User login

The American Journal of Orthopedics is an Index Medicus publication that is valued by orthopedic surgeons for its peer-reviewed, practice-oriented clinical information. Most articles are written by specialists at leading teaching institutions and help incorporate the latest technology into everyday practice.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction: Current Philosophy in 2016

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the primary restraint to valgus stress between 20° and 125° of motion.1-5 Overhead athletes, most commonly baseball pitchers, are at risk of developing UCL insufficiency, and dysfunction presents as pain with loss of velocity and control. Some injuries may present acutely while throwing, but many patients, when questioned, report a preceding period of either pain or loss of velocity and control.

Authors have documented a significant rise in elbow injuries in young athletes, especially pitchers.6 Extended seasons, higher pitch counts, year-round pitching, pitching while fatigued, and pitching for multiple teams are risk factors for elbow injuries.7 Pitchers in the southern United States are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction than those from the northern states.8 Pitchers who also play catcher are at a higher risk due to more total throws than those who pitch and play other positions or pitch only. Throwers with higher velocity are more likely to pitch in showcases, pitch for multiple teams, and pitch with pain and fatigue, and these are all risk factors.6 Also, in one study of youth baseball injuries, individuals in the injured group were found to be taller and heavier than those in the uninjured group.6 Pitch counts, rest from pitching during the off-season, adequate rest, and ensuring pain-free pitching can lessen the risk of injury.6 As expected with the rise in throwing injuries, the rise in medial elbow procedures has risen.9

While throwing, stress across the medial elbow has been measured to be nearly 300 N. A maximum varus force during pitching was measured to be 64 N-m at 95° ± 14°.10 Morrey and An4 determined that the UCL generated 54% of the varus force at 90° of flexion. During active pitching, this value is likely reduced due to simultaneous muscle contraction, but if one assumes the UCL bears 54% of the maximal load, the UCL must be able to withstand 34 N-m. The UCL can withstand a maximum valgus torque between 22.7 and 34 N-m11-13; therefore, during pitching, the UCL is at or above its failure load. After thousands of cycles over many years, one can imagine how the UCL might be injured.

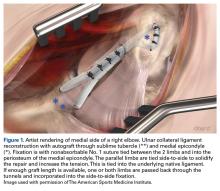

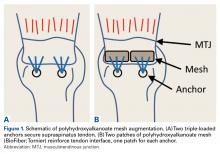

Multiple techniques have been proposed in the surgical treatment of UCL injuries. Jobe14 pioneered UCL reconstruction in 1974 in Tommy John, a Major League Baseball pitcher. John returned to pitch successfully, and both the UCL and the reconstruction are commonly called by his name. Jobe14 reported his technique in 1986, and it has remained, with a few modifications, the primary method for reconstruction of the UCL (Figure 1).

Evaluation

A standard evaluation with physical examination and imaging is completed in all throwers with elbow pain. In our prior study,16 we found that 100% of patients experienced pain during athletic activity and that 96% of throwers complained of pain during late cocking and acceleration phases of the throwing motion. Nearly half reported an acute onset of pain, while 53% were unable to identify a single inciting event. Seventy-five percent of the acute injuries were during competition. Delayed diagnosis was very common, with an average time to diagnosis after onset of symptoms of 6.4 months. Neurologic symptoms were seen in 23% of athletes, most of which were ulnar nerve paresthesias during throwing.16

Physical examination includes inspection for swelling, hand intrinsic atrophy, neurovascular examination, range of motion, shoulder examination, and elbow stress examination. Range of motion at presentation averaged 5° to 135° with 85° of supination and pronation.16 All patients need neurologic evaluation for ulnar nerve dysfunction. Tinel test of the cubital tunnel was positive in 21%.16 Significant ulnar nerve dysfunction, including hand weakness, is much less common but must be well examined and documented. The shoulder must also be evaluated for loss of rotation, which can lead to increased stress on the elbow. An evaluation of mechanics may point out flaws in technique, which may be contributing to elbow stress. The UCL stress examination includes static stress at 30° of flexion, the milking test at 90°, and the moving valgus stress test. The presence of pain directly over the UCL or laxity compared to the uninvolved side is suggestive of UCL injury.

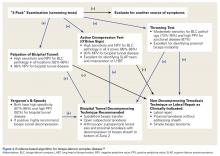

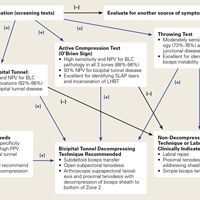

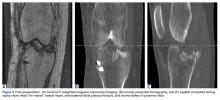

Radiographic evaluation is completed in all patients with concern for UCL injury. Standard x-rays of the elbow, including anteroposterior, medial, and lateral obliques, axial olecranon, and lateral views, are obtained to evaluate bony abnormalities. Fifty-seven percent of our series showed some abnormality, most commonly olecranon osteophyte formation or ectopic calcification within the UCL substance. Stress radiography rarely changed the treatment course and is somewhat difficult to interpret because of the reports documenting normal increased medial elbow opening in the dominant arm of throwing athletes.21 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is obtained very commonly in this patient population, and intra-articular contrast is crucial. Partial, undersurface tears are common, and a contrasted study better demonstrates undersurface tears or avulsions. The T-sign as described by Timmerman and colleagues22 using computed tomography (CT) arthrography shows partial undersurface detachment, which can be difficult to see without intra-articular contrast.22 This finding is very well visualized on MRI arthrogram as well (Figure 3).

Nonoperative Management

Nonoperative treatment is recommended for 3 months prior to performing reconstruction. Patients are given complete rest from throwing, but rehabilitation is initiated immediately. Rehabilitation exercises and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are prescribed, and activities that place valgus stress across the elbow are avoided. After resolution of symptoms, an interval throwing program is initiated, and the athlete is gradually returned to sport. Unfortunately, due to season-specific schedules and time-sensitive demands in high-level throwers, operative treatment is often chosen without an extended period of conservative treatment.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has recently been shown to improve healing rates and promote healing in partial UCL tears,23 and as orthobiologics are advanced, they will likely play a larger role in the treatment of UCL injuries.

Surgical Technique

At our institution, UCL reconstruction is performed with the modified Jobe technique as described by Azar and colleagues.17 Arthroscopy prior to reconstruction was routinely performed at our institution until we recognized that arthroscopy rarely changed the preoperative plan.16 Currently, the presence of anterior pathology such as loose bodies or osteochondral defect is our only indication for arthroscopy before reconstruction.

Ipsilateral palmaris autograft is our current graft of choice. This must be examined preoperatively because 16% of patients have unilateral absence and 9% have bilateral absence.24 In revision cases or in patients with insufficient or absent palmaris, contralateral palmaris followed by contralateral gracilis tendon is used. The contralateral gracilis is chosen because of ease of setup and position of the surgeon during the harvest. Gracilis tendon is also used in cases with bony involvement of the ligament based on the results from Dugas and colleagues.25 Toe extensors, plantaris, and patellar tendon grafts have also been used. One recent study showed that neither graft choice nor diameter affected resistance to valgus stress, and that all reconstruction types restored strength at 60° to 120° of flexion.26

Ulnar nerve transposition is performed in all cases regardless of the presence of preoperative nerve symptoms. A complete decompression is completed proximally to the Arcade of Struthers and distally to the deep portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris. A single fascial sling of medial intermuscular septum originating from the epicondylar attachment is used to stabilize the nerve without compression. At wound closure, the deep fascia on the posterior skin flap is also sewn into the cubital tunnel to prevent the nerve from subluxating back into the groove. A single suture is placed distally closing the muscle fascia to prevent propagation of the fascial incision, which can lead to herniation. Transposition is necessary because of the ulnar nerve exposure required in the modified Jobe technique to allow elevation of the deep flexor muscle mass for ligament exposure.

The reconstruction is completed as described by Jobe14 but with a few modifications as described by Azar and colleagues17 and slight adaptations implemented since that time. The flexor-pronator mass is retracted laterally instead of detachment or splitting as described by Thompson and colleagues.27 A subcutaneous rather than a submuscular ulnar nerve transposition is used.

