User login

Does hypertensive disease of pregnancy increase future risk of CVD?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

- Patients who develop preeclampsia or gestational hypertension in their first pregnancy should be more carefully screened for subsequent development of CVD

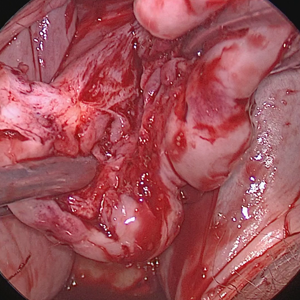

Excision of a Bartholin gland cyst

Bartholin gland cysts comprise up to 2% of all outpatient gynecology visits each year1 and are a common consult for trainees in obstetrics and gynecology. Although excision of a Bartholin gland cyst is a procedure performed infrequently, knowledge of its anatomy and physiology is important for ObGyn trainees and practicing gynecologists, especially when attempts at conservative management have been exhausted.

Before proceeding with surgical excision, it is important to understand the basics of Bartholin gland anatomy, pathologies, and treatment options. This video demonstrates the excisional technique for a 46-year-old woman with a recurrent, symptomatic Bartholin gland cyst who failed prior conservative management. I hope that you will find this video from my colleagues beneficial to your clinical practice.

- Marzano DA, Haefner HK. The bartholin gland cyst: past, present, and future. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2004;8(3):195–204.

Bartholin gland cysts comprise up to 2% of all outpatient gynecology visits each year1 and are a common consult for trainees in obstetrics and gynecology. Although excision of a Bartholin gland cyst is a procedure performed infrequently, knowledge of its anatomy and physiology is important for ObGyn trainees and practicing gynecologists, especially when attempts at conservative management have been exhausted.

Before proceeding with surgical excision, it is important to understand the basics of Bartholin gland anatomy, pathologies, and treatment options. This video demonstrates the excisional technique for a 46-year-old woman with a recurrent, symptomatic Bartholin gland cyst who failed prior conservative management. I hope that you will find this video from my colleagues beneficial to your clinical practice.

Bartholin gland cysts comprise up to 2% of all outpatient gynecology visits each year1 and are a common consult for trainees in obstetrics and gynecology. Although excision of a Bartholin gland cyst is a procedure performed infrequently, knowledge of its anatomy and physiology is important for ObGyn trainees and practicing gynecologists, especially when attempts at conservative management have been exhausted.

Before proceeding with surgical excision, it is important to understand the basics of Bartholin gland anatomy, pathologies, and treatment options. This video demonstrates the excisional technique for a 46-year-old woman with a recurrent, symptomatic Bartholin gland cyst who failed prior conservative management. I hope that you will find this video from my colleagues beneficial to your clinical practice.

- Marzano DA, Haefner HK. The bartholin gland cyst: past, present, and future. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2004;8(3):195–204.

- Marzano DA, Haefner HK. The bartholin gland cyst: past, present, and future. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2004;8(3):195–204.

ASCEND: Aspirin, fish oil flop in diabetes

MUNICH – In a double blow to the current, widespread routine use of low-dose aspirin and fish oil supplements for primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with diabetes, neither treatment provided any net clinical benefit in the massive, long-term ASCEND study, investigators reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

And, in yet another bitter pill to swallow, low-dose aspirin failed to reduce the incidence of GI cancer or any other type of cancer, compared with placebo in the study. Earlier, nondefinitive meta-analyses of much smaller randomized trials had raised the possibility of a roughly 30% reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancer in long-time users, said Jane Armitage, MD, professor of clinical trials and epidemiology at the University of Oxford (England).

“We saw no suggestion of an anticancer effect emerging over time,” Dr. Armitage said. “We did see a significant reduction in the risk of vascular events but also an increase in major bleeding such that the absolute benefits from avoiding a serious vascular event were largely counterbalanced by increased risk of bleeding. And there was no subgroup in which we could clearly define that the benefit outweighs the risk,” she added in a video interview.

ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) was a randomized, blinded trial in which 15,480 U.K. patients with diabetes and no known cardiovascular disease were placed on 100 mg/day of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo and 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids in capsule form or placebo in a 2 x 2 factorial design and followed prospectively for a mean of 7.4 years.

The study was undertaken because, even though the value of low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention is supported by strong evidence, the medication’s value for primary prevention in patients with diabetes has long been uncertain. American Diabetes Association guidelines give a Grade C recommendation to consideration of low-dose aspirin as a primary prevention strategy in patients with diabetes having a 10-year cardiovascular risk estimated at 10% or greater.

The primary efficacy endpoint in ASCEND was the occurrence of a first serious vascular event, defined as MI, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or death from any vascular cause other than intracranial hemorrhage. The rate was 8.5% in the aspirin group and 9.6% with placebo, for a statistically significant 12% relative risk reduction. However, the rate of the primary composite safety endpoint, comprising intracranial hemorrhage, GI bleeding, sight-threatening bleeding in the eye, or other bleeding serious enough to entail a trip to the hospital, was 4.1% in the aspirin group and 3.2% with placebo, a 29% increase in risk.

Aspirin reduced the absolute risk of a serious vascular event by 1.1%, compared with placebo, while boosting the risk of major bleeding by an absolute 0.9% – essentially a wash. The number needed to treat to avoid a serious vascular event was 91 patients, with 112 being the number needed to cause a major bleeding event. The risk of major bleeding rose with increasing baseline 5-year vascular event risk.

ASCEND provided no support for a recent report suggesting the benefit of low-dose aspirin for cardioprotection is largely confined to individuals weighing less than 70 kg (Lancet. 2018; 392:387-99); in fact, the opposite appeared to be true, according to Dr. Armitage.

The incidence of cancer of the GI tract was 2.0% in both study arms. The overall cancer rate was 11.6% in the aspirin arm and 11.5% with placebo. Additional follow-up focused on cancer is planned for 5 and 10 years after the end of ASCEND in order to examine the possibility of a delayed anticancer effect, she added.

Dr. Armitage said one reason aspirin may have failed to show a significant net benefit was the high rate of background cardioprotective medication usage, especially statins and antihypertensive drugs.

“I think if your diabetes is well managed and you’ve got your other risk factors under control, you have to consider very carefully whether or not, for you, the benefits of aspirin outweigh the risks,” she concluded.

Cardiologists respond

ASCEND’s two designated discussants, both cardiologists, took a more positive view of the results than Dr. Armitage, who isn’t a cardiologist.

Sigrun Halvorsen, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Oslo, noted that most ASCEND participants were at relatively low cardiovascular risk, with an event rate of about 1.3% per year. She indicated that she’d like to see more data on higher-risk individuals before excluding any role for aspirin in primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with diabetes.

“Serious vascular events and bleeding are not necessarily equally weighted,” she added. “Most major bleeds in ASCEND were GI bleeds, and these can be largely prevented by PPIs [proton pump inhibitors], in contrast to death and stroke, which are irreversible events.”

“I think this study could be interpreted more favorably,” agreed Christopher P. Cannon, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Bleeds are reversible, but MIs and whatnot are not.”

Fish oil flounders in ASCEND

Louise Bowman, MD, also at the University of Oxford, presented the ASCEND fish oil findings. Over an average of 7.4 years, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation had no effect on the rate of serious vascular events, no effect on cancer, no impact on all-cause or cause-specific mortality, and raised no safety issues in patients with diabetes. She argued that current guidelines recommending fish oil supplements for cardiovascular prevention should be reconsidered.

