User login

Right under our noses

Until a couple of weeks ago I considered myself a COVID virgin. I had navigated a full 36 months without a positive test, despite cohabiting with my wife in a 2,500-square-foot house during her bout with the SARS-CoV-2 virus last year. I have been reasonably careful, a situational mask wearer, and good about avoiding poorly ventilated crowded spaces. Of course I was fully vaccinated but was waiting until we had gotten closer to a December trip before getting the newest booster.

I had always been quietly smug about my good luck. And, I was pretty sure that luck had been the major contributor to my run of good health. Nonetheless, in my private moments I often wondered if I somehow had inherited or acquired an unusual defense against the virus that had been getting the best of my peers. One rather far-fetched explanation that kept popping out of my subconscious involved my profuse and persistent runny nose.

Like a fair number in my demographic, I have what I have self-diagnosed as vasomotor rhinitis. In the cooler months and particularly when I am active outdoors, my nose runs like a faucet. I half-jokingly told my wife after a particularly drippy bike ride on a frigid November afternoon that even the most robust virus couldn’t possibly have survived the swim upstream against torrent of mucus splashing onto the handlebars of my bike.

A recent study published in the journal Cell suggests that my off-the-wall explanation for my COVID resistance wasn’t quite so hair-brained. The investigators haven’t found that septuagenarian adults with high-volume runny noses are drowning the SARS-Co- 2 virus before it can do any damage. However, the researchers did discover that, This first line of defense seems to be more effective than in adults, where the virus can more easily slip through into the bloodstream, sometimes with a dramatic release of circulating cytokines, which occasionally create problems of their own. Children also release cytokines, but this is predominantly in their nose, where it appears to be less damaging. Interestingly, in children this initial response persists for around 300 days while in adults the immune response experiences a much more rapid decline. I guess this means we have to chalk one more up for snotty nose kids.

However, the results of this study also suggest that we should be giving more attention to the development of nasal vaccines. I recall that nearly 3 years ago, at the beginning of the pandemic, scientists using a ferret model had developed an effective nasal vaccine. I’m not sure why this faded out of the picture, but it feels like it’s time to turn the spotlight on this line of research again.

I suspect that in addition to being more effective, a nasal vaccine may gain more support among the antivaxxer population, many of whom I suspect are really needle phobics hiding behind a smoke screen of anti-science double talk.

At any rate, I will continue to search for articles that support my contention that my high-flow rhinorrhea is protecting me. I have always been told that a cold nose was the sign of a healthy dog. I’m just trying to prove that the same is true for us old guys with clear runny noses.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Until a couple of weeks ago I considered myself a COVID virgin. I had navigated a full 36 months without a positive test, despite cohabiting with my wife in a 2,500-square-foot house during her bout with the SARS-CoV-2 virus last year. I have been reasonably careful, a situational mask wearer, and good about avoiding poorly ventilated crowded spaces. Of course I was fully vaccinated but was waiting until we had gotten closer to a December trip before getting the newest booster.

I had always been quietly smug about my good luck. And, I was pretty sure that luck had been the major contributor to my run of good health. Nonetheless, in my private moments I often wondered if I somehow had inherited or acquired an unusual defense against the virus that had been getting the best of my peers. One rather far-fetched explanation that kept popping out of my subconscious involved my profuse and persistent runny nose.

Like a fair number in my demographic, I have what I have self-diagnosed as vasomotor rhinitis. In the cooler months and particularly when I am active outdoors, my nose runs like a faucet. I half-jokingly told my wife after a particularly drippy bike ride on a frigid November afternoon that even the most robust virus couldn’t possibly have survived the swim upstream against torrent of mucus splashing onto the handlebars of my bike.

A recent study published in the journal Cell suggests that my off-the-wall explanation for my COVID resistance wasn’t quite so hair-brained. The investigators haven’t found that septuagenarian adults with high-volume runny noses are drowning the SARS-Co- 2 virus before it can do any damage. However, the researchers did discover that, This first line of defense seems to be more effective than in adults, where the virus can more easily slip through into the bloodstream, sometimes with a dramatic release of circulating cytokines, which occasionally create problems of their own. Children also release cytokines, but this is predominantly in their nose, where it appears to be less damaging. Interestingly, in children this initial response persists for around 300 days while in adults the immune response experiences a much more rapid decline. I guess this means we have to chalk one more up for snotty nose kids.

However, the results of this study also suggest that we should be giving more attention to the development of nasal vaccines. I recall that nearly 3 years ago, at the beginning of the pandemic, scientists using a ferret model had developed an effective nasal vaccine. I’m not sure why this faded out of the picture, but it feels like it’s time to turn the spotlight on this line of research again.

I suspect that in addition to being more effective, a nasal vaccine may gain more support among the antivaxxer population, many of whom I suspect are really needle phobics hiding behind a smoke screen of anti-science double talk.

At any rate, I will continue to search for articles that support my contention that my high-flow rhinorrhea is protecting me. I have always been told that a cold nose was the sign of a healthy dog. I’m just trying to prove that the same is true for us old guys with clear runny noses.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Until a couple of weeks ago I considered myself a COVID virgin. I had navigated a full 36 months without a positive test, despite cohabiting with my wife in a 2,500-square-foot house during her bout with the SARS-CoV-2 virus last year. I have been reasonably careful, a situational mask wearer, and good about avoiding poorly ventilated crowded spaces. Of course I was fully vaccinated but was waiting until we had gotten closer to a December trip before getting the newest booster.

I had always been quietly smug about my good luck. And, I was pretty sure that luck had been the major contributor to my run of good health. Nonetheless, in my private moments I often wondered if I somehow had inherited or acquired an unusual defense against the virus that had been getting the best of my peers. One rather far-fetched explanation that kept popping out of my subconscious involved my profuse and persistent runny nose.

Like a fair number in my demographic, I have what I have self-diagnosed as vasomotor rhinitis. In the cooler months and particularly when I am active outdoors, my nose runs like a faucet. I half-jokingly told my wife after a particularly drippy bike ride on a frigid November afternoon that even the most robust virus couldn’t possibly have survived the swim upstream against torrent of mucus splashing onto the handlebars of my bike.

A recent study published in the journal Cell suggests that my off-the-wall explanation for my COVID resistance wasn’t quite so hair-brained. The investigators haven’t found that septuagenarian adults with high-volume runny noses are drowning the SARS-Co- 2 virus before it can do any damage. However, the researchers did discover that, This first line of defense seems to be more effective than in adults, where the virus can more easily slip through into the bloodstream, sometimes with a dramatic release of circulating cytokines, which occasionally create problems of their own. Children also release cytokines, but this is predominantly in their nose, where it appears to be less damaging. Interestingly, in children this initial response persists for around 300 days while in adults the immune response experiences a much more rapid decline. I guess this means we have to chalk one more up for snotty nose kids.

However, the results of this study also suggest that we should be giving more attention to the development of nasal vaccines. I recall that nearly 3 years ago, at the beginning of the pandemic, scientists using a ferret model had developed an effective nasal vaccine. I’m not sure why this faded out of the picture, but it feels like it’s time to turn the spotlight on this line of research again.

I suspect that in addition to being more effective, a nasal vaccine may gain more support among the antivaxxer population, many of whom I suspect are really needle phobics hiding behind a smoke screen of anti-science double talk.

At any rate, I will continue to search for articles that support my contention that my high-flow rhinorrhea is protecting me. I have always been told that a cold nose was the sign of a healthy dog. I’m just trying to prove that the same is true for us old guys with clear runny noses.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

How clinicians can prepare for and defend against social media attacks

WASHINGTON – The entire video clip is just 15 seconds — 15 seconds that went viral and temporarily upended the entire life and disrupted the medical practice of Nicole Baldwin, MD, a pediatrician in Cincinnati, Ohio, in January 2020. At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Baldwin told attendees how her pro-vaccine TikTok video led a horde of anti-vaccine activists to swarm her social media profiles across multiple platforms, leave one-star reviews with false stories about her medical practice on various doctor review sites, and personally threaten her.

