User login

Study takes fine-grained look at MACE risk with glucocorticoids in RA

SAN DIEGO – Even when taken at low doses and over short periods, glucocorticoids (GCs) were linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) over the long term in a Veterans Affairs population of older, mostly male patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a new retrospective cohort study has found.

The analysis of nearly 19,000 patients, presented by rheumatologist Beth Wallace, MD, MSc, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, showed that the level of risk for MACE rose with the dose, duration, and recency of GC use, in which risk increased significantly at prednisone-equivalent doses as low as 5 mg/day, durations as short as 30 days, and with last use as long as 1 year before MACE.

“Up to half of RA patients in the United States use long-term glucocorticoids despite previous work suggesting they increase MACE in a dose-dependent way,” said Dr. Wallace, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a rheumatologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare Center. “Our group previously presented work suggesting that less than 14 days of glucocorticoid use in a 6-month period is associated with a two-thirds increase in odds of MACE over the following 6 months, with 90 days of use associated with more than twofold increase.”

In recent years, researchers such as Dr. Wallace have focused attention on the risks of GCs in RA. The American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology emphasize avoiding long-term use of GCs in RA and keeping doses as small and over the shortest amount of time as possible.

When Dr. Wallace and colleagues looked at the clinical pattern of GC use for patients with RA during the past 2 years, those who took 5 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10 mg daily doses for 30 days and had stopped at least a year before had risk for MACE that rose significantly by 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, compared with those who didn’t take GCs in the past 2 years.

While those increases were small, risk for MACE rose even more for those who took the same daily doses for 90 days, increasing 10%, 15%, and 21%, respectively. Researchers linked current ongoing use of GCs for the past 90 days to a 13%, 19%, and 27% higher risk for MACE at those respective doses.

The findings “add to the literature suggesting that there is some risk even with low-dose steroids,” said Michael George, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who did not take part in the research but is familiar with the findings.

“We can see that even glucocorticoids taken several years ago may affect cardiovascular risk but that recent use has a bigger effect on risk,” Dr. George said in an interview. “This study also suggests that very low-dose use affects risk.”

For the new study, Dr. Wallace and colleagues examined a Veterans Affairs database and identified 18,882 patients with RA (mean age, 62.5 years; 84% male; 66% GC users) who met the criteria of being > 40 and < 90 years old. The subjects had an initial VA rheumatology visit during 2010-2018 and were excluded if they had a non-RA rheumatologic disorder, prior MACE, or heart failure. MACE was defined as MI, stroke/TIA, cardiac arrest, coronary revascularization, or death from CV cause.

A total of 16% of the cohort had the largest exposure to GCs, defined as use for 90 days or more; 23% had exposure of 14-89 days, and 14% had exposure of 1-13 days.

The median 5-year MACE risk at baseline was 5.3%, and 3,754 patients (19.9%) had high baseline MACE risk. Incident MACE occurred in 4.1% of patients, and the median time to MACE was 2.67 years (interquartile ratio, 1.26-4.45 years).

Covariates included factors such as age, race, sex, body mass index, smoking status, adjusted Elixhauser index, VA risk score for cardiovascular disease, cancer, hospitalization for infection, number of rheumatology clinic visits, and use of lipid-lowering drugs, opioids, methotrexate, biologics, and hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Wallace noted limitations including the possibility of residual confounding and the influence of background cardiovascular risk. The study didn’t examine the clinical value of taking GCs or compare that to the potential risk. Nor did it examine cost or the risks and benefits of alternative therapeutic options.

A study released earlier this year suggested that patients taking daily prednisolone doses under 5 mg do not have a higher risk of MACE. Previous studies had reached conflicting results.

“Glucocorticoids can provide major benefits to patients, but these benefits must be balanced with the potential risks,” Dr. George said. At low doses, these risks may be small, but they are present. In many cases, escalating DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] therapy may be safer than continuing glucocorticoids.”

He added that the risks of GCs may be especially high in older patients and in those who have cardiovascular risk factors: “Often biologics are avoided in these higher-risk patients. But in fact, in many cases biologics may be the safer choice.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Wallace reported no relevant financial relationships, and some of the other authors reported various ties with industry. Dr. George reported research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen and consulting fees from AbbVie.

SAN DIEGO – Even when taken at low doses and over short periods, glucocorticoids (GCs) were linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) over the long term in a Veterans Affairs population of older, mostly male patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a new retrospective cohort study has found.

The analysis of nearly 19,000 patients, presented by rheumatologist Beth Wallace, MD, MSc, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, showed that the level of risk for MACE rose with the dose, duration, and recency of GC use, in which risk increased significantly at prednisone-equivalent doses as low as 5 mg/day, durations as short as 30 days, and with last use as long as 1 year before MACE.

“Up to half of RA patients in the United States use long-term glucocorticoids despite previous work suggesting they increase MACE in a dose-dependent way,” said Dr. Wallace, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a rheumatologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare Center. “Our group previously presented work suggesting that less than 14 days of glucocorticoid use in a 6-month period is associated with a two-thirds increase in odds of MACE over the following 6 months, with 90 days of use associated with more than twofold increase.”

In recent years, researchers such as Dr. Wallace have focused attention on the risks of GCs in RA. The American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology emphasize avoiding long-term use of GCs in RA and keeping doses as small and over the shortest amount of time as possible.

When Dr. Wallace and colleagues looked at the clinical pattern of GC use for patients with RA during the past 2 years, those who took 5 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10 mg daily doses for 30 days and had stopped at least a year before had risk for MACE that rose significantly by 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, compared with those who didn’t take GCs in the past 2 years.

While those increases were small, risk for MACE rose even more for those who took the same daily doses for 90 days, increasing 10%, 15%, and 21%, respectively. Researchers linked current ongoing use of GCs for the past 90 days to a 13%, 19%, and 27% higher risk for MACE at those respective doses.

The findings “add to the literature suggesting that there is some risk even with low-dose steroids,” said Michael George, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who did not take part in the research but is familiar with the findings.

“We can see that even glucocorticoids taken several years ago may affect cardiovascular risk but that recent use has a bigger effect on risk,” Dr. George said in an interview. “This study also suggests that very low-dose use affects risk.”

For the new study, Dr. Wallace and colleagues examined a Veterans Affairs database and identified 18,882 patients with RA (mean age, 62.5 years; 84% male; 66% GC users) who met the criteria of being > 40 and < 90 years old. The subjects had an initial VA rheumatology visit during 2010-2018 and were excluded if they had a non-RA rheumatologic disorder, prior MACE, or heart failure. MACE was defined as MI, stroke/TIA, cardiac arrest, coronary revascularization, or death from CV cause.

A total of 16% of the cohort had the largest exposure to GCs, defined as use for 90 days or more; 23% had exposure of 14-89 days, and 14% had exposure of 1-13 days.

The median 5-year MACE risk at baseline was 5.3%, and 3,754 patients (19.9%) had high baseline MACE risk. Incident MACE occurred in 4.1% of patients, and the median time to MACE was 2.67 years (interquartile ratio, 1.26-4.45 years).

