User login

Kidney Stones Linked to CVD, Metabolic Syndrome

WASHINGTON – Research has documented a strong association between the formation of kidney stones and the presence or development of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and a number of components of the metabolic syndrome, said Dr. Dean G. Assimos.

"There is increasing evidence" of this link, he noted at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association. "We need to be cognizant of these associations."

Most recently, an analysis of data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study showed that individuals who developed kidney stones had a 1.6-fold increased risk of developing subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis, even after adjustments for major cardiovascular risk factors were made, said Dr. Assimos, professor of urology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The longitudinal cohort study followed 5,115 white and black men and women who were 18-30 years old at the time of recruitment in 1985-1986. Carotid artery intima-media thickness was measured with serial ultrasound periodically throughout the observation period. By 20 years, almost 4% had reported having kidney stones, and kidney stones were associated with a 60% increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis (J. Urol. 2011;185:920-5). Kidney stones were associated with myocardial infarction (MI) in another recent study aimed specifically at assessing "the risk of a kidney stone former developing an MI," Dr. Assimos said. Investigators of this case-controlled study matched almost 4,600 stone formers on age and sex with almost 11,000 control subjects among residents of Olmstead County, Minn.

During a mean follow-up of 9 years, "despite controlling for other medical comorbidities," investigators found that "stone formers had a 31% increased risk of sustaining an MI," he said.

Chronic kidney disease, which itself is a risk factor for MI, was one of the comorbidities adjusted for (J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:1641-4).

Numerous studies published since 2005 have demonstrated positive associations between kidney stone formation and specific components of the metabolic syndrome, as well as with the full constellation of disorders, Dr. Assimos said.

An analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data published in 2008, for instance, showed that individuals with four traits of the metabolic syndrome had two times the risk of having a history of kidney stones (Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008;51:741-7). The prevalence of self-reported history of kidney stones, moreover, increased as the number of traits or component disorders of the metabolic syndrome increased, from 3% with no disorders to 7.5% with three disorders, and to almost 10% with five disorders. (An individual must have at least three of the five component disorders to qualify as having the metabolic syndrome.)

Similarly, in an Italian study of hospitalized adults, more than 10% of 725 patients with metabolic syndrome had evidence of nephrolithiasis on renal ultrasound (Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2009;24:900-6). "This is 10 times higher than [rates reported from] renal ultrasound screening studies done in the general population," Dr. Assimos said.

Data from three large cohorts – the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) I of older women, the NHS II of younger women, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) of men aged 40-75 years – have been crucial in elucidating the associations between kidney stones and specific components of the metabolic syndrome.

In one prospective study of the cohorts that looked at the incidence of symptomatic kidney stones, for instance, investigators documented that the relative risk of an obese individual (body mass index, 30 kg/m2 or greater) for kidney stone formation, compared with individuals with a BMI of 21-23, was 1.9 in the NHS I cohort, 2.09 in the NHS II cohort, and 1.33 in the HPFS cohort (JAMA 2005;293:455-62).

"There was also a positive correlation in all these cohorts with waist circumference," Dr. Assimos said.

Other analyses of these cohorts have documented positive associations between type 2 diabetes or hypertension, and incident kidney stone formation, as well as associations between a history of kidney stone formation and the diagnosis of diabetes or development of hypertension.

The causative factors underlying the associations between stone formation and cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome include low urinary pH levels. At lower urinary pH levels, "more [of the body’s] uric acid is in its undissociated form and is insoluble in urine," for instance, which increases the risk of uric acid stone formation, Dr. Assimos said.

Studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between BMI and urinary pH, he noted. The reasons are not fully known, but "it is hypothesized that individuals [with higher BMI] do not produce ammonium effectively in the proximal tubule," he said.

Individuals with obesity and low urinary pH also excrete greater amounts of calcium and oxalate, and this increases the risk of calcium oxalate stone formation, he said.

Dr. Assimos’s own research team has identified a possible new pathway for the endogenous synthesis of oxalate. It involves the metabolism of glyoxal, which is stimulated by oxidative stress. The glyoxal metabolism "may explain the increased oxalate excretion in those with obesity as well as diabetes," he said.

The associations between kidney stone formation and cardiovascular risk have hit home for Dr. Assimos, he said at the end of his presentation. At age 39, he developed his first kidney stone. By 3 years later, he developed hypertension. "And 3 years ago. I started having symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux when exercising ... I had a stress test ... and here is my coronary arteriogram," he told the audience. The end result, he said, was successful coronary artery bypass grafting.

Dr. Assimos reported that he is an investigator for the National Institutes of Health and a partner at Piedmont Stone, a facility in Winston-Salem that provides lithotripsy procedures.

WASHINGTON – Research has documented a strong association between the formation of kidney stones and the presence or development of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and a number of components of the metabolic syndrome, said Dr. Dean G. Assimos.

"There is increasing evidence" of this link, he noted at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association. "We need to be cognizant of these associations."

Most recently, an analysis of data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study showed that individuals who developed kidney stones had a 1.6-fold increased risk of developing subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis, even after adjustments for major cardiovascular risk factors were made, said Dr. Assimos, professor of urology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The longitudinal cohort study followed 5,115 white and black men and women who were 18-30 years old at the time of recruitment in 1985-1986. Carotid artery intima-media thickness was measured with serial ultrasound periodically throughout the observation period. By 20 years, almost 4% had reported having kidney stones, and kidney stones were associated with a 60% increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis (J. Urol. 2011;185:920-5). Kidney stones were associated with myocardial infarction (MI) in another recent study aimed specifically at assessing "the risk of a kidney stone former developing an MI," Dr. Assimos said. Investigators of this case-controlled study matched almost 4,600 stone formers on age and sex with almost 11,000 control subjects among residents of Olmstead County, Minn.

During a mean follow-up of 9 years, "despite controlling for other medical comorbidities," investigators found that "stone formers had a 31% increased risk of sustaining an MI," he said.

Chronic kidney disease, which itself is a risk factor for MI, was one of the comorbidities adjusted for (J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:1641-4).

Numerous studies published since 2005 have demonstrated positive associations between kidney stone formation and specific components of the metabolic syndrome, as well as with the full constellation of disorders, Dr. Assimos said.

An analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data published in 2008, for instance, showed that individuals with four traits of the metabolic syndrome had two times the risk of having a history of kidney stones (Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008;51:741-7). The prevalence of self-reported history of kidney stones, moreover, increased as the number of traits or component disorders of the metabolic syndrome increased, from 3% with no disorders to 7.5% with three disorders, and to almost 10% with five disorders. (An individual must have at least three of the five component disorders to qualify as having the metabolic syndrome.)

Similarly, in an Italian study of hospitalized adults, more than 10% of 725 patients with metabolic syndrome had evidence of nephrolithiasis on renal ultrasound (Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2009;24:900-6). "This is 10 times higher than [rates reported from] renal ultrasound screening studies done in the general population," Dr. Assimos said.

Data from three large cohorts – the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) I of older women, the NHS II of younger women, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) of men aged 40-75 years – have been crucial in elucidating the associations between kidney stones and specific components of the metabolic syndrome.

In one prospective study of the cohorts that looked at the incidence of symptomatic kidney stones, for instance, investigators documented that the relative risk of an obese individual (body mass index, 30 kg/m2 or greater) for kidney stone formation, compared with individuals with a BMI of 21-23, was 1.9 in the NHS I cohort, 2.09 in the NHS II cohort, and 1.33 in the HPFS cohort (JAMA 2005;293:455-62).

"There was also a positive correlation in all these cohorts with waist circumference," Dr. Assimos said.

Other analyses of these cohorts have documented positive associations between type 2 diabetes or hypertension, and incident kidney stone formation, as well as associations between a history of kidney stone formation and the diagnosis of diabetes or development of hypertension.

