User login

Continue your VAM conversations on SVSConnect

Conversations surrounding the 2019 Vascular Annual Meeting have begun on SVSConnect. Share what you learned at your favorite session, start a discussion about the Branding Initiative or reminisce about the ‘Vascular Spectacular’ gala. Keep the conversations going and connect with other attendees you met – or didn’t meet – at the conference. Simply log in with your SVS credentials to get started. Reach out to [email protected] or call 312-334-2300 with questions.

Conversations surrounding the 2019 Vascular Annual Meeting have begun on SVSConnect. Share what you learned at your favorite session, start a discussion about the Branding Initiative or reminisce about the ‘Vascular Spectacular’ gala. Keep the conversations going and connect with other attendees you met – or didn’t meet – at the conference. Simply log in with your SVS credentials to get started. Reach out to [email protected] or call 312-334-2300 with questions.

Conversations surrounding the 2019 Vascular Annual Meeting have begun on SVSConnect. Share what you learned at your favorite session, start a discussion about the Branding Initiative or reminisce about the ‘Vascular Spectacular’ gala. Keep the conversations going and connect with other attendees you met – or didn’t meet – at the conference. Simply log in with your SVS credentials to get started. Reach out to [email protected] or call 312-334-2300 with questions.

Provide feedback on Branding Initiative

The SVS Branding Initiative concepts were introduced at the Vascular Annual Meeting last week. We asked attendees to provide their feedback either at the SVS booth or through the event app. Input from members is vital in moving this forward, and we appreciate all who have shared their thoughts on the topic. If you did not have the opportunity to complete the survey, there is still time! All SVS members are encouraged to provide feedback until the survey closes on June 26. Take the survey here.

The SVS Branding Initiative concepts were introduced at the Vascular Annual Meeting last week. We asked attendees to provide their feedback either at the SVS booth or through the event app. Input from members is vital in moving this forward, and we appreciate all who have shared their thoughts on the topic. If you did not have the opportunity to complete the survey, there is still time! All SVS members are encouraged to provide feedback until the survey closes on June 26. Take the survey here.

The SVS Branding Initiative concepts were introduced at the Vascular Annual Meeting last week. We asked attendees to provide their feedback either at the SVS booth or through the event app. Input from members is vital in moving this forward, and we appreciate all who have shared their thoughts on the topic. If you did not have the opportunity to complete the survey, there is still time! All SVS members are encouraged to provide feedback until the survey closes on June 26. Take the survey here.

VAM on Demand Coming Soon

If you missed the Vascular Annual Meeting, would like to review some sessions or view the ones you missed, purchase VAM on Demand. The online library will hold audio and slide presentations of most sessions from the meeting. It will become available in four-six weeks, at which time a notification will be distributed. Attendees will pay $199 and non-attendees will pay $499. Contact the SVS Education Department for more information at [email protected].

If you missed the Vascular Annual Meeting, would like to review some sessions or view the ones you missed, purchase VAM on Demand. The online library will hold audio and slide presentations of most sessions from the meeting. It will become available in four-six weeks, at which time a notification will be distributed. Attendees will pay $199 and non-attendees will pay $499. Contact the SVS Education Department for more information at [email protected].

If you missed the Vascular Annual Meeting, would like to review some sessions or view the ones you missed, purchase VAM on Demand. The online library will hold audio and slide presentations of most sessions from the meeting. It will become available in four-six weeks, at which time a notification will be distributed. Attendees will pay $199 and non-attendees will pay $499. Contact the SVS Education Department for more information at [email protected].

FDA panel: Continue using paclitaxel-eluting PAD devices, with caveats

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – There was sufficient evidence of a late mortality signal seen at 2-5 years post procedurally for paclitaxel-eluting stents and coated balloons to warrant a label change for the devices, the Food and Drug Administration’s Circulatory System Devices Panel unanimously agreed after 2 days of deliberation.

That signal was brought to light in a meta-analysis published last December by Konstantinos Katsanos, MD, of Patras University Hospital, Rion, Greece, and colleagues (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e011245). Although there were concerns about the quality of the industry data used in the study, the caliber of the analysis itself and the subsequent data presented by the FDA to the panel were deemed sufficient to recommend a warning of concern to patients and providers.

Much of the new data from industry and large database registries presented to the panel, which was chaired by Richard A. Lange, MD, indicated a lessening to no evidence of the mortality effect. But this evidence was deemed insufficient to counter the evidence of the randomized controlled trials individually and collectively as presented in the Katsanos meta-analysis and subsequent information presented by the FDA that examined various parameters in a variety of sensitivity analyses that confirmed the late mortality signal. There was also concern that the industry and the registry analyses presented were not peer reviewed.

However, the panel also determined that it would be inappropriate to pull the devices from the market and from general use for several reasons.

One key reason was that, according to the panel, there was no mechanistic cause apparent for the late mortality. In addition, no convincing dose-response data could be teased from the preclinical and clinical trials studied because of their variability of devices, application methods, and lack of appropriate tissue analysis across studies.

Finally, the industry data used to create the meta-analysis were considered to be fundamentally flawed: in blinding, in the relatively small numbers of patients, and in the large percentage of patients lost to follow-up. The latter could have dramatically influenced the perceived results, especially as the studies were not powered or designed to follow mortality over such a period of time, according to the panel.

These limitations to the signal were especially important to the panel because of the obvious benefits with regard to quality of life provided to patients from these devices, which were attested to during the 2-day meeting by numerous presenters from industry, medical organizations – including societies and nonprofits – and providers.

In responding to FDA requests on a variety of concerns, the panel reiterated that there was a credible mortality signal, but that they could not be confident about the magnitude and whether it was caused by the paclitaxel treatment or some factor in the design or conduct of the studies. In addition, the panel members felt that they could neither confirm nor eliminate a class effect, given the fact that the information was based on a meta-analysis and thus none of the included devices could safely be removed from consideration.

They suggested that further safety information should be obtained, potentially by assessing and perhaps altering data collection in 29 ongoing studies over the next 5 years or so in more than 10,000 patients.

In addition, several of the panel members felt that additional animal studies might be performed including the use of older rat models; and using animal models that mimicked the kind of comorbidities present in the treated population, such as diabetes and atherosclerosis. They suggested cross-company industry cooperation with the FDA on these models, including looking at drug interactions and mimicking the dose application of stents/balloons.

Both the FDA representative and the panel were especially concerned with the benefit/risk profile.

The recommendation to still market the devices with a label warning was warranted, according to many members of the panel. They pointed to the clear benefits in quality of life and the lowered need for revascularization despite the evidence of the mortality signal, which, while statistically significant, could not be pinned town with regard to mechanisms or specific causes of death.

Overall, there was a concern that there should be a dialogue between patients and their doctors to discuss clear short-term benefits with unknown long-term risk, and that the label should support this by clearly mentioning the mortality signal that was found, although there was no attempt to develop exact wording.

Panel member Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, suggested with regard to labeling that a statement “that ‘there may be’ – not ‘there is’ – a late mortality signal, should be included.”

Panel member John C. Somberg, MD, program director of clinical research and bioinformatics at Rush University in Lake Bluff, Ill., stated: “The label should say something like, ‘when looking at a meta-analysis that combined all studies with stents and balloons that carried paclitaxel, there may be a late mortality, which must be balanced against an early and sustained benefit in terms of pain on walking and potential loss of circulation to your extremity.’ ”

Other panel members thought that the meta-analysis should not be privileged and that somehow the totality of the evidence should somehow be distilled down into the label, including the evidence against the signal.

“We’re meeting because of a signal, of a concern – an honest, well-meaning concern – of increased mortality. And my opinion is that the patients need to be informed of it,” said Dr. Lange, president, Texas Tech University, El Paso.

Some members of the panel felt that it may not be justifiable to use these devices in patients with low intrinsic risk and low recurrence risk, and the whole spectrum of patients may need to be considered in further studies to figure out the subgroups that have more benefits and more risks, and also to consider how to mitigate risks in patients who receive the device, whether through medical therapy or lifestyle modification.

