User login

Human papillomavirus

To the Editor: I am an active primary care provider. After reading the update on human papillomavirus (HPV) in the March 2019 issue by Zhang and Batur,1 I was hoping for some clarification on a few points.

The statement is made that up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. I have pulled the reference2 but cannot find supporting data for this claim. Is this proven or optimistic thinking based on the decreased incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results such as noted in the University of New Mexico HPV Pap registry database3? The authors do cite an additional reference4 documenting a decreased incidence of cervical cancer in the United States among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 compared with 2011–2014. This study reported a 29% relative risk reduction in the group receiving the vaccine, with the absolute numbers 6 vs 8.4 cases per 1,000,000. Thus, can the authors provide further references to the statement that 70% of cervical cancers can be prevented by vaccination?

The authors also state that vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions. At first this shocked me, but then made me pause and wonder how often I do that—and when I do, why. I regularly do it with all the other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When the parent or patient asks for further information, I am armed to provide it. To date, I am struggling to provide data to educate the patient on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, particularly the claim that it will prevent 70% of cervical cancers. Are there more data that I am missing?

Finally, let me state that I am a “vaccinator”—always have been, and always will be. I discuss the HPV vaccine with my patients and their parents and try to provide data to support my recommendation. However, I am concerned that this current practice regarding the HPV vaccine has been driven by scare tactics and has now turned to “just give it because I say so.” The University of New Mexico Center for HPV prevention reports up to a 50% reduction in cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (precancer lesions) in teens.3 This is exciting information and raises hope for the future successful battle against cervical cancer. I think it is also more accurate than stating to parents and patients that we have proof that we have prevented 70% of cervical cancers. When we explain it in this manner, the majority of parents and patients buy in and, I believe, enjoy and welcome this open-ended discussion.

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: an update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3): 469-477.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(6):833–837. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

To the Editor: I am an active primary care provider. After reading the update on human papillomavirus (HPV) in the March 2019 issue by Zhang and Batur,1 I was hoping for some clarification on a few points.

The statement is made that up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. I have pulled the reference2 but cannot find supporting data for this claim. Is this proven or optimistic thinking based on the decreased incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results such as noted in the University of New Mexico HPV Pap registry database3? The authors do cite an additional reference4 documenting a decreased incidence of cervical cancer in the United States among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 compared with 2011–2014. This study reported a 29% relative risk reduction in the group receiving the vaccine, with the absolute numbers 6 vs 8.4 cases per 1,000,000. Thus, can the authors provide further references to the statement that 70% of cervical cancers can be prevented by vaccination?

The authors also state that vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions. At first this shocked me, but then made me pause and wonder how often I do that—and when I do, why. I regularly do it with all the other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When the parent or patient asks for further information, I am armed to provide it. To date, I am struggling to provide data to educate the patient on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, particularly the claim that it will prevent 70% of cervical cancers. Are there more data that I am missing?

Finally, let me state that I am a “vaccinator”—always have been, and always will be. I discuss the HPV vaccine with my patients and their parents and try to provide data to support my recommendation. However, I am concerned that this current practice regarding the HPV vaccine has been driven by scare tactics and has now turned to “just give it because I say so.” The University of New Mexico Center for HPV prevention reports up to a 50% reduction in cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (precancer lesions) in teens.3 This is exciting information and raises hope for the future successful battle against cervical cancer. I think it is also more accurate than stating to parents and patients that we have proof that we have prevented 70% of cervical cancers. When we explain it in this manner, the majority of parents and patients buy in and, I believe, enjoy and welcome this open-ended discussion.

To the Editor: I am an active primary care provider. After reading the update on human papillomavirus (HPV) in the March 2019 issue by Zhang and Batur,1 I was hoping for some clarification on a few points.

The statement is made that up to 70% of HPV-related cervical cancer cases can be prevented with vaccination. I have pulled the reference2 but cannot find supporting data for this claim. Is this proven or optimistic thinking based on the decreased incidence of abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test results such as noted in the University of New Mexico HPV Pap registry database3? The authors do cite an additional reference4 documenting a decreased incidence of cervical cancer in the United States among 15- to 24-year-olds from 2003–2006 compared with 2011–2014. This study reported a 29% relative risk reduction in the group receiving the vaccine, with the absolute numbers 6 vs 8.4 cases per 1,000,000. Thus, can the authors provide further references to the statement that 70% of cervical cancers can be prevented by vaccination?

The authors also state that vaccine acceptance rates are highest when primary care providers announce that the vaccine is due rather than invite open-ended discussions. At first this shocked me, but then made me pause and wonder how often I do that—and when I do, why. I regularly do it with all the other vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When the parent or patient asks for further information, I am armed to provide it. To date, I am struggling to provide data to educate the patient on the efficacy of the HPV vaccine, particularly the claim that it will prevent 70% of cervical cancers. Are there more data that I am missing?

Finally, let me state that I am a “vaccinator”—always have been, and always will be. I discuss the HPV vaccine with my patients and their parents and try to provide data to support my recommendation. However, I am concerned that this current practice regarding the HPV vaccine has been driven by scare tactics and has now turned to “just give it because I say so.” The University of New Mexico Center for HPV prevention reports up to a 50% reduction in cervical intraepithelial neoplasias (precancer lesions) in teens.3 This is exciting information and raises hope for the future successful battle against cervical cancer. I think it is also more accurate than stating to parents and patients that we have proof that we have prevented 70% of cervical cancers. When we explain it in this manner, the majority of parents and patients buy in and, I believe, enjoy and welcome this open-ended discussion.

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: an update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3): 469-477.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(6):833–837. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: an update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3): 469-477.

- Benard VB, Castle PE, Jenison SA, et al. Population-based incidence rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in the human papillomavirus vaccine era. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(6):833–837. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3609

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young US females after human papillomavirus vaccine introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

In reply: Human papillomavirus

In Reply: We would like to thank Dr. Lichtenberg for giving us the opportunity to clarify and expand on questions regarding HPV vaccine efficacy.

Our statement “HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts” was based on a statement by Thaxton and Waxman, ie, that immunization against HPV types 16 and 18 has the potential to prevent 70% of cancers of the cervix plus a large percentage of other lower anogenital tract cancers.1 This was meant to describe the prevention potential of the quadrivalent vaccine. The currently available Gardasil 9 targets the HPV types that account for 90% of cervical cancers,2 with projected effectiveness likely to vary based on geographic variation in HPV subtypes, ranging from 86.5% in Australia to 92% in North America.3 It is difficult to precisely calculate the effectiveness of HPV vaccination alone, given that cervical cancer prevention is twofold, with primary vaccination and secondary screening (with several notable updates to US national screening guidelines during the same time frame as vaccine development).4

It is true that the 29% decrease in US cervical cancer incidence rates during the years 2011–2014 compared with 2003–2006 is less than the predicted 70%.5 However, not all eligible US females are vaccinated; according to reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 49% of adolescents were appropriately immunized against HPV in 2017, an increase over the rate of only 35% in 2014.6 Low vaccination rates undoubtedly negatively impact any benefits from herd immunity, though the exact benefits of this population immunity are difficult to quantify.7

In Australia, a national school-based HPV vaccination program was initiated in 2007, making the vaccine available for free. Over 70% of girls ages 12 and 13 were vaccinated, and follow-up within the same decade showed a greater than 90% reduction in genital warts, as well as a reduction in high-grade cervical lesions.8 In addition, the incidence of genital warts in unvaccinated heterosexual males during the prevaccination vs the vaccination period decreased by up to 81% (a marker of herd immunity).9

In the US, the HPV subtypes found in the quadrivalent vaccine decreased by 71% in those ages 14 to 19, within 8 years of vaccine introduction.10 An analysis of US state cancer registries between 2009 and 2012 showed that in Michigan, the rates of high-grade, precancerous lesions declined by 37% each year for women ages 15 to 19, thought to be due to changes in screening and vaccination guidelines.11 Similarly, an analysis of 9 million privately insured US females showed that the presence of high-grade precancerous lesions significantly decreased between the years 2007 and 2014 in those ages 15 to 24 (vaccinated individuals), but not in those ages 25 to 39 (unvaccinated individuals).12 Most recently, a study of 10,206 women showed a 21.9% decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse lesions due to HPV subtypes 16 or 18 in those who have received at least 1 dose of the vaccine; reduced rates in unvaccinated women were also seen, representing first evidence of herd immunity in the United States.13 In contrast, the rates of high-grade lesions due to nonvaccine HPV subtypes remained constant. Given that progression to cervical cancer can take 10 to 15 years or longer after HPV infection, true vaccine benefits will emerge once increased vaccination rates are achieved and after at least a decade of follow-up.

