User login

For MD-IQ only

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Prostate Cancer September 2021

In the study by Sternberg et al, radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) and safety were compared between patients aged > 70 and younger than age 70 who were enrolled in the CARD study. In the CARD study, patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) were randomized to cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzlutamide after having failed previous treatment. Patients aged > 70 who received cabazitaxel had a higher rPFS than those who received abiraterone or enzalutamide. Grade > 3 adverse effects were identified in 58% of patients receiving cabazitaxel versus 49% in those receiving abiraterone or enzalutamide.

In the study by Smith et al., quality of life (QoL) as measured via time to deterioration of patient report outcomes (PRO) was evaluated in patients enrolled on the ARAMIS trial (darolutamide versus placebo in patients with non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). PRO was assessed via surveys as an exploratory endpoint in this study via FACT-P PCS (prostate cancer subscale) and EORTC QLQ-PR25. Overall, the findings were consistent with either an overall improvement in QoL or improvement in urinary and bowel symptoms over time. In a separate study, Fallah et al conducted a pooled analysis of survival and safety outcomes of 3 second generation androgen receptor blockers (apalutamide, darolutamide, and enzalutamide) in men with nmCRPC. They compared results for men age under 80 versus those 80 and above. Metastasis-free survival and overall survival were higher for the treatment groups compared with placebo groups for both age categories. Side effects were slightly higher in the group aged 80 and above.

In summary, quality of life is an endpoint of critical importance to patients. Inclusion of patient reported outcomes as measured via surveys that provide quantitative assessments aid providers in discussing treatment options with patients. In addition, such QoL instruments aid in assessments based on age. Age bias is common in oncology, and the included studies provide further evidence that age alone should not be a reason to adjust treatment recommendations. Inclusion of geriatric assessments into such studies may further aid in determining risks and benefits of particular prostate cancer treatments in future studies

In the study by Sternberg et al, radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) and safety were compared between patients aged > 70 and younger than age 70 who were enrolled in the CARD study. In the CARD study, patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) were randomized to cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzlutamide after having failed previous treatment. Patients aged > 70 who received cabazitaxel had a higher rPFS than those who received abiraterone or enzalutamide. Grade > 3 adverse effects were identified in 58% of patients receiving cabazitaxel versus 49% in those receiving abiraterone or enzalutamide.

In the study by Smith et al., quality of life (QoL) as measured via time to deterioration of patient report outcomes (PRO) was evaluated in patients enrolled on the ARAMIS trial (darolutamide versus placebo in patients with non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). PRO was assessed via surveys as an exploratory endpoint in this study via FACT-P PCS (prostate cancer subscale) and EORTC QLQ-PR25. Overall, the findings were consistent with either an overall improvement in QoL or improvement in urinary and bowel symptoms over time. In a separate study, Fallah et al conducted a pooled analysis of survival and safety outcomes of 3 second generation androgen receptor blockers (apalutamide, darolutamide, and enzalutamide) in men with nmCRPC. They compared results for men age under 80 versus those 80 and above. Metastasis-free survival and overall survival were higher for the treatment groups compared with placebo groups for both age categories. Side effects were slightly higher in the group aged 80 and above.

In summary, quality of life is an endpoint of critical importance to patients. Inclusion of patient reported outcomes as measured via surveys that provide quantitative assessments aid providers in discussing treatment options with patients. In addition, such QoL instruments aid in assessments based on age. Age bias is common in oncology, and the included studies provide further evidence that age alone should not be a reason to adjust treatment recommendations. Inclusion of geriatric assessments into such studies may further aid in determining risks and benefits of particular prostate cancer treatments in future studies

In the study by Sternberg et al, radiographic progression-free survival (rPFS) and safety were compared between patients aged > 70 and younger than age 70 who were enrolled in the CARD study. In the CARD study, patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) were randomized to cabazitaxel versus abiraterone or enzlutamide after having failed previous treatment. Patients aged > 70 who received cabazitaxel had a higher rPFS than those who received abiraterone or enzalutamide. Grade > 3 adverse effects were identified in 58% of patients receiving cabazitaxel versus 49% in those receiving abiraterone or enzalutamide.

In the study by Smith et al., quality of life (QoL) as measured via time to deterioration of patient report outcomes (PRO) was evaluated in patients enrolled on the ARAMIS trial (darolutamide versus placebo in patients with non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC). PRO was assessed via surveys as an exploratory endpoint in this study via FACT-P PCS (prostate cancer subscale) and EORTC QLQ-PR25. Overall, the findings were consistent with either an overall improvement in QoL or improvement in urinary and bowel symptoms over time. In a separate study, Fallah et al conducted a pooled analysis of survival and safety outcomes of 3 second generation androgen receptor blockers (apalutamide, darolutamide, and enzalutamide) in men with nmCRPC. They compared results for men age under 80 versus those 80 and above. Metastasis-free survival and overall survival were higher for the treatment groups compared with placebo groups for both age categories. Side effects were slightly higher in the group aged 80 and above.

In summary, quality of life is an endpoint of critical importance to patients. Inclusion of patient reported outcomes as measured via surveys that provide quantitative assessments aid providers in discussing treatment options with patients. In addition, such QoL instruments aid in assessments based on age. Age bias is common in oncology, and the included studies provide further evidence that age alone should not be a reason to adjust treatment recommendations. Inclusion of geriatric assessments into such studies may further aid in determining risks and benefits of particular prostate cancer treatments in future studies

Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer

Health-Related Quality of Life and Toxicity After Definitive High-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy Among Veterans With Prostate Cancer

Nearly 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with cancer within the Veterans Health Administration annually with prostate cancer (PC) being the most frequently diagnosed, accounting for 29% of all cancers diagnosed.1 The treatment of PC depends on the stage and risk group at presentation and patient preference. Men with early stage, localized PC can be managed with prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.2

Within the Veterans Health Administration, more patients are treated with radiation therapy than with radical prostatectomy.3 This is in contrast to the civil health system, where more patients are treated with radical prostatectomy than with radiation therapy.4,5 Radiation therapy for PC can be given externally with external beam radiation therapy or internally with brachytherapy (BT). BT is categorized by the rate at which the radiation dose is delivered and generally grouped as low-dose rate (LDR) or high-dose rate (HDR). LDRBT consists of permanently implanting radioactive seeds, which slowly deliver a radiation dose over an extended period. HDRBT consists of implanting catheters that allow delivery of a radioactive source to be placed temporarily in the prostate and removed after treatment. The utilization of HDRBT has become more common as treatment has evolved to consist of fewer, larger fractions in a shorter time, making it a convenient treatment option for men with PC.6 The veteran population has singular medical challenges. These patients differ from the general population and are often underrepresented in medical research and published studies.7 There are no studies exploring the treatment-associated toxicities from HDRBT treatment for PC specifically in the veteran population. The objective of this study is to report our findings regarding the veteran-reported and physician-graded toxicities associated with HDRBT as monotherapy in veterans treated through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for PC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of a prospectively maintained, institutional review board-approved database of patients treated with HDRBT for PC. Veterans were seen in consultation at Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois. This is the only VA hospital in Illinois that offers radiation therapy, so it acted as a tertiary center, receiving referrals from other, neighboring VA hospitals. If the veteran was deemed a good BT candidate and elected to proceed with HDRBT, HDR treatment was performed at a partnering academic institution equipped to provide HDRBT (Loyola University Medical Center).