In particular, Frank W. LoGerfo, MD, the William V. McDermott Distinguished Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, stated: “Interventions for claudication should be extremely rare. It rarely progresses, and the pain should be worked through by exercise with low risk of limb loss.” He added that intervention with these devices “takes away options. Trading life for something that is not limb-threatening is something we should not be considering.”

There was no firm consensus on whether new randomized trials should be done, although they were of course the ideal solution. Kevin E. Kip, PhD, Distinguished USF Health Professor at the University of South Florida, Tampa, and others argued that, whether new trials were necessary or not, to deal with the safety question in a timely fashion, existing trials have to capture as much of the missing data as possible, and carry out follow-up out further.

FDA representative Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, indicated that those things might not be easily be accomplished due to regulatory constraints and the financial costs, and that to do so there would be need for community effort among stakeholders, including collaborative efforts with existing prospective registries such as that run by the Vascular Quality Initiative.

One overall conclusion by both the FDA and panel members was that the quality of these and other such studies going forward must improve, by standardizing definitions and data forms to make studies more uniform across the industry. They reemphasized the need to work with the registries to get common data included, and to incorporate of insurance provider and Social Security death data as much as possible to help alleviate the lost follow-up problem.

SOURCE: Webcasts of the complete 2 days of the FDA panel meeting are available online.

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – There was sufficient evidence of a late mortality signal seen at 2-5 years post procedurally for paclitaxel-eluting stents and coated balloons to warrant a label change for the devices, the Food and Drug Administration’s Circulatory System Devices Panel unanimously agreed after 2 days of deliberation.

That signal was brought to light in a meta-analysis published last December by Konstantinos Katsanos, MD, of Patras University Hospital, Rion, Greece, and colleagues (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e011245). Although there were concerns about the quality of the industry data used in the study, the caliber of the analysis itself and the subsequent data presented by the FDA to the panel were deemed sufficient to recommend a warning of concern to patients and providers.

Much of the new data from industry and large database registries presented to the panel, which was chaired by Richard A. Lange, MD, indicated a lessening to no evidence of the mortality effect. But this evidence was deemed insufficient to counter the evidence of the randomized controlled trials individually and collectively as presented in the Katsanos meta-analysis and subsequent information presented by the FDA that examined various parameters in a variety of sensitivity analyses that confirmed the late mortality signal. There was also concern that the industry and the registry analyses presented were not peer reviewed.

However, the panel also determined that it would be inappropriate to pull the devices from the market and from general use for several reasons.

One key reason was that, according to the panel, there was no mechanistic cause apparent for the late mortality. In addition, no convincing dose-response data could be teased from the preclinical and clinical trials studied because of their variability of devices, application methods, and lack of appropriate tissue analysis across studies.

Finally, the industry data used to create the meta-analysis were considered to be fundamentally flawed: in blinding, in the relatively small numbers of patients, and in the large percentage of patients lost to follow-up. The latter could have dramatically influenced the perceived results, especially as the studies were not powered or designed to follow mortality over such a period of time, according to the panel.

These limitations to the signal were especially important to the panel because of the obvious benefits with regard to quality of life provided to patients from these devices, which were attested to during the 2-day meeting by numerous presenters from industry, medical organizations – including societies and nonprofits – and providers.

In responding to FDA requests on a variety of concerns, the panel reiterated that there was a credible mortality signal, but that they could not be confident about the magnitude and whether it was caused by the paclitaxel treatment or some factor in the design or conduct of the studies. In addition, the panel members felt that they could neither confirm nor eliminate a class effect, given the fact that the information was based on a meta-analysis and thus none of the included devices could safely be removed from consideration.

They suggested that further safety information should be obtained, potentially by assessing and perhaps altering data collection in 29 ongoing studies over the next 5 years or so in more than 10,000 patients.

In addition, several of the panel members felt that additional animal studies might be performed including the use of older rat models; and using animal models that mimicked the kind of comorbidities present in the treated population, such as diabetes and atherosclerosis. They suggested cross-company industry cooperation with the FDA on these models, including looking at drug interactions and mimicking the dose application of stents/balloons.

Both the FDA representative and the panel were especially concerned with the benefit/risk profile.

The recommendation to still market the devices with a label warning was warranted, according to many members of the panel. They pointed to the clear benefits in quality of life and the lowered need for revascularization despite the evidence of the mortality signal, which, while statistically significant, could not be pinned town with regard to mechanisms or specific causes of death.

Overall, there was a concern that there should be a dialogue between patients and their doctors to discuss clear short-term benefits with unknown long-term risk, and that the label should support this by clearly mentioning the mortality signal that was found, although there was no attempt to develop exact wording.

Panel member Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, suggested with regard to labeling that a statement “that ‘there may be’ – not ‘there is’ – a late mortality signal, should be included.”

Panel member John C. Somberg, MD, program director of clinical research and bioinformatics at Rush University in Lake Bluff, Ill., stated: “The label should say something like, ‘when looking at a meta-analysis that combined all studies with stents and balloons that carried paclitaxel, there may be a late mortality, which must be balanced against an early and sustained benefit in terms of pain on walking and potential loss of circulation to your extremity.’ ”

Other panel members thought that the meta-analysis should not be privileged and that somehow the totality of the evidence should somehow be distilled down into the label, including the evidence against the signal.

“We’re meeting because of a signal, of a concern – an honest, well-meaning concern – of increased mortality. And my opinion is that the patients need to be informed of it,” said Dr. Lange, president, Texas Tech University, El Paso.

Some members of the panel felt that it may not be justifiable to use these devices in patients with low intrinsic risk and low recurrence risk, and the whole spectrum of patients may need to be considered in further studies to figure out the subgroups that have more benefits and more risks, and also to consider how to mitigate risks in patients who receive the device, whether through medical therapy or lifestyle modification.

In particular, Frank W. LoGerfo, MD, the William V. McDermott Distinguished Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, stated: “Interventions for claudication should be extremely rare. It rarely progresses, and the pain should be worked through by exercise with low risk of limb loss.” He added that intervention with these devices “takes away options. Trading life for something that is not limb-threatening is something we should not be considering.”

There was no firm consensus on whether new randomized trials should be done, although they were of course the ideal solution. Kevin E. Kip, PhD, Distinguished USF Health Professor at the University of South Florida, Tampa, and others argued that, whether new trials were necessary or not, to deal with the safety question in a timely fashion, existing trials have to capture as much of the missing data as possible, and carry out follow-up out further.

FDA representative Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, indicated that those things might not be easily be accomplished due to regulatory constraints and the financial costs, and that to do so there would be need for community effort among stakeholders, including collaborative efforts with existing prospective registries such as that run by the Vascular Quality Initiative.

One overall conclusion by both the FDA and panel members was that the quality of these and other such studies going forward must improve, by standardizing definitions and data forms to make studies more uniform across the industry. They reemphasized the need to work with the registries to get common data included, and to incorporate of insurance provider and Social Security death data as much as possible to help alleviate the lost follow-up problem.

SOURCE: Webcasts of the complete 2 days of the FDA panel meeting are available online.

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – There was sufficient evidence of a late mortality signal seen at 2-5 years post procedurally for paclitaxel-eluting stents and coated balloons to warrant a label change for the devices, the Food and Drug Administration’s Circulatory System Devices Panel unanimously agreed after 2 days of deliberation.

That signal was brought to light in a meta-analysis published last December by Konstantinos Katsanos, MD, of Patras University Hospital, Rion, Greece, and colleagues (J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e011245). Although there were concerns about the quality of the industry data used in the study, the caliber of the analysis itself and the subsequent data presented by the FDA to the panel were deemed sufficient to recommend a warning of concern to patients and providers.

Much of the new data from industry and large database registries presented to the panel, which was chaired by Richard A. Lange, MD, indicated a lessening to no evidence of the mortality effect. But this evidence was deemed insufficient to counter the evidence of the randomized controlled trials individually and collectively as presented in the Katsanos meta-analysis and subsequent information presented by the FDA that examined various parameters in a variety of sensitivity analyses that confirmed the late mortality signal. There was also concern that the industry and the registry analyses presented were not peer reviewed.