We applaud Dr. Lichtenberg’s efforts to clarify vaccine efficacy for appropriate counseling, as this is key to ensuring patient trust. Immunization fears have fueled the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses across the world. Given the wave of vaccine misinformation on the Internet, we all face patients and family members skeptical of vaccine efficacy and safety. Those requesting more information deserve an honest, informed discussion with their provider. Interestingly, however, among 955 unvaccinated women, the belief of not being at risk for HPV was the most common reason for not receiving the vaccine.14 Effective education can be achieved by focusing on the personal risks of HPV to the patient, as well as the overall favorable risk vs benefits of vaccination. Quoting an exact rate of cancer reduction is likely a less effective counseling strategy, and these efficacy estimates will change as vaccination rates and HPV prevalence within the population change over time.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: Immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JM, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016 Jun;130:101–109. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young U.S. females after human papillomavirus vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) coverage data. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vacc-coverage/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Nymark LS, Sharma T, Miller A, Enemark U, Griffiths UK. Inclusion of the value of herd immunity in economic evaluations of vaccines. A systematic review of methods used. Vaccine 2017; 35(49 Pt B):6828–6841. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.024

- Garland SM. The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clin Ther 2014; 36(1):17–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346:f2032. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2032

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(5):594–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix244

- Watson M, Soman A, Flagg EW, et al. Surveillance of high-grade cervical cancer precursors (CIN III/AIS) in four population-based cancer registries. Prev Med 2017; 103:60–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.027

- Flagg EW, Torrone EA, Weinstock H. Ecological association of human papillomavirus vaccination with cervical dysplasia prevalence in the United States, 2007–2014. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(12):2211–2218.

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Bennett NM, et al; HPV-IMPACT Working Group. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008–2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(3):602–609. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0885

- Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine 2012; 30(16):2676–2682. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007

In Reply: We would like to thank Dr. Lichtenberg for giving us the opportunity to clarify and expand on questions regarding HPV vaccine efficacy.

Our statement “HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts” was based on a statement by Thaxton and Waxman, ie, that immunization against HPV types 16 and 18 has the potential to prevent 70% of cancers of the cervix plus a large percentage of other lower anogenital tract cancers.1 This was meant to describe the prevention potential of the quadrivalent vaccine. The currently available Gardasil 9 targets the HPV types that account for 90% of cervical cancers,2 with projected effectiveness likely to vary based on geographic variation in HPV subtypes, ranging from 86.5% in Australia to 92% in North America.3 It is difficult to precisely calculate the effectiveness of HPV vaccination alone, given that cervical cancer prevention is twofold, with primary vaccination and secondary screening (with several notable updates to US national screening guidelines during the same time frame as vaccine development).4

It is true that the 29% decrease in US cervical cancer incidence rates during the years 2011–2014 compared with 2003–2006 is less than the predicted 70%.5 However, not all eligible US females are vaccinated; according to reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 49% of adolescents were appropriately immunized against HPV in 2017, an increase over the rate of only 35% in 2014.6 Low vaccination rates undoubtedly negatively impact any benefits from herd immunity, though the exact benefits of this population immunity are difficult to quantify.7

In Australia, a national school-based HPV vaccination program was initiated in 2007, making the vaccine available for free. Over 70% of girls ages 12 and 13 were vaccinated, and follow-up within the same decade showed a greater than 90% reduction in genital warts, as well as a reduction in high-grade cervical lesions.8 In addition, the incidence of genital warts in unvaccinated heterosexual males during the prevaccination vs the vaccination period decreased by up to 81% (a marker of herd immunity).9

In the US, the HPV subtypes found in the quadrivalent vaccine decreased by 71% in those ages 14 to 19, within 8 years of vaccine introduction.10 An analysis of US state cancer registries between 2009 and 2012 showed that in Michigan, the rates of high-grade, precancerous lesions declined by 37% each year for women ages 15 to 19, thought to be due to changes in screening and vaccination guidelines.11 Similarly, an analysis of 9 million privately insured US females showed that the presence of high-grade precancerous lesions significantly decreased between the years 2007 and 2014 in those ages 15 to 24 (vaccinated individuals), but not in those ages 25 to 39 (unvaccinated individuals).12 Most recently, a study of 10,206 women showed a 21.9% decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse lesions due to HPV subtypes 16 or 18 in those who have received at least 1 dose of the vaccine; reduced rates in unvaccinated women were also seen, representing first evidence of herd immunity in the United States.13 In contrast, the rates of high-grade lesions due to nonvaccine HPV subtypes remained constant. Given that progression to cervical cancer can take 10 to 15 years or longer after HPV infection, true vaccine benefits will emerge once increased vaccination rates are achieved and after at least a decade of follow-up.

We applaud Dr. Lichtenberg’s efforts to clarify vaccine efficacy for appropriate counseling, as this is key to ensuring patient trust. Immunization fears have fueled the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses across the world. Given the wave of vaccine misinformation on the Internet, we all face patients and family members skeptical of vaccine efficacy and safety. Those requesting more information deserve an honest, informed discussion with their provider. Interestingly, however, among 955 unvaccinated women, the belief of not being at risk for HPV was the most common reason for not receiving the vaccine.14 Effective education can be achieved by focusing on the personal risks of HPV to the patient, as well as the overall favorable risk vs benefits of vaccination. Quoting an exact rate of cancer reduction is likely a less effective counseling strategy, and these efficacy estimates will change as vaccination rates and HPV prevalence within the population change over time.

In Reply: We would like to thank Dr. Lichtenberg for giving us the opportunity to clarify and expand on questions regarding HPV vaccine efficacy.

Our statement “HPV immunization can prevent up to 70% of cases of cervical cancer due to HPV as well as 90% of genital warts” was based on a statement by Thaxton and Waxman, ie, that immunization against HPV types 16 and 18 has the potential to prevent 70% of cancers of the cervix plus a large percentage of other lower anogenital tract cancers.1 This was meant to describe the prevention potential of the quadrivalent vaccine. The currently available Gardasil 9 targets the HPV types that account for 90% of cervical cancers,2 with projected effectiveness likely to vary based on geographic variation in HPV subtypes, ranging from 86.5% in Australia to 92% in North America.3 It is difficult to precisely calculate the effectiveness of HPV vaccination alone, given that cervical cancer prevention is twofold, with primary vaccination and secondary screening (with several notable updates to US national screening guidelines during the same time frame as vaccine development).4

It is true that the 29% decrease in US cervical cancer incidence rates during the years 2011–2014 compared with 2003–2006 is less than the predicted 70%.5 However, not all eligible US females are vaccinated; according to reports from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 49% of adolescents were appropriately immunized against HPV in 2017, an increase over the rate of only 35% in 2014.6 Low vaccination rates undoubtedly negatively impact any benefits from herd immunity, though the exact benefits of this population immunity are difficult to quantify.7

In Australia, a national school-based HPV vaccination program was initiated in 2007, making the vaccine available for free. Over 70% of girls ages 12 and 13 were vaccinated, and follow-up within the same decade showed a greater than 90% reduction in genital warts, as well as a reduction in high-grade cervical lesions.8 In addition, the incidence of genital warts in unvaccinated heterosexual males during the prevaccination vs the vaccination period decreased by up to 81% (a marker of herd immunity).9

