User login

Diabetes Basic Training Program: Empowering Veterans for Wellness

More than 37 million Americans (11.3%) have diabetes mellitus (DM), and 90% to 95% are diagnosed with type 2 DM, including nearly 1 in 4 veterans receiving Veterans Health Administration (VHA) care.1,2 DM is associated with serious negative health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and subsequent complications as well as significant health care system utilization and cost.1,3

Group interventions have been identified as a possible method of improving DM outcomes. For example, shared medical appointments (SMAs) have been identified by the VHA as holding promise for improving care and efficiency for DM and other common health conditions.4 Although the precise structure and SMA process for managing DM has been noted to be heterogeneous, the appointment is typically led by an interdisciplinary health care team and includes individualized assessment including medication review and adjustment, group education, and troubleshooting challenges with management in a group format.5 Research suggests that DM SMAs are a worthwhile treatment approach.5 Several studies have found that SMAs were associated with decreased hemoglobin A1c (Hb A1c) levels and improvement in overall disease complications and severity.6

The high degree of SMA heterogeneity and lack of detailed description of structure and process of SMAs studied has made meta-analysis and other synthesis of the literature difficult.5 Consequently, there is inadequate empirically supported guidance for clinicians and health care organizations on how to best implement SMAs and similar group-based treatments. Edelman and colleagues recommended that future research should focus on more consistent and standardized intervention structures and real-world patient- and staff-centered outcomes to address gaps in the literature.5 They noted that a mental health professional was utilized in only a minority of SMAs studied.5 Additionally, we noted a paucity of studies examining patient satisfaction with SMAs.

Another group-based intervention found to be effective in improving DM outcomes is the 6-session Stanford Diabetes Self-Management Program (DSMP), a workshop led in part by trained peers with DM. The sessions focus on educating patients on DM care and self-management tools. The workshop encourages active practice in building DM self-management skills and confidence. DSMP participation has been associated with improvement in DM-related outcomes, including Hb A1c levels, amount of exercise, and medication adherence.7

While SMAs and DSMP have been shown to enhance clinical outcomes, they provide differing types of patient support. SMAs allow for frequent interaction with a health care professional (HCP) and less emphasis on behavioral health interventions. DSMPs include behavioral health professionals and peer leaders and emphasize higher levels of psychosocial support, but do not offer access to clinicians. It is possible that combining these interventions could result in better outcomes than what either could provide on their own.

In 2018, the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Ohio offered Diabetes Basic Training, a structured DM intervention. Patients enrolled in the program participated in a 9-week intervention that included 3 SMAs and 6 DSMP sessions. During the SMAs, a clinical psychologist or psychology postdoctoral fellow skilled in motivational interviewing facilitated the group to enhance patient engagement and empowerment for improved self-management. In addition, patients participated in structured DSMP groups with an emphasis on action-planning, often surrounding nutrition, physical activity, and other health behavior change information reviewed during the SMAs.

Design and Referral

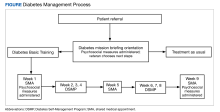

Self-management programs for chronic health conditions are often underutilized. Although HCPs may wish to connect veterans with available programs, time constraints may limit opportunities for detailed discussions with patients about specific aspects of each program. To simplify this process, a 2-hour orientation program was offered that explained individual and group DM self-management options (Figure). During this initial visit, patients met with an interdisciplinary care team (registered dietician, diabetes nurse practitioner, and behavioral health specialist) and were informed about Diabetes Basic Training, DM clinical care practices, and other related resources available at the Cincinnati VAMC (eg, cooking classes, food pantry). Patients received individualized referral recommendations and were urged to consult with their primary care practitioner to finalize their treatment plan.

Shared Medical Appointments

Diabetes Basic Training interventions had an average of 6 to 8 veterans participating in the weekly groups. The first, fifth, and final weeks were SMAs in which an interdisciplinary team collaboratively provided group-based health care for DM. The team consisted of a registered nurse, a prescriber (eg, nurse practitioner), a moderator (eg, psychologist), and a content expert (eg, nutritionist). Before each SMA began, the nurse checked-in patients in the SMA room and collected heart rate and blood pressure, and performed a diabetic foot check. Each SMA consisted of introductions, group-driven discussions (facilitated by an HCP) and troubleshooting DM self-management challenges. During group discussions, the prescriber initiated a 1-on-1 discussion with each patient in a private office regarding their recent laboratory results, medication regimen, and other aspects of DM care. The patient’s medications were refilled and/or adjusted as needed and other orders and referrals were submitted. If a patient had a medical question, the prescriber and moderator engaged the entire group so all individuals could benefit from generating and hearing answers. When discussion slowed, education was provided on topics generated by the group. Frequent topics included challenges managing DM, concerns, how DM impacted daily life and relationships, and sharing successes. As needed, HCPs spoke individually with patients following the SMA. Patients were sometimes asked, but never required, to do homework consistent with standard DM care (eg, recording what they eat or blood sugar levels). Each SMA session lasted about 2 hours.

Diabetes Self-Management Program

The second, third, fourth, sixth, seventh, and eighth weeks of the program were devoted to the DSMP. These sessions were delivered primarily by veteran peers who received appropriate training, observation, and certification. Each 2-hour educational program provided ample practice in many fundamental self-management skills, such as decision making, problem solving, and action planning. Patients were asked, but never required, to practice related skills during the sessions and to create weekly action plans to be completed between sessions that typically involved increasing exercise or improving diet. Patients were encouraged to follow up with HCPs at SMAs when they had questions requiring HCP expertise. If participants had more immediate concerns regarding their treatment plan and/or medications, they contacted their primary care practitioner prior to the next SMA.

As a part of participation in the program, psychosocial and health data and Hb A1c levels at baseline (the closest level to 90 days prior to start) and follow-up (the closest level to 90 days after the final session) were collected.8 In addition, Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID), Patient Activation Measure (PAM)-13, and Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) were administered at 3 points: during the orientation, in the first week, and in the ninth week of the program.

PAID, a 20-item self-report questionnaire designed to capture

Observations

All measures were collected as part of traditional clinical care, and we present initial program evaluation data to demonstrate potential effectiveness of the clinic model. Paired samples t tests were used to examine differences between baseline and follow-up measures for the 24 veteran participants. The age of participants who completed the program ranged from 42 to 74 years (mean, 68 years); 29% of participants were Black veterans and 12% were female. Examination of clinical outcomes indicated that veterans reported significant increases in activation levels for managing their health increasing from a baseline mean (SD) 62.1 (12.3) to 68.4 (14.5) at follow up (t[23] = 2.15, P = .04). Hb A1c levels trended downward from a mean (SD) 8.6% (1.3) at baseline to 8.2% (1.2) at 90-day follow up (t[21] 1.05, P = .30). Similar nonsignificant trends in PAID scores were seen for pre- and postprogram reductions in emotional distress related to having DM from a mean (SD) 7.9 (5.0) at baseline to 6.3 (5.1) (t[18] = 11.51, P = .15), and enhanced self-management of glucose with a mean (SD) 6.5 (1.5) at baseline to 6.8 (1.3) at follow up (t[19] = 0.52, P = .61). The trends found in this study show promising outcomes for this pilot group-based DM treatment, though the small sample size (N = 24) limits statistical power. These findings support further exploration and expansion of interdisciplinary health programs supporting veteran self-management.

