User login

Prenatal, postnatal neuroimaging IDs most Zika-related brain injuries

Prenatal ultrasound can identify most abnormalities in fetuses exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy, and neuroimaging after birth can detect infant exposure in cases that appeared normal on prenatal ultrasound, according to research published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Absence of prolonged maternal viremia did not have predictive associations with normal fetal or neonatal brain imaging,” Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, from the division of fetal and transitional medicine at Children’s National Health System, in Washington, and her colleagues wrote. “Postnatal imaging can detect changes not seen on fetal imaging, supporting the current CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] recommendation for postnatal cranial [ultrasound].”

Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort analysis of 82 pregnant women from Colombia and the United States who had clinical evidence of probable exposure to the Zika virus through travel (U.S. cases, 2 patients), physician referral, or community cases during June 2016-June 2017. Pregnant women underwent fetal MRI or ultrasound during the second or third trimesters between 4 weeks and 10 weeks after symptom onset, with infants undergoing brain MRI and cranial ultrasound after birth.

Of those 82 pregnancies, there were 80 live births, 1 case of termination because of severe fetal brain abnormalities, and 1 near-term fetal death of unknown cause. There was one death 3 days after birth and one instance of neurosurgical intervention from encephalocele. The researchers found 3 of 82 cases (4%) displayed fetal abnormalities from MRI, which consisted of 2 cases of heterotopias and malformations in cortical development and 1 case with parietal encephalocele, Chiari II malformation, and microcephaly. One infant had a normal ultrasound despite abnormalities displayed on fetal MRI.

After birth, of the 79 infants with normal ultrasound results, 53 infants underwent a postnatal brain MRI and Dr. Mulkey and her associates found 7 cases with mild abnormalities (13%). There were 57 infants who underwent cranial ultrasound, which yielded 21 cases of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, choroid plexus cysts, germinolytic/subependymal cysts, and/or calcification; these were poorly characterized by MRI.

“Normal fetal imaging had predictive associations with normal postnatal imaging or mild postnatal imaging findings unlikely to be of significant clinical consequence,” they said.

Nonetheless, “there is a need for long-term follow-up to assess the neurodevelopmental significance of these early neuroimaging findings, both normal and abnormal; such studies are in progress,” Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues said.

The researchers noted the timing of maternal infections and symptoms as well as the Zika testing, ultrasound, and MRI performance, technique during fetal MRI, and incomplete prenatal testing in the cohort as limitations in the study.

This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr. Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

While the study by Mulkey et al. adds to the body of evidence of prenatal and postnatal brain abnormalities, there are still many unanswered questions about the Zika virus and how to handle its unique diagnostic and clinical challenges, Margaret A. Honein, PhD, MPH, and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial.

For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that infants with possible Zika exposure should receive an ophthalmologic and ultrasonographic examination at 1 month, and if the hearing test used otoacoustic emissions methods only, an automated auditory brainstem response test should be administered. While Mulkey et al. examined brain abnormalities in utero and in infants, it is not clear whether all CDC guidelines were followed in these cases.

In addition, because there is no reliable way to determine whether infants acquired Zika virus through the mother or through vertical transmission, assessing the proportion of congenitally infected infants or vertical-transmission infected infants who have neurodevelopmental disabilities and defects is not possible, they said. More longitudinal studies are needed to study the effects of the Zika virus and to prepare for the next outbreak.

“Zika was affecting pregnant women and their infants years before its teratogenic effect was recognized, and Zika will remain a serious risk to pregnant women and their infants until we have a safe vaccine that can fully prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” they said. “Until then, ongoing public health efforts are essential to protect mothers and babies from this threat and ensure all disabilities associated with Zika virus infection are promptly identified, so that timely interventions can be provided.”

Dr. Honein is from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Jamieson is from the department of gynecology & obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Mulkey et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4164). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

While the study by Mulkey et al. adds to the body of evidence of prenatal and postnatal brain abnormalities, there are still many unanswered questions about the Zika virus and how to handle its unique diagnostic and clinical challenges, Margaret A. Honein, PhD, MPH, and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial.

For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that infants with possible Zika exposure should receive an ophthalmologic and ultrasonographic examination at 1 month, and if the hearing test used otoacoustic emissions methods only, an automated auditory brainstem response test should be administered. While Mulkey et al. examined brain abnormalities in utero and in infants, it is not clear whether all CDC guidelines were followed in these cases.

In addition, because there is no reliable way to determine whether infants acquired Zika virus through the mother or through vertical transmission, assessing the proportion of congenitally infected infants or vertical-transmission infected infants who have neurodevelopmental disabilities and defects is not possible, they said. More longitudinal studies are needed to study the effects of the Zika virus and to prepare for the next outbreak.

“Zika was affecting pregnant women and their infants years before its teratogenic effect was recognized, and Zika will remain a serious risk to pregnant women and their infants until we have a safe vaccine that can fully prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” they said. “Until then, ongoing public health efforts are essential to protect mothers and babies from this threat and ensure all disabilities associated with Zika virus infection are promptly identified, so that timely interventions can be provided.”

Dr. Honein is from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Jamieson is from the department of gynecology & obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Mulkey et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4164). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

While the study by Mulkey et al. adds to the body of evidence of prenatal and postnatal brain abnormalities, there are still many unanswered questions about the Zika virus and how to handle its unique diagnostic and clinical challenges, Margaret A. Honein, PhD, MPH, and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, wrote in a related editorial.

For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations state that infants with possible Zika exposure should receive an ophthalmologic and ultrasonographic examination at 1 month, and if the hearing test used otoacoustic emissions methods only, an automated auditory brainstem response test should be administered. While Mulkey et al. examined brain abnormalities in utero and in infants, it is not clear whether all CDC guidelines were followed in these cases.

In addition, because there is no reliable way to determine whether infants acquired Zika virus through the mother or through vertical transmission, assessing the proportion of congenitally infected infants or vertical-transmission infected infants who have neurodevelopmental disabilities and defects is not possible, they said. More longitudinal studies are needed to study the effects of the Zika virus and to prepare for the next outbreak.

“Zika was affecting pregnant women and their infants years before its teratogenic effect was recognized, and Zika will remain a serious risk to pregnant women and their infants until we have a safe vaccine that can fully prevent Zika virus infection during pregnancy,” they said. “Until then, ongoing public health efforts are essential to protect mothers and babies from this threat and ensure all disabilities associated with Zika virus infection are promptly identified, so that timely interventions can be provided.”

