User login

Sleep apnea may correlate with anxiety, depression in patients with PCOS

a study suggests.

This finding could have implications for screening and treatment, Diana Xiaojie Zhou, MD, said at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

“Routine OSA screening in women with PCOS should be considered in the setting of existing depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Zhou, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of California, San Francisco. “Referral for OSA diagnosis and treatment in those who screen positive may have added psychological benefits in this population, as has been seen in the general population.”

Patients with PCOS experience a range of comorbidities, including higher rates of psychological disorders and OSA, she said.

OSA has been associated with depression and anxiety in the general population, and research indicates that treatment, such as with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), may have psychological benefits, such as reduced depression symptoms.

PCOS guidelines recommend screening for OSA to identify and alleviate symptoms such as fatigue that may to contribute to mood disorders. “However, there is a lack of studies assessing the relationship between OSA and depression and anxiety specifically in women with PCOS,” Dr. Zhou said.

A cross-sectional study

To evaluate whether OSA is associated with depression and anxiety in women with PCOS, Dr. Zhou and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of all women seen at a multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at university between June 2017 and June 2020.

Participants had a diagnosis of PCOS clinically confirmed by the Rotterdam criteria. Researchers determined OSA risk using the Berlin questionnaire, which is divided into three domains. A positive score in two or more domains indicates a high risk of OSA.

The investigators used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess depression symptoms, and they used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) to assess anxiety symptoms.

Researchers used two-sided t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test to evaluate for differences in patient characteristics. They performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine the odds of moderate to severe symptoms of depression (that is, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater) and anxiety (a GAD-7 score of 10 or greater) among patients with a high risk of OSA, compared with patients with a low risk of OSA. They adjusted for age, body mass index, free testosterone level, and insulin resistance using the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR).

The researchers examined data from 201 patients: 125 with a low risk of OSA and 76 with a high risk of OSA. The average age of the patients was 28 years.

On average, patients in the high-risk OSA group had a greater body mass index (37.9 vs. 26.5), a higher level of free testosterone (6.5 ng/dL vs. 4.5 ng/dL), and a higher HOMA-IR score (7 vs. 3.1), relative to those with a low risk of OSA. In addition, a greater percentage of patients with a high risk of OSA experienced oligomenorrhea (84.9% vs. 70.5%).

The average PHQ-9 score was significantly higher in the high-risk OSA group (12 vs. 8.3), as was the average GAD-7 score (8.9 vs. 6.1).

In univariate analyses, having a high risk of OSA increased the likelihood of moderate or severe depression or anxiety approximately threefold.

In multivariate analyses, a high risk of OSA remained significantly associated with moderate or severe depression or anxiety, with an odds ratio of about 2.5. “Of note, BMI was a statistically significant predictor in the univariate analyses, but not so in the multivariate analyses,” Dr. Zhou said.

Although the investigators assessed OSA, depression, and anxiety using validated questionnaires, a study with clinically confirmed diagnoses of those conditions would strengthen these findings, she said.

Various possible links

Investigators have proposed various links between PCOS, OSA, and depression and anxiety, Dr. Zhou noted. Features of PCOS such as insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia increase the risk of OSA. “The sleep loss and fragmentation and hypoxia that define OSA then serve to increase sympathetic tone and oxidative stress, which then potentially can lead to an increase in depression and anxiety,” Dr. Zhou said.

The results suggests that treating OSA “may have added psychological benefits for women with PCOS and highlights the broad health implications of this condition,” Marla Lujan, PhD, chair of the ASRM’s androgen excess special interest group, said in a society news release.

“The cause of PCOS is still not well understood, but we do know that 1 in 10 women in their childbearing years suffer from PCOS,” said Dr. Lujan, of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “In addition to infertility, PCOS is also associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications such as hypertension and abnormal blood lipids.”

In a discussion following Dr. Zhou’s presentation, Alice D. Domar, PhD, said the study was eye opening.

Dr. Domar, director of integrative care at Boston IVF and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that she does not typically discuss sleep apnea with patients. “For those of us who routinely work with PCOS patients, we are always looking for more information.”

Although PCOS guidelines mention screening for OSA, Dr. Zhou expects that few generalists who see PCOS patients or even subspecialists actually do.

Nevertheless, the potential for intervention is fascinating, she said. And if treating OSA also reduced a patient’s need for psychiatric medications, there could be added benefit in PCOS due to the metabolic side effects that accompany some of the drugs.

Dr. Zhou and Dr. Lujan had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Domar is a co-owner of FertiCalm, FertiStrong, and Aliz Health Apps, and a speaker for Ferring, EMD Serono, Merck, and Abbott.

SOURCE: Zhou DX et al. ASRM 2020. Abstract O-146.

a study suggests.

This finding could have implications for screening and treatment, Diana Xiaojie Zhou, MD, said at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

“Routine OSA screening in women with PCOS should be considered in the setting of existing depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Zhou, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of California, San Francisco. “Referral for OSA diagnosis and treatment in those who screen positive may have added psychological benefits in this population, as has been seen in the general population.”

Patients with PCOS experience a range of comorbidities, including higher rates of psychological disorders and OSA, she said.

OSA has been associated with depression and anxiety in the general population, and research indicates that treatment, such as with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), may have psychological benefits, such as reduced depression symptoms.

PCOS guidelines recommend screening for OSA to identify and alleviate symptoms such as fatigue that may to contribute to mood disorders. “However, there is a lack of studies assessing the relationship between OSA and depression and anxiety specifically in women with PCOS,” Dr. Zhou said.

A cross-sectional study

To evaluate whether OSA is associated with depression and anxiety in women with PCOS, Dr. Zhou and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of all women seen at a multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at university between June 2017 and June 2020.

Participants had a diagnosis of PCOS clinically confirmed by the Rotterdam criteria. Researchers determined OSA risk using the Berlin questionnaire, which is divided into three domains. A positive score in two or more domains indicates a high risk of OSA.

The investigators used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess depression symptoms, and they used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) to assess anxiety symptoms.

Researchers used two-sided t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test to evaluate for differences in patient characteristics. They performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine the odds of moderate to severe symptoms of depression (that is, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater) and anxiety (a GAD-7 score of 10 or greater) among patients with a high risk of OSA, compared with patients with a low risk of OSA. They adjusted for age, body mass index, free testosterone level, and insulin resistance using the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR).

The researchers examined data from 201 patients: 125 with a low risk of OSA and 76 with a high risk of OSA. The average age of the patients was 28 years.

On average, patients in the high-risk OSA group had a greater body mass index (37.9 vs. 26.5), a higher level of free testosterone (6.5 ng/dL vs. 4.5 ng/dL), and a higher HOMA-IR score (7 vs. 3.1), relative to those with a low risk of OSA. In addition, a greater percentage of patients with a high risk of OSA experienced oligomenorrhea (84.9% vs. 70.5%).

The average PHQ-9 score was significantly higher in the high-risk OSA group (12 vs. 8.3), as was the average GAD-7 score (8.9 vs. 6.1).

In univariate analyses, having a high risk of OSA increased the likelihood of moderate or severe depression or anxiety approximately threefold.

In multivariate analyses, a high risk of OSA remained significantly associated with moderate or severe depression or anxiety, with an odds ratio of about 2.5. “Of note, BMI was a statistically significant predictor in the univariate analyses, but not so in the multivariate analyses,” Dr. Zhou said.

Although the investigators assessed OSA, depression, and anxiety using validated questionnaires, a study with clinically confirmed diagnoses of those conditions would strengthen these findings, she said.

Various possible links

Investigators have proposed various links between PCOS, OSA, and depression and anxiety, Dr. Zhou noted. Features of PCOS such as insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia increase the risk of OSA. “The sleep loss and fragmentation and hypoxia that define OSA then serve to increase sympathetic tone and oxidative stress, which then potentially can lead to an increase in depression and anxiety,” Dr. Zhou said.

The results suggests that treating OSA “may have added psychological benefits for women with PCOS and highlights the broad health implications of this condition,” Marla Lujan, PhD, chair of the ASRM’s androgen excess special interest group, said in a society news release.

“The cause of PCOS is still not well understood, but we do know that 1 in 10 women in their childbearing years suffer from PCOS,” said Dr. Lujan, of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “In addition to infertility, PCOS is also associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications such as hypertension and abnormal blood lipids.”

In a discussion following Dr. Zhou’s presentation, Alice D. Domar, PhD, said the study was eye opening.

Dr. Domar, director of integrative care at Boston IVF and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that she does not typically discuss sleep apnea with patients. “For those of us who routinely work with PCOS patients, we are always looking for more information.”

Although PCOS guidelines mention screening for OSA, Dr. Zhou expects that few generalists who see PCOS patients or even subspecialists actually do.

Nevertheless, the potential for intervention is fascinating, she said. And if treating OSA also reduced a patient’s need for psychiatric medications, there could be added benefit in PCOS due to the metabolic side effects that accompany some of the drugs.

Dr. Zhou and Dr. Lujan had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Domar is a co-owner of FertiCalm, FertiStrong, and Aliz Health Apps, and a speaker for Ferring, EMD Serono, Merck, and Abbott.

SOURCE: Zhou DX et al. ASRM 2020. Abstract O-146.

a study suggests.

This finding could have implications for screening and treatment, Diana Xiaojie Zhou, MD, said at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2020 annual meeting, held virtually this year.

“Routine OSA screening in women with PCOS should be considered in the setting of existing depression and anxiety,” said Dr. Zhou, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of California, San Francisco. “Referral for OSA diagnosis and treatment in those who screen positive may have added psychological benefits in this population, as has been seen in the general population.”

