User login

Can we discern optimal long-term osteoporosis treatment for women?

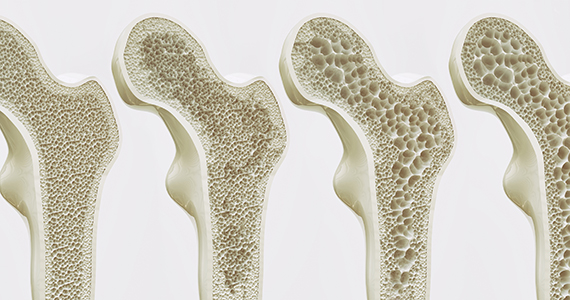

In a recent systematic review, Fink and colleagues attempted to summarize the published evidence of the efficacy and safety of long-term (> 3 years) therapy for osteoporosis.1 Unfortunately, they arrived at very limited and tentative conclusions because, as they point out, of the paucity of such evidence.

Why long-term studies stop short

Only 3 of the several tens of placebo-controlled fracture end-point studies (about 58 trials and observational studies) that Fink and colleagues reviewed evaluated treatment for more than 3 years. The nonavailability of longer-term studies is the direct consequence of a requirement by regulatory agencies for a 3-year fracture end-point study in order to register a new drug for osteoporosis. Hence, longer, placebo-controlled studies do not benefit the industry sponsor, and enrolling patients with osteoporosis or who are at high risk for fracture in any, much less long, placebo-controlled trials is now considered to be unethical.

What the authors did observe

From this limited set of information with which to evaluate, Fink and colleagues observed that long-term therapy with raloxifene reduces the risk of vertebral fractures but is associated with thromboembolic complications. In addition, treatment for more than 3 years with bisphosphonates reduces the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but may increase risk of rare adverse events (including femoral shaft fractures with atypical radiographic features).

The bisphosphonate holiday. The authors refer to the even more limited evidence about the effects of discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy. Unlike the rapid loss of bone mass density (BMD) and fracture protection upon stopping estrogen or denosumab, the offset of these treatment benefits is slower when bisphosphonates are discontinued. This, coupled with concern about increasing risk with long-term bisphosphonate therapy, led to the confusing concept of a “bisphosphonate holiday.” While recommendations to consider temporary discontinuation of bisphosphonates in patients at low risk for fracture have been made by expert panels,2 very little information exists about the benefits/risks of this strategy, how long the treatment interruption should be, or how to decide when and with what to restart therapy. Unfortunately, overall, Fink and colleagues’ observations provide little practical guidance for clinicians.

Continue to: What we can learn from longer term and recent studies of ideal treatment...

What we can learn from longer term and recent studies of ideal treatment

Since we have no “cure” for osteoporosis, and since the benefits of therapy, including protection from fractures, abate upon stopping treatment (as they do when we stop treating hypertension or diabetes), very long term if not lifelong management is required for patients with osteoporosis. Persistent or even greater reduction of fracture risk with treatment up to 10 years, compared with the rate of fracture in the placebo or treated group during the first 3 years of the study, has been observed with zoledronate and denosumab.3-5 Denosumab was not included in the systematic review by Fink and colleagues since the pivotal fracture trial with that agent was placebo-controlled for only 3 years.6

Sequential drug treatment may be best. Fink and colleagues also did not consider new evidence, which suggests that the use of osteoporosis drugs in sequence—rather than a single agent for a long time—may be the most effective management strategy.7,8

More consideration should be given to the use of estrogen and raloxifene in younger postmenopausal women at risk for vertebral but not hip fracture.

Only treat high-risk patients. Using osteoporosis therapies to only treat patients at high risk for fracture will optimize the benefit:risk ratio and cost-effectiveness of therapy.

Bisphosphonate holidays may not be as important as once thought. BMD and fracture risk reduction does not improve after 5 years of bisphosphonate therapy, and longer treatment may increase the risk of atypic

Hip BMD may serve as indicator for treatment decisions. Recent evidence indicating that the change in hip BMD with treatment or the level of hip BMD achieved on treatment correlates with fracture risk reduction may provide a useful clinical target to guide treatment decisions.9,10

Because we have a lack of pristine evidence does not mean that we shouldn’t treat osteoporosis; we have to do the best we can with the limited evidence we have. Therapy must be individualized, for we are not just treating osteoporosis, we are treating patients with osteoporosis.

- Fink HA, MacDonald R, Forte ML, et al. Long-term drug therapy and drug discontinuations and holidays for osteoporosis fracture prevention: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:37-50.

- Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:16-35.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Cauley JA, et al. The effect of 6 versus 9 years of zoledronic acid treatment in osteoporosis: a randomized second extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:934-944.

- Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:513-523.

- Ferrari S, Butler PW, Kendler DL, et al. Further nonvertebral fracture reduction beyond 3 years for up to 10 years of denosumab treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:3450-3461.

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765.

- Cosman F, Nieves JW, Dempster DW. Treatment sequence matters: anabolic and antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:198-202.

- Hanley DA, McClung MR, Davison KS, et al; Writing Group for the Western Osteoporosis Alliance. Western Osteoporosis Alliance Clinical Practice Series: evaluating the balance of benefits and risks of long-term osteoporosis therapies. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e1-862.e7.

- Bouxsein ML, Eastell R, Lui LY, et al; FNIH Bone Quality Project. Change in bone density and reduction in fracture risk: a meta-regression of published trials. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:632-642.

- Ferrari S, Libanati C, Lin CJF, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density T-score and nonvertebral fracture risk over 10 years of denosumab treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:1033-1040.

In a recent systematic review, Fink and colleagues attempted to summarize the published evidence of the efficacy and safety of long-term (> 3 years) therapy for osteoporosis.1 Unfortunately, they arrived at very limited and tentative conclusions because, as they point out, of the paucity of such evidence.

Why long-term studies stop short

Only 3 of the several tens of placebo-controlled fracture end-point studies (about 58 trials and observational studies) that Fink and colleagues reviewed evaluated treatment for more than 3 years. The nonavailability of longer-term studies is the direct consequence of a requirement by regulatory agencies for a 3-year fracture end-point study in order to register a new drug for osteoporosis. Hence, longer, placebo-controlled studies do not benefit the industry sponsor, and enrolling patients with osteoporosis or who are at high risk for fracture in any, much less long, placebo-controlled trials is now considered to be unethical.

What the authors did observe

From this limited set of information with which to evaluate, Fink and colleagues observed that long-term therapy with raloxifene reduces the risk of vertebral fractures but is associated with thromboembolic complications. In addition, treatment for more than 3 years with bisphosphonates reduces the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but may increase risk of rare adverse events (including femoral shaft fractures with atypical radiographic features).

The bisphosphonate holiday. The authors refer to the even more limited evidence about the effects of discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy. Unlike the rapid loss of bone mass density (BMD) and fracture protection upon stopping estrogen or denosumab, the offset of these treatment benefits is slower when bisphosphonates are discontinued. This, coupled with concern about increasing risk with long-term bisphosphonate therapy, led to the confusing concept of a “bisphosphonate holiday.” While recommendations to consider temporary discontinuation of bisphosphonates in patients at low risk for fracture have been made by expert panels,2 very little information exists about the benefits/risks of this strategy, how long the treatment interruption should be, or how to decide when and with what to restart therapy. Unfortunately, overall, Fink and colleagues’ observations provide little practical guidance for clinicians.

Continue to: What we can learn from longer term and recent studies of ideal treatment...

