User login

The American Journal of Orthopedics is an Index Medicus publication that is valued by orthopedic surgeons for its peer-reviewed, practice-oriented clinical information. Most articles are written by specialists at leading teaching institutions and help incorporate the latest technology into everyday practice.

Outcomes and Aseptic Survivorship of Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty

Over the past 3 decades, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been considered a safe and effective treatment for end-stage knee arthritis.1 However, as the population, the incidence of obesity, and life expectancy continue to increase, the number of TKAs will rise as well.2,3 It is expected that over the next 16 years, the number of TKAs performed annually will exceed 3 million in the United States alone.4 This projection represents an over 600% increase from 2005 figures.5 Given the demographic shift expected over the next 2 decades, patients are anticipated to undergo these procedures at younger ages compared with previous generations, such that those age 65 years or younger will account for more than 55% of primary TKAs.6 More important, given this exponential growth in primary TKAs, there will be a concordant rise in revision procedures. It is expected that, the annual number has roughly doubled from that recorded for 2005.4

Compared with primary TKAs, however, revision TKAs have had less promising results, with survivorship as low as 60% over shorter periods.7,8 In addition, recent studies have found an even higher degree of dissatisfaction and functional limitations among revision TKA patients than among primary TKA patients, 15% to 30% of whom are unhappy with their procedures.9-11 These shortcomings of revision TKAs are thought to result from several factors, including poor bone quality, insufficient bone stock, ligamentous instability, soft-tissue incompetence, infection, malalignment, problems with extensor mechanisms, and substantial pain of uncertain etiology.

Despite there being several complex factors that can lead to worse outcomes with revision TKAs, surgeons are expected to produce results equivalent to those of primary TKAs. It is therefore imperative to delineate the objective and subjective outcomes of revision techniques to identify areas in need of improvement. In this article, we provide a concise overview of revision TKA outcomes in order to stimulate manufacturers, surgeons, and hospitals to improve on implant designs, surgical techniques, and care guidelines for revision TKA. We review the evidence on 5 points: aseptic survivorship, functional outcomes, patient satisfaction, quality of life (QOL), and economic impact. In addition, we compare available outcome data for revision and primary TKAs.

1. Aseptic survivorship

Fehring and colleagues12 in 2001 and Sharkey and colleagues13 in 2002 evaluated mechanisms of failure for revision TKA and reported many failures resulted from infection or were associated with the implant, and occurred within 2 years after the primary procedure. More recently, Dy and colleagues14 found the most common reason for revision was aseptic loosening, followed by infection. The present review focuses on aseptic femoral and tibial revision.

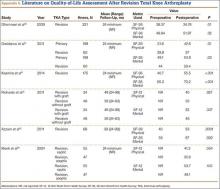

The failure rate for revision TKA is substantially higher than for primary TKA with the same type of prosthesis because of the complexity of the revision procedure, the increasing constraint of the implant design, and the higher degree of bone loss. (Appendix 1 lists risk factors for revision surgery. Appendix 2 is a complete list of survivorship outcomes of revision TKA.)

Sheng and colleagues15 in 2006 and Koskinen and colleagues16 in 2008 analyzed Finnish Arthroplasty Register data to determine failure rates for revision and primary TKA. Sheng and colleagues15 examined survivorship of 2637 revision TKAs (performed between 1990 and 2002) for all-cause endpoints after first revision procedure. Survivorship rates were 89% (5 years) and 79% (10 years), while Koskinen and colleagues16 noted all-cause survival rates of 80% at 15 years. More recently, in 2013, the New Zealand Orthopaedic Association17 analyzed New Zealand Joint Registry data for revision and re-revision rates (rates of revision per 100 component years) for 64,556 primary TKAs performed between 1999 and 2012. During the period studied, 1684 revisions were performed, reflecting a 2.6% revision rate, a 0.50% rate of revision per 100 component years, and a 13-year Kaplan-Meier survivorship of 94.5%. The most common reasons for revision were pain, deep infection, and tibial component loosening (Table 1).

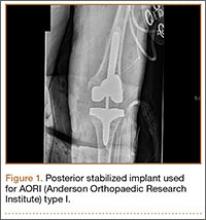

Posterior stabilized implants

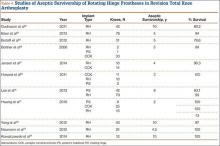

Laskin and Ohnsorge18 retrospectively reviewed the cases of 58 patients who underwent unilateral revision TKA (with a posterior stabilized implant), of which 42% were for coronal instability and 44% for a loose tibial component. At minimum 4-year follow-up, 52 of the 58 patients had anteroposterior instability of less than 5 mm. In addition, 5 years after surgery, aseptic survivorship was 96%. Meijer and colleagues19 conducted a retrospective comparative study of 69 revision TKAs (65 patients) in which 9 knees received a primary implant and 60 received a revision implant with stems and augmentation (60 = 37 posterior stabilized, 20 constrained, 3 rotating hinge). Survival rates for the primary implants were 100% (1 year), 73% (2 years), and 44% (5 years), and survival rates for the revision implants were significantly better: 95% (1 year), 92% (2 years), and 92% (5 years) (hazard ratio, 5.87; P = .008). The authors therefore indicated that it was unclear whether using a primary implant should still be an option in revision TKA and, if it is used, whether it should be limited to less complex situations in which bone loss and ligament damage are minimal (Table 2).

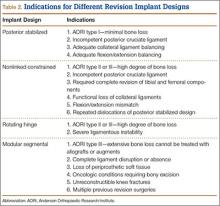

Constrained and semiconstrained implants

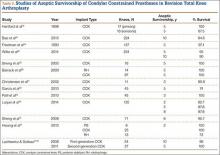

In a study of 234 knees (209 patients) with soft-tissue deficiency, Wilke and colleagues20 evaluated the long-term survivorship of revision TKA with use of a semiconstrained modular fixed-bearing implant system. Overall Kaplan-Meier survival rates were 91% (5 years) and 81% (10 years) at a mean follow-up of 9 years. When aseptic revision was evaluated, however, the survival rates increased to 95% (5 years) and 90% (10 years). The authors noted that male sex was the only variable that significantly increased the risk for re-revision (hazard ratio, 2.07; P = .02), which they attributed to potentially higher activity levels. In 2006 and 2011, Lachiewicz and Soileau21,22 evaluated the survival of first- and second-generation constrained condylar prostheses in primary TKA cases with severe valgus deformities, incompetent collateral ligaments, or severe flexion contractures. Of the 54 knees (44 patients) with first-generation prostheses, 42 (34 patients) had a mean follow-up of 9 years (range, 5-16 years). Ten-year survival with failure, defined as component revision for loosening, was 96%. The 27 TKAs using second-generation prostheses had a mean follow-up of about 5 years (range, 2-12 years). At final follow-up, there were no revisions for loosening or patellar problems, but 6 knees (22%) required lateral retinacular release of the patella (Table 3).

Rotating hinge implants

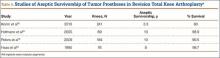

Neumann and colleagues23 evaluated the clinical and radiographic outcomes of 24 rotating hinge prostheses used for aseptic loosening with substantial bone loss and collateral ligament instability. At a mean follow-up of 56 months (range, 3-5 years), there was no evidence of loosening of any implants, and nonprogressive radiolucent lines were found in only 2 tibial components. Kowalczewski and colleagues24 evaluated the clinical and radiologic outcomes of 12 primary TKAs using a rotating hinge knee prosthesis at a minimum follow-up of 10 years. By most recent follow-up, no implants had been revised for loosening, and only 3 had nonprogressive radiolucent lines (Table 4).

Endoprostheses (modular segmental implants)

In a systematic review of 9 studies, Korim and colleagues25 evaluated 241 endoprostheses used for limb salvage under nononcologic conditions. Mean follow-up was about 3 years (range, 1-5 years). The devices were used to treat various conditions, including periprosthetic fracture, bone loss with aseptic loosening, and ligament insufficiency. The overall reoperation rate was 17% (41/241 cases). Mechanical failures were less frequent (6%-19%) (Table 5).