In the US, the HPV subtypes found in the quadrivalent vaccine decreased by 71% in those ages 14 to 19, within 8 years of vaccine introduction.10 An analysis of US state cancer registries between 2009 and 2012 showed that in Michigan, the rates of high-grade, precancerous lesions declined by 37% each year for women ages 15 to 19, thought to be due to changes in screening and vaccination guidelines.11 Similarly, an analysis of 9 million privately insured US females showed that the presence of high-grade precancerous lesions significantly decreased between the years 2007 and 2014 in those ages 15 to 24 (vaccinated individuals), but not in those ages 25 to 39 (unvaccinated individuals).12 Most recently, a study of 10,206 women showed a 21.9% decrease in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse lesions due to HPV subtypes 16 or 18 in those who have received at least 1 dose of the vaccine; reduced rates in unvaccinated women were also seen, representing first evidence of herd immunity in the United States.13 In contrast, the rates of high-grade lesions due to nonvaccine HPV subtypes remained constant. Given that progression to cervical cancer can take 10 to 15 years or longer after HPV infection, true vaccine benefits will emerge once increased vaccination rates are achieved and after at least a decade of follow-up.

We applaud Dr. Lichtenberg’s efforts to clarify vaccine efficacy for appropriate counseling, as this is key to ensuring patient trust. Immunization fears have fueled the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable illnesses across the world. Given the wave of vaccine misinformation on the Internet, we all face patients and family members skeptical of vaccine efficacy and safety. Those requesting more information deserve an honest, informed discussion with their provider. Interestingly, however, among 955 unvaccinated women, the belief of not being at risk for HPV was the most common reason for not receiving the vaccine.14 Effective education can be achieved by focusing on the personal risks of HPV to the patient, as well as the overall favorable risk vs benefits of vaccination. Quoting an exact rate of cancer reduction is likely a less effective counseling strategy, and these efficacy estimates will change as vaccination rates and HPV prevalence within the population change over time.

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: Immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JM, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016 Jun;130:101–109. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young U.S. females after human papillomavirus vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) coverage data. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vacc-coverage/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Nymark LS, Sharma T, Miller A, Enemark U, Griffiths UK. Inclusion of the value of herd immunity in economic evaluations of vaccines. A systematic review of methods used. Vaccine 2017; 35(49 Pt B):6828–6841. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.024

- Garland SM. The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clin Ther 2014; 36(1):17–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346:f2032. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2032

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(5):594–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix244

- Watson M, Soman A, Flagg EW, et al. Surveillance of high-grade cervical cancer precursors (CIN III/AIS) in four population-based cancer registries. Prev Med 2017; 103:60–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.027

- Flagg EW, Torrone EA, Weinstock H. Ecological association of human papillomavirus vaccination with cervical dysplasia prevalence in the United States, 2007–2014. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(12):2211–2218.

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Bennett NM, et al; HPV-IMPACT Working Group. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008–2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(3):602–609. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0885

- Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine 2012; 30(16):2676–2682. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007

- Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: Immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99(3):469–477. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.003

- McNamara M, Batur P, Walsh JM, Johnson KM. HPV update: vaccination, screening, and associated disease. J Gen Intern Med 2016; 31(11):1360–1366. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3725-z

- Zhai L, Tumban E. Gardasil-9: A global survey of projected efficacy. Antiviral Res 2016 Jun;130:101–109. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.03.016

- Zhang S, Batur P. Human papillomavirus in 2019: An update on cervical cancer prevention and screening guidelines. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86(3):173–178. doi:10.3949/ccjm.86a.18018

- Guo F, Cofie LE, Berenson AB. Cervical cancer incidence in young U.S. females after human papillomavirus vaccine Introduction. Am J Prev Med 2018; 55(2):197–204. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.013

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) coverage data. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vacc-coverage/index.html. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Nymark LS, Sharma T, Miller A, Enemark U, Griffiths UK. Inclusion of the value of herd immunity in economic evaluations of vaccines. A systematic review of methods used. Vaccine 2017; 35(49 Pt B):6828–6841. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.024

- Garland SM. The Australian experience with the human papillomavirus vaccine. Clin Ther 2014; 36(1):17–23. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.12.005

- Ali H, Donovan B, Wand H, et al. Genital warts in young Australians five years into national human papillomavirus vaccination programme: national surveillance data. BMJ 2013; 346:f2032. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2032

- Oliver SE, Unger ER, Lewis R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among females after vaccine introduction—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2003–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(5):594–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix244

- Watson M, Soman A, Flagg EW, et al. Surveillance of high-grade cervical cancer precursors (CIN III/AIS) in four population-based cancer registries. Prev Med 2017; 103:60–65. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.07.027

- Flagg EW, Torrone EA, Weinstock H. Ecological association of human papillomavirus vaccination with cervical dysplasia prevalence in the United States, 2007–2014. Am J Public Health 2016; 106(12):2211–2218.

- McClung NM, Gargano JW, Bennett NM, et al; HPV-IMPACT Working Group. Trends in human papillomavirus vaccine types 16 and 18 in cervical precancers, 2008–2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019; 28(3):602–609. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0885

- Liddon NC, Hood JE, Leichliter JS. Intent to receive HPV vaccine and reasons for not vaccinating among unvaccinated adolescent and young women: findings from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Vaccine 2012; 30(16):2676–2682. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.007

