User login

Brentuximab vedotin beat methotrexate, bexarotene in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

SAN DIEGO – For patients with CD30 expressing cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, antibody-drug conjugate therapy with brentuximab vedotin significantly outperformed two standard regimens in the phase III ALCANZA trial.

After a median of 17.5 months of follow-up, 56% of patients receiving brentuximab vedotin had an objective response lasting at least 4 months, versus 13% of patients treated with physician’s choice of methotrexate or bexarotene (P less than .0001), Youn H. Kim, MD, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

As in past studies, brentuximab vedotin caused high rates of peripheral neuropathy, but more than 80% of cases improved or resolved over time, she said.

This is the first reported phase III trial to convincingly show that a new systemic agent outperformed standard therapies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), which tend to have inadequate and short-lived efficacy, stated Dr. Kim, of Stanford (Calif.) University. Brentuximab vedotin not only met the primary endpoint, but all other predefined endpoints, including progression-free survival and a quality-of-life measure, she said.

“These compelling results have potential practice-changing implications,” she concluded.

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) targets CD30, which is expressed in skin lesions of about half of patients with CTCL. A protease-cleavable linker attaches an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody to monomethyl auristatin E, which disrupts microtubules when released into CD30-positive tumor cells (Blood. 2013;122:367). The agent showed clinical activity against CTCL in two previous phase II trials of CTCL.

Accordingly, the international, open-label phase III ALCANZA study enrolled 128 treatment-experienced patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides or primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Patients were randomly assigned to receive brentuximab vedotin (1.8 mg/kg once every 3 weeks) or physician’s choice of either methotrexate (5 to 50 mg once weekly) or bexarotene (300 mg/m2 once daily) for up to 16 3-week cycles, or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Methotrexate or bexarotene were designated “physician’s choice” because they are used worldwide for treating CTCL, according to Dr. Kim.

To capture both the rate and duration of response, researchers defined objective response lasting at least 4 months as the primary endpoint. Brentuximab vedotin more than quadrupled the likelihood of this outcome when compared with the standard CTCL regimens, a trend that spanned key demographic and clinical subgroups, Dr. Kim said.

“All endpoints were highly [statistically] significant,” she further reported. For example, the objective response rate with brentuximab vedotin was 67%, versus 20% for methotrexate or bexarotene. Respective rates of complete response were 16% and 2%, and median durations of progression-free survival were 17 and 4 months, translating to a 73% lower risk of progression or death with brentuximab vedotin (95% confidence interval, 57%-83%). Patients who received brentuximab vedotin also reported about a three-fold greater improvement on the Skindex-29 symptom domain, compared with the physician’s choice group (–29 vs. –9 points; P less than .0001).

The safety profile of brentuximab vedotin resembled that seen in previous studies, Dr. Kim said. Most notably, 67% of patients developed peripheral neuropathy, and 9% developed grade 3 peripheral neuropathy. This usually improved or resolved over about the next 22 months. Diarrhea, fatigue, and vomiting affected about a third of patients on brentuximab vedotin, and about one in four stopped treatment because of adverse events, compared with 8% of the physician’s choice arm. Rates of serious adverse events were 41% and 47%, respectively. One brentuximab vedotin recipient died of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome that investigators attributed to treatment-associated necrosis of peripheral tumors. They identified no other treatment-related deaths.

Seattle Genetics and Takeda funded the trial. Dr. Kim disclosed ties to Takeda and Seattle Genetics, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – For patients with CD30 expressing cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, antibody-drug conjugate therapy with brentuximab vedotin significantly outperformed two standard regimens in the phase III ALCANZA trial.

After a median of 17.5 months of follow-up, 56% of patients receiving brentuximab vedotin had an objective response lasting at least 4 months, versus 13% of patients treated with physician’s choice of methotrexate or bexarotene (P less than .0001), Youn H. Kim, MD, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

As in past studies, brentuximab vedotin caused high rates of peripheral neuropathy, but more than 80% of cases improved or resolved over time, she said.

This is the first reported phase III trial to convincingly show that a new systemic agent outperformed standard therapies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), which tend to have inadequate and short-lived efficacy, stated Dr. Kim, of Stanford (Calif.) University. Brentuximab vedotin not only met the primary endpoint, but all other predefined endpoints, including progression-free survival and a quality-of-life measure, she said.

“These compelling results have potential practice-changing implications,” she concluded.

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) targets CD30, which is expressed in skin lesions of about half of patients with CTCL. A protease-cleavable linker attaches an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody to monomethyl auristatin E, which disrupts microtubules when released into CD30-positive tumor cells (Blood. 2013;122:367). The agent showed clinical activity against CTCL in two previous phase II trials of CTCL.

Accordingly, the international, open-label phase III ALCANZA study enrolled 128 treatment-experienced patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides or primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Patients were randomly assigned to receive brentuximab vedotin (1.8 mg/kg once every 3 weeks) or physician’s choice of either methotrexate (5 to 50 mg once weekly) or bexarotene (300 mg/m2 once daily) for up to 16 3-week cycles, or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Methotrexate or bexarotene were designated “physician’s choice” because they are used worldwide for treating CTCL, according to Dr. Kim.

To capture both the rate and duration of response, researchers defined objective response lasting at least 4 months as the primary endpoint. Brentuximab vedotin more than quadrupled the likelihood of this outcome when compared with the standard CTCL regimens, a trend that spanned key demographic and clinical subgroups, Dr. Kim said.

“All endpoints were highly [statistically] significant,” she further reported. For example, the objective response rate with brentuximab vedotin was 67%, versus 20% for methotrexate or bexarotene. Respective rates of complete response were 16% and 2%, and median durations of progression-free survival were 17 and 4 months, translating to a 73% lower risk of progression or death with brentuximab vedotin (95% confidence interval, 57%-83%). Patients who received brentuximab vedotin also reported about a three-fold greater improvement on the Skindex-29 symptom domain, compared with the physician’s choice group (–29 vs. –9 points; P less than .0001).

The safety profile of brentuximab vedotin resembled that seen in previous studies, Dr. Kim said. Most notably, 67% of patients developed peripheral neuropathy, and 9% developed grade 3 peripheral neuropathy. This usually improved or resolved over about the next 22 months. Diarrhea, fatigue, and vomiting affected about a third of patients on brentuximab vedotin, and about one in four stopped treatment because of adverse events, compared with 8% of the physician’s choice arm. Rates of serious adverse events were 41% and 47%, respectively. One brentuximab vedotin recipient died of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome that investigators attributed to treatment-associated necrosis of peripheral tumors. They identified no other treatment-related deaths.

Seattle Genetics and Takeda funded the trial. Dr. Kim disclosed ties to Takeda and Seattle Genetics, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – For patients with CD30 expressing cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, antibody-drug conjugate therapy with brentuximab vedotin significantly outperformed two standard regimens in the phase III ALCANZA trial.

After a median of 17.5 months of follow-up, 56% of patients receiving brentuximab vedotin had an objective response lasting at least 4 months, versus 13% of patients treated with physician’s choice of methotrexate or bexarotene (P less than .0001), Youn H. Kim, MD, said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

As in past studies, brentuximab vedotin caused high rates of peripheral neuropathy, but more than 80% of cases improved or resolved over time, she said.

This is the first reported phase III trial to convincingly show that a new systemic agent outperformed standard therapies for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), which tend to have inadequate and short-lived efficacy, stated Dr. Kim, of Stanford (Calif.) University. Brentuximab vedotin not only met the primary endpoint, but all other predefined endpoints, including progression-free survival and a quality-of-life measure, she said.

