User login

Large measles outbreak reported in Michigan

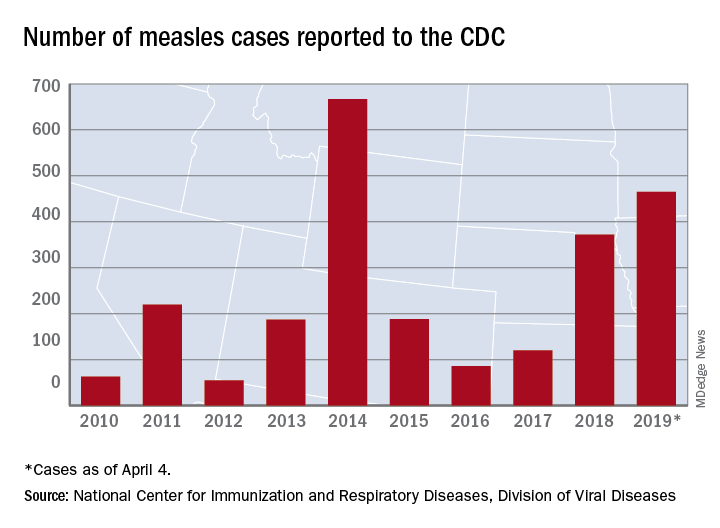

A new measles outbreak in Michigan has already resulted in 39 cases, and four more states reported their first cases of 2019 during the week ending April 4, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The measles virus has now infected individuals in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Nevada, which means that 19 states have now reported a total of 465 cases this year, and that is the second-highest total “reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000,” the CDC said April 8.

The Michigan outbreak is mostly concentrated in Oakland County, where 38 cases have occurred. The county has posted an up-to-date list of exposure locations.

Not to be outdone, New York reported 45 new cases last week: 44 in Brooklyn and 1 in Queens. There have been 259 confirmed cases in the two boroughs since the outbreak began in October of last year.

Besides Michigan and New York City, there are five other outbreaks ongoing in the United States: Rockland County, N.Y.; Washington State (no new cases since March 22); Butte County, Calif.; Santa Cruz County, Calif.; and New Jersey, the CDC reported.

A judge in New York State temporarily blocked an order banning unimmunized children from public spaces in Rockland County and has set a hearing date of April 19, CNN reported. The ban, ordered by Rockland County Executive Ed Day, went into effect on March 27.

On April 2, the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention announced that an out-of-state resident with a confirmed case of measles had visited two health care offices – one in Falmouth and one in Westbrook – on March 27. No cases in Maine residents have been reported yet.

On a vaccine-related note, the Washington State Senate’s Health and Long Term Care Committee approved a proposal on April 1 that would “end the personal exemption for parents who don’t want their children vaccinated against measles,” the Spokane Spokesman-Review said. The bill, which would still allow medical and religious exemptions, has already passed the state’s House of Representatives and goes next to the full senate.

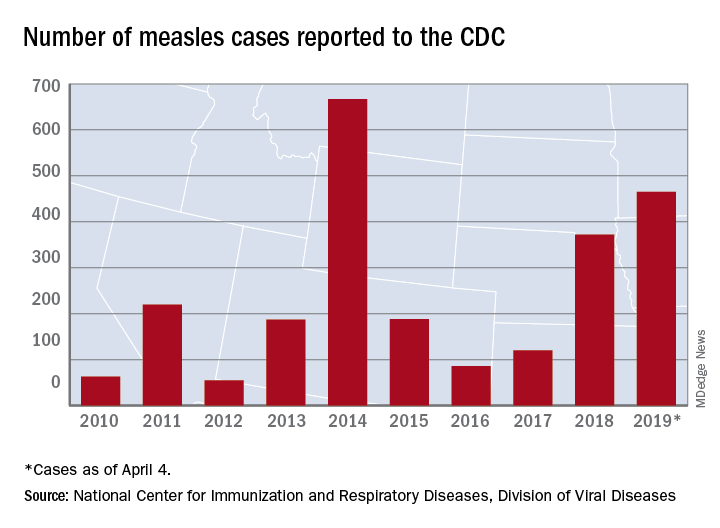

A new measles outbreak in Michigan has already resulted in 39 cases, and four more states reported their first cases of 2019 during the week ending April 4, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The measles virus has now infected individuals in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Nevada, which means that 19 states have now reported a total of 465 cases this year, and that is the second-highest total “reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000,” the CDC said April 8.

The Michigan outbreak is mostly concentrated in Oakland County, where 38 cases have occurred. The county has posted an up-to-date list of exposure locations.

Not to be outdone, New York reported 45 new cases last week: 44 in Brooklyn and 1 in Queens. There have been 259 confirmed cases in the two boroughs since the outbreak began in October of last year.

Besides Michigan and New York City, there are five other outbreaks ongoing in the United States: Rockland County, N.Y.; Washington State (no new cases since March 22); Butte County, Calif.; Santa Cruz County, Calif.; and New Jersey, the CDC reported.

A judge in New York State temporarily blocked an order banning unimmunized children from public spaces in Rockland County and has set a hearing date of April 19, CNN reported. The ban, ordered by Rockland County Executive Ed Day, went into effect on March 27.

On April 2, the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention announced that an out-of-state resident with a confirmed case of measles had visited two health care offices – one in Falmouth and one in Westbrook – on March 27. No cases in Maine residents have been reported yet.

On a vaccine-related note, the Washington State Senate’s Health and Long Term Care Committee approved a proposal on April 1 that would “end the personal exemption for parents who don’t want their children vaccinated against measles,” the Spokane Spokesman-Review said. The bill, which would still allow medical and religious exemptions, has already passed the state’s House of Representatives and goes next to the full senate.

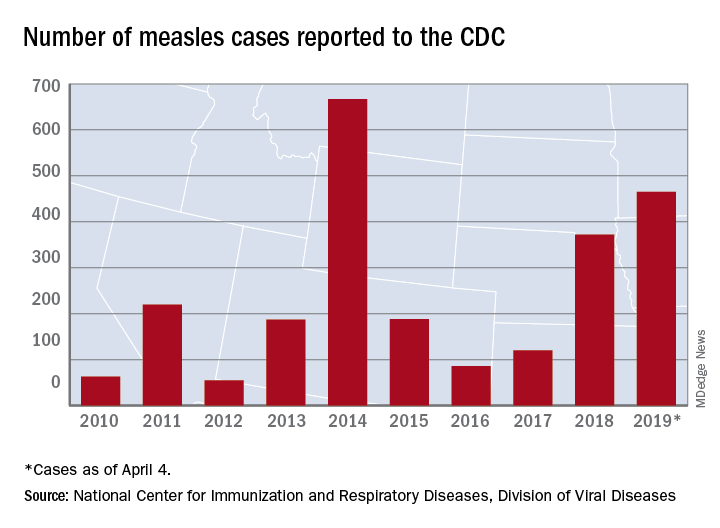

A new measles outbreak in Michigan has already resulted in 39 cases, and four more states reported their first cases of 2019 during the week ending April 4, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The measles virus has now infected individuals in Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Nevada, which means that 19 states have now reported a total of 465 cases this year, and that is the second-highest total “reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000,” the CDC said April 8.

The Michigan outbreak is mostly concentrated in Oakland County, where 38 cases have occurred. The county has posted an up-to-date list of exposure locations.

Not to be outdone, New York reported 45 new cases last week: 44 in Brooklyn and 1 in Queens. There have been 259 confirmed cases in the two boroughs since the outbreak began in October of last year.

Besides Michigan and New York City, there are five other outbreaks ongoing in the United States: Rockland County, N.Y.; Washington State (no new cases since March 22); Butte County, Calif.; Santa Cruz County, Calif.; and New Jersey, the CDC reported.

A judge in New York State temporarily blocked an order banning unimmunized children from public spaces in Rockland County and has set a hearing date of April 19, CNN reported. The ban, ordered by Rockland County Executive Ed Day, went into effect on March 27.

On April 2, the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention announced that an out-of-state resident with a confirmed case of measles had visited two health care offices – one in Falmouth and one in Westbrook – on March 27. No cases in Maine residents have been reported yet.

On a vaccine-related note, the Washington State Senate’s Health and Long Term Care Committee approved a proposal on April 1 that would “end the personal exemption for parents who don’t want their children vaccinated against measles,” the Spokane Spokesman-Review said. The bill, which would still allow medical and religious exemptions, has already passed the state’s House of Representatives and goes next to the full senate.

NIH to undertake first in-human trial of universal influenza vaccine

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, is launching the first in-human trial of a universal influenza vaccine candidate.

The experimental vaccine, H1ssF_3928, is derived from the stem of an H1N1 virus and has a surface made from hemagglutinin and ferritin. By including only the stem of the virus, which changes less than the head, the vaccine should require fewer updates. A similar vaccine made from the same materials was shown to be safe and well tolerated in humans.

The clinical trial (NCT03814720) will be conducted at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., and will gradually enroll at least 53 healthy adults aged 18-70 years. The first 5 participants will receive one 20-mcg intramuscular injection of the vaccine; the other 48 participants will receive two 60-mcg vaccinations 16 weeks apart. Patients will return for 9-11 follow-ups over a 12- to 15-month period, and will provide blood samples for analysis of anti-influenza antibodies.

“Seasonal influenza is a perpetual public health challenge, and we continually face the possibility of an influenza pandemic resulting from the emergence and spread of novel influenza viruses. This phase 1 clinical trial is a step forward in our efforts to develop a durable and broadly protective universal influenza vaccine,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the NIH website.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, is launching the first in-human trial of a universal influenza vaccine candidate.

The experimental vaccine, H1ssF_3928, is derived from the stem of an H1N1 virus and has a surface made from hemagglutinin and ferritin. By including only the stem of the virus, which changes less than the head, the vaccine should require fewer updates. A similar vaccine made from the same materials was shown to be safe and well tolerated in humans.

The clinical trial (NCT03814720) will be conducted at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., and will gradually enroll at least 53 healthy adults aged 18-70 years. The first 5 participants will receive one 20-mcg intramuscular injection of the vaccine; the other 48 participants will receive two 60-mcg vaccinations 16 weeks apart. Patients will return for 9-11 follow-ups over a 12- to 15-month period, and will provide blood samples for analysis of anti-influenza antibodies.

“Seasonal influenza is a perpetual public health challenge, and we continually face the possibility of an influenza pandemic resulting from the emergence and spread of novel influenza viruses. This phase 1 clinical trial is a step forward in our efforts to develop a durable and broadly protective universal influenza vaccine,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the NIH website.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, is launching the first in-human trial of a universal influenza vaccine candidate.

The experimental vaccine, H1ssF_3928, is derived from the stem of an H1N1 virus and has a surface made from hemagglutinin and ferritin. By including only the stem of the virus, which changes less than the head, the vaccine should require fewer updates. A similar vaccine made from the same materials was shown to be safe and well tolerated in humans.

The clinical trial (NCT03814720) will be conducted at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Md., and will gradually enroll at least 53 healthy adults aged 18-70 years. The first 5 participants will receive one 20-mcg intramuscular injection of the vaccine; the other 48 participants will receive two 60-mcg vaccinations 16 weeks apart. Patients will return for 9-11 follow-ups over a 12- to 15-month period, and will provide blood samples for analysis of anti-influenza antibodies.

“Seasonal influenza is a perpetual public health challenge, and we continually face the possibility of an influenza pandemic resulting from the emergence and spread of novel influenza viruses. This phase 1 clinical trial is a step forward in our efforts to develop a durable and broadly protective universal influenza vaccine,” Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the NIH website.

