User login

Early menopause, delayed HT tied to Alzheimer’s pathology

Investigators found elevated levels of tau protein in the brains of women who initiated HT more than 5 years after menopause onset, while those who started the therapy earlier had normal levels.

Tau levels were also higher in women who started menopause before age 45, either naturally or following surgery, but only in those who already had high levels of beta-amyloid.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Hotly debated

Previous research has suggested the timing of menopause and HT initiation may be associated with AD. However, the current research is the first to suggest tau deposition may explain that link.

“There have been a lot of conflicting findings around whether HT induces risk for Alzheimer’s disease dementia or not, and – at least in our hands – our observational evidence suggests that any risk is fairly limited to those rarer cases when women might delay their initiation of HT considerably,” senior investigator Rachel Buckley, PhD, assistant investigator in neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

The link between HT, dementia, and cognitive decline has been hotly debated since the initial release of findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study, reported 20 years ago.

Since then, dozens of studies have yielded conflicting evidence about HT and AD risk, with some showing a protective effect and others showing the treatment may increase AD risk.

For this study, researchers analyzed data from 292 cognitively unimpaired participants (66.1% female) in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer Prevention. About half of the women had received HT.

Women had higher levels of tau measured on PET imaging than age-matched males, even after adjustment for APOE status and other potential confounders.

Higher tau levels were found in those with an earlier age at menopause (P < .001) and HT use (P = .008) compared with male sex; later menopause onset; or HT nonuse – but only in patients who also had a higher beta-amyloid burden.

Late initiation of HT (> 5 years following age at menopause) was associated with higher tau compared with early initiation (P = .001), regardless of amyloid levels.

Surprising finding

Although researchers expected to find that surgical history (specifically oophorectomy) might have a greater impact on risk, that wasn’t the case.

“Given that bilateral oophorectomy involves the removal of both ovaries, and the immediate ceasing of estrogen production, I had expected this to be the primary driver of higher tau levels,” Dr. Buckley said. “But early age at menopause – regardless of whether the genesis was natural or surgical – seemed to have similar impacts.”

These findings are the latest from Dr. Buckley’s group that indicate that women tend to have higher levels of tau than men, regardless of preexisting amyloid burden in the brain.

“We see this in healthy older women, women with dementia, and even in postmortem cases,” Dr. Buckley said. “It really remains to be seen whether women tend to accumulate tau faster in the brain than men, or whether this is simply a one-shot phenomenon that we see in observational studies at the baseline.”

“One could really flip this finding on its head and suggest that women are truly resilient to the disease,” she continued. “That is, they can hold much more tau in their brain and remain well enough to be studied, unlike men.”

Among the study’s limitations is that the data were collected at a single time point and did not include information on subsequent Alzheimer’s diagnosis or cognitive decline.

“It is important to remember that the participants in this study were not as representative of the general population in the United States, so we cannot extrapolate our findings to women from a range of socioeconomic, racial and ethnic backgrounds or education levels,” she said.

The study’s observational design left researchers unable to demonstrate causation. What’s more, the findings don’t support the assertion that hormone therapy may protect against AD, Dr. Buckley added.

“I would more confidently say that evidence from our work, and that of many others, seems to suggest that HT initiated around the time of menopause may be benign – not providing benefit or risk, at least in the context of Alzheimer’s disease risk,” she said.

Another important takeaway from the study, Dr. Buckley said, is that not all women are at high risk for AD.

“Often the headlines might make you think that most women are destined to progress to dementia, but this simply is not the case,” Dr. Buckley said. “We are now starting to really drill down on what might elevate risk for AD in women and use this information to better inform clinical trials and doctors on how best to think about treating these higher-risk groups.”

New mechanism?

Commenting on the findings, Pauline Maki, PhD, professor of psychiatry, psychology and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, called the study “interesting.”

“It identifies a new mechanism in humans that could underlie a possible link between sex hormones and dementia,” Dr. Maki said.

However, Dr. Maki noted that the study wasn’t randomized and information about menopause onset was self-reported.

“We must remember that many of the hypotheses about hormone therapy and brain health that came from observational studies were not validated in randomized trials, including the hypothesis that hormone therapy prevents dementia,” she said.

The findings don’t resolve the debate over hormone therapy and AD risk and point to the need for randomized, prospective studies on the topic, Dr. Maki added. Still, she said, they underscore the gender disparity in AD risk.

“It’s a good reminder to clinicians that women have a higher lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s disease and should be advised on factors that might lower their risk,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Buckley reports no relevant financial conflicts. Dr. Maki serves on the advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, consults for Pfizer and Mithra, and has equity in Estrigenix, Midi-Health, and Alloy.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found elevated levels of tau protein in the brains of women who initiated HT more than 5 years after menopause onset, while those who started the therapy earlier had normal levels.

Tau levels were also higher in women who started menopause before age 45, either naturally or following surgery, but only in those who already had high levels of beta-amyloid.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Hotly debated

Previous research has suggested the timing of menopause and HT initiation may be associated with AD. However, the current research is the first to suggest tau deposition may explain that link.

“There have been a lot of conflicting findings around whether HT induces risk for Alzheimer’s disease dementia or not, and – at least in our hands – our observational evidence suggests that any risk is fairly limited to those rarer cases when women might delay their initiation of HT considerably,” senior investigator Rachel Buckley, PhD, assistant investigator in neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

The link between HT, dementia, and cognitive decline has been hotly debated since the initial release of findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study, reported 20 years ago.

Since then, dozens of studies have yielded conflicting evidence about HT and AD risk, with some showing a protective effect and others showing the treatment may increase AD risk.

For this study, researchers analyzed data from 292 cognitively unimpaired participants (66.1% female) in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer Prevention. About half of the women had received HT.

Women had higher levels of tau measured on PET imaging than age-matched males, even after adjustment for APOE status and other potential confounders.

Higher tau levels were found in those with an earlier age at menopause (P < .001) and HT use (P = .008) compared with male sex; later menopause onset; or HT nonuse – but only in patients who also had a higher beta-amyloid burden.

Late initiation of HT (> 5 years following age at menopause) was associated with higher tau compared with early initiation (P = .001), regardless of amyloid levels.