However, the panel also determined that it would be inappropriate to pull the devices from the market and from general use for several reasons.

One key reason was that, according to the panel, there was no mechanistic cause apparent for the late mortality. In addition, no convincing dose-response data could be teased from the preclinical and clinical trials studied because of their variability of devices, application methods, and lack of appropriate tissue analysis across studies.

Finally, the industry data used to create the meta-analysis were considered to be fundamentally flawed: in blinding, in the relatively small numbers of patients, and in the large percentage of patients lost to follow-up. The latter could have dramatically influenced the perceived results, especially as the studies were not powered or designed to follow mortality over such a period of time, according to the panel.

These limitations to the signal were especially important to the panel because of the obvious benefits with regard to quality of life provided to patients from these devices, which were attested to during the 2-day meeting by numerous presenters from industry, medical organizations – including societies and nonprofits – and providers.

In responding to FDA requests on a variety of concerns, the panel reiterated that there was a credible mortality signal, but that they could not be confident about the magnitude and whether it was caused by the paclitaxel treatment or some factor in the design or conduct of the studies. In addition, the panel members felt that they could neither confirm nor eliminate a class effect, given the fact that the information was based on a meta-analysis and thus none of the included devices could safely be removed from consideration.

They suggested that further safety information should be obtained, potentially by assessing and perhaps altering data collection in 29 ongoing studies over the next 5 years or so in more than 10,000 patients.

In addition, several of the panel members felt that additional animal studies might be performed including the use of older rat models; and using animal models that mimicked the kind of comorbidities present in the treated population, such as diabetes and atherosclerosis. They suggested cross-company industry cooperation with the FDA on these models, including looking at drug interactions and mimicking the dose application of stents/balloons.

Both the FDA representative and the panel were especially concerned with the benefit/risk profile.

The recommendation to still market the devices with a label warning was warranted, according to many members of the panel. They pointed to the clear benefits in quality of life and the lowered need for revascularization despite the evidence of the mortality signal, which, while statistically significant, could not be pinned town with regard to mechanisms or specific causes of death.

Overall, there was a concern that there should be a dialogue between patients and their doctors to discuss clear short-term benefits with unknown long-term risk, and that the label should support this by clearly mentioning the mortality signal that was found, although there was no attempt to develop exact wording.

Panel member Joaquin E. Cigarroa, MD, head of cardiovascular medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, suggested with regard to labeling that a statement “that ‘there may be’ – not ‘there is’ – a late mortality signal, should be included.”

Panel member John C. Somberg, MD, program director of clinical research and bioinformatics at Rush University in Lake Bluff, Ill., stated: “The label should say something like, ‘when looking at a meta-analysis that combined all studies with stents and balloons that carried paclitaxel, there may be a late mortality, which must be balanced against an early and sustained benefit in terms of pain on walking and potential loss of circulation to your extremity.’ ”

Other panel members thought that the meta-analysis should not be privileged and that somehow the totality of the evidence should somehow be distilled down into the label, including the evidence against the signal.

“We’re meeting because of a signal, of a concern – an honest, well-meaning concern – of increased mortality. And my opinion is that the patients need to be informed of it,” said Dr. Lange, president, Texas Tech University, El Paso.

Some members of the panel felt that it may not be justifiable to use these devices in patients with low intrinsic risk and low recurrence risk, and the whole spectrum of patients may need to be considered in further studies to figure out the subgroups that have more benefits and more risks, and also to consider how to mitigate risks in patients who receive the device, whether through medical therapy or lifestyle modification.

In particular, Frank W. LoGerfo, MD, the William V. McDermott Distinguished Professor of Surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, stated: “Interventions for claudication should be extremely rare. It rarely progresses, and the pain should be worked through by exercise with low risk of limb loss.” He added that intervention with these devices “takes away options. Trading life for something that is not limb-threatening is something we should not be considering.”

There was no firm consensus on whether new randomized trials should be done, although they were of course the ideal solution. Kevin E. Kip, PhD, Distinguished USF Health Professor at the University of South Florida, Tampa, and others argued that, whether new trials were necessary or not, to deal with the safety question in a timely fashion, existing trials have to capture as much of the missing data as possible, and carry out follow-up out further.

FDA representative Bram Zuckerman, MD, director of the Office of Cardiovascular Devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, indicated that those things might not be easily be accomplished due to regulatory constraints and the financial costs, and that to do so there would be need for community effort among stakeholders, including collaborative efforts with existing prospective registries such as that run by the Vascular Quality Initiative.

One overall conclusion by both the FDA and panel members was that the quality of these and other such studies going forward must improve, by standardizing definitions and data forms to make studies more uniform across the industry. They reemphasized the need to work with the registries to get common data included, and to incorporate of insurance provider and Social Security death data as much as possible to help alleviate the lost follow-up problem.

SOURCE: Webcasts of the complete 2 days of the FDA panel meeting are available online.

REPORTING FROM AN FDA PANEL MEETING

Good health goes beyond having a doctor and insurance, says AMA’s equity chief

Part of Dr. Aletha Maybank’s medical training left a sour taste in her mouth.

Her superiors told her not to worry about nonmedical issues affecting her patients’ quality of life, she said, because social workers would handle it. But she didn’t understand how physicians could divorce medical advice from the context of patients’ lives.

“How can you offer advice as recommendations that’s not even relevant to how their day to day plays out?” Dr. Maybank asked.

Today, Dr. Maybank is continuing to question that medical school philosophy. She was recently named the first chief health equity officer for the American Medical Association. In that job, she is responsible for implementing practices among doctors across the country to help end disparities in care. She has a full agenda, including launching the group’s Center for Health Equity and helping the Chicago-based doctors association reach out to people in poor neighborhoods in the city.

A pediatrician, Dr. Maybank previously worked for the New York City government as deputy commissioner for the health department and founding director of the city’s health equity center.

Carmen Heredia Rodriguez of Kaiser Health News recently spoke with Dr. Maybank about her new role and how health inequities affect Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell me what health equity means to you, and what are some of the main drivers that are keeping health inequitable in this country?

The AMA policy around health equity is optimal health for all people.

But it’s not just an outcome; there’s a process to get there. How do we engage with people? How do we look at and collect our data to make sure our practices and processes are equitable? How do we hire differently to ensure diversity? All these things are processes to achieve health equity.

In order to understand what produces inequities, we have to understand what creates health. Health is created outside of the walls of the doctor’s office and at the hospital. What are patients’ jobs and employment like? The kind of education they have. Income. Their ability to build wealth. All of these are conditions that impact health.

Q: Is there anything along your career path that really surprised you about the state of health care in the United States?

There’s the perception that all of our health is really determined by whether you have a doctor or not, or if you have insurance. What creates health is much beyond that.

So if we really want to work on health and equity, we have to partner with people who are in the education space and the economic space and the housing spaces, because that’s where health inequities are produced. You could have insurance coverage. You could have a primary care doctor. But it doesn’t mean that you’re not going to experience health inequities.

Q: Discrimination based on racial lines is one obvious driver of health inequities. What are some of the other populations that are affected by health inequity?

I think structural racism is a system that affects us all.

It’s not just the black-white issue. So, whether it’s discrimination or inequities that exist among LGBT youth and transgender [or] nonconforming people, or if it’s folks who are immigrants or women, a lot of that is contextualized under the umbrella of white supremacy within the country.

Q: And what are some of your priorities?

A large part of my work will be how I build the organizational capacity to better understand health equity. The reality in this country is folks aren’t comfortable talking about those issues. So, we have to destigmatize talking about all of this.

Q: Are there any particular populations or relationships that you plan to focus on?

The AMA excluded black physicians until the 1960s. So one question is: How do we work to heal relationships as well as understand the impact of our past actions? The AMA definitely issued an apology in the early 2000s, and my new role is also a step in the right direction. However, there is more that we can and should do.

