User login

Nitrous oxide returns for labor pain management

SAN FRANCISCO – For much of the past decade, most pregnant women in the United States have not had access to nitrous oxide for analgesia during labor because the only company that sold a nitrous oxide machine for obstetrics in this country stopped making it.

This year, though, "laughing gas" for labor pain is back.

The Nitronox system delivers a fixed mixture of 50% oxygen and 50% nitrous oxide that is safe, effective, inexpensive, simple, and popular with many laboring women, said Judith T. Bishop, C.N.M., M.P.H. Physician supervision is not needed for its use, she added at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Other nitrous oxide systems commonly are used for labor analgesia in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Scandinavia, and are available in Japan and Israel, but the gas has never caught on extensively in the United States for obstetrics. "I’ve been doing kind of a road show for nitrous oxide for about 7 years now," said Ms. Bishop, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive sciences at the university. "Ironically, during the entire period that I’ve been enthusiastically sharing my 20 years of experience with nitrous oxide use at UCSF, the nitrous oxide equipment appropriate for use in labor has been unobtainable" in the United States.

Michael Civitello, a salesman for the company that makes the Nitronox system, said the equipment went out of production during changes involving corporate mergers, not for reasons related to the product itself. Parker Hannifin Corporation’s Porter Instrument Division decided to return Nitronox to the market when it realized it still had a sales niche and advocates such as Ms. Bishop built increased interest in its use, he said in an interview at the company’s booth at the meeting. The new system costs approximately $5,000.

Perhaps 20-30 more hospitals and birth centers are expected to be offering nitrous oxide for labor by the end of this year, predicted Ms. Bishop and Mr. Civitello.

Women in labor at UCSF have been offered nitrous oxide for more than 30 years with no break in service because the gas delivery systems were built into the hospital, and are being built into a new UCSF hospital that’s under construction. Ms. Bishop searched and was able to find only three other U.S. hospitals with the ability to offer nitrous oxide during labor: the University of Washington, Seattle ("although they had largely forgotten about it," she said); a hospital in Lewiston, Idaho; and Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., which got tired of waiting for a nitrous oxide machine to return to the market and bought two used machines on eBay in 2011, Ms. Bishop said.

Data from Vanderbilt from June 2011 to May 2013 show an epidural rate of 40% in its midwifery service, compared with approximately 85% in the rest of the university practice, she said. Twenty percent of women in labor initiated nitrous oxide, and approximately 45% of those converted to epidural analgesia.

Data from 5,987 term singleton pregnancies at UCSF during 2007-2011 show an epidural rate of 76%. Nitrous oxide analgesia was started in 14% of deliveries, 41% of which converted to epidural analgesia.

Those numbers do not include other uses for nitrous oxide on labor and delivery units, she added, including analgesia for women experiencing laceration repair, retained placenta, Foley balloon placement, vaginal exams, and blood draws or IV placement.

For labor, nitrous oxide is an adjunct for pain relief and is not meant to replace other analgesia alternatives, Ms. Bishop said. Its use may allow the woman to delay or avoid using narcotics or epidural anesthesia. Nitrous oxide may be especially useful for women who want an epidural but can’t have one because they arrived at the hospital too late, they have a contraindication such as low platelet levels, or an anesthesiologist is unavailable to administer an epidural.

Another good use of nitrous oxide is for teenage mothers who are "out of control and can’t handle a needle in the back" for epidural analgesia, added Tekoa L. King, C.N.M., M.P.H., also of UCSF.

"There’s an antianxiety effect as well as an analgesic effect," Ms. Bishop said.

Data suggest that about half of women find nitrous oxide to be effective analgesia, better than the satisfaction rate for opioids in labor. That’s "no surprise," because opioids are not very effective in labor, she said. "Bathtubs are rated much more highly than opioids."

Women who report being satisfied with nitrous oxide may not show a decrease in pain scores, she added. With nitrous oxide, they say, "It still hurts, but I don’t care."

Inhaling the gas typically provides some degree of pain relief in less than a minute, and the effect dissipates after another breath or two. Since the first study of its use in labor in 1880, nitrous oxide has proved to be safe, Ms. Bishop said. It does not build up in the mother or fetus, and does not seem to affect contractions, labor progression, or the ability to push. It can be used through the second stage of labor, and there’s no evidence that it affects newborns or breastfeeding.

"You can’t kill somebody with 50/50 nitrous oxide and oxygen," she said.

In the United States, the woman initiates and controls the gas flow through a mask, with the negative pressure from inhalation opening a demand valve that stops gas flow when inhalation ceases. Excess nitrous oxide is scavenged out by suction. It’s meant for intermittent, not continuous, use.

Dosimeter badges worn by obstetrics nurses at UCSF consistently show that staff exposure to nitrous oxide is less than 2 parts per million in an 8-hour period, far below the 25-ppm limit set by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

It’s important to counsel family members who are trying to be "helpful" that only the woman should hold the mask to her face so that she controls the gas flow. Not all women find it helpful, and some may experience dizziness, drowsiness, or nausea, although those effects usually occur with higher doses of nitrous oxide, not the 50/50 blend with oxygen, Ms. Bishop said.

Usually, the nitrous oxide is more effective if the woman breathes it just before a contraction starts instead of waiting for a contraction, but each woman will find what works for them.

Nitrous oxide use at UCSF increased by 50% after the university expanded the privileges of certified nurse-midwives in 2007 to include initiation of the gas mixture, instead of having to call an anesthesia resident. Now the university is moving toward a standing order allowing registered nurses to initiate nitrous oxide use, similar to a standing order for fentanyl initiation. "I think that’s going to be a huge improvement," Ms. Bishop said.

Ms. Bishop reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – For much of the past decade, most pregnant women in the United States have not had access to nitrous oxide for analgesia during labor because the only company that sold a nitrous oxide machine for obstetrics in this country stopped making it.

This year, though, "laughing gas" for labor pain is back.

The Nitronox system delivers a fixed mixture of 50% oxygen and 50% nitrous oxide that is safe, effective, inexpensive, simple, and popular with many laboring women, said Judith T. Bishop, C.N.M., M.P.H. Physician supervision is not needed for its use, she added at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Other nitrous oxide systems commonly are used for labor analgesia in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Scandinavia, and are available in Japan and Israel, but the gas has never caught on extensively in the United States for obstetrics. "I’ve been doing kind of a road show for nitrous oxide for about 7 years now," said Ms. Bishop, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive sciences at the university. "Ironically, during the entire period that I’ve been enthusiastically sharing my 20 years of experience with nitrous oxide use at UCSF, the nitrous oxide equipment appropriate for use in labor has been unobtainable" in the United States.

Michael Civitello, a salesman for the company that makes the Nitronox system, said the equipment went out of production during changes involving corporate mergers, not for reasons related to the product itself. Parker Hannifin Corporation’s Porter Instrument Division decided to return Nitronox to the market when it realized it still had a sales niche and advocates such as Ms. Bishop built increased interest in its use, he said in an interview at the company’s booth at the meeting. The new system costs approximately $5,000.

Perhaps 20-30 more hospitals and birth centers are expected to be offering nitrous oxide for labor by the end of this year, predicted Ms. Bishop and Mr. Civitello.

Women in labor at UCSF have been offered nitrous oxide for more than 30 years with no break in service because the gas delivery systems were built into the hospital, and are being built into a new UCSF hospital that’s under construction. Ms. Bishop searched and was able to find only three other U.S. hospitals with the ability to offer nitrous oxide during labor: the University of Washington, Seattle ("although they had largely forgotten about it," she said); a hospital in Lewiston, Idaho; and Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., which got tired of waiting for a nitrous oxide machine to return to the market and bought two used machines on eBay in 2011, Ms. Bishop said.