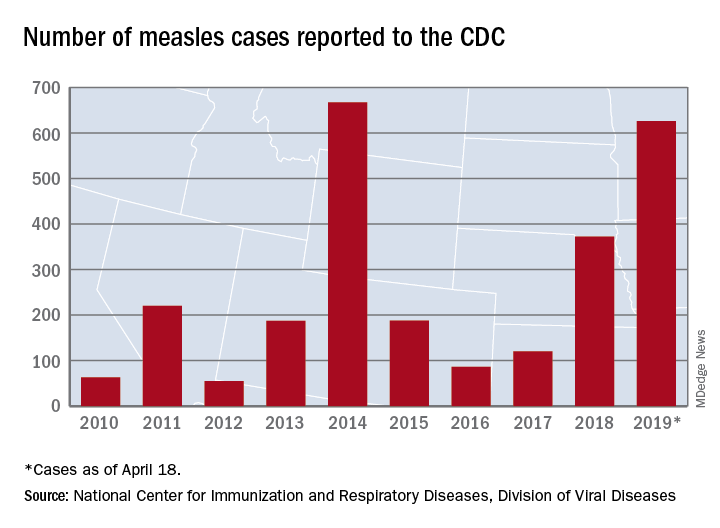

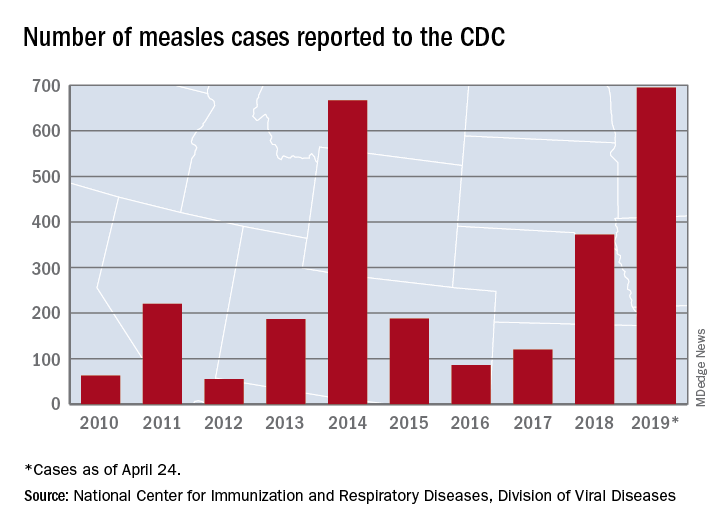

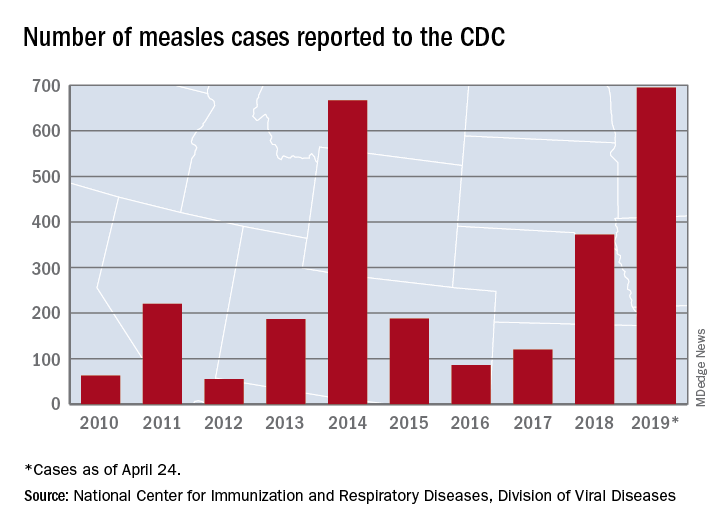

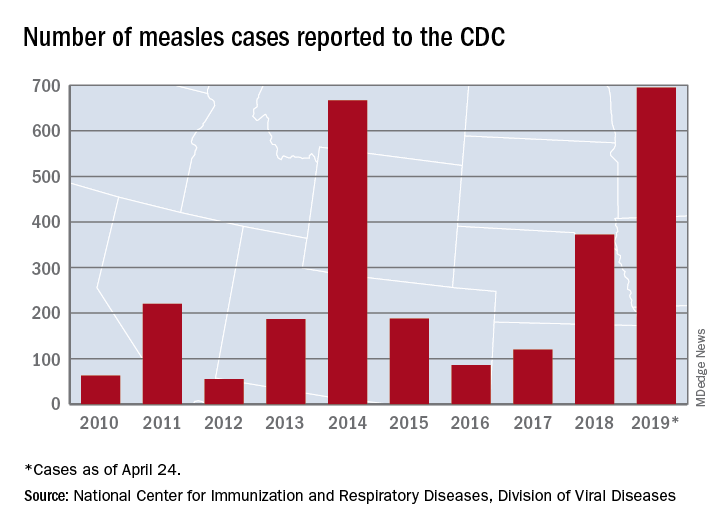

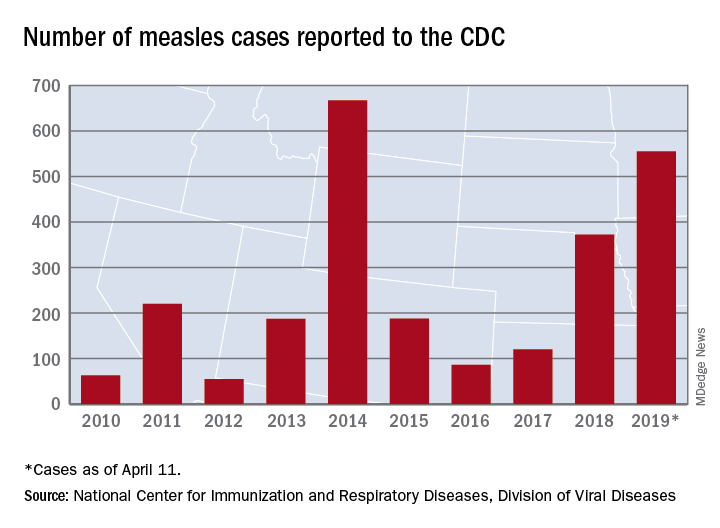

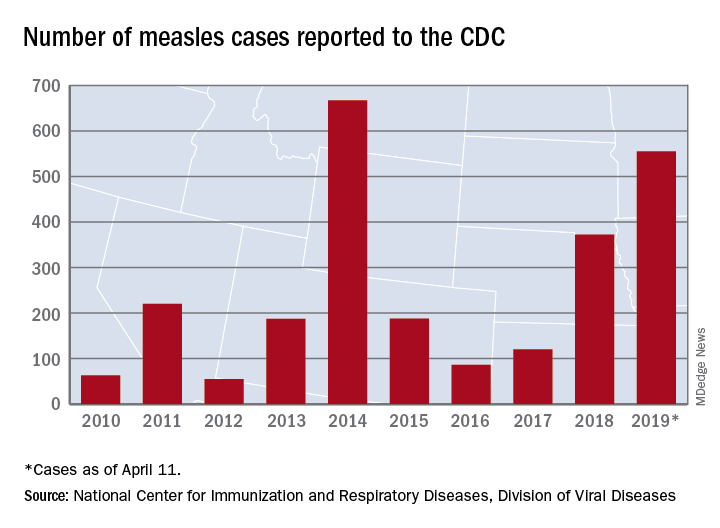

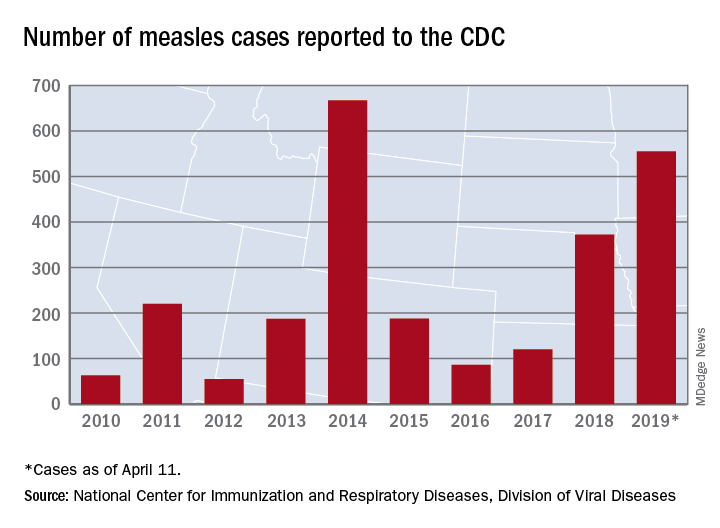

Measles cases for 2019 now at postelimination high

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of Wednesday, April 24, the case count for measles is 695, which eclipses the mark of 667 cases that had been the highest since the disease was declared to be eliminated from this country in 2000, the CDC reported.

“The high number of cases in 2019 is primarily the result of a few large outbreaks – one in Washington State and two large outbreaks in New York that started in late 2018. The outbreaks in New York City and New York State are among the largest and longest lasting since measles elimination in 2000. The longer these outbreaks continue, the greater the chance measles will again get a sustained foothold in the United States,” according to a written statement by the CDC.

Although these outbreaks began when the virus was brought into this country by unvaccinated travelers from other countries where there is widespread transmission, “a significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine. Some organizations are deliberately targeting these communities with inaccurate and misleading information about vaccines,” according to the statement.

“Measles is not a harmless childhood illness, but a highly contagious, potentially life-threatening disease,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a separate statement. “We have the ability to safely protect our children and our communities. Vaccines are a safe, highly effective public health solution that can prevent this disease. The measles vaccines are among the most extensively studied medical products we have, and their safety has been firmly established over many years in some of the largest vaccine studies ever undertaken. With a safe and effective vaccine that protects against measles, the suffering we are seeing is avoidable.”

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of Wednesday, April 24, the case count for measles is 695, which eclipses the mark of 667 cases that had been the highest since the disease was declared to be eliminated from this country in 2000, the CDC reported.

“The high number of cases in 2019 is primarily the result of a few large outbreaks – one in Washington State and two large outbreaks in New York that started in late 2018. The outbreaks in New York City and New York State are among the largest and longest lasting since measles elimination in 2000. The longer these outbreaks continue, the greater the chance measles will again get a sustained foothold in the United States,” according to a written statement by the CDC.

Although these outbreaks began when the virus was brought into this country by unvaccinated travelers from other countries where there is widespread transmission, “a significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine. Some organizations are deliberately targeting these communities with inaccurate and misleading information about vaccines,” according to the statement.

