User login

New studies inform best practices for pelvic organ prolapse

“Approximately one in five women will undergo surgery for prolapse and/or urinary incontinence by the age of 80, which is more likely than the risk of developing breast cancer,” said David D. Rahn, MD, corresponding author of the study on perioperative vaginal estrogen, in an interview.

“About 13% of women will specifically undergo surgery to repair pelvic organ prolapse,” said Dr. Rahn, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. Reoperation for recurrent prolapse is not uncommon.

In their study, Dr. Rahn and colleagues examined whether the addition of perioperative vaginal estrogen cream in postmenopausal women with prolapse planning surgical correction could both strengthen the repair and lessen the likelihood of recurrence. The researchers randomized 206 postmenopausal women who were seeking surgical repair for bothersome anterior and apical vaginal prolapse to 1 gram of conjugated estrogen cream or a placebo for nightly vaginal insertion for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for at least 5 weeks of preoperative use. The treatment continued twice weekly for 12 months following surgery.

The primary outcome was the time to a failed prolapse repair by 12 months after surgery. Failure was defined by at least one of three criteria, “anatomical/objective prolapse of anterior or posterior walls beyond the hymen or the apex descending more than one-third of the vaginal length, subjective vaginal bulge symptoms, or repeated prolapse treatment,” the researchers wrote. The mean age of the patients was 65 years, and 90% and 92% of patients in the treatment and placebo groups, respectively, were White; 10% and 5%, respectively, were Black. Other baseline characteristics were similar between the groups.

After 12 months, the surgical failure incidence was not significantly different between the vaginal estrogen and placebo groups (19% vs. 9%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.97).

Overall, anatomic recurrence was the most common outcome associated with surgical failure.

However, vaginal atrophy scores for most bothersome symptom was significantly better at 12 months in the vaginal estrogen group, compared with the placebo group, in a subset of 109 patients who reported vaginal atrophy that was at least “moderately bothersome,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of a nonvalidated instrument to assess secondary outcomes, the potentially short time period to the primary outcome, and the inclusion of the apex descending below one third total vaginal length as a criterion for surgical failure (which could be considered conservative), the researchers noted.

Unexpected results

“This work followed logically from a pilot study that similarly randomized postmenopausal women with prolapse planning surgical repair to vaginal estrogen cream versus placebo,” Dr. Rahn said. “In that smaller study, full thickness vaginal wall biopsies were collected at the time of surgery. Those participants who received the estrogen had a thicker vaginal epithelium, thicker underlying muscularis, and appeared to have a more robust concentration of strong connective tissue (i.e., type I collagen) with less of the proteases that break down connective tissue.”

This suggested that preoperative estrogen might optimize the vaginal tissue at the time of the repair. Dr. Rahn said. However, “despite evidence that the application of vaginal estrogen cream decreased the symptoms and signs of atrophic vaginal tissues, this did not lessen the likelihood of pelvic organ prolapse recurrence 12 months after surgical repair.”

The current study “would argue against routine prescription of vaginal estrogen to optimize vaginal tissue for prolapse repair, a practice that is recommended by some experts and commonly prescribed anecdotally,” said Dr. Rahn. “However, in those patients with prolapse and bothersome atrophy-related complaints such as vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse, vaginal estrogen may still be appropriate,” and vaginal estrogen also could be useful for postoperatively for patients prone to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Additional research from the study is underway, said Dr. Rahn. “All participants have now been followed to 3 years after surgery, and those clinical results are now being analyzed. In addition, full-thickness vaginal wall biopsies were collected at the time of all 186 surgeries; these are being analyzed and may yield important information regarding how biomarkers for connective tissue health could point to increased (or decreased) risk for prolapse recurrence.”

Manchester technique surpasses sacrospinous hysteropexy

In the second JAMA study, sacrospinous hysteropexy for uterine-sparing surgical management of uterine prolapse was less effective than the older Manchester procedure, based on data from nearly 400 individuals.

“Until now, the optimal uterus-sparing procedure for the treatment of uterine descent remained uncertain,” lead author Rosa Enklaar, MD, of Radboud (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, said in an interview.

“Globally, there has been a lack of scientific evidence comparing the efficacy of these two techniques, and this study aims to bridge that gap,” she said.

In their study, Dr. Enklaar and colleagues randomized 215 women to sacrospinous hysteropexy and 215 to the Manchester procedure. The mean age of the participants was 61.7 years.

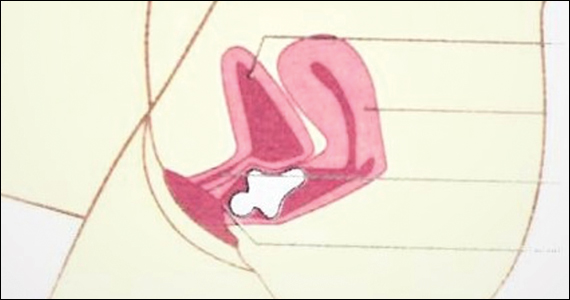

The Manchester procedure involves “extraperitoneal plication of the uterosacral ligaments at the posterior side of the uterus and amputation of the cervix,” and “the cardinal ligaments are plicated on the anterior side of the cervix, “ the researchers wrote.

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of surgical success at 2 years after surgery, defined as the absence of three elements: absence of vaginal prolapse beyond the hymen, absence of bothersome bulge symptoms, and absence of retreatment of current prolapse.

Overall, 87.3% of patients in the Manchester group and 77.0% in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group met the primary outcome. At the end of the 2-year follow-up period, perioperative and patient-reported outcomes were not significantly different between the groups.

Dr. Enklaar said she was surprised by the findings. “At the start of this study, we hypothesized that there would be no difference between the two techniques,” as both have been used for a long period of time.

However, “based on the composite outcome of success at 2-year follow-up after the primary uterus-sparing surgery for uterine descent in patients with pelvic organ prolapse, these findings indicate that the sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester procedure,” she said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of blinding and the applicability of the results only to women without uterine prolapse past the hymen, as well as the exclusion of patients with higher-stage prolapse, the researchers said. However, the results suggest that sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester technique for uterine-sparing pelvic organ prolapse surgery.

As for additional research, few studies of prolapse surgery with long-term follow-up data are available, Dr. Enklaar said. “It is important that this current study will be continued to see the results after a longer follow-up period. Personalized health care is increasingly important, and we need to provide adequate information when counselling patients. With studies such as this one, we hope to improve the choices regarding surgical treatment of uterine descent.”

Studies challenge current prolapse protocols

The study by Dr. Rahn and colleagues contradicts the common clinical practice of preoperative vaginal estrogen to reduce recurrence of prolapse, wrote Charles W. Nager, MD, of the University of California San Diego Health, La Jolla, in an accompanying editorial that addressed both studies.

The results suggest that use of perioperative intravaginal estrogen had no impact on outcomes, “despite the surgeon assessment of less atrophy and better vaginal apex tissue in the estrogen group,” he noted. Although vaginal estrogen has other benefits in terms of patient symptoms and effects on the vaginal epithelium, “surgeons should not prescribe vaginal estrogen with the expectation that it will improve surgical success.”

The study by Dr. Enklaar and colleagues reflects the growing interest in uterine-conserving procedures, Dr. Nager wrote. The modified Manchester procedure conforms to professional society guidelines, and the composite outcome conforms to current standards for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse.

Although suspension of the vaginal apex was quite successful, the researchers interpreted their noninferiority findings with caution, said Dr. Nager. However, they suggested that the modified Manchester procedure as performed in their study “has a role in modern prolapse surgical repair for women with uterine descent that does not protrude beyond the hymen.”

