User login

Biologics during pregnancy did not affect infant vaccine response

The use of biologic therapy during pregnancy did not lower antibody titers among infants vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae B (HiB) or tetanus toxin, according to the results of a study of 179 mothers reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.041).

Additionally, there was no link between median infliximab concentration in uterine cord blood and antibody titers among infants aged 7 months and older, wrote Dawn B. Beaulieu, MD, with her associates. “In a limited cohort of exposed infants given the rotavirus vaccine, there was no association with significant adverse reactions,” they also reported.

Experts now recommend against live vaccinations for infants who may have detectable concentrations of biologics, but it remained unclear whether these infants can mount adequate responses to inactive vaccines. Therefore, the researchers analyzed data from the Pregnancy in IBD and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry collected between 2007 and 2016 and surveyed women about their infants’ vaccination history. They also quantified antibodies in serum samples from infants aged 7 months and older and analyzed measured concentrations of biologics in cord blood.

Among 179 mothers with IBD, most had inactive (77%) or mild disease activity (18%) during pregnancy, the researchers said. Eleven (6%) mothers were not on immunosuppressives while pregnant, 15 (8%) were on an immunomodulator, and the rest were on biologic monotherapy (65%) or a biologic plus an immunomodulator (21%). A total of 46 infants had available HiB titer data, of whom 38 were potentially exposed to biologics; among 49 infants with available tetanus titers, 41 were potentially exposed. In all, 71% of exposed infants had protective levels of antibodies against HiB, and 80% had protective titers to tetanus toxoid. Proportions among unexposed infants were 50% and 75%, respectively. Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ between groups even after excluding infants whose mothers received certolizumab pegol, which has negligible rates of placental transfer.

A total of 39 infants received live rotavirus vaccine despite having detectable levels of biologics in cord blood at birth. Seven developed mild vaccine reactions consisting of fever (six infants) or diarrhea (one infant). This proportion (18%) resembles that from a large study (N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33) of healthy infants who were vaccinated against rotavirus, the researchers noted. “Despite our data suggesting a lack of severe side effects with the rotavirus vaccine in these infants, in the absence of robust evidence, one should continue to avoid live vaccines in infants born to mothers on biologic therapy (excluding certolizumab) during the first year of life or until drug clearance is confirmed,” they suggested. “With the growing availability of tests, one conceivably could test serum drug concentration in infants, and, if undetectable, consider live vaccination at that time, if appropriate for the vaccine, particularly in infants most likely to benefit from such vaccines.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

The use of biologic therapy during pregnancy did not lower antibody titers among infants vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae B (HiB) or tetanus toxin, according to the results of a study of 179 mothers reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.041).

Additionally, there was no link between median infliximab concentration in uterine cord blood and antibody titers among infants aged 7 months and older, wrote Dawn B. Beaulieu, MD, with her associates. “In a limited cohort of exposed infants given the rotavirus vaccine, there was no association with significant adverse reactions,” they also reported.

Experts now recommend against live vaccinations for infants who may have detectable concentrations of biologics, but it remained unclear whether these infants can mount adequate responses to inactive vaccines. Therefore, the researchers analyzed data from the Pregnancy in IBD and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry collected between 2007 and 2016 and surveyed women about their infants’ vaccination history. They also quantified antibodies in serum samples from infants aged 7 months and older and analyzed measured concentrations of biologics in cord blood.

Among 179 mothers with IBD, most had inactive (77%) or mild disease activity (18%) during pregnancy, the researchers said. Eleven (6%) mothers were not on immunosuppressives while pregnant, 15 (8%) were on an immunomodulator, and the rest were on biologic monotherapy (65%) or a biologic plus an immunomodulator (21%). A total of 46 infants had available HiB titer data, of whom 38 were potentially exposed to biologics; among 49 infants with available tetanus titers, 41 were potentially exposed. In all, 71% of exposed infants had protective levels of antibodies against HiB, and 80% had protective titers to tetanus toxoid. Proportions among unexposed infants were 50% and 75%, respectively. Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ between groups even after excluding infants whose mothers received certolizumab pegol, which has negligible rates of placental transfer.

A total of 39 infants received live rotavirus vaccine despite having detectable levels of biologics in cord blood at birth. Seven developed mild vaccine reactions consisting of fever (six infants) or diarrhea (one infant). This proportion (18%) resembles that from a large study (N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33) of healthy infants who were vaccinated against rotavirus, the researchers noted. “Despite our data suggesting a lack of severe side effects with the rotavirus vaccine in these infants, in the absence of robust evidence, one should continue to avoid live vaccines in infants born to mothers on biologic therapy (excluding certolizumab) during the first year of life or until drug clearance is confirmed,” they suggested. “With the growing availability of tests, one conceivably could test serum drug concentration in infants, and, if undetectable, consider live vaccination at that time, if appropriate for the vaccine, particularly in infants most likely to benefit from such vaccines.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

The use of biologic therapy during pregnancy did not lower antibody titers among infants vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae B (HiB) or tetanus toxin, according to the results of a study of 179 mothers reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.041).

Additionally, there was no link between median infliximab concentration in uterine cord blood and antibody titers among infants aged 7 months and older, wrote Dawn B. Beaulieu, MD, with her associates. “In a limited cohort of exposed infants given the rotavirus vaccine, there was no association with significant adverse reactions,” they also reported.

Experts now recommend against live vaccinations for infants who may have detectable concentrations of biologics, but it remained unclear whether these infants can mount adequate responses to inactive vaccines. Therefore, the researchers analyzed data from the Pregnancy in IBD and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry collected between 2007 and 2016 and surveyed women about their infants’ vaccination history. They also quantified antibodies in serum samples from infants aged 7 months and older and analyzed measured concentrations of biologics in cord blood.

Among 179 mothers with IBD, most had inactive (77%) or mild disease activity (18%) during pregnancy, the researchers said. Eleven (6%) mothers were not on immunosuppressives while pregnant, 15 (8%) were on an immunomodulator, and the rest were on biologic monotherapy (65%) or a biologic plus an immunomodulator (21%). A total of 46 infants had available HiB titer data, of whom 38 were potentially exposed to biologics; among 49 infants with available tetanus titers, 41 were potentially exposed. In all, 71% of exposed infants had protective levels of antibodies against HiB, and 80% had protective titers to tetanus toxoid. Proportions among unexposed infants were 50% and 75%, respectively. Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ between groups even after excluding infants whose mothers received certolizumab pegol, which has negligible rates of placental transfer.

A total of 39 infants received live rotavirus vaccine despite having detectable levels of biologics in cord blood at birth. Seven developed mild vaccine reactions consisting of fever (six infants) or diarrhea (one infant). This proportion (18%) resembles that from a large study (N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33) of healthy infants who were vaccinated against rotavirus, the researchers noted. “Despite our data suggesting a lack of severe side effects with the rotavirus vaccine in these infants, in the absence of robust evidence, one should continue to avoid live vaccines in infants born to mothers on biologic therapy (excluding certolizumab) during the first year of life or until drug clearance is confirmed,” they suggested. “With the growing availability of tests, one conceivably could test serum drug concentration in infants, and, if undetectable, consider live vaccination at that time, if appropriate for the vaccine, particularly in infants most likely to benefit from such vaccines.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: In utero biologic exposure did not prevent immune response to Haemophilus influenzae B and tetanus vaccines during infancy.

Major finding: Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ among groups.

Data source: A prospective study of 179 mothers with IBD and their infants.

Disclosures: The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

Postpartum depression: Moving toward improved screening with a new app

Over the last several years, there’s been increasing interest and ultimately a growing number of mandates across dozens of states to screen women for postpartum depression (PPD). As PPD is the most common, and often devastating, complication in modern obstetrics, screening for it is a movement that I fully support.