Measles: Latest weekly count is the highest of the year

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

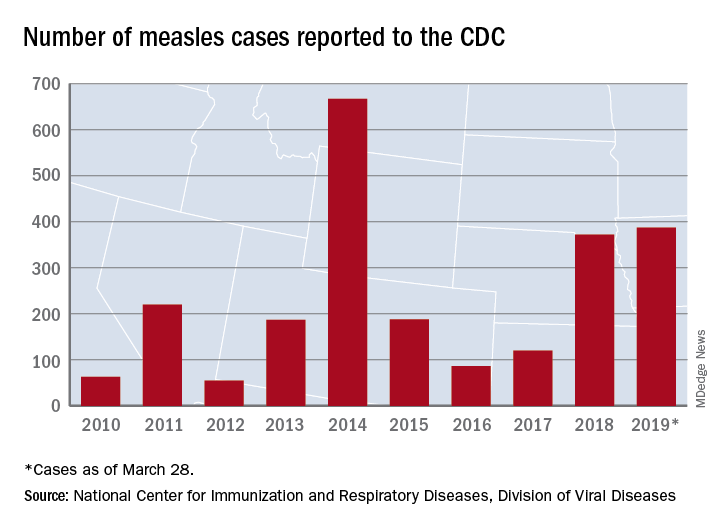

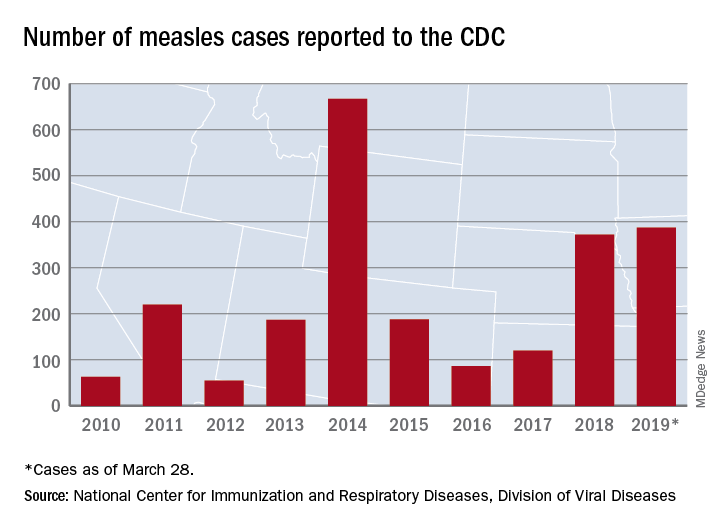

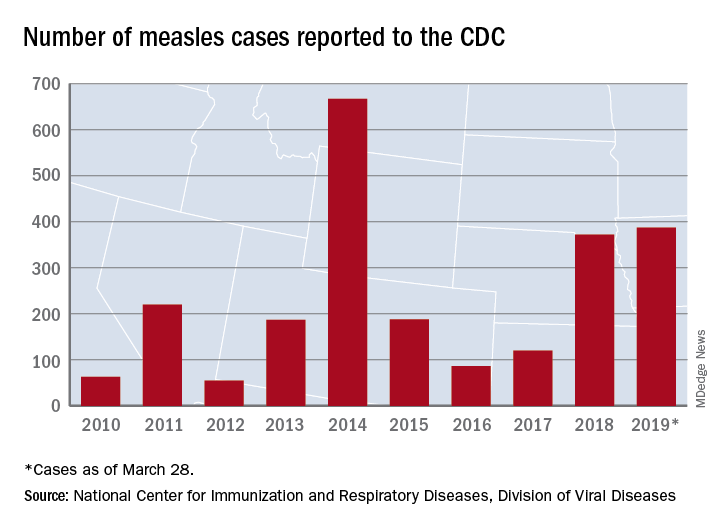

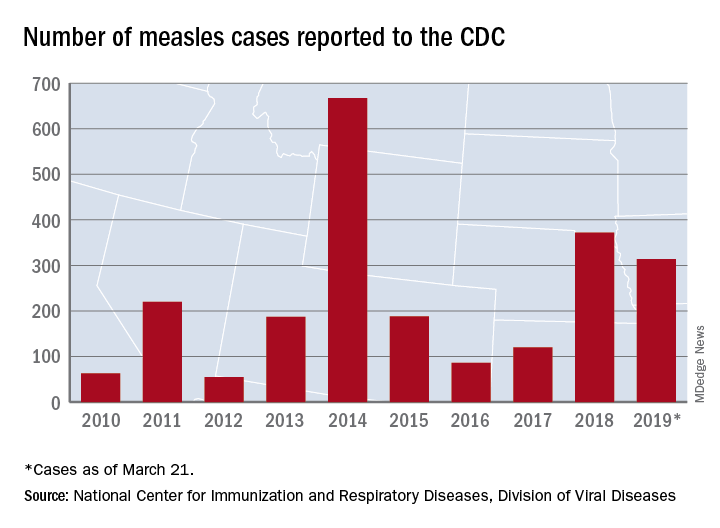

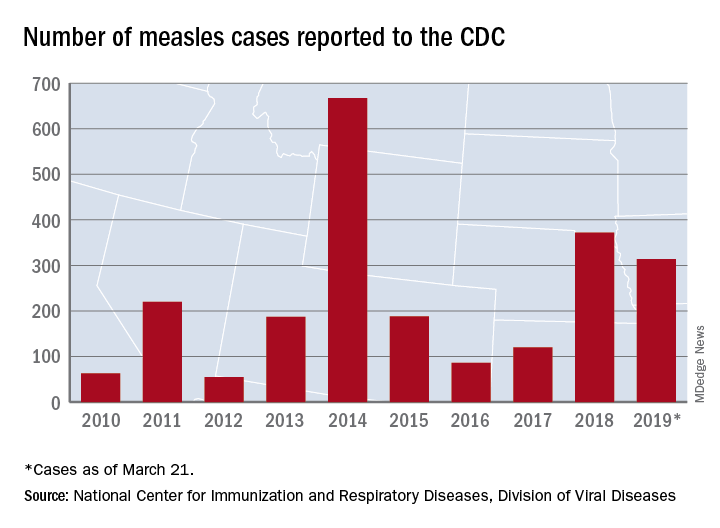

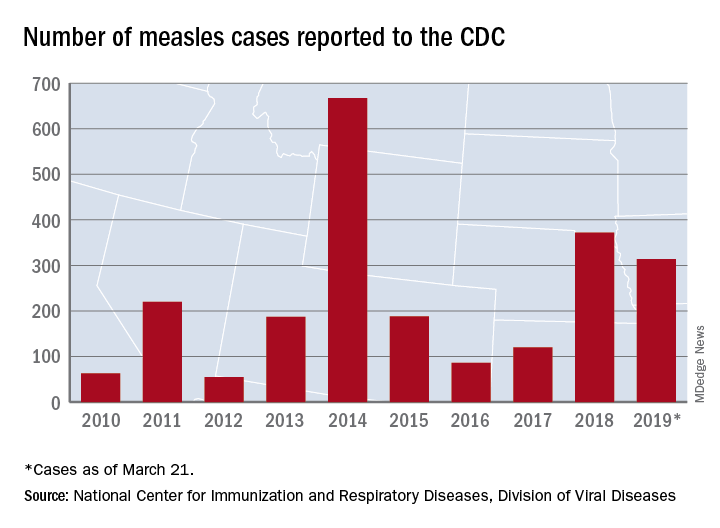

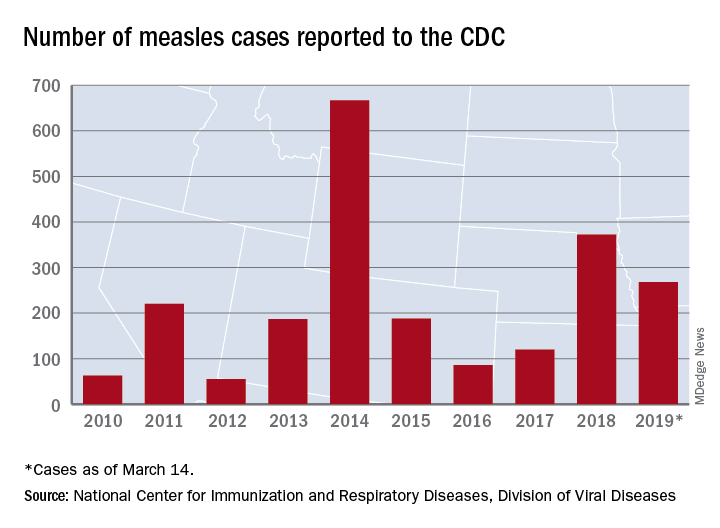

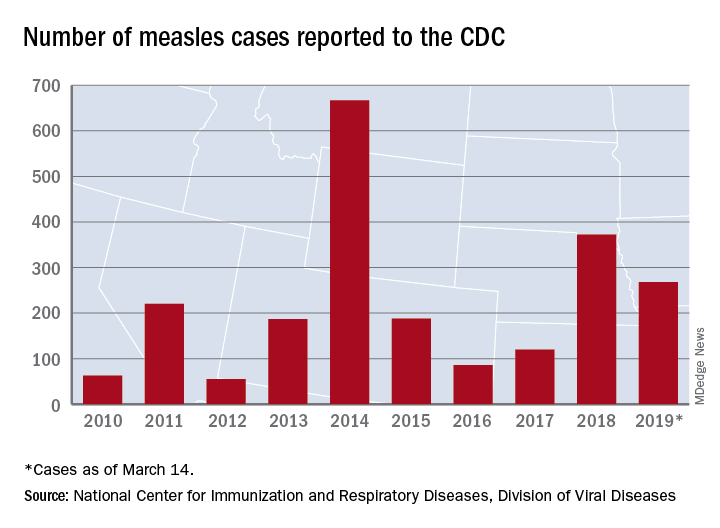

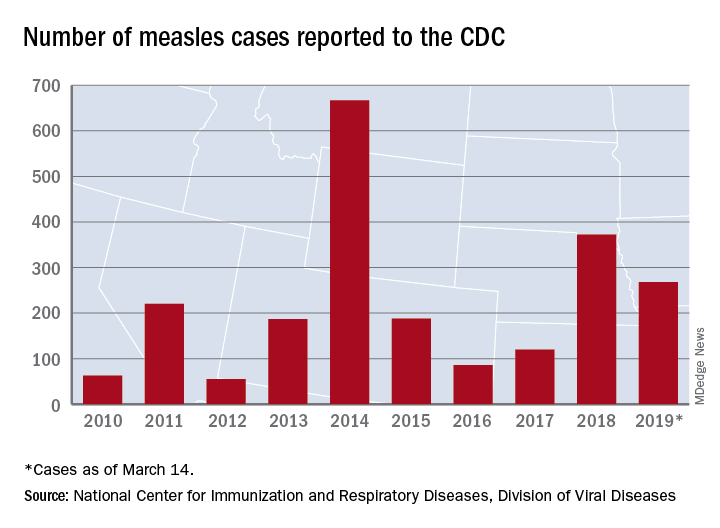

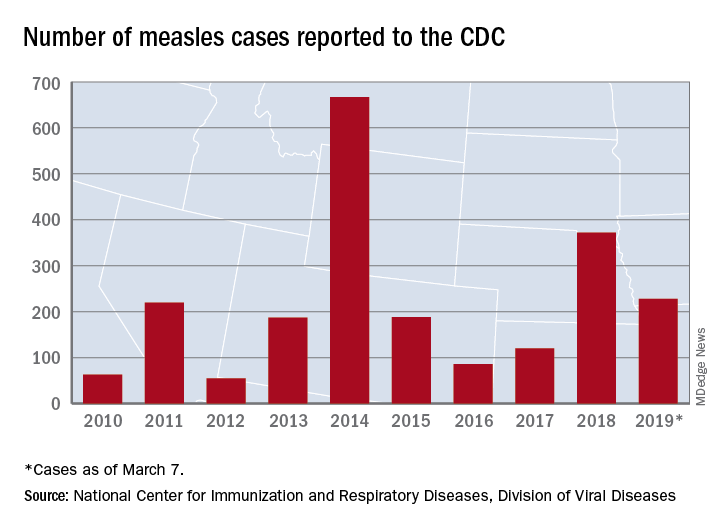

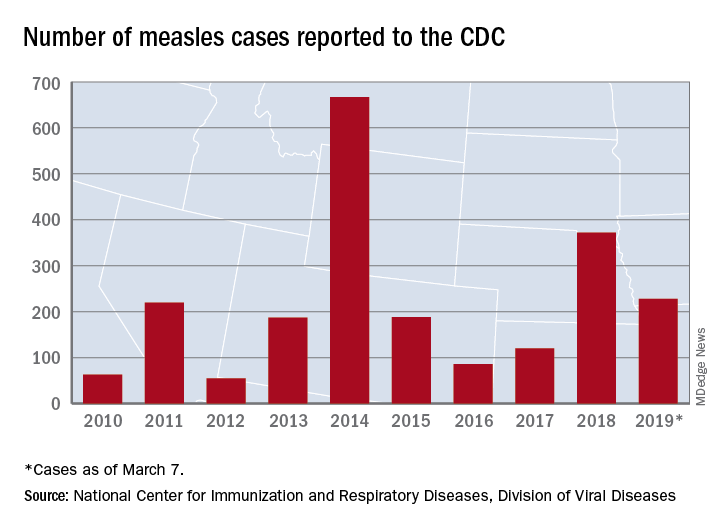

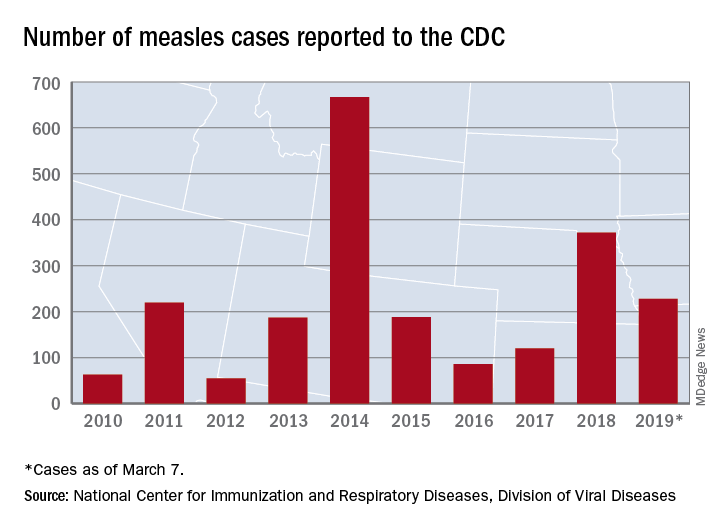

The 73 new cases of measles reported to the CDC during the week ending March 28 – more than any other single week so far in 2019 – brings the total number of cases for the year to 387, the CDC reported April 1. That surpasses the 372 reported in 2018 and is now the highest annual count since 667 cases were reported in 2014.

The ongoing outbreak in Rockland County, N.Y., which resulted in 6 new cases there last week and 52 for the year, prompted County Executive Ed Day to declare a state of emergency effective March 27 that bars unvaccinated individuals under age 18 years from public places for the next 30 days unless they receive an MMR vaccination.

“As this outbreak has continued our inspectors have begun to meet resistance from those they are trying to protect. They have been hung up on or told not to call again. They’ve been told ‘we’re not discussing this, do not come back,’ when visiting the homes of infected individuals as part of their investigations. This type of response is unacceptable and irresponsible. It endangers the health and well-being of others and displays a shocking lack of responsibility and concern for others in our community,” Mr. Day said in a written statement.

In addition to Rockland County, the CDC is currently tracking five other outbreaks: New York City, mainly Brooklyn (33 new cases last week); Washington state (74 cases for the year, but no new cases in the last week); New Jersey (10 total cases, with 8 related to an outbreak in Ocean and Monmouth Counties); and two in California (16 total cases, with 11 related to the outbreaks). One of the California outbreaks and the New Jersey outbreak are new, but the CDC is no longer reporting outbreaks in Texas and Illinois, so the total stays at six nationwide.

In related news from California, state Sen. Richard Pan (D), a pediatrician, and Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D) introduced a bill to monitor vaccine exemptions “by requiring the state health department to vet each medical exemption form written by physicians [and to] maintain a database of exemptions that would allow officials to monitor which doctors are granting the exemptions,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 73 new cases of measles reported to the CDC during the week ending March 28 – more than any other single week so far in 2019 – brings the total number of cases for the year to 387, the CDC reported April 1. That surpasses the 372 reported in 2018 and is now the highest annual count since 667 cases were reported in 2014.

The ongoing outbreak in Rockland County, N.Y., which resulted in 6 new cases there last week and 52 for the year, prompted County Executive Ed Day to declare a state of emergency effective March 27 that bars unvaccinated individuals under age 18 years from public places for the next 30 days unless they receive an MMR vaccination.

“As this outbreak has continued our inspectors have begun to meet resistance from those they are trying to protect. They have been hung up on or told not to call again. They’ve been told ‘we’re not discussing this, do not come back,’ when visiting the homes of infected individuals as part of their investigations. This type of response is unacceptable and irresponsible. It endangers the health and well-being of others and displays a shocking lack of responsibility and concern for others in our community,” Mr. Day said in a written statement.

In addition to Rockland County, the CDC is currently tracking five other outbreaks: New York City, mainly Brooklyn (33 new cases last week); Washington state (74 cases for the year, but no new cases in the last week); New Jersey (10 total cases, with 8 related to an outbreak in Ocean and Monmouth Counties); and two in California (16 total cases, with 11 related to the outbreaks). One of the California outbreaks and the New Jersey outbreak are new, but the CDC is no longer reporting outbreaks in Texas and Illinois, so the total stays at six nationwide.

In related news from California, state Sen. Richard Pan (D), a pediatrician, and Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D) introduced a bill to monitor vaccine exemptions “by requiring the state health department to vet each medical exemption form written by physicians [and to] maintain a database of exemptions that would allow officials to monitor which doctors are granting the exemptions,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 73 new cases of measles reported to the CDC during the week ending March 28 – more than any other single week so far in 2019 – brings the total number of cases for the year to 387, the CDC reported April 1. That surpasses the 372 reported in 2018 and is now the highest annual count since 667 cases were reported in 2014.

The ongoing outbreak in Rockland County, N.Y., which resulted in 6 new cases there last week and 52 for the year, prompted County Executive Ed Day to declare a state of emergency effective March 27 that bars unvaccinated individuals under age 18 years from public places for the next 30 days unless they receive an MMR vaccination.

“As this outbreak has continued our inspectors have begun to meet resistance from those they are trying to protect. They have been hung up on or told not to call again. They’ve been told ‘we’re not discussing this, do not come back,’ when visiting the homes of infected individuals as part of their investigations. This type of response is unacceptable and irresponsible. It endangers the health and well-being of others and displays a shocking lack of responsibility and concern for others in our community,” Mr. Day said in a written statement.

In addition to Rockland County, the CDC is currently tracking five other outbreaks: New York City, mainly Brooklyn (33 new cases last week); Washington state (74 cases for the year, but no new cases in the last week); New Jersey (10 total cases, with 8 related to an outbreak in Ocean and Monmouth Counties); and two in California (16 total cases, with 11 related to the outbreaks). One of the California outbreaks and the New Jersey outbreak are new, but the CDC is no longer reporting outbreaks in Texas and Illinois, so the total stays at six nationwide.