“These compelling results have potential practice-changing implications,” she concluded.

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) targets CD30, which is expressed in skin lesions of about half of patients with CTCL. A protease-cleavable linker attaches an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody to monomethyl auristatin E, which disrupts microtubules when released into CD30-positive tumor cells (Blood. 2013;122:367). The agent showed clinical activity against CTCL in two previous phase II trials of CTCL.

Accordingly, the international, open-label phase III ALCANZA study enrolled 128 treatment-experienced patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides or primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Patients were randomly assigned to receive brentuximab vedotin (1.8 mg/kg once every 3 weeks) or physician’s choice of either methotrexate (5 to 50 mg once weekly) or bexarotene (300 mg/m2 once daily) for up to 16 3-week cycles, or until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. Methotrexate or bexarotene were designated “physician’s choice” because they are used worldwide for treating CTCL, according to Dr. Kim.

To capture both the rate and duration of response, researchers defined objective response lasting at least 4 months as the primary endpoint. Brentuximab vedotin more than quadrupled the likelihood of this outcome when compared with the standard CTCL regimens, a trend that spanned key demographic and clinical subgroups, Dr. Kim said.

“All endpoints were highly [statistically] significant,” she further reported. For example, the objective response rate with brentuximab vedotin was 67%, versus 20% for methotrexate or bexarotene. Respective rates of complete response were 16% and 2%, and median durations of progression-free survival were 17 and 4 months, translating to a 73% lower risk of progression or death with brentuximab vedotin (95% confidence interval, 57%-83%). Patients who received brentuximab vedotin also reported about a three-fold greater improvement on the Skindex-29 symptom domain, compared with the physician’s choice group (–29 vs. –9 points; P less than .0001).

The safety profile of brentuximab vedotin resembled that seen in previous studies, Dr. Kim said. Most notably, 67% of patients developed peripheral neuropathy, and 9% developed grade 3 peripheral neuropathy. This usually improved or resolved over about the next 22 months. Diarrhea, fatigue, and vomiting affected about a third of patients on brentuximab vedotin, and about one in four stopped treatment because of adverse events, compared with 8% of the physician’s choice arm. Rates of serious adverse events were 41% and 47%, respectively. One brentuximab vedotin recipient died of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome that investigators attributed to treatment-associated necrosis of peripheral tumors. They identified no other treatment-related deaths.

Seattle Genetics and Takeda funded the trial. Dr. Kim disclosed ties to Takeda and Seattle Genetics, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

AT ASH 2016

Key clinical point: Brentuximab vedotin met all its endpoints but often caused peripheral neuropathy in a phase III trial of patients with CD30 expressing cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

Major finding: After a median of 17.5 months of follow-up, 56% of patients receiving brentuximab vedotin had an objective response lasting at least 4 months, versus 13% of those receiving physician’s choice of methotrexate or bexarotene (P less than .0001).

Data source: A multicenter, open-label phase III trial of 128 patients with CD30-expressing mycosis fungoides or primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Disclosures: Seattle Genetics and Takeda funded the trial. Dr. Kim disclosed ties to Seattle Genetics and Takeda, as well as several other pharmaceutical companies.

‘Meaningful’ antitumor activity with lenalidomide monotherapy in ATL

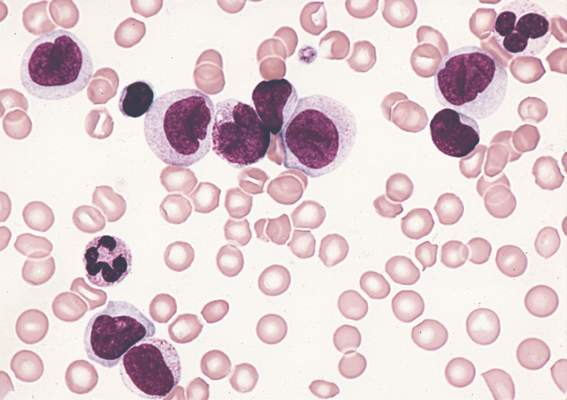

Lenalidomide monotherapy demonstrated “meaningful” antitumor activity in patients with relapsed or recurrent aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), according to new findings.

Among 26 patients enrolled in the study, 11 responses were observed, for an overall response rate of 42% (95% CI, 23%-63%). This included four complete responses and one unconfirmed complete response.

The tumor control rate was 73%, achieved in 19 patients, and the toxicity profile was manageable. Overall, these findings hint at the potential of lenalidomide to “become a treatment option in this patient population,” wrote Takashi Ishida, MD, of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Aichi, Japan, and his colleagues (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Sep 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.7732).

ATL is a difficult disease to treat, and it has a poor prognosis, as it is resistant to conventional chemotherapeutic agents and treatment options are currently limited. Lenalidomide, an oral immunomodulatory agent, has demonstrated both antiproliferative and antineoplastic activity in B-cell lymphomas in preclinical studies, and a previous phase I trial established a maximum tolerated dosage (25 mg/d) in a small cohort of Japanese patients with relapsed ATL or other peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL).

Based on these preliminary results, Dr. Ishida and his coauthors designed the current multicenter phase II study, to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide monotherapy in 26 patients with relapsed or recurrent ATL.

At a median follow-up of 3.9 months, responses were observed in 33% of patients (5 of 15) with acute disease, 57% (4 of 7) with lymphoma, and 50% (2 of 4) for unfavorable chronic ATL. Patient responses according to disease site were 31% for target (nodal and extranodal) lesions, 75% for cutaneous lesions, and 60% for peripheral blood.

The median time to relapse was 1.9 months (range, 1.8-3.7 months), while the median time to progression was 3.8 months (95% CI, 1.9 to not estimable [NE]). The median and mean duration of response for the entire cohort were NE (95% CI, 0.5 months to NE) and 5.2 months (range, 0 to 16.6 months), respectively.

Progression-free survival was 3.8 months (95% CI, 1.9 months to NE) and for overall survival, it was 20.3 months (95% CI, 9.1 months to NE).

Adverse events occurred in more than 20% of patients and the most common hematologic event was thrombocytopenia (77%). The most common nonhematologic event was increased C-reactive protein (42%), and hypoalbuminemia and hypoproteinemia were observed in about a third of patients, as were constipation, hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia (all 31%).

Dr. Ishida and several coauthors reported multiple relationships with industry, including Celgene K.K. (Tokyo), the study’s sponsor.

Lenalidomide monotherapy demonstrated “meaningful” antitumor activity in patients with relapsed or recurrent aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), according to new findings.

Among 26 patients enrolled in the study, 11 responses were observed, for an overall response rate of 42% (95% CI, 23%-63%). This included four complete responses and one unconfirmed complete response.

The tumor control rate was 73%, achieved in 19 patients, and the toxicity profile was manageable. Overall, these findings hint at the potential of lenalidomide to “become a treatment option in this patient population,” wrote Takashi Ishida, MD, of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Aichi, Japan, and his colleagues (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Sep 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.7732).

ATL is a difficult disease to treat, and it has a poor prognosis, as it is resistant to conventional chemotherapeutic agents and treatment options are currently limited. Lenalidomide, an oral immunomodulatory agent, has demonstrated both antiproliferative and antineoplastic activity in B-cell lymphomas in preclinical studies, and a previous phase I trial established a maximum tolerated dosage (25 mg/d) in a small cohort of Japanese patients with relapsed ATL or other peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL).

Based on these preliminary results, Dr. Ishida and his coauthors designed the current multicenter phase II study, to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide monotherapy in 26 patients with relapsed or recurrent ATL.