The vaginal estrogen study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, a Bridge Award from the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology and the American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation. Dr. Rahn disclosed grants from the National Institute on Aging, the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology, and the AAOGF bridge award, as well as nonfinancial support from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and Pfizer during the study. The uterine prolapse study was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Nager had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Approximately one in five women will undergo surgery for prolapse and/or urinary incontinence by the age of 80, which is more likely than the risk of developing breast cancer,” said David D. Rahn, MD, corresponding author of the study on perioperative vaginal estrogen, in an interview.

“About 13% of women will specifically undergo surgery to repair pelvic organ prolapse,” said Dr. Rahn, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. Reoperation for recurrent prolapse is not uncommon.

In their study, Dr. Rahn and colleagues examined whether the addition of perioperative vaginal estrogen cream in postmenopausal women with prolapse planning surgical correction could both strengthen the repair and lessen the likelihood of recurrence. The researchers randomized 206 postmenopausal women who were seeking surgical repair for bothersome anterior and apical vaginal prolapse to 1 gram of conjugated estrogen cream or a placebo for nightly vaginal insertion for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for at least 5 weeks of preoperative use. The treatment continued twice weekly for 12 months following surgery.

The primary outcome was the time to a failed prolapse repair by 12 months after surgery. Failure was defined by at least one of three criteria, “anatomical/objective prolapse of anterior or posterior walls beyond the hymen or the apex descending more than one-third of the vaginal length, subjective vaginal bulge symptoms, or repeated prolapse treatment,” the researchers wrote. The mean age of the patients was 65 years, and 90% and 92% of patients in the treatment and placebo groups, respectively, were White; 10% and 5%, respectively, were Black. Other baseline characteristics were similar between the groups.

After 12 months, the surgical failure incidence was not significantly different between the vaginal estrogen and placebo groups (19% vs. 9%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.97).

Overall, anatomic recurrence was the most common outcome associated with surgical failure.

However, vaginal atrophy scores for most bothersome symptom was significantly better at 12 months in the vaginal estrogen group, compared with the placebo group, in a subset of 109 patients who reported vaginal atrophy that was at least “moderately bothersome,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of a nonvalidated instrument to assess secondary outcomes, the potentially short time period to the primary outcome, and the inclusion of the apex descending below one third total vaginal length as a criterion for surgical failure (which could be considered conservative), the researchers noted.

Unexpected results

“This work followed logically from a pilot study that similarly randomized postmenopausal women with prolapse planning surgical repair to vaginal estrogen cream versus placebo,” Dr. Rahn said. “In that smaller study, full thickness vaginal wall biopsies were collected at the time of surgery. Those participants who received the estrogen had a thicker vaginal epithelium, thicker underlying muscularis, and appeared to have a more robust concentration of strong connective tissue (i.e., type I collagen) with less of the proteases that break down connective tissue.”

This suggested that preoperative estrogen might optimize the vaginal tissue at the time of the repair. Dr. Rahn said. However, “despite evidence that the application of vaginal estrogen cream decreased the symptoms and signs of atrophic vaginal tissues, this did not lessen the likelihood of pelvic organ prolapse recurrence 12 months after surgical repair.”

The current study “would argue against routine prescription of vaginal estrogen to optimize vaginal tissue for prolapse repair, a practice that is recommended by some experts and commonly prescribed anecdotally,” said Dr. Rahn. “However, in those patients with prolapse and bothersome atrophy-related complaints such as vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse, vaginal estrogen may still be appropriate,” and vaginal estrogen also could be useful for postoperatively for patients prone to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Additional research from the study is underway, said Dr. Rahn. “All participants have now been followed to 3 years after surgery, and those clinical results are now being analyzed. In addition, full-thickness vaginal wall biopsies were collected at the time of all 186 surgeries; these are being analyzed and may yield important information regarding how biomarkers for connective tissue health could point to increased (or decreased) risk for prolapse recurrence.”

Manchester technique surpasses sacrospinous hysteropexy

In the second JAMA study, sacrospinous hysteropexy for uterine-sparing surgical management of uterine prolapse was less effective than the older Manchester procedure, based on data from nearly 400 individuals.

“Until now, the optimal uterus-sparing procedure for the treatment of uterine descent remained uncertain,” lead author Rosa Enklaar, MD, of Radboud (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, said in an interview.

“Globally, there has been a lack of scientific evidence comparing the efficacy of these two techniques, and this study aims to bridge that gap,” she said.

In their study, Dr. Enklaar and colleagues randomized 215 women to sacrospinous hysteropexy and 215 to the Manchester procedure. The mean age of the participants was 61.7 years.

The Manchester procedure involves “extraperitoneal plication of the uterosacral ligaments at the posterior side of the uterus and amputation of the cervix,” and “the cardinal ligaments are plicated on the anterior side of the cervix, “ the researchers wrote.

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of surgical success at 2 years after surgery, defined as the absence of three elements: absence of vaginal prolapse beyond the hymen, absence of bothersome bulge symptoms, and absence of retreatment of current prolapse.

Overall, 87.3% of patients in the Manchester group and 77.0% in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group met the primary outcome. At the end of the 2-year follow-up period, perioperative and patient-reported outcomes were not significantly different between the groups.

Dr. Enklaar said she was surprised by the findings. “At the start of this study, we hypothesized that there would be no difference between the two techniques,” as both have been used for a long period of time.

However, “based on the composite outcome of success at 2-year follow-up after the primary uterus-sparing surgery for uterine descent in patients with pelvic organ prolapse, these findings indicate that the sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester procedure,” she said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of blinding and the applicability of the results only to women without uterine prolapse past the hymen, as well as the exclusion of patients with higher-stage prolapse, the researchers said. However, the results suggest that sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester technique for uterine-sparing pelvic organ prolapse surgery.

As for additional research, few studies of prolapse surgery with long-term follow-up data are available, Dr. Enklaar said. “It is important that this current study will be continued to see the results after a longer follow-up period. Personalized health care is increasingly important, and we need to provide adequate information when counselling patients. With studies such as this one, we hope to improve the choices regarding surgical treatment of uterine descent.”

Studies challenge current prolapse protocols

The study by Dr. Rahn and colleagues contradicts the common clinical practice of preoperative vaginal estrogen to reduce recurrence of prolapse, wrote Charles W. Nager, MD, of the University of California San Diego Health, La Jolla, in an accompanying editorial that addressed both studies.

The results suggest that use of perioperative intravaginal estrogen had no impact on outcomes, “despite the surgeon assessment of less atrophy and better vaginal apex tissue in the estrogen group,” he noted. Although vaginal estrogen has other benefits in terms of patient symptoms and effects on the vaginal epithelium, “surgeons should not prescribe vaginal estrogen with the expectation that it will improve surgical success.”

The study by Dr. Enklaar and colleagues reflects the growing interest in uterine-conserving procedures, Dr. Nager wrote. The modified Manchester procedure conforms to professional society guidelines, and the composite outcome conforms to current standards for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse.

Although suspension of the vaginal apex was quite successful, the researchers interpreted their noninferiority findings with caution, said Dr. Nager. However, they suggested that the modified Manchester procedure as performed in their study “has a role in modern prolapse surgical repair for women with uterine descent that does not protrude beyond the hymen.”

The vaginal estrogen study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, a Bridge Award from the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology and the American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation. Dr. Rahn disclosed grants from the National Institute on Aging, the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology, and the AAOGF bridge award, as well as nonfinancial support from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and Pfizer during the study. The uterine prolapse study was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Nager had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Approximately one in five women will undergo surgery for prolapse and/or urinary incontinence by the age of 80, which is more likely than the risk of developing breast cancer,” said David D. Rahn, MD, corresponding author of the study on perioperative vaginal estrogen, in an interview.