In related news from California, state Sen. Richard Pan (D), a pediatrician, and Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D) introduced a bill to monitor vaccine exemptions “by requiring the state health department to vet each medical exemption form written by physicians [and to] maintain a database of exemptions that would allow officials to monitor which doctors are granting the exemptions,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

Flu shot can be given irrespective of the time of last methotrexate dose

Immune response to influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate appears to depend most on stopping the next two weekly doses of the drug rather than any effect from the timing of the last dose, new research concludes.

The new finding, reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, stems from a post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that Jin Kyun Park, MD, of Seoul (Korea) National University, and his colleagues had conducted earlier on immune response when patients stopped methotrexate for either 2 or 4 weeks after vaccination. While the main endpoint of that study showed no difference in the improvement in vaccine response with either stopping methotrexate for 2 or 4 weeks and no increase in disease activity with stopping for 2 weeks, it was unclear whether the timing of the last dose mattered when stopping for 2 weeks.

In a bid to identify the optimal time between the last dose of methotrexate and administration of a flu vaccine, Dr. Park and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of the trial, which involved 316 patients with RA receiving methotrexate for 6 weeks or longer to continue (n = 156) or to hold methotrexate (n = 160) for 2 weeks after receiving a quadrivalent influenza vaccine containing H1N1, H3N2, B-Yamagata, and B-Victoria.

The study authors defined a positive vaccine response as a fourfold or greater increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer. A satisfactory vaccine response was a positive response to two or more of four vaccine antigens.

Patients who stopped taking methotrexate were divided into eight subgroups according to the number of days between their last dose and their vaccination.

The research team reported that response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

However, they conceded that “the absence of impact of the number of days between the last methotrexate dose and vaccination could be due to the small patient numbers in eight subgroups.”

Vaccine response also did not differ between patients who received the influenza vaccination within 3 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 65) and those who received it between 4-7 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 95).

Furthermore, RA disease activity, seropositivity, or use of conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs did not have an impact on methotrexate discontinuation.

The authors concluded that vaccinations could be given irrespective of the time of the last methotrexate dose, and patients should be advised to skip two weekly doses following vaccination.

“This supports the notion that the effects of methotrexate on humeral immunity occur rapidly, despite the delayed effects on arthritis; therefore, the absence of methotrexate during the first 2 weeks postvaccination is critical for humoral immunity,” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

SOURCE: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187.

Immune response to influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate appears to depend most on stopping the next two weekly doses of the drug rather than any effect from the timing of the last dose, new research concludes.

The new finding, reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, stems from a post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that Jin Kyun Park, MD, of Seoul (Korea) National University, and his colleagues had conducted earlier on immune response when patients stopped methotrexate for either 2 or 4 weeks after vaccination. While the main endpoint of that study showed no difference in the improvement in vaccine response with either stopping methotrexate for 2 or 4 weeks and no increase in disease activity with stopping for 2 weeks, it was unclear whether the timing of the last dose mattered when stopping for 2 weeks.

In a bid to identify the optimal time between the last dose of methotrexate and administration of a flu vaccine, Dr. Park and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of the trial, which involved 316 patients with RA receiving methotrexate for 6 weeks or longer to continue (n = 156) or to hold methotrexate (n = 160) for 2 weeks after receiving a quadrivalent influenza vaccine containing H1N1, H3N2, B-Yamagata, and B-Victoria.

The study authors defined a positive vaccine response as a fourfold or greater increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer. A satisfactory vaccine response was a positive response to two or more of four vaccine antigens.

Patients who stopped taking methotrexate were divided into eight subgroups according to the number of days between their last dose and their vaccination.

The research team reported that response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

However, they conceded that “the absence of impact of the number of days between the last methotrexate dose and vaccination could be due to the small patient numbers in eight subgroups.”

Vaccine response also did not differ between patients who received the influenza vaccination within 3 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 65) and those who received it between 4-7 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 95).

Furthermore, RA disease activity, seropositivity, or use of conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs did not have an impact on methotrexate discontinuation.

The authors concluded that vaccinations could be given irrespective of the time of the last methotrexate dose, and patients should be advised to skip two weekly doses following vaccination.

“This supports the notion that the effects of methotrexate on humeral immunity occur rapidly, despite the delayed effects on arthritis; therefore, the absence of methotrexate during the first 2 weeks postvaccination is critical for humoral immunity,” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

SOURCE: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187.