Patients with PCOS experience a range of comorbidities, including higher rates of psychological disorders and OSA, she said.

OSA has been associated with depression and anxiety in the general population, and research indicates that treatment, such as with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), may have psychological benefits, such as reduced depression symptoms.

PCOS guidelines recommend screening for OSA to identify and alleviate symptoms such as fatigue that may to contribute to mood disorders. “However, there is a lack of studies assessing the relationship between OSA and depression and anxiety specifically in women with PCOS,” Dr. Zhou said.

A cross-sectional study

To evaluate whether OSA is associated with depression and anxiety in women with PCOS, Dr. Zhou and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of all women seen at a multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at university between June 2017 and June 2020.

Participants had a diagnosis of PCOS clinically confirmed by the Rotterdam criteria. Researchers determined OSA risk using the Berlin questionnaire, which is divided into three domains. A positive score in two or more domains indicates a high risk of OSA.

The investigators used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess depression symptoms, and they used the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) to assess anxiety symptoms.

Researchers used two-sided t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher’s exact test to evaluate for differences in patient characteristics. They performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to determine the odds of moderate to severe symptoms of depression (that is, a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater) and anxiety (a GAD-7 score of 10 or greater) among patients with a high risk of OSA, compared with patients with a low risk of OSA. They adjusted for age, body mass index, free testosterone level, and insulin resistance using the Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR).

The researchers examined data from 201 patients: 125 with a low risk of OSA and 76 with a high risk of OSA. The average age of the patients was 28 years.

On average, patients in the high-risk OSA group had a greater body mass index (37.9 vs. 26.5), a higher level of free testosterone (6.5 ng/dL vs. 4.5 ng/dL), and a higher HOMA-IR score (7 vs. 3.1), relative to those with a low risk of OSA. In addition, a greater percentage of patients with a high risk of OSA experienced oligomenorrhea (84.9% vs. 70.5%).

The average PHQ-9 score was significantly higher in the high-risk OSA group (12 vs. 8.3), as was the average GAD-7 score (8.9 vs. 6.1).

In univariate analyses, having a high risk of OSA increased the likelihood of moderate or severe depression or anxiety approximately threefold.

In multivariate analyses, a high risk of OSA remained significantly associated with moderate or severe depression or anxiety, with an odds ratio of about 2.5. “Of note, BMI was a statistically significant predictor in the univariate analyses, but not so in the multivariate analyses,” Dr. Zhou said.

Although the investigators assessed OSA, depression, and anxiety using validated questionnaires, a study with clinically confirmed diagnoses of those conditions would strengthen these findings, she said.

Various possible links

Investigators have proposed various links between PCOS, OSA, and depression and anxiety, Dr. Zhou noted. Features of PCOS such as insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia increase the risk of OSA. “The sleep loss and fragmentation and hypoxia that define OSA then serve to increase sympathetic tone and oxidative stress, which then potentially can lead to an increase in depression and anxiety,” Dr. Zhou said.

The results suggests that treating OSA “may have added psychological benefits for women with PCOS and highlights the broad health implications of this condition,” Marla Lujan, PhD, chair of the ASRM’s androgen excess special interest group, said in a society news release.

“The cause of PCOS is still not well understood, but we do know that 1 in 10 women in their childbearing years suffer from PCOS,” said Dr. Lujan, of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. “In addition to infertility, PCOS is also associated with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications such as hypertension and abnormal blood lipids.”

In a discussion following Dr. Zhou’s presentation, Alice D. Domar, PhD, said the study was eye opening.

Dr. Domar, director of integrative care at Boston IVF and associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said that she does not typically discuss sleep apnea with patients. “For those of us who routinely work with PCOS patients, we are always looking for more information.”

Although PCOS guidelines mention screening for OSA, Dr. Zhou expects that few generalists who see PCOS patients or even subspecialists actually do.

Nevertheless, the potential for intervention is fascinating, she said. And if treating OSA also reduced a patient’s need for psychiatric medications, there could be added benefit in PCOS due to the metabolic side effects that accompany some of the drugs.

Dr. Zhou and Dr. Lujan had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Domar is a co-owner of FertiCalm, FertiStrong, and Aliz Health Apps, and a speaker for Ferring, EMD Serono, Merck, and Abbott.

SOURCE: Zhou DX et al. ASRM 2020. Abstract O-146.

FROM ASRM 2020

FDA clears smartphone app to interrupt PTSD-related nightmares

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared for marketing a smartphone app that can detect and interrupt nightmares in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The NightWare app, from Minneapolis-based NightWare Inc., runs on the Apple Watch and Apple iPhone.

During sleep, Apple Watch sensors monitor heart rate and body movement. These data are used to create a unique sleep profile using a proprietary algorithm.

When the NightWare app detects that a patient is experiencing a nightmare based on changes in heart rate and movement, it provides slight vibrations through the Apple Watch to arouse the patient and interrupt the nightmare, without fully awakening the patient, the company notes.

NightWare is available by prescription only and is intended for use in adults aged 22 years and older with PTSD.

“Sleep is an essential part of a person’s daily routine. However, certain adults who have a nightmare disorder or who experience nightmares from PTSD are not able to get the rest they need,” Carlos Peña, PhD, director, Office of Neurological and Physical Medicine Devices, Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the FDA, said in a news release.

This authorization “offers a new, low-risk treatment option that uses digital technology in an effort to provide temporary relief from sleep disturbance related to nightmares,” said Dr. Peña.

NightWare was tested in a 30-day randomized, sham-controlled trial of 70 patients. Patients in the sham group wore the device, but no vibrations were provided.

Both the sham and active groups showed improvement in sleep on standard sleep scales, with the active group showing greater improvement than sham. “The evidence demonstrated the probable benefits outweighed the probable risks,” the FDA said in a statement.

and other recommended therapies for PTSD-associated nightmares and nightmare disorder, the agency said.

NightWare was granted breakthrough device designation for the treatment of nightmares in patients with PTSD. The device reviewed through the de novo premarket pathway, a regulatory pathway for some low- to moderate-risk devices of a new type.

Along with this marketing authorization, the FDA is establishing “special controls” designed to provide a “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for tests of this type,” the agency said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared for marketing a smartphone app that can detect and interrupt nightmares in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The NightWare app, from Minneapolis-based NightWare Inc., runs on the Apple Watch and Apple iPhone.

During sleep, Apple Watch sensors monitor heart rate and body movement. These data are used to create a unique sleep profile using a proprietary algorithm.

When the NightWare app detects that a patient is experiencing a nightmare based on changes in heart rate and movement, it provides slight vibrations through the Apple Watch to arouse the patient and interrupt the nightmare, without fully awakening the patient, the company notes.

NightWare is available by prescription only and is intended for use in adults aged 22 years and older with PTSD.

“Sleep is an essential part of a person’s daily routine. However, certain adults who have a nightmare disorder or who experience nightmares from PTSD are not able to get the rest they need,” Carlos Peña, PhD, director, Office of Neurological and Physical Medicine Devices, Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the FDA, said in a news release.

This authorization “offers a new, low-risk treatment option that uses digital technology in an effort to provide temporary relief from sleep disturbance related to nightmares,” said Dr. Peña.

NightWare was tested in a 30-day randomized, sham-controlled trial of 70 patients. Patients in the sham group wore the device, but no vibrations were provided.

Both the sham and active groups showed improvement in sleep on standard sleep scales, with the active group showing greater improvement than sham. “The evidence demonstrated the probable benefits outweighed the probable risks,” the FDA said in a statement.

and other recommended therapies for PTSD-associated nightmares and nightmare disorder, the agency said.

NightWare was granted breakthrough device designation for the treatment of nightmares in patients with PTSD. The device reviewed through the de novo premarket pathway, a regulatory pathway for some low- to moderate-risk devices of a new type.

Along with this marketing authorization, the FDA is establishing “special controls” designed to provide a “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for tests of this type,” the agency said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared for marketing a smartphone app that can detect and interrupt nightmares in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The NightWare app, from Minneapolis-based NightWare Inc., runs on the Apple Watch and Apple iPhone.

During sleep, Apple Watch sensors monitor heart rate and body movement. These data are used to create a unique sleep profile using a proprietary algorithm.

When the NightWare app detects that a patient is experiencing a nightmare based on changes in heart rate and movement, it provides slight vibrations through the Apple Watch to arouse the patient and interrupt the nightmare, without fully awakening the patient, the company notes.

NightWare is available by prescription only and is intended for use in adults aged 22 years and older with PTSD.

“Sleep is an essential part of a person’s daily routine. However, certain adults who have a nightmare disorder or who experience nightmares from PTSD are not able to get the rest they need,” Carlos Peña, PhD, director, Office of Neurological and Physical Medicine Devices, Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the FDA, said in a news release.

This authorization “offers a new, low-risk treatment option that uses digital technology in an effort to provide temporary relief from sleep disturbance related to nightmares,” said Dr. Peña.

NightWare was tested in a 30-day randomized, sham-controlled trial of 70 patients. Patients in the sham group wore the device, but no vibrations were provided.

Both the sham and active groups showed improvement in sleep on standard sleep scales, with the active group showing greater improvement than sham. “The evidence demonstrated the probable benefits outweighed the probable risks,” the FDA said in a statement.

and other recommended therapies for PTSD-associated nightmares and nightmare disorder, the agency said.

NightWare was granted breakthrough device designation for the treatment of nightmares in patients with PTSD. The device reviewed through the de novo premarket pathway, a regulatory pathway for some low- to moderate-risk devices of a new type.