Discussion

DM is a condition of epidemic proportions that causes substantial negative health outcomes and costs at a national level. Current standards of DM care do not appear to be reversing these trends. Wider implementation of group-based treatment for DM could improve efficiency of care, increase access to quality care, and reduce burden on individual HCPs.

The VHA continues the transformation of its care system, which shifts toward a patient-centered, proactive focus on veteran well-being. This new whole health approach integrates conventional medical treatment with veteran self-empowerment in the pursuit of health goals based on individual veteran’s identified values.19 This approach emphasizes peer-led explorations of veterans’ aspirations, purpose, and individual mission, personalized health planning, and use of whole health coaches and well-being programs, with both allopathic and complementary and integrative clinical care centered around veterans’ identified goals and priorities.20

Including a program like Diabetes Basic Training as a part of whole health programming could offer several benefits. Diabetes Basic Training is unique in its integration of more traditional SMA structure with psychosocial interventions including values identification and motivational interviewing strategies to enhance patient engagement. Veterans can learn from each other’s experiences and concerns, leading to better DM management knowledge and skills. The group nature of the sessions enhances opportunities for emotional support and reduced isolation, as well as peer accountability for maintaining medication adherence.

By meeting with HCPs from multiple disciplines, veterans are exposed to different perspectives on self-management techniques, including behavioral approaches for overcoming barriers to behavior change. Clinicians have more time to engage with patients, building stronger relationships and trust. SMAs are cost-efficient and time efficient, allowing HCPs to see multiple patients at once, reducing wait times and increasing the number of patients treated in a given time frame.

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily impacted the ongoing expansion of the program, when so many services were shifted from in-person to virtual classes. Due to staffing and other logistic issues, our pilot program was suspended during that time, but plans to resume the program by early 2024 are moving forward.

CONCLUSIONS

The Diabetes Basic Training program serves as a successful model for implementation within a VAMC. Although the number of veterans with complete data available for analysis was small, the trends exhibited in the preliminary outcome data are promising. We encourage other VAMCs to replicate this program with a larger participant base and evaluate its impact on veteran health outcomes. Next steps include comparing the clinical data from treatment as usual with outcomes from DM group participants. As the program resumes, we will reinitiate recruitment efforts to increase HCP referrals to this program.

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Diabetes Statistics. Updated February 2023. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/diabetes-statistics

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. VA research on diabetes. www.research.va.gov. Updated January 15, 2023. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/diabetes.cfm

3. Halter JB, Musi N, McFarland Horne F, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in older adults: current status and future directions. Diabetes. 2014;63(8):2578-2589. doi:10.2337/db14-0020

4. Kirsh S, Watts S, Schaub K, et al. VA shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: maximizing patient and provider expertise to strengthen care management. Updated December 2010. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.vendorportal.ecms.va.gov/FBODocumentServer/DocumentServer.aspx?DocumentId=1513366&FileName=VA244-14-R-0025-011.pdf

5. Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, Williams JW Jr. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):99-106. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2978-7

6. Watts SA, Strauss GJ, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: glycemic reduction in high-risk patients. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(8):450-456. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12200

7. Lorig K, Ritter PL, Turner RM, English K, Laurent DD, Greenberg J. Benefits of diabetes self-management for health plan members: a 6-month translation study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):e164. Published 2016 Jun 24. doi:10.2196/jmir.5568

8. Gilstrap LG, Chernew ME, Nguyen CA, et al. Association between clinical practice group adherence to quality measures and adverse outcomes among adult patients with diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199139. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9139

9. Venkataraman K, Tan LS, Bautista DC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) instrument in Singapore. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136759. Published 2015 Sep 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136759

10. Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH. Responsiveness of the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabet Med. 2003;20(1):69-72. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00832.x

11. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918-1930. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x

12. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

13. Ahn YH, Yi CH, Ham OK, Kim BJ. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the “Patient Activation Measure 13” (PAM13-K) in patients with osteoarthritis. Eval Health Prof. 2015;38(2):255-264. doi:10.1177/0163278714540915

14. Brenk-Franz K, Hibbard JH, Herrmann WJ, et al. Validation of the German version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an international multicentre study of primary care patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74786. Published 2013 Sep 30. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074786

15. Zill JM, Dwinger S, Kriston L, Rohenkohl A, Härter M, Dirmaier J. Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1027. Published 2013 Oct 30. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1027

16. Schmitt A, Gahr A, Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Huber J, Haak T. The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:138. Published 2013 Aug 13. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-138

17. Schmitt A, Reimer A, Hermanns N, et al. assessing diabetes self-management with the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) can help analyse behavioural problems related to reduced glycaemic control. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150774. Published 2016 Mar 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150774

18. Bukhsh A, Lee SWH, Pusparajah P, Schmitt A, Khan TM. Psychometric properties of the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) in Urdu. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):200. Published 2017 Oct 12. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0776-8

19. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

20. Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58(4):295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

More than 37 million Americans (11.3%) have diabetes mellitus (DM), and 90% to 95% are diagnosed with type 2 DM, including nearly 1 in 4 veterans receiving Veterans Health Administration (VHA) care.1,2 DM is associated with serious negative health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and subsequent complications as well as significant health care system utilization and cost.1,3

Group interventions have been identified as a possible method of improving DM outcomes. For example, shared medical appointments (SMAs) have been identified by the VHA as holding promise for improving care and efficiency for DM and other common health conditions.4 Although the precise structure and SMA process for managing DM has been noted to be heterogeneous, the appointment is typically led by an interdisciplinary health care team and includes individualized assessment including medication review and adjustment, group education, and troubleshooting challenges with management in a group format.5 Research suggests that DM SMAs are a worthwhile treatment approach.5 Several studies have found that SMAs were associated with decreased hemoglobin A1c (Hb A1c) levels and improvement in overall disease complications and severity.6

The high degree of SMA heterogeneity and lack of detailed description of structure and process of SMAs studied has made meta-analysis and other synthesis of the literature difficult.5 Consequently, there is inadequate empirically supported guidance for clinicians and health care organizations on how to best implement SMAs and similar group-based treatments. Edelman and colleagues recommended that future research should focus on more consistent and standardized intervention structures and real-world patient- and staff-centered outcomes to address gaps in the literature.5 They noted that a mental health professional was utilized in only a minority of SMAs studied.5 Additionally, we noted a paucity of studies examining patient satisfaction with SMAs.

Another group-based intervention found to be effective in improving DM outcomes is the 6-session Stanford Diabetes Self-Management Program (DSMP), a workshop led in part by trained peers with DM. The sessions focus on educating patients on DM care and self-management tools. The workshop encourages active practice in building DM self-management skills and confidence. DSMP participation has been associated with improvement in DM-related outcomes, including Hb A1c levels, amount of exercise, and medication adherence.7

While SMAs and DSMP have been shown to enhance clinical outcomes, they provide differing types of patient support. SMAs allow for frequent interaction with a health care professional (HCP) and less emphasis on behavioral health interventions. DSMPs include behavioral health professionals and peer leaders and emphasize higher levels of psychosocial support, but do not offer access to clinicians. It is possible that combining these interventions could result in better outcomes than what either could provide on their own.

In 2018, the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Ohio offered Diabetes Basic Training, a structured DM intervention. Patients enrolled in the program participated in a 9-week intervention that included 3 SMAs and 6 DSMP sessions. During the SMAs, a clinical psychologist or psychology postdoctoral fellow skilled in motivational interviewing facilitated the group to enhance patient engagement and empowerment for improved self-management. In addition, patients participated in structured DSMP groups with an emphasis on action-planning, often surrounding nutrition, physical activity, and other health behavior change information reviewed during the SMAs.

Design and Referral

Self-management programs for chronic health conditions are often underutilized. Although HCPs may wish to connect veterans with available programs, time constraints may limit opportunities for detailed discussions with patients about specific aspects of each program. To simplify this process, a 2-hour orientation program was offered that explained individual and group DM self-management options (Figure). During this initial visit, patients met with an interdisciplinary care team (registered dietician, diabetes nurse practitioner, and behavioral health specialist) and were informed about Diabetes Basic Training, DM clinical care practices, and other related resources available at the Cincinnati VAMC (eg, cooking classes, food pantry). Patients received individualized referral recommendations and were urged to consult with their primary care practitioner to finalize their treatment plan.

Shared Medical Appointments

Diabetes Basic Training interventions had an average of 6 to 8 veterans participating in the weekly groups. The first, fifth, and final weeks were SMAs in which an interdisciplinary team collaboratively provided group-based health care for DM. The team consisted of a registered nurse, a prescriber (eg, nurse practitioner), a moderator (eg, psychologist), and a content expert (eg, nutritionist). Before each SMA began, the nurse checked-in patients in the SMA room and collected heart rate and blood pressure, and performed a diabetic foot check. Each SMA consisted of introductions, group-driven discussions (facilitated by an HCP) and troubleshooting DM self-management challenges. During group discussions, the prescriber initiated a 1-on-1 discussion with each patient in a private office regarding their recent laboratory results, medication regimen, and other aspects of DM care. The patient’s medications were refilled and/or adjusted as needed and other orders and referrals were submitted. If a patient had a medical question, the prescriber and moderator engaged the entire group so all individuals could benefit from generating and hearing answers. When discussion slowed, education was provided on topics generated by the group. Frequent topics included challenges managing DM, concerns, how DM impacted daily life and relationships, and sharing successes. As needed, HCPs spoke individually with patients following the SMA. Patients were sometimes asked, but never required, to do homework consistent with standard DM care (eg, recording what they eat or blood sugar levels). Each SMA session lasted about 2 hours.

Diabetes Self-Management Program

The second, third, fourth, sixth, seventh, and eighth weeks of the program were devoted to the DSMP. These sessions were delivered primarily by veteran peers who received appropriate training, observation, and certification. Each 2-hour educational program provided ample practice in many fundamental self-management skills, such as decision making, problem solving, and action planning. Patients were asked, but never required, to practice related skills during the sessions and to create weekly action plans to be completed between sessions that typically involved increasing exercise or improving diet. Patients were encouraged to follow up with HCPs at SMAs when they had questions requiring HCP expertise. If participants had more immediate concerns regarding their treatment plan and/or medications, they contacted their primary care practitioner prior to the next SMA.

As a part of participation in the program, psychosocial and health data and Hb A1c levels at baseline (the closest level to 90 days prior to start) and follow-up (the closest level to 90 days after the final session) were collected.8 In addition, Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID), Patient Activation Measure (PAM)-13, and Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) were administered at 3 points: during the orientation, in the first week, and in the ninth week of the program.

PAID, a 20-item self-report questionnaire designed to capture

Observations

All measures were collected as part of traditional clinical care, and we present initial program evaluation data to demonstrate potential effectiveness of the clinic model. Paired samples t tests were used to examine differences between baseline and follow-up measures for the 24 veteran participants. The age of participants who completed the program ranged from 42 to 74 years (mean, 68 years); 29% of participants were Black veterans and 12% were female. Examination of clinical outcomes indicated that veterans reported significant increases in activation levels for managing their health increasing from a baseline mean (SD) 62.1 (12.3) to 68.4 (14.5) at follow up (t[23] = 2.15, P = .04). Hb A1c levels trended downward from a mean (SD) 8.6% (1.3) at baseline to 8.2% (1.2) at 90-day follow up (t[21] 1.05, P = .30). Similar nonsignificant trends in PAID scores were seen for pre- and postprogram reductions in emotional distress related to having DM from a mean (SD) 7.9 (5.0) at baseline to 6.3 (5.1) (t[18] = 11.51, P = .15), and enhanced self-management of glucose with a mean (SD) 6.5 (1.5) at baseline to 6.8 (1.3) at follow up (t[19] = 0.52, P = .61). The trends found in this study show promising outcomes for this pilot group-based DM treatment, though the small sample size (N = 24) limits statistical power. These findings support further exploration and expansion of interdisciplinary health programs supporting veteran self-management.

Discussion

DM is a condition of epidemic proportions that causes substantial negative health outcomes and costs at a national level. Current standards of DM care do not appear to be reversing these trends. Wider implementation of group-based treatment for DM could improve efficiency of care, increase access to quality care, and reduce burden on individual HCPs.

The VHA continues the transformation of its care system, which shifts toward a patient-centered, proactive focus on veteran well-being. This new whole health approach integrates conventional medical treatment with veteran self-empowerment in the pursuit of health goals based on individual veteran’s identified values.19 This approach emphasizes peer-led explorations of veterans’ aspirations, purpose, and individual mission, personalized health planning, and use of whole health coaches and well-being programs, with both allopathic and complementary and integrative clinical care centered around veterans’ identified goals and priorities.20

Including a program like Diabetes Basic Training as a part of whole health programming could offer several benefits. Diabetes Basic Training is unique in its integration of more traditional SMA structure with psychosocial interventions including values identification and motivational interviewing strategies to enhance patient engagement. Veterans can learn from each other’s experiences and concerns, leading to better DM management knowledge and skills. The group nature of the sessions enhances opportunities for emotional support and reduced isolation, as well as peer accountability for maintaining medication adherence.

By meeting with HCPs from multiple disciplines, veterans are exposed to different perspectives on self-management techniques, including behavioral approaches for overcoming barriers to behavior change. Clinicians have more time to engage with patients, building stronger relationships and trust. SMAs are cost-efficient and time efficient, allowing HCPs to see multiple patients at once, reducing wait times and increasing the number of patients treated in a given time frame.

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily impacted the ongoing expansion of the program, when so many services were shifted from in-person to virtual classes. Due to staffing and other logistic issues, our pilot program was suspended during that time, but plans to resume the program by early 2024 are moving forward.

CONCLUSIONS

The Diabetes Basic Training program serves as a successful model for implementation within a VAMC. Although the number of veterans with complete data available for analysis was small, the trends exhibited in the preliminary outcome data are promising. We encourage other VAMCs to replicate this program with a larger participant base and evaluate its impact on veteran health outcomes. Next steps include comparing the clinical data from treatment as usual with outcomes from DM group participants. As the program resumes, we will reinitiate recruitment efforts to increase HCP referrals to this program.

More than 37 million Americans (11.3%) have diabetes mellitus (DM), and 90% to 95% are diagnosed with type 2 DM, including nearly 1 in 4 veterans receiving Veterans Health Administration (VHA) care.1,2 DM is associated with serious negative health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and subsequent complications as well as significant health care system utilization and cost.1,3

Group interventions have been identified as a possible method of improving DM outcomes. For example, shared medical appointments (SMAs) have been identified by the VHA as holding promise for improving care and efficiency for DM and other common health conditions.4 Although the precise structure and SMA process for managing DM has been noted to be heterogeneous, the appointment is typically led by an interdisciplinary health care team and includes individualized assessment including medication review and adjustment, group education, and troubleshooting challenges with management in a group format.5 Research suggests that DM SMAs are a worthwhile treatment approach.5 Several studies have found that SMAs were associated with decreased hemoglobin A1c (Hb A1c) levels and improvement in overall disease complications and severity.6

The high degree of SMA heterogeneity and lack of detailed description of structure and process of SMAs studied has made meta-analysis and other synthesis of the literature difficult.5 Consequently, there is inadequate empirically supported guidance for clinicians and health care organizations on how to best implement SMAs and similar group-based treatments. Edelman and colleagues recommended that future research should focus on more consistent and standardized intervention structures and real-world patient- and staff-centered outcomes to address gaps in the literature.5 They noted that a mental health professional was utilized in only a minority of SMAs studied.5 Additionally, we noted a paucity of studies examining patient satisfaction with SMAs.

Another group-based intervention found to be effective in improving DM outcomes is the 6-session Stanford Diabetes Self-Management Program (DSMP), a workshop led in part by trained peers with DM. The sessions focus on educating patients on DM care and self-management tools. The workshop encourages active practice in building DM self-management skills and confidence. DSMP participation has been associated with improvement in DM-related outcomes, including Hb A1c levels, amount of exercise, and medication adherence.7

While SMAs and DSMP have been shown to enhance clinical outcomes, they provide differing types of patient support. SMAs allow for frequent interaction with a health care professional (HCP) and less emphasis on behavioral health interventions. DSMPs include behavioral health professionals and peer leaders and emphasize higher levels of psychosocial support, but do not offer access to clinicians. It is possible that combining these interventions could result in better outcomes than what either could provide on their own.

In 2018, the Cincinnati Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Ohio offered Diabetes Basic Training, a structured DM intervention. Patients enrolled in the program participated in a 9-week intervention that included 3 SMAs and 6 DSMP sessions. During the SMAs, a clinical psychologist or psychology postdoctoral fellow skilled in motivational interviewing facilitated the group to enhance patient engagement and empowerment for improved self-management. In addition, patients participated in structured DSMP groups with an emphasis on action-planning, often surrounding nutrition, physical activity, and other health behavior change information reviewed during the SMAs.

Design and Referral

Self-management programs for chronic health conditions are often underutilized. Although HCPs may wish to connect veterans with available programs, time constraints may limit opportunities for detailed discussions with patients about specific aspects of each program. To simplify this process, a 2-hour orientation program was offered that explained individual and group DM self-management options (Figure). During this initial visit, patients met with an interdisciplinary care team (registered dietician, diabetes nurse practitioner, and behavioral health specialist) and were informed about Diabetes Basic Training, DM clinical care practices, and other related resources available at the Cincinnati VAMC (eg, cooking classes, food pantry). Patients received individualized referral recommendations and were urged to consult with their primary care practitioner to finalize their treatment plan.

Shared Medical Appointments

Diabetes Basic Training interventions had an average of 6 to 8 veterans participating in the weekly groups. The first, fifth, and final weeks were SMAs in which an interdisciplinary team collaboratively provided group-based health care for DM. The team consisted of a registered nurse, a prescriber (eg, nurse practitioner), a moderator (eg, psychologist), and a content expert (eg, nutritionist). Before each SMA began, the nurse checked-in patients in the SMA room and collected heart rate and blood pressure, and performed a diabetic foot check. Each SMA consisted of introductions, group-driven discussions (facilitated by an HCP) and troubleshooting DM self-management challenges. During group discussions, the prescriber initiated a 1-on-1 discussion with each patient in a private office regarding their recent laboratory results, medication regimen, and other aspects of DM care. The patient’s medications were refilled and/or adjusted as needed and other orders and referrals were submitted. If a patient had a medical question, the prescriber and moderator engaged the entire group so all individuals could benefit from generating and hearing answers. When discussion slowed, education was provided on topics generated by the group. Frequent topics included challenges managing DM, concerns, how DM impacted daily life and relationships, and sharing successes. As needed, HCPs spoke individually with patients following the SMA. Patients were sometimes asked, but never required, to do homework consistent with standard DM care (eg, recording what they eat or blood sugar levels). Each SMA session lasted about 2 hours.

Diabetes Self-Management Program

The second, third, fourth, sixth, seventh, and eighth weeks of the program were devoted to the DSMP. These sessions were delivered primarily by veteran peers who received appropriate training, observation, and certification. Each 2-hour educational program provided ample practice in many fundamental self-management skills, such as decision making, problem solving, and action planning. Patients were asked, but never required, to practice related skills during the sessions and to create weekly action plans to be completed between sessions that typically involved increasing exercise or improving diet. Patients were encouraged to follow up with HCPs at SMAs when they had questions requiring HCP expertise. If participants had more immediate concerns regarding their treatment plan and/or medications, they contacted their primary care practitioner prior to the next SMA.

As a part of participation in the program, psychosocial and health data and Hb A1c levels at baseline (the closest level to 90 days prior to start) and follow-up (the closest level to 90 days after the final session) were collected.8 In addition, Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID), Patient Activation Measure (PAM)-13, and Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) were administered at 3 points: during the orientation, in the first week, and in the ninth week of the program.

PAID, a 20-item self-report questionnaire designed to capture

Observations

All measures were collected as part of traditional clinical care, and we present initial program evaluation data to demonstrate potential effectiveness of the clinic model. Paired samples t tests were used to examine differences between baseline and follow-up measures for the 24 veteran participants. The age of participants who completed the program ranged from 42 to 74 years (mean, 68 years); 29% of participants were Black veterans and 12% were female. Examination of clinical outcomes indicated that veterans reported significant increases in activation levels for managing their health increasing from a baseline mean (SD) 62.1 (12.3) to 68.4 (14.5) at follow up (t[23] = 2.15, P = .04). Hb A1c levels trended downward from a mean (SD) 8.6% (1.3) at baseline to 8.2% (1.2) at 90-day follow up (t[21] 1.05, P = .30). Similar nonsignificant trends in PAID scores were seen for pre- and postprogram reductions in emotional distress related to having DM from a mean (SD) 7.9 (5.0) at baseline to 6.3 (5.1) (t[18] = 11.51, P = .15), and enhanced self-management of glucose with a mean (SD) 6.5 (1.5) at baseline to 6.8 (1.3) at follow up (t[19] = 0.52, P = .61). The trends found in this study show promising outcomes for this pilot group-based DM treatment, though the small sample size (N = 24) limits statistical power. These findings support further exploration and expansion of interdisciplinary health programs supporting veteran self-management.

Discussion

DM is a condition of epidemic proportions that causes substantial negative health outcomes and costs at a national level. Current standards of DM care do not appear to be reversing these trends. Wider implementation of group-based treatment for DM could improve efficiency of care, increase access to quality care, and reduce burden on individual HCPs.

The VHA continues the transformation of its care system, which shifts toward a patient-centered, proactive focus on veteran well-being. This new whole health approach integrates conventional medical treatment with veteran self-empowerment in the pursuit of health goals based on individual veteran’s identified values.19 This approach emphasizes peer-led explorations of veterans’ aspirations, purpose, and individual mission, personalized health planning, and use of whole health coaches and well-being programs, with both allopathic and complementary and integrative clinical care centered around veterans’ identified goals and priorities.20

Including a program like Diabetes Basic Training as a part of whole health programming could offer several benefits. Diabetes Basic Training is unique in its integration of more traditional SMA structure with psychosocial interventions including values identification and motivational interviewing strategies to enhance patient engagement. Veterans can learn from each other’s experiences and concerns, leading to better DM management knowledge and skills. The group nature of the sessions enhances opportunities for emotional support and reduced isolation, as well as peer accountability for maintaining medication adherence.

By meeting with HCPs from multiple disciplines, veterans are exposed to different perspectives on self-management techniques, including behavioral approaches for overcoming barriers to behavior change. Clinicians have more time to engage with patients, building stronger relationships and trust. SMAs are cost-efficient and time efficient, allowing HCPs to see multiple patients at once, reducing wait times and increasing the number of patients treated in a given time frame.

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily impacted the ongoing expansion of the program, when so many services were shifted from in-person to virtual classes. Due to staffing and other logistic issues, our pilot program was suspended during that time, but plans to resume the program by early 2024 are moving forward.

CONCLUSIONS

The Diabetes Basic Training program serves as a successful model for implementation within a VAMC. Although the number of veterans with complete data available for analysis was small, the trends exhibited in the preliminary outcome data are promising. We encourage other VAMCs to replicate this program with a larger participant base and evaluate its impact on veteran health outcomes. Next steps include comparing the clinical data from treatment as usual with outcomes from DM group participants. As the program resumes, we will reinitiate recruitment efforts to increase HCP referrals to this program.

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Diabetes Statistics. Updated February 2023. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/diabetes-statistics

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. VA research on diabetes. www.research.va.gov. Updated January 15, 2023. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/diabetes.cfm

3. Halter JB, Musi N, McFarland Horne F, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in older adults: current status and future directions. Diabetes. 2014;63(8):2578-2589. doi:10.2337/db14-0020

4. Kirsh S, Watts S, Schaub K, et al. VA shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: maximizing patient and provider expertise to strengthen care management. Updated December 2010. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.vendorportal.ecms.va.gov/FBODocumentServer/DocumentServer.aspx?DocumentId=1513366&FileName=VA244-14-R-0025-011.pdf

5. Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, Williams JW Jr. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):99-106. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2978-7

6. Watts SA, Strauss GJ, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: glycemic reduction in high-risk patients. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(8):450-456. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12200

7. Lorig K, Ritter PL, Turner RM, English K, Laurent DD, Greenberg J. Benefits of diabetes self-management for health plan members: a 6-month translation study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):e164. Published 2016 Jun 24. doi:10.2196/jmir.5568

8. Gilstrap LG, Chernew ME, Nguyen CA, et al. Association between clinical practice group adherence to quality measures and adverse outcomes among adult patients with diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199139. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9139

9. Venkataraman K, Tan LS, Bautista DC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) instrument in Singapore. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136759. Published 2015 Sep 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136759

10. Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH. Responsiveness of the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabet Med. 2003;20(1):69-72. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00832.x

11. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918-1930. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x

12. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

13. Ahn YH, Yi CH, Ham OK, Kim BJ. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the “Patient Activation Measure 13” (PAM13-K) in patients with osteoarthritis. Eval Health Prof. 2015;38(2):255-264. doi:10.1177/0163278714540915

14. Brenk-Franz K, Hibbard JH, Herrmann WJ, et al. Validation of the German version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an international multicentre study of primary care patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74786. Published 2013 Sep 30. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074786

15. Zill JM, Dwinger S, Kriston L, Rohenkohl A, Härter M, Dirmaier J. Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1027. Published 2013 Oct 30. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1027

16. Schmitt A, Gahr A, Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Huber J, Haak T. The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:138. Published 2013 Aug 13. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-138

17. Schmitt A, Reimer A, Hermanns N, et al. assessing diabetes self-management with the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) can help analyse behavioural problems related to reduced glycaemic control. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150774. Published 2016 Mar 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150774

18. Bukhsh A, Lee SWH, Pusparajah P, Schmitt A, Khan TM. Psychometric properties of the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) in Urdu. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):200. Published 2017 Oct 12. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0776-8

19. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

20. Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58(4):295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

1. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Diabetes Statistics. Updated February 2023. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/diabetes-statistics

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. VA research on diabetes. www.research.va.gov. Updated January 15, 2023. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.research.va.gov/topics/diabetes.cfm

3. Halter JB, Musi N, McFarland Horne F, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in older adults: current status and future directions. Diabetes. 2014;63(8):2578-2589. doi:10.2337/db14-0020

4. Kirsh S, Watts S, Schaub K, et al. VA shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: maximizing patient and provider expertise to strengthen care management. Updated December 2010. Accessed January 22, 2024. https://www.vendorportal.ecms.va.gov/FBODocumentServer/DocumentServer.aspx?DocumentId=1513366&FileName=VA244-14-R-0025-011.pdf

5. Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, Williams JW Jr. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):99-106. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2978-7

6. Watts SA, Strauss GJ, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes: glycemic reduction in high-risk patients. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(8):450-456. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12200

7. Lorig K, Ritter PL, Turner RM, English K, Laurent DD, Greenberg J. Benefits of diabetes self-management for health plan members: a 6-month translation study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):e164. Published 2016 Jun 24. doi:10.2196/jmir.5568

8. Gilstrap LG, Chernew ME, Nguyen CA, et al. Association between clinical practice group adherence to quality measures and adverse outcomes among adult patients with diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199139. Published 2019 Aug 2. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9139

9. Venkataraman K, Tan LS, Bautista DC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) instrument in Singapore. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0136759. Published 2015 Sep 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136759

10. Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH. Responsiveness of the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabet Med. 2003;20(1):69-72. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00832.x

11. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918-1930. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x

12. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

13. Ahn YH, Yi CH, Ham OK, Kim BJ. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the “Patient Activation Measure 13” (PAM13-K) in patients with osteoarthritis. Eval Health Prof. 2015;38(2):255-264. doi:10.1177/0163278714540915

14. Brenk-Franz K, Hibbard JH, Herrmann WJ, et al. Validation of the German version of the patient activation measure 13 (PAM13-D) in an international multicentre study of primary care patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74786. Published 2013 Sep 30. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074786

15. Zill JM, Dwinger S, Kriston L, Rohenkohl A, Härter M, Dirmaier J. Psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM13). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1027. Published 2013 Oct 30. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1027

16. Schmitt A, Gahr A, Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Huber J, Haak T. The Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ): development and evaluation of an instrument to assess diabetes self-care activities associated with glycaemic control. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:138. Published 2013 Aug 13. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-138

17. Schmitt A, Reimer A, Hermanns N, et al. assessing diabetes self-management with the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) can help analyse behavioural problems related to reduced glycaemic control. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150774. Published 2016 Mar 3. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150774

18. Bukhsh A, Lee SWH, Pusparajah P, Schmitt A, Khan TM. Psychometric properties of the Diabetes Self-Management Questionnaire (DSMQ) in Urdu. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):200. Published 2017 Oct 12. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0776-8

19. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

20. Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a whole health system of care: time for action and research. Med Care. 2020;58(4):295-300. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316

Fighting to Serve: Women in Military Medicine

Let the generations know that women in uniform also guaranteed their freedom.

Mary Walker, MD

Hoping to make a career in nursing, my mother, a newly graduated registered nurse, enlisted in the US Army Nurse Corps shortly after the United States entered World War II. When she married my father, a US Army doctor, in 1942, she was summarily discharged (the Army Nurse Corp changed its policy and permitted married nurses to serve later that year), while my father went on to decades of distinguished service in military medicine.1 My mother always regretted being unable to advance through the ranks of the US Army as other woman nurses did in her training class.

March is Women’s History Month. My personal narrative of discrimination against women in military medicine is a footnote in a long volume of inequitable treatment. This column will examine a few of the most famous—or rather from a justice perspective, infamous—chapters in that story to illustrate how for centuries women heroically fought for the right to serve.

A theme of the early epochs of the American military is that women were forced to come to the difficult realization that the only way to serve was to conceal their identity. In 1776, Margaret Cochran Corbin felt called as her husband did to defend the new nation. She dressed as a man and joined him at the ramparts, helping load his cannon until he was killed, and took over firing at the enemy. Even after being shot, she remained in the ranks, entering the Invalid Regiment at West Point, New York, dedicated to caring for other injured soldiers. As recognition of her exemplary service and battlefield injury Corbin became the first US woman to receive a military pension. The Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System Manhattan campus is named in her honor.2

The hypocrisy of the military’s gender politics was nowhere more evident than in the case of Mary Walker, MD, and the Congressional Medal of Honor. Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. At the beginning of the Civil War, Walker’s request to enlist as a surgeon was refused on the grounds of her gender. She declined to be a nurse, and instead volunteered for the Army where she cared for the wounded in various hospitals. Her medical degree was accepted in 1863, enabling her to become a paid surgical officer in the War Department, including 4 months as a prisoner of war.

An early and avid feminist, Walker wore men’s clothing and when she was arrested on the charge of impersonating a male, declared the government had given her permission to dress as a man to facilitate her surgical work. Walker separated from the military in 1865 and President Andrew Johnson awarded her the Congressional Medal of Honor that year. After Walker’s death in 1917, the Medal of Honor was rescinded on the grounds that she had never actually been commissioned and the medal could not be awarded to a civilian. It took 60 years of lobbying before President Jimmy Carter restored her award in 1977.3 That millions of women have served in the military since the Civil War, and Walker remains the only woman among the 3517 service members to have won the nation’s highest military honor, underscores the ongoing injustice.4

February commemorated Black History Month and a second theme that emerges from the study of the history of women in military medicine is intersectionality: How race, gender, sexual orientation, and other identities overlap and interact to generate distinctive forms of discrimination. Ethicists have applied the concept of intersectionality to health care and there are a plethora of examples in military medicine.5 Despite a dire need for nurses in the first and second world wars, and a track record of their exemplary service in prior conflicts, the government repeatedly set up arbitrary obstacles barring highly-qualified Black nurses from enlisting.6 Technically allowed to join the Army Nurse Corps in 1941, Black nurses confronted bureaucratic barriers that restricted them to only caring for Black servicemen and prisoners of war, and racial quotas that resulted in 500 Black nurses vs 59,000 White nurses that served during World War II. Black nurses and their supporters in government and society persisted, and once in uniform, broke through barriers to achieve administrative and clinical excellence.7

My mother’s experience mirrors that of thousands of women whose dreams for a career in military medicine were shattered or who enlisted only to find their aspirations for advancement in the service thwarted. Medical historians remind us that due to bias, much of the book of women healer’s accomplishments remains unwritten, itself a testimony to the pervasive and enduring marginalization of women in Western society. Yet, as this brief glimpse of women in military medicine shows, there is sufficient evidence for us to appreciate their impressive contributions.8

Reflecting on this sketch of women’s struggle for acceptance in military medicine in March 2024, we may presume that the fight for equity has been continuously trending upward.8 President Joseph R. Biden appointed, and even more surprisingly, the US Congress confirmed Rachel Levine, MD, as US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Under Secretary for Health in 2021, making Levine the highest ranking openly transgender health official in the history of the US government.9 Levine also has the distinction of being the first 4-star admiral in the Commissioned Corps of the US Public Health Service and the only transgender person to achieve this rank in any branch of the US uniformed services.10

However, research suggests that the history of women in the military is far more like an undulating curve. A 2019 study of academic military surgery found evidence of gender disparity even greater than that of the civilian sector.11 True and lasting equity in federal health care practice will require all of us to follow the inspiring examples of so many women known and unknown who fought the military establishment within for the right to heal those wounded fighting the enemy without.

1. Treadwell ME. The Women’s Army Corps. US Army Center of Military History; 1991: Chap 25. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/Wac/ch25.htm

2. Hayes P. Meet five inspiring women veterans. Published November 10, 2022. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://news.va.gov/110571/meet-five-inspiring-women-veterans/

3. Lange K. Meet Dr. Mary Walker: the only female recipient of the Medical of Honor recipient. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.army.mil/article/183800/meet_dr_mary_walker_the_only_female_medal_of_honor_recipient

4. The National Medal of Honor Museum. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://mohmuseum.org/the-medal

5. Wilson Y, White A, Jefferson A, Danis M. Intersectionality in Clinical Medicine: The Need for a Conceptual Framework. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19(2):8-19. doi:10.1080/15265161.2018.1557275

6. National Women’s History Museum. African American Nurses in World War II. Published July 8, 2019. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/african-american-nurses-world-war-ii

7. O’Gan P. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Victory at Home and Abroad: African American Army Nurses in World War II. Published May 8, 2023. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nurses-WWII

8. Neve M. Conclusion. In Conrad LI, Neve M, Nutton V, Porter R, and Wear A, eds. The Western Medical Tradition 800 BC to AD 1800. Cambridge University Press; 1995:477-494.

9. Stolberg SG. ‘This is politics’: Dr. Rachel Levine’s rise as transgender issues gain prominence. The New York Times. Updated May 10, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/us/politics/rachel-levine-transgender.html

10. Franklin J. Dr. Rachel Levine is sworn in as the nation’s first transgender four-star officer. October 19, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/19/1047423156/rachel-levine-first-transgender-four-star-officer

11. Herrick-Reynolds K, Brooks D, Wind G, Jackson P, Latham K. Military medicine and the academic surgery gender gap. Mil Med. 2019;184(9-10):383-387. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz083

Let the generations know that women in uniform also guaranteed their freedom.

Mary Walker, MD

Hoping to make a career in nursing, my mother, a newly graduated registered nurse, enlisted in the US Army Nurse Corps shortly after the United States entered World War II. When she married my father, a US Army doctor, in 1942, she was summarily discharged (the Army Nurse Corp changed its policy and permitted married nurses to serve later that year), while my father went on to decades of distinguished service in military medicine.1 My mother always regretted being unable to advance through the ranks of the US Army as other woman nurses did in her training class.

March is Women’s History Month. My personal narrative of discrimination against women in military medicine is a footnote in a long volume of inequitable treatment. This column will examine a few of the most famous—or rather from a justice perspective, infamous—chapters in that story to illustrate how for centuries women heroically fought for the right to serve.

A theme of the early epochs of the American military is that women were forced to come to the difficult realization that the only way to serve was to conceal their identity. In 1776, Margaret Cochran Corbin felt called as her husband did to defend the new nation. She dressed as a man and joined him at the ramparts, helping load his cannon until he was killed, and took over firing at the enemy. Even after being shot, she remained in the ranks, entering the Invalid Regiment at West Point, New York, dedicated to caring for other injured soldiers. As recognition of her exemplary service and battlefield injury Corbin became the first US woman to receive a military pension. The Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System Manhattan campus is named in her honor.2

The hypocrisy of the military’s gender politics was nowhere more evident than in the case of Mary Walker, MD, and the Congressional Medal of Honor. Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. At the beginning of the Civil War, Walker’s request to enlist as a surgeon was refused on the grounds of her gender. She declined to be a nurse, and instead volunteered for the Army where she cared for the wounded in various hospitals. Her medical degree was accepted in 1863, enabling her to become a paid surgical officer in the War Department, including 4 months as a prisoner of war.

An early and avid feminist, Walker wore men’s clothing and when she was arrested on the charge of impersonating a male, declared the government had given her permission to dress as a man to facilitate her surgical work. Walker separated from the military in 1865 and President Andrew Johnson awarded her the Congressional Medal of Honor that year. After Walker’s death in 1917, the Medal of Honor was rescinded on the grounds that she had never actually been commissioned and the medal could not be awarded to a civilian. It took 60 years of lobbying before President Jimmy Carter restored her award in 1977.3 That millions of women have served in the military since the Civil War, and Walker remains the only woman among the 3517 service members to have won the nation’s highest military honor, underscores the ongoing injustice.4

February commemorated Black History Month and a second theme that emerges from the study of the history of women in military medicine is intersectionality: How race, gender, sexual orientation, and other identities overlap and interact to generate distinctive forms of discrimination. Ethicists have applied the concept of intersectionality to health care and there are a plethora of examples in military medicine.5 Despite a dire need for nurses in the first and second world wars, and a track record of their exemplary service in prior conflicts, the government repeatedly set up arbitrary obstacles barring highly-qualified Black nurses from enlisting.6 Technically allowed to join the Army Nurse Corps in 1941, Black nurses confronted bureaucratic barriers that restricted them to only caring for Black servicemen and prisoners of war, and racial quotas that resulted in 500 Black nurses vs 59,000 White nurses that served during World War II. Black nurses and their supporters in government and society persisted, and once in uniform, broke through barriers to achieve administrative and clinical excellence.7

My mother’s experience mirrors that of thousands of women whose dreams for a career in military medicine were shattered or who enlisted only to find their aspirations for advancement in the service thwarted. Medical historians remind us that due to bias, much of the book of women healer’s accomplishments remains unwritten, itself a testimony to the pervasive and enduring marginalization of women in Western society. Yet, as this brief glimpse of women in military medicine shows, there is sufficient evidence for us to appreciate their impressive contributions.8

Reflecting on this sketch of women’s struggle for acceptance in military medicine in March 2024, we may presume that the fight for equity has been continuously trending upward.8 President Joseph R. Biden appointed, and even more surprisingly, the US Congress confirmed Rachel Levine, MD, as US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Under Secretary for Health in 2021, making Levine the highest ranking openly transgender health official in the history of the US government.9 Levine also has the distinction of being the first 4-star admiral in the Commissioned Corps of the US Public Health Service and the only transgender person to achieve this rank in any branch of the US uniformed services.10

However, research suggests that the history of women in the military is far more like an undulating curve. A 2019 study of academic military surgery found evidence of gender disparity even greater than that of the civilian sector.11 True and lasting equity in federal health care practice will require all of us to follow the inspiring examples of so many women known and unknown who fought the military establishment within for the right to heal those wounded fighting the enemy without.

Let the generations know that women in uniform also guaranteed their freedom.

Mary Walker, MD

Hoping to make a career in nursing, my mother, a newly graduated registered nurse, enlisted in the US Army Nurse Corps shortly after the United States entered World War II. When she married my father, a US Army doctor, in 1942, she was summarily discharged (the Army Nurse Corp changed its policy and permitted married nurses to serve later that year), while my father went on to decades of distinguished service in military medicine.1 My mother always regretted being unable to advance through the ranks of the US Army as other woman nurses did in her training class.

March is Women’s History Month. My personal narrative of discrimination against women in military medicine is a footnote in a long volume of inequitable treatment. This column will examine a few of the most famous—or rather from a justice perspective, infamous—chapters in that story to illustrate how for centuries women heroically fought for the right to serve.

A theme of the early epochs of the American military is that women were forced to come to the difficult realization that the only way to serve was to conceal their identity. In 1776, Margaret Cochran Corbin felt called as her husband did to defend the new nation. She dressed as a man and joined him at the ramparts, helping load his cannon until he was killed, and took over firing at the enemy. Even after being shot, she remained in the ranks, entering the Invalid Regiment at West Point, New York, dedicated to caring for other injured soldiers. As recognition of her exemplary service and battlefield injury Corbin became the first US woman to receive a military pension. The Veterans Affairs New York Harbor Healthcare System Manhattan campus is named in her honor.2

The hypocrisy of the military’s gender politics was nowhere more evident than in the case of Mary Walker, MD, and the Congressional Medal of Honor. Walker graduated from Syracuse Medical College in 1855. At the beginning of the Civil War, Walker’s request to enlist as a surgeon was refused on the grounds of her gender. She declined to be a nurse, and instead volunteered for the Army where she cared for the wounded in various hospitals. Her medical degree was accepted in 1863, enabling her to become a paid surgical officer in the War Department, including 4 months as a prisoner of war.

An early and avid feminist, Walker wore men’s clothing and when she was arrested on the charge of impersonating a male, declared the government had given her permission to dress as a man to facilitate her surgical work. Walker separated from the military in 1865 and President Andrew Johnson awarded her the Congressional Medal of Honor that year. After Walker’s death in 1917, the Medal of Honor was rescinded on the grounds that she had never actually been commissioned and the medal could not be awarded to a civilian. It took 60 years of lobbying before President Jimmy Carter restored her award in 1977.3 That millions of women have served in the military since the Civil War, and Walker remains the only woman among the 3517 service members to have won the nation’s highest military honor, underscores the ongoing injustice.4

February commemorated Black History Month and a second theme that emerges from the study of the history of women in military medicine is intersectionality: How race, gender, sexual orientation, and other identities overlap and interact to generate distinctive forms of discrimination. Ethicists have applied the concept of intersectionality to health care and there are a plethora of examples in military medicine.5 Despite a dire need for nurses in the first and second world wars, and a track record of their exemplary service in prior conflicts, the government repeatedly set up arbitrary obstacles barring highly-qualified Black nurses from enlisting.6 Technically allowed to join the Army Nurse Corps in 1941, Black nurses confronted bureaucratic barriers that restricted them to only caring for Black servicemen and prisoners of war, and racial quotas that resulted in 500 Black nurses vs 59,000 White nurses that served during World War II. Black nurses and their supporters in government and society persisted, and once in uniform, broke through barriers to achieve administrative and clinical excellence.7

My mother’s experience mirrors that of thousands of women whose dreams for a career in military medicine were shattered or who enlisted only to find their aspirations for advancement in the service thwarted. Medical historians remind us that due to bias, much of the book of women healer’s accomplishments remains unwritten, itself a testimony to the pervasive and enduring marginalization of women in Western society. Yet, as this brief glimpse of women in military medicine shows, there is sufficient evidence for us to appreciate their impressive contributions.8

Reflecting on this sketch of women’s struggle for acceptance in military medicine in March 2024, we may presume that the fight for equity has been continuously trending upward.8 President Joseph R. Biden appointed, and even more surprisingly, the US Congress confirmed Rachel Levine, MD, as US Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Under Secretary for Health in 2021, making Levine the highest ranking openly transgender health official in the history of the US government.9 Levine also has the distinction of being the first 4-star admiral in the Commissioned Corps of the US Public Health Service and the only transgender person to achieve this rank in any branch of the US uniformed services.10

However, research suggests that the history of women in the military is far more like an undulating curve. A 2019 study of academic military surgery found evidence of gender disparity even greater than that of the civilian sector.11 True and lasting equity in federal health care practice will require all of us to follow the inspiring examples of so many women known and unknown who fought the military establishment within for the right to heal those wounded fighting the enemy without.

1. Treadwell ME. The Women’s Army Corps. US Army Center of Military History; 1991: Chap 25. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/Wac/ch25.htm

2. Hayes P. Meet five inspiring women veterans. Published November 10, 2022. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://news.va.gov/110571/meet-five-inspiring-women-veterans/

3. Lange K. Meet Dr. Mary Walker: the only female recipient of the Medical of Honor recipient. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.army.mil/article/183800/meet_dr_mary_walker_the_only_female_medal_of_honor_recipient

4. The National Medal of Honor Museum. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://mohmuseum.org/the-medal

5. Wilson Y, White A, Jefferson A, Danis M. Intersectionality in Clinical Medicine: The Need for a Conceptual Framework. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19(2):8-19. doi:10.1080/15265161.2018.1557275

6. National Women’s History Museum. African American Nurses in World War II. Published July 8, 2019. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/african-american-nurses-world-war-ii

7. O’Gan P. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Victory at Home and Abroad: African American Army Nurses in World War II. Published May 8, 2023. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nurses-WWII

8. Neve M. Conclusion. In Conrad LI, Neve M, Nutton V, Porter R, and Wear A, eds. The Western Medical Tradition 800 BC to AD 1800. Cambridge University Press; 1995:477-494.

9. Stolberg SG. ‘This is politics’: Dr. Rachel Levine’s rise as transgender issues gain prominence. The New York Times. Updated May 10, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/us/politics/rachel-levine-transgender.html

10. Franklin J. Dr. Rachel Levine is sworn in as the nation’s first transgender four-star officer. October 19, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/19/1047423156/rachel-levine-first-transgender-four-star-officer

11. Herrick-Reynolds K, Brooks D, Wind G, Jackson P, Latham K. Military medicine and the academic surgery gender gap. Mil Med. 2019;184(9-10):383-387. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz083

1. Treadwell ME. The Women’s Army Corps. US Army Center of Military History; 1991: Chap 25. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/Wac/ch25.htm

2. Hayes P. Meet five inspiring women veterans. Published November 10, 2022. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://news.va.gov/110571/meet-five-inspiring-women-veterans/

3. Lange K. Meet Dr. Mary Walker: the only female recipient of the Medical of Honor recipient. Published March 7, 2017. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.army.mil/article/183800/meet_dr_mary_walker_the_only_female_medal_of_honor_recipient

4. The National Medal of Honor Museum. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://mohmuseum.org/the-medal

5. Wilson Y, White A, Jefferson A, Danis M. Intersectionality in Clinical Medicine: The Need for a Conceptual Framework. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19(2):8-19. doi:10.1080/15265161.2018.1557275

6. National Women’s History Museum. African American Nurses in World War II. Published July 8, 2019. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/african-american-nurses-world-war-ii

7. O’Gan P. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Victory at Home and Abroad: African American Army Nurses in World War II. Published May 8, 2023. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nurses-WWII

8. Neve M. Conclusion. In Conrad LI, Neve M, Nutton V, Porter R, and Wear A, eds. The Western Medical Tradition 800 BC to AD 1800. Cambridge University Press; 1995:477-494.

9. Stolberg SG. ‘This is politics’: Dr. Rachel Levine’s rise as transgender issues gain prominence. The New York Times. Updated May 10, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/us/politics/rachel-levine-transgender.html

10. Franklin J. Dr. Rachel Levine is sworn in as the nation’s first transgender four-star officer. October 19, 2021. Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2021/10/19/1047423156/rachel-levine-first-transgender-four-star-officer

11. Herrick-Reynolds K, Brooks D, Wind G, Jackson P, Latham K. Military medicine and the academic surgery gender gap. Mil Med. 2019;184(9-10):383-387. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz083

Myasthenia Gravis: Treating the Whole Patient

In the dynamic field of myasthenia gravis (MG) treatment, characterized by recent therapeutic advancements and a promising pipeline, Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD, advises early-career professionals to approach the whole patient, considering not only the disease manifestations but also its broader impact on their lives, including work and family.

Emphasizing the importance of tailoring therapies based on individual needs, Dr Silvestri encourages early and aggressive intervention, citing evidence supporting better long-term outcomes, and underscores the significance of treating the whole patient rather than just the disease.

In the dynamic field of myasthenia gravis (MG) treatment, characterized by recent therapeutic advancements and a promising pipeline, Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD, advises early-career professionals to approach the whole patient, considering not only the disease manifestations but also its broader impact on their lives, including work and family.

Emphasizing the importance of tailoring therapies based on individual needs, Dr Silvestri encourages early and aggressive intervention, citing evidence supporting better long-term outcomes, and underscores the significance of treating the whole patient rather than just the disease.

In the dynamic field of myasthenia gravis (MG) treatment, characterized by recent therapeutic advancements and a promising pipeline, Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD, advises early-career professionals to approach the whole patient, considering not only the disease manifestations but also its broader impact on their lives, including work and family.

Emphasizing the importance of tailoring therapies based on individual needs, Dr Silvestri encourages early and aggressive intervention, citing evidence supporting better long-term outcomes, and underscores the significance of treating the whole patient rather than just the disease.

Myasthenia Gravis: 3 Tips to Improve Patient-Centered Care

Kelly G. Gwathmey, MD, offers three key tips for clinicians early in their careers regarding myasthenia gravis (MG): First, prioritize listening to patients, as their experiences may not always align with clinical observations. Second, advocate for shared decision-making when starting or changing treatments, considering individual patient preferences and medical conditions. Third, understand the significance of ongoing monitoring using patient-reported outcome measures and MG scales to assess treatment response and optimize care for patients with MG.