Immune response to influenza vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking methotrexate appears to depend most on stopping the next two weekly doses of the drug rather than any effect from the timing of the last dose, new research concludes.

The new finding, reported in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, stems from a post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that Jin Kyun Park, MD, of Seoul (Korea) National University, and his colleagues had conducted earlier on immune response when patients stopped methotrexate for either 2 or 4 weeks after vaccination. While the main endpoint of that study showed no difference in the improvement in vaccine response with either stopping methotrexate for 2 or 4 weeks and no increase in disease activity with stopping for 2 weeks, it was unclear whether the timing of the last dose mattered when stopping for 2 weeks.

In a bid to identify the optimal time between the last dose of methotrexate and administration of a flu vaccine, Dr. Park and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis of the trial, which involved 316 patients with RA receiving methotrexate for 6 weeks or longer to continue (n = 156) or to hold methotrexate (n = 160) for 2 weeks after receiving a quadrivalent influenza vaccine containing H1N1, H3N2, B-Yamagata, and B-Victoria.

The study authors defined a positive vaccine response as a fourfold or greater increase in hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer. A satisfactory vaccine response was a positive response to two or more of four vaccine antigens.

Patients who stopped taking methotrexate were divided into eight subgroups according to the number of days between their last dose and their vaccination.

The research team reported that response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

However, they conceded that “the absence of impact of the number of days between the last methotrexate dose and vaccination could be due to the small patient numbers in eight subgroups.”

Vaccine response also did not differ between patients who received the influenza vaccination within 3 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 65) and those who received it between 4-7 days of the last methotrexate dose (n = 95).

Furthermore, RA disease activity, seropositivity, or use of conventional or biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs did not have an impact on methotrexate discontinuation.

The authors concluded that vaccinations could be given irrespective of the time of the last methotrexate dose, and patients should be advised to skip two weekly doses following vaccination.

“This supports the notion that the effects of methotrexate on humeral immunity occur rapidly, despite the delayed effects on arthritis; therefore, the absence of methotrexate during the first 2 weeks postvaccination is critical for humoral immunity,” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

SOURCE: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Response to vaccine, fold increase in HI antibody titers, and postvaccination seroprotection rates were not associated with the time between the last methotrexate dose and the time of vaccination.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of a randomized, controlled trial involving 316 patients with rheumatoid arthritis who continued or stopped methotrexate for 2 weeks following influenza vaccination.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by GC Pharma. One author disclosed serving as a consultant to Pfizer and receiving research grants from GC Pharma and Hanmi Pharma.

Source: Park JK et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Mar 23. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215187

Achieving Excellence in Hepatitis B Virus Care for Veterans in the VHA (FULL)

Hepatitis B is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is transmitted through percutaneous (ie, puncture through the skin) or mucosal (ie, direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Hepatitis B virus can cause chronic infection, resulting in cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Persons with chronic infection also serve as the main reservoir for continued HBV transmission.1