Another priority now is: How do we work, and who do we work with, in our own backyard of Chicago? What can we do to work directly with people experiencing the greatest burden of disease? How do we ensure that we acknowledge the power, assets and expertise of communities so that we have the process and solutions driven and led by communities? To that end, we’ve begun working with West Side United via a relationship at Rush Medical Center. West Side United is a community-driven, collective neighborhood planning, implementation and investment effort geared toward optimizing economic well-being and improved health outcomes.

Q: Is there anything else you feel is important to understand about health equity?

Health equity and social determinants of health have become jargon. But we are talking about people’s lives. We were all born equal. We are clearly not all treated equal, but we all deserve equity. I don’t live outside of it, and none of us really do. I am one of those women who were three to four times more likely to die at childbirth because I’m black. So I don’t live outside of this experience. I’m talking about my own life.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Part of Dr. Aletha Maybank’s medical training left a sour taste in her mouth.

Her superiors told her not to worry about nonmedical issues affecting her patients’ quality of life, she said, because social workers would handle it. But she didn’t understand how physicians could divorce medical advice from the context of patients’ lives.

“How can you offer advice as recommendations that’s not even relevant to how their day to day plays out?” Dr. Maybank asked.

Today, Dr. Maybank is continuing to question that medical school philosophy. She was recently named the first chief health equity officer for the American Medical Association. In that job, she is responsible for implementing practices among doctors across the country to help end disparities in care. She has a full agenda, including launching the group’s Center for Health Equity and helping the Chicago-based doctors association reach out to people in poor neighborhoods in the city.

A pediatrician, Dr. Maybank previously worked for the New York City government as deputy commissioner for the health department and founding director of the city’s health equity center.

Carmen Heredia Rodriguez of Kaiser Health News recently spoke with Dr. Maybank about her new role and how health inequities affect Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell me what health equity means to you, and what are some of the main drivers that are keeping health inequitable in this country?

The AMA policy around health equity is optimal health for all people.

But it’s not just an outcome; there’s a process to get there. How do we engage with people? How do we look at and collect our data to make sure our practices and processes are equitable? How do we hire differently to ensure diversity? All these things are processes to achieve health equity.

In order to understand what produces inequities, we have to understand what creates health. Health is created outside of the walls of the doctor’s office and at the hospital. What are patients’ jobs and employment like? The kind of education they have. Income. Their ability to build wealth. All of these are conditions that impact health.

Q: Is there anything along your career path that really surprised you about the state of health care in the United States?

There’s the perception that all of our health is really determined by whether you have a doctor or not, or if you have insurance. What creates health is much beyond that.

So if we really want to work on health and equity, we have to partner with people who are in the education space and the economic space and the housing spaces, because that’s where health inequities are produced. You could have insurance coverage. You could have a primary care doctor. But it doesn’t mean that you’re not going to experience health inequities.

Q: Discrimination based on racial lines is one obvious driver of health inequities. What are some of the other populations that are affected by health inequity?

I think structural racism is a system that affects us all.

It’s not just the black-white issue. So, whether it’s discrimination or inequities that exist among LGBT youth and transgender [or] nonconforming people, or if it’s folks who are immigrants or women, a lot of that is contextualized under the umbrella of white supremacy within the country.

Q: And what are some of your priorities?

A large part of my work will be how I build the organizational capacity to better understand health equity. The reality in this country is folks aren’t comfortable talking about those issues. So, we have to destigmatize talking about all of this.

Q: Are there any particular populations or relationships that you plan to focus on?

The AMA excluded black physicians until the 1960s. So one question is: How do we work to heal relationships as well as understand the impact of our past actions? The AMA definitely issued an apology in the early 2000s, and my new role is also a step in the right direction. However, there is more that we can and should do.

Another priority now is: How do we work, and who do we work with, in our own backyard of Chicago? What can we do to work directly with people experiencing the greatest burden of disease? How do we ensure that we acknowledge the power, assets and expertise of communities so that we have the process and solutions driven and led by communities? To that end, we’ve begun working with West Side United via a relationship at Rush Medical Center. West Side United is a community-driven, collective neighborhood planning, implementation and investment effort geared toward optimizing economic well-being and improved health outcomes.

Q: Is there anything else you feel is important to understand about health equity?

Health equity and social determinants of health have become jargon. But we are talking about people’s lives. We were all born equal. We are clearly not all treated equal, but we all deserve equity. I don’t live outside of it, and none of us really do. I am one of those women who were three to four times more likely to die at childbirth because I’m black. So I don’t live outside of this experience. I’m talking about my own life.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Part of Dr. Aletha Maybank’s medical training left a sour taste in her mouth.

Her superiors told her not to worry about nonmedical issues affecting her patients’ quality of life, she said, because social workers would handle it. But she didn’t understand how physicians could divorce medical advice from the context of patients’ lives.

“How can you offer advice as recommendations that’s not even relevant to how their day to day plays out?” Dr. Maybank asked.

Today, Dr. Maybank is continuing to question that medical school philosophy. She was recently named the first chief health equity officer for the American Medical Association. In that job, she is responsible for implementing practices among doctors across the country to help end disparities in care. She has a full agenda, including launching the group’s Center for Health Equity and helping the Chicago-based doctors association reach out to people in poor neighborhoods in the city.

A pediatrician, Dr. Maybank previously worked for the New York City government as deputy commissioner for the health department and founding director of the city’s health equity center.

Carmen Heredia Rodriguez of Kaiser Health News recently spoke with Dr. Maybank about her new role and how health inequities affect Americans. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Can you tell me what health equity means to you, and what are some of the main drivers that are keeping health inequitable in this country?

The AMA policy around health equity is optimal health for all people.

But it’s not just an outcome; there’s a process to get there. How do we engage with people? How do we look at and collect our data to make sure our practices and processes are equitable? How do we hire differently to ensure diversity? All these things are processes to achieve health equity.

In order to understand what produces inequities, we have to understand what creates health. Health is created outside of the walls of the doctor’s office and at the hospital. What are patients’ jobs and employment like? The kind of education they have. Income. Their ability to build wealth. All of these are conditions that impact health.

Q: Is there anything along your career path that really surprised you about the state of health care in the United States?

There’s the perception that all of our health is really determined by whether you have a doctor or not, or if you have insurance. What creates health is much beyond that.

So if we really want to work on health and equity, we have to partner with people who are in the education space and the economic space and the housing spaces, because that’s where health inequities are produced. You could have insurance coverage. You could have a primary care doctor. But it doesn’t mean that you’re not going to experience health inequities.

Q: Discrimination based on racial lines is one obvious driver of health inequities. What are some of the other populations that are affected by health inequity?

I think structural racism is a system that affects us all.

It’s not just the black-white issue. So, whether it’s discrimination or inequities that exist among LGBT youth and transgender [or] nonconforming people, or if it’s folks who are immigrants or women, a lot of that is contextualized under the umbrella of white supremacy within the country.

Q: And what are some of your priorities?

A large part of my work will be how I build the organizational capacity to better understand health equity. The reality in this country is folks aren’t comfortable talking about those issues. So, we have to destigmatize talking about all of this.

Q: Are there any particular populations or relationships that you plan to focus on?

The AMA excluded black physicians until the 1960s. So one question is: How do we work to heal relationships as well as understand the impact of our past actions? The AMA definitely issued an apology in the early 2000s, and my new role is also a step in the right direction. However, there is more that we can and should do.

Another priority now is: How do we work, and who do we work with, in our own backyard of Chicago? What can we do to work directly with people experiencing the greatest burden of disease? How do we ensure that we acknowledge the power, assets and expertise of communities so that we have the process and solutions driven and led by communities? To that end, we’ve begun working with West Side United via a relationship at Rush Medical Center. West Side United is a community-driven, collective neighborhood planning, implementation and investment effort geared toward optimizing economic well-being and improved health outcomes.

Q: Is there anything else you feel is important to understand about health equity?