“Measles is not a harmless childhood illness, but a highly contagious, potentially life-threatening disease,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a separate statement. “We have the ability to safely protect our children and our communities. Vaccines are a safe, highly effective public health solution that can prevent this disease. The measles vaccines are among the most extensively studied medical products we have, and their safety has been firmly established over many years in some of the largest vaccine studies ever undertaken. With a safe and effective vaccine that protects against measles, the suffering we are seeing is avoidable.”

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of Wednesday, April 24, the case count for measles is 695, which eclipses the mark of 667 cases that had been the highest since the disease was declared to be eliminated from this country in 2000, the CDC reported.

“The high number of cases in 2019 is primarily the result of a few large outbreaks – one in Washington State and two large outbreaks in New York that started in late 2018. The outbreaks in New York City and New York State are among the largest and longest lasting since measles elimination in 2000. The longer these outbreaks continue, the greater the chance measles will again get a sustained foothold in the United States,” according to a written statement by the CDC.

Although these outbreaks began when the virus was brought into this country by unvaccinated travelers from other countries where there is widespread transmission, “a significant factor contributing to the outbreaks in New York is misinformation in the communities about the safety of the measles/mumps/rubella vaccine. Some organizations are deliberately targeting these communities with inaccurate and misleading information about vaccines,” according to the statement.

“Measles is not a harmless childhood illness, but a highly contagious, potentially life-threatening disease,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a separate statement. “We have the ability to safely protect our children and our communities. Vaccines are a safe, highly effective public health solution that can prevent this disease. The measles vaccines are among the most extensively studied medical products we have, and their safety has been firmly established over many years in some of the largest vaccine studies ever undertaken. With a safe and effective vaccine that protects against measles, the suffering we are seeing is avoidable.”

Gaps exist in rotavirus vaccination coverage in young U.S. children

falling short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% complete vaccination, according to Bethany K. Sederdahl, MPH, and her associates at Emory University, Atlanta.

In an analysis published in Pediatrics of data from 14,571 children included in the 2014 National Immunization Survey, 71% of children received full vaccination for rotavirus, 15% received partial vaccination, and 14% received no vaccination. Children whose mothers were not college graduates, lived in households with at least four children, or were uninsured at any point had an increased likelihood of being unvaccinated; African American children also faced an increased risk of being unvaccinated.

Among the unvaccinated, 72% had at least one missed opportunity according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices schedule, and 83% had at least one missed opportunity according to the World Health Organization schedule. For the partially vaccinated, 54% at least one missed opportunity according to the ACIP schedule, and 96% had at least one missed opportunity according to the WHO schedule. While poorer socioeconomic conditions were associated with the risk of being unvaccinated, children who were partially vaccinated and who missed vaccination opportunities according to the ACIP-recommended schedule were more likely to have mothers with a college degree or an income of more than $75,000.

According to the investigators, if all missed opportunities for vaccination according to the ACIP schedule were addressed, coverage would improve from 71% to 81%; if all opportunities according to the WHO schedule were addressed, coverage would increase to 94%.

“Low rotavirus vaccine uptake may be attributable to both socioeconomic barriers and possibly vaccine hesitancy. Understanding the barriers to rotavirus vaccine uptake and developing effective public health measures to promote vaccine use will be essential to reducing rotavirus morbidity in the United States,” Ms. Sederdahl and her associates wrote.

The study received no external funding. One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from AbbVie, funds to conduct clinical research from Merck, and that his institution receives funds to conduct clinical research from MedImmune, Regeneron, PaxVax, Pfizer, Merck, Novavax, Sanofi Pasteur, and Micron Technology.

SOURCE: Sederdahl BK et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2498.

falling short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% complete vaccination, according to Bethany K. Sederdahl, MPH, and her associates at Emory University, Atlanta.

In an analysis published in Pediatrics of data from 14,571 children included in the 2014 National Immunization Survey, 71% of children received full vaccination for rotavirus, 15% received partial vaccination, and 14% received no vaccination. Children whose mothers were not college graduates, lived in households with at least four children, or were uninsured at any point had an increased likelihood of being unvaccinated; African American children also faced an increased risk of being unvaccinated.

Among the unvaccinated, 72% had at least one missed opportunity according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices schedule, and 83% had at least one missed opportunity according to the World Health Organization schedule. For the partially vaccinated, 54% at least one missed opportunity according to the ACIP schedule, and 96% had at least one missed opportunity according to the WHO schedule. While poorer socioeconomic conditions were associated with the risk of being unvaccinated, children who were partially vaccinated and who missed vaccination opportunities according to the ACIP-recommended schedule were more likely to have mothers with a college degree or an income of more than $75,000.

According to the investigators, if all missed opportunities for vaccination according to the ACIP schedule were addressed, coverage would improve from 71% to 81%; if all opportunities according to the WHO schedule were addressed, coverage would increase to 94%.

“Low rotavirus vaccine uptake may be attributable to both socioeconomic barriers and possibly vaccine hesitancy. Understanding the barriers to rotavirus vaccine uptake and developing effective public health measures to promote vaccine use will be essential to reducing rotavirus morbidity in the United States,” Ms. Sederdahl and her associates wrote.

The study received no external funding. One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from AbbVie, funds to conduct clinical research from Merck, and that his institution receives funds to conduct clinical research from MedImmune, Regeneron, PaxVax, Pfizer, Merck, Novavax, Sanofi Pasteur, and Micron Technology.

SOURCE: Sederdahl BK et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2498.

falling short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% complete vaccination, according to Bethany K. Sederdahl, MPH, and her associates at Emory University, Atlanta.

In an analysis published in Pediatrics of data from 14,571 children included in the 2014 National Immunization Survey, 71% of children received full vaccination for rotavirus, 15% received partial vaccination, and 14% received no vaccination. Children whose mothers were not college graduates, lived in households with at least four children, or were uninsured at any point had an increased likelihood of being unvaccinated; African American children also faced an increased risk of being unvaccinated.

Among the unvaccinated, 72% had at least one missed opportunity according to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices schedule, and 83% had at least one missed opportunity according to the World Health Organization schedule. For the partially vaccinated, 54% at least one missed opportunity according to the ACIP schedule, and 96% had at least one missed opportunity according to the WHO schedule. While poorer socioeconomic conditions were associated with the risk of being unvaccinated, children who were partially vaccinated and who missed vaccination opportunities according to the ACIP-recommended schedule were more likely to have mothers with a college degree or an income of more than $75,000.

According to the investigators, if all missed opportunities for vaccination according to the ACIP schedule were addressed, coverage would improve from 71% to 81%; if all opportunities according to the WHO schedule were addressed, coverage would increase to 94%.

“Low rotavirus vaccine uptake may be attributable to both socioeconomic barriers and possibly vaccine hesitancy. Understanding the barriers to rotavirus vaccine uptake and developing effective public health measures to promote vaccine use will be essential to reducing rotavirus morbidity in the United States,” Ms. Sederdahl and her associates wrote.

The study received no external funding. One coauthor reported receiving personal fees from AbbVie, funds to conduct clinical research from Merck, and that his institution receives funds to conduct clinical research from MedImmune, Regeneron, PaxVax, Pfizer, Merck, Novavax, Sanofi Pasteur, and Micron Technology.

SOURCE: Sederdahl BK et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2498.

FROM PEDIATRICS

U.S. measles cases nearing postelimination-era high

The United States has topped 600 cases of measles for 2019 and is likely to pass the postelimination high set in 2014 “in the coming weeks,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 71 new measles cases reported during the week ending April 18 bring the total for the year to 626 in 22 states, the CDC reported April 22. Two states, Iowa and Tennessee, reported their first cases last week.

Outbreaks continue in five states: one in California (Butte County), one in Michigan (Oakland County/Wayne County/Detroit), one in New Jersey (Ocean County/Monmouth County), two in New York (New York City and Rockland County), and one in Washington (Clark County/King County), the CDC said.

