User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Hernia registries need uniform data collection

Hernia registries have proliferated in recent years but would contribute more to the evaluation of treatments and outcomes of hernia repair if the data quality was uniform, according to a study of one U.S.-based and six European registries.

The CORE (Comparison of Hernia Registries in Europe) project was initiated in 2015 by a group of to survey the defining characteristics of each registry and compare their features. Each registry has a unique profile of data collected, basis of participation, and financial support.

“Despite the differences in the way data are collected for each of the listed hernia registries, the data are indispensable in clinical research. As a consequence of the numerous innovations in hernia surgery (surgical procedures, meshes, fixation devices), hardly any other area of surgical study has such a high need for clinical trials and data collection, comparison and analysis. Registries play a vital role in this innovation process,” the CORE investigators wrote.

The project collected information about the Danish Hernia Database (DHDB, the Netherlands), Swedish Hernia Registry (SHR), Herniamed (Germany, Switzerland, Austria), EuraHS (Belgium), Club Hernie (CH, France), EVEREG (Spain) and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative (AHSQC, the United States). Representatives of each registry provided details of the size of database, the types of cases contained in the registry, the terms of participation, operative data collected, and registry sponsors.

The DHDB and the SHR have the longest histories (created 1992 and 1998, respectively) and contain the largest number of cases (more than 200,000). The SHR has data from more than 95% of all national inguinal cases, and about 15% of ventral and parastomal cases). The DHDB covers 90% of all inguinal cases and 80% of all ventral and other types of hernia. These two registries are publicly funded, nonprofit institutions.

The other registries are of more recent origin (2007-2015), cover a lower percentage of the hernia cases in each country, but nonetheless have accumulated a large number of cases (for example, Herniamed has data on more than 290,000 inguinal cases and almost 200,000 ventral and other types of hernias). These registries are industry funded and participation by surgical centers is voluntary.

These seven registry differ primarily in the kinds of data they collect. The DHDB collects far less data than do the others on complications and, in particular, no data on mesh complications or pain. And although each of the other registries covers a long list of complications, the lists are far from identical, according to the CORE project investigators.

Follow-up protocol also varies considerably among the registries. The CORE investigators note that the “limitation of all data analysis from registries is always selection and input bias,” and the potential of combining the data from all of the registries into one database could only be accomplished if the uniform quality and consistency in data collection were assured.

The CORE project was initiated with registry representatives and each was were responsible for the information about their registry. Conflicts are reported for each contributor on the Hernia website.

SOURCE: Kyle-Leinhase I et al. Hernia 2018;22(4):561-75.

Hernia registries have proliferated in recent years but would contribute more to the evaluation of treatments and outcomes of hernia repair if the data quality was uniform, according to a study of one U.S.-based and six European registries.

The CORE (Comparison of Hernia Registries in Europe) project was initiated in 2015 by a group of to survey the defining characteristics of each registry and compare their features. Each registry has a unique profile of data collected, basis of participation, and financial support.

“Despite the differences in the way data are collected for each of the listed hernia registries, the data are indispensable in clinical research. As a consequence of the numerous innovations in hernia surgery (surgical procedures, meshes, fixation devices), hardly any other area of surgical study has such a high need for clinical trials and data collection, comparison and analysis. Registries play a vital role in this innovation process,” the CORE investigators wrote.

The project collected information about the Danish Hernia Database (DHDB, the Netherlands), Swedish Hernia Registry (SHR), Herniamed (Germany, Switzerland, Austria), EuraHS (Belgium), Club Hernie (CH, France), EVEREG (Spain) and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative (AHSQC, the United States). Representatives of each registry provided details of the size of database, the types of cases contained in the registry, the terms of participation, operative data collected, and registry sponsors.

The DHDB and the SHR have the longest histories (created 1992 and 1998, respectively) and contain the largest number of cases (more than 200,000). The SHR has data from more than 95% of all national inguinal cases, and about 15% of ventral and parastomal cases). The DHDB covers 90% of all inguinal cases and 80% of all ventral and other types of hernia. These two registries are publicly funded, nonprofit institutions.

The other registries are of more recent origin (2007-2015), cover a lower percentage of the hernia cases in each country, but nonetheless have accumulated a large number of cases (for example, Herniamed has data on more than 290,000 inguinal cases and almost 200,000 ventral and other types of hernias). These registries are industry funded and participation by surgical centers is voluntary.

These seven registry differ primarily in the kinds of data they collect. The DHDB collects far less data than do the others on complications and, in particular, no data on mesh complications or pain. And although each of the other registries covers a long list of complications, the lists are far from identical, according to the CORE project investigators.

Follow-up protocol also varies considerably among the registries. The CORE investigators note that the “limitation of all data analysis from registries is always selection and input bias,” and the potential of combining the data from all of the registries into one database could only be accomplished if the uniform quality and consistency in data collection were assured.

The CORE project was initiated with registry representatives and each was were responsible for the information about their registry. Conflicts are reported for each contributor on the Hernia website.

SOURCE: Kyle-Leinhase I et al. Hernia 2018;22(4):561-75.

Hernia registries have proliferated in recent years but would contribute more to the evaluation of treatments and outcomes of hernia repair if the data quality was uniform, according to a study of one U.S.-based and six European registries.

The CORE (Comparison of Hernia Registries in Europe) project was initiated in 2015 by a group of to survey the defining characteristics of each registry and compare their features. Each registry has a unique profile of data collected, basis of participation, and financial support.

“Despite the differences in the way data are collected for each of the listed hernia registries, the data are indispensable in clinical research. As a consequence of the numerous innovations in hernia surgery (surgical procedures, meshes, fixation devices), hardly any other area of surgical study has such a high need for clinical trials and data collection, comparison and analysis. Registries play a vital role in this innovation process,” the CORE investigators wrote.

The project collected information about the Danish Hernia Database (DHDB, the Netherlands), Swedish Hernia Registry (SHR), Herniamed (Germany, Switzerland, Austria), EuraHS (Belgium), Club Hernie (CH, France), EVEREG (Spain) and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative (AHSQC, the United States). Representatives of each registry provided details of the size of database, the types of cases contained in the registry, the terms of participation, operative data collected, and registry sponsors.

The DHDB and the SHR have the longest histories (created 1992 and 1998, respectively) and contain the largest number of cases (more than 200,000). The SHR has data from more than 95% of all national inguinal cases, and about 15% of ventral and parastomal cases). The DHDB covers 90% of all inguinal cases and 80% of all ventral and other types of hernia. These two registries are publicly funded, nonprofit institutions.

The other registries are of more recent origin (2007-2015), cover a lower percentage of the hernia cases in each country, but nonetheless have accumulated a large number of cases (for example, Herniamed has data on more than 290,000 inguinal cases and almost 200,000 ventral and other types of hernias). These registries are industry funded and participation by surgical centers is voluntary.

These seven registry differ primarily in the kinds of data they collect. The DHDB collects far less data than do the others on complications and, in particular, no data on mesh complications or pain. And although each of the other registries covers a long list of complications, the lists are far from identical, according to the CORE project investigators.

Follow-up protocol also varies considerably among the registries. The CORE investigators note that the “limitation of all data analysis from registries is always selection and input bias,” and the potential of combining the data from all of the registries into one database could only be accomplished if the uniform quality and consistency in data collection were assured.

The CORE project was initiated with registry representatives and each was were responsible for the information about their registry. Conflicts are reported for each contributor on the Hernia website.

SOURCE: Kyle-Leinhase I et al. Hernia 2018;22(4):561-75.

FROM HERNIA

Little overlap between surgical M&M and AHRQ on adverse events

Limited overlap in adverse events identified by surgical morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators (PSIs) demonstrates that the two processes tend to capture different, but equally important, measures, according to study results published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Just 18 of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes in a retrospective, observational study of complications at the UC Davis Medical Center’s department of surgery. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, while 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs, reported Jamie E. Anderson, MD, MPH, of the department of surgery at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento and coauthors.

The study authors identified 6,563 surgical hospitalizations in the year 2016, of which 647 (9.9%) had at least one event that was either submitted for review for a departmental M&M conference, identified as a PSI event from administrative data, or both. Cases in patients aged less than 18 years were excluded.

