User login

Treating Patients With Multiple Myeloma in the VA

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a portion of a teleconference discussion on treating patients with multiple myeloma in the VHA. The conclusion will be published in the August special issue. For more information and to listen to the conversation, visit FedPrac.com/AVAHOupdates.

Biology of Multiple Myeloma

Dr. Munshi. There are many new advances in understanding of basic molecular and genomic changes in multiple myeloma (MM) that involve signaling pathways that drive MM. We have many drugs that target signaling pathways and the number of newer mutational changes that are identified could have therapeutic as well as prognostic significance.

One of the important findings is the lack of specific myeloma-related mutations. Unlike Waldenström macroglobulinemia, which has about 90% patients with Myd88 mutation, in myeloma we do not see that. The mutation frequency, at the maximum, is in the range of 20% for any one gene, and the 3 to 4 most common genes mutated are KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and P53.

Importantly, if we look at RAS and RAF combined, they target the MEK pathway. So, almost 45% patients have a mutation affecting the MEK pathway, and potentially we can use drugs in the future to see if MEK inhibitors will provide some benefit. And there are anecdotal reports and 1 medium-sized study that has used either a pure MEK inhibitor or a BRAF inhibitor with responses in MM patients. This is a very exciting new area of development.

The second important biological feature in myeloma is clonal shifts. You see multiple clones even at the time of diagnosis. The clonal complexity increases and different clones shift over time with treatment, various other interventions, and changes in myeloma growth patterns. In the future, we cannot just do genomic or cytogenetic analysis one time and sit on it. Over the course of the disease, we may have to repeat it to see if a new clone has evolved. Low-grade or low-risk disease can become a high-grade disease over time.

What is becoming apparent is that sometimes a clone that has almost disappeared reappears after 3, 4, or 5 years. The patient can become resistant to a drug that he or she previously was responsive to with the emergenceof a resistant clone. Three or 4 years later the old sensitive clone can reappear and again be sensitive to the drug that it was not responsive to. The patient may be able to use the same drug again down the line and/or consider similar pathways for targeting. This is one of the major advances that is happening now and is going to inform how we treat patients and how we evaluate patients.

Dr. Mehta. Dr. Munshi, is this going to become “big data?” Are we going to get a lot of information about the molecular changes and findings in our patients not only over time with the evolution of the disease, but also with treatment with various combinations and single agents? Do you think that we at the VA would be able to contribute to some type of banking of material with reference labs that can help to interpret all of the data that we’re going to be able to generate?

Tissue Banking

Dr. Munshi. I think that’s a very important and interesting question. Some mechanisms should be developed so we could not only bank, but also study these genomic patterns. From the VA point of view, there would be some peculiarities that we should understand. One is the age of the patient population—veterans usually end up being older. Number 2, we know the disease is more common in the African American population, and we need to understand why. Tissue banking may help us compare the genomic differences and similarities to understand who may be predisposed to increased frequency of myeloma.

Finally, we still have to keep Agent Orange in mind. Although it is becoming quite an old exposure, a lot of times myeloma occurs. There is a recent paper in JAMA Oncology that showed that incidence of MGUS [monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance] is higher in people who are exposed to Agent Orange. Tissue banking to understand that also would be extremely important, and the banked tissue should be processed to understand what’s happening at the molecular level.

Dr. Ascensão. What’s interesting is that there are some DoD specimens (most of it is serology is my understanding), but we may be able to get other material. Having predisease tissue and watching as the patient develops MGUS, smoldering MM, or MM would allow us to see whether there were already mutational changes in the individual even before Agent Orange exposure or, perhaps, was a result of the exposure.

Dr. Mehta. If we could do that, we could even develop protocols to prevent progression of disease. We could imagine a day when we can see the first event occurring and do something to prevent the progression to MGUS and then to smoldering and overt myeloma. Now, we’re in a particularly good position having a national network to propose this type of national bank.

Dr. Ascensão. We have some advantages as a group with a high prevalence of African American patients, as Dr. Munshi mentioned. And we have the biologic components of pathogenesis with Agent Orange. I think it’s something we can afford. Dr. Roodman, what do people in the field need to know about the biology of myeloma that’s going to help them?

Dr. Roodman. People still don’t understand some of the mechanisms underlying support of myeloma growth by the microenvironment. There are multiple targets that have been examined, and none of them work especially well except for what we already use, proteasome antagonists and immunomodulatory agents. In terms of the biology of myeloma bone disease, healing myeloma bone lesions is still a major issue that needs to be addressed. The question is how to do that. I have a VA grant to look at that question and other groups are actively studying the problem.

How particular myeloma clones become dominant is still a wide-open question. Some researchers are pursuing how the microenvironment selectively allows more aggressive clones to become dominant. Currently, the major research focus is on intrinsic changes in the myeloma cell but the microenvironment may also be contributing to the process.

Relapse

Dr. Ascensão. Years ago, people who relapsed, relapsed with bone disease, which may not be necessarily how people are relapsing these days. We are seeing testicular relapses, hepatic relapses, or pulmonary relapses in individuals who are exposed to some of the new agents. There may be interesting developments in terms of interactions in the hepatocellular microenvironment component and the myeloma cells at that level.

Dr. Roodman. These types of relapses are by myeloma cells that can grow independent of the bone marrow micro-environment and these myeloma cells are behaving more like a lymphoma than a myeloma. Several groups have been studying these types of relapses and are examining the expression of adhesion molecules and loss of expression of adhesion molecules to understand why the myeloma cells aren’t anchored in the marrow. This is just my opinion, but we really need to decide on something that could be done within the VA and ask questions similar to the 2 VA clinical trials Dr. Munshi developed. Those were doable in the VA, and we were able to get support for these trials. I think we have to ask questions that allow us to take advantage of the unique features of the VA patient population.

Dr. Chauncey. I would offer a comment from the clinical perspective. You mentioned that this is an observation with newer therapies, and it’s certainly been an observation in the marrow transplantation setting that the pattern of relapse changes. As treatments become more effective, the pattern of relapse can change. When we first started performing autologous transplantation, the pattern of relapse changed from the chemotherapy used at the time. When we started performing allogeneic transplantation, and to the extent that we use that option, we see a different pattern of relapse with substantially more extramedullary disease. This is really a polyclonal or oligoclonal disease, and as different clones evolve over time, whether it’s immunologically mediated or cytotoxic suppression of the initially dominant clone, you see clonal evolution with a different clinical presentation.

Immune System

Dr. Ascensão. Dr. Munshi, what do you think about the immunologic aspects of the disease in terms of its evolution?

Dr. Munshi. They are both aspects of the impact of myeloma on the immune system as Dr. Chauncey mentioned with progression similar to what Dr. Roodman described in the bone, but with greater impact on immune functions. With both pro- and antifunctions you get more TH17 responses, increased T regulatory cell responses, but also more microenvironmental immune cells change.

The second effect is that the immune cell also affects the myeloma growth. For example, proinflammatory cytokine produce interleukin (IL)6, IL17, IL21, and IL23 that affect myeloma or provide myeloma cell growth and signaling mechanism. Also, the PDC (plasmacytoid dendritic cell) is one of the best bone marrow components that induces and supports myeloma growth. With progression, some of these microenvironmental elements actually play a greater role in having the disease function or progress growth more aggressively than otherwise.

The second important aspect that comes into the picture in the immune and bone marrow microenvironment is the role of selecting the clone. There are literally hundreds of clones in a given patient. Certain clones would be supported preferentially by the immune cells, and in some cases, these aggressive clones become independent and grow without the need of support. That’s when they end up becoming extramedullary disease, which also determines how the myeloma cell is growing with these molecular changes.

Dr. Mehta. Another point of evidence for the immune system dysregulation in allowing growth of myeloma is the impact of some of the new trials. So the KEYSTONE 023 trial, for example, showed that pembrolizumab, the programmed death 1 protein (PD1) inhibitor, helped to prevent progression of disease and actually increased survival. The CAR T [chimeric antigen receptor T-cell] studies, some of which were presented at ASH [American Society of Hematology annual meeting] last December, also are beginning to show promise, almost as well as in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. We could look at the therapeutic response as an indicator of biologic pathogenesis and say, “likely the immune system is a major determinant.”

