User login

Are We Giving Nails Away? [editorial]

ASLMS: Tips for Effective Laser Hair Removal in Darker Skin

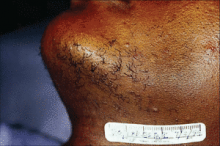

PHOENIX - When performing laser hair removal in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI, keep in mind that darker skin contains more melanin in the epidermis, which acts as a competing chromophore, "so the risk for epidermal injury is higher," Dr. Andrew F. Alexis said.

Other tips to remember when treating this patient population include the melanocytes' tendency "to be labile in response to injury and inflammation, so there is an increased risk of dyschromia," Dr. Alexis said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. "This can manifest as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation following laser hair removal procedures."

He went on to note that fibroblasts in the dermis "are also more reactive to injury, so there is an increased risk of hypertrophic scars and keloids when performing surgical or some cosmetic procedures. In addition, having curved follicles [which are primarily seen in people of African descent] is associated with an increased prevalence of a number of follicular disorders."

His guidelines for performing laser hair removal safely on skin of color include longer wavelengths, lower fluences, longer pulse durations, and increased epidermal cooling.

"You want longer wavelengths because we're trying to maximize the ratio of follicular bulb temperature to epidermal temperature," explained Dr. Alexis, director of the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke's & Roosevelt Hospitals, New York, and assistant professor of dermatology at Columbia University.

"Using wavelengths in the near infrared range, we are at a lower point on the melanin absorption curve and therefore are compromising some efficacy, but this is the range that is considered safest for darker skin types," he noted.

A review found that the long-pulsed 1064-nm laser had the lowest incidence of adverse events in dark-skinned patients, followed by the long-pulsed 800-nm or 810-nm diode laser (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:40-6).

"For patients with type IV or V skin, the diode laser is appropriate, as long as you are using long pulse durations," he said, "but for the darker skin types, particularly type VI, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is the best choice for safety reasons."

In one study, researchers used a 1064-nm laser with contact cooling to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae in 37 patients with skin types IV, V, and VI. They found that the highest fluences tolerated by the epidermis were 50 J/cm2 for skin type VI and 100 J/cm2 for skin types IV and V (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;47:263-70).

In another study, researchers used a 1064-nm laser with contact cooling for hair removal in 36 patients with skin types I-VI (Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30:13-7). Patients underwent three consecutive treatments at 4- to 6-week intervals. For skin types V-VI, investigators used a 30-millisecond pulse duration and a fluence of 30-45 J/cm2 on the face and 35-50 J/cm2 on nonfacial sites. Six months post treatment, the mean facial hair reduction ranged from 41% to 46%, while the mean hair reduction on the body ranged from 48% to 53%.

Based on the results of these and other studies, and from his own clinical experience, Dr. Alexis recommends a pulse duration of 100 milliseconds or 400 milliseconds when using a 810-nm diode laser and a duration of 20-30 milliseconds when using a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with contact cooling.

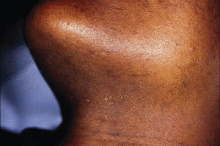

One recent study used a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with lower than traditional fluences for treating 22 patients with skin types IV-VI who had pseudofolliculitis barbae (Dermatol. Surg. 2009;35:98-107). Patients underwent five weekly treatments on the neck with a fluence of 12 J/cm2 and a pulse duration of 20 milliseconds and a spot size of 10 mm. At 4 weeks follow-up, the papule count had been reduced by a mean of 91% and dyspigmentation by a mean of 60%.

In another recent development, researchers studying a novel diode laser with a fluence of 5-10 J/cm2 used at a repetition rate of 10 Hz found that it resulted in less pain, faster treatment, and fewer adverse events compared with one pass of a high-fluence diode laser at 25-40 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types I-V (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:s14-7).

Options for epidermal cooling include cold gel, contact cryogen or forced air, and post treatment with ice packs for 10-15 minutes. Devices for contact cooling feature either a sapphire tip or chilled copper plate. Regardless of which type of contact cooling chosen, Dr. Alexis suggested "using a slower treatment speed in order to ensure adequate cooling before delivering pulse."

Dr. Alexis said that he had no relevant financial conflicts.

PHOENIX - When performing laser hair removal in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI, keep in mind that darker skin contains more melanin in the epidermis, which acts as a competing chromophore, "so the risk for epidermal injury is higher," Dr. Andrew F. Alexis said.

Other tips to remember when treating this patient population include the melanocytes' tendency "to be labile in response to injury and inflammation, so there is an increased risk of dyschromia," Dr. Alexis said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. "This can manifest as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation following laser hair removal procedures."

He went on to note that fibroblasts in the dermis "are also more reactive to injury, so there is an increased risk of hypertrophic scars and keloids when performing surgical or some cosmetic procedures. In addition, having curved follicles [which are primarily seen in people of African descent] is associated with an increased prevalence of a number of follicular disorders."

His guidelines for performing laser hair removal safely on skin of color include longer wavelengths, lower fluences, longer pulse durations, and increased epidermal cooling.

"You want longer wavelengths because we're trying to maximize the ratio of follicular bulb temperature to epidermal temperature," explained Dr. Alexis, director of the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke's & Roosevelt Hospitals, New York, and assistant professor of dermatology at Columbia University.

"Using wavelengths in the near infrared range, we are at a lower point on the melanin absorption curve and therefore are compromising some efficacy, but this is the range that is considered safest for darker skin types," he noted.

A review found that the long-pulsed 1064-nm laser had the lowest incidence of adverse events in dark-skinned patients, followed by the long-pulsed 800-nm or 810-nm diode laser (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:40-6).

"For patients with type IV or V skin, the diode laser is appropriate, as long as you are using long pulse durations," he said, "but for the darker skin types, particularly type VI, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is the best choice for safety reasons."