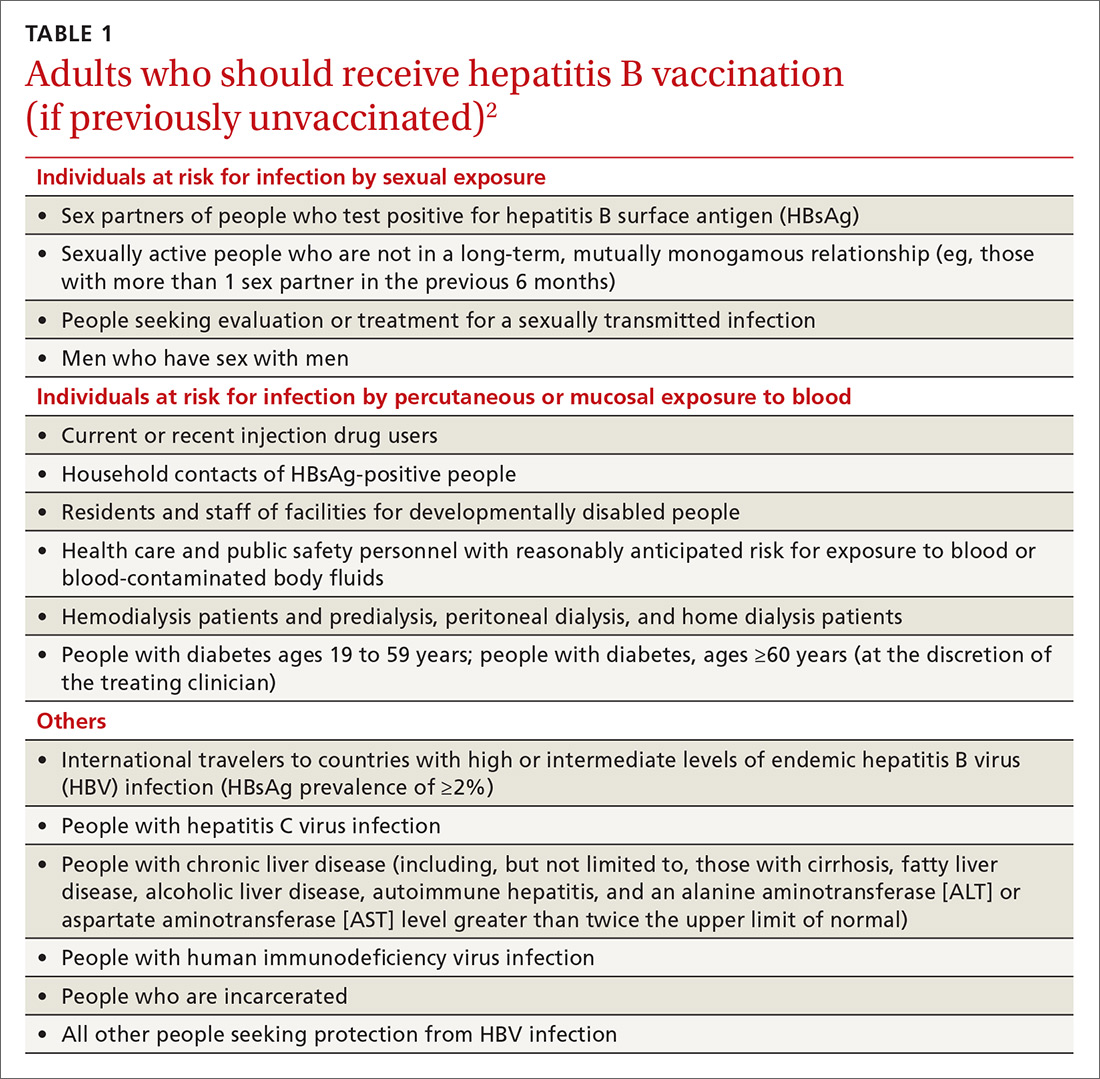

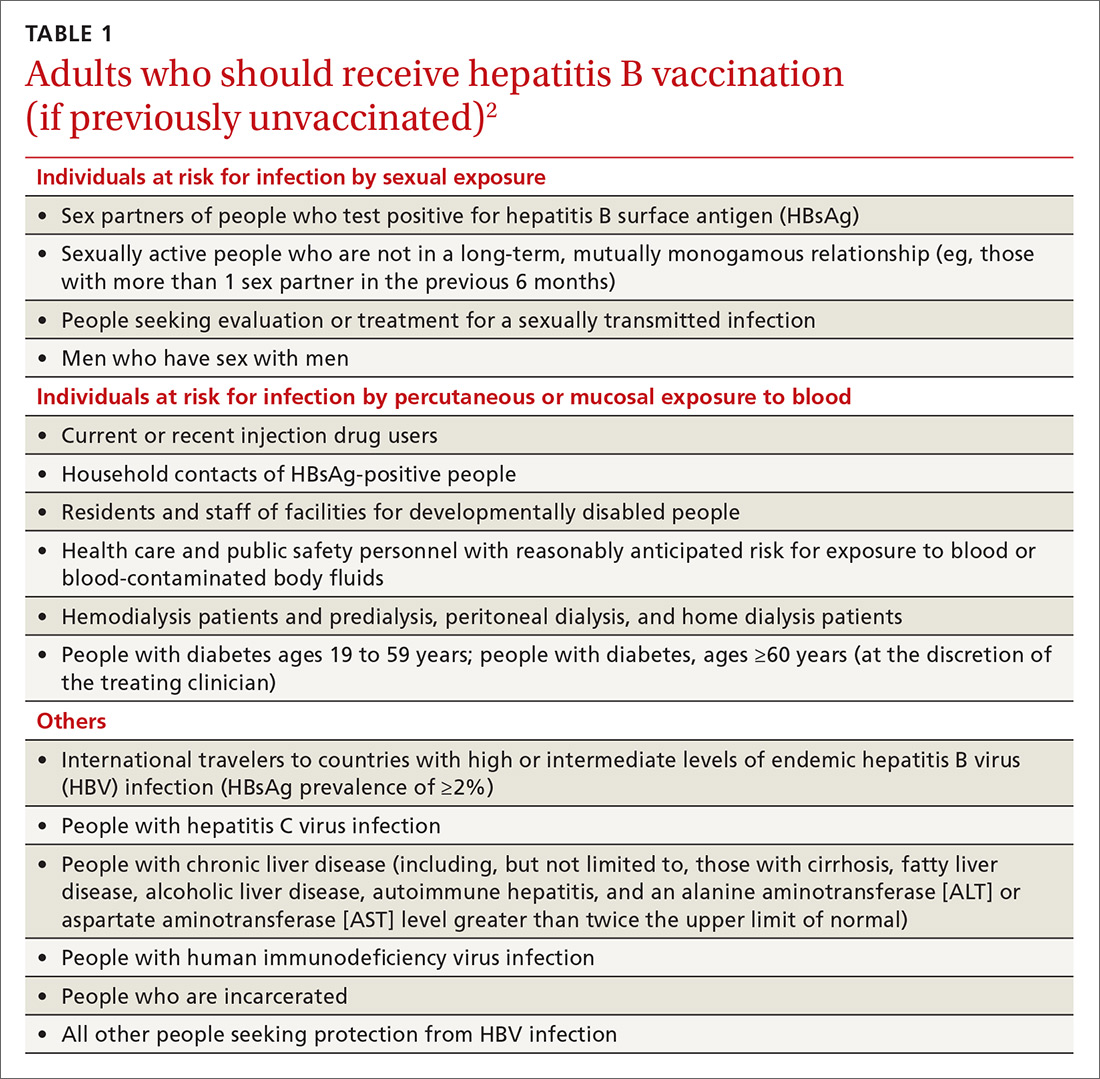

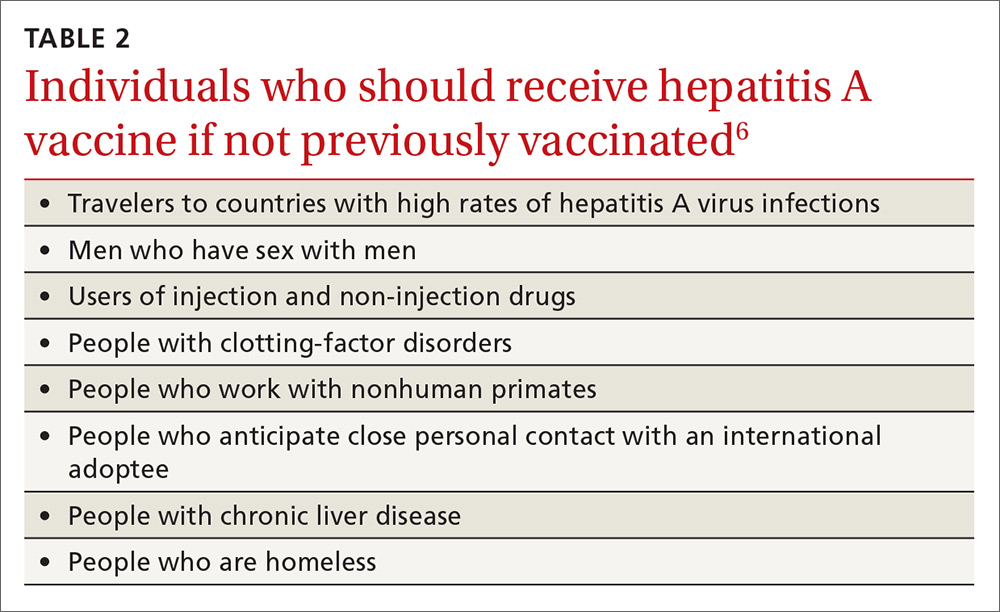

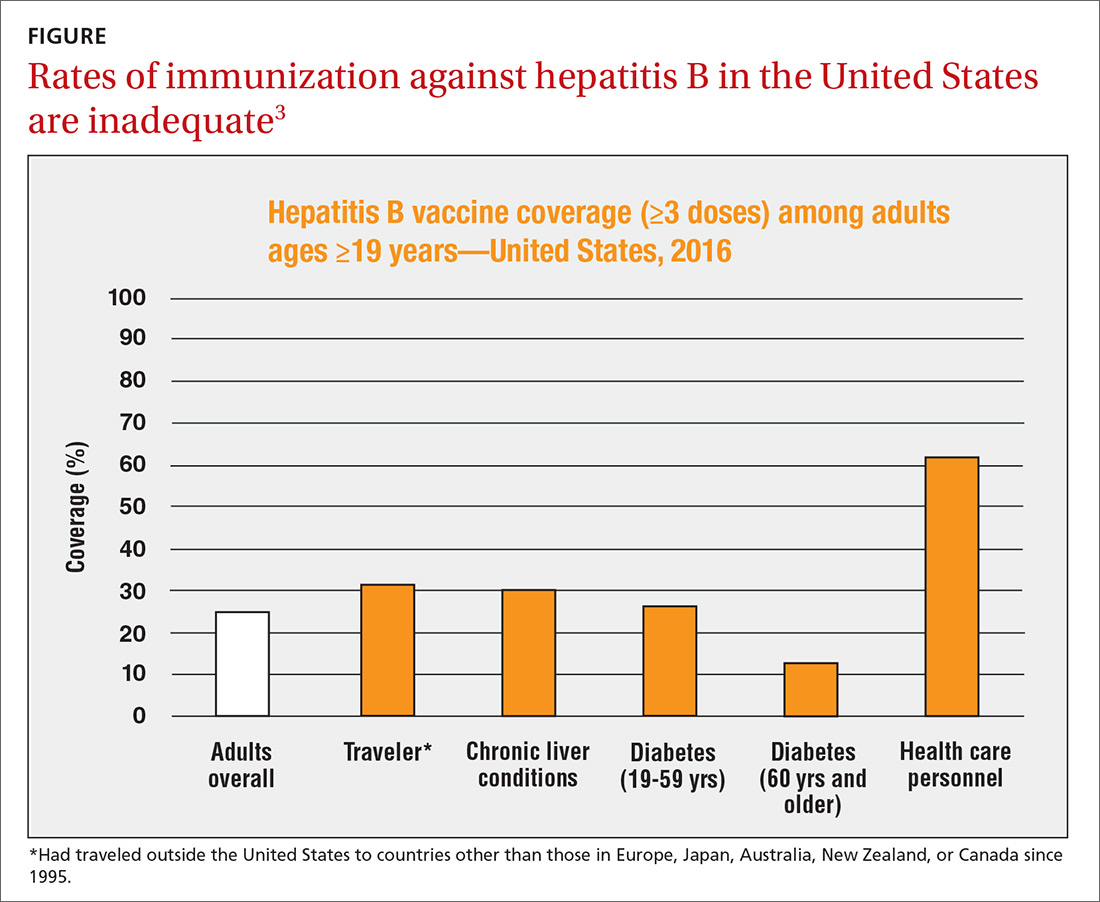

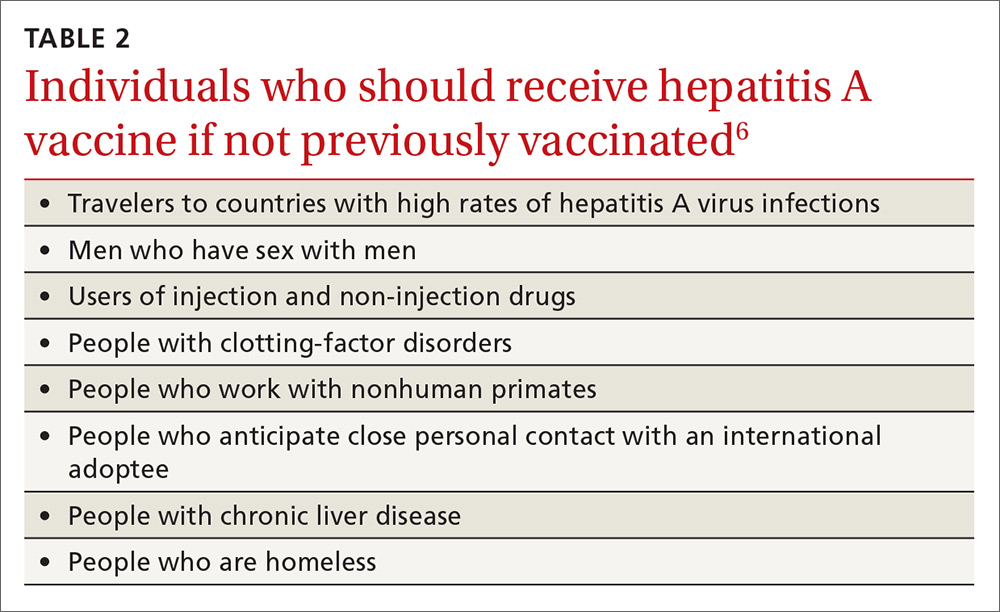

Individuals at highest risk for infection include those born in geographic regions with a high prevalence of HBV, those with sexual partners or household contacts with chronic HBV infection, men who have sex with men (MSM), those with HIV, and individuals who inject drugs. Pregnant women also are a population of concern given the potential for perinatal transmission.2

About 850,000 to 2.2 million people in the US (about 0.3% of the civilian US population) are chronically infected with HBV.3 The prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher (10%-19%) among Asian Americans, those of Pacific Island descent, and other immigrant populations from highly endemic countries.4 In the US, HBV is responsible for 2,000 to 4,000 preventable deaths annually, primarily from cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatic failure.4 In the civilian US population, reported cases of acute HBV decreased 0.3% from 2011 to 2012, increased 5.4% in 2013 with an 8.5% decrease in 2014, and a 20.7% increase in 2015.4 Injection drug use is likely driving the most recent increase.5

Not all individuals exposed to HBV will develop chronic infection, and the risk of chronic HBV infection depends on an individual’s age at the time of exposure. For example, about 95% of infants exposed to HBV perinatally will develop a chronic infection compared with 5% of exposed adults.6 Of those with chronic HBV, a small proportion will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with increasing risk as viral DNA concentrations increase. Additional risk factors for cirrhosis include being older, male, having a persistently elevated alanine transaminase, viral superinfections, HBV reversion/reactivation, genotype, and various markers of disease severity (HCC).6 Of note, chronic HBV infection may cause HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.7 In addition, immunosuppression (eg, from cancer chemotherapy) may allow HBV reactivation, which may result in fulminant hepatic failure. In the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) health care system, about 17% of those with known chronic HBV also carry a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Vaccination is the mainstay of efforts to prevent HBV infection. The first commercially available HBV vaccine was approved by the FDA in 1981, with subsequent FDA approval in 1986 of a vaccine manufactured using recombinant DNA technology.8 In 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal childhood vaccination for HBV, with subsequent recommendations for vaccination of adolescents and adults in high-risk groups in 1995, and in 1999 all remaining unvaccinated children aged ≤ 19 years.9 Military policy has been to provide hepatitis B immunization to personnel assigned to the Korean peninsula since 1986 and to all recruits since 2001.10

Following publication of an Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, in 2011 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.11 The current HHS Action Plan, along with the NASEM National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report, commissioned by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), outlines a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.12 The VA is a critical partner in this federal collaborative effort to achieve excellence in viral hepatitis care.

In August 2016, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs in the VA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a National Hepatitis B Working Group consisting of VA subject matter experts (SMEs) and representatives from the VA Central Office stakeholder program offices, with a charge of developing a strategic plan to ensure excellence in HBV prevention, care, and management across the VHA. The task included addressing supportive processes and barriers at each level of the organization through a public health framework and using a population health management approach.

The VA National Strategic Plan for Excellence in HBV Care was focused on the following overarching aims:

- Characterizing the current state of care for veterans with HBV in VA care;

- Developing and disseminating clinical guidance on high-quality care for patients with HBV;

- Developing population data and informatics tools to streamline the identification and monitoring of patients with chronic HBV; and

- Evaluating VHA care for patients with HBV over time.

Care for Veterans With HBV at the VA

The VA health care system is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at 1,243 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1,063 outpatient sites of care serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.13 As of January 2018, there were 10,743 individuals with serologic evidence for chronic HBV infection in VA care, based on a definition of 2 or more detectable surface antigen (sAg) or hepatitis B DNA tests recorded at least 6 months apart.1 About 2,000 additional VA patients have a history of a single positive sAg test. These patients have unclear HBV status and require a second sAg test to determine whether they have a chronic infection.

The prevalence of HBV infection among veterans in VA care is slightly higher than that in the US civilian population at 0.4%.14 Studies of selected subpopulations of veterans have found high seropositivity of prior or chronic HBV infection among homeless veterans and veterans admitted to a psychiatric hospital.15,16 The data from 2015 suggest that homeless veterans have a chronic HBV infection rate of 1.0%.14 Of those with known chronic HBV infection, the plurality are white (40.4%) or African American (40.2%), male (92.4%), with a mean age of 59.9 (SD 12.0) years. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, the geographic territories with the largest chronic HBV caseload include the Southeast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast. As of January 2018, 1,210 veterans in care have HBV-related cirrhosis.

HBV Screening in VA

The current VA HBV screening guidelines follow those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17 HBV screening is recommended for unvaccinated individuals in high-risk groups, such as patients with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), those on hemodialysis, those with elevated alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase of unknown etiology, those on immunosuppressive therapy, injection drug users, the MSM population, people with household contact with an HBV-infected person, people born to an HBV-infected mother, those with risk factors for HBV exposure prior to vaccination, pregnant women, and people born in highly endemic areas regardless of vaccination status.2 The VHA recommends against standardized risk assessment and laboratory screening for HBV infection in the asymptomatic general patient population. However, if risk factors become known during the course of providing usual clinical care, then laboratory screening should be considered.2

Of the 6.1 million VHA users

HBV Care and VA Antiviral Treatment

In a study of an HBV care cascade, Serper and colleagues reviewed a cohort of veterans in the VA with HBV. About 50% of the patients with known chronic HBV in the VA system from 1999 to 2013 had received infectious diseases or gastroenterology/hepatology specialty care in the previous 2 years.19 Follow-up data from the National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group indicated that this remains the case: 52.3% of patients with documented chronic HBV had received specialty care from VA sources in the prior 2 years. Serper and colleagues also reported that among veterans in VHA care with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis from 1999 to 2013, annual imaging was < 50%, and initiation of antiviral treatment was only 39%. Antiviral therapy and liver imaging were both independently associated with lower mortality for patients with HBV and cirrhosis.19

A review of studies that evaluated the delivery of care for patients with HBV in U.S. civilian populations, including retrospective reviews of private payer claims databases and chart reviews, the Kaiser Permanente claims database, and community gastrointestinal (GI) practice chart reviews, revealed similar practice patterns with those in the VA.20 Across the US, rates of antiviral therapy and HCC surveillance for those with HBV cirrhosis were low, ranging from 14% to 50% and 19% to 60%, respectively. Several of these studies also found that being seen by an HBV specialist was associated with improved care.20

Antiviral treatment of individuals with cirrhosis and chronic HBV infection can reduce the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and liver cancer. Among current VA patients with HBV cirrhosis, 62.4% received at least 1 month of HBV antiviral medication in the prior year. Additionally, biannual liver imaging is recommended in this population to screen for the development of HCC. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, nationally, 51.2% of individuals with HBV cirrhosis had received at least one instance of liver imaging within the past 6 months, and 71.2% received imaging within the past 12 months.

