User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

CoC Grants Outstanding Achievement Award to 16 Cancer Care Facilitiesteaser

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has granted its year-end 2017 Outstanding Achievement Award to a select group of 16 accredited cancer programs throughout the U.S. Award criteria were based on qualitative and quantitative surveys of cancer programs conducted in the second half of 2017.

The purpose of the award is to raise the bar on quality cancer care, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness about quality care choices among cancer patients and their loved ones. In addition, the award is intended to accomplish the following:

• Recognize those cancer programs that achieve excellence in providing quality care to cancer patients

• Motivate other cancer programs to work toward improving their level of care

• Facilitate a dialogue between award recipients and health care professionals at other cancer facilities for the purpose of sharing best practices

• Encourage honorees to serve as quality-care resources to other cancer programs

The 16 award-winning cancer care programs represent approximately 7 percent of programs surveyed by the CoC July 1–December 31, 2017. “These cancer programs currently represent the best of the best when it comes to cancer care,” said Lawrence N. Shulman, MD, FACP, Chair of the CoC. “Each of these facilities is not just meeting nationally recognized standards for the delivery of quality cancer care, they are exceeding them.”

Visit the ACS website for a list of these award-winning cancer programs at facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/info/outstanding/2017-part-2.

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has granted its year-end 2017 Outstanding Achievement Award to a select group of 16 accredited cancer programs throughout the U.S. Award criteria were based on qualitative and quantitative surveys of cancer programs conducted in the second half of 2017.

The purpose of the award is to raise the bar on quality cancer care, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness about quality care choices among cancer patients and their loved ones. In addition, the award is intended to accomplish the following:

• Recognize those cancer programs that achieve excellence in providing quality care to cancer patients

• Motivate other cancer programs to work toward improving their level of care

• Facilitate a dialogue between award recipients and health care professionals at other cancer facilities for the purpose of sharing best practices

• Encourage honorees to serve as quality-care resources to other cancer programs

The 16 award-winning cancer care programs represent approximately 7 percent of programs surveyed by the CoC July 1–December 31, 2017. “These cancer programs currently represent the best of the best when it comes to cancer care,” said Lawrence N. Shulman, MD, FACP, Chair of the CoC. “Each of these facilities is not just meeting nationally recognized standards for the delivery of quality cancer care, they are exceeding them.”

Visit the ACS website for a list of these award-winning cancer programs at facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/info/outstanding/2017-part-2.

The Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has granted its year-end 2017 Outstanding Achievement Award to a select group of 16 accredited cancer programs throughout the U.S. Award criteria were based on qualitative and quantitative surveys of cancer programs conducted in the second half of 2017.

The purpose of the award is to raise the bar on quality cancer care, with the ultimate goal of increasing awareness about quality care choices among cancer patients and their loved ones. In addition, the award is intended to accomplish the following:

• Recognize those cancer programs that achieve excellence in providing quality care to cancer patients

• Motivate other cancer programs to work toward improving their level of care

• Facilitate a dialogue between award recipients and health care professionals at other cancer facilities for the purpose of sharing best practices

• Encourage honorees to serve as quality-care resources to other cancer programs

The 16 award-winning cancer care programs represent approximately 7 percent of programs surveyed by the CoC July 1–December 31, 2017. “These cancer programs currently represent the best of the best when it comes to cancer care,” said Lawrence N. Shulman, MD, FACP, Chair of the CoC. “Each of these facilities is not just meeting nationally recognized standards for the delivery of quality cancer care, they are exceeding them.”

Visit the ACS website for a list of these award-winning cancer programs at facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/info/outstanding/2017-part-2.

Dr. Steven Rosenberg Receives the 2018 ACS Jacobson Innovation Award

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2018 Jacobson Innovation Award to surgical oncologist Steven A. Rosenberg, MD, PhD, at a dinner held in his honor in Chicago, IL, on June 8. Dr. Rosenberg is chief of the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, MD; and a professor of surgery at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Bethesda, and at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

The prestigious Jacobson Innovation Award honors living surgeons who have been innovators of a new development or technique in any field of surgery and is made possible through a gift from Julius H. Jacobson II, MD, FACS, and his wife Joan. Dr. Jacobson is a general vascular surgeon known for his pioneering work in the development of microsurgery.

Dr. Rosenberg was honored with this international surgical award for his pioneering role in the development of immunotherapy and gene therapy. When Dr. Rosenberg began his work in immunotherapy in the late 1970s, little was known about T lymphocyte function in cancer, and there was no convincing evidence that any immune reaction existed in patients against their cancers. Despite this dearth of knowledge, Dr. Rosenberg developed the first effective immunotherapies for selected patients with advanced cancer and was the first to successfully insert foreign genes into humans. His studies of cell transfer immunotherapy resulted in durable complete remissions in patients with metastatic melanoma. Additionally, his studies of the adoptive transfer of genetically modified lymphocytes resulted in the regression of metastatic cancer in patients with melanoma, sarcomas, and lymphomas.

In his current role at the NCI, Dr. Rosenberg oversees the surgery branch’s extensive clinical program, which is aimed at translating scientific advances into effective immunotherapies for cancer patients. Dr. Rosenberg’s current research is focused on defining the host immune response of patients to their cancers. These studies emphasize the ability of human lymphocytes to recognize unique cancer antigens and the identification of anti-tumor T cell receptors that can be exploited to develop new cell transfer immunotherapies for the treatment of cancer patients. Dr. Rosenberg is currently an investigator in 14 clinical trials being conducted through the NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

Dr. Rosenberg has received numerous awards throughout his distinguished career. In 1981, he received a Meritorious Service Medal from the U.S. Public Health Service for pioneering work in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas and osteogenic sarcoma. He received that honor again in 1986 for his excellence and leadership in research and clinical investigation relating to the cellular biology and immunology of cancer treatment. Dr. Rosenberg also twice received the Armand Hammer Cancer Prize, in 1985 and 1988, for his cancer research accomplishments. In 1991, he received the highest honor given by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Karnofsky Prize. He was awarded the Flance-Karl Award, the highest honor given by the American Surgical Association, in 2002. In 2005, he received the Richard V. Smalley, MD, Memorial Award, which is the highest honor given by the International Society for Biological Therapy of Cancer. Most recently, he was named the recipient of the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society in 2015.

Dr. Rosenberg is currently a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and has served on its board of directors. He also is a member of the National Academy of Medicine, the Society of University Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, the American Association for Cancer Research, and the American Association of Immunologists, among others. He has authored more than 1,100 articles in scientific literature covering various aspects of cancer research, as well as eight books. He was the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Immunotherapy from 1990 to 1995, and again from 2000 to the present.

For a list of previous Jacobson Innovation Award winners, visit the ACS website at facs.org/about-acs/ governance/acs-committees/honorscommittee/jacobson-list.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2018 Jacobson Innovation Award to surgical oncologist Steven A. Rosenberg, MD, PhD, at a dinner held in his honor in Chicago, IL, on June 8. Dr. Rosenberg is chief of the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, MD; and a professor of surgery at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Bethesda, and at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

The prestigious Jacobson Innovation Award honors living surgeons who have been innovators of a new development or technique in any field of surgery and is made possible through a gift from Julius H. Jacobson II, MD, FACS, and his wife Joan. Dr. Jacobson is a general vascular surgeon known for his pioneering work in the development of microsurgery.

Dr. Rosenberg was honored with this international surgical award for his pioneering role in the development of immunotherapy and gene therapy. When Dr. Rosenberg began his work in immunotherapy in the late 1970s, little was known about T lymphocyte function in cancer, and there was no convincing evidence that any immune reaction existed in patients against their cancers. Despite this dearth of knowledge, Dr. Rosenberg developed the first effective immunotherapies for selected patients with advanced cancer and was the first to successfully insert foreign genes into humans. His studies of cell transfer immunotherapy resulted in durable complete remissions in patients with metastatic melanoma. Additionally, his studies of the adoptive transfer of genetically modified lymphocytes resulted in the regression of metastatic cancer in patients with melanoma, sarcomas, and lymphomas.