The causative factors underlying the associations between stone formation and cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome include low urinary pH levels. At lower urinary pH levels, "more [of the body’s] uric acid is in its undissociated form and is insoluble in urine," for instance, which increases the risk of uric acid stone formation, Dr. Assimos said.

Studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between BMI and urinary pH, he noted. The reasons are not fully known, but "it is hypothesized that individuals [with higher BMI] do not produce ammonium effectively in the proximal tubule," he said.

Individuals with obesity and low urinary pH also excrete greater amounts of calcium and oxalate, and this increases the risk of calcium oxalate stone formation, he said.

Dr. Assimos’s own research team has identified a possible new pathway for the endogenous synthesis of oxalate. It involves the metabolism of glyoxal, which is stimulated by oxidative stress. The glyoxal metabolism "may explain the increased oxalate excretion in those with obesity as well as diabetes," he said.

The associations between kidney stone formation and cardiovascular risk have hit home for Dr. Assimos, he said at the end of his presentation. At age 39, he developed his first kidney stone. By 3 years later, he developed hypertension. "And 3 years ago. I started having symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux when exercising ... I had a stress test ... and here is my coronary arteriogram," he told the audience. The end result, he said, was successful coronary artery bypass grafting.

Dr. Assimos reported that he is an investigator for the National Institutes of Health and a partner at Piedmont Stone, a facility in Winston-Salem that provides lithotripsy procedures.

WASHINGTON – Research has documented a strong association between the formation of kidney stones and the presence or development of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and a number of components of the metabolic syndrome, said Dr. Dean G. Assimos.

"There is increasing evidence" of this link, he noted at the annual meeting of the American Urological Association. "We need to be cognizant of these associations."

Most recently, an analysis of data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study showed that individuals who developed kidney stones had a 1.6-fold increased risk of developing subclinical carotid artery atherosclerosis, even after adjustments for major cardiovascular risk factors were made, said Dr. Assimos, professor of urology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The longitudinal cohort study followed 5,115 white and black men and women who were 18-30 years old at the time of recruitment in 1985-1986. Carotid artery intima-media thickness was measured with serial ultrasound periodically throughout the observation period. By 20 years, almost 4% had reported having kidney stones, and kidney stones were associated with a 60% increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis (J. Urol. 2011;185:920-5). Kidney stones were associated with myocardial infarction (MI) in another recent study aimed specifically at assessing "the risk of a kidney stone former developing an MI," Dr. Assimos said. Investigators of this case-controlled study matched almost 4,600 stone formers on age and sex with almost 11,000 control subjects among residents of Olmstead County, Minn.

During a mean follow-up of 9 years, "despite controlling for other medical comorbidities," investigators found that "stone formers had a 31% increased risk of sustaining an MI," he said.

Chronic kidney disease, which itself is a risk factor for MI, was one of the comorbidities adjusted for (J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010;21:1641-4).

Numerous studies published since 2005 have demonstrated positive associations between kidney stone formation and specific components of the metabolic syndrome, as well as with the full constellation of disorders, Dr. Assimos said.

An analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data published in 2008, for instance, showed that individuals with four traits of the metabolic syndrome had two times the risk of having a history of kidney stones (Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008;51:741-7). The prevalence of self-reported history of kidney stones, moreover, increased as the number of traits or component disorders of the metabolic syndrome increased, from 3% with no disorders to 7.5% with three disorders, and to almost 10% with five disorders. (An individual must have at least three of the five component disorders to qualify as having the metabolic syndrome.)

Similarly, in an Italian study of hospitalized adults, more than 10% of 725 patients with metabolic syndrome had evidence of nephrolithiasis on renal ultrasound (Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2009;24:900-6). "This is 10 times higher than [rates reported from] renal ultrasound screening studies done in the general population," Dr. Assimos said.

Data from three large cohorts – the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) I of older women, the NHS II of younger women, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) of men aged 40-75 years – have been crucial in elucidating the associations between kidney stones and specific components of the metabolic syndrome.

In one prospective study of the cohorts that looked at the incidence of symptomatic kidney stones, for instance, investigators documented that the relative risk of an obese individual (body mass index, 30 kg/m2 or greater) for kidney stone formation, compared with individuals with a BMI of 21-23, was 1.9 in the NHS I cohort, 2.09 in the NHS II cohort, and 1.33 in the HPFS cohort (JAMA 2005;293:455-62).

"There was also a positive correlation in all these cohorts with waist circumference," Dr. Assimos said.

Other analyses of these cohorts have documented positive associations between type 2 diabetes or hypertension, and incident kidney stone formation, as well as associations between a history of kidney stone formation and the diagnosis of diabetes or development of hypertension.

The causative factors underlying the associations between stone formation and cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome include low urinary pH levels. At lower urinary pH levels, "more [of the body’s] uric acid is in its undissociated form and is insoluble in urine," for instance, which increases the risk of uric acid stone formation, Dr. Assimos said.

Studies have demonstrated a negative correlation between BMI and urinary pH, he noted. The reasons are not fully known, but "it is hypothesized that individuals [with higher BMI] do not produce ammonium effectively in the proximal tubule," he said.

Individuals with obesity and low urinary pH also excrete greater amounts of calcium and oxalate, and this increases the risk of calcium oxalate stone formation, he said.

Dr. Assimos’s own research team has identified a possible new pathway for the endogenous synthesis of oxalate. It involves the metabolism of glyoxal, which is stimulated by oxidative stress. The glyoxal metabolism "may explain the increased oxalate excretion in those with obesity as well as diabetes," he said.

The associations between kidney stone formation and cardiovascular risk have hit home for Dr. Assimos, he said at the end of his presentation. At age 39, he developed his first kidney stone. By 3 years later, he developed hypertension. "And 3 years ago. I started having symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux when exercising ... I had a stress test ... and here is my coronary arteriogram," he told the audience. The end result, he said, was successful coronary artery bypass grafting.

Dr. Assimos reported that he is an investigator for the National Institutes of Health and a partner at Piedmont Stone, a facility in Winston-Salem that provides lithotripsy procedures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN UROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Twice as common as autism and half as well-known,1 autosomal polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) occurs in one in 400 to one in 1,000 people.2 It is an inherited progressive genetic disorder that causes hypertension and decreased renal function and, over time, can lead to kidney failure. Two polycstin genes that code for ADPKD, PKD1 and PKD2, were identified in 1994 and 1996, respectively.3,4 Awareness and understanding of the genes responsible for ADPKD have increased clinicians’ ability to identify at-risk patients and to slow or alter the course of the disease.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old black man presents to your office with severe, nonradiating back pain and new-onset hypertension. Regarding the pain, he stated, “I turned around to see who kicked me, but no one was there.” When the pain began, he went to see the nurse at the school where he is employed, and she found that his blood pressure was high at 162/90 mm Hg. Although the patient’s back pain is resolving, he is very concerned about his blood pressure, since he has never had a high reading before.

He is the baseball coach and physical education teacher at the local high school and is in excellent physical condition as a result of his professional interaction with teenagers every day. He does not smoke or use any illicit drugs but does admit to occasional alcohol consumption. His medical history is significant only for occasional broken fingers and twisted ankles, all occurring while he was engaged in sports.

His family history includes one brother without medical problems, a brother and a sister with hypertension, a sister with diabetes and obesity, and a brother with a congenital abnormality that required a living donor kidney transplant at age 17 (the father served as donor). No family-wide workup has ever been done because no one practitioner has ever made a connection among these conditions and considered a diagnosis of ADPKD.

The patient’s blood pressure in the office is 172/92 mm Hg while sitting and 166/88 mm Hg while standing. He is somewhat sore with a localized spasm in the lumbar-sacral area but no radiation of pain. The patient has trouble touching his toes but reports that he can never touch his toes. His straight leg lift is negative. The rest of his physical exam is noncontributory.

