User login

New risk score predicts PCI outcomes in octogenarians

PARIS – A fast and simple clinically based scoring system enables physicians to determine the chance of a successful outcome for octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, James Cockburn, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

All six elements of the scoring system are readily available either at the time the very elderly patient presents or at diagnostic angiography, noted Dr. Cockburn of Brighton and Sussex University Hospital in Brighton, England.

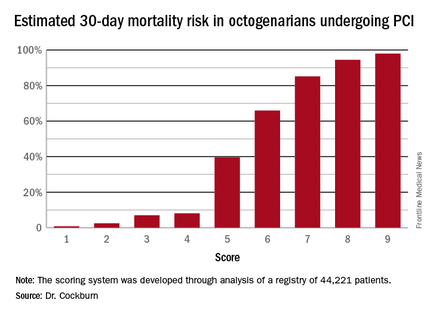

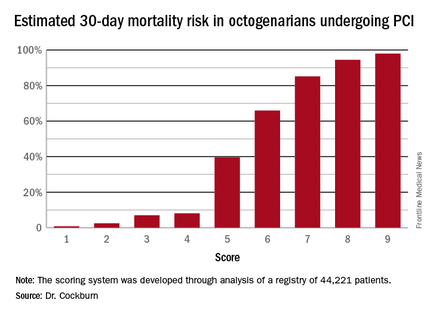

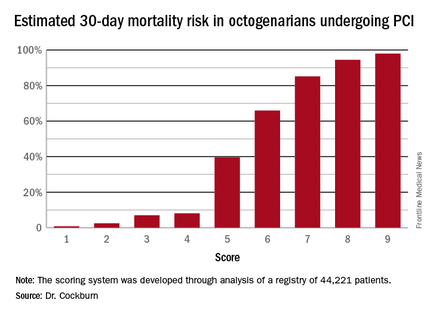

He and his coworkers developed the risk score through analysis of a registry of 44,221 patients aged 80 or older who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The procedural success rate – defined as less than a 30% residual stenosis and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 3 antegrade blood flow – was 92.3%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%. The investigators teased out a set of easily accessible clinical factors associated with 30-day mortality and came up with a novel risk scoring system using a 9-point scale.

The clinical factors and scoring system are as follows:

• Age. 1 point for being 80-89, and 2 points at age 90 or older.

• Indication for PCI. 1 point for unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation MI, 2 points for STEMI, 0 points for other indications.

• Ventilated preprocedure. 1 point if yes.

• Creatinine level above 200 umol/L. 1 point for yes.

• Preprocedural cardiogenic shock. 2 points for yes.

• Poor left ventricular ejection fraction. If less than 30%, 1 point.

Thus, scores can range from 1 to 9. Dr. Cockburn and his coworkers calculated the risk of 30-day mortality for each possible score. They validated the score by performing a receiver operator curve analysis that showed an area under the curve of 0.83, suggestive of relatively high sensitivity and specificity.

A score of 4 or less suggests a very good chance of survival at 30 days. In contrast, a score of 6 was associated with a two in three chance of death by 30 days. And it’s not hard to reach a 6: A patient who is 90 years old (2 points), presents with STEMI (2 points), and is in cardiogenic shock (2 points) is already there. But if a 90-year-old patient presents with unstable angina and none of the other risk factors, that’s a score of 3 points, with an estimated probability of death at 30 days of only 7%, he noted.

Dr. Cockburn stressed that this risk score should not be used to base decisions on whether to take very elderly patients to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. “It enables you to have a useful conversation with relatives in which you can explain that this is a very high-risk intervention, or perhaps a low-risk intervention,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussants were emphatic in their agreement with Dr. Cockburn that this risk score shouldn’t be utilized to decide who does or doesn’t get PCI. One panelist said that what’s really lacking now in clinical practice – and where that huge British registry database could be helpful – is a scoring system that would predict which patients who don’t present in cardiogenic shock are going to develop it post PCI.

Dr. Cockburn reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

PARIS – A fast and simple clinically based scoring system enables physicians to determine the chance of a successful outcome for octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, James Cockburn, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

All six elements of the scoring system are readily available either at the time the very elderly patient presents or at diagnostic angiography, noted Dr. Cockburn of Brighton and Sussex University Hospital in Brighton, England.

He and his coworkers developed the risk score through analysis of a registry of 44,221 patients aged 80 or older who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The procedural success rate – defined as less than a 30% residual stenosis and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 3 antegrade blood flow – was 92.3%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%. The investigators teased out a set of easily accessible clinical factors associated with 30-day mortality and came up with a novel risk scoring system using a 9-point scale.

The clinical factors and scoring system are as follows:

• Age. 1 point for being 80-89, and 2 points at age 90 or older.

• Indication for PCI. 1 point for unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation MI, 2 points for STEMI, 0 points for other indications.

• Ventilated preprocedure. 1 point if yes.

• Creatinine level above 200 umol/L. 1 point for yes.

• Preprocedural cardiogenic shock. 2 points for yes.

• Poor left ventricular ejection fraction. If less than 30%, 1 point.

Thus, scores can range from 1 to 9. Dr. Cockburn and his coworkers calculated the risk of 30-day mortality for each possible score. They validated the score by performing a receiver operator curve analysis that showed an area under the curve of 0.83, suggestive of relatively high sensitivity and specificity.

A score of 4 or less suggests a very good chance of survival at 30 days. In contrast, a score of 6 was associated with a two in three chance of death by 30 days. And it’s not hard to reach a 6: A patient who is 90 years old (2 points), presents with STEMI (2 points), and is in cardiogenic shock (2 points) is already there. But if a 90-year-old patient presents with unstable angina and none of the other risk factors, that’s a score of 3 points, with an estimated probability of death at 30 days of only 7%, he noted.

Dr. Cockburn stressed that this risk score should not be used to base decisions on whether to take very elderly patients to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. “It enables you to have a useful conversation with relatives in which you can explain that this is a very high-risk intervention, or perhaps a low-risk intervention,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussants were emphatic in their agreement with Dr. Cockburn that this risk score shouldn’t be utilized to decide who does or doesn’t get PCI. One panelist said that what’s really lacking now in clinical practice – and where that huge British registry database could be helpful – is a scoring system that would predict which patients who don’t present in cardiogenic shock are going to develop it post PCI.

Dr. Cockburn reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

PARIS – A fast and simple clinically based scoring system enables physicians to determine the chance of a successful outcome for octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, James Cockburn, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

All six elements of the scoring system are readily available either at the time the very elderly patient presents or at diagnostic angiography, noted Dr. Cockburn of Brighton and Sussex University Hospital in Brighton, England.

He and his coworkers developed the risk score through analysis of a registry of 44,221 patients aged 80 or older who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The procedural success rate – defined as less than a 30% residual stenosis and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) 3 antegrade blood flow – was 92.3%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%. The investigators teased out a set of easily accessible clinical factors associated with 30-day mortality and came up with a novel risk scoring system using a 9-point scale.

The clinical factors and scoring system are as follows:

• Age. 1 point for being 80-89, and 2 points at age 90 or older.

• Indication for PCI. 1 point for unstable angina/non–ST segment elevation MI, 2 points for STEMI, 0 points for other indications.

• Ventilated preprocedure. 1 point if yes.

• Creatinine level above 200 umol/L. 1 point for yes.

• Preprocedural cardiogenic shock. 2 points for yes.

• Poor left ventricular ejection fraction. If less than 30%, 1 point.

Thus, scores can range from 1 to 9. Dr. Cockburn and his coworkers calculated the risk of 30-day mortality for each possible score. They validated the score by performing a receiver operator curve analysis that showed an area under the curve of 0.83, suggestive of relatively high sensitivity and specificity.