We selected patients with National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDRBT as monotherapy using 13.5 Gy x 2 fractions delivered over 2 implants that were 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were excluded from this study. No patients received supplemental external beam radiation. Men with unfavorable intermediate risk PC were offered ADT and BT in accordance with NCCN guidelines. However, patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk PC who declined ADT or who were deemed poor ADT candidates due to comorbidities were treated with HDR as monotherapy and included in this study.8

HDR Treatment

Our HDRBT implant procedure and treatment planning details have been previously described.9 In brief, patients were implanted with between 17 and 22 catheters based on gland size under transrectal ultrasound guidance. After implantation, computed tomography and, when possible, magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate were obtained and registered for target delineation. The prostate was segmented, and an asymmetric planning target volume of 0 to 5 mm was created and extended to encompass the proximal seminal vesicles. The second fraction was given 1 to 2 weeks after initial treatment, based on patient, physician, and operating room availability.

Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

Veteran-reported genitourinary (GU), gastrointestinal (GI), and sexual health-related quality of life (hrQOL) were assessed using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) instruments.10,11 Baseline veteran-reported hrQOL scores in the GU, GI, and sexual domains were obtained prior to each veteran’s first HDR treatment. Veteran-reported hrQOL scores were assessed at each of the patient’s follow-up appointments. Physician-graded toxicity was assessed Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03 criteria.12 Physician-graded toxicity was assessed at each follow-up visit and reported as the highest grade reported during any follow-up examination.

Follow-up appointments typically occurred at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and subsequently every 6 months after the second HDR treatment. Follow-up appointments were conducted in the radiation oncology department at EHJVAH.

Minimal Clinically Important Differences

To evaluate the veteran-reported hrQOL, we characterized statistically significant differences in IPSS or EPIC-26 scores over time as compared with baseline values as clinically important or not clinically important through the use of reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID) assessments.13-15 For the IPSS, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 3.0 points represented a clinically meaningful change in urinary function.14 For the EPIC-26 scores, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 6 points for urinary incontinence score, ≥ 5 points for urinary obstruction score, ≥ 4 points for bowel score, and ≥ 10 points for sexual score to represent an MCID.15

Statistical Analysis

Changes in veteran-reported hrQOL over time were compared using mixed linear effects models, with the time since the last BT implant serving as the fixed variable. Effects were deemed statistically significant if P < .05. If a statistically significant difference from baseline was found at any time point, additional evaluation was done to see if the numerical difference in the assessment led to an MCID as described above. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

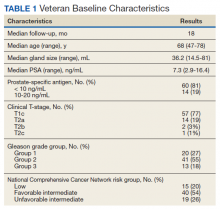

Seventy-four veterans were included in the study. The median follow-up was 18 months (range 1-43). The demographic and oncologic specifics of the treated veterans are outlined in Table 1.

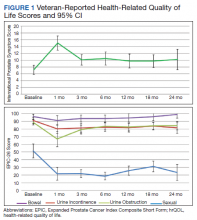

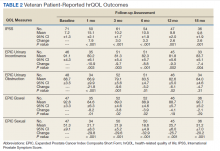

There was a significant increase in IPSS (P < .001) with reciprocal decline in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence (P = .008) and EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores (P = .001) from baseline over time (Table 2 and Figure 1). At the 18-month follow-up assessment, there was no longer a significant difference in the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction score from baseline (88.7 vs 84.0, P = .31). The increases in IPSS at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments met the criteria for MCID. The decrease in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments were found to be an MCID, as were the decrease in EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month assessments.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 bowel scores from baseline over time (P = .03). The decline in the EPIC-26 bowel hrQOL scores at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up assessment were significantly different from the baseline value. However, only the decrease seen at the 1-month assessment met criteria for MCID.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 sexual scores from baseline over time (P < .001). The decline in EPIC-26 sexual score noted at each follow-up compared with baseline was statistically significant. Each of these declines met criteria for an MCID.

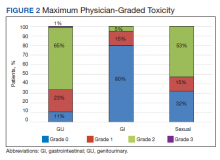

The rate of grade 2 GU, GI, and sexual physician-graded toxicity was 65%, 5%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). There was a single incident of grade 3 GU toxicity, which was a urethral stricture. There were no reported grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, nor were there grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 5 total incidents of acute urinary retention for a 6.8% rate overall.

Discussion

We performed a retrospective study of veterans with low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDR prostate BT as monotherapy. We found that veterans experienced immediate declines in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. However, each trended toward a return to baseline over time, with the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction and the EPIC-26 bowel scores showing no difference from the baseline value within 18 months and 12 months, respectively. The physician-reported toxicities were low, with only 1 incidence of grade 3 GU toxicity, no grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity. This suggests that HDRBT is a well-tolerated and safe, definitive treatment for veterans with localized PC.

In a series similar to ours, Gaudet and colleagues reported on their single institutional results of treating 30 low- or intermediate-risk PC patients with HDRBT as monotherapy.16 Patients included in their study were civilians from the general population, treated in a similar fashion to the veterans treated in our study. Each patient received 27 Gy in 2 fractions given over 2 implants. The authors collected patient-reported hrQOL results using the IPSS and EPIC questionnaires and found that 57% of patients treated experienced moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms at the 1-month assessment after implantation, with a rapid recovery toward baseline over time. In contrast, GI symptoms did not change from baseline, while sexual symptoms worsened after implantation and failed to return to baseline.

Our results mirror this experience, with similar rates of patient-reported hrQOL scores and physician-graded toxicities. Patients reported similar rates of decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. The patient-reported GU and GI hrQOL scores worsened immediately after treatment, with a return toward baseline over time. However, the patient-reported sexual hrQOL dropped after treatment and had a subtle trend toward a return to baseline. Our data show higher rates of maximum physician-graded GU toxicity rates of 23%, 65%, and 1% grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This is likely due in part to our prophylactic use of tamsulosin. Patients who continued tamsulosin after the implant out of preference were technically grade 2 based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria. GI and sexual toxicity were substantially lower with rates of 15% and 5% grade 1 and grade 2 bowel toxicity with no grade 3 events, and 15% and 52% grade 1 and grade 2 sexual toxicity, respectively.

Contreras and colleagues also reported on treating civilian patients with HDRBT as monotherapy for PC.17 They, too, found similar results as in our veteran study, with a rapid decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL scores immediately after treatment. They also found a gradual return to baseline in the GU hrQOL scores. Contrary to our results, they reported a return to baseline in sexual hrQOL scores, while their patients did not report a return to baseline in the GI hrQOL scores.

Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other studies exploring HDR prostate BT toxicity in a veteran-specific population, and our study is novel in addressing this question. One limitation of the study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 18 months. With this limitation, our data were not yet sufficiently mature to perform biochemical control or overall survival analyses. The next step in our study is to calculate these clinical endpoints from our data after longer follow-up.

An additional limitation to our study is the single institutional nature of the design. While veterans from neighboring VA hospitals were included in the study by way of referral and treatment at our center, the only VA hospital in the state to provide radiation therapy, our patient population remains limited. Further multi-institutional and prospective data are needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

HDR prostate BT as monotherapy is feasible with a favorable veteran-reported hrQOL and physician-graded toxicity profile. Veterans should be educated about this treatment modality when considering the optimal treatment for their localized prostate cancer.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883‐e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10‐17.

3. Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79(3):537‐545. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013

4. Harlan LC, Potosky A, Gilliland FD, et al. Factors associated with initial therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1864-1871. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.24.1864

5. Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: an analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):170-180. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.008

6. Crook J, Marbán M, Batchelar D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30(1):49‐60. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.08.003

7. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252.

8. D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):289-295. doi:10.1001/jama.299.3.289

9. Solanki AA, Mysz ML, Patel R, et al. Transitioning from a low-dose-rate to a high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy program: comparing initial dosimetry and improving workflow efficiency through targeted interventions. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2018.10.004

10. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549‐1564. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5

11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899‐905. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.03. Updated June 14, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13128

14. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770-1774. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66780-6

15. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044

16. Gaudet M, Pharand-Charbonneau M, Desrosiers MP, Wright D, Haddad A. Early toxicity and health-related quality of life results of high-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy for low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(3):524-529. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2018.01.009

17. Contreras JA, Wilder RB, Mellon EA, Strom TJ, Fernandez DC, Biagioli MC. Quality of life after high-dose-rate brachytherapy monotherapy for prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(1):40-45. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.07

Nearly 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with cancer within the Veterans Health Administration annually with prostate cancer (PC) being the most frequently diagnosed, accounting for 29% of all cancers diagnosed.1 The treatment of PC depends on the stage and risk group at presentation and patient preference. Men with early stage, localized PC can be managed with prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.2

Within the Veterans Health Administration, more patients are treated with radiation therapy than with radical prostatectomy.3 This is in contrast to the civil health system, where more patients are treated with radical prostatectomy than with radiation therapy.4,5 Radiation therapy for PC can be given externally with external beam radiation therapy or internally with brachytherapy (BT). BT is categorized by the rate at which the radiation dose is delivered and generally grouped as low-dose rate (LDR) or high-dose rate (HDR). LDRBT consists of permanently implanting radioactive seeds, which slowly deliver a radiation dose over an extended period. HDRBT consists of implanting catheters that allow delivery of a radioactive source to be placed temporarily in the prostate and removed after treatment. The utilization of HDRBT has become more common as treatment has evolved to consist of fewer, larger fractions in a shorter time, making it a convenient treatment option for men with PC.6 The veteran population has singular medical challenges. These patients differ from the general population and are often underrepresented in medical research and published studies.7 There are no studies exploring the treatment-associated toxicities from HDRBT treatment for PC specifically in the veteran population. The objective of this study is to report our findings regarding the veteran-reported and physician-graded toxicities associated with HDRBT as monotherapy in veterans treated through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for PC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of a prospectively maintained, institutional review board-approved database of patients treated with HDRBT for PC. Veterans were seen in consultation at Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois. This is the only VA hospital in Illinois that offers radiation therapy, so it acted as a tertiary center, receiving referrals from other, neighboring VA hospitals. If the veteran was deemed a good BT candidate and elected to proceed with HDRBT, HDR treatment was performed at a partnering academic institution equipped to provide HDRBT (Loyola University Medical Center).

We selected patients with National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDRBT as monotherapy using 13.5 Gy x 2 fractions delivered over 2 implants that were 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were excluded from this study. No patients received supplemental external beam radiation. Men with unfavorable intermediate risk PC were offered ADT and BT in accordance with NCCN guidelines. However, patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk PC who declined ADT or who were deemed poor ADT candidates due to comorbidities were treated with HDR as monotherapy and included in this study.8

HDR Treatment

Our HDRBT implant procedure and treatment planning details have been previously described.9 In brief, patients were implanted with between 17 and 22 catheters based on gland size under transrectal ultrasound guidance. After implantation, computed tomography and, when possible, magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate were obtained and registered for target delineation. The prostate was segmented, and an asymmetric planning target volume of 0 to 5 mm was created and extended to encompass the proximal seminal vesicles. The second fraction was given 1 to 2 weeks after initial treatment, based on patient, physician, and operating room availability.

Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

Veteran-reported genitourinary (GU), gastrointestinal (GI), and sexual health-related quality of life (hrQOL) were assessed using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) instruments.10,11 Baseline veteran-reported hrQOL scores in the GU, GI, and sexual domains were obtained prior to each veteran’s first HDR treatment. Veteran-reported hrQOL scores were assessed at each of the patient’s follow-up appointments. Physician-graded toxicity was assessed Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03 criteria.12 Physician-graded toxicity was assessed at each follow-up visit and reported as the highest grade reported during any follow-up examination.

Follow-up appointments typically occurred at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and subsequently every 6 months after the second HDR treatment. Follow-up appointments were conducted in the radiation oncology department at EHJVAH.

Minimal Clinically Important Differences

To evaluate the veteran-reported hrQOL, we characterized statistically significant differences in IPSS or EPIC-26 scores over time as compared with baseline values as clinically important or not clinically important through the use of reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID) assessments.13-15 For the IPSS, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 3.0 points represented a clinically meaningful change in urinary function.14 For the EPIC-26 scores, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 6 points for urinary incontinence score, ≥ 5 points for urinary obstruction score, ≥ 4 points for bowel score, and ≥ 10 points for sexual score to represent an MCID.15

Statistical Analysis

Changes in veteran-reported hrQOL over time were compared using mixed linear effects models, with the time since the last BT implant serving as the fixed variable. Effects were deemed statistically significant if P < .05. If a statistically significant difference from baseline was found at any time point, additional evaluation was done to see if the numerical difference in the assessment led to an MCID as described above. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

Seventy-four veterans were included in the study. The median follow-up was 18 months (range 1-43). The demographic and oncologic specifics of the treated veterans are outlined in Table 1.

There was a significant increase in IPSS (P < .001) with reciprocal decline in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence (P = .008) and EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores (P = .001) from baseline over time (Table 2 and Figure 1). At the 18-month follow-up assessment, there was no longer a significant difference in the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction score from baseline (88.7 vs 84.0, P = .31). The increases in IPSS at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments met the criteria for MCID. The decrease in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments were found to be an MCID, as were the decrease in EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month assessments.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 bowel scores from baseline over time (P = .03). The decline in the EPIC-26 bowel hrQOL scores at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up assessment were significantly different from the baseline value. However, only the decrease seen at the 1-month assessment met criteria for MCID.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 sexual scores from baseline over time (P < .001). The decline in EPIC-26 sexual score noted at each follow-up compared with baseline was statistically significant. Each of these declines met criteria for an MCID.