Along with this marketing authorization, the FDA is establishing “special controls” designed to provide a “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for tests of this type,” the agency said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Distinguish ‘sleepiness’ from ‘fatigue’ to help diagnose hypersomnia

, according to Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD.

Fatigue, feeling tired, and lack of energy are common complaints that accompany insomnia and psychiatric disorders, but these patients do not fall asleep quickly in a restful setting and will have normal multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) in a laboratory. In contrast, excessive sleepiness, or hypersomnia, occurs when patients sleep more than 11 hours in a 24-hour period.

Patients with hypersomnia fall asleep in low stimulus situations and devote more energy to staying awake during situations. This excessive sleepiness can be dangerous in the context of activities such as driving, Dr. Benca said. These patients will also have low sleep latencies (< 8 minutes) when tested through MSLT in a laboratory, she added. Patients with hypersomnia may be irritable, have reduced attention or concentration, and have poor memory.

The primary cause of hypersomnia is sleep deprivation, but “both hypersomnia and fatigue are common complaints in psychiatric patients, including depression, bipolar disorder, seasonal affective disorder, [and] psychosis,” Dr. Benca explained. Other causes of hypersomnia include sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, circadian rhythm disorders and periodic limb movements, neurologic or degenerative disorders, mental disorders, and effects of medication. Idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy are uncommon causes of hypersomnia and usually diagnosed in a sleep laboratory setting, she said.

In patients with depression, hypersomnia looks like patients having “nonimperative sleepiness,” Dr. Benca said. “They may spend a lot of time in bed; they may report long and nonrefreshing naps or long sleep time.”

There also is an issue with sleep inertia in patients with depression and hypersomnia, and with patients taking a long time to wake up and begin their day. In these patients, “when we put them in the sleep laboratory, the objective studies generally do not show that they are excessively sleepy, despite their reports of subjectively being sleepy,” she said.

There is not much objective MSLT or subjective measure data for hypersomnia in patients with schizophrenia despite these patients reporting daytime sleepiness or hypersomnolence, Dr. Benca admitted. Hypersomnia in patients with schizophrenia may be related to drug effects, poor sleep hygiene, circadian rhythm abnormalities, or comorbid sleep disorders. “Excessive sleepiness may also be related to the schizophrenia itself,” she said.

Treatments for hypersomnia

The first priority for patients with hypersomnia is to avoid sleep deprivation and practice good sleep hygiene – factors that are important both in insomnia and hypersomnia. “Make sure that patients are having adequate time in bed and having regular hours of sleep,” Dr. Benca said.

For patients with comorbid psychiatric, medical and sleep disorders, focus on getting rid of medications that may cause sleepiness, including sedating medications and antidepressants, and consider using stimulants if appropriate. While there are Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for narcolepsy and some are approved for hypersomnia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), none are officially approved to treat hypersomnia in psychiatric patients.

“Whenever we use these drugs for those reasons, we’re using them off label,” Dr. Benca said.

Modafinil/armodafinil, approved for narcolepsy, shift-work disorder, and OSA in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, is one off-label option for patients with hypersomnia. “They are lower potency and less addictive than the amphetamines, [with] fewer side effects,” Dr. Benca explained, but should be prescribed with caution in some women because of potential reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives. Side effects of modafinil include headache, nausea, eosinophilia, diarrhea, dry mouth, and anorexia.

Methylphenidate is another option for hypersomnia, available in racemic mixture, pure D-isomer, and time-release formulations.

Patients taking methylphenidate may experience nervousness, insomnia, anorexia, nausea, dizziness, hypertension, hypotension, hypersensitivity reactions, tachycardia, and headache as side effects.

For patients with central nervous system hypersomnias, amphetamines can be used, with methamphetamines having a “very similar profile” and similar side effects, including insomnia, restlessness, tachycardia, dizziness, diarrhea, constipation, hypertension, impotence, and rare cases of psychotic episodes.

Practice parameters released by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine in 2007 suggest that modafinil may have efficacy in idiopathic hypersomnia, Parkinson’s disease, myotonic dystrophy, and multiple sclerosis. The practice parameters also suggest hypersomnias of central origin can be treated with modafinil, amphetamine, methamphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate based on evidence or “long history of use” (Sleep. 2007;30:1705-11).

“Interestingly, there is no mention of psychiatric disorders in these practice parameters, and they report that there are mixed results using stimulants off label for sleepiness and fatigue in traumatic brain injury and poststroke fatigue,” Dr. Benca said.

Dr. Benca reported that she is a consultant to Eisai, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, and Sunovion. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, according to Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD.

Fatigue, feeling tired, and lack of energy are common complaints that accompany insomnia and psychiatric disorders, but these patients do not fall asleep quickly in a restful setting and will have normal multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) in a laboratory. In contrast, excessive sleepiness, or hypersomnia, occurs when patients sleep more than 11 hours in a 24-hour period.

Patients with hypersomnia fall asleep in low stimulus situations and devote more energy to staying awake during situations. This excessive sleepiness can be dangerous in the context of activities such as driving, Dr. Benca said. These patients will also have low sleep latencies (< 8 minutes) when tested through MSLT in a laboratory, she added. Patients with hypersomnia may be irritable, have reduced attention or concentration, and have poor memory.

The primary cause of hypersomnia is sleep deprivation, but “both hypersomnia and fatigue are common complaints in psychiatric patients, including depression, bipolar disorder, seasonal affective disorder, [and] psychosis,” Dr. Benca explained. Other causes of hypersomnia include sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, circadian rhythm disorders and periodic limb movements, neurologic or degenerative disorders, mental disorders, and effects of medication. Idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy are uncommon causes of hypersomnia and usually diagnosed in a sleep laboratory setting, she said.

In patients with depression, hypersomnia looks like patients having “nonimperative sleepiness,” Dr. Benca said. “They may spend a lot of time in bed; they may report long and nonrefreshing naps or long sleep time.”

There also is an issue with sleep inertia in patients with depression and hypersomnia, and with patients taking a long time to wake up and begin their day. In these patients, “when we put them in the sleep laboratory, the objective studies generally do not show that they are excessively sleepy, despite their reports of subjectively being sleepy,” she said.

There is not much objective MSLT or subjective measure data for hypersomnia in patients with schizophrenia despite these patients reporting daytime sleepiness or hypersomnolence, Dr. Benca admitted. Hypersomnia in patients with schizophrenia may be related to drug effects, poor sleep hygiene, circadian rhythm abnormalities, or comorbid sleep disorders. “Excessive sleepiness may also be related to the schizophrenia itself,” she said.

Treatments for hypersomnia

The first priority for patients with hypersomnia is to avoid sleep deprivation and practice good sleep hygiene – factors that are important both in insomnia and hypersomnia. “Make sure that patients are having adequate time in bed and having regular hours of sleep,” Dr. Benca said.

For patients with comorbid psychiatric, medical and sleep disorders, focus on getting rid of medications that may cause sleepiness, including sedating medications and antidepressants, and consider using stimulants if appropriate. While there are Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for narcolepsy and some are approved for hypersomnia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), none are officially approved to treat hypersomnia in psychiatric patients.

“Whenever we use these drugs for those reasons, we’re using them off label,” Dr. Benca said.

Modafinil/armodafinil, approved for narcolepsy, shift-work disorder, and OSA in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, is one off-label option for patients with hypersomnia. “They are lower potency and less addictive than the amphetamines, [with] fewer side effects,” Dr. Benca explained, but should be prescribed with caution in some women because of potential reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives. Side effects of modafinil include headache, nausea, eosinophilia, diarrhea, dry mouth, and anorexia.

Methylphenidate is another option for hypersomnia, available in racemic mixture, pure D-isomer, and time-release formulations.

Patients taking methylphenidate may experience nervousness, insomnia, anorexia, nausea, dizziness, hypertension, hypotension, hypersensitivity reactions, tachycardia, and headache as side effects.

For patients with central nervous system hypersomnias, amphetamines can be used, with methamphetamines having a “very similar profile” and similar side effects, including insomnia, restlessness, tachycardia, dizziness, diarrhea, constipation, hypertension, impotence, and rare cases of psychotic episodes.

Practice parameters released by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine in 2007 suggest that modafinil may have efficacy in idiopathic hypersomnia, Parkinson’s disease, myotonic dystrophy, and multiple sclerosis. The practice parameters also suggest hypersomnias of central origin can be treated with modafinil, amphetamine, methamphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate based on evidence or “long history of use” (Sleep. 2007;30:1705-11).

“Interestingly, there is no mention of psychiatric disorders in these practice parameters, and they report that there are mixed results using stimulants off label for sleepiness and fatigue in traumatic brain injury and poststroke fatigue,” Dr. Benca said.

Dr. Benca reported that she is a consultant to Eisai, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, and Sunovion. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, according to Ruth M. Benca, MD, PhD.

Fatigue, feeling tired, and lack of energy are common complaints that accompany insomnia and psychiatric disorders, but these patients do not fall asleep quickly in a restful setting and will have normal multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) in a laboratory. In contrast, excessive sleepiness, or hypersomnia, occurs when patients sleep more than 11 hours in a 24-hour period.

Patients with hypersomnia fall asleep in low stimulus situations and devote more energy to staying awake during situations. This excessive sleepiness can be dangerous in the context of activities such as driving, Dr. Benca said. These patients will also have low sleep latencies (< 8 minutes) when tested through MSLT in a laboratory, she added. Patients with hypersomnia may be irritable, have reduced attention or concentration, and have poor memory.