What we can learn from longer term and recent studies of ideal treatment

Since we have no “cure” for osteoporosis, and since the benefits of therapy, including protection from fractures, abate upon stopping treatment (as they do when we stop treating hypertension or diabetes), very long term if not lifelong management is required for patients with osteoporosis. Persistent or even greater reduction of fracture risk with treatment up to 10 years, compared with the rate of fracture in the placebo or treated group during the first 3 years of the study, has been observed with zoledronate and denosumab.3-5 Denosumab was not included in the systematic review by Fink and colleagues since the pivotal fracture trial with that agent was placebo-controlled for only 3 years.6

Sequential drug treatment may be best. Fink and colleagues also did not consider new evidence, which suggests that the use of osteoporosis drugs in sequence—rather than a single agent for a long time—may be the most effective management strategy.7,8

More consideration should be given to the use of estrogen and raloxifene in younger postmenopausal women at risk for vertebral but not hip fracture.

Only treat high-risk patients. Using osteoporosis therapies to only treat patients at high risk for fracture will optimize the benefit:risk ratio and cost-effectiveness of therapy.

Bisphosphonate holidays may not be as important as once thought. BMD and fracture risk reduction does not improve after 5 years of bisphosphonate therapy, and longer treatment may increase the risk of atypic

Hip BMD may serve as indicator for treatment decisions. Recent evidence indicating that the change in hip BMD with treatment or the level of hip BMD achieved on treatment correlates with fracture risk reduction may provide a useful clinical target to guide treatment decisions.9,10

Because we have a lack of pristine evidence does not mean that we shouldn’t treat osteoporosis; we have to do the best we can with the limited evidence we have. Therapy must be individualized, for we are not just treating osteoporosis, we are treating patients with osteoporosis.

In a recent systematic review, Fink and colleagues attempted to summarize the published evidence of the efficacy and safety of long-term (> 3 years) therapy for osteoporosis.1 Unfortunately, they arrived at very limited and tentative conclusions because, as they point out, of the paucity of such evidence.

Why long-term studies stop short

Only 3 of the several tens of placebo-controlled fracture end-point studies (about 58 trials and observational studies) that Fink and colleagues reviewed evaluated treatment for more than 3 years. The nonavailability of longer-term studies is the direct consequence of a requirement by regulatory agencies for a 3-year fracture end-point study in order to register a new drug for osteoporosis. Hence, longer, placebo-controlled studies do not benefit the industry sponsor, and enrolling patients with osteoporosis or who are at high risk for fracture in any, much less long, placebo-controlled trials is now considered to be unethical.

What the authors did observe

From this limited set of information with which to evaluate, Fink and colleagues observed that long-term therapy with raloxifene reduces the risk of vertebral fractures but is associated with thromboembolic complications. In addition, treatment for more than 3 years with bisphosphonates reduces the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but may increase risk of rare adverse events (including femoral shaft fractures with atypical radiographic features).

The bisphosphonate holiday. The authors refer to the even more limited evidence about the effects of discontinuing bisphosphonate therapy. Unlike the rapid loss of bone mass density (BMD) and fracture protection upon stopping estrogen or denosumab, the offset of these treatment benefits is slower when bisphosphonates are discontinued. This, coupled with concern about increasing risk with long-term bisphosphonate therapy, led to the confusing concept of a “bisphosphonate holiday.” While recommendations to consider temporary discontinuation of bisphosphonates in patients at low risk for fracture have been made by expert panels,2 very little information exists about the benefits/risks of this strategy, how long the treatment interruption should be, or how to decide when and with what to restart therapy. Unfortunately, overall, Fink and colleagues’ observations provide little practical guidance for clinicians.

Continue to: What we can learn from longer term and recent studies of ideal treatment...

What we can learn from longer term and recent studies of ideal treatment

Since we have no “cure” for osteoporosis, and since the benefits of therapy, including protection from fractures, abate upon stopping treatment (as they do when we stop treating hypertension or diabetes), very long term if not lifelong management is required for patients with osteoporosis. Persistent or even greater reduction of fracture risk with treatment up to 10 years, compared with the rate of fracture in the placebo or treated group during the first 3 years of the study, has been observed with zoledronate and denosumab.3-5 Denosumab was not included in the systematic review by Fink and colleagues since the pivotal fracture trial with that agent was placebo-controlled for only 3 years.6

Sequential drug treatment may be best. Fink and colleagues also did not consider new evidence, which suggests that the use of osteoporosis drugs in sequence—rather than a single agent for a long time—may be the most effective management strategy.7,8

More consideration should be given to the use of estrogen and raloxifene in younger postmenopausal women at risk for vertebral but not hip fracture.

Only treat high-risk patients. Using osteoporosis therapies to only treat patients at high risk for fracture will optimize the benefit:risk ratio and cost-effectiveness of therapy.

Bisphosphonate holidays may not be as important as once thought. BMD and fracture risk reduction does not improve after 5 years of bisphosphonate therapy, and longer treatment may increase the risk of atypic

Hip BMD may serve as indicator for treatment decisions. Recent evidence indicating that the change in hip BMD with treatment or the level of hip BMD achieved on treatment correlates with fracture risk reduction may provide a useful clinical target to guide treatment decisions.9,10

Because we have a lack of pristine evidence does not mean that we shouldn’t treat osteoporosis; we have to do the best we can with the limited evidence we have. Therapy must be individualized, for we are not just treating osteoporosis, we are treating patients with osteoporosis.

- Fink HA, MacDonald R, Forte ML, et al. Long-term drug therapy and drug discontinuations and holidays for osteoporosis fracture prevention: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:37-50.

- Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:16-35.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Cauley JA, et al. The effect of 6 versus 9 years of zoledronic acid treatment in osteoporosis: a randomized second extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:934-944.

- Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:513-523.

- Ferrari S, Butler PW, Kendler DL, et al. Further nonvertebral fracture reduction beyond 3 years for up to 10 years of denosumab treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:3450-3461.

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765.

- Cosman F, Nieves JW, Dempster DW. Treatment sequence matters: anabolic and antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:198-202.

- Hanley DA, McClung MR, Davison KS, et al; Writing Group for the Western Osteoporosis Alliance. Western Osteoporosis Alliance Clinical Practice Series: evaluating the balance of benefits and risks of long-term osteoporosis therapies. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e1-862.e7.

- Bouxsein ML, Eastell R, Lui LY, et al; FNIH Bone Quality Project. Change in bone density and reduction in fracture risk: a meta-regression of published trials. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:632-642.

- Ferrari S, Libanati C, Lin CJF, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density T-score and nonvertebral fracture risk over 10 years of denosumab treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:1033-1040.

- Fink HA, MacDonald R, Forte ML, et al. Long-term drug therapy and drug discontinuations and holidays for osteoporosis fracture prevention: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:37-50.

- Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:16-35.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Cauley JA, et al. The effect of 6 versus 9 years of zoledronic acid treatment in osteoporosis: a randomized second extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:934-944.

- Bone HG, Wagman RB, Brandi ML, et al. 10 years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the phase 3 randomised FREEDOM trial and open-label extension. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:513-523.

- Ferrari S, Butler PW, Kendler DL, et al. Further nonvertebral fracture reduction beyond 3 years for up to 10 years of denosumab treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:3450-3461.

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:756-765.

- Cosman F, Nieves JW, Dempster DW. Treatment sequence matters: anabolic and antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:198-202.

- Hanley DA, McClung MR, Davison KS, et al; Writing Group for the Western Osteoporosis Alliance. Western Osteoporosis Alliance Clinical Practice Series: evaluating the balance of benefits and risks of long-term osteoporosis therapies. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e1-862.e7.