Standard of Therapy

Dr. Ascensão. The Spanish group published some interesting data on high-risk MGUS and smoldering MM. What do you as investigators and clinicians look at to make a diagnosis of MGUS, and what kind of test would you do in order to separate these different groups? How would you define current standard of therapy, and do you assign specific therapies for specific groups of patients?

Dr. Munshi. The current standard is a 3-drug regimen in the U.S. The most common 3-drug regimen that we all usually use, definitely in younger people, but also in older people with some dose modification, was a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulator with dexamethasone—commonly lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD). One can use carfilzomib also. Now we are beginning to switch to ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, and it can become an all-oral regimen that could be very convenient. We will have a VA study utilizing a similar agent to make an all-oral regimen for treatment.

An alternative people use that has a financial difference is to use a proteasome inhibitor with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, a VCD-like regimen. The study is going to use ixazomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone followed by ixazomib maintenance. That’s the usual induction regimen.

The question is do we do this differently whether the patient is high risk or low risk? My personal bias in the answer is, not really. At the beginning, we will present the best treatment for the patient’s health. If they are older patients with a lot of comorbidities, which is more important, we can use weekly bortezomib instead of using the full dose. We can use subcutaneous weekly bortezomib or a similar 3-drug regimen. And so high risk or low risk doesn’t change how we’re doing the beginning.

The place where the risk stratification comes into the picture is if patients get a transplant. We are beginning to do posttransplant consolidation, and that’s where we would add 2 cycles of consolidation. If consolidation is not done, for high-risk patients one may do maintenance with 2 drugs like bortezomib and lenalidomide alone; whereas in a low-risk patient, you could do lenalidomide only and not use bortezomib with it. This is the impact of risk stratification as far as what we do. It comes more at the later time rather than earlier time point.

Dr. Mehta. There are still a lot of unanswered questions. One area where I think the VA is very good at becoming involved, if we choose to do so, would be some of the drug dosings. For example, dexamethasone used to be used in high dose and the ECOG study showed that you can use it in lower dose weekly rather than 4 days on, 4 days off. The Myeloma In VA (MIVA) group led by Dr. Munshi did a study looking at different doses of lenalidomide. There’s still unanswered questions even in this standard of care regimen that we use where we could try to make the regimen more tolerable for patients.

Dr. Roodman. RVd (modified RVD) has been piloted by Dr. Noopur Raje at Mass General, but I don’t think it’s a large study. She uses it in older patients. To follow-up on what you said, which I think is a really great idea, we could look at RVd as well as 2 doses of dexamethasone, or use oral proteasome antagonists instead.

Dr. Mehta. Yes, to reduce the neurotoxicity.

Dr. Roodman. That is correct. But I think the VA is set up to look at those kinds of questions because most of our patients are older.

Dr. Mehta. They have all the comorbidities.

Dr. Chauncey. We have what we think is an optimal regimen for an optimal patient, and then we have what we often see in the clinic. I’m not sure of the quantitative VA demographics, but if you look at the U.S. myeloma population, the median age is 70 years. While a triplet like

RVd or a carfilzomib-based triplet is probably optimal based on depth of response and the theoretical aspect of suppression of all subclones, it’s not really an accessible regimen for many patients that I see in clinic who are not transplant eligible.

For the nontransplant patients and more frail patients, the doublets or the cyclophosphamide/bortezomib/dexamethasone are reasonable options. I know there are proponents saying that everybody should get RVd or dose-attenuated RVd; I don’t think that’s practical for many of the patients that we see in our clinics.

Dr. Mehta. Why is it not practical in most of your patients? Because they have to come once a week to the clinic?

Dr. Chauncey. That’s part of it, but I find that it’s often too intense with excessive toxicity. The patients are older with comorbidities and they have more limited physiologic reserve. Part of it is coming to clinic, and that’s where all oral regimens such as Rd are useful. I don’t know that if you have an older patient and you see a good response that you’re tracking in terms of their Mspike (monoclonal protein) and their CRAB criteria, that everybody requires the aggressive approach of RVd or a similar triplet with a proteasome inhibitor, an IMiD [immunomodulator drug], and a steroid as induction therapy.

This is true even for some of the older patients who come to autologous transplantation. The data we talk about are in a younger group of patients who can tolerate the full dose of those regimens. The all-oral regimens are attractive, but it’s also quite a financial burden, maybe not to an individual patient, but certainly to the whole health care system. I’m not sure if there is a depth or durability of response advantage for the oral proteasome inhibitor over those available as IV or subcutaneous dosing.

Pricing

Dr. Ascensão. It’s interesting you bring that up because at the Washington DC VAMC, ixazomib may be priced similarly to bortezomib.

Dr. Chauncey. Well that would be very good and very interesting. It’s possible the federal pricing would make it a lot more attractive. It’s not the case outside of the VA, but there the cost burden for oral medication is often shifted to the patient.

Dr. Cosgriff. The price of carfilzomib is about $7,000 to $9,000 per month or per cycle. When we priced ixazomib here in Portland, it actually was more expensive than bortezomib, but it was cheaper than carfilzomib.

Dr. Mehta. If we can do a drug company-sponsored study, the ixazomib people would surely be interested in its usefulness as a triplet in VA patients. It also would be good for the VA patient because you don’t have to come once a week and it has much less neurotoxicity compared to the other proteasome inhibitors, which is a big problem.

Dr. Chauncey. That would be a great study to offer the right patient. I see a lot of myeloma patients in clinic that aren’t really eligible for transplantation. Many of those patients do well on doublet therapy, though they will often require dose adjustments, both down and up, as well as tracking disease status.

Dr. Cosgriff. In Portland, we’re using a lenalidomidebased regimen as a first-line therapy. We’re starting to see more and more individuals starting RVD upfront. There are some select individuals who have diabetic neuropathy or something like that, who may go on just

a lenalidomide plus dexamethasone, leaving out the bortezomib because of neuropathy issues.

Our second-line choice at this point in time has been carfilzomib, but with ixazomib being a cheaper option, we may actually consider switching over to that as a second-line choice. When you look at the clinical trials they cite in the product literature, the grade 1 neuropathy is about 18% with ixazomib and 14% with the placebo arm, so it does add some peripheral neuropathy. Maybe not as much as we would think.

While these oral agents and all-oral regimens are nice to have, we still bring in the patients for clinic and for monitoring of white blood count. It doesn’t necessarily decrease the burden of clinic visits. We still have to get lab draws. Yes, the patient is not sitting in a chair waiting for the bortezomib infusion to be mixed by the pharmacy, but we still have considerations for travel and those types of things.

We treat the entire state of Oregon and parts of southwest Washington. Fortunately, we have community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) and VAMCs in other areas of the state, and we also utilize places like Walla Walla and Spokane, Washington, where we can draw and check labs remotely, which decreases the travel burden, but it still is a burden to the patient to actually go in for lab tests. We’re not looking at ixazomib as a first line currently.

We’re going to wait for data to be published on ixazomib in the first line. In a couple of presentations, researchers have suggested that if you tease the data, ixazomib may be inferior to bortezomib in the first-line setting. It will be interesting to see what the data say for that as far as a first-line setting choice.

Dr. Chauncey. I second what Dr. Cosgriff said. You can’t just give patients 3 bottles of pills and say, “See you in 3 months.” Here in the Northwest we cover large rural areas, and there are many CBOCs whose labs feed directly into our CPRS (Computerized Patient Record System) so it’s very accessible and easy to follow patients that come in less frequently, but that doesn’t change the need for regular clinical follow-up. The other thing I’d say is the noncomparative data of carfilzomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (CRD) is quite compelling in terms of depth and duration of response. We usually don’t want to accept convenience over efficacy. Whether that durability translates long term, we don’t really know, but I think right now, CRD is the best available regimen, again, with the caveat that it’s not really accessible to patients of all ages and performance status.