Hospital administrative data were reported using ICD-10 CM/PCS codes. Investigators identified all PSI cases, which included pressure ulcer, retained surgical item, iatrogenic pneumothorax, central venous catheter–related blood stream infection, postoperative hip fracture, perioperative hematoma or hemorrhage requiring a procedure, postoperative acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, postoperative respiratory failure, perioperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis, postoperative sepsis, postoperative wound dehiscence, and unrecognized abdominopelvic accidental puncture or laceration.

Complications submitted to the M&M conference were reviewed for PSI-defined events, and included events from general surgery, bariatric surgery, burn, cardiothoracic, colorectal, surgical oncology, plastic, vascular, transplant, and trauma. PSI-defined events were then reviewed to verify whether they counted as “true” PSI events and further classified as a documentation error, intentional exclusion, or inherent limitation of the PSI, the authors reported.

Of 6,563 surgical hospitalizations, 647 had at least one complication identified by M&M, PSI, or both. Of these, 116 had at least one PSI-defined event identified by either M&M or PSI. The remaining hospitalizations had unrelated complications and were excluded from analysis.

Of the 116 hospitalizations, there were 149 PSI-defined events, of which 18 (12.1%) were identified by both methods. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, and 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs. Perioperative hemorrhage/hematoma and postoperative sepsis were most likely to be identified by both.

Of the 93 PSI-defined events captured by only M&M, 11 (11.8%) met AHRQ criteria and were considered “true” events, or “false negatives.” All 38 events identified by PSI alone were correctly identified as true PSI events, Dr. Anderson and colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that the AHRQ PSI and surgical M&M conference “should be considered complementary approaches for identifying complications,” the authors wrote.

The PSI data captured central venous catheter–related blood stream infection and pressure ulcers, but the M&M conferences did not include these outcomes. The M&M reviewed more cases of postoperative sepsis, abdominopelvic accidental laceration, and the one case of retained surgical item.

“These two processes of identifying complications have different purposes, and each approach captured different events,” they added.

The M&M conference “balances clinician education and quality improvement with an underlying theme of accountability,” they said, with increased emphasis on examining adverse events in the context of systems-based practices. PSI, on the other hand, is intended as a “resource-nonintensive means” to help hospitals identify preventable events and facilitate quality improvement, they said.

“In an era in which there are numerous mechanisms to measure surgical quality, the traditional M&M conference is still relevant for identifying and discussing surgical complications,” the authors concluded. “We believe that our center’s existing M&M case-finding process is fundamentally sound, but it could be improved by including all PSI-flagged hospitalizations in our M&M process. This may result in review of some false-positive records, but it will enable our department to address certain potentially preventable complications that are currently overlooked.”

Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

Limited overlap in adverse events identified by surgical morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators (PSIs) demonstrates that the two processes tend to capture different, but equally important, measures, according to study results published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Just 18 of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes in a retrospective, observational study of complications at the UC Davis Medical Center’s department of surgery. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, while 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs, reported Jamie E. Anderson, MD, MPH, of the department of surgery at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento and coauthors.

The study authors identified 6,563 surgical hospitalizations in the year 2016, of which 647 (9.9%) had at least one event that was either submitted for review for a departmental M&M conference, identified as a PSI event from administrative data, or both. Cases in patients aged less than 18 years were excluded.

Hospital administrative data were reported using ICD-10 CM/PCS codes. Investigators identified all PSI cases, which included pressure ulcer, retained surgical item, iatrogenic pneumothorax, central venous catheter–related blood stream infection, postoperative hip fracture, perioperative hematoma or hemorrhage requiring a procedure, postoperative acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, postoperative respiratory failure, perioperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis, postoperative sepsis, postoperative wound dehiscence, and unrecognized abdominopelvic accidental puncture or laceration.

Complications submitted to the M&M conference were reviewed for PSI-defined events, and included events from general surgery, bariatric surgery, burn, cardiothoracic, colorectal, surgical oncology, plastic, vascular, transplant, and trauma. PSI-defined events were then reviewed to verify whether they counted as “true” PSI events and further classified as a documentation error, intentional exclusion, or inherent limitation of the PSI, the authors reported.

Of 6,563 surgical hospitalizations, 647 had at least one complication identified by M&M, PSI, or both. Of these, 116 had at least one PSI-defined event identified by either M&M or PSI. The remaining hospitalizations had unrelated complications and were excluded from analysis.

Of the 116 hospitalizations, there were 149 PSI-defined events, of which 18 (12.1%) were identified by both methods. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, and 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs. Perioperative hemorrhage/hematoma and postoperative sepsis were most likely to be identified by both.

Of the 93 PSI-defined events captured by only M&M, 11 (11.8%) met AHRQ criteria and were considered “true” events, or “false negatives.” All 38 events identified by PSI alone were correctly identified as true PSI events, Dr. Anderson and colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that the AHRQ PSI and surgical M&M conference “should be considered complementary approaches for identifying complications,” the authors wrote.

The PSI data captured central venous catheter–related blood stream infection and pressure ulcers, but the M&M conferences did not include these outcomes. The M&M reviewed more cases of postoperative sepsis, abdominopelvic accidental laceration, and the one case of retained surgical item.

“These two processes of identifying complications have different purposes, and each approach captured different events,” they added.

The M&M conference “balances clinician education and quality improvement with an underlying theme of accountability,” they said, with increased emphasis on examining adverse events in the context of systems-based practices. PSI, on the other hand, is intended as a “resource-nonintensive means” to help hospitals identify preventable events and facilitate quality improvement, they said.

“In an era in which there are numerous mechanisms to measure surgical quality, the traditional M&M conference is still relevant for identifying and discussing surgical complications,” the authors concluded. “We believe that our center’s existing M&M case-finding process is fundamentally sound, but it could be improved by including all PSI-flagged hospitalizations in our M&M process. This may result in review of some false-positive records, but it will enable our department to address certain potentially preventable complications that are currently overlooked.”

Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

Limited overlap in adverse events identified by surgical morbidity and mortality (M&M) conferences and by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality patient safety indicators (PSIs) demonstrates that the two processes tend to capture different, but equally important, measures, according to study results published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Just 18 of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes in a retrospective, observational study of complications at the UC Davis Medical Center’s department of surgery. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, while 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs, reported Jamie E. Anderson, MD, MPH, of the department of surgery at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento and coauthors.

The study authors identified 6,563 surgical hospitalizations in the year 2016, of which 647 (9.9%) had at least one event that was either submitted for review for a departmental M&M conference, identified as a PSI event from administrative data, or both. Cases in patients aged less than 18 years were excluded.

Hospital administrative data were reported using ICD-10 CM/PCS codes. Investigators identified all PSI cases, which included pressure ulcer, retained surgical item, iatrogenic pneumothorax, central venous catheter–related blood stream infection, postoperative hip fracture, perioperative hematoma or hemorrhage requiring a procedure, postoperative acute kidney injury requiring dialysis, postoperative respiratory failure, perioperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis, postoperative sepsis, postoperative wound dehiscence, and unrecognized abdominopelvic accidental puncture or laceration.

Complications submitted to the M&M conference were reviewed for PSI-defined events, and included events from general surgery, bariatric surgery, burn, cardiothoracic, colorectal, surgical oncology, plastic, vascular, transplant, and trauma. PSI-defined events were then reviewed to verify whether they counted as “true” PSI events and further classified as a documentation error, intentional exclusion, or inherent limitation of the PSI, the authors reported.

Of 6,563 surgical hospitalizations, 647 had at least one complication identified by M&M, PSI, or both. Of these, 116 had at least one PSI-defined event identified by either M&M or PSI. The remaining hospitalizations had unrelated complications and were excluded from analysis.

Of the 116 hospitalizations, there were 149 PSI-defined events, of which 18 (12.1%) were identified by both methods. Most events (62.4%) were identified by only the M&M review, and 25.5% were identified by only the PSIs. Perioperative hemorrhage/hematoma and postoperative sepsis were most likely to be identified by both.

Of the 93 PSI-defined events captured by only M&M, 11 (11.8%) met AHRQ criteria and were considered “true” events, or “false negatives.” All 38 events identified by PSI alone were correctly identified as true PSI events, Dr. Anderson and colleagues reported.

The findings indicate that the AHRQ PSI and surgical M&M conference “should be considered complementary approaches for identifying complications,” the authors wrote.

