User login

Chlorhexidine beats iodine for preventing C-section wound infections

ATLANTA – A chlorhexidine/alcohol skin antiseptic cut cesarean section surgical site infections by half, compared with a solution of iodine and alcohol.

The chlorhexidine solution significantly reduced the risk of both superficial and deep incisional infections, Dr. Methodius G. Tuuli reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016 Feb 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511048).

The randomized trial is the first to examine the two antiseptics in obstetric surgery, noted Dr. Tuuli of Washington University, St. Louis. The results echo those repeatedly found in the general surgical literature, and, he said, clearly show that chlorhexidine-based skin prep is more effective than the more often–employed iodine-based prep.

“We become comfortable doing the things we have always done, because that’s the way we were taught, and we see no reason to change,” he said in an interview. “I think now is the time to make a change for our patients.”

Dr. Tuuli’s study comprised 1,147 patients who delivered via cesarean section from 2011-2015. They were randomized to either a chlorhexidine/alcohol antiseptic (2% chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% isopropyl alcohol) or the iodine/alcohol combination (8.3% povidone-iodine with 72.5% isopropyl alcohol). Both groups received standard-of-care systemic antibiotic prophylaxis.

They were followed daily until discharge from the hospital, and then with a telephone call 30 days after delivery to assess whether a surgical site infection had occurred, as well as any visits to a physician’s office or emergency department that were related to a wound complication.

The co-primary endpoints were superficial and deep incisional infections. Secondary endpoints included length of hospital stay; physician office visits; hospital readmissions for infection-related complications; endometritis; positive wound culture; skin irritation; and allergic reaction.

Surgical site infections occurred in 23 patients in the chlorhexidine group and 42 in the iodine group (4.0% vs. 7.3%) – a significant 45% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.55). Superficial infections were significantly less common in the chlorhexidine group (3.0% vs. 4.9%), as were deep infections (1.0% vs. 2.4%).

A subgroup analysis examined unscheduled vs. scheduled cesarean; obese vs. nonobese patients; suture vs. staple closure; diabetes vs. no diabetes; and chronic comorbidities vs. none. Chlorhexidine was significantly more effective than iodine in each of these groups.

Antiseptic type did not affect rates of skin separation, seroma, hematoma, or cellulitis. Nor did it affect the rates of endometritis, hospitalization for infectious complications, or length of hospital stay. However, those in the chlorhexidine group were significantly less likely to visit a physician for wound care (7.9% vs. 12.5%)

Cultures were obtained on 32 patients with a confirmed infection; 27 of these specimens were positive. About half of the positive cultures were polymicrobial. The most common isolate was Staphylococcus aureus (37%). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was present in 12% of cultures in the chlorhexidine group and 17% in the iodine group.

In an interview, Dr. Tuuli said that chlorhexidine has several properties that make it more effective than iodine. It is effective against both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including MRSA, and is not inactivated by organic matter. Although chlorhexidine is more likely than iodine to provoke an allergic reaction, none were observed in this study.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tuuli reported having no financial disclosures; the antiseptics were procured and paid for by the medical center.

Watch Dr. Tuuli discuss the study results here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ATLANTA – A chlorhexidine/alcohol skin antiseptic cut cesarean section surgical site infections by half, compared with a solution of iodine and alcohol.

The chlorhexidine solution significantly reduced the risk of both superficial and deep incisional infections, Dr. Methodius G. Tuuli reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016 Feb 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511048).

The randomized trial is the first to examine the two antiseptics in obstetric surgery, noted Dr. Tuuli of Washington University, St. Louis. The results echo those repeatedly found in the general surgical literature, and, he said, clearly show that chlorhexidine-based skin prep is more effective than the more often–employed iodine-based prep.

“We become comfortable doing the things we have always done, because that’s the way we were taught, and we see no reason to change,” he said in an interview. “I think now is the time to make a change for our patients.”

Dr. Tuuli’s study comprised 1,147 patients who delivered via cesarean section from 2011-2015. They were randomized to either a chlorhexidine/alcohol antiseptic (2% chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% isopropyl alcohol) or the iodine/alcohol combination (8.3% povidone-iodine with 72.5% isopropyl alcohol). Both groups received standard-of-care systemic antibiotic prophylaxis.

They were followed daily until discharge from the hospital, and then with a telephone call 30 days after delivery to assess whether a surgical site infection had occurred, as well as any visits to a physician’s office or emergency department that were related to a wound complication.

The co-primary endpoints were superficial and deep incisional infections. Secondary endpoints included length of hospital stay; physician office visits; hospital readmissions for infection-related complications; endometritis; positive wound culture; skin irritation; and allergic reaction.

Surgical site infections occurred in 23 patients in the chlorhexidine group and 42 in the iodine group (4.0% vs. 7.3%) – a significant 45% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.55). Superficial infections were significantly less common in the chlorhexidine group (3.0% vs. 4.9%), as were deep infections (1.0% vs. 2.4%).

A subgroup analysis examined unscheduled vs. scheduled cesarean; obese vs. nonobese patients; suture vs. staple closure; diabetes vs. no diabetes; and chronic comorbidities vs. none. Chlorhexidine was significantly more effective than iodine in each of these groups.

Antiseptic type did not affect rates of skin separation, seroma, hematoma, or cellulitis. Nor did it affect the rates of endometritis, hospitalization for infectious complications, or length of hospital stay. However, those in the chlorhexidine group were significantly less likely to visit a physician for wound care (7.9% vs. 12.5%)

Cultures were obtained on 32 patients with a confirmed infection; 27 of these specimens were positive. About half of the positive cultures were polymicrobial. The most common isolate was Staphylococcus aureus (37%). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was present in 12% of cultures in the chlorhexidine group and 17% in the iodine group.

In an interview, Dr. Tuuli said that chlorhexidine has several properties that make it more effective than iodine. It is effective against both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including MRSA, and is not inactivated by organic matter. Although chlorhexidine is more likely than iodine to provoke an allergic reaction, none were observed in this study.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tuuli reported having no financial disclosures; the antiseptics were procured and paid for by the medical center.

Watch Dr. Tuuli discuss the study results here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ATLANTA – A chlorhexidine/alcohol skin antiseptic cut cesarean section surgical site infections by half, compared with a solution of iodine and alcohol.

The chlorhexidine solution significantly reduced the risk of both superficial and deep incisional infections, Dr. Methodius G. Tuuli reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016 Feb 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511048).

The randomized trial is the first to examine the two antiseptics in obstetric surgery, noted Dr. Tuuli of Washington University, St. Louis. The results echo those repeatedly found in the general surgical literature, and, he said, clearly show that chlorhexidine-based skin prep is more effective than the more often–employed iodine-based prep.

“We become comfortable doing the things we have always done, because that’s the way we were taught, and we see no reason to change,” he said in an interview. “I think now is the time to make a change for our patients.”

Dr. Tuuli’s study comprised 1,147 patients who delivered via cesarean section from 2011-2015. They were randomized to either a chlorhexidine/alcohol antiseptic (2% chlorhexidine gluconate with 70% isopropyl alcohol) or the iodine/alcohol combination (8.3% povidone-iodine with 72.5% isopropyl alcohol). Both groups received standard-of-care systemic antibiotic prophylaxis.

They were followed daily until discharge from the hospital, and then with a telephone call 30 days after delivery to assess whether a surgical site infection had occurred, as well as any visits to a physician’s office or emergency department that were related to a wound complication.

The co-primary endpoints were superficial and deep incisional infections. Secondary endpoints included length of hospital stay; physician office visits; hospital readmissions for infection-related complications; endometritis; positive wound culture; skin irritation; and allergic reaction.

Surgical site infections occurred in 23 patients in the chlorhexidine group and 42 in the iodine group (4.0% vs. 7.3%) – a significant 45% risk reduction (relative risk, 0.55). Superficial infections were significantly less common in the chlorhexidine group (3.0% vs. 4.9%), as were deep infections (1.0% vs. 2.4%).