Health equity and social determinants of health have become jargon. But we are talking about people’s lives. We were all born equal. We are clearly not all treated equal, but we all deserve equity. I don’t live outside of it, and none of us really do. I am one of those women who were three to four times more likely to die at childbirth because I’m black. So I don’t live outside of this experience. I’m talking about my own life.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

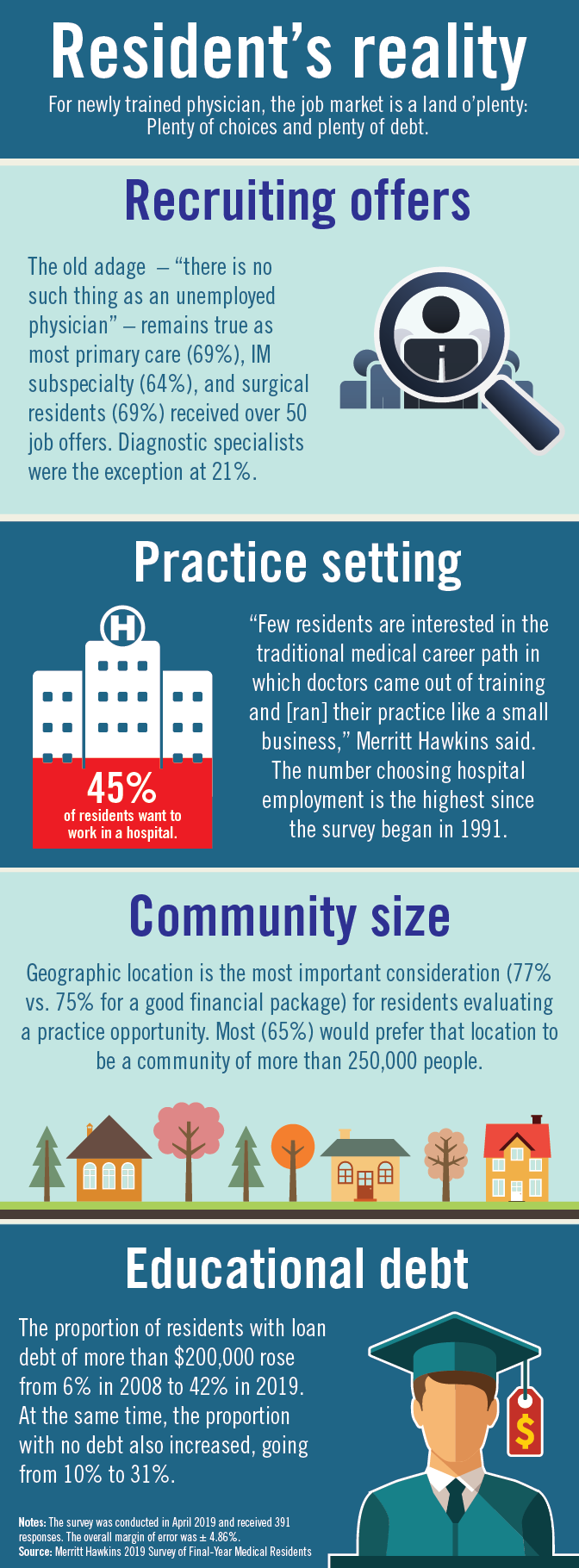

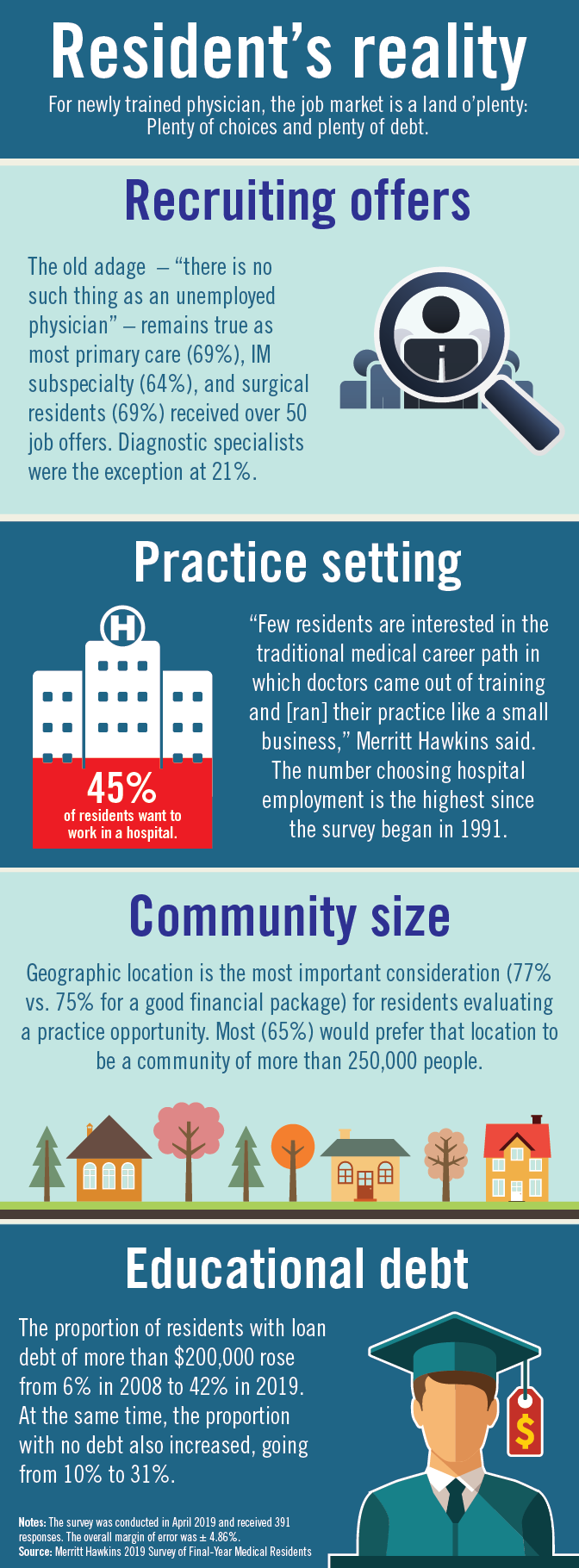

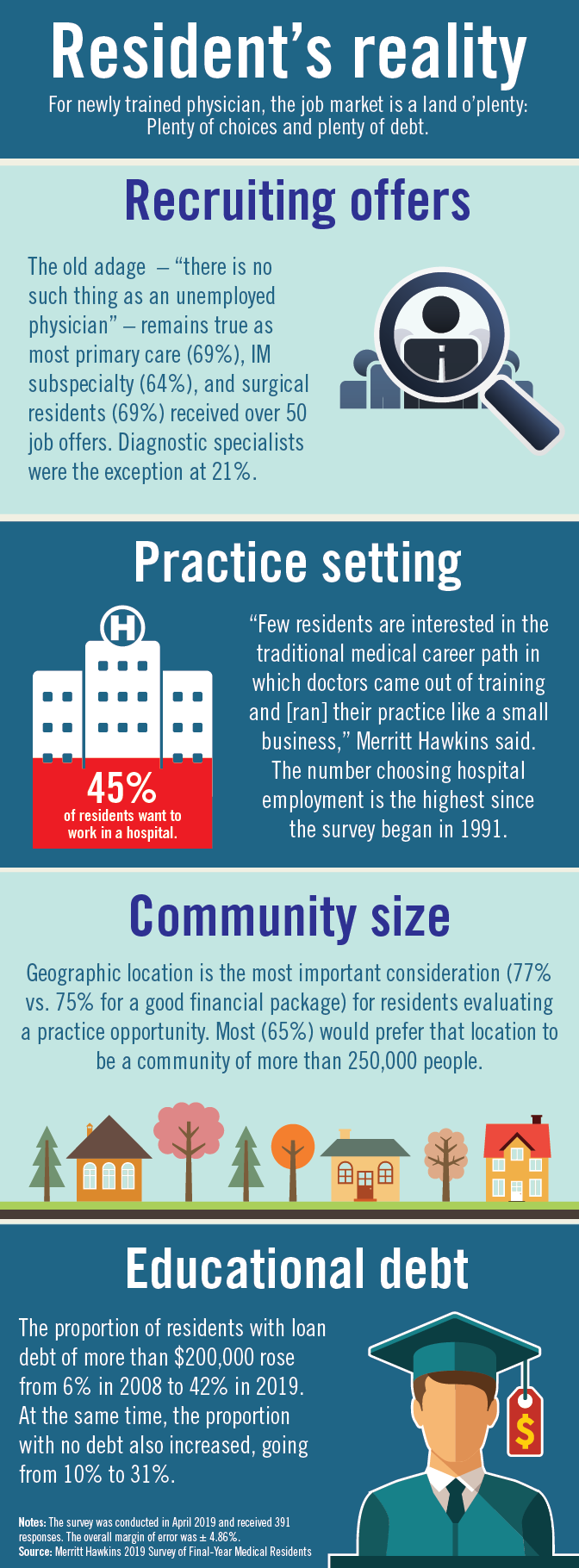

Residents are drowning in job offers – and debt

Physician search firm Merritt Hawkins did – actually, they heard from 391 residents – and 64% said that they had been contacted too many times by recruiters.