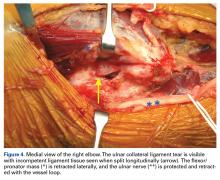

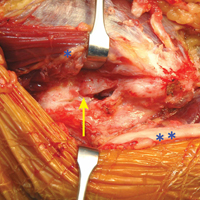

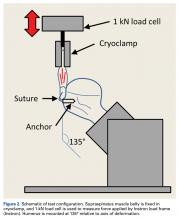

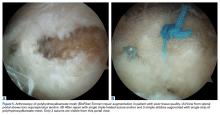

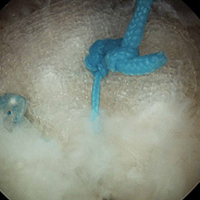

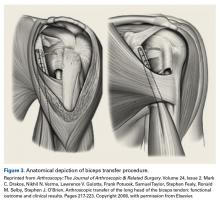

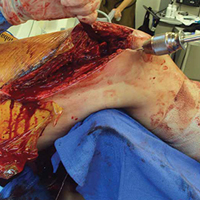

The patient is positioned supine using an arm board. If gracilis tendon is chosen, the contralateral leg is prepped and draped simultaneously. A tourniquet is inflated after exsanguination. A medial approach is performed, and the medial antebrachial nerve is located and protected. The ulnar nerve is then located in the cubital tunnel and mobilized. The neurolysis extends to the deep portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris distally and proximally to the Arcade of Struthers, and the nerve is retracted with a vessel loop. The flexor muscle mass is not elevated from the medial epicondyle; rather, it is retracted anteriorly by small Hohmann retractors. The dissection is carried down to the UCL and found at its attachments to the medial epicondyle and sublime tubercle. If no tear is seen on the superficial surface of the ligament, a longitudinal incision is made through the ligament. Undersurface tears, partial tears, and avulsions can then be identified (Figure 4).

The autologous graft of choice is then harvested. Our technique for palmaris harvest is performed with three 1-cm transverse incisions. The palmaris is palpated and marked with the first incision made near the distal wrist crease, and the second incision is made 3 to 4 cm proximal to the first. The tendon is found in both distal incisions and cut distally with the wrist flexed to maximize tendon length. The tendon is then pulled through the second incision and tensioned to identify the most proximal location the tendon can be palpated. A third incision is made directly over this point and carried down to cut the tendon. This usually provides a graft length of 15 to 20 cm; 13 cm is the minimum graft length to ensure good graft fixation. Muscle is removed from the tendon and each end is secured with a No. 1 nonabsorbable suture in a locking fashion.

If posterior osteophytes are present, they are removed through a posterior, vertical arthrotomy. Over-resection of the olecranon must be avoided, as this can further destabilize the elbow and place increased stress on the reconstruction. Posterior loose bodies can also be removed through this arthrotomy. The arthrotomy is then closed with absorbable suture.

Tunnel placement is critical to success. A 3.2-mm drill bit is used with palmaris grafts and a 4-mm drill bit is used with gracilis grafts. Two convergent tunnels are drilled in the medial epicondyle in a Y fashion and 2 convergent tunnels are drilled at the sublime tubercle in a U or V fashion. After drilling the first tunnel on each side, a hemostat is placed in the tunnel as an aiming point to ensure a complete tunnel is made. The junction is smoothed with a curette, leaving a 5-mm bone bridge between the articular surface and the tunnels. A bent Hewson suture passer is used to pass one end of the graft through the ulna. The 2 limbs of the tendon graft are then passed through the humeral tunnels, creating a figure-of-eight. A varus stress is applied with the elbow at roughly 30° and the 2 limbs are tied together with a No. 1 nonabsorbable suture. If enough graft remains, one or both limbs are passed back through the tunnels and secured again with No. 1 nonabsorbable suture. The 2 limbs are then tied side-to-side, incorporating the native ligament to further secure and tighten the reconstruction.

The ulnar nerve is then secured using a strip of medial intermuscular septum left intact to its insertion at the medial epicondyle. This is attached to the flexor-pronator muscle fascia with a 3-0 nonabsorbable suture. Enough length should be harvested from the septum to ensure there is no compression on the nerve. The deep posterior fascial tissue is then sewn to the periosteum of the medial epicondyle to further prevent subluxation of the nerve back into the groove. The skin is then closed in layered fashion over a superficial drain. The patient is placed in a well-padded posterior splint for 1 week, then the rehabilitation protocol is initiated as discussed below.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

A standardized postoperative 4-phase rehabilitation program for ulnar collateral reconstruction is followed as described by Wilk and colleagues.28-30 The first phase begins immediately after surgery and continues for 4 weeks. During surgery, the patient’s elbow is placed in a compression dressing with a posterior splint to immobilize the elbow in 90° of flexion with wrist motion for 1 week to allow initial healing. Full range of motion of the elbow joint is restored by the end of the fifth to sixth week after surgery.

During phase II (weeks 4-10), a progressive isotonic strengthening program is initiated. Exercises are focused on scapular, rotator cuff, deltoid, and arm musculature. Shoulder range of motion and stretching exercises are performed during this phase and the Thrower’s Ten exercise program is initiated. Any adaptations or strength deficits are addressed during this phase.

During the advanced strengthening phase (phase III), from weeks 10 to 16, a sport-specific exercise/rehabilitation program is initiated. During this phase, stretching and flexibility exercises are performed to enhance strength, power, and endurance. During this phase the patient is placed on the advanced Thrower’s Ten program. Isotonic strengthening exercises are progressed, and at week 12, the athlete is allowed to begin an isotonic lifting program, including bench press, seated rowing, latissimus dorsi pull downs, triceps push downs, and biceps curls. In addition, the athlete performs specific exercises to emphasize sport-specific movements. At week 12, overhead athletes begin a 2-hand plyometric throwing program, and at 14 weeks, a 1

Discussion

Results after ulnar collateral reconstruction have been good. In our series of 743 patients, 83% returned to the same or higher level at an average of 11.6 months.16 There was a 4% major complication rate and 16% minor complication rate. Major complications included medial epicondyle fracture (0.5%), significant ulnar nerve dysfunction (1 patient), rupture of graft (1%), and graft site infection. Sixteen percent of patients had ulnar nerve dysfunction, and 82% of these resolved within 6 weeks. All but 1 patient’s paresthesias resolved within 1 year.16 The 10-year follow-up of this group of patients included 256 patients and was reported by Osbahr and colleagues31 in 2014. Retirement from baseball was due to reasons other than the elbow in 86%, and 98% were still able to throw on at least a recreational level. The overall longevity was 3.6 years, with 2.9 years at pre-injury level or higher. Statistically, pitchers performed at a higher level after reconstruction.31

A recent review by Erickson and colleagues9 showed an overall 82% excellent and 8% good result when evaluating different techniques, including the American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) modification of Jobe’s technique, docking technique, and Jobe’s technique. With an overall complication rate of 10% (75% of which was transient ulnar neuritis), the procedure was deemed overall a safe surgical option. Collegiate athletes had the highest return to sport (95%) compared with high school athletes (89%) and professional athletes (86%). The docking technique had the highest rate of return to play (97%) compared with ASMI technique (93%) and Jobe technique (66%).9 Results after repair have not been as good as reconstruction, as reported in 2 studies.16,32 Savoie and colleagues,15 however, reported 93% good/excellent results after primary UCL repair alone.

Another recent review of outcomes showed an overall return to same or higher level was best with docking or modified docking techniques (90.4% and 91.3%, respectively).19 Overall return with modified Jobe technique was 77%.19 O’Brien and colleagues20 performed a review of 33 patients with either modified Jobe or docking technique that showed 81% return to same or higher level with modified Jobe vs 92% with docking technique. The Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic scores were higher in the modified Jobe group (79 vs 74) and the docking technique group returned to play nearly 1 month sooner (12.4 months vs 11.8 months).20 However, comparing different techniques in a heterogenous patient population over 40 years is difficult. Many of the modified Jobe technique cases were performed in the early evolution of the rehabilitation and return-to-play programs. We believe that the current modified Jobe technique has results equal to any other variation.