2. Functional outcomes

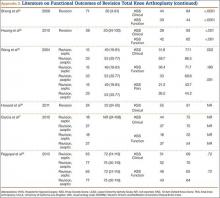

The goal in both primary and revision TKA is to restore the function and mobility of the knee and to alleviate pain. Whereas primary TKAs are realistically predictable and reproducible in their outcomes, revision TKAs are vastly more complicated, which can result in worse postoperative outcomes and function. In addition, revision TKAs may require extensive surgical exposure, which causes more tissue and muscle damage, prolonging rehabilitation. (Appendix 3 is a complete list of studies of functional outcomes of revision TKA.)

This discrepancy in functional outcomes between primary and revision TKA begins as early as the postoperative inpatient rehabilitation period. Using the functional independence measurement (FIM), which estimates performance of activities of daily living, mobility, and cognition, Vincent and colleagues26 evaluated the functional improvement produced by revision versus primary TKA during inpatient rehabilitation. They compared 424 consecutive primary TKAs with 138 revision TKAs. For both groups, FIM scores increased significantly (P = .015) between admission and discharge. On discharge, however, FIM scores were significantly (P = .01) higher for the primary group than the revision group (29 and 27 points, respectively). Furthermore, in the evaluation of mechanisms of failure, patients who had revision TKA for mechanical or pain-related problems did markedly better than those who had revision TKA for infection.

Compared with primary knee implants, revision implants require increasing constraint. We assume increasing constraint affects knee biomechanics, leading to worsening functional outcomes. In a study of 60 revision TKAs (57 patients) using posterior stabilized, condylar constrained, or rotating hinge prostheses, Vasso and colleagues27 examined functional outcomes at a median follow-up of 9 years (range, 4-12 years). At most recent follow-up, mean International Knee Society (IKS) Knee and Function scores were 81 (range, 48-97) and 79 (range, 56-92), mean Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score was 84 (range, 62-98), and mean range of motion (ROM) was 121° (range, 98°-132°) (P < .001). Although there were no significant differences in IKS and HSS scores between prosthesis types, ROM was significantly (P < .01) wider in the posterior stabilized group than in the condylar constrained and rotating hinge groups (127° vs 112° and 108°), suggesting increasing constraint resulted in decreased ROM. Several studies have found increasing constraint might lead to reduced function.28-30

However, Hwang and colleagues31 evaluated functional outcomes in 36 revision TKAs and noted that the cemented posterior stabilized (n = 8), condylar constrained (n = 25), and rotating hinge (n = 13) prostheses used did not differ in their mean Knee Society scores (78, 81, and 83, respectively).

There remains a marked disparity in patient limitations seen after revision versus primary TKA. Given the positive results being obtained with newer implants, studies might suggest recent generations of prostheses have allowed designs to be comparable. As design development continues, we may come closer to achieving outcomes comparable to those of primary TKA.

3. Patient satisfaction

Several recent reports have shown that 10% to 25% of patients who underwent primary TKA were dissatisfied with their surgery30,32; other studies have found patient satisfaction often correlating to function and pain.33-35 Given the worse outcomes for revision TKA (outlined in the preceding section), the substantial pain accompanying a second, more complex procedure, and the extensive rehabilitation expected, we suspect patients who undergo revision TKA are even less satisfied with their surgery than their primary counterparts are. (See Appendix 4 for a complete list of studies of patient satisfaction after revision TKA.)

Barrack and colleagues32 evaluated a consecutive series of 238 patients followed up for at least 1 year after revision TKA. Patients were asked to rate their degree of satisfaction with both their primary procedure and the revision and to indicate their expectations regarding their revision prosthesis. Mean satisfaction score was 7.4 (maximum = 10), with 13% of patients dissatisfied, 18% somewhat satisfied, and 69% satisfied. Seventy-four percent of patients expected their revision prosthesis to last longer than the primary prosthesis.

Greidanus and colleagues36 evaluated patient satisfaction in 60 revision TKA cases and 199 primary TKA cases at 2-year follow-up. The primary TKA group had significantly (P < .01) higher satisfaction scores in a comparison with the revision TKA group: Global (86 vs 73), Pain Relief (88 vs 70), Function (83 vs 67), and Recreation (77 vs 62). These findings support the satisfaction rates reported by Dahm and colleagues33,34: 91% for primary TKA patients and 77% for revision TKA patients.

4. Quality of life

Procedure complexity leads to reduced survivorship, function, and mobility, longer rehabilitation, and decreased QOL for revision TKA patients relative to primary TKA patients.37 (See Appendix 5 for a complete list of studies of QOL outcomes of revision TKA.)

Greidanus and colleagues36 evaluated joint-specific QOL (using the 12-item Oxford Knee Score; OKS) and generic QOL (using the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; SF-12) in 60 revision TKA cases and 199 primary TKA cases at a mean follow-up of 2 years. (The OKS survey is used to evaluate patient perspectives on TKA outcomes,38 and the multipurpose SF-12 questionnaire is used to assess mental and physical function and general health-related QOL.39) Compared with the revision TKA group, the primary TKA group had significantly higher OKS after surgery (78 vs 68; P = .01) as well as significantly higher SF-12 scores: Global (84 vs 72; P = .01), Mental (54 vs 50; P = .03), and Physical (43 vs 37; P = .01). Similarly, Ghomrawi and colleagues40 evaluated patterns of improvement in 308 patients (318 knees) who had revision TKA. At 24-month follow-up, mean SF-36 Physical and Mental scores were 35 and 52, respectively.

Deehan and colleagues41 used the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) to compare 94 patients’ health-related QOL scores before revision TKA with their scores 3 months, 1 year, and 5 years after revision. NHP Pain subscale scores were significantly lower 3 and 12 months after surgery than before surgery, but this difference was no longer seen at the 5-year follow-up. There was no significant improvement in scores on the other 5 NHP subscales (Sleep, Energy, Emotion, Mobility, Social Isolation) at any time points.

As shown in the literature, patients’ QOL outcomes improve after revision TKA, but these gains are not at the level of patients who undergo primary TKA.36,41 Given that revision surgery is more extensive, and that perhaps revision patients have poorer muscle function, they usually do not return to the level they attained after their index procedure.

5. Economic impact

Consistent with the outcomes already described, the economic impact of revision TKAs is excess expenditures and costs to patients and health care institutions.42 The sources of this impact are higher implant costs, extra operative trays and times, longer hospital stays, more rehabilitation, and increased medication use.43 Revision TKA costs range from $49,000 to more than $100,000—a tremendous increase over primary TKA costs ($25,000-$30,000).43-45 Furthermore, the annual economic burden associated with revision TKA, now $2.7 billion, is expected to exceed $13 billion by 2030.46 In the United States, about $23.2 billion will be spent on 926,527 primary TKAs in 2015; significantly, the costs associated with revising just 10% of these cases account for almost 50% of the total cost of the primary procedures.46

In a retrospective cost-identification multicenter cohort study, Bozic and colleagues47 found that both-component and single-component revisions, compared with primary procedures, were associated with significantly increased operative time (~265 and 221 minutes vs 200 minutes), use of allograft bone (23% and 14% vs 1%), length of stay (5.4 and 5.7 days vs 5.0 days), and percentage of patients discharged to extended-care facilities (26% and 26% vs 25%) (P < .0001). Hospital costs for both- and single-component revisions were 138% and 114% higher than costs for primary procedures (P < .0001). More recently, Kallala and colleagues44 analyzed UK National Health Service data and compared the costs of revision for infection with revision for other causes (pain, instability, aseptic loosening, fracture). Mean length of stay associated with revision for infection (21.5 days) was more than double that associated with revision for aseptic loosening (9.5 days; P < .0001), and mean cost of revision for septic causes (£30,011) was more than 3 times that of revision for other causes (£9655; P < .0001). The authors concluded that the higher costs of revision knee surgery have a considerable economic impact, especially in infection cases.