“Physicians coming out of training are being recruited like blue-chip athletes,” Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “There are simply not enough new doctors to go around.”

Merritt Hawkins asked physicians in their final year of residency about career choices, practice plans, and finances. Most said that they would prefer to be employed by a hospital or group practice, and a majority want to practice in a community with a population of 250,000 or more. More than half of the residents owed over $150,000 in student loans, but there were considerable debt differences between U.S. and international medical graduates.

The specialty distribution of respondents was 50% primary care, 30% internal medicine subspecialty/other, 15% surgical, and 5% diagnostic. About three-quarters were U.S. graduates and one-quarter of the residents were international medical graduates in this latest survey in a series that has been conducted periodically since 1991.

The survey was conducted in April 2018.

Physician search firm Merritt Hawkins did – actually, they heard from 391 residents – and 64% said that they had been contacted too many times by recruiters.

“Physicians coming out of training are being recruited like blue-chip athletes,” Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “There are simply not enough new doctors to go around.”

Merritt Hawkins asked physicians in their final year of residency about career choices, practice plans, and finances. Most said that they would prefer to be employed by a hospital or group practice, and a majority want to practice in a community with a population of 250,000 or more. More than half of the residents owed over $150,000 in student loans, but there were considerable debt differences between U.S. and international medical graduates.

The specialty distribution of respondents was 50% primary care, 30% internal medicine subspecialty/other, 15% surgical, and 5% diagnostic. About three-quarters were U.S. graduates and one-quarter of the residents were international medical graduates in this latest survey in a series that has been conducted periodically since 1991.

The survey was conducted in April 2018.

Physician search firm Merritt Hawkins did – actually, they heard from 391 residents – and 64% said that they had been contacted too many times by recruiters.

“Physicians coming out of training are being recruited like blue-chip athletes,” Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “There are simply not enough new doctors to go around.”

Merritt Hawkins asked physicians in their final year of residency about career choices, practice plans, and finances. Most said that they would prefer to be employed by a hospital or group practice, and a majority want to practice in a community with a population of 250,000 or more. More than half of the residents owed over $150,000 in student loans, but there were considerable debt differences between U.S. and international medical graduates.

The specialty distribution of respondents was 50% primary care, 30% internal medicine subspecialty/other, 15% surgical, and 5% diagnostic. About three-quarters were U.S. graduates and one-quarter of the residents were international medical graduates in this latest survey in a series that has been conducted periodically since 1991.

The survey was conducted in April 2018.

Senators agree surprise medical bills must go. But how?

Two years, 16 hearings, and one massive bipartisan package of legislation later, a key Senate committee says it is ready to start marking up a bill the week of June 24 designed to contain health care costs. But it might not be easy since lawmakers and stakeholders at a final hearing June 18 showed they are still far apart on one simple aspect of the proposal.

That sticking point: a formula for paying for surprise medical bills, those unexpected and often high charges patients face when they get care from a doctor or hospital that isn’t in their insurance network.

“People get health insurance precisely so they won’t be surprised by health care bills,” said Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.), the coauthor of a separate proposal to tamp down surprise bills. “So it is completely unacceptable that people do everything that they’re supposed to do to ensure that their care is in their insurance network and then still end up with large, unexpected bills from an out-of-network provider.”

It’s a cause that has been taken up by President Donald Trump and various bipartisan groups of lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

The wide-ranging legislative package on curbing health care costs is sponsored by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), the chairman and ranking member, respectively, of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee. Given the committee’s influence, and because this legislation has bipartisan support in the Senate where not many bills are moving, industry observers are taking the HELP panel’s proposal very seriously.

The Alexander/Murray bill lays out three options for paying surprise medical bills but does not specify which path the final legislation should take. Advocates for each of the choices were among the five witnesses June 18.

Their positions fell along familiar fault lines. Everyone acknowledged that patients who stumble into a surprise bill because their emergency care was handled at a facility not in their insurance network or because a doctor at their in-network hospital doesn’t take the patient’s plan should not have to pay more than they would for an inpatient service. But they differ on how much doctors, hospitals, and other providers should be compensated and how the disputes should be resolved.

Tom Nickels, an executive vice president of the American Hospital Association, cautioned against using benchmarks to set pay levels, such as local customary averages or a price set in relation to Medicare. He said such a plan might underpay providers and hospitals could lose their leverage to negotiate with insurers.

Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of the Pacific Business Group on Health – a group that represents employers, including some who are self-insured who pay their workers’ health costs – said doctors should be paid 125% of what Medicare pays. She told senators that an independent arbitration process like the one Nickels advocates would add unnecessary costs to the system.

Benedic Ippolito, a researcher with the American Enterprise Institute, said requiring all providers in a hospital to be in-network was the cleanest solution.

“On surprise billing, all three approaches are equal in that first and foremost they protect the consumer,” said Sean Cavanaugh, chief administrative officer for Aledade, a company that matches primary care physicians with accountable care organizations.

There was also broad support among the witnesses for some of the legislation’s transparency measures, especially the creation of a nongovernmental nonprofit organization to collect claims data from private health plans, Medicare, and some states to create what’s called an all-payer claims database. That could help policymakers better understand the true cost of care, these experts told the committee.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) expressed trepidation about the all-payer claims database, noting that increased transparency could hurt rural hospitals, which typically charge higher prices than those in cities because their patient base is small and they need to bring in enough revenue to cover fixed costs.

The witnesses also offered support for eliminating “gag clauses” between doctors and health plans. These stipulations often prevent providers from telling patients the cost of a procedure or service.

“Patients and families absolutely have skin in the game ... but they are in a completely untenable and unfair situation. They have no information,” said Ms. Mitchell, from the Pacific Business Group on Health. “We’re talking about providers not being allowed to share information. ... Transparency is necessary so people can have active involvement.”

If one thing is clear, it’s that Sen. Alexander doesn’t want this summer to be a rehash of last year, when it appeared he had a bipartisan deal to address problems in the federal health law’s marketplaces before the effort fell apart.

“For the last decade, Congress had been locked in an argument about the individual health care market,” said Sen. Alexander at the hearing. “That is not this discussion. This is a different discussion. We’ll never lower the cost of health insurance until we lower the cost of health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Two years, 16 hearings, and one massive bipartisan package of legislation later, a key Senate committee says it is ready to start marking up a bill the week of June 24 designed to contain health care costs. But it might not be easy since lawmakers and stakeholders at a final hearing June 18 showed they are still far apart on one simple aspect of the proposal.

That sticking point: a formula for paying for surprise medical bills, those unexpected and often high charges patients face when they get care from a doctor or hospital that isn’t in their insurance network.

“People get health insurance precisely so they won’t be surprised by health care bills,” said Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.), the coauthor of a separate proposal to tamp down surprise bills. “So it is completely unacceptable that people do everything that they’re supposed to do to ensure that their care is in their insurance network and then still end up with large, unexpected bills from an out-of-network provider.”