Despite good results with reconstructions, the recovery is lengthy and most pitchers cannot fully return to competition level for 12 to 18 months. Extensive research has been performed in exploring alternatives to the traditional reconstruction. Advancements in orthobiologics and development of new surgical options seem to provide an alternative to reconstruction, and may allow faster return to competition with less morbidity.

PRP has been at the forefront of orthopedic research for the last 2 decades, mostly focused in tendon and bone healing. Due to the release of many inflammatory mediators, PRP is theorized to initiate a healing response with growth factors that can direct healing towards normal tissue.33 Two main types of PRP are reported based on the presence or absence of leukocytes. PRP has been studied in many applications, but only one clinical study on the UCL has been published to date. Podesta and colleagues23 injected PRP into the elbow of 34 baseball players with MRI-confirmed partial UCL tear. The athletes then underwent a rehabilitation program, which limited stress across the UCL. Type 1A PRP was used (leukocyte-rich, unactivated, 5x or greater platelet concentration33). Athletes were allowed to return to sport based on symptoms and examination findings. Eighty-eight percent returned to same level of play without complaints at average 70 week follow-up, and average return to play ranged from 10 to 15 weeks.23 No specific data were given on the 16 pitchers in the group, but with such a high rate of return, PRP needs to be further evaluated in the treatment of UCL injuries.

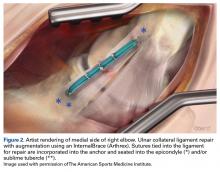

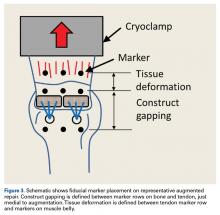

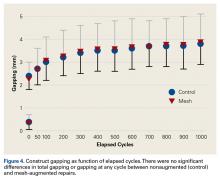

Another recent study from Dugas and colleagues18 presented primary UCL repair using a tape augment (InternalBrace, Arthrex). Nine matched cadaver elbows underwent UCL sectioning and then either modified Jobe reconstruction or primary repair of the UCL with placement of the InternalBrace. The biomechanical data showed the repair with internal brace to have slightly less gap, more stiffness, and higher failure strength, although these findings were not statistically significant.18 This bone-preserving technique with less exposure and healing of the native ligament may be another step towards good results with a quicker return to throwing.

Conclusion

UCL injuries can be disabling in throwers. Reconstruction has afforded throwers a high rate of return to preinjury function or better, and several techniques have been presented that produce acceptable results. Overall complication rates range from 10% to 15%, and the majority of complications are transient ulnar neuropraxias. Orthobiologics and repair with augmentation have more recently offered additional options that may improve success of nonoperative treatment or allow less-invasive surgical treatment. Increased involvement in youth sports and early specialization is driving injury rates in young athletes. The orthopedic community must continue to look for better ways to prevent these injuries and investigate better methods to return athletes to high-level competition.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E534-E540. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Fuss FK. The ulnar collateral ligament of the human elbow joint. Anatomy, function and biomechanics. J Anat. 1991;175:203-212.

2. Hotchkiss RN, Weiland AJ. Valgus stability of the elbow. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(3):372-377.

3. Morrey BF. Applied anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow joint. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:59-68.

4. Morrey BF, An KN. Articular and ligamentous contributions to the stability of the elbow joint. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(5):315-319.

5. Morrey BF, An KN. Functional anatomy of the ligaments of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 1985;(201):84-90.

6. Olsen SJ 2nd, Fleisig GS, Dun S, Loftice J, Andrews JR. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):905-912.

7. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):419-424.

8. Zaremski JL, Horodyski M, Donlan RM, Brisbane ST, Farmer KW. Does geographic location matter on the prevalence of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in collegiate baseball pitchers? Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(11):2325967115616582.

9. Erickson BJ, Nwachukwu BU, Rosas S, et al. Trends in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in the United States: A retrospective review of a large private-payer database from 2007 to 2011. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1770-1774.

10. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanism. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

11. Dillman CJ, Smutz P, Werner S. Valgus extension overload in baseball pitching. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(suppl 4):S135.

12. Hechtman KS, Tjin-A-Tsoi EW, Zvijac JE, Uribe JW, Latta LL. Biomechanics of a less invasive procedure for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(5):620-624.

13. Ahmad CS, Lee TQ, ElAttrache NS. Biomechanical evaluation of a new ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction technique with interference screw fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):332-337.

14. Jobe FW, Stark HE, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(8):1158-1163.

15. Savoie FH 3rd, Trenhaile SW, Roberts J, Field LD, Ramsey JR. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: a case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1066-1072.

16. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434.

17. Azar FM, Andrews JR, Wilk KE, Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):16-23.

18. Dugas JR, Walters BL, Beason DP, Fleisig GS, Chronister JE. Biomechanical comparison of ulnar collateral ligament repair with internal bracing versus modified Jobe reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):735-741.

19. Watson JN, McQueen P, Hutchinson MR. A systematic review of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2510-2516.

20. O’Brien DF, O’Hagan T, Stewart R, et al. Outcomes for ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: A retrospective review using the KJOC assessment score with two-year follow-up in an overhead throwing population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):934-940.

21. Ellenbecker TS, Mattalino AJ, Elam EA, Caplinger RA. Medial elbow joint laxity in professional baseball pitchers a bilateral comparison using stress radiography. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(3):420-424.

22. Timmerman LA, Schwartz ML, Andrews JR. Preoperative evaluation of the ulnar collateral ligament by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography evaluation in 25 baseball players with surgical confirmation. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):26-32.

23. Podesta L, Crow SA, Volkmer D, Bert T, Yocum LA. Treatment of partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in the elbow with platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1689-1694.

24. Thompson NW, Mockford BJ, Cran GW. Absence of the palmaris longus muscle: a population study. Ulster Med J. 2001;70(1):22-24.

25. Dugas JR, Bilotta J, Watts CD, et al. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction with gracilis tendon in athletes with intraligamentous bony excision technique and results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1578-1582.

26. Dargel J, Küpper F, Wegmann K, Oppermann J, Eysel P, Müller LP. Graft diameter does not influence primary stability of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(2):307-313.

27. Thompson WH, Jobe FW, Yocum LA, Pink MM. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in athletes: muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(2):152-157.

28. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. Rehabilitation of the elbow in the throwing athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(6):305-317.

29. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR, et al. Rehabilitation following elbow surgery in the throwing athlete. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1996;4:114-132.

30. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR, et al. Preventative and Rehabilitation Exercises for the Shoulder and Elbow. 4th ed. Birmingham, AL: American Sports Medicine Institute; 1996.

31. Osbahr DC, Cain EL, Raines BT, Fortenbaugh D, Dugas JR, Andrews JR. Long-term outcomes after ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in competitive baseball players minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):1333-1342.

32. Conway JE, Jobe FW, Glousman RE, Pink M. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes. Treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):67-83.

33. Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, Vieira A. Sports medicine applications of platelet rich plasma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(7):1185-1195.

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the primary restraint to valgus stress between 20° and 125° of motion.1-5 Overhead athletes, most commonly baseball pitchers, are at risk of developing UCL insufficiency, and dysfunction presents as pain with loss of velocity and control. Some injuries may present acutely while throwing, but many patients, when questioned, report a preceding period of either pain or loss of velocity and control.

Authors have documented a significant rise in elbow injuries in young athletes, especially pitchers.6 Extended seasons, higher pitch counts, year-round pitching, pitching while fatigued, and pitching for multiple teams are risk factors for elbow injuries.7 Pitchers in the southern United States are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction than those from the northern states.8 Pitchers who also play catcher are at a higher risk due to more total throws than those who pitch and play other positions or pitch only. Throwers with higher velocity are more likely to pitch in showcases, pitch for multiple teams, and pitch with pain and fatigue, and these are all risk factors.6 Also, in one study of youth baseball injuries, individuals in the injured group were found to be taller and heavier than those in the uninjured group.6 Pitch counts, rest from pitching during the off-season, adequate rest, and ensuring pain-free pitching can lessen the risk of injury.6 As expected with the rise in throwing injuries, the rise in medial elbow procedures has risen.9

While throwing, stress across the medial elbow has been measured to be nearly 300 N. A maximum varus force during pitching was measured to be 64 N-m at 95° ± 14°.10 Morrey and An4 determined that the UCL generated 54% of the varus force at 90° of flexion. During active pitching, this value is likely reduced due to simultaneous muscle contraction, but if one assumes the UCL bears 54% of the maximal load, the UCL must be able to withstand 34 N-m. The UCL can withstand a maximum valgus torque between 22.7 and 34 N-m11-13; therefore, during pitching, the UCL is at or above its failure load. After thousands of cycles over many years, one can imagine how the UCL might be injured.