The rate of grade 2 GU, GI, and sexual physician-graded toxicity was 65%, 5%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). There was a single incident of grade 3 GU toxicity, which was a urethral stricture. There were no reported grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, nor were there grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 5 total incidents of acute urinary retention for a 6.8% rate overall.

Discussion

We performed a retrospective study of veterans with low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDR prostate BT as monotherapy. We found that veterans experienced immediate declines in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. However, each trended toward a return to baseline over time, with the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction and the EPIC-26 bowel scores showing no difference from the baseline value within 18 months and 12 months, respectively. The physician-reported toxicities were low, with only 1 incidence of grade 3 GU toxicity, no grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity. This suggests that HDRBT is a well-tolerated and safe, definitive treatment for veterans with localized PC.

In a series similar to ours, Gaudet and colleagues reported on their single institutional results of treating 30 low- or intermediate-risk PC patients with HDRBT as monotherapy.16 Patients included in their study were civilians from the general population, treated in a similar fashion to the veterans treated in our study. Each patient received 27 Gy in 2 fractions given over 2 implants. The authors collected patient-reported hrQOL results using the IPSS and EPIC questionnaires and found that 57% of patients treated experienced moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms at the 1-month assessment after implantation, with a rapid recovery toward baseline over time. In contrast, GI symptoms did not change from baseline, while sexual symptoms worsened after implantation and failed to return to baseline.

Our results mirror this experience, with similar rates of patient-reported hrQOL scores and physician-graded toxicities. Patients reported similar rates of decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. The patient-reported GU and GI hrQOL scores worsened immediately after treatment, with a return toward baseline over time. However, the patient-reported sexual hrQOL dropped after treatment and had a subtle trend toward a return to baseline. Our data show higher rates of maximum physician-graded GU toxicity rates of 23%, 65%, and 1% grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This is likely due in part to our prophylactic use of tamsulosin. Patients who continued tamsulosin after the implant out of preference were technically grade 2 based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria. GI and sexual toxicity were substantially lower with rates of 15% and 5% grade 1 and grade 2 bowel toxicity with no grade 3 events, and 15% and 52% grade 1 and grade 2 sexual toxicity, respectively.

Contreras and colleagues also reported on treating civilian patients with HDRBT as monotherapy for PC.17 They, too, found similar results as in our veteran study, with a rapid decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL scores immediately after treatment. They also found a gradual return to baseline in the GU hrQOL scores. Contrary to our results, they reported a return to baseline in sexual hrQOL scores, while their patients did not report a return to baseline in the GI hrQOL scores.

Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other studies exploring HDR prostate BT toxicity in a veteran-specific population, and our study is novel in addressing this question. One limitation of the study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 18 months. With this limitation, our data were not yet sufficiently mature to perform biochemical control or overall survival analyses. The next step in our study is to calculate these clinical endpoints from our data after longer follow-up.

An additional limitation to our study is the single institutional nature of the design. While veterans from neighboring VA hospitals were included in the study by way of referral and treatment at our center, the only VA hospital in the state to provide radiation therapy, our patient population remains limited. Further multi-institutional and prospective data are needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

HDR prostate BT as monotherapy is feasible with a favorable veteran-reported hrQOL and physician-graded toxicity profile. Veterans should be educated about this treatment modality when considering the optimal treatment for their localized prostate cancer.

Nearly 50,000 veterans are diagnosed with cancer within the Veterans Health Administration annually with prostate cancer (PC) being the most frequently diagnosed, accounting for 29% of all cancers diagnosed.1 The treatment of PC depends on the stage and risk group at presentation and patient preference. Men with early stage, localized PC can be managed with prostatectomy, radiation therapy, or active surveillance.2

Within the Veterans Health Administration, more patients are treated with radiation therapy than with radical prostatectomy.3 This is in contrast to the civil health system, where more patients are treated with radical prostatectomy than with radiation therapy.4,5 Radiation therapy for PC can be given externally with external beam radiation therapy or internally with brachytherapy (BT). BT is categorized by the rate at which the radiation dose is delivered and generally grouped as low-dose rate (LDR) or high-dose rate (HDR). LDRBT consists of permanently implanting radioactive seeds, which slowly deliver a radiation dose over an extended period. HDRBT consists of implanting catheters that allow delivery of a radioactive source to be placed temporarily in the prostate and removed after treatment. The utilization of HDRBT has become more common as treatment has evolved to consist of fewer, larger fractions in a shorter time, making it a convenient treatment option for men with PC.6 The veteran population has singular medical challenges. These patients differ from the general population and are often underrepresented in medical research and published studies.7 There are no studies exploring the treatment-associated toxicities from HDRBT treatment for PC specifically in the veteran population. The objective of this study is to report our findings regarding the veteran-reported and physician-graded toxicities associated with HDRBT as monotherapy in veterans treated through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for PC.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of a prospectively maintained, institutional review board-approved database of patients treated with HDRBT for PC. Veterans were seen in consultation at Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital (EHJVAH) in Hines, Illinois. This is the only VA hospital in Illinois that offers radiation therapy, so it acted as a tertiary center, receiving referrals from other, neighboring VA hospitals. If the veteran was deemed a good BT candidate and elected to proceed with HDRBT, HDR treatment was performed at a partnering academic institution equipped to provide HDRBT (Loyola University Medical Center).

We selected patients with National Cancer Center Network (NCCN) low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDRBT as monotherapy using 13.5 Gy x 2 fractions delivered over 2 implants that were 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) were excluded from this study. No patients received supplemental external beam radiation. Men with unfavorable intermediate risk PC were offered ADT and BT in accordance with NCCN guidelines. However, patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk PC who declined ADT or who were deemed poor ADT candidates due to comorbidities were treated with HDR as monotherapy and included in this study.8

HDR Treatment

Our HDRBT implant procedure and treatment planning details have been previously described.9 In brief, patients were implanted with between 17 and 22 catheters based on gland size under transrectal ultrasound guidance. After implantation, computed tomography and, when possible, magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate were obtained and registered for target delineation. The prostate was segmented, and an asymmetric planning target volume of 0 to 5 mm was created and extended to encompass the proximal seminal vesicles. The second fraction was given 1 to 2 weeks after initial treatment, based on patient, physician, and operating room availability.

Health-Related Quality of Life Assessment

Veteran-reported genitourinary (GU), gastrointestinal (GI), and sexual health-related quality of life (hrQOL) were assessed using the validated International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26) instruments.10,11 Baseline veteran-reported hrQOL scores in the GU, GI, and sexual domains were obtained prior to each veteran’s first HDR treatment. Veteran-reported hrQOL scores were assessed at each of the patient’s follow-up appointments. Physician-graded toxicity was assessed Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03 criteria.12 Physician-graded toxicity was assessed at each follow-up visit and reported as the highest grade reported during any follow-up examination.