The initial response to the video was positive, with 50,000 views in the first 24 hours after the video was posted and more than 1.5 million views the next day. But 2 days after the video was posted, an organized attack that originated on Facebook required Dr. Baldwin to enlist the help of 16 volunteers, working 24/7 for a week, to help ban and block more than 6,000 users on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok. Just 4 days after she’d posted the video, Dr. Baldwin was reporting personal threats to the police and had begun contacting sites such as Yelp, Google, Healthgrades, Vitals, RateMDs, and WebMD so they could start removing false reviews about her practice.

Today, years after those 2 exhausting, intense weeks of attacks, Dr. Baldwin has found two silver linings in the experience: More people have found her profiles, allowing her to share evidence-based information with an even wider audience, and she can now help other physicians protect themselves and reduce the risk of similar attacks, or at least know how to respond to them if they occur. Dr. Baldwin shared a wealth of tips and resources during her lecture to help pediatricians prepare ahead for the possibility that they will be targeted next, whether the issue is vaccines or another topic.

Online risks and benefits

A Pew survey of U.S. adults in September 2020 found that 41% have personally experienced online harassment, including a quarter of Americans who have experienced severe harassment. More than half of respondents said online harassment and bullying is a major problem – and that was a poll of the entire population, not even just physicians and scientists.

“Now, these numbers would be higher,” Dr. Baldwin said. “A lot has changed in the past 3 years, and the landscape is very different.”

The pandemic contributed to those changes to the landscape, including an increase in harassment of doctors and researchers. A June 2023 study revealed that two-thirds of 359 respondents in an online survey reported harassment on social media, a substantial number even after accounting for selection bias in the individuals who chose to respond to the survey. Although most of the attacks (88%) resulted from the respondent’s advocacy online, nearly half the attacks (45%) were gender based, 27% were based on race/ethnicity, and 13% were based on sexual orientation.

While hateful comments are likely the most common type of online harassment, other types can involve sharing or tagging your profile, creating fake profiles to misrepresent you, fake reviews of your practice, harassing phone calls and hate mail at your office, and doxxing, in which someone online widely shares your personal address, phone number, email, or other contact information.

Despite the risks of all these forms of harassment, Dr. Baldwin emphasized the value of doctors having a social media presence given how much misinformation thrives online. For example, a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed how many people weren’t sure whether certain health misinformation claims were true or false. Barely a third of people were sure that COVID-19 vaccines had not caused thousands of deaths in healthy people, and only 22% of people were sure that ivermectin is not an effective treatment for COVID.

“There is so much that we need to be doing and working in these spaces to put evidence-based content out there so that people are not finding all of this crap from everybody else,” Dr. Baldwin said. Having an online presence is particularly important given that the public still has high levels of trust in their doctors, she added.

“They trust their physician, and you may not be their physician online, but I will tell you from experience, when you build a community of followers, you become that trusted source of information for them, and it is so important,” Dr. Baldwin said. “There is room for everybody in this space, and we need all of you.”

Proactive steps for protection

Dr. Baldwin then went through the details of what people should do now to make things easier in the event of an attack later. “The best defense is a good offense,” Dr. Baldwin said, “so make sure all of your accounts are secure.”

She recommended the following steps:

- Use two-factor authentication for all of your logins.

- Use strong, unique passwords for all of your logins.

- Use strong privacy settings on all of your private social media profiles, such as making sure photos are not visible on your personal Facebook account.

- Claim your Google profile and Yelp business profile.

- Claim your doctor and/or business profile on all of the medical review sites where you have one, including Google, Healthgrades, Vitals, RateMDs, and WebMD.

For doctors who are attacked specifically because of pro-vaccine advocacy, Dr. Baldwin recommended contacting Shots Heard Round The World, a site that was created by a physician whose practice was attacked by anti-vaccine activists. The site also has a toolkit that anyone can download for tips on preparing ahead for possible attacks and what to do if you are attacked.

Dr. Baldwin then reviewed how to set up different social media profiles to automatically hide certain comments, including comments with words commonly used by online harassers and trolls:

- Sheep

- Sheeple

- Pharma

- Shill

- Die

- Psychopath

- Clown

- Various curse words

- The clown emoji

In Instagram, go to “Settings and privacy —> Hidden Words” for options on hiding offensive comments and messages and for managing custom words and phrases that should be automatically hidden.

On Facebook, go to “Professional dashboard —> Moderation Assist,” where you can add or edit criteria to automatically hide comments on your Facebook page. In addition to hiding comments with certain keywords, you can hide comments from new accounts, accounts without profile photos, or accounts with no friends or followers.

On TikTok, click the three-line menu icon in the upper right, and choose “Privacy —> Comments —> Filter keywords.”

On the platform formerly known as Twitter, go to “Settings and privacy —> Privacy and safety —> Mute and block —> Muted words.”

On YouTube, under “Manage your community & comments,” select “Learn about comment settings.”

Dr. Baldwin did not discourage doctors from posting about controversial topics, but she said it’s important to know what they are so that you can be prepared for the possibility that a post about one of these topics could lead to online harassment. These hot button topics include vaccines, firearm safety, gender-affirming care, reproductive choice, safe sleep/bedsharing, breastfeeding, and COVID masks.

If you do post on one of these and suspect it could result in harassment, Dr. Baldwin recommends turning on your notifications so you know when attacks begin, alerting your office and call center staff if you think they might receive calls, and, when possible, post your content at a time when you’re more likely to be able to monitor the post. She acknowledged that this last tip isn’t always relevant since attacks can take a few days to start or gain steam.

Defending yourself in an attack

Even after taking all these precautions, it’s not possible to altogether prevent an attack from happening, so Dr. Baldwin provided suggestions on what to do if one occurs, starting with taking a deep breath.

“If you are attacked, first of all, please remain calm, which is a lot easier said than done,” she said. “But know that this too shall pass. These things do come to an end.”

She advises you to get help if you need it, enlisting friends or colleagues to help with moderation and banning/blocking. If necessary, alert your employer to the attack, as attackers may contact your employer. Some people may opt to turn off comments on their post, but doing so “is a really personal decision,” she said. It’s okay to turn off comments if you don’t have the bandwidth or help to deal with them.

However, Dr. Baldwin said she never turns off comments because she wants to be able to ban and block people to reduce the likelihood of a future attack from them, and each comment brings the post higher in the algorithm so that more people are able to see the original content. “So sometimes these things are actually a blessing in disguise,” she said.

If you do have comments turned on, take screenshots of the most egregious or threatening ones and then report them and ban/block them. The screenshots are evidence since blocking will remove the comment.

“Take breaks when you need to,” she said. “Don’t stay up all night” since there are only going to be more in the morning, and if you’re using keywords to help hide many of these comments, that will hide them from your followers while you’re away. She also advised monitoring your online reviews at doctor/practice review sites so you know whether you’re receiving spurious reviews that need to be removed.

Dr. Baldwin also addressed how to handle trolls, the people online who intentionally antagonize others with inflammatory, irrelevant, offensive, or otherwise disruptive comments or content. The No. 1 rule is not to engage – “Don’t feed the trolls” – but Dr. Baldwin acknowledged that she can find that difficult sometimes. So she uses kindness or humor to defuse them or calls them out on their inaccurate information and then thanks them for their engagement. Don’t forget that you are in charge of your own page, so any complaints about “censorship” or infringing “free speech” aren’t relevant.