Multiple techniques have been proposed in the surgical treatment of UCL injuries. Jobe14 pioneered UCL reconstruction in 1974 in Tommy John, a Major League Baseball pitcher. John returned to pitch successfully, and both the UCL and the reconstruction are commonly called by his name. Jobe14 reported his technique in 1986, and it has remained, with a few modifications, the primary method for reconstruction of the UCL (Figure 1).

Evaluation

A standard evaluation with physical examination and imaging is completed in all throwers with elbow pain. In our prior study,16 we found that 100% of patients experienced pain during athletic activity and that 96% of throwers complained of pain during late cocking and acceleration phases of the throwing motion. Nearly half reported an acute onset of pain, while 53% were unable to identify a single inciting event. Seventy-five percent of the acute injuries were during competition. Delayed diagnosis was very common, with an average time to diagnosis after onset of symptoms of 6.4 months. Neurologic symptoms were seen in 23% of athletes, most of which were ulnar nerve paresthesias during throwing.16

Physical examination includes inspection for swelling, hand intrinsic atrophy, neurovascular examination, range of motion, shoulder examination, and elbow stress examination. Range of motion at presentation averaged 5° to 135° with 85° of supination and pronation.16 All patients need neurologic evaluation for ulnar nerve dysfunction. Tinel test of the cubital tunnel was positive in 21%.16 Significant ulnar nerve dysfunction, including hand weakness, is much less common but must be well examined and documented. The shoulder must also be evaluated for loss of rotation, which can lead to increased stress on the elbow. An evaluation of mechanics may point out flaws in technique, which may be contributing to elbow stress. The UCL stress examination includes static stress at 30° of flexion, the milking test at 90°, and the moving valgus stress test. The presence of pain directly over the UCL or laxity compared to the uninvolved side is suggestive of UCL injury.

Radiographic evaluation is completed in all patients with concern for UCL injury. Standard x-rays of the elbow, including anteroposterior, medial, and lateral obliques, axial olecranon, and lateral views, are obtained to evaluate bony abnormalities. Fifty-seven percent of our series showed some abnormality, most commonly olecranon osteophyte formation or ectopic calcification within the UCL substance. Stress radiography rarely changed the treatment course and is somewhat difficult to interpret because of the reports documenting normal increased medial elbow opening in the dominant arm of throwing athletes.21 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is obtained very commonly in this patient population, and intra-articular contrast is crucial. Partial, undersurface tears are common, and a contrasted study better demonstrates undersurface tears or avulsions. The T-sign as described by Timmerman and colleagues22 using computed tomography (CT) arthrography shows partial undersurface detachment, which can be difficult to see without intra-articular contrast.22 This finding is very well visualized on MRI arthrogram as well (Figure 3).

Nonoperative Management

Nonoperative treatment is recommended for 3 months prior to performing reconstruction. Patients are given complete rest from throwing, but rehabilitation is initiated immediately. Rehabilitation exercises and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are prescribed, and activities that place valgus stress across the elbow are avoided. After resolution of symptoms, an interval throwing program is initiated, and the athlete is gradually returned to sport. Unfortunately, due to season-specific schedules and time-sensitive demands in high-level throwers, operative treatment is often chosen without an extended period of conservative treatment.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has recently been shown to improve healing rates and promote healing in partial UCL tears,23 and as orthobiologics are advanced, they will likely play a larger role in the treatment of UCL injuries.

Surgical Technique

At our institution, UCL reconstruction is performed with the modified Jobe technique as described by Azar and colleagues.17 Arthroscopy prior to reconstruction was routinely performed at our institution until we recognized that arthroscopy rarely changed the preoperative plan.16 Currently, the presence of anterior pathology such as loose bodies or osteochondral defect is our only indication for arthroscopy before reconstruction.

Ipsilateral palmaris autograft is our current graft of choice. This must be examined preoperatively because 16% of patients have unilateral absence and 9% have bilateral absence.24 In revision cases or in patients with insufficient or absent palmaris, contralateral palmaris followed by contralateral gracilis tendon is used. The contralateral gracilis is chosen because of ease of setup and position of the surgeon during the harvest. Gracilis tendon is also used in cases with bony involvement of the ligament based on the results from Dugas and colleagues.25 Toe extensors, plantaris, and patellar tendon grafts have also been used. One recent study showed that neither graft choice nor diameter affected resistance to valgus stress, and that all reconstruction types restored strength at 60° to 120° of flexion.26

Ulnar nerve transposition is performed in all cases regardless of the presence of preoperative nerve symptoms. A complete decompression is completed proximally to the Arcade of Struthers and distally to the deep portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris. A single fascial sling of medial intermuscular septum originating from the epicondylar attachment is used to stabilize the nerve without compression. At wound closure, the deep fascia on the posterior skin flap is also sewn into the cubital tunnel to prevent the nerve from subluxating back into the groove. A single suture is placed distally closing the muscle fascia to prevent propagation of the fascial incision, which can lead to herniation. Transposition is necessary because of the ulnar nerve exposure required in the modified Jobe technique to allow elevation of the deep flexor muscle mass for ligament exposure.

The reconstruction is completed as described by Jobe14 but with a few modifications as described by Azar and colleagues17 and slight adaptations implemented since that time. The flexor-pronator mass is retracted laterally instead of detachment or splitting as described by Thompson and colleagues.27 A subcutaneous rather than a submuscular ulnar nerve transposition is used.

The patient is positioned supine using an arm board. If gracilis tendon is chosen, the contralateral leg is prepped and draped simultaneously. A tourniquet is inflated after exsanguination. A medial approach is performed, and the medial antebrachial nerve is located and protected. The ulnar nerve is then located in the cubital tunnel and mobilized. The neurolysis extends to the deep portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris distally and proximally to the Arcade of Struthers, and the nerve is retracted with a vessel loop. The flexor muscle mass is not elevated from the medial epicondyle; rather, it is retracted anteriorly by small Hohmann retractors. The dissection is carried down to the UCL and found at its attachments to the medial epicondyle and sublime tubercle. If no tear is seen on the superficial surface of the ligament, a longitudinal incision is made through the ligament. Undersurface tears, partial tears, and avulsions can then be identified (Figure 4).

The autologous graft of choice is then harvested. Our technique for palmaris harvest is performed with three 1-cm transverse incisions. The palmaris is palpated and marked with the first incision made near the distal wrist crease, and the second incision is made 3 to 4 cm proximal to the first. The tendon is found in both distal incisions and cut distally with the wrist flexed to maximize tendon length. The tendon is then pulled through the second incision and tensioned to identify the most proximal location the tendon can be palpated. A third incision is made directly over this point and carried down to cut the tendon. This usually provides a graft length of 15 to 20 cm; 13 cm is the minimum graft length to ensure good graft fixation. Muscle is removed from the tendon and each end is secured with a No. 1 nonabsorbable suture in a locking fashion.

If posterior osteophytes are present, they are removed through a posterior, vertical arthrotomy. Over-resection of the olecranon must be avoided, as this can further destabilize the elbow and place increased stress on the reconstruction. Posterior loose bodies can also be removed through this arthrotomy. The arthrotomy is then closed with absorbable suture.