Follow-up appointments typically occurred at 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and subsequently every 6 months after the second HDR treatment. Follow-up appointments were conducted in the radiation oncology department at EHJVAH.

Minimal Clinically Important Differences

To evaluate the veteran-reported hrQOL, we characterized statistically significant differences in IPSS or EPIC-26 scores over time as compared with baseline values as clinically important or not clinically important through the use of reported minimal clinically important difference (MCID) assessments.13-15 For the IPSS, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 3.0 points represented a clinically meaningful change in urinary function.14 For the EPIC-26 scores, we used reported data that showed a change of ≥ 6 points for urinary incontinence score, ≥ 5 points for urinary obstruction score, ≥ 4 points for bowel score, and ≥ 10 points for sexual score to represent an MCID.15

Statistical Analysis

Changes in veteran-reported hrQOL over time were compared using mixed linear effects models, with the time since the last BT implant serving as the fixed variable. Effects were deemed statistically significant if P < .05. If a statistically significant difference from baseline was found at any time point, additional evaluation was done to see if the numerical difference in the assessment led to an MCID as described above. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

Seventy-four veterans were included in the study. The median follow-up was 18 months (range 1-43). The demographic and oncologic specifics of the treated veterans are outlined in Table 1.

There was a significant increase in IPSS (P < .001) with reciprocal decline in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence (P = .008) and EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores (P = .001) from baseline over time (Table 2 and Figure 1). At the 18-month follow-up assessment, there was no longer a significant difference in the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction score from baseline (88.7 vs 84.0, P = .31). The increases in IPSS at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month assessments met the criteria for MCID. The decrease in EPIC-26 urinary incontinence scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month assessments were found to be an MCID, as were the decrease in EPIC-26 urinary obstruction scores at the 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month assessments.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 bowel scores from baseline over time (P = .03). The decline in the EPIC-26 bowel hrQOL scores at the 1-, 3-, and 6-month follow-up assessment were significantly different from the baseline value. However, only the decrease seen at the 1-month assessment met criteria for MCID.

There was a significant decline in EPIC-26 sexual scores from baseline over time (P < .001). The decline in EPIC-26 sexual score noted at each follow-up compared with baseline was statistically significant. Each of these declines met criteria for an MCID.

The rate of grade 2 GU, GI, and sexual physician-graded toxicity was 65%, 5%, and 53%, respectively (Figure 2). There was a single incident of grade 3 GU toxicity, which was a urethral stricture. There were no reported grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, nor were there grade 4 or 5 toxicities. There were 5 total incidents of acute urinary retention for a 6.8% rate overall.

Discussion

We performed a retrospective study of veterans with low- or intermediate-risk PC undergoing definitive HDR prostate BT as monotherapy. We found that veterans experienced immediate declines in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. However, each trended toward a return to baseline over time, with the EPIC-26 urinary obstruction and the EPIC-26 bowel scores showing no difference from the baseline value within 18 months and 12 months, respectively. The physician-reported toxicities were low, with only 1 incidence of grade 3 GU toxicity, no grade 3 GI or sexual toxicities, and no grade 4 or 5 toxicity. This suggests that HDRBT is a well-tolerated and safe, definitive treatment for veterans with localized PC.

In a series similar to ours, Gaudet and colleagues reported on their single institutional results of treating 30 low- or intermediate-risk PC patients with HDRBT as monotherapy.16 Patients included in their study were civilians from the general population, treated in a similar fashion to the veterans treated in our study. Each patient received 27 Gy in 2 fractions given over 2 implants. The authors collected patient-reported hrQOL results using the IPSS and EPIC questionnaires and found that 57% of patients treated experienced moderate-to-severe urinary symptoms at the 1-month assessment after implantation, with a rapid recovery toward baseline over time. In contrast, GI symptoms did not change from baseline, while sexual symptoms worsened after implantation and failed to return to baseline.

Our results mirror this experience, with similar rates of patient-reported hrQOL scores and physician-graded toxicities. Patients reported similar rates of decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL after treatment. The patient-reported GU and GI hrQOL scores worsened immediately after treatment, with a return toward baseline over time. However, the patient-reported sexual hrQOL dropped after treatment and had a subtle trend toward a return to baseline. Our data show higher rates of maximum physician-graded GU toxicity rates of 23%, 65%, and 1% grade 1, 2, and 3, respectively. This is likely due in part to our prophylactic use of tamsulosin. Patients who continued tamsulosin after the implant out of preference were technically grade 2 based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria. GI and sexual toxicity were substantially lower with rates of 15% and 5% grade 1 and grade 2 bowel toxicity with no grade 3 events, and 15% and 52% grade 1 and grade 2 sexual toxicity, respectively.

Contreras and colleagues also reported on treating civilian patients with HDRBT as monotherapy for PC.17 They, too, found similar results as in our veteran study, with a rapid decline in GU, GI, and sexual hrQOL scores immediately after treatment. They also found a gradual return to baseline in the GU hrQOL scores. Contrary to our results, they reported a return to baseline in sexual hrQOL scores, while their patients did not report a return to baseline in the GI hrQOL scores.

Limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other studies exploring HDR prostate BT toxicity in a veteran-specific population, and our study is novel in addressing this question. One limitation of the study is the relatively short median follow-up time of 18 months. With this limitation, our data were not yet sufficiently mature to perform biochemical control or overall survival analyses. The next step in our study is to calculate these clinical endpoints from our data after longer follow-up.

An additional limitation to our study is the single institutional nature of the design. While veterans from neighboring VA hospitals were included in the study by way of referral and treatment at our center, the only VA hospital in the state to provide radiation therapy, our patient population remains limited. Further multi-institutional and prospective data are needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

HDR prostate BT as monotherapy is feasible with a favorable veteran-reported hrQOL and physician-graded toxicity profile. Veterans should be educated about this treatment modality when considering the optimal treatment for their localized prostate cancer.

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883‐e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10‐17.

3. Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79(3):537‐545. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013

4. Harlan LC, Potosky A, Gilliland FD, et al. Factors associated with initial therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1864-1871. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.24.1864

5. Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: an analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):170-180. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.008

6. Crook J, Marbán M, Batchelar D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30(1):49‐60. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.08.003

7. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252.

8. D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):289-295. doi:10.1001/jama.299.3.289

9. Solanki AA, Mysz ML, Patel R, et al. Transitioning from a low-dose-rate to a high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy program: comparing initial dosimetry and improving workflow efficiency through targeted interventions. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2018.10.004

10. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549‐1564. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5

11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899‐905. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.03. Updated June 14, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13128

14. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770-1774. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66780-6

15. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044

16. Gaudet M, Pharand-Charbonneau M, Desrosiers MP, Wright D, Haddad A. Early toxicity and health-related quality of life results of high-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy for low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(3):524-529. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2018.01.009

17. Contreras JA, Wilder RB, Mellon EA, Strom TJ, Fernandez DC, Biagioli MC. Quality of life after high-dose-rate brachytherapy monotherapy for prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(1):40-45. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.07

1. Zullig LL, Sims KJ, McNeil R, et al. Cancer incidence among patients of the U.S. Veterans Affairs health care system: 2010 update. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1883‐e1891. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00371

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10‐17.

