User login

Evidence-based bundles reduced shoulder dystocia rates

ATLANTA – Implementation of evidence-based practice bundles was associated with significant reductions in shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, and operative vaginal delivery in a large multicenter hospital system.

From the 18 months prior to implementation of the bundles – which included a planned vaginal delivery tool to assess for shoulder dystocia risk – to the 36 months after implementation, the rate of shoulder dystocia decreased from 1.7 to 1.4 per 100 births, Dr. Laura Sienas reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“This is a 17.6% reduction in the rate of shoulder dystocia. There was a statistically significant association with increasing bundle compliance of both bundles with a decrease in shoulder dystocia,” said Dr. Sienas, a 3rd-year resident at the University of California, Davis.

Additionally, the rate of brachial plexus injury decreased significantly from 2.1 to 1.5 per 1,000 births (a 29% reduction), and the rate of operative vaginal deliveries also decreased significantly, from 6.1 to 5.0 per 100 births (an 18% reduction).

At the same time, there was no significant change in the primary and total Cesarean section rates: 16.5 per 100 births and 30.1 per 100 births, respectively, she noted.

Key elements of the evidence-based practice bundles included an admission risk assessment, and a review and timeout prior to operative vaginal delivery. Low-fidelity shoulder dystocia drills were also introduced for nurses and physicians. While the drills improved teamwork and communication, they did not result in decreased brachial plexus injury rates, Dr. Sienas noted.

Future research should consider whether high-fidelity drills would lower the rate of brachial plexus injury, she added.

Data for this study was collected from 29 maternal centers, with size ranging from small and rural with fewer than 200 deliveries each year, to large urban hospitals with about 5,000 annual births. Baseline data included all singleton vertex births over 34 weeks’ gestation – about 169,000 total births. After all participating centers attained 90% compliance with the evidence-based practice bundles, about 103,000 deliveries occurred. Compliance with the bundles was scored as all or none.

The 29 hospitals in the health system where this study took place have average delivery volumes between 150 and 5,000 births per year, suggesting that the current findings would be applicable to nearly all delivery units in the United States, she said.

Dr. Sienas reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Implementation of evidence-based practice bundles was associated with significant reductions in shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, and operative vaginal delivery in a large multicenter hospital system.

From the 18 months prior to implementation of the bundles – which included a planned vaginal delivery tool to assess for shoulder dystocia risk – to the 36 months after implementation, the rate of shoulder dystocia decreased from 1.7 to 1.4 per 100 births, Dr. Laura Sienas reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“This is a 17.6% reduction in the rate of shoulder dystocia. There was a statistically significant association with increasing bundle compliance of both bundles with a decrease in shoulder dystocia,” said Dr. Sienas, a 3rd-year resident at the University of California, Davis.

Additionally, the rate of brachial plexus injury decreased significantly from 2.1 to 1.5 per 1,000 births (a 29% reduction), and the rate of operative vaginal deliveries also decreased significantly, from 6.1 to 5.0 per 100 births (an 18% reduction).

At the same time, there was no significant change in the primary and total Cesarean section rates: 16.5 per 100 births and 30.1 per 100 births, respectively, she noted.

Key elements of the evidence-based practice bundles included an admission risk assessment, and a review and timeout prior to operative vaginal delivery. Low-fidelity shoulder dystocia drills were also introduced for nurses and physicians. While the drills improved teamwork and communication, they did not result in decreased brachial plexus injury rates, Dr. Sienas noted.

Future research should consider whether high-fidelity drills would lower the rate of brachial plexus injury, she added.

Data for this study was collected from 29 maternal centers, with size ranging from small and rural with fewer than 200 deliveries each year, to large urban hospitals with about 5,000 annual births. Baseline data included all singleton vertex births over 34 weeks’ gestation – about 169,000 total births. After all participating centers attained 90% compliance with the evidence-based practice bundles, about 103,000 deliveries occurred. Compliance with the bundles was scored as all or none.

The 29 hospitals in the health system where this study took place have average delivery volumes between 150 and 5,000 births per year, suggesting that the current findings would be applicable to nearly all delivery units in the United States, she said.

Dr. Sienas reported having no financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Implementation of evidence-based practice bundles was associated with significant reductions in shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, and operative vaginal delivery in a large multicenter hospital system.

From the 18 months prior to implementation of the bundles – which included a planned vaginal delivery tool to assess for shoulder dystocia risk – to the 36 months after implementation, the rate of shoulder dystocia decreased from 1.7 to 1.4 per 100 births, Dr. Laura Sienas reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“This is a 17.6% reduction in the rate of shoulder dystocia. There was a statistically significant association with increasing bundle compliance of both bundles with a decrease in shoulder dystocia,” said Dr. Sienas, a 3rd-year resident at the University of California, Davis.

Additionally, the rate of brachial plexus injury decreased significantly from 2.1 to 1.5 per 1,000 births (a 29% reduction), and the rate of operative vaginal deliveries also decreased significantly, from 6.1 to 5.0 per 100 births (an 18% reduction).

At the same time, there was no significant change in the primary and total Cesarean section rates: 16.5 per 100 births and 30.1 per 100 births, respectively, she noted.

Key elements of the evidence-based practice bundles included an admission risk assessment, and a review and timeout prior to operative vaginal delivery. Low-fidelity shoulder dystocia drills were also introduced for nurses and physicians. While the drills improved teamwork and communication, they did not result in decreased brachial plexus injury rates, Dr. Sienas noted.

Future research should consider whether high-fidelity drills would lower the rate of brachial plexus injury, she added.

Data for this study was collected from 29 maternal centers, with size ranging from small and rural with fewer than 200 deliveries each year, to large urban hospitals with about 5,000 annual births. Baseline data included all singleton vertex births over 34 weeks’ gestation – about 169,000 total births. After all participating centers attained 90% compliance with the evidence-based practice bundles, about 103,000 deliveries occurred. Compliance with the bundles was scored as all or none.