At a median follow-up of 3.9 months, responses were observed in 33% of patients (5 of 15) with acute disease, 57% (4 of 7) with lymphoma, and 50% (2 of 4) for unfavorable chronic ATL. Patient responses according to disease site were 31% for target (nodal and extranodal) lesions, 75% for cutaneous lesions, and 60% for peripheral blood.

The median time to relapse was 1.9 months (range, 1.8-3.7 months), while the median time to progression was 3.8 months (95% CI, 1.9 to not estimable [NE]). The median and mean duration of response for the entire cohort were NE (95% CI, 0.5 months to NE) and 5.2 months (range, 0 to 16.6 months), respectively.

Progression-free survival was 3.8 months (95% CI, 1.9 months to NE) and for overall survival, it was 20.3 months (95% CI, 9.1 months to NE).

Adverse events occurred in more than 20% of patients and the most common hematologic event was thrombocytopenia (77%). The most common nonhematologic event was increased C-reactive protein (42%), and hypoalbuminemia and hypoproteinemia were observed in about a third of patients, as were constipation, hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia (all 31%).

Dr. Ishida and several coauthors reported multiple relationships with industry, including Celgene K.K. (Tokyo), the study’s sponsor.

Lenalidomide monotherapy demonstrated “meaningful” antitumor activity in patients with relapsed or recurrent aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL), according to new findings.

Among 26 patients enrolled in the study, 11 responses were observed, for an overall response rate of 42% (95% CI, 23%-63%). This included four complete responses and one unconfirmed complete response.

The tumor control rate was 73%, achieved in 19 patients, and the toxicity profile was manageable. Overall, these findings hint at the potential of lenalidomide to “become a treatment option in this patient population,” wrote Takashi Ishida, MD, of Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Aichi, Japan, and his colleagues (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Sep 12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.7732).

ATL is a difficult disease to treat, and it has a poor prognosis, as it is resistant to conventional chemotherapeutic agents and treatment options are currently limited. Lenalidomide, an oral immunomodulatory agent, has demonstrated both antiproliferative and antineoplastic activity in B-cell lymphomas in preclinical studies, and a previous phase I trial established a maximum tolerated dosage (25 mg/d) in a small cohort of Japanese patients with relapsed ATL or other peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL).

Based on these preliminary results, Dr. Ishida and his coauthors designed the current multicenter phase II study, to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lenalidomide monotherapy in 26 patients with relapsed or recurrent ATL.

At a median follow-up of 3.9 months, responses were observed in 33% of patients (5 of 15) with acute disease, 57% (4 of 7) with lymphoma, and 50% (2 of 4) for unfavorable chronic ATL. Patient responses according to disease site were 31% for target (nodal and extranodal) lesions, 75% for cutaneous lesions, and 60% for peripheral blood.

The median time to relapse was 1.9 months (range, 1.8-3.7 months), while the median time to progression was 3.8 months (95% CI, 1.9 to not estimable [NE]). The median and mean duration of response for the entire cohort were NE (95% CI, 0.5 months to NE) and 5.2 months (range, 0 to 16.6 months), respectively.

Progression-free survival was 3.8 months (95% CI, 1.9 months to NE) and for overall survival, it was 20.3 months (95% CI, 9.1 months to NE).

Adverse events occurred in more than 20% of patients and the most common hematologic event was thrombocytopenia (77%). The most common nonhematologic event was increased C-reactive protein (42%), and hypoalbuminemia and hypoproteinemia were observed in about a third of patients, as were constipation, hyponatremia, and hypocalcemia (all 31%).

Dr. Ishida and several coauthors reported multiple relationships with industry, including Celgene K.K. (Tokyo), the study’s sponsor.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Lenalidomide demonstrated clinical activity with acceptable toxicity in recurrent or relapsed ATL.

Major finding: The overall response rate was 42%, and this included four complete responses and one unconfirmed complete response.

Data source: Multicenter phase II trial comprising 26 patients with relapsed or recurrent ATL.

Disclosures: Dr. Ishida and several coauthors reported multiple relationships with industry, including Celgene K.K. (Tokyo), the study’s sponsor.

Pretransplantation mogamulizumab for ATLL raises risk of GVHD

The use of mogamulizumab before allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is associated with an increased risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which leads to an inferior overall survival, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Mogamulizumab is an anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody that showed promise in small clinical studies when added to conventional chemotherapy as first-line treatment. It was recently approved for the treatment of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Japan, and eventually may be approved in the U.S. and other countries, said Shigeo Fuji, MD, of the department of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and his associates.

The agent significantly depleted regulatory T cells for several months in animal models. This prompted concern regarding the possibility of exacerbating GVHD in human patients who don’t respond completely to first-line chemotherapy and then undergo stem-cell transplantation. “However, no direct evidence has demonstrated [regulatory T-cell] depletion in humans,” the investigators noted.

To examine this issue, they assessed clinical outcomes in a cohort of 996 patients across Japan who had aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, were aged 20-69 years, were diagnosed in 2000-2013, and received intensive, multiagent chemotherapy before undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Grade 2-4 acute GVHD developed in 381 of 873 patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab (43.6%), compared with 47 of 81 patients who did receive the agent (58.0%), for a relative risk of 1.33 (P = .01). Grade 3-4 acute GVHD developed in 150 patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab (17.2%), compared with 25 who did (30.9%), for an RR of 1.80 (P less than .01) .

The agent not only raised the rate of GVHD, it also increased the severity of the disorder. GVHD was refractory to systemic corticosteroids in 23.5% of patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab, compared with 48.9% of those who did, for an RR of 2.09 (P less than .01), the investigators reported (J Clin Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8250).

In addition, 1-year disease-free mortality was 25.1% without mogamulizumab, compared with 43.7% with it. The estimated 1-year overall survival was 49.4% without mogamulizumab, compared with 32.3% with it. And in multivariable analyses, receiving mogamulizumab before undergoing stem-cell transplantation was a significant risk factor for both disease-free mortality (hazard ratio, 1.93) and overall mortality (HR, 1.67).

“All hematologists should take the risks and benefits of mogamulizumab into consideration before they use [it] in transplantation-eligible patients,” Dr. Fuji and his associates said.

The use of mogamulizumab before allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is associated with an increased risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which leads to an inferior overall survival, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Mogamulizumab is an anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody that showed promise in small clinical studies when added to conventional chemotherapy as first-line treatment. It was recently approved for the treatment of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Japan, and eventually may be approved in the U.S. and other countries, said Shigeo Fuji, MD, of the department of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and his associates.

The agent significantly depleted regulatory T cells for several months in animal models. This prompted concern regarding the possibility of exacerbating GVHD in human patients who don’t respond completely to first-line chemotherapy and then undergo stem-cell transplantation. “However, no direct evidence has demonstrated [regulatory T-cell] depletion in humans,” the investigators noted.

To examine this issue, they assessed clinical outcomes in a cohort of 996 patients across Japan who had aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, were aged 20-69 years, were diagnosed in 2000-2013, and received intensive, multiagent chemotherapy before undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Grade 2-4 acute GVHD developed in 381 of 873 patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab (43.6%), compared with 47 of 81 patients who did receive the agent (58.0%), for a relative risk of 1.33 (P = .01). Grade 3-4 acute GVHD developed in 150 patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab (17.2%), compared with 25 who did (30.9%), for an RR of 1.80 (P less than .01) .

The agent not only raised the rate of GVHD, it also increased the severity of the disorder. GVHD was refractory to systemic corticosteroids in 23.5% of patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab, compared with 48.9% of those who did, for an RR of 2.09 (P less than .01), the investigators reported (J Clin Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8250).