A subgroup analysis examined unscheduled vs. scheduled cesarean; obese vs. nonobese patients; suture vs. staple closure; diabetes vs. no diabetes; and chronic comorbidities vs. none. Chlorhexidine was significantly more effective than iodine in each of these groups.

Antiseptic type did not affect rates of skin separation, seroma, hematoma, or cellulitis. Nor did it affect the rates of endometritis, hospitalization for infectious complications, or length of hospital stay. However, those in the chlorhexidine group were significantly less likely to visit a physician for wound care (7.9% vs. 12.5%)

Cultures were obtained on 32 patients with a confirmed infection; 27 of these specimens were positive. About half of the positive cultures were polymicrobial. The most common isolate was Staphylococcus aureus (37%). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was present in 12% of cultures in the chlorhexidine group and 17% in the iodine group.

In an interview, Dr. Tuuli said that chlorhexidine has several properties that make it more effective than iodine. It is effective against both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including MRSA, and is not inactivated by organic matter. Although chlorhexidine is more likely than iodine to provoke an allergic reaction, none were observed in this study.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tuuli reported having no financial disclosures; the antiseptics were procured and paid for by the medical center.

Watch Dr. Tuuli discuss the study results here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: A chlorhexidine/alcohol antiseptic was significantly more effective at preventing cesarean section incision infections than an iodine/alcohol antiseptic.

Major finding: The chlorhexidine solution decreased surgical site infections by half, compared with the iodine-based solution.

Data source: A randomized study of 1,147 women who delivered via cesarean from 2011-2015.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tuuli reported having no financial disclosures; the antiseptics were procured and paid for by the medical center.

Betamethasone improves respiratory outcomes in late preterm birth

ATLANTA – Administration of betamethasone to mothers at risk of late preterm birth reduced the risk of perinatal respiratory complications – including supplemental oxygen, ventilation, and death – by 20%.

The steroid was also associated with a 33% reduction in the risk of severe respiratory complications, Dr. Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516783.).

“This finding is practice changing and it’s ready for prime time,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said in an interview. “Right now there are 300,000 late preterm deliveries every year in this country, and if we can do something now to improve their outcomes without imparting any harm, then I think we should do that right away.”

Although standard practice for early preterm infants, betamethasone use in the late preterm period has not been well studied since the 1970s, said Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman of Columbia University, New York. At that time, it was determined to be unhelpful; since then, studies have focused on its use in earlier time points. However, she said, those early studies were small and had methodologic problems.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman’s study is the first large, placebo-controlled trial to examine the steroid’s use in the late preterm period. It was conducted in 17 centers and comprised 2,831 women with a singleton pregnancy of 34 to 36 weeks, 5 days’ gestation. All women were at high risk of delivery during the late preterm period, which was considered up to 36 weeks, 6 days.

Women were assigned to receive two injections of either 12 mg betamethasone or placebo 24 hours apart. The primary neonatal outcome was a composite of treatments required during the first 72 postnatal hours, including positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for at least 2 hours; supplemental oxygen for at least 4 hours; extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation; or stillbirth or neonatal death within that 72-hour period.

The women were a mean of 28 years old. Labor with intact membranes was the most common risk factor for preterm delivery; followed by ruptured membranes, and gestational diabetes or preeclampsia. Other risks included expected delivery for intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydramnios.

Outcomes data were available for 2,827 infants. There were no stillbirths or deaths within the first 72 hours.

The primary outcome was significantly less common among those who received betamethasone (11.6% vs. 14.4%; relative risk, 0.80). The number needed to treat to prevent one outcome was 35.

A secondary analysis eliminated 32 infants with a major congenital anomaly that had been unrecognized before birth; the significant benefit of betamethasone was unchanged.

The rate of the composite outcome of severe respiratory complications was also significantly lower in the betamethasone group (8.1% vs. 12.1%; RR, 0.67). The number needed to treat to prevent one case of a severe respiratory complication was 25.

While rates of respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, and pneumonia were similar in the two groups, other disorders were significantly less common in the treated group, including transient tachypnea of the newborn (6.7% vs. 9.9%); bronchopulmonary dysplasia (0.1% vs. 0.6%), and the composite of the respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, or apnea (13.9% vs. 17.8%).

Significantly fewer infants in the treatment group required resuscitation at birth (14.5% vs. 18.7%) and surfactant (1.8% vs. 3.1%).

The use of betamethasone was not associated with any clinically significant adverse neonatal effects with one exception, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 24%, compared with 15% of those in the placebo group – a significant 60% increased relative risk. There were no hypoglycemia-related adverse events; nor did the condition affect length of stay. In fact, infants with hypoglycemia were discharged an average of 2 days earlier than were those without “suggesting that the condition was self-limiting.” It was probably associated with earlier feeding in these babies, she added.

Late preterm birth is one of the largest risk factors for neonatal hypoglycemia, she noted.

“To put this in perspective, our numbers were similar or even less than those reported in the literature,” she said. “Our nurses are familiar with this risk and these babies are being checked regularly. We should be looking for it, in the way that we normally would.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported having no financial disclosures.

Watch Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman discuss the study here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ATLANTA – Administration of betamethasone to mothers at risk of late preterm birth reduced the risk of perinatal respiratory complications – including supplemental oxygen, ventilation, and death – by 20%.

The steroid was also associated with a 33% reduction in the risk of severe respiratory complications, Dr. Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516783.).

“This finding is practice changing and it’s ready for prime time,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said in an interview. “Right now there are 300,000 late preterm deliveries every year in this country, and if we can do something now to improve their outcomes without imparting any harm, then I think we should do that right away.”

Although standard practice for early preterm infants, betamethasone use in the late preterm period has not been well studied since the 1970s, said Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman of Columbia University, New York. At that time, it was determined to be unhelpful; since then, studies have focused on its use in earlier time points. However, she said, those early studies were small and had methodologic problems.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman’s study is the first large, placebo-controlled trial to examine the steroid’s use in the late preterm period. It was conducted in 17 centers and comprised 2,831 women with a singleton pregnancy of 34 to 36 weeks, 5 days’ gestation. All women were at high risk of delivery during the late preterm period, which was considered up to 36 weeks, 6 days.

Women were assigned to receive two injections of either 12 mg betamethasone or placebo 24 hours apart. The primary neonatal outcome was a composite of treatments required during the first 72 postnatal hours, including positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for at least 2 hours; supplemental oxygen for at least 4 hours; extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation; or stillbirth or neonatal death within that 72-hour period.

The women were a mean of 28 years old. Labor with intact membranes was the most common risk factor for preterm delivery; followed by ruptured membranes, and gestational diabetes or preeclampsia. Other risks included expected delivery for intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydramnios.

Outcomes data were available for 2,827 infants. There were no stillbirths or deaths within the first 72 hours.

The primary outcome was significantly less common among those who received betamethasone (11.6% vs. 14.4%; relative risk, 0.80). The number needed to treat to prevent one outcome was 35.

A secondary analysis eliminated 32 infants with a major congenital anomaly that had been unrecognized before birth; the significant benefit of betamethasone was unchanged.

The rate of the composite outcome of severe respiratory complications was also significantly lower in the betamethasone group (8.1% vs. 12.1%; RR, 0.67). The number needed to treat to prevent one case of a severe respiratory complication was 25.

While rates of respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, and pneumonia were similar in the two groups, other disorders were significantly less common in the treated group, including transient tachypnea of the newborn (6.7% vs. 9.9%); bronchopulmonary dysplasia (0.1% vs. 0.6%), and the composite of the respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, or apnea (13.9% vs. 17.8%).

Significantly fewer infants in the treatment group required resuscitation at birth (14.5% vs. 18.7%) and surfactant (1.8% vs. 3.1%).

The use of betamethasone was not associated with any clinically significant adverse neonatal effects with one exception, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 24%, compared with 15% of those in the placebo group – a significant 60% increased relative risk. There were no hypoglycemia-related adverse events; nor did the condition affect length of stay. In fact, infants with hypoglycemia were discharged an average of 2 days earlier than were those without “suggesting that the condition was self-limiting.” It was probably associated with earlier feeding in these babies, she added.