With more extensive procedures, long-stem or more constrained prostheses are often needed to obtain adequate fixation and stability. The resulting increased, substantial economic burden is felt by patients and the health care system. Given that health care reimbursements are declining, hospitals that perform revision TKAs can sustain marked financial losses. Some centers are asking whether it is cost-effective to continue to perform these types of procedures. We must find new ways to provide revision procedures using less costly implants and tools so that centers will continue to make these procedures available to patients.

Conclusion

Given the exponential growth in primary TKAs, there will be a concordant increase in revision TKAs in the decades to come. This review provides a concise overview of revision TKA outcomes. Given the low level of evidence regarding revision TKAs, we need further higher quality studies of their prostheses and outcomes. Specifically, we need systematic reviews and meta-analyses to provide higher quality evidence regarding outcomes of using individual prosthetic designs.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Crowninshield RD, Rosenberg AG, Sporer SM. Changing demographics of patients with total joint replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:266-272.

3. Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(5):637-647.

4. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

5. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, Zhao K, Mowat F, Lau E. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(2):195-203.

6. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(10):2606-2612.

7. Bryan RS, Rand JA. Revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;170:116-122.

8. Rand JA, Bryan RS. Revision after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;13(1):201-212.

9. Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):45-51.

10. Parvizi J, Nunley RM, Berend KR, et al. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):133-137.

11. Ali A, Sundberg M, Robertsson O, et al. Dissatisfied patients after total knee arthroplasty: a registry study involving 114 patients with 8-13 years of followup. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(3):229-233.

12. Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:315-318.

13. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

14. Dy CJ, Marx RG, Bozic KJ, Pan TJ, Padgett DE, Lyman S. Risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1198-1207.

15. Sheng PY, Konttinen L, Lehto M, et al. Revision total knee arthroplasty: 1990 through 2002. A review of the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(7):1425-1430.

16. Koskinen E, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V. Comparison of survival and cost-effectiveness between unicondylar arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis: a follow-up study of 50,493 knee replacements from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(4):499-507.

17. New Zealand Orthopaedic Association. The New Zealand Joint Registry Fourteen Year Report (January 1999 to December 2012). http://www.nzoa.org.nz/system/files/NJR%2014%20Year%20Report.pdf. Published November 2013. Accessed December 16, 2015.

18. Laskin RS, Ohnsorge J. The use of standard posterior stabilized implants in revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(440):122-125.

19. Meijer MF, Reininga IH, Boerboom AL, Stevens M, Bulstra SK. Poorer survival after a primary implant during revision total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(3):415-419.

20. Wilke BK, Wagner ER, Trousdale RT. Long-term survival of semi-constrained total knee arthroplasty for revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):1005-1008.

21. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

22. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Results of a second-generation constrained condylar prosthesis in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1228-1231.

23. Neumann DR, Hofstaedter T, Dorn U. Follow-up of a modular rotating hinge knee system in salvage revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):814-819.

24. Kowalczewski J, Marczak D, Synder M, Sibinski M. Primary rotating-hinge total knee arthroplasty: good outcomes at mid-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1202-1206.

25. Korim MT, Esler CN, Reddy VR, Ashford RU. A systematic review of endoprosthetic replacement for non-tumour indications around the knee joint. Knee. 2013;20(6):367-375.

26. Vincent KR, Vincent HK, Lee LW, Alfano AP. Inpatient rehabilitation outcomes in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;(446):201-207.

27. Vasso M, Beaufils P, Schiavone Panni A. Constraint choice in revision knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(7):1279-1284.

28. Baier C, Luring C, Schaumburger J, et al. Assessing patient-oriented results after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(6):955-961.

29. Hartford JM, Goodman SB, Schurman DJ, Knoblick G. Complex primary and revision total knee arthroplasty using the condylar constrained prosthesis: an average 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(4):380-387.

30. Haidukewych GJ, Jacofsky DJ, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT. Functional results after revision of well-fixed components for stiffness after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(2):133-138.

31. Hwang SC, Kong JY, Nam DC, et al. Revision total knee arthroplasty with a cemented posterior stabilized, condylar constrained or fully constrained prosthesis: a minimum 2-year follow-up analysis. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(2):112-120.

32. Barrack RL, McClure JT, Burak CF, Clohisy JC, Parvizi J, Sharkey P. Revision total knee arthroplasty: the patient’s perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:146-150.

33. Dahm DL, Barnes SA, Harrington JR, Berry DJ. Patient reported activity after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):106-110.

34. Dahm DL, Barnes SA, Harrington JR, Sayeed SA, Berry DJ. Patient-reported activity level after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(3):401-407.

35. Richards CJ, Garbuz DS, Pugh L, Masri BA. Revision total knee arthroplasty: clinical outcome comparison with and without the use of femoral head structural allograft. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1299-1304.

36. Greidanus NV, Peterson RC, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. Quality of life outcomes in revision versus primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(4):615-620.

37. Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(5):963-974.

38. Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, et al. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(8):1010-1014.

39. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220-233.

40. Ghomrawi HM, Kane RL, Eberly LE, Bershadsky B, Saleh KJ; North American Knee Arthroplasty Revision Study Group. Patterns of functional improvement after revision knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(12):2838-2845.

41. Deehan DJ, Murray JD, Birdsall PD, Pinder IM. Quality of life after knee revision arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(5):761-766.

42. Kapadia BH, McElroy MJ, Issa K, Johnson AJ, Bozic KJ, Mont MA. The economic impact of periprosthetic infections following total knee arthroplasty at a specialized tertiary-care center. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):929-932.

43. Bhandari M, Smith J, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical and economic burden of revision knee arthroplasty. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;5:89-94.

44. Kallala RF, Vanhegan IS, Ibrahim MS, Sarmah S, Haddad FS. Financial analysis of revision knee surgery based on NHS tariffs and hospital costs: does it pay to provide a revision service? Bone Joint J Br. 2015;97(2):197-201.

45. Ong KL, Mowat FS, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern MT, Kurtz SM. Economic burden of revision hip and knee arthroplasty in Medicare enrollees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:22-28.

46. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

47. Bozic KJ, Durbhakula S, Berry DJ, et al. Differences in patient and procedure characteristics and hospital resource use in primary and revision total joint arthroplasty: a multicenter study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 suppl 3):17-25.

48. Lee KJ, Moon JY, Song EK, Lim HA, Seon JK. Minimum Two-year Results of Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty Following Infectious or Non-infectious Causes. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012;24(4):227-234.

49. Bae DK, Song SJ, Heo DB, Lee SH, Song WJ. Long-term survival rate of implants and modes of failure after revision total knee arthroplasty by a single surgeon. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1130-1134.

50. Sheng PY, Jämsen E, Lehto MU, Konttinen YT, Pajamäki J, Halonen P. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the Total Condylar III system in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1222-1224.

51. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

52. Haas SB, Insall JN, Montgomery W 3rd, Windsor RE. Revision total knee arthroplasty with use of modular components with stems inserted without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(11):1700-1707.

53. Mabry TM, Vessely MB, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Berry DJ. Revision total knee arthroplasty with modular cemented stems: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):100-105.

54. Gudnason A, Milbrink J, Hailer NP. Implant survival and outcome after rotating-hinge total knee revision arthroplasty: a minimum 6-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(11):1601-1607.

55. Hofmann AA, Goldberg T, Tanner AM, Kurtin SM. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer: 2- to 12-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;430:125-131.

56. Greene JW, Reynolds SM, Stimac JD, Malkani AL, Massini MA. Midterm results of hybrid cement technique in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(4):570-574.

57. Dalury DF, Adams MJ. Minimum 6-year follow-up of revision total knee arthroplasty without patella reimplantation. Journal Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):91-94.

58. Whaley AL, Trousdale RT, Rand JA, Hanssen AD. Cemented long-stem revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(5):592-599.

59. Friedman RJ, Hirst P, Poss R, Kelley K, Sledge CB. Results of revision total knee arthroplasty performed for aseptic loosening. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 1990;255:235-241.

60. Barrack RL, Rorabeck C, Partington P, Sawhney J, Engh G. The results of retaining a well-fixed patellar component in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(4):413-417.