Dr. Ascensão. At the Washington DC VAMC in our first cycle it is day 1, 4, 8, and 11 with bortezomib, but after that we go pretty much to weekly bortezomib. We also tend to use what I would call lower dose 20 mg dexamethasone in patients over the age of 70 years. And we feel that it is a lot less toxic. We use subcutaneous bortezomib for pretty much everybody else.

Managing Adverse Effects

Dr. Chauncey. I think we’re all using subcutaneous bortezomib at this point. Dexamethasone doesn’t get a lot of independent attention, but there’s no question that, as Dr. Mehta mentioned, the older regimen that we used, the dose-dense dexamethasone of the VAD regimen, was

quite disabling. In addition to obvious hyperglycemia, there were psychiatric problems and, ultimately, profound steroid myopathy that seemed to affect patients in variable fashion. Different patients seem to be more or less susceptible, but after a couple of cycles, it starts to kick in and is progressive.

So we’ve since abandoned those massive doses. But when you look at the ECOG study (E4A03) that really defined the lower dose (40 mg weekly), there’s no question the higher dose was more toxic but also more effective in terms of disease response. While there are many older patients that I would start with a lower dose of dexamethasone, whether it’s with lenalidomide or bortezomib, I keep in mind there can be a steep dose response curve for dexamethasone. If you’re giving 20 mg and you’re not getting the response you need, then you increase the dose. There is definitely a dose response, but the higher doses are just not as well tolerated.

Dr. Cosgriff. I don’t know if other institutions are doing it, but instead of doing 40 mg as a single dose because of patient performance status, providers in Portland will prescribe 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16. They’ll break up that 40 mg dose and give it that way.

Dr. Chauncey. I don’t know if that strategy is biologically equivalent in terms of antimyeloma activity or less toxic in terms of myopathy. There’s almost always some disease marker to track, so that whether you’re using the serum free-light chain assay or serum protein electrophoresis, you can see if the strategy you’re using is working in real time.

Dr. Cosgriff. I’ve never known whether it’s been shown to be more efficacious or if it’s just a way of getting around some of the adverse effects. However, it does pose some alternate challenges. With higher doses of steroids, you’re looking at 2 days where the patient can become hyperglycemic, if not, a little bit longer.

The other thing with it is that adding on that extra day of dexamethasone can interfere with some other drugs and some other therapies. In individuals who have had a deep vein thrombosis for whatever reason and they’re on warfarin, now we have an agent that really screws up our warfarin monitoring. We would have to consider switching them to another agent.

Thrombosis

Dr. Mehta. It’s also prothrombotic.

Dr. Chauncey. If you actually ask the patient, independent of the hyperglycemia, independent of the myopathy, independent of psychosis, but just quality of life, they’ll typically tell you that the on-and-off of steroids is the worst part of the regimen. It’s often the roller coaster ride of short-term hypomania followed by dysphoria.

Dr. Mehta. And the lack of sleep. They describe it as being out of their skin.

Dr. Chauncey. They are. And as soon as they stop, often there is a depression.

Dr. Mehta. It is very, very difficult. And some actually develop psychosis.

Dr. Ascensão. We all use some form of acyclovir or its derivative for the prevention of shingles in patients exposed to the proteasome inhibitors. We use aspirin, usually low dose (81 mg), for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. But is anybody using other anticoagulants or putting everybody prophylactically on proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) or just seeing how people do first and then adjusting?

Dr. Chauncey. I typically use conventional dose aspirin, and if there’s breakthrough thrombosis, the first response should be that it is not the best regimen for this patient. Sometimes you have to go back to it, and if someone’s an anticoagulation candidate, then full anticoagulation is

needed if that’s the best regimen. Usually if there’s a breakthrough thrombosis, it is a deal breaker, and you’re ready to move on to a nonthrombogenic regimen.

There has been an observation (there is some biological basis to back this up) that if you give bortezomib with an IMiD, the regimen became less thrombogenic than with the IMiD and dexamethasone alone.

Dr. Ascensão. On aspirin, even if they’re on an IMiD plus a proteasome inhibitor, I just don’t know that the data are good enough for us to avoid it at this point in time. And I don’t necessarily put people on a PPI unless they’ve got added gastrointestinal problems and unless they have associated heartburn or dyspepsia symptoms.

Dr. Mehta. I use low-dose aspirin in every patient. And if they breakthrough, they go on full anticoagulation usually with a new oral anticoagulant. I use PPIs only if needed, although most of them do need it, and, of course, bisphosphonates so the bone protective aspect.

Click to read the digital edition.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a portion of a teleconference discussion on treating patients with multiple myeloma in the VHA. The conclusion will be published in the August special issue. For more information and to listen to the conversation, visit FedPrac.com/AVAHOupdates.

Biology of Multiple Myeloma

Dr. Munshi. There are many new advances in understanding of basic molecular and genomic changes in multiple myeloma (MM) that involve signaling pathways that drive MM. We have many drugs that target signaling pathways and the number of newer mutational changes that are identified could have therapeutic as well as prognostic significance.

One of the important findings is the lack of specific myeloma-related mutations. Unlike Waldenström macroglobulinemia, which has about 90% patients with Myd88 mutation, in myeloma we do not see that. The mutation frequency, at the maximum, is in the range of 20% for any one gene, and the 3 to 4 most common genes mutated are KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and P53.

Importantly, if we look at RAS and RAF combined, they target the MEK pathway. So, almost 45% patients have a mutation affecting the MEK pathway, and potentially we can use drugs in the future to see if MEK inhibitors will provide some benefit. And there are anecdotal reports and 1 medium-sized study that has used either a pure MEK inhibitor or a BRAF inhibitor with responses in MM patients. This is a very exciting new area of development.

The second important biological feature in myeloma is clonal shifts. You see multiple clones even at the time of diagnosis. The clonal complexity increases and different clones shift over time with treatment, various other interventions, and changes in myeloma growth patterns. In the future, we cannot just do genomic or cytogenetic analysis one time and sit on it. Over the course of the disease, we may have to repeat it to see if a new clone has evolved. Low-grade or low-risk disease can become a high-grade disease over time.

What is becoming apparent is that sometimes a clone that has almost disappeared reappears after 3, 4, or 5 years. The patient can become resistant to a drug that he or she previously was responsive to with the emergenceof a resistant clone. Three or 4 years later the old sensitive clone can reappear and again be sensitive to the drug that it was not responsive to. The patient may be able to use the same drug again down the line and/or consider similar pathways for targeting. This is one of the major advances that is happening now and is going to inform how we treat patients and how we evaluate patients.

Dr. Mehta. Dr. Munshi, is this going to become “big data?” Are we going to get a lot of information about the molecular changes and findings in our patients not only over time with the evolution of the disease, but also with treatment with various combinations and single agents? Do you think that we at the VA would be able to contribute to some type of banking of material with reference labs that can help to interpret all of the data that we’re going to be able to generate?

Tissue Banking

Dr. Munshi. I think that’s a very important and interesting question. Some mechanisms should be developed so we could not only bank, but also study these genomic patterns. From the VA point of view, there would be some peculiarities that we should understand. One is the age of the patient population—veterans usually end up being older. Number 2, we know the disease is more common in the African American population, and we need to understand why. Tissue banking may help us compare the genomic differences and similarities to understand who may be predisposed to increased frequency of myeloma.

Finally, we still have to keep Agent Orange in mind. Although it is becoming quite an old exposure, a lot of times myeloma occurs. There is a recent paper in JAMA Oncology that showed that incidence of MGUS [monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance] is higher in people who are exposed to Agent Orange. Tissue banking to understand that also would be extremely important, and the banked tissue should be processed to understand what’s happening at the molecular level.

Dr. Ascensão. What’s interesting is that there are some DoD specimens (most of it is serology is my understanding), but we may be able to get other material. Having predisease tissue and watching as the patient develops MGUS, smoldering MM, or MM would allow us to see whether there were already mutational changes in the individual even before Agent Orange exposure or, perhaps, was a result of the exposure.