Tunnel placement is critical to success. A 3.2-mm drill bit is used with palmaris grafts and a 4-mm drill bit is used with gracilis grafts. Two convergent tunnels are drilled in the medial epicondyle in a Y fashion and 2 convergent tunnels are drilled at the sublime tubercle in a U or V fashion. After drilling the first tunnel on each side, a hemostat is placed in the tunnel as an aiming point to ensure a complete tunnel is made. The junction is smoothed with a curette, leaving a 5-mm bone bridge between the articular surface and the tunnels. A bent Hewson suture passer is used to pass one end of the graft through the ulna. The 2 limbs of the tendon graft are then passed through the humeral tunnels, creating a figure-of-eight. A varus stress is applied with the elbow at roughly 30° and the 2 limbs are tied together with a No. 1 nonabsorbable suture. If enough graft remains, one or both limbs are passed back through the tunnels and secured again with No. 1 nonabsorbable suture. The 2 limbs are then tied side-to-side, incorporating the native ligament to further secure and tighten the reconstruction.

The ulnar nerve is then secured using a strip of medial intermuscular septum left intact to its insertion at the medial epicondyle. This is attached to the flexor-pronator muscle fascia with a 3-0 nonabsorbable suture. Enough length should be harvested from the septum to ensure there is no compression on the nerve. The deep posterior fascial tissue is then sewn to the periosteum of the medial epicondyle to further prevent subluxation of the nerve back into the groove. The skin is then closed in layered fashion over a superficial drain. The patient is placed in a well-padded posterior splint for 1 week, then the rehabilitation protocol is initiated as discussed below.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

A standardized postoperative 4-phase rehabilitation program for ulnar collateral reconstruction is followed as described by Wilk and colleagues.28-30 The first phase begins immediately after surgery and continues for 4 weeks. During surgery, the patient’s elbow is placed in a compression dressing with a posterior splint to immobilize the elbow in 90° of flexion with wrist motion for 1 week to allow initial healing. Full range of motion of the elbow joint is restored by the end of the fifth to sixth week after surgery.

During phase II (weeks 4-10), a progressive isotonic strengthening program is initiated. Exercises are focused on scapular, rotator cuff, deltoid, and arm musculature. Shoulder range of motion and stretching exercises are performed during this phase and the Thrower’s Ten exercise program is initiated. Any adaptations or strength deficits are addressed during this phase.

During the advanced strengthening phase (phase III), from weeks 10 to 16, a sport-specific exercise/rehabilitation program is initiated. During this phase, stretching and flexibility exercises are performed to enhance strength, power, and endurance. During this phase the patient is placed on the advanced Thrower’s Ten program. Isotonic strengthening exercises are progressed, and at week 12, the athlete is allowed to begin an isotonic lifting program, including bench press, seated rowing, latissimus dorsi pull downs, triceps push downs, and biceps curls. In addition, the athlete performs specific exercises to emphasize sport-specific movements. At week 12, overhead athletes begin a 2-hand plyometric throwing program, and at 14 weeks, a 1

Discussion

Results after ulnar collateral reconstruction have been good. In our series of 743 patients, 83% returned to the same or higher level at an average of 11.6 months.16 There was a 4% major complication rate and 16% minor complication rate. Major complications included medial epicondyle fracture (0.5%), significant ulnar nerve dysfunction (1 patient), rupture of graft (1%), and graft site infection. Sixteen percent of patients had ulnar nerve dysfunction, and 82% of these resolved within 6 weeks. All but 1 patient’s paresthesias resolved within 1 year.16 The 10-year follow-up of this group of patients included 256 patients and was reported by Osbahr and colleagues31 in 2014. Retirement from baseball was due to reasons other than the elbow in 86%, and 98% were still able to throw on at least a recreational level. The overall longevity was 3.6 years, with 2.9 years at pre-injury level or higher. Statistically, pitchers performed at a higher level after reconstruction.31

A recent review by Erickson and colleagues9 showed an overall 82% excellent and 8% good result when evaluating different techniques, including the American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) modification of Jobe’s technique, docking technique, and Jobe’s technique. With an overall complication rate of 10% (75% of which was transient ulnar neuritis), the procedure was deemed overall a safe surgical option. Collegiate athletes had the highest return to sport (95%) compared with high school athletes (89%) and professional athletes (86%). The docking technique had the highest rate of return to play (97%) compared with ASMI technique (93%) and Jobe technique (66%).9 Results after repair have not been as good as reconstruction, as reported in 2 studies.16,32 Savoie and colleagues,15 however, reported 93% good/excellent results after primary UCL repair alone.

Another recent review of outcomes showed an overall return to same or higher level was best with docking or modified docking techniques (90.4% and 91.3%, respectively).19 Overall return with modified Jobe technique was 77%.19 O’Brien and colleagues20 performed a review of 33 patients with either modified Jobe or docking technique that showed 81% return to same or higher level with modified Jobe vs 92% with docking technique. The Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic scores were higher in the modified Jobe group (79 vs 74) and the docking technique group returned to play nearly 1 month sooner (12.4 months vs 11.8 months).20 However, comparing different techniques in a heterogenous patient population over 40 years is difficult. Many of the modified Jobe technique cases were performed in the early evolution of the rehabilitation and return-to-play programs. We believe that the current modified Jobe technique has results equal to any other variation.

Despite good results with reconstructions, the recovery is lengthy and most pitchers cannot fully return to competition level for 12 to 18 months. Extensive research has been performed in exploring alternatives to the traditional reconstruction. Advancements in orthobiologics and development of new surgical options seem to provide an alternative to reconstruction, and may allow faster return to competition with less morbidity.

PRP has been at the forefront of orthopedic research for the last 2 decades, mostly focused in tendon and bone healing. Due to the release of many inflammatory mediators, PRP is theorized to initiate a healing response with growth factors that can direct healing towards normal tissue.33 Two main types of PRP are reported based on the presence or absence of leukocytes. PRP has been studied in many applications, but only one clinical study on the UCL has been published to date. Podesta and colleagues23 injected PRP into the elbow of 34 baseball players with MRI-confirmed partial UCL tear. The athletes then underwent a rehabilitation program, which limited stress across the UCL. Type 1A PRP was used (leukocyte-rich, unactivated, 5x or greater platelet concentration33). Athletes were allowed to return to sport based on symptoms and examination findings. Eighty-eight percent returned to same level of play without complaints at average 70 week follow-up, and average return to play ranged from 10 to 15 weeks.23 No specific data were given on the 16 pitchers in the group, but with such a high rate of return, PRP needs to be further evaluated in the treatment of UCL injuries.

Another recent study from Dugas and colleagues18 presented primary UCL repair using a tape augment (InternalBrace, Arthrex). Nine matched cadaver elbows underwent UCL sectioning and then either modified Jobe reconstruction or primary repair of the UCL with placement of the InternalBrace. The biomechanical data showed the repair with internal brace to have slightly less gap, more stiffness, and higher failure strength, although these findings were not statistically significant.18 This bone-preserving technique with less exposure and healing of the native ligament may be another step towards good results with a quicker return to throwing.

Conclusion

UCL injuries can be disabling in throwers. Reconstruction has afforded throwers a high rate of return to preinjury function or better, and several techniques have been presented that produce acceptable results. Overall complication rates range from 10% to 15%, and the majority of complications are transient ulnar neuropraxias. Orthobiologics and repair with augmentation have more recently offered additional options that may improve success of nonoperative treatment or allow less-invasive surgical treatment. Increased involvement in youth sports and early specialization is driving injury rates in young athletes. The orthopedic community must continue to look for better ways to prevent these injuries and investigate better methods to return athletes to high-level competition.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E534-E540. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the primary restraint to valgus stress between 20° and 125° of motion.1-5 Overhead athletes, most commonly baseball pitchers, are at risk of developing UCL insufficiency, and dysfunction presents as pain with loss of velocity and control. Some injuries may present acutely while throwing, but many patients, when questioned, report a preceding period of either pain or loss of velocity and control.