A score of 4 or less suggests a very good chance of survival at 30 days. In contrast, a score of 6 was associated with a two in three chance of death by 30 days. And it’s not hard to reach a 6: A patient who is 90 years old (2 points), presents with STEMI (2 points), and is in cardiogenic shock (2 points) is already there. But if a 90-year-old patient presents with unstable angina and none of the other risk factors, that’s a score of 3 points, with an estimated probability of death at 30 days of only 7%, he noted.

Dr. Cockburn stressed that this risk score should not be used to base decisions on whether to take very elderly patients to the cardiac catheterization laboratory. “It enables you to have a useful conversation with relatives in which you can explain that this is a very high-risk intervention, or perhaps a low-risk intervention,” according to the cardiologist.

Discussants were emphatic in their agreement with Dr. Cockburn that this risk score shouldn’t be utilized to decide who does or doesn’t get PCI. One panelist said that what’s really lacking now in clinical practice – and where that huge British registry database could be helpful – is a scoring system that would predict which patients who don’t present in cardiogenic shock are going to develop it post PCI.

Dr. Cockburn reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: Six readily obtainable clinical factors can be added up to allow accurate estimates of 30-day mortality risk after PCI.

Major finding: Very elderly patients with a score of 3 out of a possible 9 had an estimated 30-day mortality risk of 7%, while at a score of 5, the risk jumped to 40%, and at 6 to 66%.

Data source: This novel 30-day risk scoring system for octogenarians undergoing PCI was derived from a registry of 44,221 such patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Permanent pacemaker in TAVR: Earlier implantation costs much less

PARIS – When a patient undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement needs a permanent pacemaker, the additional hospital costs are significantly less if the device is implanted within 24 hours post TAVR rather than later, Seth Clancy reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“Not only the need for permanent pacemaker implantation but also the timing of the procedure as well as the management and monitoring of conduction disturbances have important resource use implications for TAVR,” observed Mr. Clancy of Edwards Lifesciences of Irvine, Calif.

He presented an economic analysis of all 12,148 TAVR hospitalizations included in the Medicare database for 2014. A key finding: The mean cost of TAVR hospitalizations with no permanent pacemaker implantation was $63,136, while for the 12% of TAVRs that did include permanent pacemaker implantation, the mean cost shot up to $80,441, for a difference of $17,305.

The additional cost of putting in a permanent pacemaker included nearly $8,000 for supplies, more than $2,600 for additional time in the operating room and/or catheterization laboratory, and in excess of $2,100 worth of extra ICU or cardiac care unit time.

Patients who received a permanent pacemaker during their TAVR hospitalization spent an average of 2.3 days longer in the hospital than the mean 6.6 days for patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker.

Drilling down further into the data, Mr. Clancy found that 41% of permanent pacemakers implanted during hospitalization for TAVR went in within 24 hours of the TAVR procedure. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for differences in patient demographics, comorbid conditions, and complications, those patients generated an average of $9,843 more in hospital costs than patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker during their TAVR hospitalization. However, patients who received a permanent pacemaker more than 24 hours after TAVR cost an average of $17,681 more and had a 2.72-day longer stay than patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker.

The need for a permanent pacemaker is a common complication following TAVR. This has been a sticking point for many cardiothoracic surgeons, who note that rates of permanent pacemaker implantation following surgical aortic valve replacement are far lower. Still, rates in TAVR patients have come down over time with advances in valve technology. Currently, permanent pacemaker implantation rates in TAVR patients are 5%-25%, depending upon the valve system, according to Mr. Clancy.

Advances in device design and techniques aimed at reducing the permanent pacemaker implantation rate substantially below the 12% figure seen in 2014 have the potential to generate substantial cost savings, he observed.

Session chair Mohammad Abdelghani, MD, of the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam questioned whether the study results are relevant to European practice because of the large differences in health care costs.

Discussant Sonia Petronio, MD, expressed a more fundamental reservation.

“This is a very important subject – and a very dangerous one,” said Dr. Petronio of the University of Pisa (Italy). “It’s easier and less costly for a hospital to encourage increasing early permanent pacemaker implantation because the patient can go home earlier.”

“We don’t want to put in a pacemaker earlier to save money,” agreed Dr. Abdelghani. “This is not a cost-effectiveness analysis, it’s purely a cost analysis. Cost-effectiveness would take into account the long-term clinical outcomes and welfare of the patients. We would like to see that from you next year.”

Mr. Clancy is an employee of Edwards Lifesciences, which funded the study.

PARIS – When a patient undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement needs a permanent pacemaker, the additional hospital costs are significantly less if the device is implanted within 24 hours post TAVR rather than later, Seth Clancy reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“Not only the need for permanent pacemaker implantation but also the timing of the procedure as well as the management and monitoring of conduction disturbances have important resource use implications for TAVR,” observed Mr. Clancy of Edwards Lifesciences of Irvine, Calif.

He presented an economic analysis of all 12,148 TAVR hospitalizations included in the Medicare database for 2014. A key finding: The mean cost of TAVR hospitalizations with no permanent pacemaker implantation was $63,136, while for the 12% of TAVRs that did include permanent pacemaker implantation, the mean cost shot up to $80,441, for a difference of $17,305.

The additional cost of putting in a permanent pacemaker included nearly $8,000 for supplies, more than $2,600 for additional time in the operating room and/or catheterization laboratory, and in excess of $2,100 worth of extra ICU or cardiac care unit time.

Patients who received a permanent pacemaker during their TAVR hospitalization spent an average of 2.3 days longer in the hospital than the mean 6.6 days for patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker.

Drilling down further into the data, Mr. Clancy found that 41% of permanent pacemakers implanted during hospitalization for TAVR went in within 24 hours of the TAVR procedure. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for differences in patient demographics, comorbid conditions, and complications, those patients generated an average of $9,843 more in hospital costs than patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker during their TAVR hospitalization. However, patients who received a permanent pacemaker more than 24 hours after TAVR cost an average of $17,681 more and had a 2.72-day longer stay than patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker.

The need for a permanent pacemaker is a common complication following TAVR. This has been a sticking point for many cardiothoracic surgeons, who note that rates of permanent pacemaker implantation following surgical aortic valve replacement are far lower. Still, rates in TAVR patients have come down over time with advances in valve technology. Currently, permanent pacemaker implantation rates in TAVR patients are 5%-25%, depending upon the valve system, according to Mr. Clancy.

Advances in device design and techniques aimed at reducing the permanent pacemaker implantation rate substantially below the 12% figure seen in 2014 have the potential to generate substantial cost savings, he observed.

Session chair Mohammad Abdelghani, MD, of the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam questioned whether the study results are relevant to European practice because of the large differences in health care costs.

Discussant Sonia Petronio, MD, expressed a more fundamental reservation.

“This is a very important subject – and a very dangerous one,” said Dr. Petronio of the University of Pisa (Italy). “It’s easier and less costly for a hospital to encourage increasing early permanent pacemaker implantation because the patient can go home earlier.”

“We don’t want to put in a pacemaker earlier to save money,” agreed Dr. Abdelghani. “This is not a cost-effectiveness analysis, it’s purely a cost analysis. Cost-effectiveness would take into account the long-term clinical outcomes and welfare of the patients. We would like to see that from you next year.”

Mr. Clancy is an employee of Edwards Lifesciences, which funded the study.

PARIS – When a patient undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement needs a permanent pacemaker, the additional hospital costs are significantly less if the device is implanted within 24 hours post TAVR rather than later, Seth Clancy reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“Not only the need for permanent pacemaker implantation but also the timing of the procedure as well as the management and monitoring of conduction disturbances have important resource use implications for TAVR,” observed Mr. Clancy of Edwards Lifesciences of Irvine, Calif.