The primary cause of hypersomnia is sleep deprivation, but “both hypersomnia and fatigue are common complaints in psychiatric patients, including depression, bipolar disorder, seasonal affective disorder, [and] psychosis,” Dr. Benca explained. Other causes of hypersomnia include sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, circadian rhythm disorders and periodic limb movements, neurologic or degenerative disorders, mental disorders, and effects of medication. Idiopathic hypersomnia and narcolepsy are uncommon causes of hypersomnia and usually diagnosed in a sleep laboratory setting, she said.

In patients with depression, hypersomnia looks like patients having “nonimperative sleepiness,” Dr. Benca said. “They may spend a lot of time in bed; they may report long and nonrefreshing naps or long sleep time.”

There also is an issue with sleep inertia in patients with depression and hypersomnia, and with patients taking a long time to wake up and begin their day. In these patients, “when we put them in the sleep laboratory, the objective studies generally do not show that they are excessively sleepy, despite their reports of subjectively being sleepy,” she said.

There is not much objective MSLT or subjective measure data for hypersomnia in patients with schizophrenia despite these patients reporting daytime sleepiness or hypersomnolence, Dr. Benca admitted. Hypersomnia in patients with schizophrenia may be related to drug effects, poor sleep hygiene, circadian rhythm abnormalities, or comorbid sleep disorders. “Excessive sleepiness may also be related to the schizophrenia itself,” she said.

Treatments for hypersomnia

The first priority for patients with hypersomnia is to avoid sleep deprivation and practice good sleep hygiene – factors that are important both in insomnia and hypersomnia. “Make sure that patients are having adequate time in bed and having regular hours of sleep,” Dr. Benca said.

For patients with comorbid psychiatric, medical and sleep disorders, focus on getting rid of medications that may cause sleepiness, including sedating medications and antidepressants, and consider using stimulants if appropriate. While there are Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for narcolepsy and some are approved for hypersomnia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), none are officially approved to treat hypersomnia in psychiatric patients.

“Whenever we use these drugs for those reasons, we’re using them off label,” Dr. Benca said.

Modafinil/armodafinil, approved for narcolepsy, shift-work disorder, and OSA in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, is one off-label option for patients with hypersomnia. “They are lower potency and less addictive than the amphetamines, [with] fewer side effects,” Dr. Benca explained, but should be prescribed with caution in some women because of potential reduced efficacy of oral contraceptives. Side effects of modafinil include headache, nausea, eosinophilia, diarrhea, dry mouth, and anorexia.

Methylphenidate is another option for hypersomnia, available in racemic mixture, pure D-isomer, and time-release formulations.

Patients taking methylphenidate may experience nervousness, insomnia, anorexia, nausea, dizziness, hypertension, hypotension, hypersensitivity reactions, tachycardia, and headache as side effects.

For patients with central nervous system hypersomnias, amphetamines can be used, with methamphetamines having a “very similar profile” and similar side effects, including insomnia, restlessness, tachycardia, dizziness, diarrhea, constipation, hypertension, impotence, and rare cases of psychotic episodes.

Practice parameters released by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine in 2007 suggest that modafinil may have efficacy in idiopathic hypersomnia, Parkinson’s disease, myotonic dystrophy, and multiple sclerosis. The practice parameters also suggest hypersomnias of central origin can be treated with modafinil, amphetamine, methamphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate based on evidence or “long history of use” (Sleep. 2007;30:1705-11).

“Interestingly, there is no mention of psychiatric disorders in these practice parameters, and they report that there are mixed results using stimulants off label for sleepiness and fatigue in traumatic brain injury and poststroke fatigue,” Dr. Benca said.

Dr. Benca reported that she is a consultant to Eisai, Idorsia, Jazz, Merck, and Sunovion. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE

Biometric changes on fitness trackers, smartwatches detect COVID-19

A smartphone app that combines passively collected physiologic data from wearable devices, such as fitness trackers, and self-reported symptoms can discriminate between COVID-19–positive and –negative individuals among those who report symptoms, new data suggest.

After analyzing data from more than 30,000 participants, researchers from the Digital Engagement and Tracking for Early Control and Treatment (DETECT) study concluded that adding individual changes in sensor data improves models based on symptoms alone for differentiating symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 positive and symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 negative.

The combination can potentially identify infection clusters before wider community spread occurs, Giorgio Quer, PhD, and colleagues report in an article published online Oct. 29 in Nature Medicine. DETECT investigators note that marrying participant-reported symptoms with personal sensor data, such as deviation from normal sleep duration and resting heart rate, resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.73-0.86) for differentiating between symptomatic individuals who were positive and those who were negative for COVID-19.

“By better characterizing each individual’s unique baseline, you can then identify changes that may indicate that someone has a viral illness,” said Dr. Quer, director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. “In previous research, we found that the proportion of individuals with elevated resting heart rate and sleep duration compared with their normal could significantly improve real-time detection of influenza-like illness rates at the state level,” he said in an interview.

Thus, continuous passively captured data may be a useful adjunct to bricks-and-mortar site testing, which is generally a one-off or infrequent sampling assay and is not always easily accessible, he added. Furthermore, traditional screening with temperature and symptom reporting is inadequate. An elevation in temperature is not as common as frequently believed for people who test positive for COVID-19, Dr. Quer continued. “Early identification via sensor variables of those who are presymptomatic or even asymptomatic would be especially valuable, as people may potentially be infectious during this period, and early detection is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Quer said.

According to his group, adding these physiologic changes from baseline values significantly outperformed detection (P < .01) using a British model described in an earlier study by by Cristina Menni, PhD, and associates. That method, in which symptoms were considered alone, yielded an AUC of 0.71 (IQR, 0.63-0.79).

According to Dr. Quer, one in five Americans currently wear an electronic device. “If we could enroll even a small percentage of these individuals, we’d be able to potentially identify clusters before they have the opportunity to spread,” he said.

DETECT study details

During the period March 15 to June 7, 2020, the study enrolled 30,529 participants from all 50 states. They ranged in age from younger than 35 years (23.1%) to older than 65 years (12.8%); the majority (63.5%) were aged 35-65 years, and 62% were women. Sensor devices in use by the cohort included Fitbit activity trackers (78.4%) and Apple HealthKit (31.2%).

Participants downloaded an app called MyDataHelps, which collects smartwatch and activity tracker information, including self-reported symptoms and diagnostic testing results. The app also monitors changes from baseline in resting heart rate, sleep duration, and physical activity, as measured by steps.

Overall, 3,811 participants reported having at least one symptom of some kind (e.g., fatigue, cough, dyspnea, loss of taste or smell). Of these, 54 reported testing positive for COVID-19, and 279 reported testing negative.

Sleep and activity were significantly different for the positive and negative groups, with an AUC of 0.68 (IQR, 0.57-0.79) for the sleep metric and 0.69 (IQR, 0.61-0.77) for the activity metric, suggesting that these parameters were more affected in COVID-19–positive participants.

When the investigators combined resting heart rate, sleep, and activity into a single metric, predictive performance improved to an AUC of 0.72 (IQR, 0.64-0.80).

The next step, Dr. Quer said, is to include an alert to notify users of possible infection.

Alerting users to possible COVID-19 infection

In a similar study, an alert feature was already incorporated. The study, led by Michael P. Snyder, PhD, director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, will soon be published online in Nature Biomedical Engineering. In that study, presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 was achieved in more than 80% of participants using resting heart rate.

“The median is 4 days prior to symptom formation,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We have an alarm system to notify people when their heart rate is elevated. So a positive signal from a smartwatch can be used to follow up by polymerase chain reaction [testing].”

Dr. Snyder said these approaches offer a roadmap to containing widespread infections. “Public health authorities need to be open to these technologies and begin incorporating them into their tracking,” he said. “Right now, people do temperature checks, which are of limited value. Resting heart rate is much better information.”

Although the DETECT researchers have not yet received feedback on their results, they believe public health authorities could recommend the use of such apps. “These are devices that people routinely wear for tracking their fitness and sleep, so it would be relatively easy to use the data for viral illness tracking,” said co–lead author Jennifer Radin, PhD, an epidemiologist at Scripps. “Testing resources are still limited and don’t allow for routine serial testing of individuals who may be asymptomatic or presymptomatic. Wearables can offer a different way to routinely monitor and screen people for changes in their data that may indicate COVID-19.”

The marshaling of data through consumer digital platforms to fight the coronavirus is gaining ground. New York State and New Jersey are already embracing smartphone apps to alert individuals to possible exposure to the virus.

More than 710,000 New Yorkers have downloaded the COVID NY Alert app, launched in October to help protect individuals and communities from COVID-19 by sending alerts without compromising privacy or personal information. “Upon receiving a notification about a potential exposure, users are then able to self-quarantine, get tested, and reduce the potential exposure risk to family, friends, coworkers, and others,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health, said in an interview.

And recently the Mayo Clinic and Safe Health Systems launched a platform to store COVID-19 testing and vaccination data.

Both the Scripps and Stanford platforms are part of a global technologic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospective studies, led by device manufacturers and academic institutions, allow individuals to voluntarily share sensor and clinical data to address the crisis. Similar approaches have been used to track COVID-19 in large populations in Germany via the Corona Data Donation app.

The study by Dr. Quer and colleagues was funded by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported grants from Janssen and personal fees from Otsuka and Livongo outside of the submitted work. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Snyder has ties to Personalis, Qbio, January, SensOmics, Protos, Mirvie, and Oralome.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A smartphone app that combines passively collected physiologic data from wearable devices, such as fitness trackers, and self-reported symptoms can discriminate between COVID-19–positive and –negative individuals among those who report symptoms, new data suggest.