“Certainly there doesn’t seem to be any justification for the use of this dose of omega-3 fatty acids – 1 g/day – for the prevention of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Bowman said.

However, Dr. Cannon saw a sliver of hope within the ASCEND findings. One component of the serious vascular event composite endpoint – vascular death – occurred in 2.4% of the fish oil group and 2.9% of placebo-treated controls, for a statistically significant 19% relative risk reduction. It could be a fluke, given that none of the other vascular endpoints followed suit. But physicians and patients won’t have to wait long to find out. Another randomized trial of low-dose fish oil supplements for primary cardiovascular prevention – the nearly 26,000-patient VITAL trial – is due to report later in 2018.

In addition, two major, randomized trials of higher-dose fish oil supplementation for secondary prevention are ongoing. The roughly 8,000-patient REDUCE-IT trial is expected to report results later this year, and the STRENGTH trial, featuring more than 13,000 patients, should be completed in 2020. Both studies are heavily loaded with diabetes patients, Dr. Cannon noted.

Simultaneous with presentation of the ASCEND results at the ESC congress, the study was published online at the New England Journal of Medicine website (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988 and doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804989).

The ASCEND study was funded by the British Heart Foundation and the U.K. Medical Research Council with support provided by Abbott Laboratories, Bayer, Mylan, and Solvay. Dr. Armitage and Dr. Bowman reported receiving research grants from the Medicines Company, Bayer, and Mylan. Dr. Halvorsen reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Cannon reported serving as a consultant to roughly a dozen pharmaceutical companies, including the Amarin Corporation, which markets a fish oil supplement and sponsored the REDUCE-IT trial.

MUNICH – In a double blow to the current, widespread routine use of low-dose aspirin and fish oil supplements for primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with diabetes, neither treatment provided any net clinical benefit in the massive, long-term ASCEND study, investigators reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

And, in yet another bitter pill to swallow, low-dose aspirin failed to reduce the incidence of GI cancer or any other type of cancer, compared with placebo in the study. Earlier, nondefinitive meta-analyses of much smaller randomized trials had raised the possibility of a roughly 30% reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancer in long-time users, said Jane Armitage, MD, professor of clinical trials and epidemiology at the University of Oxford (England).

“We saw no suggestion of an anticancer effect emerging over time,” Dr. Armitage said. “We did see a significant reduction in the risk of vascular events but also an increase in major bleeding such that the absolute benefits from avoiding a serious vascular event were largely counterbalanced by increased risk of bleeding. And there was no subgroup in which we could clearly define that the benefit outweighs the risk,” she added in a video interview.

ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) was a randomized, blinded trial in which 15,480 U.K. patients with diabetes and no known cardiovascular disease were placed on 100 mg/day of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo and 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids in capsule form or placebo in a 2 x 2 factorial design and followed prospectively for a mean of 7.4 years.

The study was undertaken because, even though the value of low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention is supported by strong evidence, the medication’s value for primary prevention in patients with diabetes has long been uncertain. American Diabetes Association guidelines give a Grade C recommendation to consideration of low-dose aspirin as a primary prevention strategy in patients with diabetes having a 10-year cardiovascular risk estimated at 10% or greater.

The primary efficacy endpoint in ASCEND was the occurrence of a first serious vascular event, defined as MI, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or death from any vascular cause other than intracranial hemorrhage. The rate was 8.5% in the aspirin group and 9.6% with placebo, for a statistically significant 12% relative risk reduction. However, the rate of the primary composite safety endpoint, comprising intracranial hemorrhage, GI bleeding, sight-threatening bleeding in the eye, or other bleeding serious enough to entail a trip to the hospital, was 4.1% in the aspirin group and 3.2% with placebo, a 29% increase in risk.

Aspirin reduced the absolute risk of a serious vascular event by 1.1%, compared with placebo, while boosting the risk of major bleeding by an absolute 0.9% – essentially a wash. The number needed to treat to avoid a serious vascular event was 91 patients, with 112 being the number needed to cause a major bleeding event. The risk of major bleeding rose with increasing baseline 5-year vascular event risk.

ASCEND provided no support for a recent report suggesting the benefit of low-dose aspirin for cardioprotection is largely confined to individuals weighing less than 70 kg (Lancet. 2018; 392:387-99); in fact, the opposite appeared to be true, according to Dr. Armitage.

The incidence of cancer of the GI tract was 2.0% in both study arms. The overall cancer rate was 11.6% in the aspirin arm and 11.5% with placebo. Additional follow-up focused on cancer is planned for 5 and 10 years after the end of ASCEND in order to examine the possibility of a delayed anticancer effect, she added.

Dr. Armitage said one reason aspirin may have failed to show a significant net benefit was the high rate of background cardioprotective medication usage, especially statins and antihypertensive drugs.

“I think if your diabetes is well managed and you’ve got your other risk factors under control, you have to consider very carefully whether or not, for you, the benefits of aspirin outweigh the risks,” she concluded.

Cardiologists respond

ASCEND’s two designated discussants, both cardiologists, took a more positive view of the results than Dr. Armitage, who isn’t a cardiologist.

Sigrun Halvorsen, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Oslo, noted that most ASCEND participants were at relatively low cardiovascular risk, with an event rate of about 1.3% per year. She indicated that she’d like to see more data on higher-risk individuals before excluding any role for aspirin in primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with diabetes.

“Serious vascular events and bleeding are not necessarily equally weighted,” she added. “Most major bleeds in ASCEND were GI bleeds, and these can be largely prevented by PPIs [proton pump inhibitors], in contrast to death and stroke, which are irreversible events.”

“I think this study could be interpreted more favorably,” agreed Christopher P. Cannon, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Bleeds are reversible, but MIs and whatnot are not.”

Fish oil flounders in ASCEND

Louise Bowman, MD, also at the University of Oxford, presented the ASCEND fish oil findings. Over an average of 7.4 years, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation had no effect on the rate of serious vascular events, no effect on cancer, no impact on all-cause or cause-specific mortality, and raised no safety issues in patients with diabetes. She argued that current guidelines recommending fish oil supplements for cardiovascular prevention should be reconsidered.

“Certainly there doesn’t seem to be any justification for the use of this dose of omega-3 fatty acids – 1 g/day – for the prevention of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Bowman said.

However, Dr. Cannon saw a sliver of hope within the ASCEND findings. One component of the serious vascular event composite endpoint – vascular death – occurred in 2.4% of the fish oil group and 2.9% of placebo-treated controls, for a statistically significant 19% relative risk reduction. It could be a fluke, given that none of the other vascular endpoints followed suit. But physicians and patients won’t have to wait long to find out. Another randomized trial of low-dose fish oil supplements for primary cardiovascular prevention – the nearly 26,000-patient VITAL trial – is due to report later in 2018.

In addition, two major, randomized trials of higher-dose fish oil supplementation for secondary prevention are ongoing. The roughly 8,000-patient REDUCE-IT trial is expected to report results later this year, and the STRENGTH trial, featuring more than 13,000 patients, should be completed in 2020. Both studies are heavily loaded with diabetes patients, Dr. Cannon noted.

Simultaneous with presentation of the ASCEND results at the ESC congress, the study was published online at the New England Journal of Medicine website (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988 and doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804989).

