User login

CAR T-cell therapy demonstrates efficacy in mice with MM

WASHINGTON, DC—A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is active against multiple myeloma (MM), according to preclinical research.

The therapy, known as P-BCMA-101, demonstrated persistent anti-tumor activity in a mouse model of MM.

Treatment with P-BCMA-101 eliminated tumors after relapse and prolonged survival in the mice, when compared to other CAR-T cell therapies.

These results were presented in a poster at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract 3759).

The research was conducted by employees of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101, as well as others.

About P-BCMA-101

The researchers explained that P-BCMA-101 employs a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-specific Centyrin™ rather than a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) for antigen detection.

Centyrins™ are fully human and have similar binding affinities as scFvs. However, Centyrins are smaller, more thermostable, and predicted to be less immunogenic.

P-BCMA-101 is engineered using the PiggyBac™ DNA modification system. PiggyBac eliminates the need to use lentivirus or gamma-retrovirus as a gene delivery mechanism, resulting in improved manufacturing and cost savings.

In addition, the increased cargo capacity of PiggyBac allows for the incorporation of a safety switch and a selectable gene. The safety switch can be “flipped” to enable depletion in case adverse events occur. And the selectable gene allows for enrichment of CARTyrin+ cells using a non-genotoxic drug.

Findings

The researchers found that more than 70% of P-BCMA-101 cells possessed a stem cell memory phenotype, creating a significant population of self-renewing, multipotent progenitors capable of reconstituting the entire spectrum of memory and effector T-cell subsets required to prevent cancer relapse. Similar competitor products typically report 0% to 20% stem cell memory phenotype.

In addition, P-BCMA-101 was enriched with more than 95% of T cells successfully modified, which compares favorably to the roughly 30% to 50% commonly expected with clinical manufacture using lentivirus.

P-BCMA-101 did not exhibit effects of CAR-mediated tonic signaling, a common cause of T-cell exhaustion that leads to poor durability. Tonic signaling is caused by oligomerization of unstable binding domains commonly seen with traditional scFv CARs.

The researchers tested P-BCMA-101 in NSG mice bearing luciferase+ MM.1S cells. The mice received a single administration of either 4 x 106 or 12 x 106 P-BCMA-101 cells.

P-BCMA-101 treatment reduced tumor burden to the limit of detection within 7 days. Conversely, all untreated control mice succumbed to MM within 4 weeks.

P-BCMA-101 expanded and persisted in the treated mice, eliminated tumors following relapse, and prolonged survival.

Most treated mice survived 110 days, and none of them died from tumor burden during the study. This compares favorably to lentivirus-based products that have shown roughly 50-day survival in the same model.

Based on these results, Poseida plans to initiate a phase 1 trial of P-BCMA-101 in patients with relapsed or refractory MM. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is active against multiple myeloma (MM), according to preclinical research.

The therapy, known as P-BCMA-101, demonstrated persistent anti-tumor activity in a mouse model of MM.

Treatment with P-BCMA-101 eliminated tumors after relapse and prolonged survival in the mice, when compared to other CAR-T cell therapies.

These results were presented in a poster at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract 3759).

The research was conducted by employees of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101, as well as others.

About P-BCMA-101

The researchers explained that P-BCMA-101 employs a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-specific Centyrin™ rather than a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) for antigen detection.

Centyrins™ are fully human and have similar binding affinities as scFvs. However, Centyrins are smaller, more thermostable, and predicted to be less immunogenic.

P-BCMA-101 is engineered using the PiggyBac™ DNA modification system. PiggyBac eliminates the need to use lentivirus or gamma-retrovirus as a gene delivery mechanism, resulting in improved manufacturing and cost savings.

In addition, the increased cargo capacity of PiggyBac allows for the incorporation of a safety switch and a selectable gene. The safety switch can be “flipped” to enable depletion in case adverse events occur. And the selectable gene allows for enrichment of CARTyrin+ cells using a non-genotoxic drug.

Findings

The researchers found that more than 70% of P-BCMA-101 cells possessed a stem cell memory phenotype, creating a significant population of self-renewing, multipotent progenitors capable of reconstituting the entire spectrum of memory and effector T-cell subsets required to prevent cancer relapse. Similar competitor products typically report 0% to 20% stem cell memory phenotype.

In addition, P-BCMA-101 was enriched with more than 95% of T cells successfully modified, which compares favorably to the roughly 30% to 50% commonly expected with clinical manufacture using lentivirus.

P-BCMA-101 did not exhibit effects of CAR-mediated tonic signaling, a common cause of T-cell exhaustion that leads to poor durability. Tonic signaling is caused by oligomerization of unstable binding domains commonly seen with traditional scFv CARs.

The researchers tested P-BCMA-101 in NSG mice bearing luciferase+ MM.1S cells. The mice received a single administration of either 4 x 106 or 12 x 106 P-BCMA-101 cells.

P-BCMA-101 treatment reduced tumor burden to the limit of detection within 7 days. Conversely, all untreated control mice succumbed to MM within 4 weeks.

P-BCMA-101 expanded and persisted in the treated mice, eliminated tumors following relapse, and prolonged survival.

Most treated mice survived 110 days, and none of them died from tumor burden during the study. This compares favorably to lentivirus-based products that have shown roughly 50-day survival in the same model.

Based on these results, Poseida plans to initiate a phase 1 trial of P-BCMA-101 in patients with relapsed or refractory MM. ![]()

WASHINGTON, DC—A chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is active against multiple myeloma (MM), according to preclinical research.

The therapy, known as P-BCMA-101, demonstrated persistent anti-tumor activity in a mouse model of MM.

Treatment with P-BCMA-101 eliminated tumors after relapse and prolonged survival in the mice, when compared to other CAR-T cell therapies.

These results were presented in a poster at the AACR Annual Meeting 2017 (abstract 3759).

The research was conducted by employees of Poseida Therapeutics Inc., the company developing P-BCMA-101, as well as others.

About P-BCMA-101

The researchers explained that P-BCMA-101 employs a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-specific Centyrin™ rather than a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) for antigen detection.

Centyrins™ are fully human and have similar binding affinities as scFvs. However, Centyrins are smaller, more thermostable, and predicted to be less immunogenic.

P-BCMA-101 is engineered using the PiggyBac™ DNA modification system. PiggyBac eliminates the need to use lentivirus or gamma-retrovirus as a gene delivery mechanism, resulting in improved manufacturing and cost savings.

In addition, the increased cargo capacity of PiggyBac allows for the incorporation of a safety switch and a selectable gene. The safety switch can be “flipped” to enable depletion in case adverse events occur. And the selectable gene allows for enrichment of CARTyrin+ cells using a non-genotoxic drug.

Findings

The researchers found that more than 70% of P-BCMA-101 cells possessed a stem cell memory phenotype, creating a significant population of self-renewing, multipotent progenitors capable of reconstituting the entire spectrum of memory and effector T-cell subsets required to prevent cancer relapse. Similar competitor products typically report 0% to 20% stem cell memory phenotype.

In addition, P-BCMA-101 was enriched with more than 95% of T cells successfully modified, which compares favorably to the roughly 30% to 50% commonly expected with clinical manufacture using lentivirus.

P-BCMA-101 did not exhibit effects of CAR-mediated tonic signaling, a common cause of T-cell exhaustion that leads to poor durability. Tonic signaling is caused by oligomerization of unstable binding domains commonly seen with traditional scFv CARs.

The researchers tested P-BCMA-101 in NSG mice bearing luciferase+ MM.1S cells. The mice received a single administration of either 4 x 106 or 12 x 106 P-BCMA-101 cells.

