User login

Diagnosing placenta accreta spectrum with prenatal ultrasound

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) describes abnormal invasion of placental tissue into or through the myometrium, comprising 3 distinct conditions: placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta. This complication is relatively new to obstetrics, first described in 1937.1

The overall incidence of PAS has been increasing over several decades, in parallel to an increasing rate of cesarean delivery (CD), with an incidence from 1982 through 2002 of 1 in 533 pregnancies, representing a 5-fold increase since the 1980s.2 PAS is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, placental abruption antenatally, and hemorrhage during delivery or postpartum.

Prenatal diagnosis of PAS and planned delivery at an experienced center are associated with significant reduction in maternal and fetal morbidity.3 In an era of advanced imaging modalities, prenatal detection of PAS regrettably remains variable and largely subjective: As many as 20% to 50% of cases of PAS escape prenatal diagnosis.3,4

In this article, we review the sonographic markers of PAS, including diagnostic accuracy, and propose a standardized approach to prenatal diagnosis. Throughout our discussion, we describe protocols for detection of PAS practiced at our Maternal-Fetal Medicine Program in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Eastern Virginia Medical School (also see “US evaluation of PAS risk: The authors’ recommended approach”).

Numerous risk factors

There are many risk factors for PAS, including prior uterine surgery or instrumentation, such as CD, uterine curettage, myomectomy, pelvic radiation, and endometrial ablation. Other risk factors include smoking, in vitro fertilization, advanced maternal age, multiparity, and a brief interval between prior CD and subsequent pregnancy.5 Of major significance is the increased risk of PAS in the presence of placenta previa with prior CD.6 Knowledge of clinical risk factors by the interpreting physician appears to be associated with improved detection of PAS on ultrasonography (US).4

Ultrasonographic markers of PAS

First-trimester markers

Sonographic markers of PAS in the first trimester include:

- a gestational sac implanted in the lower uterine segment or in a CD scar

- multiple hypoechoic spaces within the placenta (lacunae).7

Lower uterine-segment implantation has been defined by Ballas and colleagues as 1) a gestational sac implanted in the lower one-third of the uterus between 8 and 10 weeks’ gestation or 2) a gestational sac occupying primarily the lower uterine segment from 10 weeks’ gestation onward (FIGURE 1).8 Our experience is that it is difficult to accurately assess lower uterine-segment implantation beyond 13 weeks of gestation because the sac typically expands to fill the upper uterine cavity.

Continue to: Color Doppler US...

Color Doppler US can help differentiate lower uterine-segment implantation from a gestational sac of a failed pregnancy in the process of expulsion by demonstrating loss of circumferential blood flow in the failed pregnancy. Furthermore, applying pressure to the anterior surface of the uterus will result in downward movement of the gestational sac of a failed pregnancy.9

Not all gestational sacs that implant in the lower uterine segment lead to PAS: Subsequent normal pregnancies have been reported in this circumstance. In such cases, a normal thick myometrium is noted anterior to the gestational sac.7 A patient with lower uterine-segment implantation without evidence of anterior myometrial thinning remains at risk for third-trimester placenta previa.7