Data from Vanderbilt from June 2011 to May 2013 show an epidural rate of 40% in its midwifery service, compared with approximately 85% in the rest of the university practice, she said. Twenty percent of women in labor initiated nitrous oxide, and approximately 45% of those converted to epidural analgesia.

Data from 5,987 term singleton pregnancies at UCSF during 2007-2011 show an epidural rate of 76%. Nitrous oxide analgesia was started in 14% of deliveries, 41% of which converted to epidural analgesia.

Those numbers do not include other uses for nitrous oxide on labor and delivery units, she added, including analgesia for women experiencing laceration repair, retained placenta, Foley balloon placement, vaginal exams, and blood draws or IV placement.

For labor, nitrous oxide is an adjunct for pain relief and is not meant to replace other analgesia alternatives, Ms. Bishop said. Its use may allow the woman to delay or avoid using narcotics or epidural anesthesia. Nitrous oxide may be especially useful for women who want an epidural but can’t have one because they arrived at the hospital too late, they have a contraindication such as low platelet levels, or an anesthesiologist is unavailable to administer an epidural.

Another good use of nitrous oxide is for teenage mothers who are "out of control and can’t handle a needle in the back" for epidural analgesia, added Tekoa L. King, C.N.M., M.P.H., also of UCSF.

"There’s an antianxiety effect as well as an analgesic effect," Ms. Bishop said.

Data suggest that about half of women find nitrous oxide to be effective analgesia, better than the satisfaction rate for opioids in labor. That’s "no surprise," because opioids are not very effective in labor, she said. "Bathtubs are rated much more highly than opioids."

Women who report being satisfied with nitrous oxide may not show a decrease in pain scores, she added. With nitrous oxide, they say, "It still hurts, but I don’t care."

Inhaling the gas typically provides some degree of pain relief in less than a minute, and the effect dissipates after another breath or two. Since the first study of its use in labor in 1880, nitrous oxide has proved to be safe, Ms. Bishop said. It does not build up in the mother or fetus, and does not seem to affect contractions, labor progression, or the ability to push. It can be used through the second stage of labor, and there’s no evidence that it affects newborns or breastfeeding.

"You can’t kill somebody with 50/50 nitrous oxide and oxygen," she said.

In the United States, the woman initiates and controls the gas flow through a mask, with the negative pressure from inhalation opening a demand valve that stops gas flow when inhalation ceases. Excess nitrous oxide is scavenged out by suction. It’s meant for intermittent, not continuous, use.

Dosimeter badges worn by obstetrics nurses at UCSF consistently show that staff exposure to nitrous oxide is less than 2 parts per million in an 8-hour period, far below the 25-ppm limit set by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

It’s important to counsel family members who are trying to be "helpful" that only the woman should hold the mask to her face so that she controls the gas flow. Not all women find it helpful, and some may experience dizziness, drowsiness, or nausea, although those effects usually occur with higher doses of nitrous oxide, not the 50/50 blend with oxygen, Ms. Bishop said.

Usually, the nitrous oxide is more effective if the woman breathes it just before a contraction starts instead of waiting for a contraction, but each woman will find what works for them.

Nitrous oxide use at UCSF increased by 50% after the university expanded the privileges of certified nurse-midwives in 2007 to include initiation of the gas mixture, instead of having to call an anesthesia resident. Now the university is moving toward a standing order allowing registered nurses to initiate nitrous oxide use, similar to a standing order for fentanyl initiation. "I think that’s going to be a huge improvement," Ms. Bishop said.

Ms. Bishop reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – For much of the past decade, most pregnant women in the United States have not had access to nitrous oxide for analgesia during labor because the only company that sold a nitrous oxide machine for obstetrics in this country stopped making it.

This year, though, "laughing gas" for labor pain is back.

The Nitronox system delivers a fixed mixture of 50% oxygen and 50% nitrous oxide that is safe, effective, inexpensive, simple, and popular with many laboring women, said Judith T. Bishop, C.N.M., M.P.H. Physician supervision is not needed for its use, she added at a meeting on antepartum and intrapartum management sponsored by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

Other nitrous oxide systems commonly are used for labor analgesia in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Scandinavia, and are available in Japan and Israel, but the gas has never caught on extensively in the United States for obstetrics. "I’ve been doing kind of a road show for nitrous oxide for about 7 years now," said Ms. Bishop, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and reproductive sciences at the university. "Ironically, during the entire period that I’ve been enthusiastically sharing my 20 years of experience with nitrous oxide use at UCSF, the nitrous oxide equipment appropriate for use in labor has been unobtainable" in the United States.

Michael Civitello, a salesman for the company that makes the Nitronox system, said the equipment went out of production during changes involving corporate mergers, not for reasons related to the product itself. Parker Hannifin Corporation’s Porter Instrument Division decided to return Nitronox to the market when it realized it still had a sales niche and advocates such as Ms. Bishop built increased interest in its use, he said in an interview at the company’s booth at the meeting. The new system costs approximately $5,000.

Perhaps 20-30 more hospitals and birth centers are expected to be offering nitrous oxide for labor by the end of this year, predicted Ms. Bishop and Mr. Civitello.

Women in labor at UCSF have been offered nitrous oxide for more than 30 years with no break in service because the gas delivery systems were built into the hospital, and are being built into a new UCSF hospital that’s under construction. Ms. Bishop searched and was able to find only three other U.S. hospitals with the ability to offer nitrous oxide during labor: the University of Washington, Seattle ("although they had largely forgotten about it," she said); a hospital in Lewiston, Idaho; and Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., which got tired of waiting for a nitrous oxide machine to return to the market and bought two used machines on eBay in 2011, Ms. Bishop said.

Data from Vanderbilt from June 2011 to May 2013 show an epidural rate of 40% in its midwifery service, compared with approximately 85% in the rest of the university practice, she said. Twenty percent of women in labor initiated nitrous oxide, and approximately 45% of those converted to epidural analgesia.

Data from 5,987 term singleton pregnancies at UCSF during 2007-2011 show an epidural rate of 76%. Nitrous oxide analgesia was started in 14% of deliveries, 41% of which converted to epidural analgesia.

Those numbers do not include other uses for nitrous oxide on labor and delivery units, she added, including analgesia for women experiencing laceration repair, retained placenta, Foley balloon placement, vaginal exams, and blood draws or IV placement.

For labor, nitrous oxide is an adjunct for pain relief and is not meant to replace other analgesia alternatives, Ms. Bishop said. Its use may allow the woman to delay or avoid using narcotics or epidural anesthesia. Nitrous oxide may be especially useful for women who want an epidural but can’t have one because they arrived at the hospital too late, they have a contraindication such as low platelet levels, or an anesthesiologist is unavailable to administer an epidural.

Another good use of nitrous oxide is for teenage mothers who are "out of control and can’t handle a needle in the back" for epidural analgesia, added Tekoa L. King, C.N.M., M.P.H., also of UCSF.

"There’s an antianxiety effect as well as an analgesic effect," Ms. Bishop said.

Data suggest that about half of women find nitrous oxide to be effective analgesia, better than the satisfaction rate for opioids in labor. That’s "no surprise," because opioids are not very effective in labor, she said. "Bathtubs are rated much more highly than opioids."

Women who report being satisfied with nitrous oxide may not show a decrease in pain scores, she added. With nitrous oxide, they say, "It still hurts, but I don’t care."

Inhaling the gas typically provides some degree of pain relief in less than a minute, and the effect dissipates after another breath or two. Since the first study of its use in labor in 1880, nitrous oxide has proved to be safe, Ms. Bishop said. It does not build up in the mother or fetus, and does not seem to affect contractions, labor progression, or the ability to push. It can be used through the second stage of labor, and there’s no evidence that it affects newborns or breastfeeding.

"You can’t kill somebody with 50/50 nitrous oxide and oxygen," she said.