Dr. Mehta. If we could do that, we could even develop protocols to prevent progression of disease. We could imagine a day when we can see the first event occurring and do something to prevent the progression to MGUS and then to smoldering and overt myeloma. Now, we’re in a particularly good position having a national network to propose this type of national bank.

Dr. Ascensão. We have some advantages as a group with a high prevalence of African American patients, as Dr. Munshi mentioned. And we have the biologic components of pathogenesis with Agent Orange. I think it’s something we can afford. Dr. Roodman, what do people in the field need to know about the biology of myeloma that’s going to help them?

Dr. Roodman. People still don’t understand some of the mechanisms underlying support of myeloma growth by the microenvironment. There are multiple targets that have been examined, and none of them work especially well except for what we already use, proteasome antagonists and immunomodulatory agents. In terms of the biology of myeloma bone disease, healing myeloma bone lesions is still a major issue that needs to be addressed. The question is how to do that. I have a VA grant to look at that question and other groups are actively studying the problem.

How particular myeloma clones become dominant is still a wide-open question. Some researchers are pursuing how the microenvironment selectively allows more aggressive clones to become dominant. Currently, the major research focus is on intrinsic changes in the myeloma cell but the microenvironment may also be contributing to the process.

Relapse

Dr. Ascensão. Years ago, people who relapsed, relapsed with bone disease, which may not be necessarily how people are relapsing these days. We are seeing testicular relapses, hepatic relapses, or pulmonary relapses in individuals who are exposed to some of the new agents. There may be interesting developments in terms of interactions in the hepatocellular microenvironment component and the myeloma cells at that level.

Dr. Roodman. These types of relapses are by myeloma cells that can grow independent of the bone marrow micro-environment and these myeloma cells are behaving more like a lymphoma than a myeloma. Several groups have been studying these types of relapses and are examining the expression of adhesion molecules and loss of expression of adhesion molecules to understand why the myeloma cells aren’t anchored in the marrow. This is just my opinion, but we really need to decide on something that could be done within the VA and ask questions similar to the 2 VA clinical trials Dr. Munshi developed. Those were doable in the VA, and we were able to get support for these trials. I think we have to ask questions that allow us to take advantage of the unique features of the VA patient population.

Dr. Chauncey. I would offer a comment from the clinical perspective. You mentioned that this is an observation with newer therapies, and it’s certainly been an observation in the marrow transplantation setting that the pattern of relapse changes. As treatments become more effective, the pattern of relapse can change. When we first started performing autologous transplantation, the pattern of relapse changed from the chemotherapy used at the time. When we started performing allogeneic transplantation, and to the extent that we use that option, we see a different pattern of relapse with substantially more extramedullary disease. This is really a polyclonal or oligoclonal disease, and as different clones evolve over time, whether it’s immunologically mediated or cytotoxic suppression of the initially dominant clone, you see clonal evolution with a different clinical presentation.

Immune System

Dr. Ascensão. Dr. Munshi, what do you think about the immunologic aspects of the disease in terms of its evolution?

Dr. Munshi. They are both aspects of the impact of myeloma on the immune system as Dr. Chauncey mentioned with progression similar to what Dr. Roodman described in the bone, but with greater impact on immune functions. With both pro- and antifunctions you get more TH17 responses, increased T regulatory cell responses, but also more microenvironmental immune cells change.

The second effect is that the immune cell also affects the myeloma growth. For example, proinflammatory cytokine produce interleukin (IL)6, IL17, IL21, and IL23 that affect myeloma or provide myeloma cell growth and signaling mechanism. Also, the PDC (plasmacytoid dendritic cell) is one of the best bone marrow components that induces and supports myeloma growth. With progression, some of these microenvironmental elements actually play a greater role in having the disease function or progress growth more aggressively than otherwise.

The second important aspect that comes into the picture in the immune and bone marrow microenvironment is the role of selecting the clone. There are literally hundreds of clones in a given patient. Certain clones would be supported preferentially by the immune cells, and in some cases, these aggressive clones become independent and grow without the need of support. That’s when they end up becoming extramedullary disease, which also determines how the myeloma cell is growing with these molecular changes.

Dr. Mehta. Another point of evidence for the immune system dysregulation in allowing growth of myeloma is the impact of some of the new trials. So the KEYSTONE 023 trial, for example, showed that pembrolizumab, the programmed death 1 protein (PD1) inhibitor, helped to prevent progression of disease and actually increased survival. The CAR T [chimeric antigen receptor T-cell] studies, some of which were presented at ASH [American Society of Hematology annual meeting] last December, also are beginning to show promise, almost as well as in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. We could look at the therapeutic response as an indicator of biologic pathogenesis and say, “likely the immune system is a major determinant.”

Standard of Therapy

Dr. Ascensão. The Spanish group published some interesting data on high-risk MGUS and smoldering MM. What do you as investigators and clinicians look at to make a diagnosis of MGUS, and what kind of test would you do in order to separate these different groups? How would you define current standard of therapy, and do you assign specific therapies for specific groups of patients?

Dr. Munshi. The current standard is a 3-drug regimen in the U.S. The most common 3-drug regimen that we all usually use, definitely in younger people, but also in older people with some dose modification, was a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulator with dexamethasone—commonly lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD). One can use carfilzomib also. Now we are beginning to switch to ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, and it can become an all-oral regimen that could be very convenient. We will have a VA study utilizing a similar agent to make an all-oral regimen for treatment.

An alternative people use that has a financial difference is to use a proteasome inhibitor with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, a VCD-like regimen. The study is going to use ixazomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone followed by ixazomib maintenance. That’s the usual induction regimen.

The question is do we do this differently whether the patient is high risk or low risk? My personal bias in the answer is, not really. At the beginning, we will present the best treatment for the patient’s health. If they are older patients with a lot of comorbidities, which is more important, we can use weekly bortezomib instead of using the full dose. We can use subcutaneous weekly bortezomib or a similar 3-drug regimen. And so high risk or low risk doesn’t change how we’re doing the beginning.

The place where the risk stratification comes into the picture is if patients get a transplant. We are beginning to do posttransplant consolidation, and that’s where we would add 2 cycles of consolidation. If consolidation is not done, for high-risk patients one may do maintenance with 2 drugs like bortezomib and lenalidomide alone; whereas in a low-risk patient, you could do lenalidomide only and not use bortezomib with it. This is the impact of risk stratification as far as what we do. It comes more at the later time rather than earlier time point.

Dr. Mehta. There are still a lot of unanswered questions. One area where I think the VA is very good at becoming involved, if we choose to do so, would be some of the drug dosings. For example, dexamethasone used to be used in high dose and the ECOG study showed that you can use it in lower dose weekly rather than 4 days on, 4 days off. The Myeloma In VA (MIVA) group led by Dr. Munshi did a study looking at different doses of lenalidomide. There’s still unanswered questions even in this standard of care regimen that we use where we could try to make the regimen more tolerable for patients.

Dr. Roodman. RVd (modified RVD) has been piloted by Dr. Noopur Raje at Mass General, but I don’t think it’s a large study. She uses it in older patients. To follow-up on what you said, which I think is a really great idea, we could look at RVd as well as 2 doses of dexamethasone, or use oral proteasome antagonists instead.

Dr. Mehta. Yes, to reduce the neurotoxicity.

Dr. Roodman. That is correct. But I think the VA is set up to look at those kinds of questions because most of our patients are older.

Dr. Mehta. They have all the comorbidities.

Dr. Chauncey. We have what we think is an optimal regimen for an optimal patient, and then we have what we often see in the clinic. I’m not sure of the quantitative VA demographics, but if you look at the U.S. myeloma population, the median age is 70 years. While a triplet like

RVd or a carfilzomib-based triplet is probably optimal based on depth of response and the theoretical aspect of suppression of all subclones, it’s not really an accessible regimen for many patients that I see in clinic who are not transplant eligible.