The 29 hospitals in the health system where this study took place have average delivery volumes between 150 and 5,000 births per year, suggesting that the current findings would be applicable to nearly all delivery units in the United States, she said.

Dr. Sienas reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Use of evidence-based practice bundles helped reduce rates of shoulder dystocia, brachial plexus injury, and operative vaginal delivery.

Major finding: Shoulder dystocia rates dropped by 17.6% and brachial plexus injuries by 29% with implementation of the bundles.

Data source: A multicenter prospective study of more than 100,000 births.

Disclosures: Dr. Sienas reported having no financial disclosures.

New evidence strengthens link between Zika and microcephaly

While scientists can’t say with certainty that congenital Zika virus is causing the massive spike in cases of microcephaly seen in Brazil, evidence of a strong association continues to mount.

Two reports, published Feb. 10 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in the New England Journal of Medicine, confirm through laboratory testing that fetuses and infants with microcephaly also were positive for Zika virus infection.

In the MMWR report, researchers from the United States and Brazil present evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues with infants with microcephaly, as well as placental tissues from early miscarriages.

The findings are based on laboratory testing of tissue samples from two newborns with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (at 11 and 13 weeks’ gestation). The samples were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in December 2015. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection during the first trimester but did not have signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage.

Specimens from all four cases were positive by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, and sequence analysis provided additional evidence of Zika virus infection (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65:1-2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er).

“To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

In the New England Journal of Medicine report, Dr. Jernej Mlakar of the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and colleagues, presented the case of a previously healthy 25-year-old pregnant woman who had become ill while living in Brazil. During the 13th week of gestation, she had a high fever, followed by severe musculoskeletal and retro-ocular pain, as well as an itchy generalized maculopapular rash. Zika virus was suspected at the time but virologic diagnostic testing was not performed.

Ultrasound at 14 weeks and 20 weeks showed normal fetal growth and anatomy, but ultrasound at 29 weeks showed signs of fetal abnormalities. At 32 weeks, physicians confirmed intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly with calcifications in the fetal brain and placenta.

The woman requested termination of the pregnancy and an autopsy was performed on the fetus. Positive results for Zika virus were obtained on RT-PCR assay in the fetal brain sample. All autopsy samples were tested on PCR assay and found to be negative for other flaviviruses, including dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651).

In an editorial accompanying the report, physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, wrote that there are still many unanswered questions about Zika virus in pregnancy. Assuming the association between Zika virus and microcephaly exists, researchers do not know whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy has an effect on the risk of fetal abnormalities. Additionally, it’s unknown whether asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease poses a risk to the fetus (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1601862).

The researchers for both case reports had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

While scientists can’t say with certainty that congenital Zika virus is causing the massive spike in cases of microcephaly seen in Brazil, evidence of a strong association continues to mount.

Two reports, published Feb. 10 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in the New England Journal of Medicine, confirm through laboratory testing that fetuses and infants with microcephaly also were positive for Zika virus infection.

In the MMWR report, researchers from the United States and Brazil present evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues with infants with microcephaly, as well as placental tissues from early miscarriages.

The findings are based on laboratory testing of tissue samples from two newborns with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (at 11 and 13 weeks’ gestation). The samples were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in December 2015. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection during the first trimester but did not have signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage.

Specimens from all four cases were positive by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, and sequence analysis provided additional evidence of Zika virus infection (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65:1-2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er).

“To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

In the New England Journal of Medicine report, Dr. Jernej Mlakar of the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and colleagues, presented the case of a previously healthy 25-year-old pregnant woman who had become ill while living in Brazil. During the 13th week of gestation, she had a high fever, followed by severe musculoskeletal and retro-ocular pain, as well as an itchy generalized maculopapular rash. Zika virus was suspected at the time but virologic diagnostic testing was not performed.

Ultrasound at 14 weeks and 20 weeks showed normal fetal growth and anatomy, but ultrasound at 29 weeks showed signs of fetal abnormalities. At 32 weeks, physicians confirmed intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly with calcifications in the fetal brain and placenta.

The woman requested termination of the pregnancy and an autopsy was performed on the fetus. Positive results for Zika virus were obtained on RT-PCR assay in the fetal brain sample. All autopsy samples were tested on PCR assay and found to be negative for other flaviviruses, including dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651).

In an editorial accompanying the report, physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, wrote that there are still many unanswered questions about Zika virus in pregnancy. Assuming the association between Zika virus and microcephaly exists, researchers do not know whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy has an effect on the risk of fetal abnormalities. Additionally, it’s unknown whether asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease poses a risk to the fetus (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1601862).

The researchers for both case reports had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

While scientists can’t say with certainty that congenital Zika virus is causing the massive spike in cases of microcephaly seen in Brazil, evidence of a strong association continues to mount.

Two reports, published Feb. 10 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in the New England Journal of Medicine, confirm through laboratory testing that fetuses and infants with microcephaly also were positive for Zika virus infection.

In the MMWR report, researchers from the United States and Brazil present evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues with infants with microcephaly, as well as placental tissues from early miscarriages.

The findings are based on laboratory testing of tissue samples from two newborns with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (at 11 and 13 weeks’ gestation). The samples were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in December 2015. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection during the first trimester but did not have signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage.

Specimens from all four cases were positive by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, and sequence analysis provided additional evidence of Zika virus infection (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65:1-2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er).

“To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

In the New England Journal of Medicine report, Dr. Jernej Mlakar of the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and colleagues, presented the case of a previously healthy 25-year-old pregnant woman who had become ill while living in Brazil. During the 13th week of gestation, she had a high fever, followed by severe musculoskeletal and retro-ocular pain, as well as an itchy generalized maculopapular rash. Zika virus was suspected at the time but virologic diagnostic testing was not performed.

Ultrasound at 14 weeks and 20 weeks showed normal fetal growth and anatomy, but ultrasound at 29 weeks showed signs of fetal abnormalities. At 32 weeks, physicians confirmed intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly with calcifications in the fetal brain and placenta.

