User login

LARC prolongs interpregnancy intervals but doesn’t cut preterm birth risk

NASHVILLE, TENN. – when used between a first and second pregnancy, results of a retrospective cohort study suggest.

Of 35,754 women who had a first and second live birth between 2005 and 2015 and who received non-emergent care within 10 years of the first birth, 3,083 (9%) had evidence of interpregnancy LARC exposure and were significantly less likely to have short interpregnancy intervals than were 32,671 with either non-LARC contraceptive use or no record of contraceptive-related care (P less than .0001), Sara E. Simonsen, PhD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Intervals in those with intrapartum LARC use were 12 months or less in 4% of women, 13-18 months in 8%, 19-24 months in 11%, and greater than 24 months in 13%.

However, preterm birth, which occurred in 7% of first births and 6% of second births, was not lower among those with LARC exposure vs. those with no contraceptive encounters after adjustment for interpregnancy interval and a number of demographic factors, including education, presence of father, mother’s age, Hispanic ethnicity, fetal anomalies, and preterm birth history (adjusted odds ratio, 1.13), said Dr. Simonsen, a certified nurse midwife at the University of Utah Hospital, Salt Lake City.

“Preterm birth, a live birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, is a major determinant of poor neonatal outcomes,” she and her colleagues wrote. “Short interpregnancy interval, defined as less than 18 months, is an important risk factor for preterm birth.”

Given the increasing number of U.S. women who use highly effective LARCs to space pregnancies, she and her colleagues performed a retrospective cohort study of electronic medical records from two large health systems and linked them with birth and fetal death records to explore the relationship between interpregnancy LARC and both interpregnancy interval and preterm birth in the subsequent pregnancy.

“We did find that women who used LARC between their pregnancies were less likely to have a short interpregnancy interval, but in adjusted models ... we found no association with intrapartum LARC use and preterm birth in the second birth,” Dr. Simonsen said during an e-poster presentation at the meeting.

In fact, preterm birth in the second birth was most strongly associated with a prior preterm birth – a finding consistent with the literature, she and her colleagues noted.

Although the findings are limited by the use of retrospective data not designed for research, the data came from a large population-based sample representing about 85% of Utah births, they said.

The findings suggest that while LARC use may not reduce preterm birth risk, it “may contribute favorably to outcomes to the extent that having optimal interpregnancy interval does,” they wrote.

“‘We feel that these findings support providers counseling women on the full range of contraception options in the postpartum and not pushing [intrauterine devices,]” Dr. Simonsen added.

The related topic of immediate postpartum LARC use was addressed by Eve Espey, MD, in a separate presentation at the meeting.

Dr .Espey, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the family planning fellowship at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, reported that immediate postpartum insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) is highly cost-effective despite an expulsion rate of between 10% and 30%. She also addressed the value of postpartum LARC for reducing rapid-repeat pregnancy rates.

Payment models for immediate postpartum LARC are “very cumbersome,” but at the university, a persistent effort over 4 years has led to success. Immediate postpartum LARC is offered to women with Medicaid coverage, and payment is received in about 97% of cases, she said, adding that efforts are underway to help other hospitals “troubleshoot the issues.”

The lack of private insurance coverage for immediate postpartum LARC remains a challenge, but Dr. Espey said she remains “super enthusiastic” about its use.

“I think it’s going to take another 5 years or so [for better coverage], and honestly I think what we really need is an inpatient LARC CPT code to make this happen,” she said, urging colleagues to advocate for that within their American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists sections when possible.

Dr. Simonsen and Dr. Espey reported having no relevant disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – when used between a first and second pregnancy, results of a retrospective cohort study suggest.

Of 35,754 women who had a first and second live birth between 2005 and 2015 and who received non-emergent care within 10 years of the first birth, 3,083 (9%) had evidence of interpregnancy LARC exposure and were significantly less likely to have short interpregnancy intervals than were 32,671 with either non-LARC contraceptive use or no record of contraceptive-related care (P less than .0001), Sara E. Simonsen, PhD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Intervals in those with intrapartum LARC use were 12 months or less in 4% of women, 13-18 months in 8%, 19-24 months in 11%, and greater than 24 months in 13%.

However, preterm birth, which occurred in 7% of first births and 6% of second births, was not lower among those with LARC exposure vs. those with no contraceptive encounters after adjustment for interpregnancy interval and a number of demographic factors, including education, presence of father, mother’s age, Hispanic ethnicity, fetal anomalies, and preterm birth history (adjusted odds ratio, 1.13), said Dr. Simonsen, a certified nurse midwife at the University of Utah Hospital, Salt Lake City.

“Preterm birth, a live birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, is a major determinant of poor neonatal outcomes,” she and her colleagues wrote. “Short interpregnancy interval, defined as less than 18 months, is an important risk factor for preterm birth.”

Given the increasing number of U.S. women who use highly effective LARCs to space pregnancies, she and her colleagues performed a retrospective cohort study of electronic medical records from two large health systems and linked them with birth and fetal death records to explore the relationship between interpregnancy LARC and both interpregnancy interval and preterm birth in the subsequent pregnancy.

“We did find that women who used LARC between their pregnancies were less likely to have a short interpregnancy interval, but in adjusted models ... we found no association with intrapartum LARC use and preterm birth in the second birth,” Dr. Simonsen said during an e-poster presentation at the meeting.

In fact, preterm birth in the second birth was most strongly associated with a prior preterm birth – a finding consistent with the literature, she and her colleagues noted.

Although the findings are limited by the use of retrospective data not designed for research, the data came from a large population-based sample representing about 85% of Utah births, they said.

The findings suggest that while LARC use may not reduce preterm birth risk, it “may contribute favorably to outcomes to the extent that having optimal interpregnancy interval does,” they wrote.

“‘We feel that these findings support providers counseling women on the full range of contraception options in the postpartum and not pushing [intrauterine devices,]” Dr. Simonsen added.

The related topic of immediate postpartum LARC use was addressed by Eve Espey, MD, in a separate presentation at the meeting.

Dr .Espey, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the family planning fellowship at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, reported that immediate postpartum insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) is highly cost-effective despite an expulsion rate of between 10% and 30%. She also addressed the value of postpartum LARC for reducing rapid-repeat pregnancy rates.

Payment models for immediate postpartum LARC are “very cumbersome,” but at the university, a persistent effort over 4 years has led to success. Immediate postpartum LARC is offered to women with Medicaid coverage, and payment is received in about 97% of cases, she said, adding that efforts are underway to help other hospitals “troubleshoot the issues.”

The lack of private insurance coverage for immediate postpartum LARC remains a challenge, but Dr. Espey said she remains “super enthusiastic” about its use.

“I think it’s going to take another 5 years or so [for better coverage], and honestly I think what we really need is an inpatient LARC CPT code to make this happen,” she said, urging colleagues to advocate for that within their American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists sections when possible.

Dr. Simonsen and Dr. Espey reported having no relevant disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – when used between a first and second pregnancy, results of a retrospective cohort study suggest.

Of 35,754 women who had a first and second live birth between 2005 and 2015 and who received non-emergent care within 10 years of the first birth, 3,083 (9%) had evidence of interpregnancy LARC exposure and were significantly less likely to have short interpregnancy intervals than were 32,671 with either non-LARC contraceptive use or no record of contraceptive-related care (P less than .0001), Sara E. Simonsen, PhD, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Intervals in those with intrapartum LARC use were 12 months or less in 4% of women, 13-18 months in 8%, 19-24 months in 11%, and greater than 24 months in 13%.

However, preterm birth, which occurred in 7% of first births and 6% of second births, was not lower among those with LARC exposure vs. those with no contraceptive encounters after adjustment for interpregnancy interval and a number of demographic factors, including education, presence of father, mother’s age, Hispanic ethnicity, fetal anomalies, and preterm birth history (adjusted odds ratio, 1.13), said Dr. Simonsen, a certified nurse midwife at the University of Utah Hospital, Salt Lake City.

“Preterm birth, a live birth at less than 37 weeks’ gestation, is a major determinant of poor neonatal outcomes,” she and her colleagues wrote. “Short interpregnancy interval, defined as less than 18 months, is an important risk factor for preterm birth.”

Given the increasing number of U.S. women who use highly effective LARCs to space pregnancies, she and her colleagues performed a retrospective cohort study of electronic medical records from two large health systems and linked them with birth and fetal death records to explore the relationship between interpregnancy LARC and both interpregnancy interval and preterm birth in the subsequent pregnancy.

“We did find that women who used LARC between their pregnancies were less likely to have a short interpregnancy interval, but in adjusted models ... we found no association with intrapartum LARC use and preterm birth in the second birth,” Dr. Simonsen said during an e-poster presentation at the meeting.

In fact, preterm birth in the second birth was most strongly associated with a prior preterm birth – a finding consistent with the literature, she and her colleagues noted.

Although the findings are limited by the use of retrospective data not designed for research, the data came from a large population-based sample representing about 85% of Utah births, they said.

The findings suggest that while LARC use may not reduce preterm birth risk, it “may contribute favorably to outcomes to the extent that having optimal interpregnancy interval does,” they wrote.

“‘We feel that these findings support providers counseling women on the full range of contraception options in the postpartum and not pushing [intrauterine devices,]” Dr. Simonsen added.

The related topic of immediate postpartum LARC use was addressed by Eve Espey, MD, in a separate presentation at the meeting.

Dr .Espey, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the family planning fellowship at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, reported that immediate postpartum insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) is highly cost-effective despite an expulsion rate of between 10% and 30%. She also addressed the value of postpartum LARC for reducing rapid-repeat pregnancy rates.

Payment models for immediate postpartum LARC are “very cumbersome,” but at the university, a persistent effort over 4 years has led to success. Immediate postpartum LARC is offered to women with Medicaid coverage, and payment is received in about 97% of cases, she said, adding that efforts are underway to help other hospitals “troubleshoot the issues.”

The lack of private insurance coverage for immediate postpartum LARC remains a challenge, but Dr. Espey said she remains “super enthusiastic” about its use.

“I think it’s going to take another 5 years or so [for better coverage], and honestly I think what we really need is an inpatient LARC CPT code to make this happen,” she said, urging colleagues to advocate for that within their American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists sections when possible.

Dr. Simonsen and Dr. Espey reported having no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

Diverse vaginal microbiome may signal risk for preterm birth

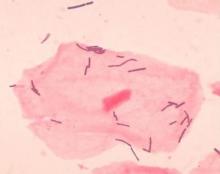

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

in an analysis of approximately 12,000 samples, according to a study published in Nature Medicine.

Preterm births, defined as less than 37 weeks’ gestation, remain the second most common cause of neonatal death worldwide, but few strategies exist to prevent and predict preterm birth (PTB) wrote Jennifer M. Fettweis, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, and her colleagues. In the United States, women of African ancestry are at significantly greater risk for PTB.

A highly diverse vaginal microbiome is thought to be associated with an increased risk of inflammation, infection, and PTB, “however, many asymptomatic healthy women have diverse vaginal microbiota,” the researchers said.

To identify vaginal microbiota distinct to women who experienced PTB, the researchers analyzed data from the Multi-Omic Microbiome Study: Pregnancy Initiative (MOMS-PI), part of the National Institutes of Health–sponsored Integrative Human Microbiome Project. The MOMS-PI study included 12,039 samples of vaginal flora from 597 pregnancies; the analysis included 45 singleton pregnancies that met the criteria for spontaneous PTB (23-36 weeks, 6 days of gestation) and 90 case-matched full-term singleton pregnancies (greater than or equal to 39 weeks). Approximately 78% of the women were of African descent in both groups, and their average age was 26 years in both groups.

Overall, the diversity of the vaginal microbiome was greater among women who experienced PTB, compared with term birth (TB). Women who experienced PTB had less Lactobacillus crispatus, but more bacterial vaginosis–associated bacterium-1 (BVAB1), Prevotella cluster 2, and Sneathia amnii, compared with TB women.

Of note, vaginal cytokine data showed that proinflammatory cytokines, which may be associated with the induction of labor, may be prompted by inflammation in the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Fettweis and her associates said. “We observed that vaginal IP-10/CXCL10 levels were inversely correlated with BVAB1 in PTB, inversely correlated with L. crispatus in TB, and positively correlated with L. iners in TB, suggesting complex host-microbiome interactions in pregnancy,” they said.

“Further studies are needed to determine whether the signatures of PTB reported in the present study replicate in other cohorts of women of African ancestry, to examine whether the observed differences in vaginal microbiome composition between women of different ancestries has a direct causal link to the ethnic and racial disparities in PTB rates, and to establish whether population-specific microbial markers can be ultimately integrated into a generalizable spectrum of vaginal microbiome states linked to the risk for PTB,” Dr. Fettweis and her associates said.

In a companion study also published in Nature Medicine, Myrna G. Serrano, MD, also of Virginia Commonwealth University, and her colleagues as part of the MOMS-PI initially determined that vaginal microbiome profiles varied between 613 pregnant and 1,969 nonpregnant women in that “pregnant women had significantly higher prevalence of the four most common Lactobacillus vagitypes (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) and a commensurately lower prevalence of vagitypes dominated by other taxa.” The primary driver of the differences was L. iners.

They then compared vaginal microbiome data from 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant case-matched women of African, Hispanic, or European ancestry, as well as 90 pregnant women (49 of African ancestry and 41 of European) ancestry.

In the subset of 300 pregnant and 300 nonpregnant women, the vaginal microbiome of the pregnant women overall became more dominated by Lactobacillus early in pregnancy. Further stratification by race showed that pregnant women of African and Hispanic ancestry had significantly higher levels of four types of Lactobacillus than their nonpregnant counterparts, but no significant difference was seen between pregnant and nonpregnant women of European ancestry.

“It appears that changes occurring during pregnancy may render the reproductive tracts of women of all racial backgrounds more hospitable to taxa of Lactobacillus and less favorable for Gardnerella vaginalis and other taxa associated with BV [bacterial vaginosis] and dysbiosis,” the researchers said.

“Interestingly, BVAB1, which has been associated with dysbiotic vaginal conditions and risk of PTB, and which is present as a major vagitype largely in women of African ancestry, is not noticeably decreased in prevalence in pregnancy,” Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “Thus, BVAB1, for reasons yet to be determined, is apparently resistant to factors sculpting the microbiome in pregnant women, possibly explaining in part the enhanced risk for PTB experienced by women of African ancestry.”

In a look at the 49 pregnant women of African ancestry and 41 of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had “significantly lower representation of the L. crispatus, L. gasseri and L. jensenii vagitypes, and higher representation of L. iners and BVAB1 vagitypes. Variability in women of African ancestry was driven by BVAB1 and L. iners, whereas variability in women of non-African ancestry was driven by L. crispatus and L. iners. Again, pregnancy had no significant effect on prevalence of the BVAB1 vagitype. Prevalence of Lactobacillus-dominated profiles in women of African ancestry was lower in the first than in later trimesters, whereas women of European ancestry had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus vagitypes throughout pregnancy.”

The presence of vaginal microbiome profiles associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes highlights the need for further studies that take advantage of this information, Dr. Serrano and her associates said. “That the vaginal microbiomes known to confer higher risk of poor health and adverse outcomes of pregnancy are more highly associated with women of African and Hispanic ancestry, but that pregnancy tends to drive these microbiomes toward more favorable microbiota, suggests that an external intervention that favors this trend might be beneficial for these populations,” they concluded. “What remains is to verify the most favorable microbiome and the most effective strategy for intervention.”

Dr. Fettweis had no financial conflicts to disclose; two coauthors are full-time employees at Pacific Biosciences. Dr. Serrano and her coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Serrano’s study received grants from the National Institutes of Health and other sources, as well as support from the Common Fund, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

SOURCES: Fettweis J et al. Nature Medicine 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0450-2; Serrano M et al. Nature Medicine. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0465-8.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

In women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders, does immediate delivery versus expectant management differ in terms of neonatal neurodevelopmental outcomes?

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MT, Broekhuijsen K, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring of mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.024.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In women with mild hypertensive disorders in the preterm period, the maternal benefits of delivery should be weighed against the consequences of preterm birth for the neonate. In a recent study, Zwertbroek and colleagues sought to evaluate the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of this decision on the offspring.

Details of the study

The authors conducted a follow-up study of the randomized, controlled Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term II (HYPITAT-II), in which 704 women diagnosed with late preterm (34–37 weeks) hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, or mild preeclampsia) were randomly assigned to immediate delivery or expectant management.

Expectant management consisted of close monitoring until 37 weeks or until an indication for delivery occurred, whichever came first. Children born to those mothers were eligible for this study (women enrolled during 2011–2015) when they reached 2 years of age; 342 children were included in this analysis. Of note, children from the expectant management group had been delivered at a more advanced gestational age (median, 37.0 vs 36.1 weeks; P<.001) than those in the immediate-delivery group.

Survey tools. Parents completed 2 response surveys, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), between 23 and 26 months’ corrected age. The ASQ is designed to detect developmental delay, while the CBCL assesses behavioral and emotional problems. The primary outcome was an abnormal result on either screen.

Results. Based on 330 returned questionnaires, the authors found more abnormal ASQ scores (45 of 162 [28%] vs 27 of 148 [18%] children; P = .045) in the immediate-delivery group versus the expectant management group, most pronounced in the fine motor domain. They found no difference in the CBCL scores. The authors concluded that immediate delivery for women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders in pregnancy increases the risk of developmental delay in the children.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique as a planned follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial, allowing for 2-year outcomes to be assessed on children of enrolled women with mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period. The authors used validated surveys that are known to predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Continue to: This work has several limitations...

This work has several limitations, however. Randomization was not truly maintained given the less than 50% response rate of original participants. Additionally, parents completed the surveys and provider confirmation of developmental concerns or diagnoses was not obtained. Further, assessments at 2 years of age may be too early to detect subtle differences, with evaluations at 5 years more predictive of long-term outcomes; the authors stated that these data already are being collected.

Finally, while these data importantly reinforce the conclusions of the parent HYPITAT-II trial, which support expectant management for mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period,1 clinicians must always take care to individualize decisions in the face of worsening maternal disease.

This follow-up study of the HYPITAT-II randomized, controlled trial demonstrates poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring of late preterm mild hypertensives who undergo immediate delivery. These data support current practice recommendations to expectantly manage women with late preterm mild hypertensive disease until 37 weeks or signs of clinical worsening, whichever comes first.

- Broekjuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2492-2501.

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MT, Broekhuijsen K, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring of mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.024.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In women with mild hypertensive disorders in the preterm period, the maternal benefits of delivery should be weighed against the consequences of preterm birth for the neonate. In a recent study, Zwertbroek and colleagues sought to evaluate the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of this decision on the offspring.

Details of the study

The authors conducted a follow-up study of the randomized, controlled Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term II (HYPITAT-II), in which 704 women diagnosed with late preterm (34–37 weeks) hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, or mild preeclampsia) were randomly assigned to immediate delivery or expectant management.

Expectant management consisted of close monitoring until 37 weeks or until an indication for delivery occurred, whichever came first. Children born to those mothers were eligible for this study (women enrolled during 2011–2015) when they reached 2 years of age; 342 children were included in this analysis. Of note, children from the expectant management group had been delivered at a more advanced gestational age (median, 37.0 vs 36.1 weeks; P<.001) than those in the immediate-delivery group.

Survey tools. Parents completed 2 response surveys, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), between 23 and 26 months’ corrected age. The ASQ is designed to detect developmental delay, while the CBCL assesses behavioral and emotional problems. The primary outcome was an abnormal result on either screen.

Results. Based on 330 returned questionnaires, the authors found more abnormal ASQ scores (45 of 162 [28%] vs 27 of 148 [18%] children; P = .045) in the immediate-delivery group versus the expectant management group, most pronounced in the fine motor domain. They found no difference in the CBCL scores. The authors concluded that immediate delivery for women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders in pregnancy increases the risk of developmental delay in the children.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique as a planned follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial, allowing for 2-year outcomes to be assessed on children of enrolled women with mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period. The authors used validated surveys that are known to predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Continue to: This work has several limitations...

This work has several limitations, however. Randomization was not truly maintained given the less than 50% response rate of original participants. Additionally, parents completed the surveys and provider confirmation of developmental concerns or diagnoses was not obtained. Further, assessments at 2 years of age may be too early to detect subtle differences, with evaluations at 5 years more predictive of long-term outcomes; the authors stated that these data already are being collected.

Finally, while these data importantly reinforce the conclusions of the parent HYPITAT-II trial, which support expectant management for mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period,1 clinicians must always take care to individualize decisions in the face of worsening maternal disease.

This follow-up study of the HYPITAT-II randomized, controlled trial demonstrates poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring of late preterm mild hypertensives who undergo immediate delivery. These data support current practice recommendations to expectantly manage women with late preterm mild hypertensive disease until 37 weeks or signs of clinical worsening, whichever comes first.

Zwertbroek EF, Franssen MT, Broekhuijsen K, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Neonatal developmental and behavioral outcomes of immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring of mild hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: 2-year outcomes of the HYPITAT-II trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.03.024.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

In women with mild hypertensive disorders in the preterm period, the maternal benefits of delivery should be weighed against the consequences of preterm birth for the neonate. In a recent study, Zwertbroek and colleagues sought to evaluate the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of this decision on the offspring.

Details of the study

The authors conducted a follow-up study of the randomized, controlled Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial At Term II (HYPITAT-II), in which 704 women diagnosed with late preterm (34–37 weeks) hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, or mild preeclampsia) were randomly assigned to immediate delivery or expectant management.

Expectant management consisted of close monitoring until 37 weeks or until an indication for delivery occurred, whichever came first. Children born to those mothers were eligible for this study (women enrolled during 2011–2015) when they reached 2 years of age; 342 children were included in this analysis. Of note, children from the expectant management group had been delivered at a more advanced gestational age (median, 37.0 vs 36.1 weeks; P<.001) than those in the immediate-delivery group.

Survey tools. Parents completed 2 response surveys, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), between 23 and 26 months’ corrected age. The ASQ is designed to detect developmental delay, while the CBCL assesses behavioral and emotional problems. The primary outcome was an abnormal result on either screen.

Results. Based on 330 returned questionnaires, the authors found more abnormal ASQ scores (45 of 162 [28%] vs 27 of 148 [18%] children; P = .045) in the immediate-delivery group versus the expectant management group, most pronounced in the fine motor domain. They found no difference in the CBCL scores. The authors concluded that immediate delivery for women with late preterm mild hypertensive disorders in pregnancy increases the risk of developmental delay in the children.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique as a planned follow-up to a randomized, controlled trial, allowing for 2-year outcomes to be assessed on children of enrolled women with mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period. The authors used validated surveys that are known to predict long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Continue to: This work has several limitations...

This work has several limitations, however. Randomization was not truly maintained given the less than 50% response rate of original participants. Additionally, parents completed the surveys and provider confirmation of developmental concerns or diagnoses was not obtained. Further, assessments at 2 years of age may be too early to detect subtle differences, with evaluations at 5 years more predictive of long-term outcomes; the authors stated that these data already are being collected.

Finally, while these data importantly reinforce the conclusions of the parent HYPITAT-II trial, which support expectant management for mild hypertensive disorders in the late preterm period,1 clinicians must always take care to individualize decisions in the face of worsening maternal disease.

This follow-up study of the HYPITAT-II randomized, controlled trial demonstrates poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring of late preterm mild hypertensives who undergo immediate delivery. These data support current practice recommendations to expectantly manage women with late preterm mild hypertensive disease until 37 weeks or signs of clinical worsening, whichever comes first.

- Broekjuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2492-2501.

- Broekjuijsen K, van Baaren GJ, van Pampus MG, et al; HYPITAT-II Study Group. Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2492-2501.

Marijuana during prenatal OUD treatment increases premature birth

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

BALTIMORE – Marijuana is a not a good idea during pregnancy, and it’s an even worse idea when women are being treated for opioid addiction, according to an investigation from East Tennessee State University, Mountain Home.

Marijuana use may become more common as legalization rolls out across the country, and legalization, in turn, may add to the perception that pot is harmless, and maybe a good way to take the edge off during pregnancy and prevent morning sickness, said neonatologist Darshan Shaw, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the university.

Dr. Shaw wondered how that trend might impact treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) during pregnancy, which has also become more common. The take-home is that “if you have a pregnant patient on medically assistant therapy” for opioid addition, “you should warn them against use of marijuana. It increases the risk of prematurity and low birth weight,” he said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

He and his team reviewed 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals in south-central Appalachia from July 2011 to June 2016. All of the women had used opioids during pregnancy, some illegally and others for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment or other medical issues; 108 had urine screens that were positive for tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) at the time of delivery.

Infants were born a mean of 3 days earlier in the marijuana group, and a mean of 265 g lighter. They were also more likely to be born before 37 weeks’ gestation (14% versus 6.5%); born weighing less than 2,500 g (17.6% versus 7.3%); and more likely to be admitted to the neonatal ICU (17.5% versus 7.1%).

On logistic regression to control for parity, maternal status, and tobacco and benzodiazepine use, prenatal marijuana exposure more than doubled the risk of prematurity (odds ratio, 2.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.3-4.23); tobacco and benzodiazepines did not increase the risk. Marijuana also doubled the risk of low birth weight (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.18-3.47), about the same as tobacco and benzodiazepines.

The study had limitations. There was no controlling for a major confounder: the amount of opioids woman took while pregnant. These data were not available, Dr. Shaw said.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome was more common in the marijuana group (33.3% versus 18.1%), so it’s possible that women who used marijuana also used more opioids. “We suspect that opioid exposure was not uniform among all infants,” he said. There were also no data on the amount or way marijuana was used.

Marijuana-positive women were more likely to be unmarried, nulliparous, and use tobacco and benzodiazepines.

There was no industry funding for the work, and Dr. Shaw had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Key clinical point: Warn pregnant women being treated for opioid use disorder to stay away from marijuana.

Major finding: Marijuana use more than doubled the risk of prematurity and low birth weight.

Study details: Review of 2,375 opioid-exposed pregnancies at six hospitals

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the lead investigator had no disclosures.

Antenatal steroids for preterm birth is cost effective

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

Administering antenatal corticosteroids to pregnant women at high risk for preterm birth was a cost-effective intervention that improved infant respiratory outcomes, according to a new study.

“This intervention has a potential cost saving in the United States of approximately $100 million dollars annually from the benefit in the immediate neonatal outcome alone,” Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and her associates reported in JAMA Pediatrics. “Because late preterm birth comprises a large proportion of all preterm births, our findings have the potential for a large influence on public health.”

The researchers conducted a retrospective secondary analysis of the randomized Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) clinical trial October 2010 to February 2015. The trial enrolled randomly assigned antenatal administration of betamethasone or placebo to women pregnant with a singleton and at high risk for preterm birth while between 34 weeks, 6 days, and 36 weeks, 0 days, of gestation.

Antenatal corticosteroid administration was regarded as effective if a newborn did not require treatment in the first 72 hours for respiratory distress or illness. Treatment could include “continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for 2 hours or more, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 30% or more for 4 hours or more, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or mechanical ventilation,” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates wrote.

To tally the costs, the researchers used Medicaid rates to estimate the total in 2015 U.S. dollars for betamethasone, outpatient visits or inpatient stays to administer it, and all direct newborn care costs, including neonatal ICU daily costs stratified by respiratory illness severity. Betamethasone administration included an initial 12-mg intramuscular dose followed by another after 24 hours if the infant had not been delivered.

“Because therapy often persists for longer than this 72-hour duration, we measured costs through hospital discharge,” the authors wrote. “The analysis took the perspective of a third-party payer in which we included direct medical costs and associated overhead accruing to hospitals and medical payers for the care of enrolled patients and their infants.”

Among 2,821 mothers not lost to follow-up during the secondary analysis, 1,426 received betamethasone and 1,395 received placebo. For mothers who received betamethasone antenatally, the total mean cost was $4,681 per mother-infant pair. Total mean cost for those in the placebo group was $5,379 per pair, resulting in a significant mean $698 savings (P = .02). Respiratory morbidity was 2.9% lower in infants whose mothers received antenatal corticosteroid treatment.

“Thus, because the treated group had lower costs and this strategy was more effective, administration of betamethasone to women at risk for late preterm birth was judged to be a dominant strategy, which is defined as one in which costs are lower and effectiveness is higher than a comparator (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER], −23 986),” Dr. Gyamfi-Bannerman and her associates reported. ICER is defined as the difference in mean total cost per patient in the betamethasone and placebo arms divided by the difference in the effectiveness.

Study limitations were an inability to estimate costs according to quality-adjusted life years or to include families’/caregivers’ costs.

SOURCE: Gyamfi-Bannerman C. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Mar 11. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0032.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation reduces risk of preterm birth

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).

With regard to infant health, use of omega-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy was associated in 10 RCTs (7,416 women) with a potential reduced risk of perinatal mortality (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.03) and, in 9 RCTs (6,920 women), a reduced risk of neonatal intensive care admission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.03). The researchers noted that omega-3 use in 15 trials (8,449 women) was potentially associated with a reduced number of babies with low birth weight (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99), but an increase in babies who were large for their gestational age in 3,722 women from 6 RCTs (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97-1.36). There was no significant difference among groups with regard to babies who were born small for their gestational age or in uterine growth restriction, they said.

While maternal outcomes were examined, Dr. Middleton and her colleagues found no significant differences between groups in factors such as postterm induction, serious adverse events, admission to intensive care, and postnatal depression.

“Ultimately, we hope this review will make a real contribution to the evidence base we need to reduce premature births, which continue to be one of the most pressing and intractable maternal and child health problems in every country around the world,” Dr. Middleton said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).

With regard to infant health, use of omega-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy was associated in 10 RCTs (7,416 women) with a potential reduced risk of perinatal mortality (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.03) and, in 9 RCTs (6,920 women), a reduced risk of neonatal intensive care admission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.03). The researchers noted that omega-3 use in 15 trials (8,449 women) was potentially associated with a reduced number of babies with low birth weight (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99), but an increase in babies who were large for their gestational age in 3,722 women from 6 RCTs (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97-1.36). There was no significant difference among groups with regard to babies who were born small for their gestational age or in uterine growth restriction, they said.

While maternal outcomes were examined, Dr. Middleton and her colleagues found no significant differences between groups in factors such as postterm induction, serious adverse events, admission to intensive care, and postnatal depression.

“Ultimately, we hope this review will make a real contribution to the evidence base we need to reduce premature births, which continue to be one of the most pressing and intractable maternal and child health problems in every country around the world,” Dr. Middleton said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

Taking omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during pregnancy was associated with reduced risk of preterm birth, and also may reduce the risk of babies born at a low birth weight and risk of requiring neonatal intensive care, according to a Cochrane review of 70 randomized controlled trials.

“There are not many options for preventing premature birth, so these new findings are very important for pregnant women, babies, and the health professionals who care for them,” Philippa Middleton, MPH, PhD, of Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, in Adelaide, stated in a press release. “We don’t yet fully understand the causes of premature labor, so predicting and preventing early birth has always been a challenge. This is one of the reasons omega-3 supplementation in pregnancy is of such great interest to researchers around the world.”

Dr. Middleton and her colleagues performed a search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and identified 70 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) where 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), placebo, or no omega-3.

“Many pregnant women in the UK are already taking omega-3 supplements by personal choice rather than as a result of advice from health professionals,” Dr. Middleton said in the release. “It’s worth noting though that many supplements currently on the market don’t contain the optimal dose or type of omega-3 for preventing premature birth. Our review found the optimum dose was a daily supplement containing between 500 and 1,000 milligrams of long-chain omega-3 fats (containing at least 500 mg of DHA [docosahexaenoic acid]) starting at 12 weeks of pregnancy.”

In 26 RCTs (10,304 women), the risk of preterm birth under 37 weeks was 11% lower for women who took omega-3 LCPUFA compared with women who did not take omega-3 (relative risk, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.81-0.97), while the risk for preterm birth under 34 weeks in 9 RCTs (5,204 women) was 42% lower for women compared with women who did not take omega-3 (RR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.44-0.77).

With regard to infant health, use of omega-3 LCPUFA during pregnancy was associated in 10 RCTs (7,416 women) with a potential reduced risk of perinatal mortality (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.54-1.03) and, in 9 RCTs (6,920 women), a reduced risk of neonatal intensive care admission (RR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.83-1.03). The researchers noted that omega-3 use in 15 trials (8,449 women) was potentially associated with a reduced number of babies with low birth weight (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99), but an increase in babies who were large for their gestational age in 3,722 women from 6 RCTs (RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.97-1.36). There was no significant difference among groups with regard to babies who were born small for their gestational age or in uterine growth restriction, they said.

While maternal outcomes were examined, Dr. Middleton and her colleagues found no significant differences between groups in factors such as postterm induction, serious adverse events, admission to intensive care, and postnatal depression.

“Ultimately, we hope this review will make a real contribution to the evidence base we need to reduce premature births, which continue to be one of the most pressing and intractable maternal and child health problems in every country around the world,” Dr. Middleton said.

The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Middleton P et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub3.

FROM COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 26 randomized controlled trials, the risk of preterm birth at 37 weeks (10,304 women) was 11% lower and the risk of preterm birth at 34 weeks (5,204 women) in 9 RCTs was 42% lower for women taking omega-3, compared with women not taking omega-3.

Study details: A Cochrane review of 70 RCTs with a total of 19,927 women at varying levels of risk for preterm birth who received omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, placebo, or no omega-3.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the review. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.