User login

Indeterminate Cell Histiocytosis and a Review of Current Treatment

Indeterminate Cell Histiocytosis and a Review of Current Treatment

To the Editor:

Indeterminate cell histiocytosis (ICH) is a rare neoplastic dendritic cell disorder with a poorly understood histogenesis and pathogenesis.1 The clinical manifestation of ICH is broad and can include isolated or multiple papules or nodules on the face, neck, trunk, arms, or legs. Our case demonstrates a rare occurrence of ICH that initially was misdiagnosed and highlights the use of cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor, as a potential new therapeutic option for ICH.

A 74-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented for evaluation of a progressive pruritic rash of approximately 5 years’ duration. The eruption previously had been diagnosed as Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It started on the chest and spread to the face, neck, trunk, and arms. The patient denied systemic symptoms and had no known history of malignancy.

Physical examination revealed pink to orange smooth papules, nodules, and small plaques on the ears, cheeks, trunk, neck, and arms (Figure 1). Baseline laboratory results showed a normal complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, elevated lactate dehydrogenase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and hyperlipidemia. Serology for hepatitis B and C was negative. Bone marrow biopsy was normal, and positron emission tomography/ computed tomography demonstrated no evidence of extracutaneous disease. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left forearm revealed epithelioid histiocytic proliferation in the dermis extending into the subcutis with a background infiltrate of small lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD1a and CD56 and was variably positive for CD4 but negative for CD163, CD68, S100, Langerin, cyclin D1, myeloperoxidase, CD21, and CD23. No mutation was detected in BRAF codon 600. Given the negative Langerin stain, these findings were compatible with a diagnosis of ICH. After considering the lack of standard treatment options as well as the recent approval of cobimetinib for histiocytic disorders, we initiated treatment with cobimetinib at the standard dose of 60 mg daily for 21 days followed by a 7-day break.

One month into treatment, the patient’s lesions were less erythematous, and he reported improvement in pruritus. Two months into treatment, there was continued improvement in cutaneous symptoms with flattening of the lesions on the chest and back. At this time, the patient developed edema of the face and ears (Figure 2) and reported weakness, blurred vision, and decreased appetite. He was advised to take an additional 7-day treatment break before resuming cobimetinib at a decreased dose of 40 mg daily. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later with improved systemic symptoms and continued flattening of the lesions. Five months into treatment, the lesions had continued to improve with complete resolution of the facial plaques (Figure 3).

Indeterminate cell histiocytosis is a rarely diagnosed condition characterized by the proliferation of indeterminate histiocytes that morphologically and immunophenotypically resemble Langerhans cells but lack their characteristic Birbeck granules.2 There is no standard treatment for ICH, but previous reports have described improvement with a variety of treatment options including methotrexate,3,4 UVB phototherapy,5 and topical delgocitinib 0.5%.6

Because histiocytic disorders are characterized by mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, it is possible that they would be responsive to MEK inhibition. Cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor initially approved to treat metastatic melanoma, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat histiocytic disorders in October 2022.7 The approval followed the release of data from a phase 2 trial of cobimetinib in 18 adults with various histiocytic disorders, which demonstrated an 89% (16/18) overall response rate with 94% (17/18) of patients remaining progression free at 1 year.8 While cobimetinib has not specifically been studied in ICH, given the high response rate in histiocytic disorders and the lack of standard treatment options for ICH, the decision was made to initiate treatment with cobimetinib in our patient. Based on the observed improvement in our patient, we propose cobimetinib as a treatment option for patients with cutaneous ICH and recommend additional studies to confirm its safety and efficacy in patients with this disorder.