Prevention of HBV Infection and Sequelae

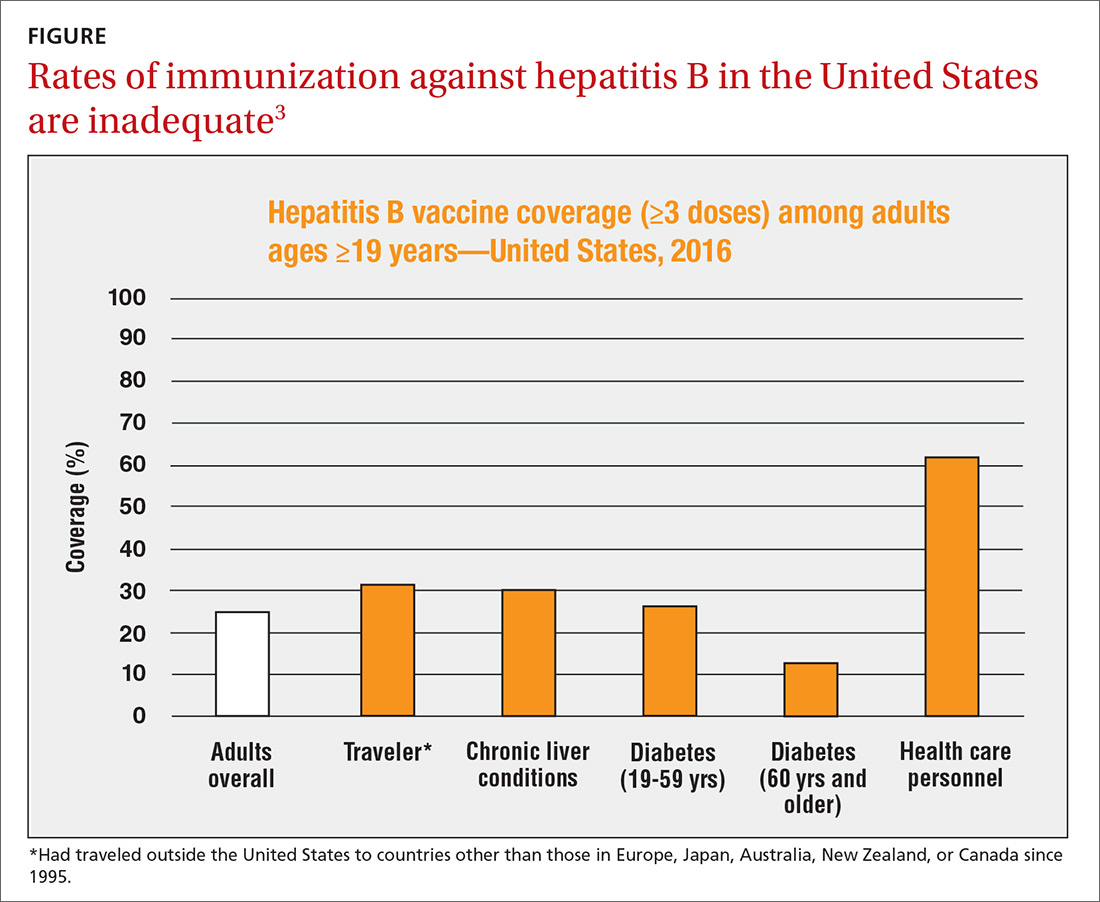

Vaccination rates in the US vary by age group, with higher immunization rates among those born after 1991 than the rates of those born earlier. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1988 to 2012 reported 33% immunity among veterans aged < 50 years and 6% among those aged ≥ 50 years.21 In addition to individuals who received childhood vaccination in the 1990s, all new military recruits assigned to the Korean Peninsula were vaccinated for HBV as of 1986, and those joining the military after 2002 received mandatory vaccination.

The VA follows the ACIP/CDC hepatitis B immunization guidelines.22-24 The VA currently recommends HBV immunization among previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk of contracting HBV infection and for any other adult who is seeking protection from HBV infection. The VA also offers general recommendations for prevention of transmission between veterans with known chronic HBV to their household, sexual, or drug-using partners. Transmission prevention guidelines also provide recommendations for vaccination of pregnant women with HBV risk factors and women at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy.22

HBV Care Guidance

One of the core tasks of the VA National Hepatitis B Working Group, given its broad, multidisciplinary expertise in HBV, was developing general clinical guidelines for the provision of high-quality care for patients with HBV. The group reviewed current literature and scientific evidence on care for patients with HBV. The working group relied heavily on the VA’s national guidelines for HBV screening and immunization, which are based on recommendations from the USPSTF, ACIP, CDC, and professional societies. The professional society guidelines included the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, the America College of Gastroenterology’s Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute’s Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Reactivation during Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy, and CDC’s Guidelines for Screening Pregnant Women for HBV.19,22-27

The working group identified areas for HBV quality improvement that were consistent with the VA and professional guidelines, specific and measurable using VA data, clinically relevant, feasible, and achievable in a defined time period. Areas for targeted improvement will include testing for HBV among high-risk patients, increasing antiviral treatment and HCC surveillance of veterans with HBV-related cirrhosis, decreasing progression of chronic HBV to cirrhosis, and expanding prevention measures, such as immunization among those at high risk for HBV and prevention of HBV reactivation.

At a national level, development of specific and measurable quality of care indicators for HBV will aid in assessing gaps in care and developing strategies to address these gaps. A broader discussion of care for patients with HBV quality with front-line health care providers (HCPs) will be paired with increased education and providing clinical support tools for those HCPs and facilities without access to specialty GI services.

Clinical pharmacists will be critical targets for the dissemination of guidance for HBV care paired with clinical informatics support tools and clinical educational opportunities. As of 2015, there were about 7,700 clinical pharmacists in the VHA and 3,200 had a scope of practice that included prescribing authority. As a result, 20% of HCV prescriptions in the VA in fiscal year 2015

Identification and Monitoring

The HBV working group and the VA Viral Hepatitis Technical Advisory Group are working with field HCPs to develop several informatics tools to promote HBV case identification and quality monitoring. These groups identified several barriers to HBV case identification and monitoring. The following informatics tools are either available or in development to reduce these barriers:

- A local clinical case registry of patients with HBV infection based on ICD codes, which allows users to create custom reports to identify, monitor, and track care;

- Because of the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with chronic HBV infection who receive anti-CD20 agents, such as rituximab, a medication order check to improve HBV screening among veterans receiving anti-CD20 medication;

- Validated patient reports based on laboratory diagnosis of HBV, drawn from all results across the VHA since 1999, made available to all facilities;

- Interactive reports summarizing quality of care for patients with HBV infection, based on facility-level indicators in development by the national HBV working group, will be distributed and enable geographic comparison;

- An HBV immunization clinical reminder that will prompt frontline HCPs to test and vaccinate; and

- An HBV clinical dashboard that will enable HCPs and facilities to identify all their HBV-positive veterans and track their care and outcomes over time.

Evaluating VA Care for Patients with HBV

As indicators of quality of HBV care are refined for VA patients and the health care delivery system, guidance will be made broadly available to frontline HCPs and administrators. The HBV quality of care recommendations will be paired with a suite of clinical informatics tools and virtual educational trainings to ensure that VA HCPs and facilities can streamline care for patients with HBV infection as much as possible. Quality improvement will be measured nationally each year, and strategies to address persistent variability and gaps in care will be developed in collaboration with the VA SME’s, facilities, and HCPs.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B virus is at least as prevalent among veterans who are cared for at VA facilities as it is in the US civilian population. Although care for patients with HBV infection in the VA is similar to care for patients with HBV infection in the community, the VA recognizes areas for improved HBV prevention, testing, care, and treatment. The VA has begun a continuous quality improvement strategic plan to enhance the level of care for patients with HBV infection in VA care. Centralized coordination and communication of VA data combined with veteran- and field-centered policies and operational planning and execution will allow clinically relevant improvements in HBV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention among veterans served by VA.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals: overview and statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq .htm#overview. Updated January 11, 2018. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

2.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2015surveillance/index.htm. Updated June 19, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2018.

4. Kim WR. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology. 2009;49(suppl 5):S28-S34.

5. Harris AM, Iqbal K, Schillie S, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis B virus infections— Kentucky, Tennessee, and West Virginia, 2006-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(3):47-50.

6. Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373(9663):582-592.

7. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118-1127.

8. Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-8):1-20.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health: hepatitis B vaccination—United States, 1982-2002. MMWR. 2002;51(25):549-552, 563.

10. Grabenstein JD, Pittman PR, Greenwood JT, Engler RJ. Immunization to protect the US Armed Forces: heritage, current practice, and prospects. Epidemiol Rev. 2006;28:3-26.

11. Colvin HM, Mitchell AE, eds; Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Providing health care for veterans. https://www.va.gov/health. Updated February 20, 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

14. Noska AJ, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, O’Toole TP, Backus LI. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus among homeless and nonhomeless United States veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(2):252-258.

15. Gelberg L, Robertson MJ, Leake B, et al. Hepatitis B among homeless and other impoverished US military veterans in residential care in Los Angeles. Public Health. 2001;115(4):286-291.

16. Tabibian JH, Wirshing DA, Pierre JM, et al. Hepatitis B and C among veterans in a psychiatric ward. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(6):1693-1698

17. US Preventive Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement: screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening-2014. Published May 2014. Updated February 2018. Accessed February 22, 2018.

18. Backus LI, Belperio PS, Loomis TP, Han SH, Mole LA. Screening for and prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection among high-risk veterans under the care of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(12):926-928.

19. Serper M, Choi G, Forde KA, Kaplan DE. Care delivery and outcomes among US veterans with hepatitis B: a national cohort study. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1774-1782.

20. Mellinger J, Fontana RJ. Quality of care metrics in chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1755-1758.

21. Roberts H, Kruszon-Moran D, Ly KN, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in U.S. households: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988-2012. Hepatology. 2016;63(2):388-397.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Clinical Preventive Service Guidance Statements: Hepatitis B Immunization. http://vaww.prevention.va.gov/CPS/Hepatitis_B_Immunization.asp. Nonpublic document. Source not verified.

23. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Recommended immunization schedule for adults aged 19 years or older, United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

24. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2018;67(1):1-31.

25. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):261-283.

26. Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):18-35.

27. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT; American Gastroenterological Association Institute. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):215-219, quiz e16-e17.

28. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

Hepatitis B is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is transmitted through percutaneous (ie, puncture through the skin) or mucosal (ie, direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Hepatitis B virus can cause chronic infection, resulting in cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Persons with chronic infection also serve as the main reservoir for continued HBV transmission.1

Individuals at highest risk for infection include those born in geographic regions with a high prevalence of HBV, those with sexual partners or household contacts with chronic HBV infection, men who have sex with men (MSM), those with HIV, and individuals who inject drugs. Pregnant women also are a population of concern given the potential for perinatal transmission.2

About 850,000 to 2.2 million people in the US (about 0.3% of the civilian US population) are chronically infected with HBV.3 The prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher (10%-19%) among Asian Americans, those of Pacific Island descent, and other immigrant populations from highly endemic countries.4 In the US, HBV is responsible for 2,000 to 4,000 preventable deaths annually, primarily from cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatic failure.4 In the civilian US population, reported cases of acute HBV decreased 0.3% from 2011 to 2012, increased 5.4% in 2013 with an 8.5% decrease in 2014, and a 20.7% increase in 2015.4 Injection drug use is likely driving the most recent increase.5

Not all individuals exposed to HBV will develop chronic infection, and the risk of chronic HBV infection depends on an individual’s age at the time of exposure. For example, about 95% of infants exposed to HBV perinatally will develop a chronic infection compared with 5% of exposed adults.6 Of those with chronic HBV, a small proportion will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with increasing risk as viral DNA concentrations increase. Additional risk factors for cirrhosis include being older, male, having a persistently elevated alanine transaminase, viral superinfections, HBV reversion/reactivation, genotype, and various markers of disease severity (HCC).6 Of note, chronic HBV infection may cause HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.7 In addition, immunosuppression (eg, from cancer chemotherapy) may allow HBV reactivation, which may result in fulminant hepatic failure. In the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) health care system, about 17% of those with known chronic HBV also carry a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Vaccination is the mainstay of efforts to prevent HBV infection. The first commercially available HBV vaccine was approved by the FDA in 1981, with subsequent FDA approval in 1986 of a vaccine manufactured using recombinant DNA technology.8 In 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal childhood vaccination for HBV, with subsequent recommendations for vaccination of adolescents and adults in high-risk groups in 1995, and in 1999 all remaining unvaccinated children aged ≤ 19 years.9 Military policy has been to provide hepatitis B immunization to personnel assigned to the Korean peninsula since 1986 and to all recruits since 2001.10

Following publication of an Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, in 2011 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.11 The current HHS Action Plan, along with the NASEM National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report, commissioned by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), outlines a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.12 The VA is a critical partner in this federal collaborative effort to achieve excellence in viral hepatitis care.

In August 2016, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs in the VA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a National Hepatitis B Working Group consisting of VA subject matter experts (SMEs) and representatives from the VA Central Office stakeholder program offices, with a charge of developing a strategic plan to ensure excellence in HBV prevention, care, and management across the VHA. The task included addressing supportive processes and barriers at each level of the organization through a public health framework and using a population health management approach.

The VA National Strategic Plan for Excellence in HBV Care was focused on the following overarching aims:

- Characterizing the current state of care for veterans with HBV in VA care;

- Developing and disseminating clinical guidance on high-quality care for patients with HBV;

- Developing population data and informatics tools to streamline the identification and monitoring of patients with chronic HBV; and

- Evaluating VHA care for patients with HBV over time.

Care for Veterans With HBV at the VA

The VA health care system is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at 1,243 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1,063 outpatient sites of care serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.13 As of January 2018, there were 10,743 individuals with serologic evidence for chronic HBV infection in VA care, based on a definition of 2 or more detectable surface antigen (sAg) or hepatitis B DNA tests recorded at least 6 months apart.1 About 2,000 additional VA patients have a history of a single positive sAg test. These patients have unclear HBV status and require a second sAg test to determine whether they have a chronic infection.

The prevalence of HBV infection among veterans in VA care is slightly higher than that in the US civilian population at 0.4%.14 Studies of selected subpopulations of veterans have found high seropositivity of prior or chronic HBV infection among homeless veterans and veterans admitted to a psychiatric hospital.15,16 The data from 2015 suggest that homeless veterans have a chronic HBV infection rate of 1.0%.14 Of those with known chronic HBV infection, the plurality are white (40.4%) or African American (40.2%), male (92.4%), with a mean age of 59.9 (SD 12.0) years. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, the geographic territories with the largest chronic HBV caseload include the Southeast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast. As of January 2018, 1,210 veterans in care have HBV-related cirrhosis.

HBV Screening in VA

The current VA HBV screening guidelines follow those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17 HBV screening is recommended for unvaccinated individuals in high-risk groups, such as patients with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), those on hemodialysis, those with elevated alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase of unknown etiology, those on immunosuppressive therapy, injection drug users, the MSM population, people with household contact with an HBV-infected person, people born to an HBV-infected mother, those with risk factors for HBV exposure prior to vaccination, pregnant women, and people born in highly endemic areas regardless of vaccination status.2 The VHA recommends against standardized risk assessment and laboratory screening for HBV infection in the asymptomatic general patient population. However, if risk factors become known during the course of providing usual clinical care, then laboratory screening should be considered.2

Of the 6.1 million VHA users

HBV Care and VA Antiviral Treatment

In a study of an HBV care cascade, Serper and colleagues reviewed a cohort of veterans in the VA with HBV. About 50% of the patients with known chronic HBV in the VA system from 1999 to 2013 had received infectious diseases or gastroenterology/hepatology specialty care in the previous 2 years.19 Follow-up data from the National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group indicated that this remains the case: 52.3% of patients with documented chronic HBV had received specialty care from VA sources in the prior 2 years. Serper and colleagues also reported that among veterans in VHA care with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis from 1999 to 2013, annual imaging was < 50%, and initiation of antiviral treatment was only 39%. Antiviral therapy and liver imaging were both independently associated with lower mortality for patients with HBV and cirrhosis.19

A review of studies that evaluated the delivery of care for patients with HBV in U.S. civilian populations, including retrospective reviews of private payer claims databases and chart reviews, the Kaiser Permanente claims database, and community gastrointestinal (GI) practice chart reviews, revealed similar practice patterns with those in the VA.20 Across the US, rates of antiviral therapy and HCC surveillance for those with HBV cirrhosis were low, ranging from 14% to 50% and 19% to 60%, respectively. Several of these studies also found that being seen by an HBV specialist was associated with improved care.20

Antiviral treatment of individuals with cirrhosis and chronic HBV infection can reduce the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and liver cancer. Among current VA patients with HBV cirrhosis, 62.4% received at least 1 month of HBV antiviral medication in the prior year. Additionally, biannual liver imaging is recommended in this population to screen for the development of HCC. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, nationally, 51.2% of individuals with HBV cirrhosis had received at least one instance of liver imaging within the past 6 months, and 71.2% received imaging within the past 12 months.

Prevention of HBV Infection and Sequelae

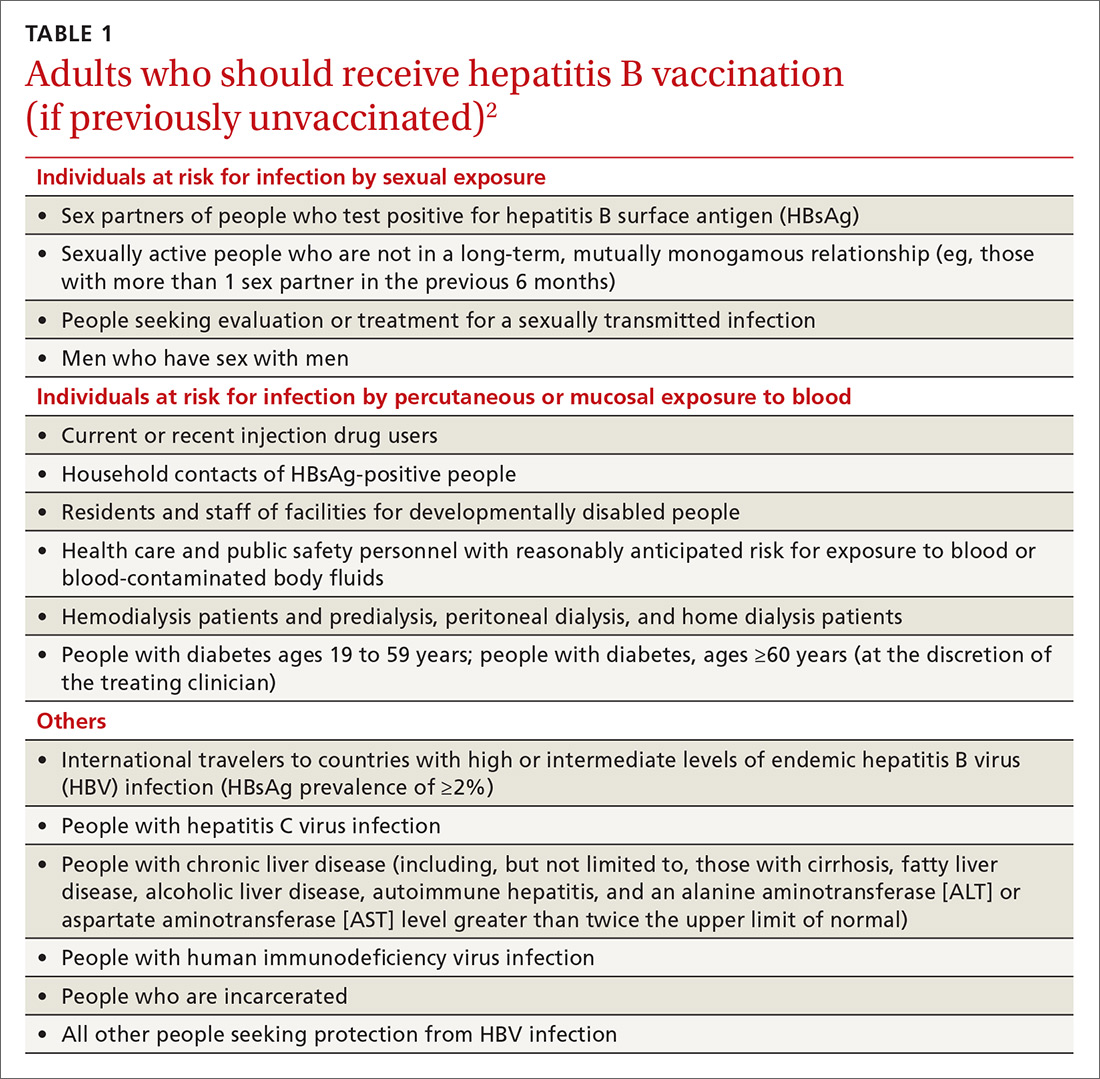

Vaccination rates in the US vary by age group, with higher immunization rates among those born after 1991 than the rates of those born earlier. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1988 to 2012 reported 33% immunity among veterans aged < 50 years and 6% among those aged ≥ 50 years.21 In addition to individuals who received childhood vaccination in the 1990s, all new military recruits assigned to the Korean Peninsula were vaccinated for HBV as of 1986, and those joining the military after 2002 received mandatory vaccination.

The VA follows the ACIP/CDC hepatitis B immunization guidelines.22-24 The VA currently recommends HBV immunization among previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk of contracting HBV infection and for any other adult who is seeking protection from HBV infection. The VA also offers general recommendations for prevention of transmission between veterans with known chronic HBV to their household, sexual, or drug-using partners. Transmission prevention guidelines also provide recommendations for vaccination of pregnant women with HBV risk factors and women at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy.22

HBV Care Guidance

One of the core tasks of the VA National Hepatitis B Working Group, given its broad, multidisciplinary expertise in HBV, was developing general clinical guidelines for the provision of high-quality care for patients with HBV. The group reviewed current literature and scientific evidence on care for patients with HBV. The working group relied heavily on the VA’s national guidelines for HBV screening and immunization, which are based on recommendations from the USPSTF, ACIP, CDC, and professional societies. The professional society guidelines included the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, the America College of Gastroenterology’s Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute’s Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Reactivation during Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy, and CDC’s Guidelines for Screening Pregnant Women for HBV.19,22-27

The working group identified areas for HBV quality improvement that were consistent with the VA and professional guidelines, specific and measurable using VA data, clinically relevant, feasible, and achievable in a defined time period. Areas for targeted improvement will include testing for HBV among high-risk patients, increasing antiviral treatment and HCC surveillance of veterans with HBV-related cirrhosis, decreasing progression of chronic HBV to cirrhosis, and expanding prevention measures, such as immunization among those at high risk for HBV and prevention of HBV reactivation.