Late preterm birth is one of the largest risk factors for neonatal hypoglycemia, she noted.

“To put this in perspective, our numbers were similar or even less than those reported in the literature,” she said. “Our nurses are familiar with this risk and these babies are being checked regularly. We should be looking for it, in the way that we normally would.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported having no financial disclosures.

Watch Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman discuss the study here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

ATLANTA – Administration of betamethasone to mothers at risk of late preterm birth reduced the risk of perinatal respiratory complications – including supplemental oxygen, ventilation, and death – by 20%.

The steroid was also associated with a 33% reduction in the risk of severe respiratory complications, Dr. Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman reported at the annual Pregnancy Meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2016; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516783.).

“This finding is practice changing and it’s ready for prime time,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said in an interview. “Right now there are 300,000 late preterm deliveries every year in this country, and if we can do something now to improve their outcomes without imparting any harm, then I think we should do that right away.”

Although standard practice for early preterm infants, betamethasone use in the late preterm period has not been well studied since the 1970s, said Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman of Columbia University, New York. At that time, it was determined to be unhelpful; since then, studies have focused on its use in earlier time points. However, she said, those early studies were small and had methodologic problems.

Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman’s study is the first large, placebo-controlled trial to examine the steroid’s use in the late preterm period. It was conducted in 17 centers and comprised 2,831 women with a singleton pregnancy of 34 to 36 weeks, 5 days’ gestation. All women were at high risk of delivery during the late preterm period, which was considered up to 36 weeks, 6 days.

Women were assigned to receive two injections of either 12 mg betamethasone or placebo 24 hours apart. The primary neonatal outcome was a composite of treatments required during the first 72 postnatal hours, including positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for at least 2 hours; supplemental oxygen for at least 4 hours; extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation; or stillbirth or neonatal death within that 72-hour period.

The women were a mean of 28 years old. Labor with intact membranes was the most common risk factor for preterm delivery; followed by ruptured membranes, and gestational diabetes or preeclampsia. Other risks included expected delivery for intrauterine growth restriction or oligohydramnios.

Outcomes data were available for 2,827 infants. There were no stillbirths or deaths within the first 72 hours.

The primary outcome was significantly less common among those who received betamethasone (11.6% vs. 14.4%; relative risk, 0.80). The number needed to treat to prevent one outcome was 35.

A secondary analysis eliminated 32 infants with a major congenital anomaly that had been unrecognized before birth; the significant benefit of betamethasone was unchanged.

The rate of the composite outcome of severe respiratory complications was also significantly lower in the betamethasone group (8.1% vs. 12.1%; RR, 0.67). The number needed to treat to prevent one case of a severe respiratory complication was 25.

While rates of respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, and pneumonia were similar in the two groups, other disorders were significantly less common in the treated group, including transient tachypnea of the newborn (6.7% vs. 9.9%); bronchopulmonary dysplasia (0.1% vs. 0.6%), and the composite of the respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, or apnea (13.9% vs. 17.8%).

Significantly fewer infants in the treatment group required resuscitation at birth (14.5% vs. 18.7%) and surfactant (1.8% vs. 3.1%).

The use of betamethasone was not associated with any clinically significant adverse neonatal effects with one exception, Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman said. Neonatal hypoglycemia occurred in 24%, compared with 15% of those in the placebo group – a significant 60% increased relative risk. There were no hypoglycemia-related adverse events; nor did the condition affect length of stay. In fact, infants with hypoglycemia were discharged an average of 2 days earlier than were those without “suggesting that the condition was self-limiting.” It was probably associated with earlier feeding in these babies, she added.

Late preterm birth is one of the largest risk factors for neonatal hypoglycemia, she noted.

“To put this in perspective, our numbers were similar or even less than those reported in the literature,” she said. “Our nurses are familiar with this risk and these babies are being checked regularly. We should be looking for it, in the way that we normally would.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported having no financial disclosures.

Watch Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman discuss the study here.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Betamethasone improves neonatal respiratory outcomes in late preterm births.

Major finding: When administered in the later preterm period, betamethasone reduced the risk of severe perinatal respiratory complications by 20%, compared with placebo.

Data source: A randomized trial of 2,831 women with a singleton pregnancy.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman reported having no financial disclosures.

Metformin trims mother’s weight, but not baby’s

In obese pregnant women without diabetes, daily metformin reduces maternal weight gain, but not infant birth weight, results of the MOP trial show.

The incidence of preeclampsia was also lower with metformin than with placebo (3.0% vs. 11.3%; odds ratio, 0.24; P =.001).

There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of other pregnancy complications or of adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes, Argyro Syngelaki, Ph.D., of King’s College Hospital in London, and her colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 3;374:434-43.).

Attempts at reducing the incidence of pregnancy complications associated with obesity have focused on dietary and lifestyle interventions but have generally been unsuccessful, she noted.

Additionally, the recent randomized EMPOWaR (Effect of Metformin on Maternal and Fetal Outcomes) trial failed to show that metformin use was associated with less gestational weight gain and a lower incidence of preeclampsia than did placebo.

EMPOWaR, however, used a body mass index (BMI) cutoff of 30 kg/m2 and a 2.5-g dose of metformin, compared with a BMI cutoff of 35 and the 3.0-g dose used in the MOP (Metformin in Obese Non-diabetic Pregnant Women) trial, Dr. Syngelaki observed.

Adherence to metformin was also higher in the MOP trial. Nearly 66% of women took a minimum metformin dose of 2.5 g for at least 50% of the days between randomization and delivery, compared with 2.5 g of metformin being used for only 38% of the days in the same period in EMPOWaR. The proportion of patients who were in this dose subgroup in the EMPOWaR trial was not specified.

MOP investigators randomly assigned 400 women with a singleton pregnancy to metformin or placebo from 12-18 weeks of gestation until delivery. All women underwent a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test at 28 weeks’ gestation, with metformin and placebo stopped for 1 week before the test. Women with abnormal oral glucose tolerance test results continued the assigned study regimen, and began home glucose monitoring. Insulin was added to their regimen, if target blood-glucose values were not achieved.

The metformin and placebo groups were well matched at baseline with respect to median maternal age (32.9 years vs. 30.8 years), median BMI (38.6 kg/m2 vs. 38.4 kg/m2), and spontaneous conception (97.5% vs. 98.0%).

Metformin did not reduce the primary outcome of median neonatal birth-weight z score, compared with placebo (0.05 vs. 0.17; P = .66) or the incidence of large for gestational age neonates (16.8% vs. 15.4%; P = .79), the MOP investigators reported.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of miscarriage (zero vs. three cases), stillbirths (one case vs. two cases), or neonatal death (zero vs. one case).

The median maternal gestational weight gain, however, was lower with metformin than placebo (4.6 kg vs 6.3 kg; P less than .001), as was the incidence of preeclampsia.

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study was that it was not adequately powered for the secondary outcomes, but said the preeclampsia finding is compatible with several previous studies reporting that the prevalence of this potentially deadly complication increased with increasing prepregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain.

Side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and headache were as expected during gestation, although the incidence was significantly higher in the metformin group. Still, there was no significant between-group differences with regard to the decision to continue with the full dose, reduce the dose, or stop the study regimen.

“The rate of adherence was considerably higher among women taking the full dose of 3.0 g per day than among those taking less than 2.0 g per day, which suggests that adherence was not driven by the presence or absence of side effects, but by the motivation of the patients to adhere to the demands of the study,” the investigators wrote.

The Fetal Medicine Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

In obese pregnant women without diabetes, daily metformin reduces maternal weight gain, but not infant birth weight, results of the MOP trial show.

The incidence of preeclampsia was also lower with metformin than with placebo (3.0% vs. 11.3%; odds ratio, 0.24; P =.001).

There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of other pregnancy complications or of adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes, Argyro Syngelaki, Ph.D., of King’s College Hospital in London, and her colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 3;374:434-43.).

Attempts at reducing the incidence of pregnancy complications associated with obesity have focused on dietary and lifestyle interventions but have generally been unsuccessful, she noted.