P-BCMA-101 treatment reduced tumor burden to the limit of detection within 7 days. Conversely, all untreated control mice succumbed to MM within 4 weeks.

P-BCMA-101 expanded and persisted in the treated mice, eliminated tumors following relapse, and prolonged survival.

Most treated mice survived 110 days, and none of them died from tumor burden during the study. This compares favorably to lentivirus-based products that have shown roughly 50-day survival in the same model.

Based on these results, Poseida plans to initiate a phase 1 trial of P-BCMA-101 in patients with relapsed or refractory MM. ![]()

Drug granted orphan designation for MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for tasquinimod as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Tasquinimod is an immunomodulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic compound being developed by Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod works by inhibiting the function of S100A9, a pro-inflammatory protein that is elevated in MM and other malignancies.

S100A9 is believed to aid cancer development by recruiting and activating immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Active Biotech AB says that, by targeting the S100A9 pathway, tasquinimod interferes with the accumulation and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which decreases immune suppression and angiogenesis.

Tasquinimod also inhibits the hypoxic response in the tumor by binding to HDAC4, according to Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod has produced “robust results” in animal models of MM, and research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 supports this statement.

Investigators found that tasquinimod reduced tumor growth and improved survival in mouse models of MM. And these effects were associated with reduced angiogenesis in the bone marrow.

Tasquinimod was previously under development as a treatment for prostate cancer, but research suggested the drug did not have a favorable risk-benefit ratio in this patient population.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs and biologics intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent rare diseases/disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides companies with certain incentives to develop products for rare diseases. This includes a 50% tax break on research and development, a fee waiver, access to federal grants, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for tasquinimod as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Tasquinimod is an immunomodulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic compound being developed by Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod works by inhibiting the function of S100A9, a pro-inflammatory protein that is elevated in MM and other malignancies.

S100A9 is believed to aid cancer development by recruiting and activating immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Active Biotech AB says that, by targeting the S100A9 pathway, tasquinimod interferes with the accumulation and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which decreases immune suppression and angiogenesis.

Tasquinimod also inhibits the hypoxic response in the tumor by binding to HDAC4, according to Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod has produced “robust results” in animal models of MM, and research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 supports this statement.

Investigators found that tasquinimod reduced tumor growth and improved survival in mouse models of MM. And these effects were associated with reduced angiogenesis in the bone marrow.

Tasquinimod was previously under development as a treatment for prostate cancer, but research suggested the drug did not have a favorable risk-benefit ratio in this patient population.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs and biologics intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent rare diseases/disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides companies with certain incentives to develop products for rare diseases. This includes a 50% tax break on research and development, a fee waiver, access to federal grants, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for tasquinimod as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Tasquinimod is an immunomodulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic compound being developed by Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod works by inhibiting the function of S100A9, a pro-inflammatory protein that is elevated in MM and other malignancies.

S100A9 is believed to aid cancer development by recruiting and activating immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Active Biotech AB says that, by targeting the S100A9 pathway, tasquinimod interferes with the accumulation and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which decreases immune suppression and angiogenesis.

Tasquinimod also inhibits the hypoxic response in the tumor by binding to HDAC4, according to Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod has produced “robust results” in animal models of MM, and research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 supports this statement.

Investigators found that tasquinimod reduced tumor growth and improved survival in mouse models of MM. And these effects were associated with reduced angiogenesis in the bone marrow.

Tasquinimod was previously under development as a treatment for prostate cancer, but research suggested the drug did not have a favorable risk-benefit ratio in this patient population.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs and biologics intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent rare diseases/disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides companies with certain incentives to develop products for rare diseases. This includes a 50% tax break on research and development, a fee waiver, access to federal grants, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

Multiple Myeloma: Updates on Diagnosis and Management

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disease that is primarily treated by hematologists; however, it is important for primary care providers (PCPs) to be aware of the presentation and diagnosis of this disease. Multiple myeloma often is seen in the veteran population, and VA providers should be familiar with its diagnosis and treatment so that an appropriate referral can be made. Often, the initial signs and symptoms of the disease are subtle and require an astute eye by the PCP to diagnose and initiate a workup.

Once a veteran has an established diagnosis of MM or one of its precursor syndromes, the PCP will invariably be alerted to an adverse event (AE) of treatment or complication of the disease and should be aware of such complications to assist in management or referral. Patients with MM may achieve long-term remission; therefore, it is likely that the PCP will see an evolution in their treatment and care. Last, PCPs and patients often have a close relationship, and patients expect the PCP to understand their diagnosis and treatment plan.

Presentation

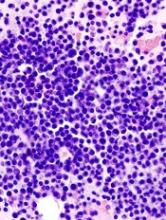

Multiple myeloma is a disease in which a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells produces a monoclonal immunoglobulin. It is almost invariably preceded by premalignant stages of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering MM (SMM), although not all cases of MGUS will eventually progress to MM.1 Common signs and symptoms include anemia, bone pain or lytic lesions on X-ray, kidney injury, fatigue, hypercalcemia, and weight loss.2 Anemia is usually a normocytic, normochromic anemia and can be due to involvement of the bone marrow, secondary to renal disease, or it may be dilutional, related to a high monoclonal protein (M protein) level.

There are several identifiable causes for renal disease in patients with MM, including light chain cast nephropathy, hypercalcemia, light chain amyloidosis, and light chain deposition disease. Without intervention, progressive renal damage may occur.3

Diagnosis

All patients with a suspected diagnosis of MM should undergo a basic workup, including complete blood count; peripheral blood smear; complete chemistry panel, including calcium and albumin; serum free light chain analysis (FLC); serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation; urinalysis; 24-hour urine collection for electrophoresis (UPEP) and immunofixation; serum B2-microglobulin; and lactate dehydrogenase.4 A FLC analysis is particularly useful for the diagnosis and monitoring of MM, when only small amounts of M protein are secreted into the serum/urine or for nonsecretory myeloma, as well as for light-chainonly myeloma.5

A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate should be performed in the diagnosis of MM to evaluate the bone marrow involvement and genetic abnormality of myeloma cells with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and cytogenetics, both of which are very important in risk stratification and for treatment planning. A skeletal survey is also typically performed to look for bone lesions.4 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be useful to evaluate for possible soft tissue lesions when a bone survey is negative, or to evaluate for spinal cord compression.5 Additionally, an MRI should be performed in patients with SMM at the initial assessment, because focal lesions in the setting of SMM are associated with an increased risk to progression.6 Since plain radiographs are usually abnormal only after ≥ 30% of the bone is destroyed, an MRI offers a more sensitive image.

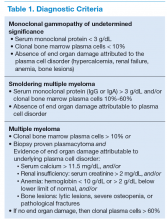

Two MM precursor syndromes are worth noting: MGUS and SMM. In evaluating a patient for possible MM, it is important to differentiate between MGUS, asymptomatic SMM, and MM that requires treatment.4 Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is diagnosed when a patient has a serum M protein that is < 3 g/dL, clonal bone marrow plasma cells < 10%, and no identifiable end organ damage.5 Smoldering MM is diagnosed when either the serum M protein is > 3 g/dL or bone marrow clonal plasma cells are > 10% in the absence of end organ damage.