The PSI data captured central venous catheter–related blood stream infection and pressure ulcers, but the M&M conferences did not include these outcomes. The M&M reviewed more cases of postoperative sepsis, abdominopelvic accidental laceration, and the one case of retained surgical item.

“These two processes of identifying complications have different purposes, and each approach captured different events,” they added.

The M&M conference “balances clinician education and quality improvement with an underlying theme of accountability,” they said, with increased emphasis on examining adverse events in the context of systems-based practices. PSI, on the other hand, is intended as a “resource-nonintensive means” to help hospitals identify preventable events and facilitate quality improvement, they said.

“In an era in which there are numerous mechanisms to measure surgical quality, the traditional M&M conference is still relevant for identifying and discussing surgical complications,” the authors concluded. “We believe that our center’s existing M&M case-finding process is fundamentally sound, but it could be improved by including all PSI-flagged hospitalizations in our M&M process. This may result in review of some false-positive records, but it will enable our department to address certain potentially preventable complications that are currently overlooked.”

Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Surgical morbidity and mortality conferences and AHRQ patient safety indicators should be considered complementary measures of adverse events because of a limited overlap in identifying adverse events.

Major finding: Eighteen of 149 (12.1%) PSI-defined events were identified by both processes; most (62.4%) were identified by only M&M review, and 25.5% by only PSI.

Study details: A retrospective observational study of all complications in 2016 at the UC Davis Medical Center department of surgery.

Disclosures: Two of the study coauthors received salary support from the AHRQ to support the agency’s Quality Indicator Program, one of whom serves on the agency’s Quality Indicators Expert Workgroup. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Anderson J et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Jul 5. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.008.

Fewer groin infections with closed incision negative pressure therapy after vascular surgery

Closed incision negative pressure therapy (ciNPT) was found to reduce surgical site infections (SSI) in vascular surgery, according to the results of a prospective, randomized, industry-sponsored trial of patients who underwent vascular surgery for peripheral artery disease (PAD) published online in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery.

The investigator-initiated Reduction of Groin Wound Infections After Vascular Surgery by Using an Incision Management System trial (NCT02395159) included 204 patients who underwent vascular surgery involving longitudinal groin incision to treat the lower extremity or the iliac arteries between July 2015 and May 2017 at two study centers.

The primary endpoint was the occurrence of SSI assessed by the Szilagyi classification (grades I-III). The mean patient age was nearly 67 years and 70% were men. In terms of PAD staging, 52% were stage 2B, 28% were stage 3, and 19% were stage 4. Among the patients, 45% had a previous groin incision and 42% had diabetes.

All patients underwent similar preoperative treatment: hair shaving and preparation with Poly Alcohol (Antiseptica, Pulheim, Germany) and Braunoderm (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). At 30 minutes preincision, patients received intravenous antibiotic treatment (1.5 g cefuroxime or 600 mg clindamycin, if allergic to penicillin). After closure, the incision and surrounding skin area was cleaned and dried using sterile gauze. In the control group, a sterile adhesive wound dressing was applied to the wound, which was changed daily. In the treatment group, ciNPT was applied under sterile conditions in the operating room using the Prevena device, which exerts a continuous negative pressure of 125 mm Hg on the closed incision during the time of application. The device was removed at 5-7 days postoperatively, and no further wound dressings were used in the treatment group unless an SSI occurred.

The control group experienced more frequent SSIs (33.3%) than the intervention group (13.2%) (P =.0015). This difference was based on an increased rate of Szilagyi grade I SSI in the control group (24.6% vs. 8.1%, P = .0012), according to Alexander Gombert, MD, of the University Hospital Aachen (Germany), and his colleagues. The absolute risk difference based on the Szilagyi classification was –20.1 per 100 (95% confidence interval, –31.9 to –8.2).

In addition, there was a statistically significantly lower rate of SSI when using ciNPT within the subgroups at greater risk of infection, compared with controls: PAD stage greater than or equal to 3 (P less than .001), body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 (P less than .001), and previous groin incision (P = .016).

There were no statistical differences between the two groups in Szilagyi grade II and III SSIs (which occurred in 5.8% of all procedures).

No potentially device-related complications were observed in the trial and there were no failures of the device seen.

“The use of ciNPT rather than standard wound dressing after groin incision as access for vascular surgery was associated with a reduced rate of superficial SSI classified by Szilagyi, suggesting that ciNPT may be useful for reducing the SSI rate among high-risk patients,” the researchers concluded.

The trial was funded by Acelity. Dr. Gombert received travel grants from Acelity.

SOURCE: Gombert A et al. Eur J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.018.

Closed incision negative pressure therapy (ciNPT) was found to reduce surgical site infections (SSI) in vascular surgery, according to the results of a prospective, randomized, industry-sponsored trial of patients who underwent vascular surgery for peripheral artery disease (PAD) published online in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery.

The investigator-initiated Reduction of Groin Wound Infections After Vascular Surgery by Using an Incision Management System trial (NCT02395159) included 204 patients who underwent vascular surgery involving longitudinal groin incision to treat the lower extremity or the iliac arteries between July 2015 and May 2017 at two study centers.

The primary endpoint was the occurrence of SSI assessed by the Szilagyi classification (grades I-III). The mean patient age was nearly 67 years and 70% were men. In terms of PAD staging, 52% were stage 2B, 28% were stage 3, and 19% were stage 4. Among the patients, 45% had a previous groin incision and 42% had diabetes.

All patients underwent similar preoperative treatment: hair shaving and preparation with Poly Alcohol (Antiseptica, Pulheim, Germany) and Braunoderm (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). At 30 minutes preincision, patients received intravenous antibiotic treatment (1.5 g cefuroxime or 600 mg clindamycin, if allergic to penicillin). After closure, the incision and surrounding skin area was cleaned and dried using sterile gauze. In the control group, a sterile adhesive wound dressing was applied to the wound, which was changed daily. In the treatment group, ciNPT was applied under sterile conditions in the operating room using the Prevena device, which exerts a continuous negative pressure of 125 mm Hg on the closed incision during the time of application. The device was removed at 5-7 days postoperatively, and no further wound dressings were used in the treatment group unless an SSI occurred.

The control group experienced more frequent SSIs (33.3%) than the intervention group (13.2%) (P =.0015). This difference was based on an increased rate of Szilagyi grade I SSI in the control group (24.6% vs. 8.1%, P = .0012), according to Alexander Gombert, MD, of the University Hospital Aachen (Germany), and his colleagues. The absolute risk difference based on the Szilagyi classification was –20.1 per 100 (95% confidence interval, –31.9 to –8.2).

In addition, there was a statistically significantly lower rate of SSI when using ciNPT within the subgroups at greater risk of infection, compared with controls: PAD stage greater than or equal to 3 (P less than .001), body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 (P less than .001), and previous groin incision (P = .016).

There were no statistical differences between the two groups in Szilagyi grade II and III SSIs (which occurred in 5.8% of all procedures).

No potentially device-related complications were observed in the trial and there were no failures of the device seen.

“The use of ciNPT rather than standard wound dressing after groin incision as access for vascular surgery was associated with a reduced rate of superficial SSI classified by Szilagyi, suggesting that ciNPT may be useful for reducing the SSI rate among high-risk patients,” the researchers concluded.

The trial was funded by Acelity. Dr. Gombert received travel grants from Acelity.

SOURCE: Gombert A et al. Eur J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.018.

Closed incision negative pressure therapy (ciNPT) was found to reduce surgical site infections (SSI) in vascular surgery, according to the results of a prospective, randomized, industry-sponsored trial of patients who underwent vascular surgery for peripheral artery disease (PAD) published online in the European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery.

The investigator-initiated Reduction of Groin Wound Infections After Vascular Surgery by Using an Incision Management System trial (NCT02395159) included 204 patients who underwent vascular surgery involving longitudinal groin incision to treat the lower extremity or the iliac arteries between July 2015 and May 2017 at two study centers.

The primary endpoint was the occurrence of SSI assessed by the Szilagyi classification (grades I-III). The mean patient age was nearly 67 years and 70% were men. In terms of PAD staging, 52% were stage 2B, 28% were stage 3, and 19% were stage 4. Among the patients, 45% had a previous groin incision and 42% had diabetes.