The most active outbreak since mid-February has been the one occurring in New York City, mainly in Brooklyn, and last week was no exception as 50 of the 71 new U.S. cases were reported in the borough.

On April 18, a judge in Brooklyn “ruled against a group of parents who challenged New York City’s recently imposed mandatory measles vaccination order,” Reuters reported. That same day, the city issued a summons, subject to a fine of $1,000 each, to three people in Brooklyn who were still unvaccinated, according to NYC Health, which also said that four additional schools would be closed for not complying with an order to exclude unvaccinated students.

On April 15, the Iowa Department of Public Health confirmed the state’s first case of measles since 2011. The individual from Northeastern Iowa had not been vaccinated and had recently returned from Israel. The state’s second case of the year, a household contact of the first individual, was confirmed on April 18.

Also on April 18, the Tennessee Department of Health confirmed its first case of the year in a resident of the eastern part of the state. Meanwhile, media are reporting that state health officials in Mississippi are investigating possible exposures on April 9 and 10 in the Hattiesburg area by the infected Tennessee man.

Outside the United States, “many countries are in the midst of sizeable measles outbreaks, with all regions of the world experiencing sustained rises in cases,” the World Health Organization said. Current outbreaks include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Myanmar, Philippines, Sudan, Thailand, and Ukraine.

Preliminary data for the first 3 months of 2019 show that cases worldwide were up by 300% over the first 3 months of 2018: 112,163 cases vs. 28,124. The actual numbers for 2019 are expected to be considerably higher than those reported so far, and WHO estimates that, globally, less than 1 in 10 cases are actually reported.

The United States has topped 600 cases of measles for 2019 and is likely to pass the postelimination high set in 2014 “in the coming weeks,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 71 new measles cases reported during the week ending April 18 bring the total for the year to 626 in 22 states, the CDC reported April 22. Two states, Iowa and Tennessee, reported their first cases last week.

Outbreaks continue in five states: one in California (Butte County), one in Michigan (Oakland County/Wayne County/Detroit), one in New Jersey (Ocean County/Monmouth County), two in New York (New York City and Rockland County), and one in Washington (Clark County/King County), the CDC said.

The most active outbreak since mid-February has been the one occurring in New York City, mainly in Brooklyn, and last week was no exception as 50 of the 71 new U.S. cases were reported in the borough.

On April 18, a judge in Brooklyn “ruled against a group of parents who challenged New York City’s recently imposed mandatory measles vaccination order,” Reuters reported. That same day, the city issued a summons, subject to a fine of $1,000 each, to three people in Brooklyn who were still unvaccinated, according to NYC Health, which also said that four additional schools would be closed for not complying with an order to exclude unvaccinated students.

On April 15, the Iowa Department of Public Health confirmed the state’s first case of measles since 2011. The individual from Northeastern Iowa had not been vaccinated and had recently returned from Israel. The state’s second case of the year, a household contact of the first individual, was confirmed on April 18.

Also on April 18, the Tennessee Department of Health confirmed its first case of the year in a resident of the eastern part of the state. Meanwhile, media are reporting that state health officials in Mississippi are investigating possible exposures on April 9 and 10 in the Hattiesburg area by the infected Tennessee man.

Outside the United States, “many countries are in the midst of sizeable measles outbreaks, with all regions of the world experiencing sustained rises in cases,” the World Health Organization said. Current outbreaks include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Myanmar, Philippines, Sudan, Thailand, and Ukraine.

Preliminary data for the first 3 months of 2019 show that cases worldwide were up by 300% over the first 3 months of 2018: 112,163 cases vs. 28,124. The actual numbers for 2019 are expected to be considerably higher than those reported so far, and WHO estimates that, globally, less than 1 in 10 cases are actually reported.

The United States has topped 600 cases of measles for 2019 and is likely to pass the postelimination high set in 2014 “in the coming weeks,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 71 new measles cases reported during the week ending April 18 bring the total for the year to 626 in 22 states, the CDC reported April 22. Two states, Iowa and Tennessee, reported their first cases last week.

Outbreaks continue in five states: one in California (Butte County), one in Michigan (Oakland County/Wayne County/Detroit), one in New Jersey (Ocean County/Monmouth County), two in New York (New York City and Rockland County), and one in Washington (Clark County/King County), the CDC said.

The most active outbreak since mid-February has been the one occurring in New York City, mainly in Brooklyn, and last week was no exception as 50 of the 71 new U.S. cases were reported in the borough.

On April 18, a judge in Brooklyn “ruled against a group of parents who challenged New York City’s recently imposed mandatory measles vaccination order,” Reuters reported. That same day, the city issued a summons, subject to a fine of $1,000 each, to three people in Brooklyn who were still unvaccinated, according to NYC Health, which also said that four additional schools would be closed for not complying with an order to exclude unvaccinated students.

On April 15, the Iowa Department of Public Health confirmed the state’s first case of measles since 2011. The individual from Northeastern Iowa had not been vaccinated and had recently returned from Israel. The state’s second case of the year, a household contact of the first individual, was confirmed on April 18.

Also on April 18, the Tennessee Department of Health confirmed its first case of the year in a resident of the eastern part of the state. Meanwhile, media are reporting that state health officials in Mississippi are investigating possible exposures on April 9 and 10 in the Hattiesburg area by the infected Tennessee man.

Outside the United States, “many countries are in the midst of sizeable measles outbreaks, with all regions of the world experiencing sustained rises in cases,” the World Health Organization said. Current outbreaks include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Myanmar, Philippines, Sudan, Thailand, and Ukraine.

Preliminary data for the first 3 months of 2019 show that cases worldwide were up by 300% over the first 3 months of 2018: 112,163 cases vs. 28,124. The actual numbers for 2019 are expected to be considerably higher than those reported so far, and WHO estimates that, globally, less than 1 in 10 cases are actually reported.

Postvaccination febrile seizures are no more severe than other febrile seizures

according to a study in Pediatrics.

Lucy Deng, MBBS, of the University of Sydney and her colleagues investigated 1,022 index febrile seizures in children aged 6 years or less, of which 6% (n = 67) were VP-FSs and 94% (n = 955) were NVP-FSs. Both univariate and multivariate analyses showed no increased risk of severe seizure associated with VP-FSs, compared with NVP-FS. Most of the febrile seizures of either type were brief (15 minutes or less) and had a length of stay of 1 day or less; there also were no differences in 24-hour recurrence. The most common symptom was respiratory, and the rates were similar in each group (62.7% with VP-FS vs. 62.8% with NVP-FS). In keeping with a known 100% increased risk associated with measles vaccination, 84% of VP-FSs were associated with measles-containing vaccines. The majority of the remaining VP-FSs occurred after combination vaccines.

One limitation is that, because these cases were documented in sentinel tertiary pediatric hospitals, the case ascertainment may not be representative. Also, the small proportion of VP-FSs and limited cohort size means the study may not have been powered to detect true differences in prolonged seizures between the groups, Dr. Deng and her colleagues wrote.

“This study confirms that VP-FSs are clinically not any different from NVP-FSs and should be managed the same way,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures, although Dr. Deng is supported by the University of Sydney Training Program scholarship, and two other study authors are supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowships. The study was funded by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

SOURCE: Deng L et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2120.

according to a study in Pediatrics.

Lucy Deng, MBBS, of the University of Sydney and her colleagues investigated 1,022 index febrile seizures in children aged 6 years or less, of which 6% (n = 67) were VP-FSs and 94% (n = 955) were NVP-FSs. Both univariate and multivariate analyses showed no increased risk of severe seizure associated with VP-FSs, compared with NVP-FS. Most of the febrile seizures of either type were brief (15 minutes or less) and had a length of stay of 1 day or less; there also were no differences in 24-hour recurrence. The most common symptom was respiratory, and the rates were similar in each group (62.7% with VP-FS vs. 62.8% with NVP-FS). In keeping with a known 100% increased risk associated with measles vaccination, 84% of VP-FSs were associated with measles-containing vaccines. The majority of the remaining VP-FSs occurred after combination vaccines.