After analyzing data from more than 30,000 participants, researchers from the Digital Engagement and Tracking for Early Control and Treatment (DETECT) study concluded that adding individual changes in sensor data improves models based on symptoms alone for differentiating symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 positive and symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 negative.

The combination can potentially identify infection clusters before wider community spread occurs, Giorgio Quer, PhD, and colleagues report in an article published online Oct. 29 in Nature Medicine. DETECT investigators note that marrying participant-reported symptoms with personal sensor data, such as deviation from normal sleep duration and resting heart rate, resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.73-0.86) for differentiating between symptomatic individuals who were positive and those who were negative for COVID-19.

“By better characterizing each individual’s unique baseline, you can then identify changes that may indicate that someone has a viral illness,” said Dr. Quer, director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. “In previous research, we found that the proportion of individuals with elevated resting heart rate and sleep duration compared with their normal could significantly improve real-time detection of influenza-like illness rates at the state level,” he said in an interview.

Thus, continuous passively captured data may be a useful adjunct to bricks-and-mortar site testing, which is generally a one-off or infrequent sampling assay and is not always easily accessible, he added. Furthermore, traditional screening with temperature and symptom reporting is inadequate. An elevation in temperature is not as common as frequently believed for people who test positive for COVID-19, Dr. Quer continued. “Early identification via sensor variables of those who are presymptomatic or even asymptomatic would be especially valuable, as people may potentially be infectious during this period, and early detection is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Quer said.

According to his group, adding these physiologic changes from baseline values significantly outperformed detection (P < .01) using a British model described in an earlier study by by Cristina Menni, PhD, and associates. That method, in which symptoms were considered alone, yielded an AUC of 0.71 (IQR, 0.63-0.79).

According to Dr. Quer, one in five Americans currently wear an electronic device. “If we could enroll even a small percentage of these individuals, we’d be able to potentially identify clusters before they have the opportunity to spread,” he said.

DETECT study details

During the period March 15 to June 7, 2020, the study enrolled 30,529 participants from all 50 states. They ranged in age from younger than 35 years (23.1%) to older than 65 years (12.8%); the majority (63.5%) were aged 35-65 years, and 62% were women. Sensor devices in use by the cohort included Fitbit activity trackers (78.4%) and Apple HealthKit (31.2%).

Participants downloaded an app called MyDataHelps, which collects smartwatch and activity tracker information, including self-reported symptoms and diagnostic testing results. The app also monitors changes from baseline in resting heart rate, sleep duration, and physical activity, as measured by steps.

Overall, 3,811 participants reported having at least one symptom of some kind (e.g., fatigue, cough, dyspnea, loss of taste or smell). Of these, 54 reported testing positive for COVID-19, and 279 reported testing negative.

Sleep and activity were significantly different for the positive and negative groups, with an AUC of 0.68 (IQR, 0.57-0.79) for the sleep metric and 0.69 (IQR, 0.61-0.77) for the activity metric, suggesting that these parameters were more affected in COVID-19–positive participants.

When the investigators combined resting heart rate, sleep, and activity into a single metric, predictive performance improved to an AUC of 0.72 (IQR, 0.64-0.80).

The next step, Dr. Quer said, is to include an alert to notify users of possible infection.

Alerting users to possible COVID-19 infection

In a similar study, an alert feature was already incorporated. The study, led by Michael P. Snyder, PhD, director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, will soon be published online in Nature Biomedical Engineering. In that study, presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 was achieved in more than 80% of participants using resting heart rate.

“The median is 4 days prior to symptom formation,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We have an alarm system to notify people when their heart rate is elevated. So a positive signal from a smartwatch can be used to follow up by polymerase chain reaction [testing].”

Dr. Snyder said these approaches offer a roadmap to containing widespread infections. “Public health authorities need to be open to these technologies and begin incorporating them into their tracking,” he said. “Right now, people do temperature checks, which are of limited value. Resting heart rate is much better information.”

Although the DETECT researchers have not yet received feedback on their results, they believe public health authorities could recommend the use of such apps. “These are devices that people routinely wear for tracking their fitness and sleep, so it would be relatively easy to use the data for viral illness tracking,” said co–lead author Jennifer Radin, PhD, an epidemiologist at Scripps. “Testing resources are still limited and don’t allow for routine serial testing of individuals who may be asymptomatic or presymptomatic. Wearables can offer a different way to routinely monitor and screen people for changes in their data that may indicate COVID-19.”

The marshaling of data through consumer digital platforms to fight the coronavirus is gaining ground. New York State and New Jersey are already embracing smartphone apps to alert individuals to possible exposure to the virus.

More than 710,000 New Yorkers have downloaded the COVID NY Alert app, launched in October to help protect individuals and communities from COVID-19 by sending alerts without compromising privacy or personal information. “Upon receiving a notification about a potential exposure, users are then able to self-quarantine, get tested, and reduce the potential exposure risk to family, friends, coworkers, and others,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health, said in an interview.

And recently the Mayo Clinic and Safe Health Systems launched a platform to store COVID-19 testing and vaccination data.

Both the Scripps and Stanford platforms are part of a global technologic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospective studies, led by device manufacturers and academic institutions, allow individuals to voluntarily share sensor and clinical data to address the crisis. Similar approaches have been used to track COVID-19 in large populations in Germany via the Corona Data Donation app.

The study by Dr. Quer and colleagues was funded by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported grants from Janssen and personal fees from Otsuka and Livongo outside of the submitted work. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Snyder has ties to Personalis, Qbio, January, SensOmics, Protos, Mirvie, and Oralome.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A smartphone app that combines passively collected physiologic data from wearable devices, such as fitness trackers, and self-reported symptoms can discriminate between COVID-19–positive and –negative individuals among those who report symptoms, new data suggest.

After analyzing data from more than 30,000 participants, researchers from the Digital Engagement and Tracking for Early Control and Treatment (DETECT) study concluded that adding individual changes in sensor data improves models based on symptoms alone for differentiating symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 positive and symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 negative.

The combination can potentially identify infection clusters before wider community spread occurs, Giorgio Quer, PhD, and colleagues report in an article published online Oct. 29 in Nature Medicine. DETECT investigators note that marrying participant-reported symptoms with personal sensor data, such as deviation from normal sleep duration and resting heart rate, resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.73-0.86) for differentiating between symptomatic individuals who were positive and those who were negative for COVID-19.

“By better characterizing each individual’s unique baseline, you can then identify changes that may indicate that someone has a viral illness,” said Dr. Quer, director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. “In previous research, we found that the proportion of individuals with elevated resting heart rate and sleep duration compared with their normal could significantly improve real-time detection of influenza-like illness rates at the state level,” he said in an interview.

Thus, continuous passively captured data may be a useful adjunct to bricks-and-mortar site testing, which is generally a one-off or infrequent sampling assay and is not always easily accessible, he added. Furthermore, traditional screening with temperature and symptom reporting is inadequate. An elevation in temperature is not as common as frequently believed for people who test positive for COVID-19, Dr. Quer continued. “Early identification via sensor variables of those who are presymptomatic or even asymptomatic would be especially valuable, as people may potentially be infectious during this period, and early detection is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Quer said.

According to his group, adding these physiologic changes from baseline values significantly outperformed detection (P < .01) using a British model described in an earlier study by by Cristina Menni, PhD, and associates. That method, in which symptoms were considered alone, yielded an AUC of 0.71 (IQR, 0.63-0.79).

According to Dr. Quer, one in five Americans currently wear an electronic device. “If we could enroll even a small percentage of these individuals, we’d be able to potentially identify clusters before they have the opportunity to spread,” he said.

DETECT study details

During the period March 15 to June 7, 2020, the study enrolled 30,529 participants from all 50 states. They ranged in age from younger than 35 years (23.1%) to older than 65 years (12.8%); the majority (63.5%) were aged 35-65 years, and 62% were women. Sensor devices in use by the cohort included Fitbit activity trackers (78.4%) and Apple HealthKit (31.2%).

Participants downloaded an app called MyDataHelps, which collects smartwatch and activity tracker information, including self-reported symptoms and diagnostic testing results. The app also monitors changes from baseline in resting heart rate, sleep duration, and physical activity, as measured by steps.

Overall, 3,811 participants reported having at least one symptom of some kind (e.g., fatigue, cough, dyspnea, loss of taste or smell). Of these, 54 reported testing positive for COVID-19, and 279 reported testing negative.

Sleep and activity were significantly different for the positive and negative groups, with an AUC of 0.68 (IQR, 0.57-0.79) for the sleep metric and 0.69 (IQR, 0.61-0.77) for the activity metric, suggesting that these parameters were more affected in COVID-19–positive participants.

When the investigators combined resting heart rate, sleep, and activity into a single metric, predictive performance improved to an AUC of 0.72 (IQR, 0.64-0.80).

The next step, Dr. Quer said, is to include an alert to notify users of possible infection.

Alerting users to possible COVID-19 infection

In a similar study, an alert feature was already incorporated. The study, led by Michael P. Snyder, PhD, director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, will soon be published online in Nature Biomedical Engineering. In that study, presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 was achieved in more than 80% of participants using resting heart rate.

“The median is 4 days prior to symptom formation,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We have an alarm system to notify people when their heart rate is elevated. So a positive signal from a smartwatch can be used to follow up by polymerase chain reaction [testing].”

Dr. Snyder said these approaches offer a roadmap to containing widespread infections. “Public health authorities need to be open to these technologies and begin incorporating them into their tracking,” he said. “Right now, people do temperature checks, which are of limited value. Resting heart rate is much better information.”