In addition, 1-year disease-free mortality was 25.1% without mogamulizumab, compared with 43.7% with it. The estimated 1-year overall survival was 49.4% without mogamulizumab, compared with 32.3% with it. And in multivariable analyses, receiving mogamulizumab before undergoing stem-cell transplantation was a significant risk factor for both disease-free mortality (hazard ratio, 1.93) and overall mortality (HR, 1.67).

“All hematologists should take the risks and benefits of mogamulizumab into consideration before they use [it] in transplantation-eligible patients,” Dr. Fuji and his associates said.

The use of mogamulizumab before allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma is associated with an increased risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which leads to an inferior overall survival, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Mogamulizumab is an anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody that showed promise in small clinical studies when added to conventional chemotherapy as first-line treatment. It was recently approved for the treatment of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Japan, and eventually may be approved in the U.S. and other countries, said Shigeo Fuji, MD, of the department of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, and his associates.

The agent significantly depleted regulatory T cells for several months in animal models. This prompted concern regarding the possibility of exacerbating GVHD in human patients who don’t respond completely to first-line chemotherapy and then undergo stem-cell transplantation. “However, no direct evidence has demonstrated [regulatory T-cell] depletion in humans,” the investigators noted.

To examine this issue, they assessed clinical outcomes in a cohort of 996 patients across Japan who had aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, were aged 20-69 years, were diagnosed in 2000-2013, and received intensive, multiagent chemotherapy before undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation.

Grade 2-4 acute GVHD developed in 381 of 873 patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab (43.6%), compared with 47 of 81 patients who did receive the agent (58.0%), for a relative risk of 1.33 (P = .01). Grade 3-4 acute GVHD developed in 150 patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab (17.2%), compared with 25 who did (30.9%), for an RR of 1.80 (P less than .01) .

The agent not only raised the rate of GVHD, it also increased the severity of the disorder. GVHD was refractory to systemic corticosteroids in 23.5% of patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab, compared with 48.9% of those who did, for an RR of 2.09 (P less than .01), the investigators reported (J Clin Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.8250).

In addition, 1-year disease-free mortality was 25.1% without mogamulizumab, compared with 43.7% with it. The estimated 1-year overall survival was 49.4% without mogamulizumab, compared with 32.3% with it. And in multivariable analyses, receiving mogamulizumab before undergoing stem-cell transplantation was a significant risk factor for both disease-free mortality (hazard ratio, 1.93) and overall mortality (HR, 1.67).

“All hematologists should take the risks and benefits of mogamulizumab into consideration before they use [it] in transplantation-eligible patients,” Dr. Fuji and his associates said.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: The use of mogamulizumab before allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in aggressive adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma was associated with GVHD and increased mortality.

Major finding: Grade 3-4 acute GVHD developed in 17.2% of patients who didn’t receive mogamulizumab, compared with 30.9% who did, for a relative risk of 1.80.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 996 patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma in Japan.

Disclosures: This study was supported in part by Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. Dr. Fuji and one associate reported receiving honoraria from Kyowa Hakko Kirin; another associate reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Severe psoriasis upped lymphoma risk in large cohort study

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Psoriasis of all severities was linked to a 3.5-fold increase in risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and severe psoriasis upped the associated risk of Hodgkin lymphoma by about 2.5 times, in a large, longitudinal, population-based cohort study.

Psoriasis also was tied to a smaller but statistically significant increase in the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, said Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, of the department of dermatology, the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Overall, lymphoma risk was highest in people with severe psoriasis, independent of traditional risk factors and exposure to immunosuppressive medications, Dr. Fuxench said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Psoriasis affects more than 125 million people worldwide, and severe cases are a major cause of cancer-related mortality. “Prior studies have suggested an increased risk of lymphoma in psoriasis patients, but it is unclear if this due to chronic inflammation, exposure to immunosuppressive therapies, or a combination of both factors,” Dr. Fuxench said.

To further explore these links, she and her associates analyzed electronic medical records from THIN (The Health Information Network), which includes about 12 million patients across the United Kingdom. Adults with psoriasis were matched to up to five nonpsoriatic controls based on date and clinic location. Patients who needed systemic medications or phototherapy were categorized as having severe psoriasis. The final dataset included more than 12,000 such patients, as well as 184,000 patients with mild psoriasis and more than 965,000 patients without psoriasis.

Psoriasis patients were younger and more likely to be overweight, male, and smoke and drink alcohol than patients without psoriasis, Dr. Fuxench said. Almost 80% of patients with severe disease had received systemic therapies, most often methotrexate (70% of systemic treatments) or cyclosporine (10%), while only 1% had received biologics.

Patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to be diagnosed with Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma than were patients with mild psoriasis or controls. Over a median follow-up of 5.3 years, 34 patients with severe psoriasis were diagnosed with any type of lymphoma, for an incidence of 5.2 cases per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 3.7-7.3). In contrast, incidence rates for patients with mild psoriasis and controls were 3.3 and 3.2 cases per 10,000 person-years, respectively, Dr. Fuxench said.

In the multivariable analysis, patients with psoriasis were about 18% more likely to develop any type of lymphoma than were controls, an association that reached statistical significance (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.31). Mild psoriasis increased lymphoma risk by 14%, and severe psoriasis upped it by about 83%, and both associations were statistically significant.

The increase in risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was 13% greater with mild psoriasis and 56% greater with severe disease, compared with controls, and these associations also reached statistical significance. Mild psoriasis was not linked to Hodgkin lymphoma, but patients with severe psoriasis were about 250% more likely to develop it than controls, with a trend toward statistical significance (aHR, 2.54; 95% CI, 0.94-6.87).

Finally, severe psoriasis was linked to a more than ninefold increase in risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (aHR, 9.3; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), while mild psoriasis was linked to about a threefold increase in risk.

“These results were robust in multiple sensitivity analyses, including analyses that excluded patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or a history of exposure to methotrexate, cyclosporine, or biologics,” Dr. Fuxench said. Future studies should explore the effect of treatment timing and selection on cancer risk, she added. “For those of us who care for these patients, we are increasingly using systemic agents that selectively target the immune system, and these questions will arise in clinics.”

The study’s design made it possible to pinpoint dates of diagnosis more effectively than investigators could estimate disease duration or confirm whether patients initially diagnosed with psoriasis actually had cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Dr. Fuxench noted. “Ideally, we could have another cohort study of incident psoriasis with prospective follow-up, but lymphoma is so rare that there is currently not enough power [in the THIN database] to determine associations.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Fuxench disclosed unrestricted research funding from Pfizer outside the submitted work.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Psoriasis of all severities was linked to a 3.5-fold increase in risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and severe psoriasis upped the associated risk of Hodgkin lymphoma by about 2.5 times, in a large, longitudinal, population-based cohort study.

Psoriasis also was tied to a smaller but statistically significant increase in the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, said Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, of the department of dermatology, the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Overall, lymphoma risk was highest in people with severe psoriasis, independent of traditional risk factors and exposure to immunosuppressive medications, Dr. Fuxench said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Psoriasis affects more than 125 million people worldwide, and severe cases are a major cause of cancer-related mortality. “Prior studies have suggested an increased risk of lymphoma in psoriasis patients, but it is unclear if this due to chronic inflammation, exposure to immunosuppressive therapies, or a combination of both factors,” Dr. Fuxench said.

To further explore these links, she and her associates analyzed electronic medical records from THIN (The Health Information Network), which includes about 12 million patients across the United Kingdom. Adults with psoriasis were matched to up to five nonpsoriatic controls based on date and clinic location. Patients who needed systemic medications or phototherapy were categorized as having severe psoriasis. The final dataset included more than 12,000 such patients, as well as 184,000 patients with mild psoriasis and more than 965,000 patients without psoriasis.