- Bouxsein ML, Eastell R, Lui LY, et al; FNIH Bone Quality Project. Change in bone density and reduction in fracture risk: a meta-regression of published trials. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:632-642.

- Ferrari S, Libanati C, Lin CJF, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density T-score and nonvertebral fracture risk over 10 years of denosumab treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34:1033-1040.

Older black women have worse outcomes after fragility fracture

ORLANDO – Older black women with postmenopausal osteoporosis had significantly higher mortality rates, were more likely to be placed in a long-term nursing facility, and were more likely to become newly eligible for Medicaid after a major fragility fracture event, compared with their white counterparts, according to a findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Previous studies have examined racial differences in mortality and outcomes after fracture, but the data from those studies are older or limited to a certain region or health system, Nicole C. Wright, PhD, MPH, of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in her presentation.

“To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive evaluation of fractures and outcomes post fracture by race, particularly in black women,” she said.

Using Medicare data from between 2010 and 2016, Dr. Wright and colleagues performed a cohort-based, descriptive study of 400,479 white women and 11,563 black women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, who were covered by Medicare Parts A, B, C and D and had a hip, pelvis, femur, radius/ulna, humerus, or clinical vertebral fractures. Fractures were identified by way of a validated algorithm that used inpatient and outpatient claims, outpatient physical evaluations, and management claims, together with fracture repair codes (positive predictive value range, 90.9%-98.6%; from Wright N et al. J Bone Min Res. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3807).

The groups had similar proportions of patients in each age group (65-75 years, 75-84 years, 85 years and older), with a slightly higher percentage of younger black patients than younger white patients (25.0% vs. 22.4%, respectively). Black patients were more likely than white patients to be from the South (58.6% vs. 39.7%) and have a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 2 or higher (62.9% vs. 45.4%). White patients were more likely than black patients to have a Charlson score of 0 (42.0% vs. 24.1%).

The three identifying outcomes were: death/mortality, which was determined using the date in the Medicare vital status; debility, a term used for patients newly placed in a long-term nursing facility; and destitution, used to describe patients who became newly eligible for Medicaid after a major fragility fracture.

The results showed that the most common fracture types were hip and clinical vertebral fractures, with black women having a significantly lower rate of clinical vertebral fractures (29.0% vs. 34.1%, respectively) but a significantly higher rate of femur fractures (9.1% vs. 3.8%). Black women also had a significantly higher mortality rate after a fracture (19.6% vs. 15.4%), and a significantly higher composite outcome of all three identifying outcome measurements (24.6% vs. 20.2%). However, rates of debility and destitution were similar between the groups.

When measured by fracture type, black women had significantly different 1-year postfracture outcomes, compared with white women, with a 38.0% higher incidence of mortality, 40.2% higher rate of debility, 185.0% higher rate of destitution, and 35.4% higher composite outcome for hip fracture. For radius/ulna fractures, black women also had a 59.7% higher rate of death, 8.5% higher rate of debility, 164.7% higher rate of destitution, and 43.0% higher composite outcomes; and for clinical vertebral fractures, they had 11.4% higher rate of death, 10.8% higher rate of debility, 130.6% higher rate of destitution, and 13.6% higher composite outcome, compared with white women.

Overall, black women had higher incidence risk ratios for death (IRR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.33), debility (IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.33), and destitution (IRR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.20-2.73) for fractures of the hip; higher IRRs for death (IRR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.33-1.66), debility (IRR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.20), and destitution (IRR, 2.70; 95% CI, 2.33-3.13) for fractures of the radius or ulna; and higher IRRs for death (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.17) and destitution (IRR, 2.40; 95% CI, 2.15-2.67) for clinical vertebral fractures.

“These data show that we need to develop interventions and/or programs to mitigate and reduce disparities in fracture outcomes,” said Dr. Wright.

She noted that the study results were limited because of its observational nature, and results cannot be generalized beyond older women with postmenopausal osteoporosis with Medicare coverage. In addition, the algorithm used to determine fracture status also had a potentially low sensitivity, which may have affected the study results, she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Wright reported receiving grants from Amgen and serving as an expert witness for the law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and Pfizer. Dr. Chen reported receiving grants from Amgen. Dr. Curtis reported receiving grants from, and is a consultant for, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Radius. Dr. Saag reported receiving grants from Amgen and is a consultant for Gilead and Radius.

SOURCE: Wright NC et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstract 1125.

ORLANDO – Older black women with postmenopausal osteoporosis had significantly higher mortality rates, were more likely to be placed in a long-term nursing facility, and were more likely to become newly eligible for Medicaid after a major fragility fracture event, compared with their white counterparts, according to a findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Previous studies have examined racial differences in mortality and outcomes after fracture, but the data from those studies are older or limited to a certain region or health system, Nicole C. Wright, PhD, MPH, of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in her presentation.

“To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive evaluation of fractures and outcomes post fracture by race, particularly in black women,” she said.

Using Medicare data from between 2010 and 2016, Dr. Wright and colleagues performed a cohort-based, descriptive study of 400,479 white women and 11,563 black women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, who were covered by Medicare Parts A, B, C and D and had a hip, pelvis, femur, radius/ulna, humerus, or clinical vertebral fractures. Fractures were identified by way of a validated algorithm that used inpatient and outpatient claims, outpatient physical evaluations, and management claims, together with fracture repair codes (positive predictive value range, 90.9%-98.6%; from Wright N et al. J Bone Min Res. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3807).

The groups had similar proportions of patients in each age group (65-75 years, 75-84 years, 85 years and older), with a slightly higher percentage of younger black patients than younger white patients (25.0% vs. 22.4%, respectively). Black patients were more likely than white patients to be from the South (58.6% vs. 39.7%) and have a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 2 or higher (62.9% vs. 45.4%). White patients were more likely than black patients to have a Charlson score of 0 (42.0% vs. 24.1%).

The three identifying outcomes were: death/mortality, which was determined using the date in the Medicare vital status; debility, a term used for patients newly placed in a long-term nursing facility; and destitution, used to describe patients who became newly eligible for Medicaid after a major fragility fracture.

The results showed that the most common fracture types were hip and clinical vertebral fractures, with black women having a significantly lower rate of clinical vertebral fractures (29.0% vs. 34.1%, respectively) but a significantly higher rate of femur fractures (9.1% vs. 3.8%). Black women also had a significantly higher mortality rate after a fracture (19.6% vs. 15.4%), and a significantly higher composite outcome of all three identifying outcome measurements (24.6% vs. 20.2%). However, rates of debility and destitution were similar between the groups.

When measured by fracture type, black women had significantly different 1-year postfracture outcomes, compared with white women, with a 38.0% higher incidence of mortality, 40.2% higher rate of debility, 185.0% higher rate of destitution, and 35.4% higher composite outcome for hip fracture. For radius/ulna fractures, black women also had a 59.7% higher rate of death, 8.5% higher rate of debility, 164.7% higher rate of destitution, and 43.0% higher composite outcomes; and for clinical vertebral fractures, they had 11.4% higher rate of death, 10.8% higher rate of debility, 130.6% higher rate of destitution, and 13.6% higher composite outcome, compared with white women.

Overall, black women had higher incidence risk ratios for death (IRR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.33), debility (IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.33), and destitution (IRR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.20-2.73) for fractures of the hip; higher IRRs for death (IRR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.33-1.66), debility (IRR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.20), and destitution (IRR, 2.70; 95% CI, 2.33-3.13) for fractures of the radius or ulna; and higher IRRs for death (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.17) and destitution (IRR, 2.40; 95% CI, 2.15-2.67) for clinical vertebral fractures.

“These data show that we need to develop interventions and/or programs to mitigate and reduce disparities in fracture outcomes,” said Dr. Wright.