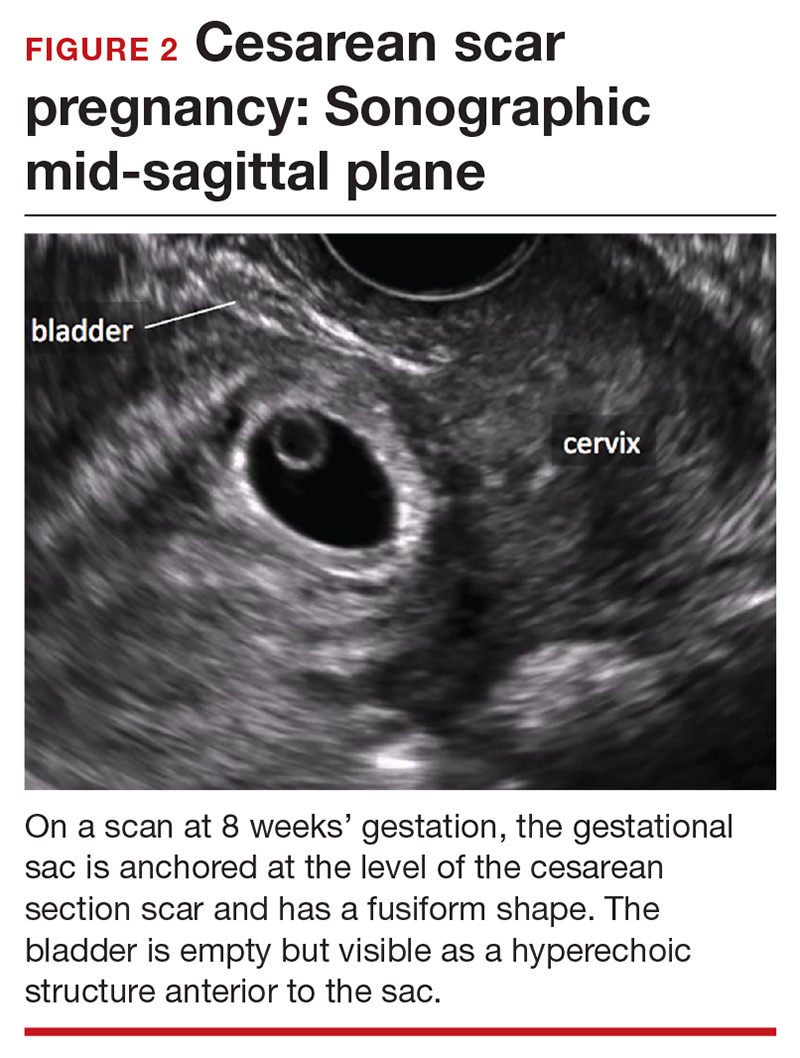

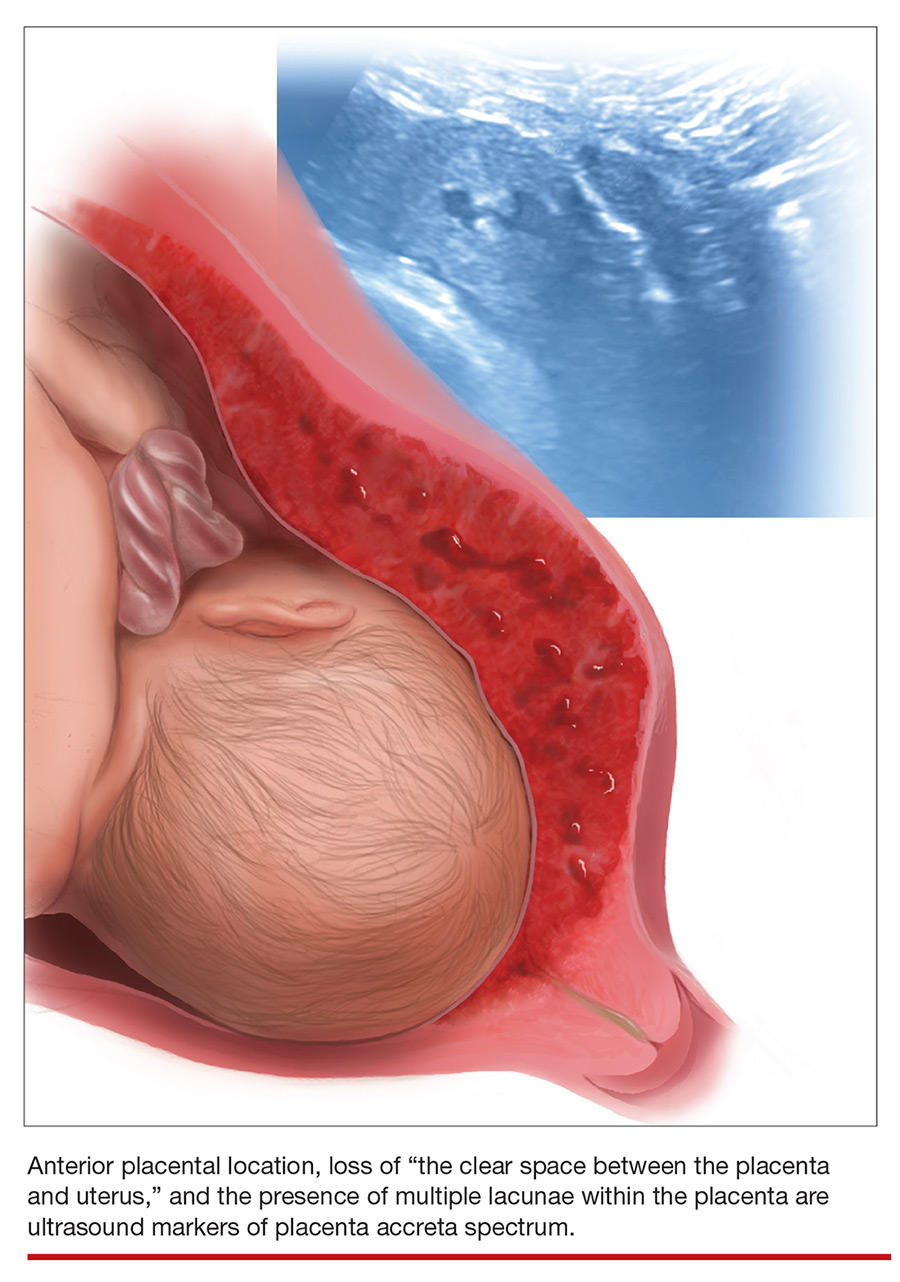

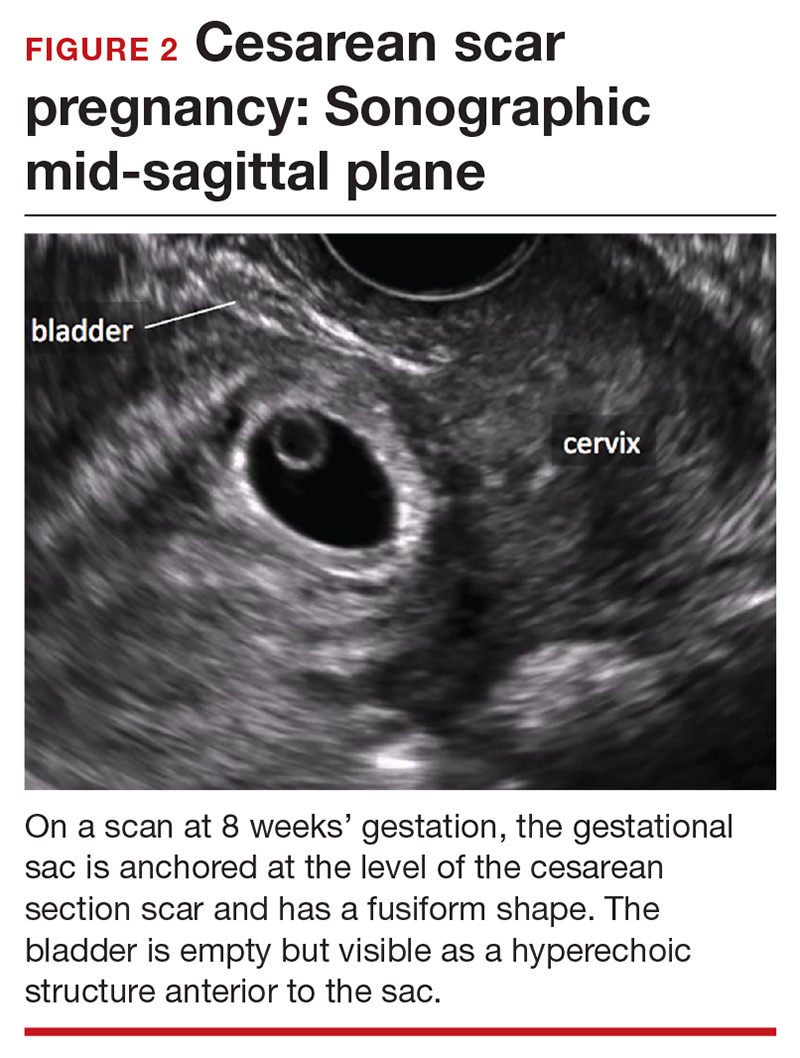

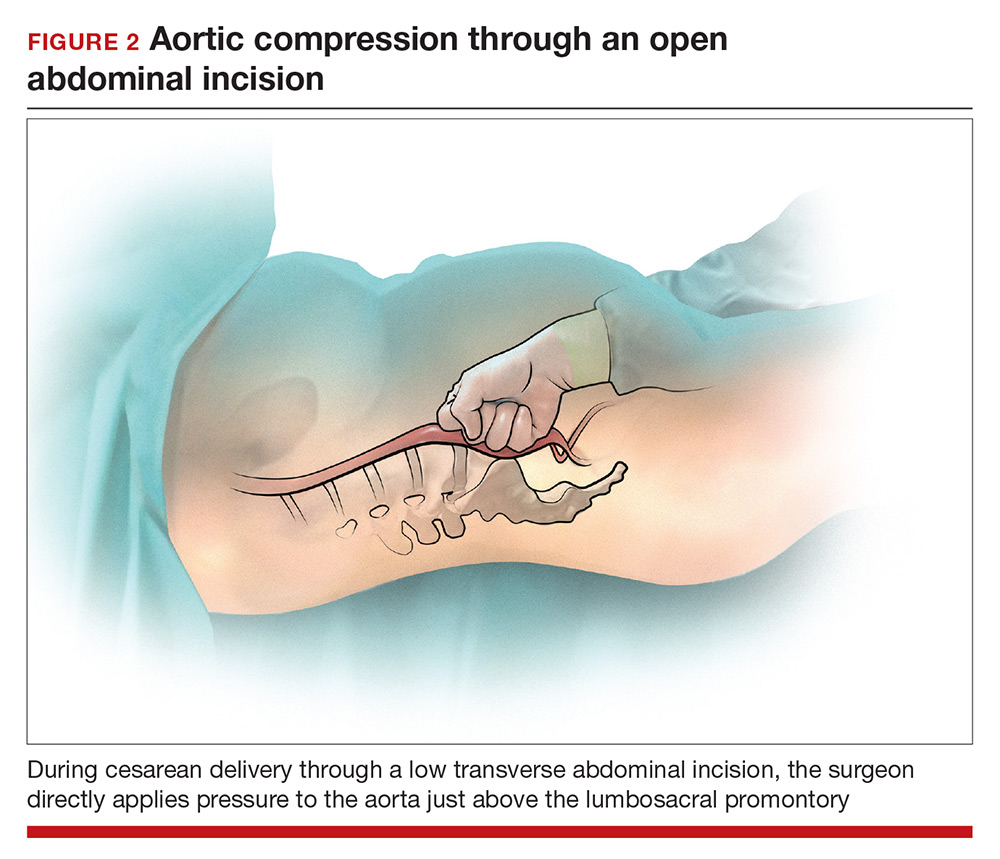

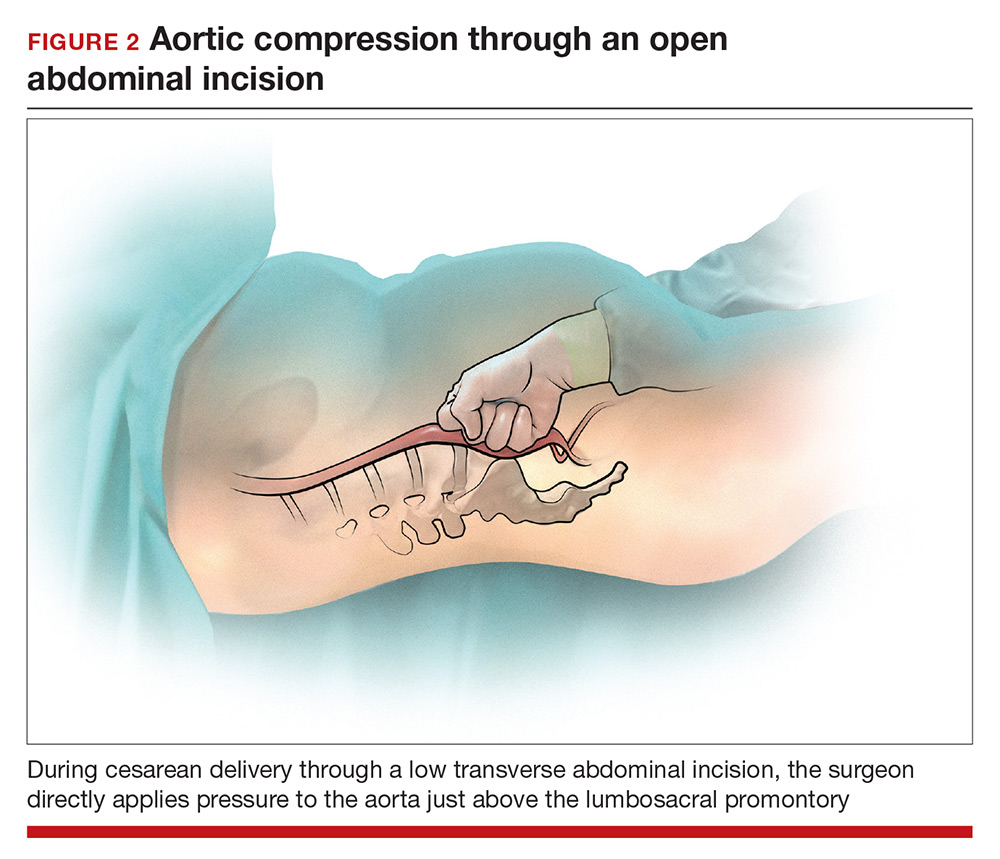

Cesarean scar pregnancy carries significant risk of PAS. In these cases, the gestational sac is typically implanted within the scar, resulting in a thin anterior myometrium and significantly increased vascularity of the placental–myometrial and bladder–uterine wall interfaces (FIGURE 2).9 Differentiating cesarean scar pregnancy from a lower uterine-segment implantation is easier to perform before the eighth week of gestation but becomes more difficult as pregnancy advances. Although it might be useful to distinguish between true cesarean scar pregnancy and lower uterine-segment implantation adjacent to or involving the scar, both carry considerable risk of PAS and excessive hemorrhage, and the approach to treating both conditions is quite similar.

Lacunae, with or without documented blood flow on color Doppler US, are the third marker of PAS in the first trimester.8 Although some retrospective series and case reports describe the finding of lacunae in the first trimester of patients with diagnosed PAS, more recent literature suggests that these spaces are seen infrequently and at a similar frequency in women with and without PAS at delivery.7

Second- and third-trimester markers

Multiple diagnostic sonographic markers of PAS have been described in the second and third trimesters.

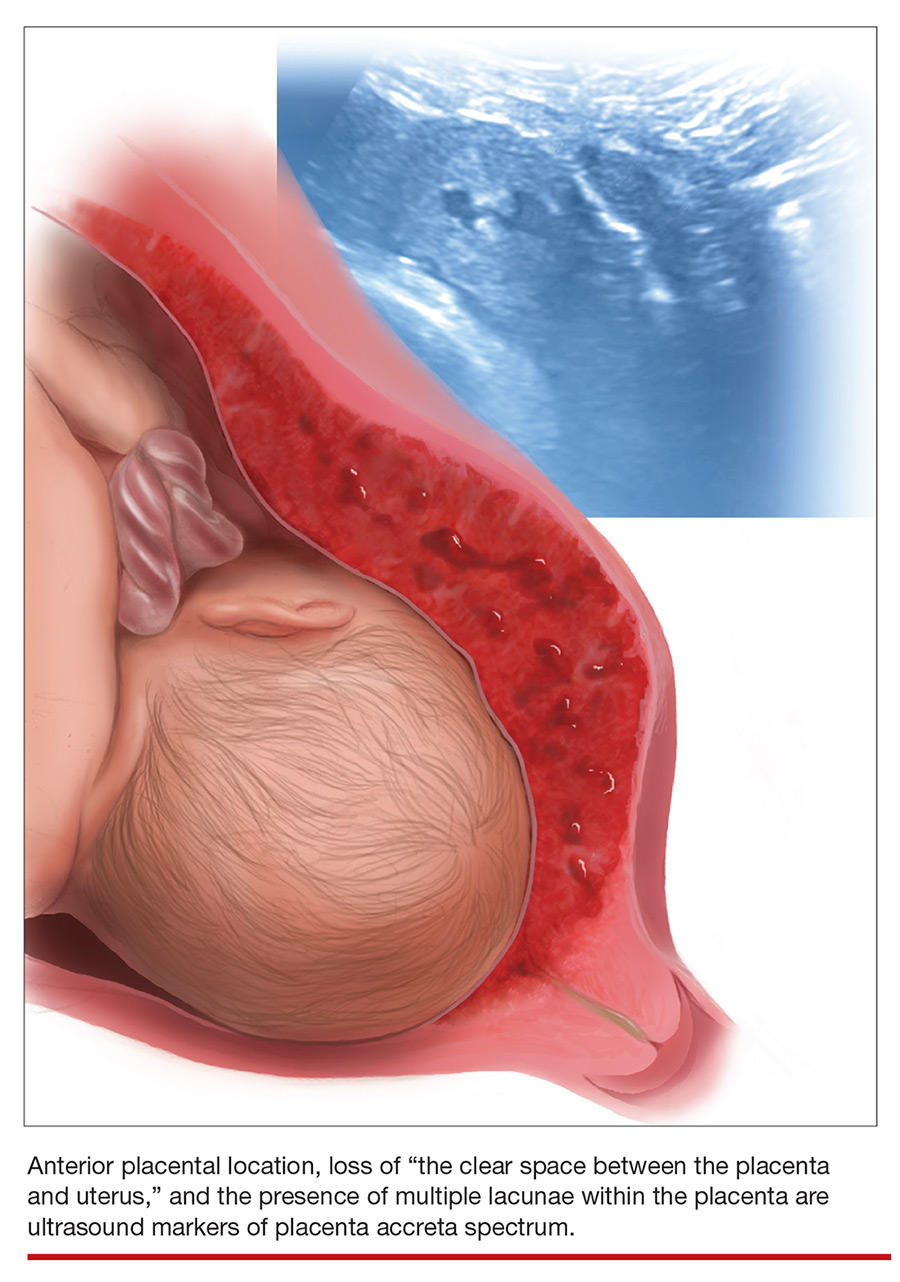

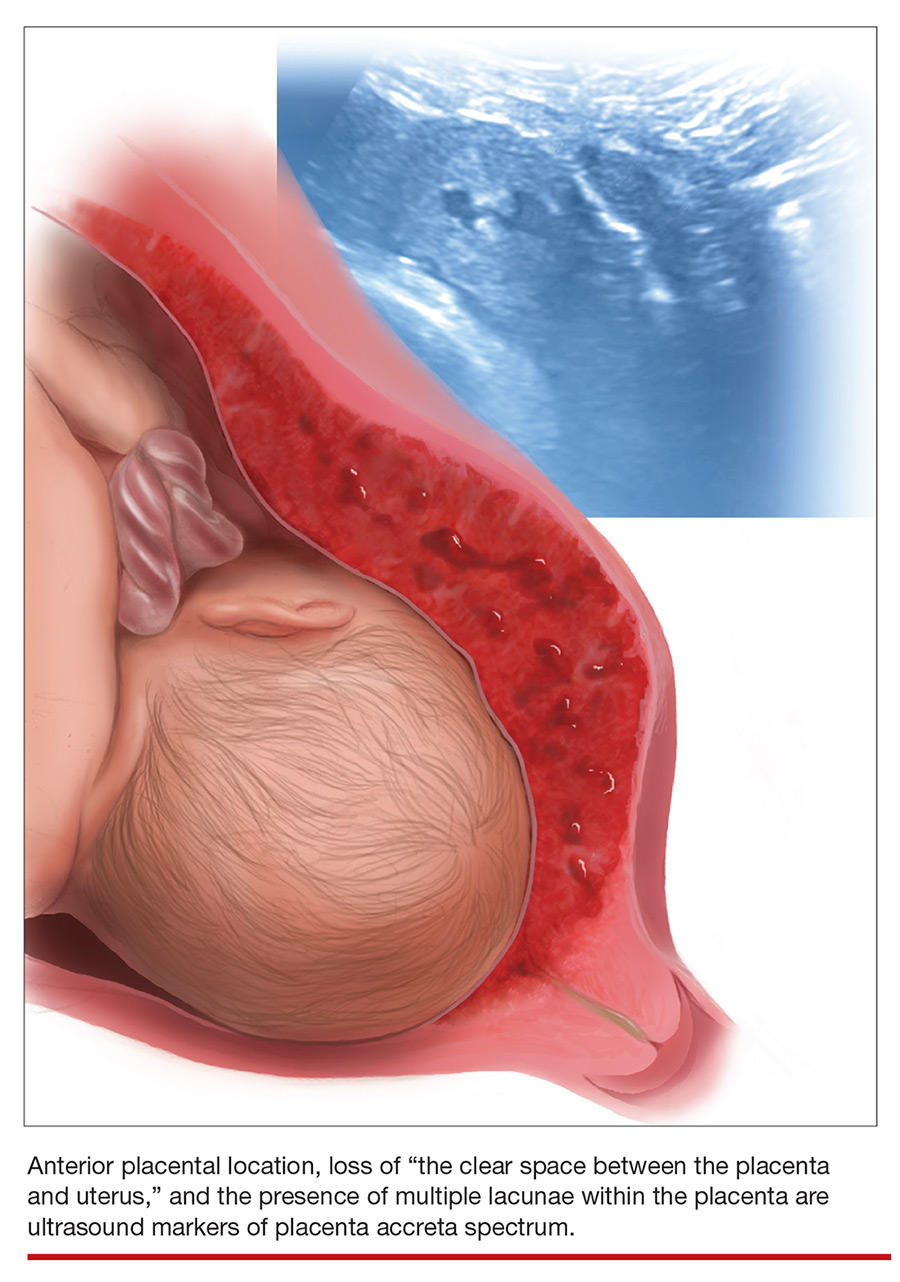

Placental location is a significant risk factor for PAS. Placenta previa in the setting of prior CD carries the highest risk of PAS—as high as 61% in women with both placenta previa and a history of 3 CDs.10 An anterior placenta appears to be a stronger risk factor for PAS than a posterior placenta in women with prior CD; the location of the placenta should therefore be evaluated in all women in the second trimester.