Surprising finding

Although researchers expected to find that surgical history (specifically oophorectomy) might have a greater impact on risk, that wasn’t the case.

“Given that bilateral oophorectomy involves the removal of both ovaries, and the immediate ceasing of estrogen production, I had expected this to be the primary driver of higher tau levels,” Dr. Buckley said. “But early age at menopause – regardless of whether the genesis was natural or surgical – seemed to have similar impacts.”

These findings are the latest from Dr. Buckley’s group that indicate that women tend to have higher levels of tau than men, regardless of preexisting amyloid burden in the brain.

“We see this in healthy older women, women with dementia, and even in postmortem cases,” Dr. Buckley said. “It really remains to be seen whether women tend to accumulate tau faster in the brain than men, or whether this is simply a one-shot phenomenon that we see in observational studies at the baseline.”

“One could really flip this finding on its head and suggest that women are truly resilient to the disease,” she continued. “That is, they can hold much more tau in their brain and remain well enough to be studied, unlike men.”

Among the study’s limitations is that the data were collected at a single time point and did not include information on subsequent Alzheimer’s diagnosis or cognitive decline.

“It is important to remember that the participants in this study were not as representative of the general population in the United States, so we cannot extrapolate our findings to women from a range of socioeconomic, racial and ethnic backgrounds or education levels,” she said.

The study’s observational design left researchers unable to demonstrate causation. What’s more, the findings don’t support the assertion that hormone therapy may protect against AD, Dr. Buckley added.

“I would more confidently say that evidence from our work, and that of many others, seems to suggest that HT initiated around the time of menopause may be benign – not providing benefit or risk, at least in the context of Alzheimer’s disease risk,” she said.

Another important takeaway from the study, Dr. Buckley said, is that not all women are at high risk for AD.

“Often the headlines might make you think that most women are destined to progress to dementia, but this simply is not the case,” Dr. Buckley said. “We are now starting to really drill down on what might elevate risk for AD in women and use this information to better inform clinical trials and doctors on how best to think about treating these higher-risk groups.”

New mechanism?

Commenting on the findings, Pauline Maki, PhD, professor of psychiatry, psychology and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, called the study “interesting.”

“It identifies a new mechanism in humans that could underlie a possible link between sex hormones and dementia,” Dr. Maki said.

However, Dr. Maki noted that the study wasn’t randomized and information about menopause onset was self-reported.

“We must remember that many of the hypotheses about hormone therapy and brain health that came from observational studies were not validated in randomized trials, including the hypothesis that hormone therapy prevents dementia,” she said.

The findings don’t resolve the debate over hormone therapy and AD risk and point to the need for randomized, prospective studies on the topic, Dr. Maki added. Still, she said, they underscore the gender disparity in AD risk.

“It’s a good reminder to clinicians that women have a higher lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s disease and should be advised on factors that might lower their risk,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Buckley reports no relevant financial conflicts. Dr. Maki serves on the advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, consults for Pfizer and Mithra, and has equity in Estrigenix, Midi-Health, and Alloy.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found elevated levels of tau protein in the brains of women who initiated HT more than 5 years after menopause onset, while those who started the therapy earlier had normal levels.

Tau levels were also higher in women who started menopause before age 45, either naturally or following surgery, but only in those who already had high levels of beta-amyloid.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Hotly debated

Previous research has suggested the timing of menopause and HT initiation may be associated with AD. However, the current research is the first to suggest tau deposition may explain that link.

“There have been a lot of conflicting findings around whether HT induces risk for Alzheimer’s disease dementia or not, and – at least in our hands – our observational evidence suggests that any risk is fairly limited to those rarer cases when women might delay their initiation of HT considerably,” senior investigator Rachel Buckley, PhD, assistant investigator in neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, told this news organization.

The link between HT, dementia, and cognitive decline has been hotly debated since the initial release of findings from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study, reported 20 years ago.

Since then, dozens of studies have yielded conflicting evidence about HT and AD risk, with some showing a protective effect and others showing the treatment may increase AD risk.

For this study, researchers analyzed data from 292 cognitively unimpaired participants (66.1% female) in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer Prevention. About half of the women had received HT.

Women had higher levels of tau measured on PET imaging than age-matched males, even after adjustment for APOE status and other potential confounders.

Higher tau levels were found in those with an earlier age at menopause (P < .001) and HT use (P = .008) compared with male sex; later menopause onset; or HT nonuse – but only in patients who also had a higher beta-amyloid burden.

Late initiation of HT (> 5 years following age at menopause) was associated with higher tau compared with early initiation (P = .001), regardless of amyloid levels.

Surprising finding

Although researchers expected to find that surgical history (specifically oophorectomy) might have a greater impact on risk, that wasn’t the case.

“Given that bilateral oophorectomy involves the removal of both ovaries, and the immediate ceasing of estrogen production, I had expected this to be the primary driver of higher tau levels,” Dr. Buckley said. “But early age at menopause – regardless of whether the genesis was natural or surgical – seemed to have similar impacts.”

These findings are the latest from Dr. Buckley’s group that indicate that women tend to have higher levels of tau than men, regardless of preexisting amyloid burden in the brain.

“We see this in healthy older women, women with dementia, and even in postmortem cases,” Dr. Buckley said. “It really remains to be seen whether women tend to accumulate tau faster in the brain than men, or whether this is simply a one-shot phenomenon that we see in observational studies at the baseline.”

“One could really flip this finding on its head and suggest that women are truly resilient to the disease,” she continued. “That is, they can hold much more tau in their brain and remain well enough to be studied, unlike men.”

Among the study’s limitations is that the data were collected at a single time point and did not include information on subsequent Alzheimer’s diagnosis or cognitive decline.

“It is important to remember that the participants in this study were not as representative of the general population in the United States, so we cannot extrapolate our findings to women from a range of socioeconomic, racial and ethnic backgrounds or education levels,” she said.

The study’s observational design left researchers unable to demonstrate causation. What’s more, the findings don’t support the assertion that hormone therapy may protect against AD, Dr. Buckley added.

“I would more confidently say that evidence from our work, and that of many others, seems to suggest that HT initiated around the time of menopause may be benign – not providing benefit or risk, at least in the context of Alzheimer’s disease risk,” she said.

Another important takeaway from the study, Dr. Buckley said, is that not all women are at high risk for AD.

“Often the headlines might make you think that most women are destined to progress to dementia, but this simply is not the case,” Dr. Buckley said. “We are now starting to really drill down on what might elevate risk for AD in women and use this information to better inform clinical trials and doctors on how best to think about treating these higher-risk groups.”

New mechanism?

Commenting on the findings, Pauline Maki, PhD, professor of psychiatry, psychology and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, called the study “interesting.”

“It identifies a new mechanism in humans that could underlie a possible link between sex hormones and dementia,” Dr. Maki said.

However, Dr. Maki noted that the study wasn’t randomized and information about menopause onset was self-reported.

“We must remember that many of the hypotheses about hormone therapy and brain health that came from observational studies were not validated in randomized trials, including the hypothesis that hormone therapy prevents dementia,” she said.

The findings don’t resolve the debate over hormone therapy and AD risk and point to the need for randomized, prospective studies on the topic, Dr. Maki added. Still, she said, they underscore the gender disparity in AD risk.

“It’s a good reminder to clinicians that women have a higher lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s disease and should be advised on factors that might lower their risk,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Buckley reports no relevant financial conflicts. Dr. Maki serves on the advisory boards for Astellas, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, consults for Pfizer and Mithra, and has equity in Estrigenix, Midi-Health, and Alloy.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Obstructive sleep apnea linked to early cognitive decline

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study out of King’s College London, participants with severe OSA experienced worse executive functioning as well as social and emotional recognition versus healthy controls.

Major risk factors for OSA include obesity, high blood pressure, smoking, high cholesterol, and being middle-aged or older. Because some researchers have hypothesized that cognitive deficits could be driven by such comorbidities, the study investigators recruited middle-aged men with no medical comorbidities.

“Traditionally, we were more concerned with sleep apnea’s metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities, and indeed, when cognitive deficits were demonstrated, most were attributed to them, and yet, our patients and their partners/families commonly tell us differently,” lead investigator Ivana Rosenzweig, MD, PhD, of King’s College London, who is also a consultant in sleep medicine and neuropsychiatry at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, said in an interview.

“Our findings provide a very important first step towards challenging the long-standing dogma that sleep apnea has little to do with the brain – apart from causing sleepiness – and that it is a predominantly nonneuro/psychiatric illness,” added Dr. Rosenzweig.

The findings were published online in Frontiers in Sleep.

Brain changes

The researchers wanted to understand how OSA may be linked to cognitive decline in the absence of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions.

To accomplish this, the investigators studied 27 men between the ages of 35 and 70 with a new diagnosis of mild to severe OSA without any comorbidities (16 with mild OSA and 11 with severe OSA). They also studied a control group of seven men matched for age, body mass index, and education level.

The team tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and found that the most significant deficits for the OSA group, compared with controls, were in areas of visual matching ability (P < .0001), short-term visual recognition memory, nonverbal patterns, executive functioning and attentional set-shifting (P < .001), psychomotor functioning, and social cognition and emotional recognition (P < .05).

On the latter two tests, impaired participants were less likely to accurately identify the emotion on computer-generated faces. Those with mild OSA performed better than those with severe OSA on these tasks, but rarely worse than controls.

Dr. Rosenzweig noted that the findings were one-of-a-kind because of the recruitment of patients with OSA who were otherwise healthy and nonobese, “something one rarely sees in the sleep clinic, where we commonly encounter patients with already developed comorbidities.

“In order to truly revolutionize the treatment for our patients, it is important to understand how much the accompanying comorbidities, such as systemic hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other various serious cardiovascular and metabolic diseases and how much the illness itself may shape the demonstrated cognitive deficits,” she said.

She also said that “it is widely agreed that medical problems in middle age may predispose to increased prevalence of dementia in later years.

Moreover, the very link between sleep apnea and Alzheimer’s, vascular and mixed dementia is increasingly demonstrated,” said Dr. Rosenzweig.

Although women typically have a lower prevalence of OSA than men, Dr. Rosenzweig said women were not included in the study “because we are too complex. As a lifelong feminist it pains me to say this, but to get any authoritative answer on our physiology, we need decent funding in place so that we can take into account all the intricacies of the changes of our sleep, physiology, and metabolism.

“While there is always lots of noise about how important it is to answer these questions, there are only very limited funds available for the sleep research,” she added.

Dr. Rosenzweig’s future research will focus on the potential link between OSA and neuroinflammation.

In a comment, Liza Ashbrook, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, said the findings “add to the growing list of negative health consequences associated with sleep apnea.”

She said that, if the cognitive changes found in the study are, in fact, caused by OSA, it is unclear whether they are the beginning of long-term cognitive changes or a symptom of fragmented sleep that may be reversible.

Dr. Ashbrook said she would be interested in seeing research on understanding the effect of OSA treatment on the affected cognitive domains.

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust. No relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN SLEEP

Food insecurity linked to more rapid cognitive decline in seniors

Food insecurity is linked to a more rapid decline in executive function in older adults, a new study shows.

The findings were reported just weeks after a pandemic-era expansion in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits ended, leading to less food assistance for about 5 million people over age 60 who participate in the program.

“Even though we found only a very small association between food insecurity and executive function, it’s still meaningful, because food insecurity is something we can prevent,” lead investigator Boeun Kim, PhD, MPH, RN, postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

National data

The number of Americans over 60 with food insecurity has more than doubled since 2007, with an estimated 5.2 million older adults reporting food insecurity in 2020.

Prior studies have linked malnutrition and food insecurity to a decline in cognitive function. Participating in food assistance programs such as SNAP is associated with slower memory decline in older adults.

However, to date, there has been no longitudinal study that has used data from a nationally representative sample of older Americans, which, Dr. Kim said, could limit generalizability of the findings.

To address that issue, investigators analyzed data from 3,037 participants in the National Health and Aging Trends Study, which includes community dwellers age 65 and older who receive Medicare.

Participants reported food insecurity over 7 years, from 2012 to 2019. Data on immediate memory, delayed memory, and executive function were from 2013 to 2020.

Food insecurity was defined as going without groceries due to limited ability or social support; a lack of hot meals related to functional limitation or no help; going without eating because of the inability to feed oneself or no available support; skipping meals due to insufficient food or money; or skipping meals for 5 days or more.

Immediate and delayed recall were assessed using a 10-item word-list memory task, and executive function was measured using a clock drawing test. Each year’s cognitive functions were linked to the prior year’s food insecurity data.

Over 7 years, 417 people, or 12.1%, experienced food insecurity at least once.

Those with food insecurity were more likely to be older, female, part of racial and ethnic minority groups, living alone, obese, and have a lower income and educational attainment, depressive symptoms, social isolation and disability, compared with those without food insecurity.

After adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, income, marital status, body mass index, functional disability, social isolation, and other potential confounders, researchers found that food insecurity was associated with a more rapid decline in executive function (mean difference in annual change in executive function score, −0.04; 95% confidence interval, −0.09 to −0.003).

Food insecurity was not associated with baseline cognitive function scores or changes in immediate or delayed recall.

“Clinicians should be aware of the experience of food insecurity and the higher risk of cognitive decline so maybe they could do universal screening and refer people with food insecurity to programs that can help them access nutritious meals,” Dr. Kim said.

A sign of other problems?

Thomas Vidic, MD, said food insecurity often goes hand-in-hand with lack of medication adherence, lack of regular medical care, and a host of other issues. Dr. Vidic is a neurologist at the Elkhart Clinic, Ind., and an adjunct clinical professor of neurology at Indiana University.

“When a person has food insecurity, they likely have other problems, and they’re going to degenerate faster,” said Dr. Vidic, who was not part of the study. “This is one important component, and it’s one more way of getting a handle on people who are failing.”

Dr. Vidic, who has dealt with the issue of food insecurity with his own patients, said he suspects the self-report nature of the study may hide the true scale of the problem.

“I suspect the numbers might actually be higher,” he said, adding that the study fills a gap in the literature with a large, nationally representative sample.

“We’re looking for issues to help with the elderly as far as what can we do to keep dementia from progressing,” he said. “There are some things that make sense, but we’ve never had this kind of data before.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kim and Dr. Vidic have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Food insecurity is linked to a more rapid decline in executive function in older adults, a new study shows.

The findings were reported just weeks after a pandemic-era expansion in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits ended, leading to less food assistance for about 5 million people over age 60 who participate in the program.

“Even though we found only a very small association between food insecurity and executive function, it’s still meaningful, because food insecurity is something we can prevent,” lead investigator Boeun Kim, PhD, MPH, RN, postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

National data

The number of Americans over 60 with food insecurity has more than doubled since 2007, with an estimated 5.2 million older adults reporting food insecurity in 2020.

Prior studies have linked malnutrition and food insecurity to a decline in cognitive function. Participating in food assistance programs such as SNAP is associated with slower memory decline in older adults.

However, to date, there has been no longitudinal study that has used data from a nationally representative sample of older Americans, which, Dr. Kim said, could limit generalizability of the findings.

To address that issue, investigators analyzed data from 3,037 participants in the National Health and Aging Trends Study, which includes community dwellers age 65 and older who receive Medicare.

Participants reported food insecurity over 7 years, from 2012 to 2019. Data on immediate memory, delayed memory, and executive function were from 2013 to 2020.

Food insecurity was defined as going without groceries due to limited ability or social support; a lack of hot meals related to functional limitation or no help; going without eating because of the inability to feed oneself or no available support; skipping meals due to insufficient food or money; or skipping meals for 5 days or more.

Immediate and delayed recall were assessed using a 10-item word-list memory task, and executive function was measured using a clock drawing test. Each year’s cognitive functions were linked to the prior year’s food insecurity data.

Over 7 years, 417 people, or 12.1%, experienced food insecurity at least once.

Those with food insecurity were more likely to be older, female, part of racial and ethnic minority groups, living alone, obese, and have a lower income and educational attainment, depressive symptoms, social isolation and disability, compared with those without food insecurity.

After adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, income, marital status, body mass index, functional disability, social isolation, and other potential confounders, researchers found that food insecurity was associated with a more rapid decline in executive function (mean difference in annual change in executive function score, −0.04; 95% confidence interval, −0.09 to −0.003).

Food insecurity was not associated with baseline cognitive function scores or changes in immediate or delayed recall.

“Clinicians should be aware of the experience of food insecurity and the higher risk of cognitive decline so maybe they could do universal screening and refer people with food insecurity to programs that can help them access nutritious meals,” Dr. Kim said.

A sign of other problems?

Thomas Vidic, MD, said food insecurity often goes hand-in-hand with lack of medication adherence, lack of regular medical care, and a host of other issues. Dr. Vidic is a neurologist at the Elkhart Clinic, Ind., and an adjunct clinical professor of neurology at Indiana University.

“When a person has food insecurity, they likely have other problems, and they’re going to degenerate faster,” said Dr. Vidic, who was not part of the study. “This is one important component, and it’s one more way of getting a handle on people who are failing.”

Dr. Vidic, who has dealt with the issue of food insecurity with his own patients, said he suspects the self-report nature of the study may hide the true scale of the problem.

“I suspect the numbers might actually be higher,” he said, adding that the study fills a gap in the literature with a large, nationally representative sample.

“We’re looking for issues to help with the elderly as far as what can we do to keep dementia from progressing,” he said. “There are some things that make sense, but we’ve never had this kind of data before.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kim and Dr. Vidic have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Food insecurity is linked to a more rapid decline in executive function in older adults, a new study shows.

The findings were reported just weeks after a pandemic-era expansion in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits ended, leading to less food assistance for about 5 million people over age 60 who participate in the program.

“Even though we found only a very small association between food insecurity and executive function, it’s still meaningful, because food insecurity is something we can prevent,” lead investigator Boeun Kim, PhD, MPH, RN, postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, told this news organization.

The findings were published online in JAMA Network Open.

National data

The number of Americans over 60 with food insecurity has more than doubled since 2007, with an estimated 5.2 million older adults reporting food insecurity in 2020.

Prior studies have linked malnutrition and food insecurity to a decline in cognitive function. Participating in food assistance programs such as SNAP is associated with slower memory decline in older adults.

However, to date, there has been no longitudinal study that has used data from a nationally representative sample of older Americans, which, Dr. Kim said, could limit generalizability of the findings.

To address that issue, investigators analyzed data from 3,037 participants in the National Health and Aging Trends Study, which includes community dwellers age 65 and older who receive Medicare.

Participants reported food insecurity over 7 years, from 2012 to 2019. Data on immediate memory, delayed memory, and executive function were from 2013 to 2020.

Food insecurity was defined as going without groceries due to limited ability or social support; a lack of hot meals related to functional limitation or no help; going without eating because of the inability to feed oneself or no available support; skipping meals due to insufficient food or money; or skipping meals for 5 days or more.

Immediate and delayed recall were assessed using a 10-item word-list memory task, and executive function was measured using a clock drawing test. Each year’s cognitive functions were linked to the prior year’s food insecurity data.

Over 7 years, 417 people, or 12.1%, experienced food insecurity at least once.

Those with food insecurity were more likely to be older, female, part of racial and ethnic minority groups, living alone, obese, and have a lower income and educational attainment, depressive symptoms, social isolation and disability, compared with those without food insecurity.

After adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, income, marital status, body mass index, functional disability, social isolation, and other potential confounders, researchers found that food insecurity was associated with a more rapid decline in executive function (mean difference in annual change in executive function score, −0.04; 95% confidence interval, −0.09 to −0.003).

Food insecurity was not associated with baseline cognitive function scores or changes in immediate or delayed recall.

“Clinicians should be aware of the experience of food insecurity and the higher risk of cognitive decline so maybe they could do universal screening and refer people with food insecurity to programs that can help them access nutritious meals,” Dr. Kim said.

A sign of other problems?

Thomas Vidic, MD, said food insecurity often goes hand-in-hand with lack of medication adherence, lack of regular medical care, and a host of other issues. Dr. Vidic is a neurologist at the Elkhart Clinic, Ind., and an adjunct clinical professor of neurology at Indiana University.

“When a person has food insecurity, they likely have other problems, and they’re going to degenerate faster,” said Dr. Vidic, who was not part of the study. “This is one important component, and it’s one more way of getting a handle on people who are failing.”

Dr. Vidic, who has dealt with the issue of food insecurity with his own patients, said he suspects the self-report nature of the study may hide the true scale of the problem.

“I suspect the numbers might actually be higher,” he said, adding that the study fills a gap in the literature with a large, nationally representative sample.

“We’re looking for issues to help with the elderly as far as what can we do to keep dementia from progressing,” he said. “There are some things that make sense, but we’ve never had this kind of data before.”

The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Kim and Dr. Vidic have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Self-fitted and audiologist-fitted hearing aids equal for mild to moderate hearing loss

Self-fitted over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids may be an effective option for individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss, a small randomized effectiveness trial reports. OTC devices yielded 6-week patient-perceived and clinical outcomes comparable to those with audiologist-fitted hearing aids, In fact, at week 2, the self-fitted group had a small but meaningful advantage on two of the four study outcome measures.

“After support and fine-tuning were provided to the self-fitting (remote support) and audiologist-fitted groups, no clinically meaningful differences were evident in any outcome measures at the end of the 6-week trial,” wrote researchers led by Karina C. De Sousa, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of speech-language pathology and audiology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Their findings appear in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Hearing aid uptake is low even in populations with adequate access to audiological resources, the authors noted, with hearing aid use in U.S. adults who could benefit estimated at about 20%. Currently, an estimated 22.9 million older Americans with audiometric hearing loss do not use hearing aids.

Major barriers have been access and affordability, Dr. De Sousa and associates wrote, and until recently, people with hearing loss could obtain hearing aids only after consultation with a credentialed dispenser. “The World Health Organization estimates that over 2.5 billion people will experience some degree of hearing loss by 2050,” Dr. De Sousa said in an interview. “This new category of self-fitting hearing aids opens up newer care pathways for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.”

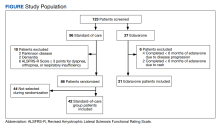

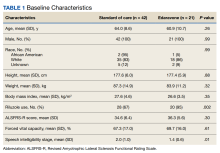

The study

From April to August 2022 the trial recruited 68 participants (51.6% men) with mild-to-moderate self-reported hearing loss, a mean age of 63.6 years, and no ear disease within the past 90 days. They were randomized to a self-fitted commercially available device (Lexi Lumen), with instructional material on set-up and remote support, or to the same unit fitted by an audiologist. The majority in both arms were new users and were similar in age and baseline hearing scores.

The primary outcome measure was patient-reported hearing aid benefit, measured by the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. This scale evaluates auditory acuity before and after amplification by such criteria as ease of communication, background noise, reverberation, aversiveness, and global hearing status.

Secondary measures included the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) and speech recognition in noise measured using an abbreviated speech-in-noise test and a digits-in-noise test. Measures were taken at baseline, week 2, and week 6 after fitting. After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting arm had an initial advantage on the self-reported APHAB: difference, Cohen d = −.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 0). It also fared better on the IOI-HA: effect size, r = 0.3 (95% CI, .0 to –.5), but not on speech recognition in noise.

One member of the self-fitting arm withdrew owing to an unrelated middle-ear infection.

“While these results are promising, it is essential to note that OTC hearing aids are not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dr. De Sousa said. “If a person has ear disease symptoms or hearing loss that is too severe, they have to consult a trained hearing health care professional.” She added that proper use of a self-fitted OTC hearing aid requires a degree of digital proficiency, as many devices are set up using a smartphone.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and by the hearX Group, which provided the Lexie Lumen devices and software support for data collection. Dr. De Sousa reported nonfinancial support from hearX as well as consulting fees from hearX outside of the submitted work. A coauthor reported grant support from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and fees from hearX during and outside of the study. Another coauthor disclosed fees, equity, and grant support from hearX during the conduct of the study.