Authors have documented a significant rise in elbow injuries in young athletes, especially pitchers.6 Extended seasons, higher pitch counts, year-round pitching, pitching while fatigued, and pitching for multiple teams are risk factors for elbow injuries.7 Pitchers in the southern United States are more likely to undergo UCL reconstruction than those from the northern states.8 Pitchers who also play catcher are at a higher risk due to more total throws than those who pitch and play other positions or pitch only. Throwers with higher velocity are more likely to pitch in showcases, pitch for multiple teams, and pitch with pain and fatigue, and these are all risk factors.6 Also, in one study of youth baseball injuries, individuals in the injured group were found to be taller and heavier than those in the uninjured group.6 Pitch counts, rest from pitching during the off-season, adequate rest, and ensuring pain-free pitching can lessen the risk of injury.6 As expected with the rise in throwing injuries, the rise in medial elbow procedures has risen.9

While throwing, stress across the medial elbow has been measured to be nearly 300 N. A maximum varus force during pitching was measured to be 64 N-m at 95° ± 14°.10 Morrey and An4 determined that the UCL generated 54% of the varus force at 90° of flexion. During active pitching, this value is likely reduced due to simultaneous muscle contraction, but if one assumes the UCL bears 54% of the maximal load, the UCL must be able to withstand 34 N-m. The UCL can withstand a maximum valgus torque between 22.7 and 34 N-m11-13; therefore, during pitching, the UCL is at or above its failure load. After thousands of cycles over many years, one can imagine how the UCL might be injured.

Multiple techniques have been proposed in the surgical treatment of UCL injuries. Jobe14 pioneered UCL reconstruction in 1974 in Tommy John, a Major League Baseball pitcher. John returned to pitch successfully, and both the UCL and the reconstruction are commonly called by his name. Jobe14 reported his technique in 1986, and it has remained, with a few modifications, the primary method for reconstruction of the UCL (Figure 1).

Evaluation

A standard evaluation with physical examination and imaging is completed in all throwers with elbow pain. In our prior study,16 we found that 100% of patients experienced pain during athletic activity and that 96% of throwers complained of pain during late cocking and acceleration phases of the throwing motion. Nearly half reported an acute onset of pain, while 53% were unable to identify a single inciting event. Seventy-five percent of the acute injuries were during competition. Delayed diagnosis was very common, with an average time to diagnosis after onset of symptoms of 6.4 months. Neurologic symptoms were seen in 23% of athletes, most of which were ulnar nerve paresthesias during throwing.16

Physical examination includes inspection for swelling, hand intrinsic atrophy, neurovascular examination, range of motion, shoulder examination, and elbow stress examination. Range of motion at presentation averaged 5° to 135° with 85° of supination and pronation.16 All patients need neurologic evaluation for ulnar nerve dysfunction. Tinel test of the cubital tunnel was positive in 21%.16 Significant ulnar nerve dysfunction, including hand weakness, is much less common but must be well examined and documented. The shoulder must also be evaluated for loss of rotation, which can lead to increased stress on the elbow. An evaluation of mechanics may point out flaws in technique, which may be contributing to elbow stress. The UCL stress examination includes static stress at 30° of flexion, the milking test at 90°, and the moving valgus stress test. The presence of pain directly over the UCL or laxity compared to the uninvolved side is suggestive of UCL injury.

Radiographic evaluation is completed in all patients with concern for UCL injury. Standard x-rays of the elbow, including anteroposterior, medial, and lateral obliques, axial olecranon, and lateral views, are obtained to evaluate bony abnormalities. Fifty-seven percent of our series showed some abnormality, most commonly olecranon osteophyte formation or ectopic calcification within the UCL substance. Stress radiography rarely changed the treatment course and is somewhat difficult to interpret because of the reports documenting normal increased medial elbow opening in the dominant arm of throwing athletes.21 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is obtained very commonly in this patient population, and intra-articular contrast is crucial. Partial, undersurface tears are common, and a contrasted study better demonstrates undersurface tears or avulsions. The T-sign as described by Timmerman and colleagues22 using computed tomography (CT) arthrography shows partial undersurface detachment, which can be difficult to see without intra-articular contrast.22 This finding is very well visualized on MRI arthrogram as well (Figure 3).

Nonoperative Management

Nonoperative treatment is recommended for 3 months prior to performing reconstruction. Patients are given complete rest from throwing, but rehabilitation is initiated immediately. Rehabilitation exercises and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are prescribed, and activities that place valgus stress across the elbow are avoided. After resolution of symptoms, an interval throwing program is initiated, and the athlete is gradually returned to sport. Unfortunately, due to season-specific schedules and time-sensitive demands in high-level throwers, operative treatment is often chosen without an extended period of conservative treatment.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has recently been shown to improve healing rates and promote healing in partial UCL tears,23 and as orthobiologics are advanced, they will likely play a larger role in the treatment of UCL injuries.

Surgical Technique

At our institution, UCL reconstruction is performed with the modified Jobe technique as described by Azar and colleagues.17 Arthroscopy prior to reconstruction was routinely performed at our institution until we recognized that arthroscopy rarely changed the preoperative plan.16 Currently, the presence of anterior pathology such as loose bodies or osteochondral defect is our only indication for arthroscopy before reconstruction.

Ipsilateral palmaris autograft is our current graft of choice. This must be examined preoperatively because 16% of patients have unilateral absence and 9% have bilateral absence.24 In revision cases or in patients with insufficient or absent palmaris, contralateral palmaris followed by contralateral gracilis tendon is used. The contralateral gracilis is chosen because of ease of setup and position of the surgeon during the harvest. Gracilis tendon is also used in cases with bony involvement of the ligament based on the results from Dugas and colleagues.25 Toe extensors, plantaris, and patellar tendon grafts have also been used. One recent study showed that neither graft choice nor diameter affected resistance to valgus stress, and that all reconstruction types restored strength at 60° to 120° of flexion.26

Ulnar nerve transposition is performed in all cases regardless of the presence of preoperative nerve symptoms. A complete decompression is completed proximally to the Arcade of Struthers and distally to the deep portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris. A single fascial sling of medial intermuscular septum originating from the epicondylar attachment is used to stabilize the nerve without compression. At wound closure, the deep fascia on the posterior skin flap is also sewn into the cubital tunnel to prevent the nerve from subluxating back into the groove. A single suture is placed distally closing the muscle fascia to prevent propagation of the fascial incision, which can lead to herniation. Transposition is necessary because of the ulnar nerve exposure required in the modified Jobe technique to allow elevation of the deep flexor muscle mass for ligament exposure.

The reconstruction is completed as described by Jobe14 but with a few modifications as described by Azar and colleagues17 and slight adaptations implemented since that time. The flexor-pronator mass is retracted laterally instead of detachment or splitting as described by Thompson and colleagues.27 A subcutaneous rather than a submuscular ulnar nerve transposition is used.

The patient is positioned supine using an arm board. If gracilis tendon is chosen, the contralateral leg is prepped and draped simultaneously. A tourniquet is inflated after exsanguination. A medial approach is performed, and the medial antebrachial nerve is located and protected. The ulnar nerve is then located in the cubital tunnel and mobilized. The neurolysis extends to the deep portion of the flexor carpi ulnaris distally and proximally to the Arcade of Struthers, and the nerve is retracted with a vessel loop. The flexor muscle mass is not elevated from the medial epicondyle; rather, it is retracted anteriorly by small Hohmann retractors. The dissection is carried down to the UCL and found at its attachments to the medial epicondyle and sublime tubercle. If no tear is seen on the superficial surface of the ligament, a longitudinal incision is made through the ligament. Undersurface tears, partial tears, and avulsions can then be identified (Figure 4).

The autologous graft of choice is then harvested. Our technique for palmaris harvest is performed with three 1-cm transverse incisions. The palmaris is palpated and marked with the first incision made near the distal wrist crease, and the second incision is made 3 to 4 cm proximal to the first. The tendon is found in both distal incisions and cut distally with the wrist flexed to maximize tendon length. The tendon is then pulled through the second incision and tensioned to identify the most proximal location the tendon can be palpated. A third incision is made directly over this point and carried down to cut the tendon. This usually provides a graft length of 15 to 20 cm; 13 cm is the minimum graft length to ensure good graft fixation. Muscle is removed from the tendon and each end is secured with a No. 1 nonabsorbable suture in a locking fashion.