The woman requested termination of the pregnancy and an autopsy was performed on the fetus. Positive results for Zika virus were obtained on RT-PCR assay in the fetal brain sample. All autopsy samples were tested on PCR assay and found to be negative for other flaviviruses, including dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651).

In an editorial accompanying the report, physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, wrote that there are still many unanswered questions about Zika virus in pregnancy. Assuming the association between Zika virus and microcephaly exists, researchers do not know whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy has an effect on the risk of fetal abnormalities. Additionally, it’s unknown whether asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease poses a risk to the fetus (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1601862).

The researchers for both case reports had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

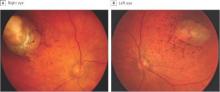

Ocular symptoms accompany microcephaly in Brazilian newborns

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA OPTHALMOLOGY

Key clinical point: Serious ocular abnormalities may accompany microcephaly in babies born to mothers infected with the Zika virus.

Major finding: More than one-third (34.5%) of a cohort of 29 infants born with microcephaly and with a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus had ocular abnormalities in one or both eyes.

Data source: A single-site cohort study evaluating 29 infants born with microcephaly in a single hospital in Salvador, Brazil.

Disclosures: Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

CDC’s emergency operations center moves to Level 1 for Zika

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are ramping up their response to the Zika virus – moving their Emergency Operations Center to Level 1 activation.

The agency’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) was initially activated for Zika response on Jan. 22 to better coordinate the response to the Zika outbreak and bring together CDC scientists in arboviruses, reproductive health, and birth and developmental defects. On Feb. 8, the CDC accelerated its efforts “in anticipation of local Zika virus transmission by mosquitoes in the continental U.S.”

The EOC is currently at work on developing diagnostic tests for Zika virus, investigating links between the virus and microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, conducting surveillance in the United States, and providing on-the-ground support in Puerto Rico, Brazil, and Colombia.

The CDC recently updated its guidance on Zika virus, advising pregnant women to use condoms or abstain from sex with men who have traveled to Zika-infected areas. The agency also advised offering testing to pregnant women without symptoms of Zika virus 2-12 weeks after returning from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission.

The CDC’s current Zika virus travel alert includes American Samoa, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Costa Rica, Curacao, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, Tonga, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Dominican Republic.

An up-to-date list of affected countries and regions is available at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html.

On Twitter @maryelleny

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are ramping up their response to the Zika virus – moving their Emergency Operations Center to Level 1 activation.

The agency’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) was initially activated for Zika response on Jan. 22 to better coordinate the response to the Zika outbreak and bring together CDC scientists in arboviruses, reproductive health, and birth and developmental defects. On Feb. 8, the CDC accelerated its efforts “in anticipation of local Zika virus transmission by mosquitoes in the continental U.S.”

The EOC is currently at work on developing diagnostic tests for Zika virus, investigating links between the virus and microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, conducting surveillance in the United States, and providing on-the-ground support in Puerto Rico, Brazil, and Colombia.

The CDC recently updated its guidance on Zika virus, advising pregnant women to use condoms or abstain from sex with men who have traveled to Zika-infected areas. The agency also advised offering testing to pregnant women without symptoms of Zika virus 2-12 weeks after returning from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission.

The CDC’s current Zika virus travel alert includes American Samoa, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Costa Rica, Curacao, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, Tonga, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Dominican Republic.

An up-to-date list of affected countries and regions is available at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html.

On Twitter @maryelleny

Officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are ramping up their response to the Zika virus – moving their Emergency Operations Center to Level 1 activation.

The agency’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) was initially activated for Zika response on Jan. 22 to better coordinate the response to the Zika outbreak and bring together CDC scientists in arboviruses, reproductive health, and birth and developmental defects. On Feb. 8, the CDC accelerated its efforts “in anticipation of local Zika virus transmission by mosquitoes in the continental U.S.”

The EOC is currently at work on developing diagnostic tests for Zika virus, investigating links between the virus and microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, conducting surveillance in the United States, and providing on-the-ground support in Puerto Rico, Brazil, and Colombia.

The CDC recently updated its guidance on Zika virus, advising pregnant women to use condoms or abstain from sex with men who have traveled to Zika-infected areas. The agency also advised offering testing to pregnant women without symptoms of Zika virus 2-12 weeks after returning from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission.

The CDC’s current Zika virus travel alert includes American Samoa, Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Costa Rica, Curacao, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, Samoa, Suriname, Tonga, Venezuela, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Dominican Republic.

An up-to-date list of affected countries and regions is available at www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/index.html.

On Twitter @maryelleny

VIDEO: SMFM panelist addresses Zika virus testing

ATLANTA – Information about managing pregnant patients who have potential exposure to the Zika virus is evolving rapidly, and in light of new recommendations on sexual transmission of the infection, officials from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine convened an expert panel to address the matter.

Leaders from the society joined officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to discuss the updated guidance – particularly a new recommendation for initially conducting serologic testing in pregnant women who have traveled to endemic areas.

Panel members advised physicians to keep a log of patients with possible Zika virus exposure, so those women can be managed properly in the event of future changes to the guidelines.

In an interview at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, panelist Dr. Brenna Hughes of Brown University, Providence, R.I., stressed the need to work with state health officials to develop local guidelines and testing mechanisms. “It will take a little time to build up the infrastructure for that kind of testing,” she said, adding that it is important to avoid delays.

Dr. Hughes reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ATLANTA – Information about managing pregnant patients who have potential exposure to the Zika virus is evolving rapidly, and in light of new recommendations on sexual transmission of the infection, officials from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine convened an expert panel to address the matter.

Leaders from the society joined officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to discuss the updated guidance – particularly a new recommendation for initially conducting serologic testing in pregnant women who have traveled to endemic areas.

Panel members advised physicians to keep a log of patients with possible Zika virus exposure, so those women can be managed properly in the event of future changes to the guidelines.