In one study, researchers used a 1064-nm laser with contact cooling to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae in 37 patients with skin types IV, V, and VI. They found that the highest fluences tolerated by the epidermis were 50 J/cm2 for skin type VI and 100 J/cm2 for skin types IV and V (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;47:263-70).

In another study, researchers used a 1064-nm laser with contact cooling for hair removal in 36 patients with skin types I-VI (Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30:13-7). Patients underwent three consecutive treatments at 4- to 6-week intervals. For skin types V-VI, investigators used a 30-millisecond pulse duration and a fluence of 30-45 J/cm2 on the face and 35-50 J/cm2 on nonfacial sites. Six months post treatment, the mean facial hair reduction ranged from 41% to 46%, while the mean hair reduction on the body ranged from 48% to 53%.

Based on the results of these and other studies, and from his own clinical experience, Dr. Alexis recommends a pulse duration of 100 milliseconds or 400 milliseconds when using a 810-nm diode laser and a duration of 20-30 milliseconds when using a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with contact cooling.

One recent study used a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with lower than traditional fluences for treating 22 patients with skin types IV-VI who had pseudofolliculitis barbae (Dermatol. Surg. 2009;35:98-107). Patients underwent five weekly treatments on the neck with a fluence of 12 J/cm2 and a pulse duration of 20 milliseconds and a spot size of 10 mm. At 4 weeks follow-up, the papule count had been reduced by a mean of 91% and dyspigmentation by a mean of 60%.

In another recent development, researchers studying a novel diode laser with a fluence of 5-10 J/cm2 used at a repetition rate of 10 Hz found that it resulted in less pain, faster treatment, and fewer adverse events compared with one pass of a high-fluence diode laser at 25-40 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types I-V (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:s14-7).

Options for epidermal cooling include cold gel, contact cryogen or forced air, and post treatment with ice packs for 10-15 minutes. Devices for contact cooling feature either a sapphire tip or chilled copper plate. Regardless of which type of contact cooling chosen, Dr. Alexis suggested "using a slower treatment speed in order to ensure adequate cooling before delivering pulse."

Dr. Alexis said that he had no relevant financial conflicts.

PHOENIX - When performing laser hair removal in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI, keep in mind that darker skin contains more melanin in the epidermis, which acts as a competing chromophore, "so the risk for epidermal injury is higher," Dr. Andrew F. Alexis said.

Other tips to remember when treating this patient population include the melanocytes' tendency "to be labile in response to injury and inflammation, so there is an increased risk of dyschromia," Dr. Alexis said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. "This can manifest as hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation following laser hair removal procedures."

He went on to note that fibroblasts in the dermis "are also more reactive to injury, so there is an increased risk of hypertrophic scars and keloids when performing surgical or some cosmetic procedures. In addition, having curved follicles [which are primarily seen in people of African descent] is associated with an increased prevalence of a number of follicular disorders."

His guidelines for performing laser hair removal safely on skin of color include longer wavelengths, lower fluences, longer pulse durations, and increased epidermal cooling.

"You want longer wavelengths because we're trying to maximize the ratio of follicular bulb temperature to epidermal temperature," explained Dr. Alexis, director of the Skin of Color Center at St. Luke's & Roosevelt Hospitals, New York, and assistant professor of dermatology at Columbia University.

"Using wavelengths in the near infrared range, we are at a lower point on the melanin absorption curve and therefore are compromising some efficacy, but this is the range that is considered safest for darker skin types," he noted.

A review found that the long-pulsed 1064-nm laser had the lowest incidence of adverse events in dark-skinned patients, followed by the long-pulsed 800-nm or 810-nm diode laser (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:40-6).

"For patients with type IV or V skin, the diode laser is appropriate, as long as you are using long pulse durations," he said, "but for the darker skin types, particularly type VI, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser is the best choice for safety reasons."

In one study, researchers used a 1064-nm laser with contact cooling to treat pseudofolliculitis barbae in 37 patients with skin types IV, V, and VI. They found that the highest fluences tolerated by the epidermis were 50 J/cm2 for skin type VI and 100 J/cm2 for skin types IV and V (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002;47:263-70).

In another study, researchers used a 1064-nm laser with contact cooling for hair removal in 36 patients with skin types I-VI (Dermatol. Surg. 2004;30:13-7). Patients underwent three consecutive treatments at 4- to 6-week intervals. For skin types V-VI, investigators used a 30-millisecond pulse duration and a fluence of 30-45 J/cm2 on the face and 35-50 J/cm2 on nonfacial sites. Six months post treatment, the mean facial hair reduction ranged from 41% to 46%, while the mean hair reduction on the body ranged from 48% to 53%.

Based on the results of these and other studies, and from his own clinical experience, Dr. Alexis recommends a pulse duration of 100 milliseconds or 400 milliseconds when using a 810-nm diode laser and a duration of 20-30 milliseconds when using a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with contact cooling.

One recent study used a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with lower than traditional fluences for treating 22 patients with skin types IV-VI who had pseudofolliculitis barbae (Dermatol. Surg. 2009;35:98-107). Patients underwent five weekly treatments on the neck with a fluence of 12 J/cm2 and a pulse duration of 20 milliseconds and a spot size of 10 mm. At 4 weeks follow-up, the papule count had been reduced by a mean of 91% and dyspigmentation by a mean of 60%.

In another recent development, researchers studying a novel diode laser with a fluence of 5-10 J/cm2 used at a repetition rate of 10 Hz found that it resulted in less pain, faster treatment, and fewer adverse events compared with one pass of a high-fluence diode laser at 25-40 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types I-V (J. Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:s14-7).