If the comments are growing out of control and you’re unable to manage them, multiple social media platforms have options for limited interactions or who can comment on your page.

On Instagram under “Settings and privacy,” check out “Limited interactions,” “Comments —> Allow comments from,” and “Tags and mentions” to see ways you can limit who is able to comment, tag or mention your account. If you need a complete break, you can turn off commenting by clicking the three dots in the upper right corner of the post, or make your account temporarily private under “Settings and privacy —> Account privacy.”

On Facebook, click the three dots in the upper right corner of posts to select “Who can comment on your post?” Also, under “Settings —> Privacy —> Your Activity,” you can adjust who sees your future posts. Again, if things are out of control, you can temporarily deactivate your page under “Settings —> Privacy —> Facebook Page information.”

On TikTok, click the three lines in the upper right corner of your profile and select “Privacy —> Comments” to adjust who can comment and to filter comments. Again, you can make your account private under “Settings and privacy —> Privacy —> Private account.”

On the platform formerly known as Twitter, click the three dots in the upper right corner of the tweet to change who can reply to the tweet. If you select “Only people you mentioned,” then no one can reply if you did not mention anyone. You can control tagging under “Settings and privacy —> Privacy and safety —> Audience and tagging.”

If you or your practice receive false reviews on review sites, report the reviews and alert the rating site when you can. In the meantime, lock down your private social media accounts and ensure that no photos of your family are publicly available.

Social media self-care

Dr. Baldwin acknowledged that experiencing a social media attack can be intense and even frightening, but it’s rare and outweighed by the “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of positive comments all the time.” She also reminded attendees that being on social media doesn’t mean being there all the time.

“Over time, my use of social media has certainly changed. It ebbs and flows,” she said. “There are times when I have a lot of bandwidth and I’m posting a lot, and then I actually have had some struggles with my own mental health, with some anxiety and mild depression, so I took a break from social media for a while. When I came back, I posted about my mental health struggles, and you wouldn’t believe how many people were so appreciative of that.”

Accurate information from a trusted source

Ultimately, Dr. Baldwin sees her work online as an extension of her work educating patients.

“This is where our patients are. They are in your office for maybe 10-15 minutes maybe once a year, but they are on these platforms every single day for hours,” she said. “They need to see this information from medical professionals because there are random people out there that are telling them [misinformation].”

Elizabeth Murray, DO, MBA, an emergency medicine pediatrician at Golisano Children’s Hospital at the University of Rochester, agreed that there’s substantial value in doctors sharing accurate information online.

“Disinformation and misinformation is rampant, and at the end of the day, we know the facts,” Dr. Murray said. “We know what parents want to hear and what they want to learn about, so we need to share that information and get the facts out there.”

Dr. Murray found the session very helpful because there’s so much to learn across different social media platforms and it can feel overwhelming if you aren’t familiar with the tools.

“Social media is always going to be here. We need to learn to live with all of these platforms,” Dr. Murray said. “That’s a skill set. We need to learn the skills and teach our kids the skill set. You never really know what you might put out there that, in your mind is innocent or very science-based, that for whatever reason somebody might take issue with. You might as well be ready because we’re all about prevention in pediatrics.”

There were no funders for the presentation. Dr. Baldwin and Dr. Murray had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The entire video clip is just 15 seconds — 15 seconds that went viral and temporarily upended the entire life and disrupted the medical practice of Nicole Baldwin, MD, a pediatrician in Cincinnati, Ohio, in January 2020. At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Baldwin told attendees how her pro-vaccine TikTok video led a horde of anti-vaccine activists to swarm her social media profiles across multiple platforms, leave one-star reviews with false stories about her medical practice on various doctor review sites, and personally threaten her.

The initial response to the video was positive, with 50,000 views in the first 24 hours after the video was posted and more than 1.5 million views the next day. But 2 days after the video was posted, an organized attack that originated on Facebook required Dr. Baldwin to enlist the help of 16 volunteers, working 24/7 for a week, to help ban and block more than 6,000 users on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok. Just 4 days after she’d posted the video, Dr. Baldwin was reporting personal threats to the police and had begun contacting sites such as Yelp, Google, Healthgrades, Vitals, RateMDs, and WebMD so they could start removing false reviews about her practice.

Today, years after those 2 exhausting, intense weeks of attacks, Dr. Baldwin has found two silver linings in the experience: More people have found her profiles, allowing her to share evidence-based information with an even wider audience, and she can now help other physicians protect themselves and reduce the risk of similar attacks, or at least know how to respond to them if they occur. Dr. Baldwin shared a wealth of tips and resources during her lecture to help pediatricians prepare ahead for the possibility that they will be targeted next, whether the issue is vaccines or another topic.

Online risks and benefits

A Pew survey of U.S. adults in September 2020 found that 41% have personally experienced online harassment, including a quarter of Americans who have experienced severe harassment. More than half of respondents said online harassment and bullying is a major problem – and that was a poll of the entire population, not even just physicians and scientists.

“Now, these numbers would be higher,” Dr. Baldwin said. “A lot has changed in the past 3 years, and the landscape is very different.”

The pandemic contributed to those changes to the landscape, including an increase in harassment of doctors and researchers. A June 2023 study revealed that two-thirds of 359 respondents in an online survey reported harassment on social media, a substantial number even after accounting for selection bias in the individuals who chose to respond to the survey. Although most of the attacks (88%) resulted from the respondent’s advocacy online, nearly half the attacks (45%) were gender based, 27% were based on race/ethnicity, and 13% were based on sexual orientation.

While hateful comments are likely the most common type of online harassment, other types can involve sharing or tagging your profile, creating fake profiles to misrepresent you, fake reviews of your practice, harassing phone calls and hate mail at your office, and doxxing, in which someone online widely shares your personal address, phone number, email, or other contact information.

Despite the risks of all these forms of harassment, Dr. Baldwin emphasized the value of doctors having a social media presence given how much misinformation thrives online. For example, a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed how many people weren’t sure whether certain health misinformation claims were true or false. Barely a third of people were sure that COVID-19 vaccines had not caused thousands of deaths in healthy people, and only 22% of people were sure that ivermectin is not an effective treatment for COVID.

“There is so much that we need to be doing and working in these spaces to put evidence-based content out there so that people are not finding all of this crap from everybody else,” Dr. Baldwin said. Having an online presence is particularly important given that the public still has high levels of trust in their doctors, she added.

“They trust their physician, and you may not be their physician online, but I will tell you from experience, when you build a community of followers, you become that trusted source of information for them, and it is so important,” Dr. Baldwin said. “There is room for everybody in this space, and we need all of you.”

Proactive steps for protection

Dr. Baldwin then went through the details of what people should do now to make things easier in the event of an attack later. “The best defense is a good offense,” Dr. Baldwin said, “so make sure all of your accounts are secure.”

She recommended the following steps:

- Use two-factor authentication for all of your logins.

- Use strong, unique passwords for all of your logins.

- Use strong privacy settings on all of your private social media profiles, such as making sure photos are not visible on your personal Facebook account.

- Claim your Google profile and Yelp business profile.

- Claim your doctor and/or business profile on all of the medical review sites where you have one, including Google, Healthgrades, Vitals, RateMDs, and WebMD.

For doctors who are attacked specifically because of pro-vaccine advocacy, Dr. Baldwin recommended contacting Shots Heard Round The World, a site that was created by a physician whose practice was attacked by anti-vaccine activists. The site also has a toolkit that anyone can download for tips on preparing ahead for possible attacks and what to do if you are attacked.