For the nontransplant patients and more frail patients, the doublets or the cyclophosphamide/bortezomib/dexamethasone are reasonable options. I know there are proponents saying that everybody should get RVd or dose-attenuated RVd; I don’t think that’s practical for many of the patients that we see in our clinics.

Dr. Mehta. Why is it not practical in most of your patients? Because they have to come once a week to the clinic?

Dr. Chauncey. That’s part of it, but I find that it’s often too intense with excessive toxicity. The patients are older with comorbidities and they have more limited physiologic reserve. Part of it is coming to clinic, and that’s where all oral regimens such as Rd are useful. I don’t know that if you have an older patient and you see a good response that you’re tracking in terms of their Mspike (monoclonal protein) and their CRAB criteria, that everybody requires the aggressive approach of RVd or a similar triplet with a proteasome inhibitor, an IMiD [immunomodulator drug], and a steroid as induction therapy.

This is true even for some of the older patients who come to autologous transplantation. The data we talk about are in a younger group of patients who can tolerate the full dose of those regimens. The all-oral regimens are attractive, but it’s also quite a financial burden, maybe not to an individual patient, but certainly to the whole health care system. I’m not sure if there is a depth or durability of response advantage for the oral proteasome inhibitor over those available as IV or subcutaneous dosing.

Pricing

Dr. Ascensão. It’s interesting you bring that up because at the Washington DC VAMC, ixazomib may be priced similarly to bortezomib.

Dr. Chauncey. Well that would be very good and very interesting. It’s possible the federal pricing would make it a lot more attractive. It’s not the case outside of the VA, but there the cost burden for oral medication is often shifted to the patient.

Dr. Cosgriff. The price of carfilzomib is about $7,000 to $9,000 per month or per cycle. When we priced ixazomib here in Portland, it actually was more expensive than bortezomib, but it was cheaper than carfilzomib.

Dr. Mehta. If we can do a drug company-sponsored study, the ixazomib people would surely be interested in its usefulness as a triplet in VA patients. It also would be good for the VA patient because you don’t have to come once a week and it has much less neurotoxicity compared to the other proteasome inhibitors, which is a big problem.

Dr. Chauncey. That would be a great study to offer the right patient. I see a lot of myeloma patients in clinic that aren’t really eligible for transplantation. Many of those patients do well on doublet therapy, though they will often require dose adjustments, both down and up, as well as tracking disease status.

Dr. Cosgriff. In Portland, we’re using a lenalidomidebased regimen as a first-line therapy. We’re starting to see more and more individuals starting RVD upfront. There are some select individuals who have diabetic neuropathy or something like that, who may go on just

a lenalidomide plus dexamethasone, leaving out the bortezomib because of neuropathy issues.

Our second-line choice at this point in time has been carfilzomib, but with ixazomib being a cheaper option, we may actually consider switching over to that as a second-line choice. When you look at the clinical trials they cite in the product literature, the grade 1 neuropathy is about 18% with ixazomib and 14% with the placebo arm, so it does add some peripheral neuropathy. Maybe not as much as we would think.

While these oral agents and all-oral regimens are nice to have, we still bring in the patients for clinic and for monitoring of white blood count. It doesn’t necessarily decrease the burden of clinic visits. We still have to get lab draws. Yes, the patient is not sitting in a chair waiting for the bortezomib infusion to be mixed by the pharmacy, but we still have considerations for travel and those types of things.

We treat the entire state of Oregon and parts of southwest Washington. Fortunately, we have community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) and VAMCs in other areas of the state, and we also utilize places like Walla Walla and Spokane, Washington, where we can draw and check labs remotely, which decreases the travel burden, but it still is a burden to the patient to actually go in for lab tests. We’re not looking at ixazomib as a first line currently.

We’re going to wait for data to be published on ixazomib in the first line. In a couple of presentations, researchers have suggested that if you tease the data, ixazomib may be inferior to bortezomib in the first-line setting. It will be interesting to see what the data say for that as far as a first-line setting choice.

Dr. Chauncey. I second what Dr. Cosgriff said. You can’t just give patients 3 bottles of pills and say, “See you in 3 months.” Here in the Northwest we cover large rural areas, and there are many CBOCs whose labs feed directly into our CPRS (Computerized Patient Record System) so it’s very accessible and easy to follow patients that come in less frequently, but that doesn’t change the need for regular clinical follow-up. The other thing I’d say is the noncomparative data of carfilzomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (CRD) is quite compelling in terms of depth and duration of response. We usually don’t want to accept convenience over efficacy. Whether that durability translates long term, we don’t really know, but I think right now, CRD is the best available regimen, again, with the caveat that it’s not really accessible to patients of all ages and performance status.

Dr. Ascensão. At the Washington DC VAMC in our first cycle it is day 1, 4, 8, and 11 with bortezomib, but after that we go pretty much to weekly bortezomib. We also tend to use what I would call lower dose 20 mg dexamethasone in patients over the age of 70 years. And we feel that it is a lot less toxic. We use subcutaneous bortezomib for pretty much everybody else.

Managing Adverse Effects

Dr. Chauncey. I think we’re all using subcutaneous bortezomib at this point. Dexamethasone doesn’t get a lot of independent attention, but there’s no question that, as Dr. Mehta mentioned, the older regimen that we used, the dose-dense dexamethasone of the VAD regimen, was

quite disabling. In addition to obvious hyperglycemia, there were psychiatric problems and, ultimately, profound steroid myopathy that seemed to affect patients in variable fashion. Different patients seem to be more or less susceptible, but after a couple of cycles, it starts to kick in and is progressive.

So we’ve since abandoned those massive doses. But when you look at the ECOG study (E4A03) that really defined the lower dose (40 mg weekly), there’s no question the higher dose was more toxic but also more effective in terms of disease response. While there are many older patients that I would start with a lower dose of dexamethasone, whether it’s with lenalidomide or bortezomib, I keep in mind there can be a steep dose response curve for dexamethasone. If you’re giving 20 mg and you’re not getting the response you need, then you increase the dose. There is definitely a dose response, but the higher doses are just not as well tolerated.

Dr. Cosgriff. I don’t know if other institutions are doing it, but instead of doing 40 mg as a single dose because of patient performance status, providers in Portland will prescribe 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16. They’ll break up that 40 mg dose and give it that way.

Dr. Chauncey. I don’t know if that strategy is biologically equivalent in terms of antimyeloma activity or less toxic in terms of myopathy. There’s almost always some disease marker to track, so that whether you’re using the serum free-light chain assay or serum protein electrophoresis, you can see if the strategy you’re using is working in real time.

Dr. Cosgriff. I’ve never known whether it’s been shown to be more efficacious or if it’s just a way of getting around some of the adverse effects. However, it does pose some alternate challenges. With higher doses of steroids, you’re looking at 2 days where the patient can become hyperglycemic, if not, a little bit longer.

The other thing with it is that adding on that extra day of dexamethasone can interfere with some other drugs and some other therapies. In individuals who have had a deep vein thrombosis for whatever reason and they’re on warfarin, now we have an agent that really screws up our warfarin monitoring. We would have to consider switching them to another agent.

Thrombosis

Dr. Mehta. It’s also prothrombotic.

Dr. Chauncey. If you actually ask the patient, independent of the hyperglycemia, independent of the myopathy, independent of psychosis, but just quality of life, they’ll typically tell you that the on-and-off of steroids is the worst part of the regimen. It’s often the roller coaster ride of short-term hypomania followed by dysphoria.

Dr. Mehta. And the lack of sleep. They describe it as being out of their skin.

Dr. Chauncey. They are. And as soon as they stop, often there is a depression.

Dr. Mehta. It is very, very difficult. And some actually develop psychosis.

Dr. Ascensão. We all use some form of acyclovir or its derivative for the prevention of shingles in patients exposed to the proteasome inhibitors. We use aspirin, usually low dose (81 mg), for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. But is anybody using other anticoagulants or putting everybody prophylactically on proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) or just seeing how people do first and then adjusting?