Symptomatic MM is characterized by > 10% clonal bone marrow involvement with end organ damage that includes hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, or bone lesions. The diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1. The International Myeloma Working Group produced updated guidelines in 2014, which now include patients with > 60% bone marrow involvement of plasma cells, serum FLC ratio of > 100, and > 1 focal lesions on an MRI study as symptomatic MM.5,6

Most patients with MM will have a M protein produced by the malignant plasma cells detected on an SPEP or UPEP. The majority of immunoglobulins were IgG and IgA, whereas IgD and IgM were much less common.2 A minority of patients will not have a detectable M protein on SPEP or UPEP. Some patients will produce only light chains and are designated as light-chain-only myeloma. For these patients, the FLC assay is useful for diagnosis and disease monitoring. Patients who have an absence of M protein on SPEP/UPEP and normal FLC assay ratios are considered to have nonsecretory myeloma.7

Staging and Risk Stratification

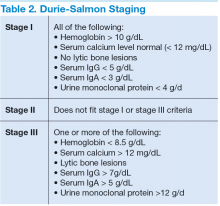

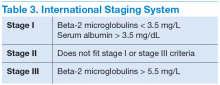

Two staging systems are used to evaluate a patient’s prognosis: the Durie-Salmon staging system, which is based on tumor burden (Table 2); and the International Staging System (ISS), which uses a combination of serum beta 2 microglobulin (B2M) and serum albumin levels to produce a powerful and reproducible 3-stage classification and is more commonly used by hematologists due to its simplicity to use and reliable reproducibility (Table 3).

In the Durie-Salmon staging system, patients with stage I disease have a lower tumor burden, defined as hemoglobin > 10 g/dL, normal calcium level, no evidence of lytic bone lesions, and low amounts of protein produced (IgG < 5 g/dL; IgA < 3 g/dL; urine protein < 4 g/d). Patients are classified as stage III if they have any of the following: hemoglobin < 8.5 g/dL, hypercalcemia with level > 12 mg/dL, bony lytic lesions, or high amounts of protein produced (IgG > 7 g/dL; IgA > 5 g/dL; or urine protein > 12 g/d). Patients with stage II disease do not fall into either of these categories. Stage III disease can be further differentiated into stage IIIA or stage IIIB disease if renal involvement is present.8

In the ISS system, patients with stage I disease have B2M levels that are < 3.5 mg/dL and albumin levels > 3.5 g/dL and have a median overall survival (OS) of 62 months. In this classification, stage III patients have B2M levels that are > 5.5 mg/dL and median OS was 29 months. Stage II patients do not meet either of these criteria and OS was 44 months.9 In a study by Mayo Clinic, OS has improved over the past decade, with OS for ISS stage III patients increasing to 4.2 years. Overall survival for both ISS stage I and stage III disease seems to have increased as well, although the end point has not been reached.10

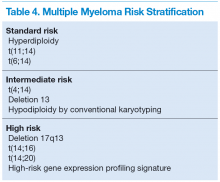

All myeloma patients are risk stratified at initial diagnosis based on their cytogenetic abnormalities identified mainly by FISH studies and conventional cytogenetics, which can serve as an alternative if FISH is unavailable. Genetic abnormalities of MM are the major predictor for the outcome and will affect treatment choice. Three risk groups have been identified: high-risk, intermediate-risk, and standard-risk MM (Table 4).11

Management of MGUS and SMM

Patients with MGUS progress to malignant conditions at a rate of 1% per year.12 Those individuals who are diagnosed with MGUS or SMM typically do not require therapy. According to the International Myeloma Working Group guidelines, patients should be monitored based on risk stratification. Those with low-risk MGUS (IgG M protein < 1.5 g/dL and no abnormal FLC ratio) can be monitored every 6 months for 2 to

3 years. Those who are intermediate to high risk need a baseline bone marrow biopsy in addition to skeletal survey and should check urine and serum levels for protein every 6 months for the first year and then annually thereafter.

Patients with SMM are at an increased risk of progression to symptomatic MM compared with patients with MGUS (10% per year for the first 5 years, 3% per year for the next 5 years).13 Therefore, experts recommend physician visits and laboratory testing for M proteins every 2 to 3 months for the first year and then an evaluation every 6 to 12 months if the patient remains clinically stable.14 Additionally, there are new

data to suggest that early therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for SMM can prolong time to disease progression as well as increase OS in individuals with SMM at high risk for progression.15

Patients With MM

All patients with a diagnosis of MM require immediate treatment. Initial choice of therapy is driven by whether a patient is eligible for an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), because certain agents, such as alkylating agents, should typically be avoided in those who are transplant eligible. Initial therapy for patients with MM is also based on genetic risk stratification of the disease. Patients with high-risk disease require a complete response (CR) treatment for long-term OS and thus benefit from an aggressive treatment strategy. Standard-risk patients have similar OS regardless of whether or not CR is achieved and thus can either be treated with an aggressive approach or a sequential therapy approach.16

Transplant-Eligible Patients

All patients should be evaluated for transplant eligibility, because it results in superior progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with MM compared with standard chemotherapy. Transplant eligibility requirements differ, depending on the transplant center. There is no strict age limit in the U.S. for determining transplant eligibility. Physiological age and factors such as functional status and liver function are often considered before making a transplant decision.

For VA patients, transplants are generally considered in those aged < 65 years, and patients are referred to 1 of 3 transplant centers: VA Puget Sound Healthcare System in Seattle, Washington; Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville; or South Texas Veterans Healthcare System in San Antonio.17 All patients who are transplant eligible should receive induction therapy for 2 to 4 months before stem cell collection. This is to reduce tumor burden, for symptomatic management, as well as to lessen end organ damage. After stem cell collection, patients undergo either upfront ASCT or resume induction therapy and undergo a transplant after first relapse.

Bortezomib Regimens

Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and has been used as upfront chemotherapy for transplant-eligible patients, traditionally to avoid alkylating agents that could affect stem cell harvest. It is highly efficacious in the treatment of patients with MM. Two- or 3-drug regimens have been used. Common regimens include bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone; bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone (VTD); bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone (VRD); bortezomib, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; as well as bortezomib, dexamethasone.18 Dexamethasone is less expensive than VTD or VRD, well tolerated, and efficacious. It is often used upfront for newly diagnosed MM.19 Threedrug regimens have shown to be more efficacious than 2-drug regimens in clinical trials (Table 5).20

Of note, bortezomib is not cleared through the kidney, which makes it an ideal choice for patients with renal function impairment. A significant potential AE with bortezomib is the onset of peripheral neuropathy. Bortezomib can be administered once or twice weekly. Twice-weekly administration of bortezomib is preferred when rapid results are needed, such as light chain cast nephropathy causing acute renal failure.21

Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone

Lenalidomide is a second-generation immunomodulating agent that is being increasingly used as initial therapy for MM. There is currently no data showing superiority of bortezomib-based regimens to lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in reference to OS. Bortezomib-based regimens seem to overcome the poor prognosis associated with t(4;14) translocation and thus should be considered in choosing initial chemotherapy treatment.22

Lenalidomide can affect stem cell collection; therefore, it is important to collect stem cells in transplanteligible patients who are aged < 65 years or for those who have received more than 4 cycles of treatment with this regimen.23,24 A major AE to lenalidomidecontaining regimens is the increased risk of thrombosis. All patients on lenalidomide require treatment with aspirin at a minimum; however, those at higher risk for thrombosis may require low-molecular weight heparin or warfarin.25

Carfilzomib Plus Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone

Carfilzomib is a recently approved PI that has shown promise in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone as initial therapy for MM. Several phase 2 trials have reported favorable results with carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM.26,27 More studies are needed to establish efficacy and safety before this regimen is routinely used as upfront therapy.11

Thalidomide Plus Dexamethasone

Although there are no randomized controlled trials comparing lenalidomide plus dexamethasone with thalidomide plus dexamethasone, these regimens have been compared in retrospective studies. In these studies, lenalidomide plus dexamethasone showed both a higher response rate as well as an increased PFS and OS compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone. Additionally, lenalidomide’s AE profile was more favorable than that of thalidomide. In light of this, lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is preferred to thalidomide plus dexamethasone in the management of MM, although the latter can be considered when lenalidomide is not available or when a patient does not tolerate lenalidomide.28

VDT-PACE

A multidrug combination that should be considered in select populations is the VDT-PACE regimen, which includes bortezomib, dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide. This regimen can be considered in those patients who have aggressive disease, such as those with plasma cell leukemia or with multiple extramedullary plasmacytomas.11

Autologous Stem Cell Transplant

Previous data suggest that ASCT improves OS in MM by 12 months.29 A more recent open-label, randomized trial comparing melphalan and ASCT to melphalanprednisone-lenalidomide showed significant prolonged PFS and OS among patients with MM.30 Although the role of ASCT may change as new drugs are integrated into initial therapy of MM, ASCT is still the preferred approach in transplant-eligible patients. As such, all patients who are eligible should be considered to receive a transplant.