3. Nambudiri VE, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Understanding variation in primary prostate cancer treatment within the Veterans Health Administration. Urology. 2012;79(3):537‐545. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.013

4. Harlan LC, Potosky A, Gilliland FD, et al. Factors associated with initial therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(24):1864-1871. doi:10.1093/jnci/93.24.1864

5. Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: an analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2018;3(2):170-180. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2017.12.008

6. Crook J, Marbán M, Batchelar D. HDR prostate brachytherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2020;30(1):49‐60. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2019.08.003

7. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252.

8. D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(3):289-295. doi:10.1001/jama.299.3.289

9. Solanki AA, Mysz ML, Patel R, et al. Transitioning from a low-dose-rate to a high-dose-rate prostate brachytherapy program: comparing initial dosimetry and improving workflow efficiency through targeted interventions. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4(1):103-111. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2018.10.004

10. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549‐1564. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5

11. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, Sandler HM, Sanda MG. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899‐905. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.03. Updated June 14, 2010. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf

13. McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1342-1343. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13128

14. Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association Symptom Index and the Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770-1774. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66780-6

15. Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important difference for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–105. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044

16. Gaudet M, Pharand-Charbonneau M, Desrosiers MP, Wright D, Haddad A. Early toxicity and health-related quality of life results of high-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy for low and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy. 2018;17(3):524-529. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2018.01.009

17. Contreras JA, Wilder RB, Mellon EA, Strom TJ, Fernandez DC, Biagioli MC. Quality of life after high-dose-rate brachytherapy monotherapy for prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(1):40-45. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2015.01.07

Bone Health in Patients With Prostate Cancer: An Evidence-Based Algorithm

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most commonly and newly diagnosed nonskin cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in men in the United States. About 191,930 cases and about 33,330 deaths from PC were expected for the year 2020.1 About 1 in 41 men will die of PC. Most men diagnosed with PC are aged > 65 years and do not die of their disease. The 5-year survival rate of localized and regional disease is nearly 100%, and disease with distant metastases is 31%. As a result, more than 3.1 million men in the United States who have been diagnosed with PC are still alive today.1 Among veterans, there is a substantial population living with PC. Skolarus and Hawley reported in 2014 that an estimated 200,000 veterans with PC were survivors and 12,000 were newly diagnosed.2

In PC, skeletal strength can be affected by several factors, such as aging, malnutrition, androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), and bone metastasis.3,4 In fact, most men can live the rest of their life with PC by using strategies to monitor and treat it, once it shows either radiographic or chemical signs of progression.5 ADT is the standard of care to treat hormone-sensitive PC, which is associated with significant skeletal-related adverse effects (AEs).6,7

Men undergoing ADT are 4 times more likely to develop substantial bone deficiency, Shahinian and colleagues found that in men surviving 5 years after PC diagnosis, 19.4% of those who received ADT had a fracture compared with 12% in men who did not (P < .001). The authors established a significant relation between the number of doses of gonadotropin-releasing hormone given in the first 12 months and the risk of fracture.8 Of those who progressed to metastatic disease, the first metastatic nonnodal site is most commonly to the bone.9 Advanced PC is characterized by increased bone turnover, which further raises concerns for bone health and patient performance.10

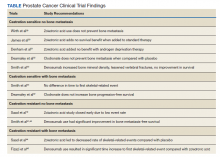

Skeletal-related events (SREs) include pathologic fracture, spinal cord compression, palliative radiation, or surgery to bone, and change in antineoplastic therapy secondary to bone pain. The concept of bone health refers to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of idiopathic, pathogenic, and treatment-related bone loss and delay or prevention of SREs.6,11 Guidelines and expert groups have recommended screening for osteoporosis at the start of ADT with bone mineral density testing, ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, modifying lifestyle behaviors (smoking cessation, alcohol moderation, and regular exercise), and prescribing bisphosphonates or receptor-activated nuclear factor κ-B ligand inhibitor, denosumab, for men with osteoporosis or who are at general high-fracture risk.12,13 The overuse of these medications results in undue cost to patients as well as AEs, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), hypocalcemia, and bone/joint pains.14-17 There are evidence-based guidelines for appropriate use of bisphosphonates and denosumab for delay and prevention of SREs in the setting of advanced PC.18 These doses also typically differ in frequency to those of osteoporosis.19 We summarize the evidence and guidance for health care providers who care for patients with PC at various stages and complications from both disease-related and treatment-related comorbidities.

Bone-Strengthening Agents

Overall, there is evidence to support the use of bone-strengthening agents in patients with osteopenia/osteoporosis in the prevention of SREs with significant risk factors for progressive bone demineralization, such as lifestyle factors and, in particular, treatments such as ADT. Bone-remodeling agents for treatment of bony metastasis have been shown to provide therapeutic advantage only in limited instances in the castration-resistant PC (CRPC) setting. Hence, in patients with hormone-sensitive PC due to medication-related AEs, treatment with bone-strengthening agents is indicated only if the patient has a significant preexisting risk for fracture from osteopenia/osteoporosis (Table). The Figure depicts an algorithm for the management of bone health in men with PC who are being treated with ADT.

Denosumab and bisphosphonates have an established role in preventing SREs in metastatic CRPC.20 The choice of denosumab or a bisphosphonate typically varies based on the indication, possible AEs, and cost of therapy. There are multiple studies involving initiation of these agents at various stages of disease to improve both time to progression as well as management of SREs. There is a lack of evidence that bisphosphonates prevent metastatic-bone lesions in castration-sensitive PC; therefore, prophylactic use of this agent is not recommended in patients unless they have significant bone demineralization.21,22

Medication-induced ONJ is a severe AE of both denosumab and bisphosphonate therapies. Data from recent trials showed that higher dosing and prolonged duration of denosumab and bisphosphonate therapies further increased risk of ONJ by 1.8% and 1.3%, respectively.15 Careful history taking and discussions with the patient and if possible their dentist on how to reduce risk are recommended. It is good practice for the patient to complete a dental evaluation prior to starting IV bisphosphonates or denosumab. Dental evaluations should be performed routinely at 3- to 12-month intervals throughout therapy based on individualized risk assessment.23 The benefits of using bisphosphonates to prevent fractures associated with osteoporosis outweigh the risk of ONJ in high-risk populations, but not in all patients with PC. A case-by-case basis and evaluation of risk factors should be performed prior to administering bone-modifying therapy. The long-term safety of IV bisphosphonates has not been adequately studied in controlled trials, and concerns regarding long-term complications, including renal toxicity, ONJ, and atypical femoral fractures, remain with prolonged therapy.24,25