She noted that the study results were limited because of its observational nature, and results cannot be generalized beyond older women with postmenopausal osteoporosis with Medicare coverage. In addition, the algorithm used to determine fracture status also had a potentially low sensitivity, which may have affected the study results, she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Wright reported receiving grants from Amgen and serving as an expert witness for the law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and Pfizer. Dr. Chen reported receiving grants from Amgen. Dr. Curtis reported receiving grants from, and is a consultant for, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Radius. Dr. Saag reported receiving grants from Amgen and is a consultant for Gilead and Radius.

SOURCE: Wright NC et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstract 1125.

ORLANDO – Older black women with postmenopausal osteoporosis had significantly higher mortality rates, were more likely to be placed in a long-term nursing facility, and were more likely to become newly eligible for Medicaid after a major fragility fracture event, compared with their white counterparts, according to a findings presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Previous studies have examined racial differences in mortality and outcomes after fracture, but the data from those studies are older or limited to a certain region or health system, Nicole C. Wright, PhD, MPH, of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said in her presentation.

“To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive evaluation of fractures and outcomes post fracture by race, particularly in black women,” she said.

Using Medicare data from between 2010 and 2016, Dr. Wright and colleagues performed a cohort-based, descriptive study of 400,479 white women and 11,563 black women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, who were covered by Medicare Parts A, B, C and D and had a hip, pelvis, femur, radius/ulna, humerus, or clinical vertebral fractures. Fractures were identified by way of a validated algorithm that used inpatient and outpatient claims, outpatient physical evaluations, and management claims, together with fracture repair codes (positive predictive value range, 90.9%-98.6%; from Wright N et al. J Bone Min Res. 2019 Jun 6. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3807).

The groups had similar proportions of patients in each age group (65-75 years, 75-84 years, 85 years and older), with a slightly higher percentage of younger black patients than younger white patients (25.0% vs. 22.4%, respectively). Black patients were more likely than white patients to be from the South (58.6% vs. 39.7%) and have a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 2 or higher (62.9% vs. 45.4%). White patients were more likely than black patients to have a Charlson score of 0 (42.0% vs. 24.1%).

The three identifying outcomes were: death/mortality, which was determined using the date in the Medicare vital status; debility, a term used for patients newly placed in a long-term nursing facility; and destitution, used to describe patients who became newly eligible for Medicaid after a major fragility fracture.

The results showed that the most common fracture types were hip and clinical vertebral fractures, with black women having a significantly lower rate of clinical vertebral fractures (29.0% vs. 34.1%, respectively) but a significantly higher rate of femur fractures (9.1% vs. 3.8%). Black women also had a significantly higher mortality rate after a fracture (19.6% vs. 15.4%), and a significantly higher composite outcome of all three identifying outcome measurements (24.6% vs. 20.2%). However, rates of debility and destitution were similar between the groups.

When measured by fracture type, black women had significantly different 1-year postfracture outcomes, compared with white women, with a 38.0% higher incidence of mortality, 40.2% higher rate of debility, 185.0% higher rate of destitution, and 35.4% higher composite outcome for hip fracture. For radius/ulna fractures, black women also had a 59.7% higher rate of death, 8.5% higher rate of debility, 164.7% higher rate of destitution, and 43.0% higher composite outcomes; and for clinical vertebral fractures, they had 11.4% higher rate of death, 10.8% higher rate of debility, 130.6% higher rate of destitution, and 13.6% higher composite outcome, compared with white women.

Overall, black women had higher incidence risk ratios for death (IRR, 1.24; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.33), debility (IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.06-1.33), and destitution (IRR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.20-2.73) for fractures of the hip; higher IRRs for death (IRR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.33-1.66), debility (IRR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.20), and destitution (IRR, 2.70; 95% CI, 2.33-3.13) for fractures of the radius or ulna; and higher IRRs for death (IRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.17) and destitution (IRR, 2.40; 95% CI, 2.15-2.67) for clinical vertebral fractures.

“These data show that we need to develop interventions and/or programs to mitigate and reduce disparities in fracture outcomes,” said Dr. Wright.

She noted that the study results were limited because of its observational nature, and results cannot be generalized beyond older women with postmenopausal osteoporosis with Medicare coverage. In addition, the algorithm used to determine fracture status also had a potentially low sensitivity, which may have affected the study results, she said.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Wright reported receiving grants from Amgen and serving as an expert witness for the law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and Pfizer. Dr. Chen reported receiving grants from Amgen. Dr. Curtis reported receiving grants from, and is a consultant for, Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Radius. Dr. Saag reported receiving grants from Amgen and is a consultant for Gilead and Radius.

SOURCE: Wright NC et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstract 1125.

REPORTING FROM ASBMR 2019

Lumbar spine BMD, bone strength benefits persist after romosozumab-to-alendronate switch

ORLANDO – Patients who took romosozumab for 12 months and then switched to alendronate continued to see benefits in bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine after 12 months of therapy with alendronate, compared with patients who began taking, and continued to take, alendronate over the same time period, according to findings from a subgroup of the ARCH study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

“These effects occurred rapidly, as early as month 6, were sustained beyond 12 months after transitioning to alendronate, and are consistent with greater fracture-risk reduction observed in ARCH with romosozumab to alendronate versus alendronate to alendronate,” Jacques P. Brown, MD, FRCPC, of Laval University, Quebec City, said in his presentation.

In the double-blinded ARCH study, 4,093 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and a previous fracture history were randomized to receive subcutaneous monthly romosozumab 210 mg or oral weekly alendronate 70 mg for 12 months, followed by an open-label period during which romosozumab patients received oral weekly alendronate 70 mg and alendronate patients continued to receive the same dose on the same schedule for an additional 24 months (Saag KG et al. N Eng J Med. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708322).

Dr. Brown and colleagues performed an imaging substudy of ARCH, which included examining how the romosozumab-to-alendronate and alendronate-only groups improved lumbar spine BMD and lumbar spine bone strength. Lumbar spine BMD was assessed through quantitative CT, and lumbar spine bone strength was measured with finite element analysis. The researchers received quantitative CT images from baseline and at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months, and determined the percentage change at each of those periods to calculate integral, trabecular, and cortical lumbar spine volumetric BMD (vBMD), and to bone mineral content (BMC). They also measured areal BMD (aBMD) at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Overall, 49 romosozumab patients and 41 alendronate patients from the ARCH study were enrolled in the imaging substudy. Of those patients, 76 had vBMD and BMC information available at baseline and one or more time periods post baseline, and 86 patients had finite element analysis data at baseline and one or more postbaseline time periods. Patients in the romosozumab and alendronate groups had similar baseline characteristics with regard to age (73.1 years vs. 72.8 years, respectively), mean lumbar spine BMD T score (–2.82 vs. –3.38), mean total hip BMD T score (–2.65 vs. –2.75), mean femoral neck T score (–2.84 vs. –2.83), mean lumbar spine integral vBMD (130.3 mg/cm3 vs. 120.5 mg/cm3), trabecular vBMD (60.1 mg/cm3 vs. 53.7 mg/cm3) and cortical vBMD (284.6 mg/cm3 vs. 270.9 mg/cm3). Patients in both groups also had similar rates of previous osteoporotic fracture at or after aged 45 years, previous vertebral fracture, and history of hip fracture.

Beginning at 6 months, there were significant least squares mean BMD improvements in both groups, but the romosozumab group had significant improvements in aBMD percentage changes, compared with the alendronate group, which persisted until 24 months (P less than .001 at all time points). Integral, trabecular, and cortical vBMD in the romosozumab group also saw significantly greater increases from baseline, compared with the alendronate group, and those results persisted in the open-label portion of the study for patients in the romosozumab group who transitioned to alendronate and patients in the alendronate to alendronate group (P less than .001 at all time points).