What should be the next step in this patient’s workup?

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

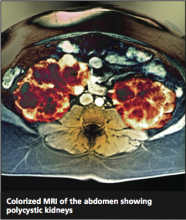

ADPKD is a progressive expansion of numerous fluid-filled cysts that result in massive enlargement of the kidneys.5 Less than 5% of all nephrons become cystic; however, the average volume of a polycystic kidney is 1,000 mL (normal, 300 mL), that is, the volume of a standard-sized pineapple. Even with this significant enlargement, a decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not usually seen initially. Each cyst is derived from a single hyperproliferative epithelial cell. Increased cellular proliferation, followed by fluid secretion and alterations in the extracellular matrix, cause an outpouching from the parent nephron, which eventually detaches from the parent nephron and continues to enlarge and autonomously secrete fluid.6,7

PKD1 and PKD2 are two genes responsible for ADPKD that have been isolated so far. Since there are families carrying neither the PKD1 nor the PKD2 gene that still have an inherited type of ADPKD, there is suspicion that at least one more PKD gene, not yet isolated, exists.8 It is also possible that other genetic or environmental factors may be at play.9,10

In 1994, the PKD1 gene was isolated on chromosome 16,3 and it was found to code for polycystin 1. A lack of polycystin 1 causes an abnormality in the Na+/K(+)-ATPase pumps, leading to abnormal sodium reabsorption.11 How and why this happens is not quite clear. However, the hypertension that is a key objective finding in patients with ADPKD is thought to result from this pump abnormality.

PKD2 is found on the long arm of chromosome 4 and codes for polycystin 2.4 Polycystin 2 is an amino acid that is responsible for voltage-activated cellular calcium channels,5 again explaining the hypertension so commonly seen in the course of ADPKD. ADPKD-associated hypertension may be present as early as the teenage years.12

EPIDEMIOLOGY

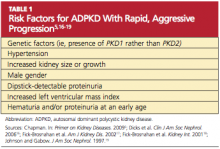

More than 85% of ADPKD cases are associated with PKD1, and this form is called polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD 1), the more aggressive form of the disease.13,14 PKD 2 (the form associated with the gene PKD2), though less common, is also likely to progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), but at a later age (median age of 74 years, compared with 54 in patients with PKD 1).14 ADPKD accounts for about 5% of cases of ESRD in North America,9 but for most patients, presentation and decreased renal function do not occur until the 40s.15 However, patients with the risk factors listed in Table 15,16-19 are likely to experience a more rapid and aggressive form of the disease.

Even with the same germline mutation in a family with this inherited disease, the severity of ADPKD among family members is quite variable; this is true even in the case of twins.9,10,20 Since the age and symptoms at presentation can vary so greatly, a uniform method of identifying patients with ADPKD, along with staging, was needed. Most patients do not undergo genetic testing (ie, DNA linkage or gene-based direct sequencing9) for a diagnosis of ADPKD or to differentiate between the PKD 1 and PKD 2 disease forms unless they are participating in a research study. Diagnostic criteria were needed that were applicable for any type of ADPKD.

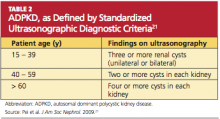

In 2009, the University of Toronto’s Division of Nephrology convened experts in the fields of nephrology and radiology to reach a consensus on standardized ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria.21 They formulated definitions based on a study of 948 individuals who were at risk for either PKD 1 or PKD 2 (see Table 221). The specificity and sensitivity of the resulting criteria range from 82% to 100%, making it possible to standardize the care and classification of renal patients worldwide.

Since family members with the same genotypes can experience very divergent disease manifestations, the two-hit hypothesis has been developed.22 In simple terms, it proposes that after the germline mutation (PKD1 or PKD2), there is a second somatic mutation that leads to progressive cyst formation; when the number and size of cysts increase, the patient starts to experience symptoms of ADPKD.22

Age at presentation can be quite variable, as can the presenting symptoms. Most patients with PKD 1 present in their 50s, with 54 being the average age in US patients.14 The most common presenting symptom is flank or back pain.2,5 The pain is due to the massive enlargement of the kidneys, causing a stretching of the kidney capsule and leading to a chronic, dull and persistent pain in the low back. Severe pain, sharp and cutting, occurs when one of the cysts hemorrhages; to some patients, the pain resembles a quick, powerful “kick in the back.” Hematuria can occur following cyst hemorrhage; depending on the location of the cyst that burst within the kidney (ie, how close it is to the collecting system) and how large it is, the amount and color of the hematuria can be impressive.

ADPKD is more common in men than women, and cyst rupture can be precipitated by trauma or lifting heavy objects. Cyst hemorrhage can turn the urine bright red, which is especially frightening to the male patient. Hematuria is often the key presenting symptom in patients who will be diagnosed with ADPKD-induced hypertension.

Besides hematuria, other common manifestations of ADPKD include:

• Hypertension (60% of affected patients, which increases to 100% by the time ESRD develops)

• Extrarenal cysts (100% of affected patients)

• Urinary tract infections

• Nephrolithiasis (20% of affected patients)

• Proteinuria, occasionally (18% of affected patients).2,5,23

Among these manifestations, those most commonly attributed to a diagnosis of ADPKD are hypertension, kidney stones, and urinary tract or kidney infections. Since isolated proteinuria is unusual in patients with ADPKD, it is recommended that another cause of kidney disease be explored in patients with this presentation.24

Extrarenal manifestations of cyst development are common, eventually occurring in all patients as they age. Hepatic cysts are universal in patients with ADPKD by age 30, although hepatic function is preserved. There may be a mild elevation in the alkaline phosphatase level in patients with ADPKD, resulting from the presence of hepatic cysts. Cysts may also be found in the pancreas, spleen, thyroid, and epididymis.5,25 Some patients may complain of dyspnea, pain, early satiety, or lower extremity edema as a result of enlarged cyst.

The Case Patient

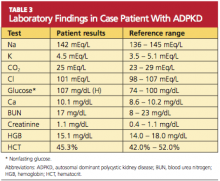

Because you recently attended a lecture about ADPKD, you are aware that flank pain in men with hypertension is indicative of ADPKD until proven otherwise. Believing that this patient’s hypertension is renal in origin, you order an abdominal ultrasound. You also order a comprehensive metabolic panel and a complete blood count. The patient’s GFR is measured at 89 mL/min (indicative of stage 2 kidney disease). Other results are shown in Table 3.

The very broad differential includes essential hypertension, hypertension resulting from intake of “power drinks” or salt in an athlete, illicit use of medications (including steroids), herniated disc leading to transient hypertension, and urinary tract infection or sexually transmitted disease. All of this is moot when the ultrasound shows both kidneys measuring greater than 15 cm, with four distinct cysts on the right kidney and three distinct cysts on the left.

You explain to the patient that ADPKD is a genetic disease and that he and his siblings each had a certain chance of inheriting it. Although different presentations may occur (“congenital” polycystic kidney disease, hypertension, or obesity), they all must undergo ultrasonographic screening for ADPKD. You add that although ADPKD is a genetic disease, it can also be diagnosed in different members of the same family at different ages.