He presented an economic analysis of all 12,148 TAVR hospitalizations included in the Medicare database for 2014. A key finding: The mean cost of TAVR hospitalizations with no permanent pacemaker implantation was $63,136, while for the 12% of TAVRs that did include permanent pacemaker implantation, the mean cost shot up to $80,441, for a difference of $17,305.

The additional cost of putting in a permanent pacemaker included nearly $8,000 for supplies, more than $2,600 for additional time in the operating room and/or catheterization laboratory, and in excess of $2,100 worth of extra ICU or cardiac care unit time.

Patients who received a permanent pacemaker during their TAVR hospitalization spent an average of 2.3 days longer in the hospital than the mean 6.6 days for patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker.

Drilling down further into the data, Mr. Clancy found that 41% of permanent pacemakers implanted during hospitalization for TAVR went in within 24 hours of the TAVR procedure. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for differences in patient demographics, comorbid conditions, and complications, those patients generated an average of $9,843 more in hospital costs than patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker during their TAVR hospitalization. However, patients who received a permanent pacemaker more than 24 hours after TAVR cost an average of $17,681 more and had a 2.72-day longer stay than patients who didn’t get a permanent pacemaker.

The need for a permanent pacemaker is a common complication following TAVR. This has been a sticking point for many cardiothoracic surgeons, who note that rates of permanent pacemaker implantation following surgical aortic valve replacement are far lower. Still, rates in TAVR patients have come down over time with advances in valve technology. Currently, permanent pacemaker implantation rates in TAVR patients are 5%-25%, depending upon the valve system, according to Mr. Clancy.

Advances in device design and techniques aimed at reducing the permanent pacemaker implantation rate substantially below the 12% figure seen in 2014 have the potential to generate substantial cost savings, he observed.

Session chair Mohammad Abdelghani, MD, of the Academic Medical Center at Amsterdam questioned whether the study results are relevant to European practice because of the large differences in health care costs.

Discussant Sonia Petronio, MD, expressed a more fundamental reservation.

“This is a very important subject – and a very dangerous one,” said Dr. Petronio of the University of Pisa (Italy). “It’s easier and less costly for a hospital to encourage increasing early permanent pacemaker implantation because the patient can go home earlier.”

“We don’t want to put in a pacemaker earlier to save money,” agreed Dr. Abdelghani. “This is not a cost-effectiveness analysis, it’s purely a cost analysis. Cost-effectiveness would take into account the long-term clinical outcomes and welfare of the patients. We would like to see that from you next year.”

Mr. Clancy is an employee of Edwards Lifesciences, which funded the study.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: The incremental cost of permanent pacemaker implantation more than 24 hours after transcatheter aortic valve replacement is almost twice as great as if the pacemaker goes in within 24 hours.

Major finding: The mean cost of hospitalization for transcatheter aortic valve replacement without permanent pacemaker implication in Medicare patients in 2014 was $63,136, compared with $80,441 if they needed a pacemaker.

Data source: This was a retrospective study of the health care costs and lengths of stay for all 12,148 hospitalizations for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the Medicare inpatient database for 2014.

Disclosures: The presenter is an employee of Edwards Lifesciences, which funded the study.

Resident transitions increase inpatients’ risk of death

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have a change in the medical residents responsible for their care are more likely to die, finds a retrospective cohort study of roughly a quarter million discharges from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

A monthly change in resident care was associated with 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death during the hospital stay and after discharge, investigators reported in a poster discussion session and press briefing at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Analyses suggested that such transitions accounted for 718 additional deaths in the hospital alone during the 6-year study period.

“These are very strong findings,” said Dr. Joshua L. Denson, a fellow in the divisions of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The study results represent an important initial step in bringing the problem to light, he said. “Handoffs shift to shift have been looked at, but not this end-of-month, more permanent switching, which I think is a much more substantial transition in care.”

The factors driving the increased mortality are unclear, according to Dr. Denson; however, “when you go on to a new service [as a resident] ... you are now responsible for 20 new people all of a sudden that night.” Therefore, these transitions can be a hectic time characterized by reduced communication and inefficient discharges. In addition, the incoming residents lack familiarity with their new patients’ particulars.

“The handoffs are definitely not preventable, so this is something that has to be dealt with,” he maintained. The study’s findings hint at several possible areas for improvement.

None of the 10 residency programs surveyed provided formal education for monthly resident handoffs, focusing instead on handoffs at shift changes, and most programs lacked a standard procedure, with just one requiring that the handoff be done in person. The programs also varied greatly in their staggering of handoffs – separating transitions of interns (first-year residents) and higher-level residents by at least a few days – to minimize impact.

Despite the absence of outcomes data in this area, some hospitals are forging ahead with their own interventions intended to smooth care transitions, Dr. Denson reported. “In at least two hospitals that I’ve worked in, they are implementing what is called a warm handoff,” he explained. “Basically, a resident from the prior rotation comes the next day and rounds with the new team so he can tell them, ‘Oh, this guy looks a little worse today, you may want to watch him,’ or ‘He looks a little better.’ ”

In the study, conducted while Dr. Denson was chief resident at the NYU School of Medicine, he and his colleagues analyzed data from 10 university-affiliated Veterans Affairs hospitals and internal medicine residency programs that provided their residents’ schedules. Analyses were based on a total of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients between July 2008 and June 2014.

Hospitalized patients were categorized as having a transition in resident care if they were admitted before the date of an end-of-month house staff transition in care and were discharged in the week after it.

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had a transition of care – whether of intern only, resident only, or both – had significantly higher odds of inpatient mortality and of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality, compared with counterparts who did not have the corresponding transition of care.

In adjusted analyses, patients who had an intern transition still had higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.14). In addition, patients had persistently elevated odds of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality if they had an intern transition (odds ratios, 1.20 and 1.17, respectively), a resident transition (1.15 and 1.14), or both (1.10 and 1.09).

The findings “suggest possibly a level-of-training effect to these transitions, as it’s the most inexperienced people that have the higher rate of mortality,” noted Dr. Denson, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. “Interns, being the first-years, tend to carry the bulk of the work in most hospitals, which is an interesting paradigm in our organization. And that may be a good explanation for why we are seeing this.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have a change in the medical residents responsible for their care are more likely to die, finds a retrospective cohort study of roughly a quarter million discharges from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

A monthly change in resident care was associated with 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death during the hospital stay and after discharge, investigators reported in a poster discussion session and press briefing at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Analyses suggested that such transitions accounted for 718 additional deaths in the hospital alone during the 6-year study period.

“These are very strong findings,” said Dr. Joshua L. Denson, a fellow in the divisions of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The study results represent an important initial step in bringing the problem to light, he said. “Handoffs shift to shift have been looked at, but not this end-of-month, more permanent switching, which I think is a much more substantial transition in care.”

The factors driving the increased mortality are unclear, according to Dr. Denson; however, “when you go on to a new service [as a resident] ... you are now responsible for 20 new people all of a sudden that night.” Therefore, these transitions can be a hectic time characterized by reduced communication and inefficient discharges. In addition, the incoming residents lack familiarity with their new patients’ particulars.

“The handoffs are definitely not preventable, so this is something that has to be dealt with,” he maintained. The study’s findings hint at several possible areas for improvement.

None of the 10 residency programs surveyed provided formal education for monthly resident handoffs, focusing instead on handoffs at shift changes, and most programs lacked a standard procedure, with just one requiring that the handoff be done in person. The programs also varied greatly in their staggering of handoffs – separating transitions of interns (first-year residents) and higher-level residents by at least a few days – to minimize impact.