In his current role at the NCI, Dr. Rosenberg oversees the surgery branch’s extensive clinical program, which is aimed at translating scientific advances into effective immunotherapies for cancer patients. Dr. Rosenberg’s current research is focused on defining the host immune response of patients to their cancers. These studies emphasize the ability of human lymphocytes to recognize unique cancer antigens and the identification of anti-tumor T cell receptors that can be exploited to develop new cell transfer immunotherapies for the treatment of cancer patients. Dr. Rosenberg is currently an investigator in 14 clinical trials being conducted through the NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

Dr. Rosenberg has received numerous awards throughout his distinguished career. In 1981, he received a Meritorious Service Medal from the U.S. Public Health Service for pioneering work in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas and osteogenic sarcoma. He received that honor again in 1986 for his excellence and leadership in research and clinical investigation relating to the cellular biology and immunology of cancer treatment. Dr. Rosenberg also twice received the Armand Hammer Cancer Prize, in 1985 and 1988, for his cancer research accomplishments. In 1991, he received the highest honor given by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Karnofsky Prize. He was awarded the Flance-Karl Award, the highest honor given by the American Surgical Association, in 2002. In 2005, he received the Richard V. Smalley, MD, Memorial Award, which is the highest honor given by the International Society for Biological Therapy of Cancer. Most recently, he was named the recipient of the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society in 2015.

Dr. Rosenberg is currently a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and has served on its board of directors. He also is a member of the National Academy of Medicine, the Society of University Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, the American Association for Cancer Research, and the American Association of Immunologists, among others. He has authored more than 1,100 articles in scientific literature covering various aspects of cancer research, as well as eight books. He was the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Immunotherapy from 1990 to 1995, and again from 2000 to the present.

For a list of previous Jacobson Innovation Award winners, visit the ACS website at facs.org/about-acs/ governance/acs-committees/honorscommittee/jacobson-list.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) presented the 2018 Jacobson Innovation Award to surgical oncologist Steven A. Rosenberg, MD, PhD, at a dinner held in his honor in Chicago, IL, on June 8. Dr. Rosenberg is chief of the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda, MD; and a professor of surgery at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Bethesda, and at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

The prestigious Jacobson Innovation Award honors living surgeons who have been innovators of a new development or technique in any field of surgery and is made possible through a gift from Julius H. Jacobson II, MD, FACS, and his wife Joan. Dr. Jacobson is a general vascular surgeon known for his pioneering work in the development of microsurgery.

Dr. Rosenberg was honored with this international surgical award for his pioneering role in the development of immunotherapy and gene therapy. When Dr. Rosenberg began his work in immunotherapy in the late 1970s, little was known about T lymphocyte function in cancer, and there was no convincing evidence that any immune reaction existed in patients against their cancers. Despite this dearth of knowledge, Dr. Rosenberg developed the first effective immunotherapies for selected patients with advanced cancer and was the first to successfully insert foreign genes into humans. His studies of cell transfer immunotherapy resulted in durable complete remissions in patients with metastatic melanoma. Additionally, his studies of the adoptive transfer of genetically modified lymphocytes resulted in the regression of metastatic cancer in patients with melanoma, sarcomas, and lymphomas.

In his current role at the NCI, Dr. Rosenberg oversees the surgery branch’s extensive clinical program, which is aimed at translating scientific advances into effective immunotherapies for cancer patients. Dr. Rosenberg’s current research is focused on defining the host immune response of patients to their cancers. These studies emphasize the ability of human lymphocytes to recognize unique cancer antigens and the identification of anti-tumor T cell receptors that can be exploited to develop new cell transfer immunotherapies for the treatment of cancer patients. Dr. Rosenberg is currently an investigator in 14 clinical trials being conducted through the NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

Dr. Rosenberg has received numerous awards throughout his distinguished career. In 1981, he received a Meritorious Service Medal from the U.S. Public Health Service for pioneering work in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas and osteogenic sarcoma. He received that honor again in 1986 for his excellence and leadership in research and clinical investigation relating to the cellular biology and immunology of cancer treatment. Dr. Rosenberg also twice received the Armand Hammer Cancer Prize, in 1985 and 1988, for his cancer research accomplishments. In 1991, he received the highest honor given by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Karnofsky Prize. He was awarded the Flance-Karl Award, the highest honor given by the American Surgical Association, in 2002. In 2005, he received the Richard V. Smalley, MD, Memorial Award, which is the highest honor given by the International Society for Biological Therapy of Cancer. Most recently, he was named the recipient of the Medal of Honor from the American Cancer Society in 2015.

Dr. Rosenberg is currently a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and has served on its board of directors. He also is a member of the National Academy of Medicine, the Society of University Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, the American Association for Cancer Research, and the American Association of Immunologists, among others. He has authored more than 1,100 articles in scientific literature covering various aspects of cancer research, as well as eight books. He was the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Immunotherapy from 1990 to 1995, and again from 2000 to the present.

For a list of previous Jacobson Innovation Award winners, visit the ACS website at facs.org/about-acs/ governance/acs-committees/honorscommittee/jacobson-list.

The Right Choice? Modifiable risk factors and surgical decision making

In the July 26, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Ira L. Leeds, MD, David T. Efron, MD, FACS, and Lisa S. Lehmann, MD, raise the important issue of how to proceed when a patient has an indication for surgery and wants the surgery, but the patient has modifiable risk factors that make the likelihood of surgical complications high.1 Specifically, the authors describe a 45-year-old woman with morbid obesity and chronic opioid dependency who presented with a large incisional hernia. The patient suffers from debilitating pain and nausea that has been attributed to her hernia. She is homebound and is seeking a third opinion on repair of the hernia. She has smoked for 30 years and continues to do so after prior unsuccessful attempts to quit. She has been turned down previously by two surgeons who reportedly felt she was too high risk. Application of an all-procedure risk calculator has shown a 38% higher than average risk of a complication with an expected length of stay 80% longer than average.

I commend the authors for raising this set of issues for consideration. As surgeons, we routinely make decisions about what operations we recommend to patients based on the risks of the operation. However, we also allow significant latitude for patients to make individual decisions about assuming greater or lesser risks. If the patient’s surgical risks could be reduced by her stopping smoking and losing weight, should the surgeon insist upon those things being done before being willing to operate on the patient? The answer to this question depends on the perspective that one takes in viewing this case. If the surgeon’s relationship with the patient is primary and the potential benefit of surgery is clearly present, then one could view the considerations of lower public ranking and added costs to society as irrelevant. However, if a surgeon views his or her role as not only advocating for their patient, but also being a steward of societal resources, then the added resources necessary to get this patient safely through the operation are critically important to consider.

In order to come to a decision for this individual patient, the authors argue in favor of greater patient education of the surgical risk so the patient can appreciate the importance of modifying the risky behaviors prior to surgery. This concept of shared decision making with patients is certainly important and should be encouraged in any surgeon-patient interaction around a possible surgical intervention. The authors also note the importance of ensuring an alignment of values between the patient and the surgeon in why the operation might be undertaken. These suggestions are excellent and undoubtedly would lead to better relationships between surgeons and patients and also likely better decisions about when to operate.

My primary concern with the authors’ suggestions occurs when the authors encourage surgical professional societies to “develop consistent practice guidelines without partiality to any particular patient.” The authors make the claim that, in a complex case in which it is difficult to decide what is best for the patient, we would benefit from having more guidelines about what modifiable risk factors should preclude surgery.

I worry that the appeal to guidelines is too often an appeal to ignore the individual aspects of a patient’s condition and the impact that the condition has on a patient’s life. Rather than saying, “What we need is more guidelines,” I would much prefer we emphasize the need for more communication between surgeons and patients about the risks of surgery and the implications of recovery on the patient’s quality of life. Although there is nothing detrimental to gathering data about the impact of modifiable risks on surgical outcomes, I am concerned that guidelines may become viewed as parameters of “good” patient care. We all know that no guideline can account for all the individual values and goals a patient may have and, thus, we ought not use guidelines to shield us from the complex individual decision making that as surgeons we should engage in with each of our patients.