“About 13% of women will specifically undergo surgery to repair pelvic organ prolapse,” said Dr. Rahn, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas. Reoperation for recurrent prolapse is not uncommon.

In their study, Dr. Rahn and colleagues examined whether the addition of perioperative vaginal estrogen cream in postmenopausal women with prolapse planning surgical correction could both strengthen the repair and lessen the likelihood of recurrence. The researchers randomized 206 postmenopausal women who were seeking surgical repair for bothersome anterior and apical vaginal prolapse to 1 gram of conjugated estrogen cream or a placebo for nightly vaginal insertion for 2 weeks, then twice weekly for at least 5 weeks of preoperative use. The treatment continued twice weekly for 12 months following surgery.

The primary outcome was the time to a failed prolapse repair by 12 months after surgery. Failure was defined by at least one of three criteria, “anatomical/objective prolapse of anterior or posterior walls beyond the hymen or the apex descending more than one-third of the vaginal length, subjective vaginal bulge symptoms, or repeated prolapse treatment,” the researchers wrote. The mean age of the patients was 65 years, and 90% and 92% of patients in the treatment and placebo groups, respectively, were White; 10% and 5%, respectively, were Black. Other baseline characteristics were similar between the groups.

After 12 months, the surgical failure incidence was not significantly different between the vaginal estrogen and placebo groups (19% vs. 9%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.97).

Overall, anatomic recurrence was the most common outcome associated with surgical failure.

However, vaginal atrophy scores for most bothersome symptom was significantly better at 12 months in the vaginal estrogen group, compared with the placebo group, in a subset of 109 patients who reported vaginal atrophy that was at least “moderately bothersome,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the use of a nonvalidated instrument to assess secondary outcomes, the potentially short time period to the primary outcome, and the inclusion of the apex descending below one third total vaginal length as a criterion for surgical failure (which could be considered conservative), the researchers noted.

Unexpected results

“This work followed logically from a pilot study that similarly randomized postmenopausal women with prolapse planning surgical repair to vaginal estrogen cream versus placebo,” Dr. Rahn said. “In that smaller study, full thickness vaginal wall biopsies were collected at the time of surgery. Those participants who received the estrogen had a thicker vaginal epithelium, thicker underlying muscularis, and appeared to have a more robust concentration of strong connective tissue (i.e., type I collagen) with less of the proteases that break down connective tissue.”

This suggested that preoperative estrogen might optimize the vaginal tissue at the time of the repair. Dr. Rahn said. However, “despite evidence that the application of vaginal estrogen cream decreased the symptoms and signs of atrophic vaginal tissues, this did not lessen the likelihood of pelvic organ prolapse recurrence 12 months after surgical repair.”

The current study “would argue against routine prescription of vaginal estrogen to optimize vaginal tissue for prolapse repair, a practice that is recommended by some experts and commonly prescribed anecdotally,” said Dr. Rahn. “However, in those patients with prolapse and bothersome atrophy-related complaints such as vaginal dryness and pain with intercourse, vaginal estrogen may still be appropriate,” and vaginal estrogen also could be useful for postoperatively for patients prone to recurrent urinary tract infections.

Additional research from the study is underway, said Dr. Rahn. “All participants have now been followed to 3 years after surgery, and those clinical results are now being analyzed. In addition, full-thickness vaginal wall biopsies were collected at the time of all 186 surgeries; these are being analyzed and may yield important information regarding how biomarkers for connective tissue health could point to increased (or decreased) risk for prolapse recurrence.”

Manchester technique surpasses sacrospinous hysteropexy

In the second JAMA study, sacrospinous hysteropexy for uterine-sparing surgical management of uterine prolapse was less effective than the older Manchester procedure, based on data from nearly 400 individuals.

“Until now, the optimal uterus-sparing procedure for the treatment of uterine descent remained uncertain,” lead author Rosa Enklaar, MD, of Radboud (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, said in an interview.

“Globally, there has been a lack of scientific evidence comparing the efficacy of these two techniques, and this study aims to bridge that gap,” she said.

In their study, Dr. Enklaar and colleagues randomized 215 women to sacrospinous hysteropexy and 215 to the Manchester procedure. The mean age of the participants was 61.7 years.

The Manchester procedure involves “extraperitoneal plication of the uterosacral ligaments at the posterior side of the uterus and amputation of the cervix,” and “the cardinal ligaments are plicated on the anterior side of the cervix, “ the researchers wrote.

The primary outcome was a composite outcome of surgical success at 2 years after surgery, defined as the absence of three elements: absence of vaginal prolapse beyond the hymen, absence of bothersome bulge symptoms, and absence of retreatment of current prolapse.

Overall, 87.3% of patients in the Manchester group and 77.0% in the sacrospinous hysteropexy group met the primary outcome. At the end of the 2-year follow-up period, perioperative and patient-reported outcomes were not significantly different between the groups.

Dr. Enklaar said she was surprised by the findings. “At the start of this study, we hypothesized that there would be no difference between the two techniques,” as both have been used for a long period of time.

However, “based on the composite outcome of success at 2-year follow-up after the primary uterus-sparing surgery for uterine descent in patients with pelvic organ prolapse, these findings indicate that the sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester procedure,” she said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of blinding and the applicability of the results only to women without uterine prolapse past the hymen, as well as the exclusion of patients with higher-stage prolapse, the researchers said. However, the results suggest that sacrospinous hysteropexy is inferior to the Manchester technique for uterine-sparing pelvic organ prolapse surgery.

As for additional research, few studies of prolapse surgery with long-term follow-up data are available, Dr. Enklaar said. “It is important that this current study will be continued to see the results after a longer follow-up period. Personalized health care is increasingly important, and we need to provide adequate information when counselling patients. With studies such as this one, we hope to improve the choices regarding surgical treatment of uterine descent.”

Studies challenge current prolapse protocols

The study by Dr. Rahn and colleagues contradicts the common clinical practice of preoperative vaginal estrogen to reduce recurrence of prolapse, wrote Charles W. Nager, MD, of the University of California San Diego Health, La Jolla, in an accompanying editorial that addressed both studies.

The results suggest that use of perioperative intravaginal estrogen had no impact on outcomes, “despite the surgeon assessment of less atrophy and better vaginal apex tissue in the estrogen group,” he noted. Although vaginal estrogen has other benefits in terms of patient symptoms and effects on the vaginal epithelium, “surgeons should not prescribe vaginal estrogen with the expectation that it will improve surgical success.”

The study by Dr. Enklaar and colleagues reflects the growing interest in uterine-conserving procedures, Dr. Nager wrote. The modified Manchester procedure conforms to professional society guidelines, and the composite outcome conforms to current standards for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse.

Although suspension of the vaginal apex was quite successful, the researchers interpreted their noninferiority findings with caution, said Dr. Nager. However, they suggested that the modified Manchester procedure as performed in their study “has a role in modern prolapse surgical repair for women with uterine descent that does not protrude beyond the hymen.”

The vaginal estrogen study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, a Bridge Award from the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology and the American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Foundation. Dr. Rahn disclosed grants from the National Institute on Aging, the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology, and the AAOGF bridge award, as well as nonfinancial support from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and Pfizer during the study. The uterine prolapse study was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Nager had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA

Vulvodynia: A little-known and treatable condition

Vulvodynia is a little-known condition that, according to some U.S. studies, affects 3%-14% of the female population. It is defined as chronic pain, present for at least 3 months, that generally involves the vulva or some of its specific areas such as the clitoris or vestibule and is not attributable to causes of an infectious, inflammatory, oncologic, or endocrine nature; skin trauma; or damage to nerve fibers.