All patients underwent similar preoperative treatment: hair shaving and preparation with Poly Alcohol (Antiseptica, Pulheim, Germany) and Braunoderm (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). At 30 minutes preincision, patients received intravenous antibiotic treatment (1.5 g cefuroxime or 600 mg clindamycin, if allergic to penicillin). After closure, the incision and surrounding skin area was cleaned and dried using sterile gauze. In the control group, a sterile adhesive wound dressing was applied to the wound, which was changed daily. In the treatment group, ciNPT was applied under sterile conditions in the operating room using the Prevena device, which exerts a continuous negative pressure of 125 mm Hg on the closed incision during the time of application. The device was removed at 5-7 days postoperatively, and no further wound dressings were used in the treatment group unless an SSI occurred.

The control group experienced more frequent SSIs (33.3%) than the intervention group (13.2%) (P =.0015). This difference was based on an increased rate of Szilagyi grade I SSI in the control group (24.6% vs. 8.1%, P = .0012), according to Alexander Gombert, MD, of the University Hospital Aachen (Germany), and his colleagues. The absolute risk difference based on the Szilagyi classification was –20.1 per 100 (95% confidence interval, –31.9 to –8.2).

In addition, there was a statistically significantly lower rate of SSI when using ciNPT within the subgroups at greater risk of infection, compared with controls: PAD stage greater than or equal to 3 (P less than .001), body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 (P less than .001), and previous groin incision (P = .016).

There were no statistical differences between the two groups in Szilagyi grade II and III SSIs (which occurred in 5.8% of all procedures).

No potentially device-related complications were observed in the trial and there were no failures of the device seen.

“The use of ciNPT rather than standard wound dressing after groin incision as access for vascular surgery was associated with a reduced rate of superficial SSI classified by Szilagyi, suggesting that ciNPT may be useful for reducing the SSI rate among high-risk patients,” the researchers concluded.

The trial was funded by Acelity. Dr. Gombert received travel grants from Acelity.

SOURCE: Gombert A et al. Eur J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.018.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF VASCULAR AND ENDOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Closed incision negative pressure therapy lessened the incidence of groin infection after vascular surgery.

Major finding: The control group experienced more frequent surgical site infections (33.3%) than the intervention group (13.2%) (P =.0015).

Study details: A randomized, controlled trial of 204 patients with peripheral artery disease who underwent vascular surgery.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by Acelity. Dr. Gombert received travel grants from Acelity.

Source: Gombert A et al. Eur J Vasc Surg. 2018 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.05.018.

Earnings gap seen among Maryland physicians

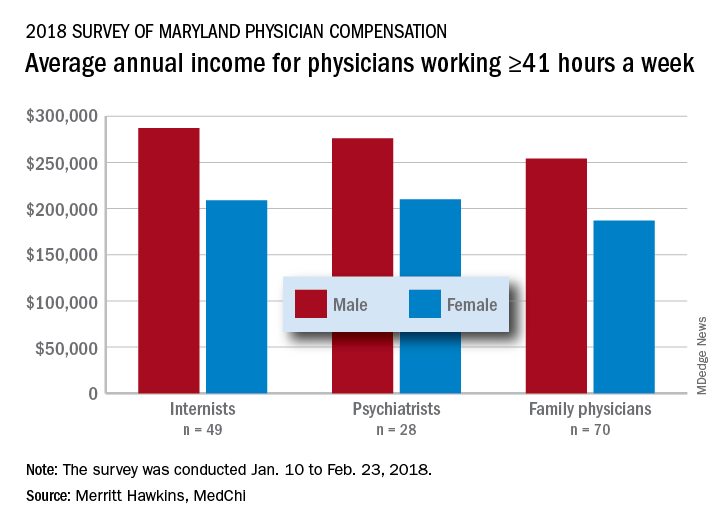

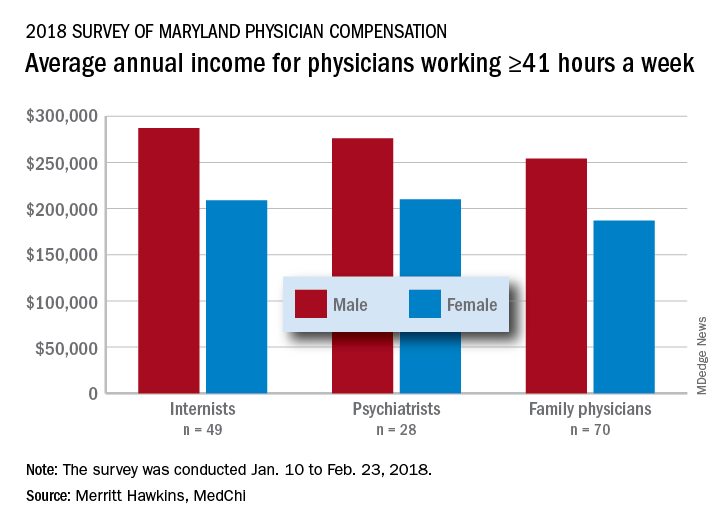

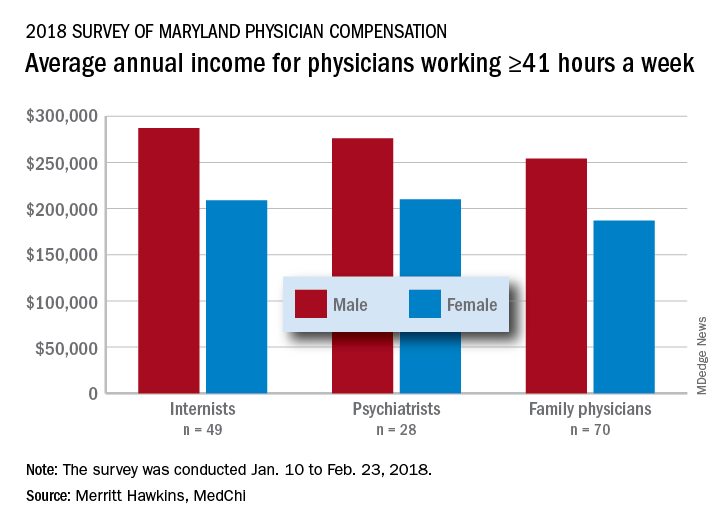

Male physicians in Maryland reported higher earnings than did female physicians, even when they all worked 41 or more hours a week, according to a 2018 survey of physicians in the state.

The average pretax income for all 508 respondents was $299,000 in 2016: Male physicians (66.6% of the sample) had an average of $335,000 and women averaged 33% lower at $224,000, MedChi (the Maryland State Medical Society) and Merritt Hawkins reported on July 31. Men did report working a longer week: Their average of 50.5 hours was 11% more than the 45.4-hour average for women.

“The biggest disparities we see in compensation are between male and female physicians in Maryland,” Gene Ransom, MedChi’s chief executive officer, said in a written statement. “Though such disparities have been noted in other research, it is still surprising to see the extent to which they persist.”

Of the respondents who worked an average of 41 or more hours per week – an analysis conducted only for the three largest specialties in the survey – female internists earned 27% less than their male counterparts, female psychiatrists earned 24% less, and female family physicians earned 26% less, the survey results showed.

Earnings were structured somewhat differently for Maryland’s male and female physicians. Women were more likely to be compensated in the form of a straight salary than men (35.0% vs. 30.3%), and men were more likely to paid based on production (22.7% vs. 16.9%) or in the form of an income guarantee (0.9% vs. 0.0%). Proportions receiving a salary with a production bonus were 42.7% for men and 42.5% for women, according to the survey.

The survey was commissioned by MedChi and conducted by Merritt Hawkins from Jan. 10 to Feb. 23, 2018. The margin of error was plus or minus 4.4%.

Male physicians in Maryland reported higher earnings than did female physicians, even when they all worked 41 or more hours a week, according to a 2018 survey of physicians in the state.

The average pretax income for all 508 respondents was $299,000 in 2016: Male physicians (66.6% of the sample) had an average of $335,000 and women averaged 33% lower at $224,000, MedChi (the Maryland State Medical Society) and Merritt Hawkins reported on July 31. Men did report working a longer week: Their average of 50.5 hours was 11% more than the 45.4-hour average for women.