- Bakry OA, Samaka RM, Kandil MA, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis with naïve cells. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:e13. doi:10.4081 /rt.2013.e13

- Manente L, Cotellessa C, Schmitt I, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis: a rare histiocytic disorder. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997; 19:276-283. doi:10.1097/00000372-199706000-00014

- Lie E, Jedrych J, Sweren R, et al. Generalized indeterminate cell histiocytosis successfully treated with methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;25:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.027

- Fournier J, Ingraffea A, Pedvis-Leftick A. Successful treatment of indeterminate cell histiocytosis with low-dose methotrexate. J Dermatol. 2011;38:937-939. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01148.x

- Logemann N, Thomas B, Yetto T. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis successfully treated with narrowband UVB. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20031. doi:10.5070/D31910020031

- Fujimoto RFT, Miura H, Takata M, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis treated with 0.5% delgocitinib ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:E39. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad029

- Diamond EL, Durham B, Dogan A, et al. Phase 2 trial of single-agent cobimetinib for adults with histiocytic neoplasms. Blood. 2023;142:1812. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-187508

- Diamond EL, Durham BH, Ulaner GA, et al. Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature. 2019;567:521-524. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1012-y

To the Editor:

Indeterminate cell histiocytosis (ICH) is a rare neoplastic dendritic cell disorder with a poorly understood histogenesis and pathogenesis.1 The clinical manifestation of ICH is broad and can include isolated or multiple papules or nodules on the face, neck, trunk, arms, or legs. Our case demonstrates a rare occurrence of ICH that initially was misdiagnosed and highlights the use of cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor, as a potential new therapeutic option for ICH.

A 74-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented for evaluation of a progressive pruritic rash of approximately 5 years’ duration. The eruption previously had been diagnosed as Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It started on the chest and spread to the face, neck, trunk, and arms. The patient denied systemic symptoms and had no known history of malignancy.

Physical examination revealed pink to orange smooth papules, nodules, and small plaques on the ears, cheeks, trunk, neck, and arms (Figure 1). Baseline laboratory results showed a normal complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, elevated lactate dehydrogenase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and hyperlipidemia. Serology for hepatitis B and C was negative. Bone marrow biopsy was normal, and positron emission tomography/ computed tomography demonstrated no evidence of extracutaneous disease. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left forearm revealed epithelioid histiocytic proliferation in the dermis extending into the subcutis with a background infiltrate of small lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD1a and CD56 and was variably positive for CD4 but negative for CD163, CD68, S100, Langerin, cyclin D1, myeloperoxidase, CD21, and CD23. No mutation was detected in BRAF codon 600. Given the negative Langerin stain, these findings were compatible with a diagnosis of ICH. After considering the lack of standard treatment options as well as the recent approval of cobimetinib for histiocytic disorders, we initiated treatment with cobimetinib at the standard dose of 60 mg daily for 21 days followed by a 7-day break.

One month into treatment, the patient’s lesions were less erythematous, and he reported improvement in pruritus. Two months into treatment, there was continued improvement in cutaneous symptoms with flattening of the lesions on the chest and back. At this time, the patient developed edema of the face and ears (Figure 2) and reported weakness, blurred vision, and decreased appetite. He was advised to take an additional 7-day treatment break before resuming cobimetinib at a decreased dose of 40 mg daily. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later with improved systemic symptoms and continued flattening of the lesions. Five months into treatment, the lesions had continued to improve with complete resolution of the facial plaques (Figure 3).

Indeterminate cell histiocytosis is a rarely diagnosed condition characterized by the proliferation of indeterminate histiocytes that morphologically and immunophenotypically resemble Langerhans cells but lack their characteristic Birbeck granules.2 There is no standard treatment for ICH, but previous reports have described improvement with a variety of treatment options including methotrexate,3,4 UVB phototherapy,5 and topical delgocitinib 0.5%.6

Because histiocytic disorders are characterized by mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, it is possible that they would be responsive to MEK inhibition. Cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor initially approved to treat metastatic melanoma, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat histiocytic disorders in October 2022.7 The approval followed the release of data from a phase 2 trial of cobimetinib in 18 adults with various histiocytic disorders, which demonstrated an 89% (16/18) overall response rate with 94% (17/18) of patients remaining progression free at 1 year.8 While cobimetinib has not specifically been studied in ICH, given the high response rate in histiocytic disorders and the lack of standard treatment options for ICH, the decision was made to initiate treatment with cobimetinib in our patient. Based on the observed improvement in our patient, we propose cobimetinib as a treatment option for patients with cutaneous ICH and recommend additional studies to confirm its safety and efficacy in patients with this disorder.