Psoriasis patients were younger and more likely to be overweight, male, and smoke and drink alcohol than patients without psoriasis, Dr. Fuxench said. Almost 80% of patients with severe disease had received systemic therapies, most often methotrexate (70% of systemic treatments) or cyclosporine (10%), while only 1% had received biologics.

Patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to be diagnosed with Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma than were patients with mild psoriasis or controls. Over a median follow-up of 5.3 years, 34 patients with severe psoriasis were diagnosed with any type of lymphoma, for an incidence of 5.2 cases per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 3.7-7.3). In contrast, incidence rates for patients with mild psoriasis and controls were 3.3 and 3.2 cases per 10,000 person-years, respectively, Dr. Fuxench said.

In the multivariable analysis, patients with psoriasis were about 18% more likely to develop any type of lymphoma than were controls, an association that reached statistical significance (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.31). Mild psoriasis increased lymphoma risk by 14%, and severe psoriasis upped it by about 83%, and both associations were statistically significant.

The increase in risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was 13% greater with mild psoriasis and 56% greater with severe disease, compared with controls, and these associations also reached statistical significance. Mild psoriasis was not linked to Hodgkin lymphoma, but patients with severe psoriasis were about 250% more likely to develop it than controls, with a trend toward statistical significance (aHR, 2.54; 95% CI, 0.94-6.87).

Finally, severe psoriasis was linked to a more than ninefold increase in risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (aHR, 9.3; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), while mild psoriasis was linked to about a threefold increase in risk.

“These results were robust in multiple sensitivity analyses, including analyses that excluded patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or a history of exposure to methotrexate, cyclosporine, or biologics,” Dr. Fuxench said. Future studies should explore the effect of treatment timing and selection on cancer risk, she added. “For those of us who care for these patients, we are increasingly using systemic agents that selectively target the immune system, and these questions will arise in clinics.”

The study’s design made it possible to pinpoint dates of diagnosis more effectively than investigators could estimate disease duration or confirm whether patients initially diagnosed with psoriasis actually had cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Dr. Fuxench noted. “Ideally, we could have another cohort study of incident psoriasis with prospective follow-up, but lymphoma is so rare that there is currently not enough power [in the THIN database] to determine associations.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Fuxench disclosed unrestricted research funding from Pfizer outside the submitted work.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Psoriasis of all severities was linked to a 3.5-fold increase in risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and severe psoriasis upped the associated risk of Hodgkin lymphoma by about 2.5 times, in a large, longitudinal, population-based cohort study.

Psoriasis also was tied to a smaller but statistically significant increase in the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, said Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, of the department of dermatology, the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Overall, lymphoma risk was highest in people with severe psoriasis, independent of traditional risk factors and exposure to immunosuppressive medications, Dr. Fuxench said at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Psoriasis affects more than 125 million people worldwide, and severe cases are a major cause of cancer-related mortality. “Prior studies have suggested an increased risk of lymphoma in psoriasis patients, but it is unclear if this due to chronic inflammation, exposure to immunosuppressive therapies, or a combination of both factors,” Dr. Fuxench said.

To further explore these links, she and her associates analyzed electronic medical records from THIN (The Health Information Network), which includes about 12 million patients across the United Kingdom. Adults with psoriasis were matched to up to five nonpsoriatic controls based on date and clinic location. Patients who needed systemic medications or phototherapy were categorized as having severe psoriasis. The final dataset included more than 12,000 such patients, as well as 184,000 patients with mild psoriasis and more than 965,000 patients without psoriasis.

Psoriasis patients were younger and more likely to be overweight, male, and smoke and drink alcohol than patients without psoriasis, Dr. Fuxench said. Almost 80% of patients with severe disease had received systemic therapies, most often methotrexate (70% of systemic treatments) or cyclosporine (10%), while only 1% had received biologics.

Patients with severe psoriasis were more likely to be diagnosed with Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma than were patients with mild psoriasis or controls. Over a median follow-up of 5.3 years, 34 patients with severe psoriasis were diagnosed with any type of lymphoma, for an incidence of 5.2 cases per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 3.7-7.3). In contrast, incidence rates for patients with mild psoriasis and controls were 3.3 and 3.2 cases per 10,000 person-years, respectively, Dr. Fuxench said.

In the multivariable analysis, patients with psoriasis were about 18% more likely to develop any type of lymphoma than were controls, an association that reached statistical significance (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.06-1.31). Mild psoriasis increased lymphoma risk by 14%, and severe psoriasis upped it by about 83%, and both associations were statistically significant.

The increase in risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was 13% greater with mild psoriasis and 56% greater with severe disease, compared with controls, and these associations also reached statistical significance. Mild psoriasis was not linked to Hodgkin lymphoma, but patients with severe psoriasis were about 250% more likely to develop it than controls, with a trend toward statistical significance (aHR, 2.54; 95% CI, 0.94-6.87).

Finally, severe psoriasis was linked to a more than ninefold increase in risk of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (aHR, 9.3; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4), while mild psoriasis was linked to about a threefold increase in risk.

“These results were robust in multiple sensitivity analyses, including analyses that excluded patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or a history of exposure to methotrexate, cyclosporine, or biologics,” Dr. Fuxench said. Future studies should explore the effect of treatment timing and selection on cancer risk, she added. “For those of us who care for these patients, we are increasingly using systemic agents that selectively target the immune system, and these questions will arise in clinics.”

The study’s design made it possible to pinpoint dates of diagnosis more effectively than investigators could estimate disease duration or confirm whether patients initially diagnosed with psoriasis actually had cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Dr. Fuxench noted. “Ideally, we could have another cohort study of incident psoriasis with prospective follow-up, but lymphoma is so rare that there is currently not enough power [in the THIN database] to determine associations.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Fuxench disclosed unrestricted research funding from Pfizer outside the submitted work.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Psoriasis was identified as an independent risk factor for lymphoma, with the risk of lymphoma increasing with disease severity.

Major finding: The strongest association was between severe psoriasis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (aHR, 9.3; 95% CI, 4.1-21.4).

Data source: A population-based longitudinal cohort study of 12,198 patients with severe psoriasis, 184,870 patients with mild psoriasis, and 965,730 nonpsoriatic controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Fuxench disclosed unrestricted research support from Pfizer outside the submitted work.

Mogamulizumab achieves objective responses in relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma

CHICAGO – The anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab was superior to other investigator-selected therapies for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL), based on results from 71 patients in a prospective, multicenter, randomized study reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Commonly used cytotoxic regimens provided limited therapeutic benefit for these patients, but mogamulizumab resulted in an objective response rate that supports its therapeutic potential in this setting, reported Dr. Adrienne Alise Phillips of New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

A malignancy of T-cells infected with HTLV-1, ATL has a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of less than 3 months in patients with relapsed/refractory disease. CCR4 is expressed in over 90% of ATL patients, and mogamulizumab is approved in Japan for ATL as well as for peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The 71 patients in the study were from the United States, the European Union and Latin America. The study is the largest randomized clinical trial of relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma thus far conducted. The patients were randomized in 2:1 fashion 47:24 patients) to mogamulizumab, 1.0 mg/kg, given weekly for the first 4-week cycle and then biweekly, or to one of three investigator choice regimens [gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin), or pralatrexate]. Patients who were in the investigator-choice arm and whose disease progressed were permitted to cross over to mogamulizumab.