In the United States, the woman initiates and controls the gas flow through a mask, with the negative pressure from inhalation opening a demand valve that stops gas flow when inhalation ceases. Excess nitrous oxide is scavenged out by suction. It’s meant for intermittent, not continuous, use.

Dosimeter badges worn by obstetrics nurses at UCSF consistently show that staff exposure to nitrous oxide is less than 2 parts per million in an 8-hour period, far below the 25-ppm limit set by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

It’s important to counsel family members who are trying to be "helpful" that only the woman should hold the mask to her face so that she controls the gas flow. Not all women find it helpful, and some may experience dizziness, drowsiness, or nausea, although those effects usually occur with higher doses of nitrous oxide, not the 50/50 blend with oxygen, Ms. Bishop said.

Usually, the nitrous oxide is more effective if the woman breathes it just before a contraction starts instead of waiting for a contraction, but each woman will find what works for them.

Nitrous oxide use at UCSF increased by 50% after the university expanded the privileges of certified nurse-midwives in 2007 to include initiation of the gas mixture, instead of having to call an anesthesia resident. Now the university is moving toward a standing order allowing registered nurses to initiate nitrous oxide use, similar to a standing order for fentanyl initiation. "I think that’s going to be a huge improvement," Ms. Bishop said.

Ms. Bishop reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON ANTEPARTUM AND INTRAPARTUM MANAGEMENT

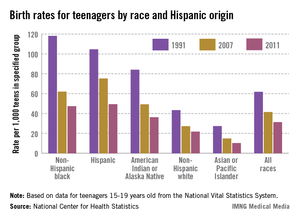

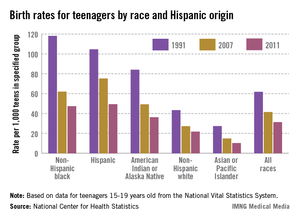

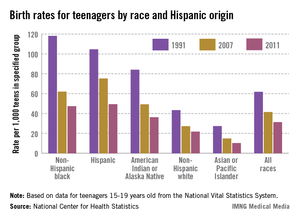

Teen birth rate down almost 50% since 1991

The birth rate among teenagers in the United States dropped by nearly half from 1991 to 2011, with declines seen among all of the largest population groups, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

The birth rate for women aged 15-19 years was 31.3 per 1,000 – a record low – in 2011, down just over 49% from the rate of 61.8 per 1,000 teenagers in 1991. Childbearing fell by 50% or more for non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska native teenagers over that time period, and dropped at least 60% for non-Hispanic black and Asian/Pacific Islander teens, the NCHS said.

Data from the National Vital Statistics System’s Natality Date File, which includes information on all births in the United States, show that a brief increase in births occurred among teenagers aged 15-19 years in 2006 and 2007. Since then, Hispanic teenagers have had the largest decline (34%), followed by non-Hispanic blacks (24%) and non-Hispanic whites (20%).

The declines in the teen birth rate over the last two decades "are sustained, widespread, and broad-based," the NCHS said, noting that "3.6 million more births to teenagers would have occurred from 1992 through 2011" if the rates "had remained at their 1991 levels."

The birth rate among teenagers in the United States dropped by nearly half from 1991 to 2011, with declines seen among all of the largest population groups, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

The birth rate for women aged 15-19 years was 31.3 per 1,000 – a record low – in 2011, down just over 49% from the rate of 61.8 per 1,000 teenagers in 1991. Childbearing fell by 50% or more for non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska native teenagers over that time period, and dropped at least 60% for non-Hispanic black and Asian/Pacific Islander teens, the NCHS said.

Data from the National Vital Statistics System’s Natality Date File, which includes information on all births in the United States, show that a brief increase in births occurred among teenagers aged 15-19 years in 2006 and 2007. Since then, Hispanic teenagers have had the largest decline (34%), followed by non-Hispanic blacks (24%) and non-Hispanic whites (20%).

The declines in the teen birth rate over the last two decades "are sustained, widespread, and broad-based," the NCHS said, noting that "3.6 million more births to teenagers would have occurred from 1992 through 2011" if the rates "had remained at their 1991 levels."

The birth rate among teenagers in the United States dropped by nearly half from 1991 to 2011, with declines seen among all of the largest population groups, the National Center for Health Statistics reported.

The birth rate for women aged 15-19 years was 31.3 per 1,000 – a record low – in 2011, down just over 49% from the rate of 61.8 per 1,000 teenagers in 1991. Childbearing fell by 50% or more for non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and American Indian/Alaska native teenagers over that time period, and dropped at least 60% for non-Hispanic black and Asian/Pacific Islander teens, the NCHS said.

Data from the National Vital Statistics System’s Natality Date File, which includes information on all births in the United States, show that a brief increase in births occurred among teenagers aged 15-19 years in 2006 and 2007. Since then, Hispanic teenagers have had the largest decline (34%), followed by non-Hispanic blacks (24%) and non-Hispanic whites (20%).

The declines in the teen birth rate over the last two decades "are sustained, widespread, and broad-based," the NCHS said, noting that "3.6 million more births to teenagers would have occurred from 1992 through 2011" if the rates "had remained at their 1991 levels."

Noninvasive prenatal DNA testing: A survey of who is using it, and how

FDA warns about magnesium sulfate effects on newborns

Magnesium sulfate should not be used for more than 5-7 days in pregnant women in preterm labor, because in utero exposure may lead to hypocalcemia and an increased risk of osteopenia and bone fractures in newborns, the Food and Drug Administration announced May 30.

"The shortest duration of treatment that can result in harm to the baby is not known," the FDA stated.

The warning is based on epidemiologic studies that were mostly retrospective chart reviews, as well as 18 cases of newborns with skeletal anomalies whose mothers had been treated with magnesium sulfate for tocolysis. The cases had been reported to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) and were in the medical literature.

In these cases, exposure ranged from 8-12 weeks (average was almost 10 weeks), for an estimated average total maternal dose of 3,700 grams.

The newborns developed osteopenia-related skeletal anomalies, and some had multiple fractures of the ribs and long bones. The osteopenia and fractures were transient and had resolved in cases where the outcome was reported, according to the FDA.

Based on cases in the literature, "it is plausible that bone abnormalities in neonates are associated with prolonged in utero exposure to magnesium sulfate," since hypermagnesemia can cause hypocalcemia in the developing fetus, the FDA concluded.

Dr. Jeffrey Ecker, a high-risk obstetrician at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston, said that this warning should not have an impact on practice because the length of exposure and maternal dose of magnesium sulfate cited in the FDA's statement are not recommended. The warning refers to cases of adverse outcomes in which magnesium sulfate was used for weeks at a time, which he said "would be unusual."

Magnesium sulfate is currently used to reduce the risk of cerebral palsy when premature delivery is anticipated, particularly at less than 32 weeks, and to reduce the risk of seizures in women with preeclampsia, two indications where there is good evidence that the use of magnesium sulfate improves outcomes, he noted in an interview.

There is much less evidence that it improves outcomes for the third use, as tocolysis, to delay delivery for 48 hours to allow for administration of steroids in women in preterm labor, said Dr. Ecker, also director of the maternal Fetal Medicine Fellowship at MGH and vice-chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' committee on obstetric practice. "But all three of those uses focus on very short term periods of exposure," he emphasized.*

The FDA is switching magnesium sulfate from a pregnancy category A (drugs for which adequate and well-controlled studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in the first trimester, and no evidence of risk in later trimesters) to pregnancy category D (drugs for which there is evidence of human fetal risks, but also potential benefits in pregnant women that may be acceptable in certain situations, despite the risks).

In addition to the new pregnancy category, the label for magnesium sulfate injection USP 50% will also have a new warning about these risks when administered for more than 5-7 days. There will be a new "labor and delivery" section pointing out that magnesium sulfate is not approved for treatment of preterm labor, the safety and efficacy of use for this indication "are not established," and "when used in pregnant women for conditions other than its approved indication, magnesium sulfate injection should be administered only by trained obstetrical personnel in a hospital setting with appropriate obstetrical care facilities."