What’s been challenging is how to roll out screening in a widespread fashion using a standardized tool that is both easy to use and to score, and that has only a modest number of false positives (i.e., it has good specificity).

The first version of the MGHPDS app combines the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) – the most commonly used screen for PPD – with screening tools that measure sleep disturbance, anxiety, and stress. And while the Edinburgh scale has been an enormous contribution to psychiatry, its implementation in obstetric settings and community settings using pen and pencil has been a challenge at times given the inclusion of some questions that are “reverse scored”; other problems when the EPDS has been scaled for use in large settings include rates of false positives as high as 25%.

Our app, which gives users an opportunity to let us review their scores after giving informed consent, ultimately will lead to the development of a shortened set of questions that zero in on the symptoms most commonly associated with PPD. That information will derive from a validation study looking at how well the questions on the MGHPDS correlate with major depression; we hope to launch version 2.0 in mid-2018. The second version of the app is likely to include some items from the Edinburgh scale and also selected symptoms of anxiety, sleep problems, and perceived stress. Thus, the goal of the second version will be realized: a more specific scale with targeted symptoms that correlate with the clinical diagnosis of depression.

Automatic scoring of the questionnaires leads to an app-generated result across a spectrum from “no evidence of depressive symptoms,” to a message noting concern and instructing the user to seek medical attention. There are also links to educational resources about PPD within the app.

The task of referring women with PPD for treatment and then getting them well is a huge undertaking, and one where we currently are falling short. I have been heartened across the last decade to see the focus land on the issue of PPD screening, but failing to couple screening with evidence-based treatment is an incomplete victory. So with the next version of the app, we want to include treatment tools and a way to track women over time, looking at whether they were treated and if they got well.

We want clinicians to be aware of our app and to share it with their patients. But even more importantly, we want to reach out directly to women because they will lead the way on this effort.

The stakes for unrecognized and untreated PPD are simply too great for women, children, and their families.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Over the last several years, there’s been increasing interest and ultimately a growing number of mandates across dozens of states to screen women for postpartum depression (PPD). As PPD is the most common, and often devastating, complication in modern obstetrics, screening for it is a movement that I fully support.

What’s been challenging is how to roll out screening in a widespread fashion using a standardized tool that is both easy to use and to score, and that has only a modest number of false positives (i.e., it has good specificity).

The first version of the MGHPDS app combines the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) – the most commonly used screen for PPD – with screening tools that measure sleep disturbance, anxiety, and stress. And while the Edinburgh scale has been an enormous contribution to psychiatry, its implementation in obstetric settings and community settings using pen and pencil has been a challenge at times given the inclusion of some questions that are “reverse scored”; other problems when the EPDS has been scaled for use in large settings include rates of false positives as high as 25%.

Our app, which gives users an opportunity to let us review their scores after giving informed consent, ultimately will lead to the development of a shortened set of questions that zero in on the symptoms most commonly associated with PPD. That information will derive from a validation study looking at how well the questions on the MGHPDS correlate with major depression; we hope to launch version 2.0 in mid-2018. The second version of the app is likely to include some items from the Edinburgh scale and also selected symptoms of anxiety, sleep problems, and perceived stress. Thus, the goal of the second version will be realized: a more specific scale with targeted symptoms that correlate with the clinical diagnosis of depression.

Automatic scoring of the questionnaires leads to an app-generated result across a spectrum from “no evidence of depressive symptoms,” to a message noting concern and instructing the user to seek medical attention. There are also links to educational resources about PPD within the app.

The task of referring women with PPD for treatment and then getting them well is a huge undertaking, and one where we currently are falling short. I have been heartened across the last decade to see the focus land on the issue of PPD screening, but failing to couple screening with evidence-based treatment is an incomplete victory. So with the next version of the app, we want to include treatment tools and a way to track women over time, looking at whether they were treated and if they got well.

We want clinicians to be aware of our app and to share it with their patients. But even more importantly, we want to reach out directly to women because they will lead the way on this effort.

The stakes for unrecognized and untreated PPD are simply too great for women, children, and their families.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Over the last several years, there’s been increasing interest and ultimately a growing number of mandates across dozens of states to screen women for postpartum depression (PPD). As PPD is the most common, and often devastating, complication in modern obstetrics, screening for it is a movement that I fully support.

What’s been challenging is how to roll out screening in a widespread fashion using a standardized tool that is both easy to use and to score, and that has only a modest number of false positives (i.e., it has good specificity).

The first version of the MGHPDS app combines the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) – the most commonly used screen for PPD – with screening tools that measure sleep disturbance, anxiety, and stress. And while the Edinburgh scale has been an enormous contribution to psychiatry, its implementation in obstetric settings and community settings using pen and pencil has been a challenge at times given the inclusion of some questions that are “reverse scored”; other problems when the EPDS has been scaled for use in large settings include rates of false positives as high as 25%.

Our app, which gives users an opportunity to let us review their scores after giving informed consent, ultimately will lead to the development of a shortened set of questions that zero in on the symptoms most commonly associated with PPD. That information will derive from a validation study looking at how well the questions on the MGHPDS correlate with major depression; we hope to launch version 2.0 in mid-2018. The second version of the app is likely to include some items from the Edinburgh scale and also selected symptoms of anxiety, sleep problems, and perceived stress. Thus, the goal of the second version will be realized: a more specific scale with targeted symptoms that correlate with the clinical diagnosis of depression.

Automatic scoring of the questionnaires leads to an app-generated result across a spectrum from “no evidence of depressive symptoms,” to a message noting concern and instructing the user to seek medical attention. There are also links to educational resources about PPD within the app.

The task of referring women with PPD for treatment and then getting them well is a huge undertaking, and one where we currently are falling short. I have been heartened across the last decade to see the focus land on the issue of PPD screening, but failing to couple screening with evidence-based treatment is an incomplete victory. So with the next version of the app, we want to include treatment tools and a way to track women over time, looking at whether they were treated and if they got well.

We want clinicians to be aware of our app and to share it with their patients. But even more importantly, we want to reach out directly to women because they will lead the way on this effort.

The stakes for unrecognized and untreated PPD are simply too great for women, children, and their families.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