TREATMENT

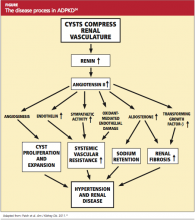

The goal of treatment for the patient with ADPKD is to slow cyst development and the natural course of the disease. If this can be achieved, the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation may be postponed for a number of years. Because cyst growth causes an elevation in renin and activates the angiotensin II renin system26 (see figure,24), an ACE inhibitor is the most effective treatment to lower blood pressure and thus slow the progression of ADPKD. Most patients with ADPKD are started on an ACE inhibitor at an early age to slow the rate of disease progression.27,28 Several studies are under way to determine the best antihypertensive medication and the optimal age for initiating treatment.29,30

Lipid screening and treatment for dyslipidemia are important23 because ADPKD can lead to a reduction in kidney function, resulting in chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent, and most professionals will treat the patient with ADPKD for hyperlipidemia.23,31 While there are no data showing that statin use will reduce the incidence of ESRD or delay the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation in patients with ADPKD, the beneficial effects of good renal blood flow and endothelial function have been noted.32,33

One of the most common and significant complications in ADPKD is intracranial hemorrhage resulting from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. In the younger adult, the incidence of cerebral aneurysm is 4%, but incidence increases to 10% in patients older than 65.34-36 Family clusters of aneurysms have been reported.37 If an intracranial aneurysm is found in the family history, the risk of an aneurysm in another family member increases to 22%.38

Since rupture of an intracranial hemorrhage is associated with a 30-day mortality rate of 50% and 80% morbidity,5,38 standard of care for patients with ADPKD includes CT or magnetic resonance angiographic (MRA) screening in the asymptomatic patient with a positive family history.34,38 If an aneurysm is found, the lifetime chance of rupture is 50%, although the risk is greater in the case of an aneurysm larger than 10 mm.5

As in all patients with kidney disease, left ventricular hypertrophy is common among patients with ADPKD.23,28,39

The Case Patient

The patient is started on an ACE inhibitor, scheduled for fasting lipid screening, and referred to a nephrology practice for disease management. As research and investigation of possible treatment options for ADPKD are ongoing, the patient may benefit from participating in a new research protocol.

Because the patient’s family has no history of cerebral aneurysm, CT/MRA screening is not required. A discussion of the pros and cons of genetic testing for the entire family, including nieces and nephews, is initiated. The patient and his family are referred to a genetic counselor to decide whether the benefit of early treatment for hypertension outweighs the risk of carrying a diagnosis of ADPKD for his younger relatives, who may later seek health insurance coverage.

NATURAL PROGRESSION OF ADPKD

Hypertension and cyst formation will continue as the patient ages. The natural progression of ADPKD is to renal failure with renal replacement therapy (dialysis or organ transplantation) as treatment options. If the progression of ADPKD can be slowed through pharmacotherapy, the patient may live for many years without needing dialysis. This ideal can be accomplished only through aggressive hypertension control, which should be started in the teenage years.23,30,31

Suggestions to increase fluid consumption and to limit the use of NSAIDs, contrast dye, and MRI with gadolinium are appropriate. It is rare for hypertension to be diagnosed before some organ damage has already occurred.12 Often the patient’s renal function, as determined by measuring the GFR, remains stable until the patient reaches his or her 40s.40 However, kidney damage often begins before any detectable change in GFR. Once the GFR does start to decline, the average decrease is 4.4 to 5.9 mL/min/1.73m2 each year.41

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

For ESRD Organ Transplantation

Kidney transplantation—the only curative treatment for ADPKD—can be offered to patients once the GFR falls below 20 mL/min. However, the patient with ADPKD can experience kidney enlargement to such an extent that introducing a third kidney into the limited abdominal space becomes technically difficult. Although nephrectomy is avoided whenever possible, there are cases in which there is no alternative.42

In addition to space concerns, recurrent urinary tract infections, chronic pain, renal cell carcinoma, chronic hematuria, or chronic cyst infections can necessitate a nephrectomy.43,44 A laparoscopic approach with decompression of cysts or removal of only one kidney is preferred.43,45 If removal of both kidneys is required before a transplant, the patient must be maintained on dialysis until after transplantation. Since the transplant waiting list can exceed seven years in some areas, most patients arrange for a willing live donor before agreeing to a bilateral nephrectomy.46,47

Dialysis

Either peritoneal dialysis (PD) or hemodialysis (HD) can be offered to patients with severe ADPKD. Depending on the size of the native kidneys and the history of previous abdominal surgery, PD often offers a better chance of survival in these patients, particularly compared with patients who have ESRD associated with other causes.48

For management of the patient with ADPKD who receives PD, it can be difficult to differentiate between the pain of a cyst and the pain of a peritoneal infection. Generally, cyst rupture is accompanied by hematuria; and peritonitis, by cloudy fluid.5 Management provided by an experienced nephrologist and PD nurse is vital.

In ADPKD patients who undergo HD, too, survival is better than in patients who have ESRD with other causes49,50; five-year survival can be as high as 10% to 15%.51 This is likely due to the lower incidence of coronary artery disease in the ADPKD population, compared with patients who have ESRD associated with other chronic diseases.49

FUTURE TRENDS AND ONGOING TRIALS

HALT PKD29,30 is an NIH-funded, double-blind study to determine whether adding an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) to standard ACE inhibitor therapy results in a more significant decrease in the progression of renal cysts. The rationale for this is that the ARB is expected to block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the kidney. Use of ACE inhibitor monotherapy versus ARB/ACE inhibitor therapy is being compared in two study arms: patients between ages 15 and 49 with a GFR of 60 mL/min or greater; and patients between ages 18 and 64 with a GFR of 25 to 60 mL/min.29 To date, preliminary results indicate no benefit in adding the second medication.49

The TEMPO Trial52 is a multicenter, double-blind study looking at the effect of tolvaptan on renal cyst growth. Tolvaptan is a potent vasopressin receptor antagonist, and in vitro evidence has shown that intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) plays a large role in the development of cysts in patients with ADPKD. If it is possible to block the cAMP that is causing cyst growth, progression of ADPKD should slow.53,54 Only short-term effects of tolvaptan use are currently known.55

High Water Intake to Slow Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease56 is an open-label, nonrandomized trial in which patients drink a minimum of

3 L of water. Previously, a small study showed that an increase in fluid intake partially suppresses the urine osmolality and the serum antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels.57 According to this theory, increasing water intake to greater than 3 L/d may result in complete suppression of ADH and cAMP. This is a small study (n = 20),56 since patients with ADPKD are likely to have urinary concentrating defects, and hyponatremia is a concern is in these patients.58

Sirolimus and ADPKD59 is an open-label randomized study to see whether sirolimus (also known as rapamycin) can reduce cyst growth. Originally, it was noted that posttransplant ADPKD patients underwent a regression of both liver and kidney cysts when they were taking sirolimus, and a preliminary crossover study was done.60 However, preliminary results at 18 months showed no difference in renal growth or cyst growth but did show kidney damage as determined by an increase of proteinuria in the treatment group.59 The study is still in progress.

Somatostatin in Polycystic Kidney61 is a long-term (three-year) study following patients who agreed to participate in a randomized, double-blind protocol; in it, an intramuscular injection of either an octreotide (ie, somatastatin) or placebo was administered every four weeks for one year in an effort to reduce the size of kidney and liver cysts.62 At one year, the quality of life in the treatment group was rated better, as measured by pain reduction and improved physical activity. Cyst growth in the treatment group was smaller for both the kidney and liver. However, the GFR decreased to the same degree in both groups.62

CONCLUSION

ADPKD is a common, often overlooked genetic disease that is a cause of hypertension. ADPKD’s presenting symptoms of flank pain, back pain, and/or hematuria often bring the patient to the provider, but a high index of suspicion must be maintained to diagnose these patients at an early age. Due to the variable presentation even within affected families, many patients do not realize that their family carries the PKD gene.

While genetic testing is available, ultrasound is a quick, relatively inexpensive, and easy method to screen for this diagnosis. The progression of ADPKD to ESRD, requiring dialysis or organ transplantation, can be slowed with early and aggressive treatment of hypertension. As with all patients affected by renal impairment, suggestions for patients with ADPKD to avoid use of NSAIDs, contrast dye, and gadolinium-enhanced MRI are appropriate. The primary care PA or NP is in an appropriate position to see to this.