Magnesium sulfate is FDA approved to prevent seizures in preeclampsia.

Serious adverse events associated with this drug should be reported to the FDA at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

* Updated 6/5/2013

Magnesium sulfate should not be used for more than 5-7 days in pregnant women in preterm labor, because in utero exposure may lead to hypocalcemia and an increased risk of osteopenia and bone fractures in newborns, the Food and Drug Administration announced May 30.

"The shortest duration of treatment that can result in harm to the baby is not known," the FDA stated.

The warning is based on epidemiologic studies that were mostly retrospective chart reviews, as well as 18 cases of newborns with skeletal anomalies whose mothers had been treated with magnesium sulfate for tocolysis. The cases had been reported to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) and were in the medical literature.

In these cases, exposure ranged from 8-12 weeks (average was almost 10 weeks), for an estimated average total maternal dose of 3,700 grams.

The newborns developed osteopenia-related skeletal anomalies, and some had multiple fractures of the ribs and long bones. The osteopenia and fractures were transient and had resolved in cases where the outcome was reported, according to the FDA.

Based on cases in the literature, "it is plausible that bone abnormalities in neonates are associated with prolonged in utero exposure to magnesium sulfate," since hypermagnesemia can cause hypocalcemia in the developing fetus, the FDA concluded.

Dr. Jeffrey Ecker, a high-risk obstetrician at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston, said that this warning should not have an impact on practice because the length of exposure and maternal dose of magnesium sulfate cited in the FDA's statement are not recommended. The warning refers to cases of adverse outcomes in which magnesium sulfate was used for weeks at a time, which he said "would be unusual."

Magnesium sulfate is currently used to reduce the risk of cerebral palsy when premature delivery is anticipated, particularly at less than 32 weeks, and to reduce the risk of seizures in women with preeclampsia, two indications where there is good evidence that the use of magnesium sulfate improves outcomes, he noted in an interview.

There is much less evidence that it improves outcomes for the third use, as tocolysis, to delay delivery for 48 hours to allow for administration of steroids in women in preterm labor, said Dr. Ecker, also director of the maternal Fetal Medicine Fellowship at MGH and vice-chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' committee on obstetric practice. "But all three of those uses focus on very short term periods of exposure," he emphasized.*

The FDA is switching magnesium sulfate from a pregnancy category A (drugs for which adequate and well-controlled studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in the first trimester, and no evidence of risk in later trimesters) to pregnancy category D (drugs for which there is evidence of human fetal risks, but also potential benefits in pregnant women that may be acceptable in certain situations, despite the risks).

In addition to the new pregnancy category, the label for magnesium sulfate injection USP 50% will also have a new warning about these risks when administered for more than 5-7 days. There will be a new "labor and delivery" section pointing out that magnesium sulfate is not approved for treatment of preterm labor, the safety and efficacy of use for this indication "are not established," and "when used in pregnant women for conditions other than its approved indication, magnesium sulfate injection should be administered only by trained obstetrical personnel in a hospital setting with appropriate obstetrical care facilities."

Magnesium sulfate is FDA approved to prevent seizures in preeclampsia.

Serious adverse events associated with this drug should be reported to the FDA at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

* Updated 6/5/2013

Magnesium sulfate should not be used for more than 5-7 days in pregnant women in preterm labor, because in utero exposure may lead to hypocalcemia and an increased risk of osteopenia and bone fractures in newborns, the Food and Drug Administration announced May 30.

"The shortest duration of treatment that can result in harm to the baby is not known," the FDA stated.

The warning is based on epidemiologic studies that were mostly retrospective chart reviews, as well as 18 cases of newborns with skeletal anomalies whose mothers had been treated with magnesium sulfate for tocolysis. The cases had been reported to the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) and were in the medical literature.

In these cases, exposure ranged from 8-12 weeks (average was almost 10 weeks), for an estimated average total maternal dose of 3,700 grams.

The newborns developed osteopenia-related skeletal anomalies, and some had multiple fractures of the ribs and long bones. The osteopenia and fractures were transient and had resolved in cases where the outcome was reported, according to the FDA.

Based on cases in the literature, "it is plausible that bone abnormalities in neonates are associated with prolonged in utero exposure to magnesium sulfate," since hypermagnesemia can cause hypocalcemia in the developing fetus, the FDA concluded.

Dr. Jeffrey Ecker, a high-risk obstetrician at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Boston, said that this warning should not have an impact on practice because the length of exposure and maternal dose of magnesium sulfate cited in the FDA's statement are not recommended. The warning refers to cases of adverse outcomes in which magnesium sulfate was used for weeks at a time, which he said "would be unusual."

Magnesium sulfate is currently used to reduce the risk of cerebral palsy when premature delivery is anticipated, particularly at less than 32 weeks, and to reduce the risk of seizures in women with preeclampsia, two indications where there is good evidence that the use of magnesium sulfate improves outcomes, he noted in an interview.

There is much less evidence that it improves outcomes for the third use, as tocolysis, to delay delivery for 48 hours to allow for administration of steroids in women in preterm labor, said Dr. Ecker, also director of the maternal Fetal Medicine Fellowship at MGH and vice-chair of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' committee on obstetric practice. "But all three of those uses focus on very short term periods of exposure," he emphasized.*

The FDA is switching magnesium sulfate from a pregnancy category A (drugs for which adequate and well-controlled studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in the first trimester, and no evidence of risk in later trimesters) to pregnancy category D (drugs for which there is evidence of human fetal risks, but also potential benefits in pregnant women that may be acceptable in certain situations, despite the risks).

In addition to the new pregnancy category, the label for magnesium sulfate injection USP 50% will also have a new warning about these risks when administered for more than 5-7 days. There will be a new "labor and delivery" section pointing out that magnesium sulfate is not approved for treatment of preterm labor, the safety and efficacy of use for this indication "are not established," and "when used in pregnant women for conditions other than its approved indication, magnesium sulfate injection should be administered only by trained obstetrical personnel in a hospital setting with appropriate obstetrical care facilities."

Magnesium sulfate is FDA approved to prevent seizures in preeclampsia.

Serious adverse events associated with this drug should be reported to the FDA at 800-332-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch.

* Updated 6/5/2013

Tdap vaccine during pregnancy bests 'postpartum cocooning' approach

Vaccinating pregnant women to protect their newborns from pertussis appears to avert more cases of the disease, hospitalizations, and deaths than does vaccinating mothers immediately post partum, according to a report published online May 27 in Pediatrics.

In a decision-analysis modeling study, vaccination during pregnancy also was found to be more cost-effective than "postpartum cocooning" – a strategy of vaccinating close family contacts, ideally before the infant’s birth, and vaccinating the mother immediately post partum, said Dr. Andrew Terranella and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the cocooning approach in 2005, but "programmatic challenges and institutional hurdles have prevented widespread implementation both in the United States and in other countries." In 2011, ACIP recommended vaccination during the second or third trimester as the preferred strategy. [Editor’s note: The new CDC immunization schedule, released in January 2013, recommends that a dose of the Tdap vaccine be administered to all women during each pregnancy, whether or not she has received the vaccine previously (MMWR 2013;62 [Suppl 1:9-19)].

Dr. Terranella and his colleagues compared the health benefits and costs of three approaches using a cohort model of the 4,131,019 infants born in the United States in 2009 and followed for 1 year.

They calculated the expected number of infant pertussis cases using information from a national database of notifiable diseases, assuming a conservative underreporting rate of 15%. Some studies have documented underreporting rates as high as 50%, they noted.