In an interview at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, panelist Dr. Brenna Hughes of Brown University, Providence, R.I., stressed the need to work with state health officials to develop local guidelines and testing mechanisms. “It will take a little time to build up the infrastructure for that kind of testing,” she said, adding that it is important to avoid delays.

Dr. Hughes reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ATLANTA – Information about managing pregnant patients who have potential exposure to the Zika virus is evolving rapidly, and in light of new recommendations on sexual transmission of the infection, officials from the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine convened an expert panel to address the matter.

Leaders from the society joined officials from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to discuss the updated guidance – particularly a new recommendation for initially conducting serologic testing in pregnant women who have traveled to endemic areas.

Panel members advised physicians to keep a log of patients with possible Zika virus exposure, so those women can be managed properly in the event of future changes to the guidelines.

In an interview at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, panelist Dr. Brenna Hughes of Brown University, Providence, R.I., stressed the need to work with state health officials to develop local guidelines and testing mechanisms. “It will take a little time to build up the infrastructure for that kind of testing,” she said, adding that it is important to avoid delays.

Dr. Hughes reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

OPPTIMUM Trial: No benefit found for vaginal progesterone in preterm birth prevention

ATLANTA – Vaginal progesterone confers no obstetrical or neonatal benefit, and no long-term benefit with respect to cognitive and neurosensory outcomes in children when used to prevent preterm birth, according to findings from the randomized, controlled, double-blind OPPTIMUM trial.

The findings from OPPTIMUM – the largest trial to date looking at progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth – have important implications for current practice. Vaginal progesterone is not currently approved for the prevention of preterm birth in the United States, but is commonly used off label for this purpose.

Prior studies have demonstrated a benefit with respect to progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, particularly in women with a short cervix, but no studies have looked at long-term outcomes, Dr. Jane E. Norman of the University of Edinburgh reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

In OPPTIMUM, the rate of the primary obstetric outcome of preterm birth or fetal death before 34 weeks’ gestation did not differ significantly for 618 women at risk for preterm birth who were randomized to receive 200 mg of vaginal progesterone daily starting at 22-24 weeks and continuing to 34 weeks’ gestation, compared with 600 women who received placebo (16% vs. 18%; odds ratio, 0.86), Dr. Norman said.

The rate of the primary neonatal composite outcome of death or major morbidity (brain injury or bronchopulmonary dysplasia) also did not differ significantly between the progesterone and placebo groups after a prespecified multiple comparisons procedure (6% vs. 10%; odds ratio, 0.62).

A secondary analysis looking at the individual components of the composite neonatal outcomes showed that progesterone reduced the risk of brain injury and neonatal death, but not bronchopulmonary dysplasia, she said.

Further, no difference was seen in Bayley III cognitive scores (with values imputed for deaths) at 2 years of age in 439 and 430 children born to mothers in the progesterone and placebo groups, respectively (average scores, 97.7 and 97.3; odds ratio, 0.48).

On secondary analyses, some safety signals were noted with respect to neurodevelopmental outcomes.

“We were really surprised that we didn’t show that progesterone prevented preterm birth, and we became concerned that perhaps our cutoff of 34 weeks was just the wrong time to choose a cutoff,” Dr. Norman said, noting that a post hoc survival curve analysis was performed to look at the trajectory to delivery, and a “very marginal benefit” was seen with progesterone, but the difference was not statistically significant.

In addition, subgroup analyses showed no significant benefit of progesterone on obstetrical, neonatal, or childhood outcomes. For example, in women with a short cervix, no evidence was seen that progesterone was more or less effective than in women with a longer cervix. Other subgroups studied included fibronectin-positive and fibronectin-negative women and women with a history of preterm birth. Progesterone was no more or less effective in any of the subgroups, Dr. Norman said.

OPPTIMUM study subjects were women at risk of preterm birth because of a positive fetal fibronectin test result, a history of spontaneous preterm birth at or before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a short cervix (25 mm or less).

All outcomes were adjusted for a previous pregnancy of 14 weeks’ gestation or greater, with study center as a random effect.

“OPPTIMUM is the largest trial of progesterone to prevent preterm birth, and after adjusting for multiple comparisons as we planned, we did not disprove the null hypothesis that progesterone doesn’t prevent preterm birth, it doesn’t reduce adverse neonatal outcomes, and it doesn’t have a beneficial effect on childhood outcomes,” Dr. Norman said, concluding that “there is a remaining unmet need for a safe and effective agent to prevent preterm birth.”

Asked about the safety of progesterone given the findings from secondary analyses in OPPTIMUM, she said, “I would not advise my daughter to take progesterone if she’s pregnant.”

The study drug and placebo were donated by Besins, but the company was not involved in study design or analysis. Funding was provided by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Norman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Vaginal progesterone confers no obstetrical or neonatal benefit, and no long-term benefit with respect to cognitive and neurosensory outcomes in children when used to prevent preterm birth, according to findings from the randomized, controlled, double-blind OPPTIMUM trial.

The findings from OPPTIMUM – the largest trial to date looking at progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth – have important implications for current practice. Vaginal progesterone is not currently approved for the prevention of preterm birth in the United States, but is commonly used off label for this purpose.

Prior studies have demonstrated a benefit with respect to progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, particularly in women with a short cervix, but no studies have looked at long-term outcomes, Dr. Jane E. Norman of the University of Edinburgh reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

In OPPTIMUM, the rate of the primary obstetric outcome of preterm birth or fetal death before 34 weeks’ gestation did not differ significantly for 618 women at risk for preterm birth who were randomized to receive 200 mg of vaginal progesterone daily starting at 22-24 weeks and continuing to 34 weeks’ gestation, compared with 600 women who received placebo (16% vs. 18%; odds ratio, 0.86), Dr. Norman said.