Self-fitted over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids may be an effective option for individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss, a small randomized effectiveness trial reports. OTC devices yielded 6-week patient-perceived and clinical outcomes comparable to those with audiologist-fitted hearing aids, In fact, at week 2, the self-fitted group had a small but meaningful advantage on two of the four study outcome measures.

“After support and fine-tuning were provided to the self-fitting (remote support) and audiologist-fitted groups, no clinically meaningful differences were evident in any outcome measures at the end of the 6-week trial,” wrote researchers led by Karina C. De Sousa, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of speech-language pathology and audiology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Their findings appear in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Hearing aid uptake is low even in populations with adequate access to audiological resources, the authors noted, with hearing aid use in U.S. adults who could benefit estimated at about 20%. Currently, an estimated 22.9 million older Americans with audiometric hearing loss do not use hearing aids.

Major barriers have been access and affordability, Dr. De Sousa and associates wrote, and until recently, people with hearing loss could obtain hearing aids only after consultation with a credentialed dispenser. “The World Health Organization estimates that over 2.5 billion people will experience some degree of hearing loss by 2050,” Dr. De Sousa said in an interview. “This new category of self-fitting hearing aids opens up newer care pathways for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.”

The study

From April to August 2022 the trial recruited 68 participants (51.6% men) with mild-to-moderate self-reported hearing loss, a mean age of 63.6 years, and no ear disease within the past 90 days. They were randomized to a self-fitted commercially available device (Lexi Lumen), with instructional material on set-up and remote support, or to the same unit fitted by an audiologist. The majority in both arms were new users and were similar in age and baseline hearing scores.

The primary outcome measure was patient-reported hearing aid benefit, measured by the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. This scale evaluates auditory acuity before and after amplification by such criteria as ease of communication, background noise, reverberation, aversiveness, and global hearing status.

Secondary measures included the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) and speech recognition in noise measured using an abbreviated speech-in-noise test and a digits-in-noise test. Measures were taken at baseline, week 2, and week 6 after fitting. After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting arm had an initial advantage on the self-reported APHAB: difference, Cohen d = −.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 0). It also fared better on the IOI-HA: effect size, r = 0.3 (95% CI, .0 to –.5), but not on speech recognition in noise.

One member of the self-fitting arm withdrew owing to an unrelated middle-ear infection.

“While these results are promising, it is essential to note that OTC hearing aids are not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dr. De Sousa said. “If a person has ear disease symptoms or hearing loss that is too severe, they have to consult a trained hearing health care professional.” She added that proper use of a self-fitted OTC hearing aid requires a degree of digital proficiency, as many devices are set up using a smartphone.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and by the hearX Group, which provided the Lexie Lumen devices and software support for data collection. Dr. De Sousa reported nonfinancial support from hearX as well as consulting fees from hearX outside of the submitted work. A coauthor reported grant support from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and fees from hearX during and outside of the study. Another coauthor disclosed fees, equity, and grant support from hearX during the conduct of the study.

Self-fitted over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids may be an effective option for individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss, a small randomized effectiveness trial reports. OTC devices yielded 6-week patient-perceived and clinical outcomes comparable to those with audiologist-fitted hearing aids, In fact, at week 2, the self-fitted group had a small but meaningful advantage on two of the four study outcome measures.

“After support and fine-tuning were provided to the self-fitting (remote support) and audiologist-fitted groups, no clinically meaningful differences were evident in any outcome measures at the end of the 6-week trial,” wrote researchers led by Karina C. De Sousa, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of speech-language pathology and audiology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Their findings appear in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Hearing aid uptake is low even in populations with adequate access to audiological resources, the authors noted, with hearing aid use in U.S. adults who could benefit estimated at about 20%. Currently, an estimated 22.9 million older Americans with audiometric hearing loss do not use hearing aids.

Major barriers have been access and affordability, Dr. De Sousa and associates wrote, and until recently, people with hearing loss could obtain hearing aids only after consultation with a credentialed dispenser. “The World Health Organization estimates that over 2.5 billion people will experience some degree of hearing loss by 2050,” Dr. De Sousa said in an interview. “This new category of self-fitting hearing aids opens up newer care pathways for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.”

The study

From April to August 2022 the trial recruited 68 participants (51.6% men) with mild-to-moderate self-reported hearing loss, a mean age of 63.6 years, and no ear disease within the past 90 days. They were randomized to a self-fitted commercially available device (Lexi Lumen), with instructional material on set-up and remote support, or to the same unit fitted by an audiologist. The majority in both arms were new users and were similar in age and baseline hearing scores.

The primary outcome measure was patient-reported hearing aid benefit, measured by the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. This scale evaluates auditory acuity before and after amplification by such criteria as ease of communication, background noise, reverberation, aversiveness, and global hearing status.

Secondary measures included the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) and speech recognition in noise measured using an abbreviated speech-in-noise test and a digits-in-noise test. Measures were taken at baseline, week 2, and week 6 after fitting. After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting arm had an initial advantage on the self-reported APHAB: difference, Cohen d = −.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 0). It also fared better on the IOI-HA: effect size, r = 0.3 (95% CI, .0 to –.5), but not on speech recognition in noise.

One member of the self-fitting arm withdrew owing to an unrelated middle-ear infection.

“While these results are promising, it is essential to note that OTC hearing aids are not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dr. De Sousa said. “If a person has ear disease symptoms or hearing loss that is too severe, they have to consult a trained hearing health care professional.” She added that proper use of a self-fitted OTC hearing aid requires a degree of digital proficiency, as many devices are set up using a smartphone.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and by the hearX Group, which provided the Lexie Lumen devices and software support for data collection. Dr. De Sousa reported nonfinancial support from hearX as well as consulting fees from hearX outside of the submitted work. A coauthor reported grant support from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and fees from hearX during and outside of the study. Another coauthor disclosed fees, equity, and grant support from hearX during the conduct of the study.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD & NECK SURGERY

Urban green and blue spaces linked to less psychological distress

The findings of the study, which was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, build on a growing understanding of the relationship between types and qualities of urban environments and dementia risk.

Adithya Vegaraju, a student at Washington State University, Spokane, led the study, which looked at data from the Washington State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess prevalence of serious psychological distress among 42,980 Washington state residents aged 65 and over.