Reference

1. Leeds IL et al. Surgical gatekeeping – modifiable risk factors and ethical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1802079.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

In the July 26, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Ira L. Leeds, MD, David T. Efron, MD, FACS, and Lisa S. Lehmann, MD, raise the important issue of how to proceed when a patient has an indication for surgery and wants the surgery, but the patient has modifiable risk factors that make the likelihood of surgical complications high.1 Specifically, the authors describe a 45-year-old woman with morbid obesity and chronic opioid dependency who presented with a large incisional hernia. The patient suffers from debilitating pain and nausea that has been attributed to her hernia. She is homebound and is seeking a third opinion on repair of the hernia. She has smoked for 30 years and continues to do so after prior unsuccessful attempts to quit. She has been turned down previously by two surgeons who reportedly felt she was too high risk. Application of an all-procedure risk calculator has shown a 38% higher than average risk of a complication with an expected length of stay 80% longer than average.

I commend the authors for raising this set of issues for consideration. As surgeons, we routinely make decisions about what operations we recommend to patients based on the risks of the operation. However, we also allow significant latitude for patients to make individual decisions about assuming greater or lesser risks. If the patient’s surgical risks could be reduced by her stopping smoking and losing weight, should the surgeon insist upon those things being done before being willing to operate on the patient? The answer to this question depends on the perspective that one takes in viewing this case. If the surgeon’s relationship with the patient is primary and the potential benefit of surgery is clearly present, then one could view the considerations of lower public ranking and added costs to society as irrelevant. However, if a surgeon views his or her role as not only advocating for their patient, but also being a steward of societal resources, then the added resources necessary to get this patient safely through the operation are critically important to consider.

In order to come to a decision for this individual patient, the authors argue in favor of greater patient education of the surgical risk so the patient can appreciate the importance of modifying the risky behaviors prior to surgery. This concept of shared decision making with patients is certainly important and should be encouraged in any surgeon-patient interaction around a possible surgical intervention. The authors also note the importance of ensuring an alignment of values between the patient and the surgeon in why the operation might be undertaken. These suggestions are excellent and undoubtedly would lead to better relationships between surgeons and patients and also likely better decisions about when to operate.

My primary concern with the authors’ suggestions occurs when the authors encourage surgical professional societies to “develop consistent practice guidelines without partiality to any particular patient.” The authors make the claim that, in a complex case in which it is difficult to decide what is best for the patient, we would benefit from having more guidelines about what modifiable risk factors should preclude surgery.

I worry that the appeal to guidelines is too often an appeal to ignore the individual aspects of a patient’s condition and the impact that the condition has on a patient’s life. Rather than saying, “What we need is more guidelines,” I would much prefer we emphasize the need for more communication between surgeons and patients about the risks of surgery and the implications of recovery on the patient’s quality of life. Although there is nothing detrimental to gathering data about the impact of modifiable risks on surgical outcomes, I am concerned that guidelines may become viewed as parameters of “good” patient care. We all know that no guideline can account for all the individual values and goals a patient may have and, thus, we ought not use guidelines to shield us from the complex individual decision making that as surgeons we should engage in with each of our patients.

Reference

1. Leeds IL et al. Surgical gatekeeping – modifiable risk factors and ethical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1802079.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

In the July 26, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, Ira L. Leeds, MD, David T. Efron, MD, FACS, and Lisa S. Lehmann, MD, raise the important issue of how to proceed when a patient has an indication for surgery and wants the surgery, but the patient has modifiable risk factors that make the likelihood of surgical complications high.1 Specifically, the authors describe a 45-year-old woman with morbid obesity and chronic opioid dependency who presented with a large incisional hernia. The patient suffers from debilitating pain and nausea that has been attributed to her hernia. She is homebound and is seeking a third opinion on repair of the hernia. She has smoked for 30 years and continues to do so after prior unsuccessful attempts to quit. She has been turned down previously by two surgeons who reportedly felt she was too high risk. Application of an all-procedure risk calculator has shown a 38% higher than average risk of a complication with an expected length of stay 80% longer than average.

I commend the authors for raising this set of issues for consideration. As surgeons, we routinely make decisions about what operations we recommend to patients based on the risks of the operation. However, we also allow significant latitude for patients to make individual decisions about assuming greater or lesser risks. If the patient’s surgical risks could be reduced by her stopping smoking and losing weight, should the surgeon insist upon those things being done before being willing to operate on the patient? The answer to this question depends on the perspective that one takes in viewing this case. If the surgeon’s relationship with the patient is primary and the potential benefit of surgery is clearly present, then one could view the considerations of lower public ranking and added costs to society as irrelevant. However, if a surgeon views his or her role as not only advocating for their patient, but also being a steward of societal resources, then the added resources necessary to get this patient safely through the operation are critically important to consider.

In order to come to a decision for this individual patient, the authors argue in favor of greater patient education of the surgical risk so the patient can appreciate the importance of modifying the risky behaviors prior to surgery. This concept of shared decision making with patients is certainly important and should be encouraged in any surgeon-patient interaction around a possible surgical intervention. The authors also note the importance of ensuring an alignment of values between the patient and the surgeon in why the operation might be undertaken. These suggestions are excellent and undoubtedly would lead to better relationships between surgeons and patients and also likely better decisions about when to operate.

My primary concern with the authors’ suggestions occurs when the authors encourage surgical professional societies to “develop consistent practice guidelines without partiality to any particular patient.” The authors make the claim that, in a complex case in which it is difficult to decide what is best for the patient, we would benefit from having more guidelines about what modifiable risk factors should preclude surgery.

I worry that the appeal to guidelines is too often an appeal to ignore the individual aspects of a patient’s condition and the impact that the condition has on a patient’s life. Rather than saying, “What we need is more guidelines,” I would much prefer we emphasize the need for more communication between surgeons and patients about the risks of surgery and the implications of recovery on the patient’s quality of life. Although there is nothing detrimental to gathering data about the impact of modifiable risks on surgical outcomes, I am concerned that guidelines may become viewed as parameters of “good” patient care. We all know that no guideline can account for all the individual values and goals a patient may have and, thus, we ought not use guidelines to shield us from the complex individual decision making that as surgeons we should engage in with each of our patients.

Reference

1. Leeds IL et al. Surgical gatekeeping – modifiable risk factors and ethical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 26. doi:10.1056/NEJMms1802079.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

Register for 2018 ACS-AEI Postgraduate Course by August 31

Attend the Annual American College of Surgeons Accredited Educational Institutes (ACS-AEI) Postgraduate Course, Novice to Expert: Let’s Get It Done, September 14–15 at the Mayo Clinic Multidisciplinary Simulation Center, Rochester, MN, to learn new techniques in simulation education that will meet the needs of all levels of learners, from novice to expert. Succinct presentations and hands-on activities at the simulation center will expose attendees to useful ideas, initiatives, and best practices that can be incorporated at their respective centers. The deadline to register for the course is August 31.

Sessions on Friday, September 14, will take place at the host hotel, the DoubleTree by Hilton Rochester—Mayo Clinic Area, and will feature simulation presentations that address learners at the Novice, Advanced Beginner, Competent, Proficient, and Expert levels. The day will end with a special cocktail reception and dinner at the historic Mayo Foundation House, where you will enjoy networking and making connections with fellow attendees for more relevant research and educational efforts. Saturday, September 15, will begin with a tour of the simulation center, followed by interactive activities that showcase Mayo’s strengths, including the Surgical X-Games, low-fidelity models, assessment, Maintenance of Certification for anesthesiology, and more. View the complete course agenda at facs.org/~/media/files/education/aei/pg_course_agenda_2018.ashx.

Registrants are offered a special booking rate at the DoubleTree by Hilton Rochester—Mayo Clinic Area. Reservations may be made by booking online at bit.ly/2mviB8Q or by calling 507-281-8000 and mentioning the American College of Surgeons September 2018 Meeting. Hotel reservations must be made by August 22 to qualify for the group rate.