To the Editor:

Indeterminate cell histiocytosis (ICH) is a rare neoplastic dendritic cell disorder with a poorly understood histogenesis and pathogenesis.1 The clinical manifestation of ICH is broad and can include isolated or multiple papules or nodules on the face, neck, trunk, arms, or legs. Our case demonstrates a rare occurrence of ICH that initially was misdiagnosed and highlights the use of cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor, as a potential new therapeutic option for ICH.

A 74-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented for evaluation of a progressive pruritic rash of approximately 5 years’ duration. The eruption previously had been diagnosed as Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It started on the chest and spread to the face, neck, trunk, and arms. The patient denied systemic symptoms and had no known history of malignancy.

Physical examination revealed pink to orange smooth papules, nodules, and small plaques on the ears, cheeks, trunk, neck, and arms (Figure 1). Baseline laboratory results showed a normal complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, elevated lactate dehydrogenase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and hyperlipidemia. Serology for hepatitis B and C was negative. Bone marrow biopsy was normal, and positron emission tomography/ computed tomography demonstrated no evidence of extracutaneous disease. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left forearm revealed epithelioid histiocytic proliferation in the dermis extending into the subcutis with a background infiltrate of small lymphocytes. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD1a and CD56 and was variably positive for CD4 but negative for CD163, CD68, S100, Langerin, cyclin D1, myeloperoxidase, CD21, and CD23. No mutation was detected in BRAF codon 600. Given the negative Langerin stain, these findings were compatible with a diagnosis of ICH. After considering the lack of standard treatment options as well as the recent approval of cobimetinib for histiocytic disorders, we initiated treatment with cobimetinib at the standard dose of 60 mg daily for 21 days followed by a 7-day break.

One month into treatment, the patient’s lesions were less erythematous, and he reported improvement in pruritus. Two months into treatment, there was continued improvement in cutaneous symptoms with flattening of the lesions on the chest and back. At this time, the patient developed edema of the face and ears (Figure 2) and reported weakness, blurred vision, and decreased appetite. He was advised to take an additional 7-day treatment break before resuming cobimetinib at a decreased dose of 40 mg daily. The patient returned to the clinic 1 month later with improved systemic symptoms and continued flattening of the lesions. Five months into treatment, the lesions had continued to improve with complete resolution of the facial plaques (Figure 3).

Indeterminate cell histiocytosis is a rarely diagnosed condition characterized by the proliferation of indeterminate histiocytes that morphologically and immunophenotypically resemble Langerhans cells but lack their characteristic Birbeck granules.2 There is no standard treatment for ICH, but previous reports have described improvement with a variety of treatment options including methotrexate,3,4 UVB phototherapy,5 and topical delgocitinib 0.5%.6

Because histiocytic disorders are characterized by mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, it is possible that they would be responsive to MEK inhibition. Cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor initially approved to treat metastatic melanoma, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat histiocytic disorders in October 2022.7 The approval followed the release of data from a phase 2 trial of cobimetinib in 18 adults with various histiocytic disorders, which demonstrated an 89% (16/18) overall response rate with 94% (17/18) of patients remaining progression free at 1 year.8 While cobimetinib has not specifically been studied in ICH, given the high response rate in histiocytic disorders and the lack of standard treatment options for ICH, the decision was made to initiate treatment with cobimetinib in our patient. Based on the observed improvement in our patient, we propose cobimetinib as a treatment option for patients with cutaneous ICH and recommend additional studies to confirm its safety and efficacy in patients with this disorder.

- Bakry OA, Samaka RM, Kandil MA, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis with naïve cells. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:e13. doi:10.4081 /rt.2013.e13

- Manente L, Cotellessa C, Schmitt I, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis: a rare histiocytic disorder. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997; 19:276-283. doi:10.1097/00000372-199706000-00014

- Lie E, Jedrych J, Sweren R, et al. Generalized indeterminate cell histiocytosis successfully treated with methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;25:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.027

- Fournier J, Ingraffea A, Pedvis-Leftick A. Successful treatment of indeterminate cell histiocytosis with low-dose methotrexate. J Dermatol. 2011;38:937-939. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01148.x

- Logemann N, Thomas B, Yetto T. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis successfully treated with narrowband UVB. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20031. doi:10.5070/D31910020031

- Fujimoto RFT, Miura H, Takata M, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis treated with 0.5% delgocitinib ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:E39. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad029