Dr. Baldwin then reviewed how to set up different social media profiles to automatically hide certain comments, including comments with words commonly used by online harassers and trolls:

- Sheep

- Sheeple

- Pharma

- Shill

- Die

- Psychopath

- Clown

- Various curse words

- The clown emoji

In Instagram, go to “Settings and privacy —> Hidden Words” for options on hiding offensive comments and messages and for managing custom words and phrases that should be automatically hidden.

On Facebook, go to “Professional dashboard —> Moderation Assist,” where you can add or edit criteria to automatically hide comments on your Facebook page. In addition to hiding comments with certain keywords, you can hide comments from new accounts, accounts without profile photos, or accounts with no friends or followers.

On TikTok, click the three-line menu icon in the upper right, and choose “Privacy —> Comments —> Filter keywords.”

On the platform formerly known as Twitter, go to “Settings and privacy —> Privacy and safety —> Mute and block —> Muted words.”

On YouTube, under “Manage your community & comments,” select “Learn about comment settings.”

Dr. Baldwin did not discourage doctors from posting about controversial topics, but she said it’s important to know what they are so that you can be prepared for the possibility that a post about one of these topics could lead to online harassment. These hot button topics include vaccines, firearm safety, gender-affirming care, reproductive choice, safe sleep/bedsharing, breastfeeding, and COVID masks.

If you do post on one of these and suspect it could result in harassment, Dr. Baldwin recommends turning on your notifications so you know when attacks begin, alerting your office and call center staff if you think they might receive calls, and, when possible, post your content at a time when you’re more likely to be able to monitor the post. She acknowledged that this last tip isn’t always relevant since attacks can take a few days to start or gain steam.

Defending yourself in an attack

Even after taking all these precautions, it’s not possible to altogether prevent an attack from happening, so Dr. Baldwin provided suggestions on what to do if one occurs, starting with taking a deep breath.

“If you are attacked, first of all, please remain calm, which is a lot easier said than done,” she said. “But know that this too shall pass. These things do come to an end.”

She advises you to get help if you need it, enlisting friends or colleagues to help with moderation and banning/blocking. If necessary, alert your employer to the attack, as attackers may contact your employer. Some people may opt to turn off comments on their post, but doing so “is a really personal decision,” she said. It’s okay to turn off comments if you don’t have the bandwidth or help to deal with them.

However, Dr. Baldwin said she never turns off comments because she wants to be able to ban and block people to reduce the likelihood of a future attack from them, and each comment brings the post higher in the algorithm so that more people are able to see the original content. “So sometimes these things are actually a blessing in disguise,” she said.

If you do have comments turned on, take screenshots of the most egregious or threatening ones and then report them and ban/block them. The screenshots are evidence since blocking will remove the comment.

“Take breaks when you need to,” she said. “Don’t stay up all night” since there are only going to be more in the morning, and if you’re using keywords to help hide many of these comments, that will hide them from your followers while you’re away. She also advised monitoring your online reviews at doctor/practice review sites so you know whether you’re receiving spurious reviews that need to be removed.

Dr. Baldwin also addressed how to handle trolls, the people online who intentionally antagonize others with inflammatory, irrelevant, offensive, or otherwise disruptive comments or content. The No. 1 rule is not to engage – “Don’t feed the trolls” – but Dr. Baldwin acknowledged that she can find that difficult sometimes. So she uses kindness or humor to defuse them or calls them out on their inaccurate information and then thanks them for their engagement. Don’t forget that you are in charge of your own page, so any complaints about “censorship” or infringing “free speech” aren’t relevant.

If the comments are growing out of control and you’re unable to manage them, multiple social media platforms have options for limited interactions or who can comment on your page.

On Instagram under “Settings and privacy,” check out “Limited interactions,” “Comments —> Allow comments from,” and “Tags and mentions” to see ways you can limit who is able to comment, tag or mention your account. If you need a complete break, you can turn off commenting by clicking the three dots in the upper right corner of the post, or make your account temporarily private under “Settings and privacy —> Account privacy.”

On Facebook, click the three dots in the upper right corner of posts to select “Who can comment on your post?” Also, under “Settings —> Privacy —> Your Activity,” you can adjust who sees your future posts. Again, if things are out of control, you can temporarily deactivate your page under “Settings —> Privacy —> Facebook Page information.”

On TikTok, click the three lines in the upper right corner of your profile and select “Privacy —> Comments” to adjust who can comment and to filter comments. Again, you can make your account private under “Settings and privacy —> Privacy —> Private account.”

On the platform formerly known as Twitter, click the three dots in the upper right corner of the tweet to change who can reply to the tweet. If you select “Only people you mentioned,” then no one can reply if you did not mention anyone. You can control tagging under “Settings and privacy —> Privacy and safety —> Audience and tagging.”

If you or your practice receive false reviews on review sites, report the reviews and alert the rating site when you can. In the meantime, lock down your private social media accounts and ensure that no photos of your family are publicly available.

Social media self-care

Dr. Baldwin acknowledged that experiencing a social media attack can be intense and even frightening, but it’s rare and outweighed by the “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of positive comments all the time.” She also reminded attendees that being on social media doesn’t mean being there all the time.

“Over time, my use of social media has certainly changed. It ebbs and flows,” she said. “There are times when I have a lot of bandwidth and I’m posting a lot, and then I actually have had some struggles with my own mental health, with some anxiety and mild depression, so I took a break from social media for a while. When I came back, I posted about my mental health struggles, and you wouldn’t believe how many people were so appreciative of that.”

Accurate information from a trusted source

Ultimately, Dr. Baldwin sees her work online as an extension of her work educating patients.

“This is where our patients are. They are in your office for maybe 10-15 minutes maybe once a year, but they are on these platforms every single day for hours,” she said. “They need to see this information from medical professionals because there are random people out there that are telling them [misinformation].”

Elizabeth Murray, DO, MBA, an emergency medicine pediatrician at Golisano Children’s Hospital at the University of Rochester, agreed that there’s substantial value in doctors sharing accurate information online.

“Disinformation and misinformation is rampant, and at the end of the day, we know the facts,” Dr. Murray said. “We know what parents want to hear and what they want to learn about, so we need to share that information and get the facts out there.”

Dr. Murray found the session very helpful because there’s so much to learn across different social media platforms and it can feel overwhelming if you aren’t familiar with the tools.

“Social media is always going to be here. We need to learn to live with all of these platforms,” Dr. Murray said. “That’s a skill set. We need to learn the skills and teach our kids the skill set. You never really know what you might put out there that, in your mind is innocent or very science-based, that for whatever reason somebody might take issue with. You might as well be ready because we’re all about prevention in pediatrics.”

There were no funders for the presentation. Dr. Baldwin and Dr. Murray had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – The entire video clip is just 15 seconds — 15 seconds that went viral and temporarily upended the entire life and disrupted the medical practice of Nicole Baldwin, MD, a pediatrician in Cincinnati, Ohio, in January 2020. At the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Dr. Baldwin told attendees how her pro-vaccine TikTok video led a horde of anti-vaccine activists to swarm her social media profiles across multiple platforms, leave one-star reviews with false stories about her medical practice on various doctor review sites, and personally threaten her.

The initial response to the video was positive, with 50,000 views in the first 24 hours after the video was posted and more than 1.5 million views the next day. But 2 days after the video was posted, an organized attack that originated on Facebook required Dr. Baldwin to enlist the help of 16 volunteers, working 24/7 for a week, to help ban and block more than 6,000 users on Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok. Just 4 days after she’d posted the video, Dr. Baldwin was reporting personal threats to the police and had begun contacting sites such as Yelp, Google, Healthgrades, Vitals, RateMDs, and WebMD so they could start removing false reviews about her practice.