Despite the absence of outcomes data in this area, some hospitals are forging ahead with their own interventions intended to smooth care transitions, Dr. Denson reported. “In at least two hospitals that I’ve worked in, they are implementing what is called a warm handoff,” he explained. “Basically, a resident from the prior rotation comes the next day and rounds with the new team so he can tell them, ‘Oh, this guy looks a little worse today, you may want to watch him,’ or ‘He looks a little better.’ ”

In the study, conducted while Dr. Denson was chief resident at the NYU School of Medicine, he and his colleagues analyzed data from 10 university-affiliated Veterans Affairs hospitals and internal medicine residency programs that provided their residents’ schedules. Analyses were based on a total of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients between July 2008 and June 2014.

Hospitalized patients were categorized as having a transition in resident care if they were admitted before the date of an end-of-month house staff transition in care and were discharged in the week after it.

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had a transition of care – whether of intern only, resident only, or both – had significantly higher odds of inpatient mortality and of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality, compared with counterparts who did not have the corresponding transition of care.

In adjusted analyses, patients who had an intern transition still had higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.14). In addition, patients had persistently elevated odds of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality if they had an intern transition (odds ratios, 1.20 and 1.17, respectively), a resident transition (1.15 and 1.14), or both (1.10 and 1.09).

The findings “suggest possibly a level-of-training effect to these transitions, as it’s the most inexperienced people that have the higher rate of mortality,” noted Dr. Denson, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. “Interns, being the first-years, tend to carry the bulk of the work in most hospitals, which is an interesting paradigm in our organization. And that may be a good explanation for why we are seeing this.”

SAN FRANCISCO – Hospitalized patients who have a change in the medical residents responsible for their care are more likely to die, finds a retrospective cohort study of roughly a quarter million discharges from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

A monthly change in resident care was associated with 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death during the hospital stay and after discharge, investigators reported in a poster discussion session and press briefing at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. Analyses suggested that such transitions accounted for 718 additional deaths in the hospital alone during the 6-year study period.

“These are very strong findings,” said Dr. Joshua L. Denson, a fellow in the divisions of pulmonary sciences and critical care medicine at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

The study results represent an important initial step in bringing the problem to light, he said. “Handoffs shift to shift have been looked at, but not this end-of-month, more permanent switching, which I think is a much more substantial transition in care.”

The factors driving the increased mortality are unclear, according to Dr. Denson; however, “when you go on to a new service [as a resident] ... you are now responsible for 20 new people all of a sudden that night.” Therefore, these transitions can be a hectic time characterized by reduced communication and inefficient discharges. In addition, the incoming residents lack familiarity with their new patients’ particulars.

“The handoffs are definitely not preventable, so this is something that has to be dealt with,” he maintained. The study’s findings hint at several possible areas for improvement.

None of the 10 residency programs surveyed provided formal education for monthly resident handoffs, focusing instead on handoffs at shift changes, and most programs lacked a standard procedure, with just one requiring that the handoff be done in person. The programs also varied greatly in their staggering of handoffs – separating transitions of interns (first-year residents) and higher-level residents by at least a few days – to minimize impact.

Despite the absence of outcomes data in this area, some hospitals are forging ahead with their own interventions intended to smooth care transitions, Dr. Denson reported. “In at least two hospitals that I’ve worked in, they are implementing what is called a warm handoff,” he explained. “Basically, a resident from the prior rotation comes the next day and rounds with the new team so he can tell them, ‘Oh, this guy looks a little worse today, you may want to watch him,’ or ‘He looks a little better.’ ”

In the study, conducted while Dr. Denson was chief resident at the NYU School of Medicine, he and his colleagues analyzed data from 10 university-affiliated Veterans Affairs hospitals and internal medicine residency programs that provided their residents’ schedules. Analyses were based on a total of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients between July 2008 and June 2014.

Hospitalized patients were categorized as having a transition in resident care if they were admitted before the date of an end-of-month house staff transition in care and were discharged in the week after it.

In unadjusted analyses, patients who had a transition of care – whether of intern only, resident only, or both – had significantly higher odds of inpatient mortality and of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality, compared with counterparts who did not have the corresponding transition of care.

In adjusted analyses, patients who had an intern transition still had higher odds of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.14). In addition, patients had persistently elevated odds of 30-day mortality and 90-day postdischarge mortality if they had an intern transition (odds ratios, 1.20 and 1.17, respectively), a resident transition (1.15 and 1.14), or both (1.10 and 1.09).

The findings “suggest possibly a level-of-training effect to these transitions, as it’s the most inexperienced people that have the higher rate of mortality,” noted Dr. Denson, who disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest. “Interns, being the first-years, tend to carry the bulk of the work in most hospitals, which is an interesting paradigm in our organization. And that may be a good explanation for why we are seeing this.”

AT ATS 2016

Key clinical point: The risk of death for hospitalized patients rises when their care is handed off from one resident to another.

Major finding: Patients who had a resident transition in care during their stay had 9%-20% higher adjusted odds of death.

Data source: A multicenter retrospective cohort study of 230,701 discharges of adult medical patients from Veterans Affairs medical centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Denson disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Esophagectomy 30-day readmission rate pegged at 19%

BALTIMORE – Approximately one in five patients is readmitted after esophagectomy, and leading risk factors for readmission are longer operative time, post-surgical ICU admission, and preoperative blood transfusions, according to a single-center study of 86 patients.

As one of the first reports on readmissions following esophagectomy with complete follow-up, this study, conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., demonstrates that even in a high volume center with specialization in esophageal and foregut surgery, readmission after esophagectomy is not uncommon, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

“In the context of increasing pressures to reduce length of stay, we must also put in the effort to better understand our readmission rates and the important factors that affect them,” said study investigator Dr. Stephen Cassivi. “Reporting on ‘improved’ lengths of stay without accompanying data on readmission rates is not telling the whole story.”

According to the Mayo Clinic research team, identifying risk factors that predict readmissions might permit improved patient management and outcomes.

“Careful collection of data regarding patient outcomes, including unplanned hospital readmissions is essential to improve the quality of patient care since national databases can leave gaps in data regarding follow-up of these patients by failing to identify all readmissions after their surgery,” said Dr. Karen J. Dickinson, who presented the study at the meeting.

The study was designed such that all patients undergoing an elective esophagectomy between August 2013 and July 2014 were contacted directly to follow up on whether they had been readmitted to any medical institution within 30 days of dismissal from the Mayo Clinic. Among all patients who underwent esophagectomy during the one-year study period, 86 patients met the study inclusion criteria. Follow-up was complete in 100% of patients, according to Dr. Dickinson.

Median age of the patients at the time of surgery was 63 years, and the majority of patients were men (70 patients). The most common operative approach was transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) esophagectomy (72%); 7% of cases were performed using a minimally invasive approach. Overall 30-day mortality was 2% (2/86), and anastomotic leak occurred in 8% of the patients.

Median length of stay was 9 days, and the rate of unplanned 30-day readmission was 19% (16 patients). Of these patients, 88% were readmitted to the Mayo Clinic and 12% were readmitted to other medical institutions.

The most common reasons for readmission were due to respiratory causes such as dyspnea, pleural effusions or pneumonia and gastrointestinal causes, including bowel obstruction and anastomotic complications.

Using multivariable analysis, the researchers found that the factors significantly associated with unplanned readmission were postoperative ICU admission (13% in non-readmitted, 38% in admitted), perioperative blood transfusion (12% vs. 38%), and operative length (368 vs. 460 minutes). Importantly, initial hospital length of stay was not associated with the need for readmission. Furthermore, ASA score, sex, BMI, neoadjuvant therapy, and postoperative pain scores also were not associated with unplanned readmission.