Dr. Honein is from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Dr. Jamieson is from the department of gynecology & obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Mulkey et al. (JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4164). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Prenatal ultrasound can identify most abnormalities in fetuses exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy, and neuroimaging after birth can detect infant exposure in cases that appeared normal on prenatal ultrasound, according to research published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Absence of prolonged maternal viremia did not have predictive associations with normal fetal or neonatal brain imaging,” Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, from the division of fetal and transitional medicine at Children’s National Health System, in Washington, and her colleagues wrote. “Postnatal imaging can detect changes not seen on fetal imaging, supporting the current CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] recommendation for postnatal cranial [ultrasound].”

Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort analysis of 82 pregnant women from Colombia and the United States who had clinical evidence of probable exposure to the Zika virus through travel (U.S. cases, 2 patients), physician referral, or community cases during June 2016-June 2017. Pregnant women underwent fetal MRI or ultrasound during the second or third trimesters between 4 weeks and 10 weeks after symptom onset, with infants undergoing brain MRI and cranial ultrasound after birth.

Of those 82 pregnancies, there were 80 live births, 1 case of termination because of severe fetal brain abnormalities, and 1 near-term fetal death of unknown cause. There was one death 3 days after birth and one instance of neurosurgical intervention from encephalocele. The researchers found 3 of 82 cases (4%) displayed fetal abnormalities from MRI, which consisted of 2 cases of heterotopias and malformations in cortical development and 1 case with parietal encephalocele, Chiari II malformation, and microcephaly. One infant had a normal ultrasound despite abnormalities displayed on fetal MRI.

After birth, of the 79 infants with normal ultrasound results, 53 infants underwent a postnatal brain MRI and Dr. Mulkey and her associates found 7 cases with mild abnormalities (13%). There were 57 infants who underwent cranial ultrasound, which yielded 21 cases of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, choroid plexus cysts, germinolytic/subependymal cysts, and/or calcification; these were poorly characterized by MRI.

“Normal fetal imaging had predictive associations with normal postnatal imaging or mild postnatal imaging findings unlikely to be of significant clinical consequence,” they said.

Nonetheless, “there is a need for long-term follow-up to assess the neurodevelopmental significance of these early neuroimaging findings, both normal and abnormal; such studies are in progress,” Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues said.

The researchers noted the timing of maternal infections and symptoms as well as the Zika testing, ultrasound, and MRI performance, technique during fetal MRI, and incomplete prenatal testing in the cohort as limitations in the study.

This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr. Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

Prenatal ultrasound can identify most abnormalities in fetuses exposed to Zika virus during pregnancy, and neuroimaging after birth can detect infant exposure in cases that appeared normal on prenatal ultrasound, according to research published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Absence of prolonged maternal viremia did not have predictive associations with normal fetal or neonatal brain imaging,” Sarah B. Mulkey, MD, PhD, from the division of fetal and transitional medicine at Children’s National Health System, in Washington, and her colleagues wrote. “Postnatal imaging can detect changes not seen on fetal imaging, supporting the current CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] recommendation for postnatal cranial [ultrasound].”

Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort analysis of 82 pregnant women from Colombia and the United States who had clinical evidence of probable exposure to the Zika virus through travel (U.S. cases, 2 patients), physician referral, or community cases during June 2016-June 2017. Pregnant women underwent fetal MRI or ultrasound during the second or third trimesters between 4 weeks and 10 weeks after symptom onset, with infants undergoing brain MRI and cranial ultrasound after birth.

Of those 82 pregnancies, there were 80 live births, 1 case of termination because of severe fetal brain abnormalities, and 1 near-term fetal death of unknown cause. There was one death 3 days after birth and one instance of neurosurgical intervention from encephalocele. The researchers found 3 of 82 cases (4%) displayed fetal abnormalities from MRI, which consisted of 2 cases of heterotopias and malformations in cortical development and 1 case with parietal encephalocele, Chiari II malformation, and microcephaly. One infant had a normal ultrasound despite abnormalities displayed on fetal MRI.

After birth, of the 79 infants with normal ultrasound results, 53 infants underwent a postnatal brain MRI and Dr. Mulkey and her associates found 7 cases with mild abnormalities (13%). There were 57 infants who underwent cranial ultrasound, which yielded 21 cases of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, choroid plexus cysts, germinolytic/subependymal cysts, and/or calcification; these were poorly characterized by MRI.

“Normal fetal imaging had predictive associations with normal postnatal imaging or mild postnatal imaging findings unlikely to be of significant clinical consequence,” they said.

Nonetheless, “there is a need for long-term follow-up to assess the neurodevelopmental significance of these early neuroimaging findings, both normal and abnormal; such studies are in progress,” Dr. Mulkey and her colleagues said.

The researchers noted the timing of maternal infections and symptoms as well as the Zika testing, ultrasound, and MRI performance, technique during fetal MRI, and incomplete prenatal testing in the cohort as limitations in the study.

This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr. Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 82 pregnant women, prenatal neuroimaging identified fetal abnormalities in 3 cases, while postnatal neuroimaging in 53 of the remaining 79 cases yielded an additional 7 cases with mild abnormalities.

Study details: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 82 pregnant women with clinical evidence of probable Zika infection in Colombia and the United States.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by Children’s National Health System and by a philanthropic gift from the Ikaria Healthcare Fund. Dr Mulkey received research support from the Thrasher Research Fund and is supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Mulkey SB et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov. 26; doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4138.

FDA approves congenital CMV diagnostic test

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

, a new test to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) in newborns less than 21 days of age.

The Alethia CMV Assay Test System detects CMV DNA from a saliva swab. Results from the test should be used only in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests and clinical information, according to an FDA statement.

“This test for detecting the virus, when used in conjunction with the results of other diagnostic tests, may help health care providers more quickly identify the virus in newborns,” said Timothy Stenzel, PhD, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

In a prospective clinical study, 1,472 saliva samples out of 1,475 samples collected from newborns were correctly identified by the device as negative for the presence of CMV DNA. Three samples were incorrectly identified as positive when they were negative. Five collected saliva specimens were correctly identified as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

In a testing of 34 samples of archived specimens from babies known to be infected with CMV, all of the archived specimens were correctly identified by the device as positive for the presence of CMV DNA.

The FDA reviewed the Alethia CMV Assay Test System through a regulatory pathway established for novel, low- to moderate-risk devices. Along with this authorization, the FDA is establishing criteria, called special controls, which determine the requirements for demonstrating accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of tests intended to be used as an aid in the diagnosis of congenital CMV infection.

With this new regulatory classification, subsequent devices of the same type with the same intended use may go through the FDA’s 510(k) process, whereby devices can obtain marketing authorization by demonstrating substantial equivalence to a previously approved device.