Today, years after those 2 exhausting, intense weeks of attacks, Dr. Baldwin has found two silver linings in the experience: More people have found her profiles, allowing her to share evidence-based information with an even wider audience, and she can now help other physicians protect themselves and reduce the risk of similar attacks, or at least know how to respond to them if they occur. Dr. Baldwin shared a wealth of tips and resources during her lecture to help pediatricians prepare ahead for the possibility that they will be targeted next, whether the issue is vaccines or another topic.

Online risks and benefits

A Pew survey of U.S. adults in September 2020 found that 41% have personally experienced online harassment, including a quarter of Americans who have experienced severe harassment. More than half of respondents said online harassment and bullying is a major problem – and that was a poll of the entire population, not even just physicians and scientists.

“Now, these numbers would be higher,” Dr. Baldwin said. “A lot has changed in the past 3 years, and the landscape is very different.”

The pandemic contributed to those changes to the landscape, including an increase in harassment of doctors and researchers. A June 2023 study revealed that two-thirds of 359 respondents in an online survey reported harassment on social media, a substantial number even after accounting for selection bias in the individuals who chose to respond to the survey. Although most of the attacks (88%) resulted from the respondent’s advocacy online, nearly half the attacks (45%) were gender based, 27% were based on race/ethnicity, and 13% were based on sexual orientation.

While hateful comments are likely the most common type of online harassment, other types can involve sharing or tagging your profile, creating fake profiles to misrepresent you, fake reviews of your practice, harassing phone calls and hate mail at your office, and doxxing, in which someone online widely shares your personal address, phone number, email, or other contact information.

Despite the risks of all these forms of harassment, Dr. Baldwin emphasized the value of doctors having a social media presence given how much misinformation thrives online. For example, a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed how many people weren’t sure whether certain health misinformation claims were true or false. Barely a third of people were sure that COVID-19 vaccines had not caused thousands of deaths in healthy people, and only 22% of people were sure that ivermectin is not an effective treatment for COVID.

“There is so much that we need to be doing and working in these spaces to put evidence-based content out there so that people are not finding all of this crap from everybody else,” Dr. Baldwin said. Having an online presence is particularly important given that the public still has high levels of trust in their doctors, she added.

“They trust their physician, and you may not be their physician online, but I will tell you from experience, when you build a community of followers, you become that trusted source of information for them, and it is so important,” Dr. Baldwin said. “There is room for everybody in this space, and we need all of you.”

Proactive steps for protection

Dr. Baldwin then went through the details of what people should do now to make things easier in the event of an attack later. “The best defense is a good offense,” Dr. Baldwin said, “so make sure all of your accounts are secure.”

She recommended the following steps:

- Use two-factor authentication for all of your logins.

- Use strong, unique passwords for all of your logins.

- Use strong privacy settings on all of your private social media profiles, such as making sure photos are not visible on your personal Facebook account.

- Claim your Google profile and Yelp business profile.

- Claim your doctor and/or business profile on all of the medical review sites where you have one, including Google, Healthgrades, Vitals, RateMDs, and WebMD.

For doctors who are attacked specifically because of pro-vaccine advocacy, Dr. Baldwin recommended contacting Shots Heard Round The World, a site that was created by a physician whose practice was attacked by anti-vaccine activists. The site also has a toolkit that anyone can download for tips on preparing ahead for possible attacks and what to do if you are attacked.

Dr. Baldwin then reviewed how to set up different social media profiles to automatically hide certain comments, including comments with words commonly used by online harassers and trolls:

- Sheep

- Sheeple

- Pharma

- Shill

- Die

- Psychopath

- Clown

- Various curse words

- The clown emoji

In Instagram, go to “Settings and privacy —> Hidden Words” for options on hiding offensive comments and messages and for managing custom words and phrases that should be automatically hidden.

On Facebook, go to “Professional dashboard —> Moderation Assist,” where you can add or edit criteria to automatically hide comments on your Facebook page. In addition to hiding comments with certain keywords, you can hide comments from new accounts, accounts without profile photos, or accounts with no friends or followers.

On TikTok, click the three-line menu icon in the upper right, and choose “Privacy —> Comments —> Filter keywords.”

On the platform formerly known as Twitter, go to “Settings and privacy —> Privacy and safety —> Mute and block —> Muted words.”

On YouTube, under “Manage your community & comments,” select “Learn about comment settings.”

Dr. Baldwin did not discourage doctors from posting about controversial topics, but she said it’s important to know what they are so that you can be prepared for the possibility that a post about one of these topics could lead to online harassment. These hot button topics include vaccines, firearm safety, gender-affirming care, reproductive choice, safe sleep/bedsharing, breastfeeding, and COVID masks.

If you do post on one of these and suspect it could result in harassment, Dr. Baldwin recommends turning on your notifications so you know when attacks begin, alerting your office and call center staff if you think they might receive calls, and, when possible, post your content at a time when you’re more likely to be able to monitor the post. She acknowledged that this last tip isn’t always relevant since attacks can take a few days to start or gain steam.

Defending yourself in an attack

Even after taking all these precautions, it’s not possible to altogether prevent an attack from happening, so Dr. Baldwin provided suggestions on what to do if one occurs, starting with taking a deep breath.

“If you are attacked, first of all, please remain calm, which is a lot easier said than done,” she said. “But know that this too shall pass. These things do come to an end.”

She advises you to get help if you need it, enlisting friends or colleagues to help with moderation and banning/blocking. If necessary, alert your employer to the attack, as attackers may contact your employer. Some people may opt to turn off comments on their post, but doing so “is a really personal decision,” she said. It’s okay to turn off comments if you don’t have the bandwidth or help to deal with them.

However, Dr. Baldwin said she never turns off comments because she wants to be able to ban and block people to reduce the likelihood of a future attack from them, and each comment brings the post higher in the algorithm so that more people are able to see the original content. “So sometimes these things are actually a blessing in disguise,” she said.

If you do have comments turned on, take screenshots of the most egregious or threatening ones and then report them and ban/block them. The screenshots are evidence since blocking will remove the comment.

“Take breaks when you need to,” she said. “Don’t stay up all night” since there are only going to be more in the morning, and if you’re using keywords to help hide many of these comments, that will hide them from your followers while you’re away. She also advised monitoring your online reviews at doctor/practice review sites so you know whether you’re receiving spurious reviews that need to be removed.

Dr. Baldwin also addressed how to handle trolls, the people online who intentionally antagonize others with inflammatory, irrelevant, offensive, or otherwise disruptive comments or content. The No. 1 rule is not to engage – “Don’t feed the trolls” – but Dr. Baldwin acknowledged that she can find that difficult sometimes. So she uses kindness or humor to defuse them or calls them out on their inaccurate information and then thanks them for their engagement. Don’t forget that you are in charge of your own page, so any complaints about “censorship” or infringing “free speech” aren’t relevant.

If the comments are growing out of control and you’re unable to manage them, multiple social media platforms have options for limited interactions or who can comment on your page.

On Instagram under “Settings and privacy,” check out “Limited interactions,” “Comments —> Allow comments from,” and “Tags and mentions” to see ways you can limit who is able to comment, tag or mention your account. If you need a complete break, you can turn off commenting by clicking the three dots in the upper right corner of the post, or make your account temporarily private under “Settings and privacy —> Account privacy.”

On Facebook, click the three dots in the upper right corner of posts to select “Who can comment on your post?” Also, under “Settings —> Privacy —> Your Activity,” you can adjust who sees your future posts. Again, if things are out of control, you can temporarily deactivate your page under “Settings —> Privacy —> Facebook Page information.”

On TikTok, click the three lines in the upper right corner of your profile and select “Privacy —> Comments” to adjust who can comment and to filter comments. Again, you can make your account private under “Settings and privacy —> Privacy —> Private account.”