The CALGB 70604 (Alliance) trial compared 3-month dosing to monthly treatment with zoledronic acid (ZA), showing no inferiority to lower frequency dosing.26 A Cochrane review of clinical trials found that in patients with advanced PC, bisphosphonates were found to provide roughly 58 fewer SREs per 1000 on average.27 A phase 3 study showed a modest benefit to denosumab vs ZA in the CRPC group regarding incidence of SREs. The rates of SREs were 289 of 951 patients in the bisphosphonate group, and 241 of 950 patients in the denosumab group (30.4% vs 25.3%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P = .005).28 In 2020, the American Society of Clinical Oncology endorsed the Cancer Care Ontario guidelines for prostate bone health care.18 Adequate supplementation is necessary in all patients treated with a bisphosphonate or denosumab to prevent treatment-related hypocalcemia. Typically, daily supplementation with a minimum of calcium 500 mg and vitamin D 400 IU is recommended.16

Bone Health in Patients

Nonmetastatic Hormone-Sensitive PC

ADT forms the backbone of treatment for patients with local and advanced metastatic castration-sensitive PC along with surgical and focal radiotherapy options. Cancer treatment-induced bone loss is known to occur with prolonged use of ADT. The ZEUS trial found no prevention of bone metastasis in patients with high-risk localized PC with the use of ZA in the absence of bone metastasis. A Kaplan-Meier estimated proportion of bone metastases after a median follow-up of 4.8 years was found to be not statistically significant: 14.7% in the ZA group vs 13.2% in the control/placebo group.29 The STAMPEDE trial showed no significant overall survival (OS) benefit with the addition of ZA to ADT vs ADT alone (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.79-1.11; P = .45), 5-year survival with ADT alone was 55% compared to ADT plus ZA with 57% 5-year survival.30 The RADAR trial showed that at 5 years in high Gleason score patients, use of ZA in the absence of bone metastasis was beneficial, but not in low- or intermediate-risk patients. However, at 10-year analysis there was no significant difference in any of the high-stratified groups with or without ZA.31

The PR04 trial showed no effect on OS with clodronate compared with placebo in nonmetastatic castration-sensitive PC, with a HR of 1.12 (95% CI, 0.89-1.42; P = .94). The estimated 5-year survival was 80% with placebo and 78% with clodronate; 10-year survival rates were 51% with placebo and 48% with clodronate.32 Data from the HALT trial showed an increased bone mineral density and reduced risk of new vertebral fractures vs placebo (1.5% vs 3.9%, respectively) in the absence of metastatic bone lesions and a reduction in new vertebral fractures in patients with nonmetastatic PC.33 Most of these studies showed no benefit with the addition of ZA to nonmetastatic PC; although, the HALT trial provides evidence to support use of denosumab in patients with nonmetastatic PC for preventing vertebral fragility fractures in men receiving ADT.

Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive PC

ZA is often used to treat men with metastatic castration-sensitive PC despite limited efficacy and safety data. The CALGB 90202 (Alliance) trial authors found that the early use of ZA was not associated with increased time to first SRE. The median time to first SRE was 31.9 months in the ZA group (95% CI, 24.2-40.3) and 29.8 months in the placebo group (stratified HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0-1.17; 1-sided stratified log-rank P = .39).34 OS was similar between the groups (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.70-1.12; P = .29) as were reported AEs.34 Results from these studies suggest limited benefit in treating patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive PC with bisphosphonates without other medical indications for use. Additional studies suggest similar results for treatment with denosumab to that of bisphosphonate therapies.35

Nonmetastatic CRPC

Reasonable interest among treating clinicians exists to be able to delay or prevent the development of metastatic bone disease in patients who are showing biochemical signs of castration resistance but have not yet developed distant metastatic disease. Time to progression on ADT to castration resistance usually occurs 2 to 3 years following initiation of treatment. This typically occurs in patients with rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA). As per the Prostate Cancer Working Group 3, in the absence of radiologic progression, CRPC is defined by a 25% increase from the nadir (considering a starting value of ≥ 1 ng/mL), with a minimum rise of 2 ng/mL in the setting of castrate serum testosterone < 50 ng/dL despite good adherence to an ADT regimen, with proven serologic castration either by undetectable or a near undetectable nadir of serum testosterone concentration. Therapeutic implications include prevention of SREs as well as time to metastatic bone lesions. The Zometa 704 trial examined the use of ZA to reduce time to first metastatic bone lesion in the setting of patients with nonmetastatic CRPC.36 The trial was discontinued prematurely due to low patient accrual, but initial analysis provided information on the natural history of a rising PSA in this patient population. At 2 years, one-third of patients had developed bone metastases. Median bone metastasis-free survival was 30 months. Median time to first bone metastasis and OS were not reached. Baseline PSA and PSA velocity independently predicted a shorter time to first bone metastasis, metastasis-free survival, and OS.36

Denosumab was also studied in the setting of nonmetastatic CRPC in the Denosumab 147 trial. The study enrolled 1432 patients and found a significantly increased bone metastasis-free survival by a median of 4.2 months over placebo (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.98; P = .03). Denosumab significantly delayed time to first bone metastasis (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-0.98; P = .03). OS was similar between groups (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.85-1.20; P = .91). Rates of AEs and serious AEs were similar between groups, except for ONJ and hypocalcemia. The rates of ONJ for denosumab were 1%, 3%, 4% in years 1,2, 3, respectively; overall, < 5% (n = 33). Hypocalcemia occurred in < 2% (n = 12) in denosumab-treated patients. The authors concluded that in men with CRPC, denosumab significantly prolonged bone metastasis–free survival and delayed time-to-bone metastasis.37 These 2 studies suggest a role of receptor-activated nuclear factor κ-B ligand inhibitor denosumab in patients with nonmetastatic CRPC in the appropriate setting. There were delays in bony metastatic disease, but no difference in OS. Rare denosumab treatment–related specific AEs were noted. Hence, denosumab is not recommended for use in this setting.

Metastatic CRPC

Castration resistance typically occurs 2 to 3 years following initiation of ADT and the most common extranodal site of disease is within the bone in metastatic PC. Disease progression within bones after ADT can be challenging given both the nature of progressive cancer with osteoblastic metastatic lesions and the prolonged effects of ADT on unaffected bone. The Zometa 039 study compared ZA with placebo and found a significant difference in SREs (38% and 49%, respectively; P .03). No survival benefit was observed with the addition of ZA. Use of other bisphosphonates pamidronate and clodronate did not have a similar degree of benefit.38,39

A phase 3 study of 1904 patients found that denosumab was superior to ZA in delaying the time to first on-study SRE (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.71-0.95) and reducing rates of multiple SREs (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.71-0.94).40 This was later confirmed with an additional study that demonstrated treatment with denosumab significantly reduced the risk of developing a first symptomatic SRE, defined as a pathologic fracture, spinal cord compression, necessity for radiation, or surgery (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P = .005) and first and subsequent symptomatic SREs (rate ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65-0.92; P = .004) compared with ZA.28 These findings suggest a continued role of denosumab in the treatment of advanced metastatic CRPC from both control of bone disease as well as quality of life and palliation of cancer-related symptoms.