The FDA granted marketing authorization of the Alethia CMV Assay Test System to Meridian Bioscience.

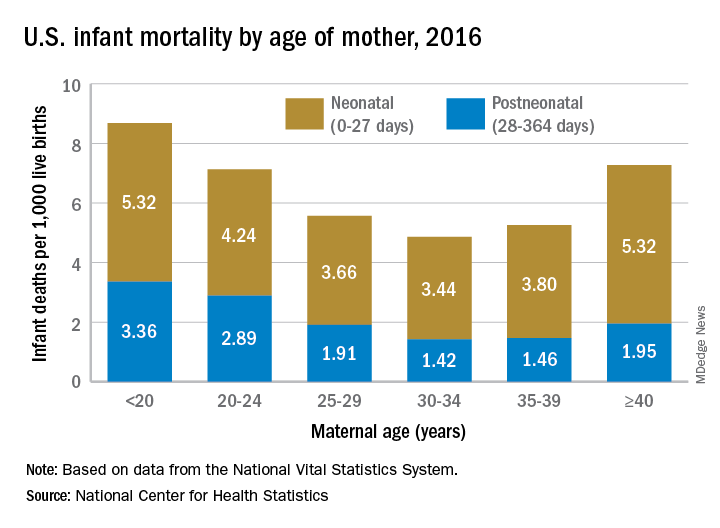

Infant mortality generally unchanged in 2016

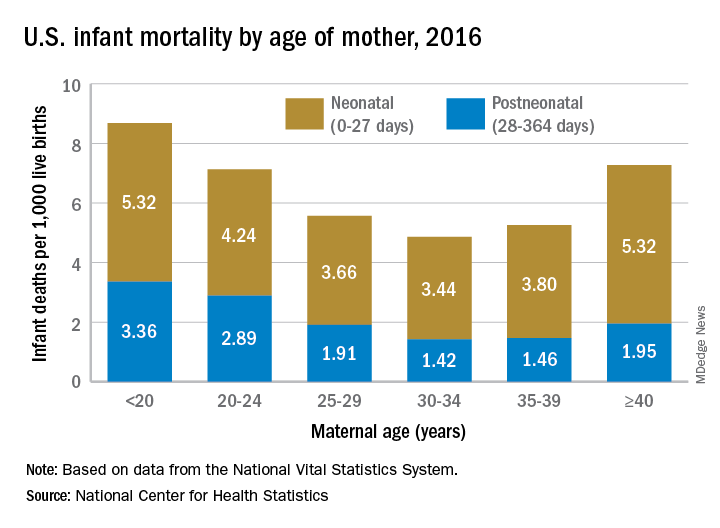

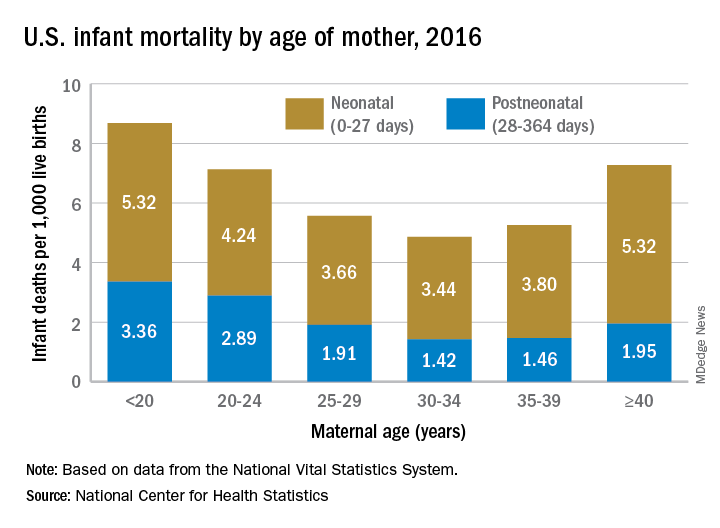

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

Infant mortality in the United Sates dropped very slightly from 2015 to 2016 and has not changed significantly since 2011, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Overall infant mortality was 5.87 per 1,000 live births in 2016, which was not significantly less than the 2015 rate of 5.90 per 1,000 or the rate of 6.07 per 1,000 recorded in 2011, the NCHS said in a recent Data Brief. The rate for 2016 works out to 3.88 per 1,000 for the neonatal period (0-27 days) and 1.99 per 1,000 during the postneonatal period (28-364 days).

The rate was lowest for mothers aged 30-34 years (4.86 per 1,000) and highest for those under 20 years (8.69). All overall rates by maternal age were significantly different from each other, except for those of mothers aged 20-24 years (7.13) and those aged 40 years and over (7.27). Neonatal mortality was highest for the under-20 group and the 40-and-over group at 5.32 per 1,000, with the difference between them coming during the postneonatal period: 3.36 for those under 20 and 1.95 for the 40-and-overs, the NCHS investigators reported based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The leading cause of death during the neonatal period in 2016 was low birth weight at 98 per 1,000 live births, with congenital malformations second at 86 per 1,000. The leading cause of death in the postneonatal period was congenital malformations at 36 per 1,000, followed by sudden infant death syndrome (35 per 1,000), unintentional injuries (27 per 1,000), diseases of the circulatory system (9 per 1,000), and homicide (6 per 1,000), they added.

Experts advise risk stratification for newborn early-onset sepsis

according to a pair of clinical reports published in Pediatrics.

Early-onset sepsis usually begins during labor in term infants, but in preterm infants, “the pathogenesis of preterm EOS likely begins before the onset of labor in many cases of preterm labor and/or PROM [premature rupture of membranes],” wrote Karen M. Puopolo, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues.

In the report on preterm infants, the researchers noted that EOS risk assessment using gestational age can be useful for term infants, but not for preterm infants. Instead, they advised categorizing preterm infants as low risk based on birth circumstances. Low-risk preterm infants were defined as those born by cesarean delivery because of maternal noninfectious illness or placental insufficiency in the absence of labor, attempts to induce labor, or rupture of membranes before delivery. Consider the risk/benefit balance of performing an EOS laboratory evaluation and empirical antibiotics, depending on the neonate’s clinical condition, the researchers said.

Preterm infants at high risk for EOS are those born preterm because of maternal cervical incompetence, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, clinical concerns for intra-amniotic infection, or acute onset of “unexplained nonreassuring fetal status,” Dr. Puopolo and her associates said. These infants should be managed with a blood culture and empirical antibiotics.