- Diamond EL, Durham B, Dogan A, et al. Phase 2 trial of single-agent cobimetinib for adults with histiocytic neoplasms. Blood. 2023;142:1812. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-187508

- Diamond EL, Durham BH, Ulaner GA, et al. Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature. 2019;567:521-524. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1012-y

- Bakry OA, Samaka RM, Kandil MA, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis with naïve cells. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:e13. doi:10.4081 /rt.2013.e13

- Manente L, Cotellessa C, Schmitt I, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis: a rare histiocytic disorder. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997; 19:276-283. doi:10.1097/00000372-199706000-00014

- Lie E, Jedrych J, Sweren R, et al. Generalized indeterminate cell histiocytosis successfully treated with methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;25:93-96. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.027

- Fournier J, Ingraffea A, Pedvis-Leftick A. Successful treatment of indeterminate cell histiocytosis with low-dose methotrexate. J Dermatol. 2011;38:937-939. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01148.x

- Logemann N, Thomas B, Yetto T. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis successfully treated with narrowband UVB. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:20031. doi:10.5070/D31910020031

- Fujimoto RFT, Miura H, Takata M, et al. Indeterminate cell histiocytosis treated with 0.5% delgocitinib ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:E39. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad029

- Diamond EL, Durham B, Dogan A, et al. Phase 2 trial of single-agent cobimetinib for adults with histiocytic neoplasms. Blood. 2023;142:1812. doi:10.1182/blood-2023-187508

- Diamond EL, Durham BH, Ulaner GA, et al. Efficacy of MEK inhibition in patients with histiocytic neoplasms. Nature. 2019;567:521-524. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1012-y

Indeterminate Cell Histiocytosis and a Review of Current Treatment

Indeterminate Cell Histiocytosis and a Review of Current Treatment

PRACTICE POINTS

- Indeterminate cell histiocytosis (ICH) is a rare neoplastic dendritic cell disorder that can manifest as isolated or multiple papules or nodules on the face, neck, trunk, arms, or legs.

- Although there is no standard treatment for ICH, histiocytic disorders are characterized by mutations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and may be responsive to MEK inhibition.

- Cobimetinib, a MEK inhibitor initially approved to treat metastatic melanoma, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat histiocytic disorders in October 2022.