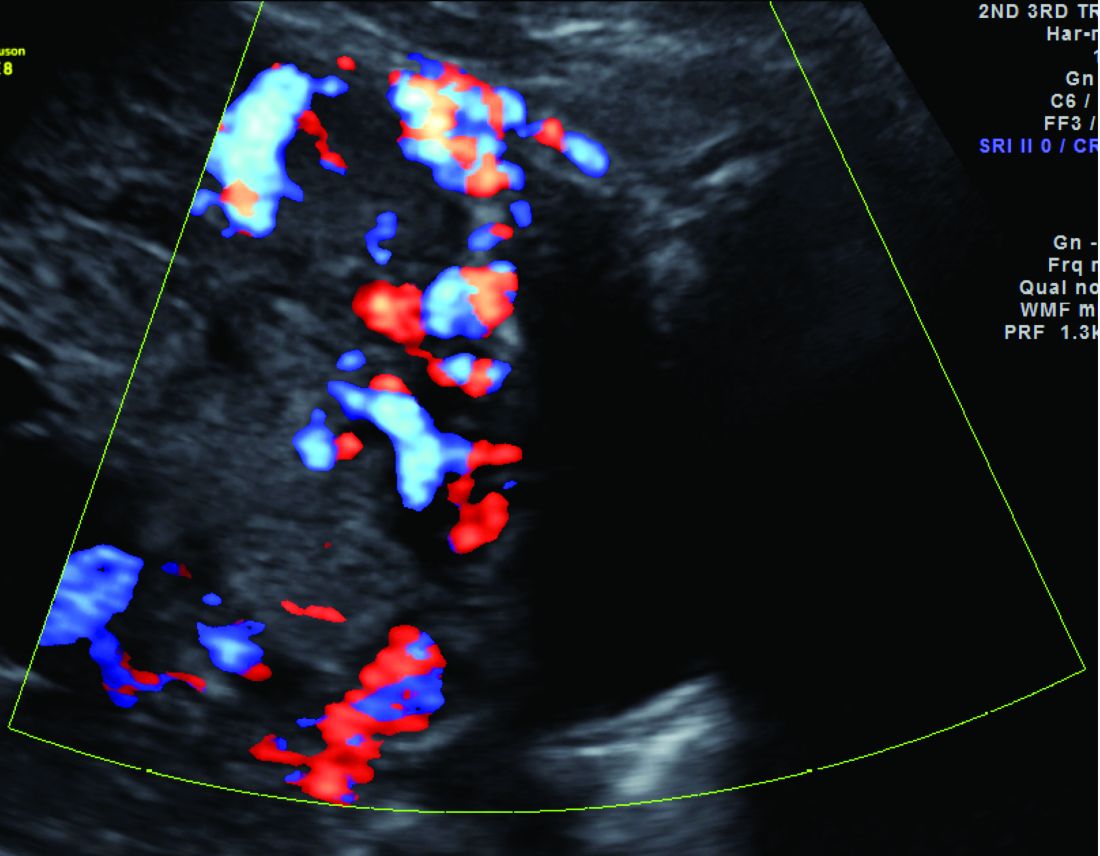

To predict macrosomia, focus on the abdomen

WASHINGTON – , John C. Hobbins, MD, said at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“Everything that the estimated fetal weight [EFW] can do, the abdominal circumference can do better,” especially in diabetic mothers, said Dr. Hobbins, who is widely regarded as one of the early pioneers in the development and use of obstetric ultrasound as a diagnostic tool.

Because it reflects liver size and incorporates subcutaneous fat, the abdominal circumference (AC) “concentrates on where the action is,” he said. It also “roughly correlates” with the size of the fetal shoulders and is not affected by genetic factors.

Moreover, “it focuses on one task rather than putting into play four variables, each with its own standard error of the method,” said Dr. Hobbins, referring to the four fetal biometric parameters incorporated into the Hadlock formula for EFW that is provided “upon fire-up of virtually every ultrasound machine.”

These four parameters (biparietal diameter, head circumference, femur length, and AC) each contribute to fetal weight but the AC has been shown to correlate better with weight at birth than the other variables, and it is the only measure that reflects how corpulent the fetus is, he noted.

The “general rule of thumb is that the EFW [as calculated by ultrasound machine–based equations] has a standard error of the method of plus or minus 10%. … which means that an EFW of 4,000 g is associated with a splay of plus or minus 1.2 pounds,” said Dr. Hobbins, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“But the problem for us is not the failure of the ultrasound – it’s the way we use it,” he said.

An assortment of customized formulas have been developed for macrosomia, including one designed for use in diabetes that incorporates AC, head circumference, femur length, and 3D volumes of the thigh and abdomen. “If one used this and set a cut-off at 4,300 g, you’d pick up 93%. … but at false positive rate of 38%,” he said.

While not perfect, the AC alone is as accurate as more complicated formulas to detect macrosomic fetuses, he emphasized. “It’s a tough [measurement] to get just before the baby is born, but you can do it a little bit earlier,” he said. Research has shown that screening at 30-34 weeks can capture a majority of the fetuses destined to be greater than 4,000 g at birth, with a lower false-positive rate.

He pointed to one “very interesting” recent study in which AC was measured with a handheld ultrasound device at 24-40 weeks’ gestation, prior to formal ultrasound estimation of EFW. Early AC was a better predictor of large-for-gestational age babies at birth than EFW or early fundal height measurement, with sensitivities of 67%, 25%, and 50%, respectively (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;212[6]:820.e1-8).

“And AC had a false-positive rate of only 10%,” Dr. Hobbins said.

Macrosomia occurs in 20% of cases of gestational diabetes and 25% of pregestational diabetes, he said. “And even if there is adequate glucose control, 17% will be macrosomic.”

The condition correlates with childhood and adulthood metabolic dysfunction and is associated with significantly increased risk of birth injury to the infant and to the mother. The alternative – cesarean delivery – is “not innocuous,” and “[we have] a very low threshold for cesarean if macrosomia is suspected,” Dr. Hobbins said.

Dr. Hobbins reported having no financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – , John C. Hobbins, MD, said at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“Everything that the estimated fetal weight [EFW] can do, the abdominal circumference can do better,” especially in diabetic mothers, said Dr. Hobbins, who is widely regarded as one of the early pioneers in the development and use of obstetric ultrasound as a diagnostic tool.

Because it reflects liver size and incorporates subcutaneous fat, the abdominal circumference (AC) “concentrates on where the action is,” he said. It also “roughly correlates” with the size of the fetal shoulders and is not affected by genetic factors.

Moreover, “it focuses on one task rather than putting into play four variables, each with its own standard error of the method,” said Dr. Hobbins, referring to the four fetal biometric parameters incorporated into the Hadlock formula for EFW that is provided “upon fire-up of virtually every ultrasound machine.”

These four parameters (biparietal diameter, head circumference, femur length, and AC) each contribute to fetal weight but the AC has been shown to correlate better with weight at birth than the other variables, and it is the only measure that reflects how corpulent the fetus is, he noted.

The “general rule of thumb is that the EFW [as calculated by ultrasound machine–based equations] has a standard error of the method of plus or minus 10%. … which means that an EFW of 4,000 g is associated with a splay of plus or minus 1.2 pounds,” said Dr. Hobbins, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“But the problem for us is not the failure of the ultrasound – it’s the way we use it,” he said.

An assortment of customized formulas have been developed for macrosomia, including one designed for use in diabetes that incorporates AC, head circumference, femur length, and 3D volumes of the thigh and abdomen. “If one used this and set a cut-off at 4,300 g, you’d pick up 93%. … but at false positive rate of 38%,” he said.

While not perfect, the AC alone is as accurate as more complicated formulas to detect macrosomic fetuses, he emphasized. “It’s a tough [measurement] to get just before the baby is born, but you can do it a little bit earlier,” he said. Research has shown that screening at 30-34 weeks can capture a majority of the fetuses destined to be greater than 4,000 g at birth, with a lower false-positive rate.

He pointed to one “very interesting” recent study in which AC was measured with a handheld ultrasound device at 24-40 weeks’ gestation, prior to formal ultrasound estimation of EFW. Early AC was a better predictor of large-for-gestational age babies at birth than EFW or early fundal height measurement, with sensitivities of 67%, 25%, and 50%, respectively (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;212[6]:820.e1-8).

“And AC had a false-positive rate of only 10%,” Dr. Hobbins said.

Macrosomia occurs in 20% of cases of gestational diabetes and 25% of pregestational diabetes, he said. “And even if there is adequate glucose control, 17% will be macrosomic.”

The condition correlates with childhood and adulthood metabolic dysfunction and is associated with significantly increased risk of birth injury to the infant and to the mother. The alternative – cesarean delivery – is “not innocuous,” and “[we have] a very low threshold for cesarean if macrosomia is suspected,” Dr. Hobbins said.