“Identifying these risk factors in the perioperative and postoperative setting may provide opportunities for decreasing morbidity, improving readmission rates, and enhancing overall patient outcomes,” Dr. Dickinson concluded.

A video of this presentation at the AATS Annual Meeting is available online.

Dr. Dickinson and her colleagues reported having no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @ThoracicTweets

BALTIMORE – Approximately one in five patients is readmitted after esophagectomy, and leading risk factors for readmission are longer operative time, post-surgical ICU admission, and preoperative blood transfusions, according to a single-center study of 86 patients.

As one of the first reports on readmissions following esophagectomy with complete follow-up, this study, conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., demonstrates that even in a high volume center with specialization in esophageal and foregut surgery, readmission after esophagectomy is not uncommon, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

“In the context of increasing pressures to reduce length of stay, we must also put in the effort to better understand our readmission rates and the important factors that affect them,” said study investigator Dr. Stephen Cassivi. “Reporting on ‘improved’ lengths of stay without accompanying data on readmission rates is not telling the whole story.”

According to the Mayo Clinic research team, identifying risk factors that predict readmissions might permit improved patient management and outcomes.

“Careful collection of data regarding patient outcomes, including unplanned hospital readmissions is essential to improve the quality of patient care since national databases can leave gaps in data regarding follow-up of these patients by failing to identify all readmissions after their surgery,” said Dr. Karen J. Dickinson, who presented the study at the meeting.

The study was designed such that all patients undergoing an elective esophagectomy between August 2013 and July 2014 were contacted directly to follow up on whether they had been readmitted to any medical institution within 30 days of dismissal from the Mayo Clinic. Among all patients who underwent esophagectomy during the one-year study period, 86 patients met the study inclusion criteria. Follow-up was complete in 100% of patients, according to Dr. Dickinson.

Median age of the patients at the time of surgery was 63 years, and the majority of patients were men (70 patients). The most common operative approach was transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) esophagectomy (72%); 7% of cases were performed using a minimally invasive approach. Overall 30-day mortality was 2% (2/86), and anastomotic leak occurred in 8% of the patients.

Median length of stay was 9 days, and the rate of unplanned 30-day readmission was 19% (16 patients). Of these patients, 88% were readmitted to the Mayo Clinic and 12% were readmitted to other medical institutions.

The most common reasons for readmission were due to respiratory causes such as dyspnea, pleural effusions or pneumonia and gastrointestinal causes, including bowel obstruction and anastomotic complications.

Using multivariable analysis, the researchers found that the factors significantly associated with unplanned readmission were postoperative ICU admission (13% in non-readmitted, 38% in admitted), perioperative blood transfusion (12% vs. 38%), and operative length (368 vs. 460 minutes). Importantly, initial hospital length of stay was not associated with the need for readmission. Furthermore, ASA score, sex, BMI, neoadjuvant therapy, and postoperative pain scores also were not associated with unplanned readmission.

“Identifying these risk factors in the perioperative and postoperative setting may provide opportunities for decreasing morbidity, improving readmission rates, and enhancing overall patient outcomes,” Dr. Dickinson concluded.

A video of this presentation at the AATS Annual Meeting is available online.

Dr. Dickinson and her colleagues reported having no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @ThoracicTweets

BALTIMORE – Approximately one in five patients is readmitted after esophagectomy, and leading risk factors for readmission are longer operative time, post-surgical ICU admission, and preoperative blood transfusions, according to a single-center study of 86 patients.

As one of the first reports on readmissions following esophagectomy with complete follow-up, this study, conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., demonstrates that even in a high volume center with specialization in esophageal and foregut surgery, readmission after esophagectomy is not uncommon, researchers reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

“In the context of increasing pressures to reduce length of stay, we must also put in the effort to better understand our readmission rates and the important factors that affect them,” said study investigator Dr. Stephen Cassivi. “Reporting on ‘improved’ lengths of stay without accompanying data on readmission rates is not telling the whole story.”

According to the Mayo Clinic research team, identifying risk factors that predict readmissions might permit improved patient management and outcomes.

“Careful collection of data regarding patient outcomes, including unplanned hospital readmissions is essential to improve the quality of patient care since national databases can leave gaps in data regarding follow-up of these patients by failing to identify all readmissions after their surgery,” said Dr. Karen J. Dickinson, who presented the study at the meeting.

The study was designed such that all patients undergoing an elective esophagectomy between August 2013 and July 2014 were contacted directly to follow up on whether they had been readmitted to any medical institution within 30 days of dismissal from the Mayo Clinic. Among all patients who underwent esophagectomy during the one-year study period, 86 patients met the study inclusion criteria. Follow-up was complete in 100% of patients, according to Dr. Dickinson.

Median age of the patients at the time of surgery was 63 years, and the majority of patients were men (70 patients). The most common operative approach was transthoracic (Ivor Lewis) esophagectomy (72%); 7% of cases were performed using a minimally invasive approach. Overall 30-day mortality was 2% (2/86), and anastomotic leak occurred in 8% of the patients.

Median length of stay was 9 days, and the rate of unplanned 30-day readmission was 19% (16 patients). Of these patients, 88% were readmitted to the Mayo Clinic and 12% were readmitted to other medical institutions.

The most common reasons for readmission were due to respiratory causes such as dyspnea, pleural effusions or pneumonia and gastrointestinal causes, including bowel obstruction and anastomotic complications.

Using multivariable analysis, the researchers found that the factors significantly associated with unplanned readmission were postoperative ICU admission (13% in non-readmitted, 38% in admitted), perioperative blood transfusion (12% vs. 38%), and operative length (368 vs. 460 minutes). Importantly, initial hospital length of stay was not associated with the need for readmission. Furthermore, ASA score, sex, BMI, neoadjuvant therapy, and postoperative pain scores also were not associated with unplanned readmission.

“Identifying these risk factors in the perioperative and postoperative setting may provide opportunities for decreasing morbidity, improving readmission rates, and enhancing overall patient outcomes,” Dr. Dickinson concluded.

A video of this presentation at the AATS Annual Meeting is available online.

Dr. Dickinson and her colleagues reported having no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @ThoracicTweets

AT THE AATS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Operative length, perioperative blood transfusions, and postoperative ICU admission were significant risk factors for readmission after esophagectomy.

Major finding: The rate of unplanned 30-day readmission was 19%.

Data source: The study assessed 86 patients who underwent esophagectomy at the Mayo Clinic between August 2012 and July 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Dickinson and her colleagues reported having no relevant disclosures.

Tissue flap reconstruction associated with higher costs, postop complication risk

LOS ANGELES – The use of locoregional tissue flaps in combination with abdominoperineal resection was associated with higher rates of perioperative complications, longer hospital stays, and higher total hospital charges, compared with patients who did not undergo tissue flap reconstruction, an analysis of national data showed.

The findings come at a time when closure of perineal wounds with tissue flaps is an increasingly common approach, especially in academic institutions, Dr. Nicole Lopez said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. “The role of selection bias in this [study] is difficult to determine, but I think it’s important that we clarify the utility of this technique before more widespread adoption of the approach,” she said.

According to Dr. Lopez of the department of surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, perineal wound complications can occur in 16%-49% of patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection. Contributing factors include noncollapsible dead space, bacterial contamination, wound characteristics, and patient comorbidities.

In an effort to identify national trends in the use of tissue flaps in patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection for rectal or anal cancer, as well as the effect of this approach on perioperative complications, length of stay, and total hospital charges, Dr. Lopez and her associates used the National Inpatient Sample to identify patients aged 18-80 years who were treated between 2000 and 2013. They excluded patients undergoing nonelective procedures or additional pelvic organ resections. Patients who received a tissue flap were compared with those who did not.