61. Christensen CP, Crawford JJ, Olin MD, Vail TP. Revision of the stiff total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(4):409-415.

62. Garcia RM, Hardy BT, Kraay MJ, Goldberg VM. Revision total knee arthroplasty for aseptic and septic causes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):82-89.

63. Patil N, Lee K, Huddleston JI, Harris AH, Goodman SB. Aseptic versus septic revision total knee arthroplasty: patient satisfaction, outcome and quality of life improvement. Knee. 2010;17(3):200-203.

64. Luque R, Rizo B, Urda A, et al. Predictive factors for failure after total knee replacement revision. Int Orthop. 2014;38(2):429-435.

65. Bistolfi A, Massazza G, Rosso F, Crova M. Rotating-hinge total knee for revision total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2012;35(3):e325-e330.

66. Bottner F, Laskin R, Windsor RE, Haas SB. Hybrid component fixation in revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:127-131.

67. Jensen CL, Winther N, Schroder HM, Petersen MM. Outcome of revision total knee arthroplasty with the use of trabecular metal cone for reconstruction of severe bone loss at the proximal tibia. Knee. 2014;21(6):1233-1237.

68. Howard JL, Kudera J, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD. Early results of the use of tantalum femoral cones for revision total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(5):478-484.

69. Yang JH, Yoon JR, Oh CH, Kim TS. Hybrid component fixation in total knee arthroplasty: minimum of 10-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1111-1118.

70. Peters CL, Erickson JA, Gililland JM. Clinical and radiographic results of 184 consecutive revision total knee arthroplasties placed with modular cementless stems. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):48-53.

71. Registry AOANJR. Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Annual Report 2014. 2014.

72. Registry AOANJR. Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. Annual Report 2013. 2013.

Over the past 3 decades, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been considered a safe and effective treatment for end-stage knee arthritis.1 However, as the population, the incidence of obesity, and life expectancy continue to increase, the number of TKAs will rise as well.2,3 It is expected that over the next 16 years, the number of TKAs performed annually will exceed 3 million in the United States alone.4 This projection represents an over 600% increase from 2005 figures.5 Given the demographic shift expected over the next 2 decades, patients are anticipated to undergo these procedures at younger ages compared with previous generations, such that those age 65 years or younger will account for more than 55% of primary TKAs.6 More important, given this exponential growth in primary TKAs, there will be a concordant rise in revision procedures. It is expected that, the annual number has roughly doubled from that recorded for 2005.4

Compared with primary TKAs, however, revision TKAs have had less promising results, with survivorship as low as 60% over shorter periods.7,8 In addition, recent studies have found an even higher degree of dissatisfaction and functional limitations among revision TKA patients than among primary TKA patients, 15% to 30% of whom are unhappy with their procedures.9-11 These shortcomings of revision TKAs are thought to result from several factors, including poor bone quality, insufficient bone stock, ligamentous instability, soft-tissue incompetence, infection, malalignment, problems with extensor mechanisms, and substantial pain of uncertain etiology.

Despite there being several complex factors that can lead to worse outcomes with revision TKAs, surgeons are expected to produce results equivalent to those of primary TKAs. It is therefore imperative to delineate the objective and subjective outcomes of revision techniques to identify areas in need of improvement. In this article, we provide a concise overview of revision TKA outcomes in order to stimulate manufacturers, surgeons, and hospitals to improve on implant designs, surgical techniques, and care guidelines for revision TKA. We review the evidence on 5 points: aseptic survivorship, functional outcomes, patient satisfaction, quality of life (QOL), and economic impact. In addition, we compare available outcome data for revision and primary TKAs.

1. Aseptic survivorship

Fehring and colleagues12 in 2001 and Sharkey and colleagues13 in 2002 evaluated mechanisms of failure for revision TKA and reported many failures resulted from infection or were associated with the implant, and occurred within 2 years after the primary procedure. More recently, Dy and colleagues14 found the most common reason for revision was aseptic loosening, followed by infection. The present review focuses on aseptic femoral and tibial revision.

The failure rate for revision TKA is substantially higher than for primary TKA with the same type of prosthesis because of the complexity of the revision procedure, the increasing constraint of the implant design, and the higher degree of bone loss. (Appendix 1 lists risk factors for revision surgery. Appendix 2 is a complete list of survivorship outcomes of revision TKA.)

Sheng and colleagues15 in 2006 and Koskinen and colleagues16 in 2008 analyzed Finnish Arthroplasty Register data to determine failure rates for revision and primary TKA. Sheng and colleagues15 examined survivorship of 2637 revision TKAs (performed between 1990 and 2002) for all-cause endpoints after first revision procedure. Survivorship rates were 89% (5 years) and 79% (10 years), while Koskinen and colleagues16 noted all-cause survival rates of 80% at 15 years. More recently, in 2013, the New Zealand Orthopaedic Association17 analyzed New Zealand Joint Registry data for revision and re-revision rates (rates of revision per 100 component years) for 64,556 primary TKAs performed between 1999 and 2012. During the period studied, 1684 revisions were performed, reflecting a 2.6% revision rate, a 0.50% rate of revision per 100 component years, and a 13-year Kaplan-Meier survivorship of 94.5%. The most common reasons for revision were pain, deep infection, and tibial component loosening (Table 1).

Posterior stabilized implants

Laskin and Ohnsorge18 retrospectively reviewed the cases of 58 patients who underwent unilateral revision TKA (with a posterior stabilized implant), of which 42% were for coronal instability and 44% for a loose tibial component. At minimum 4-year follow-up, 52 of the 58 patients had anteroposterior instability of less than 5 mm. In addition, 5 years after surgery, aseptic survivorship was 96%. Meijer and colleagues19 conducted a retrospective comparative study of 69 revision TKAs (65 patients) in which 9 knees received a primary implant and 60 received a revision implant with stems and augmentation (60 = 37 posterior stabilized, 20 constrained, 3 rotating hinge). Survival rates for the primary implants were 100% (1 year), 73% (2 years), and 44% (5 years), and survival rates for the revision implants were significantly better: 95% (1 year), 92% (2 years), and 92% (5 years) (hazard ratio, 5.87; P = .008). The authors therefore indicated that it was unclear whether using a primary implant should still be an option in revision TKA and, if it is used, whether it should be limited to less complex situations in which bone loss and ligament damage are minimal (Table 2).

Constrained and semiconstrained implants

In a study of 234 knees (209 patients) with soft-tissue deficiency, Wilke and colleagues20 evaluated the long-term survivorship of revision TKA with use of a semiconstrained modular fixed-bearing implant system. Overall Kaplan-Meier survival rates were 91% (5 years) and 81% (10 years) at a mean follow-up of 9 years. When aseptic revision was evaluated, however, the survival rates increased to 95% (5 years) and 90% (10 years). The authors noted that male sex was the only variable that significantly increased the risk for re-revision (hazard ratio, 2.07; P = .02), which they attributed to potentially higher activity levels. In 2006 and 2011, Lachiewicz and Soileau21,22 evaluated the survival of first- and second-generation constrained condylar prostheses in primary TKA cases with severe valgus deformities, incompetent collateral ligaments, or severe flexion contractures. Of the 54 knees (44 patients) with first-generation prostheses, 42 (34 patients) had a mean follow-up of 9 years (range, 5-16 years). Ten-year survival with failure, defined as component revision for loosening, was 96%. The 27 TKAs using second-generation prostheses had a mean follow-up of about 5 years (range, 2-12 years). At final follow-up, there were no revisions for loosening or patellar problems, but 6 knees (22%) required lateral retinacular release of the patella (Table 3).

Rotating hinge implants

Neumann and colleagues23 evaluated the clinical and radiographic outcomes of 24 rotating hinge prostheses used for aseptic loosening with substantial bone loss and collateral ligament instability. At a mean follow-up of 56 months (range, 3-5 years), there was no evidence of loosening of any implants, and nonprogressive radiolucent lines were found in only 2 tibial components. Kowalczewski and colleagues24 evaluated the clinical and radiologic outcomes of 12 primary TKAs using a rotating hinge knee prosthesis at a minimum follow-up of 10 years. By most recent follow-up, no implants had been revised for loosening, and only 3 had nonprogressive radiolucent lines (Table 4).