Tetrad Bodies in Skin

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

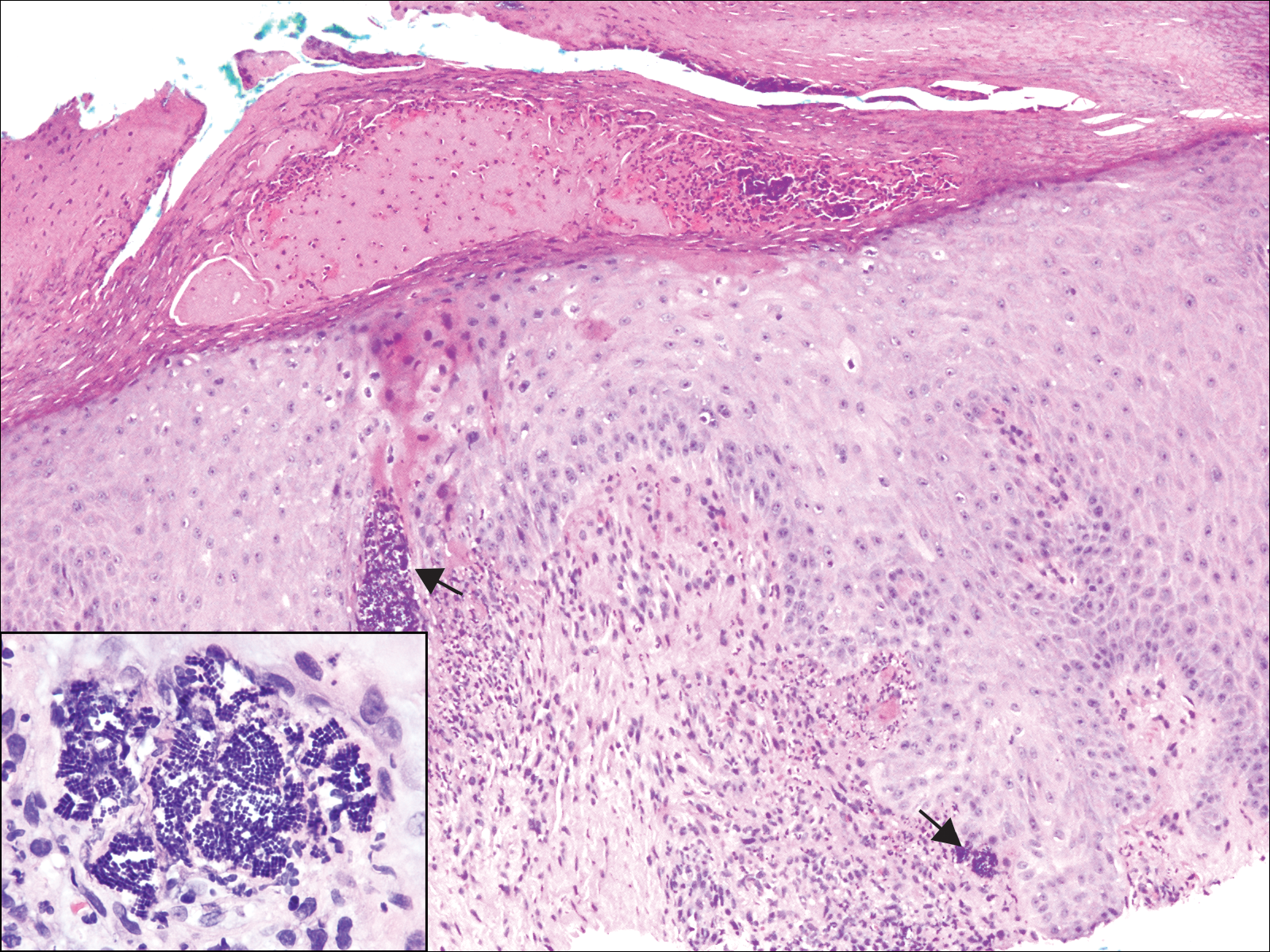

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1 Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3 Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7 Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