Dr. Hobbins reported having no financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – , John C. Hobbins, MD, said at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“Everything that the estimated fetal weight [EFW] can do, the abdominal circumference can do better,” especially in diabetic mothers, said Dr. Hobbins, who is widely regarded as one of the early pioneers in the development and use of obstetric ultrasound as a diagnostic tool.

Because it reflects liver size and incorporates subcutaneous fat, the abdominal circumference (AC) “concentrates on where the action is,” he said. It also “roughly correlates” with the size of the fetal shoulders and is not affected by genetic factors.

Moreover, “it focuses on one task rather than putting into play four variables, each with its own standard error of the method,” said Dr. Hobbins, referring to the four fetal biometric parameters incorporated into the Hadlock formula for EFW that is provided “upon fire-up of virtually every ultrasound machine.”

These four parameters (biparietal diameter, head circumference, femur length, and AC) each contribute to fetal weight but the AC has been shown to correlate better with weight at birth than the other variables, and it is the only measure that reflects how corpulent the fetus is, he noted.

The “general rule of thumb is that the EFW [as calculated by ultrasound machine–based equations] has a standard error of the method of plus or minus 10%. … which means that an EFW of 4,000 g is associated with a splay of plus or minus 1.2 pounds,” said Dr. Hobbins, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“But the problem for us is not the failure of the ultrasound – it’s the way we use it,” he said.

An assortment of customized formulas have been developed for macrosomia, including one designed for use in diabetes that incorporates AC, head circumference, femur length, and 3D volumes of the thigh and abdomen. “If one used this and set a cut-off at 4,300 g, you’d pick up 93%. … but at false positive rate of 38%,” he said.

While not perfect, the AC alone is as accurate as more complicated formulas to detect macrosomic fetuses, he emphasized. “It’s a tough [measurement] to get just before the baby is born, but you can do it a little bit earlier,” he said. Research has shown that screening at 30-34 weeks can capture a majority of the fetuses destined to be greater than 4,000 g at birth, with a lower false-positive rate.

He pointed to one “very interesting” recent study in which AC was measured with a handheld ultrasound device at 24-40 weeks’ gestation, prior to formal ultrasound estimation of EFW. Early AC was a better predictor of large-for-gestational age babies at birth than EFW or early fundal height measurement, with sensitivities of 67%, 25%, and 50%, respectively (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jun;212[6]:820.e1-8).

“And AC had a false-positive rate of only 10%,” Dr. Hobbins said.

Macrosomia occurs in 20% of cases of gestational diabetes and 25% of pregestational diabetes, he said. “And even if there is adequate glucose control, 17% will be macrosomic.”

The condition correlates with childhood and adulthood metabolic dysfunction and is associated with significantly increased risk of birth injury to the infant and to the mother. The alternative – cesarean delivery – is “not innocuous,” and “[we have] a very low threshold for cesarean if macrosomia is suspected,” Dr. Hobbins said.

Dr. Hobbins reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DPSG-NA 2017

VIDEO: Laparoscopy is a safe approach throughout pregnancy, expert says

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopy offers advantages over laparotomy when performing nonobstetrical surgery on pregnant women, Yuval Kaufman, MD, said at the AAGL Global Congress.

“When we talk about advantages in referral to the pregnant patient, one of the most important things is early ambulation,” Dr. Kaufman, a gynecologic surgeon at Carmel Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said in an interview. “These patients are in a hypercoagulable state; they are more likely to have DVT and PE. You need them up and running as soon as possible.”

Laparoscopy also tends to be better in terms of handling of the uterus, offering a field of view so that the uterus doesn’t need to be moved as much. In addition, laparoscopy is associated with a smaller, more easily healed scar, and usually requires fewer analgesics, which is better for the fetus, he said.

The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons recently issued guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy, advising surgeons that these procedures can be safely performed during any trimester when the operation is indicated, he said.

“There was an older misconception that surgery has to be done in the second trimester only,” Dr. Kaufman said. “But they actually contradict that; they show that if you postpone surgery for this reason you might be doing much more damage to the mother and to the fetus.”

Dr. Kaufman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopy offers advantages over laparotomy when performing nonobstetrical surgery on pregnant women, Yuval Kaufman, MD, said at the AAGL Global Congress.

“When we talk about advantages in referral to the pregnant patient, one of the most important things is early ambulation,” Dr. Kaufman, a gynecologic surgeon at Carmel Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said in an interview. “These patients are in a hypercoagulable state; they are more likely to have DVT and PE. You need them up and running as soon as possible.”

Laparoscopy also tends to be better in terms of handling of the uterus, offering a field of view so that the uterus doesn’t need to be moved as much. In addition, laparoscopy is associated with a smaller, more easily healed scar, and usually requires fewer analgesics, which is better for the fetus, he said.

The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons recently issued guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy, advising surgeons that these procedures can be safely performed during any trimester when the operation is indicated, he said.

“There was an older misconception that surgery has to be done in the second trimester only,” Dr. Kaufman said. “But they actually contradict that; they show that if you postpone surgery for this reason you might be doing much more damage to the mother and to the fetus.”

Dr. Kaufman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopy offers advantages over laparotomy when performing nonobstetrical surgery on pregnant women, Yuval Kaufman, MD, said at the AAGL Global Congress.

“When we talk about advantages in referral to the pregnant patient, one of the most important things is early ambulation,” Dr. Kaufman, a gynecologic surgeon at Carmel Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, said in an interview. “These patients are in a hypercoagulable state; they are more likely to have DVT and PE. You need them up and running as soon as possible.”

Laparoscopy also tends to be better in terms of handling of the uterus, offering a field of view so that the uterus doesn’t need to be moved as much. In addition, laparoscopy is associated with a smaller, more easily healed scar, and usually requires fewer analgesics, which is better for the fetus, he said.

The Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons recently issued guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy, advising surgeons that these procedures can be safely performed during any trimester when the operation is indicated, he said.

“There was an older misconception that surgery has to be done in the second trimester only,” Dr. Kaufman said. “But they actually contradict that; they show that if you postpone surgery for this reason you might be doing much more damage to the mother and to the fetus.”

Dr. Kaufman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

AT AAGL 2017

Experts question insulin as top choice in GDM

WASHINGTON – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ conclusion that insulin should be considered the first-line pharmacologic treatment for gestational diabetes came under fire at a recent meeting on diabetes in pregnancy, indicating the extent to which controversy persists over the use of oral antidiabetic medications in pregnancy.

“Like many others, I’m perplexed by the strong endorsement,” Mark Landon, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State University, Columbus, said during an open discussion of oral hypoglycemic agents held at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Landon and several other researchers and experts in diabetes in pregnancy expressed discontent with any firm prioritization of the drugs most commonly used for gestational diabetes, saying that there are not yet enough data to do so.

The endorsement of insulin as the first-line option when pharmacologic treatment is needed is a level A conclusion/recommendation in ACOG’s updated practice bulletin on gestational diabetes mellitus, released in July 2017 (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130[1]:e17-37). In accompanying level B recommendations, ACOG stated that in women who decline insulin therapy or who are believed to be “unable to safely administer insulin,” metformin is a “reasonable second-line choice.” Glyburide “should not be recommended as a first-line pharmacologic treatment because, in most studies, it does not yield equivalent outcomes to insulin.”

Level A recommendations are defined as “based on good and consistent scientific evidence,” while the evidence for level B recommendations is “limited or inconsistent.”

Asked to comment on the concerns voiced at the meeting, an ACOG spokeswoman said that the recommendations were developed after a thorough literature review, but that the evidence was being reexamined with the option of updating the practice bulletin.