Dr. Lopez reported results from 298 patients who received a tissue flap graft and 12,107 who did not. Variables significantly associated with receiving a tissue flap, compared with not receiving one, were being male (73% vs. 66%, respectively; P =. 01), having anal cancer (32% vs. 11%; P less than .0001), being a smoker (34% vs. 23%; P less than .0001), undergoing the procedure in a large hospital (75% vs. 67%; P = .003), and undergoing the procedure in an urban teaching hospital (89% vs. 53%; P less than .0001).

The researchers also found that the number of concurrent tissue flaps performed rose significantly during the study period, from 0.4% in 2000 to 6% in 2013 (P less than .0001). “This was most noted in teaching institutions, compared with nonteaching institutions,” Dr. Lopez said.

Bivariate analysis revealed that, compared with patients who did not receive tissue flaps, those who did had higher rates of postoperative complications (43% vs. 33%, respectively; P less than .0001), a longer hospital stay (mean of 9 vs. 7 days; P less than .001), and higher total hospital charges (mean of $67,200 vs. $42,300; P less than .001). These trends persisted on multivariate analysis. Specifically, patients who received tissue flaps were 4.14 times more likely to have wound complications, had a length of stay that averaged an additional 2.78 days, and had $28,000 more in total hospital charges.

“The extended duration of the study enables evaluation of trends over time, and this is the first study that analyzes the costs associated with these procedures,” Dr. Lopez said. She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective, nonrandomized design and the potential for selection bias. In addition, the National Inpatient Sample “is susceptible to coding errors, a lack of patient-specific oncologic history, and the inability to assess postdischarge occurrences, since this only looks at inpatient stays.”

Dr. Lopez reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The use of locoregional tissue flaps in combination with abdominoperineal resection was associated with higher rates of perioperative complications, longer hospital stays, and higher total hospital charges, compared with patients who did not undergo tissue flap reconstruction, an analysis of national data showed.

The findings come at a time when closure of perineal wounds with tissue flaps is an increasingly common approach, especially in academic institutions, Dr. Nicole Lopez said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. “The role of selection bias in this [study] is difficult to determine, but I think it’s important that we clarify the utility of this technique before more widespread adoption of the approach,” she said.

According to Dr. Lopez of the department of surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, perineal wound complications can occur in 16%-49% of patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection. Contributing factors include noncollapsible dead space, bacterial contamination, wound characteristics, and patient comorbidities.

In an effort to identify national trends in the use of tissue flaps in patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection for rectal or anal cancer, as well as the effect of this approach on perioperative complications, length of stay, and total hospital charges, Dr. Lopez and her associates used the National Inpatient Sample to identify patients aged 18-80 years who were treated between 2000 and 2013. They excluded patients undergoing nonelective procedures or additional pelvic organ resections. Patients who received a tissue flap were compared with those who did not.

Dr. Lopez reported results from 298 patients who received a tissue flap graft and 12,107 who did not. Variables significantly associated with receiving a tissue flap, compared with not receiving one, were being male (73% vs. 66%, respectively; P =. 01), having anal cancer (32% vs. 11%; P less than .0001), being a smoker (34% vs. 23%; P less than .0001), undergoing the procedure in a large hospital (75% vs. 67%; P = .003), and undergoing the procedure in an urban teaching hospital (89% vs. 53%; P less than .0001).

The researchers also found that the number of concurrent tissue flaps performed rose significantly during the study period, from 0.4% in 2000 to 6% in 2013 (P less than .0001). “This was most noted in teaching institutions, compared with nonteaching institutions,” Dr. Lopez said.

Bivariate analysis revealed that, compared with patients who did not receive tissue flaps, those who did had higher rates of postoperative complications (43% vs. 33%, respectively; P less than .0001), a longer hospital stay (mean of 9 vs. 7 days; P less than .001), and higher total hospital charges (mean of $67,200 vs. $42,300; P less than .001). These trends persisted on multivariate analysis. Specifically, patients who received tissue flaps were 4.14 times more likely to have wound complications, had a length of stay that averaged an additional 2.78 days, and had $28,000 more in total hospital charges.

“The extended duration of the study enables evaluation of trends over time, and this is the first study that analyzes the costs associated with these procedures,” Dr. Lopez said. She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective, nonrandomized design and the potential for selection bias. In addition, the National Inpatient Sample “is susceptible to coding errors, a lack of patient-specific oncologic history, and the inability to assess postdischarge occurrences, since this only looks at inpatient stays.”

Dr. Lopez reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The use of locoregional tissue flaps in combination with abdominoperineal resection was associated with higher rates of perioperative complications, longer hospital stays, and higher total hospital charges, compared with patients who did not undergo tissue flap reconstruction, an analysis of national data showed.

The findings come at a time when closure of perineal wounds with tissue flaps is an increasingly common approach, especially in academic institutions, Dr. Nicole Lopez said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. “The role of selection bias in this [study] is difficult to determine, but I think it’s important that we clarify the utility of this technique before more widespread adoption of the approach,” she said.

According to Dr. Lopez of the department of surgery at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, perineal wound complications can occur in 16%-49% of patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection. Contributing factors include noncollapsible dead space, bacterial contamination, wound characteristics, and patient comorbidities.

In an effort to identify national trends in the use of tissue flaps in patients undergoing abdominoperineal resection for rectal or anal cancer, as well as the effect of this approach on perioperative complications, length of stay, and total hospital charges, Dr. Lopez and her associates used the National Inpatient Sample to identify patients aged 18-80 years who were treated between 2000 and 2013. They excluded patients undergoing nonelective procedures or additional pelvic organ resections. Patients who received a tissue flap were compared with those who did not.

Dr. Lopez reported results from 298 patients who received a tissue flap graft and 12,107 who did not. Variables significantly associated with receiving a tissue flap, compared with not receiving one, were being male (73% vs. 66%, respectively; P =. 01), having anal cancer (32% vs. 11%; P less than .0001), being a smoker (34% vs. 23%; P less than .0001), undergoing the procedure in a large hospital (75% vs. 67%; P = .003), and undergoing the procedure in an urban teaching hospital (89% vs. 53%; P less than .0001).

The researchers also found that the number of concurrent tissue flaps performed rose significantly during the study period, from 0.4% in 2000 to 6% in 2013 (P less than .0001). “This was most noted in teaching institutions, compared with nonteaching institutions,” Dr. Lopez said.

Bivariate analysis revealed that, compared with patients who did not receive tissue flaps, those who did had higher rates of postoperative complications (43% vs. 33%, respectively; P less than .0001), a longer hospital stay (mean of 9 vs. 7 days; P less than .001), and higher total hospital charges (mean of $67,200 vs. $42,300; P less than .001). These trends persisted on multivariate analysis. Specifically, patients who received tissue flaps were 4.14 times more likely to have wound complications, had a length of stay that averaged an additional 2.78 days, and had $28,000 more in total hospital charges.

“The extended duration of the study enables evaluation of trends over time, and this is the first study that analyzes the costs associated with these procedures,” Dr. Lopez said. She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its retrospective, nonrandomized design and the potential for selection bias. In addition, the National Inpatient Sample “is susceptible to coding errors, a lack of patient-specific oncologic history, and the inability to assess postdischarge occurrences, since this only looks at inpatient stays.”

Dr. Lopez reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Complications occurred more often in patients who underwent concurrent tissue flap reconstruction during abdominoperineal resection, compared with those who did not.

Major finding: Compared with patients who did not receive tissue flaps, those who did were 4.14 times more likely to have wound complications, had a length of stay that averaged an additional 2.78 days, and had $28,000 more in total hospital charges.

