User login

It’s time for universal CMV screening at birth

SAN FRANCISCO –

The reason is because most of the time the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus is missed. Only about 10% of infants infected with the virus present with enlarged livers and other classic signs. Too often, the infection isn’t caught until later, when hearing loss and other neurologic sequelae reveal themselves, according to Fatima Kakkar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and researcher at the University of Montreal.

There are effective treatments – intravenous ganciclovir for 6 weeks or oral valganciclovir (Valcyte) for 6 months – that control the infection and reverse its effects.

People have tried to address the situation by screening children with hearing loss, in utero HIV exposure, or cytomegalovirus symptoms, but in a study Dr. Kakkar presented at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, such targeted efforts still missed a lot of children.

Many think the answer is universal screening, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are considering it. In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Kakkar explained the issues, her study, and why universal screening is gaining support.

SOURCE: Kakkar F et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 115.

SAN FRANCISCO –

The reason is because most of the time the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus is missed. Only about 10% of infants infected with the virus present with enlarged livers and other classic signs. Too often, the infection isn’t caught until later, when hearing loss and other neurologic sequelae reveal themselves, according to Fatima Kakkar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and researcher at the University of Montreal.

There are effective treatments – intravenous ganciclovir for 6 weeks or oral valganciclovir (Valcyte) for 6 months – that control the infection and reverse its effects.

People have tried to address the situation by screening children with hearing loss, in utero HIV exposure, or cytomegalovirus symptoms, but in a study Dr. Kakkar presented at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, such targeted efforts still missed a lot of children.

Many think the answer is universal screening, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are considering it. In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Kakkar explained the issues, her study, and why universal screening is gaining support.

SOURCE: Kakkar F et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 115.

SAN FRANCISCO –

The reason is because most of the time the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus is missed. Only about 10% of infants infected with the virus present with enlarged livers and other classic signs. Too often, the infection isn’t caught until later, when hearing loss and other neurologic sequelae reveal themselves, according to Fatima Kakkar, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and researcher at the University of Montreal.

There are effective treatments – intravenous ganciclovir for 6 weeks or oral valganciclovir (Valcyte) for 6 months – that control the infection and reverse its effects.

People have tried to address the situation by screening children with hearing loss, in utero HIV exposure, or cytomegalovirus symptoms, but in a study Dr. Kakkar presented at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, such targeted efforts still missed a lot of children.

Many think the answer is universal screening, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are considering it. In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Kakkar explained the issues, her study, and why universal screening is gaining support.

SOURCE: Kakkar F et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 115.

REPORTING FROM IDWEEK 2018

The devil is in the headlines

“Breast Milk From Bottle May Not Be As Beneficial As Feeding Directly From The Breast, Researchers Say.” This was the headline on the AAP Daily Briefing that was sent to American Academy of Pediatrics members on Sept 25, 2018.

I suspect that this finding doesn’t surprise you. I can imagine a dozen factors that could make bottled breast milk less advantageous for a baby than milk received directly from the mother’s breast. Antibodies might adhere to the glass surface. A few degrees above or below body temperature could interfere with gastric emptying. Or a temptation to focus on the level in the bottle and inadvertently overfeed could inflate the baby’s body mass index at 3 months, as was found in the study published online in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics (“Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food”).

I agree that the title of the actual paper is rather dry; it’s a scientific research paper. But the distillation chosen by the folks at AAP Daily Briefing seems ill advised. They were not alone. CCN-Health chose “Breastfeeding better for babies’ weight gain than pumping, new study says” (Michael Nedelman, Sept. 24, 2018). HealthDay News headlined its story with “Milk straight from breast best for baby’s weight” (Sept. 24, 2018).

The articles themselves were well balanced and accurately described this research based on more than 2,500 Canadian mother-infant dyads. But not everyone – including mothers who are struggling with or considering breastfeeding – reads beyond the headlines. How many realize that “better for babies’ weight gain” means a slower weight gain? For the mother who has found that, for a variety of reasons, pumping is the only way she can provide her baby the benefits of breast milk, what these headlines suggest is another blow to her already fragile sense of self-worth.

This research article is excellent and should be read by all of us who counsel young families. It suggests that one of the contributors to our epidemic of childhood obesity may be that bottle-feeding discourages the infant’s own self-regulation skills. It should prompt us to ask every parent who is bottle-feeding his or her baby – regardless of what is in the bottle – exactly how they decide how much to put in the bottle and how long a feeding takes. Even if we are comfortable with the infant’s weight gain, we should caution parents to be more aware of the baby’s cues that he or she has had enough. Not every baby provides cues that are obvious, and parents may need our coaching in deciding how much to feed. This research paper also suggests that as long as breastfeeding was continued, introduction of solids as early as 5 months was not associated with an unhealthy BMI trajectory.

Unfortunately, the reporting of this research article is another example of the hazards of the explosive growth of the Internet. There really is no reason to keep the results of well-crafted research from the lay public, particularly if they are explained in common sense language. However, this places a burden of responsibility on the editors of websites to consider the damage that can be done by a poorly chosen headline.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

“Breast Milk From Bottle May Not Be As Beneficial As Feeding Directly From The Breast, Researchers Say.” This was the headline on the AAP Daily Briefing that was sent to American Academy of Pediatrics members on Sept 25, 2018.

I suspect that this finding doesn’t surprise you. I can imagine a dozen factors that could make bottled breast milk less advantageous for a baby than milk received directly from the mother’s breast. Antibodies might adhere to the glass surface. A few degrees above or below body temperature could interfere with gastric emptying. Or a temptation to focus on the level in the bottle and inadvertently overfeed could inflate the baby’s body mass index at 3 months, as was found in the study published online in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics (“Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food”).

I agree that the title of the actual paper is rather dry; it’s a scientific research paper. But the distillation chosen by the folks at AAP Daily Briefing seems ill advised. They were not alone. CCN-Health chose “Breastfeeding better for babies’ weight gain than pumping, new study says” (Michael Nedelman, Sept. 24, 2018). HealthDay News headlined its story with “Milk straight from breast best for baby’s weight” (Sept. 24, 2018).

The articles themselves were well balanced and accurately described this research based on more than 2,500 Canadian mother-infant dyads. But not everyone – including mothers who are struggling with or considering breastfeeding – reads beyond the headlines. How many realize that “better for babies’ weight gain” means a slower weight gain? For the mother who has found that, for a variety of reasons, pumping is the only way she can provide her baby the benefits of breast milk, what these headlines suggest is another blow to her already fragile sense of self-worth.

This research article is excellent and should be read by all of us who counsel young families. It suggests that one of the contributors to our epidemic of childhood obesity may be that bottle-feeding discourages the infant’s own self-regulation skills. It should prompt us to ask every parent who is bottle-feeding his or her baby – regardless of what is in the bottle – exactly how they decide how much to put in the bottle and how long a feeding takes. Even if we are comfortable with the infant’s weight gain, we should caution parents to be more aware of the baby’s cues that he or she has had enough. Not every baby provides cues that are obvious, and parents may need our coaching in deciding how much to feed. This research paper also suggests that as long as breastfeeding was continued, introduction of solids as early as 5 months was not associated with an unhealthy BMI trajectory.

Unfortunately, the reporting of this research article is another example of the hazards of the explosive growth of the Internet. There really is no reason to keep the results of well-crafted research from the lay public, particularly if they are explained in common sense language. However, this places a burden of responsibility on the editors of websites to consider the damage that can be done by a poorly chosen headline.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

“Breast Milk From Bottle May Not Be As Beneficial As Feeding Directly From The Breast, Researchers Say.” This was the headline on the AAP Daily Briefing that was sent to American Academy of Pediatrics members on Sept 25, 2018.