Additionally, the recent randomized EMPOWaR (Effect of Metformin on Maternal and Fetal Outcomes) trial failed to show that metformin use was associated with less gestational weight gain and a lower incidence of preeclampsia than did placebo.

EMPOWaR, however, used a body mass index (BMI) cutoff of 30 kg/m2 and a 2.5-g dose of metformin, compared with a BMI cutoff of 35 and the 3.0-g dose used in the MOP (Metformin in Obese Non-diabetic Pregnant Women) trial, Dr. Syngelaki observed.

Adherence to metformin was also higher in the MOP trial. Nearly 66% of women took a minimum metformin dose of 2.5 g for at least 50% of the days between randomization and delivery, compared with 2.5 g of metformin being used for only 38% of the days in the same period in EMPOWaR. The proportion of patients who were in this dose subgroup in the EMPOWaR trial was not specified.

MOP investigators randomly assigned 400 women with a singleton pregnancy to metformin or placebo from 12-18 weeks of gestation until delivery. All women underwent a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test at 28 weeks’ gestation, with metformin and placebo stopped for 1 week before the test. Women with abnormal oral glucose tolerance test results continued the assigned study regimen, and began home glucose monitoring. Insulin was added to their regimen, if target blood-glucose values were not achieved.

The metformin and placebo groups were well matched at baseline with respect to median maternal age (32.9 years vs. 30.8 years), median BMI (38.6 kg/m2 vs. 38.4 kg/m2), and spontaneous conception (97.5% vs. 98.0%).

Metformin did not reduce the primary outcome of median neonatal birth-weight z score, compared with placebo (0.05 vs. 0.17; P = .66) or the incidence of large for gestational age neonates (16.8% vs. 15.4%; P = .79), the MOP investigators reported.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of miscarriage (zero vs. three cases), stillbirths (one case vs. two cases), or neonatal death (zero vs. one case).

The median maternal gestational weight gain, however, was lower with metformin than placebo (4.6 kg vs 6.3 kg; P less than .001), as was the incidence of preeclampsia.

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study was that it was not adequately powered for the secondary outcomes, but said the preeclampsia finding is compatible with several previous studies reporting that the prevalence of this potentially deadly complication increased with increasing prepregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain.

Side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and headache were as expected during gestation, although the incidence was significantly higher in the metformin group. Still, there was no significant between-group differences with regard to the decision to continue with the full dose, reduce the dose, or stop the study regimen.

“The rate of adherence was considerably higher among women taking the full dose of 3.0 g per day than among those taking less than 2.0 g per day, which suggests that adherence was not driven by the presence or absence of side effects, but by the motivation of the patients to adhere to the demands of the study,” the investigators wrote.

The Fetal Medicine Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

In obese pregnant women without diabetes, daily metformin reduces maternal weight gain, but not infant birth weight, results of the MOP trial show.

The incidence of preeclampsia was also lower with metformin than with placebo (3.0% vs. 11.3%; odds ratio, 0.24; P =.001).

There was no significant difference between the two groups in the incidence of other pregnancy complications or of adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes, Argyro Syngelaki, Ph.D., of King’s College Hospital in London, and her colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 3;374:434-43.).

Attempts at reducing the incidence of pregnancy complications associated with obesity have focused on dietary and lifestyle interventions but have generally been unsuccessful, she noted.

Additionally, the recent randomized EMPOWaR (Effect of Metformin on Maternal and Fetal Outcomes) trial failed to show that metformin use was associated with less gestational weight gain and a lower incidence of preeclampsia than did placebo.

EMPOWaR, however, used a body mass index (BMI) cutoff of 30 kg/m2 and a 2.5-g dose of metformin, compared with a BMI cutoff of 35 and the 3.0-g dose used in the MOP (Metformin in Obese Non-diabetic Pregnant Women) trial, Dr. Syngelaki observed.

Adherence to metformin was also higher in the MOP trial. Nearly 66% of women took a minimum metformin dose of 2.5 g for at least 50% of the days between randomization and delivery, compared with 2.5 g of metformin being used for only 38% of the days in the same period in EMPOWaR. The proportion of patients who were in this dose subgroup in the EMPOWaR trial was not specified.

MOP investigators randomly assigned 400 women with a singleton pregnancy to metformin or placebo from 12-18 weeks of gestation until delivery. All women underwent a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test at 28 weeks’ gestation, with metformin and placebo stopped for 1 week before the test. Women with abnormal oral glucose tolerance test results continued the assigned study regimen, and began home glucose monitoring. Insulin was added to their regimen, if target blood-glucose values were not achieved.

The metformin and placebo groups were well matched at baseline with respect to median maternal age (32.9 years vs. 30.8 years), median BMI (38.6 kg/m2 vs. 38.4 kg/m2), and spontaneous conception (97.5% vs. 98.0%).

Metformin did not reduce the primary outcome of median neonatal birth-weight z score, compared with placebo (0.05 vs. 0.17; P = .66) or the incidence of large for gestational age neonates (16.8% vs. 15.4%; P = .79), the MOP investigators reported.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of miscarriage (zero vs. three cases), stillbirths (one case vs. two cases), or neonatal death (zero vs. one case).

The median maternal gestational weight gain, however, was lower with metformin than placebo (4.6 kg vs 6.3 kg; P less than .001), as was the incidence of preeclampsia.

The authors acknowledged that a limitation of the study was that it was not adequately powered for the secondary outcomes, but said the preeclampsia finding is compatible with several previous studies reporting that the prevalence of this potentially deadly complication increased with increasing prepregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain.

Side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and headache were as expected during gestation, although the incidence was significantly higher in the metformin group. Still, there was no significant between-group differences with regard to the decision to continue with the full dose, reduce the dose, or stop the study regimen.

“The rate of adherence was considerably higher among women taking the full dose of 3.0 g per day than among those taking less than 2.0 g per day, which suggests that adherence was not driven by the presence or absence of side effects, but by the motivation of the patients to adhere to the demands of the study,” the investigators wrote.

The Fetal Medicine Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Antenatal metformin use reduces maternal weight gain, but not neonatal birth weight.

Major finding: The median maternal gestational weight gain was 4.6 kg with metformin and 6.3 kg with placebo (P less than .001).

Data source: Double-blind, randomized trial in 400 obese pregnant women without diabetes.

Disclosures: The Fetal Medicine Foundation funded the study. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

2016 Update on fertility

Patients seeking fertility care commonly ask the physician for advice regarding ways to optimize their conception attempts. While evidence from randomized controlled trials is not available, data from observational studies provide parameters that can inform patient decision making. Knowledge about the fertility window, the decline in fecundability with age, and lifestyle practices that promote conception may be helpful to clinicians and aid in their ability to guide patients.

For those patients who will not achieve conception naturally, assisted reproductive technologies (ART) offer a promising alternative. ART options have improved greatly in effectiveness and safety since Louise Brown was born in 1978. More than 5 million babies have been born globally.1 However, even though the United States is wealthy, access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) is poor relative to many other countries, with not more than 1 in 3 people needing IVF actually receiving the treatment. Understanding the international experience enables physicians to take actions that help increase access for their patients who need IVF.

In this article we not only address ways in which your patients can optimize their natural fertility but also examine this country’s ability to offer ART options when they are needed. Without such examination, fundamental changes in societal attitudes toward infertility and payor attitudes toward reproductive care will not occur, and it is these changes, among others, that can move this country to more equitable ART access.

- Adamson GD, Tabangin M, Macaluso M, de Mouzon J. The number of babies born globally after treatment with the Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART). Paper presented at International Federation of Fertility Societies/American Society for Reproductive Medicine Conjoint Meeting; October 12–17, 2013; Boston, Massachusetts.

- Dunson DB, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR. Day-specific probabilities of clinical pregnancy based on two studies with imperfect measures of ovulation. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(7):1835–1839.

- Keulers MJ, Hamilton CJ, Franx A, et al. The length of the fertile window is associated with the chance of spontaneously conceiving an ongoing pregnancy in subfertile couples. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1652–1656.