“There are probably many more women who suffer from it who don’t talk about it out of shame, because they feel ‘wrong,’ ” said gynecologist Pina Belfiore, MD, chair of the Italian Interdisciplinary Society of Vulvology, at the annual conference of the Italian Society of Gender Medicine in Neurosciences. “It is a treatable condition, or at the very least, a patient’s quality of life can be significantly improved with a personalized therapeutic approach.”

The correct diagnosis

The first step for setting the patient on the right course toward recovery is to offer welcome and empathy, recognizing that the suffering, which can have psychological causes, is not imaginary. “We need to explain to patients that their condition has a name, that they are not alone in this situation, and, above all, that there is hope for solving the problem. They can get through it,” said Dr. Belfiore.

First, an accurate history of the pain is needed to correctly diagnose vulvodynia. How long has the pain been going on? Is it continuous or is it triggered by an environmental factor, for example by sexual intercourse or contact with underwear? Is it a burning or stinging sensation? Did it first occur after an infection or after a physical or psychological trauma? Does the patient suffer from other forms of chronic pain such as recurring headaches or fibromyalgia?

“It is then necessary to inspect the vulva to exclude other systematic conditions or injuries that may be responsible for the pain, as well as to locate hypersensitive areas and evaluate the intensity of the symptoms,” said Dr. Belfiore.” A swab test is performed for this purpose, which is carried out by applying light pressure on different points of the vulva with a cotton swab.”

CNS dysfunction

, which confuses signals coming from the peripheral area, interpreting signals of a different nature as painful stimuli.

“The origin of this dysfunction is an individual predisposition. In fact, often the women who suffer from it are also affected by other forms of chronic pain,” said Dr. Belfiore. “Triggers for vulvodynia can be bacterial infections, candidiasis, or traumatic events such as surgically assisted birth or psychological trauma.”

Because inflammatory mechanisms are not involved, anti-inflammatory drugs are not helpful in treating the problem. “Instead, it is necessary to reduce the sensitivity of the CNS. For this purpose, low-dose antidepressant or antiepileptic drugs are used,” said Dr. Belfiore. “Pelvic floor rehabilitation is another treatment that can be beneficial when combined with pharmacologic treatment. This should be conducted by a professional with specific experience in vulvodynia, because an excessive increase in the tone of the levator ani muscle can make the situation worse. Psychotherapy and the adoption of certain hygienic and behavioral measures can also help, such as using lubricant during sexual intercourse, wearing pure cotton underwear, and using gentle intimate body washes.”

“It is important that family doctors who see women with this problem refer them to an experienced specialist,” said Dr. Belfiore.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was translated from Univadis Italy, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Vulvodynia is a little-known condition that, according to some U.S. studies, affects 3%-14% of the female population. It is defined as chronic pain, present for at least 3 months, that generally involves the vulva or some of its specific areas such as the clitoris or vestibule and is not attributable to causes of an infectious, inflammatory, oncologic, or endocrine nature; skin trauma; or damage to nerve fibers.

“There are probably many more women who suffer from it who don’t talk about it out of shame, because they feel ‘wrong,’ ” said gynecologist Pina Belfiore, MD, chair of the Italian Interdisciplinary Society of Vulvology, at the annual conference of the Italian Society of Gender Medicine in Neurosciences. “It is a treatable condition, or at the very least, a patient’s quality of life can be significantly improved with a personalized therapeutic approach.”

The correct diagnosis

The first step for setting the patient on the right course toward recovery is to offer welcome and empathy, recognizing that the suffering, which can have psychological causes, is not imaginary. “We need to explain to patients that their condition has a name, that they are not alone in this situation, and, above all, that there is hope for solving the problem. They can get through it,” said Dr. Belfiore.

First, an accurate history of the pain is needed to correctly diagnose vulvodynia. How long has the pain been going on? Is it continuous or is it triggered by an environmental factor, for example by sexual intercourse or contact with underwear? Is it a burning or stinging sensation? Did it first occur after an infection or after a physical or psychological trauma? Does the patient suffer from other forms of chronic pain such as recurring headaches or fibromyalgia?

“It is then necessary to inspect the vulva to exclude other systematic conditions or injuries that may be responsible for the pain, as well as to locate hypersensitive areas and evaluate the intensity of the symptoms,” said Dr. Belfiore.” A swab test is performed for this purpose, which is carried out by applying light pressure on different points of the vulva with a cotton swab.”

CNS dysfunction

, which confuses signals coming from the peripheral area, interpreting signals of a different nature as painful stimuli.

“The origin of this dysfunction is an individual predisposition. In fact, often the women who suffer from it are also affected by other forms of chronic pain,” said Dr. Belfiore. “Triggers for vulvodynia can be bacterial infections, candidiasis, or traumatic events such as surgically assisted birth or psychological trauma.”

Because inflammatory mechanisms are not involved, anti-inflammatory drugs are not helpful in treating the problem. “Instead, it is necessary to reduce the sensitivity of the CNS. For this purpose, low-dose antidepressant or antiepileptic drugs are used,” said Dr. Belfiore. “Pelvic floor rehabilitation is another treatment that can be beneficial when combined with pharmacologic treatment. This should be conducted by a professional with specific experience in vulvodynia, because an excessive increase in the tone of the levator ani muscle can make the situation worse. Psychotherapy and the adoption of certain hygienic and behavioral measures can also help, such as using lubricant during sexual intercourse, wearing pure cotton underwear, and using gentle intimate body washes.”

“It is important that family doctors who see women with this problem refer them to an experienced specialist,” said Dr. Belfiore.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was translated from Univadis Italy, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Vulvodynia is a little-known condition that, according to some U.S. studies, affects 3%-14% of the female population. It is defined as chronic pain, present for at least 3 months, that generally involves the vulva or some of its specific areas such as the clitoris or vestibule and is not attributable to causes of an infectious, inflammatory, oncologic, or endocrine nature; skin trauma; or damage to nerve fibers.

“There are probably many more women who suffer from it who don’t talk about it out of shame, because they feel ‘wrong,’ ” said gynecologist Pina Belfiore, MD, chair of the Italian Interdisciplinary Society of Vulvology, at the annual conference of the Italian Society of Gender Medicine in Neurosciences. “It is a treatable condition, or at the very least, a patient’s quality of life can be significantly improved with a personalized therapeutic approach.”

The correct diagnosis

The first step for setting the patient on the right course toward recovery is to offer welcome and empathy, recognizing that the suffering, which can have psychological causes, is not imaginary. “We need to explain to patients that their condition has a name, that they are not alone in this situation, and, above all, that there is hope for solving the problem. They can get through it,” said Dr. Belfiore.

First, an accurate history of the pain is needed to correctly diagnose vulvodynia. How long has the pain been going on? Is it continuous or is it triggered by an environmental factor, for example by sexual intercourse or contact with underwear? Is it a burning or stinging sensation? Did it first occur after an infection or after a physical or psychological trauma? Does the patient suffer from other forms of chronic pain such as recurring headaches or fibromyalgia?

“It is then necessary to inspect the vulva to exclude other systematic conditions or injuries that may be responsible for the pain, as well as to locate hypersensitive areas and evaluate the intensity of the symptoms,” said Dr. Belfiore.” A swab test is performed for this purpose, which is carried out by applying light pressure on different points of the vulva with a cotton swab.”

CNS dysfunction

, which confuses signals coming from the peripheral area, interpreting signals of a different nature as painful stimuli.

“The origin of this dysfunction is an individual predisposition. In fact, often the women who suffer from it are also affected by other forms of chronic pain,” said Dr. Belfiore. “Triggers for vulvodynia can be bacterial infections, candidiasis, or traumatic events such as surgically assisted birth or psychological trauma.”