On the platform formerly known as Twitter, click the three dots in the upper right corner of the tweet to change who can reply to the tweet. If you select “Only people you mentioned,” then no one can reply if you did not mention anyone. You can control tagging under “Settings and privacy —> Privacy and safety —> Audience and tagging.”

If you or your practice receive false reviews on review sites, report the reviews and alert the rating site when you can. In the meantime, lock down your private social media accounts and ensure that no photos of your family are publicly available.

Social media self-care

Dr. Baldwin acknowledged that experiencing a social media attack can be intense and even frightening, but it’s rare and outweighed by the “hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of positive comments all the time.” She also reminded attendees that being on social media doesn’t mean being there all the time.

“Over time, my use of social media has certainly changed. It ebbs and flows,” she said. “There are times when I have a lot of bandwidth and I’m posting a lot, and then I actually have had some struggles with my own mental health, with some anxiety and mild depression, so I took a break from social media for a while. When I came back, I posted about my mental health struggles, and you wouldn’t believe how many people were so appreciative of that.”

Accurate information from a trusted source

Ultimately, Dr. Baldwin sees her work online as an extension of her work educating patients.

“This is where our patients are. They are in your office for maybe 10-15 minutes maybe once a year, but they are on these platforms every single day for hours,” she said. “They need to see this information from medical professionals because there are random people out there that are telling them [misinformation].”

Elizabeth Murray, DO, MBA, an emergency medicine pediatrician at Golisano Children’s Hospital at the University of Rochester, agreed that there’s substantial value in doctors sharing accurate information online.

“Disinformation and misinformation is rampant, and at the end of the day, we know the facts,” Dr. Murray said. “We know what parents want to hear and what they want to learn about, so we need to share that information and get the facts out there.”

Dr. Murray found the session very helpful because there’s so much to learn across different social media platforms and it can feel overwhelming if you aren’t familiar with the tools.

“Social media is always going to be here. We need to learn to live with all of these platforms,” Dr. Murray said. “That’s a skill set. We need to learn the skills and teach our kids the skill set. You never really know what you might put out there that, in your mind is innocent or very science-based, that for whatever reason somebody might take issue with. You might as well be ready because we’re all about prevention in pediatrics.”

There were no funders for the presentation. Dr. Baldwin and Dr. Murray had no disclosures.

AT AAP 2023

New meningococcal vaccine wins FDA approval

The new formulation called Penbraya is manufactured by Pfizer and combines the components from two existing meningococcal vaccines, Trumenba the group B vaccine and Nimenrix groups A, C, W-135, and Y conjugate vaccine.

This is the first pentavalent vaccine for meningococcal disease and is approved for use in people aged 10-25.

“Today marks an important step forward in the prevention of meningococcal disease in the U.S.,” Annaliesa Anderson, PhD, head of vaccine research and development at Pfizer, said in a news release. “In a single vaccine, Penbraya has the potential to protect more adolescents and young adults from this severe and unpredictable disease by providing the broadest meningococcal coverage in the fewest shots.”

One shot, five common types

“Incomplete protection against invasive meningococcal disease,” is common, added Jana Shaw, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist from Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y. Reducing the number of shots is important because streamlining the vaccination process should help increase the number of young people who get fully vaccinated against meningococcal disease.

Rates are low in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in 2021 there were around 210 cases reported. But a statewide outbreak has been going on in Virginia since June 2022, with 29 confirmed cases and 6 deaths.

The FDA’s decision is based on the positive results from phase 2 and phase 3 trials, including a randomized, active-controlled and observer-blinded phase 3 trial assessing the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the pentavalent vaccine candidate, compared with currently licensed meningococcal vaccines. The phase 3 trial evaluated more than 2,400 patients from the United States and Europe.

The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is meeting on Oct. 25 to discuss recommendations for the appropriate use of Penbraya in young people.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new formulation called Penbraya is manufactured by Pfizer and combines the components from two existing meningococcal vaccines, Trumenba the group B vaccine and Nimenrix groups A, C, W-135, and Y conjugate vaccine.

This is the first pentavalent vaccine for meningococcal disease and is approved for use in people aged 10-25.

“Today marks an important step forward in the prevention of meningococcal disease in the U.S.,” Annaliesa Anderson, PhD, head of vaccine research and development at Pfizer, said in a news release. “In a single vaccine, Penbraya has the potential to protect more adolescents and young adults from this severe and unpredictable disease by providing the broadest meningococcal coverage in the fewest shots.”

One shot, five common types

“Incomplete protection against invasive meningococcal disease,” is common, added Jana Shaw, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist from Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y. Reducing the number of shots is important because streamlining the vaccination process should help increase the number of young people who get fully vaccinated against meningococcal disease.

Rates are low in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in 2021 there were around 210 cases reported. But a statewide outbreak has been going on in Virginia since June 2022, with 29 confirmed cases and 6 deaths.

The FDA’s decision is based on the positive results from phase 2 and phase 3 trials, including a randomized, active-controlled and observer-blinded phase 3 trial assessing the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the pentavalent vaccine candidate, compared with currently licensed meningococcal vaccines. The phase 3 trial evaluated more than 2,400 patients from the United States and Europe.

The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is meeting on Oct. 25 to discuss recommendations for the appropriate use of Penbraya in young people.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new formulation called Penbraya is manufactured by Pfizer and combines the components from two existing meningococcal vaccines, Trumenba the group B vaccine and Nimenrix groups A, C, W-135, and Y conjugate vaccine.

This is the first pentavalent vaccine for meningococcal disease and is approved for use in people aged 10-25.

“Today marks an important step forward in the prevention of meningococcal disease in the U.S.,” Annaliesa Anderson, PhD, head of vaccine research and development at Pfizer, said in a news release. “In a single vaccine, Penbraya has the potential to protect more adolescents and young adults from this severe and unpredictable disease by providing the broadest meningococcal coverage in the fewest shots.”

One shot, five common types

“Incomplete protection against invasive meningococcal disease,” is common, added Jana Shaw, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist from Upstate Golisano Children’s Hospital in Syracuse, N.Y. Reducing the number of shots is important because streamlining the vaccination process should help increase the number of young people who get fully vaccinated against meningococcal disease.

Rates are low in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in 2021 there were around 210 cases reported. But a statewide outbreak has been going on in Virginia since June 2022, with 29 confirmed cases and 6 deaths.

The FDA’s decision is based on the positive results from phase 2 and phase 3 trials, including a randomized, active-controlled and observer-blinded phase 3 trial assessing the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the pentavalent vaccine candidate, compared with currently licensed meningococcal vaccines. The phase 3 trial evaluated more than 2,400 patients from the United States and Europe.

The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices is meeting on Oct. 25 to discuss recommendations for the appropriate use of Penbraya in young people.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

News & Perspectives from Ob.Gyn. News

COMMENTARY

The safety of vaginal estrogen in breast cancer survivors

Currently, more than 3.8 million breast cancer survivors reside in the United States, reflecting high prevalence as well as cure rates for this common malignancy.

When over-the-counter measures including vaginal lubricants and moisturizers are not adequate, vaginal estrogen may be a highly effective treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), a common condition associated with hypoestrogenism that impairs sexual function and quality of life.

Use of vaginal formulations does not result in systemic levels of estrogen above the normal postmenopausal range. Nonetheless, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists a history of breast cancer as a contraindication to the use of all systemic as well as vaginal estrogens.

In premenopausal women, chemotherapy for breast cancer often results in early menopause. Aromatase inhibitors, although effective in preventing recurrent disease in menopausal women, exacerbate GSM. These factors result in a high prevalence of GSM in breast cancer survivors.