The ASCEND study was funded by the British Heart Foundation and the U.K. Medical Research Council with support provided by Abbott Laboratories, Bayer, Mylan, and Solvay. Dr. Armitage and Dr. Bowman reported receiving research grants from the Medicines Company, Bayer, and Mylan. Dr. Halvorsen reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Cannon reported serving as a consultant to roughly a dozen pharmaceutical companies, including the Amarin Corporation, which markets a fish oil supplement and sponsored the REDUCE-IT trial.

MUNICH – In a double blow to the current, widespread routine use of low-dose aspirin and fish oil supplements for primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with diabetes, neither treatment provided any net clinical benefit in the massive, long-term ASCEND study, investigators reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

And, in yet another bitter pill to swallow, low-dose aspirin failed to reduce the incidence of GI cancer or any other type of cancer, compared with placebo in the study. Earlier, nondefinitive meta-analyses of much smaller randomized trials had raised the possibility of a roughly 30% reduction in the incidence of colorectal cancer in long-time users, said Jane Armitage, MD, professor of clinical trials and epidemiology at the University of Oxford (England).

“We saw no suggestion of an anticancer effect emerging over time,” Dr. Armitage said. “We did see a significant reduction in the risk of vascular events but also an increase in major bleeding such that the absolute benefits from avoiding a serious vascular event were largely counterbalanced by increased risk of bleeding. And there was no subgroup in which we could clearly define that the benefit outweighs the risk,” she added in a video interview.

ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) was a randomized, blinded trial in which 15,480 U.K. patients with diabetes and no known cardiovascular disease were placed on 100 mg/day of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo and 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids in capsule form or placebo in a 2 x 2 factorial design and followed prospectively for a mean of 7.4 years.

The study was undertaken because, even though the value of low-dose aspirin for secondary prevention is supported by strong evidence, the medication’s value for primary prevention in patients with diabetes has long been uncertain. American Diabetes Association guidelines give a Grade C recommendation to consideration of low-dose aspirin as a primary prevention strategy in patients with diabetes having a 10-year cardiovascular risk estimated at 10% or greater.

The primary efficacy endpoint in ASCEND was the occurrence of a first serious vascular event, defined as MI, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or death from any vascular cause other than intracranial hemorrhage. The rate was 8.5% in the aspirin group and 9.6% with placebo, for a statistically significant 12% relative risk reduction. However, the rate of the primary composite safety endpoint, comprising intracranial hemorrhage, GI bleeding, sight-threatening bleeding in the eye, or other bleeding serious enough to entail a trip to the hospital, was 4.1% in the aspirin group and 3.2% with placebo, a 29% increase in risk.

Aspirin reduced the absolute risk of a serious vascular event by 1.1%, compared with placebo, while boosting the risk of major bleeding by an absolute 0.9% – essentially a wash. The number needed to treat to avoid a serious vascular event was 91 patients, with 112 being the number needed to cause a major bleeding event. The risk of major bleeding rose with increasing baseline 5-year vascular event risk.

ASCEND provided no support for a recent report suggesting the benefit of low-dose aspirin for cardioprotection is largely confined to individuals weighing less than 70 kg (Lancet. 2018; 392:387-99); in fact, the opposite appeared to be true, according to Dr. Armitage.

The incidence of cancer of the GI tract was 2.0% in both study arms. The overall cancer rate was 11.6% in the aspirin arm and 11.5% with placebo. Additional follow-up focused on cancer is planned for 5 and 10 years after the end of ASCEND in order to examine the possibility of a delayed anticancer effect, she added.

Dr. Armitage said one reason aspirin may have failed to show a significant net benefit was the high rate of background cardioprotective medication usage, especially statins and antihypertensive drugs.

“I think if your diabetes is well managed and you’ve got your other risk factors under control, you have to consider very carefully whether or not, for you, the benefits of aspirin outweigh the risks,” she concluded.

Cardiologists respond

ASCEND’s two designated discussants, both cardiologists, took a more positive view of the results than Dr. Armitage, who isn’t a cardiologist.

Sigrun Halvorsen, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of Oslo, noted that most ASCEND participants were at relatively low cardiovascular risk, with an event rate of about 1.3% per year. She indicated that she’d like to see more data on higher-risk individuals before excluding any role for aspirin in primary cardiovascular prevention in patients with diabetes.

“Serious vascular events and bleeding are not necessarily equally weighted,” she added. “Most major bleeds in ASCEND were GI bleeds, and these can be largely prevented by PPIs [proton pump inhibitors], in contrast to death and stroke, which are irreversible events.”

“I think this study could be interpreted more favorably,” agreed Christopher P. Cannon, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Bleeds are reversible, but MIs and whatnot are not.”

Fish oil flounders in ASCEND

Louise Bowman, MD, also at the University of Oxford, presented the ASCEND fish oil findings. Over an average of 7.4 years, omega-3 fatty acid supplementation had no effect on the rate of serious vascular events, no effect on cancer, no impact on all-cause or cause-specific mortality, and raised no safety issues in patients with diabetes. She argued that current guidelines recommending fish oil supplements for cardiovascular prevention should be reconsidered.

“Certainly there doesn’t seem to be any justification for the use of this dose of omega-3 fatty acids – 1 g/day – for the prevention of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Bowman said.

However, Dr. Cannon saw a sliver of hope within the ASCEND findings. One component of the serious vascular event composite endpoint – vascular death – occurred in 2.4% of the fish oil group and 2.9% of placebo-treated controls, for a statistically significant 19% relative risk reduction. It could be a fluke, given that none of the other vascular endpoints followed suit. But physicians and patients won’t have to wait long to find out. Another randomized trial of low-dose fish oil supplements for primary cardiovascular prevention – the nearly 26,000-patient VITAL trial – is due to report later in 2018.

In addition, two major, randomized trials of higher-dose fish oil supplementation for secondary prevention are ongoing. The roughly 8,000-patient REDUCE-IT trial is expected to report results later this year, and the STRENGTH trial, featuring more than 13,000 patients, should be completed in 2020. Both studies are heavily loaded with diabetes patients, Dr. Cannon noted.

Simultaneous with presentation of the ASCEND results at the ESC congress, the study was published online at the New England Journal of Medicine website (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988 and doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804989).

The ASCEND study was funded by the British Heart Foundation and the U.K. Medical Research Council with support provided by Abbott Laboratories, Bayer, Mylan, and Solvay. Dr. Armitage and Dr. Bowman reported receiving research grants from the Medicines Company, Bayer, and Mylan. Dr. Halvorsen reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Cannon reported serving as a consultant to roughly a dozen pharmaceutical companies, including the Amarin Corporation, which markets a fish oil supplement and sponsored the REDUCE-IT trial.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Low-dose aspirin reduced the risk of serious vascular events by 12% versus placebo, but boosted major bleeding events by 29%.

Study details: This prospective, randomized trial included 15,480 patients with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease who were randomized to 100 mg/day of enteric-coated aspirin or placebo and 1 g/day of omega-3 fatty acids or placebo and followed for a mean of 7.4 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the British Heart Foundation and the U.K. Medical Research Council with support provided by Abbott Laboratories, Bayer, Mylan, and Solvay. The presenters reported receiving research grants from the Medicines Company, Bayer, and Mylan.

