User login

The American Journal of Orthopedics is an Index Medicus publication that is valued by orthopedic surgeons for its peer-reviewed, practice-oriented clinical information. Most articles are written by specialists at leading teaching institutions and help incorporate the latest technology into everyday practice.

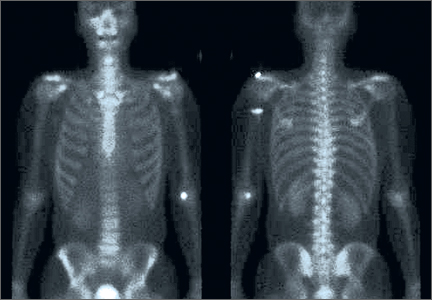

Multifocal Intraosseous Ganglioneuroma

A Biomechanical Comparison of Superior and Anterior Positioning of Precontoured Plates for Midshaft Clavicle Fractures

Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures: A Comparison of Minimally Invasive and Open Approach Repairs Followed by Early Rehabilitation

Cost Analysis of Use of Tranexamic Acid to Prevent Major Bleeding Complications in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Surgery

Advancing Orthopedic Postsurgical Pain Management & Multimodal Care Pathways: Improving Clinical & Economic Outcomes

Commentary to "5 Points on Total Ankle Arthroplasty"

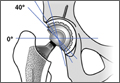

There are considerable differences in the design and implantation technique of the current total ankle implants available in the United States, eg, mobile vs. fixed bearing, intramedullary vs. extramedullary guidance, anterior vs. lateral surgical approach, flat vs. curved bone cuts, natural articular design with minimal bone resection (Zimmer Trabecular Metal Total Ankle; Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) vs. larger implant construct with more bone resection (Inbone II; Figure 2). There is no evidence that one implant design is superior, and, as the authors conclude, “Direct comparisons between TAA [total ankle arthroplasty] implant systems are needed to determine what clinical benefits are achieved with each design and what contributes to these differences.”

Hsu AR, Anderson RB, Cohen BE. Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2014;43(10):451-457.

There are considerable differences in the design and implantation technique of the current total ankle implants available in the United States, eg, mobile vs. fixed bearing, intramedullary vs. extramedullary guidance, anterior vs. lateral surgical approach, flat vs. curved bone cuts, natural articular design with minimal bone resection (Zimmer Trabecular Metal Total Ankle; Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) vs. larger implant construct with more bone resection (Inbone II; Figure 2). There is no evidence that one implant design is superior, and, as the authors conclude, “Direct comparisons between TAA [total ankle arthroplasty] implant systems are needed to determine what clinical benefits are achieved with each design and what contributes to these differences.”

Hsu AR, Anderson RB, Cohen BE. Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2014;43(10):451-457.

There are considerable differences in the design and implantation technique of the current total ankle implants available in the United States, eg, mobile vs. fixed bearing, intramedullary vs. extramedullary guidance, anterior vs. lateral surgical approach, flat vs. curved bone cuts, natural articular design with minimal bone resection (Zimmer Trabecular Metal Total Ankle; Zimmer, Warsaw, Indiana) vs. larger implant construct with more bone resection (Inbone II; Figure 2). There is no evidence that one implant design is superior, and, as the authors conclude, “Direct comparisons between TAA [total ankle arthroplasty] implant systems are needed to determine what clinical benefits are achieved with each design and what contributes to these differences.”

Hsu AR, Anderson RB, Cohen BE. Total Ankle Arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2014;43(10):451-457.

5 Points on Total Ankle Arthroplasty

The Practice of Medicine: Our Changing Landscape

Gone are the days when, upon completion of training, the newly minted orthopedic surgeon would return to his or her hometown, raise a shingle, and begin a busy practice. Did these halcyon days ever exist? Who knows?

What I do know is that 75% of our shoulder fellowship graduates (my partner, Frances Cuomo, MD, and I offer an ACGME-accredited fellowship in shoulder surgery at Mount Sinai Beth Israel) in the past 10 years have accepted jobs as

employees of HMOs or hospital systems. They prefer the certainty of regular hours and incentive options offered by these institutions to the potential opportunities of greater (or lesser!) rewards as an entrepreneur in private practice.