“The biggest disparities we see in compensation are between male and female physicians in Maryland,” Gene Ransom, MedChi’s chief executive officer, said in a written statement. “Though such disparities have been noted in other research, it is still surprising to see the extent to which they persist.”

Of the respondents who worked an average of 41 or more hours per week – an analysis conducted only for the three largest specialties in the survey – female internists earned 27% less than their male counterparts, female psychiatrists earned 24% less, and female family physicians earned 26% less, the survey results showed.

Earnings were structured somewhat differently for Maryland’s male and female physicians. Women were more likely to be compensated in the form of a straight salary than men (35.0% vs. 30.3%), and men were more likely to paid based on production (22.7% vs. 16.9%) or in the form of an income guarantee (0.9% vs. 0.0%). Proportions receiving a salary with a production bonus were 42.7% for men and 42.5% for women, according to the survey.

The survey was commissioned by MedChi and conducted by Merritt Hawkins from Jan. 10 to Feb. 23, 2018. The margin of error was plus or minus 4.4%.

Male physicians in Maryland reported higher earnings than did female physicians, even when they all worked 41 or more hours a week, according to a 2018 survey of physicians in the state.

The average pretax income for all 508 respondents was $299,000 in 2016: Male physicians (66.6% of the sample) had an average of $335,000 and women averaged 33% lower at $224,000, MedChi (the Maryland State Medical Society) and Merritt Hawkins reported on July 31. Men did report working a longer week: Their average of 50.5 hours was 11% more than the 45.4-hour average for women.

“The biggest disparities we see in compensation are between male and female physicians in Maryland,” Gene Ransom, MedChi’s chief executive officer, said in a written statement. “Though such disparities have been noted in other research, it is still surprising to see the extent to which they persist.”

Of the respondents who worked an average of 41 or more hours per week – an analysis conducted only for the three largest specialties in the survey – female internists earned 27% less than their male counterparts, female psychiatrists earned 24% less, and female family physicians earned 26% less, the survey results showed.

Earnings were structured somewhat differently for Maryland’s male and female physicians. Women were more likely to be compensated in the form of a straight salary than men (35.0% vs. 30.3%), and men were more likely to paid based on production (22.7% vs. 16.9%) or in the form of an income guarantee (0.9% vs. 0.0%). Proportions receiving a salary with a production bonus were 42.7% for men and 42.5% for women, according to the survey.

The survey was commissioned by MedChi and conducted by Merritt Hawkins from Jan. 10 to Feb. 23, 2018. The margin of error was plus or minus 4.4%.

Feds take baseline on EHR interoperability

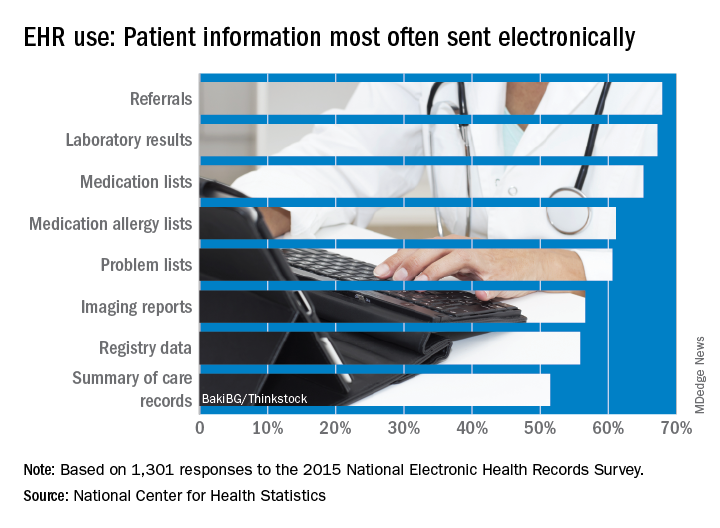

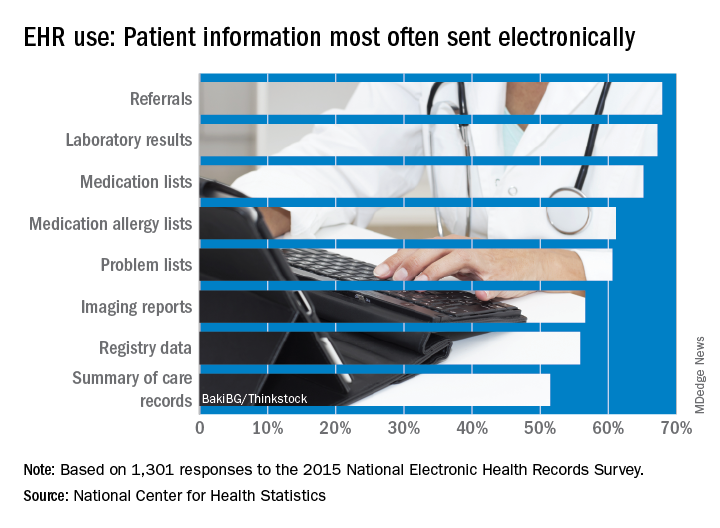

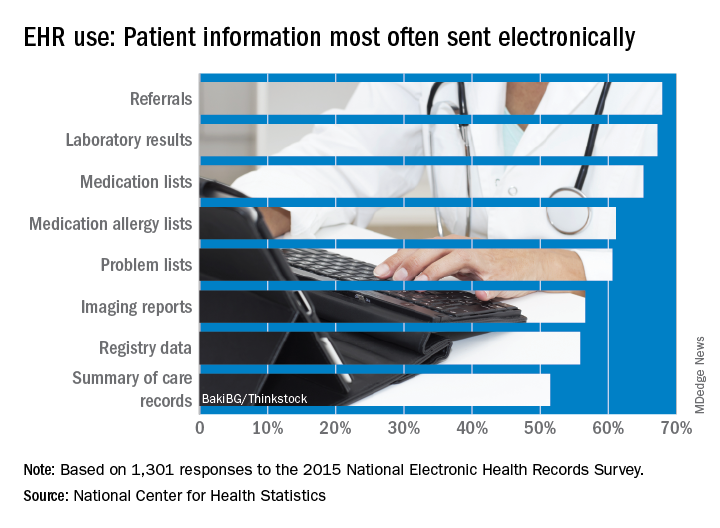

Office-based physicians who have electronic health records are most likely to send patient health information (PHI) in the form of referrals and laboratory results and receive it as lab results and imaging reports, according to national estimates of electronic PHI using four aspects of interoperability.

Those aspects of sharing PHI are sending, receiving, integrating, and searching. With federal estimates of EHR adoption at 78% for office-based physicians, data from the 2015 National Electronic Health Records Just over 65% are sending medication lists electronically, 61% are sending medication allergy lists, and almost 61% are sending problem lists, Ninee S. Yang, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in National Health Statistics Reports.

Communication in the other direction showed a somewhat different distribution. Of the 1,525 physicians who reported receiving PHI electronically, 79% were the recipients of laboratory results, with imaging reports well behind at 61%, followed by medication lists and referrals at 54% and summary of care records at 52%, the investigators reported.

The ability to integrate information into an EHR – reported by 959 survey respondents – is another key element of interoperability, and 73% of those physicians said that they could integrate lab results into their systems. Other types of PHI, however, did not fare as well: imaging reports came in at 50%, hospital discharge summaries at 49%, summary of care records at 41%, and emergency department notifications at 40%, Dr. Yang and her associates said.

The fourth aspect of interoperability, ability to search for PHI from sources outside the practice, was reported by 1,335 respondents in 2015, with 90% looking for medication lists, 88% for medication allergy lists, 80% for hospital discharge summaries, 59% for imaging reports, and 49% for lab results, they said.

These first national estimates of PHI type will be used as baseline data “in tracking progress outlined in the federal plan for achieving interoperability” among physicians with EHR systems, Dr. Yang and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: Yang NS et al. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018 Aug 15;(115):1-9.

Office-based physicians who have electronic health records are most likely to send patient health information (PHI) in the form of referrals and laboratory results and receive it as lab results and imaging reports, according to national estimates of electronic PHI using four aspects of interoperability.

Those aspects of sharing PHI are sending, receiving, integrating, and searching. With federal estimates of EHR adoption at 78% for office-based physicians, data from the 2015 National Electronic Health Records Just over 65% are sending medication lists electronically, 61% are sending medication allergy lists, and almost 61% are sending problem lists, Ninee S. Yang, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in National Health Statistics Reports.