Options for epidermal cooling include cold gel, contact cryogen or forced air, and post treatment with ice packs for 10-15 minutes. Devices for contact cooling feature either a sapphire tip or chilled copper plate. Regardless of which type of contact cooling chosen, Dr. Alexis suggested "using a slower treatment speed in order to ensure adequate cooling before delivering pulse."

Dr. Alexis said that he had no relevant financial conflicts.

Transverse Melanonychia After Radiation Therapy [letter]

What Is Your Diagnosis? Segmental Vitiligo and En Coup de Sabre

ASLMS: Expert Reframes Skin of Color to "Skin of Cultures"

PHOENIX - Using laser technology to treat patients requires not only paying attention to the color of their skin, but also to the patient's ethnicity, according to Dr. Eliot F. Battle Jr.

"In my practice we don't just talk about skin of color anymore," Dr. Battle said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. "We talk about skin of cultures. It's not just their skin color but their ethnicity also makes a difference."

He explained that African Americans "have different combinations of black, white, Latin, Spanish, and Indian. Is my ethnicity a mixture of Nigerian, Italian, and Cherokee Indian, or am I a mixture of Cameroonian, Spanish, and Creek Indian? The future of this field, to improve the way we treat people, is going to appreciate more ethnicity as it relates to skin of color."

Brown skin "competes for the light of the laser, because melanin is absorbed across most of the photobiological spectrum, and we are a diverse population of people," said Dr. Battle, who said that he is a mix of Saharan African, Indo-European, and Asian. "To safely treat skin of color we have to use lower wavelengths, lower fluences, lower pulse durations, and aggressive epidermal cooling."

When he treats skin of color, Dr. Battle, a cosmetic dermatologist and laser

surgeon who is director of Cultura Cosmetic Medical Spa in Washington, normally favors an integrated approach and often combines laser treatments, medical skin care, and facial injectables.

For safe laser-hair removal in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, Dr. Battle recommends using a long-pulsed diode laser and the long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser.

Safe lasers for complexion blending and skin rejuvenation to improve texture include the microsecond Nd:YAG laser, fractional therapy, the excimer laser, the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, and the potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) laser, while safe lasers for skin tightening include infrared lasers and radiofrequency technology.

"There are many lasers we can use for skin of color," he said. "The key is to find a laser that you're comfortable with. Become an expert with that laser and go forward. I don't treat skin of color with vascular lasers, resurfacing lasers, or with intense pulsed light. I don't trust most parameters supplied by the manufacturers. I find my own, safe parameters. I treat more conservatively, and I do not cause erythema or edema."

Aggressive skin cooling is key, he said, and can include ice packs, cold gel, cold liquid, cold air flow, a copper plate, and sapphire windows. "We all get side effects when our skin temperature goes past 45° C," said Dr. Battle, who is also on the dermatology faculty at Howard University, Washington. "By using longer pulse durations, and thus pouring the energy in slower, I'm able to remove heat from the skin more effectively and more efficiently. Longer pulse durations are by far the safest way to treat skin of color."

More than two-thirds of Dr. Battle's patients have darker skin. Between 2002 and 2009, the two most popular nonsurgical procedures in his practice were laser hair removal and laser complexion blending, followed by Botox injections, laser skin rejuvenation, fillers, and laser skin tightening.

Lasers "have come a long way in the last decade," he said.

If side effects occur "show compassion and empathy," Dr. Battle noted. "Allow time to help, and always be available to your patients, even if it means giving them your cell phone number."

Dr. Battle disclosed that he has received equipment, discounts, and honoraria from a number of medical device companies.

PHOENIX - Using laser technology to treat patients requires not only paying attention to the color of their skin, but also to the patient's ethnicity, according to Dr. Eliot F. Battle Jr.

"In my practice we don't just talk about skin of color anymore," Dr. Battle said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. "We talk about skin of cultures. It's not just their skin color but their ethnicity also makes a difference."

He explained that African Americans "have different combinations of black, white, Latin, Spanish, and Indian. Is my ethnicity a mixture of Nigerian, Italian, and Cherokee Indian, or am I a mixture of Cameroonian, Spanish, and Creek Indian? The future of this field, to improve the way we treat people, is going to appreciate more ethnicity as it relates to skin of color."

Brown skin "competes for the light of the laser, because melanin is absorbed across most of the photobiological spectrum, and we are a diverse population of people," said Dr. Battle, who said that he is a mix of Saharan African, Indo-European, and Asian. "To safely treat skin of color we have to use lower wavelengths, lower fluences, lower pulse durations, and aggressive epidermal cooling."

When he treats skin of color, Dr. Battle, a cosmetic dermatologist and laser

surgeon who is director of Cultura Cosmetic Medical Spa in Washington, normally favors an integrated approach and often combines laser treatments, medical skin care, and facial injectables.

For safe laser-hair removal in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, Dr. Battle recommends using a long-pulsed diode laser and the long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser.

Safe lasers for complexion blending and skin rejuvenation to improve texture include the microsecond Nd:YAG laser, fractional therapy, the excimer laser, the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, and the potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) laser, while safe lasers for skin tightening include infrared lasers and radiofrequency technology.

"There are many lasers we can use for skin of color," he said. "The key is to find a laser that you're comfortable with. Become an expert with that laser and go forward. I don't treat skin of color with vascular lasers, resurfacing lasers, or with intense pulsed light. I don't trust most parameters supplied by the manufacturers. I find my own, safe parameters. I treat more conservatively, and I do not cause erythema or edema."

Aggressive skin cooling is key, he said, and can include ice packs, cold gel, cold liquid, cold air flow, a copper plate, and sapphire windows. "We all get side effects when our skin temperature goes past 45° C," said Dr. Battle, who is also on the dermatology faculty at Howard University, Washington. "By using longer pulse durations, and thus pouring the energy in slower, I'm able to remove heat from the skin more effectively and more efficiently. Longer pulse durations are by far the safest way to treat skin of color."