Endoprostheses (modular segmental implants)

In a systematic review of 9 studies, Korim and colleagues25 evaluated 241 endoprostheses used for limb salvage under nononcologic conditions. Mean follow-up was about 3 years (range, 1-5 years). The devices were used to treat various conditions, including periprosthetic fracture, bone loss with aseptic loosening, and ligament insufficiency. The overall reoperation rate was 17% (41/241 cases). Mechanical failures were less frequent (6%-19%) (Table 5).

2. Functional outcomes

The goal in both primary and revision TKA is to restore the function and mobility of the knee and to alleviate pain. Whereas primary TKAs are realistically predictable and reproducible in their outcomes, revision TKAs are vastly more complicated, which can result in worse postoperative outcomes and function. In addition, revision TKAs may require extensive surgical exposure, which causes more tissue and muscle damage, prolonging rehabilitation. (Appendix 3 is a complete list of studies of functional outcomes of revision TKA.)

This discrepancy in functional outcomes between primary and revision TKA begins as early as the postoperative inpatient rehabilitation period. Using the functional independence measurement (FIM), which estimates performance of activities of daily living, mobility, and cognition, Vincent and colleagues26 evaluated the functional improvement produced by revision versus primary TKA during inpatient rehabilitation. They compared 424 consecutive primary TKAs with 138 revision TKAs. For both groups, FIM scores increased significantly (P = .015) between admission and discharge. On discharge, however, FIM scores were significantly (P = .01) higher for the primary group than the revision group (29 and 27 points, respectively). Furthermore, in the evaluation of mechanisms of failure, patients who had revision TKA for mechanical or pain-related problems did markedly better than those who had revision TKA for infection.

Compared with primary knee implants, revision implants require increasing constraint. We assume increasing constraint affects knee biomechanics, leading to worsening functional outcomes. In a study of 60 revision TKAs (57 patients) using posterior stabilized, condylar constrained, or rotating hinge prostheses, Vasso and colleagues27 examined functional outcomes at a median follow-up of 9 years (range, 4-12 years). At most recent follow-up, mean International Knee Society (IKS) Knee and Function scores were 81 (range, 48-97) and 79 (range, 56-92), mean Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score was 84 (range, 62-98), and mean range of motion (ROM) was 121° (range, 98°-132°) (P < .001). Although there were no significant differences in IKS and HSS scores between prosthesis types, ROM was significantly (P < .01) wider in the posterior stabilized group than in the condylar constrained and rotating hinge groups (127° vs 112° and 108°), suggesting increasing constraint resulted in decreased ROM. Several studies have found increasing constraint might lead to reduced function.28-30

However, Hwang and colleagues31 evaluated functional outcomes in 36 revision TKAs and noted that the cemented posterior stabilized (n = 8), condylar constrained (n = 25), and rotating hinge (n = 13) prostheses used did not differ in their mean Knee Society scores (78, 81, and 83, respectively).

There remains a marked disparity in patient limitations seen after revision versus primary TKA. Given the positive results being obtained with newer implants, studies might suggest recent generations of prostheses have allowed designs to be comparable. As design development continues, we may come closer to achieving outcomes comparable to those of primary TKA.

3. Patient satisfaction

Several recent reports have shown that 10% to 25% of patients who underwent primary TKA were dissatisfied with their surgery30,32; other studies have found patient satisfaction often correlating to function and pain.33-35 Given the worse outcomes for revision TKA (outlined in the preceding section), the substantial pain accompanying a second, more complex procedure, and the extensive rehabilitation expected, we suspect patients who undergo revision TKA are even less satisfied with their surgery than their primary counterparts are. (See Appendix 4 for a complete list of studies of patient satisfaction after revision TKA.)

Barrack and colleagues32 evaluated a consecutive series of 238 patients followed up for at least 1 year after revision TKA. Patients were asked to rate their degree of satisfaction with both their primary procedure and the revision and to indicate their expectations regarding their revision prosthesis. Mean satisfaction score was 7.4 (maximum = 10), with 13% of patients dissatisfied, 18% somewhat satisfied, and 69% satisfied. Seventy-four percent of patients expected their revision prosthesis to last longer than the primary prosthesis.

Greidanus and colleagues36 evaluated patient satisfaction in 60 revision TKA cases and 199 primary TKA cases at 2-year follow-up. The primary TKA group had significantly (P < .01) higher satisfaction scores in a comparison with the revision TKA group: Global (86 vs 73), Pain Relief (88 vs 70), Function (83 vs 67), and Recreation (77 vs 62). These findings support the satisfaction rates reported by Dahm and colleagues33,34: 91% for primary TKA patients and 77% for revision TKA patients.

4. Quality of life

Procedure complexity leads to reduced survivorship, function, and mobility, longer rehabilitation, and decreased QOL for revision TKA patients relative to primary TKA patients.37 (See Appendix 5 for a complete list of studies of QOL outcomes of revision TKA.)

Greidanus and colleagues36 evaluated joint-specific QOL (using the 12-item Oxford Knee Score; OKS) and generic QOL (using the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; SF-12) in 60 revision TKA cases and 199 primary TKA cases at a mean follow-up of 2 years. (The OKS survey is used to evaluate patient perspectives on TKA outcomes,38 and the multipurpose SF-12 questionnaire is used to assess mental and physical function and general health-related QOL.39) Compared with the revision TKA group, the primary TKA group had significantly higher OKS after surgery (78 vs 68; P = .01) as well as significantly higher SF-12 scores: Global (84 vs 72; P = .01), Mental (54 vs 50; P = .03), and Physical (43 vs 37; P = .01). Similarly, Ghomrawi and colleagues40 evaluated patterns of improvement in 308 patients (318 knees) who had revision TKA. At 24-month follow-up, mean SF-36 Physical and Mental scores were 35 and 52, respectively.

Deehan and colleagues41 used the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) to compare 94 patients’ health-related QOL scores before revision TKA with their scores 3 months, 1 year, and 5 years after revision. NHP Pain subscale scores were significantly lower 3 and 12 months after surgery than before surgery, but this difference was no longer seen at the 5-year follow-up. There was no significant improvement in scores on the other 5 NHP subscales (Sleep, Energy, Emotion, Mobility, Social Isolation) at any time points.

As shown in the literature, patients’ QOL outcomes improve after revision TKA, but these gains are not at the level of patients who undergo primary TKA.36,41 Given that revision surgery is more extensive, and that perhaps revision patients have poorer muscle function, they usually do not return to the level they attained after their index procedure.

5. Economic impact

Consistent with the outcomes already described, the economic impact of revision TKAs is excess expenditures and costs to patients and health care institutions.42 The sources of this impact are higher implant costs, extra operative trays and times, longer hospital stays, more rehabilitation, and increased medication use.43 Revision TKA costs range from $49,000 to more than $100,000—a tremendous increase over primary TKA costs ($25,000-$30,000).43-45 Furthermore, the annual economic burden associated with revision TKA, now $2.7 billion, is expected to exceed $13 billion by 2030.46 In the United States, about $23.2 billion will be spent on 926,527 primary TKAs in 2015; significantly, the costs associated with revising just 10% of these cases account for almost 50% of the total cost of the primary procedures.46

In a retrospective cost-identification multicenter cohort study, Bozic and colleagues47 found that both-component and single-component revisions, compared with primary procedures, were associated with significantly increased operative time (~265 and 221 minutes vs 200 minutes), use of allograft bone (23% and 14% vs 1%), length of stay (5.4 and 5.7 days vs 5.0 days), and percentage of patients discharged to extended-care facilities (26% and 26% vs 25%) (P < .0001). Hospital costs for both- and single-component revisions were 138% and 114% higher than costs for primary procedures (P < .0001). More recently, Kallala and colleagues44 analyzed UK National Health Service data and compared the costs of revision for infection with revision for other causes (pain, instability, aseptic loosening, fracture). Mean length of stay associated with revision for infection (21.5 days) was more than double that associated with revision for aseptic loosening (9.5 days; P < .0001), and mean cost of revision for septic causes (£30,011) was more than 3 times that of revision for other causes (£9655; P < .0001). The authors concluded that the higher costs of revision knee surgery have a considerable economic impact, especially in infection cases.