“The rapid and large increases in BMD with romosozumab followed by BMD consolidation where [patients were] transitioning to alendronate, support the important role of romosozumab as a first-line therapy in treating patients who are at very high risk for fracture,” Dr. Brown said.

In regard to BMC, there were larger increases in least squares mean BMC changes from baseline in the cortical compartment than the trabecular compartment, and actual change in bone strength as measured by finite element analysis was highly correlated with integral BMC in the romosozumab group.

Dr. Brown said the study was limited to the small sample size from the imaging substudy of ARCH, and quantitative CT dictated the imaging sites for the substudy, which may have affected patient selection. However, he noted that the characteristics of the ARCH imaging substudy were similar to patients in the overall ARCH study.

Amgen, UCB Pharma, and Astellas Pharma funded the study in part. Amgen and UCB Pharma assisted in the preparation of Dr. Brown’s presentation at ASBMR 2019, including funding costs associated with its development. Dr. Brown and the other coauthors reported relationships with Amgen, UCB Pharma, and other companies in the form of consultancies, grants and research support, speaker’s bureau appointments, paid employment, and stock options.

SOURCE: Brown JP et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstract 1050.

ORLANDO – Patients who took romosozumab for 12 months and then switched to alendronate continued to see benefits in bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine after 12 months of therapy with alendronate, compared with patients who began taking, and continued to take, alendronate over the same time period, according to findings from a subgroup of the ARCH study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

“These effects occurred rapidly, as early as month 6, were sustained beyond 12 months after transitioning to alendronate, and are consistent with greater fracture-risk reduction observed in ARCH with romosozumab to alendronate versus alendronate to alendronate,” Jacques P. Brown, MD, FRCPC, of Laval University, Quebec City, said in his presentation.

In the double-blinded ARCH study, 4,093 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and a previous fracture history were randomized to receive subcutaneous monthly romosozumab 210 mg or oral weekly alendronate 70 mg for 12 months, followed by an open-label period during which romosozumab patients received oral weekly alendronate 70 mg and alendronate patients continued to receive the same dose on the same schedule for an additional 24 months (Saag KG et al. N Eng J Med. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708322).

Dr. Brown and colleagues performed an imaging substudy of ARCH, which included examining how the romosozumab-to-alendronate and alendronate-only groups improved lumbar spine BMD and lumbar spine bone strength. Lumbar spine BMD was assessed through quantitative CT, and lumbar spine bone strength was measured with finite element analysis. The researchers received quantitative CT images from baseline and at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months, and determined the percentage change at each of those periods to calculate integral, trabecular, and cortical lumbar spine volumetric BMD (vBMD), and to bone mineral content (BMC). They also measured areal BMD (aBMD) at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Overall, 49 romosozumab patients and 41 alendronate patients from the ARCH study were enrolled in the imaging substudy. Of those patients, 76 had vBMD and BMC information available at baseline and one or more time periods post baseline, and 86 patients had finite element analysis data at baseline and one or more postbaseline time periods. Patients in the romosozumab and alendronate groups had similar baseline characteristics with regard to age (73.1 years vs. 72.8 years, respectively), mean lumbar spine BMD T score (–2.82 vs. –3.38), mean total hip BMD T score (–2.65 vs. –2.75), mean femoral neck T score (–2.84 vs. –2.83), mean lumbar spine integral vBMD (130.3 mg/cm3 vs. 120.5 mg/cm3), trabecular vBMD (60.1 mg/cm3 vs. 53.7 mg/cm3) and cortical vBMD (284.6 mg/cm3 vs. 270.9 mg/cm3). Patients in both groups also had similar rates of previous osteoporotic fracture at or after aged 45 years, previous vertebral fracture, and history of hip fracture.

Beginning at 6 months, there were significant least squares mean BMD improvements in both groups, but the romosozumab group had significant improvements in aBMD percentage changes, compared with the alendronate group, which persisted until 24 months (P less than .001 at all time points). Integral, trabecular, and cortical vBMD in the romosozumab group also saw significantly greater increases from baseline, compared with the alendronate group, and those results persisted in the open-label portion of the study for patients in the romosozumab group who transitioned to alendronate and patients in the alendronate to alendronate group (P less than .001 at all time points).

“The rapid and large increases in BMD with romosozumab followed by BMD consolidation where [patients were] transitioning to alendronate, support the important role of romosozumab as a first-line therapy in treating patients who are at very high risk for fracture,” Dr. Brown said.

In regard to BMC, there were larger increases in least squares mean BMC changes from baseline in the cortical compartment than the trabecular compartment, and actual change in bone strength as measured by finite element analysis was highly correlated with integral BMC in the romosozumab group.

Dr. Brown said the study was limited to the small sample size from the imaging substudy of ARCH, and quantitative CT dictated the imaging sites for the substudy, which may have affected patient selection. However, he noted that the characteristics of the ARCH imaging substudy were similar to patients in the overall ARCH study.

Amgen, UCB Pharma, and Astellas Pharma funded the study in part. Amgen and UCB Pharma assisted in the preparation of Dr. Brown’s presentation at ASBMR 2019, including funding costs associated with its development. Dr. Brown and the other coauthors reported relationships with Amgen, UCB Pharma, and other companies in the form of consultancies, grants and research support, speaker’s bureau appointments, paid employment, and stock options.

SOURCE: Brown JP et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstract 1050.

ORLANDO – Patients who took romosozumab for 12 months and then switched to alendronate continued to see benefits in bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine after 12 months of therapy with alendronate, compared with patients who began taking, and continued to take, alendronate over the same time period, according to findings from a subgroup of the ARCH study presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

“These effects occurred rapidly, as early as month 6, were sustained beyond 12 months after transitioning to alendronate, and are consistent with greater fracture-risk reduction observed in ARCH with romosozumab to alendronate versus alendronate to alendronate,” Jacques P. Brown, MD, FRCPC, of Laval University, Quebec City, said in his presentation.

In the double-blinded ARCH study, 4,093 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and a previous fracture history were randomized to receive subcutaneous monthly romosozumab 210 mg or oral weekly alendronate 70 mg for 12 months, followed by an open-label period during which romosozumab patients received oral weekly alendronate 70 mg and alendronate patients continued to receive the same dose on the same schedule for an additional 24 months (Saag KG et al. N Eng J Med. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708322).

Dr. Brown and colleagues performed an imaging substudy of ARCH, which included examining how the romosozumab-to-alendronate and alendronate-only groups improved lumbar spine BMD and lumbar spine bone strength. Lumbar spine BMD was assessed through quantitative CT, and lumbar spine bone strength was measured with finite element analysis. The researchers received quantitative CT images from baseline and at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months, and determined the percentage change at each of those periods to calculate integral, trabecular, and cortical lumbar spine volumetric BMD (vBMD), and to bone mineral content (BMC). They also measured areal BMD (aBMD) at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Overall, 49 romosozumab patients and 41 alendronate patients from the ARCH study were enrolled in the imaging substudy. Of those patients, 76 had vBMD and BMC information available at baseline and one or more time periods post baseline, and 86 patients had finite element analysis data at baseline and one or more postbaseline time periods. Patients in the romosozumab and alendronate groups had similar baseline characteristics with regard to age (73.1 years vs. 72.8 years, respectively), mean lumbar spine BMD T score (–2.82 vs. –3.38), mean total hip BMD T score (–2.65 vs. –2.75), mean femoral neck T score (–2.84 vs. –2.83), mean lumbar spine integral vBMD (130.3 mg/cm3 vs. 120.5 mg/cm3), trabecular vBMD (60.1 mg/cm3 vs. 53.7 mg/cm3) and cortical vBMD (284.6 mg/cm3 vs. 270.9 mg/cm3). Patients in both groups also had similar rates of previous osteoporotic fracture at or after aged 45 years, previous vertebral fracture, and history of hip fracture.