More than two-thirds of Dr. Battle's patients have darker skin. Between 2002 and 2009, the two most popular nonsurgical procedures in his practice were laser hair removal and laser complexion blending, followed by Botox injections, laser skin rejuvenation, fillers, and laser skin tightening.

Lasers "have come a long way in the last decade," he said.

If side effects occur "show compassion and empathy," Dr. Battle noted. "Allow time to help, and always be available to your patients, even if it means giving them your cell phone number."

Dr. Battle disclosed that he has received equipment, discounts, and honoraria from a number of medical device companies.

PHOENIX - Using laser technology to treat patients requires not only paying attention to the color of their skin, but also to the patient's ethnicity, according to Dr. Eliot F. Battle Jr.

"In my practice we don't just talk about skin of color anymore," Dr. Battle said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. "We talk about skin of cultures. It's not just their skin color but their ethnicity also makes a difference."

He explained that African Americans "have different combinations of black, white, Latin, Spanish, and Indian. Is my ethnicity a mixture of Nigerian, Italian, and Cherokee Indian, or am I a mixture of Cameroonian, Spanish, and Creek Indian? The future of this field, to improve the way we treat people, is going to appreciate more ethnicity as it relates to skin of color."

Brown skin "competes for the light of the laser, because melanin is absorbed across most of the photobiological spectrum, and we are a diverse population of people," said Dr. Battle, who said that he is a mix of Saharan African, Indo-European, and Asian. "To safely treat skin of color we have to use lower wavelengths, lower fluences, lower pulse durations, and aggressive epidermal cooling."

When he treats skin of color, Dr. Battle, a cosmetic dermatologist and laser

surgeon who is director of Cultura Cosmetic Medical Spa in Washington, normally favors an integrated approach and often combines laser treatments, medical skin care, and facial injectables.

For safe laser-hair removal in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI, Dr. Battle recommends using a long-pulsed diode laser and the long-pulsed Nd:YAG laser.

Safe lasers for complexion blending and skin rejuvenation to improve texture include the microsecond Nd:YAG laser, fractional therapy, the excimer laser, the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, and the potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) laser, while safe lasers for skin tightening include infrared lasers and radiofrequency technology.

"There are many lasers we can use for skin of color," he said. "The key is to find a laser that you're comfortable with. Become an expert with that laser and go forward. I don't treat skin of color with vascular lasers, resurfacing lasers, or with intense pulsed light. I don't trust most parameters supplied by the manufacturers. I find my own, safe parameters. I treat more conservatively, and I do not cause erythema or edema."

Aggressive skin cooling is key, he said, and can include ice packs, cold gel, cold liquid, cold air flow, a copper plate, and sapphire windows. "We all get side effects when our skin temperature goes past 45° C," said Dr. Battle, who is also on the dermatology faculty at Howard University, Washington. "By using longer pulse durations, and thus pouring the energy in slower, I'm able to remove heat from the skin more effectively and more efficiently. Longer pulse durations are by far the safest way to treat skin of color."

More than two-thirds of Dr. Battle's patients have darker skin. Between 2002 and 2009, the two most popular nonsurgical procedures in his practice were laser hair removal and laser complexion blending, followed by Botox injections, laser skin rejuvenation, fillers, and laser skin tightening.

Lasers "have come a long way in the last decade," he said.

If side effects occur "show compassion and empathy," Dr. Battle noted. "Allow time to help, and always be available to your patients, even if it means giving them your cell phone number."

Dr. Battle disclosed that he has received equipment, discounts, and honoraria from a number of medical device companies.

ASLMS: Complexion Blending Tops Hair Removal in Skin of Color Practice

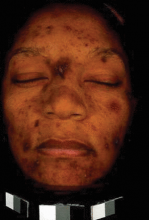

PHOENIX - In the last 2 years, complexion blending has been the most sought-after procedure in Dr. Eliot F. Battle Jr.'s practice.

One of his favorite devices for treating dark spots, melasma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and scarring is the microsecond Nd:YAG laser. With this device, "we're driving heat down deep and trying to break up pigment … that's been encapsulated by membranes," Dr. Battle said. "For a dark spot to last for months or years, we know there is a pigment problem in the dermis. Fractional technology has also been used, but we treat conservatively. I don't ever use the manufacturer's parameters. I don't cause erythema or edema. I'm always under the threshold of redness and swelling."

Speaking during the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery on laser treatment for skin of color patients, Dr. Battle's take-home advice was to reduce conventional parameters and fluences to avoid erythema and edema.

"There are many lasers to use on Caucasians for complexion blending," he said.

"For skin of color, we're limited to the microsecond Nd:YAG, Q-switched Nd:YAG, KTP [potassium-titanyl-phosphate], and infrared lasers."

Prior to treatment he asks patients about their ethnic background because ethnicity plays as much a role in how their skin reacts as their skin color, he said.

He also gets a sun protection history to find out whether he will be treating brown skin that is sun protected, as is the case with some people of Pacific-Asian ancestry, or whether he will be treating brown skin that has been suntanned, as is the case with some people of African-American ancestry.

"Don't make assumptions," he said. "Don't think that the person in front of you, who has the same skin color as the person you just treated, has the same response to lasers, because the ethnicity of the patient dictates how the skin reacts as much as their skin color."

He also recommends investing in an imaging system, such as the VISIA Complexion Analysis system, "that allows us to see what we're treating."

To maximize results of complexion blending, consider concomitant nonlaser "old-school" treatments, such as aesthetic peels, hydroquinone, and a hyfrecator, he said.