They calculated the probabilities of hospitalization, respiratory disease, encephalopathy, and death, given an annual rate of 62.6 cases of infant pertussis per 100,000 infants.

The model assumed 72% coverage of vaccination during pregnancy and the same rate of coverage for postpartum vaccination with and without and cocooning vaccination of the father in one grandparent. It also assumed vaccine effectiveness of 85%.

The model further assumed that transfer of maternal antibodies would be 100% and that the rate of infant protection would be 60% for the first 2 months of life. For postpartum vaccination, there would be a 2-week delay in protection of the infant, because it takes that long for sufficient antibodies to form in the mother after the inoculation.

The model showed that with no vaccination, an estimated 3,041 cases of infant pertussis would occur each year, causing 1,463 hospitalizations and 22 deaths. In comparison, postpartum vaccination alone could avert 596 infant cases annually, a 20% reduction from the base case. Postpartum vaccination with cocooning averted 987 cases annually, which represents a 32% reduction in incidence. Vaccination during pregnancy would avert even more – 1,012 cases each year, a 33% reduction in incidence, the investigators said (Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3144]).

Vaccination during pregnancy prevented more infant deaths (a 49% reduction, compared with no vaccination) than did postpartum vaccination with cocooning (a 29% reduction). It also prevented more hospitalizations (a 38% reduction) than did postpartum vaccination with cocooning (a 32% reduction).

In addition, vaccination during pregnancy saved 396 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) annually, compared with 253 QALYs saved with postpartum vaccination with cocooning.

The annual cost of vaccination during pregnancy was estimated to be $171 million, while that of postpartum vaccination with cocooning was estimated to be $513 million. The cost per QALY saved was calculated to be approximately $414,000 for vaccination during pregnancy, compared for both postpartum vaccination ($1.2 million) with cocooning ($2 million).

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess outcomes if a variety of underlying conditions were changed. In particular, changes in vaccine efficacy, vaccine coverage, maternal antibody effect, and potential infant "blunting" of vaccine efficacy (the interference of infant antibodies with the antibody response to the vaccine) were tested.

"Under nearly all scenarios, a pregnancy vaccination strategy would result in fewer overall cases and deaths at lower cost per case averted and per QALY saved," Dr. Terranella and his associates said.

In addition to these advantages, vaccination during pregnancy is more feasible than postpartum vaccination and cocooning because it can easily be administered during existing prenatal care visits. In contrast, reaching postpartum mothers and especially reaching close contacts such as fathers, grandparents, and siblings of the infant is more difficult, the researchers added.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Vaccinating pregnant women to protect their newborns from pertussis appears to avert more cases of the disease, hospitalizations, and deaths than does vaccinating mothers immediately post partum, according to a report published online May 27 in Pediatrics.

In a decision-analysis modeling study, vaccination during pregnancy also was found to be more cost-effective than "postpartum cocooning" – a strategy of vaccinating close family contacts, ideally before the infant’s birth, and vaccinating the mother immediately post partum, said Dr. Andrew Terranella and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the cocooning approach in 2005, but "programmatic challenges and institutional hurdles have prevented widespread implementation both in the United States and in other countries." In 2011, ACIP recommended vaccination during the second or third trimester as the preferred strategy. [Editor’s note: The new CDC immunization schedule, released in January 2013, recommends that a dose of the Tdap vaccine be administered to all women during each pregnancy, whether or not she has received the vaccine previously (MMWR 2013;62 [Suppl 1:9-19)].

Dr. Terranella and his colleagues compared the health benefits and costs of three approaches using a cohort model of the 4,131,019 infants born in the United States in 2009 and followed for 1 year.

They calculated the expected number of infant pertussis cases using information from a national database of notifiable diseases, assuming a conservative underreporting rate of 15%. Some studies have documented underreporting rates as high as 50%, they noted.

They calculated the probabilities of hospitalization, respiratory disease, encephalopathy, and death, given an annual rate of 62.6 cases of infant pertussis per 100,000 infants.

The model assumed 72% coverage of vaccination during pregnancy and the same rate of coverage for postpartum vaccination with and without and cocooning vaccination of the father in one grandparent. It also assumed vaccine effectiveness of 85%.

The model further assumed that transfer of maternal antibodies would be 100% and that the rate of infant protection would be 60% for the first 2 months of life. For postpartum vaccination, there would be a 2-week delay in protection of the infant, because it takes that long for sufficient antibodies to form in the mother after the inoculation.

The model showed that with no vaccination, an estimated 3,041 cases of infant pertussis would occur each year, causing 1,463 hospitalizations and 22 deaths. In comparison, postpartum vaccination alone could avert 596 infant cases annually, a 20% reduction from the base case. Postpartum vaccination with cocooning averted 987 cases annually, which represents a 32% reduction in incidence. Vaccination during pregnancy would avert even more – 1,012 cases each year, a 33% reduction in incidence, the investigators said (Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3144]).

Vaccination during pregnancy prevented more infant deaths (a 49% reduction, compared with no vaccination) than did postpartum vaccination with cocooning (a 29% reduction). It also prevented more hospitalizations (a 38% reduction) than did postpartum vaccination with cocooning (a 32% reduction).

In addition, vaccination during pregnancy saved 396 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) annually, compared with 253 QALYs saved with postpartum vaccination with cocooning.

The annual cost of vaccination during pregnancy was estimated to be $171 million, while that of postpartum vaccination with cocooning was estimated to be $513 million. The cost per QALY saved was calculated to be approximately $414,000 for vaccination during pregnancy, compared for both postpartum vaccination ($1.2 million) with cocooning ($2 million).

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess outcomes if a variety of underlying conditions were changed. In particular, changes in vaccine efficacy, vaccine coverage, maternal antibody effect, and potential infant "blunting" of vaccine efficacy (the interference of infant antibodies with the antibody response to the vaccine) were tested.

"Under nearly all scenarios, a pregnancy vaccination strategy would result in fewer overall cases and deaths at lower cost per case averted and per QALY saved," Dr. Terranella and his associates said.

In addition to these advantages, vaccination during pregnancy is more feasible than postpartum vaccination and cocooning because it can easily be administered during existing prenatal care visits. In contrast, reaching postpartum mothers and especially reaching close contacts such as fathers, grandparents, and siblings of the infant is more difficult, the researchers added.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Vaccinating pregnant women to protect their newborns from pertussis appears to avert more cases of the disease, hospitalizations, and deaths than does vaccinating mothers immediately post partum, according to a report published online May 27 in Pediatrics.

In a decision-analysis modeling study, vaccination during pregnancy also was found to be more cost-effective than "postpartum cocooning" – a strategy of vaccinating close family contacts, ideally before the infant’s birth, and vaccinating the mother immediately post partum, said Dr. Andrew Terranella and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended the cocooning approach in 2005, but "programmatic challenges and institutional hurdles have prevented widespread implementation both in the United States and in other countries." In 2011, ACIP recommended vaccination during the second or third trimester as the preferred strategy. [Editor’s note: The new CDC immunization schedule, released in January 2013, recommends that a dose of the Tdap vaccine be administered to all women during each pregnancy, whether or not she has received the vaccine previously (MMWR 2013;62 [Suppl 1:9-19)].

Dr. Terranella and his colleagues compared the health benefits and costs of three approaches using a cohort model of the 4,131,019 infants born in the United States in 2009 and followed for 1 year.

They calculated the expected number of infant pertussis cases using information from a national database of notifiable diseases, assuming a conservative underreporting rate of 15%. Some studies have documented underreporting rates as high as 50%, they noted.

They calculated the probabilities of hospitalization, respiratory disease, encephalopathy, and death, given an annual rate of 62.6 cases of infant pertussis per 100,000 infants.

The model assumed 72% coverage of vaccination during pregnancy and the same rate of coverage for postpartum vaccination with and without and cocooning vaccination of the father in one grandparent. It also assumed vaccine effectiveness of 85%.