Lorcaserin shows CV safety in CAMELLIA-TIMI 61

MUNICH – Lorcaserin is the first weight-loss drug proven to have cardiovascular safety, Erin A. Bohula, MD, DPhil, told Mitchel L. Zoler in an interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Bohula reported on the results of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, which was designed to evaluate the cardiovascular safety of the weight-loss drug lorcaserin in more than 10,000 patients. She presented the data at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In CAMELLIA-TIMI 61, the primary safety endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, was nearly identical between patients on lorcaserin and those given placebo, 2% and 2.1% per year, at P less than .001 for noninferiority. Similarly, the primary efficacy outcome comprising heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization, was very close between the treated and placebo patients, occurring in 4.1% and 4.2% per year, respectively.

In addition, “there was a sustained weight loss, more than with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus placebo, which at its peak was about 3 kg. With that there were small, but significant, reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c, and there was a significant reduction in new-onset diabetes.”

“Overall, there’s not a lot of use of pharmacologic agents for weight loss in the United States, and a lot of that is based on fear of the historical experience, which is that they were not safe. I suspect that having a drug that is proven safe will now lead people to reach for a pharmacologic agent like lorcaserin,” said Dr. Bohula, a cardiologist at of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an investigator at the TIMI study group.

MUNICH – Lorcaserin is the first weight-loss drug proven to have cardiovascular safety, Erin A. Bohula, MD, DPhil, told Mitchel L. Zoler in an interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Bohula reported on the results of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, which was designed to evaluate the cardiovascular safety of the weight-loss drug lorcaserin in more than 10,000 patients. She presented the data at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In CAMELLIA-TIMI 61, the primary safety endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, was nearly identical between patients on lorcaserin and those given placebo, 2% and 2.1% per year, at P less than .001 for noninferiority. Similarly, the primary efficacy outcome comprising heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization, was very close between the treated and placebo patients, occurring in 4.1% and 4.2% per year, respectively.

In addition, “there was a sustained weight loss, more than with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus placebo, which at its peak was about 3 kg. With that there were small, but significant, reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c, and there was a significant reduction in new-onset diabetes.”

“Overall, there’s not a lot of use of pharmacologic agents for weight loss in the United States, and a lot of that is based on fear of the historical experience, which is that they were not safe. I suspect that having a drug that is proven safe will now lead people to reach for a pharmacologic agent like lorcaserin,” said Dr. Bohula, a cardiologist at of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an investigator at the TIMI study group.

MUNICH – Lorcaserin is the first weight-loss drug proven to have cardiovascular safety, Erin A. Bohula, MD, DPhil, told Mitchel L. Zoler in an interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Bohula reported on the results of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, which was designed to evaluate the cardiovascular safety of the weight-loss drug lorcaserin in more than 10,000 patients. She presented the data at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In CAMELLIA-TIMI 61, the primary safety endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, was nearly identical between patients on lorcaserin and those given placebo, 2% and 2.1% per year, at P less than .001 for noninferiority. Similarly, the primary efficacy outcome comprising heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization, was very close between the treated and placebo patients, occurring in 4.1% and 4.2% per year, respectively.

In addition, “there was a sustained weight loss, more than with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus placebo, which at its peak was about 3 kg. With that there were small, but significant, reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c, and there was a significant reduction in new-onset diabetes.”

“Overall, there’s not a lot of use of pharmacologic agents for weight loss in the United States, and a lot of that is based on fear of the historical experience, which is that they were not safe. I suspect that having a drug that is proven safe will now lead people to reach for a pharmacologic agent like lorcaserin,” said Dr. Bohula, a cardiologist at of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an investigator at the TIMI study group.

Lorcaserin shows CV safety in CAMELLIA-TIMI 61

Erin A. Bohula, MD, DPhil, told Mitchel L. Zoler in an interview.

Dr. Bohula reported on the results of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, which was designed to evaluate the cardiovascular safety of the weight-loss drug lorcaserin in more than 10,000 patients. She presented the data at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In CAMELLIA-TIMI 61, the primary safety endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, was nearly identical between patients on lorcaserin and those given placebo, 2% and 2.1% per year, at P less than .001 for noninferiority. Similarly, the primary efficacy outcome comprising heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization, was very close between the treated and placebo patients, occurring in 4.1% and 4.2% per year, respectively.

In addition, “there was a sustained weight loss, more than with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus placebo, which at its peak was about 3 kg. With that there were small, but significant, reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c, and there was a significant reduction in new-onset diabetes.”

“Overall, there’s not a lot of use of pharmacologic agents for weight loss in the United States, and a lot of that is based on fear of the historical experience, which is that they were not safe. I suspect that having a drug that is proven safe will now lead people to reach for a pharmacologic agent like lorcaserin,” said Dr. Bohula, a cardiologist at of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an investigator at the TIMI study group.

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

Erin A. Bohula, MD, DPhil, told Mitchel L. Zoler in an interview.

Dr. Bohula reported on the results of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, which was designed to evaluate the cardiovascular safety of the weight-loss drug lorcaserin in more than 10,000 patients. She presented the data at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In CAMELLIA-TIMI 61, the primary safety endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, was nearly identical between patients on lorcaserin and those given placebo, 2% and 2.1% per year, at P less than .001 for noninferiority. Similarly, the primary efficacy outcome comprising heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization, was very close between the treated and placebo patients, occurring in 4.1% and 4.2% per year, respectively.

In addition, “there was a sustained weight loss, more than with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus placebo, which at its peak was about 3 kg. With that there were small, but significant, reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c, and there was a significant reduction in new-onset diabetes.”

“Overall, there’s not a lot of use of pharmacologic agents for weight loss in the United States, and a lot of that is based on fear of the historical experience, which is that they were not safe. I suspect that having a drug that is proven safe will now lead people to reach for a pharmacologic agent like lorcaserin,” said Dr. Bohula, a cardiologist at of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an investigator at the TIMI study group.

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

Erin A. Bohula, MD, DPhil, told Mitchel L. Zoler in an interview.

Dr. Bohula reported on the results of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, which was designed to evaluate the cardiovascular safety of the weight-loss drug lorcaserin in more than 10,000 patients. She presented the data at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

In CAMELLIA-TIMI 61, the primary safety endpoint, a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, was nearly identical between patients on lorcaserin and those given placebo, 2% and 2.1% per year, at P less than .001 for noninferiority. Similarly, the primary efficacy outcome comprising heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and coronary revascularization, was very close between the treated and placebo patients, occurring in 4.1% and 4.2% per year, respectively.

In addition, “there was a sustained weight loss, more than with lifestyle alone or lifestyle plus placebo, which at its peak was about 3 kg. With that there were small, but significant, reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c, and there was a significant reduction in new-onset diabetes.”

“Overall, there’s not a lot of use of pharmacologic agents for weight loss in the United States, and a lot of that is based on fear of the historical experience, which is that they were not safe. I suspect that having a drug that is proven safe will now lead people to reach for a pharmacologic agent like lorcaserin,” said Dr. Bohula, a cardiologist at of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an investigator at the TIMI study group.

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at https://www.gastro.org/practice-guidance/practice-updates/obesity-practice-guide.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

This video is brought to you by

Latex Allergy From Biologic Injectable Devices

The second victim: More ob.gyn. organizations recognize need for support

When Patrice Weiss, MD, was a resident, a healthy, low-risk patient underwent what should have been an uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy. But the patient developed a series of postoperative complications leading to multisystem organ failure and a lengthy stay in intensive care.

“None of us could really figure out how this happened. I still can’t figure out how this person who was relatively young developed all these complications,” said Dr. Weiss, now chief medical officer of Carilion Clinic and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, both in Roanoke, Va. “There are times when you don’t know why something happened or what you could have done differently – and the answer may be nothing – but that dramatic, potentially very complicated outcome can really weigh on people. You still harbor those feelings of a second victim.”