I suspect that this finding doesn’t surprise you. I can imagine a dozen factors that could make bottled breast milk less advantageous for a baby than milk received directly from the mother’s breast. Antibodies might adhere to the glass surface. A few degrees above or below body temperature could interfere with gastric emptying. Or a temptation to focus on the level in the bottle and inadvertently overfeed could inflate the baby’s body mass index at 3 months, as was found in the study published online in the September 2018 issue of Pediatrics (“Infant Feeding and Weight Gain: Separating Breast Milk From Breastfeeding and Formula From Food”).

I agree that the title of the actual paper is rather dry; it’s a scientific research paper. But the distillation chosen by the folks at AAP Daily Briefing seems ill advised. They were not alone. CCN-Health chose “Breastfeeding better for babies’ weight gain than pumping, new study says” (Michael Nedelman, Sept. 24, 2018). HealthDay News headlined its story with “Milk straight from breast best for baby’s weight” (Sept. 24, 2018).

The articles themselves were well balanced and accurately described this research based on more than 2,500 Canadian mother-infant dyads. But not everyone – including mothers who are struggling with or considering breastfeeding – reads beyond the headlines. How many realize that “better for babies’ weight gain” means a slower weight gain? For the mother who has found that, for a variety of reasons, pumping is the only way she can provide her baby the benefits of breast milk, what these headlines suggest is another blow to her already fragile sense of self-worth.

This research article is excellent and should be read by all of us who counsel young families. It suggests that one of the contributors to our epidemic of childhood obesity may be that bottle-feeding discourages the infant’s own self-regulation skills. It should prompt us to ask every parent who is bottle-feeding his or her baby – regardless of what is in the bottle – exactly how they decide how much to put in the bottle and how long a feeding takes. Even if we are comfortable with the infant’s weight gain, we should caution parents to be more aware of the baby’s cues that he or she has had enough. Not every baby provides cues that are obvious, and parents may need our coaching in deciding how much to feed. This research paper also suggests that as long as breastfeeding was continued, introduction of solids as early as 5 months was not associated with an unhealthy BMI trajectory.

Unfortunately, the reporting of this research article is another example of the hazards of the explosive growth of the Internet. There really is no reason to keep the results of well-crafted research from the lay public, particularly if they are explained in common sense language. However, this places a burden of responsibility on the editors of websites to consider the damage that can be done by a poorly chosen headline.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Methadone may shorten NICU stays for neonatal abstinence syndrome

Lengths of stay in the hospital and in the neonatal ICU (NICU) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) were significantly shorter with methadone treatment, compared with morphine treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Veeral N. Tolia, MD, of Baylor University in Dallas, and his associates, gathered data from NICUs participating in the Clinical Data Warehouse and identified 7,667 singleton infants with no congenital abnormalities treated for NAS with either methadone (15%) or morphine (85%) in the first 7 days of life during 2011-2015.

The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 18 days (interquartile range, 11-30 days) for infants treated with methadone and 23 days (IQR, 16-33 days) for those treated with morphine (P less than .001). The methadone-treated infants also had a shorter median LOS in the NICU than did the morphine-treated infants: 17 days (IQR, 10-29 days) versus 21 days (IQR, 14-36 days; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis, methadone treatment still was associated with a significantly shorter LOS in both cases. The methadone-treated infants also were significantly less likely to require two medications or three or more medications, compared with the morphine treated infants.

Although there was only a modest difference in LOS, Dr. Tolia and associates consider their findings relevant to clinical practice and are important given that “NAS incidence continues to rise and accounts for a substantial portion of health care utilization, including a fourfold increase in the proportion of neonatal hospital costs of all births covered by Medicaid.”

One of the strengths of this study is the size of its cohort; among its weaknesses is that the Clinical Data Warehouse does not include information on symptom severity, indication for starting therapy, or weaning practices.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tolia VN et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.061.

Lengths of stay in the hospital and in the neonatal ICU (NICU) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) were significantly shorter with methadone treatment, compared with morphine treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Veeral N. Tolia, MD, of Baylor University in Dallas, and his associates, gathered data from NICUs participating in the Clinical Data Warehouse and identified 7,667 singleton infants with no congenital abnormalities treated for NAS with either methadone (15%) or morphine (85%) in the first 7 days of life during 2011-2015.

The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 18 days (interquartile range, 11-30 days) for infants treated with methadone and 23 days (IQR, 16-33 days) for those treated with morphine (P less than .001). The methadone-treated infants also had a shorter median LOS in the NICU than did the morphine-treated infants: 17 days (IQR, 10-29 days) versus 21 days (IQR, 14-36 days; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis, methadone treatment still was associated with a significantly shorter LOS in both cases. The methadone-treated infants also were significantly less likely to require two medications or three or more medications, compared with the morphine treated infants.

Although there was only a modest difference in LOS, Dr. Tolia and associates consider their findings relevant to clinical practice and are important given that “NAS incidence continues to rise and accounts for a substantial portion of health care utilization, including a fourfold increase in the proportion of neonatal hospital costs of all births covered by Medicaid.”

One of the strengths of this study is the size of its cohort; among its weaknesses is that the Clinical Data Warehouse does not include information on symptom severity, indication for starting therapy, or weaning practices.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tolia VN et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.061.

Lengths of stay in the hospital and in the neonatal ICU (NICU) for infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) were significantly shorter with methadone treatment, compared with morphine treatment, according to a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics.

Veeral N. Tolia, MD, of Baylor University in Dallas, and his associates, gathered data from NICUs participating in the Clinical Data Warehouse and identified 7,667 singleton infants with no congenital abnormalities treated for NAS with either methadone (15%) or morphine (85%) in the first 7 days of life during 2011-2015.

The median hospital length of stay (LOS) was 18 days (interquartile range, 11-30 days) for infants treated with methadone and 23 days (IQR, 16-33 days) for those treated with morphine (P less than .001). The methadone-treated infants also had a shorter median LOS in the NICU than did the morphine-treated infants: 17 days (IQR, 10-29 days) versus 21 days (IQR, 14-36 days; P less than .001). In multivariable analysis, methadone treatment still was associated with a significantly shorter LOS in both cases. The methadone-treated infants also were significantly less likely to require two medications or three or more medications, compared with the morphine treated infants.

Although there was only a modest difference in LOS, Dr. Tolia and associates consider their findings relevant to clinical practice and are important given that “NAS incidence continues to rise and accounts for a substantial portion of health care utilization, including a fourfold increase in the proportion of neonatal hospital costs of all births covered by Medicaid.”

One of the strengths of this study is the size of its cohort; among its weaknesses is that the Clinical Data Warehouse does not include information on symptom severity, indication for starting therapy, or weaning practices.

The researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tolia VN et al. J Pediatr. 2018 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.061.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Congenital syphilis rates continue skyrocketing alongside other STDs

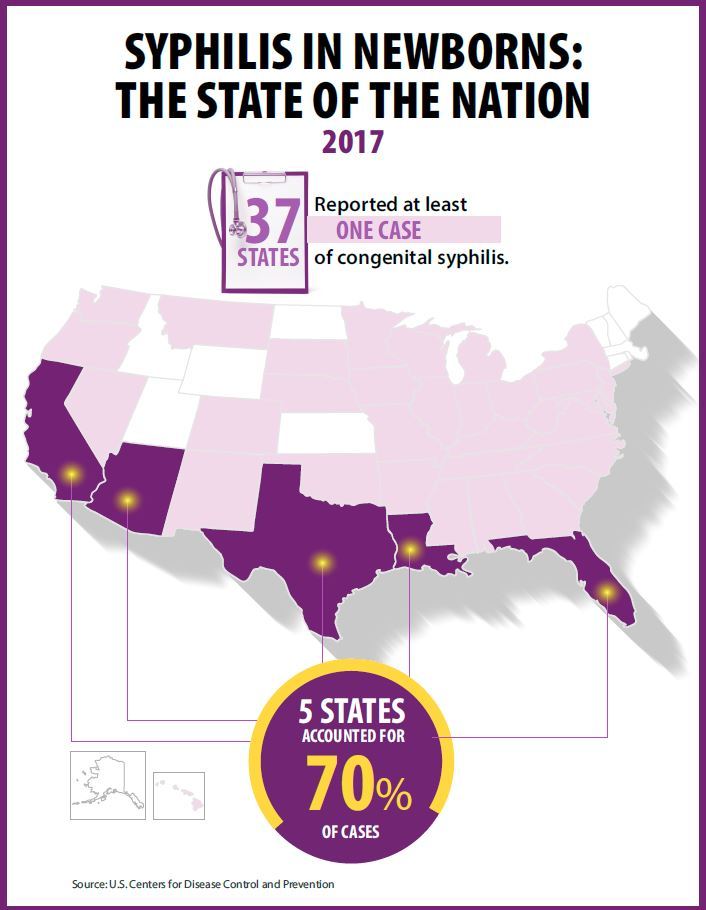

Rapidly increasing cases of newborn syphilis have reached their highest prevalence in 2 decades, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on sexually transmitted disease surveillance in 2017.