"The true art of cosmetic therapy is integrating spa treatments, cosmeceuticals,

prescription medications, and lasers all together," remarked Dr. Battle, who is also on the dermatology faculty at Howard University, Washington. "Lasers don't speak for themselves, particularly when treating pigmented lesions such as melasma and dark spots. We really have to take advantage of the product side of this, also. We have most of our patients on alpha hydroxy acids, Retin A, vitamin C, and we use hydroquinone bleaching cream up to 12%. I'm not bashful with hydroquinone. I monitor them very closely, but I think our patients can benefit from a higher strength."

Dr. Battle disclosed that he has received equipment, discounts, and honoraria from numerous medical device companies, including Canfield.

PHOENIX - In the last 2 years, complexion blending has been the most sought-after procedure in Dr. Eliot F. Battle Jr.'s practice.

One of his favorite devices for treating dark spots, melasma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and scarring is the microsecond Nd:YAG laser. With this device, "we're driving heat down deep and trying to break up pigment … that's been encapsulated by membranes," Dr. Battle said. "For a dark spot to last for months or years, we know there is a pigment problem in the dermis. Fractional technology has also been used, but we treat conservatively. I don't ever use the manufacturer's parameters. I don't cause erythema or edema. I'm always under the threshold of redness and swelling."

Speaking during the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery on laser treatment for skin of color patients, Dr. Battle's take-home advice was to reduce conventional parameters and fluences to avoid erythema and edema.

"There are many lasers to use on Caucasians for complexion blending," he said.

"For skin of color, we're limited to the microsecond Nd:YAG, Q-switched Nd:YAG, KTP [potassium-titanyl-phosphate], and infrared lasers."

Prior to treatment he asks patients about their ethnic background because ethnicity plays as much a role in how their skin reacts as their skin color, he said.

He also gets a sun protection history to find out whether he will be treating brown skin that is sun protected, as is the case with some people of Pacific-Asian ancestry, or whether he will be treating brown skin that has been suntanned, as is the case with some people of African-American ancestry.

"Don't make assumptions," he said. "Don't think that the person in front of you, who has the same skin color as the person you just treated, has the same response to lasers, because the ethnicity of the patient dictates how the skin reacts as much as their skin color."

He also recommends investing in an imaging system, such as the VISIA Complexion Analysis system, "that allows us to see what we're treating."

To maximize results of complexion blending, consider concomitant nonlaser "old-school" treatments, such as aesthetic peels, hydroquinone, and a hyfrecator, he said.

"The true art of cosmetic therapy is integrating spa treatments, cosmeceuticals,

prescription medications, and lasers all together," remarked Dr. Battle, who is also on the dermatology faculty at Howard University, Washington. "Lasers don't speak for themselves, particularly when treating pigmented lesions such as melasma and dark spots. We really have to take advantage of the product side of this, also. We have most of our patients on alpha hydroxy acids, Retin A, vitamin C, and we use hydroquinone bleaching cream up to 12%. I'm not bashful with hydroquinone. I monitor them very closely, but I think our patients can benefit from a higher strength."

Dr. Battle disclosed that he has received equipment, discounts, and honoraria from numerous medical device companies, including Canfield.

PHOENIX - In the last 2 years, complexion blending has been the most sought-after procedure in Dr. Eliot F. Battle Jr.'s practice.

One of his favorite devices for treating dark spots, melasma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and scarring is the microsecond Nd:YAG laser. With this device, "we're driving heat down deep and trying to break up pigment … that's been encapsulated by membranes," Dr. Battle said. "For a dark spot to last for months or years, we know there is a pigment problem in the dermis. Fractional technology has also been used, but we treat conservatively. I don't ever use the manufacturer's parameters. I don't cause erythema or edema. I'm always under the threshold of redness and swelling."

Speaking during the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery on laser treatment for skin of color patients, Dr. Battle's take-home advice was to reduce conventional parameters and fluences to avoid erythema and edema.

"There are many lasers to use on Caucasians for complexion blending," he said.

"For skin of color, we're limited to the microsecond Nd:YAG, Q-switched Nd:YAG, KTP [potassium-titanyl-phosphate], and infrared lasers."

Prior to treatment he asks patients about their ethnic background because ethnicity plays as much a role in how their skin reacts as their skin color, he said.

He also gets a sun protection history to find out whether he will be treating brown skin that is sun protected, as is the case with some people of Pacific-Asian ancestry, or whether he will be treating brown skin that has been suntanned, as is the case with some people of African-American ancestry.

"Don't make assumptions," he said. "Don't think that the person in front of you, who has the same skin color as the person you just treated, has the same response to lasers, because the ethnicity of the patient dictates how the skin reacts as much as their skin color."

He also recommends investing in an imaging system, such as the VISIA Complexion Analysis system, "that allows us to see what we're treating."

To maximize results of complexion blending, consider concomitant nonlaser "old-school" treatments, such as aesthetic peels, hydroquinone, and a hyfrecator, he said.

"The true art of cosmetic therapy is integrating spa treatments, cosmeceuticals,

prescription medications, and lasers all together," remarked Dr. Battle, who is also on the dermatology faculty at Howard University, Washington. "Lasers don't speak for themselves, particularly when treating pigmented lesions such as melasma and dark spots. We really have to take advantage of the product side of this, also. We have most of our patients on alpha hydroxy acids, Retin A, vitamin C, and we use hydroquinone bleaching cream up to 12%. I'm not bashful with hydroquinone. I monitor them very closely, but I think our patients can benefit from a higher strength."

Dr. Battle disclosed that he has received equipment, discounts, and honoraria from numerous medical device companies, including Canfield.

10 Genetic Loci Linked to Vitiligo

Ten different gene susceptibility loci have been identified as associated with generalized vitiligo, in a study published online April 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many of the loci are also associated with other autoimmune diseases, several of which have been linked epidemiologically with vitiligo, said Dr. Ying Jin, of the Human Medical Genetics Program at the University of Colorado, Aurora, and associates.