Communication in the other direction showed a somewhat different distribution. Of the 1,525 physicians who reported receiving PHI electronically, 79% were the recipients of laboratory results, with imaging reports well behind at 61%, followed by medication lists and referrals at 54% and summary of care records at 52%, the investigators reported.

The ability to integrate information into an EHR – reported by 959 survey respondents – is another key element of interoperability, and 73% of those physicians said that they could integrate lab results into their systems. Other types of PHI, however, did not fare as well: imaging reports came in at 50%, hospital discharge summaries at 49%, summary of care records at 41%, and emergency department notifications at 40%, Dr. Yang and her associates said.

The fourth aspect of interoperability, ability to search for PHI from sources outside the practice, was reported by 1,335 respondents in 2015, with 90% looking for medication lists, 88% for medication allergy lists, 80% for hospital discharge summaries, 59% for imaging reports, and 49% for lab results, they said.

These first national estimates of PHI type will be used as baseline data “in tracking progress outlined in the federal plan for achieving interoperability” among physicians with EHR systems, Dr. Yang and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: Yang NS et al. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018 Aug 15;(115):1-9.

Office-based physicians who have electronic health records are most likely to send patient health information (PHI) in the form of referrals and laboratory results and receive it as lab results and imaging reports, according to national estimates of electronic PHI using four aspects of interoperability.

Those aspects of sharing PHI are sending, receiving, integrating, and searching. With federal estimates of EHR adoption at 78% for office-based physicians, data from the 2015 National Electronic Health Records Just over 65% are sending medication lists electronically, 61% are sending medication allergy lists, and almost 61% are sending problem lists, Ninee S. Yang, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in National Health Statistics Reports.

Communication in the other direction showed a somewhat different distribution. Of the 1,525 physicians who reported receiving PHI electronically, 79% were the recipients of laboratory results, with imaging reports well behind at 61%, followed by medication lists and referrals at 54% and summary of care records at 52%, the investigators reported.

The ability to integrate information into an EHR – reported by 959 survey respondents – is another key element of interoperability, and 73% of those physicians said that they could integrate lab results into their systems. Other types of PHI, however, did not fare as well: imaging reports came in at 50%, hospital discharge summaries at 49%, summary of care records at 41%, and emergency department notifications at 40%, Dr. Yang and her associates said.

The fourth aspect of interoperability, ability to search for PHI from sources outside the practice, was reported by 1,335 respondents in 2015, with 90% looking for medication lists, 88% for medication allergy lists, 80% for hospital discharge summaries, 59% for imaging reports, and 49% for lab results, they said.

These first national estimates of PHI type will be used as baseline data “in tracking progress outlined in the federal plan for achieving interoperability” among physicians with EHR systems, Dr. Yang and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: Yang NS et al. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018 Aug 15;(115):1-9.

FROM NATIONAL HEALTH STATISTICS REPORTS

5 HIPAA myths in the digital age

The nexus of new technology and privacy rules springing from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) leads to a lot of stress and trepidation for health care professionals. Lucia Savage, chief privacy and regulatory officer for Omada Health, and Matthew Fisher, a health law attorney based in Worcester, Mass., who specializes in compliance issues, dispel common HIPAA myths and offer advice on how to protect yourself and your practice.

Truth: Physicians are not responsible for email security flaws from patient servers, said Ms. Savage, who served as chief privacy officer for the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama. HIPAA requires only that health providers send emails from a secure system that protects a doctor’s message from their end, she said.

“There’s this myth out there that you cannot send an electronic message to a patient’s email box if that email is unsecured, and that’s not true,” Ms. Savage said at a recent American Bar Association meeting. “The obligation is to secure what you send, not to secure what an unregulated, private person receives.”

Just remember to warn patients that they’re responsible for the safe storage of an email message once it arrives.

Truth: An email with protected health information (PHI) accidentally sent to the wrong health provider is not likely to get doctors in trouble with the Office for Civil Rights. In the last 12 years, there have been 184,000 HIPAA-related complaints to OCR and only 55 resulted in financial settlements, according to research Ms. Savage conducted through the Department of Health & Human Services website. Of the 55 settlements, none were associated with PHI accidentally sent from one health provider to another, she said in an interview.

“[The OCR] tends to seek fines for really eye-poppingly bad behavior,” Ms. Savage said, not small-scale accidents. For example, OCR fined one hospital for including the name of a patient in a press release without patient permission. Another health professional was fined for repeated failures to encrypt their computer system.

If a document with PHI does end up in the wrong inbox, Ms. Savage advises calling the receiver and asking that they immediately delete the email.

Truth: Breaches alone are not the reason most fines are levied, nor do breach notifications mean an instant penalty, Mr. Fisher said in an interview. Fines by OCR are more often tied to further noncompliance found when the agency begins investigating the entity after the breach report.

“Most breach reports will result in OCR conducting a follow-up investigation, usually with paper-based requests,” he said. “If responses to those requests reveal widespread or consistent noncompliance, then OCR may latch on and dig in order to impose a fine.”

For example, a breach could be the result of a lost USB drive or laptop, but OCR’s investigation might ultimately find that the practice failed to conduct an adequate risk analysis. Because a risk analysis is a fundamental component of HIPAA compliance, the inadequate risk analysis becomes the basis for a fine, Mr. Fisher said.

The best way to avoid an OCR fine is to ensure that proper HIPAA protocols are in place to assess security risks, prevent breaches, and mitigate breaches should they occur. “Part of good compliance is constant review and revision of policies as well,” Mr. Fisher said. “It is not sufficient to put the policies into place and then never revisit those policies. Circumstances change all of the time and policies need to keep up.”

Truth: Health professionals are obligated to provide copies of health information to patients and that includes electronic copies if practices have such technology. The electronic copy requirement was adopted in 2009 as part of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act.

Despite the electronic amendment’s existence for nearly 10 years, Ms. Savage said she frequently hears from patients about the difficulty of obtaining health information and the extended time and high cost that come with requests.

“[Providing health information to patients] is an obligation,” Ms. Savage stressed. “A 21st century physician might want to be thinking about how to build on that obligation to really engage their patients in a partnership of care. If you give the patient the data, they can actually become a more valuable [participant] with you and engage in self-management.”

More information on HITECH and giving patients access to protected health information can be found here.

Truth: HIPAA is flexible and can adapt to newer technology more easily than many people think, Mr. Fisher says.

“[There is the perception] that HIPAA is archaic and does not fit with modern technology,” he said. “There are a lot of misplaced fears that digital tools cannot satisfy security requirements or will place data where they should not go.”

In actuality, many health care applications enable doctors to satisfy HIPAA requirements, while using updated technology. Secure email to send patients messages is one example, he said, as well as secure text messaging between providers.

At the same time, new technology can often assist health care privacy and advance security, Mr. Fisher noted. Technology solutions frequently automate routine tasks, such as auditing. Tools like machine learning and artificial intelligence can enhance security and catch up with attacker intelligence, he added.

“Technology should be viewed as a means of enhancing and expanding capabilities,” he said. “Using the auditing example, an individual really cannot adequately review all records or access points, but a program may be able to do so and begin to identify small trends that represent a security concern. From this perspective, the technology, as indicated, is about enhancing what can be done.”

The nexus of new technology and privacy rules springing from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) leads to a lot of stress and trepidation for health care professionals. Lucia Savage, chief privacy and regulatory officer for Omada Health, and Matthew Fisher, a health law attorney based in Worcester, Mass., who specializes in compliance issues, dispel common HIPAA myths and offer advice on how to protect yourself and your practice.

Truth: Physicians are not responsible for email security flaws from patient servers, said Ms. Savage, who served as chief privacy officer for the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama. HIPAA requires only that health providers send emails from a secure system that protects a doctor’s message from their end, she said.

“There’s this myth out there that you cannot send an electronic message to a patient’s email box if that email is unsecured, and that’s not true,” Ms. Savage said at a recent American Bar Association meeting. “The obligation is to secure what you send, not to secure what an unregulated, private person receives.”

Just remember to warn patients that they’re responsible for the safe storage of an email message once it arrives.