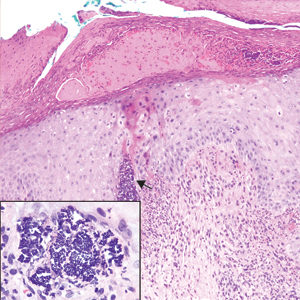

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

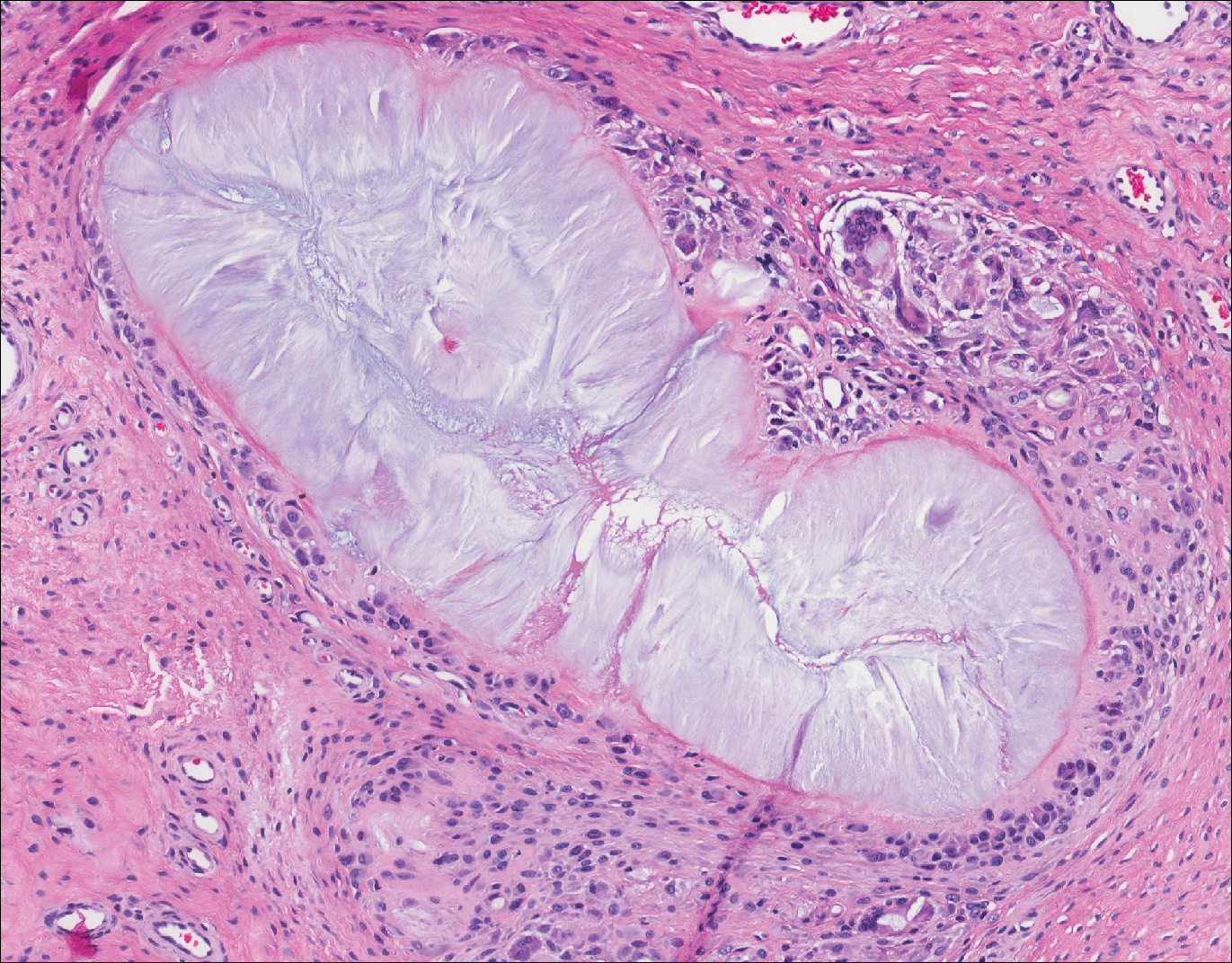

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14 Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13 Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1 Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3 Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7 Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