Covariates included factors such as age, race, sex, body mass index, smoking status, adjusted Elixhauser index, VA risk score for cardiovascular disease, cancer, hospitalization for infection, number of rheumatology clinic visits, and use of lipid-lowering drugs, opioids, methotrexate, biologics, and hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Wallace noted limitations including the possibility of residual confounding and the influence of background cardiovascular risk. The study didn’t examine the clinical value of taking GCs or compare that to the potential risk. Nor did it examine cost or the risks and benefits of alternative therapeutic options.

A study released earlier this year suggested that patients taking daily prednisolone doses under 5 mg do not have a higher risk of MACE. Previous studies had reached conflicting results.

“Glucocorticoids can provide major benefits to patients, but these benefits must be balanced with the potential risks,” Dr. George said. At low doses, these risks may be small, but they are present. In many cases, escalating DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] therapy may be safer than continuing glucocorticoids.”

He added that the risks of GCs may be especially high in older patients and in those who have cardiovascular risk factors: “Often biologics are avoided in these higher-risk patients. But in fact, in many cases biologics may be the safer choice.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Wallace reported no relevant financial relationships, and some of the other authors reported various ties with industry. Dr. George reported research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen and consulting fees from AbbVie.

SAN DIEGO – Even when taken at low doses and over short periods, glucocorticoids (GCs) were linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) over the long term in a Veterans Affairs population of older, mostly male patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a new retrospective cohort study has found.

The analysis of nearly 19,000 patients, presented by rheumatologist Beth Wallace, MD, MSc, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, showed that the level of risk for MACE rose with the dose, duration, and recency of GC use, in which risk increased significantly at prednisone-equivalent doses as low as 5 mg/day, durations as short as 30 days, and with last use as long as 1 year before MACE.

“Up to half of RA patients in the United States use long-term glucocorticoids despite previous work suggesting they increase MACE in a dose-dependent way,” said Dr. Wallace, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a rheumatologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare Center. “Our group previously presented work suggesting that less than 14 days of glucocorticoid use in a 6-month period is associated with a two-thirds increase in odds of MACE over the following 6 months, with 90 days of use associated with more than twofold increase.”

In recent years, researchers such as Dr. Wallace have focused attention on the risks of GCs in RA. The American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology emphasize avoiding long-term use of GCs in RA and keeping doses as small and over the shortest amount of time as possible.

When Dr. Wallace and colleagues looked at the clinical pattern of GC use for patients with RA during the past 2 years, those who took 5 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10 mg daily doses for 30 days and had stopped at least a year before had risk for MACE that rose significantly by 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, compared with those who didn’t take GCs in the past 2 years.

While those increases were small, risk for MACE rose even more for those who took the same daily doses for 90 days, increasing 10%, 15%, and 21%, respectively. Researchers linked current ongoing use of GCs for the past 90 days to a 13%, 19%, and 27% higher risk for MACE at those respective doses.

The findings “add to the literature suggesting that there is some risk even with low-dose steroids,” said Michael George, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who did not take part in the research but is familiar with the findings.

“We can see that even glucocorticoids taken several years ago may affect cardiovascular risk but that recent use has a bigger effect on risk,” Dr. George said in an interview. “This study also suggests that very low-dose use affects risk.”

For the new study, Dr. Wallace and colleagues examined a Veterans Affairs database and identified 18,882 patients with RA (mean age, 62.5 years; 84% male; 66% GC users) who met the criteria of being > 40 and < 90 years old. The subjects had an initial VA rheumatology visit during 2010-2018 and were excluded if they had a non-RA rheumatologic disorder, prior MACE, or heart failure. MACE was defined as MI, stroke/TIA, cardiac arrest, coronary revascularization, or death from CV cause.

A total of 16% of the cohort had the largest exposure to GCs, defined as use for 90 days or more; 23% had exposure of 14-89 days, and 14% had exposure of 1-13 days.

The median 5-year MACE risk at baseline was 5.3%, and 3,754 patients (19.9%) had high baseline MACE risk. Incident MACE occurred in 4.1% of patients, and the median time to MACE was 2.67 years (interquartile ratio, 1.26-4.45 years).

Covariates included factors such as age, race, sex, body mass index, smoking status, adjusted Elixhauser index, VA risk score for cardiovascular disease, cancer, hospitalization for infection, number of rheumatology clinic visits, and use of lipid-lowering drugs, opioids, methotrexate, biologics, and hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Wallace noted limitations including the possibility of residual confounding and the influence of background cardiovascular risk. The study didn’t examine the clinical value of taking GCs or compare that to the potential risk. Nor did it examine cost or the risks and benefits of alternative therapeutic options.

A study released earlier this year suggested that patients taking daily prednisolone doses under 5 mg do not have a higher risk of MACE. Previous studies had reached conflicting results.

“Glucocorticoids can provide major benefits to patients, but these benefits must be balanced with the potential risks,” Dr. George said. At low doses, these risks may be small, but they are present. In many cases, escalating DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] therapy may be safer than continuing glucocorticoids.”

He added that the risks of GCs may be especially high in older patients and in those who have cardiovascular risk factors: “Often biologics are avoided in these higher-risk patients. But in fact, in many cases biologics may be the safer choice.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Wallace reported no relevant financial relationships, and some of the other authors reported various ties with industry. Dr. George reported research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen and consulting fees from AbbVie.

AT ACR 2023

TNF inhibitors may be OK for treating RA-associated interstitial lung disease

SAN DIEGO – Patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) who start a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) appear to have rates of survival and respiratory-related hospitalization similar to those initiating a non-TNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), results from a large pharmacoepidemiologic study show.

“These results challenge some of the findings in prior literature that perhaps TNFi should be avoided in RA-ILD,” lead study investigator Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, said in an interview. The findings were presented during a plenary session at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

Dr. England, associate professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said that while RA-ILD carries a poor prognosis, a paucity of evidence exists on the effectiveness and safety of disease-modifying therapies in this population.

It’s a pleasant surprise “to see that the investigators were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of respiratory hospitalization or death between people with RA-ILD initiating non-TNFi/JAKi versus TNFi. Here is a unique situation where a so called ‘negative’ study contributes important information. This study provides needed safety data, as they were unable to show that TNFi results in worsening of severe RA-ILD outcomes,” Sindhu R. Johnson, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said when asked for comment on the study.

“While this study does not address the use of these medications for the treatment of RA-ILD, these data suggest that TNFi may remain a treatment option for articular disease in people with RA-ILD,” said Dr. Johnson, who was not involved with the study.

For the study, Dr. England and colleagues drew from Veterans Health Administration data between 2006 and 2018 to identify patients with RA-ILD initiating TNFi or non-TNFi biologic/JAKi for the first time. Those who received ILD-focused therapies such as mycophenolate and antifibrotics were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers used validated administrative algorithms requiring multiple RA and ILD diagnostic codes to identify RA-ILD and used 1:1 propensity score matching to compare TNFi and non-TNFi biologic/JAKi factors such as health care use, comorbidities, and several RA-ILD factors, such as pretreatment forced vital capacity, obtained from electronic health records and administrative data. The primary outcome was a composite of time to respiratory-related hospitalization or death using Cox regression models.