The rate of the primary neonatal composite outcome of death or major morbidity (brain injury or bronchopulmonary dysplasia) also did not differ significantly between the progesterone and placebo groups after a prespecified multiple comparisons procedure (6% vs. 10%; odds ratio, 0.62).

A secondary analysis looking at the individual components of the composite neonatal outcomes showed that progesterone reduced the risk of brain injury and neonatal death, but not bronchopulmonary dysplasia, she said.

Further, no difference was seen in Bayley III cognitive scores (with values imputed for deaths) at 2 years of age in 439 and 430 children born to mothers in the progesterone and placebo groups, respectively (average scores, 97.7 and 97.3; odds ratio, 0.48).

On secondary analyses, some safety signals were noted with respect to neurodevelopmental outcomes.

“We were really surprised that we didn’t show that progesterone prevented preterm birth, and we became concerned that perhaps our cutoff of 34 weeks was just the wrong time to choose a cutoff,” Dr. Norman said, noting that a post hoc survival curve analysis was performed to look at the trajectory to delivery, and a “very marginal benefit” was seen with progesterone, but the difference was not statistically significant.

In addition, subgroup analyses showed no significant benefit of progesterone on obstetrical, neonatal, or childhood outcomes. For example, in women with a short cervix, no evidence was seen that progesterone was more or less effective than in women with a longer cervix. Other subgroups studied included fibronectin-positive and fibronectin-negative women and women with a history of preterm birth. Progesterone was no more or less effective in any of the subgroups, Dr. Norman said.

OPPTIMUM study subjects were women at risk of preterm birth because of a positive fetal fibronectin test result, a history of spontaneous preterm birth at or before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a short cervix (25 mm or less).

All outcomes were adjusted for a previous pregnancy of 14 weeks’ gestation or greater, with study center as a random effect.

“OPPTIMUM is the largest trial of progesterone to prevent preterm birth, and after adjusting for multiple comparisons as we planned, we did not disprove the null hypothesis that progesterone doesn’t prevent preterm birth, it doesn’t reduce adverse neonatal outcomes, and it doesn’t have a beneficial effect on childhood outcomes,” Dr. Norman said, concluding that “there is a remaining unmet need for a safe and effective agent to prevent preterm birth.”

Asked about the safety of progesterone given the findings from secondary analyses in OPPTIMUM, she said, “I would not advise my daughter to take progesterone if she’s pregnant.”

The study drug and placebo were donated by Besins, but the company was not involved in study design or analysis. Funding was provided by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Norman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Vaginal progesterone confers no obstetrical or neonatal benefit, and no long-term benefit with respect to cognitive and neurosensory outcomes in children when used to prevent preterm birth, according to findings from the randomized, controlled, double-blind OPPTIMUM trial.

The findings from OPPTIMUM – the largest trial to date looking at progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth – have important implications for current practice. Vaginal progesterone is not currently approved for the prevention of preterm birth in the United States, but is commonly used off label for this purpose.

Prior studies have demonstrated a benefit with respect to progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, particularly in women with a short cervix, but no studies have looked at long-term outcomes, Dr. Jane E. Norman of the University of Edinburgh reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

In OPPTIMUM, the rate of the primary obstetric outcome of preterm birth or fetal death before 34 weeks’ gestation did not differ significantly for 618 women at risk for preterm birth who were randomized to receive 200 mg of vaginal progesterone daily starting at 22-24 weeks and continuing to 34 weeks’ gestation, compared with 600 women who received placebo (16% vs. 18%; odds ratio, 0.86), Dr. Norman said.

The rate of the primary neonatal composite outcome of death or major morbidity (brain injury or bronchopulmonary dysplasia) also did not differ significantly between the progesterone and placebo groups after a prespecified multiple comparisons procedure (6% vs. 10%; odds ratio, 0.62).

A secondary analysis looking at the individual components of the composite neonatal outcomes showed that progesterone reduced the risk of brain injury and neonatal death, but not bronchopulmonary dysplasia, she said.

Further, no difference was seen in Bayley III cognitive scores (with values imputed for deaths) at 2 years of age in 439 and 430 children born to mothers in the progesterone and placebo groups, respectively (average scores, 97.7 and 97.3; odds ratio, 0.48).

On secondary analyses, some safety signals were noted with respect to neurodevelopmental outcomes.

“We were really surprised that we didn’t show that progesterone prevented preterm birth, and we became concerned that perhaps our cutoff of 34 weeks was just the wrong time to choose a cutoff,” Dr. Norman said, noting that a post hoc survival curve analysis was performed to look at the trajectory to delivery, and a “very marginal benefit” was seen with progesterone, but the difference was not statistically significant.

In addition, subgroup analyses showed no significant benefit of progesterone on obstetrical, neonatal, or childhood outcomes. For example, in women with a short cervix, no evidence was seen that progesterone was more or less effective than in women with a longer cervix. Other subgroups studied included fibronectin-positive and fibronectin-negative women and women with a history of preterm birth. Progesterone was no more or less effective in any of the subgroups, Dr. Norman said.

OPPTIMUM study subjects were women at risk of preterm birth because of a positive fetal fibronectin test result, a history of spontaneous preterm birth at or before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a short cervix (25 mm or less).

All outcomes were adjusted for a previous pregnancy of 14 weeks’ gestation or greater, with study center as a random effect.

“OPPTIMUM is the largest trial of progesterone to prevent preterm birth, and after adjusting for multiple comparisons as we planned, we did not disprove the null hypothesis that progesterone doesn’t prevent preterm birth, it doesn’t reduce adverse neonatal outcomes, and it doesn’t have a beneficial effect on childhood outcomes,” Dr. Norman said, concluding that “there is a remaining unmet need for a safe and effective agent to prevent preterm birth.”

Asked about the safety of progesterone given the findings from secondary analyses in OPPTIMUM, she said, “I would not advise my daughter to take progesterone if she’s pregnant.”

The study drug and placebo were donated by Besins, but the company was not involved in study design or analysis. Funding was provided by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Norman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Vaginal progesterone had no obstetrical or neonatal benefit when used to prevent preterm birth.