“The combination of ampicillin and gentamicin is the most appropriate empirical antibiotic regimen for infants at risk for EOS,” they noted. “Empirical administration of additional broad-spectrum antibiotics may be indicated in preterm infants who are severely ill and at a high risk for EOS, particularly after prolonged antepartum maternal antibiotic treatment,” they said. Antibiotics should be discontinued by 36-48 hours of incubation unless the infant shows signs of site-specific infection.

In the second report, again with Dr. Puopolo as the primary author, management of EOS was addressed for full-term infants, defined as those born at 35 weeks’ gestation or later.

Infants born at 35 weeks’ gestation or later can be stratified for EOS risk based on algorithms for intrapartum risk factors as well as risk assessments based on these risk factors and infant examinations, the researchers said.

There are a variety of acceptable approaches to risk stratification: categorical algorithms with threshold values for intrapartum risk factors; multivariate risk assessment based on both intrapartum risk factors (such as maternal chorioamnionitis, group B streptococcus colonization, adequacy of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and duration of ROM); and serial infant examination to detect clinical signs of illness after birth, Dr. Puopolo and her associates wrote.

They recommended that birth centers choose which type of EOS risk assessment to use and tailor it to their own situation. Once local guidelines are developed, ongoing surveillance is suggested.

The same recommendations apply to term infants as preterm infants regarding first-choice use of ampicillin and gentamicin when necessary, to be discontinued when blood cultures are sterile at 36-48 hours of incubation in the absence of site-specific infection, they said.

The reports do “not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate,” Dr. Puopolo and her associates noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose, and there was no external funding.

SOURCE: Puopolo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2896; Puopolo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2894.

according to a pair of clinical reports published in Pediatrics.

Early-onset sepsis usually begins during labor in term infants, but in preterm infants, “the pathogenesis of preterm EOS likely begins before the onset of labor in many cases of preterm labor and/or PROM [premature rupture of membranes],” wrote Karen M. Puopolo, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues.

In the report on preterm infants, the researchers noted that EOS risk assessment using gestational age can be useful for term infants, but not for preterm infants. Instead, they advised categorizing preterm infants as low risk based on birth circumstances. Low-risk preterm infants were defined as those born by cesarean delivery because of maternal noninfectious illness or placental insufficiency in the absence of labor, attempts to induce labor, or rupture of membranes before delivery. Consider the risk/benefit balance of performing an EOS laboratory evaluation and empirical antibiotics, depending on the neonate’s clinical condition, the researchers said.

Preterm infants at high risk for EOS are those born preterm because of maternal cervical incompetence, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, clinical concerns for intra-amniotic infection, or acute onset of “unexplained nonreassuring fetal status,” Dr. Puopolo and her associates said. These infants should be managed with a blood culture and empirical antibiotics.

“The combination of ampicillin and gentamicin is the most appropriate empirical antibiotic regimen for infants at risk for EOS,” they noted. “Empirical administration of additional broad-spectrum antibiotics may be indicated in preterm infants who are severely ill and at a high risk for EOS, particularly after prolonged antepartum maternal antibiotic treatment,” they said. Antibiotics should be discontinued by 36-48 hours of incubation unless the infant shows signs of site-specific infection.

In the second report, again with Dr. Puopolo as the primary author, management of EOS was addressed for full-term infants, defined as those born at 35 weeks’ gestation or later.

Infants born at 35 weeks’ gestation or later can be stratified for EOS risk based on algorithms for intrapartum risk factors as well as risk assessments based on these risk factors and infant examinations, the researchers said.

There are a variety of acceptable approaches to risk stratification: categorical algorithms with threshold values for intrapartum risk factors; multivariate risk assessment based on both intrapartum risk factors (such as maternal chorioamnionitis, group B streptococcus colonization, adequacy of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and duration of ROM); and serial infant examination to detect clinical signs of illness after birth, Dr. Puopolo and her associates wrote.

They recommended that birth centers choose which type of EOS risk assessment to use and tailor it to their own situation. Once local guidelines are developed, ongoing surveillance is suggested.

The same recommendations apply to term infants as preterm infants regarding first-choice use of ampicillin and gentamicin when necessary, to be discontinued when blood cultures are sterile at 36-48 hours of incubation in the absence of site-specific infection, they said.

The reports do “not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate,” Dr. Puopolo and her associates noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose, and there was no external funding.

SOURCE: Puopolo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2896; Puopolo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2894.

according to a pair of clinical reports published in Pediatrics.

Early-onset sepsis usually begins during labor in term infants, but in preterm infants, “the pathogenesis of preterm EOS likely begins before the onset of labor in many cases of preterm labor and/or PROM [premature rupture of membranes],” wrote Karen M. Puopolo, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues.

In the report on preterm infants, the researchers noted that EOS risk assessment using gestational age can be useful for term infants, but not for preterm infants. Instead, they advised categorizing preterm infants as low risk based on birth circumstances. Low-risk preterm infants were defined as those born by cesarean delivery because of maternal noninfectious illness or placental insufficiency in the absence of labor, attempts to induce labor, or rupture of membranes before delivery. Consider the risk/benefit balance of performing an EOS laboratory evaluation and empirical antibiotics, depending on the neonate’s clinical condition, the researchers said.

Preterm infants at high risk for EOS are those born preterm because of maternal cervical incompetence, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, clinical concerns for intra-amniotic infection, or acute onset of “unexplained nonreassuring fetal status,” Dr. Puopolo and her associates said. These infants should be managed with a blood culture and empirical antibiotics.

“The combination of ampicillin and gentamicin is the most appropriate empirical antibiotic regimen for infants at risk for EOS,” they noted. “Empirical administration of additional broad-spectrum antibiotics may be indicated in preterm infants who are severely ill and at a high risk for EOS, particularly after prolonged antepartum maternal antibiotic treatment,” they said. Antibiotics should be discontinued by 36-48 hours of incubation unless the infant shows signs of site-specific infection.

In the second report, again with Dr. Puopolo as the primary author, management of EOS was addressed for full-term infants, defined as those born at 35 weeks’ gestation or later.

Infants born at 35 weeks’ gestation or later can be stratified for EOS risk based on algorithms for intrapartum risk factors as well as risk assessments based on these risk factors and infant examinations, the researchers said.

There are a variety of acceptable approaches to risk stratification: categorical algorithms with threshold values for intrapartum risk factors; multivariate risk assessment based on both intrapartum risk factors (such as maternal chorioamnionitis, group B streptococcus colonization, adequacy of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, and duration of ROM); and serial infant examination to detect clinical signs of illness after birth, Dr. Puopolo and her associates wrote.