Beginning at 6 months, there were significant least squares mean BMD improvements in both groups, but the romosozumab group had significant improvements in aBMD percentage changes, compared with the alendronate group, which persisted until 24 months (P less than .001 at all time points). Integral, trabecular, and cortical vBMD in the romosozumab group also saw significantly greater increases from baseline, compared with the alendronate group, and those results persisted in the open-label portion of the study for patients in the romosozumab group who transitioned to alendronate and patients in the alendronate to alendronate group (P less than .001 at all time points).

“The rapid and large increases in BMD with romosozumab followed by BMD consolidation where [patients were] transitioning to alendronate, support the important role of romosozumab as a first-line therapy in treating patients who are at very high risk for fracture,” Dr. Brown said.

In regard to BMC, there were larger increases in least squares mean BMC changes from baseline in the cortical compartment than the trabecular compartment, and actual change in bone strength as measured by finite element analysis was highly correlated with integral BMC in the romosozumab group.

Dr. Brown said the study was limited to the small sample size from the imaging substudy of ARCH, and quantitative CT dictated the imaging sites for the substudy, which may have affected patient selection. However, he noted that the characteristics of the ARCH imaging substudy were similar to patients in the overall ARCH study.

Amgen, UCB Pharma, and Astellas Pharma funded the study in part. Amgen and UCB Pharma assisted in the preparation of Dr. Brown’s presentation at ASBMR 2019, including funding costs associated with its development. Dr. Brown and the other coauthors reported relationships with Amgen, UCB Pharma, and other companies in the form of consultancies, grants and research support, speaker’s bureau appointments, paid employment, and stock options.

SOURCE: Brown JP et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstract 1050.

REPORTING FROM ASBMR 2019

Vitamin D does not improve bone density, structure in healthy patients

ORLANDO – after 2 years of daily use, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

“Participants may have already reached the vitamin D level needed for bone health,” Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in her presentation.

Dr. LeBoff presented results from 771 patients (mean age, 63.8 years) in the Bone Health Subcohort of VITAL (Vitamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL) who were not on any bone active medications and were randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 at a dose of 2,000 IU or placebo. Patients received bone imaging at baseline and at 2 years; areal bone mineral density (aBMD) of the whole body, femoral neck, total hip, and spine was assessed via dual x-ray absorptiometry scan. Total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels were measured via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, and free 25(OH)D levels were measured via the ELISA assay. The baseline characteristics of the vitamin D3 supplementation and placebo groups were similar. Overall, 52% of patients had osteopenia and 10.4% had osteoporosis.

Between baseline and 2 years, the vitamin D group’s total 25(OH)D levels increased from a mean 27.0 ng/mL to 39.5 ng/mL (46%) and the free 25(OH)D levels increased from 5.8 pg/mL to 9.0 pg/mL (55%), whereas levels in the placebo stayed the same. The researchers found no significant absolute percentage changes over 2 years in aBMD of the whole body (P = .60), femoral neck (P = .16), total hip (P = .23) and spine (P = .55), compared with patients in the placebo group.

In a secondary analysis, Dr. LeBoff and colleagues found no benefit to volumetric BMD (vBMD) of the radius and the tibia at 2 years, and the results persisted after they performed a sensitivity analysis. Adverse events, such as hypercalciuria, kidney stones, and gastrointestinal symptoms, were not significantly different in the vitamin D group, compared with the placebo group.

Dr. LeBoff noted among the limitations of the study that it evaluated one dose level of vitamin D and was not designed to determine whether vitamin D supplementation was effective in people with vitamin D insufficiency, and the results are not generalizable to patients with osteoporosis or osteomalacia. Future studies should also examine whether free 25(OH)D levels can be used to detect which patients can benefit from vitamin D supplementation, she added.

Risk of falls

In a separate abstract, which Dr. LeBoff presented in a different session, 12,927 patients who received vitamin D supplementation for 5 years, were studied for risk of falls, compared with 12,994 individuals in a placebo group. At baseline, 33.3% of patients had fallen at least once in the previous year, and overall 6,605 patients reported 13,235 falls. At 5.3 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in number of falls between groups, falls leading to injury, and falls leading to a doctor or a hospital visit.

There are ongoing parallel studies examining the incidence of fractures between groups in the total population of the VITAL study (25,871 participants); bone turnover markers; bone microarchitecture measurements through high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; and examining the connection between free 25(OH)D, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D binding protein, said Dr. LeBoff.

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Dr. LeBoff reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Two authors reported nonfinancial support Pharmavite LLC of Northridge, Calif., Pronova BioPharma of Norway and BASF, and Quest Diagnostics. The remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: LeBoff M et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstracts 1046 and 1057.

ORLANDO – after 2 years of daily use, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

“Participants may have already reached the vitamin D level needed for bone health,” Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in her presentation.

Dr. LeBoff presented results from 771 patients (mean age, 63.8 years) in the Bone Health Subcohort of VITAL (Vitamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL) who were not on any bone active medications and were randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 at a dose of 2,000 IU or placebo. Patients received bone imaging at baseline and at 2 years; areal bone mineral density (aBMD) of the whole body, femoral neck, total hip, and spine was assessed via dual x-ray absorptiometry scan. Total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels were measured via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, and free 25(OH)D levels were measured via the ELISA assay. The baseline characteristics of the vitamin D3 supplementation and placebo groups were similar. Overall, 52% of patients had osteopenia and 10.4% had osteoporosis.

Between baseline and 2 years, the vitamin D group’s total 25(OH)D levels increased from a mean 27.0 ng/mL to 39.5 ng/mL (46%) and the free 25(OH)D levels increased from 5.8 pg/mL to 9.0 pg/mL (55%), whereas levels in the placebo stayed the same. The researchers found no significant absolute percentage changes over 2 years in aBMD of the whole body (P = .60), femoral neck (P = .16), total hip (P = .23) and spine (P = .55), compared with patients in the placebo group.

In a secondary analysis, Dr. LeBoff and colleagues found no benefit to volumetric BMD (vBMD) of the radius and the tibia at 2 years, and the results persisted after they performed a sensitivity analysis. Adverse events, such as hypercalciuria, kidney stones, and gastrointestinal symptoms, were not significantly different in the vitamin D group, compared with the placebo group.

Dr. LeBoff noted among the limitations of the study that it evaluated one dose level of vitamin D and was not designed to determine whether vitamin D supplementation was effective in people with vitamin D insufficiency, and the results are not generalizable to patients with osteoporosis or osteomalacia. Future studies should also examine whether free 25(OH)D levels can be used to detect which patients can benefit from vitamin D supplementation, she added.

Risk of falls

In a separate abstract, which Dr. LeBoff presented in a different session, 12,927 patients who received vitamin D supplementation for 5 years, were studied for risk of falls, compared with 12,994 individuals in a placebo group. At baseline, 33.3% of patients had fallen at least once in the previous year, and overall 6,605 patients reported 13,235 falls. At 5.3 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in number of falls between groups, falls leading to injury, and falls leading to a doctor or a hospital visit.

There are ongoing parallel studies examining the incidence of fractures between groups in the total population of the VITAL study (25,871 participants); bone turnover markers; bone microarchitecture measurements through high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; and examining the connection between free 25(OH)D, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D binding protein, said Dr. LeBoff.