The primary endpoint was objective response rate based on modified Tsukasaki criteria and assessed by the treating investigator and in blinded fashion by independent review.

The objective response rate in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 23.4% (11 of 47) by independent review and 34% (16 of 47) by the treating investigator. In the investigator choice group, the overall response rate was 2 of 24 by independent review and 0 of 24 by the treating investigator.

The confirmed objective response rate after 1 month in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 10.6% by independent review and 14.9% by the treating investigator; there were no confirmed responses in the investigator-choice arm. Of 18 patients who crossed over to mogamulizumab, 3 responded. The median duration of response for mogamulizumab was 5 months; one patient had a complete response that lasted over 9 months and the survival data are not yet mature.

Mogamulizumab had few drug-related adverse events, primarily infusion reactions (46.8%), rash/drug eruption (25.5%) and infections (14.9%).

Dr. Phillips disclosed ties to Celgene, Genentech, and Takeda, as well as research funding from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, the sponsor of the study.

On Twitter @maryjodales

|

| Mary Jo Dales/Frontline Medical News Dr. Sonali M. Smith |

Mogamulizumab was superior to investigator’s choice therapy in the largest prospective randomized trial of this very rare disease. Approximately one-third of patients responded, while the response to investigator’s choice therapies was zero. The potential impact of mogamulizumab on T-cell regulation is intriguing. Could it have applications in other T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas?

Dr. Sonali M. Smith is with the University of Chicago and was the invited discussant of the study.

|

| Mary Jo Dales/Frontline Medical News Dr. Sonali M. Smith |

Mogamulizumab was superior to investigator’s choice therapy in the largest prospective randomized trial of this very rare disease. Approximately one-third of patients responded, while the response to investigator’s choice therapies was zero. The potential impact of mogamulizumab on T-cell regulation is intriguing. Could it have applications in other T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas?

Dr. Sonali M. Smith is with the University of Chicago and was the invited discussant of the study.

|

| Mary Jo Dales/Frontline Medical News Dr. Sonali M. Smith |

Mogamulizumab was superior to investigator’s choice therapy in the largest prospective randomized trial of this very rare disease. Approximately one-third of patients responded, while the response to investigator’s choice therapies was zero. The potential impact of mogamulizumab on T-cell regulation is intriguing. Could it have applications in other T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and cutaneous T-cell lymphomas?

Dr. Sonali M. Smith is with the University of Chicago and was the invited discussant of the study.

CHICAGO – The anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab was superior to other investigator-selected therapies for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL), based on results from 71 patients in a prospective, multicenter, randomized study reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Commonly used cytotoxic regimens provided limited therapeutic benefit for these patients, but mogamulizumab resulted in an objective response rate that supports its therapeutic potential in this setting, reported Dr. Adrienne Alise Phillips of New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

A malignancy of T-cells infected with HTLV-1, ATL has a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of less than 3 months in patients with relapsed/refractory disease. CCR4 is expressed in over 90% of ATL patients, and mogamulizumab is approved in Japan for ATL as well as for peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The 71 patients in the study were from the United States, the European Union and Latin America. The study is the largest randomized clinical trial of relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma thus far conducted. The patients were randomized in 2:1 fashion 47:24 patients) to mogamulizumab, 1.0 mg/kg, given weekly for the first 4-week cycle and then biweekly, or to one of three investigator choice regimens [gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin), or pralatrexate]. Patients who were in the investigator-choice arm and whose disease progressed were permitted to cross over to mogamulizumab.

The primary endpoint was objective response rate based on modified Tsukasaki criteria and assessed by the treating investigator and in blinded fashion by independent review.

The objective response rate in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 23.4% (11 of 47) by independent review and 34% (16 of 47) by the treating investigator. In the investigator choice group, the overall response rate was 2 of 24 by independent review and 0 of 24 by the treating investigator.

The confirmed objective response rate after 1 month in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 10.6% by independent review and 14.9% by the treating investigator; there were no confirmed responses in the investigator-choice arm. Of 18 patients who crossed over to mogamulizumab, 3 responded. The median duration of response for mogamulizumab was 5 months; one patient had a complete response that lasted over 9 months and the survival data are not yet mature.

Mogamulizumab had few drug-related adverse events, primarily infusion reactions (46.8%), rash/drug eruption (25.5%) and infections (14.9%).

Dr. Phillips disclosed ties to Celgene, Genentech, and Takeda, as well as research funding from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, the sponsor of the study.

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – The anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab was superior to other investigator-selected therapies for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL), based on results from 71 patients in a prospective, multicenter, randomized study reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Commonly used cytotoxic regimens provided limited therapeutic benefit for these patients, but mogamulizumab resulted in an objective response rate that supports its therapeutic potential in this setting, reported Dr. Adrienne Alise Phillips of New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical College, New York.

A malignancy of T-cells infected with HTLV-1, ATL has a poor prognosis with a median overall survival of less than 3 months in patients with relapsed/refractory disease. CCR4 is expressed in over 90% of ATL patients, and mogamulizumab is approved in Japan for ATL as well as for peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

The 71 patients in the study were from the United States, the European Union and Latin America. The study is the largest randomized clinical trial of relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma thus far conducted. The patients were randomized in 2:1 fashion 47:24 patients) to mogamulizumab, 1.0 mg/kg, given weekly for the first 4-week cycle and then biweekly, or to one of three investigator choice regimens [gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin), or pralatrexate]. Patients who were in the investigator-choice arm and whose disease progressed were permitted to cross over to mogamulizumab.

The primary endpoint was objective response rate based on modified Tsukasaki criteria and assessed by the treating investigator and in blinded fashion by independent review.

The objective response rate in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 23.4% (11 of 47) by independent review and 34% (16 of 47) by the treating investigator. In the investigator choice group, the overall response rate was 2 of 24 by independent review and 0 of 24 by the treating investigator.

The confirmed objective response rate after 1 month in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 10.6% by independent review and 14.9% by the treating investigator; there were no confirmed responses in the investigator-choice arm. Of 18 patients who crossed over to mogamulizumab, 3 responded. The median duration of response for mogamulizumab was 5 months; one patient had a complete response that lasted over 9 months and the survival data are not yet mature.

Mogamulizumab had few drug-related adverse events, primarily infusion reactions (46.8%), rash/drug eruption (25.5%) and infections (14.9%).

Dr. Phillips disclosed ties to Celgene, Genentech, and Takeda, as well as research funding from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, the sponsor of the study.

On Twitter @maryjodales

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab was superior to other investigator-selected therapies for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma.

Major finding: The confirmed objective response rate after 1 month in the mogamulizumab-treated group was 10.6% by independent review and 14.9% by the treating investigator; there were no confirmed responses in the investigator-choice arm.

Data source: Prospective, multicenter, randomized study of 71 patients from the United States, the European Union, and Latin America.

Disclosures: Dr. Phillips disclosed ties to Celgene, Genentech, and Takeda, as well as research funding from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, the sponsor of the study.

Alemtuzumab plus CHOP didn’t boost survival in elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas

CHICAGO – Adding the monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab to CHOP (A-CHOP) increased response rates in elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas but did not improve their survival, based on the final results from 116 patients treated in the international ACT-2 phase III trial.

Complete responses were seen in 43% of 58 patients given CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) and in 60% of 58 patients given A-CHOP in the trial. However, trial participants did not significantly differ in event-free survival and progression-free survival at 3 years.