Major finding: The rate of preterm birth or fetal death before 34 weeks’ gestation did not differ significantly in women treated with vaginal progesterone and those who received placebo (16% vs. 18%; odds ratio, 0.86).

Data source: The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter OPPTIMUM trial.

Disclosures: The study drug and placebo were donated by Besins, but the company was not involved in study design or analysis. Funding was provided by the Medical Research Council. Dr. Norman reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NIH announces Zika virus research priorities

The National Institutes of Health seeks applications for research on the Zika virus in reproduction, pregnancy, and the developing fetus and announced priorities for that research in a statement issued on Feb. 5.

“One of the highest priorities is to establish conclusively what role, if any, Zika virus has played in the marked increase in suspected microcephaly cases,” NIH officials said, noting that over 4,000 case of microcephaly have been reported in newborns in Brazil since October 2015. “It is possible that these microcephaly cases could have another cause, or that a contributing factor in addition to Zika virus – another virus, for example – could be leading to the condition.”Learning more about sexual transmission of the virus is also a priority. NIH is soliciting studies to determine if the virus is present in semen or vaginal secretions. Other studies “of interest” include whether infection with the virus – currently circulating in about 30 countries and territories – affects long-term fertility in both men and women and increases risk in subsequent pregnancies.

Current research can be modified, the statement points out, and may include modifying ongoing studies of pregnant women and infants to check tissue samples for the virus and evaluate the effects of exposure.

The full statement is available on the NIH website.

The National Institutes of Health seeks applications for research on the Zika virus in reproduction, pregnancy, and the developing fetus and announced priorities for that research in a statement issued on Feb. 5.

“One of the highest priorities is to establish conclusively what role, if any, Zika virus has played in the marked increase in suspected microcephaly cases,” NIH officials said, noting that over 4,000 case of microcephaly have been reported in newborns in Brazil since October 2015. “It is possible that these microcephaly cases could have another cause, or that a contributing factor in addition to Zika virus – another virus, for example – could be leading to the condition.”Learning more about sexual transmission of the virus is also a priority. NIH is soliciting studies to determine if the virus is present in semen or vaginal secretions. Other studies “of interest” include whether infection with the virus – currently circulating in about 30 countries and territories – affects long-term fertility in both men and women and increases risk in subsequent pregnancies.

Current research can be modified, the statement points out, and may include modifying ongoing studies of pregnant women and infants to check tissue samples for the virus and evaluate the effects of exposure.

The full statement is available on the NIH website.

The National Institutes of Health seeks applications for research on the Zika virus in reproduction, pregnancy, and the developing fetus and announced priorities for that research in a statement issued on Feb. 5.

“One of the highest priorities is to establish conclusively what role, if any, Zika virus has played in the marked increase in suspected microcephaly cases,” NIH officials said, noting that over 4,000 case of microcephaly have been reported in newborns in Brazil since October 2015. “It is possible that these microcephaly cases could have another cause, or that a contributing factor in addition to Zika virus – another virus, for example – could be leading to the condition.”Learning more about sexual transmission of the virus is also a priority. NIH is soliciting studies to determine if the virus is present in semen or vaginal secretions. Other studies “of interest” include whether infection with the virus – currently circulating in about 30 countries and territories – affects long-term fertility in both men and women and increases risk in subsequent pregnancies.

Current research can be modified, the statement points out, and may include modifying ongoing studies of pregnant women and infants to check tissue samples for the virus and evaluate the effects of exposure.

The full statement is available on the NIH website.

Congo Red Dot Point-of-care Test Detects Preeclampsia

ATLANTA – A novel, noninvasive, “red dye on paper” diagnostic test allows for rapid screening and identification of preeclampsia at the point of care, according to findings from a prospective clinical study.

Of 343 women enrolled consecutively from a labor and delivery triage unit, 112 had a clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. The diagnostic test – the Congo Red Dot (CRD) paper test – had an 86% rate of accuracy for detecting preeclampsia, which was superior to several other biochemical tests that were also evaluated, Dr. Kara Rood reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Among the comparator tests, which were conducted using stored urine samples to strengthen the final diagnosis, were the laboratory “gold standard” CRD nitrocellulose test, as well as Protein/Creatinine ratio, and urine and serum placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, and urine sFlt-1/PlGF (uFP) ratio. Accuracy rates ranged from 60% to 83%, said Dr. Rood, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

The CRD point-of-care test was developed by researchers at Ohio State and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, also in Columbus, in an effort to reduce morbidity among expecting mothers and their unborn children. The current study is the first to test the affordable tool, and the findings promise to have an important impact on the health of women and children, she said.

Study subjects were consecutive women evaluated for preeclampsia at Wexner Medical Center. The CRD test was performed using 0.45 cc of fresh crude urine, and results were scored by trained clinical nurses at the bedside.

The average latency period between a positive paper-based CRD test and delivery was 14 days, which was significantly shorter than the interval for those who tested negative, Dr. Rood said.

The CRD test was developed based on previous findings by Dr. Irina A. Buhimschi of the Center for Perinatal Research in the the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and her colleagues, who discovered that preeclampsia may result from a collection of misfolded proteins that are identifiable in the urine of pregnant women. Congo Red is a dye used by pathologists to identify amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and it was found to bind and incorporate into the abnormally folded proteins in the urine of pregnant women with preeclampsia. The initial CRD test for preeclampsia had an 89% accuracy rate, according to preliminary findings published in 2014.

“This new point-of-care test is a more user-friendly version than the one in the [2014] publication, and can help identify preeclampsia even before clinical symptoms appear,” Dr. Buhimschi said in a press statement, which also noted that the research team is “currently investigating how each misfolded protein collection affects pregnant women. The answer might assist with developing an effective treatment or even preventing preeclampsia.”