REFERENCES

1. Newschaffer CJ, Falb MD, Gurney JG. National autism prevalence trends from United States special education data. Pediatrics. 2005;115 (3):e277-e282.

2. Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1287-1301.

3. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene encodes a 14 kb transcript and lies within a duplicated region on chromosome 16: European Polycystic Kidney Disease Consortium. Cell. 1994;77(6):881-894.

4. Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996; 272(5266):1339-1342.

5. Chapman AB. Polycystic and other cystic kidney diseases. In: Greenberg A, ed. Primer on Kidney Diseases: Expert Consult. 5th ed. National Kidney Foundation; 2009:345-353.

6. Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, et al. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):21-23.

7. Murcia NS, Sweeney WE Jr, Avner ED. New insights into the molecular pathophysiology of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1999;55 (4):1187-1197.

8. Paterson AD, Pei Y. Is there a third gene for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Kidney Int. 1998;54(5):1759-1761.

9. Pei Y. Practical genetics for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118(1):c19-c30.

10. Tan YC, Blumenfeld J, Rennert H. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: genetics, mutations and microRNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011 Mar 16 [Epub ahead of print].

11. Avner ED, Sweeney WE Jr, Nelson WJ. Abnormal sodium pump distribution during renal tubulogenesis in congenital murine polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(16):7447-7451.

12. Torra R, Badenas C, Darnell A, et al. Linkage, clinical features, and prognosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(10):2142-2151.

13. Davies F, Coles GA, Harper PS, et al. Polycystic kidney disease re-evaluated: a population-based study. Q J Med. 1991;79(290):477-485.

14. Hateboer N, v Dijk MA, Bogdanova N, et al; European PKD1-PKD2 Study Group. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):103-107.

15. Peters DJ, Breuning MH. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: modification of disease progression. Lancet. 2001;358(9291):1439-1444.

16. Dicks E, Ravani P, Langman D, et al. Incident renal events and risk factors in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population- and family-based cohort followed for 22 years. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(4):710-717.

17. Fick-Brosnahan GM, Belz MM, McFann KK, etc. Relationship between renal volume growth and renal function in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a longitudinal study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(6):1127-1134.

18. Fick-Brosnahan GM, Tran ZV, Johnson AM, et al. Progression of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. Kidney Int. 2001;59(5):1654-1662.

19. Johnson AM, Gabow PA. Identification of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease at highest risk for end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(10): 1560-1567.

20. Risk D. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Presented at: National Kidney Foundation, Spring Clinical Meetings; April 28, 2011; Las Vegas, NV.

21. Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A, et al. Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(1):205-212.

22. Watnick T, Germino GG. Molecular basis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19(4):327-343.

23. Ecder T, Schrier RW. Cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(4):221-228.

24. Patch C, Charlton J, Roderick PJ, Gulliford MC. Use of antihypertensive medications and mortality of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):856-862.

25. Pirson Y. Extrarenal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(2):173-180.

26. Chapman AB, Johnson A, Gabow PA, Schrier RW. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(16):1091-1096.

27. Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors on progression of advanced polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;67(1):265-271.

28. Schrier RW. Renal volume, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, hypertension, and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(9):1888-1893.

29. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), NIH, sponsor. HALT PKD (Halt Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease): Efficacy of Aggressive Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Axis Blockade in Preventing/Slowing Renal Function Decline in ADPKD. www2.niddk.nih.gov/NR/rdonlyres/175578F6-62B4-429A-9BBF-96CCEC2FFB3A/0/KUHHALT PKDPROTOCOL9107.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2011.

30. Chapman AB, Torres VE, Perrone RD, et al. The HALT polycystic kidney disease trials: design and implementation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(1):102-109.

31. Taylor M, Johnson AM, Tison M, et al. Earlier diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: importance of family history and implications for cardiovascular and renal complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(3):415-423.

32. Namli S, Oflaz H, Turgut F, et al. Improvement of endothelial dysfunction with simvastatin in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2007;29(1):55-59.

33. Bremmer MS, Jacobs SC. Renal artery embolization for the symptomatic treatment of adult polycystic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4(5):236-237.

34. Chapman AB, Rubinstein D, Hughes R, et al. Intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1992; 327(13):916-920.

35. Schievink WI, Torres VE, Piepgras DG, Wiebers DO. Saccular intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;3(1):88-95.

36. Fick GM, Gabow PA. Hereditary and acquired cystic disease of the kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;46(4):951-964.

37. Watson ML. Complications of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1997;51(1):353-365.

38. Huston J 3rd, Torres VE, Sulivan PP, et al. Value of magnetic resonance angiography for the detection of intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(12):1871-1877.

39. Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Powe NR, et al. Traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in dialysis patients compared with the general population: the CHOICE Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(7):1918-1927.

40. Meijer E, Rook M, Tent H, et al. Early renal abnormalities in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010; 5(6):1091-1098.

41. Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int. 2009;76(2):149-168.

42. Tabibi A, Simforoosh N, Abadpour P, et al. Concomitant nephrectomy of massively enlarged kidneys and renal transplantation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(7):2939-2940.

43. Dunn MD, Portis AJ, Elbahnasy AM, et al. Laparoscopic nephrectomy in patients with end-stage renal disease and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(4):720-725.

44. Sulikowski T, Tejchman K, Zietek Z, et al. Experience with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in patients before and after renal transplantation: a 7-year observation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(1):177-180.

45. Desai MR, Nandkishore SK, Ganpule A, Thimmegowda M. Pretransplant laparoscopic nephrectomy in adult polycystic kidney disease: a single centre experience. BJU Int. 2008;101 (1):94-97.

46. Glassman DT, Nipkow L, Bartlett ST, Jacobs SC. Bilateral nephrectomy with concomitant renal graft transplantation for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Urol. 2000;164 (3 pt 1):661-664.

47. Fuller TF, Brennan TV, Feng S, et al. End stage polycystic kidney disease: indications and timing of native nephrectomy relative to kidney transplantation. J Urol. 2005;174(6):2284-2288.

48. Abbott KC, Agodoa LY. Polycystic kidney disease at end-stage renal disease in the United States: patient characteristics and survival. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57(3):208-214.

49. Perrone RD, Ruthazer R, Terrin NC. Survival after end-stage renal disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: contribution of extrarenal complications to mortality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38(4):777-784.

50. Batista PB, Lopes AA, Costa FA. Association between attributed cause of end-stage renal disease and risk of death in Brazilian patients receiving renal replacement therapy. Ren Fail. 2005;27(6):651-656.

51. Pirson Y, Christophe JL, Goffin E. Outcome of renal replacement therapy in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11 suppl 6:24-28.

52. Torres VE, Meijer E, Bae KT, et al. Rationale and design of the TEMPO (Tolvaptan Efficacy and Safety in Management of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and its Outcomes) 3-4 Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(5):692-699.

53. Calvet JP. Strategies to inhibit cyst formation in ADPKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3 (4):1205-1211.

54. Grantham JJ. Lillian Jean Kaplan International Prize for advancement in the understanding of polycystic kidney disease. Understanding polycystic kidney disease: a systems biology approach. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1157-1162.

55. Irazabal MV, Torres VE, Hogan MC, et al. Short-term effects of tolvaptan on renal function and volume in patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2011 May 4 [Epub ahead of print].

56. New York University, sponsor. High Water Intake to Slow Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00784030. Accessed July 22, 2011.

57. Wang CJ, Creed C, Winklhofer FT, Grantham JJ. Water prescription in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a pilot study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(1):192-197.

58. Grampsas SA, Chandhoke Ps, Fan J, et al. Anatomic and metabolic risk factors for nephrolithiasis in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(1):53-57.

59. Serra AL, Poster D, Kistler AD, et al. Sirolimus and kidney growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363(9):820-829.

60. Perico N, Antiga L, Caroli A, et al. Sirolimus therapy to halt the progression of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(6):1031-1040.

61. Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, sponsor. Somatostatin in Polycystic Kidney: a Long-term Three Year Follow up Study. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00309283. Accessed July 22, 2011.

62. Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010; 21(6):1052-1061.

Twice as common as autism and half as well-known,1 autosomal polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) occurs in one in 400 to one in 1,000 people.2 It is an inherited progressive genetic disorder that causes hypertension and decreased renal function and, over time, can lead to kidney failure. Two polycstin genes that code for ADPKD, PKD1 and PKD2, were identified in 1994 and 1996, respectively.3,4 Awareness and understanding of the genes responsible for ADPKD have increased clinicians’ ability to identify at-risk patients and to slow or alter the course of the disease.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old black man presents to your office with severe, nonradiating back pain and new-onset hypertension. Regarding the pain, he stated, “I turned around to see who kicked me, but no one was there.” When the pain began, he went to see the nurse at the school where he is employed, and she found that his blood pressure was high at 162/90 mm Hg. Although the patient’s back pain is resolving, he is very concerned about his blood pressure, since he has never had a high reading before.

He is the baseball coach and physical education teacher at the local high school and is in excellent physical condition as a result of his professional interaction with teenagers every day. He does not smoke or use any illicit drugs but does admit to occasional alcohol consumption. His medical history is significant only for occasional broken fingers and twisted ankles, all occurring while he was engaged in sports.

His family history includes one brother without medical problems, a brother and a sister with hypertension, a sister with diabetes and obesity, and a brother with a congenital abnormality that required a living donor kidney transplant at age 17 (the father served as donor). No family-wide workup has ever been done because no one practitioner has ever made a connection among these conditions and considered a diagnosis of ADPKD.

The patient’s blood pressure in the office is 172/92 mm Hg while sitting and 166/88 mm Hg while standing. He is somewhat sore with a localized spasm in the lumbar-sacral area but no radiation of pain. The patient has trouble touching his toes but reports that he can never touch his toes. His straight leg lift is negative. The rest of his physical exam is noncontributory.

What should be the next step in this patient’s workup?

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

ADPKD is a progressive expansion of numerous fluid-filled cysts that result in massive enlargement of the kidneys.5 Less than 5% of all nephrons become cystic; however, the average volume of a polycystic kidney is 1,000 mL (normal, 300 mL), that is, the volume of a standard-sized pineapple. Even with this significant enlargement, a decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not usually seen initially. Each cyst is derived from a single hyperproliferative epithelial cell. Increased cellular proliferation, followed by fluid secretion and alterations in the extracellular matrix, cause an outpouching from the parent nephron, which eventually detaches from the parent nephron and continues to enlarge and autonomously secrete fluid.6,7

PKD1 and PKD2 are two genes responsible for ADPKD that have been isolated so far. Since there are families carrying neither the PKD1 nor the PKD2 gene that still have an inherited type of ADPKD, there is suspicion that at least one more PKD gene, not yet isolated, exists.8 It is also possible that other genetic or environmental factors may be at play.9,10

In 1994, the PKD1 gene was isolated on chromosome 16,3 and it was found to code for polycystin 1. A lack of polycystin 1 causes an abnormality in the Na+/K(+)-ATPase pumps, leading to abnormal sodium reabsorption.11 How and why this happens is not quite clear. However, the hypertension that is a key objective finding in patients with ADPKD is thought to result from this pump abnormality.

PKD2 is found on the long arm of chromosome 4 and codes for polycystin 2.4 Polycystin 2 is an amino acid that is responsible for voltage-activated cellular calcium channels,5 again explaining the hypertension so commonly seen in the course of ADPKD. ADPKD-associated hypertension may be present as early as the teenage years.12

EPIDEMIOLOGY

More than 85% of ADPKD cases are associated with PKD1, and this form is called polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD 1), the more aggressive form of the disease.13,14 PKD 2 (the form associated with the gene PKD2), though less common, is also likely to progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), but at a later age (median age of 74 years, compared with 54 in patients with PKD 1).14 ADPKD accounts for about 5% of cases of ESRD in North America,9 but for most patients, presentation and decreased renal function do not occur until the 40s.15 However, patients with the risk factors listed in Table 15,16-19 are likely to experience a more rapid and aggressive form of the disease.

Even with the same germline mutation in a family with this inherited disease, the severity of ADPKD among family members is quite variable; this is true even in the case of twins.9,10,20 Since the age and symptoms at presentation can vary so greatly, a uniform method of identifying patients with ADPKD, along with staging, was needed. Most patients do not undergo genetic testing (ie, DNA linkage or gene-based direct sequencing9) for a diagnosis of ADPKD or to differentiate between the PKD 1 and PKD 2 disease forms unless they are participating in a research study. Diagnostic criteria were needed that were applicable for any type of ADPKD.

In 2009, the University of Toronto’s Division of Nephrology convened experts in the fields of nephrology and radiology to reach a consensus on standardized ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria.21 They formulated definitions based on a study of 948 individuals who were at risk for either PKD 1 or PKD 2 (see Table 221). The specificity and sensitivity of the resulting criteria range from 82% to 100%, making it possible to standardize the care and classification of renal patients worldwide.

Since family members with the same genotypes can experience very divergent disease manifestations, the two-hit hypothesis has been developed.22 In simple terms, it proposes that after the germline mutation (PKD1 or PKD2), there is a second somatic mutation that leads to progressive cyst formation; when the number and size of cysts increase, the patient starts to experience symptoms of ADPKD.22

Age at presentation can be quite variable, as can the presenting symptoms. Most patients with PKD 1 present in their 50s, with 54 being the average age in US patients.14 The most common presenting symptom is flank or back pain.2,5 The pain is due to the massive enlargement of the kidneys, causing a stretching of the kidney capsule and leading to a chronic, dull and persistent pain in the low back. Severe pain, sharp and cutting, occurs when one of the cysts hemorrhages; to some patients, the pain resembles a quick, powerful “kick in the back.” Hematuria can occur following cyst hemorrhage; depending on the location of the cyst that burst within the kidney (ie, how close it is to the collecting system) and how large it is, the amount and color of the hematuria can be impressive.

ADPKD is more common in men than women, and cyst rupture can be precipitated by trauma or lifting heavy objects. Cyst hemorrhage can turn the urine bright red, which is especially frightening to the male patient. Hematuria is often the key presenting symptom in patients who will be diagnosed with ADPKD-induced hypertension.

Besides hematuria, other common manifestations of ADPKD include:

• Hypertension (60% of affected patients, which increases to 100% by the time ESRD develops)

• Extrarenal cysts (100% of affected patients)

• Urinary tract infections

• Nephrolithiasis (20% of affected patients)

• Proteinuria, occasionally (18% of affected patients).2,5,23

Among these manifestations, those most commonly attributed to a diagnosis of ADPKD are hypertension, kidney stones, and urinary tract or kidney infections. Since isolated proteinuria is unusual in patients with ADPKD, it is recommended that another cause of kidney disease be explored in patients with this presentation.24

Extrarenal manifestations of cyst development are common, eventually occurring in all patients as they age. Hepatic cysts are universal in patients with ADPKD by age 30, although hepatic function is preserved. There may be a mild elevation in the alkaline phosphatase level in patients with ADPKD, resulting from the presence of hepatic cysts. Cysts may also be found in the pancreas, spleen, thyroid, and epididymis.5,25 Some patients may complain of dyspnea, pain, early satiety, or lower extremity edema as a result of enlarged cyst.

The Case Patient

Because you recently attended a lecture about ADPKD, you are aware that flank pain in men with hypertension is indicative of ADPKD until proven otherwise. Believing that this patient’s hypertension is renal in origin, you order an abdominal ultrasound. You also order a comprehensive metabolic panel and a complete blood count. The patient’s GFR is measured at 89 mL/min (indicative of stage 2 kidney disease). Other results are shown in Table 3.