Newborn syphilis incidence has more than doubled, from 362 cases in 2013 to 918 cases in 2017, resulting in 64 syphilitic stillbirths and 13 infant deaths that year, according to data published in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

At least one case was reported in 37 states last year, and the greatest burden of cases occurred in California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, together accounting for 70% of all 2017 cases.

“The resurgence of syphilis, and particularly congenital syphilis, is not an arbitrary event, but rather a symptom of a deteriorating public health infrastructure and lack of access to health care,” wrote Gail Bolan, MD, director of the Division of STD Prevention at the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “It is exposing hidden, fragile populations in need that are not getting the health care and preventive services they deserve.”

Dr. Bolan recommends modernizing surveillance to capture more of the cases in populations without ready access to diagnosis and treatment and in those choosing not to access care.

“It is imperative that federal, state, and local programs employ strategies that maximize long-term population impact by reducing STD incidence and promoting sexual, reproductive, maternal, and infant health,” she wrote. “Further, it will be important for us to measure and monitor the adverse health consequences of STDs, such as ocular and neurosyphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, HIV, congenital syphilis, and neonatal herpes.”

Multiple sources contributed data to the report: state and local STD programs’ notifiable disease reporting, private and federal national surveys, and specific projects that collect STD prevalence data, including the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

The four nationally notifiable STDs are chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid.

The rise in newborn syphilis cases, currently at 23.3 cases per 100,000 live births, mirrors the increased U.S. prevalence of both primary and secondary syphilis in 2017, with 9.5 cases per 100,000 people. Syphilis has increased every year since 2000-2001, when prevalence was at a record low.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates climb too

The report also noted increases in the prevalence of other STDs. Chlamydia, the most common STD, increased 6.9% as compared to 2016, with 528.8 cases per 100,000 people. This increase occurred in all U.S. regions and independently of sex, race, or ethnicity, though rates were highest in teens and young adults. Nearly two-thirds of chlamydia cases in 2017 occurred in people ages 15-24 years old.

Reported rates were higher in women than in men, likely due to women’s increased likelihood of undergoing screening, the report suggested. Better surveillance may also partly explain the climb in men’s cases.

“Increases in rates among men may reflect an increased number of men, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) being tested and diagnosed with a chlamydial infection due to increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening,” according to the report.

The CDC received reports of more than a half million gonorrhea infections in 2017 (555,608 cases), an increase of 18.6% since the previous year, including a 19.3% increase among men and a 17.8% increase among women.

“The magnitude of the increase among men suggests either increased transmission, increased case ascertainment (e.g., through increased extra-genital screening among MSM), or both,” the authors wrote. “The concurrent increase in cases reported among women suggests parallel increases in heterosexual transmission, increased screening among women, or both.”

Overall, gonorrhea cases have skyrocketed 75.2% since their historic low in 2009, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance that has limited CDC-recommended treatment to just ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

Rapidly increasing cases of newborn syphilis have reached their highest prevalence in 2 decades, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on sexually transmitted disease surveillance in 2017.

Newborn syphilis incidence has more than doubled, from 362 cases in 2013 to 918 cases in 2017, resulting in 64 syphilitic stillbirths and 13 infant deaths that year, according to data published in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

At least one case was reported in 37 states last year, and the greatest burden of cases occurred in California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, together accounting for 70% of all 2017 cases.

“The resurgence of syphilis, and particularly congenital syphilis, is not an arbitrary event, but rather a symptom of a deteriorating public health infrastructure and lack of access to health care,” wrote Gail Bolan, MD, director of the Division of STD Prevention at the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “It is exposing hidden, fragile populations in need that are not getting the health care and preventive services they deserve.”

Dr. Bolan recommends modernizing surveillance to capture more of the cases in populations without ready access to diagnosis and treatment and in those choosing not to access care.

“It is imperative that federal, state, and local programs employ strategies that maximize long-term population impact by reducing STD incidence and promoting sexual, reproductive, maternal, and infant health,” she wrote. “Further, it will be important for us to measure and monitor the adverse health consequences of STDs, such as ocular and neurosyphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, HIV, congenital syphilis, and neonatal herpes.”

Multiple sources contributed data to the report: state and local STD programs’ notifiable disease reporting, private and federal national surveys, and specific projects that collect STD prevalence data, including the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

The four nationally notifiable STDs are chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid.

The rise in newborn syphilis cases, currently at 23.3 cases per 100,000 live births, mirrors the increased U.S. prevalence of both primary and secondary syphilis in 2017, with 9.5 cases per 100,000 people. Syphilis has increased every year since 2000-2001, when prevalence was at a record low.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates climb too

The report also noted increases in the prevalence of other STDs. Chlamydia, the most common STD, increased 6.9% as compared to 2016, with 528.8 cases per 100,000 people. This increase occurred in all U.S. regions and independently of sex, race, or ethnicity, though rates were highest in teens and young adults. Nearly two-thirds of chlamydia cases in 2017 occurred in people ages 15-24 years old.

Reported rates were higher in women than in men, likely due to women’s increased likelihood of undergoing screening, the report suggested. Better surveillance may also partly explain the climb in men’s cases.

“Increases in rates among men may reflect an increased number of men, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) being tested and diagnosed with a chlamydial infection due to increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening,” according to the report.

The CDC received reports of more than a half million gonorrhea infections in 2017 (555,608 cases), an increase of 18.6% since the previous year, including a 19.3% increase among men and a 17.8% increase among women.

“The magnitude of the increase among men suggests either increased transmission, increased case ascertainment (e.g., through increased extra-genital screening among MSM), or both,” the authors wrote. “The concurrent increase in cases reported among women suggests parallel increases in heterosexual transmission, increased screening among women, or both.”

Overall, gonorrhea cases have skyrocketed 75.2% since their historic low in 2009, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance that has limited CDC-recommended treatment to just ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

Rapidly increasing cases of newborn syphilis have reached their highest prevalence in 2 decades, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on sexually transmitted disease surveillance in 2017.

Newborn syphilis incidence has more than doubled, from 362 cases in 2013 to 918 cases in 2017, resulting in 64 syphilitic stillbirths and 13 infant deaths that year, according to data published in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

At least one case was reported in 37 states last year, and the greatest burden of cases occurred in California, Arizona, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida, together accounting for 70% of all 2017 cases.

“The resurgence of syphilis, and particularly congenital syphilis, is not an arbitrary event, but rather a symptom of a deteriorating public health infrastructure and lack of access to health care,” wrote Gail Bolan, MD, director of the Division of STD Prevention at the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “It is exposing hidden, fragile populations in need that are not getting the health care and preventive services they deserve.”

Dr. Bolan recommends modernizing surveillance to capture more of the cases in populations without ready access to diagnosis and treatment and in those choosing not to access care.