Further, overall survival at 3 years was 38% for the patients given A-CHOP and 56% for the patients given CHOP. The poorer overall survival was mainly the result of treatment-related toxicity, Dr. Lorenz H. Trümper reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The estimated 3-year disease-free survival is 25% for elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Previous phase II trials had indicated that alemtuzumab was active in primary and relapsed T-cell lymphoma, prompting the study of adjuvant alemtuzumab in combination with dose-dense CHOP-14 in patients with previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma, he said.

Although the treatment protocol demanded stringent monitoring for cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus and anti-infective prophylaxis, there were more grade 3 or higher infections in the A-CHOP group (40%) than the CHOP group (21%). The higher infection rates were attributed to higher rates of grade 3/4 hematotoxicity in patients given A-CHOP. Grade 4 leukocytopenia was seen in 70% with A-CHOP and 54% with CHOP; grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia was seen in 19% given A-CHOP and 13% given CHOP, according to Dr. Trümper of the University of Göttingen, Germany.

For the study, 116 patients from 52 centers were randomized to receive either six cycles of CHOP or A-CHOP given at 14-day intervals with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) support. Initially, patients received a total of 360 mg of alemtuzumab (90 mg given at each of the first four cycles of CHOP). After patient 39 was enrolled, the dose was reduced to 120 mg (30 mg given at each of the first four cycles of CHOP). Median patient age was 69 years, and 58% of the trial participants were men.

Treatment was completed as planned in 79% of the CHOP patients and in 57% of the A-CHOP patients.

The study was sponsored by the University of Göttingen. Dr. Trümper is a consultant or adviser to Hexal and Janssen-Ortho, and receives research funding from Genzyme, the maker of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), as well as other drug companies.

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – Adding the monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab to CHOP (A-CHOP) increased response rates in elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas but did not improve their survival, based on the final results from 116 patients treated in the international ACT-2 phase III trial.

Complete responses were seen in 43% of 58 patients given CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) and in 60% of 58 patients given A-CHOP in the trial. However, trial participants did not significantly differ in event-free survival and progression-free survival at 3 years.

Further, overall survival at 3 years was 38% for the patients given A-CHOP and 56% for the patients given CHOP. The poorer overall survival was mainly the result of treatment-related toxicity, Dr. Lorenz H. Trümper reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The estimated 3-year disease-free survival is 25% for elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Previous phase II trials had indicated that alemtuzumab was active in primary and relapsed T-cell lymphoma, prompting the study of adjuvant alemtuzumab in combination with dose-dense CHOP-14 in patients with previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma, he said.

Although the treatment protocol demanded stringent monitoring for cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus and anti-infective prophylaxis, there were more grade 3 or higher infections in the A-CHOP group (40%) than the CHOP group (21%). The higher infection rates were attributed to higher rates of grade 3/4 hematotoxicity in patients given A-CHOP. Grade 4 leukocytopenia was seen in 70% with A-CHOP and 54% with CHOP; grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia was seen in 19% given A-CHOP and 13% given CHOP, according to Dr. Trümper of the University of Göttingen, Germany.

For the study, 116 patients from 52 centers were randomized to receive either six cycles of CHOP or A-CHOP given at 14-day intervals with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) support. Initially, patients received a total of 360 mg of alemtuzumab (90 mg given at each of the first four cycles of CHOP). After patient 39 was enrolled, the dose was reduced to 120 mg (30 mg given at each of the first four cycles of CHOP). Median patient age was 69 years, and 58% of the trial participants were men.

Treatment was completed as planned in 79% of the CHOP patients and in 57% of the A-CHOP patients.

The study was sponsored by the University of Göttingen. Dr. Trümper is a consultant or adviser to Hexal and Janssen-Ortho, and receives research funding from Genzyme, the maker of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), as well as other drug companies.

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – Adding the monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab to CHOP (A-CHOP) increased response rates in elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas but did not improve their survival, based on the final results from 116 patients treated in the international ACT-2 phase III trial.

Complete responses were seen in 43% of 58 patients given CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) and in 60% of 58 patients given A-CHOP in the trial. However, trial participants did not significantly differ in event-free survival and progression-free survival at 3 years.

Further, overall survival at 3 years was 38% for the patients given A-CHOP and 56% for the patients given CHOP. The poorer overall survival was mainly the result of treatment-related toxicity, Dr. Lorenz H. Trümper reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The estimated 3-year disease-free survival is 25% for elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Previous phase II trials had indicated that alemtuzumab was active in primary and relapsed T-cell lymphoma, prompting the study of adjuvant alemtuzumab in combination with dose-dense CHOP-14 in patients with previously untreated peripheral T-cell lymphoma, he said.

Although the treatment protocol demanded stringent monitoring for cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus and anti-infective prophylaxis, there were more grade 3 or higher infections in the A-CHOP group (40%) than the CHOP group (21%). The higher infection rates were attributed to higher rates of grade 3/4 hematotoxicity in patients given A-CHOP. Grade 4 leukocytopenia was seen in 70% with A-CHOP and 54% with CHOP; grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia was seen in 19% given A-CHOP and 13% given CHOP, according to Dr. Trümper of the University of Göttingen, Germany.

For the study, 116 patients from 52 centers were randomized to receive either six cycles of CHOP or A-CHOP given at 14-day intervals with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) support. Initially, patients received a total of 360 mg of alemtuzumab (90 mg given at each of the first four cycles of CHOP). After patient 39 was enrolled, the dose was reduced to 120 mg (30 mg given at each of the first four cycles of CHOP). Median patient age was 69 years, and 58% of the trial participants were men.

Treatment was completed as planned in 79% of the CHOP patients and in 57% of the A-CHOP patients.

The study was sponsored by the University of Göttingen. Dr. Trümper is a consultant or adviser to Hexal and Janssen-Ortho, and receives research funding from Genzyme, the maker of alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), as well as other drug companies.

On Twitter @maryjodales

AT ASCO 16

Key clinical point: Adding the monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody alemtuzumab to CHOP (A-CHOP) increased response rates in elderly patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas but did not improve their survival.

Major finding: Overall survival at 3 years was 38% for the patients given A-CHOP and 56% for the patients given CHOP.

Data source: Results from 116 patients treated in the international ACT-2 phase III trial.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the University of Göttingen, Germany. Dr. Trümper is a consultant or adviser to Hexal and Janssen-Ortho, and receives research funding from Genzyme, the maker of alemtuzumab, as well as other drug companies.

Dr. Matt Kalaycio’s top 10 hematologic oncology abstracts for ASCO 2016

Hematology News’ Editor-in-Chief Matt Kalaycio selected the following as his “top 10” picks for hematologic oncology abstracts at ASCO 2016:

Abstract 7000: Final results of a phase III randomized trial of CPX-351 versus 7+3 in older patients with newly diagnosed high risk (secondary) AML

Comment: When any treatment appears to improve survival, compared with 7+3 for AML, all must take notice.

Abstract 7001: Treatment-free remission (TFR) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with frontline nilotinib: Results from the ENESTFreedom study

Comment: About 50% of the CML patients treated with frontline nilotinib are eventually able to stop the drug and successfully stay off of it. That means more patients in treatment-free remission, compared with those initially treated with imatinib.

Link to abstract 7001

Abstract 7007: Phase Ib/2 study of venetoclax with low-dose cytarabine in treatment-naive patients age ≥ 65 with acute myelogenous leukemia

Abstract 7009: Results of a phase 1b study of venetoclax plus decitabine or azacitidine in untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients ≥ 65 years ineligible for standard induction therapy

Comment: The response rates in these older AML patients are remarkable and challenge results typically seen with 7+3 in a younger population.