It’s the health care professional who is that “second victim,” a term coined in 2000 by Albert W. Wu, MD, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to describe an increasingly recognized phenomenon following unexpected adverse patient events, medical errors, or patient injuries (BMJ. 2000 Mar 18;320[7237]:726-7). The patients and their loved ones are the first victims, but a health care professional’s feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and other powerful, complicated emotions can have long-lasting effects on his or her psyche, clinical practice, and career, particularly if he or she does not receive validation, support, and access to resources to work through the experience.

“Second victims ... become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event,” Susan D. Scott, PhD, of the University of Missouri Health System, Columbia, and her colleagues wrote in a 2009 paper about the phenomenon (Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18[5]:325-30). “Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base,” they said.

It’s that latter part that can fester and potentially poison a health care professional’s ability to function, according to Charlie Jaynes, MD, senior director of medical operations for Ob Hospitalist Group in Greenville, S.C.

“ and therefore can have a direct effect on patient care and lead to poor outcomes,” Dr. Jaynes said. “It’s a very dangerous phenomenon because it can degrade the quality of medical care provided.”

Most physicians are trained to internalize and compartmentalize these experiences, to “suck it up and get on with it,” he said, but it’s now become clear that such a strategy can have disastrous professional and personal consequences.

“In the worst case scenario, people burn out, drop out or commit suicide, their marriage ends up in shambles, or they turn to drugs and alcohol,” Dr. Jaynes said. “What Dr. Wu did was open the box to allow some empathy and compassion to be introduced to the situation.”

Dangers of unaddressed second victim impact

Estimates vary widely on the prevalence of second victim phenomenon among physicians and nurses who have been involved in a medical error or unexpected serious outcome. Across the medical field, estimates range from 10% in a study among otolaryngologists (Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116[7]:1114-20) to up to 30% and 50% more broadly, although some fields may be more susceptible than others (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36[5]:233-40; BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21[4]:267-70).

“In the world of obstetrics, we spend 99.9% of our time in a happy field of medicine filled with joy and new life,” Dr. Weiss said. “Whether consciously or unconsciously, those become the expectations of the patients and the providers, so when there is an outcome that is less than optimal, that’s when you’re even more affected because of what your expectations are going into it.”

Dr. Scott and her colleagues noted that the stages of being a second victim are similar to the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Stage 1: Chaos and event repair.

- Stage 2: Intrusive thoughts, “what if.”

- Stage 3: Restoring personal identity.

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition.

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid.

- Stage 6: Moving on or dropping out; surviving and/or thriving.”

“This can go on for years. Someone can spend years just surviving and not thriving,” Dr. Weiss said. “It can really happen along a continuum.”

Although studies have not looked specifically at second victims and patient care, research has shown that second victims have a higher risk of burnout, and that physicians with high burnout tend to order more tests, spend less time with patients, and have greater risk of making medical errors, Dr. Weiss said.

A study looking at the emotional impact of medical errors on physicians found that 61% had greater anxiety about making future medical errors, 44% had a loss of confidence, 42% had trouble sleeping, and 42% were less satisfied in their job (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

“You have the risk of the provider leaving medicine altogether or significantly changing their practice patterns, or giving up obstetric care because of the emotional toll it takes on providers,” she said. “We already know that one of the crises facing medicine right now is burnout, so you have the risk of additional or worsening burnout.”

Recognizing the need for formal support programs

Research does clearly show a need for programs formally addressing these experiences. A 2007 survey found that only 10% of 3,171 of internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, family physicians, and surgeons felt their health care organizations provided adequate support in managing stress following a medical error, yet about 8 in 10 wanted support (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

Organizations are responding. One of the first second-victim programs is the “forYOU” program implemented at the University of Missouri Health Care’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness in 2007. The free, 24-7 program provides a “safe zone” for expressing emotions and reactions confidentially.

Ob Hospitalist Group just launched the CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery & Encouragement) Program, the first national peer-support program for second victims. The first 25 volunteers who underwent training in September will serve the organization’s more than 700 health care professionals across 32 states.

Instead of psychological counseling or intervention, the program emphasizes active listening, nonjudgment, and compassion during confidential calls; peers don’t take notes or record the conversations.

“We will be quiet and listen and speak at the appropriate times to be compassionate and not make judgments,” Dr. Jaynes said. “I think its critical to realize that in order to do that you have to be one of us. If you haven’t been there yourself when a baby dies in utero or you have a mother almost die by hemorrhage or a complication of surgery ... it creates emotional turmoil. Everybody who’s worth their salt questions, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and we’re really harsh on ourselves. If I can say I realize it’s a horrible place to be because I’ve been there myself, I can be a useful peer.”

At Dr. Weiss’s institution, Carilion Clinic spent 5 years developing and implementing the TRUST second-victim program, emphasizing Treatment, Respect, Understanding/compassion, Supportive care, and Transparency. Dr. Weiss said the first step in developing such a program is talking about the problem.

“You need hospital leadership addressing the phenomenon of the second victim, recognizing it is real, that it’s not a sign of weakness for providers to have any of these signs,” she said. “It has to be done at an organizational level. There has to be a place where providers can talk freely about the emotional impact of the outcome, not just the clinical outcomes.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore published findings in September 2017 about its program RISE (Resilience In Stressful Events) (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017 Sep;43[9]:471-83 that was featured by the Joint Commission as a program that employs some of the tools the commission describes in its toolkit for health care organizations to develop second-victim support programs (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 May;38[5]:235-40, 193).

It’s important that health care professionals are not expected or required to seek counseling or similar interventions, Dr. Weiss said, but they know of available resources.

“People need to be able to talk about it when they’re ready. It doesn’t necessarily matter how your peers judge your actions because these are feelings that come from within,” Dr. Weiss said, although colleagues can validate a second victim’s experience or feelings by sharing their own.

“It’s helpful when someone in a leadership role can acknowledge that this is real and say to a provider, ‘I’ve been there, and this is what helped me,’ or ‘I’ve been there, and there was no resource and I went without help for years,’ ” she said.

In fact, it’s her own past experiences that have made Dr. Weiss so passionate about raising awareness about second victims.

“I’ve been involved in cases of unanticipated outcomes and personally witnessed medical errors, and I’ve seen how very close colleagues can be affected,” she said. “This is a topic that really, really hits home for me.”

Signs and symptoms: How to recognize a possible second victim

Anyone can become a second victim, regardless of their training, experience, or years of practice, Dr. Weiss said. A health care professional may practice for years and witness many unanticipated poor outcomes before one suddenly drums up feelings they don’t expect.

“It’s almost inevitable that providers are going to have unanticipated outcomes or unexpected outcomes,” Dr. Weiss said. “The challenge with the second victim is no one can ever predict how someone is going to respond to an outcome, including ourselves. This may be the first time they have a response to something they never saw coming.”

Two aspects correlated with a higher risk of second victim are the severity of the morbidity or mortality of the patient and the degree of personal responsibility the health care professional feels. The signs and symptoms of being a second victim can be indistinguishable from those of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress syndrome, but the biggest indicator is a change in a person’s normal behavior, Dr. Weiss said.

“The person who is never late to work is late to work. The person who is always mild-mannered is on edge,” she said. “A lot of it is subtle personality or behavior changes, or you begin to notice practice pattern differences, such as ordering a bunch of labs.”