The model further assumed that transfer of maternal antibodies would be 100% and that the rate of infant protection would be 60% for the first 2 months of life. For postpartum vaccination, there would be a 2-week delay in protection of the infant, because it takes that long for sufficient antibodies to form in the mother after the inoculation.

The model showed that with no vaccination, an estimated 3,041 cases of infant pertussis would occur each year, causing 1,463 hospitalizations and 22 deaths. In comparison, postpartum vaccination alone could avert 596 infant cases annually, a 20% reduction from the base case. Postpartum vaccination with cocooning averted 987 cases annually, which represents a 32% reduction in incidence. Vaccination during pregnancy would avert even more – 1,012 cases each year, a 33% reduction in incidence, the investigators said (Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3144]).

Vaccination during pregnancy prevented more infant deaths (a 49% reduction, compared with no vaccination) than did postpartum vaccination with cocooning (a 29% reduction). It also prevented more hospitalizations (a 38% reduction) than did postpartum vaccination with cocooning (a 32% reduction).

In addition, vaccination during pregnancy saved 396 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) annually, compared with 253 QALYs saved with postpartum vaccination with cocooning.

The annual cost of vaccination during pregnancy was estimated to be $171 million, while that of postpartum vaccination with cocooning was estimated to be $513 million. The cost per QALY saved was calculated to be approximately $414,000 for vaccination during pregnancy, compared for both postpartum vaccination ($1.2 million) with cocooning ($2 million).

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to assess outcomes if a variety of underlying conditions were changed. In particular, changes in vaccine efficacy, vaccine coverage, maternal antibody effect, and potential infant "blunting" of vaccine efficacy (the interference of infant antibodies with the antibody response to the vaccine) were tested.

"Under nearly all scenarios, a pregnancy vaccination strategy would result in fewer overall cases and deaths at lower cost per case averted and per QALY saved," Dr. Terranella and his associates said.

In addition to these advantages, vaccination during pregnancy is more feasible than postpartum vaccination and cocooning because it can easily be administered during existing prenatal care visits. In contrast, reaching postpartum mothers and especially reaching close contacts such as fathers, grandparents, and siblings of the infant is more difficult, the researchers added.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Major finding: Vaccination during pregnancy would reduce deaths from infant pertussis by 49%, reduce hospitalizations by 38%, and save 396 QALYs per year, while postpartum vaccination and cocooning would reduce deaths by 29%, reduce hospitalizations by 33%, and save 253 QALYs per year.

Data source: A decision-analysis modeling study using data from the cohort of over 4 million U.S. births in 2009.

Disclosures: No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Prenatal classes influence New Zealand moms' decision to vaccinate

WASHINGTON – New Zealand mothers who attended childbirth classes during pregnancy were 58% less likely to delay their infants’ first-year immunizations than were those who didn’t take the classes, Dr. Cameron Grant said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The findings of his large prospective cohort study show that early engagement with a maternity clinician is important not only for mothers’ health, but for babies’ as well, said Dr. Grant of the University of Auckland (New Zealand).

The data were drawn from "Growing Up in New Zealand," a large, ongoing study of children’s health from birth to age 21 years; Dr. Grant is also the associate director of this project.

The birth cohort is culturally, racially, and economically diverse, and includes about one-third of the New Zealand births that occurred from April 2009 to March 2010. Mothers were contacted during their pregnancy and had face-to-face interviews when the infant was 6 weeks and 9 months old. There were also phone interviews at 16, 24, and 31 months. Four-year interviews started this year.

The immunization study included 6,822 mothers and their 6,846 children. It examined the links between infant immunization and the maternity care provided in the country. Typically, women attend childbirth preparation classes and their prenatal care is provided by a maternity clinician, usually a midwife. After birth, a community nurse provides well-child visits, but the mother and child return to their family doctor for immunizations. The New Zealand infant immunization series consists of the DTaP, hepatitis B/Hib, and conjugate pneumococcal vaccine, which are given at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 5 months. Delayed immunization was considered as not getting the 6-week immunizations by 8 weeks, or not getting the 3- or 5-month immunizations within 30 days of the due dates.

Mothers in the study are a diverse group, with 52% being white, 16% Maori, 14% Pacific Islanders, 14% Asian, and 4% other. Nearly a third was in the country’s lowest socioeconomic group. The pregnancy was the first for 42%.

Immunizations were delayed for 1,353 (20%) of the infants. Immunizations were on time for 88% of the women who attended childbirth classes, compared with 74% of those who did not, translating to a 62% risk reduction (odds ratio, 0.38).

A univariate analysis found several other significant predictors. Having a midwife significantly reduced the risk of delayed immunizations (OR, 0.43), as did going to any of the three infant well child visits (OR, 0.45).

However, after researchers adjusted for maternal ethnicity, age, and household income, only class attendance and well-child visits with a physician remained significantly associated with immunizations. Those who went to the class were 58% less likely to delay immunizations than were those who didn’t go to the class (OR, 0.42), and 24% less likely to delay than were those who had not gone to the class, but said they intended to (OR, 0.76). Women who visited their doctor for all three well-child visits were 55% less likely to delay immunizations (OR, 0.45).

During the discussion, Dr. Simon Hambidge, a professor at the Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, asked if the association could be a proxy for overall engagement with the health care system or an indicator of some more fundamental force influencing the decision to vaccinate.

"I really do think the health care system has a big role on whether immunization occurs or not," Dr. Grant said. "Moms from the poorest households had the highest intention to immunize their children, but the lowest actual immunization timeliness. I think that points to a number of barriers in health care that we should work hard to overcome, rather than just telling women it’s all up to them to get themselves organized and make sure it happens. We just have to make this more available."

The study is sponsored by a number of New Zealand and Pacific Island government agencies. Dr. Grant had no financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – New Zealand mothers who attended childbirth classes during pregnancy were 58% less likely to delay their infants’ first-year immunizations than were those who didn’t take the classes, Dr. Cameron Grant said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The findings of his large prospective cohort study show that early engagement with a maternity clinician is important not only for mothers’ health, but for babies’ as well, said Dr. Grant of the University of Auckland (New Zealand).

The data were drawn from "Growing Up in New Zealand," a large, ongoing study of children’s health from birth to age 21 years; Dr. Grant is also the associate director of this project.

The birth cohort is culturally, racially, and economically diverse, and includes about one-third of the New Zealand births that occurred from April 2009 to March 2010. Mothers were contacted during their pregnancy and had face-to-face interviews when the infant was 6 weeks and 9 months old. There were also phone interviews at 16, 24, and 31 months. Four-year interviews started this year.

The immunization study included 6,822 mothers and their 6,846 children. It examined the links between infant immunization and the maternity care provided in the country. Typically, women attend childbirth preparation classes and their prenatal care is provided by a maternity clinician, usually a midwife. After birth, a community nurse provides well-child visits, but the mother and child return to their family doctor for immunizations. The New Zealand infant immunization series consists of the DTaP, hepatitis B/Hib, and conjugate pneumococcal vaccine, which are given at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 5 months. Delayed immunization was considered as not getting the 6-week immunizations by 8 weeks, or not getting the 3- or 5-month immunizations within 30 days of the due dates.

Mothers in the study are a diverse group, with 52% being white, 16% Maori, 14% Pacific Islanders, 14% Asian, and 4% other. Nearly a third was in the country’s lowest socioeconomic group. The pregnancy was the first for 42%.

Immunizations were delayed for 1,353 (20%) of the infants. Immunizations were on time for 88% of the women who attended childbirth classes, compared with 74% of those who did not, translating to a 62% risk reduction (odds ratio, 0.38).

A univariate analysis found several other significant predictors. Having a midwife significantly reduced the risk of delayed immunizations (OR, 0.43), as did going to any of the three infant well child visits (OR, 0.45).