Data source: A study of 12,405 patients aged 18-80 years from the National Inpatient Sample who underwent abdominoperineal resection for rectal or anal cancer between 2000 and 2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Lopez reported having no financial disclosures.

How to defeat radial artery spasm in transradial PCI

PARIS – The threat of radial artery spasm is the chief impediment to broader use of transradial access cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention, but Dr. Julien Adjedj has a series of tips and tricks to defeat it.

At Cochin University Hospital in Paris, where he is chief of the interventional cardiology clinic, 95% of all PCIs are done transradially.

“With the tips and tricks we use, we have a transradial approach failure rate of only 1.5% at our center,” Dr. Adjedj said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He and his colleagues have conducted a series of prospective, randomized studies of various prophylactic vasodilator regimens in 1,950 patients undergoing transradial PCI.

The winning strategy? Place 2.5-5.0 mg of the calcium channel blocker verapamil in the arterial sheath as first-line preventive therapy.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders – for example, the investigators found that the incidence of radial artery spasm (RAS) is higher in women and younger patients – the use of prophylactic verapamil placed in the arterial sheath reduced the likelihood of RAS by 75% and 72%, respectively, compared with placebo.

Intra-arterial diltiazem at 5 mg, isosorbide dinitrate at 1 mg, and molsidomine at 1 mg were also more effective than placebo. However, diltiazem and isosorbide dinitrate were associated with an unacceptable increased risk of severe hypotension compared to placebo, and molsidomine is not widely available outside France.

In contrast, verapamil was not linked to severe hypotension.

Overall, RAS occurred in 22.2 % of patients on placebo, 7.1% of those on verapamil at 2.5 mg, 7.9% with verapamil at 5 mg, 6.5% with isosorbide dinitrate at 1 mg, 9.1% of those on diltiazem at 5 mg, 13.3% with molsidomine at 1 mg, and 4.8% with verapamil 2.5 mg plus molsidomine 1 mg.

When it proves difficult to advance the catheter during a transradial PCI despite prophylactic verapamil, the first thing to do is check whether the problem really is RAS or is instead a matter of having entered a remnant artery. This is accomplished by supplementing the verapamil with 1 mg of intra-arterial isosorbide dinitrate; if the catheter still won’t pass, seriously consider the possibility of a remnant artery.

Among Dr. Adjedj’s tips on how to successfully pass the catheter through a drug-refractory RAS: Use a hydrophilic 0.035-inch guide wire, switch from a 6 Fr to a smaller 5 or 4 Fr catheter, or use a long multipurpose 5 Fr catheter inside the 6 Fr guiding catheter.

“It’s like nested Russian dolls. It can pass through the spasm without any pain,” said Dr. Adjedj.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

PARIS – The threat of radial artery spasm is the chief impediment to broader use of transradial access cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention, but Dr. Julien Adjedj has a series of tips and tricks to defeat it.

At Cochin University Hospital in Paris, where he is chief of the interventional cardiology clinic, 95% of all PCIs are done transradially.

“With the tips and tricks we use, we have a transradial approach failure rate of only 1.5% at our center,” Dr. Adjedj said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He and his colleagues have conducted a series of prospective, randomized studies of various prophylactic vasodilator regimens in 1,950 patients undergoing transradial PCI.

The winning strategy? Place 2.5-5.0 mg of the calcium channel blocker verapamil in the arterial sheath as first-line preventive therapy.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders – for example, the investigators found that the incidence of radial artery spasm (RAS) is higher in women and younger patients – the use of prophylactic verapamil placed in the arterial sheath reduced the likelihood of RAS by 75% and 72%, respectively, compared with placebo.

Intra-arterial diltiazem at 5 mg, isosorbide dinitrate at 1 mg, and molsidomine at 1 mg were also more effective than placebo. However, diltiazem and isosorbide dinitrate were associated with an unacceptable increased risk of severe hypotension compared to placebo, and molsidomine is not widely available outside France.

In contrast, verapamil was not linked to severe hypotension.

Overall, RAS occurred in 22.2 % of patients on placebo, 7.1% of those on verapamil at 2.5 mg, 7.9% with verapamil at 5 mg, 6.5% with isosorbide dinitrate at 1 mg, 9.1% of those on diltiazem at 5 mg, 13.3% with molsidomine at 1 mg, and 4.8% with verapamil 2.5 mg plus molsidomine 1 mg.

When it proves difficult to advance the catheter during a transradial PCI despite prophylactic verapamil, the first thing to do is check whether the problem really is RAS or is instead a matter of having entered a remnant artery. This is accomplished by supplementing the verapamil with 1 mg of intra-arterial isosorbide dinitrate; if the catheter still won’t pass, seriously consider the possibility of a remnant artery.

Among Dr. Adjedj’s tips on how to successfully pass the catheter through a drug-refractory RAS: Use a hydrophilic 0.035-inch guide wire, switch from a 6 Fr to a smaller 5 or 4 Fr catheter, or use a long multipurpose 5 Fr catheter inside the 6 Fr guiding catheter.

“It’s like nested Russian dolls. It can pass through the spasm without any pain,” said Dr. Adjedj.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

PARIS – The threat of radial artery spasm is the chief impediment to broader use of transradial access cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention, but Dr. Julien Adjedj has a series of tips and tricks to defeat it.

At Cochin University Hospital in Paris, where he is chief of the interventional cardiology clinic, 95% of all PCIs are done transradially.

“With the tips and tricks we use, we have a transradial approach failure rate of only 1.5% at our center,” Dr. Adjedj said at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

He and his colleagues have conducted a series of prospective, randomized studies of various prophylactic vasodilator regimens in 1,950 patients undergoing transradial PCI.

The winning strategy? Place 2.5-5.0 mg of the calcium channel blocker verapamil in the arterial sheath as first-line preventive therapy.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders – for example, the investigators found that the incidence of radial artery spasm (RAS) is higher in women and younger patients – the use of prophylactic verapamil placed in the arterial sheath reduced the likelihood of RAS by 75% and 72%, respectively, compared with placebo.

Intra-arterial diltiazem at 5 mg, isosorbide dinitrate at 1 mg, and molsidomine at 1 mg were also more effective than placebo. However, diltiazem and isosorbide dinitrate were associated with an unacceptable increased risk of severe hypotension compared to placebo, and molsidomine is not widely available outside France.

In contrast, verapamil was not linked to severe hypotension.

Overall, RAS occurred in 22.2 % of patients on placebo, 7.1% of those on verapamil at 2.5 mg, 7.9% with verapamil at 5 mg, 6.5% with isosorbide dinitrate at 1 mg, 9.1% of those on diltiazem at 5 mg, 13.3% with molsidomine at 1 mg, and 4.8% with verapamil 2.5 mg plus molsidomine 1 mg.

When it proves difficult to advance the catheter during a transradial PCI despite prophylactic verapamil, the first thing to do is check whether the problem really is RAS or is instead a matter of having entered a remnant artery. This is accomplished by supplementing the verapamil with 1 mg of intra-arterial isosorbide dinitrate; if the catheter still won’t pass, seriously consider the possibility of a remnant artery.

Among Dr. Adjedj’s tips on how to successfully pass the catheter through a drug-refractory RAS: Use a hydrophilic 0.035-inch guide wire, switch from a 6 Fr to a smaller 5 or 4 Fr catheter, or use a long multipurpose 5 Fr catheter inside the 6 Fr guiding catheter.

“It’s like nested Russian dolls. It can pass through the spasm without any pain,” said Dr. Adjedj.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: Placing 2.5-5.0 mg of verapamil in the arterial sheath when performing transradial access PCI reduces the risk of radial artery spasm by three-quarters compared with placebo.