Because inflammatory mechanisms are not involved, anti-inflammatory drugs are not helpful in treating the problem. “Instead, it is necessary to reduce the sensitivity of the CNS. For this purpose, low-dose antidepressant or antiepileptic drugs are used,” said Dr. Belfiore. “Pelvic floor rehabilitation is another treatment that can be beneficial when combined with pharmacologic treatment. This should be conducted by a professional with specific experience in vulvodynia, because an excessive increase in the tone of the levator ani muscle can make the situation worse. Psychotherapy and the adoption of certain hygienic and behavioral measures can also help, such as using lubricant during sexual intercourse, wearing pure cotton underwear, and using gentle intimate body washes.”

“It is important that family doctors who see women with this problem refer them to an experienced specialist,” said Dr. Belfiore.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was translated from Univadis Italy, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Best practices document outlines genitourinary applications of lasers and energy-based devices

PHOENIX –

“Even a cursory review of PubMed today yields over 100,000 results” on this topic, Macrene R. Alexiades, MD, PhD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Add to that radiofrequency and various diagnoses, the number of publications has skyrocketed, particularly over the last 10 years.”

What has been missing from this hot research topic all these years, she continued, is that no one has distilled this pile of data into a practical guide for office-based clinicians who use lasers and energy-based devices for genitourinary conditions – until now. Working with experts in gynecology and urogynecology, Dr. Alexiades spearheaded a 2-year-long effort to assemble a document on optimal protocols and best practices for genitourinary application of lasers and energy-based devices. The document, published soon after the ASLMS meeting in Lasers in Medicine and Surgery, includes a table that lists the current Food and Drug Administration approval status of devices in genitourinary applications, as well as individual sections dedicated to fractional lasers, radiofrequency (RF) devices, and high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology. It concludes with a section on the current status of clearances and future pathways.

“The work we did was exhaustive,” said Dr. Alexiades, who is also founder and director of Dermatology & Laser Surgery Center of New York. “We went through all the clinical trial data and compiled the parameters that, as a consensus, we agree are best practices for each technology for which we had rigorous published data.”

The document contains a brief background on the history of the devices used for genitourinary issues and it addresses core topics for each technology, such as conditions treated, contraindications, preoperative physical assessment and preparation, perioperative protocols, and postoperative care.

Contraindications to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices are numerous and include use of an intrauterine device, active urinary tract or genital infection, vaginal bleeding, current pregnancy, active or recent malignancy, having an electrical implant anywhere in the body, significant concurrent illness, and an anticoagulative or thromboembolic condition or taking anticoagulant medications 1 week prior to the procedure. Another condition to screen for is advanced prolapse, which was considered a contraindication in all clinical trials, she added. “It’s important that you’re able to do the speculum exam and stage the prolapse” so that a patient with this contraindication is not treated.

Dr. Alexiades shared the following highlights from the document’s section related to the use of fractional CO2 lasers:

Preoperative management. Schedule the treatment one week after the patient’s menstrual period. Patients should avoid blood thinners for 7 days and avoid intercourse the night before the procedure. Reschedule in the case of fever, chills, or vaginal bleeding or discharge.

Preoperative physical exam and testing. A normal speculum exam and a recent negative PAP smear are required. For those of child-bearing potential, a pregnancy test is warranted. Obtain written and verbal consent, including discussion of all treatment options, risks, and benefits. No topical or local anesthesia is necessary internally. “Externally, we sometimes apply topical lidocaine gel, but I have found that’s not necessary in most cases,” Dr. Alexiades said. “The treatment is so quick.”

Peri-operative management. In general, device settings are provided by the manufacturer. “For most of the studies that had successful outcomes and no adverse events, researchers adhered to the mild or moderate settings on the technology,” she said. Energy settings were between 15 and 30 watts, delivered at a laser fluence of about 250-300 mJ/cm2 with a spacing of microbeams 1 mm apart. Typically, three treatments are done at 1-month intervals and maintenance treatments are recommended at 6 and 12 months based on duration of the outcomes.

Vulvovaginal postoperative management. A 3-day recovery time is recommended with avoidance of intercourse during this period, because “re-epithelialization is usually complete in 3 days, so we want to give the opportunity for the lining to heal prior to introducing any friction, Dr. Alexiades said.” Rarely, spotting or discharge may occur and there should be no discomfort. “Any severe discomfort or burning may potentially signify infection and should prompt evaluation and possibly vaginal cultures. The patient can shower, but we recommend avoiding seated baths to decrease any introduction of infectious agents.”

Patients should be followed up monthly until three treatments are completed, and a maintenance treatment is considered appropriate between 6 and 12 months. “I do recommend doing a 1-month follow-up following the final treatment, unless it’s a patient who has already had a series of three treatments and is coming in for maintenance,” she said.

In a study from her own practice, Dr. Alexiades evaluated a series of three fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and vagina with a 1-year follow-up in postmenopausal patients. She used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to assess changes in vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, vaginal pH, epithelial integrity, and moisture. She and her colleagues discovered that there was improvement in every VHI category after treatment and during the follow-up interval up to 6 months.

“Between 6 and 12 months, we started to see a return a bit toward baseline on all of these parameters,” she said. “The serendipitous discovery that I made during the course of that study was that early intervention improves outcomes. I observed that the younger, most recently postmenopausal cohort seemed to attain normal or near normal VHI quicker than the more extended postmenopausal cohorts.”

In an editorial published in 2020, Dr. Alexiades reviewed the effects of fractional CO2 laser treatment of vulvar skin on vaginal pH and referred to a study she conducted that found that the mean baseline pH pretreatment was 6.32 in the cohort of postmenopausal patients, and was reduced after 3 treatments. “Postmenopausally, the normal acidic pH becomes alkaline,” she said. But she did not expect to see an additional reduction in pH following the treatment out to 6 months. “This indicates that, whatever the wound healing and other restorative effects of these devices are, they seem to continue out to 6 months, at which point it turns around and moves toward baseline [levels].”

Dr. Alexiades highlighted two published meta-analyses of studies related to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices. One included 59 studies of 3,609 women treated for vaginal rejuvenation using either radiofrequency or fractional ablative laser therapy. The studies reported improvements in symptoms of GSM/VVA and sexual function, high patient satisfaction, with minor adverse events, including treatment-associated vaginal swelling or vaginal discharge.

“Further research needs to be completed to determine which specific pathologies can be treated, if maintenance treatment is necessary, and long-term safety concerns,” the authors concluded.

In another review, researchers analyzed 64 studies related to vaginal laser therapy for GSM. Of these, 47 were before and after studies without a control group, 10 were controlled intervention studies, and 7 were observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Vaginal laser treatment “seems to improve scores on the visual analogue scale, Female Sexual Function Index, and the Vaginal Health Index over the short term,” the authors wrote. “Safety outcomes are underreported and short term. Further well-designed clinical trials with sham-laser control groups and evaluating objective variables are needed to provide the best evidence on efficacy.”

“Lasers and energy-based devices are now considered alternative therapeutic modalities for genitourinary conditions,” Dr. Alexiades concluded. “The shortcomings in the literature with respect to lasers and device treatments demonstrate the need for the consensus on best practices and protocols.”

During a separate presentation at the meeting, Michael Gold, MD, highlighted data from Grand View Research, a market research database, which estimated that the global women’s health and wellness market is valued at more than $31 billion globally and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 4.8% from 2022 to 2030.

“Sales of women’s health energy-based devices continue to grow as new technologies are developed,” said Dr. Gold, a Nashville, Tenn.–based dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. “Evolving societal norms have made discussions about feminine health issues acceptable. Suffering in silence is no longer necessary or advocated.”