At a national level, development of specific and measurable quality of care indicators for HBV will aid in assessing gaps in care and developing strategies to address these gaps. A broader discussion of care for patients with HBV quality with front-line health care providers (HCPs) will be paired with increased education and providing clinical support tools for those HCPs and facilities without access to specialty GI services.

Clinical pharmacists will be critical targets for the dissemination of guidance for HBV care paired with clinical informatics support tools and clinical educational opportunities. As of 2015, there were about 7,700 clinical pharmacists in the VHA and 3,200 had a scope of practice that included prescribing authority. As a result, 20% of HCV prescriptions in the VA in fiscal year 2015

Identification and Monitoring

The HBV working group and the VA Viral Hepatitis Technical Advisory Group are working with field HCPs to develop several informatics tools to promote HBV case identification and quality monitoring. These groups identified several barriers to HBV case identification and monitoring. The following informatics tools are either available or in development to reduce these barriers:

- A local clinical case registry of patients with HBV infection based on ICD codes, which allows users to create custom reports to identify, monitor, and track care;

- Because of the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with chronic HBV infection who receive anti-CD20 agents, such as rituximab, a medication order check to improve HBV screening among veterans receiving anti-CD20 medication;

- Validated patient reports based on laboratory diagnosis of HBV, drawn from all results across the VHA since 1999, made available to all facilities;

- Interactive reports summarizing quality of care for patients with HBV infection, based on facility-level indicators in development by the national HBV working group, will be distributed and enable geographic comparison;

- An HBV immunization clinical reminder that will prompt frontline HCPs to test and vaccinate; and

- An HBV clinical dashboard that will enable HCPs and facilities to identify all their HBV-positive veterans and track their care and outcomes over time.

Evaluating VA Care for Patients with HBV

As indicators of quality of HBV care are refined for VA patients and the health care delivery system, guidance will be made broadly available to frontline HCPs and administrators. The HBV quality of care recommendations will be paired with a suite of clinical informatics tools and virtual educational trainings to ensure that VA HCPs and facilities can streamline care for patients with HBV infection as much as possible. Quality improvement will be measured nationally each year, and strategies to address persistent variability and gaps in care will be developed in collaboration with the VA SME’s, facilities, and HCPs.

Conclusion

Hepatitis B virus is at least as prevalent among veterans who are cared for at VA facilities as it is in the US civilian population. Although care for patients with HBV infection in the VA is similar to care for patients with HBV infection in the community, the VA recognizes areas for improved HBV prevention, testing, care, and treatment. The VA has begun a continuous quality improvement strategic plan to enhance the level of care for patients with HBV infection in VA care. Centralized coordination and communication of VA data combined with veteran- and field-centered policies and operational planning and execution will allow clinically relevant improvements in HBV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention among veterans served by VA.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Hepatitis B is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is transmitted through percutaneous (ie, puncture through the skin) or mucosal (ie, direct contact with mucous membranes) exposure to infectious blood or body fluids. Hepatitis B virus can cause chronic infection, resulting in cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, liver failure, and death. Persons with chronic infection also serve as the main reservoir for continued HBV transmission.1

Individuals at highest risk for infection include those born in geographic regions with a high prevalence of HBV, those with sexual partners or household contacts with chronic HBV infection, men who have sex with men (MSM), those with HIV, and individuals who inject drugs. Pregnant women also are a population of concern given the potential for perinatal transmission.2

About 850,000 to 2.2 million people in the US (about 0.3% of the civilian US population) are chronically infected with HBV.3 The prevalence of chronic HBV is much higher (10%-19%) among Asian Americans, those of Pacific Island descent, and other immigrant populations from highly endemic countries.4 In the US, HBV is responsible for 2,000 to 4,000 preventable deaths annually, primarily from cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatic failure.4 In the civilian US population, reported cases of acute HBV decreased 0.3% from 2011 to 2012, increased 5.4% in 2013 with an 8.5% decrease in 2014, and a 20.7% increase in 2015.4 Injection drug use is likely driving the most recent increase.5

Not all individuals exposed to HBV will develop chronic infection, and the risk of chronic HBV infection depends on an individual’s age at the time of exposure. For example, about 95% of infants exposed to HBV perinatally will develop a chronic infection compared with 5% of exposed adults.6 Of those with chronic HBV, a small proportion will develop cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with increasing risk as viral DNA concentrations increase. Additional risk factors for cirrhosis include being older, male, having a persistently elevated alanine transaminase, viral superinfections, HBV reversion/reactivation, genotype, and various markers of disease severity (HCC).6 Of note, chronic HBV infection may cause HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.7 In addition, immunosuppression (eg, from cancer chemotherapy) may allow HBV reactivation, which may result in fulminant hepatic failure. In the Veterans Health Affairs (VHA) health care system, about 17% of those with known chronic HBV also carry a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Vaccination is the mainstay of efforts to prevent HBV infection. The first commercially available HBV vaccine was approved by the FDA in 1981, with subsequent FDA approval in 1986 of a vaccine manufactured using recombinant DNA technology.8 In 1991, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended universal childhood vaccination for HBV, with subsequent recommendations for vaccination of adolescents and adults in high-risk groups in 1995, and in 1999 all remaining unvaccinated children aged ≤ 19 years.9 Military policy has been to provide hepatitis B immunization to personnel assigned to the Korean peninsula since 1986 and to all recruits since 2001.10

Following publication of an Institute of Medicine/National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report, in 2011 the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released the first National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.11 The current HHS Action Plan, along with the NASEM National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report, commissioned by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), outlines a national strategy to prevent new viral hepatitis infections; reduce deaths and improve the health of people living with viral hepatitis; reduce viral hepatitis health disparities; and coordinate, monitor, and report on implementation of viral hepatitis activities.12 The VA is a critical partner in this federal collaborative effort to achieve excellence in viral hepatitis care.

In August 2016, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs in the VA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a National Hepatitis B Working Group consisting of VA subject matter experts (SMEs) and representatives from the VA Central Office stakeholder program offices, with a charge of developing a strategic plan to ensure excellence in HBV prevention, care, and management across the VHA. The task included addressing supportive processes and barriers at each level of the organization through a public health framework and using a population health management approach.

The VA National Strategic Plan for Excellence in HBV Care was focused on the following overarching aims:

- Characterizing the current state of care for veterans with HBV in VA care;

- Developing and disseminating clinical guidance on high-quality care for patients with HBV;

- Developing population data and informatics tools to streamline the identification and monitoring of patients with chronic HBV; and

- Evaluating VHA care for patients with HBV over time.

Care for Veterans With HBV at the VA

The VA health care system is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at 1,243 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1,063 outpatient sites of care serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.13 As of January 2018, there were 10,743 individuals with serologic evidence for chronic HBV infection in VA care, based on a definition of 2 or more detectable surface antigen (sAg) or hepatitis B DNA tests recorded at least 6 months apart.1 About 2,000 additional VA patients have a history of a single positive sAg test. These patients have unclear HBV status and require a second sAg test to determine whether they have a chronic infection.

The prevalence of HBV infection among veterans in VA care is slightly higher than that in the US civilian population at 0.4%.14 Studies of selected subpopulations of veterans have found high seropositivity of prior or chronic HBV infection among homeless veterans and veterans admitted to a psychiatric hospital.15,16 The data from 2015 suggest that homeless veterans have a chronic HBV infection rate of 1.0%.14 Of those with known chronic HBV infection, the plurality are white (40.4%) or African American (40.2%), male (92.4%), with a mean age of 59.9 (SD 12.0) years. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, the geographic territories with the largest chronic HBV caseload include the Southeast, Gulf Coast, and West Coast. As of January 2018, 1,210 veterans in care have HBV-related cirrhosis.

HBV Screening in VA

The current VA HBV screening guidelines follow those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).17 HBV screening is recommended for unvaccinated individuals in high-risk groups, such as patients with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV), those on hemodialysis, those with elevated alanine transaminase/aspartate transaminase of unknown etiology, those on immunosuppressive therapy, injection drug users, the MSM population, people with household contact with an HBV-infected person, people born to an HBV-infected mother, those with risk factors for HBV exposure prior to vaccination, pregnant women, and people born in highly endemic areas regardless of vaccination status.2 The VHA recommends against standardized risk assessment and laboratory screening for HBV infection in the asymptomatic general patient population. However, if risk factors become known during the course of providing usual clinical care, then laboratory screening should be considered.2

Of the 6.1 million VHA users

HBV Care and VA Antiviral Treatment

In a study of an HBV care cascade, Serper and colleagues reviewed a cohort of veterans in the VA with HBV. About 50% of the patients with known chronic HBV in the VA system from 1999 to 2013 had received infectious diseases or gastroenterology/hepatology specialty care in the previous 2 years.19 Follow-up data from the National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group indicated that this remains the case: 52.3% of patients with documented chronic HBV had received specialty care from VA sources in the prior 2 years. Serper and colleagues also reported that among veterans in VHA care with chronic HBV infection and cirrhosis from 1999 to 2013, annual imaging was < 50%, and initiation of antiviral treatment was only 39%. Antiviral therapy and liver imaging were both independently associated with lower mortality for patients with HBV and cirrhosis.19

A review of studies that evaluated the delivery of care for patients with HBV in U.S. civilian populations, including retrospective reviews of private payer claims databases and chart reviews, the Kaiser Permanente claims database, and community gastrointestinal (GI) practice chart reviews, revealed similar practice patterns with those in the VA.20 Across the US, rates of antiviral therapy and HCC surveillance for those with HBV cirrhosis were low, ranging from 14% to 50% and 19% to 60%, respectively. Several of these studies also found that being seen by an HBV specialist was associated with improved care.20

Antiviral treatment of individuals with cirrhosis and chronic HBV infection can reduce the risk of progression to decompensated cirrhosis and liver cancer. Among current VA patients with HBV cirrhosis, 62.4% received at least 1 month of HBV antiviral medication in the prior year. Additionally, biannual liver imaging is recommended in this population to screen for the development of HCC. According to National HIV, Hepatitis and Related Conditions Data and Analysis Group personal correspondence, nationally, 51.2% of individuals with HBV cirrhosis had received at least one instance of liver imaging within the past 6 months, and 71.2% received imaging within the past 12 months.

Prevention of HBV Infection and Sequelae

Vaccination rates in the US vary by age group, with higher immunization rates among those born after 1991 than the rates of those born earlier. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1988 to 2012 reported 33% immunity among veterans aged < 50 years and 6% among those aged ≥ 50 years.21 In addition to individuals who received childhood vaccination in the 1990s, all new military recruits assigned to the Korean Peninsula were vaccinated for HBV as of 1986, and those joining the military after 2002 received mandatory vaccination.

The VA follows the ACIP/CDC hepatitis B immunization guidelines.22-24 The VA currently recommends HBV immunization among previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk of contracting HBV infection and for any other adult who is seeking protection from HBV infection. The VA also offers general recommendations for prevention of transmission between veterans with known chronic HBV to their household, sexual, or drug-using partners. Transmission prevention guidelines also provide recommendations for vaccination of pregnant women with HBV risk factors and women at risk for HBV infection during pregnancy.22

HBV Care Guidance

One of the core tasks of the VA National Hepatitis B Working Group, given its broad, multidisciplinary expertise in HBV, was developing general clinical guidelines for the provision of high-quality care for patients with HBV. The group reviewed current literature and scientific evidence on care for patients with HBV. The working group relied heavily on the VA’s national guidelines for HBV screening and immunization, which are based on recommendations from the USPSTF, ACIP, CDC, and professional societies. The professional society guidelines included the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease’s Guidelines for Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B, the America College of Gastroenterology’s Practice Guidelines: Evaluation of Abnormal Liver Chemistries, the American Gastroenterological Association Institute’s Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis B Reactivation during Immunosuppressive Drug Therapy, and CDC’s Guidelines for Screening Pregnant Women for HBV.19,22-27