Visit the postgraduate course web page at facs.org/education/accreditation/aei/pgcourse for more details and to register. Contact Cathy Sormalis at [email protected] with questions.

Attend the Annual American College of Surgeons Accredited Educational Institutes (ACS-AEI) Postgraduate Course, Novice to Expert: Let’s Get It Done, September 14–15 at the Mayo Clinic Multidisciplinary Simulation Center, Rochester, MN, to learn new techniques in simulation education that will meet the needs of all levels of learners, from novice to expert. Succinct presentations and hands-on activities at the simulation center will expose attendees to useful ideas, initiatives, and best practices that can be incorporated at their respective centers. The deadline to register for the course is August 31.

Sessions on Friday, September 14, will take place at the host hotel, the DoubleTree by Hilton Rochester—Mayo Clinic Area, and will feature simulation presentations that address learners at the Novice, Advanced Beginner, Competent, Proficient, and Expert levels. The day will end with a special cocktail reception and dinner at the historic Mayo Foundation House, where you will enjoy networking and making connections with fellow attendees for more relevant research and educational efforts. Saturday, September 15, will begin with a tour of the simulation center, followed by interactive activities that showcase Mayo’s strengths, including the Surgical X-Games, low-fidelity models, assessment, Maintenance of Certification for anesthesiology, and more. View the complete course agenda at facs.org/~/media/files/education/aei/pg_course_agenda_2018.ashx.

Registrants are offered a special booking rate at the DoubleTree by Hilton Rochester—Mayo Clinic Area. Reservations may be made by booking online at bit.ly/2mviB8Q or by calling 507-281-8000 and mentioning the American College of Surgeons September 2018 Meeting. Hotel reservations must be made by August 22 to qualify for the group rate.

Visit the postgraduate course web page at facs.org/education/accreditation/aei/pgcourse for more details and to register. Contact Cathy Sormalis at [email protected] with questions.

Attend the Annual American College of Surgeons Accredited Educational Institutes (ACS-AEI) Postgraduate Course, Novice to Expert: Let’s Get It Done, September 14–15 at the Mayo Clinic Multidisciplinary Simulation Center, Rochester, MN, to learn new techniques in simulation education that will meet the needs of all levels of learners, from novice to expert. Succinct presentations and hands-on activities at the simulation center will expose attendees to useful ideas, initiatives, and best practices that can be incorporated at their respective centers. The deadline to register for the course is August 31.

Sessions on Friday, September 14, will take place at the host hotel, the DoubleTree by Hilton Rochester—Mayo Clinic Area, and will feature simulation presentations that address learners at the Novice, Advanced Beginner, Competent, Proficient, and Expert levels. The day will end with a special cocktail reception and dinner at the historic Mayo Foundation House, where you will enjoy networking and making connections with fellow attendees for more relevant research and educational efforts. Saturday, September 15, will begin with a tour of the simulation center, followed by interactive activities that showcase Mayo’s strengths, including the Surgical X-Games, low-fidelity models, assessment, Maintenance of Certification for anesthesiology, and more. View the complete course agenda at facs.org/~/media/files/education/aei/pg_course_agenda_2018.ashx.

Registrants are offered a special booking rate at the DoubleTree by Hilton Rochester—Mayo Clinic Area. Reservations may be made by booking online at bit.ly/2mviB8Q or by calling 507-281-8000 and mentioning the American College of Surgeons September 2018 Meeting. Hotel reservations must be made by August 22 to qualify for the group rate.

Visit the postgraduate course web page at facs.org/education/accreditation/aei/pgcourse for more details and to register. Contact Cathy Sormalis at [email protected] with questions.

Inaugural recipient of ACS Surgical History Group Archives Fellowship announced

The Surgical History Group (SHG) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has awarded the inaugural Archives fellowship to David E. Clark, MD, FACS, of Portland, ME, to fund his research project, How the Great War Accelerated the Transfer of Global Leadership from Europe to America, and How the Developing ACS Helped Enable This Transition.

This annual fellowship begins July 1, and Dr. Clark will present his research findings at the SHG Breakfast Meeting at the ACS Clinical Congress 2019 in San Francisco, CA. Dr. Clark will receive a $2,000 stipend funded by the ACS Archives and the ACS Foundation’s Archives Fund.

The SHG fellowship supports research in surgical history that uses the resources of the ACS Archives, which includes records of the ACS in Chicago, IL, and the Orr Collection in Omaha, NE. Nine applicants submitted proposals on a variety of research topics this year, and applications were evaluated by the Archives Fellowship Selection Committee of the SHG.

For more information about the ACS Archives and the SHG, visit the ACS Archives web page at facs.org/about-acs/archives.

The Archives Fund was established to support the mission and operations of the ACS Archives. Direct contributions to support the Archives Fund are welcome. Fellows wishing to make tax-deductible gifts to fund this program are encouraged to contact the ACS Foundation at 312-202-5338.

The Surgical History Group (SHG) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has awarded the inaugural Archives fellowship to David E. Clark, MD, FACS, of Portland, ME, to fund his research project, How the Great War Accelerated the Transfer of Global Leadership from Europe to America, and How the Developing ACS Helped Enable This Transition.

This annual fellowship begins July 1, and Dr. Clark will present his research findings at the SHG Breakfast Meeting at the ACS Clinical Congress 2019 in San Francisco, CA. Dr. Clark will receive a $2,000 stipend funded by the ACS Archives and the ACS Foundation’s Archives Fund.

The SHG fellowship supports research in surgical history that uses the resources of the ACS Archives, which includes records of the ACS in Chicago, IL, and the Orr Collection in Omaha, NE. Nine applicants submitted proposals on a variety of research topics this year, and applications were evaluated by the Archives Fellowship Selection Committee of the SHG.

For more information about the ACS Archives and the SHG, visit the ACS Archives web page at facs.org/about-acs/archives.

The Archives Fund was established to support the mission and operations of the ACS Archives. Direct contributions to support the Archives Fund are welcome. Fellows wishing to make tax-deductible gifts to fund this program are encouraged to contact the ACS Foundation at 312-202-5338.

The Surgical History Group (SHG) of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) has awarded the inaugural Archives fellowship to David E. Clark, MD, FACS, of Portland, ME, to fund his research project, How the Great War Accelerated the Transfer of Global Leadership from Europe to America, and How the Developing ACS Helped Enable This Transition.

This annual fellowship begins July 1, and Dr. Clark will present his research findings at the SHG Breakfast Meeting at the ACS Clinical Congress 2019 in San Francisco, CA. Dr. Clark will receive a $2,000 stipend funded by the ACS Archives and the ACS Foundation’s Archives Fund.

The SHG fellowship supports research in surgical history that uses the resources of the ACS Archives, which includes records of the ACS in Chicago, IL, and the Orr Collection in Omaha, NE. Nine applicants submitted proposals on a variety of research topics this year, and applications were evaluated by the Archives Fellowship Selection Committee of the SHG.

For more information about the ACS Archives and the SHG, visit the ACS Archives web page at facs.org/about-acs/archives.

The Archives Fund was established to support the mission and operations of the ACS Archives. Direct contributions to support the Archives Fund are welcome. Fellows wishing to make tax-deductible gifts to fund this program are encouraged to contact the ACS Foundation at 312-202-5338.

George H.A. Clowes, MD, FACS Memorial Career Development Awardee for 2018 announced

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has announced that Luke Funk, MD, MPH, FACS, of Madison, WI, has been selected to receive the 2018 George H.A. Clowes, MD, FACS Memorial Career Development Award. Dr. Funk is an assistant professor in the department of surgery at University of Wisconsin-Madison. His awarded research project is Identifying and Addressing Barriers to Severe Obesity Care.