Continue to: Lacunae

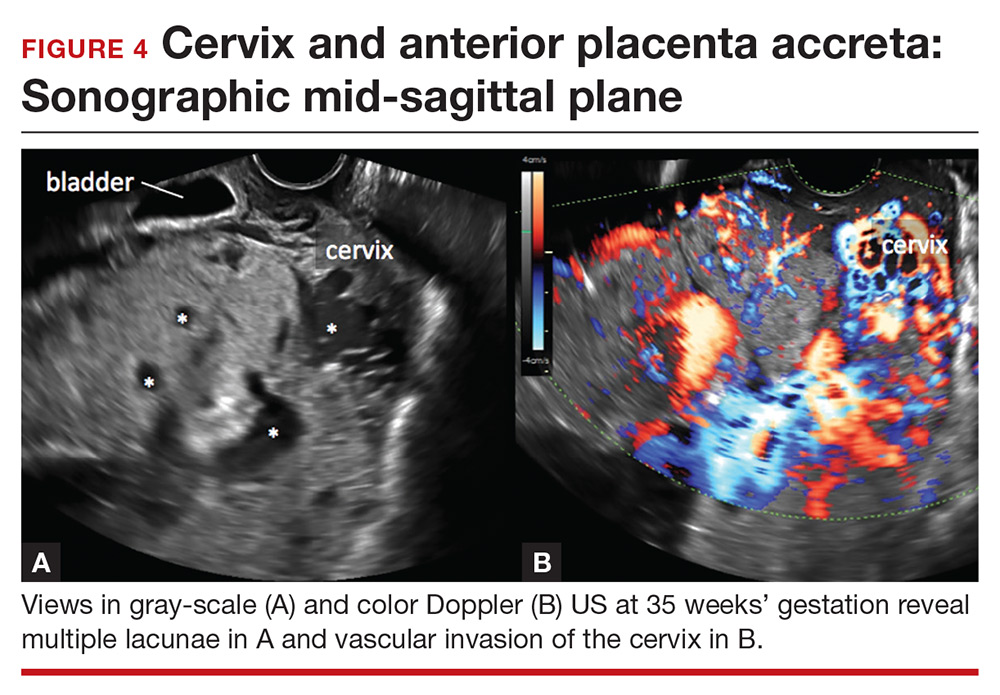

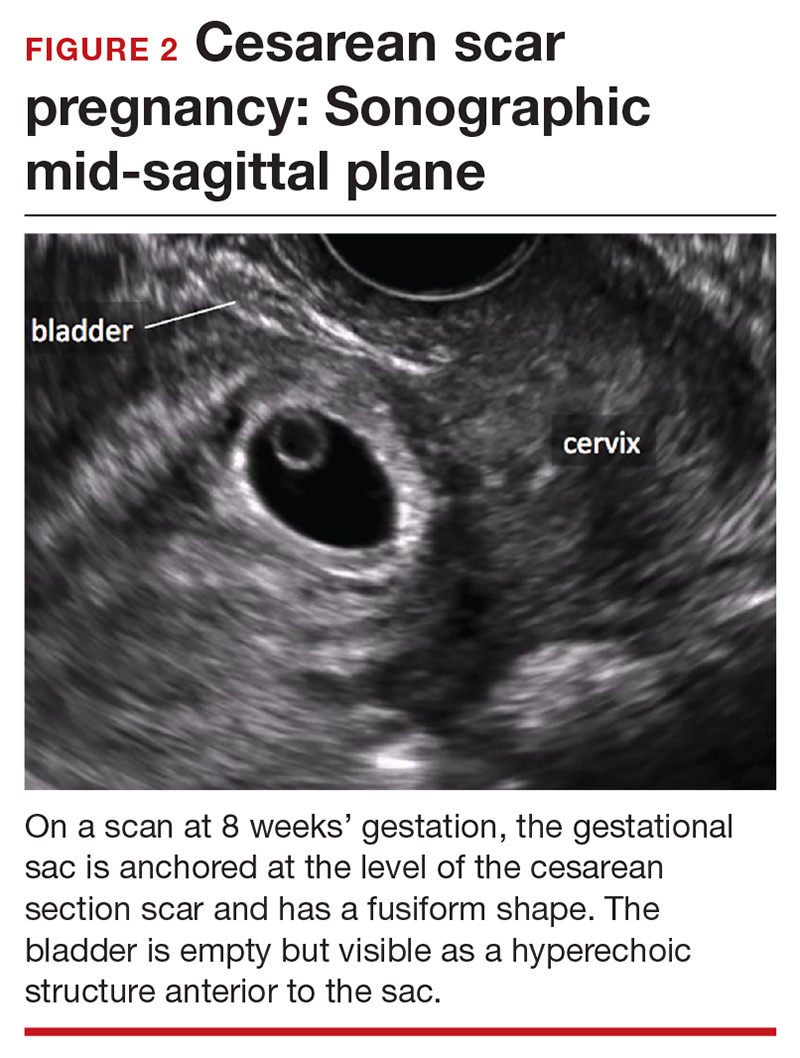

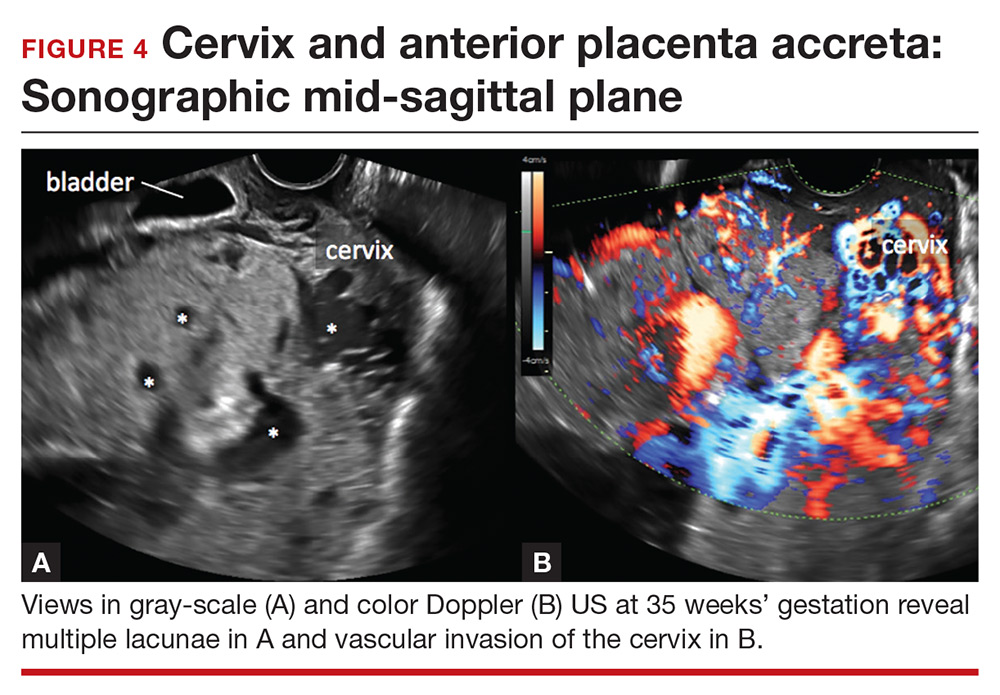

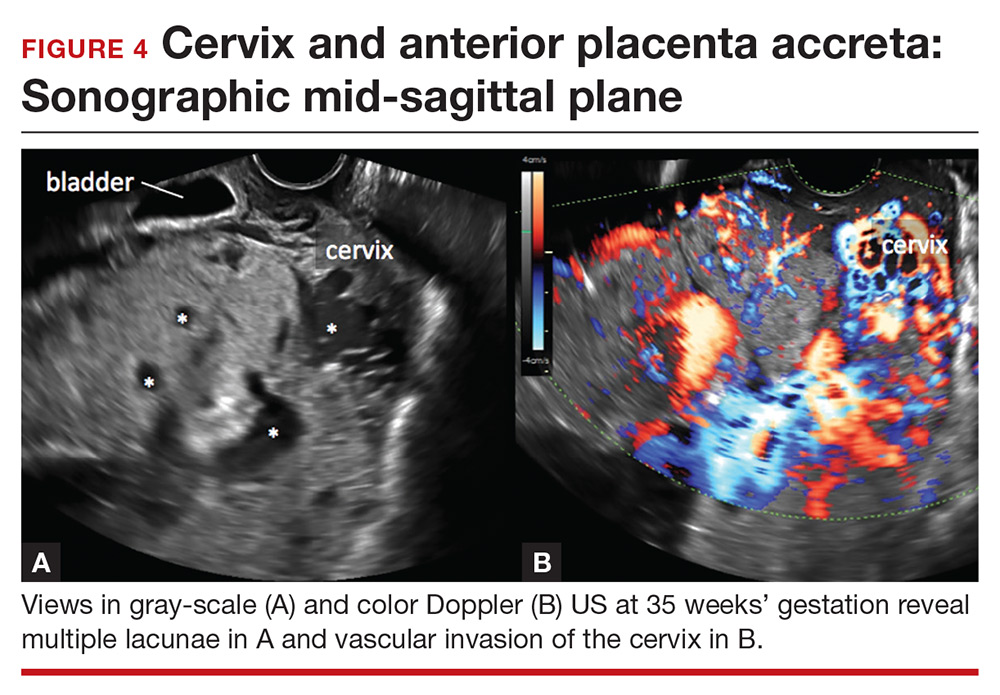

Lacunae. The finding of multiple hypoechoic vascular spaces within the placental parenchyma has been associated with PAS (FIGURES 3 and 4). The pathogenesis of this finding is probably related to alterations in placental tissue resulting from long-term exposure to pulsatile blood flow.11

Finberg and colleagues introduced a grading system for placental lacunae in 1992 that is still used:

- Grade 0: no lacunae seen

- Grade 1: 1 to 3 lacunae seen

- Grade 2: 4 to 6 lacunae seen

- Grade 3: multiple lacunae seen throughout the placenta.12

The sensitivity and specificity of lacunae as an independent marker for PAS have been reported to be 77% and 95%, respectively.13 Despite these findings, several studies report a range of sensitivity (73% to 100%) and negative predictive value (88% to 100%).14 Even in Finberg’s original work, 27% of cases of confirmed PAS had Grade 0 or Grade 1 placental lacunae and 11% of cases of placenta previa, without PAS, demonstrated Grade 2 lacunae.12 There is agreement, however, that, the more lacunae, the higher the risk of PAS.

Continue to: Other US markers for PAS

Other US markers of PAS

Retroplacental–myometrial interface

Loss of the normal hypoechoic (clear) retroplacental zone, also referred to as loss of the clear space between placenta and uterus, is another marker of PAS (FIGURE 5). This finding corresponds to pathologic loss of the decidua basalis as trophoblastic tissue invades directly through the myometrium.15 This sonographic finding has been reported to have a detection rate of approximately 93%, with sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 57%, for PAS; the false-positive rate, however, has been in the range of 21% or higher. This marker should not be used alone because it is angle-dependent and can be found (as an absent clear zone) in normal anterior placentas.16

The strength of this US marker is in its negative predictive value, which ranges from 96% to 100%. The presence of a hypoechoic retroplacental clear space that extends the length of the placenta makes PAS unlikely.17 Of note, the clear zone may appear falsely absent as a result of increased pressure from the US probe.

Retroplacental myometrial thickness

Retroplacental myometrial thickness is difficult to assess because the lower uterine-segment myometrium thins in normal pregnancy as term approaches. This measurement also can be influenced by direct pressure of the US probe and fullness of the maternal bladder.18 In patients who have had a CD but who do not have PAS, the median myometrial thickness of the lower uterine segment in the third trimester is 2.4 mm.19

Thinning of the myometrium in the upper uterine segment always should be of concern. Studies of this marker have reported sensitivity of US ranging from 22% to 100% and specificity from 72% to 100%.9,20 Given such variability, it is important to standardize the gestational age and sonographic approach for this marker.

Continue to: Uterovesical interface

Uterovesical interface

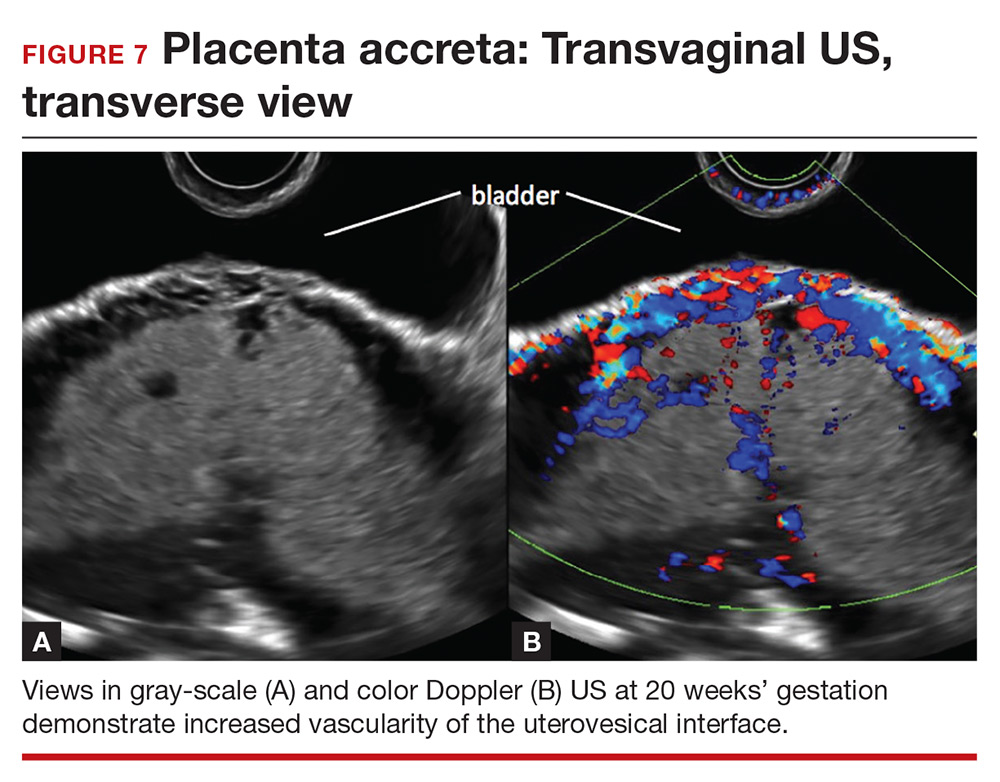

Studies also have reported that abnormalities of the uterovesical interface are predictive of PAS. The uterovesical interface is best evaluated in a sagittal plane containing the lower uterine segment and a partially full bladder in gray-scale and color Doppler US.15 The normal uterovesical interface appears as a smooth line, without irregularities or increased vascularity on sagittal imaging.