Truth: An email with protected health information (PHI) accidentally sent to the wrong health provider is not likely to get doctors in trouble with the Office for Civil Rights. In the last 12 years, there have been 184,000 HIPAA-related complaints to OCR and only 55 resulted in financial settlements, according to research Ms. Savage conducted through the Department of Health & Human Services website. Of the 55 settlements, none were associated with PHI accidentally sent from one health provider to another, she said in an interview.

“[The OCR] tends to seek fines for really eye-poppingly bad behavior,” Ms. Savage said, not small-scale accidents. For example, OCR fined one hospital for including the name of a patient in a press release without patient permission. Another health professional was fined for repeated failures to encrypt their computer system.

If a document with PHI does end up in the wrong inbox, Ms. Savage advises calling the receiver and asking that they immediately delete the email.

Truth: Breaches alone are not the reason most fines are levied, nor do breach notifications mean an instant penalty, Mr. Fisher said in an interview. Fines by OCR are more often tied to further noncompliance found when the agency begins investigating the entity after the breach report.

“Most breach reports will result in OCR conducting a follow-up investigation, usually with paper-based requests,” he said. “If responses to those requests reveal widespread or consistent noncompliance, then OCR may latch on and dig in order to impose a fine.”

For example, a breach could be the result of a lost USB drive or laptop, but OCR’s investigation might ultimately find that the practice failed to conduct an adequate risk analysis. Because a risk analysis is a fundamental component of HIPAA compliance, the inadequate risk analysis becomes the basis for a fine, Mr. Fisher said.

The best way to avoid an OCR fine is to ensure that proper HIPAA protocols are in place to assess security risks, prevent breaches, and mitigate breaches should they occur. “Part of good compliance is constant review and revision of policies as well,” Mr. Fisher said. “It is not sufficient to put the policies into place and then never revisit those policies. Circumstances change all of the time and policies need to keep up.”

Truth: Health professionals are obligated to provide copies of health information to patients and that includes electronic copies if practices have such technology. The electronic copy requirement was adopted in 2009 as part of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act.

Despite the electronic amendment’s existence for nearly 10 years, Ms. Savage said she frequently hears from patients about the difficulty of obtaining health information and the extended time and high cost that come with requests.

“[Providing health information to patients] is an obligation,” Ms. Savage stressed. “A 21st century physician might want to be thinking about how to build on that obligation to really engage their patients in a partnership of care. If you give the patient the data, they can actually become a more valuable [participant] with you and engage in self-management.”

More information on HITECH and giving patients access to protected health information can be found here.

Truth: HIPAA is flexible and can adapt to newer technology more easily than many people think, Mr. Fisher says.

“[There is the perception] that HIPAA is archaic and does not fit with modern technology,” he said. “There are a lot of misplaced fears that digital tools cannot satisfy security requirements or will place data where they should not go.”

In actuality, many health care applications enable doctors to satisfy HIPAA requirements, while using updated technology. Secure email to send patients messages is one example, he said, as well as secure text messaging between providers.

At the same time, new technology can often assist health care privacy and advance security, Mr. Fisher noted. Technology solutions frequently automate routine tasks, such as auditing. Tools like machine learning and artificial intelligence can enhance security and catch up with attacker intelligence, he added.

“Technology should be viewed as a means of enhancing and expanding capabilities,” he said. “Using the auditing example, an individual really cannot adequately review all records or access points, but a program may be able to do so and begin to identify small trends that represent a security concern. From this perspective, the technology, as indicated, is about enhancing what can be done.”

The nexus of new technology and privacy rules springing from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) leads to a lot of stress and trepidation for health care professionals. Lucia Savage, chief privacy and regulatory officer for Omada Health, and Matthew Fisher, a health law attorney based in Worcester, Mass., who specializes in compliance issues, dispel common HIPAA myths and offer advice on how to protect yourself and your practice.

Truth: Physicians are not responsible for email security flaws from patient servers, said Ms. Savage, who served as chief privacy officer for the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT under President Obama. HIPAA requires only that health providers send emails from a secure system that protects a doctor’s message from their end, she said.

“There’s this myth out there that you cannot send an electronic message to a patient’s email box if that email is unsecured, and that’s not true,” Ms. Savage said at a recent American Bar Association meeting. “The obligation is to secure what you send, not to secure what an unregulated, private person receives.”

Just remember to warn patients that they’re responsible for the safe storage of an email message once it arrives.

Truth: An email with protected health information (PHI) accidentally sent to the wrong health provider is not likely to get doctors in trouble with the Office for Civil Rights. In the last 12 years, there have been 184,000 HIPAA-related complaints to OCR and only 55 resulted in financial settlements, according to research Ms. Savage conducted through the Department of Health & Human Services website. Of the 55 settlements, none were associated with PHI accidentally sent from one health provider to another, she said in an interview.

“[The OCR] tends to seek fines for really eye-poppingly bad behavior,” Ms. Savage said, not small-scale accidents. For example, OCR fined one hospital for including the name of a patient in a press release without patient permission. Another health professional was fined for repeated failures to encrypt their computer system.

If a document with PHI does end up in the wrong inbox, Ms. Savage advises calling the receiver and asking that they immediately delete the email.

Truth: Breaches alone are not the reason most fines are levied, nor do breach notifications mean an instant penalty, Mr. Fisher said in an interview. Fines by OCR are more often tied to further noncompliance found when the agency begins investigating the entity after the breach report.

“Most breach reports will result in OCR conducting a follow-up investigation, usually with paper-based requests,” he said. “If responses to those requests reveal widespread or consistent noncompliance, then OCR may latch on and dig in order to impose a fine.”

For example, a breach could be the result of a lost USB drive or laptop, but OCR’s investigation might ultimately find that the practice failed to conduct an adequate risk analysis. Because a risk analysis is a fundamental component of HIPAA compliance, the inadequate risk analysis becomes the basis for a fine, Mr. Fisher said.

The best way to avoid an OCR fine is to ensure that proper HIPAA protocols are in place to assess security risks, prevent breaches, and mitigate breaches should they occur. “Part of good compliance is constant review and revision of policies as well,” Mr. Fisher said. “It is not sufficient to put the policies into place and then never revisit those policies. Circumstances change all of the time and policies need to keep up.”

Truth: Health professionals are obligated to provide copies of health information to patients and that includes electronic copies if practices have such technology. The electronic copy requirement was adopted in 2009 as part of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act.

Despite the electronic amendment’s existence for nearly 10 years, Ms. Savage said she frequently hears from patients about the difficulty of obtaining health information and the extended time and high cost that come with requests.

“[Providing health information to patients] is an obligation,” Ms. Savage stressed. “A 21st century physician might want to be thinking about how to build on that obligation to really engage their patients in a partnership of care. If you give the patient the data, they can actually become a more valuable [participant] with you and engage in self-management.”

More information on HITECH and giving patients access to protected health information can be found here.

Truth: HIPAA is flexible and can adapt to newer technology more easily than many people think, Mr. Fisher says.

“[There is the perception] that HIPAA is archaic and does not fit with modern technology,” he said. “There are a lot of misplaced fears that digital tools cannot satisfy security requirements or will place data where they should not go.”

In actuality, many health care applications enable doctors to satisfy HIPAA requirements, while using updated technology. Secure email to send patients messages is one example, he said, as well as secure text messaging between providers.

At the same time, new technology can often assist health care privacy and advance security, Mr. Fisher noted. Technology solutions frequently automate routine tasks, such as auditing. Tools like machine learning and artificial intelligence can enhance security and catch up with attacker intelligence, he added.

“Technology should be viewed as a means of enhancing and expanding capabilities,” he said. “Using the auditing example, an individual really cannot adequately review all records or access points, but a program may be able to do so and begin to identify small trends that represent a security concern. From this perspective, the technology, as indicated, is about enhancing what can be done.”

Open AAA and peripheral bypass surgery patients among the highest users of post-acute care

in Medicare spending, according to the findings of a study that used data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the Veterans Affairs health system (VA) regarding surgical patients.

PAC, including skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation, accounts for 73% of regional variation in Medicare spending, and studies on hospital variation in this area have typically focused on nonsurgical patients or been limited to Medicare data. However, a high degree of variation also appears to hold for surgical patients, according to the authors of this large database study of more than 4 million patients who had aortic aneurysm repair, peripheral vascular bypass, colorectal surgery, hepatectomy, pancreatectomy, or coronary bypass.