“It is imperative that federal, state, and local programs employ strategies that maximize long-term population impact by reducing STD incidence and promoting sexual, reproductive, maternal, and infant health,” she wrote. “Further, it will be important for us to measure and monitor the adverse health consequences of STDs, such as ocular and neurosyphilis, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, infertility, HIV, congenital syphilis, and neonatal herpes.”

Multiple sources contributed data to the report: state and local STD programs’ notifiable disease reporting, private and federal national surveys, and specific projects that collect STD prevalence data, including the National Job Training Program, the STD Surveillance Network and the Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project.

The four nationally notifiable STDs are chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid.

The rise in newborn syphilis cases, currently at 23.3 cases per 100,000 live births, mirrors the increased U.S. prevalence of both primary and secondary syphilis in 2017, with 9.5 cases per 100,000 people. Syphilis has increased every year since 2000-2001, when prevalence was at a record low.

Chlamydia and gonorrhea rates climb too

The report also noted increases in the prevalence of other STDs. Chlamydia, the most common STD, increased 6.9% as compared to 2016, with 528.8 cases per 100,000 people. This increase occurred in all U.S. regions and independently of sex, race, or ethnicity, though rates were highest in teens and young adults. Nearly two-thirds of chlamydia cases in 2017 occurred in people ages 15-24 years old.

Reported rates were higher in women than in men, likely due to women’s increased likelihood of undergoing screening, the report suggested. Better surveillance may also partly explain the climb in men’s cases.

“Increases in rates among men may reflect an increased number of men, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (collectively referred to as MSM) being tested and diagnosed with a chlamydial infection due to increased availability of urine testing and extragenital screening,” according to the report.

The CDC received reports of more than a half million gonorrhea infections in 2017 (555,608 cases), an increase of 18.6% since the previous year, including a 19.3% increase among men and a 17.8% increase among women.

“The magnitude of the increase among men suggests either increased transmission, increased case ascertainment (e.g., through increased extra-genital screening among MSM), or both,” the authors wrote. “The concurrent increase in cases reported among women suggests parallel increases in heterosexual transmission, increased screening among women, or both.”

Overall, gonorrhea cases have skyrocketed 75.2% since their historic low in 2009, compounding the problem of antibiotic resistance that has limited CDC-recommended treatment to just ceftriaxone and azithromycin.

The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats

Key clinical point: Newborn syphilis cases have more than doubled in 5 years along with substantial increases in chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis.

Major finding: 918 cases of newborn syphilis were reported in 37 states in 2017.

Study details: The findings are based on data from public health notifiable disease reports and multiple federal and private surveillance projects.

Disclosures: The report was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors did not report having any disclosures.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017.

How to screen for, manage FASD in a medical home

providing early intervention and accessing community resources, according to a clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

After the AAP released its guidelines on fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in 2015, some pediatricians asked for further guidance on how to care for patients with FASD within the medical home, as many had a knowledge gap on how to best manage these patients.

“For some pediatricians, it can seem like a daunting task to care for an individual with an FASD, but there are aspects of integrated care and providing a medical home that can be instituted as with all children with complex medical diagnoses,” wrote Renee M. Turchi, MD, MPH, of the department of pediatrics at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children and Drexel Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, and her colleagues on the AAP Committee on Substance Abuse and the Council on Children with Disabilities. Their report is in Pediatrics. “In addition, not recognizing an FASD can lead to inadequate treatment and less-than-optimal outcomes for the patient and family.”

Dr. Turchi and her colleagues released the FASD clinical report with “strategies to support families who are interacting with early intervention services, the educational system, the behavioral and/or mental health system, other community resources, and the transition to adult-oriented heath care systems when appropriate.” They noted the prevalence of FASD is increasing, with 1 in 10 pregnant women using alcohol within the past 30 days and 1 in 33 pregnant women reporting binge drinking in the past 30 days. They reaffirmed the AAP’s endorsement from the 2015 clinical report on FASD regarding abstinence of alcohol for pregnant women, emphasizing that there is no amount or kind of alcohol that is risk free during pregnancy, nor is there a time in pregnancy when drinking alcohol is risk free.