The very broad differential includes essential hypertension, hypertension resulting from intake of “power drinks” or salt in an athlete, illicit use of medications (including steroids), herniated disc leading to transient hypertension, and urinary tract infection or sexually transmitted disease. All of this is moot when the ultrasound shows both kidneys measuring greater than 15 cm, with four distinct cysts on the right kidney and three distinct cysts on the left.

You explain to the patient that ADPKD is a genetic disease and that he and his siblings each had a certain chance of inheriting it. Although different presentations may occur (“congenital” polycystic kidney disease, hypertension, or obesity), they all must undergo ultrasonographic screening for ADPKD. You add that although ADPKD is a genetic disease, it can also be diagnosed in different members of the same family at different ages.

TREATMENT

The goal of treatment for the patient with ADPKD is to slow cyst development and the natural course of the disease. If this can be achieved, the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation may be postponed for a number of years. Because cyst growth causes an elevation in renin and activates the angiotensin II renin system26 (see figure,24), an ACE inhibitor is the most effective treatment to lower blood pressure and thus slow the progression of ADPKD. Most patients with ADPKD are started on an ACE inhibitor at an early age to slow the rate of disease progression.27,28 Several studies are under way to determine the best antihypertensive medication and the optimal age for initiating treatment.29,30

Lipid screening and treatment for dyslipidemia are important23 because ADPKD can lead to a reduction in kidney function, resulting in chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent, and most professionals will treat the patient with ADPKD for hyperlipidemia.23,31 While there are no data showing that statin use will reduce the incidence of ESRD or delay the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation in patients with ADPKD, the beneficial effects of good renal blood flow and endothelial function have been noted.32,33

One of the most common and significant complications in ADPKD is intracranial hemorrhage resulting from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. In the younger adult, the incidence of cerebral aneurysm is 4%, but incidence increases to 10% in patients older than 65.34-36 Family clusters of aneurysms have been reported.37 If an intracranial aneurysm is found in the family history, the risk of an aneurysm in another family member increases to 22%.38

Since rupture of an intracranial hemorrhage is associated with a 30-day mortality rate of 50% and 80% morbidity,5,38 standard of care for patients with ADPKD includes CT or magnetic resonance angiographic (MRA) screening in the asymptomatic patient with a positive family history.34,38 If an aneurysm is found, the lifetime chance of rupture is 50%, although the risk is greater in the case of an aneurysm larger than 10 mm.5

As in all patients with kidney disease, left ventricular hypertrophy is common among patients with ADPKD.23,28,39

The Case Patient

The patient is started on an ACE inhibitor, scheduled for fasting lipid screening, and referred to a nephrology practice for disease management. As research and investigation of possible treatment options for ADPKD are ongoing, the patient may benefit from participating in a new research protocol.

Because the patient’s family has no history of cerebral aneurysm, CT/MRA screening is not required. A discussion of the pros and cons of genetic testing for the entire family, including nieces and nephews, is initiated. The patient and his family are referred to a genetic counselor to decide whether the benefit of early treatment for hypertension outweighs the risk of carrying a diagnosis of ADPKD for his younger relatives, who may later seek health insurance coverage.

NATURAL PROGRESSION OF ADPKD

Hypertension and cyst formation will continue as the patient ages. The natural progression of ADPKD is to renal failure with renal replacement therapy (dialysis or organ transplantation) as treatment options. If the progression of ADPKD can be slowed through pharmacotherapy, the patient may live for many years without needing dialysis. This ideal can be accomplished only through aggressive hypertension control, which should be started in the teenage years.23,30,31

Suggestions to increase fluid consumption and to limit the use of NSAIDs, contrast dye, and MRI with gadolinium are appropriate. It is rare for hypertension to be diagnosed before some organ damage has already occurred.12 Often the patient’s renal function, as determined by measuring the GFR, remains stable until the patient reaches his or her 40s.40 However, kidney damage often begins before any detectable change in GFR. Once the GFR does start to decline, the average decrease is 4.4 to 5.9 mL/min/1.73m2 each year.41

MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS

For ESRD Organ Transplantation

Kidney transplantation—the only curative treatment for ADPKD—can be offered to patients once the GFR falls below 20 mL/min. However, the patient with ADPKD can experience kidney enlargement to such an extent that introducing a third kidney into the limited abdominal space becomes technically difficult. Although nephrectomy is avoided whenever possible, there are cases in which there is no alternative.42

In addition to space concerns, recurrent urinary tract infections, chronic pain, renal cell carcinoma, chronic hematuria, or chronic cyst infections can necessitate a nephrectomy.43,44 A laparoscopic approach with decompression of cysts or removal of only one kidney is preferred.43,45 If removal of both kidneys is required before a transplant, the patient must be maintained on dialysis until after transplantation. Since the transplant waiting list can exceed seven years in some areas, most patients arrange for a willing live donor before agreeing to a bilateral nephrectomy.46,47

Dialysis

Either peritoneal dialysis (PD) or hemodialysis (HD) can be offered to patients with severe ADPKD. Depending on the size of the native kidneys and the history of previous abdominal surgery, PD often offers a better chance of survival in these patients, particularly compared with patients who have ESRD associated with other causes.48

For management of the patient with ADPKD who receives PD, it can be difficult to differentiate between the pain of a cyst and the pain of a peritoneal infection. Generally, cyst rupture is accompanied by hematuria; and peritonitis, by cloudy fluid.5 Management provided by an experienced nephrologist and PD nurse is vital.

In ADPKD patients who undergo HD, too, survival is better than in patients who have ESRD with other causes49,50; five-year survival can be as high as 10% to 15%.51 This is likely due to the lower incidence of coronary artery disease in the ADPKD population, compared with patients who have ESRD associated with other chronic diseases.49

FUTURE TRENDS AND ONGOING TRIALS

HALT PKD29,30 is an NIH-funded, double-blind study to determine whether adding an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) to standard ACE inhibitor therapy results in a more significant decrease in the progression of renal cysts. The rationale for this is that the ARB is expected to block the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the kidney. Use of ACE inhibitor monotherapy versus ARB/ACE inhibitor therapy is being compared in two study arms: patients between ages 15 and 49 with a GFR of 60 mL/min or greater; and patients between ages 18 and 64 with a GFR of 25 to 60 mL/min.29 To date, preliminary results indicate no benefit in adding the second medication.49

The TEMPO Trial52 is a multicenter, double-blind study looking at the effect of tolvaptan on renal cyst growth. Tolvaptan is a potent vasopressin receptor antagonist, and in vitro evidence has shown that intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) plays a large role in the development of cysts in patients with ADPKD. If it is possible to block the cAMP that is causing cyst growth, progression of ADPKD should slow.53,54 Only short-term effects of tolvaptan use are currently known.55

High Water Intake to Slow Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease56 is an open-label, nonrandomized trial in which patients drink a minimum of

3 L of water. Previously, a small study showed that an increase in fluid intake partially suppresses the urine osmolality and the serum antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels.57 According to this theory, increasing water intake to greater than 3 L/d may result in complete suppression of ADH and cAMP. This is a small study (n = 20),56 since patients with ADPKD are likely to have urinary concentrating defects, and hyponatremia is a concern is in these patients.58

Sirolimus and ADPKD59 is an open-label randomized study to see whether sirolimus (also known as rapamycin) can reduce cyst growth. Originally, it was noted that posttransplant ADPKD patients underwent a regression of both liver and kidney cysts when they were taking sirolimus, and a preliminary crossover study was done.60 However, preliminary results at 18 months showed no difference in renal growth or cyst growth but did show kidney damage as determined by an increase of proteinuria in the treatment group.59 The study is still in progress.