Dr. England reported findings from 237 TNFi initiators and 237 non-TNFi/JAKi initiators. Their mean age was 68 years and 92% were male. After matching, the mean standardized differences of variables in the propensity score model improved, but a few variables remained slightly imbalanced, such as two markers of inflammation, inhaled corticosteroid use, and body mass index. The most frequently prescribed TNFi drugs were adalimumab (51%) and etanercept (37%), and the most frequently prescribed non-TNFi/JAKi drugs were rituximab (53%) and abatacept (28%).

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary outcome between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.60). They also observed no significant differences in respiratory hospitalization, all-cause mortality, or respiratory-related death at 1 and 3 years. In sensitivity analyses with modified cohort eligibility requirements, no significant differences in outcomes were observed between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators.

During his presentation at the meeting, Dr. England posed the question: Are TNFi drugs safe to be used in RA-ILD?

“The answer is: It’s complex,” he said. “Our findings don’t suggest that we should be systematically avoiding TNFis with every single person with RA-ILD. But that’s different than whether there are specific subpopulations of RA-ILD for which the choice of these therapies may differ. Unfortunately, we could not address that in this study. We also could not address whether TNFis have efficacy at stopping, slowing, or reversing progression of the ILD itself. This calls for us as a field to gather together and pursue clinical trials to try to generate robust evidence that can guide these important clinical decisions that we’re making with our patients.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its observational design. “So, despite best efforts to minimize bias with pharmacoepidemiologic designs and approaches, there could still be confounding and selection,” he said. “Additionally, RA-ILD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by different patterns and trajectories. While we did account for several RA- and ILD-related factors, we could not account for all heterogeneity in RA-ILD.”

When asked for comment on the study, session moderator Janet Pope, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Western Ontario, London, said that the study findings surprised her.

“Sometimes RA patients on TNFis were thought to have more new or worsening ILD vs. [those on] non-TNFi bDMARDs, but most [data were] from older studies where TNFis were used as initial bDMARD in sicker patients,” she told this news organization. “So, data were confounded previously. Even in this study, there may have been channeling bias as it was not a randomized controlled trial. We need a definitive randomized controlled trial to answer this question of what the most optimal therapy for RA-ILD is.”

Dr. England reports receiving consulting fees and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and several coauthors reported financial relationships from various pharmaceutical companies and medical publishers. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pope reports being a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies. She has received grant/research support from AbbVie/Abbott and Eli Lilly and is an adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) who start a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) appear to have rates of survival and respiratory-related hospitalization similar to those initiating a non-TNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), results from a large pharmacoepidemiologic study show.

“These results challenge some of the findings in prior literature that perhaps TNFi should be avoided in RA-ILD,” lead study investigator Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, said in an interview. The findings were presented during a plenary session at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

Dr. England, associate professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said that while RA-ILD carries a poor prognosis, a paucity of evidence exists on the effectiveness and safety of disease-modifying therapies in this population.

It’s a pleasant surprise “to see that the investigators were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of respiratory hospitalization or death between people with RA-ILD initiating non-TNFi/JAKi versus TNFi. Here is a unique situation where a so called ‘negative’ study contributes important information. This study provides needed safety data, as they were unable to show that TNFi results in worsening of severe RA-ILD outcomes,” Sindhu R. Johnson, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said when asked for comment on the study.

“While this study does not address the use of these medications for the treatment of RA-ILD, these data suggest that TNFi may remain a treatment option for articular disease in people with RA-ILD,” said Dr. Johnson, who was not involved with the study.

For the study, Dr. England and colleagues drew from Veterans Health Administration data between 2006 and 2018 to identify patients with RA-ILD initiating TNFi or non-TNFi biologic/JAKi for the first time. Those who received ILD-focused therapies such as mycophenolate and antifibrotics were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers used validated administrative algorithms requiring multiple RA and ILD diagnostic codes to identify RA-ILD and used 1:1 propensity score matching to compare TNFi and non-TNFi biologic/JAKi factors such as health care use, comorbidities, and several RA-ILD factors, such as pretreatment forced vital capacity, obtained from electronic health records and administrative data. The primary outcome was a composite of time to respiratory-related hospitalization or death using Cox regression models.

Dr. England reported findings from 237 TNFi initiators and 237 non-TNFi/JAKi initiators. Their mean age was 68 years and 92% were male. After matching, the mean standardized differences of variables in the propensity score model improved, but a few variables remained slightly imbalanced, such as two markers of inflammation, inhaled corticosteroid use, and body mass index. The most frequently prescribed TNFi drugs were adalimumab (51%) and etanercept (37%), and the most frequently prescribed non-TNFi/JAKi drugs were rituximab (53%) and abatacept (28%).

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary outcome between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.60). They also observed no significant differences in respiratory hospitalization, all-cause mortality, or respiratory-related death at 1 and 3 years. In sensitivity analyses with modified cohort eligibility requirements, no significant differences in outcomes were observed between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators.

During his presentation at the meeting, Dr. England posed the question: Are TNFi drugs safe to be used in RA-ILD?

“The answer is: It’s complex,” he said. “Our findings don’t suggest that we should be systematically avoiding TNFis with every single person with RA-ILD. But that’s different than whether there are specific subpopulations of RA-ILD for which the choice of these therapies may differ. Unfortunately, we could not address that in this study. We also could not address whether TNFis have efficacy at stopping, slowing, or reversing progression of the ILD itself. This calls for us as a field to gather together and pursue clinical trials to try to generate robust evidence that can guide these important clinical decisions that we’re making with our patients.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its observational design. “So, despite best efforts to minimize bias with pharmacoepidemiologic designs and approaches, there could still be confounding and selection,” he said. “Additionally, RA-ILD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by different patterns and trajectories. While we did account for several RA- and ILD-related factors, we could not account for all heterogeneity in RA-ILD.”

When asked for comment on the study, session moderator Janet Pope, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Western Ontario, London, said that the study findings surprised her.

“Sometimes RA patients on TNFis were thought to have more new or worsening ILD vs. [those on] non-TNFi bDMARDs, but most [data were] from older studies where TNFis were used as initial bDMARD in sicker patients,” she told this news organization. “So, data were confounded previously. Even in this study, there may have been channeling bias as it was not a randomized controlled trial. We need a definitive randomized controlled trial to answer this question of what the most optimal therapy for RA-ILD is.”

Dr. England reports receiving consulting fees and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and several coauthors reported financial relationships from various pharmaceutical companies and medical publishers. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pope reports being a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies. She has received grant/research support from AbbVie/Abbott and Eli Lilly and is an adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) who start a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) appear to have rates of survival and respiratory-related hospitalization similar to those initiating a non-TNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), results from a large pharmacoepidemiologic study show.

“These results challenge some of the findings in prior literature that perhaps TNFi should be avoided in RA-ILD,” lead study investigator Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, said in an interview. The findings were presented during a plenary session at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

Dr. England, associate professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said that while RA-ILD carries a poor prognosis, a paucity of evidence exists on the effectiveness and safety of disease-modifying therapies in this population.