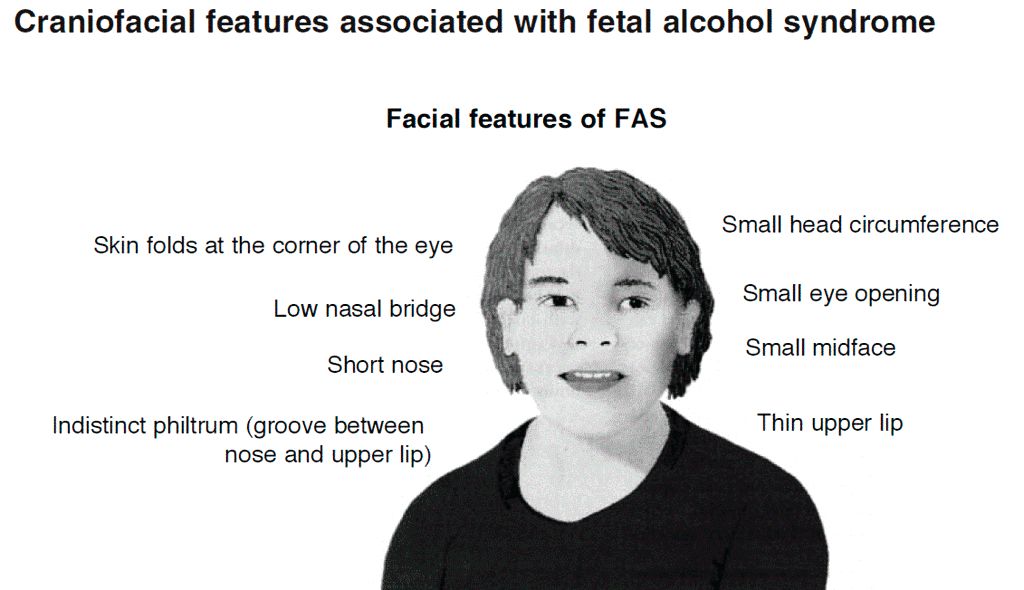

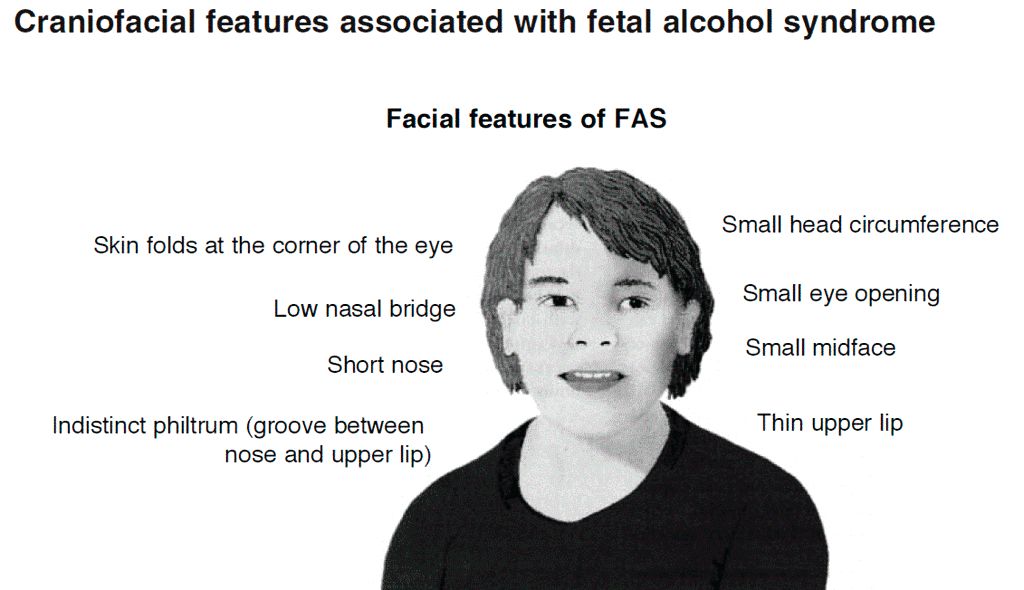

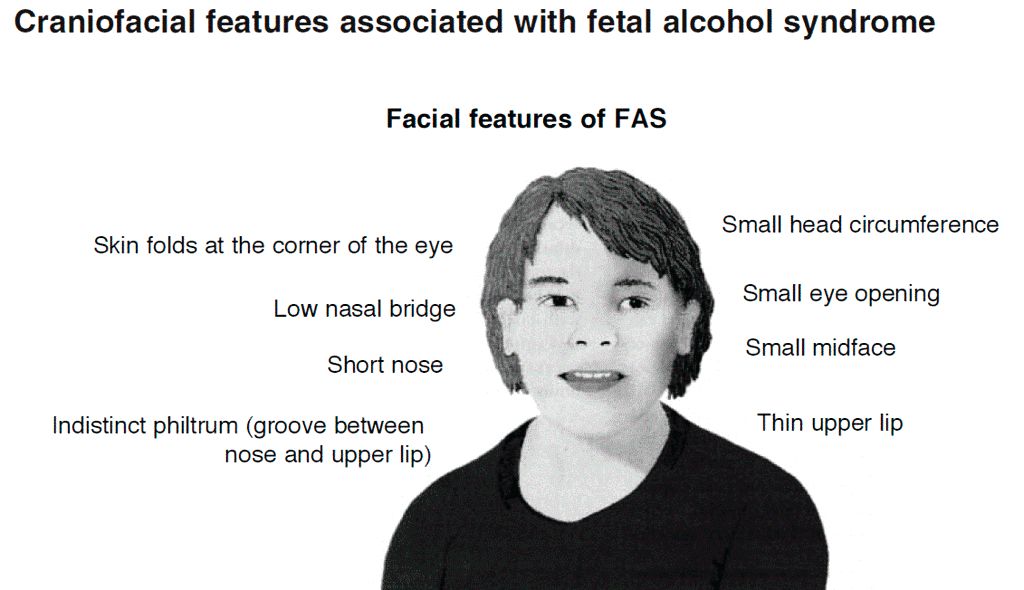

Providers in a medical home should communicate any prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) to obstetric providers so they can review risk factors, optimize screening, and monitor children, Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said. They also should understand the diagnostic criteria and classifications for FASDs, including physical features such as low weight, short palpebral features, smooth philtrum, a thin upper lip, abnormalities in the central nervous system, and any alcohol use during pregnancy. Any child – regardless of age – is a candidate for universal PAE screening at initial visits or when “additional cognitive and behavioral concerns arise.”

The federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act “does not require clinicians to report to child protective services if a child has been exposed prenatally to alcohol (i.e., for a positive PAE screening result). Referral to child protective services is required if the child has been diagnosed with an FASD in the period between birth and 3 years. The intent of this referral is to develop safe care and possible treatment plans for the infant and caregiver if needed, not to initiate punitive actions,” according to the report. States have their own definitions about child abuse and neglect, so the report encourages providers to know the mandates and reporting laws in the states where they practice.

Monitoring children in a medical home for the signs and symptoms of FASD is important, the authors said, because research has shown an increased chance at reducing adverse life outcomes if a child is diagnosed before age 6 and is in a stable home with access to support services.

Management of children with FASD is individual, as symptoms for each child will uniquely present not just in terms of physical issues such as growth or congenital defects affecting the heart, eyes, kidneys, or bones, but also as developmental, cognitive, and behavioral problems. Children with FASD also may receive a concomitant diagnosis when evaluated, such as ADHD or depression, that will require additional accommodation. The use of evidence-based diagnostic and standard screening approaches and referring when necessary will help reevaluate whether a child has a condition such as ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or another diagnosis, or is displaying symptoms of FASD such as a receptive or expressive language disorder.

Pediatricians must work together with the families, educational professionals, the mental health community, and therapists to help manage FASD in children. In cases where a child is in foster care, partnering with the foster care partners and child welfare agencies to gain access to the medical information of the biological parents is important to determine whether there is parental history of substance abuse and to provide appropriate treatment and interventions.

“Given the complex array of systems and services requiring navigation and coordination for children with an FASD and their families, a high-quality primary care medical home with partnerships with families, specialists, therapists, mental and/or behavioral health professionals, and community partners is critical, as it is for all children with special health care needs,” Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Turchi RM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 10. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2333.

providing early intervention and accessing community resources, according to a clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

After the AAP released its guidelines on fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in 2015, some pediatricians asked for further guidance on how to care for patients with FASD within the medical home, as many had a knowledge gap on how to best manage these patients.

“For some pediatricians, it can seem like a daunting task to care for an individual with an FASD, but there are aspects of integrated care and providing a medical home that can be instituted as with all children with complex medical diagnoses,” wrote Renee M. Turchi, MD, MPH, of the department of pediatrics at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children and Drexel Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, and her colleagues on the AAP Committee on Substance Abuse and the Council on Children with Disabilities. Their report is in Pediatrics. “In addition, not recognizing an FASD can lead to inadequate treatment and less-than-optimal outcomes for the patient and family.”

Dr. Turchi and her colleagues released the FASD clinical report with “strategies to support families who are interacting with early intervention services, the educational system, the behavioral and/or mental health system, other community resources, and the transition to adult-oriented heath care systems when appropriate.” They noted the prevalence of FASD is increasing, with 1 in 10 pregnant women using alcohol within the past 30 days and 1 in 33 pregnant women reporting binge drinking in the past 30 days. They reaffirmed the AAP’s endorsement from the 2015 clinical report on FASD regarding abstinence of alcohol for pregnant women, emphasizing that there is no amount or kind of alcohol that is risk free during pregnancy, nor is there a time in pregnancy when drinking alcohol is risk free.

Providers in a medical home should communicate any prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) to obstetric providers so they can review risk factors, optimize screening, and monitor children, Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said. They also should understand the diagnostic criteria and classifications for FASDs, including physical features such as low weight, short palpebral features, smooth philtrum, a thin upper lip, abnormalities in the central nervous system, and any alcohol use during pregnancy. Any child – regardless of age – is a candidate for universal PAE screening at initial visits or when “additional cognitive and behavioral concerns arise.”

The federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act “does not require clinicians to report to child protective services if a child has been exposed prenatally to alcohol (i.e., for a positive PAE screening result). Referral to child protective services is required if the child has been diagnosed with an FASD in the period between birth and 3 years. The intent of this referral is to develop safe care and possible treatment plans for the infant and caregiver if needed, not to initiate punitive actions,” according to the report. States have their own definitions about child abuse and neglect, so the report encourages providers to know the mandates and reporting laws in the states where they practice.

Monitoring children in a medical home for the signs and symptoms of FASD is important, the authors said, because research has shown an increased chance at reducing adverse life outcomes if a child is diagnosed before age 6 and is in a stable home with access to support services.

Management of children with FASD is individual, as symptoms for each child will uniquely present not just in terms of physical issues such as growth or congenital defects affecting the heart, eyes, kidneys, or bones, but also as developmental, cognitive, and behavioral problems. Children with FASD also may receive a concomitant diagnosis when evaluated, such as ADHD or depression, that will require additional accommodation. The use of evidence-based diagnostic and standard screening approaches and referring when necessary will help reevaluate whether a child has a condition such as ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or another diagnosis, or is displaying symptoms of FASD such as a receptive or expressive language disorder.

Pediatricians must work together with the families, educational professionals, the mental health community, and therapists to help manage FASD in children. In cases where a child is in foster care, partnering with the foster care partners and child welfare agencies to gain access to the medical information of the biological parents is important to determine whether there is parental history of substance abuse and to provide appropriate treatment and interventions.