Radium-223 dichloride (radium-223) is an α-emitting radionuclide for treatment of metastatic CRPC with bone metastasis, but otherwise no additional metastatic sites. Radium-223 is a calcium-mimetic that preferentially accumulates into areas of high-bone turnover, such as where bone metastases tend to occur. Radium-223 induces apoptosis of tumor cells through double-stranded DNA breaks. Studies have shown radium-223 to prolong OS and time-to-first symptomatic SRE.41 The ERA-223 trial showed that when radium-223 was combined with abiraterone acetate, there was an increase in fragility fracture risk compared with placebo combined with abiraterone. Data from the study revealed that the median symptomatic SRE-free survival was 22.3 months (95% CI, 20.4-24.8) in the radium-223 group and 26.0 months (21.8-28.3) in the placebo group. Concurrent treatment with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone or prednisolone and radium-223 was associated with increased fracture risk. Osteoporotic fractures were the most common type of fracture in the radium-223 group and of all fracture types, differed the most between the study groups.42

Conclusions

Convincing evidence supports the ongoing use of bisphosphonates and denosumab in patients with osteoporosis, significant osteopenia with risk factors, and in patients with CRPC with bone metastasis. Bone metastases can cause considerable morbidity and mortality among men with advanced PC. Pain, fracture, and neurologic injury can occur with metastatic bone lesions as well as with ADT-related bone loss. Prevention of SREs in patients with PC is a reasonable goal in PC survivors while being mindful of managing the risks of these therapies.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30. doi:10.3322/caac.21590

2. Skolarus TA, Hawley ST. Prostate cancer survivorship care in the Veterans Health Administration. Fed Pract. 2014;31(8):10-17.

3. Gartrell BA, Coleman R, Efstathiou E, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer and the bone: significance and therapeutic options. Eur Urol. 2015;68(5):850-858. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.039

4. Bolla M, de Reijke TM, Van Tienhoven G, et al. Duration of androgen suppression in the treatment of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(24):2516-2527. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810095

5. Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Reconsidering Prostate cancer mortality—The future of PSA screening. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1557-1563. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1914228

6. Coleman R, Body JJ, Aapro M, Hadji P, Herrstedt J; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2014;25 (suppl 3):iii124-137. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu103

7. Saylor PJ, Smith MR. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy: defining the problem and promoting health among men with prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(2):211-223. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2010.0014

8. Shahinian VB, Kuo Y-F, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Risk of fracture after androgen deprivation for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(2):154-164. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041943

9. Sartor O, de Bono JS. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):645-657. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1701695

10. Saad F, Eastham JA, Smith MR. Biochemical markers of bone turnover and clinical outcomes in men with prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2012;30(4):369-378. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.08.007

11. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2

12. Alibhai SMH, Zukotynski K, Walker-Dilks C, et al; Cancer Care Ontario Genitourinary Cancer Disease Site Group. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for prostate cancer: a programme in evidence-based care - Cancer Care Ontario Clinical Practice Guideline. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2017;29(6):348-355. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2017.01.007

13. LEE CE. A comprehensive bone-health management approach with men with prostate cancer recieving androgen deprivation therapy. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(4):e163-172. doi:10.3747/co.v18i4.746

14. Kennel KA, Drake MT. Adverse effects of bisphosphonates: Implications for osteoporosis management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(7):632-638. doi:10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60752-0

15. Saad F, Brown JE, Van Poznak C, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of osteonecrosis of the jaw: integrated analysis from three blinded active-controlled phase III trials in cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(5):1341-1347. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr435

16. Body J-J, Bone HG, de Boer RH, et al. Hypocalcaemia in patients with metastatic bone disease treated with denosumab. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(13):1812-1821. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.016

17. Wysowski DK, Chang JT. Alendronate and risedronate: reports of severe bone, joint, and muscle pain. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(3):346-347. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.3.346-b

18. Saylor PJ, Rumble RB, Tagawa S, et al. Bone health and bone-targeted therapies for prostate cancer: ASCO endorsement of a cancer care Ontario guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15):1736-1743. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.03148

19. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al; Zoledronic Acid Prostate Cancer Study Group. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(11):879-882. doi:10.1093/jnci/djh141

20. Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al; Zoledronic Acid Prostate Cancer Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic zcid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(19):1458-1468. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.19.1458

21. Aapro M, Saad F. Bone-modifying agents in the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced genitourinary malignancies: a focus on zoledronic acid. Ther Adv Urol. 2012;4(2):85-101. doi:10.1177/1756287212441234

22. Cianferotti L, Bertoldo F, Carini M, et al. The prevention of fragility fractures in patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer: a position statement by the international osteoporosis foundation. Oncotarget. 2017;8(43):75646-75663. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.17980

23. Ruggiero S, Gralow J, Marx RE, et al. Practical guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2(1):7-14. doi:10.1200/JOP.2006.2.1.7

24. Corraini P, Heide-Jørgensen U, Schøodt M, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and survival of patients with cancer: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Cancer Med. 2017;6(10):2271-2277. doi:10.1002/cam4.1173

25. Watts NB, Diab DL. Long-term use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1555-1565. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-1947

26. Himelstein AL, Foster JC, Khatcheressian JL, et al. Effect of longer interval vs standard dosing of zoledronic acid on skeletal events in patients with bone metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):48-58. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19425

27. Macherey S, Monsef I, Jahn F, et al. Bisphosphonates for advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12(12):CD006250. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006250.pub2

28. Smith MR, Coleman RE, Klotz L, et al. Denosumab for the prevention of skeletal complications in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: comparison of skeletal-related events and symptomatic skeletal events. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):368-374. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu519

29. Wirth M, Tammela T, Cicalese V, et al. Prevention of bone metastases in patients with high-risk nonmetastatic prostate cancer treated with zoledronic acid: efficacy and safety results of the Zometa European Study (ZEUS). Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):482-491. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.014

30. James ND, Sydes MR, Clarke NW, et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10024):1163-1177. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01037-5

31. Denham JW, Joseph D, Lamb DS, et al. Short-term androgen suppression and radiotherapy versus intermediate-term androgen suppression and radiotherapy, with or without zoledronic acid, in men with locally advanced prostate cancer (TROG 03.04 RADAR): 10-year results from a randomised, phase 3, factorial trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):267-281. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30757-5

32. Dearnaley DP, Mason MD, Parmar MK, Sanders K, Sydes MR. Adjuvant therapy with oral sodium clodronate in locally advanced and metastatic prostate cancer: long-term overall survival results from the MRC PR04 and PR05 randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):872-876. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70201-3

33. Smith MR, Egerdie B, Toriz NH, et al; Denosumab HALT Prostate Cancer Study Group. Denosumab in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):745-755. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0809003