer with 500 or 600 cycle single-indexed, paired-end runs.

After treatment initiation, 47% of follow-up peripheral blood samples were positive for cmc-V(D)J, cfm-V(D)J, or both, the researchers said. They found a clear link between poor remission status assessed by M-protein based IMWG criteria and positive cmc-V(D)J sampling, with a regression coefficient of 1.60 (95% CI, 0.68 to 2.50; P = .002). Poor remission status was also associated with evidence of cfm-V(D)J (regression coefficient 1.49; 95% CI, 0.70 to 2.27; P = .001).

“About half of partial responders showed complete clearance of circulating myeloma cells-/cell-free myeloma DNA -V(D)J despite persistent M-protein, suggesting that these markers are less inert than the M-protein, rely more on cell turnover, and therefore decline more rapidly after initiation of effective treatment,” the researchers emphasized. Also, in 30% of cases, patients were positive for only one of the two V(D)J measures, suggesting that cfm-V(D)J might reflect overall tumor burden, not just circulating tumor cells, they added. “Prospective studies need to define the predictive potential of high-sensitivity determination of circulating myeloma cells and DNA in the monitoring of multiple myeloma,” they concluded.

Eppendorfer Krebs- und Leukämiehilfe e.V. and the Deutsche Krebshilfe funded the study. The researchers disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Next-generation sequencing might be useful to monitor for minimum residual disease in multiple myeloma, based on the results of a pilot study of 27 patients.

Of study participants whose multiple myeloma at least partially remitted on therapy, 41% showed evidence of persistent circulating myeloma cells or cell-free myeloma DNA based on next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J rearrangement, compared with 91% of nonresponders or progressors (P less than .001), reported Anna Oberle of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, and her associates. The findings were published in Haematologica.

“Taken together, our pilot study gives valuable biological insights into the circulating cellular and cell-free compartments explorable by ‘liquid biopsy’ in multiple myeloma,” the investigators wrote. Levels of V(D)J-positive circulating myeloma cells and cell-free DNA might decline faster in response to effective therapy than the “relatively inert M-protein,” and might therefore be a better way to immediately estimate treatment efficacy or predict minimum residual disease negativity, they added (Haematologica. 2017 Feb 9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.161414).

Novel multiple myeloma therapies are inducing deeper, longer responses, which highlights the need for minimum residual disease monitoring, the researchers said. Next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J immunoglobulin rearrangement has shown promise but requires painful bone marrow sampling. A minimally invasive alternative is to monitor for circulating myeloma cells (cmc) or cell-free myeloma (cfm). To investigate the feasibility of this technique, the researchers used next-generation sequencing to define the myeloma V(D)J rearrangement in bone marrow and to track sequential peripheral blood samples from multiple myeloma patients before and during treatment. Next-generation sequencing was performed with an Illumina MiSeq sequencer with 500 or 600 cycle single-indexed, paired-end runs.

After treatment initiation, 47% of follow-up peripheral blood samples were positive for cmc-V(D)J, cfm-V(D)J, or both, the researchers said. They found a clear link between poor remission status assessed by M-protein based IMWG criteria and positive cmc-V(D)J sampling, with a regression coefficient of 1.60 (95% CI, 0.68 to 2.50; P = .002). Poor remission status was also associated with evidence of cfm-V(D)J (regression coefficient 1.49; 95% CI, 0.70 to 2.27; P = .001).

“About half of partial responders showed complete clearance of circulating myeloma cells-/cell-free myeloma DNA -V(D)J despite persistent M-protein, suggesting that these markers are less inert than the M-protein, rely more on cell turnover, and therefore decline more rapidly after initiation of effective treatment,” the researchers emphasized. Also, in 30% of cases, patients were positive for only one of the two V(D)J measures, suggesting that cfm-V(D)J might reflect overall tumor burden, not just circulating tumor cells, they added. “Prospective studies need to define the predictive potential of high-sensitivity determination of circulating myeloma cells and DNA in the monitoring of multiple myeloma,” they concluded.

Eppendorfer Krebs- und Leukämiehilfe e.V. and the Deutsche Krebshilfe funded the study. The researchers disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Next-generation sequencing might be useful to monitor for minimum residual disease in multiple myeloma, based on the results of a pilot study of 27 patients.

Of study participants whose multiple myeloma at least partially remitted on therapy, 41% showed evidence of persistent circulating myeloma cells or cell-free myeloma DNA based on next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J rearrangement, compared with 91% of nonresponders or progressors (P less than .001), reported Anna Oberle of University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, and her associates. The findings were published in Haematologica.

“Taken together, our pilot study gives valuable biological insights into the circulating cellular and cell-free compartments explorable by ‘liquid biopsy’ in multiple myeloma,” the investigators wrote. Levels of V(D)J-positive circulating myeloma cells and cell-free DNA might decline faster in response to effective therapy than the “relatively inert M-protein,” and might therefore be a better way to immediately estimate treatment efficacy or predict minimum residual disease negativity, they added (Haematologica. 2017 Feb 9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.161414).