“Given the complex array of systems and services requiring navigation and coordination for children with an FASD and their families, a high-quality primary care medical home with partnerships with families, specialists, therapists, mental and/or behavioral health professionals, and community partners is critical, as it is for all children with special health care needs,” Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Turchi RM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 10. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2333.

providing early intervention and accessing community resources, according to a clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

After the AAP released its guidelines on fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in 2015, some pediatricians asked for further guidance on how to care for patients with FASD within the medical home, as many had a knowledge gap on how to best manage these patients.

“For some pediatricians, it can seem like a daunting task to care for an individual with an FASD, but there are aspects of integrated care and providing a medical home that can be instituted as with all children with complex medical diagnoses,” wrote Renee M. Turchi, MD, MPH, of the department of pediatrics at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children and Drexel Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, and her colleagues on the AAP Committee on Substance Abuse and the Council on Children with Disabilities. Their report is in Pediatrics. “In addition, not recognizing an FASD can lead to inadequate treatment and less-than-optimal outcomes for the patient and family.”

Dr. Turchi and her colleagues released the FASD clinical report with “strategies to support families who are interacting with early intervention services, the educational system, the behavioral and/or mental health system, other community resources, and the transition to adult-oriented heath care systems when appropriate.” They noted the prevalence of FASD is increasing, with 1 in 10 pregnant women using alcohol within the past 30 days and 1 in 33 pregnant women reporting binge drinking in the past 30 days. They reaffirmed the AAP’s endorsement from the 2015 clinical report on FASD regarding abstinence of alcohol for pregnant women, emphasizing that there is no amount or kind of alcohol that is risk free during pregnancy, nor is there a time in pregnancy when drinking alcohol is risk free.

Providers in a medical home should communicate any prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) to obstetric providers so they can review risk factors, optimize screening, and monitor children, Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said. They also should understand the diagnostic criteria and classifications for FASDs, including physical features such as low weight, short palpebral features, smooth philtrum, a thin upper lip, abnormalities in the central nervous system, and any alcohol use during pregnancy. Any child – regardless of age – is a candidate for universal PAE screening at initial visits or when “additional cognitive and behavioral concerns arise.”

The federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act “does not require clinicians to report to child protective services if a child has been exposed prenatally to alcohol (i.e., for a positive PAE screening result). Referral to child protective services is required if the child has been diagnosed with an FASD in the period between birth and 3 years. The intent of this referral is to develop safe care and possible treatment plans for the infant and caregiver if needed, not to initiate punitive actions,” according to the report. States have their own definitions about child abuse and neglect, so the report encourages providers to know the mandates and reporting laws in the states where they practice.

Monitoring children in a medical home for the signs and symptoms of FASD is important, the authors said, because research has shown an increased chance at reducing adverse life outcomes if a child is diagnosed before age 6 and is in a stable home with access to support services.

Management of children with FASD is individual, as symptoms for each child will uniquely present not just in terms of physical issues such as growth or congenital defects affecting the heart, eyes, kidneys, or bones, but also as developmental, cognitive, and behavioral problems. Children with FASD also may receive a concomitant diagnosis when evaluated, such as ADHD or depression, that will require additional accommodation. The use of evidence-based diagnostic and standard screening approaches and referring when necessary will help reevaluate whether a child has a condition such as ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or another diagnosis, or is displaying symptoms of FASD such as a receptive or expressive language disorder.

Pediatricians must work together with the families, educational professionals, the mental health community, and therapists to help manage FASD in children. In cases where a child is in foster care, partnering with the foster care partners and child welfare agencies to gain access to the medical information of the biological parents is important to determine whether there is parental history of substance abuse and to provide appropriate treatment and interventions.

“Given the complex array of systems and services requiring navigation and coordination for children with an FASD and their families, a high-quality primary care medical home with partnerships with families, specialists, therapists, mental and/or behavioral health professionals, and community partners is critical, as it is for all children with special health care needs,” Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Turchi RM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 10. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2333.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Pertussis vaccine at birth shows immune response, tolerability

compared with a group receiving only the hepatitis B vaccine, a randomized clinical trial from Australia has found.

“These results indicate that a birth dose of aP vaccine is immunogenic in newborns and significantly narrows the immunity gap between birth and 14 days after receipt of DTaP at 6 or 8 weeks of age, marking the critical period when infants are most vulnerable to severe pertussis infection,” reported Nicholas Wood, PhD, of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

“Administration of the acellular pertussis vaccine at birth has the potential to reduce severe morbidity from Bordetella pertussis infection in the first 3 months of life, especially for infants of mothers who have not received a pertussis vaccine during pregnancy,” the researchers concluded in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers enrolled 417 infants from Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth between June 2010 and March 2013 and randomized them to receive either the hepatitis B vaccine alone (n = 205) or the hepatitis B vaccine with a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine (n = 212) within the first 5 days after birth. The randomization was stratified for mothers’ receipt of the Tdap before pregnancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth and that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy. There is not currently a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine licensed in the United States.

The study infants then received the hexavalent DTaP-Hib-hep B-polio vaccine and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months.

The primary outcome was detectable levels of IgG antibody to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks old.

Of the 206 infants receiving the pertussis vaccine at birth, 93% had detectable antibodies to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of the 193 infants who received only the hepatitis B shot (P less than .001). Geometric mean concentration for pertussis toxin IgG also was four times higher in infants who received the pertussis vaccine at birth.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups both at birth and at 32 weeks, demonstrating that the pertussis birth dose is safe and tolerable.

“More important, in this study, the prevalence of fever after receipt of the birth dose, which can mistakenly be associated with potential sepsis and result in additional investigations in the neonatal period, was similar in both the group that received the aP vaccine at birth and the control group,” the authors reported.

A remaining question is the potential impact of maternal antibodies on protection from pertussis.

“The presence of maternal pertussis antibodies at birth can negatively affect postprimary responses to pertussis, diphtheria, and diphtheria-related CRM197 conjugate vaccines with a variety of infant immunization schedules and vaccines,” the authors noted. “The clinical significance of reductions in pertussis antibody related to maternal interference will require ongoing clinical evaluation, because there are no accepted serologic correlates of protection.”

The research was funded by a Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wood N et al, JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

Pertussis is most likely to cause morbidity or kill neonates between birth and when they are given their first pertussis vaccine at 6-8 weeks of age. This is well known.

In the current study giving the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine at birth led to “significantly higher antibody titers to pertussis antigens at 10 weeks of age,” compared with those who did not receive it. Those infants who received the birth dose of aP vaccine also had higher pertussis antibodies at 6 weeks, whether or not their mothers had received Tdap within 5 years prior to delivery.

When this study began in 2009, maternal immunization was not a well accepted concept, but this attitude has changed, in part due to the safe vaccination of pregnant women with the pandemic flu vaccine. Despite this, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 data showed that only 49% of pregnant women in the United Stated received Tdap. These rates need to increase.

Administering the aP vaccine with the existing hepatitis B vaccine at birth to infants whose mothers who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy would be a practical solution, if the aP vaccine were universally available.

But the aP vaccine currently is not available in the United States and many other countries as a standalone vaccine, and the administration of DTaP as a birth dose has been linked with “significant immune interference.” The aP vaccine could have a place in countries where it is available, and there is no maternal immunization program. Otherwise, boosting maternal immunization appears to be the primary approach for now.

Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, is the Sarah H. Sell and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. She specializes in pediatric infectious diseases. These comments are a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wood et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2363). Dr. Edwards said she had no conflicts of interest.

Pertussis is most likely to cause morbidity or kill neonates between birth and when they are given their first pertussis vaccine at 6-8 weeks of age. This is well known.

In the current study giving the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine at birth led to “significantly higher antibody titers to pertussis antigens at 10 weeks of age,” compared with those who did not receive it. Those infants who received the birth dose of aP vaccine also had higher pertussis antibodies at 6 weeks, whether or not their mothers had received Tdap within 5 years prior to delivery.