Somatostatin in Polycystic Kidney61 is a long-term (three-year) study following patients who agreed to participate in a randomized, double-blind protocol; in it, an intramuscular injection of either an octreotide (ie, somatastatin) or placebo was administered every four weeks for one year in an effort to reduce the size of kidney and liver cysts.62 At one year, the quality of life in the treatment group was rated better, as measured by pain reduction and improved physical activity. Cyst growth in the treatment group was smaller for both the kidney and liver. However, the GFR decreased to the same degree in both groups.62

CONCLUSION

ADPKD is a common, often overlooked genetic disease that is a cause of hypertension. ADPKD’s presenting symptoms of flank pain, back pain, and/or hematuria often bring the patient to the provider, but a high index of suspicion must be maintained to diagnose these patients at an early age. Due to the variable presentation even within affected families, many patients do not realize that their family carries the PKD gene.

While genetic testing is available, ultrasound is a quick, relatively inexpensive, and easy method to screen for this diagnosis. The progression of ADPKD to ESRD, requiring dialysis or organ transplantation, can be slowed with early and aggressive treatment of hypertension. As with all patients affected by renal impairment, suggestions for patients with ADPKD to avoid use of NSAIDs, contrast dye, and gadolinium-enhanced MRI are appropriate. The primary care PA or NP is in an appropriate position to see to this.

REFERENCES

1. Newschaffer CJ, Falb MD, Gurney JG. National autism prevalence trends from United States special education data. Pediatrics. 2005;115 (3):e277-e282.

2. Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1287-1301.

3. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene encodes a 14 kb transcript and lies within a duplicated region on chromosome 16: European Polycystic Kidney Disease Consortium. Cell. 1994;77(6):881-894.

4. Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996; 272(5266):1339-1342.

5. Chapman AB. Polycystic and other cystic kidney diseases. In: Greenberg A, ed. Primer on Kidney Diseases: Expert Consult. 5th ed. National Kidney Foundation; 2009:345-353.

6. Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, et al. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):21-23.

7. Murcia NS, Sweeney WE Jr, Avner ED. New insights into the molecular pathophysiology of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1999;55 (4):1187-1197.

8. Paterson AD, Pei Y. Is there a third gene for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? Kidney Int. 1998;54(5):1759-1761.

9. Pei Y. Practical genetics for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118(1):c19-c30.

10. Tan YC, Blumenfeld J, Rennert H. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: genetics, mutations and microRNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011 Mar 16 [Epub ahead of print].

11. Avner ED, Sweeney WE Jr, Nelson WJ. Abnormal sodium pump distribution during renal tubulogenesis in congenital murine polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(16):7447-7451.

12. Torra R, Badenas C, Darnell A, et al. Linkage, clinical features, and prognosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(10):2142-2151.

13. Davies F, Coles GA, Harper PS, et al. Polycystic kidney disease re-evaluated: a population-based study. Q J Med. 1991;79(290):477-485.

14. Hateboer N, v Dijk MA, Bogdanova N, et al; European PKD1-PKD2 Study Group. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):103-107.

15. Peters DJ, Breuning MH. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: modification of disease progression. Lancet. 2001;358(9291):1439-1444.

16. Dicks E, Ravani P, Langman D, et al. Incident renal events and risk factors in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population- and family-based cohort followed for 22 years. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(4):710-717.

17. Fick-Brosnahan GM, Belz MM, McFann KK, etc. Relationship between renal volume growth and renal function in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a longitudinal study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(6):1127-1134.

18. Fick-Brosnahan GM, Tran ZV, Johnson AM, et al. Progression of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in children. Kidney Int. 2001;59(5):1654-1662.

19. Johnson AM, Gabow PA. Identification of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease at highest risk for end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(10): 1560-1567.

20. Risk D. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Presented at: National Kidney Foundation, Spring Clinical Meetings; April 28, 2011; Las Vegas, NV.

21. Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A, et al. Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(1):205-212.

22. Watnick T, Germino GG. Molecular basis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 1999;19(4):327-343.

23. Ecder T, Schrier RW. Cardiovascular abnormalities in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(4):221-228.

24. Patch C, Charlton J, Roderick PJ, Gulliford MC. Use of antihypertensive medications and mortality of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a population-based study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(6):856-862.

25. Pirson Y. Extrarenal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(2):173-180.

26. Chapman AB, Johnson A, Gabow PA, Schrier RW. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(16):1091-1096.

27. Jafar TH, Stark PC, Schmid CH, et al. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors on progression of advanced polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;67(1):265-271.

28. Schrier RW. Renal volume, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, hypertension, and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(9):1888-1893.

29. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), NIH, sponsor. HALT PKD (Halt Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease): Efficacy of Aggressive Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Axis Blockade in Preventing/Slowing Renal Function Decline in ADPKD. www2.niddk.nih.gov/NR/rdonlyres/175578F6-62B4-429A-9BBF-96CCEC2FFB3A/0/KUHHALT PKDPROTOCOL9107.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2011.

30. Chapman AB, Torres VE, Perrone RD, et al. The HALT polycystic kidney disease trials: design and implementation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(1):102-109.

31. Taylor M, Johnson AM, Tison M, et al. Earlier diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: importance of family history and implications for cardiovascular and renal complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(3):415-423.

32. Namli S, Oflaz H, Turgut F, et al. Improvement of endothelial dysfunction with simvastatin in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2007;29(1):55-59.

33. Bremmer MS, Jacobs SC. Renal artery embolization for the symptomatic treatment of adult polycystic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4(5):236-237.

34. Chapman AB, Rubinstein D, Hughes R, et al. Intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1992; 327(13):916-920.

35. Schievink WI, Torres VE, Piepgras DG, Wiebers DO. Saccular intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;3(1):88-95.

36. Fick GM, Gabow PA. Hereditary and acquired cystic disease of the kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;46(4):951-964.

37. Watson ML. Complications of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 1997;51(1):353-365.

38. Huston J 3rd, Torres VE, Sulivan PP, et al. Value of magnetic resonance angiography for the detection of intracranial aneurysms in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(12):1871-1877.

39. Longenecker JC, Coresh J, Powe NR, et al. Traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in dialysis patients compared with the general population: the CHOICE Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(7):1918-1927.

40. Meijer E, Rook M, Tent H, et al. Early renal abnormalities in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010; 5(6):1091-1098.

41. Torres VE, Harris PC. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the last 3 years. Kidney Int. 2009;76(2):149-168.

42. Tabibi A, Simforoosh N, Abadpour P, et al. Concomitant nephrectomy of massively enlarged kidneys and renal transplantation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(7):2939-2940.

43. Dunn MD, Portis AJ, Elbahnasy AM, et al. Laparoscopic nephrectomy in patients with end-stage renal disease and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(4):720-725.

44. Sulikowski T, Tejchman K, Zietek Z, et al. Experience with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in patients before and after renal transplantation: a 7-year observation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(1):177-180.

45. Desai MR, Nandkishore SK, Ganpule A, Thimmegowda M. Pretransplant laparoscopic nephrectomy in adult polycystic kidney disease: a single centre experience. BJU Int. 2008;101 (1):94-97.

46. Glassman DT, Nipkow L, Bartlett ST, Jacobs SC. Bilateral nephrectomy with concomitant renal graft transplantation for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Urol. 2000;164 (3 pt 1):661-664.

47. Fuller TF, Brennan TV, Feng S, et al. End stage polycystic kidney disease: indications and timing of native nephrectomy relative to kidney transplantation. J Urol. 2005;174(6):2284-2288.

48. Abbott KC, Agodoa LY. Polycystic kidney disease at end-stage renal disease in the United States: patient characteristics and survival. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57(3):208-214.

49. Perrone RD, Ruthazer R, Terrin NC. Survival after end-stage renal disease in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: contribution of extrarenal complications to mortality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38(4):777-784.