However, after researchers adjusted for maternal ethnicity, age, and household income, only class attendance and well-child visits with a physician remained significantly associated with immunizations. Those who went to the class were 58% less likely to delay immunizations than were those who didn’t go to the class (OR, 0.42), and 24% less likely to delay than were those who had not gone to the class, but said they intended to (OR, 0.76). Women who visited their doctor for all three well-child visits were 55% less likely to delay immunizations (OR, 0.45).

During the discussion, Dr. Simon Hambidge, a professor at the Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, asked if the association could be a proxy for overall engagement with the health care system or an indicator of some more fundamental force influencing the decision to vaccinate.

"I really do think the health care system has a big role on whether immunization occurs or not," Dr. Grant said. "Moms from the poorest households had the highest intention to immunize their children, but the lowest actual immunization timeliness. I think that points to a number of barriers in health care that we should work hard to overcome, rather than just telling women it’s all up to them to get themselves organized and make sure it happens. We just have to make this more available."

The study is sponsored by a number of New Zealand and Pacific Island government agencies. Dr. Grant had no financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – New Zealand mothers who attended childbirth classes during pregnancy were 58% less likely to delay their infants’ first-year immunizations than were those who didn’t take the classes, Dr. Cameron Grant said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies.

The findings of his large prospective cohort study show that early engagement with a maternity clinician is important not only for mothers’ health, but for babies’ as well, said Dr. Grant of the University of Auckland (New Zealand).

The data were drawn from "Growing Up in New Zealand," a large, ongoing study of children’s health from birth to age 21 years; Dr. Grant is also the associate director of this project.

The birth cohort is culturally, racially, and economically diverse, and includes about one-third of the New Zealand births that occurred from April 2009 to March 2010. Mothers were contacted during their pregnancy and had face-to-face interviews when the infant was 6 weeks and 9 months old. There were also phone interviews at 16, 24, and 31 months. Four-year interviews started this year.

The immunization study included 6,822 mothers and their 6,846 children. It examined the links between infant immunization and the maternity care provided in the country. Typically, women attend childbirth preparation classes and their prenatal care is provided by a maternity clinician, usually a midwife. After birth, a community nurse provides well-child visits, but the mother and child return to their family doctor for immunizations. The New Zealand infant immunization series consists of the DTaP, hepatitis B/Hib, and conjugate pneumococcal vaccine, which are given at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 5 months. Delayed immunization was considered as not getting the 6-week immunizations by 8 weeks, or not getting the 3- or 5-month immunizations within 30 days of the due dates.

Mothers in the study are a diverse group, with 52% being white, 16% Maori, 14% Pacific Islanders, 14% Asian, and 4% other. Nearly a third was in the country’s lowest socioeconomic group. The pregnancy was the first for 42%.

Immunizations were delayed for 1,353 (20%) of the infants. Immunizations were on time for 88% of the women who attended childbirth classes, compared with 74% of those who did not, translating to a 62% risk reduction (odds ratio, 0.38).

A univariate analysis found several other significant predictors. Having a midwife significantly reduced the risk of delayed immunizations (OR, 0.43), as did going to any of the three infant well child visits (OR, 0.45).

However, after researchers adjusted for maternal ethnicity, age, and household income, only class attendance and well-child visits with a physician remained significantly associated with immunizations. Those who went to the class were 58% less likely to delay immunizations than were those who didn’t go to the class (OR, 0.42), and 24% less likely to delay than were those who had not gone to the class, but said they intended to (OR, 0.76). Women who visited their doctor for all three well-child visits were 55% less likely to delay immunizations (OR, 0.45).

During the discussion, Dr. Simon Hambidge, a professor at the Colorado School of Public Health, Denver, asked if the association could be a proxy for overall engagement with the health care system or an indicator of some more fundamental force influencing the decision to vaccinate.

"I really do think the health care system has a big role on whether immunization occurs or not," Dr. Grant said. "Moms from the poorest households had the highest intention to immunize their children, but the lowest actual immunization timeliness. I think that points to a number of barriers in health care that we should work hard to overcome, rather than just telling women it’s all up to them to get themselves organized and make sure it happens. We just have to make this more available."

The study is sponsored by a number of New Zealand and Pacific Island government agencies. Dr. Grant had no financial disclosures.

AT THE PAS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Attending childbirth education classes during pregnancy reduced the risk of delayed infant immunizations by 58%.

Data source: The immunization study is part of "Growing Up in New Zealand," an ongoing birth cohort study of 7,000 children.

Disclosures: The study is sponsored by a number of New Zealand and Pacific Island government agencies. Dr. Grant had no financial disclosures.

Doxylamine-Pyridoxine for NVP

Until the early 1980s, the combination of the antihistamine doxylamine succinate and the vitamin B6 analog pyridoxine hydrochloride was marketed in the United States as Bendectin to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy – the same combination that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April and is being marketed as Diclegis.

Bendectin was taken off the U.S. market, not due to an FDA decision to remove the drug, but because of the lawsuits filed against the manufacturer alleging that the drug had caused birth defects. Despite periodic reaffirmations by the FDA that there was no evidence that it was teratogenic, women in the United States have been left without an FDA-approved drug for morning sickness for over 30 years.

Soon after Bendectin was taken off the market, a study found the rate of hospitalizations for severe morning sickness in the United States increased threefold (Can. J. Public Health 1995;86:66-70).

So clearly, the removal of a drug taken by up to 40% of pregnant women in the United States during the late 1970s was not warranted, and women have suffered as a result. Because it was off-patent, a Canadian company, Duchesnay, began manufacturing the drug and marketed it as Diclectin in Canada, where it remained available and has been widely used, with a solid safety profile and no evidence of an increased risk of congenital malformations/teratogenicity.

Overall, there has been no evidence of an increased malformation risk in over 250,000 women treated during pregnancy – far more than any other drug used in pregnancy. In addition, more studies have confirmed the fetal safety of the combination, including three meta-analyses of studies of over 200,000 women that found no increased risk of congenital malformations in general, or specific malformations in particular, associated with prenatal exposure to Bendectin (Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1988;22:813-24).

Another meta-analysis published in 1994 of 16 cohort and 11 case-control studies found no difference in the risk of birth defects among the babies exposed to Bendectin in the first trimester and those with no such exposure (Teratology 1994;50:27-37).

In another study that followed the neurodevelopment of children whose mothers had called Motherisk about nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) while pregnant, we found no evidence of an adverse effect of Diclectin exposure on neurodevelopment up through age 7 years (J. Pediatr. 2009;155:45-50, 50.e1-2).

The U.S. approval of doxylamine-pyridoxine in April 2013 is a major milestone, particularly because it is indicated for use in pregnancy and the FDA has labeled it a pregnancy category A drug – the strongest evidence of fetal safety. For approval, the FDA required a new phase III placebo-controlled study conducted in the United States. The study, in which I was an investigator, enrolled over 200 adult women at 7-14 weeks’ gestation experiencing NVP, at medical centers in Galveston, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. It found that treatment with the doxylamine-pyridoxine combination was significantly superior at improving symptoms over placebo, and that it improved quality of life, after 2 weeks of treatment. Women on the drug required fewer alternative treatments, more asked to continue treatment than did those on placebo, and they missed less time from work (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203:571.e1-571.e7).

Older antihistamines such as doxylamine tend to cause CNS depression, but in the U.S. study, those who received the active drug did not have more sedation than those on placebo. The experience in Canada has been similar.

After 30 years of experience in Canada, quite a few Canadian physicians give more than the four tablets recommended in the label, which may be necessary to achieve the therapeutic effects for women who have severe symptoms, are overweight, or are obese. In a study, my colleagues and I found no increased risk of malformations or developmental issues associated with prenatal exposure to the higher-than-standard doses, more than four tablets a day (J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001;41:842-5).