It’s a cause that has been taken up by President Donald Trump and various bipartisan groups of lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

The wide-ranging legislative package on curbing health care costs is sponsored by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), the chairman and ranking member, respectively, of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee. Given the committee’s influence, and because this legislation has bipartisan support in the Senate where not many bills are moving, industry observers are taking the HELP panel’s proposal very seriously.

The Alexander/Murray bill lays out three options for paying surprise medical bills but does not specify which path the final legislation should take. Advocates for each of the choices were among the five witnesses June 18.

Their positions fell along familiar fault lines. Everyone acknowledged that patients who stumble into a surprise bill because their emergency care was handled at a facility not in their insurance network or because a doctor at their in-network hospital doesn’t take the patient’s plan should not have to pay more than they would for an inpatient service. But they differ on how much doctors, hospitals, and other providers should be compensated and how the disputes should be resolved.

Tom Nickels, an executive vice president of the American Hospital Association, cautioned against using benchmarks to set pay levels, such as local customary averages or a price set in relation to Medicare. He said such a plan might underpay providers and hospitals could lose their leverage to negotiate with insurers.

Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of the Pacific Business Group on Health – a group that represents employers, including some who are self-insured who pay their workers’ health costs – said doctors should be paid 125% of what Medicare pays. She told senators that an independent arbitration process like the one Nickels advocates would add unnecessary costs to the system.

Benedic Ippolito, a researcher with the American Enterprise Institute, said requiring all providers in a hospital to be in-network was the cleanest solution.

“On surprise billing, all three approaches are equal in that first and foremost they protect the consumer,” said Sean Cavanaugh, chief administrative officer for Aledade, a company that matches primary care physicians with accountable care organizations.

There was also broad support among the witnesses for some of the legislation’s transparency measures, especially the creation of a nongovernmental nonprofit organization to collect claims data from private health plans, Medicare, and some states to create what’s called an all-payer claims database. That could help policymakers better understand the true cost of care, these experts told the committee.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) expressed trepidation about the all-payer claims database, noting that increased transparency could hurt rural hospitals, which typically charge higher prices than those in cities because their patient base is small and they need to bring in enough revenue to cover fixed costs.

The witnesses also offered support for eliminating “gag clauses” between doctors and health plans. These stipulations often prevent providers from telling patients the cost of a procedure or service.

“Patients and families absolutely have skin in the game ... but they are in a completely untenable and unfair situation. They have no information,” said Ms. Mitchell, from the Pacific Business Group on Health. “We’re talking about providers not being allowed to share information. ... Transparency is necessary so people can have active involvement.”

If one thing is clear, it’s that Sen. Alexander doesn’t want this summer to be a rehash of last year, when it appeared he had a bipartisan deal to address problems in the federal health law’s marketplaces before the effort fell apart.

“For the last decade, Congress had been locked in an argument about the individual health care market,” said Sen. Alexander at the hearing. “That is not this discussion. This is a different discussion. We’ll never lower the cost of health insurance until we lower the cost of health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Two years, 16 hearings, and one massive bipartisan package of legislation later, a key Senate committee says it is ready to start marking up a bill the week of June 24 designed to contain health care costs. But it might not be easy since lawmakers and stakeholders at a final hearing June 18 showed they are still far apart on one simple aspect of the proposal.

That sticking point: a formula for paying for surprise medical bills, those unexpected and often high charges patients face when they get care from a doctor or hospital that isn’t in their insurance network.

“People get health insurance precisely so they won’t be surprised by health care bills,” said Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.), the coauthor of a separate proposal to tamp down surprise bills. “So it is completely unacceptable that people do everything that they’re supposed to do to ensure that their care is in their insurance network and then still end up with large, unexpected bills from an out-of-network provider.”

It’s a cause that has been taken up by President Donald Trump and various bipartisan groups of lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

The wide-ranging legislative package on curbing health care costs is sponsored by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), the chairman and ranking member, respectively, of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee. Given the committee’s influence, and because this legislation has bipartisan support in the Senate where not many bills are moving, industry observers are taking the HELP panel’s proposal very seriously.

The Alexander/Murray bill lays out three options for paying surprise medical bills but does not specify which path the final legislation should take. Advocates for each of the choices were among the five witnesses June 18.

Their positions fell along familiar fault lines. Everyone acknowledged that patients who stumble into a surprise bill because their emergency care was handled at a facility not in their insurance network or because a doctor at their in-network hospital doesn’t take the patient’s plan should not have to pay more than they would for an inpatient service. But they differ on how much doctors, hospitals, and other providers should be compensated and how the disputes should be resolved.

Tom Nickels, an executive vice president of the American Hospital Association, cautioned against using benchmarks to set pay levels, such as local customary averages or a price set in relation to Medicare. He said such a plan might underpay providers and hospitals could lose their leverage to negotiate with insurers.

Elizabeth Mitchell, president and CEO of the Pacific Business Group on Health – a group that represents employers, including some who are self-insured who pay their workers’ health costs – said doctors should be paid 125% of what Medicare pays. She told senators that an independent arbitration process like the one Nickels advocates would add unnecessary costs to the system.

Benedic Ippolito, a researcher with the American Enterprise Institute, said requiring all providers in a hospital to be in-network was the cleanest solution.

“On surprise billing, all three approaches are equal in that first and foremost they protect the consumer,” said Sean Cavanaugh, chief administrative officer for Aledade, a company that matches primary care physicians with accountable care organizations.

There was also broad support among the witnesses for some of the legislation’s transparency measures, especially the creation of a nongovernmental nonprofit organization to collect claims data from private health plans, Medicare, and some states to create what’s called an all-payer claims database. That could help policymakers better understand the true cost of care, these experts told the committee.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) expressed trepidation about the all-payer claims database, noting that increased transparency could hurt rural hospitals, which typically charge higher prices than those in cities because their patient base is small and they need to bring in enough revenue to cover fixed costs.

The witnesses also offered support for eliminating “gag clauses” between doctors and health plans. These stipulations often prevent providers from telling patients the cost of a procedure or service.

“Patients and families absolutely have skin in the game ... but they are in a completely untenable and unfair situation. They have no information,” said Ms. Mitchell, from the Pacific Business Group on Health. “We’re talking about providers not being allowed to share information. ... Transparency is necessary so people can have active involvement.”

If one thing is clear, it’s that Sen. Alexander doesn’t want this summer to be a rehash of last year, when it appeared he had a bipartisan deal to address problems in the federal health law’s marketplaces before the effort fell apart.

“For the last decade, Congress had been locked in an argument about the individual health care market,” said Sen. Alexander at the hearing. “That is not this discussion. This is a different discussion. We’ll never lower the cost of health insurance until we lower the cost of health care.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

No cardiovascular benefit from vitamin D supplementation

There are no benefits from vitamin D supplementation in reducing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality, according to a meta-analysis published in JAMA Cardiology.

Researchers analyzed data from 83,291 patients enrolled in 21 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of at least 1 year of vitamin D supplementation.

They found the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was the same among patients taking vitamin D supplements and those taking placebo (risk ratio, 1; P = .85). Even stratifying by age, sex, postmenopausal status, pretreatment vitamin D levels, vitamin D dosage and formulation, chronic kidney disease, or excluding studies that used vitamin D analogues made no significant difference.

However, there was the suggestion of reduced incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events with vitamin D supplementation in individuals of advanced age, but the authors wrote that the finding should be interpreted with caution.

The analysis found no benefit from vitamin D supplementation on the secondary endpoints of MI, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, or all-cause mortality risk.

Mahmoud Barbarawi, MD, from the Hurley Medical Center at Michigan State University, East Lansing, and coauthors commented that previous observational studies have found significant associations between low vitamin D levels and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

“However, observational studies are susceptible to uncontrolled confounding by outdoor physical activity, nutritional status, and prevalent chronic disease, which may influence serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels,” they wrote.

This updated analysis extended earlier clinical trial findings and added in some more-recent randomized trial outcomes, including the massive VITAL trial, which showed that neither daily vitamin D nor omega-3 fatty acids reduce cancer or cardiovascular event risk (N Engl J Med. 2019;380[1]:33-44).