Major finding: The incidence of radial artery spasm during transradial access PCI was 7.1% when 2.5 mg of verapamil was introduced through the arterial sheath, compared with 22.2% with placebo.

Data source: This series of prospective randomized studies comprised 1,950 patients undergoing transradial access PCI by way of various intra-arterial vasodilators or placebo.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, conducted free of commercial support.

ICD same-day discharge safe, but not a money saver

San Francisco – Same day discharge is generally safe after cardioverter defibrillator implantation for primary prevention, but it doesn’t save money.

Furthermore, guidelines are needed to standardize the practice as it becomes increasingly common in the United States, according to a 25-site investigation.

After implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) procedures, patients were monitored for 3-4 hours, and their devices were checked for proper functioning; 129 patients who were stable at that point were randomized to early discharge and 136 to next day discharge (NDD).

The overall 30-day procedural complication rate was 3.1% in the same day discharge (SDD) group and 1.6% in the NDD group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .37). Three patients in the SDD group developed hematomas that resolved on their own, and one had a cardiac perforation. One NDD patient dislodged a lead and another developed an infection. There were no differences in quality of life measures between the two groups at 30 days.

However, there were also no differences in procedural and perioperative direct costs, which was surprising because saving money is a major driver of SDD, and the most expensive part of ICD implantation is the first 24 hours. Direct per-patient medical costs in the study – estimated by applying hospital cost-to-charge ratios to the Medicare-reported charge – were $31,771 for SDD and $30,437 for NDD, but NDD was more expensive than SDD at several sites. The investigators suspect a flaw in their analysis related to the opaque nature of hospital accounting, and plan to look into the matter further with modeling to identify savings opportunities with SDD.

“We can insert ICDs on an outpatient basis, but this study will be difficult to replicate because clinical practice is moving towards SDD. In view of this, we think professional societies should be thinking of standardizing criteria for SDD; guidelines would help with the adoption of this approach. There are clinicians who are astute and have great clinical judgment, but there are others who need a scoring system. We believe that by using the 270,000 patients in the [American College of Cardiology’s ICD Registry], there is the ability to identify patients who have low periprocedural risk,” said lead investigator Dr. Ranjit Suri, a cardiologist at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York.

The study excluded patients receiving an ICD for secondary prevention, as well as those on periprocedural heparin and patients who were pacemaker dependent. SDD seemed safe otherwise, but it’s unknown “if our concept of low risk is acceptable to all implanting physicians,” Dr. Suri said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

The study groups were well matched. About 75% in each arm were men, and ischemic cardiomyopathy was the leading ICD indication. Patients were amenable to the idea of SDD; the advent of remote monitoring “adds a certain sense of safety” for both patients and physicians, he said.

Dr. Suri is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim and St. Jude Medical. He is also a consultant for Biosense Webster and Zoll, and receives research funding from St. Jude.

|

Dr. Thomas Deering |

The vast majority of primary prevention patients who are clinically stable enough to come in as outpatients can go home as outpatients if you watch them for a short period of time and make sure they are clinically stable. Most patients don’t want to be in the hospital, and many hospitals are crunched for available beds. It would be great to have guidelines on how to handle this, but we have to allow for clinical judgment.

Dr. Thomas Deering is chief of the Arrhythmia Center at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta, where he is also chairman of the Executive Council and the Clinical Centers for Excellence. He moderated Dr. Suri’s presentation and was not involved in the work.

|

Dr. Thomas Deering |

The vast majority of primary prevention patients who are clinically stable enough to come in as outpatients can go home as outpatients if you watch them for a short period of time and make sure they are clinically stable. Most patients don’t want to be in the hospital, and many hospitals are crunched for available beds. It would be great to have guidelines on how to handle this, but we have to allow for clinical judgment.

Dr. Thomas Deering is chief of the Arrhythmia Center at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta, where he is also chairman of the Executive Council and the Clinical Centers for Excellence. He moderated Dr. Suri’s presentation and was not involved in the work.

|

Dr. Thomas Deering |

The vast majority of primary prevention patients who are clinically stable enough to come in as outpatients can go home as outpatients if you watch them for a short period of time and make sure they are clinically stable. Most patients don’t want to be in the hospital, and many hospitals are crunched for available beds. It would be great to have guidelines on how to handle this, but we have to allow for clinical judgment.

Dr. Thomas Deering is chief of the Arrhythmia Center at the Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta, where he is also chairman of the Executive Council and the Clinical Centers for Excellence. He moderated Dr. Suri’s presentation and was not involved in the work.

San Francisco – Same day discharge is generally safe after cardioverter defibrillator implantation for primary prevention, but it doesn’t save money.

Furthermore, guidelines are needed to standardize the practice as it becomes increasingly common in the United States, according to a 25-site investigation.

After implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) procedures, patients were monitored for 3-4 hours, and their devices were checked for proper functioning; 129 patients who were stable at that point were randomized to early discharge and 136 to next day discharge (NDD).

The overall 30-day procedural complication rate was 3.1% in the same day discharge (SDD) group and 1.6% in the NDD group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .37). Three patients in the SDD group developed hematomas that resolved on their own, and one had a cardiac perforation. One NDD patient dislodged a lead and another developed an infection. There were no differences in quality of life measures between the two groups at 30 days.

However, there were also no differences in procedural and perioperative direct costs, which was surprising because saving money is a major driver of SDD, and the most expensive part of ICD implantation is the first 24 hours. Direct per-patient medical costs in the study – estimated by applying hospital cost-to-charge ratios to the Medicare-reported charge – were $31,771 for SDD and $30,437 for NDD, but NDD was more expensive than SDD at several sites. The investigators suspect a flaw in their analysis related to the opaque nature of hospital accounting, and plan to look into the matter further with modeling to identify savings opportunities with SDD.

“We can insert ICDs on an outpatient basis, but this study will be difficult to replicate because clinical practice is moving towards SDD. In view of this, we think professional societies should be thinking of standardizing criteria for SDD; guidelines would help with the adoption of this approach. There are clinicians who are astute and have great clinical judgment, but there are others who need a scoring system. We believe that by using the 270,000 patients in the [American College of Cardiology’s ICD Registry], there is the ability to identify patients who have low periprocedural risk,” said lead investigator Dr. Ranjit Suri, a cardiologist at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York.

The study excluded patients receiving an ICD for secondary prevention, as well as those on periprocedural heparin and patients who were pacemaker dependent. SDD seemed safe otherwise, but it’s unknown “if our concept of low risk is acceptable to all implanting physicians,” Dr. Suri said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

The study groups were well matched. About 75% in each arm were men, and ischemic cardiomyopathy was the leading ICD indication. Patients were amenable to the idea of SDD; the advent of remote monitoring “adds a certain sense of safety” for both patients and physicians, he said.

Dr. Suri is a speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim and St. Jude Medical. He is also a consultant for Biosense Webster and Zoll, and receives research funding from St. Jude.

San Francisco – Same day discharge is generally safe after cardioverter defibrillator implantation for primary prevention, but it doesn’t save money.

Furthermore, guidelines are needed to standardize the practice as it becomes increasingly common in the United States, according to a 25-site investigation.

After implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) procedures, patients were monitored for 3-4 hours, and their devices were checked for proper functioning; 129 patients who were stable at that point were randomized to early discharge and 136 to next day discharge (NDD).

The overall 30-day procedural complication rate was 3.1% in the same day discharge (SDD) group and 1.6% in the NDD group, a nonsignificant difference (P = .37). Three patients in the SDD group developed hematomas that resolved on their own, and one had a cardiac perforation. One NDD patient dislodged a lead and another developed an infection. There were no differences in quality of life measures between the two groups at 30 days.