We recently published a study showing the benefits of preemptive treatment with Diclectin in women who had experienced severe nausea and vomiting during a previous pregnancy: Those who commenced treatment with Diclectin before symptoms started had significantly fewer cases of moderate to severe NVP than those who started treatment once they started to experience symptoms (Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2013 [doi: 10.1155/2013/809787]).

In summary, the introduction of Diclegis in the United States is a major victory for American women and their health care providers, after being orphaned from this FDA-approved medication for NVP for 30 years.

Dr. Koren is professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto. He heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program. He also holds the Ivey Chair in Molecular Toxicology at the department of medicine, University of Western Ontario, London. Dr. Koren was a principal investigator in the U.S. study that resulted in the approval of Diclegis, marketed by Duchesnay USA, has participated in other studies of Diclectin, and has served as a consultant to Duchesnay. E-mail him at [email protected].

Until the early 1980s, the combination of the antihistamine doxylamine succinate and the vitamin B6 analog pyridoxine hydrochloride was marketed in the United States as Bendectin to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy – the same combination that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April and is being marketed as Diclegis.

Bendectin was taken off the U.S. market, not due to an FDA decision to remove the drug, but because of the lawsuits filed against the manufacturer alleging that the drug had caused birth defects. Despite periodic reaffirmations by the FDA that there was no evidence that it was teratogenic, women in the United States have been left without an FDA-approved drug for morning sickness for over 30 years.

Soon after Bendectin was taken off the market, a study found the rate of hospitalizations for severe morning sickness in the United States increased threefold (Can. J. Public Health 1995;86:66-70).

So clearly, the removal of a drug taken by up to 40% of pregnant women in the United States during the late 1970s was not warranted, and women have suffered as a result. Because it was off-patent, a Canadian company, Duchesnay, began manufacturing the drug and marketed it as Diclectin in Canada, where it remained available and has been widely used, with a solid safety profile and no evidence of an increased risk of congenital malformations/teratogenicity.

Overall, there has been no evidence of an increased malformation risk in over 250,000 women treated during pregnancy – far more than any other drug used in pregnancy. In addition, more studies have confirmed the fetal safety of the combination, including three meta-analyses of studies of over 200,000 women that found no increased risk of congenital malformations in general, or specific malformations in particular, associated with prenatal exposure to Bendectin (Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1988;22:813-24).

Another meta-analysis published in 1994 of 16 cohort and 11 case-control studies found no difference in the risk of birth defects among the babies exposed to Bendectin in the first trimester and those with no such exposure (Teratology 1994;50:27-37).

In another study that followed the neurodevelopment of children whose mothers had called Motherisk about nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) while pregnant, we found no evidence of an adverse effect of Diclectin exposure on neurodevelopment up through age 7 years (J. Pediatr. 2009;155:45-50, 50.e1-2).

The U.S. approval of doxylamine-pyridoxine in April 2013 is a major milestone, particularly because it is indicated for use in pregnancy and the FDA has labeled it a pregnancy category A drug – the strongest evidence of fetal safety. For approval, the FDA required a new phase III placebo-controlled study conducted in the United States. The study, in which I was an investigator, enrolled over 200 adult women at 7-14 weeks’ gestation experiencing NVP, at medical centers in Galveston, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. It found that treatment with the doxylamine-pyridoxine combination was significantly superior at improving symptoms over placebo, and that it improved quality of life, after 2 weeks of treatment. Women on the drug required fewer alternative treatments, more asked to continue treatment than did those on placebo, and they missed less time from work (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203:571.e1-571.e7).

Older antihistamines such as doxylamine tend to cause CNS depression, but in the U.S. study, those who received the active drug did not have more sedation than those on placebo. The experience in Canada has been similar.

After 30 years of experience in Canada, quite a few Canadian physicians give more than the four tablets recommended in the label, which may be necessary to achieve the therapeutic effects for women who have severe symptoms, are overweight, or are obese. In a study, my colleagues and I found no increased risk of malformations or developmental issues associated with prenatal exposure to the higher-than-standard doses, more than four tablets a day (J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001;41:842-5).

We recently published a study showing the benefits of preemptive treatment with Diclectin in women who had experienced severe nausea and vomiting during a previous pregnancy: Those who commenced treatment with Diclectin before symptoms started had significantly fewer cases of moderate to severe NVP than those who started treatment once they started to experience symptoms (Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2013 [doi: 10.1155/2013/809787]).

In summary, the introduction of Diclegis in the United States is a major victory for American women and their health care providers, after being orphaned from this FDA-approved medication for NVP for 30 years.

Dr. Koren is professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto. He heads the Research Leadership for Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, where he is director of the Motherisk Program. He also holds the Ivey Chair in Molecular Toxicology at the department of medicine, University of Western Ontario, London. Dr. Koren was a principal investigator in the U.S. study that resulted in the approval of Diclegis, marketed by Duchesnay USA, has participated in other studies of Diclectin, and has served as a consultant to Duchesnay. E-mail him at [email protected].

Until the early 1980s, the combination of the antihistamine doxylamine succinate and the vitamin B6 analog pyridoxine hydrochloride was marketed in the United States as Bendectin to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy – the same combination that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in April and is being marketed as Diclegis.

Bendectin was taken off the U.S. market, not due to an FDA decision to remove the drug, but because of the lawsuits filed against the manufacturer alleging that the drug had caused birth defects. Despite periodic reaffirmations by the FDA that there was no evidence that it was teratogenic, women in the United States have been left without an FDA-approved drug for morning sickness for over 30 years.

Soon after Bendectin was taken off the market, a study found the rate of hospitalizations for severe morning sickness in the United States increased threefold (Can. J. Public Health 1995;86:66-70).

So clearly, the removal of a drug taken by up to 40% of pregnant women in the United States during the late 1970s was not warranted, and women have suffered as a result. Because it was off-patent, a Canadian company, Duchesnay, began manufacturing the drug and marketed it as Diclectin in Canada, where it remained available and has been widely used, with a solid safety profile and no evidence of an increased risk of congenital malformations/teratogenicity.

Overall, there has been no evidence of an increased malformation risk in over 250,000 women treated during pregnancy – far more than any other drug used in pregnancy. In addition, more studies have confirmed the fetal safety of the combination, including three meta-analyses of studies of over 200,000 women that found no increased risk of congenital malformations in general, or specific malformations in particular, associated with prenatal exposure to Bendectin (Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1988;22:813-24).

Another meta-analysis published in 1994 of 16 cohort and 11 case-control studies found no difference in the risk of birth defects among the babies exposed to Bendectin in the first trimester and those with no such exposure (Teratology 1994;50:27-37).

In another study that followed the neurodevelopment of children whose mothers had called Motherisk about nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP) while pregnant, we found no evidence of an adverse effect of Diclectin exposure on neurodevelopment up through age 7 years (J. Pediatr. 2009;155:45-50, 50.e1-2).

The U.S. approval of doxylamine-pyridoxine in April 2013 is a major milestone, particularly because it is indicated for use in pregnancy and the FDA has labeled it a pregnancy category A drug – the strongest evidence of fetal safety. For approval, the FDA required a new phase III placebo-controlled study conducted in the United States. The study, in which I was an investigator, enrolled over 200 adult women at 7-14 weeks’ gestation experiencing NVP, at medical centers in Galveston, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. It found that treatment with the doxylamine-pyridoxine combination was significantly superior at improving symptoms over placebo, and that it improved quality of life, after 2 weeks of treatment. Women on the drug required fewer alternative treatments, more asked to continue treatment than did those on placebo, and they missed less time from work (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;203:571.e1-571.e7).

Older antihistamines such as doxylamine tend to cause CNS depression, but in the U.S. study, those who received the active drug did not have more sedation than those on placebo. The experience in Canada has been similar.