It’s a pleasant surprise “to see that the investigators were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of respiratory hospitalization or death between people with RA-ILD initiating non-TNFi/JAKi versus TNFi. Here is a unique situation where a so called ‘negative’ study contributes important information. This study provides needed safety data, as they were unable to show that TNFi results in worsening of severe RA-ILD outcomes,” Sindhu R. Johnson, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said when asked for comment on the study.

“While this study does not address the use of these medications for the treatment of RA-ILD, these data suggest that TNFi may remain a treatment option for articular disease in people with RA-ILD,” said Dr. Johnson, who was not involved with the study.

For the study, Dr. England and colleagues drew from Veterans Health Administration data between 2006 and 2018 to identify patients with RA-ILD initiating TNFi or non-TNFi biologic/JAKi for the first time. Those who received ILD-focused therapies such as mycophenolate and antifibrotics were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers used validated administrative algorithms requiring multiple RA and ILD diagnostic codes to identify RA-ILD and used 1:1 propensity score matching to compare TNFi and non-TNFi biologic/JAKi factors such as health care use, comorbidities, and several RA-ILD factors, such as pretreatment forced vital capacity, obtained from electronic health records and administrative data. The primary outcome was a composite of time to respiratory-related hospitalization or death using Cox regression models.

Dr. England reported findings from 237 TNFi initiators and 237 non-TNFi/JAKi initiators. Their mean age was 68 years and 92% were male. After matching, the mean standardized differences of variables in the propensity score model improved, but a few variables remained slightly imbalanced, such as two markers of inflammation, inhaled corticosteroid use, and body mass index. The most frequently prescribed TNFi drugs were adalimumab (51%) and etanercept (37%), and the most frequently prescribed non-TNFi/JAKi drugs were rituximab (53%) and abatacept (28%).

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary outcome between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.60). They also observed no significant differences in respiratory hospitalization, all-cause mortality, or respiratory-related death at 1 and 3 years. In sensitivity analyses with modified cohort eligibility requirements, no significant differences in outcomes were observed between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators.

During his presentation at the meeting, Dr. England posed the question: Are TNFi drugs safe to be used in RA-ILD?

“The answer is: It’s complex,” he said. “Our findings don’t suggest that we should be systematically avoiding TNFis with every single person with RA-ILD. But that’s different than whether there are specific subpopulations of RA-ILD for which the choice of these therapies may differ. Unfortunately, we could not address that in this study. We also could not address whether TNFis have efficacy at stopping, slowing, or reversing progression of the ILD itself. This calls for us as a field to gather together and pursue clinical trials to try to generate robust evidence that can guide these important clinical decisions that we’re making with our patients.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its observational design. “So, despite best efforts to minimize bias with pharmacoepidemiologic designs and approaches, there could still be confounding and selection,” he said. “Additionally, RA-ILD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by different patterns and trajectories. While we did account for several RA- and ILD-related factors, we could not account for all heterogeneity in RA-ILD.”

When asked for comment on the study, session moderator Janet Pope, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Western Ontario, London, said that the study findings surprised her.

“Sometimes RA patients on TNFis were thought to have more new or worsening ILD vs. [those on] non-TNFi bDMARDs, but most [data were] from older studies where TNFis were used as initial bDMARD in sicker patients,” she told this news organization. “So, data were confounded previously. Even in this study, there may have been channeling bias as it was not a randomized controlled trial. We need a definitive randomized controlled trial to answer this question of what the most optimal therapy for RA-ILD is.”

Dr. England reports receiving consulting fees and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and several coauthors reported financial relationships from various pharmaceutical companies and medical publishers. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pope reports being a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies. She has received grant/research support from AbbVie/Abbott and Eli Lilly and is an adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2023

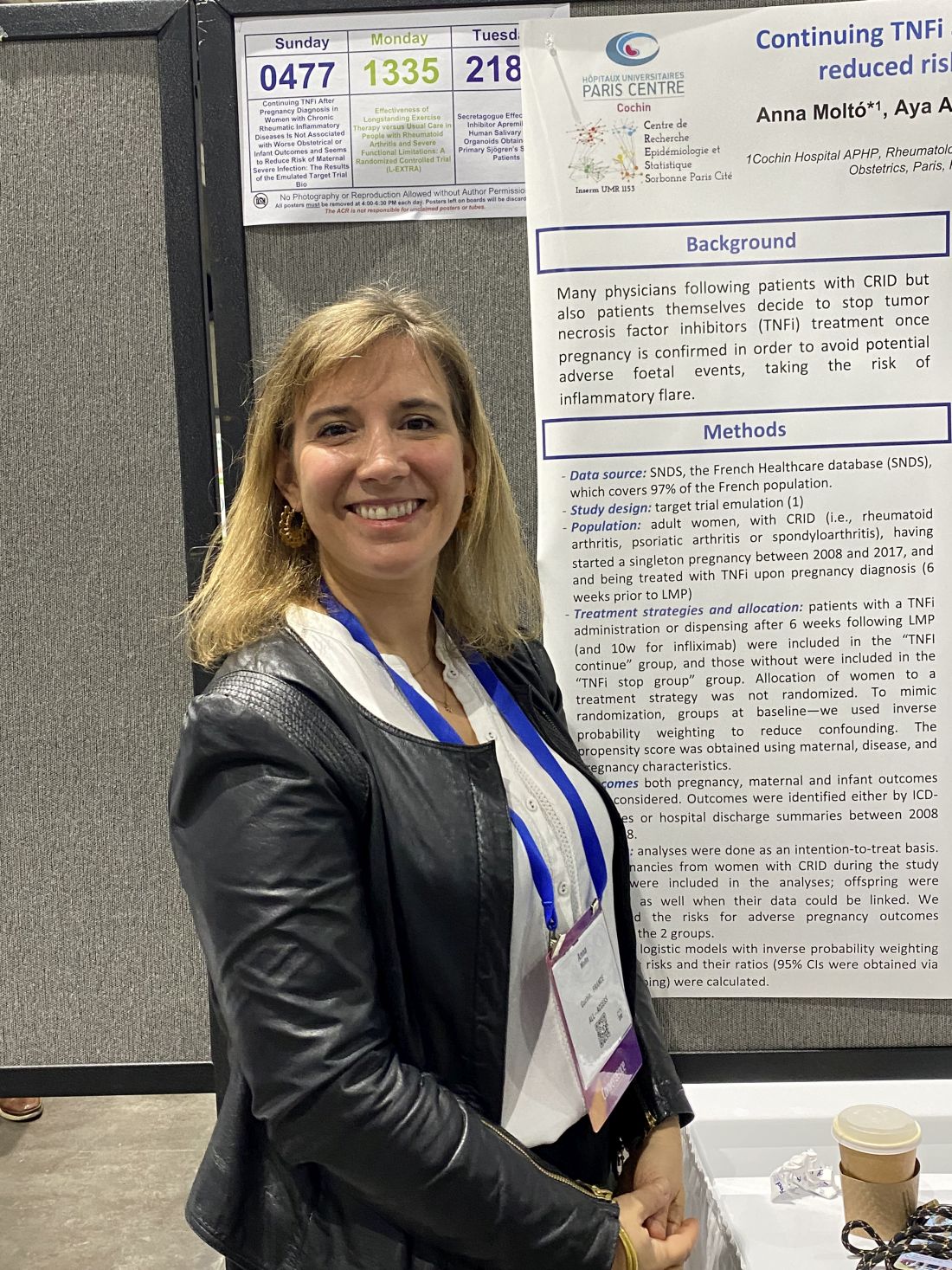

TNF blockers not associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.