Perhaps the providers are snapping at people when they’ve never snapped before, or they express more cynicism or sarcasm, she added. “A change in their sleeping or eating patterns or in their personal hygiene are all things that one could look for.”

According to Dr. Jaynes, emotional signs may include irritability, fear, anger, grief, remorse, frustration, desperation, numbness, guilt, loneliness, shock and feeling disconnected, feeling hopeless or out of control. Physical symptoms include headaches, muscle tension, chest pain, extreme fatigue, sleeping problems, appetite changes or gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, frequent illnesses, being easily startled, or increased heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing rate. Other possible signs include flashbacks, nightmares, social avoidance, difficulties concentrating, poor memory, avoiding patient care areas, fearing repercussions to their reputations, and decreased job satisfaction. Second victims also may experience a loss in confidence or spiritual connection, or loss of interest in work, usual activities, and connections with others.

Dr. Weiss and Dr. Jaynes said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

When Patrice Weiss, MD, was a resident, a healthy, low-risk patient underwent what should have been an uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy. But the patient developed a series of postoperative complications leading to multisystem organ failure and a lengthy stay in intensive care.

“None of us could really figure out how this happened. I still can’t figure out how this person who was relatively young developed all these complications,” said Dr. Weiss, now chief medical officer of Carilion Clinic and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, both in Roanoke, Va. “There are times when you don’t know why something happened or what you could have done differently – and the answer may be nothing – but that dramatic, potentially very complicated outcome can really weigh on people. You still harbor those feelings of a second victim.”

It’s the health care professional who is that “second victim,” a term coined in 2000 by Albert W. Wu, MD, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to describe an increasingly recognized phenomenon following unexpected adverse patient events, medical errors, or patient injuries (BMJ. 2000 Mar 18;320[7237]:726-7). The patients and their loved ones are the first victims, but a health care professional’s feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and other powerful, complicated emotions can have long-lasting effects on his or her psyche, clinical practice, and career, particularly if he or she does not receive validation, support, and access to resources to work through the experience.

“Second victims ... become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event,” Susan D. Scott, PhD, of the University of Missouri Health System, Columbia, and her colleagues wrote in a 2009 paper about the phenomenon (Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18[5]:325-30). “Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base,” they said.

It’s that latter part that can fester and potentially poison a health care professional’s ability to function, according to Charlie Jaynes, MD, senior director of medical operations for Ob Hospitalist Group in Greenville, S.C.

“ and therefore can have a direct effect on patient care and lead to poor outcomes,” Dr. Jaynes said. “It’s a very dangerous phenomenon because it can degrade the quality of medical care provided.”

Most physicians are trained to internalize and compartmentalize these experiences, to “suck it up and get on with it,” he said, but it’s now become clear that such a strategy can have disastrous professional and personal consequences.

“In the worst case scenario, people burn out, drop out or commit suicide, their marriage ends up in shambles, or they turn to drugs and alcohol,” Dr. Jaynes said. “What Dr. Wu did was open the box to allow some empathy and compassion to be introduced to the situation.”

Dangers of unaddressed second victim impact

Estimates vary widely on the prevalence of second victim phenomenon among physicians and nurses who have been involved in a medical error or unexpected serious outcome. Across the medical field, estimates range from 10% in a study among otolaryngologists (Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116[7]:1114-20) to up to 30% and 50% more broadly, although some fields may be more susceptible than others (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36[5]:233-40; BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21[4]:267-70).

“In the world of obstetrics, we spend 99.9% of our time in a happy field of medicine filled with joy and new life,” Dr. Weiss said. “Whether consciously or unconsciously, those become the expectations of the patients and the providers, so when there is an outcome that is less than optimal, that’s when you’re even more affected because of what your expectations are going into it.”

Dr. Scott and her colleagues noted that the stages of being a second victim are similar to the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Stage 1: Chaos and event repair.

- Stage 2: Intrusive thoughts, “what if.”

- Stage 3: Restoring personal identity.

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition.

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid.

- Stage 6: Moving on or dropping out; surviving and/or thriving.”

“This can go on for years. Someone can spend years just surviving and not thriving,” Dr. Weiss said. “It can really happen along a continuum.”

Although studies have not looked specifically at second victims and patient care, research has shown that second victims have a higher risk of burnout, and that physicians with high burnout tend to order more tests, spend less time with patients, and have greater risk of making medical errors, Dr. Weiss said.

A study looking at the emotional impact of medical errors on physicians found that 61% had greater anxiety about making future medical errors, 44% had a loss of confidence, 42% had trouble sleeping, and 42% were less satisfied in their job (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

“You have the risk of the provider leaving medicine altogether or significantly changing their practice patterns, or giving up obstetric care because of the emotional toll it takes on providers,” she said. “We already know that one of the crises facing medicine right now is burnout, so you have the risk of additional or worsening burnout.”

Recognizing the need for formal support programs

Research does clearly show a need for programs formally addressing these experiences. A 2007 survey found that only 10% of 3,171 of internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, family physicians, and surgeons felt their health care organizations provided adequate support in managing stress following a medical error, yet about 8 in 10 wanted support (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

Organizations are responding. One of the first second-victim programs is the “forYOU” program implemented at the University of Missouri Health Care’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness in 2007. The free, 24-7 program provides a “safe zone” for expressing emotions and reactions confidentially.

Ob Hospitalist Group just launched the CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery & Encouragement) Program, the first national peer-support program for second victims. The first 25 volunteers who underwent training in September will serve the organization’s more than 700 health care professionals across 32 states.

Instead of psychological counseling or intervention, the program emphasizes active listening, nonjudgment, and compassion during confidential calls; peers don’t take notes or record the conversations.

“We will be quiet and listen and speak at the appropriate times to be compassionate and not make judgments,” Dr. Jaynes said. “I think its critical to realize that in order to do that you have to be one of us. If you haven’t been there yourself when a baby dies in utero or you have a mother almost die by hemorrhage or a complication of surgery ... it creates emotional turmoil. Everybody who’s worth their salt questions, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and we’re really harsh on ourselves. If I can say I realize it’s a horrible place to be because I’ve been there myself, I can be a useful peer.”

At Dr. Weiss’s institution, Carilion Clinic spent 5 years developing and implementing the TRUST second-victim program, emphasizing Treatment, Respect, Understanding/compassion, Supportive care, and Transparency. Dr. Weiss said the first step in developing such a program is talking about the problem.

“You need hospital leadership addressing the phenomenon of the second victim, recognizing it is real, that it’s not a sign of weakness for providers to have any of these signs,” she said. “It has to be done at an organizational level. There has to be a place where providers can talk freely about the emotional impact of the outcome, not just the clinical outcomes.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore published findings in September 2017 about its program RISE (Resilience In Stressful Events) (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017 Sep;43[9]:471-83 that was featured by the Joint Commission as a program that employs some of the tools the commission describes in its toolkit for health care organizations to develop second-victim support programs (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 May;38[5]:235-40, 193).

It’s important that health care professionals are not expected or required to seek counseling or similar interventions, Dr. Weiss said, but they know of available resources.

“People need to be able to talk about it when they’re ready. It doesn’t necessarily matter how your peers judge your actions because these are feelings that come from within,” Dr. Weiss said, although colleagues can validate a second victim’s experience or feelings by sharing their own.