I also know my local New York metropolitan orthopedic market, where the recent trend is towards consolidation among large medical centers. In September 2013, Mount Sinai Medical Center merged with the hospital where I work (full disclosure: I have been a full-time employee of my hospital since 1996), Continuum Health Partners, a consortium of 3 academic hospitals in Manhattan (Beth Israel Medical Center, St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital, and New York Eye and Ear Infirmary), to form the Mount Sinai Health System, currently the largest health care system in New York City. Other medical centers in the New York metropolitan region are actively recruiting physicians in private practice to join their respective institutions. Among the institutional goals, in addition to improving the scope, coordination, and efficiency of care, is to appoint as many practitioners as possible to increase the

number of patients treated by the particular medical center in certain geographic areas. Hence, the practice landscape in the New York metropolitan region is changing dramatically and reflects similar changes throughout the country.

While many practitioners of a certain generation, like mine, may lament the loss of those good old days as independent private practitioners, where self-reliance and experience dictated orthopedic practice, the reality is that today the business of medicine is the largest sector of our national economy, currently approaching 20% of the gross domestic product (GDP),1 and that individual practitioners no longer

really control their practices. The number of independent physicians and surgeons is diminishing, and our practice environment is changing drastically. What’s an orthopedic surgeon to do?

Medical reports are abuzz with new terminology: accountable care organizations, population management, value-based care, etc.1 They all reflect a fundamental shift in health care financing away from our current model of fee for services rendered to that of a global payment for groups of patients in which the outcome of treatment, not the number of procedures or interventions, is compensated. How such a bundled payment that covers the health care requirements for a population will be distributed among the various practitioners is extremely complicated and, to date, not widely embraced. However, these changes are coming.

To succeed in the future health care arena, I believe orthopedic surgeons must have 2 prerequisites. First, there must be reliable data that not only report accurate diagnoses, procedures, and outcomes of treatment (risk-adjusted by medical comorbidities and economic status) but also include the financial costs of treatment. Second, orthopedic surgeons must participate in the decision-making process and the development of treatment algorithms that will be ever-increasing elements of medical practice. Who better than practicing orthopedic surgeons should recommend treatment guidelines based on best practice and prudent

economics?

The new landscape of medical practice isn’t coming—it has already arrived. It behooves us practicing orthopedic surgeons to be involved in the decision-making process that will determine musculoskeletal care and to partner with our hospital and insurance administrators to establish the parameters that will deliver efficient and high-quality care to our patients. ◾

Reference

1. Black EM, Warner JJ. 5 points on value in orthopedic surgery. Am J

Orthop. 2013;42(1):22-25.

Gone are the days when, upon completion of training, the newly minted orthopedic surgeon would return to his or her hometown, raise a shingle, and begin a busy practice. Did these halcyon days ever exist? Who knows?

What I do know is that 75% of our shoulder fellowship graduates (my partner, Frances Cuomo, MD, and I offer an ACGME-accredited fellowship in shoulder surgery at Mount Sinai Beth Israel) in the past 10 years have accepted jobs as

employees of HMOs or hospital systems. They prefer the certainty of regular hours and incentive options offered by these institutions to the potential opportunities of greater (or lesser!) rewards as an entrepreneur in private practice.

I also know my local New York metropolitan orthopedic market, where the recent trend is towards consolidation among large medical centers. In September 2013, Mount Sinai Medical Center merged with the hospital where I work (full disclosure: I have been a full-time employee of my hospital since 1996), Continuum Health Partners, a consortium of 3 academic hospitals in Manhattan (Beth Israel Medical Center, St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital, and New York Eye and Ear Infirmary), to form the Mount Sinai Health System, currently the largest health care system in New York City. Other medical centers in the New York metropolitan region are actively recruiting physicians in private practice to join their respective institutions. Among the institutional goals, in addition to improving the scope, coordination, and efficiency of care, is to appoint as many practitioners as possible to increase the

number of patients treated by the particular medical center in certain geographic areas. Hence, the practice landscape in the New York metropolitan region is changing dramatically and reflects similar changes throughout the country.

While many practitioners of a certain generation, like mine, may lament the loss of those good old days as independent private practitioners, where self-reliance and experience dictated orthopedic practice, the reality is that today the business of medicine is the largest sector of our national economy, currently approaching 20% of the gross domestic product (GDP),1 and that individual practitioners no longer

really control their practices. The number of independent physicians and surgeons is diminishing, and our practice environment is changing drastically. What’s an orthopedic surgeon to do?