Dr. Funk anticipates that his research will help him to complete a program of research focused on identifying and addressing barriers to severe obesity care and bariatric surgery. The primary objectives of his study are to better understand how severely obese patients and their primary care providers (PCPs) make obesity treatment decisions and to pilot-test an educational tool designed to improve shared decision-making and optimize treatment for severely obese patients.

The requirements for this award are posted to the ACS website at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/research/acsclowes.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has announced that Luke Funk, MD, MPH, FACS, of Madison, WI, has been selected to receive the 2018 George H.A. Clowes, MD, FACS Memorial Career Development Award. Dr. Funk is an assistant professor in the department of surgery at University of Wisconsin-Madison. His awarded research project is Identifying and Addressing Barriers to Severe Obesity Care.

Dr. Funk anticipates that his research will help him to complete a program of research focused on identifying and addressing barriers to severe obesity care and bariatric surgery. The primary objectives of his study are to better understand how severely obese patients and their primary care providers (PCPs) make obesity treatment decisions and to pilot-test an educational tool designed to improve shared decision-making and optimize treatment for severely obese patients.

The requirements for this award are posted to the ACS website at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/research/acsclowes.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has announced that Luke Funk, MD, MPH, FACS, of Madison, WI, has been selected to receive the 2018 George H.A. Clowes, MD, FACS Memorial Career Development Award. Dr. Funk is an assistant professor in the department of surgery at University of Wisconsin-Madison. His awarded research project is Identifying and Addressing Barriers to Severe Obesity Care.

Dr. Funk anticipates that his research will help him to complete a program of research focused on identifying and addressing barriers to severe obesity care and bariatric surgery. The primary objectives of his study are to better understand how severely obese patients and their primary care providers (PCPs) make obesity treatment decisions and to pilot-test an educational tool designed to improve shared decision-making and optimize treatment for severely obese patients.

The requirements for this award are posted to the ACS website at facs.org/member-services/scholarships/research/acsclowes.

Doctors decry inaction on physician-focused APMs

Doctors have expressed their displeasure at the lack of response by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to launch physician-focused advanced alternative payment models (APMs).

As part of the MACRA law, Congress created a process by which physicians could seek to implement specialty-specific APMs that they had developed and tested. The purpose was to provide more avenues for specialist participation in the Quality Payment Program’s APM track.

The process goes like this: Doctors create and implement an APM that focuses on providing value-based care in their particular specialty arena. They submit the program and early outcomes to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee or PTAC. The committee reviews the APM and, if it has merit, forwards it to the CMS. The CMS can either approve the APM or ask for additional testing.

So far, PTAC has sent at least 10 APMs to the CMS. To date, not a single one has been approved or even tested on a limited scale.

“Physicians want to be engaged and involved in this process,” David Barbe, MD, immediate past president of the American Medical Association, told members of the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee during a July 26 hearing. “PTAC was created for that very reason. They have received dozens of proposals that come from the ground level. Physicians that are practicing know what will work in their practices and perhaps in their specialty. And yet, none of these have been adopted by CMS or really, we think, given serious consideration.”

Frank Opelka, MD, medical director for quality and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, noted that a proposal they had submitted to PTAC appears to be the one that has gotten furthest along in the process.

The model was “accepted in a letter by the Secretary for consideration by the [CMS Innovation Center],” Dr. Opelka testified at the hearing. “The innovation center had a few conference calls with us and one 2-hour in-person meeting on a product that we’d developed that took almost 5 years in the making. There are no resources and no capability in the innovation center to complete a design and then to create an implementation and have a sandbox or pilot area in which to test. The PTAC has done a fantastic job. The Secretary vetted us. I think [ours was] the only one that went from the Secretary and was recommended to the innovation center and it died in there because [the Center] is just not wired to really innovate and we really need to turn that on.”

The CMS issued a letter on June 13 essentially rejecting eight of the models that PTAC recommended. The AMA asked the agency to reconsider at least four of the proposals in a June 21 letter.

AMA leadership does not think that the CMS gave serious consideration to any of the PTAC recommendations, Dr. Barbe said. “These span from very focused proposals in GI medicine to reduce rehospitalization in Crohn’s patients all the way up to the end-stage renal disease that could have very broad effect on improving care and reducing cost for dialysis patients. We think there is great opportunity there if CMS will listen to us.”

The AMA is “especially concerned because the statute to reform Medicare physician payment provided only 6 years of bonus payments to facilitate physicians’ migration to APMs,” according to the group’s letter to the CMS. “We are approaching the 3-year mark for the initial implementation and there is still not a robust APM pathway for physicians.”

Dr. Barbe also expressed concern that physicians’ taste for innovation could wane, given 3 years without successful implementation or testing of a physician-focused APM.

The CMS “seems to be interested in coming up with ideas on their own and I think that’s not only reinventing the wheel potentially, but it is not taking advantage of some very creative and innovated proposals that have come forward,” Dr. Barbe said.

The AMA recognizes “that the APMs recommended by PTAC needed some refinement. Data and pilot test experience likely would help in addressing some of the concerns raised by both PTAC and HHS,” according to the letter. “PTAC has indicated in its recommendations to HHS that it felt the issues it had identified could be resolved with assistance from CMS. Moreover, PTAC concluded that the positive attributes of the APM proposals outweigh the concerns they had identified, but the department does not seem to agree.”

Dr. Opelka, in his written testimony to the subcommittee, suggested that “it may be invaluable to commission a study on these challenges, including CMS’ ability to measure the true quality of care provided by physicians of all specialties, the availability of cost measures that are meaningful and actionable in concert with these quality measures, physicians’ ability to access patient health information when they need it and in a standardized predictable format, and the availability of APMs that grant physicians of all specialties the opportunity to be creative in using their expertise to increase quality and value of care to the patient.”

Doctors have expressed their displeasure at the lack of response by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to launch physician-focused advanced alternative payment models (APMs).

As part of the MACRA law, Congress created a process by which physicians could seek to implement specialty-specific APMs that they had developed and tested. The purpose was to provide more avenues for specialist participation in the Quality Payment Program’s APM track.

The process goes like this: Doctors create and implement an APM that focuses on providing value-based care in their particular specialty arena. They submit the program and early outcomes to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee or PTAC. The committee reviews the APM and, if it has merit, forwards it to the CMS. The CMS can either approve the APM or ask for additional testing.

So far, PTAC has sent at least 10 APMs to the CMS. To date, not a single one has been approved or even tested on a limited scale.

“Physicians want to be engaged and involved in this process,” David Barbe, MD, immediate past president of the American Medical Association, told members of the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee during a July 26 hearing. “PTAC was created for that very reason. They have received dozens of proposals that come from the ground level. Physicians that are practicing know what will work in their practices and perhaps in their specialty. And yet, none of these have been adopted by CMS or really, we think, given serious consideration.”

Frank Opelka, MD, medical director for quality and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, noted that a proposal they had submitted to PTAC appears to be the one that has gotten furthest along in the process.

The model was “accepted in a letter by the Secretary for consideration by the [CMS Innovation Center],” Dr. Opelka testified at the hearing. “The innovation center had a few conference calls with us and one 2-hour in-person meeting on a product that we’d developed that took almost 5 years in the making. There are no resources and no capability in the innovation center to complete a design and then to create an implementation and have a sandbox or pilot area in which to test. The PTAC has done a fantastic job. The Secretary vetted us. I think [ours was] the only one that went from the Secretary and was recommended to the innovation center and it died in there because [the Center] is just not wired to really innovate and we really need to turn that on.”

The CMS issued a letter on June 13 essentially rejecting eight of the models that PTAC recommended. The AMA asked the agency to reconsider at least four of the proposals in a June 21 letter.

AMA leadership does not think that the CMS gave serious consideration to any of the PTAC recommendations, Dr. Barbe said. “These span from very focused proposals in GI medicine to reduce rehospitalization in Crohn’s patients all the way up to the end-stage renal disease that could have very broad effect on improving care and reducing cost for dialysis patients. We think there is great opportunity there if CMS will listen to us.”