Previous research, largely from pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggests that taking a TNFi during pregnancy is safe, and 2020 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend continuing therapy prior to and during pregnancy; however, many people still stop taking the drugs during pregnancy for fear of potentially harming the fetus.

To better understand how TNFi use affected pregnancy outcomes, Dr. Moltó and colleagues analyzed data from a French nationwide health insurance database to identify adult women with chronic rheumatic inflammatory disease. All women included in the cohort had a singleton pregnancy between 2008 and 2017 and were taking a TNFi upon pregnancy diagnosis.

Patients who restarted TNFi after initially pausing because of pregnancy were included in the continuation group.

Researchers identified more than 2,000 pregnancies, including 1,503 in individuals with spondyloarthritis and 579 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients were, on average, 31 years old and were diagnosed with a rheumatic disease 4 years prior to their pregnancy.

About 72% (n = 1,497) discontinued TNFi after learning they were pregnant, and 584 individuals continued treatment. Dr. Moltó noted that data from more recent years might have captured lower discontinuation rates among pregnant individuals, but those data were not available for the study.

There was no difference in unfavorable obstetrical or infant outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, major congenital malformation, and severe infection of the infant requiring hospitalization. Somewhat surprisingly, the data showed that women who discontinued a TNFi were more likely to be hospitalized for infection either during their pregnancy or up to 6 weeks after delivery, compared with those who continued therapy (1.3% vs. 0.2%, respectively).

Dr. Moltó is currently looking into what could be behind this counterintuitive result, but she hypothesizes that patients who had stopped TNFi may have been taking more glucocorticoids.

“At our institution, there is generally a comfort level with continuing TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, at least until about 36 weeks,” said Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Sometimes, there is concern for risk of infection to the infant, depending on the type of TNFi being used, she added during a press conference.

“I think that these are really informative and supportive data to let women know that they probably have a really good chance of doing very well during the pregnancy if they continue” their TNFi, said Dr. Tedeschi, who was not involved with the study.

TNF discontinuation on the decline

In a related study, researchers at McGill University, Montreal, found that TNFi discontinuation prior to pregnancy had decreased over time in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Using a database of U.S. insurance claims, they identified 3,372 women with RA, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who previously used a TNFi and gave birth between 2011 and 2019. A patient was considered to have used a TNFi if she had filled a prescription or had an infusion procedure insurance claim within 12 weeks before the gestational period or anytime during pregnancy. Researchers did not have time-specific data to account for women who stopped treatment at pregnancy diagnosis.

Nearly half (47%) of all identified pregnancies were in individuals with IBD, and the rest included patients with RA (24%), psoriasis or PsA (16%), AS (3%), or more than one diagnosis (10%).

In total, 14% of women discontinued TNFi use in the 12 weeks before becoming pregnant and did not restart. From 2011 to 2013, 19% of patients stopped their TNFi, but this proportion decreased overtime, with 10% of patients stopping therapy from 2017 to 2019 (P < .0001).

This decline “possibly reflects the increase in real-world evidence about the safety of TNFi in pregnancy. That research, in turn, led to new guidelines recommending the continuation of TNFi during pregnancy,” first author Leah Flatman, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at McGill, said in an interview. “I think we can see this potentially as good news.”

More patients with RA, psoriasis/PsA, and AS discontinued TNFi therapy prior to conception (23%-25%), compared with those with IBD (5%).

Ms. Flatman noted that her study and Moltó’s study complement each other by providing data on individuals stopping TNFi prior to conception versus those stopping treatment after pregnancy diagnosis.

“These findings demonstrate that continuing TNFi during pregnancy appears not to be associated with an increase in adverse obstetrical or infant outcomes,” Ms. Flatman said of Dr. Moltó’s study. “As guidelines currently recommend continuing TNFi, studies like this help demonstrate that the guideline changes do not appear to be associated with an increase in adverse events.”

Dr. Moltó and Ms. Flatman disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tedeschi has worked as a consultant for Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.

Previous research, largely from pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggests that taking a TNFi during pregnancy is safe, and 2020 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend continuing therapy prior to and during pregnancy; however, many people still stop taking the drugs during pregnancy for fear of potentially harming the fetus.

To better understand how TNFi use affected pregnancy outcomes, Dr. Moltó and colleagues analyzed data from a French nationwide health insurance database to identify adult women with chronic rheumatic inflammatory disease. All women included in the cohort had a singleton pregnancy between 2008 and 2017 and were taking a TNFi upon pregnancy diagnosis.

Patients who restarted TNFi after initially pausing because of pregnancy were included in the continuation group.

Researchers identified more than 2,000 pregnancies, including 1,503 in individuals with spondyloarthritis and 579 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients were, on average, 31 years old and were diagnosed with a rheumatic disease 4 years prior to their pregnancy.

About 72% (n = 1,497) discontinued TNFi after learning they were pregnant, and 584 individuals continued treatment. Dr. Moltó noted that data from more recent years might have captured lower discontinuation rates among pregnant individuals, but those data were not available for the study.

There was no difference in unfavorable obstetrical or infant outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, major congenital malformation, and severe infection of the infant requiring hospitalization. Somewhat surprisingly, the data showed that women who discontinued a TNFi were more likely to be hospitalized for infection either during their pregnancy or up to 6 weeks after delivery, compared with those who continued therapy (1.3% vs. 0.2%, respectively).

Dr. Moltó is currently looking into what could be behind this counterintuitive result, but she hypothesizes that patients who had stopped TNFi may have been taking more glucocorticoids.

“At our institution, there is generally a comfort level with continuing TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, at least until about 36 weeks,” said Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Sometimes, there is concern for risk of infection to the infant, depending on the type of TNFi being used, she added during a press conference.

“I think that these are really informative and supportive data to let women know that they probably have a really good chance of doing very well during the pregnancy if they continue” their TNFi, said Dr. Tedeschi, who was not involved with the study.

TNF discontinuation on the decline

In a related study, researchers at McGill University, Montreal, found that TNFi discontinuation prior to pregnancy had decreased over time in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Using a database of U.S. insurance claims, they identified 3,372 women with RA, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who previously used a TNFi and gave birth between 2011 and 2019. A patient was considered to have used a TNFi if she had filled a prescription or had an infusion procedure insurance claim within 12 weeks before the gestational period or anytime during pregnancy. Researchers did not have time-specific data to account for women who stopped treatment at pregnancy diagnosis.

Nearly half (47%) of all identified pregnancies were in individuals with IBD, and the rest included patients with RA (24%), psoriasis or PsA (16%), AS (3%), or more than one diagnosis (10%).

In total, 14% of women discontinued TNFi use in the 12 weeks before becoming pregnant and did not restart. From 2011 to 2013, 19% of patients stopped their TNFi, but this proportion decreased overtime, with 10% of patients stopping therapy from 2017 to 2019 (P < .0001).