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(23):1517–1521.

- Levitas E, Lunenfeld E, Weiss N, et al. Relationship between the duration of sexual abstinence and semen quality: analysis of 9,489 semen samples. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(6):1680–1686.

- Elzanaty S, Malm J, Giwercman A. Duration of sexual abstinence: epididymal and accessory sex gland secretions and their relationship to sperm motility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):221–225.

- Check JH, Epstein R, Long R. Effect of time interval between ejaculations on semen parameters. Arch Androl. 1991;27(2):93–95.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Optimizing natural fertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):631–637.

- Gnoth C, Godehardt E, Frank-Herrmann P, Friol K, Tigges J, Freundi G. Definition and prevalence of subfertility and infertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(5):1144–1447.

- Howe G, Westhoff C, Vessey M, Yeates D. Effects of age, cigarette smoking, and other factors on fertility: findings in a large prospective study. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290(6483):1697–700.

- Dunson DB, Baird DD, Colombo B. Increased infertility with age in men and women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):51–56.

- Dunson DB, Colombo B, Baird DD. Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1399–1403.

- Lumley J, Watson L, Watson M, Bower C. Periconceptional supplementation with folate and/or multivitamins for preventing neural tube defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001056.

- Augood C, Duckitt K, Templeton AA. Smoking and female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(6):1532–1539.

- Winter E, Wang J, Davies MJ, Norman R. Early pregnancy loss following assisted reproductive technology treatment. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(12):3220–3223.

- Ness RB, Grisso JA, Hirschinger N, et al. Cocaine and tobacco use and the risk of spontaneous abortion. New Engl J Med. 1999;340(5):333–339.

- Mattison DR, Plowchalk DR, Meadows MJ, Miller MM, Malek A, London S. The effect of smoking on oogenesis, fertilization and implantation. Semin Reprod Med. 1989;7(4):291–304.

- Adena MA, Gallagher HG. Cigarette smoking and the age at menopause. Ann Hum Biol. 1982;9(2):121–130.

- Bolumar F, Olsen J, Rebagliato M, Bisanti L. Caffeine intake and delayed conception: a European multicenter study on infertility and subfecundity. European Study Group on Infertility Subfecundity. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(4):324–334.

- Wilcox A, Weinberg C, Baird D. Caffeinated beverages and decreased fertility. Lancet. 1988;2(8626–8627):1453–1456.

- Signorello LB, McLaughlin JK. Maternal caffeine consumption and spontaneous abortion: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiology. 2004;15(2):229–239.

- Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ. Moderate alcohol intake in pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion. Alcohol. 2002;37(1):87–92.

- Adamson GD; International Council of Medical Acupuncture and Related Techniques (ICMART). ICMART World Report 2011. Webcast presented at: Annual Meeting European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE); June 16, 2015; Lisbon, Portugal.

- Chambers G, Phuong Hoang V, et al. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(1):191–198.

- Stovall DW, Allen BD, Sparks AE, Syrop CH, Saunders RG, VanVoorhis BJ. The cost of infertility evaluation and therapy: findings of a self-insured university healthcare plan. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(5):778–784.

- Chambers GM, Sullivan E, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2281–2294.

- Hamilton BH, McManus B. The effects of insurance mandates on choices and outcomes in infertility treatment markets. Health Econ. 2012;21(8):994–1016.

- Chambers GM, Adamson GD, Eijkemans MJC. Acceptable cost for the patient and society. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(2):319–327.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al; ICMART, WHO. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART); World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524.

Patients seeking fertility care commonly ask the physician for advice regarding ways to optimize their conception attempts. While evidence from randomized controlled trials is not available, data from observational studies provide parameters that can inform patient decision making. Knowledge about the fertility window, the decline in fecundability with age, and lifestyle practices that promote conception may be helpful to clinicians and aid in their ability to guide patients.

For those patients who will not achieve conception naturally, assisted reproductive technologies (ART) offer a promising alternative. ART options have improved greatly in effectiveness and safety since Louise Brown was born in 1978. More than 5 million babies have been born globally.1 However, even though the United States is wealthy, access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) is poor relative to many other countries, with not more than 1 in 3 people needing IVF actually receiving the treatment. Understanding the international experience enables physicians to take actions that help increase access for their patients who need IVF.

In this article we not only address ways in which your patients can optimize their natural fertility but also examine this country’s ability to offer ART options when they are needed. Without such examination, fundamental changes in societal attitudes toward infertility and payor attitudes toward reproductive care will not occur, and it is these changes, among others, that can move this country to more equitable ART access.

Patients seeking fertility care commonly ask the physician for advice regarding ways to optimize their conception attempts. While evidence from randomized controlled trials is not available, data from observational studies provide parameters that can inform patient decision making. Knowledge about the fertility window, the decline in fecundability with age, and lifestyle practices that promote conception may be helpful to clinicians and aid in their ability to guide patients.

For those patients who will not achieve conception naturally, assisted reproductive technologies (ART) offer a promising alternative. ART options have improved greatly in effectiveness and safety since Louise Brown was born in 1978. More than 5 million babies have been born globally.1 However, even though the United States is wealthy, access to in vitro fertilization (IVF) is poor relative to many other countries, with not more than 1 in 3 people needing IVF actually receiving the treatment. Understanding the international experience enables physicians to take actions that help increase access for their patients who need IVF.

In this article we not only address ways in which your patients can optimize their natural fertility but also examine this country’s ability to offer ART options when they are needed. Without such examination, fundamental changes in societal attitudes toward infertility and payor attitudes toward reproductive care will not occur, and it is these changes, among others, that can move this country to more equitable ART access.

- Adamson GD, Tabangin M, Macaluso M, de Mouzon J. The number of babies born globally after treatment with the Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART). Paper presented at International Federation of Fertility Societies/American Society for Reproductive Medicine Conjoint Meeting; October 12–17, 2013; Boston, Massachusetts.

- Dunson DB, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR. Day-specific probabilities of clinical pregnancy based on two studies with imperfect measures of ovulation. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(7):1835–1839.

- Keulers MJ, Hamilton CJ, Franx A, et al. The length of the fertile window is associated with the chance of spontaneously conceiving an ongoing pregnancy in subfertile couples. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1652–1656.

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(23):1517–1521.

- Levitas E, Lunenfeld E, Weiss N, et al. Relationship between the duration of sexual abstinence and semen quality: analysis of 9,489 semen samples. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(6):1680–1686.

- Elzanaty S, Malm J, Giwercman A. Duration of sexual abstinence: epididymal and accessory sex gland secretions and their relationship to sperm motility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):221–225.

- Check JH, Epstein R, Long R. Effect of time interval between ejaculations on semen parameters. Arch Androl. 1991;27(2):93–95.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Optimizing natural fertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):631–637.

- Gnoth C, Godehardt E, Frank-Herrmann P, Friol K, Tigges J, Freundi G. Definition and prevalence of subfertility and infertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(5):1144–1447.

- Howe G, Westhoff C, Vessey M, Yeates D. Effects of age, cigarette smoking, and other factors on fertility: findings in a large prospective study. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290(6483):1697–700.

- Dunson DB, Baird DD, Colombo B. Increased infertility with age in men and women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):51–56.

- Dunson DB, Colombo B, Baird DD. Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1399–1403.

- Lumley J, Watson L, Watson M, Bower C. Periconceptional supplementation with folate and/or multivitamins for preventing neural tube defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001056.

- Augood C, Duckitt K, Templeton AA. Smoking and female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(6):1532–1539.

- Winter E, Wang J, Davies MJ, Norman R. Early pregnancy loss following assisted reproductive technology treatment. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(12):3220–3223.

- Ness RB, Grisso JA, Hirschinger N, et al. Cocaine and tobacco use and the risk of spontaneous abortion. New Engl J Med. 1999;340(5):333–339.

- Mattison DR, Plowchalk DR, Meadows MJ, Miller MM, Malek A, London S. The effect of smoking on oogenesis, fertilization and implantation. Semin Reprod Med. 1989;7(4):291–304.