If posterior osteophytes are present, they are removed through a posterior, vertical arthrotomy. Over-resection of the olecranon must be avoided, as this can further destabilize the elbow and place increased stress on the reconstruction. Posterior loose bodies can also be removed through this arthrotomy. The arthrotomy is then closed with absorbable suture.

Tunnel placement is critical to success. A 3.2-mm drill bit is used with palmaris grafts and a 4-mm drill bit is used with gracilis grafts. Two convergent tunnels are drilled in the medial epicondyle in a Y fashion and 2 convergent tunnels are drilled at the sublime tubercle in a U or V fashion. After drilling the first tunnel on each side, a hemostat is placed in the tunnel as an aiming point to ensure a complete tunnel is made. The junction is smoothed with a curette, leaving a 5-mm bone bridge between the articular surface and the tunnels. A bent Hewson suture passer is used to pass one end of the graft through the ulna. The 2 limbs of the tendon graft are then passed through the humeral tunnels, creating a figure-of-eight. A varus stress is applied with the elbow at roughly 30° and the 2 limbs are tied together with a No. 1 nonabsorbable suture. If enough graft remains, one or both limbs are passed back through the tunnels and secured again with No. 1 nonabsorbable suture. The 2 limbs are then tied side-to-side, incorporating the native ligament to further secure and tighten the reconstruction.

The ulnar nerve is then secured using a strip of medial intermuscular septum left intact to its insertion at the medial epicondyle. This is attached to the flexor-pronator muscle fascia with a 3-0 nonabsorbable suture. Enough length should be harvested from the septum to ensure there is no compression on the nerve. The deep posterior fascial tissue is then sewn to the periosteum of the medial epicondyle to further prevent subluxation of the nerve back into the groove. The skin is then closed in layered fashion over a superficial drain. The patient is placed in a well-padded posterior splint for 1 week, then the rehabilitation protocol is initiated as discussed below.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

A standardized postoperative 4-phase rehabilitation program for ulnar collateral reconstruction is followed as described by Wilk and colleagues.28-30 The first phase begins immediately after surgery and continues for 4 weeks. During surgery, the patient’s elbow is placed in a compression dressing with a posterior splint to immobilize the elbow in 90° of flexion with wrist motion for 1 week to allow initial healing. Full range of motion of the elbow joint is restored by the end of the fifth to sixth week after surgery.

During phase II (weeks 4-10), a progressive isotonic strengthening program is initiated. Exercises are focused on scapular, rotator cuff, deltoid, and arm musculature. Shoulder range of motion and stretching exercises are performed during this phase and the Thrower’s Ten exercise program is initiated. Any adaptations or strength deficits are addressed during this phase.

During the advanced strengthening phase (phase III), from weeks 10 to 16, a sport-specific exercise/rehabilitation program is initiated. During this phase, stretching and flexibility exercises are performed to enhance strength, power, and endurance. During this phase the patient is placed on the advanced Thrower’s Ten program. Isotonic strengthening exercises are progressed, and at week 12, the athlete is allowed to begin an isotonic lifting program, including bench press, seated rowing, latissimus dorsi pull downs, triceps push downs, and biceps curls. In addition, the athlete performs specific exercises to emphasize sport-specific movements. At week 12, overhead athletes begin a 2-hand plyometric throwing program, and at 14 weeks, a 1

Discussion

Results after ulnar collateral reconstruction have been good. In our series of 743 patients, 83% returned to the same or higher level at an average of 11.6 months.16 There was a 4% major complication rate and 16% minor complication rate. Major complications included medial epicondyle fracture (0.5%), significant ulnar nerve dysfunction (1 patient), rupture of graft (1%), and graft site infection. Sixteen percent of patients had ulnar nerve dysfunction, and 82% of these resolved within 6 weeks. All but 1 patient’s paresthesias resolved within 1 year.16 The 10-year follow-up of this group of patients included 256 patients and was reported by Osbahr and colleagues31 in 2014. Retirement from baseball was due to reasons other than the elbow in 86%, and 98% were still able to throw on at least a recreational level. The overall longevity was 3.6 years, with 2.9 years at pre-injury level or higher. Statistically, pitchers performed at a higher level after reconstruction.31

A recent review by Erickson and colleagues9 showed an overall 82% excellent and 8% good result when evaluating different techniques, including the American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI) modification of Jobe’s technique, docking technique, and Jobe’s technique. With an overall complication rate of 10% (75% of which was transient ulnar neuritis), the procedure was deemed overall a safe surgical option. Collegiate athletes had the highest return to sport (95%) compared with high school athletes (89%) and professional athletes (86%). The docking technique had the highest rate of return to play (97%) compared with ASMI technique (93%) and Jobe technique (66%).9 Results after repair have not been as good as reconstruction, as reported in 2 studies.16,32 Savoie and colleagues,15 however, reported 93% good/excellent results after primary UCL repair alone.

Another recent review of outcomes showed an overall return to same or higher level was best with docking or modified docking techniques (90.4% and 91.3%, respectively).19 Overall return with modified Jobe technique was 77%.19 O’Brien and colleagues20 performed a review of 33 patients with either modified Jobe or docking technique that showed 81% return to same or higher level with modified Jobe vs 92% with docking technique. The Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic scores were higher in the modified Jobe group (79 vs 74) and the docking technique group returned to play nearly 1 month sooner (12.4 months vs 11.8 months).20 However, comparing different techniques in a heterogenous patient population over 40 years is difficult. Many of the modified Jobe technique cases were performed in the early evolution of the rehabilitation and return-to-play programs. We believe that the current modified Jobe technique has results equal to any other variation.

Despite good results with reconstructions, the recovery is lengthy and most pitchers cannot fully return to competition level for 12 to 18 months. Extensive research has been performed in exploring alternatives to the traditional reconstruction. Advancements in orthobiologics and development of new surgical options seem to provide an alternative to reconstruction, and may allow faster return to competition with less morbidity.

PRP has been at the forefront of orthopedic research for the last 2 decades, mostly focused in tendon and bone healing. Due to the release of many inflammatory mediators, PRP is theorized to initiate a healing response with growth factors that can direct healing towards normal tissue.33 Two main types of PRP are reported based on the presence or absence of leukocytes. PRP has been studied in many applications, but only one clinical study on the UCL has been published to date. Podesta and colleagues23 injected PRP into the elbow of 34 baseball players with MRI-confirmed partial UCL tear. The athletes then underwent a rehabilitation program, which limited stress across the UCL. Type 1A PRP was used (leukocyte-rich, unactivated, 5x or greater platelet concentration33). Athletes were allowed to return to sport based on symptoms and examination findings. Eighty-eight percent returned to same level of play without complaints at average 70 week follow-up, and average return to play ranged from 10 to 15 weeks.23 No specific data were given on the 16 pitchers in the group, but with such a high rate of return, PRP needs to be further evaluated in the treatment of UCL injuries.

Another recent study from Dugas and colleagues18 presented primary UCL repair using a tape augment (InternalBrace, Arthrex). Nine matched cadaver elbows underwent UCL sectioning and then either modified Jobe reconstruction or primary repair of the UCL with placement of the InternalBrace. The biomechanical data showed the repair with internal brace to have slightly less gap, more stiffness, and higher failure strength, although these findings were not statistically significant.18 This bone-preserving technique with less exposure and healing of the native ligament may be another step towards good results with a quicker return to throwing.

Conclusion

UCL injuries can be disabling in throwers. Reconstruction has afforded throwers a high rate of return to preinjury function or better, and several techniques have been presented that produce acceptable results. Overall complication rates range from 10% to 15%, and the majority of complications are transient ulnar neuropraxias. Orthobiologics and repair with augmentation have more recently offered additional options that may improve success of nonoperative treatment or allow less-invasive surgical treatment. Increased involvement in youth sports and early specialization is driving injury rates in young athletes. The orthopedic community must continue to look for better ways to prevent these injuries and investigate better methods to return athletes to high-level competition.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E534-E540. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Fuss FK. The ulnar collateral ligament of the human elbow joint. Anatomy, function and biomechanics. J Anat. 1991;175:203-212.