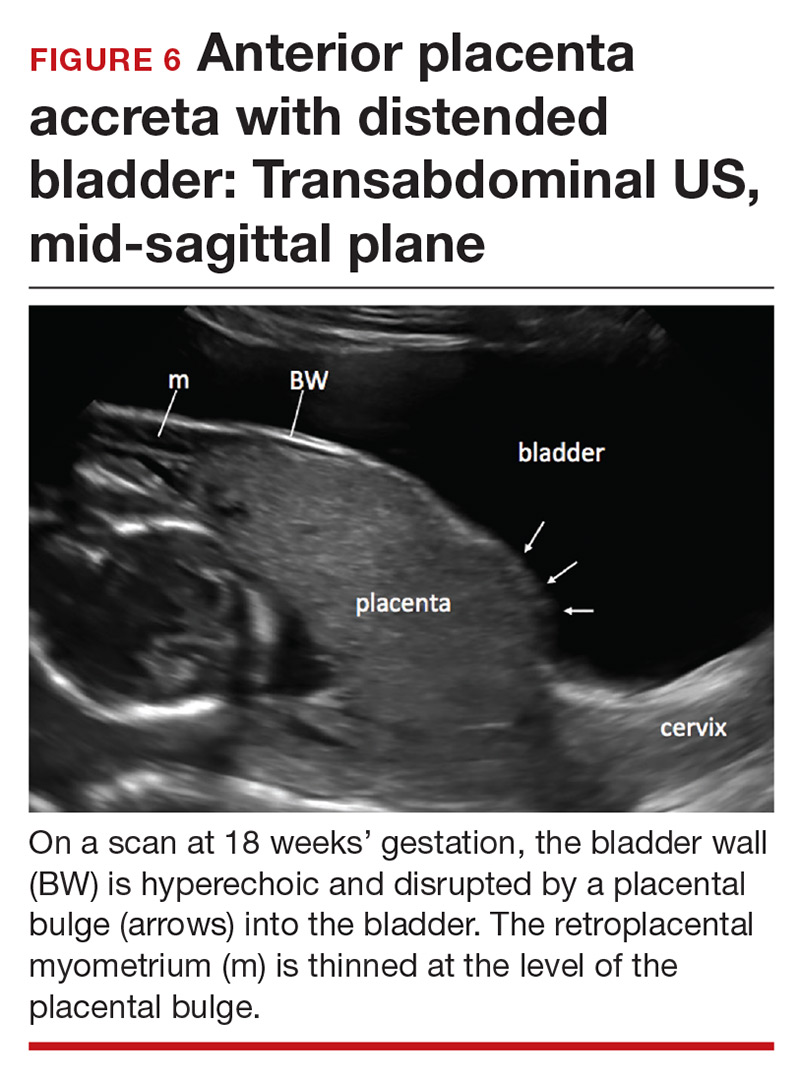

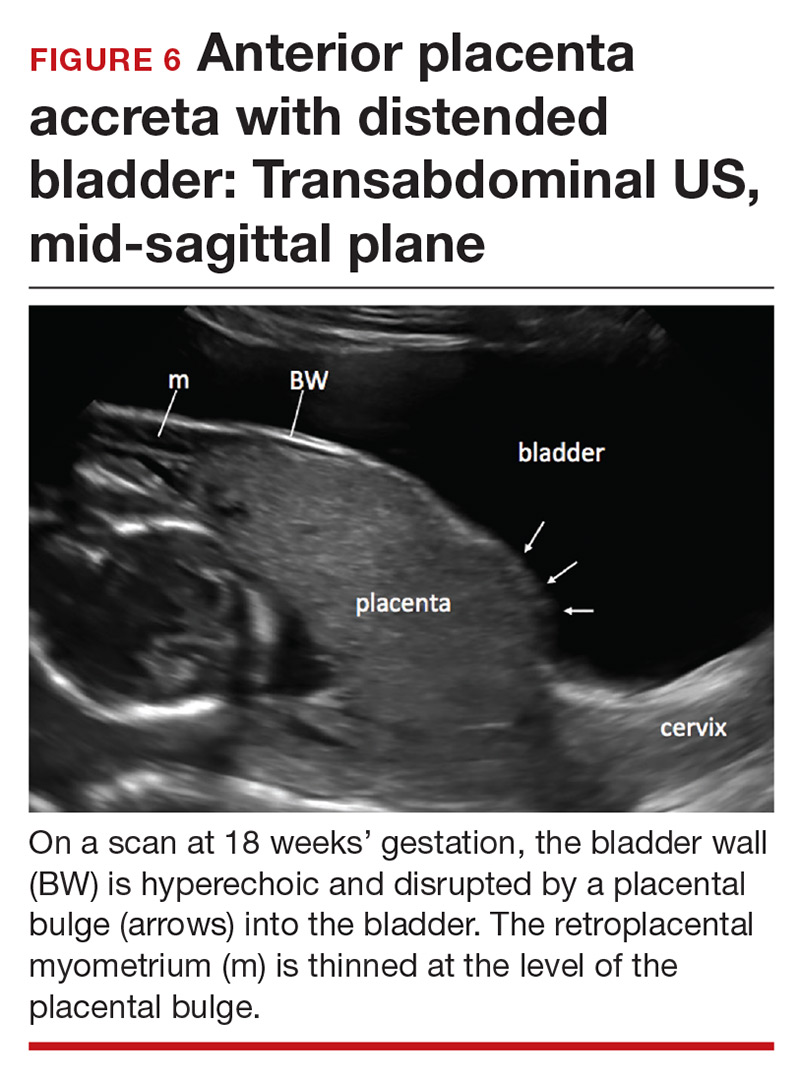

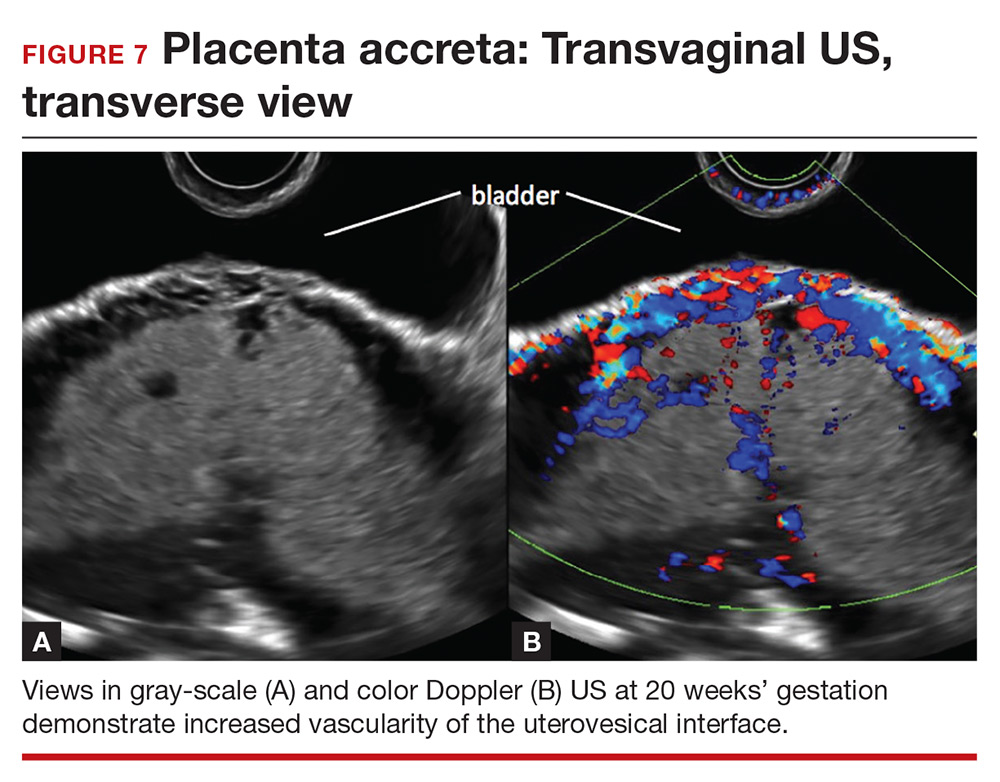

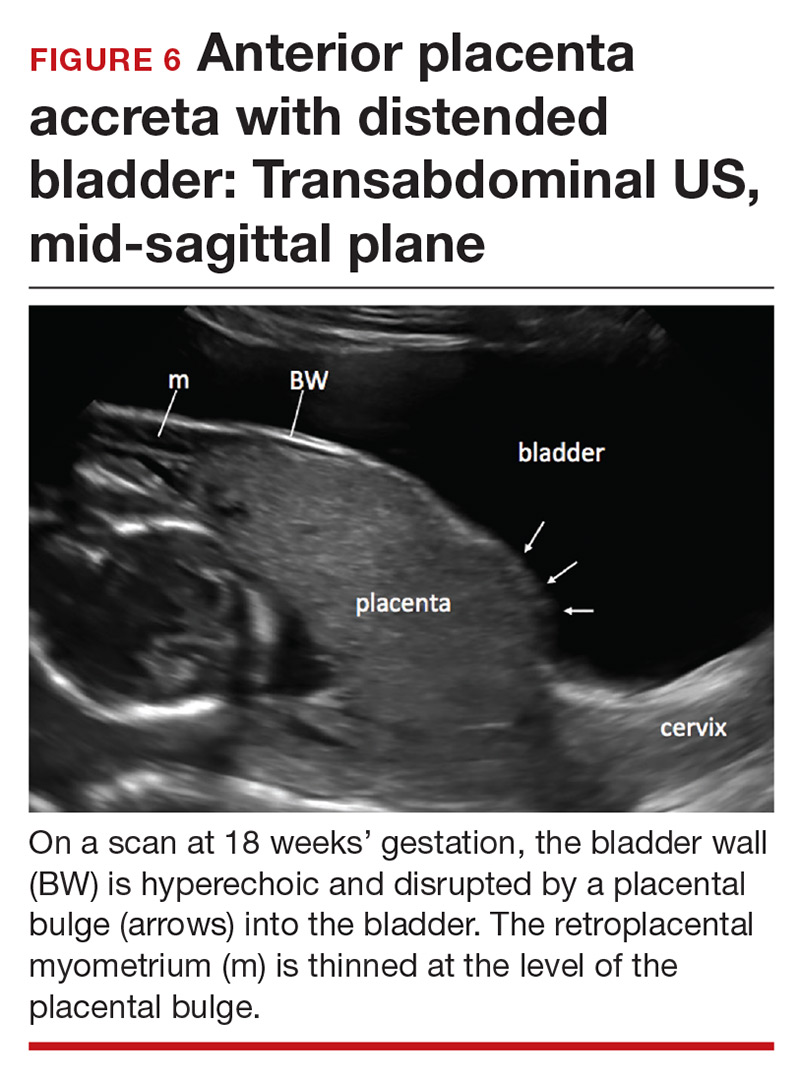

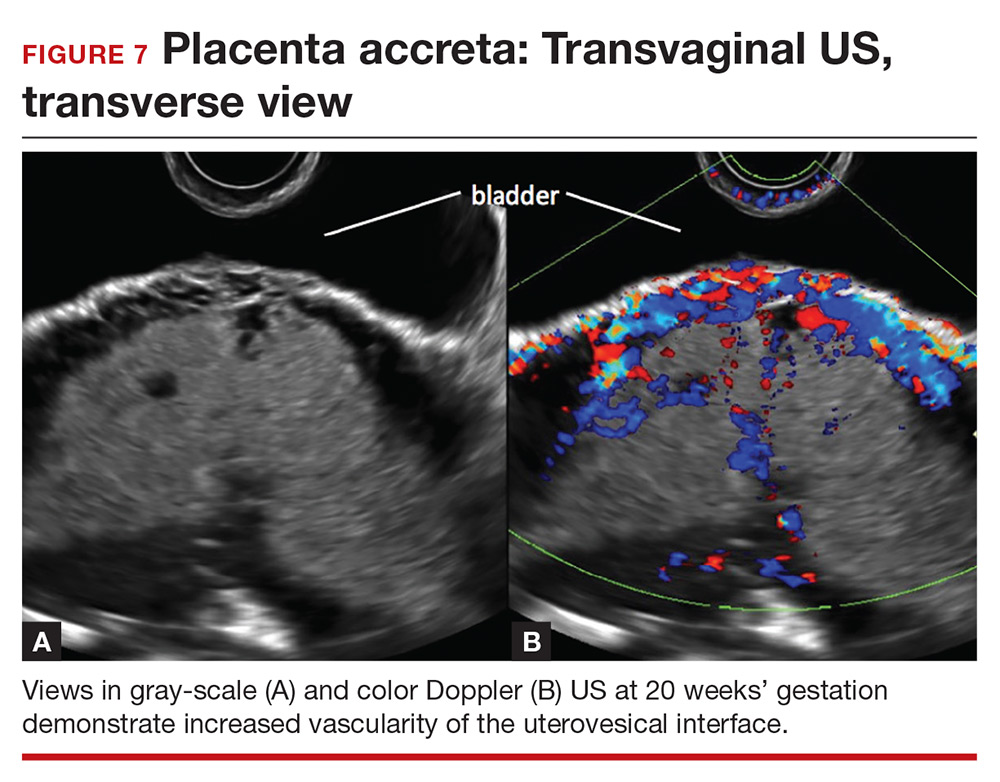

Abnormalities include focal interruption of the hyperechoic bladder wall, bulging of the bladder wall, and increased vascularity, such as varicosities (FIGURES 5, 6, and 7).15 These findings may be seen as early as the first trimester but are more commonly noted in the second and third trimesters.7 The authors of a recent meta-analysis concluded that irregularity of the uterovesical interface is the most specific marker for invasive placentation (99.75% confidence interval; range, 99.5% to 99.9%).13

Other US markers and modalities

Three-dimensional US. Studies have evaluated the role of 3-dimensional (3D) US for predicting PAS. Application of 3D US in vascular mode has shown promise because it allows for semiquantitative assessment of placental vasculature.22 Using 3D US to screen for PAS presents drawbacks, however: The technology is not well-standardized and requires significant operator expertise for volume acquisition and manipulation. Prospective studies are needed before 3D US can be applied routinely to screen for and diagnose PAS.

Color Doppler US. As an adjunct to gray-scale US, color Doppler US can be used for making a diagnosis of PAS. Color Doppler US helps differentiate a normal subplacental venous complex with nonpulsatile, low-velocity venous blood flow waveforms from markedly dilated peripheral subplacental vascular channels with pulsatile venous-type flow, which suggests PAS. These vascular channels are often located directly over the cervix. In addition, the observation of bridging vessels linking the placenta and bladder with high diastolic arterial blood flow also suggests invasion.21 In a meta-analysis, overall sensitivity of color Doppler US for the diagnosis of PAS was 91%, with specificity of 87%.13

The value of utilizing multiple markers

The accuracy of US diagnosis of PAS is likely improved by using more than 1 sonographic marker. Pilloni and colleagues,20 in a prospective analysis, found that 81% of cases of confirmed PAS had ≥2 markers and 51% of cases had ≥3 markers.

Several scoring systems have been proposed for making the diagnosis of PAS using combinations of sonographic markers, placental location, and clinical history.19,24,25 In 2016, Tovbin and colleagues,25 in a prospective study, evaluated a scoring system that included:

- number of previous CDs

- number of, maximum dimension of, and presence of blood flow in lacunae

- loss of uteroplacental clear zone

- placental location

- hypervascularity of the uterovesical or uteroplacental interface.

Tovbin assigned 1 or 2 points to each criterion. Each sonographic marker was found to be significantly associated with PAS when compared to a high-risk control group. A score of ≥8 was considered “at high risk” and predicted 69% of PAS cases.