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Dr. LeBoff reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Two authors reported nonfinancial support Pharmavite LLC of Northridge, Calif., Pronova BioPharma of Norway and BASF, and Quest Diagnostics. The remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: LeBoff M et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstracts 1046 and 1057.

ORLANDO – after 2 years of daily use, according to data presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

“Participants may have already reached the vitamin D level needed for bone health,” Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said in her presentation.

Dr. LeBoff presented results from 771 patients (mean age, 63.8 years) in the Bone Health Subcohort of VITAL (Vitamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL) who were not on any bone active medications and were randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 at a dose of 2,000 IU or placebo. Patients received bone imaging at baseline and at 2 years; areal bone mineral density (aBMD) of the whole body, femoral neck, total hip, and spine was assessed via dual x-ray absorptiometry scan. Total 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels were measured via liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, and free 25(OH)D levels were measured via the ELISA assay. The baseline characteristics of the vitamin D3 supplementation and placebo groups were similar. Overall, 52% of patients had osteopenia and 10.4% had osteoporosis.

Between baseline and 2 years, the vitamin D group’s total 25(OH)D levels increased from a mean 27.0 ng/mL to 39.5 ng/mL (46%) and the free 25(OH)D levels increased from 5.8 pg/mL to 9.0 pg/mL (55%), whereas levels in the placebo stayed the same. The researchers found no significant absolute percentage changes over 2 years in aBMD of the whole body (P = .60), femoral neck (P = .16), total hip (P = .23) and spine (P = .55), compared with patients in the placebo group.

In a secondary analysis, Dr. LeBoff and colleagues found no benefit to volumetric BMD (vBMD) of the radius and the tibia at 2 years, and the results persisted after they performed a sensitivity analysis. Adverse events, such as hypercalciuria, kidney stones, and gastrointestinal symptoms, were not significantly different in the vitamin D group, compared with the placebo group.

Dr. LeBoff noted among the limitations of the study that it evaluated one dose level of vitamin D and was not designed to determine whether vitamin D supplementation was effective in people with vitamin D insufficiency, and the results are not generalizable to patients with osteoporosis or osteomalacia. Future studies should also examine whether free 25(OH)D levels can be used to detect which patients can benefit from vitamin D supplementation, she added.

Risk of falls

In a separate abstract, which Dr. LeBoff presented in a different session, 12,927 patients who received vitamin D supplementation for 5 years, were studied for risk of falls, compared with 12,994 individuals in a placebo group. At baseline, 33.3% of patients had fallen at least once in the previous year, and overall 6,605 patients reported 13,235 falls. At 5.3 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in number of falls between groups, falls leading to injury, and falls leading to a doctor or a hospital visit.

There are ongoing parallel studies examining the incidence of fractures between groups in the total population of the VITAL study (25,871 participants); bone turnover markers; bone microarchitecture measurements through high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography; and examining the connection between free 25(OH)D, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D binding protein, said Dr. LeBoff.

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Dr. LeBoff reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Two authors reported nonfinancial support Pharmavite LLC of Northridge, Calif., Pronova BioPharma of Norway and BASF, and Quest Diagnostics. The remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: LeBoff M et al. ASBMR 2019, Abstracts 1046 and 1057.

REPORTING FROM ASBMR 2019

Project ECHO helps osteoporosis specialists connect with PCPs

ORLANDO – The use of a teleconferencing program to share knowledge about osteoporosis has helped health care professionals learn about the disease and may potentially reduce the osteoporosis treatment gap in underserved communities, according to a speaker at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

The concept, called “technology-enabled collaborative learning,” is intended to address the problem of there being not enough specialists to see patients who need treatment, and the ineffectiveness of educating primary care providers in how to treat complex medical conditions, E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, the director of the New Mexico Clinical Research & Osteoporosis Center said in his presentation.

“Primary care doctors are busy,” said Dr. Lewiecki. “They have limited time taking care of patients. They don’t have the time or often the skills to manage patients who have any questions or concerns about osteoporosis and treatments for osteoporosis.”

One solution, he said, is to find health care professionals in underserved communities who are already interested in and motivated to learn more about osteoporosis, turn them into near-experts on osteoporosis for their patients as well as in their own community.

Dr. Lewiecki proposed the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO), or Project ECHO, an initiative out of the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, as a potential answer. Project ECHO uses videoconferencing to connect experts in a therapeutic area, with Bone Health TeleECHO focusing on raising knowledge of osteoporosis for its participants. “The idea of ECHO is to be a force multiplier to educate health care professionals, each of whom takes care of many patients, and to have many ECHO programs around the world in convenient time zones and convenient languages for people who are interested in participating,” said Dr. Lewiecki.

The idea began when a gastroenterologist at Dr. Lewiecki’s own center was frustrated that patients were not seeking treatment for hepatitis C because of time or travel issues. In response, a pilot program for Project ECHO was developed through a collaboration between the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and the Osteoporosis Foundation of New Mexico where gastroenterologists at University of New Mexico connected with primary care providers across the state, sharing information about hepatitis C and discussing case studies. The results of the pilot program were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and showed a similar rate of sustained viral response between patients treated at the University of New Mexico clinic (84 of 146 patients; 57.5%) and at 21 ECHO clinics (152 of 261 patients; 58.2%) (Arora S et al. N Eng J Med. 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370).

“ECHO expands the capacity to deliver best practice medical care through collegial, interactive, case-based discussions with minimal disruption to the office routine,” said Dr. Lewiecki. “Patients benefit from better care, closer to home, with greater convenience and lower cost than referral to a medical center. And the potential is to reduce the osteoporosis treatment gap by having many ECHOs starting up in many places in the world.”

Today, the ECHO program is in 37 countries, with 322 ECHO hubs and 677 ECHO programs. The top three specialties are endocrinology, orthopedics, and rheumatology; 51% of ECHO participants are primary care providers, 24% are advanced care providers, and 19% are health care providers such as nutritionists, physical therapists, and other providers that have an interest in bone health.

In survey results adapted from a 2017 study from his own group, Dr. Lewiecki showed that 263 health care professionals who participated in Bone Health TeleECHO rated themselves as more confident in 20 different domains of osteoporosis treatment, such as secondary osteoporosis and anabolic therapy, after 21 months of using the ECHO program (Lewiecki EM et al. J Endocr Soc. 2017. doi: 10.1210/js.2017-00361). However, he admitted that showing fracture prevention outcomes at these ECHO centers has proven more difficult.

“Of course, we’re all interested in outcomes. The ultimate outcome here is preventing fractures, but it is extraordinarily difficult to design a study to actually show that we’re reducing fractures, but certainly self-confidence in managing osteoporosis has improved,” he said.

There have also been some misconceptions of the Project ECHO. The program is not only for beginners or primary care providers, said Dr. Lewiecki. It is also not limited to providers in rural areas, as the program has many participants at urban centers, he added.

“We are a virtual community of practice. It’s a collegial relationship,” he said. “It’s really recapitulating the way that we learned during our postgraduate training: When we see a patient, we present the case to our attending, the attending pontificates a little bit, we bounce things off of one another, and we go back and then we do some different things with our patients. And that’s exactly what we do with Echo. It makes learning fun again.”

Dr. Lewiecki challenged the attendees in the room who are already experts in osteoporosis to help share their knowledge of the disease to help other health care professionals learn more about how to better care for their patients. “If you have a passion for teaching, if you want to share knowledge and you’re willing to devote a little bit of your time to doing that and reaching out to more people, this is the way that you can do it.”