Current recommendations

In its practice bulletin, ACOG noted that oral antidiabetic medications, such as glyburide and metformin, are increasingly used among women with GDM, despite not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication and even though insulin continues to be the recommended as first-line therapy by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The ADA, in a summary of its 2017 guideline on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, stated that insulin is the “preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus, as it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent.” Metformin and glyburide are options, “but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide” (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl 1]:S114- 9).Regarding metformin, the ACOG bulletin cited two trials that randomized women to metformin or insulin – one in which both groups experienced similar rates of a composite outcome of perinatal morbidity, and another in which women receiving metformin had lower mean glucose levels, less gestational weight gain, and neonates with lower rates of hypoglycemia.

ACOG also cited a meta-analysis, that found “minimal differences” between neonates of women randomized to metformin versus insulin, but also noted that “interestingly, women randomized to metformin experienced a higher rate of preterm birth” and a lower rate of gestational hypertension (BMJ. 2015;350:h102).

With respect to glyburide, the ACOG bulletin said that two recent meta-analyses had demonstrated worse neonatal outcomes with glyburide, compared with insulin, and that observational studies have shown higher rates of preeclampsia, hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth with the use of glyburide, compared with insulin. However, many other outcomes have not been statistically significantly different, according to the practice bulletin.

Additionally, at least 4%-16% of women eventually require the addition of insulin when glyburide is used as initial treatment, as do 26%-46% of women who take metformin, according to ACOG.

Regarding placental transfer, ACOG’s bulletin said that while one study that analyzed umbilical cord blood revealed no detectable glyburide in exposed pregnancies, another study demonstrated that glyburide does cross the placenta. Metformin has also been found to cross the placenta, with the fetus exposed to concentrations similar to maternal levels, the bulletin noted.

“Although current data demonstrate no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal health from oral diabetic therapy during pregnancy, long-term outcomes are not yet available,” ACOG wrote in the practice bulletin.

Concerns about research

As Thomas Moore, MD, sees it, the quality of available data is insufficient to recommend insulin over oral agents, or one oral agent over another. “We really need to focus [the National Institutes of Health] on putting together proper studies,” he said at the meeting.

In a later interview, Dr. Moore referred to two recent Cochrane reviews. One review, published in January 2017, analyzed eight studies of oral antidiabetic therapies for GDM and concluded there was “insufficient high-quality evidence to be able to draw any meaningful conclusions as to the benefits of one oral antidiabetic pharmacological therapy over another” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 25;1:CD011967).

The other Cochrane review, published in November 2017, concluded that insulin and oral antidiabetic agents have similar effects on key health outcomes, and that each one has minimal harms. The quality of evidence, the authors said, ranged from “very low to moderate, with downgrading decisions due to imprecision, risk of bias, and inconsistency” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 5;11:CD012037).

Dr. Moore, professor of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, San Diego, cautioned against presuming that placental transfer of an antidiabetic drug is “ipso facto dangerous or terrible.” Moreover, he said that it’s not yet clear whether glyburide crosses the placenta in the first place.

Dr. Moore, Dr. Landon, and others at the meeting said they are eagerly awaiting long-term follow-up data from the Metformin in Gestational Diabetes (MiG) trial underway in Australia. The prospective randomized trial is designed to compare metformin with insulin and finished recruiting women in 2006. A recently published analysis found similar neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring at 2 years, but it’s the longer-term data looking into early puberty that experts now want to see (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309602).

In the meantime, Dr. Landon said the “short-term safety record for oral antidiabetic medications is actually pretty good.” There are studies “suggesting an increased risk for large babies with glyburide, but these are very small RCTs [randomized controlled trials],” he said in an interview.

Data from population-based studies, moreover, are “flawed in as much as we don’t know the thresholds for initiating glyburide treatment, nor do we know whether the women were really good candidates for this therapy,” Dr. Landon said. “It’s conceivable, and it’s been my experience, that glyburide has been overprescribed and inappropriately prescribed in certain women with GDM who really should receive insulin therapy.”

Whether glyburide and metformin are being prescribed for GDM in optimal doses is another growing question – one that interests Steve N. Caritis, MD. The drugs are typically prescribed to be taken twice a day every 12 hours, but he said he is finding that some patients may need more frequent, individually tailored dosing.

“We may have come to conclusions in [the studies published thus far] that may not be the correct conclusions,” Dr. Caritis, who coleads obstetric pharmacology research at the Magee-Womens Research Institute in Pittsburgh, said at the DPSG meeting. “The question is, If the dosing were appropriate, would we have the same outcomes?”

“We were asked, Are people using [oral antidiabetic medications] properly? Could the fact that glyburide may not have had the efficacy we’d hoped for [in published studies] be due to it not being used properly?” Dr. Catalano said.

Individualizing drug choice

Dosing aside, there may be populations of women who respond poorly to a medication because of the underlying pathophysiology of their GDM, said Maisa N. Feghali, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

A study published in 2016 demonstrated the heterogeneity of the physiologic processes underlying hyperglycemia in 67 women with GDM. Almost one-third of women with GDM had predominant insulin secretion deficit, one-half had predominant insulin resistance, and the remaining 20% had a mixed “metabolic profile” (Diabetes Care. 2016 Jun;39[6]:1052-5).

This study prompted Dr. Feghali and her colleagues to design a pilot study aimed at testing an individualized approach that matches treatment to GDM mechanism. “We [currently] have the expectation that all glucose-lowering agents will be similarly effective despite significant variation in underlying GDM pathophysiology,” she said during a presentation at the DPSG meeting. “But I think we have a mismatch between variations in GDM and the uniformity of treatment.”

In her pilot study, women diagnosed with GDM who fail dietary control will be randomized into usual treatment or matched treatment (metformin for predominant insulin resistance, glyburide or insulin for predominant insulin secretion defects, and one of the three for combined insulin resistance and insulin secretion defects).

The MATCh-GDM study (Metabolic Analysis for Treatment Choice of GDM) is just getting underway. Patients will be monitored for consistency of GDM mechanism and glucose control, and routine clinical variables (hypertensive diseases, cesarean delivery, and birth weight) will be studied, as well as neonatal body composition, cord blood glucose, and cord blood C-peptide.

WASHINGTON – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ conclusion that insulin should be considered the first-line pharmacologic treatment for gestational diabetes came under fire at a recent meeting on diabetes in pregnancy, indicating the extent to which controversy persists over the use of oral antidiabetic medications in pregnancy.

“Like many others, I’m perplexed by the strong endorsement,” Mark Landon, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State University, Columbus, said during an open discussion of oral hypoglycemic agents held at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Landon and several other researchers and experts in diabetes in pregnancy expressed discontent with any firm prioritization of the drugs most commonly used for gestational diabetes, saying that there are not yet enough data to do so.

The endorsement of insulin as the first-line option when pharmacologic treatment is needed is a level A conclusion/recommendation in ACOG’s updated practice bulletin on gestational diabetes mellitus, released in July 2017 (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130[1]:e17-37). In accompanying level B recommendations, ACOG stated that in women who decline insulin therapy or who are believed to be “unable to safely administer insulin,” metformin is a “reasonable second-line choice.” Glyburide “should not be recommended as a first-line pharmacologic treatment because, in most studies, it does not yield equivalent outcomes to insulin.”

Level A recommendations are defined as “based on good and consistent scientific evidence,” while the evidence for level B recommendations is “limited or inconsistent.”

Asked to comment on the concerns voiced at the meeting, an ACOG spokeswoman said that the recommendations were developed after a thorough literature review, but that the evidence was being reexamined with the option of updating the practice bulletin.