There remains debate about whether ASCT should be performed early, after 2 to 4 cycles of induction therapy, or late after first relapse. Several randomized trials failed to show a difference in survival for early vs delayed ASCT approach.31 Generally, transplant can be delayed for patients with standard-risk MM who have responded well to therapy.11 Those patients who do not achieve a CR with their first ASCT may benefit from a second (tandem) ASCT.32 An allogeneic transplant is occasionally used in select populations and is the only potentially curative

therapy for these patients. However, its high mortality rate precludes its everyday use.

Transplant-Ineligible Patients

For patients with newly diagnosed MM who are ineligible for ASCT due to age or other comorbidities, chemotherapy is the only option. Many patients will benefit not only in survival, but also in quality of life. Immunomodulatory agents, such as lenalidomide and thalidomide, and PIs, such as bortezomib, are highly effective and well tolerated. There has been a general shift to using these agents upfront in transplant ineligible patients.

All previously mentioned regimens can also be used in transplant-ineligible patients. Although no longer the preferred treatment, melphalan can be considered in resource-poor settings.11 Patients who are not transplant eligible are treated for a fixed period of 9 to 18 months, although lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is often continued until relapse.11,33

Melphalan Plus Prednisone Plus Bortezomib

The addition of bortezomib to melphalan and prednisone results in improved OS compared with that of melphalan and dexamethasone alone.34 Peripheral neuropathy is a significant AE and can be minimized by giving bortezomib once weekly.

Melphalan Plus Prednisone Plus Thalidomide

Melphalan plus prednisone plus thalidomide has shown an OS benefit compared with that of melphalan and prednisone alone. The regimen has a high toxicity rate (> 50%) and a deep vein thrombosis rate of 20%, so patients undergoing treatment with this regimen require thromboprophylaxis.35,36

Melphalan Plus Prednisone

Although melphalan plus prednisone has fallen out of favor due to the existence of more efficacious regimens, it may be useful in an elderly patient population who lack access to newer agents, such as lenalidomide, thalidomide, and bortezomib.

Assessing Treatment Response

The International Myeloma Working Group has established criteria for assessing disease response. Patient’s response to therapy should be assessed with a FLC assay before each cycle with SPEP and UPEP and in those without measurable M protein levels. A bone marrow biopsy can be helpful in patients with immeasurable M protein levels and low FLC levels, as well as to establish that a CR is present.

A CR is defined as negative SPEP/UPEP, disappearance of soft tissue plamacytomas, and < 5% plasma cells in bone marrow. A very good partial response is defined as serum/urine M protein being present on immunofixation but not electrophoresis or reduction in serum M protein by 90% and urine M protein < 100 mg/d. For those without measurable M protein, a reduction in FLC ratio by 90% is required. A partial response is defined as > 50% reduction of the serum monoclonal protein and/or < 200 mg urinary M protein per 24 hours or > 90% reduction in urinary M protein. For those without M protein present, they should have > 50% decrease in FLC ratio.5

Maintenance Therapy

There is currently considerable debate about whether patients should be treated with maintenance therapy following induction chemotherapy or transplant. In patients treated with transplant, there have been several studies to investigate the use of maintenance therapy. Lenalidomide

has been evaluated for maintenance therapy following stem cell transplant and has shown superior PFS with dexamethasone as post-ASCT maintenance; however, this is at the cost of increased secondary cancers.37

Thalidomide has also been studied as maintenance therapy and seems to have a modest improvement in PFS and OS but at the cost of increased toxicities, such as neuropathy and thromboembolism.38,39 Still other studies compared bortezomib maintenance with thalidomide

maintenance in posttransplant patients and was able to show improved OS. As a result, certain patients with intermediate- or high-risk disease may be eligible for bortezomib for maintenance following transplant.11 For transplant-ineligible patients, there is no clear role for maintenance therapy.

Refractory/Relapsed Disease Treatments

Nearly all patients with MM will relapse at some point in their disease. Relapse is usually detected during surveillance and should be considered when the patient develops new bone lesions, hypercalcemia, anemia, renal failure, or rapid rise in M protein levels. For these patients, treatment options that should be considered are an ASCT if one has not been done before; an additional ASCT, providing the patient has not relapsed within 12 months of the first; repeating the initial chemotherapy regimen; or choosing an alternative chemotherapy regimen.5,11 For those who are not transplant candidates, chemotherapy remains the only option.

Single-agent bortezomib has shown promise in relapsed/refractory MM, with more than one-third of patients having partial response or CR.40,41 A study of bortezomib combined with liposomal doxorubicin has also shown a modest improvement in time to progression compared with single-agent bortezomib and can also be considered for relapsed/refractory disease.42 An additional option is an immunonomodulatory drug, such as lenalidomide or thalidomide. Unfortunately, poorer outcomes have been reported for patients who are refractory to both lenalidomide or bortezomib.43

Pomalidomide is a thalidomide analog and has activity in MM that is relapsed or refractory with acceptable response rates when used with dexamethasone.44 Carfilzomib is a PI approved for treatment of relapsed or refractory MM in patients who have failed lenalidomide and bortezomib.45 The FDA recently approved panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for patients with MM who have failed 2 prior therapies, and it has shown improved PFS.46 Patients should be treated in a clinical trial whenever possible, and emerging new options include second generation PIs, such as ixazomib, other histone deacetlyase inhibitors, AKT/P13K/mTOR inhibitors, heat-shock-protein inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies.

Conclusions

Despite significant advances in the management of MM, the disease remains incurable. Virtually all patients will develop relapsed disease, although strides in the field have provided opportunities for longer term remissions. There are a multitude of strategies that are under investigation, and further studies are needed to establish their role in the treatment of patients with MM.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Landgren O, Kyle R, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5412-5417.

2. Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21-33.

3. Hutchison CA, Batuman V, Behrens J, et al; International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. The pathogenesis and diagnosis of acute kidney injury in multiple myeloma. Nat Review Nephrol. 2011;8(1):43-51.

4. Dimopoulous M, Kyle R, Fermand JP, et al; International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Consensus recommendations for standard investigative workup: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 3. Blood. 2011;117(18):4701-4705.

5. Palumbo A, Rajkumar S, San Miguel JF, et al. International Melanoma Working Group consensus statement for the management, treatment, and supportive care of patients with myeloma not eligible for standard autologous stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):587-600.

6. Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538-e548.

7. Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Terpo E. Non-secretory myeloma: one, two, or more entities? Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(9):930-932.