Because the safety of vaginal estrogen in the setting of breast cancer is uncertain, investigators at Johns Hopkins conducted a cohort study using claims-based data from more than 200 million U.S. patients that identified women with GSM who had previously been diagnosed with breast cancer. Among some 42,000 women diagnosed with GSM after breast cancer, 5% had three or more prescriptions and were considered vaginal estrogen users.

No significant differences were noted in recurrence-free survival between the vaginal estrogen group and the no estrogen group. At 5 and 10 years of follow-up, use of vaginal estrogen was not associated with higher all-cause mortality. Among women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, risk for breast cancer recurrence was similar between estrogen users and nonusers.

LATEST NEWS

Older women who get mammograms risk overdiagnosis

TOPLINE:

Women who continue breast cancer screening after age 70 face a considerable risk for overdiagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overdiagnosis – the risk of detecting and treating cancers that would never have caused issues in a person’s lifetime – is increasingly recognized as a harm of breast cancer screening; however, the scope of the problem among older women remains uncertain.

- To get an idea, investigators linked Medicare claims data with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for 54,635 women 70 years or older to compare the incidence of breast cancer and breast cancer–specific death among women who continued screening mammography with those who did not.

- The women all had undergone recent screening mammograms and had no history of breast cancer at study entry. Those who had a subsequent mammogram within 3 years were classified as undergoing continued screening while those who did not were classified as not undergoing continued screening.

- Overdiagnosis was defined as the difference in cumulative incidence of breast cancer between screened and unscreened women divided by the cumulative incidence among screened women.

- Results were adjusted for potential confounders, including age, race, and ethnicity.

Continue to: TAKEAWAY...

TAKEAWAY:

- Over 80% of women 70-84 years old and more than 60% of women 85 years or older continued screening.

- Among women 70-74 years old, the adjusted cumulative incidence of breast cancer was 6.1 cases per 100 screened women vs. 4.2 cases per 100 unscreened women; for women aged 75-84 years old, the cumulative incidence was 4.9 per 100 screened women vs. 2.6 per 100 unscreened women, and for women 85 years and older, the cumulative incidence was 2.8 vs. 1.3 per 100, respectively.

- Estimates of overdiagnosis ranged from 31% of breast cancer cases among screened women in the 70-74 age group to 54% of cases in the 85 and older group.

- The researchers found no statistically significant reduction in breast cancer–specific death associated with screening in any age or life-expectancy group. Overdiagnosis appeared to be driven by in situ and localized invasive breast cancer, not advanced breast cancer.

IN PRACTICE:

The proportion of older women who continue to receive screening mammograms and may experience breast cancer overdiagnosis is “considerable” and “increases with advancing age and with decreasing life expectancy,” the authors conclude. Given potential benefits and harms of screening in this population, “patient preferences, including risk tolerance, comfort with uncertainty, and willingness to undergo treatment, are important for informing screening decisions.”

SOURCE: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M23-0133

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/latest-news

CONFERENCE COVERAGE

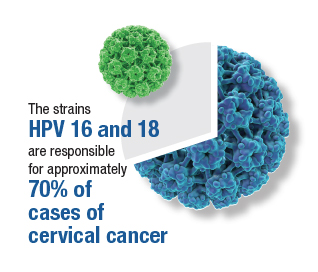

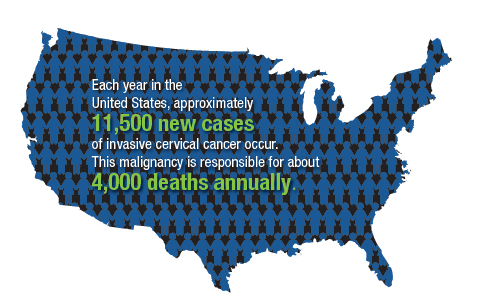

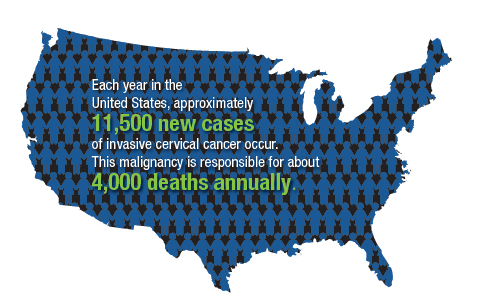

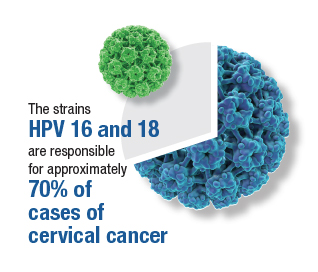

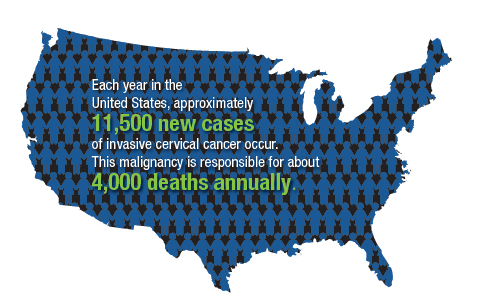

Offering HPV vaccine at age 9 linked to greater series completion

BALTIMORE—Receiving the first dose of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine at age 9, rather than bundling it with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines, appears to increase the likelihood that children will complete the HPV vaccine series, according to a retrospective cohort study of commercially insured youth presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The research was published ahead of print in Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics.

“These findings are novel because they emphasize starting at age 9, and that is different than prior studies that emphasize bundling of these vaccines,” Kevin Ault, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine and a former member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, said in an interview.

Dr. Ault was not involved in the study but noted that these findings support the AAP’s recommendation to start the HPV vaccine series at age 9. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends giving the first dose of the HPV vaccine at ages 11-12, at the same time as the Tdap and meningitis vaccines. This recommendation to “bundle” the HPV vaccine with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines aims to facilitate provider-family discussion about the HPV vaccine, ideally reducing parent hesitancy and concerns about the vaccines. Multiple studies have shown improved HPV vaccine uptake when providers offer the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap and meningococcal vaccines.

However, shifts in parents’ attitudes have occurred toward the HPV vaccine since those studies on bundling: Concerns about sexual activity have receded while concerns about safety remain high. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society both advise starting the HPV vaccine series at age 9, based on evidence showing that more children complete the series when they get the first shot before age 11 compared to getting it at 11 or 12.

COMMENTARY

The safety of vaginal estrogen in breast cancer survivors

Currently, more than 3.8 million breast cancer survivors reside in the United States, reflecting high prevalence as well as cure rates for this common malignancy.

When over-the-counter measures including vaginal lubricants and moisturizers are not adequate, vaginal estrogen may be a highly effective treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), a common condition associated with hypoestrogenism that impairs sexual function and quality of life.

Use of vaginal formulations does not result in systemic levels of estrogen above the normal postmenopausal range. Nonetheless, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists a history of breast cancer as a contraindication to the use of all systemic as well as vaginal estrogens.

In premenopausal women, chemotherapy for breast cancer often results in early menopause. Aromatase inhibitors, although effective in preventing recurrent disease in menopausal women, exacerbate GSM. These factors result in a high prevalence of GSM in breast cancer survivors.

Because the safety of vaginal estrogen in the setting of breast cancer is uncertain, investigators at Johns Hopkins conducted a cohort study using claims-based data from more than 200 million U.S. patients that identified women with GSM who had previously been diagnosed with breast cancer. Among some 42,000 women diagnosed with GSM after breast cancer, 5% had three or more prescriptions and were considered vaginal estrogen users.