Current recommendations

In its practice bulletin, ACOG noted that oral antidiabetic medications, such as glyburide and metformin, are increasingly used among women with GDM, despite not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication and even though insulin continues to be the recommended as first-line therapy by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The ADA, in a summary of its 2017 guideline on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, stated that insulin is the “preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus, as it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent.” Metformin and glyburide are options, “but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide” (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl 1]:S114- 9).Regarding metformin, the ACOG bulletin cited two trials that randomized women to metformin or insulin – one in which both groups experienced similar rates of a composite outcome of perinatal morbidity, and another in which women receiving metformin had lower mean glucose levels, less gestational weight gain, and neonates with lower rates of hypoglycemia.

ACOG also cited a meta-analysis, that found “minimal differences” between neonates of women randomized to metformin versus insulin, but also noted that “interestingly, women randomized to metformin experienced a higher rate of preterm birth” and a lower rate of gestational hypertension (BMJ. 2015;350:h102).

With respect to glyburide, the ACOG bulletin said that two recent meta-analyses had demonstrated worse neonatal outcomes with glyburide, compared with insulin, and that observational studies have shown higher rates of preeclampsia, hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth with the use of glyburide, compared with insulin. However, many other outcomes have not been statistically significantly different, according to the practice bulletin.

Additionally, at least 4%-16% of women eventually require the addition of insulin when glyburide is used as initial treatment, as do 26%-46% of women who take metformin, according to ACOG.

Regarding placental transfer, ACOG’s bulletin said that while one study that analyzed umbilical cord blood revealed no detectable glyburide in exposed pregnancies, another study demonstrated that glyburide does cross the placenta. Metformin has also been found to cross the placenta, with the fetus exposed to concentrations similar to maternal levels, the bulletin noted.

“Although current data demonstrate no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal health from oral diabetic therapy during pregnancy, long-term outcomes are not yet available,” ACOG wrote in the practice bulletin.

Concerns about research

As Thomas Moore, MD, sees it, the quality of available data is insufficient to recommend insulin over oral agents, or one oral agent over another. “We really need to focus [the National Institutes of Health] on putting together proper studies,” he said at the meeting.

In a later interview, Dr. Moore referred to two recent Cochrane reviews. One review, published in January 2017, analyzed eight studies of oral antidiabetic therapies for GDM and concluded there was “insufficient high-quality evidence to be able to draw any meaningful conclusions as to the benefits of one oral antidiabetic pharmacological therapy over another” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 25;1:CD011967).

The other Cochrane review, published in November 2017, concluded that insulin and oral antidiabetic agents have similar effects on key health outcomes, and that each one has minimal harms. The quality of evidence, the authors said, ranged from “very low to moderate, with downgrading decisions due to imprecision, risk of bias, and inconsistency” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 5;11:CD012037).

Dr. Moore, professor of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, San Diego, cautioned against presuming that placental transfer of an antidiabetic drug is “ipso facto dangerous or terrible.” Moreover, he said that it’s not yet clear whether glyburide crosses the placenta in the first place.

Dr. Moore, Dr. Landon, and others at the meeting said they are eagerly awaiting long-term follow-up data from the Metformin in Gestational Diabetes (MiG) trial underway in Australia. The prospective randomized trial is designed to compare metformin with insulin and finished recruiting women in 2006. A recently published analysis found similar neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring at 2 years, but it’s the longer-term data looking into early puberty that experts now want to see (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309602).

In the meantime, Dr. Landon said the “short-term safety record for oral antidiabetic medications is actually pretty good.” There are studies “suggesting an increased risk for large babies with glyburide, but these are very small RCTs [randomized controlled trials],” he said in an interview.

Data from population-based studies, moreover, are “flawed in as much as we don’t know the thresholds for initiating glyburide treatment, nor do we know whether the women were really good candidates for this therapy,” Dr. Landon said. “It’s conceivable, and it’s been my experience, that glyburide has been overprescribed and inappropriately prescribed in certain women with GDM who really should receive insulin therapy.”

Whether glyburide and metformin are being prescribed for GDM in optimal doses is another growing question – one that interests Steve N. Caritis, MD. The drugs are typically prescribed to be taken twice a day every 12 hours, but he said he is finding that some patients may need more frequent, individually tailored dosing.

“We may have come to conclusions in [the studies published thus far] that may not be the correct conclusions,” Dr. Caritis, who coleads obstetric pharmacology research at the Magee-Womens Research Institute in Pittsburgh, said at the DPSG meeting. “The question is, If the dosing were appropriate, would we have the same outcomes?”

“We were asked, Are people using [oral antidiabetic medications] properly? Could the fact that glyburide may not have had the efficacy we’d hoped for [in published studies] be due to it not being used properly?” Dr. Catalano said.

Individualizing drug choice

Dosing aside, there may be populations of women who respond poorly to a medication because of the underlying pathophysiology of their GDM, said Maisa N. Feghali, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

A study published in 2016 demonstrated the heterogeneity of the physiologic processes underlying hyperglycemia in 67 women with GDM. Almost one-third of women with GDM had predominant insulin secretion deficit, one-half had predominant insulin resistance, and the remaining 20% had a mixed “metabolic profile” (Diabetes Care. 2016 Jun;39[6]:1052-5).

This study prompted Dr. Feghali and her colleagues to design a pilot study aimed at testing an individualized approach that matches treatment to GDM mechanism. “We [currently] have the expectation that all glucose-lowering agents will be similarly effective despite significant variation in underlying GDM pathophysiology,” she said during a presentation at the DPSG meeting. “But I think we have a mismatch between variations in GDM and the uniformity of treatment.”

In her pilot study, women diagnosed with GDM who fail dietary control will be randomized into usual treatment or matched treatment (metformin for predominant insulin resistance, glyburide or insulin for predominant insulin secretion defects, and one of the three for combined insulin resistance and insulin secretion defects).

The MATCh-GDM study (Metabolic Analysis for Treatment Choice of GDM) is just getting underway. Patients will be monitored for consistency of GDM mechanism and glucose control, and routine clinical variables (hypertensive diseases, cesarean delivery, and birth weight) will be studied, as well as neonatal body composition, cord blood glucose, and cord blood C-peptide.

WASHINGTON – The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ conclusion that insulin should be considered the first-line pharmacologic treatment for gestational diabetes came under fire at a recent meeting on diabetes in pregnancy, indicating the extent to which controversy persists over the use of oral antidiabetic medications in pregnancy.

“Like many others, I’m perplexed by the strong endorsement,” Mark Landon, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Ohio State University, Columbus, said during an open discussion of oral hypoglycemic agents held at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Landon and several other researchers and experts in diabetes in pregnancy expressed discontent with any firm prioritization of the drugs most commonly used for gestational diabetes, saying that there are not yet enough data to do so.

The endorsement of insulin as the first-line option when pharmacologic treatment is needed is a level A conclusion/recommendation in ACOG’s updated practice bulletin on gestational diabetes mellitus, released in July 2017 (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130[1]:e17-37). In accompanying level B recommendations, ACOG stated that in women who decline insulin therapy or who are believed to be “unable to safely administer insulin,” metformin is a “reasonable second-line choice.” Glyburide “should not be recommended as a first-line pharmacologic treatment because, in most studies, it does not yield equivalent outcomes to insulin.”

Level A recommendations are defined as “based on good and consistent scientific evidence,” while the evidence for level B recommendations is “limited or inconsistent.”

Asked to comment on the concerns voiced at the meeting, an ACOG spokeswoman said that the recommendations were developed after a thorough literature review, but that the evidence was being reexamined with the option of updating the practice bulletin.