Medical reports are abuzz with new terminology: accountable care organizations, population management, value-based care, etc.1 They all reflect a fundamental shift in health care financing away from our current model of fee for services rendered to that of a global payment for groups of patients in which the outcome of treatment, not the number of procedures or interventions, is compensated. How such a bundled payment that covers the health care requirements for a population will be distributed among the various practitioners is extremely complicated and, to date, not widely embraced. However, these changes are coming.

To succeed in the future health care arena, I believe orthopedic surgeons must have 2 prerequisites. First, there must be reliable data that not only report accurate diagnoses, procedures, and outcomes of treatment (risk-adjusted by medical comorbidities and economic status) but also include the financial costs of treatment. Second, orthopedic surgeons must participate in the decision-making process and the development of treatment algorithms that will be ever-increasing elements of medical practice. Who better than practicing orthopedic surgeons should recommend treatment guidelines based on best practice and prudent

economics?

The new landscape of medical practice isn’t coming—it has already arrived. It behooves us practicing orthopedic surgeons to be involved in the decision-making process that will determine musculoskeletal care and to partner with our hospital and insurance administrators to establish the parameters that will deliver efficient and high-quality care to our patients. ◾

Reference

1. Black EM, Warner JJ. 5 points on value in orthopedic surgery. Am J

Orthop. 2013;42(1):22-25.

Gone are the days when, upon completion of training, the newly minted orthopedic surgeon would return to his or her hometown, raise a shingle, and begin a busy practice. Did these halcyon days ever exist? Who knows?

What I do know is that 75% of our shoulder fellowship graduates (my partner, Frances Cuomo, MD, and I offer an ACGME-accredited fellowship in shoulder surgery at Mount Sinai Beth Israel) in the past 10 years have accepted jobs as

employees of HMOs or hospital systems. They prefer the certainty of regular hours and incentive options offered by these institutions to the potential opportunities of greater (or lesser!) rewards as an entrepreneur in private practice.

I also know my local New York metropolitan orthopedic market, where the recent trend is towards consolidation among large medical centers. In September 2013, Mount Sinai Medical Center merged with the hospital where I work (full disclosure: I have been a full-time employee of my hospital since 1996), Continuum Health Partners, a consortium of 3 academic hospitals in Manhattan (Beth Israel Medical Center, St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital, and New York Eye and Ear Infirmary), to form the Mount Sinai Health System, currently the largest health care system in New York City. Other medical centers in the New York metropolitan region are actively recruiting physicians in private practice to join their respective institutions. Among the institutional goals, in addition to improving the scope, coordination, and efficiency of care, is to appoint as many practitioners as possible to increase the

number of patients treated by the particular medical center in certain geographic areas. Hence, the practice landscape in the New York metropolitan region is changing dramatically and reflects similar changes throughout the country.

While many practitioners of a certain generation, like mine, may lament the loss of those good old days as independent private practitioners, where self-reliance and experience dictated orthopedic practice, the reality is that today the business of medicine is the largest sector of our national economy, currently approaching 20% of the gross domestic product (GDP),1 and that individual practitioners no longer

really control their practices. The number of independent physicians and surgeons is diminishing, and our practice environment is changing drastically. What’s an orthopedic surgeon to do?

Medical reports are abuzz with new terminology: accountable care organizations, population management, value-based care, etc.1 They all reflect a fundamental shift in health care financing away from our current model of fee for services rendered to that of a global payment for groups of patients in which the outcome of treatment, not the number of procedures or interventions, is compensated. How such a bundled payment that covers the health care requirements for a population will be distributed among the various practitioners is extremely complicated and, to date, not widely embraced. However, these changes are coming.

To succeed in the future health care arena, I believe orthopedic surgeons must have 2 prerequisites. First, there must be reliable data that not only report accurate diagnoses, procedures, and outcomes of treatment (risk-adjusted by medical comorbidities and economic status) but also include the financial costs of treatment. Second, orthopedic surgeons must participate in the decision-making process and the development of treatment algorithms that will be ever-increasing elements of medical practice. Who better than practicing orthopedic surgeons should recommend treatment guidelines based on best practice and prudent

economics?

The new landscape of medical practice isn’t coming—it has already arrived. It behooves us practicing orthopedic surgeons to be involved in the decision-making process that will determine musculoskeletal care and to partner with our hospital and insurance administrators to establish the parameters that will deliver efficient and high-quality care to our patients. ◾

Reference

1. Black EM, Warner JJ. 5 points on value in orthopedic surgery. Am J

Orthop. 2013;42(1):22-25.