With more extensive procedures, long-stem or more constrained prostheses are often needed to obtain adequate fixation and stability. The resulting increased, substantial economic burden is felt by patients and the health care system. Given that health care reimbursements are declining, hospitals that perform revision TKAs can sustain marked financial losses. Some centers are asking whether it is cost-effective to continue to perform these types of procedures. We must find new ways to provide revision procedures using less costly implants and tools so that centers will continue to make these procedures available to patients.

Conclusion

Given the exponential growth in primary TKAs, there will be a concordant increase in revision TKAs in the decades to come. This review provides a concise overview of revision TKA outcomes. Given the low level of evidence regarding revision TKAs, we need further higher quality studies of their prostheses and outcomes. Specifically, we need systematic reviews and meta-analyses to provide higher quality evidence regarding outcomes of using individual prosthetic designs.

Over the past 3 decades, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been considered a safe and effective treatment for end-stage knee arthritis.1 However, as the population, the incidence of obesity, and life expectancy continue to increase, the number of TKAs will rise as well.2,3 It is expected that over the next 16 years, the number of TKAs performed annually will exceed 3 million in the United States alone.4 This projection represents an over 600% increase from 2005 figures.5 Given the demographic shift expected over the next 2 decades, patients are anticipated to undergo these procedures at younger ages compared with previous generations, such that those age 65 years or younger will account for more than 55% of primary TKAs.6 More important, given this exponential growth in primary TKAs, there will be a concordant rise in revision procedures. It is expected that, the annual number has roughly doubled from that recorded for 2005.4

Compared with primary TKAs, however, revision TKAs have had less promising results, with survivorship as low as 60% over shorter periods.7,8 In addition, recent studies have found an even higher degree of dissatisfaction and functional limitations among revision TKA patients than among primary TKA patients, 15% to 30% of whom are unhappy with their procedures.9-11 These shortcomings of revision TKAs are thought to result from several factors, including poor bone quality, insufficient bone stock, ligamentous instability, soft-tissue incompetence, infection, malalignment, problems with extensor mechanisms, and substantial pain of uncertain etiology.

Despite there being several complex factors that can lead to worse outcomes with revision TKAs, surgeons are expected to produce results equivalent to those of primary TKAs. It is therefore imperative to delineate the objective and subjective outcomes of revision techniques to identify areas in need of improvement. In this article, we provide a concise overview of revision TKA outcomes in order to stimulate manufacturers, surgeons, and hospitals to improve on implant designs, surgical techniques, and care guidelines for revision TKA. We review the evidence on 5 points: aseptic survivorship, functional outcomes, patient satisfaction, quality of life (QOL), and economic impact. In addition, we compare available outcome data for revision and primary TKAs.

1. Aseptic survivorship

Fehring and colleagues12 in 2001 and Sharkey and colleagues13 in 2002 evaluated mechanisms of failure for revision TKA and reported many failures resulted from infection or were associated with the implant, and occurred within 2 years after the primary procedure. More recently, Dy and colleagues14 found the most common reason for revision was aseptic loosening, followed by infection. The present review focuses on aseptic femoral and tibial revision.

The failure rate for revision TKA is substantially higher than for primary TKA with the same type of prosthesis because of the complexity of the revision procedure, the increasing constraint of the implant design, and the higher degree of bone loss. (Appendix 1 lists risk factors for revision surgery. Appendix 2 is a complete list of survivorship outcomes of revision TKA.)

Sheng and colleagues15 in 2006 and Koskinen and colleagues16 in 2008 analyzed Finnish Arthroplasty Register data to determine failure rates for revision and primary TKA. Sheng and colleagues15 examined survivorship of 2637 revision TKAs (performed between 1990 and 2002) for all-cause endpoints after first revision procedure. Survivorship rates were 89% (5 years) and 79% (10 years), while Koskinen and colleagues16 noted all-cause survival rates of 80% at 15 years. More recently, in 2013, the New Zealand Orthopaedic Association17 analyzed New Zealand Joint Registry data for revision and re-revision rates (rates of revision per 100 component years) for 64,556 primary TKAs performed between 1999 and 2012. During the period studied, 1684 revisions were performed, reflecting a 2.6% revision rate, a 0.50% rate of revision per 100 component years, and a 13-year Kaplan-Meier survivorship of 94.5%. The most common reasons for revision were pain, deep infection, and tibial component loosening (Table 1).

Posterior stabilized implants

Laskin and Ohnsorge18 retrospectively reviewed the cases of 58 patients who underwent unilateral revision TKA (with a posterior stabilized implant), of which 42% were for coronal instability and 44% for a loose tibial component. At minimum 4-year follow-up, 52 of the 58 patients had anteroposterior instability of less than 5 mm. In addition, 5 years after surgery, aseptic survivorship was 96%. Meijer and colleagues19 conducted a retrospective comparative study of 69 revision TKAs (65 patients) in which 9 knees received a primary implant and 60 received a revision implant with stems and augmentation (60 = 37 posterior stabilized, 20 constrained, 3 rotating hinge). Survival rates for the primary implants were 100% (1 year), 73% (2 years), and 44% (5 years), and survival rates for the revision implants were significantly better: 95% (1 year), 92% (2 years), and 92% (5 years) (hazard ratio, 5.87; P = .008). The authors therefore indicated that it was unclear whether using a primary implant should still be an option in revision TKA and, if it is used, whether it should be limited to less complex situations in which bone loss and ligament damage are minimal (Table 2).

Constrained and semiconstrained implants

In a study of 234 knees (209 patients) with soft-tissue deficiency, Wilke and colleagues20 evaluated the long-term survivorship of revision TKA with use of a semiconstrained modular fixed-bearing implant system. Overall Kaplan-Meier survival rates were 91% (5 years) and 81% (10 years) at a mean follow-up of 9 years. When aseptic revision was evaluated, however, the survival rates increased to 95% (5 years) and 90% (10 years). The authors noted that male sex was the only variable that significantly increased the risk for re-revision (hazard ratio, 2.07; P = .02), which they attributed to potentially higher activity levels. In 2006 and 2011, Lachiewicz and Soileau21,22 evaluated the survival of first- and second-generation constrained condylar prostheses in primary TKA cases with severe valgus deformities, incompetent collateral ligaments, or severe flexion contractures. Of the 54 knees (44 patients) with first-generation prostheses, 42 (34 patients) had a mean follow-up of 9 years (range, 5-16 years). Ten-year survival with failure, defined as component revision for loosening, was 96%. The 27 TKAs using second-generation prostheses had a mean follow-up of about 5 years (range, 2-12 years). At final follow-up, there were no revisions for loosening or patellar problems, but 6 knees (22%) required lateral retinacular release of the patella (Table 3).

Rotating hinge implants

Neumann and colleagues23 evaluated the clinical and radiographic outcomes of 24 rotating hinge prostheses used for aseptic loosening with substantial bone loss and collateral ligament instability. At a mean follow-up of 56 months (range, 3-5 years), there was no evidence of loosening of any implants, and nonprogressive radiolucent lines were found in only 2 tibial components. Kowalczewski and colleagues24 evaluated the clinical and radiologic outcomes of 12 primary TKAs using a rotating hinge knee prosthesis at a minimum follow-up of 10 years. By most recent follow-up, no implants had been revised for loosening, and only 3 had nonprogressive radiolucent lines (Table 4).

Endoprostheses (modular segmental implants)

In a systematic review of 9 studies, Korim and colleagues25 evaluated 241 endoprostheses used for limb salvage under nononcologic conditions. Mean follow-up was about 3 years (range, 1-5 years). The devices were used to treat various conditions, including periprosthetic fracture, bone loss with aseptic loosening, and ligament insufficiency. The overall reoperation rate was 17% (41/241 cases). Mechanical failures were less frequent (6%-19%) (Table 5).