Although the DETECT researchers have not yet received feedback on their results, they believe public health authorities could recommend the use of such apps. “These are devices that people routinely wear for tracking their fitness and sleep, so it would be relatively easy to use the data for viral illness tracking,” said co–lead author Jennifer Radin, PhD, an epidemiologist at Scripps. “Testing resources are still limited and don’t allow for routine serial testing of individuals who may be asymptomatic or presymptomatic. Wearables can offer a different way to routinely monitor and screen people for changes in their data that may indicate COVID-19.”

The marshaling of data through consumer digital platforms to fight the coronavirus is gaining ground. New York State and New Jersey are already embracing smartphone apps to alert individuals to possible exposure to the virus.

More than 710,000 New Yorkers have downloaded the COVID NY Alert app, launched in October to help protect individuals and communities from COVID-19 by sending alerts without compromising privacy or personal information. “Upon receiving a notification about a potential exposure, users are then able to self-quarantine, get tested, and reduce the potential exposure risk to family, friends, coworkers, and others,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health, said in an interview.

And recently the Mayo Clinic and Safe Health Systems launched a platform to store COVID-19 testing and vaccination data.

Both the Scripps and Stanford platforms are part of a global technologic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospective studies, led by device manufacturers and academic institutions, allow individuals to voluntarily share sensor and clinical data to address the crisis. Similar approaches have been used to track COVID-19 in large populations in Germany via the Corona Data Donation app.

The study by Dr. Quer and colleagues was funded by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported grants from Janssen and personal fees from Otsuka and Livongo outside of the submitted work. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Snyder has ties to Personalis, Qbio, January, SensOmics, Protos, Mirvie, and Oralome.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Lemborexant for insomnia

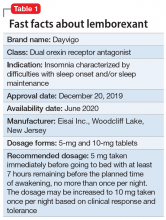

Lemborexant, FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia, has demonstrated efficacy in improving both sleep onset and sleep maintenance.1 This novel compound is now the second approved insomnia medication classed as a dual orexin receptor antagonist (Table 1). This targeted mechanism of action aims to enhance sleep while limiting the adverse effects associated with traditional hypnotics.

Clinical implications

Insomnia symptoms affect approximately one-third of the general population at least occasionally. Approximately 10% of individuals meet DSM-5 criteria for insomnia disorder, which require nighttime sleep difficulty and daytime consequences persisting for a minimum of 3 months.2 The prevalence is considerably higher in patients with chronic medical disorders and comorbid psychiatric conditions, especially mood, anxiety, substance use, and stress- and trauma-related disorders. Clinical guidelines for treating insomnia disorder typically recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia as a first choice and FDA-approved insomnia medications as secondary options.3

Currently approved insomnia medications fall into 4 distinct pharmacodynamics categories.4 Benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics include 5 medications with classic benzodiazepine structures (estazolam, flurazepam, quazepam, temazepam, and triazolam) and 3 compounds (eszopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem) with alternate structures but similar mechanisms of action. There is 1 melatonin receptor agonist (ramelteon) and 1 histamine receptor antagonist (low-dose doxepin). Joining suvorexant (approved in 2014), lemborexant is the second dual orexin receptor antagonist.

The orexin (also called hypocretin) system was first described in 1998 and its fundamental role in promoting and coordinating wakefulness was quickly established.5 A relatively small number of hypothalamic neurons located in the lateral and perifornical regions produce 2 similar orexin neuropeptides (orexin A and orexin B) with widespread distributions, notably reinforcing the wake-promoting activity of histamine, acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Consistent with the typical sleep-wake cycle, orexin release is limited during the nighttime. The orexin neuropeptides interact with 2 G-protein-coupled orexin receptors (OX1R, OX2R).

Animal studies showed that impairment in orexin system activity was associated with symptoms characteristic of narcolepsy, including cataplexy and excessive sleep episodes. Soon after, it was found that humans diagnosed with narcolepsy with cataplexy had markedly low CSF orexin levels.6 This recognition that excessively sleepy people with narcolepsy had a profound decrease in orexin production led to the hypothesis that pharmacologically decreasing orexin activity might be sleep-enhancing for insomnia patients, who presumably are excessively aroused. Numerous compounds soon were evaluated for their potential as orexin receptor antagonists. The efficacy of treating insomnia with a dual orexin receptor antagonist in humans was first reported in 2007 with almorexant, a compound that remains investigational.7 Research continues to investigate both single and dual orexin antagonist molecules for insomnia and other potential indications.

How it works

Unlike most hypnotics, which have widespread CNS depressant effects, lemborexant has a more targeted action in promoting sleep by suppressing the wake drive supported by the orexin system.8 Lemborexant is highly selective for the OX1R and OX2R orexin receptors, where it functions as a competitive antagonist. It is hypothesized that by modulating orexin activity with a receptor antagonist, excessive arousal associated with insomnia can be reduced, thus improving nighttime sleep. The pharmacokinetic properties allow benefits for both sleep onset and maintenance.

Pharmacokinetics

Lemborexant is available in immediate-release tablets with a peak concentration time (Tmax) of approximately 1 to 3 hours after ingestion. When taken after a high-fat and high-calorie meal, there is a delay in the Tmax, a decrease in the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), and an increase in the concentration area under the curve (AUC0-inf).1

Continue to: Metabolism is primarily through...

Metabolism is primarily through the cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 pathway, and to a lesser extent through CYP3A5. Concomitant use with moderate or strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers should be avoided, while use with weak CYP3A inhibitors should be limited to the 5-mg dose of lemborexant.

Lemborexant has the potential to induce the metabolism of CYP2B6 substrates, such as bupropion and methadone, possibly leading to reduced efficacy for these medications. Accordingly, the clinical responses to any CYP2B6 substrates should be monitored and dosage adjustments considered.

Concomitant use of lemborexant with alcohol should be avoided because there may be increased impairment in postural stability and memory, in part due to increases in the medication’s Cmax and AUC, as well as the direct effects of alcohol.

Efficacy

In randomized, placebo-controlled trials, lemborexant demonstrated both objective and subjective evidence of clinically significant benefits for sleep onset and sleep maintenance in patients diagnosed with insomnia disorder.1 The 2 pivotal efficacy studies were:

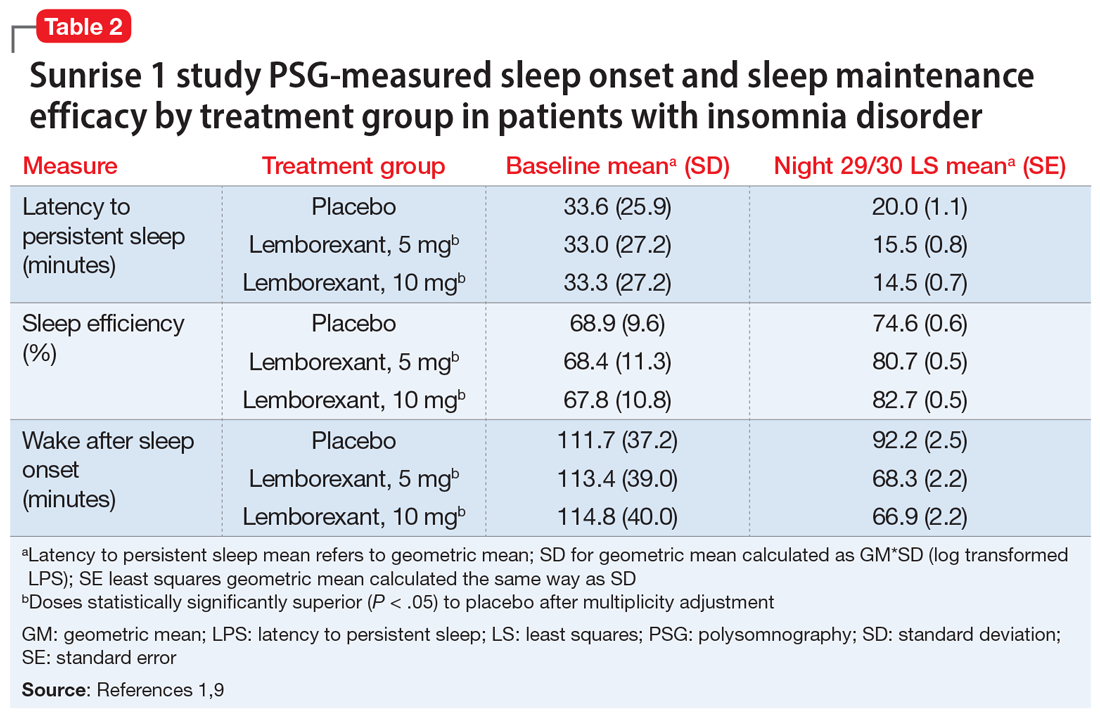

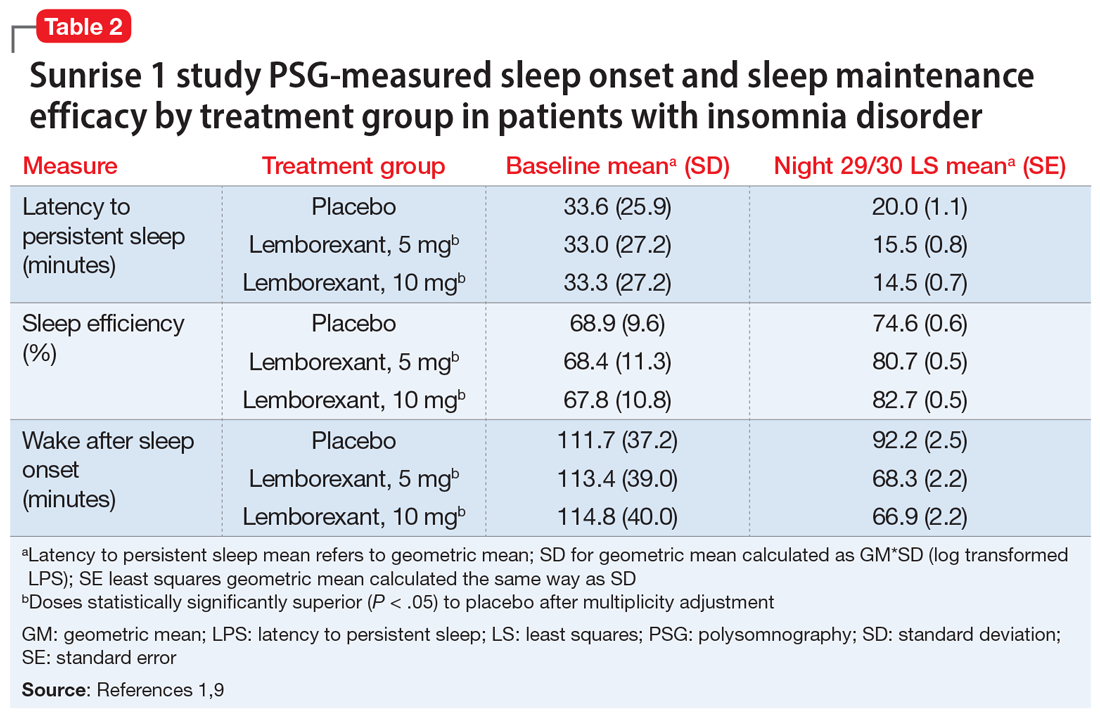

- Sunrise 1, a 4-week trial with older adults that included laboratory polysomnography (PSG) studies (objective) and patient-reported sleep measures (subjective) on selected nights9

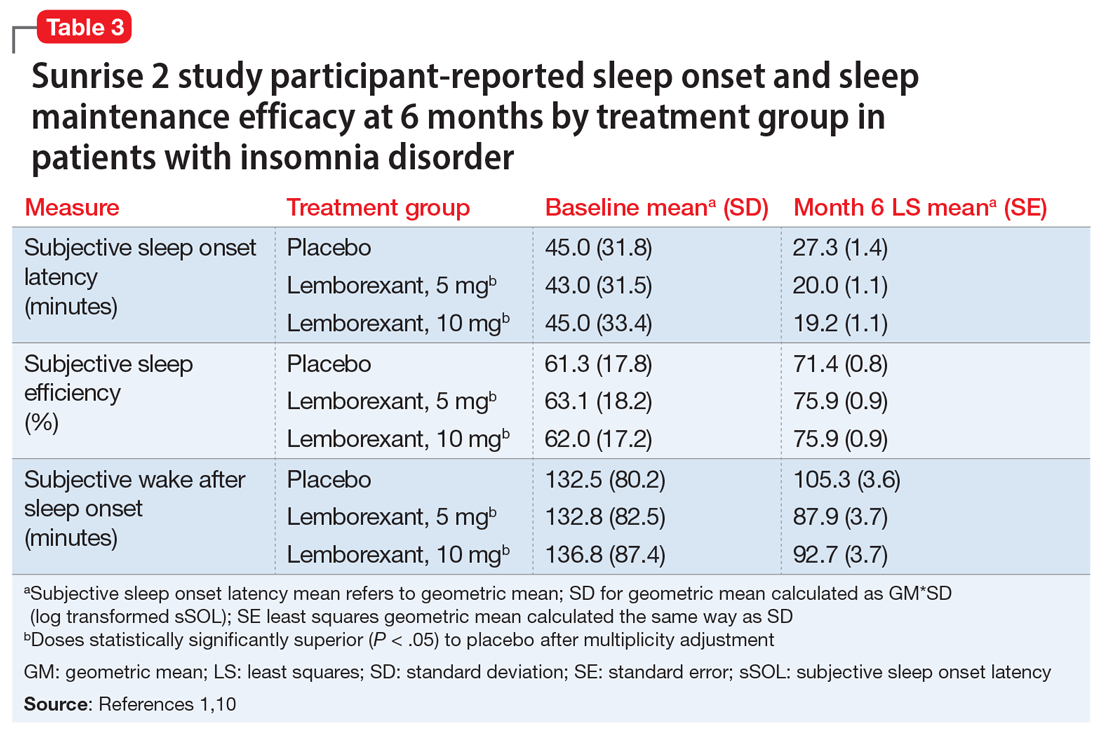

- Sunrise 2, a 6-month trial assessing patient-reported sleep characteristics in adults and older adults.10

Sunrise 1 was performed with older adults with insomnia who were randomized to groups with nightly use of lemborexant, 5 mg (n = 266), lemborexant, 10 mg (n = 269), zolpidem extended-release, 6.25 mg, as an active comparator (n = 263), or placebo (n = 208).9 The age range was 55 to 88 years with a median age of 63 years. Most patients (86.4%) were women. Because this study focused on the assessment of efficacy for treating sleep maintenance difficulty, the inclusion criteria required a subjective report of experiencing a wake time after sleep onset (sWASO) of at least 60 minutes for 3 or more nights per week over the previous 4 weeks. The zolpidem extended-release 6.25 mg comparison was chosen because it has an indication for sleep maintenance insomnia with this recommended dose for older adults.

Continue to: Laboratory PSG monitoring...

Laboratory PSG monitoring was performed for 2 consecutive nights at baseline (before treatment), the first 2 treatment nights, and the final 2 treatment nights (Nights 29 and 30). The primary study endpoint was the change in latency to persistent sleep (LPS) from baseline to the final 2 nights for the lemborexant doses compared with placebo. Additional PSG-based endpoints were similar comparisons for sleep efficiency (percent time asleep during the 8-hour laboratory recording period) and objective wake after sleep onset (WASO) compared with placebo, and WASO during the second half of the night (WASO2H) compared with zolpidem. Patients completed Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) questionnaires at baseline and the end of the treatment to compare disease severity. Subjective assessments were done daily with electronic diary entries that included sleep onset latency (sSOL), sWASO, and subjective sleep efficiency.

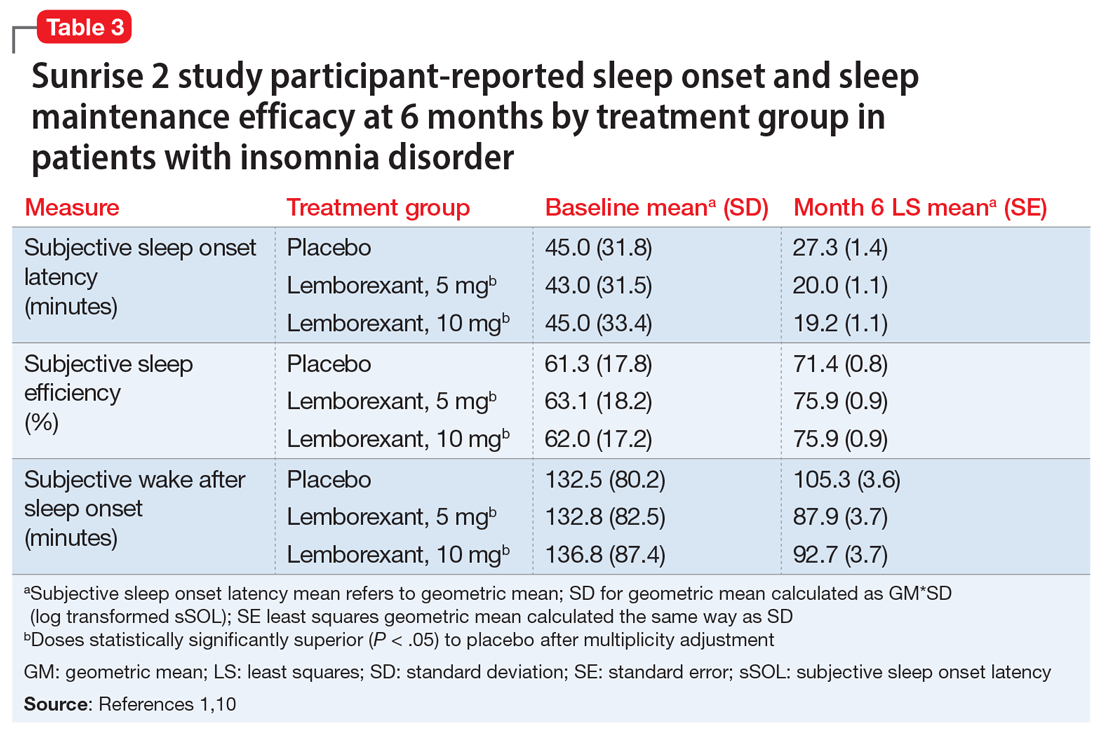

In comparison with placebo, both lemborexant doses were associated with significantly improved PSG measures of LPS, WASO, and sleep efficiency during nights 1 and 2 that were maintained through Nights 29 and 30 (Table 21,9). The lemborexant doses also demonstrated significant improvements in WASO2H compared with zolpidem and placebo on the first 2 and final 2 treatment nights. Analyses of the subjective assessments (sSOL, sWASO, and sleep efficiency) compared the baseline with means for the first and the last treatment weeks. At both lemborexant doses, the sSOL was significantly reduced during the first and last weeks compared with placebo and zolpidem. Subjective sleep efficiency was significantly improved at both time points for the lemborexant doses, though these were not significantly different from the zolpidem values. The sWASO values were significantly decreased for both lemborexant doses at both time points compared with placebo. During the first treatment week, both lemborexant doses did not differ significantly from zolpidem in the sWASO change from baseline; however, at the final treatment week, the zolpidem value was significantly improved compared with lemborexant, 5 mg, but not significantly different from lemborexant, 10 mg. The ISI change from baseline to the end of the treatment period showed significant improvement for the lemborexant doses and zolpidem extended-release compared with placebo.