They recommended that birth centers choose which type of EOS risk assessment to use and tailor it to their own situation. Once local guidelines are developed, ongoing surveillance is suggested.

The same recommendations apply to term infants as preterm infants regarding first-choice use of ampicillin and gentamicin when necessary, to be discontinued when blood cultures are sterile at 36-48 hours of incubation in the absence of site-specific infection, they said.

The reports do “not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate,” Dr. Puopolo and her associates noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose, and there was no external funding.

SOURCE: Puopolo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2896; Puopolo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2894.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Levonorgestrel implant right after delivery does not affect breastfeeding, infant growth

Researchers found no significant differences in infant growth, changes in breastfeeding initiation or breastfeeding continuation at 3-month and 6-month follow-up among women who received a levonorgestrel contraception implant very soon after delivery, compared with women who waited to receive the implant.

“These findings are consistent with the preponderance of literature supporting the hypothesis that progestin-containing contraceptives do not compromise a woman’s ability to initiate or sustain breastfeeding and do not adversely affect infant growth,” Sarah Averbach, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote in their study published in Contraception.

Dr. Averbach and her colleagues randomized 96 women to receive a two-rod levonorgestrel (LNG)–releasing subdermal contraceptive implant within 5 days of delivery (mean time, 36 hours post delivery) and 87 women to delay the implant to between 6 and 8 weeks at a postpartum follow-up visit (mean time, 68 days). The women were a minimum of 18 years old with a recent vaginal or cesarean section delivery at a Ugandan hospital; 55% of the women had at least three children, and 73% said they had prior experience breastfeeding. The researchers then examined infant weight change and infant head circumference change at 6 months from birth, time to lactogenesis, and whether mothers continued to breastfeed at 3 months and 6 months after birth.

Infant weight was similar in the immediate-implant group (4,632 g), compared with the delayed-implant group (4,407 g; P = .26); infant head circumference was similar between both groups (9.3 cm vs. 9.5 cm; P = .70) at 6 months as well. The time to lactogenesis was not significantly different in the immediate-implant (65 hours) and delayed-implant (63 hours; P = .84) groups. At 3 months, 74% of immediate-implant participants and 71% of delayed-implant participants said they were breastfeeding exclusively (P = .74); at 6 months, 48% of immediate implant participants and 52% of delayed implant participants reported exclusive breastfeeding (P equals .58).

Limitations of the study included follow-up to only 6 months and selection of participants with previous breastfeeding experience. Researchers also noted better measurements of infant and maternal breast milk intake also could be used and limit generalization of the results.

This study was funded by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Dr. Averbach is supported by an award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Averbach S et al. Contraception. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.10.008.

Researchers found no significant differences in infant growth, changes in breastfeeding initiation or breastfeeding continuation at 3-month and 6-month follow-up among women who received a levonorgestrel contraception implant very soon after delivery, compared with women who waited to receive the implant.

“These findings are consistent with the preponderance of literature supporting the hypothesis that progestin-containing contraceptives do not compromise a woman’s ability to initiate or sustain breastfeeding and do not adversely affect infant growth,” Sarah Averbach, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote in their study published in Contraception.

Dr. Averbach and her colleagues randomized 96 women to receive a two-rod levonorgestrel (LNG)–releasing subdermal contraceptive implant within 5 days of delivery (mean time, 36 hours post delivery) and 87 women to delay the implant to between 6 and 8 weeks at a postpartum follow-up visit (mean time, 68 days). The women were a minimum of 18 years old with a recent vaginal or cesarean section delivery at a Ugandan hospital; 55% of the women had at least three children, and 73% said they had prior experience breastfeeding. The researchers then examined infant weight change and infant head circumference change at 6 months from birth, time to lactogenesis, and whether mothers continued to breastfeed at 3 months and 6 months after birth.

Infant weight was similar in the immediate-implant group (4,632 g), compared with the delayed-implant group (4,407 g; P = .26); infant head circumference was similar between both groups (9.3 cm vs. 9.5 cm; P = .70) at 6 months as well. The time to lactogenesis was not significantly different in the immediate-implant (65 hours) and delayed-implant (63 hours; P = .84) groups. At 3 months, 74% of immediate-implant participants and 71% of delayed-implant participants said they were breastfeeding exclusively (P = .74); at 6 months, 48% of immediate implant participants and 52% of delayed implant participants reported exclusive breastfeeding (P equals .58).

Limitations of the study included follow-up to only 6 months and selection of participants with previous breastfeeding experience. Researchers also noted better measurements of infant and maternal breast milk intake also could be used and limit generalization of the results.

This study was funded by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Dr. Averbach is supported by an award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Averbach S et al. Contraception. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.10.008.

Researchers found no significant differences in infant growth, changes in breastfeeding initiation or breastfeeding continuation at 3-month and 6-month follow-up among women who received a levonorgestrel contraception implant very soon after delivery, compared with women who waited to receive the implant.

“These findings are consistent with the preponderance of literature supporting the hypothesis that progestin-containing contraceptives do not compromise a woman’s ability to initiate or sustain breastfeeding and do not adversely affect infant growth,” Sarah Averbach, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues wrote in their study published in Contraception.

Dr. Averbach and her colleagues randomized 96 women to receive a two-rod levonorgestrel (LNG)–releasing subdermal contraceptive implant within 5 days of delivery (mean time, 36 hours post delivery) and 87 women to delay the implant to between 6 and 8 weeks at a postpartum follow-up visit (mean time, 68 days). The women were a minimum of 18 years old with a recent vaginal or cesarean section delivery at a Ugandan hospital; 55% of the women had at least three children, and 73% said they had prior experience breastfeeding. The researchers then examined infant weight change and infant head circumference change at 6 months from birth, time to lactogenesis, and whether mothers continued to breastfeed at 3 months and 6 months after birth.

Infant weight was similar in the immediate-implant group (4,632 g), compared with the delayed-implant group (4,407 g; P = .26); infant head circumference was similar between both groups (9.3 cm vs. 9.5 cm; P = .70) at 6 months as well. The time to lactogenesis was not significantly different in the immediate-implant (65 hours) and delayed-implant (63 hours; P = .84) groups. At 3 months, 74% of immediate-implant participants and 71% of delayed-implant participants said they were breastfeeding exclusively (P = .74); at 6 months, 48% of immediate implant participants and 52% of delayed implant participants reported exclusive breastfeeding (P equals .58).

Limitations of the study included follow-up to only 6 months and selection of participants with previous breastfeeding experience. Researchers also noted better measurements of infant and maternal breast milk intake also could be used and limit generalization of the results.