The AMA is “especially concerned because the statute to reform Medicare physician payment provided only 6 years of bonus payments to facilitate physicians’ migration to APMs,” according to the group’s letter to the CMS. “We are approaching the 3-year mark for the initial implementation and there is still not a robust APM pathway for physicians.”

Dr. Barbe also expressed concern that physicians’ taste for innovation could wane, given 3 years without successful implementation or testing of a physician-focused APM.

The CMS “seems to be interested in coming up with ideas on their own and I think that’s not only reinventing the wheel potentially, but it is not taking advantage of some very creative and innovated proposals that have come forward,” Dr. Barbe said.

The AMA recognizes “that the APMs recommended by PTAC needed some refinement. Data and pilot test experience likely would help in addressing some of the concerns raised by both PTAC and HHS,” according to the letter. “PTAC has indicated in its recommendations to HHS that it felt the issues it had identified could be resolved with assistance from CMS. Moreover, PTAC concluded that the positive attributes of the APM proposals outweigh the concerns they had identified, but the department does not seem to agree.”

Dr. Opelka, in his written testimony to the subcommittee, suggested that “it may be invaluable to commission a study on these challenges, including CMS’ ability to measure the true quality of care provided by physicians of all specialties, the availability of cost measures that are meaningful and actionable in concert with these quality measures, physicians’ ability to access patient health information when they need it and in a standardized predictable format, and the availability of APMs that grant physicians of all specialties the opportunity to be creative in using their expertise to increase quality and value of care to the patient.”

Doctors have expressed their displeasure at the lack of response by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to launch physician-focused advanced alternative payment models (APMs).

As part of the MACRA law, Congress created a process by which physicians could seek to implement specialty-specific APMs that they had developed and tested. The purpose was to provide more avenues for specialist participation in the Quality Payment Program’s APM track.

The process goes like this: Doctors create and implement an APM that focuses on providing value-based care in their particular specialty arena. They submit the program and early outcomes to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee or PTAC. The committee reviews the APM and, if it has merit, forwards it to the CMS. The CMS can either approve the APM or ask for additional testing.

So far, PTAC has sent at least 10 APMs to the CMS. To date, not a single one has been approved or even tested on a limited scale.

“Physicians want to be engaged and involved in this process,” David Barbe, MD, immediate past president of the American Medical Association, told members of the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee during a July 26 hearing. “PTAC was created for that very reason. They have received dozens of proposals that come from the ground level. Physicians that are practicing know what will work in their practices and perhaps in their specialty. And yet, none of these have been adopted by CMS or really, we think, given serious consideration.”

Frank Opelka, MD, medical director for quality and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, noted that a proposal they had submitted to PTAC appears to be the one that has gotten furthest along in the process.

The model was “accepted in a letter by the Secretary for consideration by the [CMS Innovation Center],” Dr. Opelka testified at the hearing. “The innovation center had a few conference calls with us and one 2-hour in-person meeting on a product that we’d developed that took almost 5 years in the making. There are no resources and no capability in the innovation center to complete a design and then to create an implementation and have a sandbox or pilot area in which to test. The PTAC has done a fantastic job. The Secretary vetted us. I think [ours was] the only one that went from the Secretary and was recommended to the innovation center and it died in there because [the Center] is just not wired to really innovate and we really need to turn that on.”

The CMS issued a letter on June 13 essentially rejecting eight of the models that PTAC recommended. The AMA asked the agency to reconsider at least four of the proposals in a June 21 letter.

AMA leadership does not think that the CMS gave serious consideration to any of the PTAC recommendations, Dr. Barbe said. “These span from very focused proposals in GI medicine to reduce rehospitalization in Crohn’s patients all the way up to the end-stage renal disease that could have very broad effect on improving care and reducing cost for dialysis patients. We think there is great opportunity there if CMS will listen to us.”

The AMA is “especially concerned because the statute to reform Medicare physician payment provided only 6 years of bonus payments to facilitate physicians’ migration to APMs,” according to the group’s letter to the CMS. “We are approaching the 3-year mark for the initial implementation and there is still not a robust APM pathway for physicians.”

Dr. Barbe also expressed concern that physicians’ taste for innovation could wane, given 3 years without successful implementation or testing of a physician-focused APM.

The CMS “seems to be interested in coming up with ideas on their own and I think that’s not only reinventing the wheel potentially, but it is not taking advantage of some very creative and innovated proposals that have come forward,” Dr. Barbe said.

The AMA recognizes “that the APMs recommended by PTAC needed some refinement. Data and pilot test experience likely would help in addressing some of the concerns raised by both PTAC and HHS,” according to the letter. “PTAC has indicated in its recommendations to HHS that it felt the issues it had identified could be resolved with assistance from CMS. Moreover, PTAC concluded that the positive attributes of the APM proposals outweigh the concerns they had identified, but the department does not seem to agree.”

Dr. Opelka, in his written testimony to the subcommittee, suggested that “it may be invaluable to commission a study on these challenges, including CMS’ ability to measure the true quality of care provided by physicians of all specialties, the availability of cost measures that are meaningful and actionable in concert with these quality measures, physicians’ ability to access patient health information when they need it and in a standardized predictable format, and the availability of APMs that grant physicians of all specialties the opportunity to be creative in using their expertise to increase quality and value of care to the patient.”

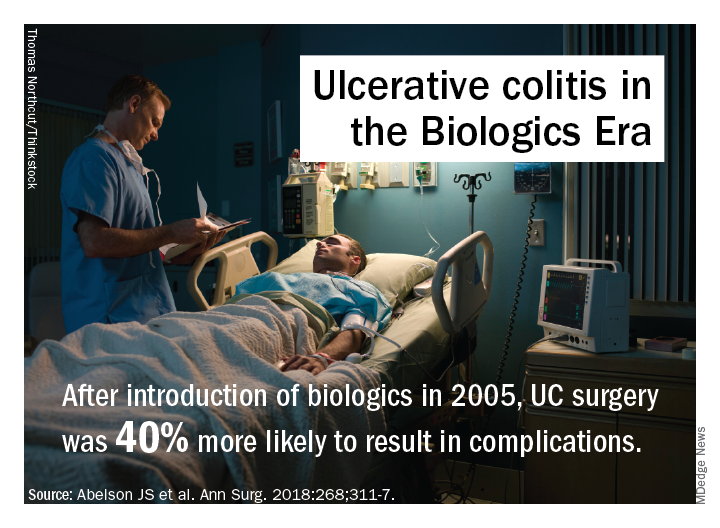

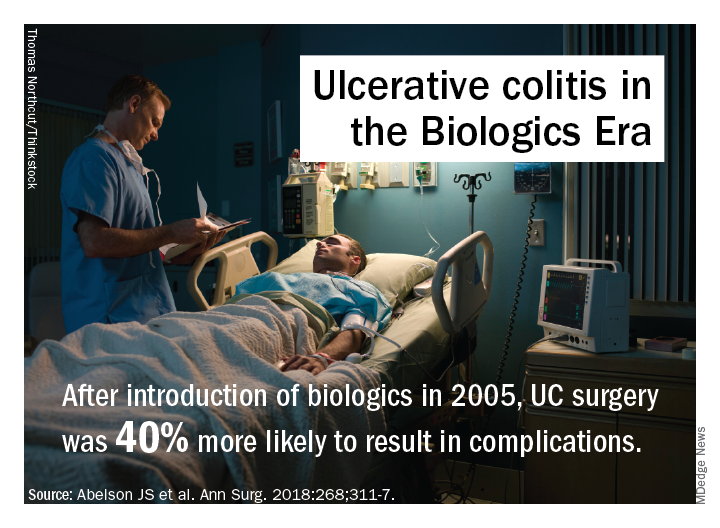

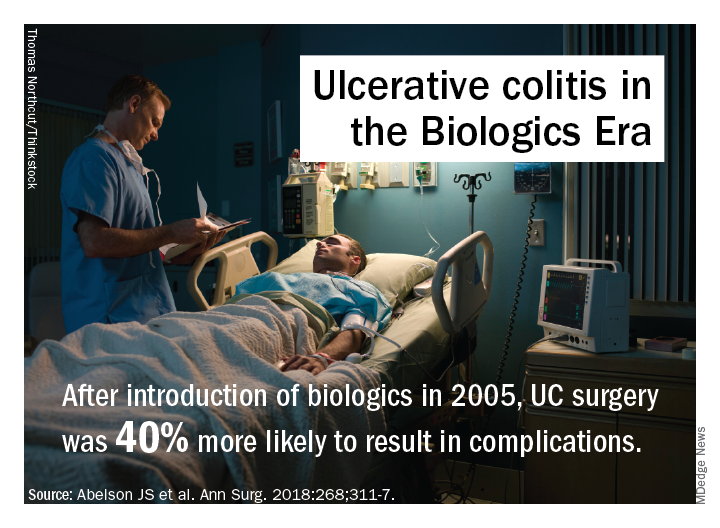

Surgical outcomes for UC worse since introduction of biologics

Since the approval of more UC patients are having multiple operations to manage their disease and their surgical outcomes tend to be worse, according to a study published in Annals of Surgery.