8. Durie BG, Salmon SE. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma. Correlation of measured myeloma cell mass with presenting clinical features, response to treatment, and survival. Cancer. 1975;36(3):842-854.

9. Griepp P, San Miguel J, Durie BG, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3412-3420.

10. Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014; 28(5):1122-1128.

11. Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(10):999-1009.

12. Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):564-569.

13. Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2582-2590.

14. Landgren O. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma: biological insights and early treatment strategies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013(1):478-487.

15. Mateos MV, Hernández MT, Giraldo P, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):438-447.

16. Haessler K, Shaughnessy JD Jr, Zhan F, et al. Benefit of complete response in multiple myeloma limited to high-risk subgroup identified by gene expression profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):7073-7079.

17. Xiang Z, Mehta P. Management of multiple myeloma and its precursor syndromes. Fed Pract. 2014;31(suppl 3):6S-13S.

18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: multiple myeloma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/myeloma.pdf. Updated March 10, 2015. Accessed July 8, 2015.

19. Kumar S, Flinn I, Richardson P, et al. Randomized, multicenter, phase 2 study (EVOLUTION) of combinations of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclosphosphamide, and lenalidomide in previously untreated multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119(19):4375-4382.

20. Moreau P, Avet-Loiseau H, Facon T, et al. Bortezomib plus dexamethasone versus reduced-dose bortezomib, thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction treatment before autologous stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;118(22):5752-5758.

21. Moreau P, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomized, phase 3, noninferiority study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(5):431-440.

22. Pineda-Roman M, Zangari M, Haessler J, et al. Sustained complete remissions in multiple myeloma linked to bortezomib in total therapy 3: comparison with total therapy 2. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(6):624-634.

23. Kumar S, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, et al. Impact of lenalidomide therapy on stem cell mobilization and engraftment post-peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21(9):2035-2042.

24. Kumar S, Giralt S, Stadtmauer EA, et al; International Myeloma Working Group. Mobilization in myeloma revisited: IMWG consensus perspectives on stem cell collection following initial therapy with thalidomide-, lenalidomide-, or bortezomibcontaining regimens. Blood. 2009;114(9):1729-1735.

25. Larocca A, Cavallo F, Bringhen S, et al. Aspirin or enoxaparin thromboprophylaxis for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with lenalidomide. Blood. 2012;119(4):933-939.

26. Jakubowiak AJ, Dytfeld D, Griffith KA, et al. A phase 1/2 study of carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and low dose dexamethasone as a frontline treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120(9):1801-1809.

27. Korde N, Zingone A, Kwok M, et al. Phase II clinical and correlative study of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone followed by lenalidomide extended dosing (CRD-R) induces high rates of MRD negativity in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients [Abstract]. Blood. 2013;122(21):538.

28. Gay F, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone versus thalidomide plus dexamethasone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a comparative analysis of 411 patients. Blood. 2010;115(7):1343-1350.

29. Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppa AM, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma. Intergroupe Français du Myélome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(2):91-97.

30. Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(10):895-905.

31. Fermand JP, Ravaud P, Chevret S, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: up-front or rescue treatment? Results of a multicenter sequential randomized clinical trial. Blood. 1998;92(9):3131-3136.

32. Elice F, Raimondi R, Tosetto A, et al. Prolonged overall survival with second on-demand autologous stem cell transplant in multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2006;81(6):426-431.

33. Facon T, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, et al. Initial phase 3 results of the FIRST (frontline investigation of lenalidomide + dexamethasone versus standard thalidomide) trial (MM-020/IFM 07 01) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients (pts) ineligible for stem cell transplantation (SCT). Blood. 2013;122(21):2.

34. San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(9):906-917.

35. Facon T, Mary JY, Hulin C, et al; Intergroupe Français du Myélome. Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide versus melphalan and prednisone alone or reduced-intensity autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients with multiple myeloma (IFM 99-06): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9594):1209-1218.

36. Hulin C, Facon T, Rodon P, et al. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. IFM 01/01 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3664-3670.

37. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1782-1791.

38. Attal M., Harousseau JL, Leyvraz S, et al; Inter-Groupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM). Maintenance therapy with thalidomide improves survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(10):3289-3294.

39. Spencer A, Prince HM, Roberts AW, et al. Consolidation therapy with low-dose thalidomide and prednisolone prolongs the survival of multiple myeloma patients undergoing a single autologous stem-cell transplantation procedure. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1788-1793.

40. Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IG, van der Holt B, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2946-2955.

41. Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, et al; Assessment of Proteasome Inhibition for Extending Remissions (APEX) Investigators. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2487-2498.

42. Orlowski RZ, Nagler A, Sonneveld P, et al. Randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus bortezomib compared with bortezomib alone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: combination therapy improves time to progression. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(25):3892-3901.

43. Kumar SK, Lee JH, Lahuerta JJ, et al; International Myeloma Working Group. Risk of progression and survival in multiple myeloma relapsing after therapy with IMiDs and bortezomib: a multicenter international myeloma working group study. Leukemia. 2012;26(1):149-157.

44. Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Gertz MA, et al. Pomalidomide (CC4047) plus low-dose dexamethasone as therapy for relapsed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(30):5008-5014.

45. Siegel DS, Martin T, Wang M, et al. A phase 2 study of single agent carfilzomib (PX-171-003-A1) in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120(14):2817-2825.

46. San-Miguel JF, Hungria VT, Yoon SS, et al. Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):1195-1206.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disease that is primarily treated by hematologists; however, it is important for primary care providers (PCPs) to be aware of the presentation and diagnosis of this disease. Multiple myeloma often is seen in the veteran population, and VA providers should be familiar with its diagnosis and treatment so that an appropriate referral can be made. Often, the initial signs and symptoms of the disease are subtle and require an astute eye by the PCP to diagnose and initiate a workup.

Once a veteran has an established diagnosis of MM or one of its precursor syndromes, the PCP will invariably be alerted to an adverse event (AE) of treatment or complication of the disease and should be aware of such complications to assist in management or referral. Patients with MM may achieve long-term remission; therefore, it is likely that the PCP will see an evolution in their treatment and care. Last, PCPs and patients often have a close relationship, and patients expect the PCP to understand their diagnosis and treatment plan.

Presentation

Multiple myeloma is a disease in which a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells produces a monoclonal immunoglobulin. It is almost invariably preceded by premalignant stages of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering MM (SMM), although not all cases of MGUS will eventually progress to MM.1 Common signs and symptoms include anemia, bone pain or lytic lesions on X-ray, kidney injury, fatigue, hypercalcemia, and weight loss.2 Anemia is usually a normocytic, normochromic anemia and can be due to involvement of the bone marrow, secondary to renal disease, or it may be dilutional, related to a high monoclonal protein (M protein) level.

There are several identifiable causes for renal disease in patients with MM, including light chain cast nephropathy, hypercalcemia, light chain amyloidosis, and light chain deposition disease. Without intervention, progressive renal damage may occur.3

Diagnosis

All patients with a suspected diagnosis of MM should undergo a basic workup, including complete blood count; peripheral blood smear; complete chemistry panel, including calcium and albumin; serum free light chain analysis (FLC); serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation; urinalysis; 24-hour urine collection for electrophoresis (UPEP) and immunofixation; serum B2-microglobulin; and lactate dehydrogenase.4 A FLC analysis is particularly useful for the diagnosis and monitoring of MM, when only small amounts of M protein are secreted into the serum/urine or for nonsecretory myeloma, as well as for light-chainonly myeloma.5

A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate should be performed in the diagnosis of MM to evaluate the bone marrow involvement and genetic abnormality of myeloma cells with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and cytogenetics, both of which are very important in risk stratification and for treatment planning. A skeletal survey is also typically performed to look for bone lesions.4 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be useful to evaluate for possible soft tissue lesions when a bone survey is negative, or to evaluate for spinal cord compression.5 Additionally, an MRI should be performed in patients with SMM at the initial assessment, because focal lesions in the setting of SMM are associated with an increased risk to progression.6 Since plain radiographs are usually abnormal only after ≥ 30% of the bone is destroyed, an MRI offers a more sensitive image.

Two MM precursor syndromes are worth noting: MGUS and SMM. In evaluating a patient for possible MM, it is important to differentiate between MGUS, asymptomatic SMM, and MM that requires treatment.4 Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is diagnosed when a patient has a serum M protein that is < 3 g/dL, clonal bone marrow plasma cells < 10%, and no identifiable end organ damage.5 Smoldering MM is diagnosed when either the serum M protein is > 3 g/dL or bone marrow clonal plasma cells are > 10% in the absence of end organ damage.

Symptomatic MM is characterized by > 10% clonal bone marrow involvement with end organ damage that includes hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, or bone lesions. The diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1. The International Myeloma Working Group produced updated guidelines in 2014, which now include patients with > 60% bone marrow involvement of plasma cells, serum FLC ratio of > 100, and > 1 focal lesions on an MRI study as symptomatic MM.5,6

Most patients with MM will have a M protein produced by the malignant plasma cells detected on an SPEP or UPEP. The majority of immunoglobulins were IgG and IgA, whereas IgD and IgM were much less common.2 A minority of patients will not have a detectable M protein on SPEP or UPEP. Some patients will produce only light chains and are designated as light-chain-only myeloma. For these patients, the FLC assay is useful for diagnosis and disease monitoring. Patients who have an absence of M protein on SPEP/UPEP and normal FLC assay ratios are considered to have nonsecretory myeloma.7

Staging and Risk Stratification

Two staging systems are used to evaluate a patient’s prognosis: the Durie-Salmon staging system, which is based on tumor burden (Table 2); and the International Staging System (ISS), which uses a combination of serum beta 2 microglobulin (B2M) and serum albumin levels to produce a powerful and reproducible 3-stage classification and is more commonly used by hematologists due to its simplicity to use and reliable reproducibility (Table 3).

In the Durie-Salmon staging system, patients with stage I disease have a lower tumor burden, defined as hemoglobin > 10 g/dL, normal calcium level, no evidence of lytic bone lesions, and low amounts of protein produced (IgG < 5 g/dL; IgA < 3 g/dL; urine protein < 4 g/d). Patients are classified as stage III if they have any of the following: hemoglobin < 8.5 g/dL, hypercalcemia with level > 12 mg/dL, bony lytic lesions, or high amounts of protein produced (IgG > 7 g/dL; IgA > 5 g/dL; or urine protein > 12 g/d). Patients with stage II disease do not fall into either of these categories. Stage III disease can be further differentiated into stage IIIA or stage IIIB disease if renal involvement is present.8

In the ISS system, patients with stage I disease have B2M levels that are < 3.5 mg/dL and albumin levels > 3.5 g/dL and have a median overall survival (OS) of 62 months. In this classification, stage III patients have B2M levels that are > 5.5 mg/dL and median OS was 29 months. Stage II patients do not meet either of these criteria and OS was 44 months.9 In a study by Mayo Clinic, OS has improved over the past decade, with OS for ISS stage III patients increasing to 4.2 years. Overall survival for both ISS stage I and stage III disease seems to have increased as well, although the end point has not been reached.10

All myeloma patients are risk stratified at initial diagnosis based on their cytogenetic abnormalities identified mainly by FISH studies and conventional cytogenetics, which can serve as an alternative if FISH is unavailable. Genetic abnormalities of MM are the major predictor for the outcome and will affect treatment choice. Three risk groups have been identified: high-risk, intermediate-risk, and standard-risk MM (Table 4).11

Management of MGUS and SMM

Patients with MGUS progress to malignant conditions at a rate of 1% per year.12 Those individuals who are diagnosed with MGUS or SMM typically do not require therapy. According to the International Myeloma Working Group guidelines, patients should be monitored based on risk stratification. Those with low-risk MGUS (IgG M protein < 1.5 g/dL and no abnormal FLC ratio) can be monitored every 6 months for 2 to

3 years. Those who are intermediate to high risk need a baseline bone marrow biopsy in addition to skeletal survey and should check urine and serum levels for protein every 6 months for the first year and then annually thereafter.

Patients with SMM are at an increased risk of progression to symptomatic MM compared with patients with MGUS (10% per year for the first 5 years, 3% per year for the next 5 years).13 Therefore, experts recommend physician visits and laboratory testing for M proteins every 2 to 3 months for the first year and then an evaluation every 6 to 12 months if the patient remains clinically stable.14 Additionally, there are new

data to suggest that early therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for SMM can prolong time to disease progression as well as increase OS in individuals with SMM at high risk for progression.15

Patients With MM

All patients with a diagnosis of MM require immediate treatment. Initial choice of therapy is driven by whether a patient is eligible for an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), because certain agents, such as alkylating agents, should typically be avoided in those who are transplant eligible. Initial therapy for patients with MM is also based on genetic risk stratification of the disease. Patients with high-risk disease require a complete response (CR) treatment for long-term OS and thus benefit from an aggressive treatment strategy. Standard-risk patients have similar OS regardless of whether or not CR is achieved and thus can either be treated with an aggressive approach or a sequential therapy approach.16

Transplant-Eligible Patients

All patients should be evaluated for transplant eligibility, because it results in superior progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with MM compared with standard chemotherapy. Transplant eligibility requirements differ, depending on the transplant center. There is no strict age limit in the U.S. for determining transplant eligibility. Physiological age and factors such as functional status and liver function are often considered before making a transplant decision.

For VA patients, transplants are generally considered in those aged < 65 years, and patients are referred to 1 of 3 transplant centers: VA Puget Sound Healthcare System in Seattle, Washington; Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville; or South Texas Veterans Healthcare System in San Antonio.17 All patients who are transplant eligible should receive induction therapy for 2 to 4 months before stem cell collection. This is to reduce tumor burden, for symptomatic management, as well as to lessen end organ damage. After stem cell collection, patients undergo either upfront ASCT or resume induction therapy and undergo a transplant after first relapse.