One limitation is that, because these cases were documented in sentinel tertiary pediatric hospitals, the case ascertainment may not be representative. Also, the small proportion of VP-FSs and limited cohort size means the study may not have been powered to detect true differences in prolonged seizures between the groups, Dr. Deng and her colleagues wrote.

“This study confirms that VP-FSs are clinically not any different from NVP-FSs and should be managed the same way,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures, although Dr. Deng is supported by the University of Sydney Training Program scholarship, and two other study authors are supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowships. The study was funded by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

SOURCE: Deng L et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2120.

according to a study in Pediatrics.

Lucy Deng, MBBS, of the University of Sydney and her colleagues investigated 1,022 index febrile seizures in children aged 6 years or less, of which 6% (n = 67) were VP-FSs and 94% (n = 955) were NVP-FSs. Both univariate and multivariate analyses showed no increased risk of severe seizure associated with VP-FSs, compared with NVP-FS. Most of the febrile seizures of either type were brief (15 minutes or less) and had a length of stay of 1 day or less; there also were no differences in 24-hour recurrence. The most common symptom was respiratory, and the rates were similar in each group (62.7% with VP-FS vs. 62.8% with NVP-FS). In keeping with a known 100% increased risk associated with measles vaccination, 84% of VP-FSs were associated with measles-containing vaccines. The majority of the remaining VP-FSs occurred after combination vaccines.

One limitation is that, because these cases were documented in sentinel tertiary pediatric hospitals, the case ascertainment may not be representative. Also, the small proportion of VP-FSs and limited cohort size means the study may not have been powered to detect true differences in prolonged seizures between the groups, Dr. Deng and her colleagues wrote.

“This study confirms that VP-FSs are clinically not any different from NVP-FSs and should be managed the same way,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures, although Dr. Deng is supported by the University of Sydney Training Program scholarship, and two other study authors are supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowships. The study was funded by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

SOURCE: Deng L et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 19. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2120.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Decline in CIN2+ in younger women after HPV vaccine introduced

The introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States in 2006 was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and above (CIN2+) in younger women.

The overall rate of CIN2+ declined from an estimated 216,000 cases in 2008 – 55% of which were in women aged 18-29 years – to 196,000 cases in 2016, of which 36% were in women aged 18-29 years, according to analysis of data from the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Impact Monitoring Program (MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

In 2008, the highest rates of CIN2+ were seen in women aged 20-24 years and decreased with age, but in 2016, the highest rates were in women aged 25-29 years. The rates of CIN2+ declined significantly in women aged 18-19 years from 2008-2016, but increased in women aged 40-64 years.

In 2008 and 2016, around three-quarters of all CIN2+ cases were attributable to HPV types that are targeted by the HPV vaccine. However the rates of vaccine-preventable CIN2+ declined among women aged 18-24 years, from 52% in 2008 to 30% in 2016.

“Both the estimated number and rates of U.S. CIN2+ cases in this report must be interpreted in the context of cervical cancer prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening,” wrote Nancy M. McClung, PhD, of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Notably, the screening interval for cervical cancer was increased from yearly in 2008 to once in 3 years with cytology alone or once in 5 years with cytology plus HPV testing for women aged 30 or above in 2016.

“Older age at screening initiation, longer screening intervals, and more conservative management in young women might be expected to reduce the number of CIN2+ cases detected in younger age groups in whom lesions are most likely to regress and shift detection of some CIN2+ to older age groups, resulting in a transient increase in rates,” Dr. McClung and colleagues wrote.

However they noted that the decrease in HPV 16/18–attributable CIN2+ rates among younger age groups was likely a reflection of the impact of the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine immunization program.

One author declared personal fees from Merck during the course of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: McClung N et al. MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

The introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States in 2006 was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and above (CIN2+) in younger women.

The overall rate of CIN2+ declined from an estimated 216,000 cases in 2008 – 55% of which were in women aged 18-29 years – to 196,000 cases in 2016, of which 36% were in women aged 18-29 years, according to analysis of data from the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Impact Monitoring Program (MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

In 2008, the highest rates of CIN2+ were seen in women aged 20-24 years and decreased with age, but in 2016, the highest rates were in women aged 25-29 years. The rates of CIN2+ declined significantly in women aged 18-19 years from 2008-2016, but increased in women aged 40-64 years.

In 2008 and 2016, around three-quarters of all CIN2+ cases were attributable to HPV types that are targeted by the HPV vaccine. However the rates of vaccine-preventable CIN2+ declined among women aged 18-24 years, from 52% in 2008 to 30% in 2016.

“Both the estimated number and rates of U.S. CIN2+ cases in this report must be interpreted in the context of cervical cancer prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening,” wrote Nancy M. McClung, PhD, of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Notably, the screening interval for cervical cancer was increased from yearly in 2008 to once in 3 years with cytology alone or once in 5 years with cytology plus HPV testing for women aged 30 or above in 2016.

“Older age at screening initiation, longer screening intervals, and more conservative management in young women might be expected to reduce the number of CIN2+ cases detected in younger age groups in whom lesions are most likely to regress and shift detection of some CIN2+ to older age groups, resulting in a transient increase in rates,” Dr. McClung and colleagues wrote.

However they noted that the decrease in HPV 16/18–attributable CIN2+ rates among younger age groups was likely a reflection of the impact of the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine immunization program.

One author declared personal fees from Merck during the course of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: McClung N et al. MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

The introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination in the United States in 2006 was associated with a significant decrease in the rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and above (CIN2+) in younger women.

The overall rate of CIN2+ declined from an estimated 216,000 cases in 2008 – 55% of which were in women aged 18-29 years – to 196,000 cases in 2016, of which 36% were in women aged 18-29 years, according to analysis of data from the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Impact Monitoring Program (MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

In 2008, the highest rates of CIN2+ were seen in women aged 20-24 years and decreased with age, but in 2016, the highest rates were in women aged 25-29 years. The rates of CIN2+ declined significantly in women aged 18-19 years from 2008-2016, but increased in women aged 40-64 years.

In 2008 and 2016, around three-quarters of all CIN2+ cases were attributable to HPV types that are targeted by the HPV vaccine. However the rates of vaccine-preventable CIN2+ declined among women aged 18-24 years, from 52% in 2008 to 30% in 2016.

“Both the estimated number and rates of U.S. CIN2+ cases in this report must be interpreted in the context of cervical cancer prevention strategies, including HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening,” wrote Nancy M. McClung, PhD, of the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and coauthors.

Notably, the screening interval for cervical cancer was increased from yearly in 2008 to once in 3 years with cytology alone or once in 5 years with cytology plus HPV testing for women aged 30 or above in 2016.

“Older age at screening initiation, longer screening intervals, and more conservative management in young women might be expected to reduce the number of CIN2+ cases detected in younger age groups in whom lesions are most likely to regress and shift detection of some CIN2+ to older age groups, resulting in a transient increase in rates,” Dr. McClung and colleagues wrote.

However they noted that the decrease in HPV 16/18–attributable CIN2+ rates among younger age groups was likely a reflection of the impact of the introduction of the quadrivalent vaccine immunization program.

One author declared personal fees from Merck during the course of the study. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: McClung N et al. MMWR. 2019 Apr 19;68:337-43.

FROM MMWR

Busiest week yet brings 2019 measles total to 555 cases

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 90 measles cases reported during the week ending April 11 mark the third consecutive weekly high for 2019, topping the 78 recorded during the week of April 4 and the 73 reported during the week of March 28. Meanwhile, this year’s total trails only the 667 cases reported in 2014 for the highest in the postelimination era, the CDC said April 15.

New York reported 26 new cases in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood last week, which puts the borough at 227 for the year, with another two occurring in the Flushing section of Queens. A public health emergency declared on April 9 covers several zip codes in Williamsburg and requires unvaccinated individuals who may have been exposed to measles to receive “the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in order to protect others in the community and help curtail the ongoing outbreak,” the city’s health department said in a written statement.