Current recommendations

In its practice bulletin, ACOG noted that oral antidiabetic medications, such as glyburide and metformin, are increasingly used among women with GDM, despite not being approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this indication and even though insulin continues to be the recommended as first-line therapy by the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

The ADA, in a summary of its 2017 guideline on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, stated that insulin is the “preferred medication for treating hyperglycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus, as it does not cross the placenta to a measurable extent.” Metformin and glyburide are options, “but both cross the placenta to the fetus, with metformin likely crossing to a greater extent than glyburide” (Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40[Suppl 1]:S114- 9).Regarding metformin, the ACOG bulletin cited two trials that randomized women to metformin or insulin – one in which both groups experienced similar rates of a composite outcome of perinatal morbidity, and another in which women receiving metformin had lower mean glucose levels, less gestational weight gain, and neonates with lower rates of hypoglycemia.

ACOG also cited a meta-analysis, that found “minimal differences” between neonates of women randomized to metformin versus insulin, but also noted that “interestingly, women randomized to metformin experienced a higher rate of preterm birth” and a lower rate of gestational hypertension (BMJ. 2015;350:h102).

With respect to glyburide, the ACOG bulletin said that two recent meta-analyses had demonstrated worse neonatal outcomes with glyburide, compared with insulin, and that observational studies have shown higher rates of preeclampsia, hyperbilirubinemia, and stillbirth with the use of glyburide, compared with insulin. However, many other outcomes have not been statistically significantly different, according to the practice bulletin.

Additionally, at least 4%-16% of women eventually require the addition of insulin when glyburide is used as initial treatment, as do 26%-46% of women who take metformin, according to ACOG.

Regarding placental transfer, ACOG’s bulletin said that while one study that analyzed umbilical cord blood revealed no detectable glyburide in exposed pregnancies, another study demonstrated that glyburide does cross the placenta. Metformin has also been found to cross the placenta, with the fetus exposed to concentrations similar to maternal levels, the bulletin noted.

“Although current data demonstrate no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal health from oral diabetic therapy during pregnancy, long-term outcomes are not yet available,” ACOG wrote in the practice bulletin.

Concerns about research

As Thomas Moore, MD, sees it, the quality of available data is insufficient to recommend insulin over oral agents, or one oral agent over another. “We really need to focus [the National Institutes of Health] on putting together proper studies,” he said at the meeting.

In a later interview, Dr. Moore referred to two recent Cochrane reviews. One review, published in January 2017, analyzed eight studies of oral antidiabetic therapies for GDM and concluded there was “insufficient high-quality evidence to be able to draw any meaningful conclusions as to the benefits of one oral antidiabetic pharmacological therapy over another” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 25;1:CD011967).

The other Cochrane review, published in November 2017, concluded that insulin and oral antidiabetic agents have similar effects on key health outcomes, and that each one has minimal harms. The quality of evidence, the authors said, ranged from “very low to moderate, with downgrading decisions due to imprecision, risk of bias, and inconsistency” (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Nov 5;11:CD012037).

Dr. Moore, professor of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of California, San Diego, cautioned against presuming that placental transfer of an antidiabetic drug is “ipso facto dangerous or terrible.” Moreover, he said that it’s not yet clear whether glyburide crosses the placenta in the first place.

Dr. Moore, Dr. Landon, and others at the meeting said they are eagerly awaiting long-term follow-up data from the Metformin in Gestational Diabetes (MiG) trial underway in Australia. The prospective randomized trial is designed to compare metformin with insulin and finished recruiting women in 2006. A recently published analysis found similar neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring at 2 years, but it’s the longer-term data looking into early puberty that experts now want to see (Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016 Feb 24. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309602).

In the meantime, Dr. Landon said the “short-term safety record for oral antidiabetic medications is actually pretty good.” There are studies “suggesting an increased risk for large babies with glyburide, but these are very small RCTs [randomized controlled trials],” he said in an interview.

Data from population-based studies, moreover, are “flawed in as much as we don’t know the thresholds for initiating glyburide treatment, nor do we know whether the women were really good candidates for this therapy,” Dr. Landon said. “It’s conceivable, and it’s been my experience, that glyburide has been overprescribed and inappropriately prescribed in certain women with GDM who really should receive insulin therapy.”

Whether glyburide and metformin are being prescribed for GDM in optimal doses is another growing question – one that interests Steve N. Caritis, MD. The drugs are typically prescribed to be taken twice a day every 12 hours, but he said he is finding that some patients may need more frequent, individually tailored dosing.

“We may have come to conclusions in [the studies published thus far] that may not be the correct conclusions,” Dr. Caritis, who coleads obstetric pharmacology research at the Magee-Womens Research Institute in Pittsburgh, said at the DPSG meeting. “The question is, If the dosing were appropriate, would we have the same outcomes?”

“We were asked, Are people using [oral antidiabetic medications] properly? Could the fact that glyburide may not have had the efficacy we’d hoped for [in published studies] be due to it not being used properly?” Dr. Catalano said.

Individualizing drug choice

Dosing aside, there may be populations of women who respond poorly to a medication because of the underlying pathophysiology of their GDM, said Maisa N. Feghali, MD, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

A study published in 2016 demonstrated the heterogeneity of the physiologic processes underlying hyperglycemia in 67 women with GDM. Almost one-third of women with GDM had predominant insulin secretion deficit, one-half had predominant insulin resistance, and the remaining 20% had a mixed “metabolic profile” (Diabetes Care. 2016 Jun;39[6]:1052-5).

This study prompted Dr. Feghali and her colleagues to design a pilot study aimed at testing an individualized approach that matches treatment to GDM mechanism. “We [currently] have the expectation that all glucose-lowering agents will be similarly effective despite significant variation in underlying GDM pathophysiology,” she said during a presentation at the DPSG meeting. “But I think we have a mismatch between variations in GDM and the uniformity of treatment.”

In her pilot study, women diagnosed with GDM who fail dietary control will be randomized into usual treatment or matched treatment (metformin for predominant insulin resistance, glyburide or insulin for predominant insulin secretion defects, and one of the three for combined insulin resistance and insulin secretion defects).

The MATCh-GDM study (Metabolic Analysis for Treatment Choice of GDM) is just getting underway. Patients will be monitored for consistency of GDM mechanism and glucose control, and routine clinical variables (hypertensive diseases, cesarean delivery, and birth weight) will be studied, as well as neonatal body composition, cord blood glucose, and cord blood C-peptide.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DPSG-NA 2017

Pregnant women’s access to vaccination website, social media improved infants’ up-to-date immunizations

than were those receiving usual care, said Jason M. Glanz, PhD, of the Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, and his associates.

“These results suggest that interactive, informational interventions administered outside of the physician’s office can improve vaccine acceptance,” the investigators said. “The information appears to be effective when presented to parents before their children are born.”

The women in the VSM group had access to vaccine content, social media technologies that included a blog, discussion forum, chat rooms with experts, and “Ask a Question” portal through which the women could directly ask experts questions about vaccination. The experts were a pediatrician, a vaccine safety researcher, and a risk communication specialist.

Monthly, one to two blog posts were created on topics such as new vaccine safety research, vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, changes in immunization policy, and the importance of adhering to the recommended immunization schedule, the researchers said. The women also could submit questions privately through e-mail, and receive personalized responses within 2 business days.

At the end of 200 days of follow-up, the proportion of infants up to date with their vaccinations were 93% for the VSM group, 91% for the VI group, and 87% for the UC arms. Infants in the VSM group were more likely to be up to date at age 200 days, compared with infants in the UC group (odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-3.47).

“Up-to-date status did not differ significantly between the VI and UC arms or the VSM and VI arms,” Dr. Glanz and his associates wrote.