Generalized vitiligo, which results from the autoimmune loss of melanocytes, has been assumed to arise from the effects of multiple susceptibility genes and unknown environmental factors. Dr. Jin and colleagues performed a genome-wide association study to identify the genetic loci, genotyping 1,514 patients in North America and the United Kingdom who were of white European ancestry.

A total of 579,146 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of these subjects were compared with those of 2,813 unaffected control subjects from a National Institutes of Health database. Genotyping of the SNPs that showed genome-wide significance or near significance was then carried out in two replication studies: one comprised 677 patients and 1,106 controls, and the other comprised 183 simplex trios with the disorder and 332 multiplex families.

Generalized vitiligo was significantly associated with SNPs at or near the HLA-A*02 allele and the HLA-DRB1*04 allele, both of which have been reported previously to be associated with other autoimmune diseases.

Generalized vitiligo also was associated with the following genes: RERE (highly expressed in lymphoid cells and thought to regulate apoptosis), PTPN22 (involved in T-cell-receptor signaling), LPP (associated with celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis), IL2RA (associated with type 1 diabetes, Graves' disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus), GZMB (involved in immune-induced apoptosis), UBASH3A (associated with T-cell signalling and type 1 diabetes), C1QTNF6, and TYR.

"Most of these genes encode immune-system proteins involved in the biologic pathways that probably influence the development of autoimmunity," the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 April 21 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908547]).

The exception - the TYR gene - was "perhaps the most interesting association that we found," they noted.

The TYR gene encodes tyrosinase, which is not a component of the immune system but "is an enzyme of the melanocyte that catalyzes the rate-limiting steps of melanin biosynthesis. It is also a major autoantigen in generalized vitiligo."

The TYR SNPs that were associated with generalized vitiligo also have been associated previously with susceptibility to malignant melanoma, but in a mutually exclusive fashion.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Anna and John Sie Foundation. No relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

Ten different gene susceptibility loci have been identified as associated with generalized vitiligo, in a study published online April 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many of the loci are also associated with other autoimmune diseases, several of which have been linked epidemiologically with vitiligo, said Dr. Ying Jin, of the Human Medical Genetics Program at the University of Colorado, Aurora, and associates.

Generalized vitiligo, which results from the autoimmune loss of melanocytes, has been assumed to arise from the effects of multiple susceptibility genes and unknown environmental factors. Dr. Jin and colleagues performed a genome-wide association study to identify the genetic loci, genotyping 1,514 patients in North America and the United Kingdom who were of white European ancestry.

A total of 579,146 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of these subjects were compared with those of 2,813 unaffected control subjects from a National Institutes of Health database. Genotyping of the SNPs that showed genome-wide significance or near significance was then carried out in two replication studies: one comprised 677 patients and 1,106 controls, and the other comprised 183 simplex trios with the disorder and 332 multiplex families.

Generalized vitiligo was significantly associated with SNPs at or near the HLA-A*02 allele and the HLA-DRB1*04 allele, both of which have been reported previously to be associated with other autoimmune diseases.

Generalized vitiligo also was associated with the following genes: RERE (highly expressed in lymphoid cells and thought to regulate apoptosis), PTPN22 (involved in T-cell-receptor signaling), LPP (associated with celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis), IL2RA (associated with type 1 diabetes, Graves' disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus), GZMB (involved in immune-induced apoptosis), UBASH3A (associated with T-cell signalling and type 1 diabetes), C1QTNF6, and TYR.

"Most of these genes encode immune-system proteins involved in the biologic pathways that probably influence the development of autoimmunity," the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 April 21 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908547]).

The exception - the TYR gene - was "perhaps the most interesting association that we found," they noted.

The TYR gene encodes tyrosinase, which is not a component of the immune system but "is an enzyme of the melanocyte that catalyzes the rate-limiting steps of melanin biosynthesis. It is also a major autoantigen in generalized vitiligo."

The TYR SNPs that were associated with generalized vitiligo also have been associated previously with susceptibility to malignant melanoma, but in a mutually exclusive fashion.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Anna and John Sie Foundation. No relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

Ten different gene susceptibility loci have been identified as associated with generalized vitiligo, in a study published online April 21 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many of the loci are also associated with other autoimmune diseases, several of which have been linked epidemiologically with vitiligo, said Dr. Ying Jin, of the Human Medical Genetics Program at the University of Colorado, Aurora, and associates.

Generalized vitiligo, which results from the autoimmune loss of melanocytes, has been assumed to arise from the effects of multiple susceptibility genes and unknown environmental factors. Dr. Jin and colleagues performed a genome-wide association study to identify the genetic loci, genotyping 1,514 patients in North America and the United Kingdom who were of white European ancestry.

A total of 579,146 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of these subjects were compared with those of 2,813 unaffected control subjects from a National Institutes of Health database. Genotyping of the SNPs that showed genome-wide significance or near significance was then carried out in two replication studies: one comprised 677 patients and 1,106 controls, and the other comprised 183 simplex trios with the disorder and 332 multiplex families.

Generalized vitiligo was significantly associated with SNPs at or near the HLA-A*02 allele and the HLA-DRB1*04 allele, both of which have been reported previously to be associated with other autoimmune diseases.

Generalized vitiligo also was associated with the following genes: RERE (highly expressed in lymphoid cells and thought to regulate apoptosis), PTPN22 (involved in T-cell-receptor signaling), LPP (associated with celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis), IL2RA (associated with type 1 diabetes, Graves' disease, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus), GZMB (involved in immune-induced apoptosis), UBASH3A (associated with T-cell signalling and type 1 diabetes), C1QTNF6, and TYR.

"Most of these genes encode immune-system proteins involved in the biologic pathways that probably influence the development of autoimmunity," the investigators said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010 April 21 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908547]).