“It’s helpful when someone in a leadership role can acknowledge that this is real and say to a provider, ‘I’ve been there, and this is what helped me,’ or ‘I’ve been there, and there was no resource and I went without help for years,’ ” she said.

In fact, it’s her own past experiences that have made Dr. Weiss so passionate about raising awareness about second victims.

“I’ve been involved in cases of unanticipated outcomes and personally witnessed medical errors, and I’ve seen how very close colleagues can be affected,” she said. “This is a topic that really, really hits home for me.”

Signs and symptoms: How to recognize a possible second victim

Anyone can become a second victim, regardless of their training, experience, or years of practice, Dr. Weiss said. A health care professional may practice for years and witness many unanticipated poor outcomes before one suddenly drums up feelings they don’t expect.

“It’s almost inevitable that providers are going to have unanticipated outcomes or unexpected outcomes,” Dr. Weiss said. “The challenge with the second victim is no one can ever predict how someone is going to respond to an outcome, including ourselves. This may be the first time they have a response to something they never saw coming.”

Two aspects correlated with a higher risk of second victim are the severity of the morbidity or mortality of the patient and the degree of personal responsibility the health care professional feels. The signs and symptoms of being a second victim can be indistinguishable from those of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress syndrome, but the biggest indicator is a change in a person’s normal behavior, Dr. Weiss said.

“The person who is never late to work is late to work. The person who is always mild-mannered is on edge,” she said. “A lot of it is subtle personality or behavior changes, or you begin to notice practice pattern differences, such as ordering a bunch of labs.”

Perhaps the providers are snapping at people when they’ve never snapped before, or they express more cynicism or sarcasm, she added. “A change in their sleeping or eating patterns or in their personal hygiene are all things that one could look for.”

According to Dr. Jaynes, emotional signs may include irritability, fear, anger, grief, remorse, frustration, desperation, numbness, guilt, loneliness, shock and feeling disconnected, feeling hopeless or out of control. Physical symptoms include headaches, muscle tension, chest pain, extreme fatigue, sleeping problems, appetite changes or gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, frequent illnesses, being easily startled, or increased heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing rate. Other possible signs include flashbacks, nightmares, social avoidance, difficulties concentrating, poor memory, avoiding patient care areas, fearing repercussions to their reputations, and decreased job satisfaction. Second victims also may experience a loss in confidence or spiritual connection, or loss of interest in work, usual activities, and connections with others.

Dr. Weiss and Dr. Jaynes said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

When Patrice Weiss, MD, was a resident, a healthy, low-risk patient underwent what should have been an uncomplicated vaginal hysterectomy. But the patient developed a series of postoperative complications leading to multisystem organ failure and a lengthy stay in intensive care.

“None of us could really figure out how this happened. I still can’t figure out how this person who was relatively young developed all these complications,” said Dr. Weiss, now chief medical officer of Carilion Clinic and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and Research Institute, both in Roanoke, Va. “There are times when you don’t know why something happened or what you could have done differently – and the answer may be nothing – but that dramatic, potentially very complicated outcome can really weigh on people. You still harbor those feelings of a second victim.”

It’s the health care professional who is that “second victim,” a term coined in 2000 by Albert W. Wu, MD, professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to describe an increasingly recognized phenomenon following unexpected adverse patient events, medical errors, or patient injuries (BMJ. 2000 Mar 18;320[7237]:726-7). The patients and their loved ones are the first victims, but a health care professional’s feelings of guilt, shame, inadequacy, and other powerful, complicated emotions can have long-lasting effects on his or her psyche, clinical practice, and career, particularly if he or she does not receive validation, support, and access to resources to work through the experience.

“Second victims ... become victimized in the sense that the provider is traumatized by the event,” Susan D. Scott, PhD, of the University of Missouri Health System, Columbia, and her colleagues wrote in a 2009 paper about the phenomenon (Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18[5]:325-30). “Frequently, these individuals feel personally responsible for the patient outcome. Many feel as though they have failed the patient, second-guessing their clinical skills and knowledge base,” they said.

It’s that latter part that can fester and potentially poison a health care professional’s ability to function, according to Charlie Jaynes, MD, senior director of medical operations for Ob Hospitalist Group in Greenville, S.C.

“ and therefore can have a direct effect on patient care and lead to poor outcomes,” Dr. Jaynes said. “It’s a very dangerous phenomenon because it can degrade the quality of medical care provided.”

Most physicians are trained to internalize and compartmentalize these experiences, to “suck it up and get on with it,” he said, but it’s now become clear that such a strategy can have disastrous professional and personal consequences.

“In the worst case scenario, people burn out, drop out or commit suicide, their marriage ends up in shambles, or they turn to drugs and alcohol,” Dr. Jaynes said. “What Dr. Wu did was open the box to allow some empathy and compassion to be introduced to the situation.”

Dangers of unaddressed second victim impact

Estimates vary widely on the prevalence of second victim phenomenon among physicians and nurses who have been involved in a medical error or unexpected serious outcome. Across the medical field, estimates range from 10% in a study among otolaryngologists (Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116[7]:1114-20) to up to 30% and 50% more broadly, although some fields may be more susceptible than others (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36[5]:233-40; BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21[4]:267-70).

“In the world of obstetrics, we spend 99.9% of our time in a happy field of medicine filled with joy and new life,” Dr. Weiss said. “Whether consciously or unconsciously, those become the expectations of the patients and the providers, so when there is an outcome that is less than optimal, that’s when you’re even more affected because of what your expectations are going into it.”

Dr. Scott and her colleagues noted that the stages of being a second victim are similar to the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Stage 1: Chaos and event repair.

- Stage 2: Intrusive thoughts, “what if.”

- Stage 3: Restoring personal identity.

- Stage 4: Enduring the inquisition.

- Stage 5: Obtaining emotional first aid.

- Stage 6: Moving on or dropping out; surviving and/or thriving.”

“This can go on for years. Someone can spend years just surviving and not thriving,” Dr. Weiss said. “It can really happen along a continuum.”

Although studies have not looked specifically at second victims and patient care, research has shown that second victims have a higher risk of burnout, and that physicians with high burnout tend to order more tests, spend less time with patients, and have greater risk of making medical errors, Dr. Weiss said.

A study looking at the emotional impact of medical errors on physicians found that 61% had greater anxiety about making future medical errors, 44% had a loss of confidence, 42% had trouble sleeping, and 42% were less satisfied in their job (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

“You have the risk of the provider leaving medicine altogether or significantly changing their practice patterns, or giving up obstetric care because of the emotional toll it takes on providers,” she said. “We already know that one of the crises facing medicine right now is burnout, so you have the risk of additional or worsening burnout.”

Recognizing the need for formal support programs

Research does clearly show a need for programs formally addressing these experiences. A 2007 survey found that only 10% of 3,171 of internal medicine doctors, pediatricians, family physicians, and surgeons felt their health care organizations provided adequate support in managing stress following a medical error, yet about 8 in 10 wanted support (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33[8]:467-76).

Organizations are responding. One of the first second-victim programs is the “forYOU” program implemented at the University of Missouri Health Care’s Office of Clinical Effectiveness in 2007. The free, 24-7 program provides a “safe zone” for expressing emotions and reactions confidentially.

Ob Hospitalist Group just launched the CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery & Encouragement) Program, the first national peer-support program for second victims. The first 25 volunteers who underwent training in September will serve the organization’s more than 700 health care professionals across 32 states.

Instead of psychological counseling or intervention, the program emphasizes active listening, nonjudgment, and compassion during confidential calls; peers don’t take notes or record the conversations.