This decline “possibly reflects the increase in real-world evidence about the safety of TNFi in pregnancy. That research, in turn, led to new guidelines recommending the continuation of TNFi during pregnancy,” first author Leah Flatman, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at McGill, said in an interview. “I think we can see this potentially as good news.”

More patients with RA, psoriasis/PsA, and AS discontinued TNFi therapy prior to conception (23%-25%), compared with those with IBD (5%).

Ms. Flatman noted that her study and Moltó’s study complement each other by providing data on individuals stopping TNFi prior to conception versus those stopping treatment after pregnancy diagnosis.

“These findings demonstrate that continuing TNFi during pregnancy appears not to be associated with an increase in adverse obstetrical or infant outcomes,” Ms. Flatman said of Dr. Moltó’s study. “As guidelines currently recommend continuing TNFi, studies like this help demonstrate that the guideline changes do not appear to be associated with an increase in adverse events.”

Dr. Moltó and Ms. Flatman disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tedeschi has worked as a consultant for Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.

Previous research, largely from pregnant patients with inflammatory bowel disease, suggests that taking a TNFi during pregnancy is safe, and 2020 ACR guidelines conditionally recommend continuing therapy prior to and during pregnancy; however, many people still stop taking the drugs during pregnancy for fear of potentially harming the fetus.

To better understand how TNFi use affected pregnancy outcomes, Dr. Moltó and colleagues analyzed data from a French nationwide health insurance database to identify adult women with chronic rheumatic inflammatory disease. All women included in the cohort had a singleton pregnancy between 2008 and 2017 and were taking a TNFi upon pregnancy diagnosis.

Patients who restarted TNFi after initially pausing because of pregnancy were included in the continuation group.

Researchers identified more than 2,000 pregnancies, including 1,503 in individuals with spondyloarthritis and 579 individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Patients were, on average, 31 years old and were diagnosed with a rheumatic disease 4 years prior to their pregnancy.

About 72% (n = 1,497) discontinued TNFi after learning they were pregnant, and 584 individuals continued treatment. Dr. Moltó noted that data from more recent years might have captured lower discontinuation rates among pregnant individuals, but those data were not available for the study.

There was no difference in unfavorable obstetrical or infant outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, major congenital malformation, and severe infection of the infant requiring hospitalization. Somewhat surprisingly, the data showed that women who discontinued a TNFi were more likely to be hospitalized for infection either during their pregnancy or up to 6 weeks after delivery, compared with those who continued therapy (1.3% vs. 0.2%, respectively).

Dr. Moltó is currently looking into what could be behind this counterintuitive result, but she hypothesizes that patients who had stopped TNFi may have been taking more glucocorticoids.

“At our institution, there is generally a comfort level with continuing TNF inhibitors during pregnancy, at least until about 36 weeks,” said Sara K. Tedeschi, MD, MPH, a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. Sometimes, there is concern for risk of infection to the infant, depending on the type of TNFi being used, she added during a press conference.

“I think that these are really informative and supportive data to let women know that they probably have a really good chance of doing very well during the pregnancy if they continue” their TNFi, said Dr. Tedeschi, who was not involved with the study.

TNF discontinuation on the decline

In a related study, researchers at McGill University, Montreal, found that TNFi discontinuation prior to pregnancy had decreased over time in individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases.

Using a database of U.S. insurance claims, they identified 3,372 women with RA, ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and/or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) who previously used a TNFi and gave birth between 2011 and 2019. A patient was considered to have used a TNFi if she had filled a prescription or had an infusion procedure insurance claim within 12 weeks before the gestational period or anytime during pregnancy. Researchers did not have time-specific data to account for women who stopped treatment at pregnancy diagnosis.

Nearly half (47%) of all identified pregnancies were in individuals with IBD, and the rest included patients with RA (24%), psoriasis or PsA (16%), AS (3%), or more than one diagnosis (10%).

In total, 14% of women discontinued TNFi use in the 12 weeks before becoming pregnant and did not restart. From 2011 to 2013, 19% of patients stopped their TNFi, but this proportion decreased overtime, with 10% of patients stopping therapy from 2017 to 2019 (P < .0001).

This decline “possibly reflects the increase in real-world evidence about the safety of TNFi in pregnancy. That research, in turn, led to new guidelines recommending the continuation of TNFi during pregnancy,” first author Leah Flatman, a PhD candidate in epidemiology at McGill, said in an interview. “I think we can see this potentially as good news.”

More patients with RA, psoriasis/PsA, and AS discontinued TNFi therapy prior to conception (23%-25%), compared with those with IBD (5%).

Ms. Flatman noted that her study and Moltó’s study complement each other by providing data on individuals stopping TNFi prior to conception versus those stopping treatment after pregnancy diagnosis.

“These findings demonstrate that continuing TNFi during pregnancy appears not to be associated with an increase in adverse obstetrical or infant outcomes,” Ms. Flatman said of Dr. Moltó’s study. “As guidelines currently recommend continuing TNFi, studies like this help demonstrate that the guideline changes do not appear to be associated with an increase in adverse events.”

Dr. Moltó and Ms. Flatman disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tedeschi has worked as a consultant for Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2023

Pregnancy in rheumatic disease quadruples risk of cardiovascular events

SAN DIEGO – Pregnant individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) are at least four times more likely to experience an acute cardiovascular event (CVE) than are pregnant individuals without these conditions, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Pregnant individuals with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) had a 15-fold increase in CVE risk.

Patients who experienced CVEs were also more likely to experience preterm birth and other adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs).

Rashmi Dhital, MD, a rheumatology fellow at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues examined the medical records of pregnant individuals in California who had delivered singleton live-born infants from 2005 to 2020. Using data from the Study of Outcomes in Mothers and Infants (SOMI) database, an administrative population-based birth cohort in California, they identified more than 7 million individuals, 19,340 with ARDs and 7,758 with APS.

They then analyzed how many patients experienced an acute CVE during pregnancy and up to 6 weeks after giving birth.

CVEs occurred in 2.0% of patients with ARDs, 6.9% of individuals with APS, and 0.4% of women without these conditions. CVE risk was four times higher in the ARDs group (adjusted relative risk, 4.1; 95% confidence interval, 3.7-4.5) and nearly 15 times higher in the APS group (aRR, 14.7; 95% CI, 13.5-16.0) than in the comparison group. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had a sixfold higher risk of CVE, which was further exacerbated by concomitant APS (18-fold higher risk) or lupus nephritis (15-fold higher risk).

Dr. Dhital also classified CVEs as either venous thromboembolism and non-VTE events. Pregnant patients with APS had a high risk for VTE-only CVE (40-fold greater) and a 3.7-fold higher risk of non-VTE events, compared with pregnant patients without these conditions. Patients with SLE along with lupus nephritis had a 20-fold increased risk of VTE-only CVE and an 11-fold higher risk of non-VTE CVE.

Although the study grouped rheumatic diseases together, “lupus is generally driving these results,” Sharon Kolasinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, noted in an interview. She moderated the plenary session where the research was presented. “If you take out lupus, then what is the risk? That would be an interesting question.”

Between 25% and 30% of all CVEs occurred in the postpartum period, highlighting the importance of close monitoring of cardiovascular risks and events in women with ARDs or APS both during pregnancy and postpartum, Dr. Dhital noted.