Dr. Alexiades disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela Lasers, Lumenis, Allergan/AbbVie, InMode, and Endymed. She is also the founder and CEO of Macrene Actives. Dr. Gold disclosed that he is a consultant to and/or an investigator and a speaker for Joylux, InMode, and Alma Lasers.

PHOENIX –

“Even a cursory review of PubMed today yields over 100,000 results” on this topic, Macrene R. Alexiades, MD, PhD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Add to that radiofrequency and various diagnoses, the number of publications has skyrocketed, particularly over the last 10 years.”

What has been missing from this hot research topic all these years, she continued, is that no one has distilled this pile of data into a practical guide for office-based clinicians who use lasers and energy-based devices for genitourinary conditions – until now. Working with experts in gynecology and urogynecology, Dr. Alexiades spearheaded a 2-year-long effort to assemble a document on optimal protocols and best practices for genitourinary application of lasers and energy-based devices. The document, published soon after the ASLMS meeting in Lasers in Medicine and Surgery, includes a table that lists the current Food and Drug Administration approval status of devices in genitourinary applications, as well as individual sections dedicated to fractional lasers, radiofrequency (RF) devices, and high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology. It concludes with a section on the current status of clearances and future pathways.

“The work we did was exhaustive,” said Dr. Alexiades, who is also founder and director of Dermatology & Laser Surgery Center of New York. “We went through all the clinical trial data and compiled the parameters that, as a consensus, we agree are best practices for each technology for which we had rigorous published data.”

The document contains a brief background on the history of the devices used for genitourinary issues and it addresses core topics for each technology, such as conditions treated, contraindications, preoperative physical assessment and preparation, perioperative protocols, and postoperative care.

Contraindications to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices are numerous and include use of an intrauterine device, active urinary tract or genital infection, vaginal bleeding, current pregnancy, active or recent malignancy, having an electrical implant anywhere in the body, significant concurrent illness, and an anticoagulative or thromboembolic condition or taking anticoagulant medications 1 week prior to the procedure. Another condition to screen for is advanced prolapse, which was considered a contraindication in all clinical trials, she added. “It’s important that you’re able to do the speculum exam and stage the prolapse” so that a patient with this contraindication is not treated.

Dr. Alexiades shared the following highlights from the document’s section related to the use of fractional CO2 lasers:

Preoperative management. Schedule the treatment one week after the patient’s menstrual period. Patients should avoid blood thinners for 7 days and avoid intercourse the night before the procedure. Reschedule in the case of fever, chills, or vaginal bleeding or discharge.

Preoperative physical exam and testing. A normal speculum exam and a recent negative PAP smear are required. For those of child-bearing potential, a pregnancy test is warranted. Obtain written and verbal consent, including discussion of all treatment options, risks, and benefits. No topical or local anesthesia is necessary internally. “Externally, we sometimes apply topical lidocaine gel, but I have found that’s not necessary in most cases,” Dr. Alexiades said. “The treatment is so quick.”

Peri-operative management. In general, device settings are provided by the manufacturer. “For most of the studies that had successful outcomes and no adverse events, researchers adhered to the mild or moderate settings on the technology,” she said. Energy settings were between 15 and 30 watts, delivered at a laser fluence of about 250-300 mJ/cm2 with a spacing of microbeams 1 mm apart. Typically, three treatments are done at 1-month intervals and maintenance treatments are recommended at 6 and 12 months based on duration of the outcomes.

Vulvovaginal postoperative management. A 3-day recovery time is recommended with avoidance of intercourse during this period, because “re-epithelialization is usually complete in 3 days, so we want to give the opportunity for the lining to heal prior to introducing any friction, Dr. Alexiades said.” Rarely, spotting or discharge may occur and there should be no discomfort. “Any severe discomfort or burning may potentially signify infection and should prompt evaluation and possibly vaginal cultures. The patient can shower, but we recommend avoiding seated baths to decrease any introduction of infectious agents.”

Patients should be followed up monthly until three treatments are completed, and a maintenance treatment is considered appropriate between 6 and 12 months. “I do recommend doing a 1-month follow-up following the final treatment, unless it’s a patient who has already had a series of three treatments and is coming in for maintenance,” she said.

In a study from her own practice, Dr. Alexiades evaluated a series of three fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and vagina with a 1-year follow-up in postmenopausal patients. She used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to assess changes in vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, vaginal pH, epithelial integrity, and moisture. She and her colleagues discovered that there was improvement in every VHI category after treatment and during the follow-up interval up to 6 months.

“Between 6 and 12 months, we started to see a return a bit toward baseline on all of these parameters,” she said. “The serendipitous discovery that I made during the course of that study was that early intervention improves outcomes. I observed that the younger, most recently postmenopausal cohort seemed to attain normal or near normal VHI quicker than the more extended postmenopausal cohorts.”

In an editorial published in 2020, Dr. Alexiades reviewed the effects of fractional CO2 laser treatment of vulvar skin on vaginal pH and referred to a study she conducted that found that the mean baseline pH pretreatment was 6.32 in the cohort of postmenopausal patients, and was reduced after 3 treatments. “Postmenopausally, the normal acidic pH becomes alkaline,” she said. But she did not expect to see an additional reduction in pH following the treatment out to 6 months. “This indicates that, whatever the wound healing and other restorative effects of these devices are, they seem to continue out to 6 months, at which point it turns around and moves toward baseline [levels].”

Dr. Alexiades highlighted two published meta-analyses of studies related to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices. One included 59 studies of 3,609 women treated for vaginal rejuvenation using either radiofrequency or fractional ablative laser therapy. The studies reported improvements in symptoms of GSM/VVA and sexual function, high patient satisfaction, with minor adverse events, including treatment-associated vaginal swelling or vaginal discharge.

“Further research needs to be completed to determine which specific pathologies can be treated, if maintenance treatment is necessary, and long-term safety concerns,” the authors concluded.

In another review, researchers analyzed 64 studies related to vaginal laser therapy for GSM. Of these, 47 were before and after studies without a control group, 10 were controlled intervention studies, and 7 were observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Vaginal laser treatment “seems to improve scores on the visual analogue scale, Female Sexual Function Index, and the Vaginal Health Index over the short term,” the authors wrote. “Safety outcomes are underreported and short term. Further well-designed clinical trials with sham-laser control groups and evaluating objective variables are needed to provide the best evidence on efficacy.”

“Lasers and energy-based devices are now considered alternative therapeutic modalities for genitourinary conditions,” Dr. Alexiades concluded. “The shortcomings in the literature with respect to lasers and device treatments demonstrate the need for the consensus on best practices and protocols.”

During a separate presentation at the meeting, Michael Gold, MD, highlighted data from Grand View Research, a market research database, which estimated that the global women’s health and wellness market is valued at more than $31 billion globally and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 4.8% from 2022 to 2030.

“Sales of women’s health energy-based devices continue to grow as new technologies are developed,” said Dr. Gold, a Nashville, Tenn.–based dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. “Evolving societal norms have made discussions about feminine health issues acceptable. Suffering in silence is no longer necessary or advocated.”

Dr. Alexiades disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela Lasers, Lumenis, Allergan/AbbVie, InMode, and Endymed. She is also the founder and CEO of Macrene Actives. Dr. Gold disclosed that he is a consultant to and/or an investigator and a speaker for Joylux, InMode, and Alma Lasers.

PHOENIX –

“Even a cursory review of PubMed today yields over 100,000 results” on this topic, Macrene R. Alexiades, MD, PhD, associate clinical professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Add to that radiofrequency and various diagnoses, the number of publications has skyrocketed, particularly over the last 10 years.”