Dr. Chauncey. I typically use conventional dose aspirin, and if there’s breakthrough thrombosis, the first response should be that it is not the best regimen for this patient. Sometimes you have to go back to it, and if someone’s an anticoagulation candidate, then full anticoagulation is

needed if that’s the best regimen. Usually if there’s a breakthrough thrombosis, it is a deal breaker, and you’re ready to move on to a nonthrombogenic regimen.

There has been an observation (there is some biological basis to back this up) that if you give bortezomib with an IMiD, the regimen became less thrombogenic than with the IMiD and dexamethasone alone.

Dr. Ascensão. On aspirin, even if they’re on an IMiD plus a proteasome inhibitor, I just don’t know that the data are good enough for us to avoid it at this point in time. And I don’t necessarily put people on a PPI unless they’ve got added gastrointestinal problems and unless they have associated heartburn or dyspepsia symptoms.

Dr. Mehta. I use low-dose aspirin in every patient. And if they breakthrough, they go on full anticoagulation usually with a new oral anticoagulant. I use PPIs only if needed, although most of them do need it, and, of course, bisphosphonates so the bone protective aspect.

Click to read the digital edition.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a portion of a teleconference discussion on treating patients with multiple myeloma in the VHA. The conclusion will be published in the August special issue. For more information and to listen to the conversation, visit FedPrac.com/AVAHOupdates.

Biology of Multiple Myeloma

Dr. Munshi. There are many new advances in understanding of basic molecular and genomic changes in multiple myeloma (MM) that involve signaling pathways that drive MM. We have many drugs that target signaling pathways and the number of newer mutational changes that are identified could have therapeutic as well as prognostic significance.

One of the important findings is the lack of specific myeloma-related mutations. Unlike Waldenström macroglobulinemia, which has about 90% patients with Myd88 mutation, in myeloma we do not see that. The mutation frequency, at the maximum, is in the range of 20% for any one gene, and the 3 to 4 most common genes mutated are KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and P53.

Importantly, if we look at RAS and RAF combined, they target the MEK pathway. So, almost 45% patients have a mutation affecting the MEK pathway, and potentially we can use drugs in the future to see if MEK inhibitors will provide some benefit. And there are anecdotal reports and 1 medium-sized study that has used either a pure MEK inhibitor or a BRAF inhibitor with responses in MM patients. This is a very exciting new area of development.

The second important biological feature in myeloma is clonal shifts. You see multiple clones even at the time of diagnosis. The clonal complexity increases and different clones shift over time with treatment, various other interventions, and changes in myeloma growth patterns. In the future, we cannot just do genomic or cytogenetic analysis one time and sit on it. Over the course of the disease, we may have to repeat it to see if a new clone has evolved. Low-grade or low-risk disease can become a high-grade disease over time.

What is becoming apparent is that sometimes a clone that has almost disappeared reappears after 3, 4, or 5 years. The patient can become resistant to a drug that he or she previously was responsive to with the emergenceof a resistant clone. Three or 4 years later the old sensitive clone can reappear and again be sensitive to the drug that it was not responsive to. The patient may be able to use the same drug again down the line and/or consider similar pathways for targeting. This is one of the major advances that is happening now and is going to inform how we treat patients and how we evaluate patients.

Dr. Mehta. Dr. Munshi, is this going to become “big data?” Are we going to get a lot of information about the molecular changes and findings in our patients not only over time with the evolution of the disease, but also with treatment with various combinations and single agents? Do you think that we at the VA would be able to contribute to some type of banking of material with reference labs that can help to interpret all of the data that we’re going to be able to generate?

Tissue Banking

Dr. Munshi. I think that’s a very important and interesting question. Some mechanisms should be developed so we could not only bank, but also study these genomic patterns. From the VA point of view, there would be some peculiarities that we should understand. One is the age of the patient population—veterans usually end up being older. Number 2, we know the disease is more common in the African American population, and we need to understand why. Tissue banking may help us compare the genomic differences and similarities to understand who may be predisposed to increased frequency of myeloma.

Finally, we still have to keep Agent Orange in mind. Although it is becoming quite an old exposure, a lot of times myeloma occurs. There is a recent paper in JAMA Oncology that showed that incidence of MGUS [monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance] is higher in people who are exposed to Agent Orange. Tissue banking to understand that also would be extremely important, and the banked tissue should be processed to understand what’s happening at the molecular level.

Dr. Ascensão. What’s interesting is that there are some DoD specimens (most of it is serology is my understanding), but we may be able to get other material. Having predisease tissue and watching as the patient develops MGUS, smoldering MM, or MM would allow us to see whether there were already mutational changes in the individual even before Agent Orange exposure or, perhaps, was a result of the exposure.

Dr. Mehta. If we could do that, we could even develop protocols to prevent progression of disease. We could imagine a day when we can see the first event occurring and do something to prevent the progression to MGUS and then to smoldering and overt myeloma. Now, we’re in a particularly good position having a national network to propose this type of national bank.

Dr. Ascensão. We have some advantages as a group with a high prevalence of African American patients, as Dr. Munshi mentioned. And we have the biologic components of pathogenesis with Agent Orange. I think it’s something we can afford. Dr. Roodman, what do people in the field need to know about the biology of myeloma that’s going to help them?

Dr. Roodman. People still don’t understand some of the mechanisms underlying support of myeloma growth by the microenvironment. There are multiple targets that have been examined, and none of them work especially well except for what we already use, proteasome antagonists and immunomodulatory agents. In terms of the biology of myeloma bone disease, healing myeloma bone lesions is still a major issue that needs to be addressed. The question is how to do that. I have a VA grant to look at that question and other groups are actively studying the problem.

How particular myeloma clones become dominant is still a wide-open question. Some researchers are pursuing how the microenvironment selectively allows more aggressive clones to become dominant. Currently, the major research focus is on intrinsic changes in the myeloma cell but the microenvironment may also be contributing to the process.

Relapse

Dr. Ascensão. Years ago, people who relapsed, relapsed with bone disease, which may not be necessarily how people are relapsing these days. We are seeing testicular relapses, hepatic relapses, or pulmonary relapses in individuals who are exposed to some of the new agents. There may be interesting developments in terms of interactions in the hepatocellular microenvironment component and the myeloma cells at that level.

Dr. Roodman. These types of relapses are by myeloma cells that can grow independent of the bone marrow micro-environment and these myeloma cells are behaving more like a lymphoma than a myeloma. Several groups have been studying these types of relapses and are examining the expression of adhesion molecules and loss of expression of adhesion molecules to understand why the myeloma cells aren’t anchored in the marrow. This is just my opinion, but we really need to decide on something that could be done within the VA and ask questions similar to the 2 VA clinical trials Dr. Munshi developed. Those were doable in the VA, and we were able to get support for these trials. I think we have to ask questions that allow us to take advantage of the unique features of the VA patient population.

Dr. Chauncey. I would offer a comment from the clinical perspective. You mentioned that this is an observation with newer therapies, and it’s certainly been an observation in the marrow transplantation setting that the pattern of relapse changes. As treatments become more effective, the pattern of relapse can change. When we first started performing autologous transplantation, the pattern of relapse changed from the chemotherapy used at the time. When we started performing allogeneic transplantation, and to the extent that we use that option, we see a different pattern of relapse with substantially more extramedullary disease. This is really a polyclonal or oligoclonal disease, and as different clones evolve over time, whether it’s immunologically mediated or cytotoxic suppression of the initially dominant clone, you see clonal evolution with a different clinical presentation.

Immune System

Dr. Ascensão. Dr. Munshi, what do you think about the immunologic aspects of the disease in terms of its evolution?

Dr. Munshi. They are both aspects of the impact of myeloma on the immune system as Dr. Chauncey mentioned with progression similar to what Dr. Roodman described in the bone, but with greater impact on immune functions. With both pro- and antifunctions you get more TH17 responses, increased T regulatory cell responses, but also more microenvironmental immune cells change.

The second effect is that the immune cell also affects the myeloma growth. For example, proinflammatory cytokine produce interleukin (IL)6, IL17, IL21, and IL23 that affect myeloma or provide myeloma cell growth and signaling mechanism. Also, the PDC (plasmacytoid dendritic cell) is one of the best bone marrow components that induces and supports myeloma growth. With progression, some of these microenvironmental elements actually play a greater role in having the disease function or progress growth more aggressively than otherwise.

The second important aspect that comes into the picture in the immune and bone marrow microenvironment is the role of selecting the clone. There are literally hundreds of clones in a given patient. Certain clones would be supported preferentially by the immune cells, and in some cases, these aggressive clones become independent and grow without the need of support. That’s when they end up becoming extramedullary disease, which also determines how the myeloma cell is growing with these molecular changes.

Dr. Mehta. Another point of evidence for the immune system dysregulation in allowing growth of myeloma is the impact of some of the new trials. So the KEYSTONE 023 trial, for example, showed that pembrolizumab, the programmed death 1 protein (PD1) inhibitor, helped to prevent progression of disease and actually increased survival. The CAR T [chimeric antigen receptor T-cell] studies, some of which were presented at ASH [American Society of Hematology annual meeting] last December, also are beginning to show promise, almost as well as in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. We could look at the therapeutic response as an indicator of biologic pathogenesis and say, “likely the immune system is a major determinant.”

Standard of Therapy

Dr. Ascensão. The Spanish group published some interesting data on high-risk MGUS and smoldering MM. What do you as investigators and clinicians look at to make a diagnosis of MGUS, and what kind of test would you do in order to separate these different groups? How would you define current standard of therapy, and do you assign specific therapies for specific groups of patients?

Dr. Munshi. The current standard is a 3-drug regimen in the U.S. The most common 3-drug regimen that we all usually use, definitely in younger people, but also in older people with some dose modification, was a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulator with dexamethasone—commonly lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (RVD). One can use carfilzomib also. Now we are beginning to switch to ixazomib, an oral proteasome inhibitor, and it can become an all-oral regimen that could be very convenient. We will have a VA study utilizing a similar agent to make an all-oral regimen for treatment.

An alternative people use that has a financial difference is to use a proteasome inhibitor with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, a VCD-like regimen. The study is going to use ixazomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone followed by ixazomib maintenance. That’s the usual induction regimen.

The question is do we do this differently whether the patient is high risk or low risk? My personal bias in the answer is, not really. At the beginning, we will present the best treatment for the patient’s health. If they are older patients with a lot of comorbidities, which is more important, we can use weekly bortezomib instead of using the full dose. We can use subcutaneous weekly bortezomib or a similar 3-drug regimen. And so high risk or low risk doesn’t change how we’re doing the beginning.

The place where the risk stratification comes into the picture is if patients get a transplant. We are beginning to do posttransplant consolidation, and that’s where we would add 2 cycles of consolidation. If consolidation is not done, for high-risk patients one may do maintenance with 2 drugs like bortezomib and lenalidomide alone; whereas in a low-risk patient, you could do lenalidomide only and not use bortezomib with it. This is the impact of risk stratification as far as what we do. It comes more at the later time rather than earlier time point.

Dr. Mehta. There are still a lot of unanswered questions. One area where I think the VA is very good at becoming involved, if we choose to do so, would be some of the drug dosings. For example, dexamethasone used to be used in high dose and the ECOG study showed that you can use it in lower dose weekly rather than 4 days on, 4 days off. The Myeloma In VA (MIVA) group led by Dr. Munshi did a study looking at different doses of lenalidomide. There’s still unanswered questions even in this standard of care regimen that we use where we could try to make the regimen more tolerable for patients.

Dr. Roodman. RVd (modified RVD) has been piloted by Dr. Noopur Raje at Mass General, but I don’t think it’s a large study. She uses it in older patients. To follow-up on what you said, which I think is a really great idea, we could look at RVd as well as 2 doses of dexamethasone, or use oral proteasome antagonists instead.

Dr. Mehta. Yes, to reduce the neurotoxicity.

Dr. Roodman. That is correct. But I think the VA is set up to look at those kinds of questions because most of our patients are older.

Dr. Mehta. They have all the comorbidities.

Dr. Chauncey. We have what we think is an optimal regimen for an optimal patient, and then we have what we often see in the clinic. I’m not sure of the quantitative VA demographics, but if you look at the U.S. myeloma population, the median age is 70 years. While a triplet like

RVd or a carfilzomib-based triplet is probably optimal based on depth of response and the theoretical aspect of suppression of all subclones, it’s not really an accessible regimen for many patients that I see in clinic who are not transplant eligible.

For the nontransplant patients and more frail patients, the doublets or the cyclophosphamide/bortezomib/dexamethasone are reasonable options. I know there are proponents saying that everybody should get RVd or dose-attenuated RVd; I don’t think that’s practical for many of the patients that we see in our clinics.

Dr. Mehta. Why is it not practical in most of your patients? Because they have to come once a week to the clinic?

Dr. Chauncey. That’s part of it, but I find that it’s often too intense with excessive toxicity. The patients are older with comorbidities and they have more limited physiologic reserve. Part of it is coming to clinic, and that’s where all oral regimens such as Rd are useful. I don’t know that if you have an older patient and you see a good response that you’re tracking in terms of their Mspike (monoclonal protein) and their CRAB criteria, that everybody requires the aggressive approach of RVd or a similar triplet with a proteasome inhibitor, an IMiD [immunomodulator drug], and a steroid as induction therapy.

This is true even for some of the older patients who come to autologous transplantation. The data we talk about are in a younger group of patients who can tolerate the full dose of those regimens. The all-oral regimens are attractive, but it’s also quite a financial burden, maybe not to an individual patient, but certainly to the whole health care system. I’m not sure if there is a depth or durability of response advantage for the oral proteasome inhibitor over those available as IV or subcutaneous dosing.

Pricing

Dr. Ascensão. It’s interesting you bring that up because at the Washington DC VAMC, ixazomib may be priced similarly to bortezomib.

Dr. Chauncey. Well that would be very good and very interesting. It’s possible the federal pricing would make it a lot more attractive. It’s not the case outside of the VA, but there the cost burden for oral medication is often shifted to the patient.

Dr. Cosgriff. The price of carfilzomib is about $7,000 to $9,000 per month or per cycle. When we priced ixazomib here in Portland, it actually was more expensive than bortezomib, but it was cheaper than carfilzomib.

Dr. Mehta. If we can do a drug company-sponsored study, the ixazomib people would surely be interested in its usefulness as a triplet in VA patients. It also would be good for the VA patient because you don’t have to come once a week and it has much less neurotoxicity compared to the other proteasome inhibitors, which is a big problem.

Dr. Chauncey. That would be a great study to offer the right patient. I see a lot of myeloma patients in clinic that aren’t really eligible for transplantation. Many of those patients do well on doublet therapy, though they will often require dose adjustments, both down and up, as well as tracking disease status.

Dr. Cosgriff. In Portland, we’re using a lenalidomidebased regimen as a first-line therapy. We’re starting to see more and more individuals starting RVD upfront. There are some select individuals who have diabetic neuropathy or something like that, who may go on just

a lenalidomide plus dexamethasone, leaving out the bortezomib because of neuropathy issues.

Our second-line choice at this point in time has been carfilzomib, but with ixazomib being a cheaper option, we may actually consider switching over to that as a second-line choice. When you look at the clinical trials they cite in the product literature, the grade 1 neuropathy is about 18% with ixazomib and 14% with the placebo arm, so it does add some peripheral neuropathy. Maybe not as much as we would think.

While these oral agents and all-oral regimens are nice to have, we still bring in the patients for clinic and for monitoring of white blood count. It doesn’t necessarily decrease the burden of clinic visits. We still have to get lab draws. Yes, the patient is not sitting in a chair waiting for the bortezomib infusion to be mixed by the pharmacy, but we still have considerations for travel and those types of things.