The exception - the TYR gene - was "perhaps the most interesting association that we found," they noted.

The TYR gene encodes tyrosinase, which is not a component of the immune system but "is an enzyme of the melanocyte that catalyzes the rate-limiting steps of melanin biosynthesis. It is also a major autoantigen in generalized vitiligo."

The TYR SNPs that were associated with generalized vitiligo also have been associated previously with susceptibility to malignant melanoma, but in a mutually exclusive fashion.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Anna and John Sie Foundation. No relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

Novel Synthetic Oligopeptide Formulation Offers Nonirritating Cosmetic Alternative for the Treatment of Melasma

AAD: Vitamin D Deficiency Plagues Patients With Skin of Color

Vitamin D deficiency is a particular problem in individuals with skin of color, and screening of these patients should be considered given the growing list of diseases associated with the condition, said Dr. Grimes at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

African Americans have an increased incidence of many of the diseases also linked to vitamin D deficiency, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, aggressive prostate and breast cancer, lupus, tuberculosis, and non-Hodgkins lymphoma, said Dr. Grimes.

Vitamin D deficiency has been shown to be associated with numerous other conditions, including neurocognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, and dermatologic disorders, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, malignant melanoma, and other skin cancers.

In a recent study of 194 African American men undergoing risk assessment for prostate cancer, mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) serum concentrations were 13.7 ng/ml (BMC Public Health 2009;9:191). A concentration lower than 20 ng/ml is considered deficient; concentrations of 21-50 ng/ml are considered insufficient; and concentrations of greater than 50 ng/ml are considered sufficient.

More than 60% of the men in the study had levels less than 15 ng/ml; even 55% of the men ingesting more than 400 IU of vitamin D daily had levels less than 15 ng/ml, said Dr. Grimes, a clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She noted the finding raises the question of whether there is a genetic, racially-induced polymorphism that predisposes African Americans to vitamin D deficiency.

Other studies from around the world have also demonstrated racial and gender differences in regard to vitamin D levels, with significantly lower levels found in African Americans and women.

In a study of 185 patients, Dr. Grimes and her colleagues found the highest vitamin D levels were seen in whites, and the lowest were in those with skin of color. Women had slightly lower levels than men. Sun exposure appeared to be a factor, with about 40% of patients using sunscreen regularly, and most only getting sun exposure on weekends.

Sun exposure is the best source of vitamin D, accounting for 80% to 90% of vitamin D levels, compared with 10% to 20% for dietary intake, said Dr. Grimes. The use of a sunscreen with an SPF of 15 can decrease vitamin D production by 99%.

The problem of vitamin D deficiency has increased over time, perhaps due in part to improved photoprotective and sun-avoidance behaviors. Data from the Centers for Disease Control's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that 25(OH)D concentrations decreased in all ages, both genders, and all racial and ethnic groups between 1988 and 2001, she said. "In patients with [25(OH)D] less than 20 ng/ml, I invariably put them on 2,000 IU of vitamin D daily and have them come back in 3-4 months to check their levels," Dr. Grimes said.

Vitamin D3, the natural form of vitamin D when exposed to sunlight, is superior to vitamin D2, which can be found in a select group of foods, said Dr. Grimes. Doses of up to 5,000 IU are also acceptable.

Patients should be advised about the best sources of dietary vitamin D, including fish liver, fish liver oil, fatty fish like salmon (wild is better than farm raised), egg yolks, and milk, she noted. Also, in patients with skin of color, it may be important to weigh the low risk of developing skin cancer against the risks of vitamin D deficiency.

"It is imperative that we educate patients … I think we need to have a dialogue regarding sunscreen," Dr. Grimes said. If a patient with pigmented skin is using an SPF 75 sunscreen, the wisdom of that should be questioned, as should the value of advising more outdoor activity and sun exposure.

"I don't have the answers … but as clinicians we have to think about these things as we move forward," she said.

Dr. Grimes reported she had no disclosures related to her presentation.

Vitamin D deficiency is a particular problem in individuals with skin of color, and screening of these patients should be considered given the growing list of diseases associated with the condition, said Dr. Grimes at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

African Americans have an increased incidence of many of the diseases also linked to vitamin D deficiency, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, aggressive prostate and breast cancer, lupus, tuberculosis, and non-Hodgkins lymphoma, said Dr. Grimes.

Vitamin D deficiency has been shown to be associated with numerous other conditions, including neurocognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, and dermatologic disorders, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, malignant melanoma, and other skin cancers.

In a recent study of 194 African American men undergoing risk assessment for prostate cancer, mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) serum concentrations were 13.7 ng/ml (BMC Public Health 2009;9:191). A concentration lower than 20 ng/ml is considered deficient; concentrations of 21-50 ng/ml are considered insufficient; and concentrations of greater than 50 ng/ml are considered sufficient.

More than 60% of the men in the study had levels less than 15 ng/ml; even 55% of the men ingesting more than 400 IU of vitamin D daily had levels less than 15 ng/ml, said Dr. Grimes, a clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She noted the finding raises the question of whether there is a genetic, racially-induced polymorphism that predisposes African Americans to vitamin D deficiency.

Other studies from around the world have also demonstrated racial and gender differences in regard to vitamin D levels, with significantly lower levels found in African Americans and women.

In a study of 185 patients, Dr. Grimes and her colleagues found the highest vitamin D levels were seen in whites, and the lowest were in those with skin of color. Women had slightly lower levels than men. Sun exposure appeared to be a factor, with about 40% of patients using sunscreen regularly, and most only getting sun exposure on weekends.

Sun exposure is the best source of vitamin D, accounting for 80% to 90% of vitamin D levels, compared with 10% to 20% for dietary intake, said Dr. Grimes. The use of a sunscreen with an SPF of 15 can decrease vitamin D production by 99%.