Of 739 women in the VSM and VI groups, 35% visited the website at least once, with a mean of 1.8 visits (range, 1-15 visits). Of 75 vaccine-hesitant women, 44% visited the website, compared with 34% of 664 nonhesitant women. Median vaccine hesitancy scores were 13 for the VSM group, 17 for the VI group, and 15 for the UC group.

The study authors had no relevant disclosures.

Read more in Pediatrics (2017 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1117).

than were those receiving usual care, said Jason M. Glanz, PhD, of the Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, and his associates.

“These results suggest that interactive, informational interventions administered outside of the physician’s office can improve vaccine acceptance,” the investigators said. “The information appears to be effective when presented to parents before their children are born.”

The women in the VSM group had access to vaccine content, social media technologies that included a blog, discussion forum, chat rooms with experts, and “Ask a Question” portal through which the women could directly ask experts questions about vaccination. The experts were a pediatrician, a vaccine safety researcher, and a risk communication specialist.

Monthly, one to two blog posts were created on topics such as new vaccine safety research, vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, changes in immunization policy, and the importance of adhering to the recommended immunization schedule, the researchers said. The women also could submit questions privately through e-mail, and receive personalized responses within 2 business days.

At the end of 200 days of follow-up, the proportion of infants up to date with their vaccinations were 93% for the VSM group, 91% for the VI group, and 87% for the UC arms. Infants in the VSM group were more likely to be up to date at age 200 days, compared with infants in the UC group (odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-3.47).

“Up-to-date status did not differ significantly between the VI and UC arms or the VSM and VI arms,” Dr. Glanz and his associates wrote.

Of 739 women in the VSM and VI groups, 35% visited the website at least once, with a mean of 1.8 visits (range, 1-15 visits). Of 75 vaccine-hesitant women, 44% visited the website, compared with 34% of 664 nonhesitant women. Median vaccine hesitancy scores were 13 for the VSM group, 17 for the VI group, and 15 for the UC group.

The study authors had no relevant disclosures.

Read more in Pediatrics (2017 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1117).

than were those receiving usual care, said Jason M. Glanz, PhD, of the Institute for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, and his associates.

“These results suggest that interactive, informational interventions administered outside of the physician’s office can improve vaccine acceptance,” the investigators said. “The information appears to be effective when presented to parents before their children are born.”

The women in the VSM group had access to vaccine content, social media technologies that included a blog, discussion forum, chat rooms with experts, and “Ask a Question” portal through which the women could directly ask experts questions about vaccination. The experts were a pediatrician, a vaccine safety researcher, and a risk communication specialist.

Monthly, one to two blog posts were created on topics such as new vaccine safety research, vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, changes in immunization policy, and the importance of adhering to the recommended immunization schedule, the researchers said. The women also could submit questions privately through e-mail, and receive personalized responses within 2 business days.

At the end of 200 days of follow-up, the proportion of infants up to date with their vaccinations were 93% for the VSM group, 91% for the VI group, and 87% for the UC arms. Infants in the VSM group were more likely to be up to date at age 200 days, compared with infants in the UC group (odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-3.47).

“Up-to-date status did not differ significantly between the VI and UC arms or the VSM and VI arms,” Dr. Glanz and his associates wrote.

Of 739 women in the VSM and VI groups, 35% visited the website at least once, with a mean of 1.8 visits (range, 1-15 visits). Of 75 vaccine-hesitant women, 44% visited the website, compared with 34% of 664 nonhesitant women. Median vaccine hesitancy scores were 13 for the VSM group, 17 for the VI group, and 15 for the UC group.

The study authors had no relevant disclosures.

Read more in Pediatrics (2017 Nov. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1117).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Don’t let GDM history limit contraception choices

WASHINGTON – Women with a history of gestational diabetes can use any contraceptive method safely, and those with uncomplicated pregestational diabetes can also consider all methods, said Anne Burke, MD, director of the family planning division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“The real cautions, and some red lights,” apply to those with vascular sequelae, diabetes of 20 years’ duration or more, and patients with other vascular disease in addition to diabetes, she said at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“The contraception options for women with diabetes aren’t necessarily terribly limited compared to the options for other women,” Dr. Burke said. “And the big take home is that, across the board, .”

The U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assign a 1-4 rating for each method for women with certain characteristics or medical conditions. Category 1 indicates no restrictions, and category 2 means that the advantages generally outweigh theoretical or proven risks. Category 3 indicates that such risks usually outweigh the advantages, and category 4 means there is an unacceptable risk.

The assignment to category 2 instead of category 1 can reflect either limitations in the overall amount of data available or the lack of strong randomized studies “whereas the data [otherwise] seem to support safety,” Dr. Burke said. “And sometimes, it relates to most studies saying one thing and another being a little inconsistent.”

Uncomplicated pregestational diabetes

This is important to understand because all the methods for women with uncomplicated pregestational diabetes (no evidence of vascular disease or end-organ damage) are classified as category 2, except for the copper IUD and emergency contraception, which are in category 1. The document distinguishes between insulin-dependent and non–insulin-dependent diabetes, but the recommendations do not differ between the two categories, she said.

Progestin-only contraceptives appear to have little effect on short- or long-term diabetes control, hemostatic markers, or the lipid profile in women with uncomplicated diabetes. Combined hormonal contraception appears to have no effect on long-term diabetes control or progression to retinopathy; there may be changes in the lipid profile and hemostatic markers, but “mostly within normal values, and in some cases, in a favorable direction,” said Dr. Burke of the department of gynecology and obstetrics at the university.

GDM history

In women who have had gestational diabetes, all methods are in category 1 of the Medical Eligibility Criteria (MEC). While “there have been a couple of question marks” with progestin-only contraceptives and the later development of diabetes, “it seems that there’s really not an increased risk,” she said. Nor does there seem to be an increased risk of developing later diabetes with combined hormonal contraception.

In general, the data backing the MEC come from a limited number of studies, and “few that are rigorously done,” she said. “So the recommendations reflect consensus [that is] based on the best available information.”

Severe or long-standing disease

Data are especially limited for women with more severe and/or long-standing disease, as these women have been excluded from studies. There is enough knowledge, however, to make the hypoestrogenic effects of the depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injectable (Depo-Provera) concerning. “It has a pretty hefty dose of a particular type of progestin that significantly suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis – more than other progestin-only methods,” she said. “And we may see some unfavorable lipid changes and changes in carbohydrate metabolism.”

The effects of the DMPA injectable, which is in category 3 for these women, may persist for several months – or longer – after discontinuation, Dr. Burke said. The levonorgestrel IUD, on the other hand, has little effect on diabetes control, hemostatic markers, or lipids; it is in category 2 for these women.

A recently published database analysis found that diabetic users of the DMPA injectable had a hazard ratio for venous thromboembolism of 4.6, compared with IUD users, Dr. Burke said. The study included patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Care 2017;40:233-8).

Combined hormonal contraception is assigned to categories 3 and 4 for women with complicated or long-standing diabetes, in part because of thrombosis risk, which “as we know, is slightly elevated even for healthy women,” Dr. Burke said. “There are still quite a few methods that are safe to use without reservation, so here is where we start to move away from combined hormonal methods.”

In addition to the Medical Eligibility Criteria, the CDC has another document, the U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, also last updated in 2016, which offers “helpful” advice on precontraception tests to perform, timing after pregnancy for starting contraceptive methods, and other issues, Dr. Burke said.

Dr. Burke reported receiving research funding from Bayer, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and Ibis Reproductive Health.

WASHINGTON – Women with a history of gestational diabetes can use any contraceptive method safely, and those with uncomplicated pregestational diabetes can also consider all methods, said Anne Burke, MD, director of the family planning division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.