The data, collected between 2011 and 2019, used a self-reported questionnaire to determine serious psychological distress, which is defined as a level of mental distress considered debilitating enough to warrant treatment.

Mr. Vegaraju and his coauthor Solmaz Amiri, DDes, also of Washington State University, used ZIP codes, along with U.S. census data, to approximate the urban adults’ proximity to green and blue spaces.

After controlling for potential confounders of age, sex, ethnicity, education, and marital status, the investigators found that people living within half a mile of green or blue spaces had a 17% lower risk of experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with people living farther from these spaces, the investigators said in a news release.

Implications for cognitive decline and dementia?

Psychological distress in adults has been linked in population-based longitudinal studies to later cognitive decline and dementia. One study in older adults found the risk of dementia to be more than 50% higher among adults aged 50-70 with persistent depression. Blue and green spaces have also been investigated in relation to neurodegenerative disease among older adults; a 2022 study looking at data from some 62 million Medicare beneficiaries found those living in areas with more vegetation saw lower risk of hospitalizations for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“Since we lack effective prevention methods or treatments for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, we need to get creative in how we look at these issues,” Dr. Amiri commented in a press statement about her and Mr. Vegaraju’s findings. “Our hope is that this study showing better mental health among people living close to parks and water will trigger other studies about how these benefits work and whether this proximity can help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

The investigators acknowledged that their findings were limited by reliance on a self-reported measure of psychological distress.

A bidirectional connection with depression and dementia

In a comment, Anjum Hajat, PhD, an epidemiologist at University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle who has also studied the relationship between green space and dementia risk in older adults, noted some further apparent limitations of the new study, for which only an abstract was available at publication.

“It has been shown that people with depression are at higher risk for dementia, but the opposite is also true,” Dr. Hajat commented. “Those with dementia are more likely to develop depression. This bidirectionality makes this study abstract difficult to interpret since the study is based on cross-sectional data: Individuals are not followed over time to see which develops first, dementia or depression.”

Additionally, Dr. Hajat noted, the data used to determine proximity to green and blue spaces did not allow for the calculation of precise distances between subjects’ homes and these spaces.

Mr. Vegaraju and Dr. Amiri’s study had no outside support, and the investigators declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hajat declared no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the study, which was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, build on a growing understanding of the relationship between types and qualities of urban environments and dementia risk.

Adithya Vegaraju, a student at Washington State University, Spokane, led the study, which looked at data from the Washington State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess prevalence of serious psychological distress among 42,980 Washington state residents aged 65 and over.

The data, collected between 2011 and 2019, used a self-reported questionnaire to determine serious psychological distress, which is defined as a level of mental distress considered debilitating enough to warrant treatment.

Mr. Vegaraju and his coauthor Solmaz Amiri, DDes, also of Washington State University, used ZIP codes, along with U.S. census data, to approximate the urban adults’ proximity to green and blue spaces.

After controlling for potential confounders of age, sex, ethnicity, education, and marital status, the investigators found that people living within half a mile of green or blue spaces had a 17% lower risk of experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with people living farther from these spaces, the investigators said in a news release.

Implications for cognitive decline and dementia?

Psychological distress in adults has been linked in population-based longitudinal studies to later cognitive decline and dementia. One study in older adults found the risk of dementia to be more than 50% higher among adults aged 50-70 with persistent depression. Blue and green spaces have also been investigated in relation to neurodegenerative disease among older adults; a 2022 study looking at data from some 62 million Medicare beneficiaries found those living in areas with more vegetation saw lower risk of hospitalizations for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“Since we lack effective prevention methods or treatments for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, we need to get creative in how we look at these issues,” Dr. Amiri commented in a press statement about her and Mr. Vegaraju’s findings. “Our hope is that this study showing better mental health among people living close to parks and water will trigger other studies about how these benefits work and whether this proximity can help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

The investigators acknowledged that their findings were limited by reliance on a self-reported measure of psychological distress.

A bidirectional connection with depression and dementia

In a comment, Anjum Hajat, PhD, an epidemiologist at University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle who has also studied the relationship between green space and dementia risk in older adults, noted some further apparent limitations of the new study, for which only an abstract was available at publication.

“It has been shown that people with depression are at higher risk for dementia, but the opposite is also true,” Dr. Hajat commented. “Those with dementia are more likely to develop depression. This bidirectionality makes this study abstract difficult to interpret since the study is based on cross-sectional data: Individuals are not followed over time to see which develops first, dementia or depression.”

Additionally, Dr. Hajat noted, the data used to determine proximity to green and blue spaces did not allow for the calculation of precise distances between subjects’ homes and these spaces.

Mr. Vegaraju and Dr. Amiri’s study had no outside support, and the investigators declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hajat declared no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the study, which was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, build on a growing understanding of the relationship between types and qualities of urban environments and dementia risk.

Adithya Vegaraju, a student at Washington State University, Spokane, led the study, which looked at data from the Washington State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess prevalence of serious psychological distress among 42,980 Washington state residents aged 65 and over.

The data, collected between 2011 and 2019, used a self-reported questionnaire to determine serious psychological distress, which is defined as a level of mental distress considered debilitating enough to warrant treatment.

Mr. Vegaraju and his coauthor Solmaz Amiri, DDes, also of Washington State University, used ZIP codes, along with U.S. census data, to approximate the urban adults’ proximity to green and blue spaces.

After controlling for potential confounders of age, sex, ethnicity, education, and marital status, the investigators found that people living within half a mile of green or blue spaces had a 17% lower risk of experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with people living farther from these spaces, the investigators said in a news release.

Implications for cognitive decline and dementia?

Psychological distress in adults has been linked in population-based longitudinal studies to later cognitive decline and dementia. One study in older adults found the risk of dementia to be more than 50% higher among adults aged 50-70 with persistent depression. Blue and green spaces have also been investigated in relation to neurodegenerative disease among older adults; a 2022 study looking at data from some 62 million Medicare beneficiaries found those living in areas with more vegetation saw lower risk of hospitalizations for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“Since we lack effective prevention methods or treatments for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, we need to get creative in how we look at these issues,” Dr. Amiri commented in a press statement about her and Mr. Vegaraju’s findings. “Our hope is that this study showing better mental health among people living close to parks and water will trigger other studies about how these benefits work and whether this proximity can help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

The investigators acknowledged that their findings were limited by reliance on a self-reported measure of psychological distress.