What has been missing from this hot research topic all these years, she continued, is that no one has distilled this pile of data into a practical guide for office-based clinicians who use lasers and energy-based devices for genitourinary conditions – until now. Working with experts in gynecology and urogynecology, Dr. Alexiades spearheaded a 2-year-long effort to assemble a document on optimal protocols and best practices for genitourinary application of lasers and energy-based devices. The document, published soon after the ASLMS meeting in Lasers in Medicine and Surgery, includes a table that lists the current Food and Drug Administration approval status of devices in genitourinary applications, as well as individual sections dedicated to fractional lasers, radiofrequency (RF) devices, and high-intensity focused electromagnetic technology. It concludes with a section on the current status of clearances and future pathways.

“The work we did was exhaustive,” said Dr. Alexiades, who is also founder and director of Dermatology & Laser Surgery Center of New York. “We went through all the clinical trial data and compiled the parameters that, as a consensus, we agree are best practices for each technology for which we had rigorous published data.”

The document contains a brief background on the history of the devices used for genitourinary issues and it addresses core topics for each technology, such as conditions treated, contraindications, preoperative physical assessment and preparation, perioperative protocols, and postoperative care.

Contraindications to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices are numerous and include use of an intrauterine device, active urinary tract or genital infection, vaginal bleeding, current pregnancy, active or recent malignancy, having an electrical implant anywhere in the body, significant concurrent illness, and an anticoagulative or thromboembolic condition or taking anticoagulant medications 1 week prior to the procedure. Another condition to screen for is advanced prolapse, which was considered a contraindication in all clinical trials, she added. “It’s important that you’re able to do the speculum exam and stage the prolapse” so that a patient with this contraindication is not treated.

Dr. Alexiades shared the following highlights from the document’s section related to the use of fractional CO2 lasers:

Preoperative management. Schedule the treatment one week after the patient’s menstrual period. Patients should avoid blood thinners for 7 days and avoid intercourse the night before the procedure. Reschedule in the case of fever, chills, or vaginal bleeding or discharge.

Preoperative physical exam and testing. A normal speculum exam and a recent negative PAP smear are required. For those of child-bearing potential, a pregnancy test is warranted. Obtain written and verbal consent, including discussion of all treatment options, risks, and benefits. No topical or local anesthesia is necessary internally. “Externally, we sometimes apply topical lidocaine gel, but I have found that’s not necessary in most cases,” Dr. Alexiades said. “The treatment is so quick.”

Peri-operative management. In general, device settings are provided by the manufacturer. “For most of the studies that had successful outcomes and no adverse events, researchers adhered to the mild or moderate settings on the technology,” she said. Energy settings were between 15 and 30 watts, delivered at a laser fluence of about 250-300 mJ/cm2 with a spacing of microbeams 1 mm apart. Typically, three treatments are done at 1-month intervals and maintenance treatments are recommended at 6 and 12 months based on duration of the outcomes.

Vulvovaginal postoperative management. A 3-day recovery time is recommended with avoidance of intercourse during this period, because “re-epithelialization is usually complete in 3 days, so we want to give the opportunity for the lining to heal prior to introducing any friction, Dr. Alexiades said.” Rarely, spotting or discharge may occur and there should be no discomfort. “Any severe discomfort or burning may potentially signify infection and should prompt evaluation and possibly vaginal cultures. The patient can shower, but we recommend avoiding seated baths to decrease any introduction of infectious agents.”

Patients should be followed up monthly until three treatments are completed, and a maintenance treatment is considered appropriate between 6 and 12 months. “I do recommend doing a 1-month follow-up following the final treatment, unless it’s a patient who has already had a series of three treatments and is coming in for maintenance,” she said.

In a study from her own practice, Dr. Alexiades evaluated a series of three fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and vagina with a 1-year follow-up in postmenopausal patients. She used the Vaginal Health Index (VHI) to assess changes in vaginal elasticity, fluid volume, vaginal pH, epithelial integrity, and moisture. She and her colleagues discovered that there was improvement in every VHI category after treatment and during the follow-up interval up to 6 months.

“Between 6 and 12 months, we started to see a return a bit toward baseline on all of these parameters,” she said. “The serendipitous discovery that I made during the course of that study was that early intervention improves outcomes. I observed that the younger, most recently postmenopausal cohort seemed to attain normal or near normal VHI quicker than the more extended postmenopausal cohorts.”

In an editorial published in 2020, Dr. Alexiades reviewed the effects of fractional CO2 laser treatment of vulvar skin on vaginal pH and referred to a study she conducted that found that the mean baseline pH pretreatment was 6.32 in the cohort of postmenopausal patients, and was reduced after 3 treatments. “Postmenopausally, the normal acidic pH becomes alkaline,” she said. But she did not expect to see an additional reduction in pH following the treatment out to 6 months. “This indicates that, whatever the wound healing and other restorative effects of these devices are, they seem to continue out to 6 months, at which point it turns around and moves toward baseline [levels].”

Dr. Alexiades highlighted two published meta-analyses of studies related to the genitourinary use of lasers and energy-based devices. One included 59 studies of 3,609 women treated for vaginal rejuvenation using either radiofrequency or fractional ablative laser therapy. The studies reported improvements in symptoms of GSM/VVA and sexual function, high patient satisfaction, with minor adverse events, including treatment-associated vaginal swelling or vaginal discharge.

“Further research needs to be completed to determine which specific pathologies can be treated, if maintenance treatment is necessary, and long-term safety concerns,” the authors concluded.

In another review, researchers analyzed 64 studies related to vaginal laser therapy for GSM. Of these, 47 were before and after studies without a control group, 10 were controlled intervention studies, and 7 were observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Vaginal laser treatment “seems to improve scores on the visual analogue scale, Female Sexual Function Index, and the Vaginal Health Index over the short term,” the authors wrote. “Safety outcomes are underreported and short term. Further well-designed clinical trials with sham-laser control groups and evaluating objective variables are needed to provide the best evidence on efficacy.”

“Lasers and energy-based devices are now considered alternative therapeutic modalities for genitourinary conditions,” Dr. Alexiades concluded. “The shortcomings in the literature with respect to lasers and device treatments demonstrate the need for the consensus on best practices and protocols.”

During a separate presentation at the meeting, Michael Gold, MD, highlighted data from Grand View Research, a market research database, which estimated that the global women’s health and wellness market is valued at more than $31 billion globally and is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 4.8% from 2022 to 2030.

“Sales of women’s health energy-based devices continue to grow as new technologies are developed,” said Dr. Gold, a Nashville, Tenn.–based dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. “Evolving societal norms have made discussions about feminine health issues acceptable. Suffering in silence is no longer necessary or advocated.”

Dr. Alexiades disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela Lasers, Lumenis, Allergan/AbbVie, InMode, and Endymed. She is also the founder and CEO of Macrene Actives. Dr. Gold disclosed that he is a consultant to and/or an investigator and a speaker for Joylux, InMode, and Alma Lasers.

AT ASLMS 2023

Wireless neurostimulation safe for urge incontinence

CHICAGO – , according to new findings presented at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

As many as half of women in the United States aged 60 and older will experience urinary incontinence. Of those, roughly one in four experience urge urinary incontinence, marked by a sudden need to void that cannot be fully suppressed.

Researchers studied the benefits of the RENOVA iStim (BlueWind Medical) implantable tibial neuromodulation system for the treatment of overactive bladder in the OASIS trial.