2. Functional outcomes

The goal in both primary and revision TKA is to restore the function and mobility of the knee and to alleviate pain. Whereas primary TKAs are realistically predictable and reproducible in their outcomes, revision TKAs are vastly more complicated, which can result in worse postoperative outcomes and function. In addition, revision TKAs may require extensive surgical exposure, which causes more tissue and muscle damage, prolonging rehabilitation. (Appendix 3 is a complete list of studies of functional outcomes of revision TKA.)

This discrepancy in functional outcomes between primary and revision TKA begins as early as the postoperative inpatient rehabilitation period. Using the functional independence measurement (FIM), which estimates performance of activities of daily living, mobility, and cognition, Vincent and colleagues26 evaluated the functional improvement produced by revision versus primary TKA during inpatient rehabilitation. They compared 424 consecutive primary TKAs with 138 revision TKAs. For both groups, FIM scores increased significantly (P = .015) between admission and discharge. On discharge, however, FIM scores were significantly (P = .01) higher for the primary group than the revision group (29 and 27 points, respectively). Furthermore, in the evaluation of mechanisms of failure, patients who had revision TKA for mechanical or pain-related problems did markedly better than those who had revision TKA for infection.

Compared with primary knee implants, revision implants require increasing constraint. We assume increasing constraint affects knee biomechanics, leading to worsening functional outcomes. In a study of 60 revision TKAs (57 patients) using posterior stabilized, condylar constrained, or rotating hinge prostheses, Vasso and colleagues27 examined functional outcomes at a median follow-up of 9 years (range, 4-12 years). At most recent follow-up, mean International Knee Society (IKS) Knee and Function scores were 81 (range, 48-97) and 79 (range, 56-92), mean Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) score was 84 (range, 62-98), and mean range of motion (ROM) was 121° (range, 98°-132°) (P < .001). Although there were no significant differences in IKS and HSS scores between prosthesis types, ROM was significantly (P < .01) wider in the posterior stabilized group than in the condylar constrained and rotating hinge groups (127° vs 112° and 108°), suggesting increasing constraint resulted in decreased ROM. Several studies have found increasing constraint might lead to reduced function.28-30

However, Hwang and colleagues31 evaluated functional outcomes in 36 revision TKAs and noted that the cemented posterior stabilized (n = 8), condylar constrained (n = 25), and rotating hinge (n = 13) prostheses used did not differ in their mean Knee Society scores (78, 81, and 83, respectively).

There remains a marked disparity in patient limitations seen after revision versus primary TKA. Given the positive results being obtained with newer implants, studies might suggest recent generations of prostheses have allowed designs to be comparable. As design development continues, we may come closer to achieving outcomes comparable to those of primary TKA.

3. Patient satisfaction

Several recent reports have shown that 10% to 25% of patients who underwent primary TKA were dissatisfied with their surgery30,32; other studies have found patient satisfaction often correlating to function and pain.33-35 Given the worse outcomes for revision TKA (outlined in the preceding section), the substantial pain accompanying a second, more complex procedure, and the extensive rehabilitation expected, we suspect patients who undergo revision TKA are even less satisfied with their surgery than their primary counterparts are. (See Appendix 4 for a complete list of studies of patient satisfaction after revision TKA.)

Barrack and colleagues32 evaluated a consecutive series of 238 patients followed up for at least 1 year after revision TKA. Patients were asked to rate their degree of satisfaction with both their primary procedure and the revision and to indicate their expectations regarding their revision prosthesis. Mean satisfaction score was 7.4 (maximum = 10), with 13% of patients dissatisfied, 18% somewhat satisfied, and 69% satisfied. Seventy-four percent of patients expected their revision prosthesis to last longer than the primary prosthesis.

Greidanus and colleagues36 evaluated patient satisfaction in 60 revision TKA cases and 199 primary TKA cases at 2-year follow-up. The primary TKA group had significantly (P < .01) higher satisfaction scores in a comparison with the revision TKA group: Global (86 vs 73), Pain Relief (88 vs 70), Function (83 vs 67), and Recreation (77 vs 62). These findings support the satisfaction rates reported by Dahm and colleagues33,34: 91% for primary TKA patients and 77% for revision TKA patients.

4. Quality of life

Procedure complexity leads to reduced survivorship, function, and mobility, longer rehabilitation, and decreased QOL for revision TKA patients relative to primary TKA patients.37 (See Appendix 5 for a complete list of studies of QOL outcomes of revision TKA.)

Greidanus and colleagues36 evaluated joint-specific QOL (using the 12-item Oxford Knee Score; OKS) and generic QOL (using the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; SF-12) in 60 revision TKA cases and 199 primary TKA cases at a mean follow-up of 2 years. (The OKS survey is used to evaluate patient perspectives on TKA outcomes,38 and the multipurpose SF-12 questionnaire is used to assess mental and physical function and general health-related QOL.39) Compared with the revision TKA group, the primary TKA group had significantly higher OKS after surgery (78 vs 68; P = .01) as well as significantly higher SF-12 scores: Global (84 vs 72; P = .01), Mental (54 vs 50; P = .03), and Physical (43 vs 37; P = .01). Similarly, Ghomrawi and colleagues40 evaluated patterns of improvement in 308 patients (318 knees) who had revision TKA. At 24-month follow-up, mean SF-36 Physical and Mental scores were 35 and 52, respectively.

Deehan and colleagues41 used the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) to compare 94 patients’ health-related QOL scores before revision TKA with their scores 3 months, 1 year, and 5 years after revision. NHP Pain subscale scores were significantly lower 3 and 12 months after surgery than before surgery, but this difference was no longer seen at the 5-year follow-up. There was no significant improvement in scores on the other 5 NHP subscales (Sleep, Energy, Emotion, Mobility, Social Isolation) at any time points.

As shown in the literature, patients’ QOL outcomes improve after revision TKA, but these gains are not at the level of patients who undergo primary TKA.36,41 Given that revision surgery is more extensive, and that perhaps revision patients have poorer muscle function, they usually do not return to the level they attained after their index procedure.

5. Economic impact

Consistent with the outcomes already described, the economic impact of revision TKAs is excess expenditures and costs to patients and health care institutions.42 The sources of this impact are higher implant costs, extra operative trays and times, longer hospital stays, more rehabilitation, and increased medication use.43 Revision TKA costs range from $49,000 to more than $100,000—a tremendous increase over primary TKA costs ($25,000-$30,000).43-45 Furthermore, the annual economic burden associated with revision TKA, now $2.7 billion, is expected to exceed $13 billion by 2030.46 In the United States, about $23.2 billion will be spent on 926,527 primary TKAs in 2015; significantly, the costs associated with revising just 10% of these cases account for almost 50% of the total cost of the primary procedures.46

In a retrospective cost-identification multicenter cohort study, Bozic and colleagues47 found that both-component and single-component revisions, compared with primary procedures, were associated with significantly increased operative time (~265 and 221 minutes vs 200 minutes), use of allograft bone (23% and 14% vs 1%), length of stay (5.4 and 5.7 days vs 5.0 days), and percentage of patients discharged to extended-care facilities (26% and 26% vs 25%) (P < .0001). Hospital costs for both- and single-component revisions were 138% and 114% higher than costs for primary procedures (P < .0001). More recently, Kallala and colleagues44 analyzed UK National Health Service data and compared the costs of revision for infection with revision for other causes (pain, instability, aseptic loosening, fracture). Mean length of stay associated with revision for infection (21.5 days) was more than double that associated with revision for aseptic loosening (9.5 days; P < .0001), and mean cost of revision for septic causes (£30,011) was more than 3 times that of revision for other causes (£9655; P < .0001). The authors concluded that the higher costs of revision knee surgery have a considerable economic impact, especially in infection cases.