“Encouragingly, early randomized controlled trials demonstrated that infliximab may reduce the short-term need for surgery,” wrote Jonathan Abelson, MD, of the department of surgery, Cornell University, New York, and his coauthors. “However, even after the development and approval of several other biologic agents to treat UC, 30%-66% of patients treated with biologic agents still ultimately require surgical intervention.”

The study reviewed records of 7,070 patients with UC in a New York State Department of Health database who had colorectal surgery in two comparative time periods: 3,803 from 1995 to 2005, before biologics were available, and 3,267 from 2006 to 2013, after infliximab was approved. Dr. Abelson and coauthors said this is the first study to look at long-term surgical outcomes in a large group of patients with UC over an extended time period. Previous studies have reported conflicting results of how biologic agents for UC can impact surgical outcomes. The researchers set out to explore two hypotheses: whether staged procedures increased after 2005 and whether UC patients had worse outcomes over the past decade. The study results validated both hypotheses. Up until 2005, the proportion of patients who underwent at least three procedures after the index hospitalization was 9%; after 2006, that proportion was 14% (P less than .01).

A potential explanation for trends in postsurgery death may be higher rates of Clostridium difficile after 2005 (10.6% vs. 5.8%; P less than .01), but that was accounted for in the adjusted analysis and is probably not a major factor, the researchers said. After 2006 patients were slightly older and more likely to be on Medicare and nonwhite; they also were sicker, with 28% having two or more comorbidities vs. 10% before 2006.

The investigators offered another explanation: “It is also possible that the immunosuppressive effect of biologic agents ... predisposes patients to worse postoperative outcomes. In addition, it is possible that patients are referred for surgery too late in their disease course because of prolonged medical therapy.”

Dr. Abelson and coauthors reported having no financial relationships.

SOURCE: Abelson JS et al. Ann Surg. 2018:268;311-7.

Since the approval of more UC patients are having multiple operations to manage their disease and their surgical outcomes tend to be worse, according to a study published in Annals of Surgery.

“Encouragingly, early randomized controlled trials demonstrated that infliximab may reduce the short-term need for surgery,” wrote Jonathan Abelson, MD, of the department of surgery, Cornell University, New York, and his coauthors. “However, even after the development and approval of several other biologic agents to treat UC, 30%-66% of patients treated with biologic agents still ultimately require surgical intervention.”

The study reviewed records of 7,070 patients with UC in a New York State Department of Health database who had colorectal surgery in two comparative time periods: 3,803 from 1995 to 2005, before biologics were available, and 3,267 from 2006 to 2013, after infliximab was approved. Dr. Abelson and coauthors said this is the first study to look at long-term surgical outcomes in a large group of patients with UC over an extended time period. Previous studies have reported conflicting results of how biologic agents for UC can impact surgical outcomes. The researchers set out to explore two hypotheses: whether staged procedures increased after 2005 and whether UC patients had worse outcomes over the past decade. The study results validated both hypotheses. Up until 2005, the proportion of patients who underwent at least three procedures after the index hospitalization was 9%; after 2006, that proportion was 14% (P less than .01).

A potential explanation for trends in postsurgery death may be higher rates of Clostridium difficile after 2005 (10.6% vs. 5.8%; P less than .01), but that was accounted for in the adjusted analysis and is probably not a major factor, the researchers said. After 2006 patients were slightly older and more likely to be on Medicare and nonwhite; they also were sicker, with 28% having two or more comorbidities vs. 10% before 2006.

The investigators offered another explanation: “It is also possible that the immunosuppressive effect of biologic agents ... predisposes patients to worse postoperative outcomes. In addition, it is possible that patients are referred for surgery too late in their disease course because of prolonged medical therapy.”

Dr. Abelson and coauthors reported having no financial relationships.

SOURCE: Abelson JS et al. Ann Surg. 2018:268;311-7.

Since the approval of more UC patients are having multiple operations to manage their disease and their surgical outcomes tend to be worse, according to a study published in Annals of Surgery.

“Encouragingly, early randomized controlled trials demonstrated that infliximab may reduce the short-term need for surgery,” wrote Jonathan Abelson, MD, of the department of surgery, Cornell University, New York, and his coauthors. “However, even after the development and approval of several other biologic agents to treat UC, 30%-66% of patients treated with biologic agents still ultimately require surgical intervention.”

The study reviewed records of 7,070 patients with UC in a New York State Department of Health database who had colorectal surgery in two comparative time periods: 3,803 from 1995 to 2005, before biologics were available, and 3,267 from 2006 to 2013, after infliximab was approved. Dr. Abelson and coauthors said this is the first study to look at long-term surgical outcomes in a large group of patients with UC over an extended time period. Previous studies have reported conflicting results of how biologic agents for UC can impact surgical outcomes. The researchers set out to explore two hypotheses: whether staged procedures increased after 2005 and whether UC patients had worse outcomes over the past decade. The study results validated both hypotheses. Up until 2005, the proportion of patients who underwent at least three procedures after the index hospitalization was 9%; after 2006, that proportion was 14% (P less than .01).

A potential explanation for trends in postsurgery death may be higher rates of Clostridium difficile after 2005 (10.6% vs. 5.8%; P less than .01), but that was accounted for in the adjusted analysis and is probably not a major factor, the researchers said. After 2006 patients were slightly older and more likely to be on Medicare and nonwhite; they also were sicker, with 28% having two or more comorbidities vs. 10% before 2006.

The investigators offered another explanation: “It is also possible that the immunosuppressive effect of biologic agents ... predisposes patients to worse postoperative outcomes. In addition, it is possible that patients are referred for surgery too late in their disease course because of prolonged medical therapy.”

Dr. Abelson and coauthors reported having no financial relationships.

SOURCE: Abelson JS et al. Ann Surg. 2018:268;311-7.

FROM ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Rates of multiple surgeries for ulcerative colitis have increased since biologic agents were introduced.

Major finding: Fourteen percent of patients have had multiple operations since 2006 vs. 9% before that.

Study details: A longitudinal analysis of 7,070 patients in the New York State Department of Health of Health Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System database who had surgery for UC from 1995 to 2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Abelson and coauthors reported having no financial relationships.

Source: Abelson JS et al. Ann Surg. 2018;268:311-7.

Hip fracture outcomes are the next ERAS improvement goal

ORLANDO – compared with patients treated before the intervention, an investigator reported at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

These patients had a lower pneumonia rate and were more often discharged to home from acute care after the program was implemented, according to Lila Gottenbos, RN, BSN, of Langley (B.C.) Memorial Hospital.

The intervention incorporated some traditional enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) process measures, along with others that were not so traditional, Ms. Gottenbos said. “Implementing ERAS in a fractured hip patient population is possible, and by doing so, more patients go home faster to their previous places of residence with fewer complications.”