No significant differences were noted in recurrence-free survival between the vaginal estrogen group and the no estrogen group. At 5 and 10 years of follow-up, use of vaginal estrogen was not associated with higher all-cause mortality. Among women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, risk for breast cancer recurrence was similar between estrogen users and nonusers.

LATEST NEWS

Older women who get mammograms risk overdiagnosis

TOPLINE:

Women who continue breast cancer screening after age 70 face a considerable risk for overdiagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overdiagnosis – the risk of detecting and treating cancers that would never have caused issues in a person’s lifetime – is increasingly recognized as a harm of breast cancer screening; however, the scope of the problem among older women remains uncertain.

- To get an idea, investigators linked Medicare claims data with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for 54,635 women 70 years or older to compare the incidence of breast cancer and breast cancer–specific death among women who continued screening mammography with those who did not.

- The women all had undergone recent screening mammograms and had no history of breast cancer at study entry. Those who had a subsequent mammogram within 3 years were classified as undergoing continued screening while those who did not were classified as not undergoing continued screening.

- Overdiagnosis was defined as the difference in cumulative incidence of breast cancer between screened and unscreened women divided by the cumulative incidence among screened women.

- Results were adjusted for potential confounders, including age, race, and ethnicity.

Continue to: TAKEAWAY...

TAKEAWAY:

- Over 80% of women 70-84 years old and more than 60% of women 85 years or older continued screening.

- Among women 70-74 years old, the adjusted cumulative incidence of breast cancer was 6.1 cases per 100 screened women vs. 4.2 cases per 100 unscreened women; for women aged 75-84 years old, the cumulative incidence was 4.9 per 100 screened women vs. 2.6 per 100 unscreened women, and for women 85 years and older, the cumulative incidence was 2.8 vs. 1.3 per 100, respectively.

- Estimates of overdiagnosis ranged from 31% of breast cancer cases among screened women in the 70-74 age group to 54% of cases in the 85 and older group.

- The researchers found no statistically significant reduction in breast cancer–specific death associated with screening in any age or life-expectancy group. Overdiagnosis appeared to be driven by in situ and localized invasive breast cancer, not advanced breast cancer.

IN PRACTICE:

The proportion of older women who continue to receive screening mammograms and may experience breast cancer overdiagnosis is “considerable” and “increases with advancing age and with decreasing life expectancy,” the authors conclude. Given potential benefits and harms of screening in this population, “patient preferences, including risk tolerance, comfort with uncertainty, and willingness to undergo treatment, are important for informing screening decisions.”

SOURCE: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M23-0133

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/latest-news

CONFERENCE COVERAGE

Offering HPV vaccine at age 9 linked to greater series completion

BALTIMORE—Receiving the first dose of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine at age 9, rather than bundling it with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines, appears to increase the likelihood that children will complete the HPV vaccine series, according to a retrospective cohort study of commercially insured youth presented at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The research was published ahead of print in Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics.

“These findings are novel because they emphasize starting at age 9, and that is different than prior studies that emphasize bundling of these vaccines,” Kevin Ault, MD, professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine and a former member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, said in an interview.

Dr. Ault was not involved in the study but noted that these findings support the AAP’s recommendation to start the HPV vaccine series at age 9. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends giving the first dose of the HPV vaccine at ages 11-12, at the same time as the Tdap and meningitis vaccines. This recommendation to “bundle” the HPV vaccine with the Tdap and meningitis vaccines aims to facilitate provider-family discussion about the HPV vaccine, ideally reducing parent hesitancy and concerns about the vaccines. Multiple studies have shown improved HPV vaccine uptake when providers offer the HPV vaccine at the same time as the Tdap and meningococcal vaccines.

However, shifts in parents’ attitudes have occurred toward the HPV vaccine since those studies on bundling: Concerns about sexual activity have receded while concerns about safety remain high. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Cancer Society both advise starting the HPV vaccine series at age 9, based on evidence showing that more children complete the series when they get the first shot before age 11 compared to getting it at 11 or 12.

COMMENTARY

The safety of vaginal estrogen in breast cancer survivors

Currently, more than 3.8 million breast cancer survivors reside in the United States, reflecting high prevalence as well as cure rates for this common malignancy.

When over-the-counter measures including vaginal lubricants and moisturizers are not adequate, vaginal estrogen may be a highly effective treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), a common condition associated with hypoestrogenism that impairs sexual function and quality of life.

Use of vaginal formulations does not result in systemic levels of estrogen above the normal postmenopausal range. Nonetheless, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists a history of breast cancer as a contraindication to the use of all systemic as well as vaginal estrogens.

In premenopausal women, chemotherapy for breast cancer often results in early menopause. Aromatase inhibitors, although effective in preventing recurrent disease in menopausal women, exacerbate GSM. These factors result in a high prevalence of GSM in breast cancer survivors.

Because the safety of vaginal estrogen in the setting of breast cancer is uncertain, investigators at Johns Hopkins conducted a cohort study using claims-based data from more than 200 million U.S. patients that identified women with GSM who had previously been diagnosed with breast cancer. Among some 42,000 women diagnosed with GSM after breast cancer, 5% had three or more prescriptions and were considered vaginal estrogen users.

No significant differences were noted in recurrence-free survival between the vaginal estrogen group and the no estrogen group. At 5 and 10 years of follow-up, use of vaginal estrogen was not associated with higher all-cause mortality. Among women with estrogen receptor–positive tumors, risk for breast cancer recurrence was similar between estrogen users and nonusers.

LATEST NEWS

Older women who get mammograms risk overdiagnosis

TOPLINE:

Women who continue breast cancer screening after age 70 face a considerable risk for overdiagnosis.

METHODOLOGY:

- Overdiagnosis – the risk of detecting and treating cancers that would never have caused issues in a person’s lifetime – is increasingly recognized as a harm of breast cancer screening; however, the scope of the problem among older women remains uncertain.

- To get an idea, investigators linked Medicare claims data with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data for 54,635 women 70 years or older to compare the incidence of breast cancer and breast cancer–specific death among women who continued screening mammography with those who did not.

- The women all had undergone recent screening mammograms and had no history of breast cancer at study entry. Those who had a subsequent mammogram within 3 years were classified as undergoing continued screening while those who did not were classified as not undergoing continued screening.

- Overdiagnosis was defined as the difference in cumulative incidence of breast cancer between screened and unscreened women divided by the cumulative incidence among screened women.

- Results were adjusted for potential confounders, including age, race, and ethnicity.

Continue to: TAKEAWAY...

TAKEAWAY:

- Over 80% of women 70-84 years old and more than 60% of women 85 years or older continued screening.

- Among women 70-74 years old, the adjusted cumulative incidence of breast cancer was 6.1 cases per 100 screened women vs. 4.2 cases per 100 unscreened women; for women aged 75-84 years old, the cumulative incidence was 4.9 per 100 screened women vs. 2.6 per 100 unscreened women, and for women 85 years and older, the cumulative incidence was 2.8 vs. 1.3 per 100, respectively.

- Estimates of overdiagnosis ranged from 31% of breast cancer cases among screened women in the 70-74 age group to 54% of cases in the 85 and older group.

- The researchers found no statistically significant reduction in breast cancer–specific death associated with screening in any age or life-expectancy group. Overdiagnosis appeared to be driven by in situ and localized invasive breast cancer, not advanced breast cancer.

IN PRACTICE:

The proportion of older women who continue to receive screening mammograms and may experience breast cancer overdiagnosis is “considerable” and “increases with advancing age and with decreasing life expectancy,” the authors conclude. Given potential benefits and harms of screening in this population, “patient preferences, including risk tolerance, comfort with uncertainty, and willingness to undergo treatment, are important for informing screening decisions.”

SOURCE: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M23-0133