This study was funded by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Dr. Averbach is supported by an award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Averbach S et al. Contraception. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.10.008.

FROM CONTRACEPTION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Infant weight was similar in the immediate-implant group (4,632 g), compared with the delayed-implant group (4,407 g; P = .26); infant head circumference was similar between both groups (9.3 cm vs. 9.5 cm; P = .70) at 6 months as well.

Study details: A randomized trial of 96 women in Uganda who received a contraceptive implant less than 5 days after delivery and 86 women who received the implant between 6 and 8 weeks post partum.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Dr. Averbach is supported by an award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Averbach S et al. Contraception. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.10.008.

Nearly half of infants don’t sleep through the night at 1 year

Just over half of infants get 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep at 12 months of age, an analysis of findings from a longitudinal birth cohort study showed.

It also found that whether an infant sleeps through night has no significant associated with any variations in mental or psychomotor development.

However, the rate of breastfeeding was significantly higher among infants who did not sleep through the night, investigators said in their report on the analysis, published in Pediatrics.

Being informed about the normal development of the sleep-wake cycle could be reassuring for parents, according to the authors, who said that new mothers tend to be “greatly surprised” by the sleep disturbance and exhaustion they experience.

“Keeping in mind the wide variability in the age when an infant starts to sleep through the night, expectations for early sleep consolidation could be moderated,” said Marie-Hélène Pennestri, PhD, of the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University, Montreal, and her coauthors.

Dr. Pennestri and colleagues reported on 388 mother-infant dyads in a longitudinal birth cohort study called Maternal Adversity, Vulnerability, and Neurodevelopment (MAVAN). Pregnant mothers were recruited from obstetric clinics in Canada. When their infants reached the age of 6 and 12 months, the mothers responded to questionnaires about sleep habits.

At 6 months, 62.4% of infants attained at least 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep, mothers reported, while 43.0% had reached 8 hours, the mothers reported. By 12 months of age, 72.1% of the infants attained 6 hours, and 56.6% attained 8 hours.

There were no associations between sleeping through the night and concurrent mental or psychomotor development, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II at both 6 or 12 months of age, with P values greater than 0.05, investigators reported.

A similar lack of association between uninterrupted sleep and development or maternal mood was seen in a follow-up measurement at 36 months of age.

Sleeping through the night was likewise not associated with maternal mood, assessed using a depression scale with items that reflected symptom frequency in the previous week. “This is noteworthy because maternal sleep deprivation is often invoked to support the introduction of early behavioral interventions,” investigators said in a discussion of the results.

By contrast, sleeping through the night was linked to lower rates of breastfeeding as reported by mothers on retrospective questionnaires administered at both 6 and 12 months. At 12 months of age, 22.1% of infants sleeping through the night were breastfed, compared to 47.1% of infants not sleeping through the night (P less than 0.0001), Dr. Pennestri and colleagues reported.

However, that breastfeeding observation needs to be further investigated, according to the authors.

“The results of our study do not allow for the drawing of any causality between not sleeping through the night and breastfeeding,” they wrote.

Dr. Pennestri and coauthors said they had no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to their report. They reported funding from the Ludmer Center for Neuroinformatics and Mental Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and several other research institutions.

SOURCE: Pennestri MH, et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20174330.

Multiple studies looking at whether sleep matters in infants and no clear consensus, the answer going forward may depend on the primary outcome evaluated, Jodi A. Mindell, PhD, and Melisa Moore, PhD

“The jury is still out,” Dr. Mindell and Dr. Moore wrote in an editorial discussing the present study, which like others before it have found no relationship or limited relationships between infant sleep and later development.

On the other hand, several studies have found that fragmented sleep is associated with negative outcomes with respect to development, the editorial authors said.

One reason for the lack of agreement between studies may be differences in measurement, as the studies to date have used a variety of different measures for both sleep and development, they said. Moreover, the age of infants varies across studies, as does their location, raising the possibility that cultural differences may account for the disparate results.

Beyond that, they added, there is no single primary sleep outcome that has been applied, with some studies looking at sleep duration, and others looking at sleep consolidation, longest stretch of sleep, or duration of night wakings.

What some of these studies may miss is that many other factors may influence development, including genetics, nutrition, parental education, and interaction between child and parent.

“Sleep may be a drop in the bucket for broad development but, instead, have a more significant impact on next-day functioning,” they said.

Thus, the editorialists propose that future studies evaluate function instead of development to assess the importance of infant sleep, as some studies to date have shown that sleep in infants is important for language learning and memory consolidation.

“Rather than investigate gross development, we propose that day-to-day functioning and skill development may be better indicators of the impact of sleep on development in early childhood,” they concluded.

Dr. Mindell, and Dr. Moore are with the Sleep Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Their editorial appears in Pediatrics. Dr. Mindell reported she is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Consumer. Dr. Moore reported no financial relationships relevant to the article.

Multiple studies looking at whether sleep matters in infants and no clear consensus, the answer going forward may depend on the primary outcome evaluated, Jodi A. Mindell, PhD, and Melisa Moore, PhD

“The jury is still out,” Dr. Mindell and Dr. Moore wrote in an editorial discussing the present study, which like others before it have found no relationship or limited relationships between infant sleep and later development.

On the other hand, several studies have found that fragmented sleep is associated with negative outcomes with respect to development, the editorial authors said.

One reason for the lack of agreement between studies may be differences in measurement, as the studies to date have used a variety of different measures for both sleep and development, they said. Moreover, the age of infants varies across studies, as does their location, raising the possibility that cultural differences may account for the disparate results.

Beyond that, they added, there is no single primary sleep outcome that has been applied, with some studies looking at sleep duration, and others looking at sleep consolidation, longest stretch of sleep, or duration of night wakings.

What some of these studies may miss is that many other factors may influence development, including genetics, nutrition, parental education, and interaction between child and parent.

“Sleep may be a drop in the bucket for broad development but, instead, have a more significant impact on next-day functioning,” they said.

Thus, the editorialists propose that future studies evaluate function instead of development to assess the importance of infant sleep, as some studies to date have shown that sleep in infants is important for language learning and memory consolidation.

“Rather than investigate gross development, we propose that day-to-day functioning and skill development may be better indicators of the impact of sleep on development in early childhood,” they concluded.

Dr. Mindell, and Dr. Moore are with the Sleep Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Their editorial appears in Pediatrics. Dr. Mindell reported she is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Consumer. Dr. Moore reported no financial relationships relevant to the article.