Regrettably, no combination of US markers reliably predicts the depth of invasion of the placenta.26

Continue to: A standardized approach is needed

A standardized approach is needed

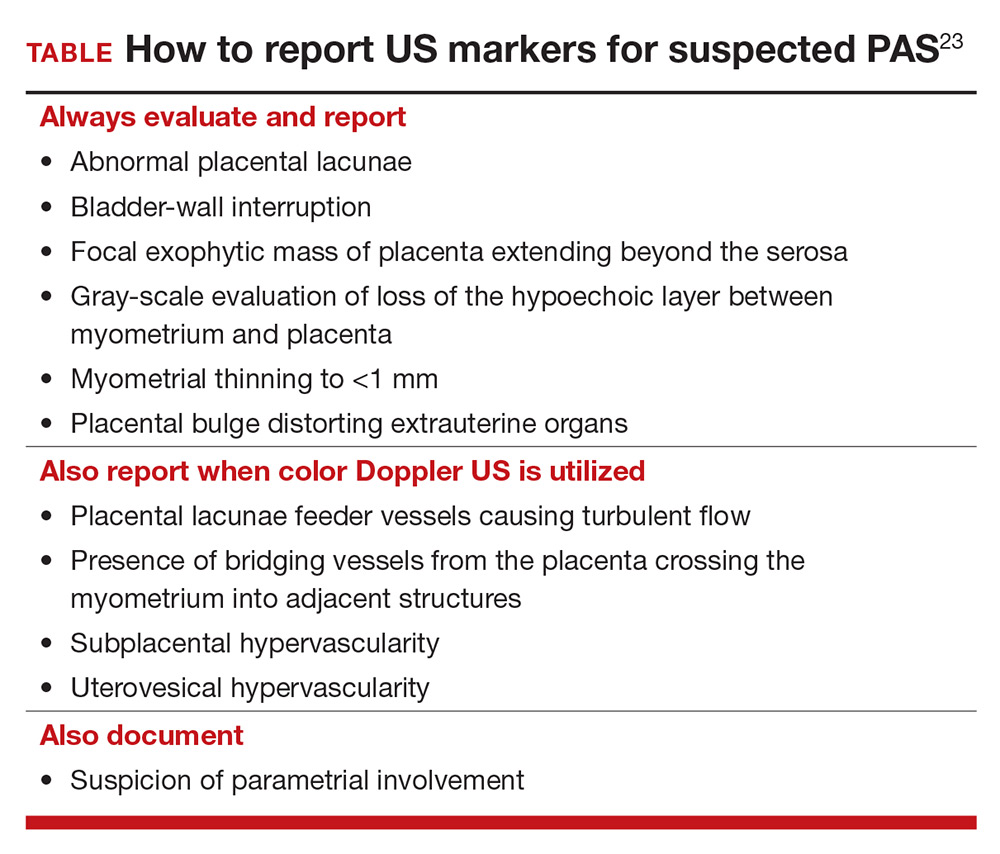

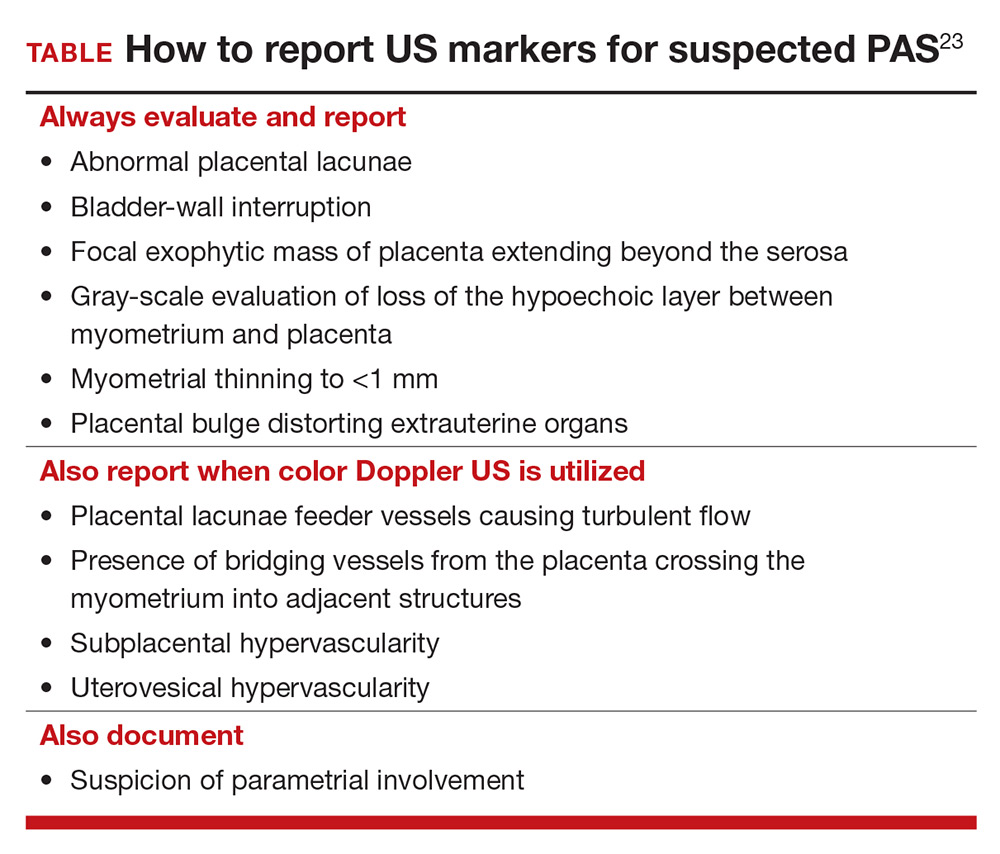

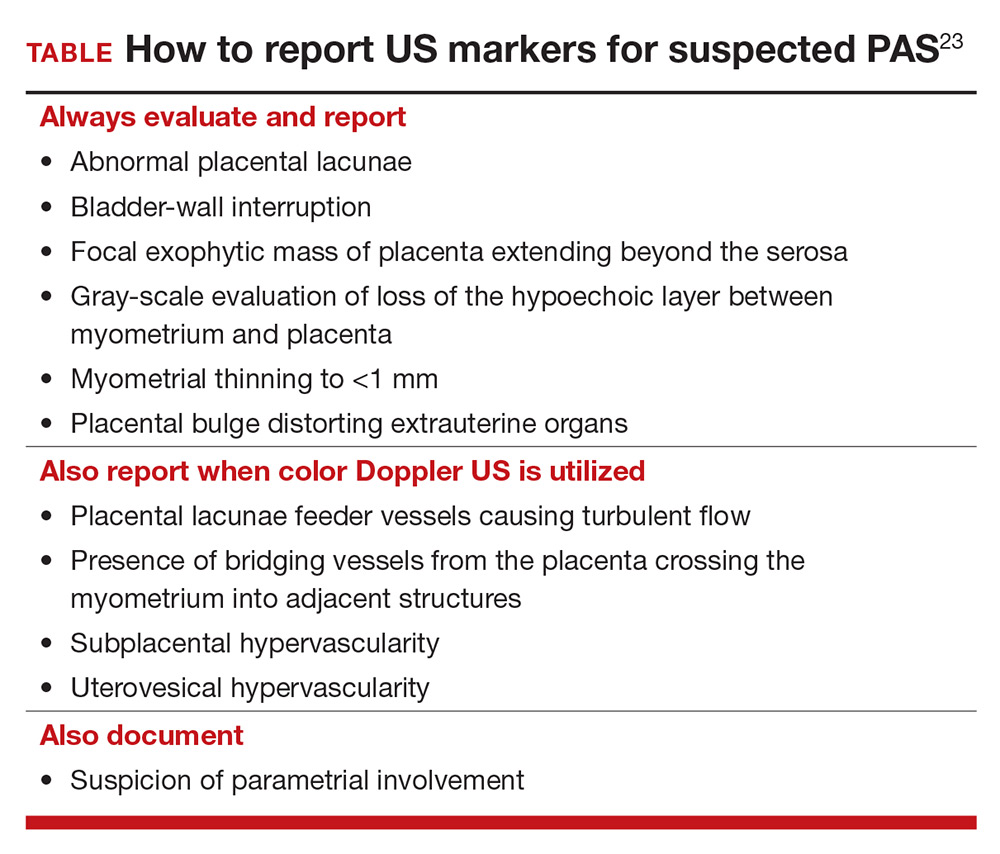

To decrease variability and improve the US diagnosis of PAS, it is important to define and standardize the diagnosis of each sonographic marker for PAS.4 In 2016, the European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (EW-AIP) proposed a set of US markers that always should be reported when performing an US examination for suspected abnormal placentation (TABLE).23 Despite this effort by the EW-AIP, ambiguity remains over sonographic definitions of several PAS markers. For example, what determines a placental lacuna on US? And what constitutes an abnormal uterovesical interface? There is a need for a more objective definition of US markers of PAS and a standardized approach to the US examination in at-risk pregnancies.

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine is coordinating a multi-society task force to address the need to define and standardize the US diagnosis of PAS.

Observations on other PAS diagnostic modalities

Magnetic resonance imaging

Adjunctive role. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used as an adjunctive diagnostic modality in cases of suspected PAS. Several markers for PAS have been described on MRI, including15:

- intraplacental T2-weighted dark bands

- abnormal intraplacental vascularity

- heterogeneous intraplacental signal intensity

- focal interruption of the myometrium by the placenta

- uterine bulging.

- Assess a priori risk for the patient before initiating the US exam

- In the presence of a placenta previa, or low-lying placenta, we strongly recommend a transvaginal, in addition to transabdominal, US to further assess for the presence of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) markers

- Until prospective studies clearly define the diagnostic accuracy of PAS sonographic markers and their performance in high-risk and low-risk pregnancies, we recommend that US findings be reported as a risk profile—that is, high, moderate, and low risk of PAS

- Be especially cautious with patients who are at substantially increased risk for PAS, such as those with placenta previa and prior multiple CDs. In this setting, a low-risk report for PAS only should be provided when none of the PAS markers are seen on transabdominal and transvaginal US examinations

- While awaiting national guidelines that 1) standardize the approach to the US examination and 2) define PAS US markers, we encourage US laboratories to develop local protocols to standardize the sonographic evaluation of the placenta and ensure uniform and complete placental assessment

Based on a recent meta-analysis, overall sensitivity of MRI for detecting PAS is 86% to 95%, with specificity of 80% to 95%. Although this is comparable to the sensitivity and specificity of US,27 studies of MRI in PAS are smaller and more prone to bias than in studies of US, because MRI typically is used only in patients at highest risk for PAS. Few studies comparing US to MRI for PAS have been performed; all are small and lack statistical power.

Complementary role. MRI can be complementary to US in cases in which the placenta is posterior or located laterally28 but, importantly, rarely changes decisions about surgical management when used in conjunction with US to assess patients for the diagnosis of PAS. (An exception might lie in the ability of MRI to assess the degree or depth of invasion of the placenta and discerning placenta percreta from placenta accreta.15)

Enhancement with contrast. Addition of gadolinium-based contrast might improve the ability of MRI to make a diagnosis of PAS, but gadolinium crosses the placenta barrier. Although fetal effects of gadolinium have not been observed, American College of Radiology guidelines recommend avoiding this contrast agent during pregnancy unless absolutely essential.29

Specific indications. MRI without contrast should be considered 1) when US is inconclusive and 2) to further evaluate a posterior placenta suspicious for invasion, to define the precise topography of extrauterine placental invasion. The additional information offered by MRI might alter surgical planning.15

Overall, based on current literature, gray-scale US appears to be an excellent tool for prenatal diagnosis of PAS in women at risk: Sensitivity has been reported in the range of 80% to 90%; specificity, 91% to 98%; positive predictive value, 65% to 93%; and negative predictive value, 98%.5,6

However, these values might overestimate the true ability of prenatal US to predict PAS. Why? Early studies that assessed the accuracy of US prediction of PAS might have been biased by inclusion of single-expert observations, high suspicion of placenta accreta, and prior knowledge of patients’ risk factors. In addition, small sample size, retrospective design, and wide variability in the definition of PAS and inclusion criteria led to inconsistency in performance and skewed sensitivity.7

In fact, when experienced providers, reviewing the same US images, were blinded to patients’ clinical history, the accuracy of US diagnosis of PAS decreased in regard to sensitivity (to 54%), specificity (88%), positive (82%) and negative (65%) predictive value, and accuracy (65%).4 Investigators also found wide inter-observer variability in the interpretation of markers of PAS.4 Furthermore, there is evidence that several PAS US markers are commonly seen in low-risk normal pregnancy.

Although studies have yielded variable findings of the precise sensitivity and positive predictive value of US in the diagnosis of PAS, there is a general agreement that US should be the primary imaging modality for this purpose, and can be used exclusively in most cases.

References

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA. The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2014;121:171-181.

- D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and metaanalysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:509-517.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135-1140.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Interobserver variability of sonography for prediction of placenta accreta. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2153-2158.

Biomarkers

Multiple serum biomarkers have been proposed to predict PAS in high-risk women. PAS might be associated with increased levels of first-trimester pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, second-trimester maternal serum alpha fetoprotein, and human chorionic gonadotropin, but studies of the utility of these biomarkers have yielded contradictory results.30,31 Biomarkers are of interest and have significant clinical applicability, but none of the ones identified to date have high sensitivity or specificity for predicting PAS prenatally. Research is ongoing to identify markers of PAS that have sufficient predictive power.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Irving FC, Hertig AT. A study of placenta accreta. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1937:64:178–200.

- Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1458–1461.

- Hall T, Wax JR, Lucas FL, et al. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of placenta accreta—impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42:449–455.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Interobserver variability of sonography for prediction of placenta accreta. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2153–2158.

- Silver RM. Abnormal placentation: placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:654–668.

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1226–1232.

- Rac MW, Moschos E, Wells CE, et al. Sonographic findings of morbidly adherent placenta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:263–269.

- Ballas J, Pretorius D, Hull AD, et al. Identifying sonographic markers for placenta accreta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1835–1841.

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA. The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2014;121:171–181.

- Marshall NE, Fu R, Guise JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:262.e1–e8.

- Baughman WC, Corteville JE, Shah RR. Placenta accreta: spectrum of US and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2008;28:1905–1916.

- Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:333–343.

- D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:509–517.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135–1140.

- D’Antonio F, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Lim PS, et al. Counseling in fetal medicine: evidence-based answers to clinical questions on morbidly adherent placenta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:290–301.

- Hudon L, Belfort MA, Broome DR. Diagnosis and management of placenta percreta: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53:509–517.

- Wong HS, Cheung YK, Zuccollo J, et al. Evaluation of sonographic diagnostic criteria for placenta accreta. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36:551–559.

- Jauniaux E, Collins S, Burton GJ. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:75–87.