With more extensive procedures, long-stem or more constrained prostheses are often needed to obtain adequate fixation and stability. The resulting increased, substantial economic burden is felt by patients and the health care system. Given that health care reimbursements are declining, hospitals that perform revision TKAs can sustain marked financial losses. Some centers are asking whether it is cost-effective to continue to perform these types of procedures. We must find new ways to provide revision procedures using less costly implants and tools so that centers will continue to make these procedures available to patients.

Conclusion

Given the exponential growth in primary TKAs, there will be a concordant increase in revision TKAs in the decades to come. This review provides a concise overview of revision TKA outcomes. Given the low level of evidence regarding revision TKAs, we need further higher quality studies of their prostheses and outcomes. Specifically, we need systematic reviews and meta-analyses to provide higher quality evidence regarding outcomes of using individual prosthetic designs.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Crowninshield RD, Rosenberg AG, Sporer SM. Changing demographics of patients with total joint replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:266-272.

3. Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(5):637-647.

4. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

5. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, Zhao K, Mowat F, Lau E. Primary and revision arthroplasty surgery caseloads in the United States from 1990 to 2004. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(2):195-203.

6. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(10):2606-2612.

7. Bryan RS, Rand JA. Revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;170:116-122.

8. Rand JA, Bryan RS. Revision after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;13(1):201-212.

9. Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):45-51.

10. Parvizi J, Nunley RM, Berend KR, et al. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(1):133-137.

11. Ali A, Sundberg M, Robertsson O, et al. Dissatisfied patients after total knee arthroplasty: a registry study involving 114 patients with 8-13 years of followup. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(3):229-233.

12. Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:315-318.

13. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

14. Dy CJ, Marx RG, Bozic KJ, Pan TJ, Padgett DE, Lyman S. Risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1198-1207.

15. Sheng PY, Konttinen L, Lehto M, et al. Revision total knee arthroplasty: 1990 through 2002. A review of the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(7):1425-1430.

16. Koskinen E, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V. Comparison of survival and cost-effectiveness between unicondylar arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis: a follow-up study of 50,493 knee replacements from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(4):499-507.

17. New Zealand Orthopaedic Association. The New Zealand Joint Registry Fourteen Year Report (January 1999 to December 2012). http://www.nzoa.org.nz/system/files/NJR%2014%20Year%20Report.pdf. Published November 2013. Accessed December 16, 2015.

18. Laskin RS, Ohnsorge J. The use of standard posterior stabilized implants in revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(440):122-125.

19. Meijer MF, Reininga IH, Boerboom AL, Stevens M, Bulstra SK. Poorer survival after a primary implant during revision total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(3):415-419.

20. Wilke BK, Wagner ER, Trousdale RT. Long-term survival of semi-constrained total knee arthroplasty for revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):1005-1008.

21. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

22. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Results of a second-generation constrained condylar prosthesis in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1228-1231.

23. Neumann DR, Hofstaedter T, Dorn U. Follow-up of a modular rotating hinge knee system in salvage revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(5):814-819.

24. Kowalczewski J, Marczak D, Synder M, Sibinski M. Primary rotating-hinge total knee arthroplasty: good outcomes at mid-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1202-1206.

25. Korim MT, Esler CN, Reddy VR, Ashford RU. A systematic review of endoprosthetic replacement for non-tumour indications around the knee joint. Knee. 2013;20(6):367-375.

26. Vincent KR, Vincent HK, Lee LW, Alfano AP. Inpatient rehabilitation outcomes in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;(446):201-207.

27. Vasso M, Beaufils P, Schiavone Panni A. Constraint choice in revision knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(7):1279-1284.

28. Baier C, Luring C, Schaumburger J, et al. Assessing patient-oriented results after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sci. 2013;18(6):955-961.

29. Hartford JM, Goodman SB, Schurman DJ, Knoblick G. Complex primary and revision total knee arthroplasty using the condylar constrained prosthesis: an average 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(4):380-387.

30. Haidukewych GJ, Jacofsky DJ, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT. Functional results after revision of well-fixed components for stiffness after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(2):133-138.

31. Hwang SC, Kong JY, Nam DC, et al. Revision total knee arthroplasty with a cemented posterior stabilized, condylar constrained or fully constrained prosthesis: a minimum 2-year follow-up analysis. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(2):112-120.

32. Barrack RL, McClure JT, Burak CF, Clohisy JC, Parvizi J, Sharkey P. Revision total knee arthroplasty: the patient’s perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:146-150.

33. Dahm DL, Barnes SA, Harrington JR, Berry DJ. Patient reported activity after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):106-110.

34. Dahm DL, Barnes SA, Harrington JR, Sayeed SA, Berry DJ. Patient-reported activity level after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(3):401-407.

35. Richards CJ, Garbuz DS, Pugh L, Masri BA. Revision total knee arthroplasty: clinical outcome comparison with and without the use of femoral head structural allograft. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1299-1304.

36. Greidanus NV, Peterson RC, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. Quality of life outcomes in revision versus primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(4):615-620.

37. Ethgen O, Bruyere O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(5):963-974.

38. Murray DW, Fitzpatrick R, Rogers K, et al. The use of the Oxford hip and knee scores. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(8):1010-1014.

39. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220-233.

40. Ghomrawi HM, Kane RL, Eberly LE, Bershadsky B, Saleh KJ; North American Knee Arthroplasty Revision Study Group. Patterns of functional improvement after revision knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(12):2838-2845.

41. Deehan DJ, Murray JD, Birdsall PD, Pinder IM. Quality of life after knee revision arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(5):761-766.

42. Kapadia BH, McElroy MJ, Issa K, Johnson AJ, Bozic KJ, Mont MA. The economic impact of periprosthetic infections following total knee arthroplasty at a specialized tertiary-care center. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):929-932.

43. Bhandari M, Smith J, Miller LE, Block JE. Clinical and economic burden of revision knee arthroplasty. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;5:89-94.

44. Kallala RF, Vanhegan IS, Ibrahim MS, Sarmah S, Haddad FS. Financial analysis of revision knee surgery based on NHS tariffs and hospital costs: does it pay to provide a revision service? Bone Joint J Br. 2015;97(2):197-201.

45. Ong KL, Mowat FS, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern MT, Kurtz SM. Economic burden of revision hip and knee arthroplasty in Medicare enrollees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:22-28.

46. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

47. Bozic KJ, Durbhakula S, Berry DJ, et al. Differences in patient and procedure characteristics and hospital resource use in primary and revision total joint arthroplasty: a multicenter study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 suppl 3):17-25.

48. Lee KJ, Moon JY, Song EK, Lim HA, Seon JK. Minimum Two-year Results of Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty Following Infectious or Non-infectious Causes. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012;24(4):227-234.

49. Bae DK, Song SJ, Heo DB, Lee SH, Song WJ. Long-term survival rate of implants and modes of failure after revision total knee arthroplasty by a single surgeon. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1130-1134.

50. Sheng PY, Jämsen E, Lehto MU, Konttinen YT, Pajamäki J, Halonen P. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the Total Condylar III system in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1222-1224.

51. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

52. Haas SB, Insall JN, Montgomery W 3rd, Windsor RE. Revision total knee arthroplasty with use of modular components with stems inserted without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(11):1700-1707.

53. Mabry TM, Vessely MB, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Berry DJ. Revision total knee arthroplasty with modular cemented stems: long-term follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):100-105.

54. Gudnason A, Milbrink J, Hailer NP. Implant survival and outcome after rotating-hinge total knee revision arthroplasty: a minimum 6-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131(11):1601-1607.

55. Hofmann AA, Goldberg T, Tanner AM, Kurtin SM. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer: 2- to 12-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;430:125-131.

56. Greene JW, Reynolds SM, Stimac JD, Malkani AL, Massini MA. Midterm results of hybrid cement technique in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(4):570-574.

57. Dalury DF, Adams MJ. Minimum 6-year follow-up of revision total knee arthroplasty without patella reimplantation. Journal Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):91-94.

58. Whaley AL, Trousdale RT, Rand JA, Hanssen AD. Cemented long-stem revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(5):592-599.