Recognizing these risks “can sometimes be challenging due to a lower suspicion of CVE in younger patients, and also symptoms overlap with normal pregnancy,” Dr. Dhital said during her plenary presentation. Working with other clinical teams could help physicians detect these risks in patients.

“It’s important for us to remember that there’s increased risk of cardiovascular events in pregnancy in our patients. It’s uncommon, but it’s not zero,” added Dr. Kolasinski, and this study highlighted when physicians should be more focused about that risk.

Dr. Dhital noted there were some limitations to the study that are inherent in using administrative databases for research that relies on ICD codes, including “the availability of information on disease activity, medications, and labs, which may restrict clinical interpretation.”

SOMI data reinforced by National Inpatient Sample study

The findings were complemented by a study using the National Inpatient Sample database to explore CVE risk in pregnant individuals with various rheumatic diseases. Lead author Karun Shrestha, MD, a resident physician at St. Barnabas Hospital in New York, and colleagues identified delivery hospitalizations from 2016 to 2019 for individuals with SLE, RA, and systemic vasculitis and looked for CVEs including preeclampsia, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), heart failure, stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, and VTE.

Out of over 3.4 million delivery hospitalizations, researchers identified 5,900 individuals with SLE, 4,895 with RA, and 325 with vasculitis. After adjusting for confounding factors such as race, age, insurance, and other comorbidities, SLE was identified as an independent risk factor for preeclampsia (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1), arrhythmia (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.73-5.79), and venous thrombosis (OR, 8.4; 95% CI, 2.9-22.1). Vasculitis was tied to increased risk for preeclampsia (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2-11.3), stroke (OR, 513.3; 95% CI, 114-2,284), heart failure (OR, 24.17; 95% CI, 4.68-124.6), and PPCM (OR, 66.7; 95% CI, 8.7-509.4). RA was tied to an increased risk for preeclampsia (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.05-2.1).

Patients with SLE or vasculitis had longer, more costly hospital stays, compared with those without these conditions, and they experienced higher rates of in-hospital mortality. While previous research has demonstrated that patients with SLE have higher risk of cardiac events, there is less literature on CVE risk in pregnancies for vasculitis, Dr. Shrestha said in an interview.

“It’s something to work on,” he said.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes higher with ARDs, APS

In a second abstract also led by Dr. Dhital using SOMI data, researchers found that pregnant individuals with ARDs or APS had a higher risk of experiencing an APO – preterm birth or small-for-gestational age – than individuals without these conditions. CVEs exacerbated that risk, regardless of underlying chronic health conditions.

Over half of patients with an ARD and a CVE during pregnancy experienced an APO – most commonly preterm birth. More than one in four pregnant individuals without ARD or APS who experienced a CVE also had an APO.

After differentiating CVEs as either VTE and non-VTE events, patients with ARD and a non-VTE CVE had a fivefold greater risk of early preterm birth (< 32 weeks) and a threefold higher risk of moderate preterm birth (32 to < 34 weeks).

“These findings highlight the need for close monitoring and management of pregnant women, not only for adverse outcomes, but also for cardiovascular risks and events, in order to identify those at the highest risk for adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote. “This need is particularly significant for individuals with ARDs, as 53.4% of our population with an ARD and CVE in pregnancy experienced an APO.”

Dr. Dhital, Dr. Kolasinski, and Dr. Shrestha disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Pregnant individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) are at least four times more likely to experience an acute cardiovascular event (CVE) than are pregnant individuals without these conditions, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Pregnant individuals with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) had a 15-fold increase in CVE risk.

Patients who experienced CVEs were also more likely to experience preterm birth and other adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs).

Rashmi Dhital, MD, a rheumatology fellow at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues examined the medical records of pregnant individuals in California who had delivered singleton live-born infants from 2005 to 2020. Using data from the Study of Outcomes in Mothers and Infants (SOMI) database, an administrative population-based birth cohort in California, they identified more than 7 million individuals, 19,340 with ARDs and 7,758 with APS.

They then analyzed how many patients experienced an acute CVE during pregnancy and up to 6 weeks after giving birth.

CVEs occurred in 2.0% of patients with ARDs, 6.9% of individuals with APS, and 0.4% of women without these conditions. CVE risk was four times higher in the ARDs group (adjusted relative risk, 4.1; 95% confidence interval, 3.7-4.5) and nearly 15 times higher in the APS group (aRR, 14.7; 95% CI, 13.5-16.0) than in the comparison group. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had a sixfold higher risk of CVE, which was further exacerbated by concomitant APS (18-fold higher risk) or lupus nephritis (15-fold higher risk).

Dr. Dhital also classified CVEs as either venous thromboembolism and non-VTE events. Pregnant patients with APS had a high risk for VTE-only CVE (40-fold greater) and a 3.7-fold higher risk of non-VTE events, compared with pregnant patients without these conditions. Patients with SLE along with lupus nephritis had a 20-fold increased risk of VTE-only CVE and an 11-fold higher risk of non-VTE CVE.

Although the study grouped rheumatic diseases together, “lupus is generally driving these results,” Sharon Kolasinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, noted in an interview. She moderated the plenary session where the research was presented. “If you take out lupus, then what is the risk? That would be an interesting question.”

Between 25% and 30% of all CVEs occurred in the postpartum period, highlighting the importance of close monitoring of cardiovascular risks and events in women with ARDs or APS both during pregnancy and postpartum, Dr. Dhital noted.

Recognizing these risks “can sometimes be challenging due to a lower suspicion of CVE in younger patients, and also symptoms overlap with normal pregnancy,” Dr. Dhital said during her plenary presentation. Working with other clinical teams could help physicians detect these risks in patients.

“It’s important for us to remember that there’s increased risk of cardiovascular events in pregnancy in our patients. It’s uncommon, but it’s not zero,” added Dr. Kolasinski, and this study highlighted when physicians should be more focused about that risk.

Dr. Dhital noted there were some limitations to the study that are inherent in using administrative databases for research that relies on ICD codes, including “the availability of information on disease activity, medications, and labs, which may restrict clinical interpretation.”

SOMI data reinforced by National Inpatient Sample study

The findings were complemented by a study using the National Inpatient Sample database to explore CVE risk in pregnant individuals with various rheumatic diseases. Lead author Karun Shrestha, MD, a resident physician at St. Barnabas Hospital in New York, and colleagues identified delivery hospitalizations from 2016 to 2019 for individuals with SLE, RA, and systemic vasculitis and looked for CVEs including preeclampsia, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), heart failure, stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, and VTE.

Out of over 3.4 million delivery hospitalizations, researchers identified 5,900 individuals with SLE, 4,895 with RA, and 325 with vasculitis. After adjusting for confounding factors such as race, age, insurance, and other comorbidities, SLE was identified as an independent risk factor for preeclampsia (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1), arrhythmia (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.73-5.79), and venous thrombosis (OR, 8.4; 95% CI, 2.9-22.1). Vasculitis was tied to increased risk for preeclampsia (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2-11.3), stroke (OR, 513.3; 95% CI, 114-2,284), heart failure (OR, 24.17; 95% CI, 4.68-124.6), and PPCM (OR, 66.7; 95% CI, 8.7-509.4). RA was tied to an increased risk for preeclampsia (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.05-2.1).