- Rac MW, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Ultrasound predictors of placental invasion: the Placenta Accreta Index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:343.e1–e7.

- Pilloni E, Alemanno MG, Gaglioti P, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound in antenatal diagnosis of placental attachment disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:302–307.

- Comstock CH. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:89–96.

- Collins SL, Stevenson GN, Al-Khan A, et al. Three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing abnormally invasive placenta and quantifying the risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:645–653.

- Collins SL, Ashcroft A, Braun T, et al; European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (EW-AIP). Proposal for standardized ultrasound descriptors of abnormally invasive placenta (AIP). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:271–275.

- Gilboa Y, Spira M, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. A novel sonographic scoring system for antenatal risk assessment of obstetric complications in suspected morbidly adherent placenta. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:561–567.

- Tovbin J, Melcer Y, Shor S, et al. Prediction of morbidly adherent placenta using a scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:504–510.

- Jauniaux E, Collins SL, Jurkovic D, Burton GJ. Accreta placentation: a systematic review of prenatal ultrasound imaging and grading of villous invasiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016:215:712–721.

- Familiari A, Liberati M, Lim P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting the severity of abnormal invasive placenta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:507–520.

- Rezk MA, Shawky M. Grey-scale and colour Doppler ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for the prenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:218–223.

- Expert Panel on MR Safety; Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37:501–530.

- Pekar-Zlotin M, Melcer Y, Maymon R, Jauniaux E. Secondtrimester levels of fetoplacental hormones among women with placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:377–378.

- Lyell DJ, Faucett AM, Baer RJ, et al. Maternal serum markers, characteristics and morbidly adherent placenta in women with previa. J Perinatol. 2015;35:570–574.

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) describes abnormal invasion of placental tissue into or through the myometrium, comprising 3 distinct conditions: placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta. This complication is relatively new to obstetrics, first described in 1937.1

The overall incidence of PAS has been increasing over several decades, in parallel to an increasing rate of cesarean delivery (CD), with an incidence from 1982 through 2002 of 1 in 533 pregnancies, representing a 5-fold increase since the 1980s.2 PAS is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, placental abruption antenatally, and hemorrhage during delivery or postpartum.

Prenatal diagnosis of PAS and planned delivery at an experienced center are associated with significant reduction in maternal and fetal morbidity.3 In an era of advanced imaging modalities, prenatal detection of PAS regrettably remains variable and largely subjective: As many as 20% to 50% of cases of PAS escape prenatal diagnosis.3,4

In this article, we review the sonographic markers of PAS, including diagnostic accuracy, and propose a standardized approach to prenatal diagnosis. Throughout our discussion, we describe protocols for detection of PAS practiced at our Maternal-Fetal Medicine Program in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Eastern Virginia Medical School (also see “US evaluation of PAS risk: The authors’ recommended approach”).

Numerous risk factors

There are many risk factors for PAS, including prior uterine surgery or instrumentation, such as CD, uterine curettage, myomectomy, pelvic radiation, and endometrial ablation. Other risk factors include smoking, in vitro fertilization, advanced maternal age, multiparity, and a brief interval between prior CD and subsequent pregnancy.5 Of major significance is the increased risk of PAS in the presence of placenta previa with prior CD.6 Knowledge of clinical risk factors by the interpreting physician appears to be associated with improved detection of PAS on ultrasonography (US).4

Ultrasonographic markers of PAS

First-trimester markers

Sonographic markers of PAS in the first trimester include:

- a gestational sac implanted in the lower uterine segment or in a CD scar

- multiple hypoechoic spaces within the placenta (lacunae).7

Lower uterine-segment implantation has been defined by Ballas and colleagues as 1) a gestational sac implanted in the lower one-third of the uterus between 8 and 10 weeks’ gestation or 2) a gestational sac occupying primarily the lower uterine segment from 10 weeks’ gestation onward (FIGURE 1).8 Our experience is that it is difficult to accurately assess lower uterine-segment implantation beyond 13 weeks of gestation because the sac typically expands to fill the upper uterine cavity.

Continue to: Color Doppler US...

Color Doppler US can help differentiate lower uterine-segment implantation from a gestational sac of a failed pregnancy in the process of expulsion by demonstrating loss of circumferential blood flow in the failed pregnancy. Furthermore, applying pressure to the anterior surface of the uterus will result in downward movement of the gestational sac of a failed pregnancy.9

Not all gestational sacs that implant in the lower uterine segment lead to PAS: Subsequent normal pregnancies have been reported in this circumstance. In such cases, a normal thick myometrium is noted anterior to the gestational sac.7 A patient with lower uterine-segment implantation without evidence of anterior myometrial thinning remains at risk for third-trimester placenta previa.7

Cesarean scar pregnancy carries significant risk of PAS. In these cases, the gestational sac is typically implanted within the scar, resulting in a thin anterior myometrium and significantly increased vascularity of the placental–myometrial and bladder–uterine wall interfaces (FIGURE 2).9 Differentiating cesarean scar pregnancy from a lower uterine-segment implantation is easier to perform before the eighth week of gestation but becomes more difficult as pregnancy advances. Although it might be useful to distinguish between true cesarean scar pregnancy and lower uterine-segment implantation adjacent to or involving the scar, both carry considerable risk of PAS and excessive hemorrhage, and the approach to treating both conditions is quite similar.

Lacunae, with or without documented blood flow on color Doppler US, are the third marker of PAS in the first trimester.8 Although some retrospective series and case reports describe the finding of lacunae in the first trimester of patients with diagnosed PAS, more recent literature suggests that these spaces are seen infrequently and at a similar frequency in women with and without PAS at delivery.7

Second- and third-trimester markers

Multiple diagnostic sonographic markers of PAS have been described in the second and third trimesters.

Placental location is a significant risk factor for PAS. Placenta previa in the setting of prior CD carries the highest risk of PAS—as high as 61% in women with both placenta previa and a history of 3 CDs.10 An anterior placenta appears to be a stronger risk factor for PAS than a posterior placenta in women with prior CD; the location of the placenta should therefore be evaluated in all women in the second trimester.

Continue to: Lacunae

Lacunae. The finding of multiple hypoechoic vascular spaces within the placental parenchyma has been associated with PAS (FIGURES 3 and 4). The pathogenesis of this finding is probably related to alterations in placental tissue resulting from long-term exposure to pulsatile blood flow.11

Finberg and colleagues introduced a grading system for placental lacunae in 1992 that is still used:

- Grade 0: no lacunae seen

- Grade 1: 1 to 3 lacunae seen

- Grade 2: 4 to 6 lacunae seen

- Grade 3: multiple lacunae seen throughout the placenta.12

The sensitivity and specificity of lacunae as an independent marker for PAS have been reported to be 77% and 95%, respectively.13 Despite these findings, several studies report a range of sensitivity (73% to 100%) and negative predictive value (88% to 100%).14 Even in Finberg’s original work, 27% of cases of confirmed PAS had Grade 0 or Grade 1 placental lacunae and 11% of cases of placenta previa, without PAS, demonstrated Grade 2 lacunae.12 There is agreement, however, that, the more lacunae, the higher the risk of PAS.

Continue to: Other US markers for PAS

Other US markers of PAS

Retroplacental–myometrial interface

Loss of the normal hypoechoic (clear) retroplacental zone, also referred to as loss of the clear space between placenta and uterus, is another marker of PAS (FIGURE 5). This finding corresponds to pathologic loss of the decidua basalis as trophoblastic tissue invades directly through the myometrium.15 This sonographic finding has been reported to have a detection rate of approximately 93%, with sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 57%, for PAS; the false-positive rate, however, has been in the range of 21% or higher. This marker should not be used alone because it is angle-dependent and can be found (as an absent clear zone) in normal anterior placentas.16

The strength of this US marker is in its negative predictive value, which ranges from 96% to 100%. The presence of a hypoechoic retroplacental clear space that extends the length of the placenta makes PAS unlikely.17 Of note, the clear zone may appear falsely absent as a result of increased pressure from the US probe.

Retroplacental myometrial thickness

Retroplacental myometrial thickness is difficult to assess because the lower uterine-segment myometrium thins in normal pregnancy as term approaches. This measurement also can be influenced by direct pressure of the US probe and fullness of the maternal bladder.18 In patients who have had a CD but who do not have PAS, the median myometrial thickness of the lower uterine segment in the third trimester is 2.4 mm.19

Thinning of the myometrium in the upper uterine segment always should be of concern. Studies of this marker have reported sensitivity of US ranging from 22% to 100% and specificity from 72% to 100%.9,20 Given such variability, it is important to standardize the gestational age and sonographic approach for this marker.

Continue to: Uterovesical interface

Uterovesical interface

Studies also have reported that abnormalities of the uterovesical interface are predictive of PAS. The uterovesical interface is best evaluated in a sagittal plane containing the lower uterine segment and a partially full bladder in gray-scale and color Doppler US.15 The normal uterovesical interface appears as a smooth line, without irregularities or increased vascularity on sagittal imaging.

Abnormalities include focal interruption of the hyperechoic bladder wall, bulging of the bladder wall, and increased vascularity, such as varicosities (FIGURES 5, 6, and 7).15 These findings may be seen as early as the first trimester but are more commonly noted in the second and third trimesters.7 The authors of a recent meta-analysis concluded that irregularity of the uterovesical interface is the most specific marker for invasive placentation (99.75% confidence interval; range, 99.5% to 99.9%).13

Other US markers and modalities

Three-dimensional US. Studies have evaluated the role of 3-dimensional (3D) US for predicting PAS. Application of 3D US in vascular mode has shown promise because it allows for semiquantitative assessment of placental vasculature.22 Using 3D US to screen for PAS presents drawbacks, however: The technology is not well-standardized and requires significant operator expertise for volume acquisition and manipulation. Prospective studies are needed before 3D US can be applied routinely to screen for and diagnose PAS.

Color Doppler US. As an adjunct to gray-scale US, color Doppler US can be used for making a diagnosis of PAS. Color Doppler US helps differentiate a normal subplacental venous complex with nonpulsatile, low-velocity venous blood flow waveforms from markedly dilated peripheral subplacental vascular channels with pulsatile venous-type flow, which suggests PAS. These vascular channels are often located directly over the cervix. In addition, the observation of bridging vessels linking the placenta and bladder with high diastolic arterial blood flow also suggests invasion.21 In a meta-analysis, overall sensitivity of color Doppler US for the diagnosis of PAS was 91%, with specificity of 87%.13

The value of utilizing multiple markers

The accuracy of US diagnosis of PAS is likely improved by using more than 1 sonographic marker. Pilloni and colleagues,20 in a prospective analysis, found that 81% of cases of confirmed PAS had ≥2 markers and 51% of cases had ≥3 markers.

Several scoring systems have been proposed for making the diagnosis of PAS using combinations of sonographic markers, placental location, and clinical history.19,24,25 In 2016, Tovbin and colleagues,25 in a prospective study, evaluated a scoring system that included:

- number of previous CDs

- number of, maximum dimension of, and presence of blood flow in lacunae

- loss of uteroplacental clear zone

- placental location

- hypervascularity of the uterovesical or uteroplacental interface.

Tovbin assigned 1 or 2 points to each criterion. Each sonographic marker was found to be significantly associated with PAS when compared to a high-risk control group. A score of ≥8 was considered “at high risk” and predicted 69% of PAS cases.

Regrettably, no combination of US markers reliably predicts the depth of invasion of the placenta.26

Continue to: A standardized approach is needed

A standardized approach is needed

To decrease variability and improve the US diagnosis of PAS, it is important to define and standardize the diagnosis of each sonographic marker for PAS.4 In 2016, the European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (EW-AIP) proposed a set of US markers that always should be reported when performing an US examination for suspected abnormal placentation (TABLE).23 Despite this effort by the EW-AIP, ambiguity remains over sonographic definitions of several PAS markers. For example, what determines a placental lacuna on US? And what constitutes an abnormal uterovesical interface? There is a need for a more objective definition of US markers of PAS and a standardized approach to the US examination in at-risk pregnancies.

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine is coordinating a multi-society task force to address the need to define and standardize the US diagnosis of PAS.

Observations on other PAS diagnostic modalities

Magnetic resonance imaging

Adjunctive role. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used as an adjunctive diagnostic modality in cases of suspected PAS. Several markers for PAS have been described on MRI, including15:

- intraplacental T2-weighted dark bands

- abnormal intraplacental vascularity

- heterogeneous intraplacental signal intensity

- focal interruption of the myometrium by the placenta

- uterine bulging.

- Assess a priori risk for the patient before initiating the US exam

- In the presence of a placenta previa, or low-lying placenta, we strongly recommend a transvaginal, in addition to transabdominal, US to further assess for the presence of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) markers

- Until prospective studies clearly define the diagnostic accuracy of PAS sonographic markers and their performance in high-risk and low-risk pregnancies, we recommend that US findings be reported as a risk profile—that is, high, moderate, and low risk of PAS

- Be especially cautious with patients who are at substantially increased risk for PAS, such as those with placenta previa and prior multiple CDs. In this setting, a low-risk report for PAS only should be provided when none of the PAS markers are seen on transabdominal and transvaginal US examinations

- While awaiting national guidelines that 1) standardize the approach to the US examination and 2) define PAS US markers, we encourage US laboratories to develop local protocols to standardize the sonographic evaluation of the placenta and ensure uniform and complete placental assessment

Based on a recent meta-analysis, overall sensitivity of MRI for detecting PAS is 86% to 95%, with specificity of 80% to 95%. Although this is comparable to the sensitivity and specificity of US,27 studies of MRI in PAS are smaller and more prone to bias than in studies of US, because MRI typically is used only in patients at highest risk for PAS. Few studies comparing US to MRI for PAS have been performed; all are small and lack statistical power.