Link to abstract 7007 and 7009

Abstract 7501: A prospective, multicenter, randomized study of anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab (moga) vs investigator’s choice (IC) in the treatment of patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory (R/R) adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL)

Comment: The response rate to mogamulizumab was outstanding in the largest randomized clinical trial thus far conducted for this cancer. Although rare in the USA, ATL is more common in Asia.

Link to abstract 7501

Abstract 7507: Effect of bortezomib on complete remission (CR) rate when added to bendamustine-rituximab (BR) in previously untreated high-risk (HR) follicular lymphoma (FL): A randomized phase II trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2408)

Comment: This interesting observation of improved complete remission needs longer follow-up.

Link to abstract 7507

Abstract 7519: Venetoclax activity in CLL patients who have relapsed after or are refractory to ibrutinib or idelalisib

Comment: This study has implications for practice. Venetoclax elicits a 50%-60% response rate after patients with CLL progress during treatment with B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors.

Link to abstract 7519

Abstract 7521: Acalabrutinib, a second-generation bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor, in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Comment: This next-generation variation on ibrutinib was associated with a 96% overall response rate with fewer adverse effects such as atrial fibrillation.

Link to abstract 7521

Abstract 8000: Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) versus novel agent-based therapy for multiple myeloma (MM): A randomized phase 3 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN02/HO95 MM trial)

Comment: Other trials are underway to address the role of upfront ASCT for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. While the last word on this issue has yet to be written, ASCT remains the standard of care for MM patients after induction.

Link to abstract 8000

LBA4: Phase III randomized controlled study of daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DVd) versus bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): CASTOR study

Comment: As predicted by most, the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib-based therapy increases response rates, compared with bortezomib-based alone. Efficacy is becoming less of a concern with myeloma treatment than is economics..

Look for the full, final text of this abstract to be posted online at 7:30 AM (EDT) on Sunday, June 5.

Hematology News’ Editor-in-Chief Matt Kalaycio selected the following as his “top 10” picks for hematologic oncology abstracts at ASCO 2016:

Abstract 7000: Final results of a phase III randomized trial of CPX-351 versus 7+3 in older patients with newly diagnosed high risk (secondary) AML

Comment: When any treatment appears to improve survival, compared with 7+3 for AML, all must take notice.

Abstract 7001: Treatment-free remission (TFR) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with frontline nilotinib: Results from the ENESTFreedom study

Comment: About 50% of the CML patients treated with frontline nilotinib are eventually able to stop the drug and successfully stay off of it. That means more patients in treatment-free remission, compared with those initially treated with imatinib.

Link to abstract 7001

Abstract 7007: Phase Ib/2 study of venetoclax with low-dose cytarabine in treatment-naive patients age ≥ 65 with acute myelogenous leukemia

Abstract 7009: Results of a phase 1b study of venetoclax plus decitabine or azacitidine in untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients ≥ 65 years ineligible for standard induction therapy

Comment: The response rates in these older AML patients are remarkable and challenge results typically seen with 7+3 in a younger population.

Link to abstract 7007 and 7009

Abstract 7501: A prospective, multicenter, randomized study of anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab (moga) vs investigator’s choice (IC) in the treatment of patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory (R/R) adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL)

Comment: The response rate to mogamulizumab was outstanding in the largest randomized clinical trial thus far conducted for this cancer. Although rare in the USA, ATL is more common in Asia.

Link to abstract 7501

Abstract 7507: Effect of bortezomib on complete remission (CR) rate when added to bendamustine-rituximab (BR) in previously untreated high-risk (HR) follicular lymphoma (FL): A randomized phase II trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2408)

Comment: This interesting observation of improved complete remission needs longer follow-up.

Link to abstract 7507

Abstract 7519: Venetoclax activity in CLL patients who have relapsed after or are refractory to ibrutinib or idelalisib

Comment: This study has implications for practice. Venetoclax elicits a 50%-60% response rate after patients with CLL progress during treatment with B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors.

Link to abstract 7519

Abstract 7521: Acalabrutinib, a second-generation bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor, in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Comment: This next-generation variation on ibrutinib was associated with a 96% overall response rate with fewer adverse effects such as atrial fibrillation.

Link to abstract 7521

Abstract 8000: Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) versus novel agent-based therapy for multiple myeloma (MM): A randomized phase 3 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN02/HO95 MM trial)

Comment: Other trials are underway to address the role of upfront ASCT for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. While the last word on this issue has yet to be written, ASCT remains the standard of care for MM patients after induction.

Link to abstract 8000

LBA4: Phase III randomized controlled study of daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DVd) versus bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): CASTOR study

Comment: As predicted by most, the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib-based therapy increases response rates, compared with bortezomib-based alone. Efficacy is becoming less of a concern with myeloma treatment than is economics..

Look for the full, final text of this abstract to be posted online at 7:30 AM (EDT) on Sunday, June 5.

Hematology News’ Editor-in-Chief Matt Kalaycio selected the following as his “top 10” picks for hematologic oncology abstracts at ASCO 2016:

Abstract 7000: Final results of a phase III randomized trial of CPX-351 versus 7+3 in older patients with newly diagnosed high risk (secondary) AML

Comment: When any treatment appears to improve survival, compared with 7+3 for AML, all must take notice.

Abstract 7001: Treatment-free remission (TFR) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with frontline nilotinib: Results from the ENESTFreedom study

Comment: About 50% of the CML patients treated with frontline nilotinib are eventually able to stop the drug and successfully stay off of it. That means more patients in treatment-free remission, compared with those initially treated with imatinib.

Link to abstract 7001

Abstract 7007: Phase Ib/2 study of venetoclax with low-dose cytarabine in treatment-naive patients age ≥ 65 with acute myelogenous leukemia

Abstract 7009: Results of a phase 1b study of venetoclax plus decitabine or azacitidine in untreated acute myeloid leukemia patients ≥ 65 years ineligible for standard induction therapy

Comment: The response rates in these older AML patients are remarkable and challenge results typically seen with 7+3 in a younger population.

Link to abstract 7007 and 7009

Abstract 7501: A prospective, multicenter, randomized study of anti-CCR4 monoclonal antibody mogamulizumab (moga) vs investigator’s choice (IC) in the treatment of patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory (R/R) adult T-cell leukemia-lymphoma (ATL)

Comment: The response rate to mogamulizumab was outstanding in the largest randomized clinical trial thus far conducted for this cancer. Although rare in the USA, ATL is more common in Asia.

Link to abstract 7501

Abstract 7507: Effect of bortezomib on complete remission (CR) rate when added to bendamustine-rituximab (BR) in previously untreated high-risk (HR) follicular lymphoma (FL): A randomized phase II trial of the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (E2408)

Comment: This interesting observation of improved complete remission needs longer follow-up.

Link to abstract 7507

Abstract 7519: Venetoclax activity in CLL patients who have relapsed after or are refractory to ibrutinib or idelalisib

Comment: This study has implications for practice. Venetoclax elicits a 50%-60% response rate after patients with CLL progress during treatment with B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors.

Link to abstract 7519

Abstract 7521: Acalabrutinib, a second-generation bruton tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor, in previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Comment: This next-generation variation on ibrutinib was associated with a 96% overall response rate with fewer adverse effects such as atrial fibrillation.

Link to abstract 7521

Abstract 8000: Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) versus novel agent-based therapy for multiple myeloma (MM): A randomized phase 3 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN02/HO95 MM trial)

Comment: Other trials are underway to address the role of upfront ASCT for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. While the last word on this issue has yet to be written, ASCT remains the standard of care for MM patients after induction.

Link to abstract 8000

LBA4: Phase III randomized controlled study of daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DVd) versus bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): CASTOR study