- Adena MA, Gallagher HG. Cigarette smoking and the age at menopause. Ann Hum Biol. 1982;9(2):121–130.

- Bolumar F, Olsen J, Rebagliato M, Bisanti L. Caffeine intake and delayed conception: a European multicenter study on infertility and subfecundity. European Study Group on Infertility Subfecundity. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(4):324–334.

- Wilcox A, Weinberg C, Baird D. Caffeinated beverages and decreased fertility. Lancet. 1988;2(8626–8627):1453–1456.

- Signorello LB, McLaughlin JK. Maternal caffeine consumption and spontaneous abortion: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiology. 2004;15(2):229–239.

- Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ. Moderate alcohol intake in pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion. Alcohol. 2002;37(1):87–92.

- Adamson GD; International Council of Medical Acupuncture and Related Techniques (ICMART). ICMART World Report 2011. Webcast presented at: Annual Meeting European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE); June 16, 2015; Lisbon, Portugal.

- Chambers G, Phuong Hoang V, et al. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(1):191–198.

- Stovall DW, Allen BD, Sparks AE, Syrop CH, Saunders RG, VanVoorhis BJ. The cost of infertility evaluation and therapy: findings of a self-insured university healthcare plan. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(5):778–784.

- Chambers GM, Sullivan E, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2281–2294.

- Hamilton BH, McManus B. The effects of insurance mandates on choices and outcomes in infertility treatment markets. Health Econ. 2012;21(8):994–1016.

- Chambers GM, Adamson GD, Eijkemans MJC. Acceptable cost for the patient and society. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(2):319–327.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al; ICMART, WHO. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART); World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524.

- Adamson GD, Tabangin M, Macaluso M, de Mouzon J. The number of babies born globally after treatment with the Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART). Paper presented at International Federation of Fertility Societies/American Society for Reproductive Medicine Conjoint Meeting; October 12–17, 2013; Boston, Massachusetts.

- Dunson DB, Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR. Day-specific probabilities of clinical pregnancy based on two studies with imperfect measures of ovulation. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(7):1835–1839.

- Keulers MJ, Hamilton CJ, Franx A, et al. The length of the fertile window is associated with the chance of spontaneously conceiving an ongoing pregnancy in subfertile couples. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1652–1656.

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(23):1517–1521.

- Levitas E, Lunenfeld E, Weiss N, et al. Relationship between the duration of sexual abstinence and semen quality: analysis of 9,489 semen samples. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(6):1680–1686.

- Elzanaty S, Malm J, Giwercman A. Duration of sexual abstinence: epididymal and accessory sex gland secretions and their relationship to sperm motility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):221–225.

- Check JH, Epstein R, Long R. Effect of time interval between ejaculations on semen parameters. Arch Androl. 1991;27(2):93–95.

- Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Optimizing natural fertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):631–637.

- Gnoth C, Godehardt E, Frank-Herrmann P, Friol K, Tigges J, Freundi G. Definition and prevalence of subfertility and infertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(5):1144–1447.

- Howe G, Westhoff C, Vessey M, Yeates D. Effects of age, cigarette smoking, and other factors on fertility: findings in a large prospective study. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1985;290(6483):1697–700.

- Dunson DB, Baird DD, Colombo B. Increased infertility with age in men and women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(1):51–56.

- Dunson DB, Colombo B, Baird DD. Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1399–1403.

- Lumley J, Watson L, Watson M, Bower C. Periconceptional supplementation with folate and/or multivitamins for preventing neural tube defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001056.

- Augood C, Duckitt K, Templeton AA. Smoking and female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(6):1532–1539.

- Winter E, Wang J, Davies MJ, Norman R. Early pregnancy loss following assisted reproductive technology treatment. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(12):3220–3223.

- Ness RB, Grisso JA, Hirschinger N, et al. Cocaine and tobacco use and the risk of spontaneous abortion. New Engl J Med. 1999;340(5):333–339.

- Mattison DR, Plowchalk DR, Meadows MJ, Miller MM, Malek A, London S. The effect of smoking on oogenesis, fertilization and implantation. Semin Reprod Med. 1989;7(4):291–304.

- Adena MA, Gallagher HG. Cigarette smoking and the age at menopause. Ann Hum Biol. 1982;9(2):121–130.

- Bolumar F, Olsen J, Rebagliato M, Bisanti L. Caffeine intake and delayed conception: a European multicenter study on infertility and subfecundity. European Study Group on Infertility Subfecundity. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(4):324–334.

- Wilcox A, Weinberg C, Baird D. Caffeinated beverages and decreased fertility. Lancet. 1988;2(8626–8627):1453–1456.

- Signorello LB, McLaughlin JK. Maternal caffeine consumption and spontaneous abortion: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Epidemiology. 2004;15(2):229–239.

- Kesmodel U, Wisborg K, Olsen SF, Henriksen TB, Secher NJ. Moderate alcohol intake in pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion. Alcohol. 2002;37(1):87–92.

- Adamson GD; International Council of Medical Acupuncture and Related Techniques (ICMART). ICMART World Report 2011. Webcast presented at: Annual Meeting European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE); June 16, 2015; Lisbon, Portugal.

- Chambers G, Phuong Hoang V, et al. The impact of consumer affordability on access to assisted reproductive technologies and embryo transfer practices: an international analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(1):191–198.

- Stovall DW, Allen BD, Sparks AE, Syrop CH, Saunders RG, VanVoorhis BJ. The cost of infertility evaluation and therapy: findings of a self-insured university healthcare plan. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(5):778–784.

- Chambers GM, Sullivan E, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2281–2294.

- Hamilton BH, McManus B. The effects of insurance mandates on choices and outcomes in infertility treatment markets. Health Econ. 2012;21(8):994–1016.

- Chambers GM, Adamson GD, Eijkemans MJC. Acceptable cost for the patient and society. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(2):319–327.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al; ICMART, WHO. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART); World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524.

In this Article

- Factors affecting the probability of conception

- Barriers to ART access

- Ways to increase ART funding

Vacuum extraction: Tips for achieving an optimal outcome

CASE: Is vacuum extraction right for this delivery?

A 41-year-old woman (G2P2002) is at term in her third pregnancy, and the fetus exhibits prolonged deceleration that does not resolve while the mother pushes from a +3 station. The fetus, estimated to weigh 8 lb, is in the occiput anterior (OA) position. The mother is willing to consider vaginal extraction, and you must weigh the factors that may influence successful delivery.

Vacuum extraction (VE) is an effective method to facilitate delivery. From 2007 to 2013, VE was used to facilitate about 3% of vaginal deliveries in the United States.1 By contrast, cesarean delivery rates over the same period averaged about 30%.2

Controversy exists on the pros and cons of operative vaginal deliveries versus cesarean delivery, as well as on the instruments and operational approaches used. While opinion tends to be resolute and influential, evidence remains inconclusive.

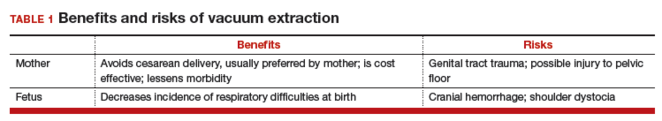

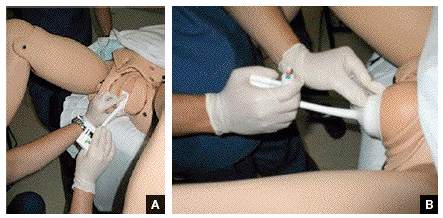

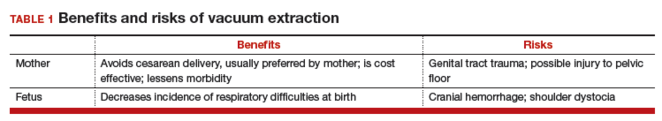

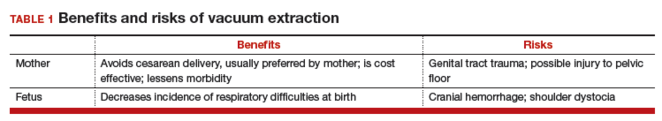

Multiple factors influence a decision on whether to choose VE. The clinician’s own bias regarding delivery routes and comfort level with performing VE are important. The patient, too, may have preconceived opinions about VE. Knowing the indications for VE and its benefits and risks (TABLE 1) can help the patient make an informed choice and the counseling on which will be needed in obtaining the patient’s informed consent. The expectations and desires of the patient in concert with the experience and skill of the clinician will serve to achieve the optimal decision.