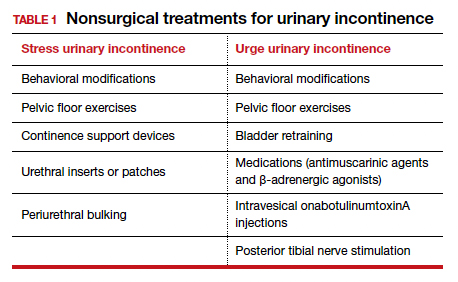

Study investigator Roger R. Dmochowski, MD, MMHC, professor of urology and surgery and associate surgeon-in-chief at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said the first-line treatment of urinary incontinence is lifestyle changes to retrain the bladder or physical therapy, including pelvic floor and Kegel exercises, per AUA guidelines. He said the success rate is about 30% and is not sustained. Second-line treatments include medications, which most (60%) patients stop taking by 6 months.

More than three-quarters of the 151 women who received the device responded to therapy at 1 year, and 84.6% of the patients showed improvement, according to Dr. Dmochowski.

The participants (mean age, 58.8) demonstrated a mean baseline of 4.8 urge incidents per day (standard deviation, 2.9) and 10 voids/day (SD, 3.3). No device or procedure-related serious adverse events were reported at 12 months. Half of the women no longer had symptoms on three consecutive days, Dr. Dmochowski said.

Because urge urinary incontinence is a chronic condition, “treatment with the BlueWind System will be ongoing, with frequency determined based on the patient’s response,” Dr. Dmochowski said. “The patient is then empowered to control when and where they perform therapy.”

“The device is activated by the external wearable. It’s like an on-off switch. It has a receiver within it that basically has the capacity to be turned on and off by the wearable, which is the control device. The device is in an off-position until the wearable is applied,” he said.

He said the device should be worn twice a day for about 20 minutes, with many patients using it less.

Only one implanted tibial neuromodulation device has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration – eCOIN (Valencia Technologies). The RENOVA iStim is an investigational device under review by the FDA, Dr. Dmochowski said.

In installing the device, Dr. Dmochowski said urologists use a subfascial technique to enable direct visualization of the tibial nerve and suture fixation that increases the possibility of a predictable placement. Patients use an external wearable, which activates the implant, without concern for battery longevity or replacement.

“This therapy is not associated with any adverse effects and may be beneficial for patients who do not respond to other treatments for OAB such as medications or Botox,” said Carol E. Bretschneider, MD, a urogynecologic and pelvic surgeon at Northwestern Medicine Central DuPage Hospital, outside Chicago. “Neurostimulators can be a great advanced therapy option for patients who do not respond to more conservative treatments or cannot take or tolerate a medication.”

The devices do not stimulate or strengthen muscles but act by modulating the reflexes that influence the bladder, sphincter, and pelvic floor, added Dr. Bretschneider, who was not involved in the study.

Other treatments for urge incontinence can include acupuncture, or percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, to target the posterior tibial nerve in the ankle, which shares the same nerve root that controls the bladder, according to Aron Liaw, MD, a reconstructive urologist and assistant professor of urology at Wayne State University in Detroit. This treatment has been shown to be at least as effective as available medications, but with fewer side effects, he said.

But regular stimulation is necessary to achieve and preserve efficacy, he said.

Dr. Liaw, who was not involved in the neuromodulation study, said the benefits of a device like Renova iStim are that implantation is relatively easy and can be performed in office settings, and patients can then treat themselves at home. However, because the new study did not compare the device to other treatments or a placebo device, its relative benefits are unclear, he said,

Other treatments for urge urinary incontinence, such as bladder Botox and sacral neuromodulation, also are minimally invasive and have proven benefit, “so a device like this could well be less effective with little other advantage,” he said.

“Lifestyle changes can make a big difference, but making big lifestyle changes is not always easy,” added Dr. Liaw. “I have found neuromodulation [to be] very effective, especially in conjunction with lifestyle changes.”

BlueWind Medical funds the OASIS trial. Dr. Dmochowski reported he received no grants nor has any relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bretschneider and Dr. Liaw report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CHICAGO – , according to new findings presented at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Urological Association.

As many as half of women in the United States aged 60 and older will experience urinary incontinence. Of those, roughly one in four experience urge urinary incontinence, marked by a sudden need to void that cannot be fully suppressed.

Researchers studied the benefits of the RENOVA iStim (BlueWind Medical) implantable tibial neuromodulation system for the treatment of overactive bladder in the OASIS trial.

Study investigator Roger R. Dmochowski, MD, MMHC, professor of urology and surgery and associate surgeon-in-chief at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said the first-line treatment of urinary incontinence is lifestyle changes to retrain the bladder or physical therapy, including pelvic floor and Kegel exercises, per AUA guidelines. He said the success rate is about 30% and is not sustained. Second-line treatments include medications, which most (60%) patients stop taking by 6 months.

More than three-quarters of the 151 women who received the device responded to therapy at 1 year, and 84.6% of the patients showed improvement, according to Dr. Dmochowski.

The participants (mean age, 58.8) demonstrated a mean baseline of 4.8 urge incidents per day (standard deviation, 2.9) and 10 voids/day (SD, 3.3). No device or procedure-related serious adverse events were reported at 12 months. Half of the women no longer had symptoms on three consecutive days, Dr. Dmochowski said.

Because urge urinary incontinence is a chronic condition, “treatment with the BlueWind System will be ongoing, with frequency determined based on the patient’s response,” Dr. Dmochowski said. “The patient is then empowered to control when and where they perform therapy.”

“The device is activated by the external wearable. It’s like an on-off switch. It has a receiver within it that basically has the capacity to be turned on and off by the wearable, which is the control device. The device is in an off-position until the wearable is applied,” he said.

He said the device should be worn twice a day for about 20 minutes, with many patients using it less.

Only one implanted tibial neuromodulation device has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration – eCOIN (Valencia Technologies). The RENOVA iStim is an investigational device under review by the FDA, Dr. Dmochowski said.

In installing the device, Dr. Dmochowski said urologists use a subfascial technique to enable direct visualization of the tibial nerve and suture fixation that increases the possibility of a predictable placement. Patients use an external wearable, which activates the implant, without concern for battery longevity or replacement.

“This therapy is not associated with any adverse effects and may be beneficial for patients who do not respond to other treatments for OAB such as medications or Botox,” said Carol E. Bretschneider, MD, a urogynecologic and pelvic surgeon at Northwestern Medicine Central DuPage Hospital, outside Chicago. “Neurostimulators can be a great advanced therapy option for patients who do not respond to more conservative treatments or cannot take or tolerate a medication.”

The devices do not stimulate or strengthen muscles but act by modulating the reflexes that influence the bladder, sphincter, and pelvic floor, added Dr. Bretschneider, who was not involved in the study.

Other treatments for urge incontinence can include acupuncture, or percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, to target the posterior tibial nerve in the ankle, which shares the same nerve root that controls the bladder, according to Aron Liaw, MD, a reconstructive urologist and assistant professor of urology at Wayne State University in Detroit. This treatment has been shown to be at least as effective as available medications, but with fewer side effects, he said.

But regular stimulation is necessary to achieve and preserve efficacy, he said.

Dr. Liaw, who was not involved in the neuromodulation study, said the benefits of a device like Renova iStim are that implantation is relatively easy and can be performed in office settings, and patients can then treat themselves at home. However, because the new study did not compare the device to other treatments or a placebo device, its relative benefits are unclear, he said,

Other treatments for urge urinary incontinence, such as bladder Botox and sacral neuromodulation, also are minimally invasive and have proven benefit, “so a device like this could well be less effective with little other advantage,” he said.

“Lifestyle changes can make a big difference, but making big lifestyle changes is not always easy,” added Dr. Liaw. “I have found neuromodulation [to be] very effective, especially in conjunction with lifestyle changes.”

BlueWind Medical funds the OASIS trial. Dr. Dmochowski reported he received no grants nor has any relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bretschneider and Dr. Liaw report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.