“We will be quiet and listen and speak at the appropriate times to be compassionate and not make judgments,” Dr. Jaynes said. “I think its critical to realize that in order to do that you have to be one of us. If you haven’t been there yourself when a baby dies in utero or you have a mother almost die by hemorrhage or a complication of surgery ... it creates emotional turmoil. Everybody who’s worth their salt questions, ‘What did I do wrong?’ and we’re really harsh on ourselves. If I can say I realize it’s a horrible place to be because I’ve been there myself, I can be a useful peer.”

At Dr. Weiss’s institution, Carilion Clinic spent 5 years developing and implementing the TRUST second-victim program, emphasizing Treatment, Respect, Understanding/compassion, Supportive care, and Transparency. Dr. Weiss said the first step in developing such a program is talking about the problem.

“You need hospital leadership addressing the phenomenon of the second victim, recognizing it is real, that it’s not a sign of weakness for providers to have any of these signs,” she said. “It has to be done at an organizational level. There has to be a place where providers can talk freely about the emotional impact of the outcome, not just the clinical outcomes.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore published findings in September 2017 about its program RISE (Resilience In Stressful Events) (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017 Sep;43[9]:471-83 that was featured by the Joint Commission as a program that employs some of the tools the commission describes in its toolkit for health care organizations to develop second-victim support programs (Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012 May;38[5]:235-40, 193).

It’s important that health care professionals are not expected or required to seek counseling or similar interventions, Dr. Weiss said, but they know of available resources.

“People need to be able to talk about it when they’re ready. It doesn’t necessarily matter how your peers judge your actions because these are feelings that come from within,” Dr. Weiss said, although colleagues can validate a second victim’s experience or feelings by sharing their own.

“It’s helpful when someone in a leadership role can acknowledge that this is real and say to a provider, ‘I’ve been there, and this is what helped me,’ or ‘I’ve been there, and there was no resource and I went without help for years,’ ” she said.

In fact, it’s her own past experiences that have made Dr. Weiss so passionate about raising awareness about second victims.

“I’ve been involved in cases of unanticipated outcomes and personally witnessed medical errors, and I’ve seen how very close colleagues can be affected,” she said. “This is a topic that really, really hits home for me.”

Signs and symptoms: How to recognize a possible second victim

Anyone can become a second victim, regardless of their training, experience, or years of practice, Dr. Weiss said. A health care professional may practice for years and witness many unanticipated poor outcomes before one suddenly drums up feelings they don’t expect.

“It’s almost inevitable that providers are going to have unanticipated outcomes or unexpected outcomes,” Dr. Weiss said. “The challenge with the second victim is no one can ever predict how someone is going to respond to an outcome, including ourselves. This may be the first time they have a response to something they never saw coming.”

Two aspects correlated with a higher risk of second victim are the severity of the morbidity or mortality of the patient and the degree of personal responsibility the health care professional feels. The signs and symptoms of being a second victim can be indistinguishable from those of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress syndrome, but the biggest indicator is a change in a person’s normal behavior, Dr. Weiss said.

“The person who is never late to work is late to work. The person who is always mild-mannered is on edge,” she said. “A lot of it is subtle personality or behavior changes, or you begin to notice practice pattern differences, such as ordering a bunch of labs.”

Perhaps the providers are snapping at people when they’ve never snapped before, or they express more cynicism or sarcasm, she added. “A change in their sleeping or eating patterns or in their personal hygiene are all things that one could look for.”

According to Dr. Jaynes, emotional signs may include irritability, fear, anger, grief, remorse, frustration, desperation, numbness, guilt, loneliness, shock and feeling disconnected, feeling hopeless or out of control. Physical symptoms include headaches, muscle tension, chest pain, extreme fatigue, sleeping problems, appetite changes or gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, frequent illnesses, being easily startled, or increased heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing rate. Other possible signs include flashbacks, nightmares, social avoidance, difficulties concentrating, poor memory, avoiding patient care areas, fearing repercussions to their reputations, and decreased job satisfaction. Second victims also may experience a loss in confidence or spiritual connection, or loss of interest in work, usual activities, and connections with others.

Dr. Weiss and Dr. Jaynes said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Climbing the therapeutic ladder in eczema-related itch

WASHINGTON – Currently available including antihistamines and an oral antiemetic approved for preventing chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, Peter Lio, MD, said at a symposium presented by the Coalition United for Better Eczema Care (CUBE-C).

There are four basic areas of treatment, which Dr. Lio, a dermatologist at Northwestern University, Chicago, referred to as the “itch therapeutic ladder.” In a video interview at the meeting, he reviewed the treatments, starting with topical therapies, which include camphor and menthol, strontium-containing topicals, as well as “dilute bleach-type products” that seem to have some anti-inflammatory and anti-itch effects.

The next levels: oral medications – antihistamines, followed by “more intense” options that may carry more risks, such as the antidepressant mirtazapine, and aprepitant, a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist approved for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Gabapentin and naltrexone can also be helpful for certain populations; all are used off-label, he pointed out.

Dr. Lio, formally trained in acupuncture, often uses alternative therapies as the fourth rung of the ladder. These include using a specific acupressure point, which he said “seems to give a little bit of relief.”

In the interview, he also discussed considerations in children with atopic dermatitis and exciting treatments in development, such as biologics that target “one of the master itch cytokines,” interleukin-31.

“Itch is such an important part of this disease because we know not only is it one of the key pieces that pushes the disease forward and keeps these cycles going, but also contributes a huge amount to the morbidity,” he said.

CUBE-C, established by the National Eczema Association (NEA), is a “network of cross-specialty leaders, patients and caregivers, constructing an educational curriculum based on standards of effective treatment and disease management,” according to the NEA.

The symposium was supported by an educational grant from Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. Dr. Lio reported serving as a speaker, consultant, and/or advisor for companies developing and marketing atopic dermatitis therapies and products.

WASHINGTON – Currently available including antihistamines and an oral antiemetic approved for preventing chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, Peter Lio, MD, said at a symposium presented by the Coalition United for Better Eczema Care (CUBE-C).

There are four basic areas of treatment, which Dr. Lio, a dermatologist at Northwestern University, Chicago, referred to as the “itch therapeutic ladder.” In a video interview at the meeting, he reviewed the treatments, starting with topical therapies, which include camphor and menthol, strontium-containing topicals, as well as “dilute bleach-type products” that seem to have some anti-inflammatory and anti-itch effects.

The next levels: oral medications – antihistamines, followed by “more intense” options that may carry more risks, such as the antidepressant mirtazapine, and aprepitant, a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist approved for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Gabapentin and naltrexone can also be helpful for certain populations; all are used off-label, he pointed out.

Dr. Lio, formally trained in acupuncture, often uses alternative therapies as the fourth rung of the ladder. These include using a specific acupressure point, which he said “seems to give a little bit of relief.”

In the interview, he also discussed considerations in children with atopic dermatitis and exciting treatments in development, such as biologics that target “one of the master itch cytokines,” interleukin-31.

“Itch is such an important part of this disease because we know not only is it one of the key pieces that pushes the disease forward and keeps these cycles going, but also contributes a huge amount to the morbidity,” he said.

CUBE-C, established by the National Eczema Association (NEA), is a “network of cross-specialty leaders, patients and caregivers, constructing an educational curriculum based on standards of effective treatment and disease management,” according to the NEA.