Multiple studies looking at whether sleep matters in infants and no clear consensus, the answer going forward may depend on the primary outcome evaluated, Jodi A. Mindell, PhD, and Melisa Moore, PhD

“The jury is still out,” Dr. Mindell and Dr. Moore wrote in an editorial discussing the present study, which like others before it have found no relationship or limited relationships between infant sleep and later development.

On the other hand, several studies have found that fragmented sleep is associated with negative outcomes with respect to development, the editorial authors said.

One reason for the lack of agreement between studies may be differences in measurement, as the studies to date have used a variety of different measures for both sleep and development, they said. Moreover, the age of infants varies across studies, as does their location, raising the possibility that cultural differences may account for the disparate results.

Beyond that, they added, there is no single primary sleep outcome that has been applied, with some studies looking at sleep duration, and others looking at sleep consolidation, longest stretch of sleep, or duration of night wakings.

What some of these studies may miss is that many other factors may influence development, including genetics, nutrition, parental education, and interaction between child and parent.

“Sleep may be a drop in the bucket for broad development but, instead, have a more significant impact on next-day functioning,” they said.

Thus, the editorialists propose that future studies evaluate function instead of development to assess the importance of infant sleep, as some studies to date have shown that sleep in infants is important for language learning and memory consolidation.

“Rather than investigate gross development, we propose that day-to-day functioning and skill development may be better indicators of the impact of sleep on development in early childhood,” they concluded.

Dr. Mindell, and Dr. Moore are with the Sleep Center, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Their editorial appears in Pediatrics. Dr. Mindell reported she is a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Consumer. Dr. Moore reported no financial relationships relevant to the article.

Just over half of infants get 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep at 12 months of age, an analysis of findings from a longitudinal birth cohort study showed.

It also found that whether an infant sleeps through night has no significant associated with any variations in mental or psychomotor development.

However, the rate of breastfeeding was significantly higher among infants who did not sleep through the night, investigators said in their report on the analysis, published in Pediatrics.

Being informed about the normal development of the sleep-wake cycle could be reassuring for parents, according to the authors, who said that new mothers tend to be “greatly surprised” by the sleep disturbance and exhaustion they experience.

“Keeping in mind the wide variability in the age when an infant starts to sleep through the night, expectations for early sleep consolidation could be moderated,” said Marie-Hélène Pennestri, PhD, of the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University, Montreal, and her coauthors.

Dr. Pennestri and colleagues reported on 388 mother-infant dyads in a longitudinal birth cohort study called Maternal Adversity, Vulnerability, and Neurodevelopment (MAVAN). Pregnant mothers were recruited from obstetric clinics in Canada. When their infants reached the age of 6 and 12 months, the mothers responded to questionnaires about sleep habits.

At 6 months, 62.4% of infants attained at least 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep, mothers reported, while 43.0% had reached 8 hours, the mothers reported. By 12 months of age, 72.1% of the infants attained 6 hours, and 56.6% attained 8 hours.

There were no associations between sleeping through the night and concurrent mental or psychomotor development, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II at both 6 or 12 months of age, with P values greater than 0.05, investigators reported.

A similar lack of association between uninterrupted sleep and development or maternal mood was seen in a follow-up measurement at 36 months of age.

Sleeping through the night was likewise not associated with maternal mood, assessed using a depression scale with items that reflected symptom frequency in the previous week. “This is noteworthy because maternal sleep deprivation is often invoked to support the introduction of early behavioral interventions,” investigators said in a discussion of the results.

By contrast, sleeping through the night was linked to lower rates of breastfeeding as reported by mothers on retrospective questionnaires administered at both 6 and 12 months. At 12 months of age, 22.1% of infants sleeping through the night were breastfed, compared to 47.1% of infants not sleeping through the night (P less than 0.0001), Dr. Pennestri and colleagues reported.

However, that breastfeeding observation needs to be further investigated, according to the authors.

“The results of our study do not allow for the drawing of any causality between not sleeping through the night and breastfeeding,” they wrote.

Dr. Pennestri and coauthors said they had no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to their report. They reported funding from the Ludmer Center for Neuroinformatics and Mental Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and several other research institutions.

SOURCE: Pennestri MH, et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20174330.

Just over half of infants get 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep at 12 months of age, an analysis of findings from a longitudinal birth cohort study showed.

It also found that whether an infant sleeps through night has no significant associated with any variations in mental or psychomotor development.

However, the rate of breastfeeding was significantly higher among infants who did not sleep through the night, investigators said in their report on the analysis, published in Pediatrics.

Being informed about the normal development of the sleep-wake cycle could be reassuring for parents, according to the authors, who said that new mothers tend to be “greatly surprised” by the sleep disturbance and exhaustion they experience.

“Keeping in mind the wide variability in the age when an infant starts to sleep through the night, expectations for early sleep consolidation could be moderated,” said Marie-Hélène Pennestri, PhD, of the Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology at McGill University, Montreal, and her coauthors.

Dr. Pennestri and colleagues reported on 388 mother-infant dyads in a longitudinal birth cohort study called Maternal Adversity, Vulnerability, and Neurodevelopment (MAVAN). Pregnant mothers were recruited from obstetric clinics in Canada. When their infants reached the age of 6 and 12 months, the mothers responded to questionnaires about sleep habits.

At 6 months, 62.4% of infants attained at least 6 hours of uninterrupted sleep, mothers reported, while 43.0% had reached 8 hours, the mothers reported. By 12 months of age, 72.1% of the infants attained 6 hours, and 56.6% attained 8 hours.

There were no associations between sleeping through the night and concurrent mental or psychomotor development, as measured by the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II at both 6 or 12 months of age, with P values greater than 0.05, investigators reported.

A similar lack of association between uninterrupted sleep and development or maternal mood was seen in a follow-up measurement at 36 months of age.

Sleeping through the night was likewise not associated with maternal mood, assessed using a depression scale with items that reflected symptom frequency in the previous week. “This is noteworthy because maternal sleep deprivation is often invoked to support the introduction of early behavioral interventions,” investigators said in a discussion of the results.

By contrast, sleeping through the night was linked to lower rates of breastfeeding as reported by mothers on retrospective questionnaires administered at both 6 and 12 months. At 12 months of age, 22.1% of infants sleeping through the night were breastfed, compared to 47.1% of infants not sleeping through the night (P less than 0.0001), Dr. Pennestri and colleagues reported.

However, that breastfeeding observation needs to be further investigated, according to the authors.

“The results of our study do not allow for the drawing of any causality between not sleeping through the night and breastfeeding,” they wrote.

Dr. Pennestri and coauthors said they had no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest to disclose relevant to their report. They reported funding from the Ludmer Center for Neuroinformatics and Mental Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and several other research institutions.