Indications for VE

Maternal indications for the use of VE include prolongation or arrest of the second stage of labor. Another indication is the need to shorten the second stage due to a maternal cardiac or cardiovascular disorder or due to maternal exhaustion.

Fetal indications include nonreassuring fetal status or a need to correct for minor degrees of malposition (asynclitism, deflexion) that historically have been addressed with the use of obstetric forceps. VE delivery in these circumstances requires a very experienced and skilled operator.

Further selection criteria

Birthweight influences the consideration of VE. Low birthweight or prematurity are contraindications to the use of VE due to concerns about fetal/neonatal bleeding. Large fetuses will have issues with cephalopelvic disproportion, thus increasing the risk for 2 disorders: shoulder dystocia and fetal cranial bleeding.

Cranial bleeding, both intracranial and extracranial, can result in serious neonatal morbidity and mortality. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with the use of VE. In using VE, force is transmitted to the fetal scalp. The scalp then has the tendency to pull on its contents and attachments—skull bones, brain, fluids, etc. The scalp attachments include vessels at right angles to the scalp, which may be traumatized or torn by the pulling force. This may lead to subgaleal hemorrhage, a collection of blood in the large potential space below the scalp and above the aponeurosis. Enough force may be generated to deform the intracranial contents and cause intracranial bleeding.

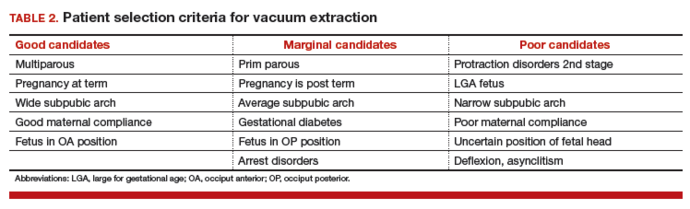

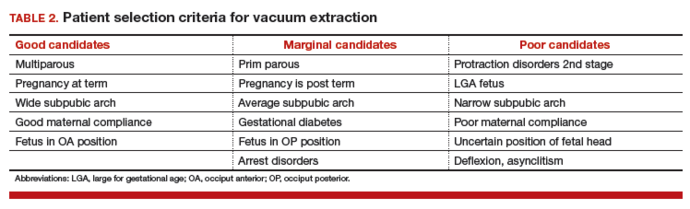

The likelihood of success with VE varies depending on maternal anatomy, the position of the fetal head, gestational age, and the presence or absence of gestational diabetes (TABLE 2).

Delivery by VE: Main considerations

After determining that a candidate is suitable for VE and obtaining informed consent, consider key operative factors:

- choice of extraction cup

- adequate anesthesia

- careful maternal positioning

- maternal bladder emptying

- review of fetal status.

Two major cup types are available: rigid and flexible.

Rigid plastic cup. This design is similar to the metal cup used by Malmström and attaches to the scalp via chignon formation. A variation of the rigid cup is the mityvac “M” that mimics the Malmström design but incorporates a semiflexible handle to facilitate proper cup placement and aid in the direction of pulling force.

Flexible cup. This type of cup flattens against the scalp with vacuum and may result in less minor scalp trauma than the rigid cup.

Greater force can be employed with rigid cup designs than with flexible cups, which can increase the chances of a successful delivery when the fetus is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. Flexible designs tend to cause less damage to the scalp than the rigid cup but are reported to have a higher failure rate.

Cardinal rule of any procedure. Prior to cup placement, remember this rule: abandon the procedure if it proves too difficult. Most deliveries will occur with 3 or 4 pulls.3 Difficulties include:

- failure to gain station with the initial pull

- repetitive cup pop-offs (3 or more)

- an excessive duration of the procedure (>10 minutes).

Less than optimal placement of the vacuum extractor will increase the risk of scalp trauma, particularly in nulliparous women.3

If the procedure is unsuccessful, the resulting options include cesarean delivery and expectant management.

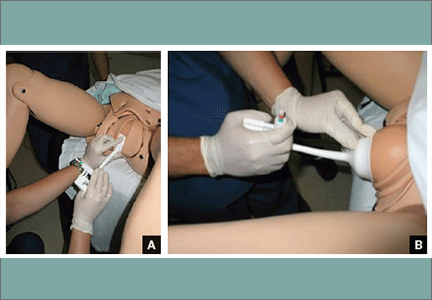

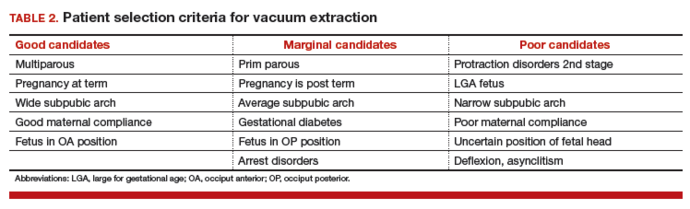

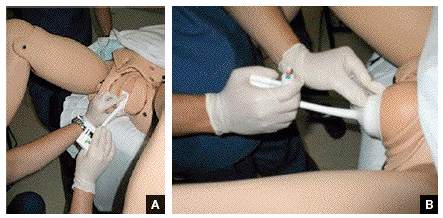

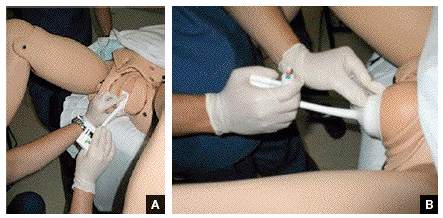

Tip. Use both hands during the pull to more reliably detect a problem with cup attachment, thereby minimizing the possibility of detachment and subsequent scalp trauma (FIGURE).

Key points of technique

Perform a careful and thorough pelvic examination to determine fetal station, position, attitude, and synclitism.

The optimal cup placement is 2- to 3-cm proximal to the posterior fontanel or, alternatively, 5- to 6-cm distal to the anterior fontanel, assuming the fetal head is properly flexed.4 The correct point of flexion will result in the smallest diameter of the fetal head presenting to the birth canal and should minimize the force necessary to achieve delivery.

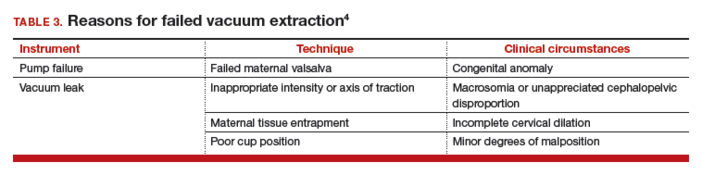

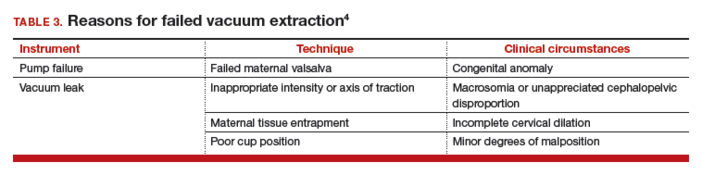

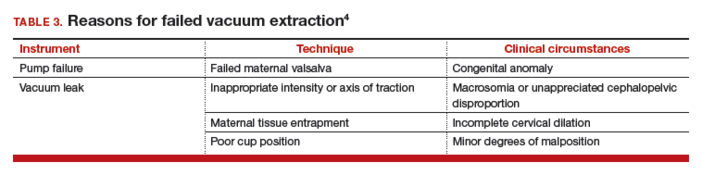

Use minimal vacuum to attach the cup to the fetal head. As the subsequent contraction develops, apply full vacuum with the hand device. Encourage maternal expulsive effort and use traction only in concert with pushing efforts. Three pushes facilitated with pulling may be achieved during a single contraction. Failure to bring about descent with the initial pull indicates potential failure with this approach and, in the absence of technical reasons for the failure, merits serious consideration of abandoning the procedure (TABLE 3).