The problem of vitamin D deficiency has increased over time, perhaps due in part to improved photoprotective and sun-avoidance behaviors. Data from the Centers for Disease Control's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that 25(OH)D concentrations decreased in all ages, both genders, and all racial and ethnic groups between 1988 and 2001, she said. "In patients with [25(OH)D] less than 20 ng/ml, I invariably put them on 2,000 IU of vitamin D daily and have them come back in 3-4 months to check their levels," Dr. Grimes said.

Vitamin D3, the natural form of vitamin D when exposed to sunlight, is superior to vitamin D2, which can be found in a select group of foods, said Dr. Grimes. Doses of up to 5,000 IU are also acceptable.

Patients should be advised about the best sources of dietary vitamin D, including fish liver, fish liver oil, fatty fish like salmon (wild is better than farm raised), egg yolks, and milk, she noted. Also, in patients with skin of color, it may be important to weigh the low risk of developing skin cancer against the risks of vitamin D deficiency.

"It is imperative that we educate patients … I think we need to have a dialogue regarding sunscreen," Dr. Grimes said. If a patient with pigmented skin is using an SPF 75 sunscreen, the wisdom of that should be questioned, as should the value of advising more outdoor activity and sun exposure.

"I don't have the answers … but as clinicians we have to think about these things as we move forward," she said.

Dr. Grimes reported she had no disclosures related to her presentation.

Vitamin D deficiency is a particular problem in individuals with skin of color, and screening of these patients should be considered given the growing list of diseases associated with the condition, said Dr. Grimes at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

African Americans have an increased incidence of many of the diseases also linked to vitamin D deficiency, including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, aggressive prostate and breast cancer, lupus, tuberculosis, and non-Hodgkins lymphoma, said Dr. Grimes.

Vitamin D deficiency has been shown to be associated with numerous other conditions, including neurocognitive disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, and dermatologic disorders, such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, malignant melanoma, and other skin cancers.

In a recent study of 194 African American men undergoing risk assessment for prostate cancer, mean 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) serum concentrations were 13.7 ng/ml (BMC Public Health 2009;9:191). A concentration lower than 20 ng/ml is considered deficient; concentrations of 21-50 ng/ml are considered insufficient; and concentrations of greater than 50 ng/ml are considered sufficient.

More than 60% of the men in the study had levels less than 15 ng/ml; even 55% of the men ingesting more than 400 IU of vitamin D daily had levels less than 15 ng/ml, said Dr. Grimes, a clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She noted the finding raises the question of whether there is a genetic, racially-induced polymorphism that predisposes African Americans to vitamin D deficiency.

Other studies from around the world have also demonstrated racial and gender differences in regard to vitamin D levels, with significantly lower levels found in African Americans and women.

In a study of 185 patients, Dr. Grimes and her colleagues found the highest vitamin D levels were seen in whites, and the lowest were in those with skin of color. Women had slightly lower levels than men. Sun exposure appeared to be a factor, with about 40% of patients using sunscreen regularly, and most only getting sun exposure on weekends.

Sun exposure is the best source of vitamin D, accounting for 80% to 90% of vitamin D levels, compared with 10% to 20% for dietary intake, said Dr. Grimes. The use of a sunscreen with an SPF of 15 can decrease vitamin D production by 99%.

The problem of vitamin D deficiency has increased over time, perhaps due in part to improved photoprotective and sun-avoidance behaviors. Data from the Centers for Disease Control's National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that 25(OH)D concentrations decreased in all ages, both genders, and all racial and ethnic groups between 1988 and 2001, she said. "In patients with [25(OH)D] less than 20 ng/ml, I invariably put them on 2,000 IU of vitamin D daily and have them come back in 3-4 months to check their levels," Dr. Grimes said.

Vitamin D3, the natural form of vitamin D when exposed to sunlight, is superior to vitamin D2, which can be found in a select group of foods, said Dr. Grimes. Doses of up to 5,000 IU are also acceptable.

Patients should be advised about the best sources of dietary vitamin D, including fish liver, fish liver oil, fatty fish like salmon (wild is better than farm raised), egg yolks, and milk, she noted. Also, in patients with skin of color, it may be important to weigh the low risk of developing skin cancer against the risks of vitamin D deficiency.

"It is imperative that we educate patients … I think we need to have a dialogue regarding sunscreen," Dr. Grimes said. If a patient with pigmented skin is using an SPF 75 sunscreen, the wisdom of that should be questioned, as should the value of advising more outdoor activity and sun exposure.

"I don't have the answers … but as clinicians we have to think about these things as we move forward," she said.

Dr. Grimes reported she had no disclosures related to her presentation.

Skin of Color Society to Meet in Miami

If you would like to learn more about issues in skin of color, and be part of an organization dedicated to promoting awareness and excellence in dermatology, please attend the Skin of Color Society's scientific symposium at the American Academy of Dermatology's annual meeting in Miami this Thursday, March 4, at 2 pm in the Loews Miami Beach Hotel (Ponciana 4 Room).

We hope to see you there!

Lily & Naissan

If you would like to learn more about issues in skin of color, and be part of an organization dedicated to promoting awareness and excellence in dermatology, please attend the Skin of Color Society's scientific symposium at the American Academy of Dermatology's annual meeting in Miami this Thursday, March 4, at 2 pm in the Loews Miami Beach Hotel (Ponciana 4 Room).

We hope to see you there!

Lily & Naissan

If you would like to learn more about issues in skin of color, and be part of an organization dedicated to promoting awareness and excellence in dermatology, please attend the Skin of Color Society's scientific symposium at the American Academy of Dermatology's annual meeting in Miami this Thursday, March 4, at 2 pm in the Loews Miami Beach Hotel (Ponciana 4 Room).

We hope to see you there!

Lily & Naissan