2. Hotchkiss RN, Weiland AJ. Valgus stability of the elbow. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(3):372-377.

3. Morrey BF. Applied anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow joint. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:59-68.

4. Morrey BF, An KN. Articular and ligamentous contributions to the stability of the elbow joint. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(5):315-319.

5. Morrey BF, An KN. Functional anatomy of the ligaments of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 1985;(201):84-90.

6. Olsen SJ 2nd, Fleisig GS, Dun S, Loftice J, Andrews JR. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):905-912.

7. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):419-424.

8. Zaremski JL, Horodyski M, Donlan RM, Brisbane ST, Farmer KW. Does geographic location matter on the prevalence of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in collegiate baseball pitchers? Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(11):2325967115616582.

9. Erickson BJ, Nwachukwu BU, Rosas S, et al. Trends in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in the United States: A retrospective review of a large private-payer database from 2007 to 2011. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1770-1774.

10. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanism. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

11. Dillman CJ, Smutz P, Werner S. Valgus extension overload in baseball pitching. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(suppl 4):S135.

12. Hechtman KS, Tjin-A-Tsoi EW, Zvijac JE, Uribe JW, Latta LL. Biomechanics of a less invasive procedure for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(5):620-624.

13. Ahmad CS, Lee TQ, ElAttrache NS. Biomechanical evaluation of a new ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction technique with interference screw fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):332-337.

14. Jobe FW, Stark HE, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(8):1158-1163.

15. Savoie FH 3rd, Trenhaile SW, Roberts J, Field LD, Ramsey JR. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: a case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1066-1072.

16. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434.

17. Azar FM, Andrews JR, Wilk KE, Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):16-23.

18. Dugas JR, Walters BL, Beason DP, Fleisig GS, Chronister JE. Biomechanical comparison of ulnar collateral ligament repair with internal bracing versus modified Jobe reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):735-741.

19. Watson JN, McQueen P, Hutchinson MR. A systematic review of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2510-2516.

20. O’Brien DF, O’Hagan T, Stewart R, et al. Outcomes for ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: A retrospective review using the KJOC assessment score with two-year follow-up in an overhead throwing population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):934-940.

21. Ellenbecker TS, Mattalino AJ, Elam EA, Caplinger RA. Medial elbow joint laxity in professional baseball pitchers a bilateral comparison using stress radiography. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(3):420-424.

22. Timmerman LA, Schwartz ML, Andrews JR. Preoperative evaluation of the ulnar collateral ligament by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography evaluation in 25 baseball players with surgical confirmation. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):26-32.

23. Podesta L, Crow SA, Volkmer D, Bert T, Yocum LA. Treatment of partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in the elbow with platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1689-1694.

24. Thompson NW, Mockford BJ, Cran GW. Absence of the palmaris longus muscle: a population study. Ulster Med J. 2001;70(1):22-24.

25. Dugas JR, Bilotta J, Watts CD, et al. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction with gracilis tendon in athletes with intraligamentous bony excision technique and results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1578-1582.

26. Dargel J, Küpper F, Wegmann K, Oppermann J, Eysel P, Müller LP. Graft diameter does not influence primary stability of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(2):307-313.

27. Thompson WH, Jobe FW, Yocum LA, Pink MM. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in athletes: muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(2):152-157.

28. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. Rehabilitation of the elbow in the throwing athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(6):305-317.

29. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR, et al. Rehabilitation following elbow surgery in the throwing athlete. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1996;4:114-132.

30. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR, et al. Preventative and Rehabilitation Exercises for the Shoulder and Elbow. 4th ed. Birmingham, AL: American Sports Medicine Institute; 1996.

31. Osbahr DC, Cain EL, Raines BT, Fortenbaugh D, Dugas JR, Andrews JR. Long-term outcomes after ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in competitive baseball players minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):1333-1342.

32. Conway JE, Jobe FW, Glousman RE, Pink M. Medial instability of the elbow in throwing athletes. Treatment by repair or reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(1):67-83.

33. Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, Vieira A. Sports medicine applications of platelet rich plasma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(7):1185-1195.

1. Fuss FK. The ulnar collateral ligament of the human elbow joint. Anatomy, function and biomechanics. J Anat. 1991;175:203-212.

2. Hotchkiss RN, Weiland AJ. Valgus stability of the elbow. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(3):372-377.

3. Morrey BF. Applied anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow joint. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:59-68.

4. Morrey BF, An KN. Articular and ligamentous contributions to the stability of the elbow joint. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(5):315-319.

5. Morrey BF, An KN. Functional anatomy of the ligaments of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 1985;(201):84-90.

6. Olsen SJ 2nd, Fleisig GS, Dun S, Loftice J, Andrews JR. Risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):905-912.

7. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Prevention of elbow injuries in youth baseball pitchers. Sports Health. 2012;4(5):419-424.

8. Zaremski JL, Horodyski M, Donlan RM, Brisbane ST, Farmer KW. Does geographic location matter on the prevalence of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in collegiate baseball pitchers? Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(11):2325967115616582.

9. Erickson BJ, Nwachukwu BU, Rosas S, et al. Trends in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in the United States: A retrospective review of a large private-payer database from 2007 to 2011. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(7):1770-1774.

10. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanism. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233-239.

11. Dillman CJ, Smutz P, Werner S. Valgus extension overload in baseball pitching. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(suppl 4):S135.

12. Hechtman KS, Tjin-A-Tsoi EW, Zvijac JE, Uribe JW, Latta LL. Biomechanics of a less invasive procedure for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(5):620-624.

13. Ahmad CS, Lee TQ, ElAttrache NS. Biomechanical evaluation of a new ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction technique with interference screw fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):332-337.

14. Jobe FW, Stark HE, Lombardo SJ. Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(8):1158-1163.

15. Savoie FH 3rd, Trenhaile SW, Roberts J, Field LD, Ramsey JR. Primary repair of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in young athletes: a case series of injuries to the proximal and distal ends of the ligament. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(6):1066-1072.

16. Cain EL, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, et al. Outcome of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow in 1281 athletes results in 743 athletes with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2426-2434.

17. Azar FM, Andrews JR, Wilk KE, Groh D. Operative treatment of ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(1):16-23.

18. Dugas JR, Walters BL, Beason DP, Fleisig GS, Chronister JE. Biomechanical comparison of ulnar collateral ligament repair with internal bracing versus modified Jobe reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):735-741.

19. Watson JN, McQueen P, Hutchinson MR. A systematic review of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2510-2516.

20. O’Brien DF, O’Hagan T, Stewart R, et al. Outcomes for ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: A retrospective review using the KJOC assessment score with two-year follow-up in an overhead throwing population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):934-940.

21. Ellenbecker TS, Mattalino AJ, Elam EA, Caplinger RA. Medial elbow joint laxity in professional baseball pitchers a bilateral comparison using stress radiography. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(3):420-424.

22. Timmerman LA, Schwartz ML, Andrews JR. Preoperative evaluation of the ulnar collateral ligament by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography evaluation in 25 baseball players with surgical confirmation. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):26-32.

23. Podesta L, Crow SA, Volkmer D, Bert T, Yocum LA. Treatment of partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in the elbow with platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1689-1694.

24. Thompson NW, Mockford BJ, Cran GW. Absence of the palmaris longus muscle: a population study. Ulster Med J. 2001;70(1):22-24.

25. Dugas JR, Bilotta J, Watts CD, et al. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction with gracilis tendon in athletes with intraligamentous bony excision technique and results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1578-1582.

26. Dargel J, Küpper F, Wegmann K, Oppermann J, Eysel P, Müller LP. Graft diameter does not influence primary stability of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(2):307-313.

27. Thompson WH, Jobe FW, Yocum LA, Pink MM. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in athletes: muscle-splitting approach without transposition of the ulnar nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(2):152-157.

28. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR. Rehabilitation of the elbow in the throwing athlete. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(6):305-317.

29. Wilk KE, Arrigo CA, Andrews JR, et al. Rehabilitation following elbow surgery in the throwing athlete. Oper Tech Sports Med. 1996;4:114-132.