Patients with SLE or vasculitis had longer, more costly hospital stays, compared with those without these conditions, and they experienced higher rates of in-hospital mortality. While previous research has demonstrated that patients with SLE have higher risk of cardiac events, there is less literature on CVE risk in pregnancies for vasculitis, Dr. Shrestha said in an interview.

“It’s something to work on,” he said.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes higher with ARDs, APS

In a second abstract also led by Dr. Dhital using SOMI data, researchers found that pregnant individuals with ARDs or APS had a higher risk of experiencing an APO – preterm birth or small-for-gestational age – than individuals without these conditions. CVEs exacerbated that risk, regardless of underlying chronic health conditions.

Over half of patients with an ARD and a CVE during pregnancy experienced an APO – most commonly preterm birth. More than one in four pregnant individuals without ARD or APS who experienced a CVE also had an APO.

After differentiating CVEs as either VTE and non-VTE events, patients with ARD and a non-VTE CVE had a fivefold greater risk of early preterm birth (< 32 weeks) and a threefold higher risk of moderate preterm birth (32 to < 34 weeks).

“These findings highlight the need for close monitoring and management of pregnant women, not only for adverse outcomes, but also for cardiovascular risks and events, in order to identify those at the highest risk for adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote. “This need is particularly significant for individuals with ARDs, as 53.4% of our population with an ARD and CVE in pregnancy experienced an APO.”

Dr. Dhital, Dr. Kolasinski, and Dr. Shrestha disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Pregnant individuals with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARDs) are at least four times more likely to experience an acute cardiovascular event (CVE) than are pregnant individuals without these conditions, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. Pregnant individuals with primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) had a 15-fold increase in CVE risk.

Patients who experienced CVEs were also more likely to experience preterm birth and other adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs).

Rashmi Dhital, MD, a rheumatology fellow at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues examined the medical records of pregnant individuals in California who had delivered singleton live-born infants from 2005 to 2020. Using data from the Study of Outcomes in Mothers and Infants (SOMI) database, an administrative population-based birth cohort in California, they identified more than 7 million individuals, 19,340 with ARDs and 7,758 with APS.

They then analyzed how many patients experienced an acute CVE during pregnancy and up to 6 weeks after giving birth.

CVEs occurred in 2.0% of patients with ARDs, 6.9% of individuals with APS, and 0.4% of women without these conditions. CVE risk was four times higher in the ARDs group (adjusted relative risk, 4.1; 95% confidence interval, 3.7-4.5) and nearly 15 times higher in the APS group (aRR, 14.7; 95% CI, 13.5-16.0) than in the comparison group. Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had a sixfold higher risk of CVE, which was further exacerbated by concomitant APS (18-fold higher risk) or lupus nephritis (15-fold higher risk).

Dr. Dhital also classified CVEs as either venous thromboembolism and non-VTE events. Pregnant patients with APS had a high risk for VTE-only CVE (40-fold greater) and a 3.7-fold higher risk of non-VTE events, compared with pregnant patients without these conditions. Patients with SLE along with lupus nephritis had a 20-fold increased risk of VTE-only CVE and an 11-fold higher risk of non-VTE CVE.

Although the study grouped rheumatic diseases together, “lupus is generally driving these results,” Sharon Kolasinski, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, noted in an interview. She moderated the plenary session where the research was presented. “If you take out lupus, then what is the risk? That would be an interesting question.”

Between 25% and 30% of all CVEs occurred in the postpartum period, highlighting the importance of close monitoring of cardiovascular risks and events in women with ARDs or APS both during pregnancy and postpartum, Dr. Dhital noted.

Recognizing these risks “can sometimes be challenging due to a lower suspicion of CVE in younger patients, and also symptoms overlap with normal pregnancy,” Dr. Dhital said during her plenary presentation. Working with other clinical teams could help physicians detect these risks in patients.

“It’s important for us to remember that there’s increased risk of cardiovascular events in pregnancy in our patients. It’s uncommon, but it’s not zero,” added Dr. Kolasinski, and this study highlighted when physicians should be more focused about that risk.

Dr. Dhital noted there were some limitations to the study that are inherent in using administrative databases for research that relies on ICD codes, including “the availability of information on disease activity, medications, and labs, which may restrict clinical interpretation.”

SOMI data reinforced by National Inpatient Sample study

The findings were complemented by a study using the National Inpatient Sample database to explore CVE risk in pregnant individuals with various rheumatic diseases. Lead author Karun Shrestha, MD, a resident physician at St. Barnabas Hospital in New York, and colleagues identified delivery hospitalizations from 2016 to 2019 for individuals with SLE, RA, and systemic vasculitis and looked for CVEs including preeclampsia, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), heart failure, stroke, cardiac arrhythmias, and VTE.

Out of over 3.4 million delivery hospitalizations, researchers identified 5,900 individuals with SLE, 4,895 with RA, and 325 with vasculitis. After adjusting for confounding factors such as race, age, insurance, and other comorbidities, SLE was identified as an independent risk factor for preeclampsia (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.1), arrhythmia (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.73-5.79), and venous thrombosis (OR, 8.4; 95% CI, 2.9-22.1). Vasculitis was tied to increased risk for preeclampsia (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 2-11.3), stroke (OR, 513.3; 95% CI, 114-2,284), heart failure (OR, 24.17; 95% CI, 4.68-124.6), and PPCM (OR, 66.7; 95% CI, 8.7-509.4). RA was tied to an increased risk for preeclampsia (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.05-2.1).

Patients with SLE or vasculitis had longer, more costly hospital stays, compared with those without these conditions, and they experienced higher rates of in-hospital mortality. While previous research has demonstrated that patients with SLE have higher risk of cardiac events, there is less literature on CVE risk in pregnancies for vasculitis, Dr. Shrestha said in an interview.

“It’s something to work on,” he said.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes higher with ARDs, APS

In a second abstract also led by Dr. Dhital using SOMI data, researchers found that pregnant individuals with ARDs or APS had a higher risk of experiencing an APO – preterm birth or small-for-gestational age – than individuals without these conditions. CVEs exacerbated that risk, regardless of underlying chronic health conditions.

Over half of patients with an ARD and a CVE during pregnancy experienced an APO – most commonly preterm birth. More than one in four pregnant individuals without ARD or APS who experienced a CVE also had an APO.

After differentiating CVEs as either VTE and non-VTE events, patients with ARD and a non-VTE CVE had a fivefold greater risk of early preterm birth (< 32 weeks) and a threefold higher risk of moderate preterm birth (32 to < 34 weeks).

“These findings highlight the need for close monitoring and management of pregnant women, not only for adverse outcomes, but also for cardiovascular risks and events, in order to identify those at the highest risk for adverse outcomes,” the authors wrote. “This need is particularly significant for individuals with ARDs, as 53.4% of our population with an ARD and CVE in pregnancy experienced an APO.”

Dr. Dhital, Dr. Kolasinski, and Dr. Shrestha disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2023

Review estimates acne risk with JAK inhibitor therapy

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.