Complementary role. MRI can be complementary to US in cases in which the placenta is posterior or located laterally28 but, importantly, rarely changes decisions about surgical management when used in conjunction with US to assess patients for the diagnosis of PAS. (An exception might lie in the ability of MRI to assess the degree or depth of invasion of the placenta and discerning placenta percreta from placenta accreta.15)

Enhancement with contrast. Addition of gadolinium-based contrast might improve the ability of MRI to make a diagnosis of PAS, but gadolinium crosses the placenta barrier. Although fetal effects of gadolinium have not been observed, American College of Radiology guidelines recommend avoiding this contrast agent during pregnancy unless absolutely essential.29

Specific indications. MRI without contrast should be considered 1) when US is inconclusive and 2) to further evaluate a posterior placenta suspicious for invasion, to define the precise topography of extrauterine placental invasion. The additional information offered by MRI might alter surgical planning.15

Overall, based on current literature, gray-scale US appears to be an excellent tool for prenatal diagnosis of PAS in women at risk: Sensitivity has been reported in the range of 80% to 90%; specificity, 91% to 98%; positive predictive value, 65% to 93%; and negative predictive value, 98%.5,6

However, these values might overestimate the true ability of prenatal US to predict PAS. Why? Early studies that assessed the accuracy of US prediction of PAS might have been biased by inclusion of single-expert observations, high suspicion of placenta accreta, and prior knowledge of patients’ risk factors. In addition, small sample size, retrospective design, and wide variability in the definition of PAS and inclusion criteria led to inconsistency in performance and skewed sensitivity.7

In fact, when experienced providers, reviewing the same US images, were blinded to patients’ clinical history, the accuracy of US diagnosis of PAS decreased in regard to sensitivity (to 54%), specificity (88%), positive (82%) and negative (65%) predictive value, and accuracy (65%).4 Investigators also found wide inter-observer variability in the interpretation of markers of PAS.4 Furthermore, there is evidence that several PAS US markers are commonly seen in low-risk normal pregnancy.

Although studies have yielded variable findings of the precise sensitivity and positive predictive value of US in the diagnosis of PAS, there is a general agreement that US should be the primary imaging modality for this purpose, and can be used exclusively in most cases.

References

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA. The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2014;121:171-181.

- D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and metaanalysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:509-517.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135-1140.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Interobserver variability of sonography for prediction of placenta accreta. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2153-2158.

Biomarkers

Multiple serum biomarkers have been proposed to predict PAS in high-risk women. PAS might be associated with increased levels of first-trimester pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, second-trimester maternal serum alpha fetoprotein, and human chorionic gonadotropin, but studies of the utility of these biomarkers have yielded contradictory results.30,31 Biomarkers are of interest and have significant clinical applicability, but none of the ones identified to date have high sensitivity or specificity for predicting PAS prenatally. Research is ongoing to identify markers of PAS that have sufficient predictive power.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) describes abnormal invasion of placental tissue into or through the myometrium, comprising 3 distinct conditions: placenta accreta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta. This complication is relatively new to obstetrics, first described in 1937.1

The overall incidence of PAS has been increasing over several decades, in parallel to an increasing rate of cesarean delivery (CD), with an incidence from 1982 through 2002 of 1 in 533 pregnancies, representing a 5-fold increase since the 1980s.2 PAS is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, placental abruption antenatally, and hemorrhage during delivery or postpartum.

Prenatal diagnosis of PAS and planned delivery at an experienced center are associated with significant reduction in maternal and fetal morbidity.3 In an era of advanced imaging modalities, prenatal detection of PAS regrettably remains variable and largely subjective: As many as 20% to 50% of cases of PAS escape prenatal diagnosis.3,4

In this article, we review the sonographic markers of PAS, including diagnostic accuracy, and propose a standardized approach to prenatal diagnosis. Throughout our discussion, we describe protocols for detection of PAS practiced at our Maternal-Fetal Medicine Program in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Eastern Virginia Medical School (also see “US evaluation of PAS risk: The authors’ recommended approach”).

Numerous risk factors

There are many risk factors for PAS, including prior uterine surgery or instrumentation, such as CD, uterine curettage, myomectomy, pelvic radiation, and endometrial ablation. Other risk factors include smoking, in vitro fertilization, advanced maternal age, multiparity, and a brief interval between prior CD and subsequent pregnancy.5 Of major significance is the increased risk of PAS in the presence of placenta previa with prior CD.6 Knowledge of clinical risk factors by the interpreting physician appears to be associated with improved detection of PAS on ultrasonography (US).4

Ultrasonographic markers of PAS

First-trimester markers

Sonographic markers of PAS in the first trimester include:

- a gestational sac implanted in the lower uterine segment or in a CD scar

- multiple hypoechoic spaces within the placenta (lacunae).7

Lower uterine-segment implantation has been defined by Ballas and colleagues as 1) a gestational sac implanted in the lower one-third of the uterus between 8 and 10 weeks’ gestation or 2) a gestational sac occupying primarily the lower uterine segment from 10 weeks’ gestation onward (FIGURE 1).8 Our experience is that it is difficult to accurately assess lower uterine-segment implantation beyond 13 weeks of gestation because the sac typically expands to fill the upper uterine cavity.

Continue to: Color Doppler US...

Color Doppler US can help differentiate lower uterine-segment implantation from a gestational sac of a failed pregnancy in the process of expulsion by demonstrating loss of circumferential blood flow in the failed pregnancy. Furthermore, applying pressure to the anterior surface of the uterus will result in downward movement of the gestational sac of a failed pregnancy.9

Not all gestational sacs that implant in the lower uterine segment lead to PAS: Subsequent normal pregnancies have been reported in this circumstance. In such cases, a normal thick myometrium is noted anterior to the gestational sac.7 A patient with lower uterine-segment implantation without evidence of anterior myometrial thinning remains at risk for third-trimester placenta previa.7

Cesarean scar pregnancy carries significant risk of PAS. In these cases, the gestational sac is typically implanted within the scar, resulting in a thin anterior myometrium and significantly increased vascularity of the placental–myometrial and bladder–uterine wall interfaces (FIGURE 2).9 Differentiating cesarean scar pregnancy from a lower uterine-segment implantation is easier to perform before the eighth week of gestation but becomes more difficult as pregnancy advances. Although it might be useful to distinguish between true cesarean scar pregnancy and lower uterine-segment implantation adjacent to or involving the scar, both carry considerable risk of PAS and excessive hemorrhage, and the approach to treating both conditions is quite similar.

Lacunae, with or without documented blood flow on color Doppler US, are the third marker of PAS in the first trimester.8 Although some retrospective series and case reports describe the finding of lacunae in the first trimester of patients with diagnosed PAS, more recent literature suggests that these spaces are seen infrequently and at a similar frequency in women with and without PAS at delivery.7

Second- and third-trimester markers

Multiple diagnostic sonographic markers of PAS have been described in the second and third trimesters.

Placental location is a significant risk factor for PAS. Placenta previa in the setting of prior CD carries the highest risk of PAS—as high as 61% in women with both placenta previa and a history of 3 CDs.10 An anterior placenta appears to be a stronger risk factor for PAS than a posterior placenta in women with prior CD; the location of the placenta should therefore be evaluated in all women in the second trimester.

Continue to: Lacunae

Lacunae. The finding of multiple hypoechoic vascular spaces within the placental parenchyma has been associated with PAS (FIGURES 3 and 4). The pathogenesis of this finding is probably related to alterations in placental tissue resulting from long-term exposure to pulsatile blood flow.11

Finberg and colleagues introduced a grading system for placental lacunae in 1992 that is still used:

- Grade 0: no lacunae seen

- Grade 1: 1 to 3 lacunae seen

- Grade 2: 4 to 6 lacunae seen

- Grade 3: multiple lacunae seen throughout the placenta.12

The sensitivity and specificity of lacunae as an independent marker for PAS have been reported to be 77% and 95%, respectively.13 Despite these findings, several studies report a range of sensitivity (73% to 100%) and negative predictive value (88% to 100%).14 Even in Finberg’s original work, 27% of cases of confirmed PAS had Grade 0 or Grade 1 placental lacunae and 11% of cases of placenta previa, without PAS, demonstrated Grade 2 lacunae.12 There is agreement, however, that, the more lacunae, the higher the risk of PAS.

Continue to: Other US markers for PAS

Other US markers of PAS

Retroplacental–myometrial interface

Loss of the normal hypoechoic (clear) retroplacental zone, also referred to as loss of the clear space between placenta and uterus, is another marker of PAS (FIGURE 5). This finding corresponds to pathologic loss of the decidua basalis as trophoblastic tissue invades directly through the myometrium.15 This sonographic finding has been reported to have a detection rate of approximately 93%, with sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 57%, for PAS; the false-positive rate, however, has been in the range of 21% or higher. This marker should not be used alone because it is angle-dependent and can be found (as an absent clear zone) in normal anterior placentas.16

The strength of this US marker is in its negative predictive value, which ranges from 96% to 100%. The presence of a hypoechoic retroplacental clear space that extends the length of the placenta makes PAS unlikely.17 Of note, the clear zone may appear falsely absent as a result of increased pressure from the US probe.

Retroplacental myometrial thickness

Retroplacental myometrial thickness is difficult to assess because the lower uterine-segment myometrium thins in normal pregnancy as term approaches. This measurement also can be influenced by direct pressure of the US probe and fullness of the maternal bladder.18 In patients who have had a CD but who do not have PAS, the median myometrial thickness of the lower uterine segment in the third trimester is 2.4 mm.19

Thinning of the myometrium in the upper uterine segment always should be of concern. Studies of this marker have reported sensitivity of US ranging from 22% to 100% and specificity from 72% to 100%.9,20 Given such variability, it is important to standardize the gestational age and sonographic approach for this marker.

Continue to: Uterovesical interface

Uterovesical interface

Studies also have reported that abnormalities of the uterovesical interface are predictive of PAS. The uterovesical interface is best evaluated in a sagittal plane containing the lower uterine segment and a partially full bladder in gray-scale and color Doppler US.15 The normal uterovesical interface appears as a smooth line, without irregularities or increased vascularity on sagittal imaging.

Abnormalities include focal interruption of the hyperechoic bladder wall, bulging of the bladder wall, and increased vascularity, such as varicosities (FIGURES 5, 6, and 7).15 These findings may be seen as early as the first trimester but are more commonly noted in the second and third trimesters.7 The authors of a recent meta-analysis concluded that irregularity of the uterovesical interface is the most specific marker for invasive placentation (99.75% confidence interval; range, 99.5% to 99.9%).13

Other US markers and modalities

Three-dimensional US. Studies have evaluated the role of 3-dimensional (3D) US for predicting PAS. Application of 3D US in vascular mode has shown promise because it allows for semiquantitative assessment of placental vasculature.22 Using 3D US to screen for PAS presents drawbacks, however: The technology is not well-standardized and requires significant operator expertise for volume acquisition and manipulation. Prospective studies are needed before 3D US can be applied routinely to screen for and diagnose PAS.

Color Doppler US. As an adjunct to gray-scale US, color Doppler US can be used for making a diagnosis of PAS. Color Doppler US helps differentiate a normal subplacental venous complex with nonpulsatile, low-velocity venous blood flow waveforms from markedly dilated peripheral subplacental vascular channels with pulsatile venous-type flow, which suggests PAS. These vascular channels are often located directly over the cervix. In addition, the observation of bridging vessels linking the placenta and bladder with high diastolic arterial blood flow also suggests invasion.21 In a meta-analysis, overall sensitivity of color Doppler US for the diagnosis of PAS was 91%, with specificity of 87%.13

The value of utilizing multiple markers

The accuracy of US diagnosis of PAS is likely improved by using more than 1 sonographic marker. Pilloni and colleagues,20 in a prospective analysis, found that 81% of cases of confirmed PAS had ≥2 markers and 51% of cases had ≥3 markers.

Several scoring systems have been proposed for making the diagnosis of PAS using combinations of sonographic markers, placental location, and clinical history.19,24,25 In 2016, Tovbin and colleagues,25 in a prospective study, evaluated a scoring system that included:

- number of previous CDs

- number of, maximum dimension of, and presence of blood flow in lacunae

- loss of uteroplacental clear zone

- placental location

- hypervascularity of the uterovesical or uteroplacental interface.

Tovbin assigned 1 or 2 points to each criterion. Each sonographic marker was found to be significantly associated with PAS when compared to a high-risk control group. A score of ≥8 was considered “at high risk” and predicted 69% of PAS cases.

Regrettably, no combination of US markers reliably predicts the depth of invasion of the placenta.26

Continue to: A standardized approach is needed

A standardized approach is needed

To decrease variability and improve the US diagnosis of PAS, it is important to define and standardize the diagnosis of each sonographic marker for PAS.4 In 2016, the European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (EW-AIP) proposed a set of US markers that always should be reported when performing an US examination for suspected abnormal placentation (TABLE).23 Despite this effort by the EW-AIP, ambiguity remains over sonographic definitions of several PAS markers. For example, what determines a placental lacuna on US? And what constitutes an abnormal uterovesical interface? There is a need for a more objective definition of US markers of PAS and a standardized approach to the US examination in at-risk pregnancies.

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine is coordinating a multi-society task force to address the need to define and standardize the US diagnosis of PAS.

Observations on other PAS diagnostic modalities

Magnetic resonance imaging

Adjunctive role. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used as an adjunctive diagnostic modality in cases of suspected PAS. Several markers for PAS have been described on MRI, including15:

- intraplacental T2-weighted dark bands

- abnormal intraplacental vascularity

- heterogeneous intraplacental signal intensity

- focal interruption of the myometrium by the placenta

- uterine bulging.

- Assess a priori risk for the patient before initiating the US exam

- In the presence of a placenta previa, or low-lying placenta, we strongly recommend a transvaginal, in addition to transabdominal, US to further assess for the presence of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) markers

- Until prospective studies clearly define the diagnostic accuracy of PAS sonographic markers and their performance in high-risk and low-risk pregnancies, we recommend that US findings be reported as a risk profile—that is, high, moderate, and low risk of PAS

- Be especially cautious with patients who are at substantially increased risk for PAS, such as those with placenta previa and prior multiple CDs. In this setting, a low-risk report for PAS only should be provided when none of the PAS markers are seen on transabdominal and transvaginal US examinations

- While awaiting national guidelines that 1) standardize the approach to the US examination and 2) define PAS US markers, we encourage US laboratories to develop local protocols to standardize the sonographic evaluation of the placenta and ensure uniform and complete placental assessment

Based on a recent meta-analysis, overall sensitivity of MRI for detecting PAS is 86% to 95%, with specificity of 80% to 95%. Although this is comparable to the sensitivity and specificity of US,27 studies of MRI in PAS are smaller and more prone to bias than in studies of US, because MRI typically is used only in patients at highest risk for PAS. Few studies comparing US to MRI for PAS have been performed; all are small and lack statistical power.