Dr. Rood disclosed that concepts outlined during her presentation are the subject of patents and patent applications filed by Yale University and licensed to private entities for development and commercialization. Some of the study authors are named as inventors of the Congo Red Dot test.

ATLANTA – A novel, noninvasive, “red dye on paper” diagnostic test allows for rapid screening and identification of preeclampsia at the point of care, according to findings from a prospective clinical study.

Of 343 women enrolled consecutively from a labor and delivery triage unit, 112 had a clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. The diagnostic test – the Congo Red Dot (CRD) paper test – had an 86% rate of accuracy for detecting preeclampsia, which was superior to several other biochemical tests that were also evaluated, Dr. Kara Rood reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Among the comparator tests, which were conducted using stored urine samples to strengthen the final diagnosis, were the laboratory “gold standard” CRD nitrocellulose test, as well as Protein/Creatinine ratio, and urine and serum placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, and urine sFlt-1/PlGF (uFP) ratio. Accuracy rates ranged from 60% to 83%, said Dr. Rood, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

The CRD point-of-care test was developed by researchers at Ohio State and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, also in Columbus, in an effort to reduce morbidity among expecting mothers and their unborn children. The current study is the first to test the affordable tool, and the findings promise to have an important impact on the health of women and children, she said.

Study subjects were consecutive women evaluated for preeclampsia at Wexner Medical Center. The CRD test was performed using 0.45 cc of fresh crude urine, and results were scored by trained clinical nurses at the bedside.

The average latency period between a positive paper-based CRD test and delivery was 14 days, which was significantly shorter than the interval for those who tested negative, Dr. Rood said.

The CRD test was developed based on previous findings by Dr. Irina A. Buhimschi of the Center for Perinatal Research in the the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and her colleagues, who discovered that preeclampsia may result from a collection of misfolded proteins that are identifiable in the urine of pregnant women. Congo Red is a dye used by pathologists to identify amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and it was found to bind and incorporate into the abnormally folded proteins in the urine of pregnant women with preeclampsia. The initial CRD test for preeclampsia had an 89% accuracy rate, according to preliminary findings published in 2014.

“This new point-of-care test is a more user-friendly version than the one in the [2014] publication, and can help identify preeclampsia even before clinical symptoms appear,” Dr. Buhimschi said in a press statement, which also noted that the research team is “currently investigating how each misfolded protein collection affects pregnant women. The answer might assist with developing an effective treatment or even preventing preeclampsia.”

Dr. Rood disclosed that concepts outlined during her presentation are the subject of patents and patent applications filed by Yale University and licensed to private entities for development and commercialization. Some of the study authors are named as inventors of the Congo Red Dot test.

ATLANTA – A novel, noninvasive, “red dye on paper” diagnostic test allows for rapid screening and identification of preeclampsia at the point of care, according to findings from a prospective clinical study.

Of 343 women enrolled consecutively from a labor and delivery triage unit, 112 had a clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. The diagnostic test – the Congo Red Dot (CRD) paper test – had an 86% rate of accuracy for detecting preeclampsia, which was superior to several other biochemical tests that were also evaluated, Dr. Kara Rood reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Among the comparator tests, which were conducted using stored urine samples to strengthen the final diagnosis, were the laboratory “gold standard” CRD nitrocellulose test, as well as Protein/Creatinine ratio, and urine and serum placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, and urine sFlt-1/PlGF (uFP) ratio. Accuracy rates ranged from 60% to 83%, said Dr. Rood, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

The CRD point-of-care test was developed by researchers at Ohio State and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, also in Columbus, in an effort to reduce morbidity among expecting mothers and their unborn children. The current study is the first to test the affordable tool, and the findings promise to have an important impact on the health of women and children, she said.

Study subjects were consecutive women evaluated for preeclampsia at Wexner Medical Center. The CRD test was performed using 0.45 cc of fresh crude urine, and results were scored by trained clinical nurses at the bedside.

The average latency period between a positive paper-based CRD test and delivery was 14 days, which was significantly shorter than the interval for those who tested negative, Dr. Rood said.

The CRD test was developed based on previous findings by Dr. Irina A. Buhimschi of the Center for Perinatal Research in the the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and her colleagues, who discovered that preeclampsia may result from a collection of misfolded proteins that are identifiable in the urine of pregnant women. Congo Red is a dye used by pathologists to identify amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and it was found to bind and incorporate into the abnormally folded proteins in the urine of pregnant women with preeclampsia. The initial CRD test for preeclampsia had an 89% accuracy rate, according to preliminary findings published in 2014.

“This new point-of-care test is a more user-friendly version than the one in the [2014] publication, and can help identify preeclampsia even before clinical symptoms appear,” Dr. Buhimschi said in a press statement, which also noted that the research team is “currently investigating how each misfolded protein collection affects pregnant women. The answer might assist with developing an effective treatment or even preventing preeclampsia.”

Dr. Rood disclosed that concepts outlined during her presentation are the subject of patents and patent applications filed by Yale University and licensed to private entities for development and commercialization. Some of the study authors are named as inventors of the Congo Red Dot test.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Congo Red Dot point-of-care test detects preeclampsia

ATLANTA – A novel, noninvasive, “red dye on paper” diagnostic test allows for rapid screening and identification of preeclampsia at the point of care, according to findings from a prospective clinical study.

Of 343 women enrolled consecutively from a labor and delivery triage unit, 112 had a clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. The diagnostic test – the Congo Red Dot (CRD) paper test – had an 86% rate of accuracy for detecting preeclampsia, which was superior to several other biochemical tests that were also evaluated, Dr. Kara Rood reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Among the comparator tests, which were conducted using stored urine samples to strengthen the final diagnosis, were the laboratory “gold standard” CRD nitrocellulose test, as well as Protein/Creatinine ratio, and urine and serum placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, and urine sFlt-1/PlGF (uFP) ratio. Accuracy rates ranged from 60% to 83%, said Dr. Rood, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

The CRD point-of-care test was developed by researchers at Ohio State and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, also in Columbus, in an effort to reduce morbidity among expecting mothers and their unborn children. The current study is the first to test the affordable tool, and the findings promise to have an important impact on the health of women and children, she said.