A bidirectional connection with depression and dementia

In a comment, Anjum Hajat, PhD, an epidemiologist at University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle who has also studied the relationship between green space and dementia risk in older adults, noted some further apparent limitations of the new study, for which only an abstract was available at publication.

“It has been shown that people with depression are at higher risk for dementia, but the opposite is also true,” Dr. Hajat commented. “Those with dementia are more likely to develop depression. This bidirectionality makes this study abstract difficult to interpret since the study is based on cross-sectional data: Individuals are not followed over time to see which develops first, dementia or depression.”

Additionally, Dr. Hajat noted, the data used to determine proximity to green and blue spaces did not allow for the calculation of precise distances between subjects’ homes and these spaces.

Mr. Vegaraju and Dr. Amiri’s study had no outside support, and the investigators declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hajat declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM AAN 2023

Phototherapy a safe, effective, inexpensive new option for dementia?

It may be “one of the most promising interventions for improving core symptoms” of the disease.

A new meta-analysis shows that patients with dementia who received phototherapy experienced significant cognitive improvement, compared with those who received usual treatment. However, there were no differences between study groups in terms of improved depression, agitation, or sleep problems.

“Our meta-analysis indicates that phototherapy improved cognitive function in patients with dementia. ... This suggests that phototherapy may be one of the most promising non-pharmacological interventions for improving core symptoms of dementia,” wrote the investigators, led by Xinlian Lu, Peking University, Beijing.

The study was published online in Brain and Behavior.

A new treatment option?

“As drug treatment for dementia has limitations such as medical contraindications, limited efficacy, and adverse effects, nonpharmacological therapy has been increasingly regarded as a critical part of comprehensive dementia care,” the investigators noted.

Phototherapy, which utilizes full-spectrum bright light (usually > 600 lux) or wavelength-specific light (for example, blue-enriched or blue-green), is a “promising nonpharmacological therapy” that is noninvasive, inexpensive, and safe.

Most studies of phototherapy have focused on sleep. Findings have shown “high heterogeneity” among the interventions and the populations in the studies, and results have been “inconsistent.” In addition, the effect of phototherapy on cognitive function and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) “still need to be clarified.”

In the systematic review and meta-analysis, the investigators examined the effects of phototherapy on cognitive function, BPSD, and sleep in older adults with dementia.

They searched several databases for randomized controlled trials that investigated phototherapy interventions for elderly patients. The primary outcome was cognitive function, which was assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Secondary outcomes included BPSD, including agitation, anxiety, irritability, depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, as assessed by the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD), the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI), the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), and measures of sleep, including total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE), and sleep disorders, as assessed by the Sleep Disorder Inventory (SDI).

To be included in the analysis, individual studies had to focus on elderly adults who had some form of dementia. In addition, a group receiving a phototherapy intervention had to be compared with a nonintervention group, and the study had to specify one of the above-defined outcomes.

The review included phototherapy interventions of all forms, frequencies, and durations, including use of bright light, LED light, and blue or blue-green light.

Regulating circadian rhythm

Twelve studies met the researchers’ criteria. They included a total of 766 patients with dementia – 426 in the intervention group and 340 in the control group. The mean ages ranged from 73.73 to 85.9 years, and there was a greater number of female than male participants.

Of the studies, seven employed routine daily light in the control group, while the others used either dim light (≤ 50 lux) or devices without light.

The researchers found “significant positive intervention effects” for global cognitive function. Improvements in postintervention MMSE scores differed significantly between the experimental groups and control groups (mean difference, 2.68; 95% confidence interval, 1.38-3.98; I2 = 0%).

No significant differences were found in the effects of intervention on depression symptoms, as evidenced in CSDD scores (MD, −0.70; 95% CI, −3.10 to 1.70; I2 = 81%).

Among patients with higher CMAI scores, which indicate more severe agitation behaviors, there was a “trend of decreasing CMAI scores” after phototherapy (MD, −3.12; 95% CI, −8.05 to 1.82; I2 = 0%). No significant difference in NPI scores was observed between the two groups.

Similarly, no significant difference was found between the two groups in TST, SE, or SDI scores.

Adverse effects were infrequent and were not severe. Two of the 426 patients in the intervention group experienced mild ocular irritation, and one experienced slight transient redness of the forehead.

Light “may compensate for the reduction in the visual sensory input of patients with dementia and stimulate specific neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus to regulate circadian rhythm,” the researchers suggested.

“As circadian rhythms are involved in optimal brain function, light supplementation may act on the synchronizing/phase-shifting effects of circadian rhythms to improve cognitive function,” they added.

They note that the light box is the “most commonly used device in phototherapy.” Light boxes provide full-spectrum bright light, usually greater than 2,500 lux. The duration is 30 minutes in the daytime, and treatment lasts 4-8 weeks.

The investigators cautioned that the light box should be placed 60 cm away from the patient or above the patient’s eye level. They said that a ceiling-mounted light is a “good choice” for providing whole-day phototherapy, since such lights do not interfere with the patient’s daily routine, reduce the demand on staff, and contribute to better adherence.

Phototherapy helmets and glasses are also available. These portable devices “allow for better control of light intensity and are ergonomic without interfering with patients’ normal activities.”

The researchers noted that “further well-designed studies are needed to explore the most effective clinical implementation conditions, including device type, duration, frequency, and time.”

Easy to use

Mariana Figueiro, PhD, professor and director of the Light and Health Research Center, department of population health medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said light is the “major stimulus for the circadian system, and a robust light-dark pattern daily (which can be given by light therapy during the day) improves sleep and behavior and reduces depression and agitation.”

Dr. Figueiro, who was not involved with the current study, noted that patients with dementia “have sleep issues, which can further affect their cognition; improvement in sleep leads to improvement in cognition,” and this may be an underlying mechanism associated with these results.

The clinical significance of the study “is that this is a nonpharmacological intervention and can be easily applied in the homes or controlled facilities, and it can be used with any other medication,” she pointed out.