We treat the entire state of Oregon and parts of southwest Washington. Fortunately, we have community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) and VAMCs in other areas of the state, and we also utilize places like Walla Walla and Spokane, Washington, where we can draw and check labs remotely, which decreases the travel burden, but it still is a burden to the patient to actually go in for lab tests. We’re not looking at ixazomib as a first line currently.

We’re going to wait for data to be published on ixazomib in the first line. In a couple of presentations, researchers have suggested that if you tease the data, ixazomib may be inferior to bortezomib in the first-line setting. It will be interesting to see what the data say for that as far as a first-line setting choice.

Dr. Chauncey. I second what Dr. Cosgriff said. You can’t just give patients 3 bottles of pills and say, “See you in 3 months.” Here in the Northwest we cover large rural areas, and there are many CBOCs whose labs feed directly into our CPRS (Computerized Patient Record System) so it’s very accessible and easy to follow patients that come in less frequently, but that doesn’t change the need for regular clinical follow-up. The other thing I’d say is the noncomparative data of carfilzomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone (CRD) is quite compelling in terms of depth and duration of response. We usually don’t want to accept convenience over efficacy. Whether that durability translates long term, we don’t really know, but I think right now, CRD is the best available regimen, again, with the caveat that it’s not really accessible to patients of all ages and performance status.

Dr. Ascensão. At the Washington DC VAMC in our first cycle it is day 1, 4, 8, and 11 with bortezomib, but after that we go pretty much to weekly bortezomib. We also tend to use what I would call lower dose 20 mg dexamethasone in patients over the age of 70 years. And we feel that it is a lot less toxic. We use subcutaneous bortezomib for pretty much everybody else.

Managing Adverse Effects

Dr. Chauncey. I think we’re all using subcutaneous bortezomib at this point. Dexamethasone doesn’t get a lot of independent attention, but there’s no question that, as Dr. Mehta mentioned, the older regimen that we used, the dose-dense dexamethasone of the VAD regimen, was

quite disabling. In addition to obvious hyperglycemia, there were psychiatric problems and, ultimately, profound steroid myopathy that seemed to affect patients in variable fashion. Different patients seem to be more or less susceptible, but after a couple of cycles, it starts to kick in and is progressive.

So we’ve since abandoned those massive doses. But when you look at the ECOG study (E4A03) that really defined the lower dose (40 mg weekly), there’s no question the higher dose was more toxic but also more effective in terms of disease response. While there are many older patients that I would start with a lower dose of dexamethasone, whether it’s with lenalidomide or bortezomib, I keep in mind there can be a steep dose response curve for dexamethasone. If you’re giving 20 mg and you’re not getting the response you need, then you increase the dose. There is definitely a dose response, but the higher doses are just not as well tolerated.

Dr. Cosgriff. I don’t know if other institutions are doing it, but instead of doing 40 mg as a single dose because of patient performance status, providers in Portland will prescribe 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16. They’ll break up that 40 mg dose and give it that way.

Dr. Chauncey. I don’t know if that strategy is biologically equivalent in terms of antimyeloma activity or less toxic in terms of myopathy. There’s almost always some disease marker to track, so that whether you’re using the serum free-light chain assay or serum protein electrophoresis, you can see if the strategy you’re using is working in real time.

Dr. Cosgriff. I’ve never known whether it’s been shown to be more efficacious or if it’s just a way of getting around some of the adverse effects. However, it does pose some alternate challenges. With higher doses of steroids, you’re looking at 2 days where the patient can become hyperglycemic, if not, a little bit longer.

The other thing with it is that adding on that extra day of dexamethasone can interfere with some other drugs and some other therapies. In individuals who have had a deep vein thrombosis for whatever reason and they’re on warfarin, now we have an agent that really screws up our warfarin monitoring. We would have to consider switching them to another agent.

Thrombosis

Dr. Mehta. It’s also prothrombotic.

Dr. Chauncey. If you actually ask the patient, independent of the hyperglycemia, independent of the myopathy, independent of psychosis, but just quality of life, they’ll typically tell you that the on-and-off of steroids is the worst part of the regimen. It’s often the roller coaster ride of short-term hypomania followed by dysphoria.

Dr. Mehta. And the lack of sleep. They describe it as being out of their skin.

Dr. Chauncey. They are. And as soon as they stop, often there is a depression.

Dr. Mehta. It is very, very difficult. And some actually develop psychosis.

Dr. Ascensão. We all use some form of acyclovir or its derivative for the prevention of shingles in patients exposed to the proteasome inhibitors. We use aspirin, usually low dose (81 mg), for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. But is anybody using other anticoagulants or putting everybody prophylactically on proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) or just seeing how people do first and then adjusting?

Dr. Chauncey. I typically use conventional dose aspirin, and if there’s breakthrough thrombosis, the first response should be that it is not the best regimen for this patient. Sometimes you have to go back to it, and if someone’s an anticoagulation candidate, then full anticoagulation is

needed if that’s the best regimen. Usually if there’s a breakthrough thrombosis, it is a deal breaker, and you’re ready to move on to a nonthrombogenic regimen.

There has been an observation (there is some biological basis to back this up) that if you give bortezomib with an IMiD, the regimen became less thrombogenic than with the IMiD and dexamethasone alone.

Dr. Ascensão. On aspirin, even if they’re on an IMiD plus a proteasome inhibitor, I just don’t know that the data are good enough for us to avoid it at this point in time. And I don’t necessarily put people on a PPI unless they’ve got added gastrointestinal problems and unless they have associated heartburn or dyspepsia symptoms.

Dr. Mehta. I use low-dose aspirin in every patient. And if they breakthrough, they go on full anticoagulation usually with a new oral anticoagulant. I use PPIs only if needed, although most of them do need it, and, of course, bisphosphonates so the bone protective aspect.

Click to read the digital edition.

Consensus Statement Supporting the Recommendation for Single-Fraction Palliative Radiotherapy for Uncomplicated, Painful Bone Metastases

The authors would like to acknowledge Tony Quang, MD, JD, for the advice given on this project.

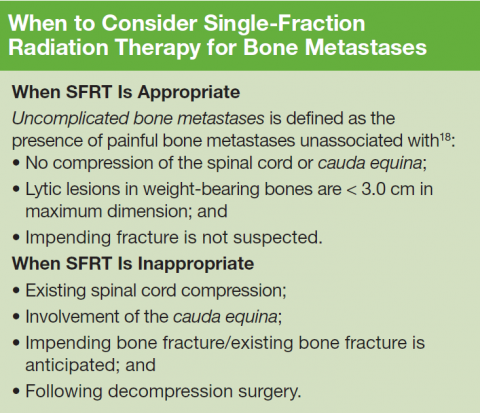

Palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases is typically delivered either as a short course of 1 to 5 fractions or protracted over longer courses of up to 20 treatments. These longer courses can be burdensome and discourage its utilization, despite a 50% to 80% likelihood of meaningful pain relief from only a single fraction of radiation therapy. Meanwhile, there are multiple randomized studies that have demonstrated that shorter course(s) are equivalent for pain control.

Although the VHA currently has 143 medical facilities that have cancer diagnostic and treatment capabilities, only 40 have radiation oncology services on-site.1 Thus, access to palliative radiotherapy may be limited for veterans who do not live close by, and many may seek care outside the VHA. At VHA radiation oncology centers, single-fraction radiation therapy (SFRT) is routinely offered by the majority of radiation oncologists.2,3 However, the longer course is commonly preferred outside the VA, and a recent SEER-Medicare analysis of more than 3,000 patients demonstrated that the majority of patients treated outside the VA actually receive more than 10 treatments.4 For this reason, the VA National Palliative Radiotherapy Task Force prepared this document to provide guidance for clinicians within and outside the VA to increase awareness of the appropriateness, effectiveness, and convenience of SFRT as opposed to longer courses of treatment that increase the burden of care at the end of life and often are unnecessary.

Veterans, Cancer, and Metastases