Dr. Lewiecki reports research grant support from Amgen, consulting fees from Alexion, Amgen, Radius, Shire, and Ultragenyx, speaking fees from Alexion, Radius, and Shire, and is an advisory board member with the National Osteoporosis Foundation, International Society for Clinical Densitometry, and the Osteoporosis Foundation of New Mexico.

SOURCE: Lewiecki ME. ASBMR 2019. Symposia: Cutting Edge Concepts: Novel Approaches to Reducing Fractures. Bone Health TeleECHO.

ORLANDO – The use of a teleconferencing program to share knowledge about osteoporosis has helped health care professionals learn about the disease and may potentially reduce the osteoporosis treatment gap in underserved communities, according to a speaker at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

The concept, called “technology-enabled collaborative learning,” is intended to address the problem of there being not enough specialists to see patients who need treatment, and the ineffectiveness of educating primary care providers in how to treat complex medical conditions, E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, the director of the New Mexico Clinical Research & Osteoporosis Center said in his presentation.

“Primary care doctors are busy,” said Dr. Lewiecki. “They have limited time taking care of patients. They don’t have the time or often the skills to manage patients who have any questions or concerns about osteoporosis and treatments for osteoporosis.”

One solution, he said, is to find health care professionals in underserved communities who are already interested in and motivated to learn more about osteoporosis, turn them into near-experts on osteoporosis for their patients as well as in their own community.

Dr. Lewiecki proposed the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO), or Project ECHO, an initiative out of the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, as a potential answer. Project ECHO uses videoconferencing to connect experts in a therapeutic area, with Bone Health TeleECHO focusing on raising knowledge of osteoporosis for its participants. “The idea of ECHO is to be a force multiplier to educate health care professionals, each of whom takes care of many patients, and to have many ECHO programs around the world in convenient time zones and convenient languages for people who are interested in participating,” said Dr. Lewiecki.

The idea began when a gastroenterologist at Dr. Lewiecki’s own center was frustrated that patients were not seeking treatment for hepatitis C because of time or travel issues. In response, a pilot program for Project ECHO was developed through a collaboration between the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and the Osteoporosis Foundation of New Mexico where gastroenterologists at University of New Mexico connected with primary care providers across the state, sharing information about hepatitis C and discussing case studies. The results of the pilot program were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and showed a similar rate of sustained viral response between patients treated at the University of New Mexico clinic (84 of 146 patients; 57.5%) and at 21 ECHO clinics (152 of 261 patients; 58.2%) (Arora S et al. N Eng J Med. 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370).

“ECHO expands the capacity to deliver best practice medical care through collegial, interactive, case-based discussions with minimal disruption to the office routine,” said Dr. Lewiecki. “Patients benefit from better care, closer to home, with greater convenience and lower cost than referral to a medical center. And the potential is to reduce the osteoporosis treatment gap by having many ECHOs starting up in many places in the world.”

Today, the ECHO program is in 37 countries, with 322 ECHO hubs and 677 ECHO programs. The top three specialties are endocrinology, orthopedics, and rheumatology; 51% of ECHO participants are primary care providers, 24% are advanced care providers, and 19% are health care providers such as nutritionists, physical therapists, and other providers that have an interest in bone health.

In survey results adapted from a 2017 study from his own group, Dr. Lewiecki showed that 263 health care professionals who participated in Bone Health TeleECHO rated themselves as more confident in 20 different domains of osteoporosis treatment, such as secondary osteoporosis and anabolic therapy, after 21 months of using the ECHO program (Lewiecki EM et al. J Endocr Soc. 2017. doi: 10.1210/js.2017-00361). However, he admitted that showing fracture prevention outcomes at these ECHO centers has proven more difficult.

“Of course, we’re all interested in outcomes. The ultimate outcome here is preventing fractures, but it is extraordinarily difficult to design a study to actually show that we’re reducing fractures, but certainly self-confidence in managing osteoporosis has improved,” he said.

There have also been some misconceptions of the Project ECHO. The program is not only for beginners or primary care providers, said Dr. Lewiecki. It is also not limited to providers in rural areas, as the program has many participants at urban centers, he added.

“We are a virtual community of practice. It’s a collegial relationship,” he said. “It’s really recapitulating the way that we learned during our postgraduate training: When we see a patient, we present the case to our attending, the attending pontificates a little bit, we bounce things off of one another, and we go back and then we do some different things with our patients. And that’s exactly what we do with Echo. It makes learning fun again.”

Dr. Lewiecki challenged the attendees in the room who are already experts in osteoporosis to help share their knowledge of the disease to help other health care professionals learn more about how to better care for their patients. “If you have a passion for teaching, if you want to share knowledge and you’re willing to devote a little bit of your time to doing that and reaching out to more people, this is the way that you can do it.”

Dr. Lewiecki reports research grant support from Amgen, consulting fees from Alexion, Amgen, Radius, Shire, and Ultragenyx, speaking fees from Alexion, Radius, and Shire, and is an advisory board member with the National Osteoporosis Foundation, International Society for Clinical Densitometry, and the Osteoporosis Foundation of New Mexico.

SOURCE: Lewiecki ME. ASBMR 2019. Symposia: Cutting Edge Concepts: Novel Approaches to Reducing Fractures. Bone Health TeleECHO.

ORLANDO – The use of a teleconferencing program to share knowledge about osteoporosis has helped health care professionals learn about the disease and may potentially reduce the osteoporosis treatment gap in underserved communities, according to a speaker at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

The concept, called “technology-enabled collaborative learning,” is intended to address the problem of there being not enough specialists to see patients who need treatment, and the ineffectiveness of educating primary care providers in how to treat complex medical conditions, E. Michael Lewiecki, MD, the director of the New Mexico Clinical Research & Osteoporosis Center said in his presentation.

“Primary care doctors are busy,” said Dr. Lewiecki. “They have limited time taking care of patients. They don’t have the time or often the skills to manage patients who have any questions or concerns about osteoporosis and treatments for osteoporosis.”

One solution, he said, is to find health care professionals in underserved communities who are already interested in and motivated to learn more about osteoporosis, turn them into near-experts on osteoporosis for their patients as well as in their own community.

Dr. Lewiecki proposed the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO), or Project ECHO, an initiative out of the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, as a potential answer. Project ECHO uses videoconferencing to connect experts in a therapeutic area, with Bone Health TeleECHO focusing on raising knowledge of osteoporosis for its participants. “The idea of ECHO is to be a force multiplier to educate health care professionals, each of whom takes care of many patients, and to have many ECHO programs around the world in convenient time zones and convenient languages for people who are interested in participating,” said Dr. Lewiecki.

The idea began when a gastroenterologist at Dr. Lewiecki’s own center was frustrated that patients were not seeking treatment for hepatitis C because of time or travel issues. In response, a pilot program for Project ECHO was developed through a collaboration between the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and the Osteoporosis Foundation of New Mexico where gastroenterologists at University of New Mexico connected with primary care providers across the state, sharing information about hepatitis C and discussing case studies. The results of the pilot program were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and showed a similar rate of sustained viral response between patients treated at the University of New Mexico clinic (84 of 146 patients; 57.5%) and at 21 ECHO clinics (152 of 261 patients; 58.2%) (Arora S et al. N Eng J Med. 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009370).

“ECHO expands the capacity to deliver best practice medical care through collegial, interactive, case-based discussions with minimal disruption to the office routine,” said Dr. Lewiecki. “Patients benefit from better care, closer to home, with greater convenience and lower cost than referral to a medical center. And the potential is to reduce the osteoporosis treatment gap by having many ECHOs starting up in many places in the world.”