In the event of failed delivery with VE, it is important to recognize that you should not make a second attempt with another instrument; the chance of success is low and the risk of injury is significantly increased.5

Carefully document the decision for VE and its implementation

The medical record is the most important witness to the event. Clearly record the following items, preferably as close in time to the decision/event as possible:

- the indication for the procedure

- the antecedent labor course

- maternal anesthesia

- personnel present

- instruments employed

- position and station of the fetal head

- force and duration of traction

- nature of the attempt

- immediate condition of the neonate, and any resuscitative efforts.

Closing reminders and advice

In preparing to discuss the patient’s preferences for delivery, understand clearly the risks and benefits of VE and develop a comfortable approach to sharing this information with your patient and her family. Also, if VE is selected, consider performing the procedure in the cesarean delivery room. This will serve to remind you to be mindful to abandon the procedure, if need be, at an appropriate point.

CASE: Resolved

You apply the vacuum extractor, and a small amount of vacuum demonstrates satisfactory attachment. On the second pull, the fetus easily delivers, and the Apgar scores are 8 and 8. The birthweight is 3,725 g. The vacuum-assisted delivery has resulted in the shortest delay in delivery and without adverse consequences for neonate or mother.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65.

- Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 154 Summary: operative vaginal delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1118–1119.

- Baskett TF, Fanning CA, Young DC. A prospective observational study of 1000 vacuum assisted deliveries with the OmniCup device. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(7):573–580.

- O’Grady JP. Instrumental delivery. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello LA, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008:475.

- Towner D, Castro MA, Eby-Wilkens E, Gilbert WM. Effect of mode of delivery in nulliparous women on neonatal intracranial injury. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(23):1709–1714.

CASE: Is vacuum extraction right for this delivery?

A 41-year-old woman (G2P2002) is at term in her third pregnancy, and the fetus exhibits prolonged deceleration that does not resolve while the mother pushes from a +3 station. The fetus, estimated to weigh 8 lb, is in the occiput anterior (OA) position. The mother is willing to consider vaginal extraction, and you must weigh the factors that may influence successful delivery.

Vacuum extraction (VE) is an effective method to facilitate delivery. From 2007 to 2013, VE was used to facilitate about 3% of vaginal deliveries in the United States.1 By contrast, cesarean delivery rates over the same period averaged about 30%.2

Controversy exists on the pros and cons of operative vaginal deliveries versus cesarean delivery, as well as on the instruments and operational approaches used. While opinion tends to be resolute and influential, evidence remains inconclusive.

Multiple factors influence a decision on whether to choose VE. The clinician’s own bias regarding delivery routes and comfort level with performing VE are important. The patient, too, may have preconceived opinions about VE. Knowing the indications for VE and its benefits and risks (TABLE 1) can help the patient make an informed choice and the counseling on which will be needed in obtaining the patient’s informed consent. The expectations and desires of the patient in concert with the experience and skill of the clinician will serve to achieve the optimal decision.

Indications for VE

Maternal indications for the use of VE include prolongation or arrest of the second stage of labor. Another indication is the need to shorten the second stage due to a maternal cardiac or cardiovascular disorder or due to maternal exhaustion.

Fetal indications include nonreassuring fetal status or a need to correct for minor degrees of malposition (asynclitism, deflexion) that historically have been addressed with the use of obstetric forceps. VE delivery in these circumstances requires a very experienced and skilled operator.

Further selection criteria

Birthweight influences the consideration of VE. Low birthweight or prematurity are contraindications to the use of VE due to concerns about fetal/neonatal bleeding. Large fetuses will have issues with cephalopelvic disproportion, thus increasing the risk for 2 disorders: shoulder dystocia and fetal cranial bleeding.

Cranial bleeding, both intracranial and extracranial, can result in serious neonatal morbidity and mortality. Bleeding may occur spontaneously or with the use of VE. In using VE, force is transmitted to the fetal scalp. The scalp then has the tendency to pull on its contents and attachments—skull bones, brain, fluids, etc. The scalp attachments include vessels at right angles to the scalp, which may be traumatized or torn by the pulling force. This may lead to subgaleal hemorrhage, a collection of blood in the large potential space below the scalp and above the aponeurosis. Enough force may be generated to deform the intracranial contents and cause intracranial bleeding.

The likelihood of success with VE varies depending on maternal anatomy, the position of the fetal head, gestational age, and the presence or absence of gestational diabetes (TABLE 2).

Delivery by VE: Main considerations

After determining that a candidate is suitable for VE and obtaining informed consent, consider key operative factors:

- choice of extraction cup

- adequate anesthesia

- careful maternal positioning

- maternal bladder emptying

- review of fetal status.

Two major cup types are available: rigid and flexible.

Rigid plastic cup. This design is similar to the metal cup used by Malmström and attaches to the scalp via chignon formation. A variation of the rigid cup is the mityvac “M” that mimics the Malmström design but incorporates a semiflexible handle to facilitate proper cup placement and aid in the direction of pulling force.

Flexible cup. This type of cup flattens against the scalp with vacuum and may result in less minor scalp trauma than the rigid cup.

Greater force can be employed with rigid cup designs than with flexible cups, which can increase the chances of a successful delivery when the fetus is in the occiput posterior (OP) position. Flexible designs tend to cause less damage to the scalp than the rigid cup but are reported to have a higher failure rate.

Cardinal rule of any procedure. Prior to cup placement, remember this rule: abandon the procedure if it proves too difficult. Most deliveries will occur with 3 or 4 pulls.3 Difficulties include:

- failure to gain station with the initial pull

- repetitive cup pop-offs (3 or more)

- an excessive duration of the procedure (>10 minutes).

Less than optimal placement of the vacuum extractor will increase the risk of scalp trauma, particularly in nulliparous women.3

If the procedure is unsuccessful, the resulting options include cesarean delivery and expectant management.

Tip. Use both hands during the pull to more reliably detect a problem with cup attachment, thereby minimizing the possibility of detachment and subsequent scalp trauma (FIGURE).

Key points of technique

Perform a careful and thorough pelvic examination to determine fetal station, position, attitude, and synclitism.

The optimal cup placement is 2- to 3-cm proximal to the posterior fontanel or, alternatively, 5- to 6-cm distal to the anterior fontanel, assuming the fetal head is properly flexed.4 The correct point of flexion will result in the smallest diameter of the fetal head presenting to the birth canal and should minimize the force necessary to achieve delivery.

Use minimal vacuum to attach the cup to the fetal head. As the subsequent contraction develops, apply full vacuum with the hand device. Encourage maternal expulsive effort and use traction only in concert with pushing efforts. Three pushes facilitated with pulling may be achieved during a single contraction. Failure to bring about descent with the initial pull indicates potential failure with this approach and, in the absence of technical reasons for the failure, merits serious consideration of abandoning the procedure (TABLE 3).

In the event of failed delivery with VE, it is important to recognize that you should not make a second attempt with another instrument; the chance of success is low and the risk of injury is significantly increased.5

Carefully document the decision for VE and its implementation

The medical record is the most important witness to the event. Clearly record the following items, preferably as close in time to the decision/event as possible:

- the indication for the procedure

- the antecedent labor course

- maternal anesthesia

- personnel present

- instruments employed

- position and station of the fetal head

- force and duration of traction

- nature of the attempt

- immediate condition of the neonate, and any resuscitative efforts.

Closing reminders and advice

In preparing to discuss the patient’s preferences for delivery, understand clearly the risks and benefits of VE and develop a comfortable approach to sharing this information with your patient and her family. Also, if VE is selected, consider performing the procedure in the cesarean delivery room. This will serve to remind you to be mindful to abandon the procedure, if need be, at an appropriate point.

CASE: Resolved