A multidisciplinary team at Langley Memorial Hospital, a 200-bed community hospital with approximately 6,000 surgical procedures performed each year, has used ERAS measures in their colorectal patient population since 2013. Those measures have been successful in creating a sustained reduction in morbidity and length of stay, according to Ms. Gottenbos.

The team began searching for other patient populations who might also benefit. They chose to focus on the fractured hip population, which in 2015 had a 9.7% mortality rate, 17% morbidity rate, 5% pneumonia rate, and 19% rate of discharge to home from acute care. “We looked at this data and we realized we had a significant opportunity to do better for our patients,” Ms. Gottenbos told meeting attendees.

The team developed ERAS-based process measures tailored specifically to pre- and postoperative challenges in the fractured hip patient population, Ms. Gottenbos said. Measures included preoperative patient and family education, elimination of prolonged preoperative NPO status, early mobilization, assessment of mentation, and use of standardized order sets. The protocol has been applied to every hip fracture patient who has had surgery from January 2016 to the present. The hospital averages 110 of these procedures per year.

Fractured hip mortality dropped after the modified ERAS process measures were adopted, Ms. Gottenbos reported. Measured to 30 days postoperatively, mortality decreased from 9.7% in 2015 to 4.2% by 2017. Similarly, fractured hip morbidity within 30 days, excluding transfusion, dropped from 17.7% in 2015 to 11.7% in 2017, and fractured hip pneumonia dropped from 5.4% to 2.5%.

Perhaps the most telling evidence of success, according to the presenter, was the increase in the number of patients going home from acute care: “Before ERAS, fractured hip patients were going home to their place of residence less than 20% of the time from the acute care setting, meaning they were languishing in the hospital, in a convalescent unit, in a rehab unit, or worse, residential care,” she said. “We’ve been able to increase that to over 43%.”

The program is ongoing. A multidisciplinary team meets monthly to review outcomes data and devise strategies to improve compliance with the process measures. “It’s an iterative process, and it’s one that’s worked very well for us so far,” Ms. Gottenbos remarked.

The investigator had no disclosures.

ORLANDO – compared with patients treated before the intervention, an investigator reported at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

These patients had a lower pneumonia rate and were more often discharged to home from acute care after the program was implemented, according to Lila Gottenbos, RN, BSN, of Langley (B.C.) Memorial Hospital.

The intervention incorporated some traditional enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) process measures, along with others that were not so traditional, Ms. Gottenbos said. “Implementing ERAS in a fractured hip patient population is possible, and by doing so, more patients go home faster to their previous places of residence with fewer complications.”

A multidisciplinary team at Langley Memorial Hospital, a 200-bed community hospital with approximately 6,000 surgical procedures performed each year, has used ERAS measures in their colorectal patient population since 2013. Those measures have been successful in creating a sustained reduction in morbidity and length of stay, according to Ms. Gottenbos.

The team began searching for other patient populations who might also benefit. They chose to focus on the fractured hip population, which in 2015 had a 9.7% mortality rate, 17% morbidity rate, 5% pneumonia rate, and 19% rate of discharge to home from acute care. “We looked at this data and we realized we had a significant opportunity to do better for our patients,” Ms. Gottenbos told meeting attendees.

The team developed ERAS-based process measures tailored specifically to pre- and postoperative challenges in the fractured hip patient population, Ms. Gottenbos said. Measures included preoperative patient and family education, elimination of prolonged preoperative NPO status, early mobilization, assessment of mentation, and use of standardized order sets. The protocol has been applied to every hip fracture patient who has had surgery from January 2016 to the present. The hospital averages 110 of these procedures per year.

Fractured hip mortality dropped after the modified ERAS process measures were adopted, Ms. Gottenbos reported. Measured to 30 days postoperatively, mortality decreased from 9.7% in 2015 to 4.2% by 2017. Similarly, fractured hip morbidity within 30 days, excluding transfusion, dropped from 17.7% in 2015 to 11.7% in 2017, and fractured hip pneumonia dropped from 5.4% to 2.5%.

Perhaps the most telling evidence of success, according to the presenter, was the increase in the number of patients going home from acute care: “Before ERAS, fractured hip patients were going home to their place of residence less than 20% of the time from the acute care setting, meaning they were languishing in the hospital, in a convalescent unit, in a rehab unit, or worse, residential care,” she said. “We’ve been able to increase that to over 43%.”

The program is ongoing. A multidisciplinary team meets monthly to review outcomes data and devise strategies to improve compliance with the process measures. “It’s an iterative process, and it’s one that’s worked very well for us so far,” Ms. Gottenbos remarked.

The investigator had no disclosures.

ORLANDO – compared with patients treated before the intervention, an investigator reported at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.

These patients had a lower pneumonia rate and were more often discharged to home from acute care after the program was implemented, according to Lila Gottenbos, RN, BSN, of Langley (B.C.) Memorial Hospital.

The intervention incorporated some traditional enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) process measures, along with others that were not so traditional, Ms. Gottenbos said. “Implementing ERAS in a fractured hip patient population is possible, and by doing so, more patients go home faster to their previous places of residence with fewer complications.”

A multidisciplinary team at Langley Memorial Hospital, a 200-bed community hospital with approximately 6,000 surgical procedures performed each year, has used ERAS measures in their colorectal patient population since 2013. Those measures have been successful in creating a sustained reduction in morbidity and length of stay, according to Ms. Gottenbos.

The team began searching for other patient populations who might also benefit. They chose to focus on the fractured hip population, which in 2015 had a 9.7% mortality rate, 17% morbidity rate, 5% pneumonia rate, and 19% rate of discharge to home from acute care. “We looked at this data and we realized we had a significant opportunity to do better for our patients,” Ms. Gottenbos told meeting attendees.

The team developed ERAS-based process measures tailored specifically to pre- and postoperative challenges in the fractured hip patient population, Ms. Gottenbos said. Measures included preoperative patient and family education, elimination of prolonged preoperative NPO status, early mobilization, assessment of mentation, and use of standardized order sets. The protocol has been applied to every hip fracture patient who has had surgery from January 2016 to the present. The hospital averages 110 of these procedures per year.

Fractured hip mortality dropped after the modified ERAS process measures were adopted, Ms. Gottenbos reported. Measured to 30 days postoperatively, mortality decreased from 9.7% in 2015 to 4.2% by 2017. Similarly, fractured hip morbidity within 30 days, excluding transfusion, dropped from 17.7% in 2015 to 11.7% in 2017, and fractured hip pneumonia dropped from 5.4% to 2.5%.

Perhaps the most telling evidence of success, according to the presenter, was the increase in the number of patients going home from acute care: “Before ERAS, fractured hip patients were going home to their place of residence less than 20% of the time from the acute care setting, meaning they were languishing in the hospital, in a convalescent unit, in a rehab unit, or worse, residential care,” she said. “We’ve been able to increase that to over 43%.”

The program is ongoing. A multidisciplinary team meets monthly to review outcomes data and devise strategies to improve compliance with the process measures. “It’s an iterative process, and it’s one that’s worked very well for us so far,” Ms. Gottenbos remarked.

The investigator had no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACSQSC 2018

Key clinical point: Fractured hip patients managed with the ERAS protocol had improved outcomes.

Major finding: After implementation of the ERAS protocol, 43% of fractured hip patients were discharged to home, which is up from 20% before the project.

Study details: More than 200 patients treated for hip fracture during 2016-2017 at the Langley (B.C.) Memorial Hospital.

Disclosures: The investigator had no disclosures. .

Percutaneous drainage upped morbidity risk in hepatobiliary cancer patients

ORLANDO – In patients with was associated with an increased risk of death or serious morbidity versus endoscopic drainage, results of a recent retrospective study show.

Patients undergoing percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage did have more preoperative comorbidities, compared with those undergoing endoscopic biliary stenting, according researcher Q. Lina Hu, MD, an American College of Surgeons Clinical Scholar-in-Residence.

“Nevertheless, compared to endoscopic drainage, percutaneous drainage was associated with a significantly increased morbidity and mortality, even after adjustment for measured confounders,” Dr. Hu said a presentation at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference.