User login

Marathon Runner Needs Preoperative Work-Up

ANSWER

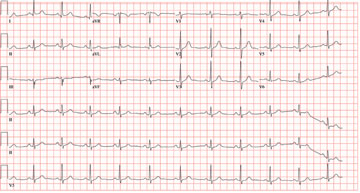

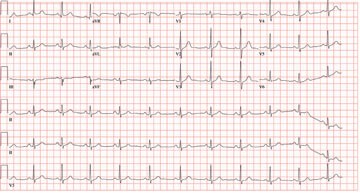

All measured intervals are within normal limits; there is a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave. There is no evidence of injury, ischemia, or infarct, and no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. This is, in other words, a normal ECG—and is that of the author.

Perioperative ordering of ECGs based on patient age, in the absence of prior heart disease, remains controversial. In the majority of cases, identification of abnormal findings does not occur. However, as long as previously unknown anomalies are discovered, this practice will likely continue.

ANSWER

All measured intervals are within normal limits; there is a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave. There is no evidence of injury, ischemia, or infarct, and no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. This is, in other words, a normal ECG—and is that of the author.

Perioperative ordering of ECGs based on patient age, in the absence of prior heart disease, remains controversial. In the majority of cases, identification of abnormal findings does not occur. However, as long as previously unknown anomalies are discovered, this practice will likely continue.

ANSWER

All measured intervals are within normal limits; there is a P wave for every QRS complex and a QRS complex for every P wave. There is no evidence of injury, ischemia, or infarct, and no atrial or ventricular hypertrophy. This is, in other words, a normal ECG—and is that of the author.

Perioperative ordering of ECGs based on patient age, in the absence of prior heart disease, remains controversial. In the majority of cases, identification of abnormal findings does not occur. However, as long as previously unknown anomalies are discovered, this practice will likely continue.

In celebration of his 50th birthday, a man with no prior medical problems decides to run a marathon. He has run a few 5K and 10K events in the past 10 years, and he completed a half-marathon five years ago. Approximately three weeks into his training schedule, he completes a five-mile run; the next morning, he notes significant pain in the medial compartment of the right knee. After resting for two days, he begins running again; however, the pain returns and does not resolve. The pain remains localized to the medial right knee and is exacerbated by high-impact activities, such as climbing and descending stairs, as well as any movement requiring rotation or torque around the right knee. Despite the use of NSAIDs and icing, the pain does not resolve, and the patient presents to the sports medicine clinic. Medical history is negative for any previous knee trauma. Current medications include ibuprofen 800 mg four times daily. There are no known drug allergies. Family history is positive for adult-onset diabetes and valvular heart disease in both sets of grandparents. Both parents are alive and well. Social history shows no history of tobacco or illicit drug use. The patient reports having an occasional glass of wine with dinner. A 12-point review of systems is negative, with the exception of corrective lenses for presbyopia. Physical examination reveals a white man in no distress. The blood pressure is 108/66 mm Hg; pulse, 68 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and temperature, 98°F. The lungs are clear; the cardiac exam reveals a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. There is no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema. The abdominal exam is benign, and there are no neurologic deficits. Examination of the knee reveals very minimal swelling of the joint. The patient is able to fully extend the joint; however, flexion beyond 130° results in severe pain. The knee is stable to varus and valgus stress testing and to Lachman testing. There is fairly significant medial pain with any of the McMurray’s test maneuvers. An MRI of the right knee shows a significant tear in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus, as well as some chondromalacia of the patellofemoral joint. Given the patient’s age, an ECG is ordered as part of the preoperative workup for surgical repair of the right knee. The ECG reveals the following: pulse, 68 beats/min; PR interval, 156 ms; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc interval, 380/404 ms; P axis, 53°; R axis, –5°; and T axis, 18°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Woman Worried Skin Change May Produce Scars

Answer

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”), which is generally confined to sun-exposed areas, tends to be chronic, and eventually causes scarring. Psoriasis (choice “a”) was unlikely, given the lack of corroborative findings over an extended period and the negative personal or family history—and because scarring would be quite unusual with that disease.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC; choice “b”) is an unlikely choice because it is usually accompanied by significant sun damage and it does not typically wax and wane. Actinic keratoses (choice “c”) can come and go, but as with BCC, it would almost certainly be seen in the context of more widespread sun damage on the face.

Discussion

A 3-mm punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the other items in the differential. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) usually demonstrates a classic set of histologic findings, confirming this common—and usually benign—form of lupus that favors the nose, ears, and neck but can be seen on any chronically sun-exposed area. Cancer/precancerous skin changes were definitely worth considering, given the chronicity of the condition.

Although DLE is quite common, outside dermatology it is seldom diagnosed initially. Instead, the natural inclination is treat the condition as “some sort of infection.” DLE often presents with annular, scaly lesions. This is potentially misleading, unless you look for two particular features (both of which, alas, were missing in this case!): The lesions often demonstrate atrophic, whitish centers, and when the scale is gently peeled off the lesions, you can see that the scale was plugging the follicular orifices, in effect dilating them.

Since systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with lesions of DLE, the initial labs should include an antinuclear antibody test. Approximately 5% of purely cutaneous DLE will evolve into SLE. The more extensive and serious the discoid eruption, the more likely is the presence of SLE.

DLE can also involve the scalp, where it can eventuate in focal or widespread scarring alopecia. Less often, it is seen on the lips, tongue, or other areas of oral mucosa.

Treatment

With early, mild cases of DLE, better sun protection and topical steroid creams are all the treatment needed. But in more advanced cases involving scarring, oral therapy with hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg) is also necessary—assuming results of baseline lab testing (eg, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count) and ophthalmologic examination are normal.

After three months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid), this patient’s condition improved dramatically. The dosage was then reduced to once daily for another three months, at which point she’ll stop. She will repeat her eye exam and blood work at that time and continue to use sun protection, since the potential for recurrence is high.

Answer

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”), which is generally confined to sun-exposed areas, tends to be chronic, and eventually causes scarring. Psoriasis (choice “a”) was unlikely, given the lack of corroborative findings over an extended period and the negative personal or family history—and because scarring would be quite unusual with that disease.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC; choice “b”) is an unlikely choice because it is usually accompanied by significant sun damage and it does not typically wax and wane. Actinic keratoses (choice “c”) can come and go, but as with BCC, it would almost certainly be seen in the context of more widespread sun damage on the face.

Discussion

A 3-mm punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the other items in the differential. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) usually demonstrates a classic set of histologic findings, confirming this common—and usually benign—form of lupus that favors the nose, ears, and neck but can be seen on any chronically sun-exposed area. Cancer/precancerous skin changes were definitely worth considering, given the chronicity of the condition.

Although DLE is quite common, outside dermatology it is seldom diagnosed initially. Instead, the natural inclination is treat the condition as “some sort of infection.” DLE often presents with annular, scaly lesions. This is potentially misleading, unless you look for two particular features (both of which, alas, were missing in this case!): The lesions often demonstrate atrophic, whitish centers, and when the scale is gently peeled off the lesions, you can see that the scale was plugging the follicular orifices, in effect dilating them.

Since systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with lesions of DLE, the initial labs should include an antinuclear antibody test. Approximately 5% of purely cutaneous DLE will evolve into SLE. The more extensive and serious the discoid eruption, the more likely is the presence of SLE.

DLE can also involve the scalp, where it can eventuate in focal or widespread scarring alopecia. Less often, it is seen on the lips, tongue, or other areas of oral mucosa.

Treatment

With early, mild cases of DLE, better sun protection and topical steroid creams are all the treatment needed. But in more advanced cases involving scarring, oral therapy with hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg) is also necessary—assuming results of baseline lab testing (eg, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count) and ophthalmologic examination are normal.

After three months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid), this patient’s condition improved dramatically. The dosage was then reduced to once daily for another three months, at which point she’ll stop. She will repeat her eye exam and blood work at that time and continue to use sun protection, since the potential for recurrence is high.

Answer

The correct answer is discoid lupus (choice “d”), which is generally confined to sun-exposed areas, tends to be chronic, and eventually causes scarring. Psoriasis (choice “a”) was unlikely, given the lack of corroborative findings over an extended period and the negative personal or family history—and because scarring would be quite unusual with that disease.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC; choice “b”) is an unlikely choice because it is usually accompanied by significant sun damage and it does not typically wax and wane. Actinic keratoses (choice “c”) can come and go, but as with BCC, it would almost certainly be seen in the context of more widespread sun damage on the face.

Discussion

A 3-mm punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the other items in the differential. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) usually demonstrates a classic set of histologic findings, confirming this common—and usually benign—form of lupus that favors the nose, ears, and neck but can be seen on any chronically sun-exposed area. Cancer/precancerous skin changes were definitely worth considering, given the chronicity of the condition.

Although DLE is quite common, outside dermatology it is seldom diagnosed initially. Instead, the natural inclination is treat the condition as “some sort of infection.” DLE often presents with annular, scaly lesions. This is potentially misleading, unless you look for two particular features (both of which, alas, were missing in this case!): The lesions often demonstrate atrophic, whitish centers, and when the scale is gently peeled off the lesions, you can see that the scale was plugging the follicular orifices, in effect dilating them.

Since systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can present with lesions of DLE, the initial labs should include an antinuclear antibody test. Approximately 5% of purely cutaneous DLE will evolve into SLE. The more extensive and serious the discoid eruption, the more likely is the presence of SLE.

DLE can also involve the scalp, where it can eventuate in focal or widespread scarring alopecia. Less often, it is seen on the lips, tongue, or other areas of oral mucosa.

Treatment

With early, mild cases of DLE, better sun protection and topical steroid creams are all the treatment needed. But in more advanced cases involving scarring, oral therapy with hydroxychloroquine (6.5 mg/kg) is also necessary—assuming results of baseline lab testing (eg, comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count) and ophthalmologic examination are normal.

After three months of therapy with hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid), this patient’s condition improved dramatically. The dosage was then reduced to once daily for another three months, at which point she’ll stop. She will repeat her eye exam and blood work at that time and continue to use sun protection, since the potential for recurrence is high.

A 45-year-old nurse self-refers for evaluation of changes on her nose and upper forehead. These began about five years ago but in the past few months have become alarming in their progression. The condition is largely asymptomatic and wanes a bit each winter, but overall it has grown considerably over the years—now threatening to produce scarring. The patient denies having any other significant medical issues (ie, joint pain, fever, or malaise). She has never had skin cancer but does acknowledge getting “too much sun” every summer while gardening. She denies any history of foreign travel. As a nurse, she has worked in cardiology exclusively. There is no known family history of skin disease. On exam, the lesions are fairly impressive—especially on the nasal bridge, where there is focal, significant erosion surrounded by peeling skin, all on an erythematous base that is roughly 3 cm in its maximum dimension and polygonal in shape. Despite these changes, surface adnexae (pores, follicles, skin lines) on this lesion are largely intact, except on the superior margin, where definite scarring is seen. Similar changes are seen at the forehead/scalp interface, but with some small areas of scarring alopecia noted focally. Overall, the patient’s skin is fair, but with little overt evidence of sun damage. Her elbows, knees, scalp, and fingernails are free of pathologic changes.

Man with Decreasing Consciousness and Increasing Confusion

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a lucency at the base of the odontoid (C2). In addition, there is a slight posterior subluxation of C1 on C2.

Although these findings were deemed likely to be chronic and old in nature, for completeness, an MRI of the cervical spine was obtained. It did, in fact, confirm the findings to be old.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a lucency at the base of the odontoid (C2). In addition, there is a slight posterior subluxation of C1 on C2.

Although these findings were deemed likely to be chronic and old in nature, for completeness, an MRI of the cervical spine was obtained. It did, in fact, confirm the findings to be old.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates a lucency at the base of the odontoid (C2). In addition, there is a slight posterior subluxation of C1 on C2.

Although these findings were deemed likely to be chronic and old in nature, for completeness, an MRI of the cervical spine was obtained. It did, in fact, confirm the findings to be old.

A 72-year-old nursing home resident is sent for evaluation of decreased level of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and increasing confusion. He denies any recent injury or trauma. His medical history is significant for diabetes, stroke, dementia, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension. The patient denies any head or neck pain. His vital signs are stable. Overall, aside from reports of occasional confusion, his physical examination is benign. He moves all of his extremities well and appears to have no deficits, including no neck or back tenderness. In reviewing his lab work, you see his sodium concentration is 126 mEq/L. CT of the head shows only chronic changes. Cervical spine radiographs are also obtained; the lateral view is shown. What is your impression?

40 Year Old "Wart" Suddenly Changes

Answer

Digital mucous cysts (choice “c”), also known as myxoid cysts, are quite common and are found often on fingers and occasionally on toes. But they are almost always located on the distal dorsal portion of the digit, between the cuticle and distal interphalangeal joint—close enough, in many cases, to compress the nail matrix, which leads to a longitudinal trough in the nail plate. Surface erosion of these lesions is unusual but is occasionally seen.

However, given the history, appearance, and especially the location of this patient’s lesion, this is the one diagnosis our patient almost certainly did not have. The others, discussed below, were all real possibilities, and since “common things occur commonly,” squamous cell carcinoma was the most likely.

Discussion

With this clinical picture, cancer is assumed until proven otherwise. In that regard, the presence of a longstanding wart in this location is especially significant, since human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to be potentially oncogenic. The patient’s heavily sun-damaged skin adds another layer of risk for malignant transformation.

The only way to sort through this differential diagnosis was to perform a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—one that showed evidence of arising from a long-standing wart. The patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery, for two reasons: (1) this location does not lend itself to simple excision and closure, both because of the paucity of adjacent skin and because of the potential for damage to the underlying tendons, nerves, and blood supply, and (2) SCCs of nonsolar causation (besides HPV, these include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and chronic ulcers) have more potential for metastasis than do the far more common sun-caused SCCs. This is all the more reason to obtain adequate margins. Often in such cases, irradiation of the site is also done, postoperatively.

Had the biopsy not shown clear evidence of cancer, the other items in the differential diagnosis would have come into play. This would have necessitated an additional biopsy, this time to obtain tissue for acid-fast bacilli and bacterial and fungal cultures.

As of this writing, the patient is awaiting Mohs surgery. He will have to be followed closely for at least a year to watch for any signs of metastasis. With an intact immune system, his prognosis is excellent.

Answer

Digital mucous cysts (choice “c”), also known as myxoid cysts, are quite common and are found often on fingers and occasionally on toes. But they are almost always located on the distal dorsal portion of the digit, between the cuticle and distal interphalangeal joint—close enough, in many cases, to compress the nail matrix, which leads to a longitudinal trough in the nail plate. Surface erosion of these lesions is unusual but is occasionally seen.

However, given the history, appearance, and especially the location of this patient’s lesion, this is the one diagnosis our patient almost certainly did not have. The others, discussed below, were all real possibilities, and since “common things occur commonly,” squamous cell carcinoma was the most likely.

Discussion

With this clinical picture, cancer is assumed until proven otherwise. In that regard, the presence of a longstanding wart in this location is especially significant, since human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to be potentially oncogenic. The patient’s heavily sun-damaged skin adds another layer of risk for malignant transformation.

The only way to sort through this differential diagnosis was to perform a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—one that showed evidence of arising from a long-standing wart. The patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery, for two reasons: (1) this location does not lend itself to simple excision and closure, both because of the paucity of adjacent skin and because of the potential for damage to the underlying tendons, nerves, and blood supply, and (2) SCCs of nonsolar causation (besides HPV, these include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and chronic ulcers) have more potential for metastasis than do the far more common sun-caused SCCs. This is all the more reason to obtain adequate margins. Often in such cases, irradiation of the site is also done, postoperatively.

Had the biopsy not shown clear evidence of cancer, the other items in the differential diagnosis would have come into play. This would have necessitated an additional biopsy, this time to obtain tissue for acid-fast bacilli and bacterial and fungal cultures.

As of this writing, the patient is awaiting Mohs surgery. He will have to be followed closely for at least a year to watch for any signs of metastasis. With an intact immune system, his prognosis is excellent.

Answer

Digital mucous cysts (choice “c”), also known as myxoid cysts, are quite common and are found often on fingers and occasionally on toes. But they are almost always located on the distal dorsal portion of the digit, between the cuticle and distal interphalangeal joint—close enough, in many cases, to compress the nail matrix, which leads to a longitudinal trough in the nail plate. Surface erosion of these lesions is unusual but is occasionally seen.

However, given the history, appearance, and especially the location of this patient’s lesion, this is the one diagnosis our patient almost certainly did not have. The others, discussed below, were all real possibilities, and since “common things occur commonly,” squamous cell carcinoma was the most likely.

Discussion

With this clinical picture, cancer is assumed until proven otherwise. In that regard, the presence of a longstanding wart in this location is especially significant, since human papillomavirus (HPV) is known to be potentially oncogenic. The patient’s heavily sun-damaged skin adds another layer of risk for malignant transformation.

The only way to sort through this differential diagnosis was to perform a shave biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—one that showed evidence of arising from a long-standing wart. The patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery, for two reasons: (1) this location does not lend itself to simple excision and closure, both because of the paucity of adjacent skin and because of the potential for damage to the underlying tendons, nerves, and blood supply, and (2) SCCs of nonsolar causation (besides HPV, these include ionizing radiation, arsenic, and chronic ulcers) have more potential for metastasis than do the far more common sun-caused SCCs. This is all the more reason to obtain adequate margins. Often in such cases, irradiation of the site is also done, postoperatively.

Had the biopsy not shown clear evidence of cancer, the other items in the differential diagnosis would have come into play. This would have necessitated an additional biopsy, this time to obtain tissue for acid-fast bacilli and bacterial and fungal cultures.

As of this writing, the patient is awaiting Mohs surgery. He will have to be followed closely for at least a year to watch for any signs of metastasis. With an intact immune system, his prognosis is excellent.

An 87-year-old man presents for evaluation of a lesion on his left fifth finger that has grown and become ulcerated in the past five months. There is almost no pain in the lesion, which the patient insists was a “wart” for the 40 years prior to these recent changes. Over the years, he has treated his wart with acids, curettement, and liquid nitrogen, to no effect. A recent seven-day course of cephalexin (500 mg tid) also failed to help. Additional history taking reveals that the patient is a farmer who spent his entire life working outdoors every day, year-round. There is no history of immunosuppression. His medications include metoprolol and hydrochlorothiazide. Closer inspection of the lesion reveals a 9-mm, centrally eroded nodule overlying the dorsal proximal interphalangeal joint. The lesion is quite firm on palpation, with a surface that looks and feels smooth and is nontender, with minimal redness. There are no palpable nodes in the epitrochlear or axillary locations. Elsewhere, the patient’s skin is remarkably sun-damaged, with numerous actinic keratoses, solar lentigines, and solar atrophy evident, especially on his hands.

A History of Palpitations and Dizziness

ANSWER

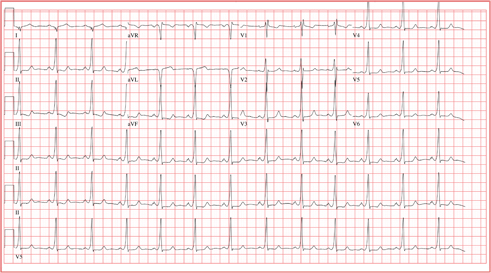

This ECG is diagnostic for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. Criteria for WPW syndrome include a normal P wave with a PR interval generally (but not always) of 0.12 sec (120 ms) or greater, initial slurring of the QRS (delta wave), a wide QRS interval > 0.10 sec (100 ms), and secondary ST/T wave changes.

In WPW syndrome, one (or multiple) accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles allows conduction impulses to bypass the atrioventricular node and activate the ventricles prematurely. This premature ventricular activation is responsible for the initial slurring of the QRS complex and produces the characteristic delta wave. The presence of an accessory pathway allows a reentrant tachycardia circuit to occur and is the source of this patient’s palpitations. Subsequent electrophysiology studies identified a single left lateral accessory pathway.

ANSWER

This ECG is diagnostic for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. Criteria for WPW syndrome include a normal P wave with a PR interval generally (but not always) of 0.12 sec (120 ms) or greater, initial slurring of the QRS (delta wave), a wide QRS interval > 0.10 sec (100 ms), and secondary ST/T wave changes.

In WPW syndrome, one (or multiple) accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles allows conduction impulses to bypass the atrioventricular node and activate the ventricles prematurely. This premature ventricular activation is responsible for the initial slurring of the QRS complex and produces the characteristic delta wave. The presence of an accessory pathway allows a reentrant tachycardia circuit to occur and is the source of this patient’s palpitations. Subsequent electrophysiology studies identified a single left lateral accessory pathway.

ANSWER

This ECG is diagnostic for Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome. Criteria for WPW syndrome include a normal P wave with a PR interval generally (but not always) of 0.12 sec (120 ms) or greater, initial slurring of the QRS (delta wave), a wide QRS interval > 0.10 sec (100 ms), and secondary ST/T wave changes.

In WPW syndrome, one (or multiple) accessory pathway between the atria and ventricles allows conduction impulses to bypass the atrioventricular node and activate the ventricles prematurely. This premature ventricular activation is responsible for the initial slurring of the QRS complex and produces the characteristic delta wave. The presence of an accessory pathway allows a reentrant tachycardia circuit to occur and is the source of this patient’s palpitations. Subsequent electrophysiology studies identified a single left lateral accessory pathway.

A 20-year-old woman is involved in a motor vehicle accident. Her car was hit from behind while stopped at a light, with the force of impact sufficient to deploy the airbags in both vehicles. When the paramedics arrive, the patient is conscious and responsive but is found to have a rapid pulse (approximately 170 beats/min). During transport to the hospital, her tachycardia abruptly terminates and sinus rhythm returns at rates between 80 and 90 beats/min. In the emergency department, the patient’s physical examination and x-rays reveal no injuries. Review of the rhythm strips from the paramedics in the field shows a narrow complex tachycardia at a rate of 176 beats/min. When interviewed, the patient reveals a history of palpitations, lasting from five minutes up to two hours, over the past several years. When they occur, she says, she gets dizzy and feels a pounding sensation in her chest, but she has never had chest pain or syncope. She cannot identify any specific trigger that initiates her palpitations, but has noticed that if she holds her breath and bears down (Valsalva maneuver), her palpitations will sometimes stop. Her medical history is positive for mild asthma and an allergy to peanuts. She is taking no medications and denies tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use. Family history is remarkable for hypertension (father) and type 2 diabetes (mother). She is the oldest of three children, and one of her sisters experiences similar bouts of palpitations. A 14-point review of systems is negative. She denies she could be pregnant; she is currently menstruating. She is 61” tall, weighs 110 lb, and is of small stature and body habitus. She is in no acute distress. Her blood pressure is 110/72 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min and regular; and respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min. The physical exam is unremarkable, with the exception of abrasions on her hands and left forearm. Given the documentation of a tachycardia by the paramedics in the field and a history of recurring palpitations, an ECG is obtained, which reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 77 beats/min; PR interval, 128 ms; QRS duration, 116 ms; QT/QTc interval, 416/470 ms; P axis, 61°; R axis, 98°; and T axis, 5°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Rash Emerges After 18 Holes of Golf

ANSWER

The correct answer is golfer’s vasculitis (choice “d”), which favors older patients who spend extended periods on their feet in hot weather.

Schamberg’s disease (choice “a”), a type of capillaritis, presents with nonblanchable, true purpura that are classically described and seen as having a peculiar brown color (which has been called cinnamon or cayenne pepper).

Those who experience a true contact dermatitis (choice “b”) almost invariably itch and would most likely present with vesiculation of the skin surface.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV; choice “c”) presents as a nonblanchable purpuric condition that, on biopsy, demonstrates classic findings of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation from venules damaged by neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

“Golfer’s vasculitis” has been described in nongolfers who are older and who have spent considerable time on their feet in hot weather. Fair-goers, amusement park patrons, and hikers are just as likely to develop it, but it was first studied in golfers—and at first, it was thought to represent a sensitivity to chemical grass treatment.

However, the lack of symptoms and vesiculation (blistering) suggested otherwise, and biopsies of the affected skin confirmed gravity-related hyperemia with mild extravasation of RBCs. They also failed to show any signs of contact dermatitis. The sharply defined linear inferior border of the rash is clearly caused by the compressive effects of socks, which prevent the leakage of RBCs.

The other items in the differential were rightly considered—particularly LCV, which can be associated with conditions such as hypersensitivity reactions to medications or can be a presenting sign of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, among several other possibilities. But the key differentiating finding was the highly blanchable nature of this patient’s condition, in marked contrast to the nonblanchable, purpuric nature of classic LCV.

Often enough, blanchability is partial, or at least questionable, and a punch biopsy is necessary to clarify the picture. When histologic signs of LCV are found, blood work is necessary to rule out similar damage to “end organs,” such as kidneys and liver, as well as to attempt to establish the causative trigger.

ANSWER

The correct answer is golfer’s vasculitis (choice “d”), which favors older patients who spend extended periods on their feet in hot weather.

Schamberg’s disease (choice “a”), a type of capillaritis, presents with nonblanchable, true purpura that are classically described and seen as having a peculiar brown color (which has been called cinnamon or cayenne pepper).

Those who experience a true contact dermatitis (choice “b”) almost invariably itch and would most likely present with vesiculation of the skin surface.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV; choice “c”) presents as a nonblanchable purpuric condition that, on biopsy, demonstrates classic findings of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation from venules damaged by neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

“Golfer’s vasculitis” has been described in nongolfers who are older and who have spent considerable time on their feet in hot weather. Fair-goers, amusement park patrons, and hikers are just as likely to develop it, but it was first studied in golfers—and at first, it was thought to represent a sensitivity to chemical grass treatment.

However, the lack of symptoms and vesiculation (blistering) suggested otherwise, and biopsies of the affected skin confirmed gravity-related hyperemia with mild extravasation of RBCs. They also failed to show any signs of contact dermatitis. The sharply defined linear inferior border of the rash is clearly caused by the compressive effects of socks, which prevent the leakage of RBCs.

The other items in the differential were rightly considered—particularly LCV, which can be associated with conditions such as hypersensitivity reactions to medications or can be a presenting sign of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, among several other possibilities. But the key differentiating finding was the highly blanchable nature of this patient’s condition, in marked contrast to the nonblanchable, purpuric nature of classic LCV.

Often enough, blanchability is partial, or at least questionable, and a punch biopsy is necessary to clarify the picture. When histologic signs of LCV are found, blood work is necessary to rule out similar damage to “end organs,” such as kidneys and liver, as well as to attempt to establish the causative trigger.

ANSWER

The correct answer is golfer’s vasculitis (choice “d”), which favors older patients who spend extended periods on their feet in hot weather.

Schamberg’s disease (choice “a”), a type of capillaritis, presents with nonblanchable, true purpura that are classically described and seen as having a peculiar brown color (which has been called cinnamon or cayenne pepper).

Those who experience a true contact dermatitis (choice “b”) almost invariably itch and would most likely present with vesiculation of the skin surface.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV; choice “c”) presents as a nonblanchable purpuric condition that, on biopsy, demonstrates classic findings of red blood cell (RBC) extravasation from venules damaged by neutrophils.

DISCUSSION

“Golfer’s vasculitis” has been described in nongolfers who are older and who have spent considerable time on their feet in hot weather. Fair-goers, amusement park patrons, and hikers are just as likely to develop it, but it was first studied in golfers—and at first, it was thought to represent a sensitivity to chemical grass treatment.

However, the lack of symptoms and vesiculation (blistering) suggested otherwise, and biopsies of the affected skin confirmed gravity-related hyperemia with mild extravasation of RBCs. They also failed to show any signs of contact dermatitis. The sharply defined linear inferior border of the rash is clearly caused by the compressive effects of socks, which prevent the leakage of RBCs.

The other items in the differential were rightly considered—particularly LCV, which can be associated with conditions such as hypersensitivity reactions to medications or can be a presenting sign of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, among several other possibilities. But the key differentiating finding was the highly blanchable nature of this patient’s condition, in marked contrast to the nonblanchable, purpuric nature of classic LCV.

Often enough, blanchability is partial, or at least questionable, and a punch biopsy is necessary to clarify the picture. When histologic signs of LCV are found, blood work is necessary to rule out similar damage to “end organs,” such as kidneys and liver, as well as to attempt to establish the causative trigger.

When an asymptomatic rash appeared rather suddenly on both of her legs, a 54-year-old woman sought medical evaluation by her primary care provider. He diagnosed contact dermatitis and prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Forty-eight hours later, with no signs of improvement evident, the patient seeks and is granted a same-day appointment with dermatology. The patient denies any previous occurrences of such a rash and further denies having joint pain, fever, or malaise. She had not taken any new medications prior to the rash’s onset; furthermore, she only occasionally uses OTC medicines. A thorough history reveals that two days before the rash appeared, on one of the first hot days of the summer (with a temperature above 95°F), the woman played 18 holes of golf. The rash itself is strikingly red and affects both lower legs symmetrically, from mid-calf to just above the ankles. There, it ends abruptly with a linear, transverse border. There is no tenderness or increased warmth appreciated on palpation, nor is there any nodularity, vesiculation, or other disruption of the skin’s surface. Distinct, complete blanching is noted on firm digital palpation.

Severe Injury After Being Struck by a Car

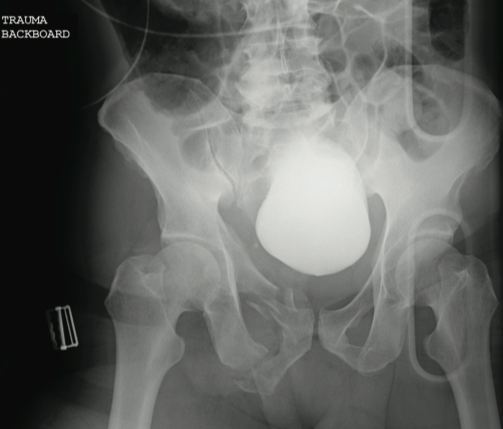

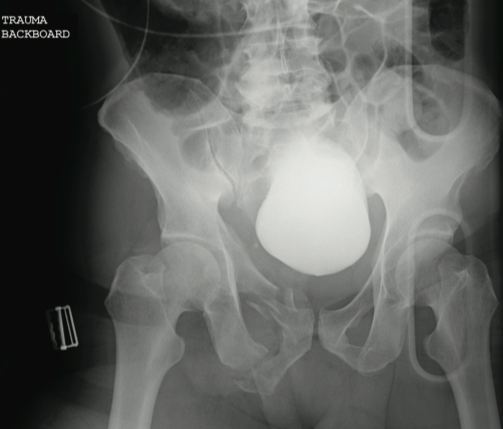

The radiograph reveals several findings. First, there are obvious displaced fractures of the right superior and inferior rami bones. There is also a diastatic fracture of the left sacroiliac joint.

Also, as the bladder is full of contrast (probably from a recent cystogram), note how it appears to be displaced to a more superior position than usual. This is second- ary to formation of a pelvic hematoma.

The radiograph reveals several findings. First, there are obvious displaced fractures of the right superior and inferior rami bones. There is also a diastatic fracture of the left sacroiliac joint.

Also, as the bladder is full of contrast (probably from a recent cystogram), note how it appears to be displaced to a more superior position than usual. This is second- ary to formation of a pelvic hematoma.

The radiograph reveals several findings. First, there are obvious displaced fractures of the right superior and inferior rami bones. There is also a diastatic fracture of the left sacroiliac joint.

Also, as the bladder is full of contrast (probably from a recent cystogram), note how it appears to be displaced to a more superior position than usual. This is second- ary to formation of a pelvic hematoma.

A 59-year-old man was struck by a car while walking. He was initially evaluated at another facility, intubated, resuscitated, and stabilized, then transferred to your facility. He is believed to have a severe head injury and possibly other internal injuries. The man is unresponsive on arrival at your facility. No medical history is available. His vital signs are stable, with a blood pressure of 113/74 mm Hg; heart rate, 101 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min. Initial Glasgow Coma Scale score is reported as a 3T. It is unclear whether the patient has recently received any sedation. As you are reviewing the results of testing conducted at both your facility and the facility to which the patient was originally taken, you see a portable pelvic radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

Landscaper Can't Outrun Tree

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an osseous fragment along the inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Close examination reveals a defect within the scapula itself, most likely consistent with an acute fracture.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an osseous fragment along the inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Close examination reveals a defect within the scapula itself, most likely consistent with an acute fracture.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an osseous fragment along the inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Close examination reveals a defect within the scapula itself, most likely consistent with an acute fracture.

A 24-year-old man who works as a landscaper/tree-cutter presents for evaluation of right shoulder pain after a tree fell on him. He states that he attempted to run away as the tree fell, but it struck him nonetheless. He did not lose consciousness. The tree struck the right side of his body. The patient’s medical history is unremarkable. He is complaining of right-side back and shoulder pain. Initial vital signs and primary survey appear to be normal. Secondary survey shows decreased range of motion in the right shoulder, with point tenderness in the scapula. There are no obvious deformities. Distal pulses are strong, and the patient is otherwise neurovascularly intact. Radiograph of the right shoulder is shown. What is your impression?

Landscaper Can't Outrun Tree

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an osseous fragment along the inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Close examination reveals a defect within the scapula itself, most likely consistent with an acute fracture.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an osseous fragment along the inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Close examination reveals a defect within the scapula itself, most likely consistent with an acute fracture.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows an osseous fragment along the inferior aspect of the glenohumeral joint. Close examination reveals a defect within the scapula itself, most likely consistent with an acute fracture.

A 24-year-old man who works as a landscaper/tree-cutter presents for evaluation of right shoulder pain after a tree fell on him. He states that he attempted to run away as the tree fell, but it struck him nonetheless. He did not lose consciousness. The tree struck the right side of his body. The patient’s medical history is unremarkable. He is complaining of right-side back and shoulder pain. Initial vital signs and primary survey appear to be normal. Secondary survey shows decreased range of motion in the right shoulder, with point tenderness in the scapula. There are no obvious deformities. Distal pulses are strong, and the patient is otherwise neurovascularly intact. Radiograph of the right shoulder is shown. What is your impression?

Spreading Lesions on Sun-damaged Skin

ANSWER

The correct answer is idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (choice “d”), a common condition primarily seen on sun-damaged patients, but often mistaken for tinea versicolor (choice “b”).

Vitiligo (choice “a”) can present with “confetti” lesions, but would more likely lead to complete loss of pigment in most of the lesions, not the partial loss seen in this patient. Biopsy is indicated in questionable cases.

Tinea versicolor, equally common, is caused by a commensal yeast called Malassezia furfur that feeds on sebum, which is why it favors the oily parts of the body (back and chest, primarily). It is almost never seen on the legs, which have the fewest oil glands on the body. In addition, tinea versicolor is, by its nature, an epidermal process, leading to the formation of a fine KOH-positive scale.

Since lupus (choice “c”) is a form of vasculitis, the associated inflammation can lead to pigment loss, especially in darker-skinned patients. Without a more likely explanation for these lesions, a biopsy might well have been indicated.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy might have suggested any number of other diseases that can also present with hypomelanosis, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma or sarcoid. But idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is far more common, and the patient’s age, gender, and history of chronic UV damage all lend themselves perfectly to this diagnosis.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, for unknown reasons, tends to appear in women at earlier ages than in men (usually about a decade younger). For either gender, treatment is problematic once the lesions have fully developed. Early in the process, the obvious remedy is better sun protection. Lasers, retinoids, liquid nitrogen, and anti-inflammatory creams have all been tried with little success.

ANSWER

The correct answer is idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (choice “d”), a common condition primarily seen on sun-damaged patients, but often mistaken for tinea versicolor (choice “b”).

Vitiligo (choice “a”) can present with “confetti” lesions, but would more likely lead to complete loss of pigment in most of the lesions, not the partial loss seen in this patient. Biopsy is indicated in questionable cases.

Tinea versicolor, equally common, is caused by a commensal yeast called Malassezia furfur that feeds on sebum, which is why it favors the oily parts of the body (back and chest, primarily). It is almost never seen on the legs, which have the fewest oil glands on the body. In addition, tinea versicolor is, by its nature, an epidermal process, leading to the formation of a fine KOH-positive scale.

Since lupus (choice “c”) is a form of vasculitis, the associated inflammation can lead to pigment loss, especially in darker-skinned patients. Without a more likely explanation for these lesions, a biopsy might well have been indicated.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy might have suggested any number of other diseases that can also present with hypomelanosis, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma or sarcoid. But idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is far more common, and the patient’s age, gender, and history of chronic UV damage all lend themselves perfectly to this diagnosis.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, for unknown reasons, tends to appear in women at earlier ages than in men (usually about a decade younger). For either gender, treatment is problematic once the lesions have fully developed. Early in the process, the obvious remedy is better sun protection. Lasers, retinoids, liquid nitrogen, and anti-inflammatory creams have all been tried with little success.

ANSWER

The correct answer is idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (choice “d”), a common condition primarily seen on sun-damaged patients, but often mistaken for tinea versicolor (choice “b”).

Vitiligo (choice “a”) can present with “confetti” lesions, but would more likely lead to complete loss of pigment in most of the lesions, not the partial loss seen in this patient. Biopsy is indicated in questionable cases.

Tinea versicolor, equally common, is caused by a commensal yeast called Malassezia furfur that feeds on sebum, which is why it favors the oily parts of the body (back and chest, primarily). It is almost never seen on the legs, which have the fewest oil glands on the body. In addition, tinea versicolor is, by its nature, an epidermal process, leading to the formation of a fine KOH-positive scale.

Since lupus (choice “c”) is a form of vasculitis, the associated inflammation can lead to pigment loss, especially in darker-skinned patients. Without a more likely explanation for these lesions, a biopsy might well have been indicated.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy might have suggested any number of other diseases that can also present with hypomelanosis, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma or sarcoid. But idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis is far more common, and the patient’s age, gender, and history of chronic UV damage all lend themselves perfectly to this diagnosis.

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, for unknown reasons, tends to appear in women at earlier ages than in men (usually about a decade younger). For either gender, treatment is problematic once the lesions have fully developed. Early in the process, the obvious remedy is better sun protection. Lasers, retinoids, liquid nitrogen, and anti-inflammatory creams have all been tried with little success.

A few years ago, a woman first noticed lesions developing on her legs. The patient sought care from her primary care provider; however, despite a number of treatment regimens, including topical clotrimazole and terbinafine creams, the lesions have not only failed to resolve but have also grown in number and spread to other areas of her body. The woman, now 48, is referred to dermatology for evaluation of her persistent but asymptomatic condition. The patient claims that her health is otherwise excellent, although she has seasonal allergies, was a long-time smoker until two months ago, and has just begun estrogen replacement therapy. She is especially concerned that the lesions have started to appear on the skin of her abdomen. She specifically denies shortness of breath, joint pain, fever, unexplained weight loss, or cough. An examination of her skin reveals a multitude of 2- to 6-mm partially depigmented, roughly round macules uniformly distributed on her legs, arms, and trunk. The lesions, which average about 3 mm, have no palpable component and no observable scale or underlying induration. There is a concentration of them on the anterior tibial areas, as well as on the dorsal forearms; however, none are seen on her face, and the volar surfaces of her forearms are almost completely spared. Significantly, the patient’s exposed skin is tremendously sun-damaged, evidenced by a deep brown color and a weathered, wrinkled look, with many telangiectasias and brown to tan–orange macules on her face.