“We found that there is significant variation in use of PAC and rates of home discharge following complex cardiac, abdominal, and vascular surgery,” Courtney J. Balentine, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his colleagues wrote in their report in the Journal of Surgical Research.

To explore hospital variation in post-surgery PAC, they evaluated 3,487,365 patients from the NIS (39% were aged 70 years or older, and 60% were men) and 60,666 from the VA (32% were aged 70 years or older, and 98% were men) who had surgery during 2008-2011.

Within the NIS, 631,199 patients (18%) were discharged to PAC facilities, and among the 60,666 veterans, 4744 (7.8%) were discharged to PAC facilities. In addition, hospital rates of discharge to PAC facilities varied from 1% to 36% for VA hospitals and from 1% to 59% for non-VA hospitals, according to the researchers. They found that some VA hospitals were four times more likely to discharge patients to PAC facilities than would be expected from their patients’ characteristics, while others were 90% more likely to send patients home than would be expected, according to Dr. Balentine and his colleagues.

Procedure-specific rates of discharge to PAC facilities from VA hospitals ranged from 2% following endovascular aneurysm repair to 10% after pancreatectomy and peripheral vascular bypass. Among the NIS hospitals, in contrast, rates of discharge to PAC facilities ranged from 6% following hepatectomy to as high as 44% following open aneurysm repair.

“These data could be used to characterize practices that promote more effective recovery from surgery and minimize the need for PAC,” the authors wrote. “Given that skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation cost [$5,000]-$24,000 more than treatment at home, even minor reductions in the need for PAC facilities could result in substantial cost savings,” they stated.

“Our findings suggest that there is considerable room for improvement in the use of PAC after surgery and that we still have a long way to go in terms of using PAC to help patients recover and regain their independence,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Balentine CJ et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Oct;230:61-70.

in Medicare spending, according to the findings of a study that used data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the Veterans Affairs health system (VA) regarding surgical patients.

PAC, including skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation, accounts for 73% of regional variation in Medicare spending, and studies on hospital variation in this area have typically focused on nonsurgical patients or been limited to Medicare data. However, a high degree of variation also appears to hold for surgical patients, according to the authors of this large database study of more than 4 million patients who had aortic aneurysm repair, peripheral vascular bypass, colorectal surgery, hepatectomy, pancreatectomy, or coronary bypass.

“We found that there is significant variation in use of PAC and rates of home discharge following complex cardiac, abdominal, and vascular surgery,” Courtney J. Balentine, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his colleagues wrote in their report in the Journal of Surgical Research.

To explore hospital variation in post-surgery PAC, they evaluated 3,487,365 patients from the NIS (39% were aged 70 years or older, and 60% were men) and 60,666 from the VA (32% were aged 70 years or older, and 98% were men) who had surgery during 2008-2011.

Within the NIS, 631,199 patients (18%) were discharged to PAC facilities, and among the 60,666 veterans, 4744 (7.8%) were discharged to PAC facilities. In addition, hospital rates of discharge to PAC facilities varied from 1% to 36% for VA hospitals and from 1% to 59% for non-VA hospitals, according to the researchers. They found that some VA hospitals were four times more likely to discharge patients to PAC facilities than would be expected from their patients’ characteristics, while others were 90% more likely to send patients home than would be expected, according to Dr. Balentine and his colleagues.

Procedure-specific rates of discharge to PAC facilities from VA hospitals ranged from 2% following endovascular aneurysm repair to 10% after pancreatectomy and peripheral vascular bypass. Among the NIS hospitals, in contrast, rates of discharge to PAC facilities ranged from 6% following hepatectomy to as high as 44% following open aneurysm repair.

“These data could be used to characterize practices that promote more effective recovery from surgery and minimize the need for PAC,” the authors wrote. “Given that skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation cost [$5,000]-$24,000 more than treatment at home, even minor reductions in the need for PAC facilities could result in substantial cost savings,” they stated.

“Our findings suggest that there is considerable room for improvement in the use of PAC after surgery and that we still have a long way to go in terms of using PAC to help patients recover and regain their independence,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Balentine CJ et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Oct;230:61-70.

in Medicare spending, according to the findings of a study that used data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the Veterans Affairs health system (VA) regarding surgical patients.

PAC, including skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation, accounts for 73% of regional variation in Medicare spending, and studies on hospital variation in this area have typically focused on nonsurgical patients or been limited to Medicare data. However, a high degree of variation also appears to hold for surgical patients, according to the authors of this large database study of more than 4 million patients who had aortic aneurysm repair, peripheral vascular bypass, colorectal surgery, hepatectomy, pancreatectomy, or coronary bypass.

“We found that there is significant variation in use of PAC and rates of home discharge following complex cardiac, abdominal, and vascular surgery,” Courtney J. Balentine, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his colleagues wrote in their report in the Journal of Surgical Research.

To explore hospital variation in post-surgery PAC, they evaluated 3,487,365 patients from the NIS (39% were aged 70 years or older, and 60% were men) and 60,666 from the VA (32% were aged 70 years or older, and 98% were men) who had surgery during 2008-2011.

Within the NIS, 631,199 patients (18%) were discharged to PAC facilities, and among the 60,666 veterans, 4744 (7.8%) were discharged to PAC facilities. In addition, hospital rates of discharge to PAC facilities varied from 1% to 36% for VA hospitals and from 1% to 59% for non-VA hospitals, according to the researchers. They found that some VA hospitals were four times more likely to discharge patients to PAC facilities than would be expected from their patients’ characteristics, while others were 90% more likely to send patients home than would be expected, according to Dr. Balentine and his colleagues.

Procedure-specific rates of discharge to PAC facilities from VA hospitals ranged from 2% following endovascular aneurysm repair to 10% after pancreatectomy and peripheral vascular bypass. Among the NIS hospitals, in contrast, rates of discharge to PAC facilities ranged from 6% following hepatectomy to as high as 44% following open aneurysm repair.

“These data could be used to characterize practices that promote more effective recovery from surgery and minimize the need for PAC,” the authors wrote. “Given that skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation cost [$5,000]-$24,000 more than treatment at home, even minor reductions in the need for PAC facilities could result in substantial cost savings,” they stated.

“Our findings suggest that there is considerable room for improvement in the use of PAC after surgery and that we still have a long way to go in terms of using PAC to help patients recover and regain their independence,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Balentine CJ et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Oct;230:61-70.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point: The wide disparity among hospitals in their rates of postsurgery discharge to post-acute care (PAC) could be an area of focus for cost containment in Medicare spending.

Major finding: Rates of discharge to PAC facilities varied from 1% to 36% for VA hospitals and from 1% to 59% for non-VA hospitals.

Study details: A database analysis of 3,487,365 National Inpatient Sample patients and 60,666 VA patients who had surgery during 2008-2011.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Balentine CJ et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Oct;230:61-70.

Vascular training for general surgery residents continues downward trend

Operative experience in open arterial vascular surgery procedures for general surgery residents has significantly declined, according to the results of a study of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) national case log reports, which lists the mean numbers of operations performed.

“Because fundamental vascular surgery skills are necessary for operative general surgery, vascular surgery should remain an essential content area. However, programs cannot solely depend on operative experience to teach fundamental vascular surgery skills,” John R. Potts III, MD, FACS, and R. James Valentine, MD, FACS, stated in their report published online in Annals of Surgery.

The number of individuals completing ACGME-accredited general surgery and vascular surgery training each year of the study was obtained from public reports of the ACGME as well as the available summary national data regarding the reported operative experience of residents completing general surgery programs.

The researchers found that over 15 years (academic year 2001-2002 through AY 2016-2017), the total vascular operations performed by general surgery residents significantly declined as did the total open arterial vascular procedures, including those in seven of nine categories (P less than .0001).

The issue of adequate exposure to vascular procedures for general surgery residents is complex. “The number of individuals completing general surgery residency annually has increased by approximately 20% since AY 2001-2. During the same period, the number of open arterial operations reported by general surgery residents decreased by approximately 38%. Thus, the declining experience is clearly not simply a matter of distributing the same number of operations to a larger number of individuals,” the investigators reported.