Bortezomib Regimens

Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and has been used as upfront chemotherapy for transplant-eligible patients, traditionally to avoid alkylating agents that could affect stem cell harvest. It is highly efficacious in the treatment of patients with MM. Two- or 3-drug regimens have been used. Common regimens include bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone; bortezomib, thalidomide, dexamethasone (VTD); bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone (VRD); bortezomib, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; as well as bortezomib, dexamethasone.18 Dexamethasone is less expensive than VTD or VRD, well tolerated, and efficacious. It is often used upfront for newly diagnosed MM.19 Threedrug regimens have shown to be more efficacious than 2-drug regimens in clinical trials (Table 5).20

Of note, bortezomib is not cleared through the kidney, which makes it an ideal choice for patients with renal function impairment. A significant potential AE with bortezomib is the onset of peripheral neuropathy. Bortezomib can be administered once or twice weekly. Twice-weekly administration of bortezomib is preferred when rapid results are needed, such as light chain cast nephropathy causing acute renal failure.21

Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone

Lenalidomide is a second-generation immunomodulating agent that is being increasingly used as initial therapy for MM. There is currently no data showing superiority of bortezomib-based regimens to lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in reference to OS. Bortezomib-based regimens seem to overcome the poor prognosis associated with t(4;14) translocation and thus should be considered in choosing initial chemotherapy treatment.22

Lenalidomide can affect stem cell collection; therefore, it is important to collect stem cells in transplanteligible patients who are aged < 65 years or for those who have received more than 4 cycles of treatment with this regimen.23,24 A major AE to lenalidomidecontaining regimens is the increased risk of thrombosis. All patients on lenalidomide require treatment with aspirin at a minimum; however, those at higher risk for thrombosis may require low-molecular weight heparin or warfarin.25

Carfilzomib Plus Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone

Carfilzomib is a recently approved PI that has shown promise in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone as initial therapy for MM. Several phase 2 trials have reported favorable results with carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM.26,27 More studies are needed to establish efficacy and safety before this regimen is routinely used as upfront therapy.11

Thalidomide Plus Dexamethasone

Although there are no randomized controlled trials comparing lenalidomide plus dexamethasone with thalidomide plus dexamethasone, these regimens have been compared in retrospective studies. In these studies, lenalidomide plus dexamethasone showed both a higher response rate as well as an increased PFS and OS compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone. Additionally, lenalidomide’s AE profile was more favorable than that of thalidomide. In light of this, lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is preferred to thalidomide plus dexamethasone in the management of MM, although the latter can be considered when lenalidomide is not available or when a patient does not tolerate lenalidomide.28

VDT-PACE

A multidrug combination that should be considered in select populations is the VDT-PACE regimen, which includes bortezomib, dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide. This regimen can be considered in those patients who have aggressive disease, such as those with plasma cell leukemia or with multiple extramedullary plasmacytomas.11

Autologous Stem Cell Transplant

Previous data suggest that ASCT improves OS in MM by 12 months.29 A more recent open-label, randomized trial comparing melphalan and ASCT to melphalanprednisone-lenalidomide showed significant prolonged PFS and OS among patients with MM.30 Although the role of ASCT may change as new drugs are integrated into initial therapy of MM, ASCT is still the preferred approach in transplant-eligible patients. As such, all patients who are eligible should be considered to receive a transplant.

There remains debate about whether ASCT should be performed early, after 2 to 4 cycles of induction therapy, or late after first relapse. Several randomized trials failed to show a difference in survival for early vs delayed ASCT approach.31 Generally, transplant can be delayed for patients with standard-risk MM who have responded well to therapy.11 Those patients who do not achieve a CR with their first ASCT may benefit from a second (tandem) ASCT.32 An allogeneic transplant is occasionally used in select populations and is the only potentially curative

therapy for these patients. However, its high mortality rate precludes its everyday use.

Transplant-Ineligible Patients

For patients with newly diagnosed MM who are ineligible for ASCT due to age or other comorbidities, chemotherapy is the only option. Many patients will benefit not only in survival, but also in quality of life. Immunomodulatory agents, such as lenalidomide and thalidomide, and PIs, such as bortezomib, are highly effective and well tolerated. There has been a general shift to using these agents upfront in transplant ineligible patients.

All previously mentioned regimens can also be used in transplant-ineligible patients. Although no longer the preferred treatment, melphalan can be considered in resource-poor settings.11 Patients who are not transplant eligible are treated for a fixed period of 9 to 18 months, although lenalidomide plus dexamethasone is often continued until relapse.11,33

Melphalan Plus Prednisone Plus Bortezomib

The addition of bortezomib to melphalan and prednisone results in improved OS compared with that of melphalan and dexamethasone alone.34 Peripheral neuropathy is a significant AE and can be minimized by giving bortezomib once weekly.

Melphalan Plus Prednisone Plus Thalidomide

Melphalan plus prednisone plus thalidomide has shown an OS benefit compared with that of melphalan and prednisone alone. The regimen has a high toxicity rate (> 50%) and a deep vein thrombosis rate of 20%, so patients undergoing treatment with this regimen require thromboprophylaxis.35,36

Melphalan Plus Prednisone

Although melphalan plus prednisone has fallen out of favor due to the existence of more efficacious regimens, it may be useful in an elderly patient population who lack access to newer agents, such as lenalidomide, thalidomide, and bortezomib.

Assessing Treatment Response

The International Myeloma Working Group has established criteria for assessing disease response. Patient’s response to therapy should be assessed with a FLC assay before each cycle with SPEP and UPEP and in those without measurable M protein levels. A bone marrow biopsy can be helpful in patients with immeasurable M protein levels and low FLC levels, as well as to establish that a CR is present.

A CR is defined as negative SPEP/UPEP, disappearance of soft tissue plamacytomas, and < 5% plasma cells in bone marrow. A very good partial response is defined as serum/urine M protein being present on immunofixation but not electrophoresis or reduction in serum M protein by 90% and urine M protein < 100 mg/d. For those without measurable M protein, a reduction in FLC ratio by 90% is required. A partial response is defined as > 50% reduction of the serum monoclonal protein and/or < 200 mg urinary M protein per 24 hours or > 90% reduction in urinary M protein. For those without M protein present, they should have > 50% decrease in FLC ratio.5

Maintenance Therapy

There is currently considerable debate about whether patients should be treated with maintenance therapy following induction chemotherapy or transplant. In patients treated with transplant, there have been several studies to investigate the use of maintenance therapy. Lenalidomide

has been evaluated for maintenance therapy following stem cell transplant and has shown superior PFS with dexamethasone as post-ASCT maintenance; however, this is at the cost of increased secondary cancers.37

Thalidomide has also been studied as maintenance therapy and seems to have a modest improvement in PFS and OS but at the cost of increased toxicities, such as neuropathy and thromboembolism.38,39 Still other studies compared bortezomib maintenance with thalidomide

maintenance in posttransplant patients and was able to show improved OS. As a result, certain patients with intermediate- or high-risk disease may be eligible for bortezomib for maintenance following transplant.11 For transplant-ineligible patients, there is no clear role for maintenance therapy.

Refractory/Relapsed Disease Treatments

Nearly all patients with MM will relapse at some point in their disease. Relapse is usually detected during surveillance and should be considered when the patient develops new bone lesions, hypercalcemia, anemia, renal failure, or rapid rise in M protein levels. For these patients, treatment options that should be considered are an ASCT if one has not been done before; an additional ASCT, providing the patient has not relapsed within 12 months of the first; repeating the initial chemotherapy regimen; or choosing an alternative chemotherapy regimen.5,11 For those who are not transplant candidates, chemotherapy remains the only option.

Single-agent bortezomib has shown promise in relapsed/refractory MM, with more than one-third of patients having partial response or CR.40,41 A study of bortezomib combined with liposomal doxorubicin has also shown a modest improvement in time to progression compared with single-agent bortezomib and can also be considered for relapsed/refractory disease.42 An additional option is an immunonomodulatory drug, such as lenalidomide or thalidomide. Unfortunately, poorer outcomes have been reported for patients who are refractory to both lenalidomide or bortezomib.43

Pomalidomide is a thalidomide analog and has activity in MM that is relapsed or refractory with acceptable response rates when used with dexamethasone.44 Carfilzomib is a PI approved for treatment of relapsed or refractory MM in patients who have failed lenalidomide and bortezomib.45 The FDA recently approved panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, for patients with MM who have failed 2 prior therapies, and it has shown improved PFS.46 Patients should be treated in a clinical trial whenever possible, and emerging new options include second generation PIs, such as ixazomib, other histone deacetlyase inhibitors, AKT/P13K/mTOR inhibitors, heat-shock-protein inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies.