Novel multiple myeloma therapies are inducing deeper, longer responses, which highlights the need for minimum residual disease monitoring, the researchers said. Next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J immunoglobulin rearrangement has shown promise but requires painful bone marrow sampling. A minimally invasive alternative is to monitor for circulating myeloma cells (cmc) or cell-free myeloma (cfm). To investigate the feasibility of this technique, the researchers used next-generation sequencing to define the myeloma V(D)J rearrangement in bone marrow and to track sequential peripheral blood samples from multiple myeloma patients before and during treatment. Next-generation sequencing was performed with an Illumina MiSeq sequencer with 500 or 600 cycle single-indexed, paired-end runs.

After treatment initiation, 47% of follow-up peripheral blood samples were positive for cmc-V(D)J, cfm-V(D)J, or both, the researchers said. They found a clear link between poor remission status assessed by M-protein based IMWG criteria and positive cmc-V(D)J sampling, with a regression coefficient of 1.60 (95% CI, 0.68 to 2.50; P = .002). Poor remission status was also associated with evidence of cfm-V(D)J (regression coefficient 1.49; 95% CI, 0.70 to 2.27; P = .001).

“About half of partial responders showed complete clearance of circulating myeloma cells-/cell-free myeloma DNA -V(D)J despite persistent M-protein, suggesting that these markers are less inert than the M-protein, rely more on cell turnover, and therefore decline more rapidly after initiation of effective treatment,” the researchers emphasized. Also, in 30% of cases, patients were positive for only one of the two V(D)J measures, suggesting that cfm-V(D)J might reflect overall tumor burden, not just circulating tumor cells, they added. “Prospective studies need to define the predictive potential of high-sensitivity determination of circulating myeloma cells and DNA in the monitoring of multiple myeloma,” they concluded.

Eppendorfer Krebs- und Leukämiehilfe e.V. and the Deutsche Krebshilfe funded the study. The researchers disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Next-generation sequencing might be useful to monitor for minimum residual disease in multiple myeloma.

Major finding: Of patients who at least partially remitted on therapy, 41% showed evidence of persistent circulating myeloma cells or cell-free myeloma DNA based on next-generation sequencing of the clonotypic V(D)J rearrangement, compared with 91% of nonresponders or progressors (P less than .001).

Data source: A pilot study of 27 patients with multiple myeloma.

Disclosures: Eppendorfer Krebs- und Leukämiehilfe e.V. and the Deutsche Krebshilfe funded the study. The researchers disclosed no conflicts of interest.

ADCs could treat myeloma, other malignancies

A class of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have shown promise for treating hematologic and solid tumor malignancies, according to research published in Cell Chemical Biology.

The ADCs, known as selenomab-drug conjugates, demonstrated in vitro activity against breast cancer and multiple myeloma (MM).

The ADCs also inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in mouse models of both malignancies.

“We’ve been working on this technology for some time,” said study author Christoph Rader, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in Jupiter, Florida.

“It’s based on the rarely used natural amino acid selenocysteine, which we insert into our antibodies. We refer to these engineered antibodies as selenomabs.”

He then explained that selenomab-drug conjugates are ADCs that “utilize the unique reactivity of selenocysteine for drug attachment.”

For this study, Dr Rader and his colleagues generated selective selenomab-drug conjugates and tested them in vitro and in vivo.

The team found that CD138-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates were effective against MM cell lines (U266 and H929), and HER2-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates were effective against breast cancer cell lines.

Both types of ADCs demonstrated efficacy in mouse models as well.

One of the CD138-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates, known as CN29, was tested in a mouse model of MM.

One group of mice received CN29 at 3 mg/kg every 4 days for a total of 4 cycles, another group received unconjugated selenomab, and a third received vehicle control.

CN29 significantly inhibited tumor growth (P=0.000085) and extended survival time (P=0.0083) in the mice.

Based on these results, Dr Rader said selenomab-drug conjugates “promise broad utility for cancer therapy.” ![]()

A class of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have shown promise for treating hematologic and solid tumor malignancies, according to research published in Cell Chemical Biology.

The ADCs, known as selenomab-drug conjugates, demonstrated in vitro activity against breast cancer and multiple myeloma (MM).

The ADCs also inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in mouse models of both malignancies.

“We’ve been working on this technology for some time,” said study author Christoph Rader, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in Jupiter, Florida.

“It’s based on the rarely used natural amino acid selenocysteine, which we insert into our antibodies. We refer to these engineered antibodies as selenomabs.”

He then explained that selenomab-drug conjugates are ADCs that “utilize the unique reactivity of selenocysteine for drug attachment.”

For this study, Dr Rader and his colleagues generated selective selenomab-drug conjugates and tested them in vitro and in vivo.

The team found that CD138-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates were effective against MM cell lines (U266 and H929), and HER2-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates were effective against breast cancer cell lines.

Both types of ADCs demonstrated efficacy in mouse models as well.

One of the CD138-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates, known as CN29, was tested in a mouse model of MM.

One group of mice received CN29 at 3 mg/kg every 4 days for a total of 4 cycles, another group received unconjugated selenomab, and a third received vehicle control.

CN29 significantly inhibited tumor growth (P=0.000085) and extended survival time (P=0.0083) in the mice.

Based on these results, Dr Rader said selenomab-drug conjugates “promise broad utility for cancer therapy.” ![]()

A class of antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) have shown promise for treating hematologic and solid tumor malignancies, according to research published in Cell Chemical Biology.

The ADCs, known as selenomab-drug conjugates, demonstrated in vitro activity against breast cancer and multiple myeloma (MM).

The ADCs also inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival in mouse models of both malignancies.

“We’ve been working on this technology for some time,” said study author Christoph Rader, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) in Jupiter, Florida.

“It’s based on the rarely used natural amino acid selenocysteine, which we insert into our antibodies. We refer to these engineered antibodies as selenomabs.”

He then explained that selenomab-drug conjugates are ADCs that “utilize the unique reactivity of selenocysteine for drug attachment.”

For this study, Dr Rader and his colleagues generated selective selenomab-drug conjugates and tested them in vitro and in vivo.

The team found that CD138-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates were effective against MM cell lines (U266 and H929), and HER2-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates were effective against breast cancer cell lines.

Both types of ADCs demonstrated efficacy in mouse models as well.

One of the CD138-targeting selenomab-drug conjugates, known as CN29, was tested in a mouse model of MM.

One group of mice received CN29 at 3 mg/kg every 4 days for a total of 4 cycles, another group received unconjugated selenomab, and a third received vehicle control.

CN29 significantly inhibited tumor growth (P=0.000085) and extended survival time (P=0.0083) in the mice.

Based on these results, Dr Rader said selenomab-drug conjugates “promise broad utility for cancer therapy.” ![]()

Auto-HCT patients run high risks for myeloid neoplasms

ORLANDO – For post–autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (auto-HCT) patients, the 10-year risk of developing a myeloid neoplasm was as high as 6%, based on a recent review of two large cancer databases.

Older age at transplant, receiving total body irradiation, and receiving multiple lines of chemotherapy before transplant all upped the risk of later cancers, according to a study presented by Shahrukh Hashmi, MD, and his collaborators at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“The guidelines for autologous stem cell transplantation for surveillance for AML [acute myeloid leukemia] and MDS [myelodysplastic syndrome] need to be clearly formulated. We are doing 30,000 autologous transplants a year globally and these patients are at risk for the most feared cancer, which is leukemia and MDS, for which outcomes are very poor,” said Dr. Hashmi of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The researchers examined data from auto-HCT patients with diagnoses of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma to determine the relative risks of developing AML and MDS. The study also explored which patient characteristics and aspects of the conditioning regimen might affect risk for later myeloid neoplasms.

In the dataset of 9,108 patients that Dr. Hashmi and his colleagues obtained from CIBMTR, 3,540 patients had NHL.

“As age progresses, the risk of acquiring myeloid neoplasms increases significantly,” he said, noting that the relative risk (RR) rose to 4.52 for patients aged 55 years and older at the time of transplant (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.63-7.77; P less than .0001).

Patients with NHL who received more than two lines of chemotherapy had approximately double the rate of myeloid cancers (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.34-2.78; P = .0004).

The type of conditioning regimen made a difference for NHL patients as well. With total-body irradiation set as the reference at RR = 1, carmustine-etoposide-cytarabine-melphalan (BEAM) or similar therapies were relatively protective, with an RR of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.40-0.87; P = .0083). Also protective were cyclophosphamide-carmustine-etoposide (CBV) and similar therapies (RR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33-0.99; P = .0463).

Age at transplant was a factor among the 4,653 patients with multiple myeloma, with an RR of 2.47 for those transplanted at age 55 years or older (95% CI, 1.55-3.93; P = .0001). Multiple lines of chemotherapy also increased risk, with patients who received more than two lines having an RR of 1.77 for neoplasm (95% CI, 0.04-2.06; P = .0302). Women had less than half the risk of recurrence as men (RR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.28-0.69; P = .0003).

Among the 915 study patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, patients aged 45 years and older at the time of transplant carried an RR of 5.59 for new myeloid neoplasms (95% CI, 2.98-11.70; P less than .0001).

Total-body irradiation was received by 14% of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and by 5% of patients with multiple myeloma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Total-body irradiation was associated with a fourfold increase in neoplasm risk (RR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.40-11.55; P = .0096).

Dr. Hashmi and his colleagues then examined the incidence rates for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database , finding that, even at baseline, the rates of myeloid neoplasms were higher for patients with NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, or MM patients than for the general population of cancer survivors. “Post NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma, the risks are significantly higher to begin with. … We saw a high risk of AML and MDS compared to the SEER controls – risks as high as 100 times greater for auto-transplant patients,” said Dr. Hashmi. “A risk of one hundred times more for MDS was astounding, surprising, unexpected,” he said. The risk of AML, he said, was elevated about 10-50 times in the CIBMTR data.

The cumulative incidence of MDS or AML for NHL was 6% at 10 years post transplant, 4% for Hodgkin lymphoma, and 3% for multiple myeloma.

A limitation of the study, said Dr. Hashmi, was that the investigators did not assess for post-transplant maintenance chemotherapy.

“We have to prospectively assess our transplant patients in a fashion to detect changes early. Or maybe they were present at the time of transplant and we never did sophisticated methods [like] next-generation sequencing” to detect them, he said.

Dr. Hashmi reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – For post–autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (auto-HCT) patients, the 10-year risk of developing a myeloid neoplasm was as high as 6%, based on a recent review of two large cancer databases.

Older age at transplant, receiving total body irradiation, and receiving multiple lines of chemotherapy before transplant all upped the risk of later cancers, according to a study presented by Shahrukh Hashmi, MD, and his collaborators at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“The guidelines for autologous stem cell transplantation for surveillance for AML [acute myeloid leukemia] and MDS [myelodysplastic syndrome] need to be clearly formulated. We are doing 30,000 autologous transplants a year globally and these patients are at risk for the most feared cancer, which is leukemia and MDS, for which outcomes are very poor,” said Dr. Hashmi of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The researchers examined data from auto-HCT patients with diagnoses of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma to determine the relative risks of developing AML and MDS. The study also explored which patient characteristics and aspects of the conditioning regimen might affect risk for later myeloid neoplasms.

In the dataset of 9,108 patients that Dr. Hashmi and his colleagues obtained from CIBMTR, 3,540 patients had NHL.

“As age progresses, the risk of acquiring myeloid neoplasms increases significantly,” he said, noting that the relative risk (RR) rose to 4.52 for patients aged 55 years and older at the time of transplant (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.63-7.77; P less than .0001).

Patients with NHL who received more than two lines of chemotherapy had approximately double the rate of myeloid cancers (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.34-2.78; P = .0004).

The type of conditioning regimen made a difference for NHL patients as well. With total-body irradiation set as the reference at RR = 1, carmustine-etoposide-cytarabine-melphalan (BEAM) or similar therapies were relatively protective, with an RR of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.40-0.87; P = .0083). Also protective were cyclophosphamide-carmustine-etoposide (CBV) and similar therapies (RR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33-0.99; P = .0463).

Age at transplant was a factor among the 4,653 patients with multiple myeloma, with an RR of 2.47 for those transplanted at age 55 years or older (95% CI, 1.55-3.93; P = .0001). Multiple lines of chemotherapy also increased risk, with patients who received more than two lines having an RR of 1.77 for neoplasm (95% CI, 0.04-2.06; P = .0302). Women had less than half the risk of recurrence as men (RR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.28-0.69; P = .0003).

Among the 915 study patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, patients aged 45 years and older at the time of transplant carried an RR of 5.59 for new myeloid neoplasms (95% CI, 2.98-11.70; P less than .0001).

Total-body irradiation was received by 14% of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and by 5% of patients with multiple myeloma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Total-body irradiation was associated with a fourfold increase in neoplasm risk (RR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.40-11.55; P = .0096).

Dr. Hashmi and his colleagues then examined the incidence rates for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database , finding that, even at baseline, the rates of myeloid neoplasms were higher for patients with NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, or MM patients than for the general population of cancer survivors. “Post NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma, the risks are significantly higher to begin with. … We saw a high risk of AML and MDS compared to the SEER controls – risks as high as 100 times greater for auto-transplant patients,” said Dr. Hashmi. “A risk of one hundred times more for MDS was astounding, surprising, unexpected,” he said. The risk of AML, he said, was elevated about 10-50 times in the CIBMTR data.

The cumulative incidence of MDS or AML for NHL was 6% at 10 years post transplant, 4% for Hodgkin lymphoma, and 3% for multiple myeloma.

A limitation of the study, said Dr. Hashmi, was that the investigators did not assess for post-transplant maintenance chemotherapy.

“We have to prospectively assess our transplant patients in a fashion to detect changes early. Or maybe they were present at the time of transplant and we never did sophisticated methods [like] next-generation sequencing” to detect them, he said.

Dr. Hashmi reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

ORLANDO – For post–autologous hematopoietic cell transplant (auto-HCT) patients, the 10-year risk of developing a myeloid neoplasm was as high as 6%, based on a recent review of two large cancer databases.

Older age at transplant, receiving total body irradiation, and receiving multiple lines of chemotherapy before transplant all upped the risk of later cancers, according to a study presented by Shahrukh Hashmi, MD, and his collaborators at the combined annual meetings of the Center for International Blood & Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) and the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

“The guidelines for autologous stem cell transplantation for surveillance for AML [acute myeloid leukemia] and MDS [myelodysplastic syndrome] need to be clearly formulated. We are doing 30,000 autologous transplants a year globally and these patients are at risk for the most feared cancer, which is leukemia and MDS, for which outcomes are very poor,” said Dr. Hashmi of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The researchers examined data from auto-HCT patients with diagnoses of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma to determine the relative risks of developing AML and MDS. The study also explored which patient characteristics and aspects of the conditioning regimen might affect risk for later myeloid neoplasms.

In the dataset of 9,108 patients that Dr. Hashmi and his colleagues obtained from CIBMTR, 3,540 patients had NHL.

“As age progresses, the risk of acquiring myeloid neoplasms increases significantly,” he said, noting that the relative risk (RR) rose to 4.52 for patients aged 55 years and older at the time of transplant (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.63-7.77; P less than .0001).

Patients with NHL who received more than two lines of chemotherapy had approximately double the rate of myeloid cancers (RR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.34-2.78; P = .0004).

The type of conditioning regimen made a difference for NHL patients as well. With total-body irradiation set as the reference at RR = 1, carmustine-etoposide-cytarabine-melphalan (BEAM) or similar therapies were relatively protective, with an RR of 0.59 (95% CI, 0.40-0.87; P = .0083). Also protective were cyclophosphamide-carmustine-etoposide (CBV) and similar therapies (RR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33-0.99; P = .0463).

Age at transplant was a factor among the 4,653 patients with multiple myeloma, with an RR of 2.47 for those transplanted at age 55 years or older (95% CI, 1.55-3.93; P = .0001). Multiple lines of chemotherapy also increased risk, with patients who received more than two lines having an RR of 1.77 for neoplasm (95% CI, 0.04-2.06; P = .0302). Women had less than half the risk of recurrence as men (RR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.28-0.69; P = .0003).

Among the 915 study patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, patients aged 45 years and older at the time of transplant carried an RR of 5.59 for new myeloid neoplasms (95% CI, 2.98-11.70; P less than .0001).

Total-body irradiation was received by 14% of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and by 5% of patients with multiple myeloma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Total-body irradiation was associated with a fourfold increase in neoplasm risk (RR, 4.02; 95% CI, 1.40-11.55; P = .0096).

Dr. Hashmi and his colleagues then examined the incidence rates for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database , finding that, even at baseline, the rates of myeloid neoplasms were higher for patients with NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, or MM patients than for the general population of cancer survivors. “Post NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma, the risks are significantly higher to begin with. … We saw a high risk of AML and MDS compared to the SEER controls – risks as high as 100 times greater for auto-transplant patients,” said Dr. Hashmi. “A risk of one hundred times more for MDS was astounding, surprising, unexpected,” he said. The risk of AML, he said, was elevated about 10-50 times in the CIBMTR data.

The cumulative incidence of MDS or AML for NHL was 6% at 10 years post transplant, 4% for Hodgkin lymphoma, and 3% for multiple myeloma.

A limitation of the study, said Dr. Hashmi, was that the investigators did not assess for post-transplant maintenance chemotherapy.

“We have to prospectively assess our transplant patients in a fashion to detect changes early. Or maybe they were present at the time of transplant and we never did sophisticated methods [like] next-generation sequencing” to detect them, he said.

Dr. Hashmi reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE BMT TANDEM MEETINGS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 10-year cumulative risk for auto-HCT patients with Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma or multiple myeloma was as high at 6%.

Data source: Review of 9,108 patients from an international transplant database.

Disclosures: Dr. Hashmi reported no conflicts of interest.

Selinexor trials placed on partial hold

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on all trials of selinexor (KPT-330).

Selinexor is an inhibitor being evaluated in multiple trials of patients with relapsed and/or refractory hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

While the partial clinical hold remains in effect, patients with stable disease or better may remain on selinexor.

However, no new patients may be enrolled in selinexor trials until the hold is lifted.

The FDA has indicated that the partial clinical hold is due to incomplete information in the existing version of the investigator’s brochure, including an incomplete list of serious adverse events associated with selinexor.

Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor, said it has amended the brochure, updated the informed consent documents accordingly, and submitted the documents to the FDA as requested.

As of March 10, Karyopharm had provided all requested materials to the FDA believed to be required to lift the partial clinical hold. By regulation, the FDA has 30 days from the receipt of Karyopharm’s submission to notify the company whether the partial clinical hold is lifted.

Karyopharm said it is working with the FDA to seek the release of the hold and resume enrollment in its selinexor trials as expeditiously as possible. The company believes its previously disclosed enrollment rates and timelines for its ongoing trials will remain materially unchanged.

About selinexor

Selinexor is a selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) XPO1 antagonist. The drug binds with and inhibits XPO1, leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to induce apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

To date, more than 1900 patients have been treated with selinexor. The drug is currently being evaluated in several trials across multiple cancer indications.

One of these is the phase 2 SOPRA trial, in which selinexor is being compared to investigator’s choice of therapy (1 of 3 potential salvage therapies). The trial is enrolling patients 60 years of age or older with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who are ineligible for standard intensive chemotherapy and/or transplant.

The SADAL study is a phase 2b trial comparing high and low doses of selinexor in patients with relapsed and/or refractory de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who have no therapeutic options of demonstrated clinical benefit.

STORM is a phase 2b trial evaluating selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma (MM). And STOMP is a phase 1b/2 study evaluating selinexor in combination with existing therapies across the broader population in MM.

Karyopharm is also planning a randomized, phase 3 study known as BOSTON. In this trial, researchers will compare selinexor plus bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone to bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone in MM patients who have had 1 to 3 prior lines of therapy.

Additional phase 1, 2, and 3 studies are ongoing or currently planned.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on all trials of selinexor (KPT-330).

Selinexor is an inhibitor being evaluated in multiple trials of patients with relapsed and/or refractory hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

While the partial clinical hold remains in effect, patients with stable disease or better may remain on selinexor.

However, no new patients may be enrolled in selinexor trials until the hold is lifted.

The FDA has indicated that the partial clinical hold is due to incomplete information in the existing version of the investigator’s brochure, including an incomplete list of serious adverse events associated with selinexor.

Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor, said it has amended the brochure, updated the informed consent documents accordingly, and submitted the documents to the FDA as requested.

As of March 10, Karyopharm had provided all requested materials to the FDA believed to be required to lift the partial clinical hold. By regulation, the FDA has 30 days from the receipt of Karyopharm’s submission to notify the company whether the partial clinical hold is lifted.

Karyopharm said it is working with the FDA to seek the release of the hold and resume enrollment in its selinexor trials as expeditiously as possible. The company believes its previously disclosed enrollment rates and timelines for its ongoing trials will remain materially unchanged.

About selinexor

Selinexor is a selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) XPO1 antagonist. The drug binds with and inhibits XPO1, leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to induce apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

To date, more than 1900 patients have been treated with selinexor. The drug is currently being evaluated in several trials across multiple cancer indications.

One of these is the phase 2 SOPRA trial, in which selinexor is being compared to investigator’s choice of therapy (1 of 3 potential salvage therapies). The trial is enrolling patients 60 years of age or older with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who are ineligible for standard intensive chemotherapy and/or transplant.

The SADAL study is a phase 2b trial comparing high and low doses of selinexor in patients with relapsed and/or refractory de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who have no therapeutic options of demonstrated clinical benefit.

STORM is a phase 2b trial evaluating selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma (MM). And STOMP is a phase 1b/2 study evaluating selinexor in combination with existing therapies across the broader population in MM.

Karyopharm is also planning a randomized, phase 3 study known as BOSTON. In this trial, researchers will compare selinexor plus bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone to bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone in MM patients who have had 1 to 3 prior lines of therapy.

Additional phase 1, 2, and 3 studies are ongoing or currently planned.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on all trials of selinexor (KPT-330).

Selinexor is an inhibitor being evaluated in multiple trials of patients with relapsed and/or refractory hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

While the partial clinical hold remains in effect, patients with stable disease or better may remain on selinexor.

However, no new patients may be enrolled in selinexor trials until the hold is lifted.

The FDA has indicated that the partial clinical hold is due to incomplete information in the existing version of the investigator’s brochure, including an incomplete list of serious adverse events associated with selinexor.

Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor, said it has amended the brochure, updated the informed consent documents accordingly, and submitted the documents to the FDA as requested.

As of March 10, Karyopharm had provided all requested materials to the FDA believed to be required to lift the partial clinical hold. By regulation, the FDA has 30 days from the receipt of Karyopharm’s submission to notify the company whether the partial clinical hold is lifted.

Karyopharm said it is working with the FDA to seek the release of the hold and resume enrollment in its selinexor trials as expeditiously as possible. The company believes its previously disclosed enrollment rates and timelines for its ongoing trials will remain materially unchanged.

About selinexor

Selinexor is a selective inhibitor of nuclear export (SINE) XPO1 antagonist. The drug binds with and inhibits XPO1, leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to induce apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

To date, more than 1900 patients have been treated with selinexor. The drug is currently being evaluated in several trials across multiple cancer indications.

One of these is the phase 2 SOPRA trial, in which selinexor is being compared to investigator’s choice of therapy (1 of 3 potential salvage therapies). The trial is enrolling patients 60 years of age or older with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia who are ineligible for standard intensive chemotherapy and/or transplant.

The SADAL study is a phase 2b trial comparing high and low doses of selinexor in patients with relapsed and/or refractory de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who have no therapeutic options of demonstrated clinical benefit.

STORM is a phase 2b trial evaluating selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with heavily pretreated multiple myeloma (MM). And STOMP is a phase 1b/2 study evaluating selinexor in combination with existing therapies across the broader population in MM.

Karyopharm is also planning a randomized, phase 3 study known as BOSTON. In this trial, researchers will compare selinexor plus bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone to bortezomib and low-dose dexamethasone in MM patients who have had 1 to 3 prior lines of therapy.

Additional phase 1, 2, and 3 studies are ongoing or currently planned.

Drug exhibits anti-myeloma activity in mice, humans

An experimental drug called LCL161 stimulates the immune system to fight multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Investigators said LCL161 exhibited “robust” activity in a transgenic myeloma mouse model and in patients with relapsed/refractory MM.

Single-agent LCL161 did not produce responses in MM patients, but patients did respond to treatment with LCL161 and cyclophosphamide.

The investigators also found that single-agent LCL161 provided “long-term anti-tumor protection” in mice, and combining LCL161 with an antibody against PD-1 could cure mice of MM.

“The drug, LCL161, was initially developed to promote tumor death,” said study author Marta Chesi, PhD, of Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale.

“However, we found that the drug does not kill tumor cells directly. Rather, it makes them more visible to the immune system that recognizes them as foreign invaders and eliminates them.”

Dr Chesi and her colleagues explained that the cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAP) 1 and 2 have been identified as potential therapeutic targets in some cancers.

And LCL161 is a small-molecule IAP antagonist that induces tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells. However, the investigators found that LCL161 was not directly cytotoxic to MM cells.

Instead, the drug upregulated tumor-cell-autonomous type I interferon signaling and induced an acute inflammatory response. This led to the activation of macrophages and dendritic cells, which prompted phagocytosis in MM cells.

Results in mice

The investigators first tested LCL161 alone (at a dose previously shown to be well-tolerated) in Vk*MYC transgenic mice with established MM.

The team said they observed a reduction in tumor burden that was comparable to that observed in response to drugs currently used to treat MM—carfilzomib, bortezomib, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, panobinostat, dexamethasone, and pomalidomide.

The investigators then tested the combination of LCL161 and a PD1 antibody in Vk12598-tumor-bearing mice.

The team said the combination was curative in all mice that completed 2 weeks of treatment. In fact, it was more effective than combination treatment with LCL161 and cyclophosphamide.

Results in patients

Dr Chesi and her colleagues conducted a phase 2 trial of LCL161 in 25 patients with relapsed/refractory MM. Patients could receive cyclophosphamide if they failed to respond or progressed after 8 weeks of treatment with LCL161 alone.

The patients’ median age was 68 (range, 47-90), and they had a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1-6). Forty-four percent of patients had high-risk features, 28% had relapsed disease, and 72% had relapsed and refractory disease.

Four patients experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome when they received LCL161 at a dose of 1800 mg weekly, so the dose was lowered to 1200 mg.

None of the patients responded to single-agent LCL161. So 23 of the patients received 500 mg of weekly cyclophosphamide as well.

There was 1 complete response to the combination therapy, 1 very good partial response, 2 partial responses, and 1 minimal response. The median progression-free survival in these patients was 10 months.

Grade 3 adverse events included decrease in neutrophil count (28%), decrease in lymphocyte count (28%), anemia (24%), fatigue (16%), hyperglycemia (12%), syncope (12%), decrease in white blood cell count (12%), decrease in platelet count (8%), increase in lymphocyte count (8%), nausea (4%), vomiting (4%), diarrhea (4%), maculo-papular rash (4%), hypotension (4%), lung infection (4%), pain in extremity (4%), and urticaria (4%).

Grade 4 events included decrease in lymphocyte count (24%), decrease in neutrophil count (8%), decrease in white blood cell count (8%), hyperuricemia (4%), decrease in platelet count (4%), and sepsis (4%).

Based on these results, the investigators said the combination of LCL161 and cyclophosphamide is “an attractive platform for future trials,” and the same is true for LCL161 in combination with anti-PD1 therapy.

The phase 2 trial was sponsored by Mayo Clinic and the National Cancer Institute. Novartis provided LCL161 for this research and supported the trial. ![]()

An experimental drug called LCL161 stimulates the immune system to fight multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Investigators said LCL161 exhibited “robust” activity in a transgenic myeloma mouse model and in patients with relapsed/refractory MM.

Single-agent LCL161 did not produce responses in MM patients, but patients did respond to treatment with LCL161 and cyclophosphamide.

The investigators also found that single-agent LCL161 provided “long-term anti-tumor protection” in mice, and combining LCL161 with an antibody against PD-1 could cure mice of MM.

“The drug, LCL161, was initially developed to promote tumor death,” said study author Marta Chesi, PhD, of Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale.

“However, we found that the drug does not kill tumor cells directly. Rather, it makes them more visible to the immune system that recognizes them as foreign invaders and eliminates them.”

Dr Chesi and her colleagues explained that the cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAP) 1 and 2 have been identified as potential therapeutic targets in some cancers.

And LCL161 is a small-molecule IAP antagonist that induces tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells. However, the investigators found that LCL161 was not directly cytotoxic to MM cells.

Instead, the drug upregulated tumor-cell-autonomous type I interferon signaling and induced an acute inflammatory response. This led to the activation of macrophages and dendritic cells, which prompted phagocytosis in MM cells.

Results in mice

The investigators first tested LCL161 alone (at a dose previously shown to be well-tolerated) in Vk*MYC transgenic mice with established MM.

The team said they observed a reduction in tumor burden that was comparable to that observed in response to drugs currently used to treat MM—carfilzomib, bortezomib, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, panobinostat, dexamethasone, and pomalidomide.

The investigators then tested the combination of LCL161 and a PD1 antibody in Vk12598-tumor-bearing mice.

The team said the combination was curative in all mice that completed 2 weeks of treatment. In fact, it was more effective than combination treatment with LCL161 and cyclophosphamide.

Results in patients

Dr Chesi and her colleagues conducted a phase 2 trial of LCL161 in 25 patients with relapsed/refractory MM. Patients could receive cyclophosphamide if they failed to respond or progressed after 8 weeks of treatment with LCL161 alone.

The patients’ median age was 68 (range, 47-90), and they had a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1-6). Forty-four percent of patients had high-risk features, 28% had relapsed disease, and 72% had relapsed and refractory disease.

Four patients experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome when they received LCL161 at a dose of 1800 mg weekly, so the dose was lowered to 1200 mg.

None of the patients responded to single-agent LCL161. So 23 of the patients received 500 mg of weekly cyclophosphamide as well.

There was 1 complete response to the combination therapy, 1 very good partial response, 2 partial responses, and 1 minimal response. The median progression-free survival in these patients was 10 months.

Grade 3 adverse events included decrease in neutrophil count (28%), decrease in lymphocyte count (28%), anemia (24%), fatigue (16%), hyperglycemia (12%), syncope (12%), decrease in white blood cell count (12%), decrease in platelet count (8%), increase in lymphocyte count (8%), nausea (4%), vomiting (4%), diarrhea (4%), maculo-papular rash (4%), hypotension (4%), lung infection (4%), pain in extremity (4%), and urticaria (4%).

Grade 4 events included decrease in lymphocyte count (24%), decrease in neutrophil count (8%), decrease in white blood cell count (8%), hyperuricemia (4%), decrease in platelet count (4%), and sepsis (4%).

Based on these results, the investigators said the combination of LCL161 and cyclophosphamide is “an attractive platform for future trials,” and the same is true for LCL161 in combination with anti-PD1 therapy.

The phase 2 trial was sponsored by Mayo Clinic and the National Cancer Institute. Novartis provided LCL161 for this research and supported the trial. ![]()

An experimental drug called LCL161 stimulates the immune system to fight multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Investigators said LCL161 exhibited “robust” activity in a transgenic myeloma mouse model and in patients with relapsed/refractory MM.

Single-agent LCL161 did not produce responses in MM patients, but patients did respond to treatment with LCL161 and cyclophosphamide.

The investigators also found that single-agent LCL161 provided “long-term anti-tumor protection” in mice, and combining LCL161 with an antibody against PD-1 could cure mice of MM.

“The drug, LCL161, was initially developed to promote tumor death,” said study author Marta Chesi, PhD, of Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale.

“However, we found that the drug does not kill tumor cells directly. Rather, it makes them more visible to the immune system that recognizes them as foreign invaders and eliminates them.”

Dr Chesi and her colleagues explained that the cellular inhibitors of apoptosis (cIAP) 1 and 2 have been identified as potential therapeutic targets in some cancers.

And LCL161 is a small-molecule IAP antagonist that induces tumor necrosis factor-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells. However, the investigators found that LCL161 was not directly cytotoxic to MM cells.

Instead, the drug upregulated tumor-cell-autonomous type I interferon signaling and induced an acute inflammatory response. This led to the activation of macrophages and dendritic cells, which prompted phagocytosis in MM cells.

Results in mice

The investigators first tested LCL161 alone (at a dose previously shown to be well-tolerated) in Vk*MYC transgenic mice with established MM.

The team said they observed a reduction in tumor burden that was comparable to that observed in response to drugs currently used to treat MM—carfilzomib, bortezomib, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, panobinostat, dexamethasone, and pomalidomide.

The investigators then tested the combination of LCL161 and a PD1 antibody in Vk12598-tumor-bearing mice.

The team said the combination was curative in all mice that completed 2 weeks of treatment. In fact, it was more effective than combination treatment with LCL161 and cyclophosphamide.

Results in patients

Dr Chesi and her colleagues conducted a phase 2 trial of LCL161 in 25 patients with relapsed/refractory MM. Patients could receive cyclophosphamide if they failed to respond or progressed after 8 weeks of treatment with LCL161 alone.

The patients’ median age was 68 (range, 47-90), and they had a median of 3 prior therapies (range, 1-6). Forty-four percent of patients had high-risk features, 28% had relapsed disease, and 72% had relapsed and refractory disease.

Four patients experienced grade 2 cytokine release syndrome when they received LCL161 at a dose of 1800 mg weekly, so the dose was lowered to 1200 mg.