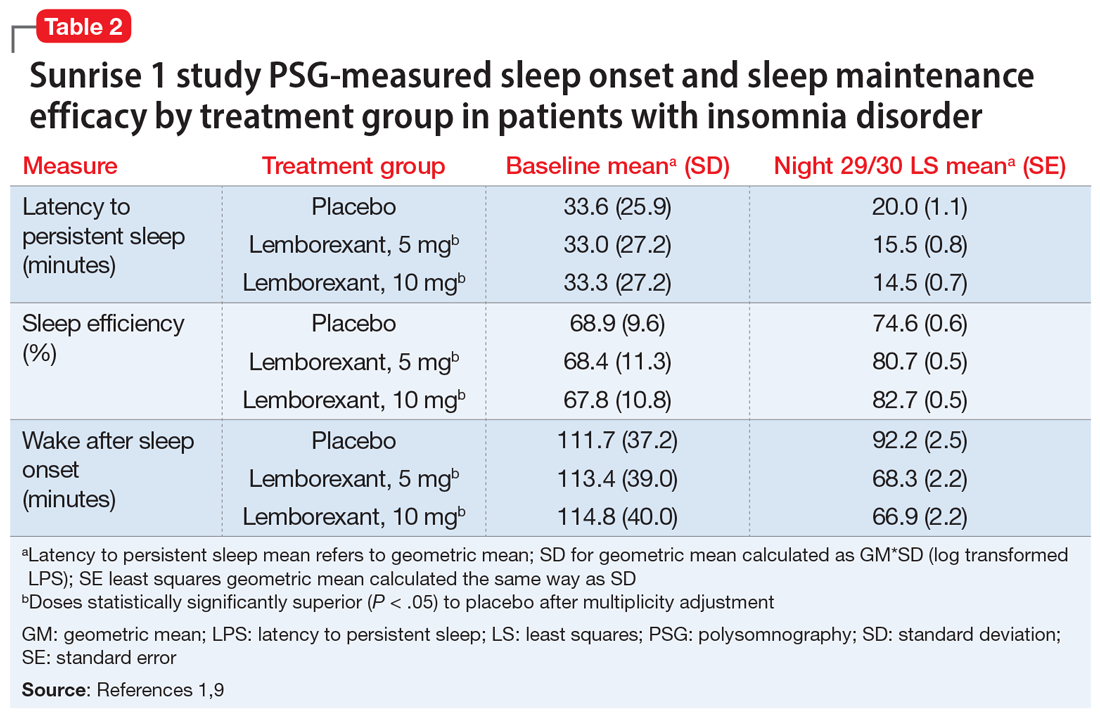

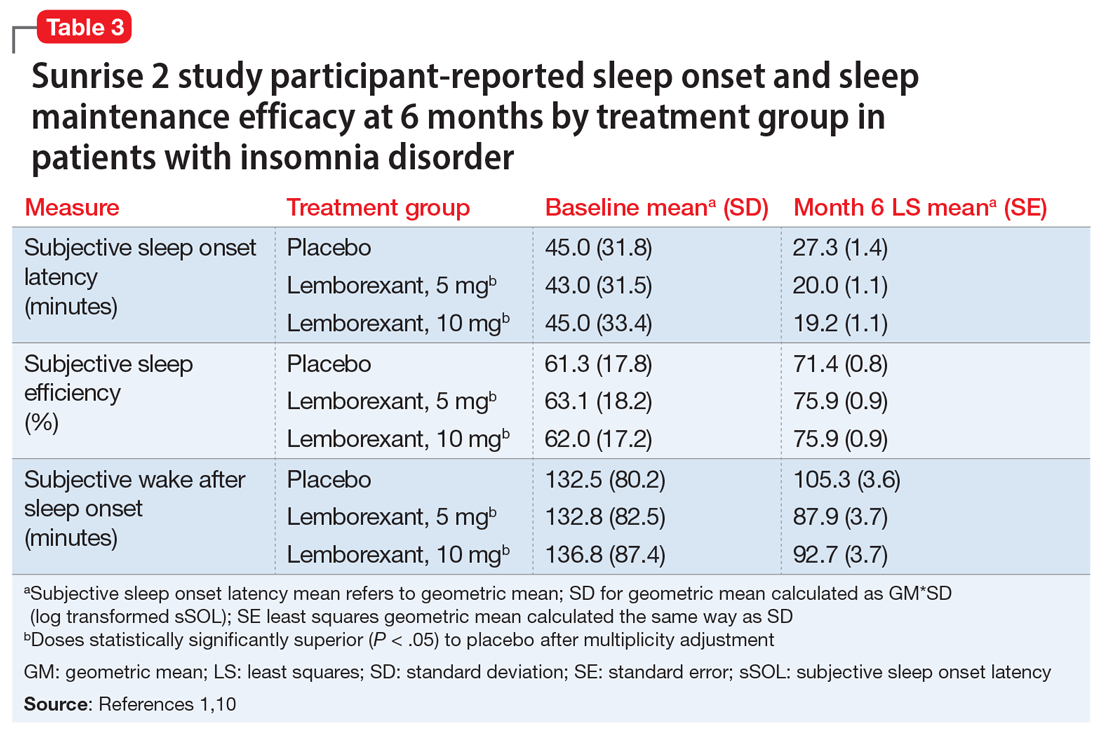

In the Sunrise 2 study, patients who met the criteria for insomnia disorder (age range 18 to 88, mean 55; 68% female) were randomized to groups taking nightly doses of lemborexant, 5 mg (n = 323), lemborexant, 10 mg (n = 323), or placebo (n = 325) for 6 months.10 Inclusion criteria required an sSOL of at least 30 minutes and/or a sWASO of at least 60 minutes 3 times a week or more during the previous 4 weeks. Efficacy was assessed with daily electronic diary entries, with analyses of change from baseline for sSOL (primary endpoint, baseline to end of 6-month study period), sWASO, and patient-reported sleep efficiency (sSEF). Subjective total sleep time (sTST) represented the estimated time asleep during the time in bed. Additional diary assessments related to sleep quality and morning alertness. All of these subjective assessments were compared as 7-day means for the first week of treatment and the last week of each treatment month.

The superiority of lemborexant, 5 mg and 10 mg, compared with placebo was demonstrated by significant improvements in sSOL, sSEF, sWASO, and sTST during the initial week of the treatment period that remained significant at the end of the 6-month placebo-controlled period (Table 31,10). At the end of 6 months, there were significantly more sleep-onset responders and sleep-maintenance responders among patients taking lemborexant compared with those taking placebo. Sleep-onset responders were patients with a baseline sSOL >30 minutes and a mean sSOL ≤20 minutes at the end of the study. Sleep-maintenance responders were participants with a baseline sWASO >60 minutes who at the end of the study had a mean sWASO ≤60 minutes that included a reduction of at least 10 minutes.

Following the 6-month placebo-controlled treatment period, the Sunrise 2 study continued for an additional 6 months of nightly active treatment for continued safety and efficacy assessment. Patients assigned to lemborexant, 5 mg or 10 mg, during the initial period continued on those doses. Those in the placebo group were randomized to either of the 2 lemborexant doses.

Continue to: Safety studies and adverse reactions

Safety studies and adverse reactions

Potential medication effects on middle-of-the-night and next-morning postural stability (body sway measured with an ataxiameter) and cognitive performance, as well as middle-of-the-night auditory awakening threshold, were assessed in a randomized, 4-way crossover study of 56 healthy older adults (women age ≥55 [77.8%], men age ≥65) given a single bedtime dose of placebo, lemborexant, 5 mg, lemborexant, 10 mg, and zolpidem extended-release, 6.25 mg, on separate nights.11 The results were compared with data from a baseline night with the same measures performed prior to the randomization. The middle-of-the-night assessments were done approximately 4 hours after the dose and the next-morning measures were done after 8 hours in bed. The auditory threshold analysis showed no significant differences among the 4 study nights. Compared with placebo, the middle-of-the-night postural stability was significantly worse for both lemborexant doses and zolpidem; however, the zolpidem effect was significantly worse than with either lemborexant dose. The next-morning postural stability measures showed no significant difference from placebo for the lemborexant doses, but zolpidem continued to show a significantly worsened result. The cognitive performance assessment battery provided 4 domain factor scores (power of attention, continuity of attention, quality of memory, and speed of memory retrieval). The middle-of-the-night battery showed no significant difference between lemborexant, 5 mg, and placebo in any domain, while both lemborexant, 10 mg, and zolpidem showed worse performance on some of the attention and/or memory tests. The next-morning cognitive assessment revealed no significant differences from placebo for the treatments.

Respiratory safety was examined in a placebo-controlled, 2-period crossover study of 38 patients diagnosed with mild obstructive sleep apnea who received lemborexant, 10 mg, or placebo nightly during each 8-day period.12 Neither the apnea-hypopnea index nor the mean oxygen saturation during the lemborexant nights were significantly different from the placebo nights.