When this study began in 2009, maternal immunization was not a well accepted concept, but this attitude has changed, in part due to the safe vaccination of pregnant women with the pandemic flu vaccine. Despite this, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 data showed that only 49% of pregnant women in the United Stated received Tdap. These rates need to increase.

Administering the aP vaccine with the existing hepatitis B vaccine at birth to infants whose mothers who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy would be a practical solution, if the aP vaccine were universally available.

But the aP vaccine currently is not available in the United States and many other countries as a standalone vaccine, and the administration of DTaP as a birth dose has been linked with “significant immune interference.” The aP vaccine could have a place in countries where it is available, and there is no maternal immunization program. Otherwise, boosting maternal immunization appears to be the primary approach for now.

Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, is the Sarah H. Sell and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. She specializes in pediatric infectious diseases. These comments are a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wood et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2363). Dr. Edwards said she had no conflicts of interest.

Pertussis is most likely to cause morbidity or kill neonates between birth and when they are given their first pertussis vaccine at 6-8 weeks of age. This is well known.

In the current study giving the acellular pertussis (aP) vaccine at birth led to “significantly higher antibody titers to pertussis antigens at 10 weeks of age,” compared with those who did not receive it. Those infants who received the birth dose of aP vaccine also had higher pertussis antibodies at 6 weeks, whether or not their mothers had received Tdap within 5 years prior to delivery.

When this study began in 2009, maternal immunization was not a well accepted concept, but this attitude has changed, in part due to the safe vaccination of pregnant women with the pandemic flu vaccine. Despite this, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016 data showed that only 49% of pregnant women in the United Stated received Tdap. These rates need to increase.

Administering the aP vaccine with the existing hepatitis B vaccine at birth to infants whose mothers who did not receive Tdap during pregnancy would be a practical solution, if the aP vaccine were universally available.

But the aP vaccine currently is not available in the United States and many other countries as a standalone vaccine, and the administration of DTaP as a birth dose has been linked with “significant immune interference.” The aP vaccine could have a place in countries where it is available, and there is no maternal immunization program. Otherwise, boosting maternal immunization appears to be the primary approach for now.

Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, is the Sarah H. Sell and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville. She specializes in pediatric infectious diseases. These comments are a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wood et al. (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2363). Dr. Edwards said she had no conflicts of interest.

compared with a group receiving only the hepatitis B vaccine, a randomized clinical trial from Australia has found.

“These results indicate that a birth dose of aP vaccine is immunogenic in newborns and significantly narrows the immunity gap between birth and 14 days after receipt of DTaP at 6 or 8 weeks of age, marking the critical period when infants are most vulnerable to severe pertussis infection,” reported Nicholas Wood, PhD, of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

“Administration of the acellular pertussis vaccine at birth has the potential to reduce severe morbidity from Bordetella pertussis infection in the first 3 months of life, especially for infants of mothers who have not received a pertussis vaccine during pregnancy,” the researchers concluded in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers enrolled 417 infants from Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth between June 2010 and March 2013 and randomized them to receive either the hepatitis B vaccine alone (n = 205) or the hepatitis B vaccine with a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine (n = 212) within the first 5 days after birth. The randomization was stratified for mothers’ receipt of the Tdap before pregnancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth and that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy. There is not currently a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine licensed in the United States.

The study infants then received the hexavalent DTaP-Hib-hep B-polio vaccine and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months.

The primary outcome was detectable levels of IgG antibody to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks old.

Of the 206 infants receiving the pertussis vaccine at birth, 93% had detectable antibodies to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of the 193 infants who received only the hepatitis B shot (P less than .001). Geometric mean concentration for pertussis toxin IgG also was four times higher in infants who received the pertussis vaccine at birth.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups both at birth and at 32 weeks, demonstrating that the pertussis birth dose is safe and tolerable.

“More important, in this study, the prevalence of fever after receipt of the birth dose, which can mistakenly be associated with potential sepsis and result in additional investigations in the neonatal period, was similar in both the group that received the aP vaccine at birth and the control group,” the authors reported.

A remaining question is the potential impact of maternal antibodies on protection from pertussis.

“The presence of maternal pertussis antibodies at birth can negatively affect postprimary responses to pertussis, diphtheria, and diphtheria-related CRM197 conjugate vaccines with a variety of infant immunization schedules and vaccines,” the authors noted. “The clinical significance of reductions in pertussis antibody related to maternal interference will require ongoing clinical evaluation, because there are no accepted serologic correlates of protection.”

The research was funded by a Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wood N et al, JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

compared with a group receiving only the hepatitis B vaccine, a randomized clinical trial from Australia has found.

“These results indicate that a birth dose of aP vaccine is immunogenic in newborns and significantly narrows the immunity gap between birth and 14 days after receipt of DTaP at 6 or 8 weeks of age, marking the critical period when infants are most vulnerable to severe pertussis infection,” reported Nicholas Wood, PhD, of the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases in New South Wales, Australia, and his colleagues.

“Administration of the acellular pertussis vaccine at birth has the potential to reduce severe morbidity from Bordetella pertussis infection in the first 3 months of life, especially for infants of mothers who have not received a pertussis vaccine during pregnancy,” the researchers concluded in JAMA Pediatrics.

The researchers enrolled 417 infants from Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth between June 2010 and March 2013 and randomized them to receive either the hepatitis B vaccine alone (n = 205) or the hepatitis B vaccine with a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine (n = 212) within the first 5 days after birth. The randomization was stratified for mothers’ receipt of the Tdap before pregnancy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth and that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine during each pregnancy. There is not currently a monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine licensed in the United States.

The study infants then received the hexavalent DTaP-Hib-hep B-polio vaccine and the 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 6 months.

The primary outcome was detectable levels of IgG antibody to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks old.

Of the 206 infants receiving the pertussis vaccine at birth, 93% had detectable antibodies to pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of the 193 infants who received only the hepatitis B shot (P less than .001). Geometric mean concentration for pertussis toxin IgG also was four times higher in infants who received the pertussis vaccine at birth.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups both at birth and at 32 weeks, demonstrating that the pertussis birth dose is safe and tolerable.

“More important, in this study, the prevalence of fever after receipt of the birth dose, which can mistakenly be associated with potential sepsis and result in additional investigations in the neonatal period, was similar in both the group that received the aP vaccine at birth and the control group,” the authors reported.

A remaining question is the potential impact of maternal antibodies on protection from pertussis.

“The presence of maternal pertussis antibodies at birth can negatively affect postprimary responses to pertussis, diphtheria, and diphtheria-related CRM197 conjugate vaccines with a variety of infant immunization schedules and vaccines,” the authors noted. “The clinical significance of reductions in pertussis antibody related to maternal interference will require ongoing clinical evaluation, because there are no accepted serologic correlates of protection.”

The research was funded by a Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wood N et al, JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: A monovalent acellular pertussis vaccine dose at birth appears safe, tolerable, and effective.

Major finding: 93% of 212 newborns receiving an acellular pertussis vaccine at birth showed antibodies against pertussis toxin and pertactin at 10 weeks, compared with 51% of 205 newborns without the birth dose.

Study details: The findings are based on a randomized controlled trial involving 417 healthy term newborns in four Australian cities from June 2010 to March 2013.

Disclosures: The research was funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant, and several authors received NHMRC grants. One author also was supported by a Murdoch Children’s Research Institute Career Development Award. GlaxoSmithKline provided the vaccine and conducted the serologic assays. The authors reporting having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wood N et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Sep. 10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2349.

Eat/sleep/console approach almost eliminates morphine for NAS

ATLANTA – In just 7 months, the University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill, dropped the length of stay for neonatal abstinence syndrome from about 11 days to 5 days by moving from scheduled to PRN morphine dosing and abandoning the Finnegan score, according to a report at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The use of morphine fell from 93% of infants transferred to the hospital’s inpatient floors for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) to just 12%, with no downsides for infants or moms.