Conclusions

Despite significant advances in the management of MM, the disease remains incurable. Virtually all patients will develop relapsed disease, although strides in the field have provided opportunities for longer term remissions. There are a multitude of strategies that are under investigation, and further studies are needed to establish their role in the treatment of patients with MM.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disease that is primarily treated by hematologists; however, it is important for primary care providers (PCPs) to be aware of the presentation and diagnosis of this disease. Multiple myeloma often is seen in the veteran population, and VA providers should be familiar with its diagnosis and treatment so that an appropriate referral can be made. Often, the initial signs and symptoms of the disease are subtle and require an astute eye by the PCP to diagnose and initiate a workup.

Once a veteran has an established diagnosis of MM or one of its precursor syndromes, the PCP will invariably be alerted to an adverse event (AE) of treatment or complication of the disease and should be aware of such complications to assist in management or referral. Patients with MM may achieve long-term remission; therefore, it is likely that the PCP will see an evolution in their treatment and care. Last, PCPs and patients often have a close relationship, and patients expect the PCP to understand their diagnosis and treatment plan.

Presentation

Multiple myeloma is a disease in which a neoplastic proliferation of plasma cells produces a monoclonal immunoglobulin. It is almost invariably preceded by premalignant stages of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) and smoldering MM (SMM), although not all cases of MGUS will eventually progress to MM.1 Common signs and symptoms include anemia, bone pain or lytic lesions on X-ray, kidney injury, fatigue, hypercalcemia, and weight loss.2 Anemia is usually a normocytic, normochromic anemia and can be due to involvement of the bone marrow, secondary to renal disease, or it may be dilutional, related to a high monoclonal protein (M protein) level.

There are several identifiable causes for renal disease in patients with MM, including light chain cast nephropathy, hypercalcemia, light chain amyloidosis, and light chain deposition disease. Without intervention, progressive renal damage may occur.3

Diagnosis

All patients with a suspected diagnosis of MM should undergo a basic workup, including complete blood count; peripheral blood smear; complete chemistry panel, including calcium and albumin; serum free light chain analysis (FLC); serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation; urinalysis; 24-hour urine collection for electrophoresis (UPEP) and immunofixation; serum B2-microglobulin; and lactate dehydrogenase.4 A FLC analysis is particularly useful for the diagnosis and monitoring of MM, when only small amounts of M protein are secreted into the serum/urine or for nonsecretory myeloma, as well as for light-chainonly myeloma.5

A bone marrow biopsy and aspirate should be performed in the diagnosis of MM to evaluate the bone marrow involvement and genetic abnormality of myeloma cells with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and cytogenetics, both of which are very important in risk stratification and for treatment planning. A skeletal survey is also typically performed to look for bone lesions.4 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be useful to evaluate for possible soft tissue lesions when a bone survey is negative, or to evaluate for spinal cord compression.5 Additionally, an MRI should be performed in patients with SMM at the initial assessment, because focal lesions in the setting of SMM are associated with an increased risk to progression.6 Since plain radiographs are usually abnormal only after ≥ 30% of the bone is destroyed, an MRI offers a more sensitive image.

Two MM precursor syndromes are worth noting: MGUS and SMM. In evaluating a patient for possible MM, it is important to differentiate between MGUS, asymptomatic SMM, and MM that requires treatment.4 Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is diagnosed when a patient has a serum M protein that is < 3 g/dL, clonal bone marrow plasma cells < 10%, and no identifiable end organ damage.5 Smoldering MM is diagnosed when either the serum M protein is > 3 g/dL or bone marrow clonal plasma cells are > 10% in the absence of end organ damage.

Symptomatic MM is characterized by > 10% clonal bone marrow involvement with end organ damage that includes hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia, or bone lesions. The diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1. The International Myeloma Working Group produced updated guidelines in 2014, which now include patients with > 60% bone marrow involvement of plasma cells, serum FLC ratio of > 100, and > 1 focal lesions on an MRI study as symptomatic MM.5,6

Most patients with MM will have a M protein produced by the malignant plasma cells detected on an SPEP or UPEP. The majority of immunoglobulins were IgG and IgA, whereas IgD and IgM were much less common.2 A minority of patients will not have a detectable M protein on SPEP or UPEP. Some patients will produce only light chains and are designated as light-chain-only myeloma. For these patients, the FLC assay is useful for diagnosis and disease monitoring. Patients who have an absence of M protein on SPEP/UPEP and normal FLC assay ratios are considered to have nonsecretory myeloma.7

Staging and Risk Stratification

Two staging systems are used to evaluate a patient’s prognosis: the Durie-Salmon staging system, which is based on tumor burden (Table 2); and the International Staging System (ISS), which uses a combination of serum beta 2 microglobulin (B2M) and serum albumin levels to produce a powerful and reproducible 3-stage classification and is more commonly used by hematologists due to its simplicity to use and reliable reproducibility (Table 3).

In the Durie-Salmon staging system, patients with stage I disease have a lower tumor burden, defined as hemoglobin > 10 g/dL, normal calcium level, no evidence of lytic bone lesions, and low amounts of protein produced (IgG < 5 g/dL; IgA < 3 g/dL; urine protein < 4 g/d). Patients are classified as stage III if they have any of the following: hemoglobin < 8.5 g/dL, hypercalcemia with level > 12 mg/dL, bony lytic lesions, or high amounts of protein produced (IgG > 7 g/dL; IgA > 5 g/dL; or urine protein > 12 g/d). Patients with stage II disease do not fall into either of these categories. Stage III disease can be further differentiated into stage IIIA or stage IIIB disease if renal involvement is present.8

In the ISS system, patients with stage I disease have B2M levels that are < 3.5 mg/dL and albumin levels > 3.5 g/dL and have a median overall survival (OS) of 62 months. In this classification, stage III patients have B2M levels that are > 5.5 mg/dL and median OS was 29 months. Stage II patients do not meet either of these criteria and OS was 44 months.9 In a study by Mayo Clinic, OS has improved over the past decade, with OS for ISS stage III patients increasing to 4.2 years. Overall survival for both ISS stage I and stage III disease seems to have increased as well, although the end point has not been reached.10

All myeloma patients are risk stratified at initial diagnosis based on their cytogenetic abnormalities identified mainly by FISH studies and conventional cytogenetics, which can serve as an alternative if FISH is unavailable. Genetic abnormalities of MM are the major predictor for the outcome and will affect treatment choice. Three risk groups have been identified: high-risk, intermediate-risk, and standard-risk MM (Table 4).11

Management of MGUS and SMM

Patients with MGUS progress to malignant conditions at a rate of 1% per year.12 Those individuals who are diagnosed with MGUS or SMM typically do not require therapy. According to the International Myeloma Working Group guidelines, patients should be monitored based on risk stratification. Those with low-risk MGUS (IgG M protein < 1.5 g/dL and no abnormal FLC ratio) can be monitored every 6 months for 2 to

3 years. Those who are intermediate to high risk need a baseline bone marrow biopsy in addition to skeletal survey and should check urine and serum levels for protein every 6 months for the first year and then annually thereafter.

Patients with SMM are at an increased risk of progression to symptomatic MM compared with patients with MGUS (10% per year for the first 5 years, 3% per year for the next 5 years).13 Therefore, experts recommend physician visits and laboratory testing for M proteins every 2 to 3 months for the first year and then an evaluation every 6 to 12 months if the patient remains clinically stable.14 Additionally, there are new

data to suggest that early therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for SMM can prolong time to disease progression as well as increase OS in individuals with SMM at high risk for progression.15