Still, the authors noted that most of the trials included in the analysis had not prespecified cardiovascular disease as the primary endpoint and were underpowered to detect an effect on cardiovascular events. They also pointed out that few trials included data on heart failure, and a previous meta-analysis had suggested a potential benefit of supplementation in reducing the risk of this condition.

“Additional trials of higher-dose vitamin D supplementation, perhaps targeting members of older age groups and with attention to other [cardiovascular disease] endpoints such as heart failure, are of interest,” they wrote.

One author reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and in-kind support from the pharmaceutical sector for a vitamin D study. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Barbarawi M et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1870.

The past decade has seen a nearly 100-fold increase in vitamin D testing and supplementation, driven by a widespread fascination with the notion of vitamin D as a panacea. Vitamin D assessments alone are costing the United States an estimated $350 million annually.

Population and cohort studies have shown a clear link between vitamin D status and cardiovascular disease, but this link is complicated by the possibility that low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels may be a result of, rather than the cause of, cardiovascular disease.

The findings of this meta-analysis, that vitamin D supplementation does not reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, should support efforts to reduce unnecessary vitamin D testing and treatment in populations not at risk for deficiency or to prevent cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.

Arshed A. Quyyumi, MD, and Ibhar Al Mheid, MD, are from the division of cardiology at Emory University, Atlanta. The comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 19. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1906). No conflicts of interest were reported.

The past decade has seen a nearly 100-fold increase in vitamin D testing and supplementation, driven by a widespread fascination with the notion of vitamin D as a panacea. Vitamin D assessments alone are costing the United States an estimated $350 million annually.

Population and cohort studies have shown a clear link between vitamin D status and cardiovascular disease, but this link is complicated by the possibility that low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels may be a result of, rather than the cause of, cardiovascular disease.

The findings of this meta-analysis, that vitamin D supplementation does not reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, should support efforts to reduce unnecessary vitamin D testing and treatment in populations not at risk for deficiency or to prevent cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.

Arshed A. Quyyumi, MD, and Ibhar Al Mheid, MD, are from the division of cardiology at Emory University, Atlanta. The comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 19. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1906). No conflicts of interest were reported.

The past decade has seen a nearly 100-fold increase in vitamin D testing and supplementation, driven by a widespread fascination with the notion of vitamin D as a panacea. Vitamin D assessments alone are costing the United States an estimated $350 million annually.

Population and cohort studies have shown a clear link between vitamin D status and cardiovascular disease, but this link is complicated by the possibility that low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels may be a result of, rather than the cause of, cardiovascular disease.

The findings of this meta-analysis, that vitamin D supplementation does not reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality, should support efforts to reduce unnecessary vitamin D testing and treatment in populations not at risk for deficiency or to prevent cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.

Arshed A. Quyyumi, MD, and Ibhar Al Mheid, MD, are from the division of cardiology at Emory University, Atlanta. The comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 19. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1906). No conflicts of interest were reported.

There are no benefits from vitamin D supplementation in reducing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality, according to a meta-analysis published in JAMA Cardiology.

Researchers analyzed data from 83,291 patients enrolled in 21 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of at least 1 year of vitamin D supplementation.

They found the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was the same among patients taking vitamin D supplements and those taking placebo (risk ratio, 1; P = .85). Even stratifying by age, sex, postmenopausal status, pretreatment vitamin D levels, vitamin D dosage and formulation, chronic kidney disease, or excluding studies that used vitamin D analogues made no significant difference.

However, there was the suggestion of reduced incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events with vitamin D supplementation in individuals of advanced age, but the authors wrote that the finding should be interpreted with caution.

The analysis found no benefit from vitamin D supplementation on the secondary endpoints of MI, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, or all-cause mortality risk.

Mahmoud Barbarawi, MD, from the Hurley Medical Center at Michigan State University, East Lansing, and coauthors commented that previous observational studies have found significant associations between low vitamin D levels and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

“However, observational studies are susceptible to uncontrolled confounding by outdoor physical activity, nutritional status, and prevalent chronic disease, which may influence serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels,” they wrote.

This updated analysis extended earlier clinical trial findings and added in some more-recent randomized trial outcomes, including the massive VITAL trial, which showed that neither daily vitamin D nor omega-3 fatty acids reduce cancer or cardiovascular event risk (N Engl J Med. 2019;380[1]:33-44).

Still, the authors noted that most of the trials included in the analysis had not prespecified cardiovascular disease as the primary endpoint and were underpowered to detect an effect on cardiovascular events. They also pointed out that few trials included data on heart failure, and a previous meta-analysis had suggested a potential benefit of supplementation in reducing the risk of this condition.

“Additional trials of higher-dose vitamin D supplementation, perhaps targeting members of older age groups and with attention to other [cardiovascular disease] endpoints such as heart failure, are of interest,” they wrote.

One author reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and in-kind support from the pharmaceutical sector for a vitamin D study. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Barbarawi M et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1870.

There are no benefits from vitamin D supplementation in reducing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality, according to a meta-analysis published in JAMA Cardiology.

Researchers analyzed data from 83,291 patients enrolled in 21 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of at least 1 year of vitamin D supplementation.

They found the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was the same among patients taking vitamin D supplements and those taking placebo (risk ratio, 1; P = .85). Even stratifying by age, sex, postmenopausal status, pretreatment vitamin D levels, vitamin D dosage and formulation, chronic kidney disease, or excluding studies that used vitamin D analogues made no significant difference.

However, there was the suggestion of reduced incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events with vitamin D supplementation in individuals of advanced age, but the authors wrote that the finding should be interpreted with caution.

The analysis found no benefit from vitamin D supplementation on the secondary endpoints of MI, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, or all-cause mortality risk.

Mahmoud Barbarawi, MD, from the Hurley Medical Center at Michigan State University, East Lansing, and coauthors commented that previous observational studies have found significant associations between low vitamin D levels and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

“However, observational studies are susceptible to uncontrolled confounding by outdoor physical activity, nutritional status, and prevalent chronic disease, which may influence serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels,” they wrote.

This updated analysis extended earlier clinical trial findings and added in some more-recent randomized trial outcomes, including the massive VITAL trial, which showed that neither daily vitamin D nor omega-3 fatty acids reduce cancer or cardiovascular event risk (N Engl J Med. 2019;380[1]:33-44).

Still, the authors noted that most of the trials included in the analysis had not prespecified cardiovascular disease as the primary endpoint and were underpowered to detect an effect on cardiovascular events. They also pointed out that few trials included data on heart failure, and a previous meta-analysis had suggested a potential benefit of supplementation in reducing the risk of this condition.

“Additional trials of higher-dose vitamin D supplementation, perhaps targeting members of older age groups and with attention to other [cardiovascular disease] endpoints such as heart failure, are of interest,” they wrote.

One author reported receiving funding from the National Institutes of Health and in-kind support from the pharmaceutical sector for a vitamin D study. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Barbarawi M et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1870.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

View, Review VAM at Home with VAM on Demand Library

The inability to be in two places at one time makes VAM On Demand an essential component of the Vascular Annual Meeting.

VAM on Demand lets people review — in depth and on their own timeline —sessions they attended and “attend” electronically the ones they couldn’t in person. VAM on Demand will include hundreds of individual presentations, with accompanying PowerPoint slides and audio. Select video sessions will be available.

The fee is $199 for attendees after the meeting ends. (Non-attendees may purchase VAM on Demand for $499.) All purchasers receive unlimited access, plus downloads to the library, for up to one year. Access begins several weeks after VAM ends and will be available on the SVS website vascular.org.

Contact [email protected] with questions.

The inability to be in two places at one time makes VAM On Demand an essential component of the Vascular Annual Meeting.

VAM on Demand lets people review — in depth and on their own timeline —sessions they attended and “attend” electronically the ones they couldn’t in person. VAM on Demand will include hundreds of individual presentations, with accompanying PowerPoint slides and audio. Select video sessions will be available.