SOURCE: Pennestri MH, et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20174330.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Sleeping through the night in infancy was not significantly associated with any variations in development or maternal mood.

Major finding: There were no associations between 6 or 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep and concurrent mental or psychomotor development or reported depressive symptoms.

Study details: An analysis of 388 mother-infant dyads in a longitudinal birth cohort study.

Disclosures: Authors said they had no financial relationships or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Source: Pennestri MH, et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20174330.

Platelet transfusion threshold matters for preterm infants

A lower threshold for platelet transfusions in preterm infants with severe thrombocytopenia is associated with significantly lower incidence of death and major bleeding, compared with a higher threshold, a new study suggests.

A new major bleeding episode or death occurred in 26% of infants in the high-threshold group, compared with 19% in the low-threshold group, representing a 57% higher risk of poor outcomes even after researchers adjusted for gestational age and intrauterine growth restriction (odds ratio, 1.57; P = .02).

Researchers reported the results of a trial in 660 infants with a mean gestational age of 26.6 weeks, who were randomized to a platelet infusion either at a high platelet–count threshold of 50,000/mm3 or a low threshold of 25,000/mm3.

“Although retrospective studies have suggested that platelet transfusions may cause harm in neonates independently of the disease process, data from randomized controlled trials to support this are lacking,” Anna Curley, MD, of the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin and her coauthors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The rates of minor or worse bleeding were similar between the two groups, and the percentage of infants surviving with bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks of corrected age was higher in the high-threshold group (63% vs. 54%; OR, 1.54).

The rates of serious adverse events, not including major bleeding, were similar between the high- and low-threshold groups.

The outcomes of transfusions were not influenced by other factors such as intrauterine growth restriction, gestational age, or postnatal age at randomization.

“Our trial highlights the importance of trials of platelet transfusion involving patients with conditions other than haematological malignancies,” the authors wrote.

However they acknowledged that the reasons for the differences in mortality and outcomes between the two study groups were unknown.

“Platelets have recognized immunological and inflammatory effects, outside of effects on hemostasis,” they wrote. “The effect of transfusing adult platelets to a delicately balance neonatal hemostatic system with relatively hypofunctional platelets is also poorly understood.”

The study was supported by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant Research and Development Committee and other foundations. Authors reported financial disclosures related to Sanquin and Cerus.

SOURCE: Curley A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807320.

A lower threshold for platelet transfusions in preterm infants with severe thrombocytopenia is associated with significantly lower incidence of death and major bleeding, compared with a higher threshold, a new study suggests.

A new major bleeding episode or death occurred in 26% of infants in the high-threshold group, compared with 19% in the low-threshold group, representing a 57% higher risk of poor outcomes even after researchers adjusted for gestational age and intrauterine growth restriction (odds ratio, 1.57; P = .02).

Researchers reported the results of a trial in 660 infants with a mean gestational age of 26.6 weeks, who were randomized to a platelet infusion either at a high platelet–count threshold of 50,000/mm3 or a low threshold of 25,000/mm3.

“Although retrospective studies have suggested that platelet transfusions may cause harm in neonates independently of the disease process, data from randomized controlled trials to support this are lacking,” Anna Curley, MD, of the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin and her coauthors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The rates of minor or worse bleeding were similar between the two groups, and the percentage of infants surviving with bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks of corrected age was higher in the high-threshold group (63% vs. 54%; OR, 1.54).

The rates of serious adverse events, not including major bleeding, were similar between the high- and low-threshold groups.

The outcomes of transfusions were not influenced by other factors such as intrauterine growth restriction, gestational age, or postnatal age at randomization.

“Our trial highlights the importance of trials of platelet transfusion involving patients with conditions other than haematological malignancies,” the authors wrote.

However they acknowledged that the reasons for the differences in mortality and outcomes between the two study groups were unknown.

“Platelets have recognized immunological and inflammatory effects, outside of effects on hemostasis,” they wrote. “The effect of transfusing adult platelets to a delicately balance neonatal hemostatic system with relatively hypofunctional platelets is also poorly understood.”

The study was supported by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant Research and Development Committee and other foundations. Authors reported financial disclosures related to Sanquin and Cerus.

SOURCE: Curley A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807320.

A lower threshold for platelet transfusions in preterm infants with severe thrombocytopenia is associated with significantly lower incidence of death and major bleeding, compared with a higher threshold, a new study suggests.

A new major bleeding episode or death occurred in 26% of infants in the high-threshold group, compared with 19% in the low-threshold group, representing a 57% higher risk of poor outcomes even after researchers adjusted for gestational age and intrauterine growth restriction (odds ratio, 1.57; P = .02).

Researchers reported the results of a trial in 660 infants with a mean gestational age of 26.6 weeks, who were randomized to a platelet infusion either at a high platelet–count threshold of 50,000/mm3 or a low threshold of 25,000/mm3.

“Although retrospective studies have suggested that platelet transfusions may cause harm in neonates independently of the disease process, data from randomized controlled trials to support this are lacking,” Anna Curley, MD, of the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin and her coauthors reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The rates of minor or worse bleeding were similar between the two groups, and the percentage of infants surviving with bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks of corrected age was higher in the high-threshold group (63% vs. 54%; OR, 1.54).

The rates of serious adverse events, not including major bleeding, were similar between the high- and low-threshold groups.

The outcomes of transfusions were not influenced by other factors such as intrauterine growth restriction, gestational age, or postnatal age at randomization.

“Our trial highlights the importance of trials of platelet transfusion involving patients with conditions other than haematological malignancies,” the authors wrote.

However they acknowledged that the reasons for the differences in mortality and outcomes between the two study groups were unknown.

“Platelets have recognized immunological and inflammatory effects, outside of effects on hemostasis,” they wrote. “The effect of transfusing adult platelets to a delicately balance neonatal hemostatic system with relatively hypofunctional platelets is also poorly understood.”

The study was supported by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant Research and Development Committee and other foundations. Authors reported financial disclosures related to Sanquin and Cerus.

SOURCE: Curley A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807320.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The odds of new major bleeding or death were 57% higher in preterm infants who received a platelet transfusion at a higher threshold of 50,000 per mm3 than at a lower threshold of 25,000 mm3 (P = .02).Study details: Randomized study in 660 preterm infants with severe thrombocytopenia.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant Research and Development Committee, and other foundations. Authors reported financial disclosures related to Sanquin and Cerus.

Source: Curley A et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807320.

In pediatric ICU, being underweight can be deadly

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.