Complementary role. MRI can be complementary to US in cases in which the placenta is posterior or located laterally28 but, importantly, rarely changes decisions about surgical management when used in conjunction with US to assess patients for the diagnosis of PAS. (An exception might lie in the ability of MRI to assess the degree or depth of invasion of the placenta and discerning placenta percreta from placenta accreta.15)

Enhancement with contrast. Addition of gadolinium-based contrast might improve the ability of MRI to make a diagnosis of PAS, but gadolinium crosses the placenta barrier. Although fetal effects of gadolinium have not been observed, American College of Radiology guidelines recommend avoiding this contrast agent during pregnancy unless absolutely essential.29

Specific indications. MRI without contrast should be considered 1) when US is inconclusive and 2) to further evaluate a posterior placenta suspicious for invasion, to define the precise topography of extrauterine placental invasion. The additional information offered by MRI might alter surgical planning.15

Overall, based on current literature, gray-scale US appears to be an excellent tool for prenatal diagnosis of PAS in women at risk: Sensitivity has been reported in the range of 80% to 90%; specificity, 91% to 98%; positive predictive value, 65% to 93%; and negative predictive value, 98%.5,6

However, these values might overestimate the true ability of prenatal US to predict PAS. Why? Early studies that assessed the accuracy of US prediction of PAS might have been biased by inclusion of single-expert observations, high suspicion of placenta accreta, and prior knowledge of patients’ risk factors. In addition, small sample size, retrospective design, and wide variability in the definition of PAS and inclusion criteria led to inconsistency in performance and skewed sensitivity.7

In fact, when experienced providers, reviewing the same US images, were blinded to patients’ clinical history, the accuracy of US diagnosis of PAS decreased in regard to sensitivity (to 54%), specificity (88%), positive (82%) and negative (65%) predictive value, and accuracy (65%).4 Investigators also found wide inter-observer variability in the interpretation of markers of PAS.4 Furthermore, there is evidence that several PAS US markers are commonly seen in low-risk normal pregnancy.

Although studies have yielded variable findings of the precise sensitivity and positive predictive value of US in the diagnosis of PAS, there is a general agreement that US should be the primary imaging modality for this purpose, and can be used exclusively in most cases.

References

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA. The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2014;121:171-181.

- D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and metaanalysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:509-517.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135-1140.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Interobserver variability of sonography for prediction of placenta accreta. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2153-2158.

Biomarkers

Multiple serum biomarkers have been proposed to predict PAS in high-risk women. PAS might be associated with increased levels of first-trimester pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, second-trimester maternal serum alpha fetoprotein, and human chorionic gonadotropin, but studies of the utility of these biomarkers have yielded contradictory results.30,31 Biomarkers are of interest and have significant clinical applicability, but none of the ones identified to date have high sensitivity or specificity for predicting PAS prenatally. Research is ongoing to identify markers of PAS that have sufficient predictive power.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Irving FC, Hertig AT. A study of placenta accreta. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1937:64:178–200.

- Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1458–1461.

- Hall T, Wax JR, Lucas FL, et al. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of placenta accreta—impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42:449–455.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Interobserver variability of sonography for prediction of placenta accreta. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2153–2158.

- Silver RM. Abnormal placentation: placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:654–668.

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1226–1232.

- Rac MW, Moschos E, Wells CE, et al. Sonographic findings of morbidly adherent placenta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:263–269.

- Ballas J, Pretorius D, Hull AD, et al. Identifying sonographic markers for placenta accreta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1835–1841.

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA. The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2014;121:171–181.

- Marshall NE, Fu R, Guise JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:262.e1–e8.

- Baughman WC, Corteville JE, Shah RR. Placenta accreta: spectrum of US and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2008;28:1905–1916.

- Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:333–343.

- D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:509–517.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135–1140.

- D’Antonio F, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Lim PS, et al. Counseling in fetal medicine: evidence-based answers to clinical questions on morbidly adherent placenta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:290–301.

- Hudon L, Belfort MA, Broome DR. Diagnosis and management of placenta percreta: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53:509–517.

- Wong HS, Cheung YK, Zuccollo J, et al. Evaluation of sonographic diagnostic criteria for placenta accreta. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36:551–559.

- Jauniaux E, Collins S, Burton GJ. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:75–87.

- Rac MW, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Ultrasound predictors of placental invasion: the Placenta Accreta Index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:343.e1–e7.

- Pilloni E, Alemanno MG, Gaglioti P, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound in antenatal diagnosis of placental attachment disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:302–307.

- Comstock CH. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:89–96.

- Collins SL, Stevenson GN, Al-Khan A, et al. Three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing abnormally invasive placenta and quantifying the risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:645–653.

- Collins SL, Ashcroft A, Braun T, et al; European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (EW-AIP). Proposal for standardized ultrasound descriptors of abnormally invasive placenta (AIP). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:271–275.

- Gilboa Y, Spira M, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. A novel sonographic scoring system for antenatal risk assessment of obstetric complications in suspected morbidly adherent placenta. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:561–567.

- Tovbin J, Melcer Y, Shor S, et al. Prediction of morbidly adherent placenta using a scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:504–510.

- Jauniaux E, Collins SL, Jurkovic D, Burton GJ. Accreta placentation: a systematic review of prenatal ultrasound imaging and grading of villous invasiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016:215:712–721.

- Familiari A, Liberati M, Lim P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting the severity of abnormal invasive placenta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:507–520.

- Rezk MA, Shawky M. Grey-scale and colour Doppler ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for the prenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:218–223.

- Expert Panel on MR Safety; Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37:501–530.

- Pekar-Zlotin M, Melcer Y, Maymon R, Jauniaux E. Secondtrimester levels of fetoplacental hormones among women with placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:377–378.

- Lyell DJ, Faucett AM, Baer RJ, et al. Maternal serum markers, characteristics and morbidly adherent placenta in women with previa. J Perinatol. 2015;35:570–574.

- Irving FC, Hertig AT. A study of placenta accreta. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1937:64:178–200.

- Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1458–1461.

- Hall T, Wax JR, Lucas FL, et al. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of placenta accreta—impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42:449–455.

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Kennedy AM, et al. Interobserver variability of sonography for prediction of placenta accreta. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2153–2158.

- Silver RM. Abnormal placentation: placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:654–668.

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1226–1232.

- Rac MW, Moschos E, Wells CE, et al. Sonographic findings of morbidly adherent placenta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:263–269.

- Ballas J, Pretorius D, Hull AD, et al. Identifying sonographic markers for placenta accreta in the first trimester. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1835–1841.

- Comstock CH, Bronsteen RA. The antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. BJOG. 2014;121:171–181.

- Marshall NE, Fu R, Guise JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:262.e1–e8.

- Baughman WC, Corteville JE, Shah RR. Placenta accreta: spectrum of US and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2008;28:1905–1916.

- Finberg HJ, Williams JW. Placenta accreta: prospective sonographic diagnosis in patients with placenta previa and prior cesarean section. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:333–343.

- D’Antonio F, Iacovella C, Bhide A. Prenatal identification of invasive placentation using ultrasound: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;42:509–517.

- Comstock CH, Love JJ Jr, Bronsteen RA, et al. Sonographic detection of placenta accreta in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1135–1140.

- D’Antonio F, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Lim PS, et al. Counseling in fetal medicine: evidence-based answers to clinical questions on morbidly adherent placenta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:290–301.

- Hudon L, Belfort MA, Broome DR. Diagnosis and management of placenta percreta: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53:509–517.

- Wong HS, Cheung YK, Zuccollo J, et al. Evaluation of sonographic diagnostic criteria for placenta accreta. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36:551–559.

- Jauniaux E, Collins S, Burton GJ. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:75–87.

- Rac MW, Dashe JS, Wells CE, et al. Ultrasound predictors of placental invasion: the Placenta Accreta Index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:343.e1–e7.

- Pilloni E, Alemanno MG, Gaglioti P, et al. Accuracy of ultrasound in antenatal diagnosis of placental attachment disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:302–307.

- Comstock CH. Antenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta: a review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:89–96.

- Collins SL, Stevenson GN, Al-Khan A, et al. Three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing abnormally invasive placenta and quantifying the risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:645–653.

- Collins SL, Ashcroft A, Braun T, et al; European Working Group on Abnormally Invasive Placenta (EW-AIP). Proposal for standardized ultrasound descriptors of abnormally invasive placenta (AIP). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:271–275.

- Gilboa Y, Spira M, Mazaki-Tovi S, et al. A novel sonographic scoring system for antenatal risk assessment of obstetric complications in suspected morbidly adherent placenta. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:561–567.

- Tovbin J, Melcer Y, Shor S, et al. Prediction of morbidly adherent placenta using a scoring system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:504–510.

- Jauniaux E, Collins SL, Jurkovic D, Burton GJ. Accreta placentation: a systematic review of prenatal ultrasound imaging and grading of villous invasiveness. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016:215:712–721.

- Familiari A, Liberati M, Lim P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in detecting the severity of abnormal invasive placenta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:507–520.

- Rezk MA, Shawky M. Grey-scale and colour Doppler ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for the prenatal diagnosis of placenta accreta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:218–223.

- Expert Panel on MR Safety; Kanal E, Barkovich AJ, Bell C, et al. ACR guidance document on MR safe practices: 2013. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37:501–530.

- Pekar-Zlotin M, Melcer Y, Maymon R, Jauniaux E. Secondtrimester levels of fetoplacental hormones among women with placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140:377–378.

- Lyell DJ, Faucett AM, Baer RJ, et al. Maternal serum markers, characteristics and morbidly adherent placenta in women with previa. J Perinatol. 2015;35:570–574.

Anti-TNF agents preferred for severe psoriasis in pregnancy

CHICAGO – according to Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

“We always had this concept that psoriasis gets better during pregnancy, that you might have 20% or 30% of patients who might have a little bit of a flare or maintain, but most keep on getting better,” Dr. Gordon told attendees at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

But the majority doesn’t mean everyone. He shared the case of one pregnant woman who came to him with severe psoriasis, covering the whole of her inner thigh, to underscore that severe cases do happen in pregnancy.

“These are real situations, and when you talk about maternal health, this woman is uncomfortable, she can’t sleep, and she’s having huge stressors that are not only going to impact her and her pregnancy but also that impact her child,” Dr. Gordon said.

Dr. Gordon clarified that he is not referring to patients with limited psoriasis or those who respond to topicals or phototherapy. But because methotrexate or acitretin are “hands-off during pregnancy,” he said, the only systemic therapy available for serious cases besides biologics is cyclosporine, which has its own risks. “We know that [cyclosporine] is associated with preterm labor and preterm birth and significant low birth weight, so even in the best scenario, when we have someone with persistent severe psoriasis in pregnancy, our best agent has a lot of downsides.”

Too few data exist on anti–interleukin (IL)-17 or anti-IL-23 therapies to draw conclusions about their use, he said, and but gastroenterology and rheumatology have a fair amount of evidence on anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapies during pregnancy because it’s usually too risky to stop treating conditions such as Crohn’s with these drugs. Still, Dr. Gordon cautioned, much of the data on biologics in pregnancy are conflicting.

The question of what medications to use, and in whom, centers on balancing risks to the fetus from the medication versus risks from the condition.

“There are impacts on the fetus of having severe psoriasis, and it varies with severity of disease,” Dr. Gordon said. For example, data suggest an increased likelihood of low birth weight in children born to mothers with severe psoriasis, and that risk may extend to preterm birth as well, although “we don’t know exactly the magnitude of that effect.”

Meanwhile, the consensus from the literature throughout dermatology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology is that anti-TNF agents do not cause birth defects or affect risk of preterm birth or low birth weight.

“The bigger question is what’s the impact on the immune system of the child,” Dr. Gordon said. Data from a small Scandinavian study suggested no increased risk of allergies, infections, or similar immunologic outcomes, but evidence remains limited.

Research has shown that infants’ exposure to anti-TNF medications persists for 3-6 months after delivery, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends delaying immunization in children exposed to anti-TNF agents in pregnancy. But actual evidence on immunization outcomes shows no reduced immunogenicity in such children.

“Clearly there is persistence of drug in the child, but in fact you have normal responses to immunization,” Dr. Gordon said. “The pediatricians’ argument is not based on data of what actually happens in immunization; it’s based on the fact that the drug is there.”

So what’s the bottom line?

The National Psoriasis Foundation recommends moisturizers and topical corticosteroids as first-line therapy in pregnant women with psoriasis, followed by phototherapy for second-line treatment.

But some patients will need systemic therapy during pregnancy, although it’s “best not to introduce more medications than needed in pregnancy,” Dr. Gordon said. For women with a significant flare-up or very persistent volatile disease, NPF first recommends cyclosporine, but Dr. Gordon disagrees and would go with anti-TNF agents before cyclosporine.

Data show that certolizumab is not actively transported across the placenta therefore reducing fetal exposure, so Dr. Gordon would specifically use certolizumab first, all other things being equal.

“But if the patient has been on another anti-TNF that’s been working, I don’t really have an issue with staying with it,” he added.

Existing evidence so far shows no impact in terms of genetic abnormalities, birth weight, premature birth, or even infant immunizations from anti-TNF agents. But beyond those, “there is simply not enough information on pregnancy with other forms of biologic therapy to draw conclusions.” Dr. Gordon said.

Dr. Gordon disclosed that he has received grant support and/or honoraria from Abbvie, Amgen, Almirall, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

CHICAGO – according to Kenneth B. Gordon, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

“We always had this concept that psoriasis gets better during pregnancy, that you might have 20% or 30% of patients who might have a little bit of a flare or maintain, but most keep on getting better,” Dr. Gordon told attendees at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting.

But the majority doesn’t mean everyone. He shared the case of one pregnant woman who came to him with severe psoriasis, covering the whole of her inner thigh, to underscore that severe cases do happen in pregnancy.

“These are real situations, and when you talk about maternal health, this woman is uncomfortable, she can’t sleep, and she’s having huge stressors that are not only going to impact her and her pregnancy but also that impact her child,” Dr. Gordon said.

Dr. Gordon clarified that he is not referring to patients with limited psoriasis or those who respond to topicals or phototherapy. But because methotrexate or acitretin are “hands-off during pregnancy,” he said, the only systemic therapy available for serious cases besides biologics is cyclosporine, which has its own risks. “We know that [cyclosporine] is associated with preterm labor and preterm birth and significant low birth weight, so even in the best scenario, when we have someone with persistent severe psoriasis in pregnancy, our best agent has a lot of downsides.”