“Our results have been incredibly encouraging,” said lead investigator and pediatrics resident Thomas Blount, MD. The take-home message is to treat the infant, rather than relying on the Finnegan score.

UNC Children’s, which treats about 50 infants a year for NAS on its inpatient floors, had been using the traditional approach: babies were automatically scheduled for morphine and Finnegan scoring – a withdrawal symptom checklist – every 4 hours, regardless of need. Sometimes infants weren’t even assessed to see if they actually needed morphine before the next dose was given.

“Waking babies up every 4 hours just seemed crazy; of course, they were going to have heightened neurologic signs and symptoms.” Meanwhile, families and providers were frustrated that infants who were otherwise doing well were held for an extra week or more to wean them off morphine, Dr. Blount said at the meeting.

In Nov. 2017, the hospital switched to the eat/sleep/console (ESC) model for NAS on its inpatient floors. The model emphasizes what’s been shown to work in recent years: keeping the infant with the mother; encouraging breast feeding, skin-on-skin contact, and other comfort measures; and supplementing feeds to help with weight gain. Morphine is reserved for when those measures fail and given only with a needs assessment (Hosp Pediatr. 2018 Jan;8(1):1-6).

The hospital ditched Finnegan scoring on its inpatient floors. Nurses were asked instead to check if infants were feeding adequately, sleeping at least an hour between feedings, and able to be consoled within 10 minutes when upset. If the infants met all three of those ESC criteria, providers moved on. They left the baby swaddled, relied on ambient white noise of ocean waves, and checked back on them later. “They didn’t mess with them,” Dr. Blount said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Finnegan scoring “was causing so much anxiety. Staff and families became hypervigilant,” set off by every little twitch and yawn the baby made. It was a good thing when it was abandoned; everyone relaxed, he said.

The changes made a huge difference. The average number of morphine doses dropped from 39 per infant to just 7 total doses among 23 infants in the first 7 months of the ESC initiative. Currently, morphine is used in only about 1 of 10 cases. “We estimate that we’ve given over 900 fewer doses” since ESC was put in place, Dr. Blount said.

There’s been no change in 30-day readmission rates – just one since the changes were made, for bronchiolitis – and no change in weight loss among infants with NAS. Babies are meeting all the ESC criteria to thrive.

“We had a lot of pushback initially, mostly from nursing staff and residents wondering how this was going to work. It quickly went away,” Dr. Blount said.

His team is now considering rolling ESC out to the newborn nursery and NICU.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Blount didn’t have any disclosures.

ATLANTA – In just 7 months, the University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill, dropped the length of stay for neonatal abstinence syndrome from about 11 days to 5 days by moving from scheduled to PRN morphine dosing and abandoning the Finnegan score, according to a report at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The use of morphine fell from 93% of infants transferred to the hospital’s inpatient floors for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) to just 12%, with no downsides for infants or moms.

“Our results have been incredibly encouraging,” said lead investigator and pediatrics resident Thomas Blount, MD. The take-home message is to treat the infant, rather than relying on the Finnegan score.

UNC Children’s, which treats about 50 infants a year for NAS on its inpatient floors, had been using the traditional approach: babies were automatically scheduled for morphine and Finnegan scoring – a withdrawal symptom checklist – every 4 hours, regardless of need. Sometimes infants weren’t even assessed to see if they actually needed morphine before the next dose was given.

“Waking babies up every 4 hours just seemed crazy; of course, they were going to have heightened neurologic signs and symptoms.” Meanwhile, families and providers were frustrated that infants who were otherwise doing well were held for an extra week or more to wean them off morphine, Dr. Blount said at the meeting.

In Nov. 2017, the hospital switched to the eat/sleep/console (ESC) model for NAS on its inpatient floors. The model emphasizes what’s been shown to work in recent years: keeping the infant with the mother; encouraging breast feeding, skin-on-skin contact, and other comfort measures; and supplementing feeds to help with weight gain. Morphine is reserved for when those measures fail and given only with a needs assessment (Hosp Pediatr. 2018 Jan;8(1):1-6).

The hospital ditched Finnegan scoring on its inpatient floors. Nurses were asked instead to check if infants were feeding adequately, sleeping at least an hour between feedings, and able to be consoled within 10 minutes when upset. If the infants met all three of those ESC criteria, providers moved on. They left the baby swaddled, relied on ambient white noise of ocean waves, and checked back on them later. “They didn’t mess with them,” Dr. Blount said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Finnegan scoring “was causing so much anxiety. Staff and families became hypervigilant,” set off by every little twitch and yawn the baby made. It was a good thing when it was abandoned; everyone relaxed, he said.

The changes made a huge difference. The average number of morphine doses dropped from 39 per infant to just 7 total doses among 23 infants in the first 7 months of the ESC initiative. Currently, morphine is used in only about 1 of 10 cases. “We estimate that we’ve given over 900 fewer doses” since ESC was put in place, Dr. Blount said.

There’s been no change in 30-day readmission rates – just one since the changes were made, for bronchiolitis – and no change in weight loss among infants with NAS. Babies are meeting all the ESC criteria to thrive.

“We had a lot of pushback initially, mostly from nursing staff and residents wondering how this was going to work. It quickly went away,” Dr. Blount said.

His team is now considering rolling ESC out to the newborn nursery and NICU.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Blount didn’t have any disclosures.

ATLANTA – In just 7 months, the University of North Carolina Children’s Hospital, Chapel Hill, dropped the length of stay for neonatal abstinence syndrome from about 11 days to 5 days by moving from scheduled to PRN morphine dosing and abandoning the Finnegan score, according to a report at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The use of morphine fell from 93% of infants transferred to the hospital’s inpatient floors for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) to just 12%, with no downsides for infants or moms.

“Our results have been incredibly encouraging,” said lead investigator and pediatrics resident Thomas Blount, MD. The take-home message is to treat the infant, rather than relying on the Finnegan score.

UNC Children’s, which treats about 50 infants a year for NAS on its inpatient floors, had been using the traditional approach: babies were automatically scheduled for morphine and Finnegan scoring – a withdrawal symptom checklist – every 4 hours, regardless of need. Sometimes infants weren’t even assessed to see if they actually needed morphine before the next dose was given.

“Waking babies up every 4 hours just seemed crazy; of course, they were going to have heightened neurologic signs and symptoms.” Meanwhile, families and providers were frustrated that infants who were otherwise doing well were held for an extra week or more to wean them off morphine, Dr. Blount said at the meeting.

In Nov. 2017, the hospital switched to the eat/sleep/console (ESC) model for NAS on its inpatient floors. The model emphasizes what’s been shown to work in recent years: keeping the infant with the mother; encouraging breast feeding, skin-on-skin contact, and other comfort measures; and supplementing feeds to help with weight gain. Morphine is reserved for when those measures fail and given only with a needs assessment (Hosp Pediatr. 2018 Jan;8(1):1-6).

The hospital ditched Finnegan scoring on its inpatient floors. Nurses were asked instead to check if infants were feeding adequately, sleeping at least an hour between feedings, and able to be consoled within 10 minutes when upset. If the infants met all three of those ESC criteria, providers moved on. They left the baby swaddled, relied on ambient white noise of ocean waves, and checked back on them later. “They didn’t mess with them,” Dr. Blount said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Finnegan scoring “was causing so much anxiety. Staff and families became hypervigilant,” set off by every little twitch and yawn the baby made. It was a good thing when it was abandoned; everyone relaxed, he said.

The changes made a huge difference. The average number of morphine doses dropped from 39 per infant to just 7 total doses among 23 infants in the first 7 months of the ESC initiative. Currently, morphine is used in only about 1 of 10 cases. “We estimate that we’ve given over 900 fewer doses” since ESC was put in place, Dr. Blount said.