Study subjects were consecutive women evaluated for preeclampsia at Wexner Medical Center. The CRD test was performed using 0.45 cc of fresh crude urine, and results were scored by trained clinical nurses at the bedside.

The average latency period between a positive paper-based CRD test and delivery was 14 days, which was significantly shorter than the interval for those who tested negative, Dr. Rood said.

The CRD test was developed based on previous findings by Dr. Irina A. Buhimschi of the Center for Perinatal Research in the the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and her colleagues, who discovered that preeclampsia may result from a collection of misfolded proteins that are identifiable in the urine of pregnant women. Congo Red is a dye used by pathologists to identify amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and it was found to bind and incorporate into the abnormally folded proteins in the urine of pregnant women with preeclampsia. The initial CRD test for preeclampsia had an 89% accuracy rate, according to preliminary findings published in 2014.

“This new point-of-care test is a more user-friendly version than the one in the [2014] publication, and can help identify preeclampsia even before clinical symptoms appear,” Dr. Buhimschi said in a press statement, which also noted that the research team is “currently investigating how each misfolded protein collection affects pregnant women. The answer might assist with developing an effective treatment or even preventing preeclampsia.”

Dr. Rood disclosed that concepts outlined during her presentation are the subject of patents and patent applications filed by Yale University and licensed to private entities for development and commercialization. Some of the study authors are named as inventors of the Congo Red Dot test.

ATLANTA – A novel, noninvasive, “red dye on paper” diagnostic test allows for rapid screening and identification of preeclampsia at the point of care, according to findings from a prospective clinical study.

Of 343 women enrolled consecutively from a labor and delivery triage unit, 112 had a clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. The diagnostic test – the Congo Red Dot (CRD) paper test – had an 86% rate of accuracy for detecting preeclampsia, which was superior to several other biochemical tests that were also evaluated, Dr. Kara Rood reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Among the comparator tests, which were conducted using stored urine samples to strengthen the final diagnosis, were the laboratory “gold standard” CRD nitrocellulose test, as well as Protein/Creatinine ratio, and urine and serum placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, and urine sFlt-1/PlGF (uFP) ratio. Accuracy rates ranged from 60% to 83%, said Dr. Rood, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

The CRD point-of-care test was developed by researchers at Ohio State and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, also in Columbus, in an effort to reduce morbidity among expecting mothers and their unborn children. The current study is the first to test the affordable tool, and the findings promise to have an important impact on the health of women and children, she said.

Study subjects were consecutive women evaluated for preeclampsia at Wexner Medical Center. The CRD test was performed using 0.45 cc of fresh crude urine, and results were scored by trained clinical nurses at the bedside.

The average latency period between a positive paper-based CRD test and delivery was 14 days, which was significantly shorter than the interval for those who tested negative, Dr. Rood said.

The CRD test was developed based on previous findings by Dr. Irina A. Buhimschi of the Center for Perinatal Research in the the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and her colleagues, who discovered that preeclampsia may result from a collection of misfolded proteins that are identifiable in the urine of pregnant women. Congo Red is a dye used by pathologists to identify amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and it was found to bind and incorporate into the abnormally folded proteins in the urine of pregnant women with preeclampsia. The initial CRD test for preeclampsia had an 89% accuracy rate, according to preliminary findings published in 2014.

“This new point-of-care test is a more user-friendly version than the one in the [2014] publication, and can help identify preeclampsia even before clinical symptoms appear,” Dr. Buhimschi said in a press statement, which also noted that the research team is “currently investigating how each misfolded protein collection affects pregnant women. The answer might assist with developing an effective treatment or even preventing preeclampsia.”

Dr. Rood disclosed that concepts outlined during her presentation are the subject of patents and patent applications filed by Yale University and licensed to private entities for development and commercialization. Some of the study authors are named as inventors of the Congo Red Dot test.

ATLANTA – A novel, noninvasive, “red dye on paper” diagnostic test allows for rapid screening and identification of preeclampsia at the point of care, according to findings from a prospective clinical study.

Of 343 women enrolled consecutively from a labor and delivery triage unit, 112 had a clinical diagnosis of preeclampsia. The diagnostic test – the Congo Red Dot (CRD) paper test – had an 86% rate of accuracy for detecting preeclampsia, which was superior to several other biochemical tests that were also evaluated, Dr. Kara Rood reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Among the comparator tests, which were conducted using stored urine samples to strengthen the final diagnosis, were the laboratory “gold standard” CRD nitrocellulose test, as well as Protein/Creatinine ratio, and urine and serum placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, and urine sFlt-1/PlGF (uFP) ratio. Accuracy rates ranged from 60% to 83%, said Dr. Rood, a maternal-fetal medicine fellow at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus.

The CRD point-of-care test was developed by researchers at Ohio State and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, also in Columbus, in an effort to reduce morbidity among expecting mothers and their unborn children. The current study is the first to test the affordable tool, and the findings promise to have an important impact on the health of women and children, she said.

Study subjects were consecutive women evaluated for preeclampsia at Wexner Medical Center. The CRD test was performed using 0.45 cc of fresh crude urine, and results were scored by trained clinical nurses at the bedside.

The average latency period between a positive paper-based CRD test and delivery was 14 days, which was significantly shorter than the interval for those who tested negative, Dr. Rood said.

The CRD test was developed based on previous findings by Dr. Irina A. Buhimschi of the Center for Perinatal Research in the the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and her colleagues, who discovered that preeclampsia may result from a collection of misfolded proteins that are identifiable in the urine of pregnant women. Congo Red is a dye used by pathologists to identify amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and it was found to bind and incorporate into the abnormally folded proteins in the urine of pregnant women with preeclampsia. The initial CRD test for preeclampsia had an 89% accuracy rate, according to preliminary findings published in 2014.