Maryland became the 20th state to report a measles case this year, and the state’s department of health said it was notifying those in the vicinity of a medical office building in Pikesville about possible exposure on April 2.

The recent outbreak in Michigan’s Oakland County did not result in any new patients over the last week and remains at 38 cases, with the state reporting one additional case in Wayne County. More recent reports of a case in Washtenaw County and another in Oakland County were reversed after additional testing, the state health department reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 90 measles cases reported during the week ending April 11 mark the third consecutive weekly high for 2019, topping the 78 recorded during the week of April 4 and the 73 reported during the week of March 28. Meanwhile, this year’s total trails only the 667 cases reported in 2014 for the highest in the postelimination era, the CDC said April 15.

New York reported 26 new cases in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood last week, which puts the borough at 227 for the year, with another two occurring in the Flushing section of Queens. A public health emergency declared on April 9 covers several zip codes in Williamsburg and requires unvaccinated individuals who may have been exposed to measles to receive “the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in order to protect others in the community and help curtail the ongoing outbreak,” the city’s health department said in a written statement.

Maryland became the 20th state to report a measles case this year, and the state’s department of health said it was notifying those in the vicinity of a medical office building in Pikesville about possible exposure on April 2.

The recent outbreak in Michigan’s Oakland County did not result in any new patients over the last week and remains at 38 cases, with the state reporting one additional case in Wayne County. More recent reports of a case in Washtenaw County and another in Oakland County were reversed after additional testing, the state health department reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 90 measles cases reported during the week ending April 11 mark the third consecutive weekly high for 2019, topping the 78 recorded during the week of April 4 and the 73 reported during the week of March 28. Meanwhile, this year’s total trails only the 667 cases reported in 2014 for the highest in the postelimination era, the CDC said April 15.

New York reported 26 new cases in Brooklyn’s Williamsburg neighborhood last week, which puts the borough at 227 for the year, with another two occurring in the Flushing section of Queens. A public health emergency declared on April 9 covers several zip codes in Williamsburg and requires unvaccinated individuals who may have been exposed to measles to receive “the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in order to protect others in the community and help curtail the ongoing outbreak,” the city’s health department said in a written statement.

Maryland became the 20th state to report a measles case this year, and the state’s department of health said it was notifying those in the vicinity of a medical office building in Pikesville about possible exposure on April 2.

The recent outbreak in Michigan’s Oakland County did not result in any new patients over the last week and remains at 38 cases, with the state reporting one additional case in Wayne County. More recent reports of a case in Washtenaw County and another in Oakland County were reversed after additional testing, the state health department reported.

A chance to unite

Is America coming apart at the seams? According to the press, there are more things that divide us than bind us together. It’s red state versus blue state, it’s the privileged versus the disadvantaged, people of color versus the white majority. Could the great melting pot have cooled and its contents settled out into a dozen stratified layers?

Despite the image of a divided America that we see portrayed in the newspapers and on television, I continue to believe that there is more that we share in common than separate us, but it’s a struggle. The media operate on the assumption that conflict draws more readers than good news about cooperation and compromise. The situation is compounded by the apparent absence of a leader from either party who wants to unite us.

However, when one scratches the surface, there is surprising amount of agreement among Americans. For example, according to John Gramlich (“7 facts about guns in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Dec. 27, 2018), 89% of both Republicans and Democrats feel that people with mental illness should not be allowed to purchase a gun. And 79% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats favor background checks at gun shows and for private sales for purchase of a gun. As of 2018, 58% of Americans feel that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and only 37% feel it should be illegal in all or most cases. (“Public Opinion on Abortion,” Pew Research Center, Oct. 15, 2018).

At the core of many of our struggles to unite is a question that has bedeviled democracies for millennia: How does one balance a citizen’s freedom of choice with the health and safety of the society in which that person lives? While resolutions on gun control and abortion seem unlikely in the foreseeable future, the current outbreaks of measles offer America a rare opportunity to unite on an issue that pits personal freedom against societal safety.

According to Virginia Villa (“5 facts about vaccines in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Mar. 19, 2019), 82% of adults in the United States believe that the MMR vaccine should be required for public school attendance, while only 17% believe that parents should be allowed to leave their child unvaccinated even if their decision creates a health risk for other children and adults.

Why should we expect the government to respond to protect the population from the risk posed by the unvaccinated minority when it has done very little to further gun control? Obviously a key difference is that the antivaccination minority lacks the financial resources and political muscle of a large organization such as the National Rifle Association. While we must never underestimate the power of social media, the publicity surfacing from the mainstream media as the measles outbreaks in the United States have continued has prompted several states to rethink their policies regarding vaccination requirements and school attendance. Here in Maine, there has been strong support among the legislature for eliminating exemptions for philosophic or religious exemptions.

It is probably unrealistic to expect the federal government to act on the health threat caused by the antivaccine movement. However, it is encouraging that, at least at the local level, there is hope for closing one of the wounds that divide us. As providers who care for children, we should seize this opportunity created by the measles outbreaks to promote legislation and policies that strike a sensible balance between the right of the individual and the safety of the society at large.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Is America coming apart at the seams? According to the press, there are more things that divide us than bind us together. It’s red state versus blue state, it’s the privileged versus the disadvantaged, people of color versus the white majority. Could the great melting pot have cooled and its contents settled out into a dozen stratified layers?

Despite the image of a divided America that we see portrayed in the newspapers and on television, I continue to believe that there is more that we share in common than separate us, but it’s a struggle. The media operate on the assumption that conflict draws more readers than good news about cooperation and compromise. The situation is compounded by the apparent absence of a leader from either party who wants to unite us.

However, when one scratches the surface, there is surprising amount of agreement among Americans. For example, according to John Gramlich (“7 facts about guns in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Dec. 27, 2018), 89% of both Republicans and Democrats feel that people with mental illness should not be allowed to purchase a gun. And 79% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats favor background checks at gun shows and for private sales for purchase of a gun. As of 2018, 58% of Americans feel that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and only 37% feel it should be illegal in all or most cases. (“Public Opinion on Abortion,” Pew Research Center, Oct. 15, 2018).

At the core of many of our struggles to unite is a question that has bedeviled democracies for millennia: How does one balance a citizen’s freedom of choice with the health and safety of the society in which that person lives? While resolutions on gun control and abortion seem unlikely in the foreseeable future, the current outbreaks of measles offer America a rare opportunity to unite on an issue that pits personal freedom against societal safety.

According to Virginia Villa (“5 facts about vaccines in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, Mar. 19, 2019), 82% of adults in the United States believe that the MMR vaccine should be required for public school attendance, while only 17% believe that parents should be allowed to leave their child unvaccinated even if their decision creates a health risk for other children and adults.

Why should we expect the government to respond to protect the population from the risk posed by the unvaccinated minority when it has done very little to further gun control? Obviously a key difference is that the antivaccination minority lacks the financial resources and political muscle of a large organization such as the National Rifle Association. While we must never underestimate the power of social media, the publicity surfacing from the mainstream media as the measles outbreaks in the United States have continued has prompted several states to rethink their policies regarding vaccination requirements and school attendance. Here in Maine, there has been strong support among the legislature for eliminating exemptions for philosophic or religious exemptions.

It is probably unrealistic to expect the federal government to act on the health threat caused by the antivaccine movement. However, it is encouraging that, at least at the local level, there is hope for closing one of the wounds that divide us. As providers who care for children, we should seize this opportunity created by the measles outbreaks to promote legislation and policies that strike a sensible balance between the right of the individual and the safety of the society at large.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Is America coming apart at the seams? According to the press, there are more things that divide us than bind us together. It’s red state versus blue state, it’s the privileged versus the disadvantaged, people of color versus the white majority. Could the great melting pot have cooled and its contents settled out into a dozen stratified layers?