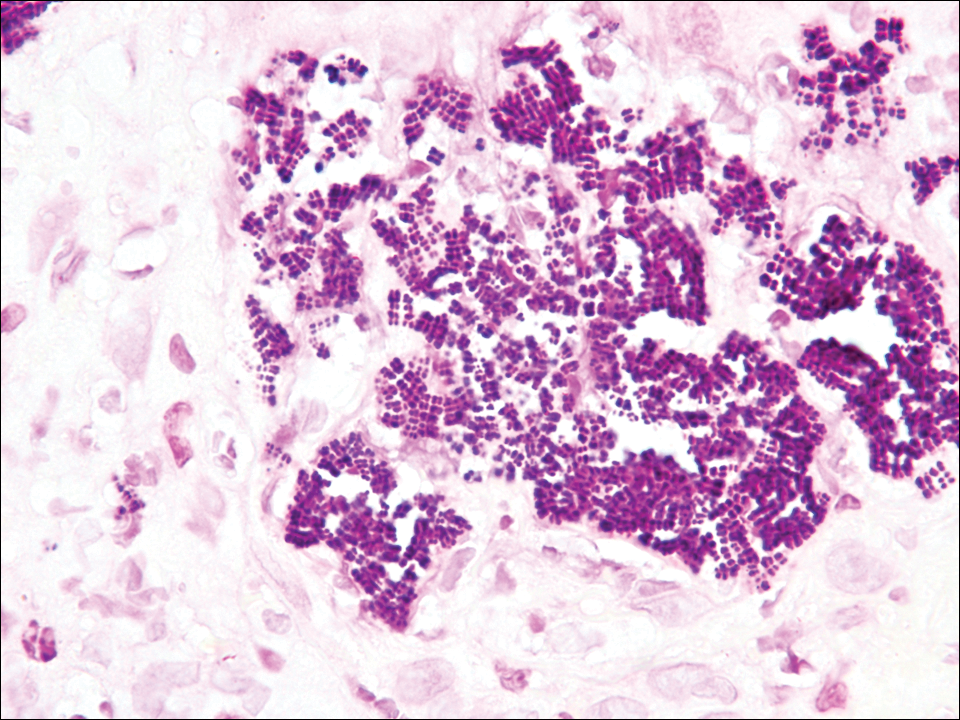

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

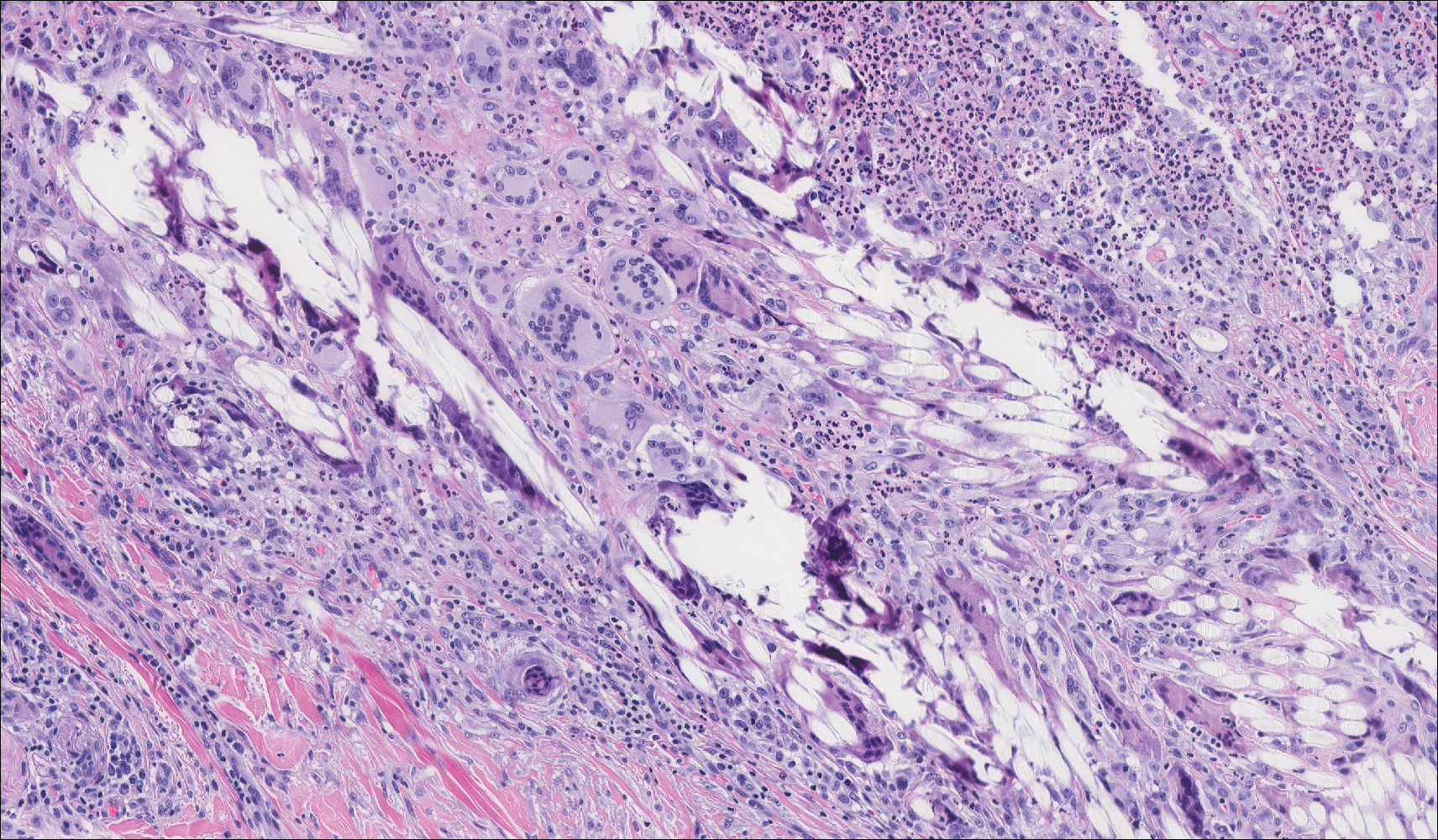

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

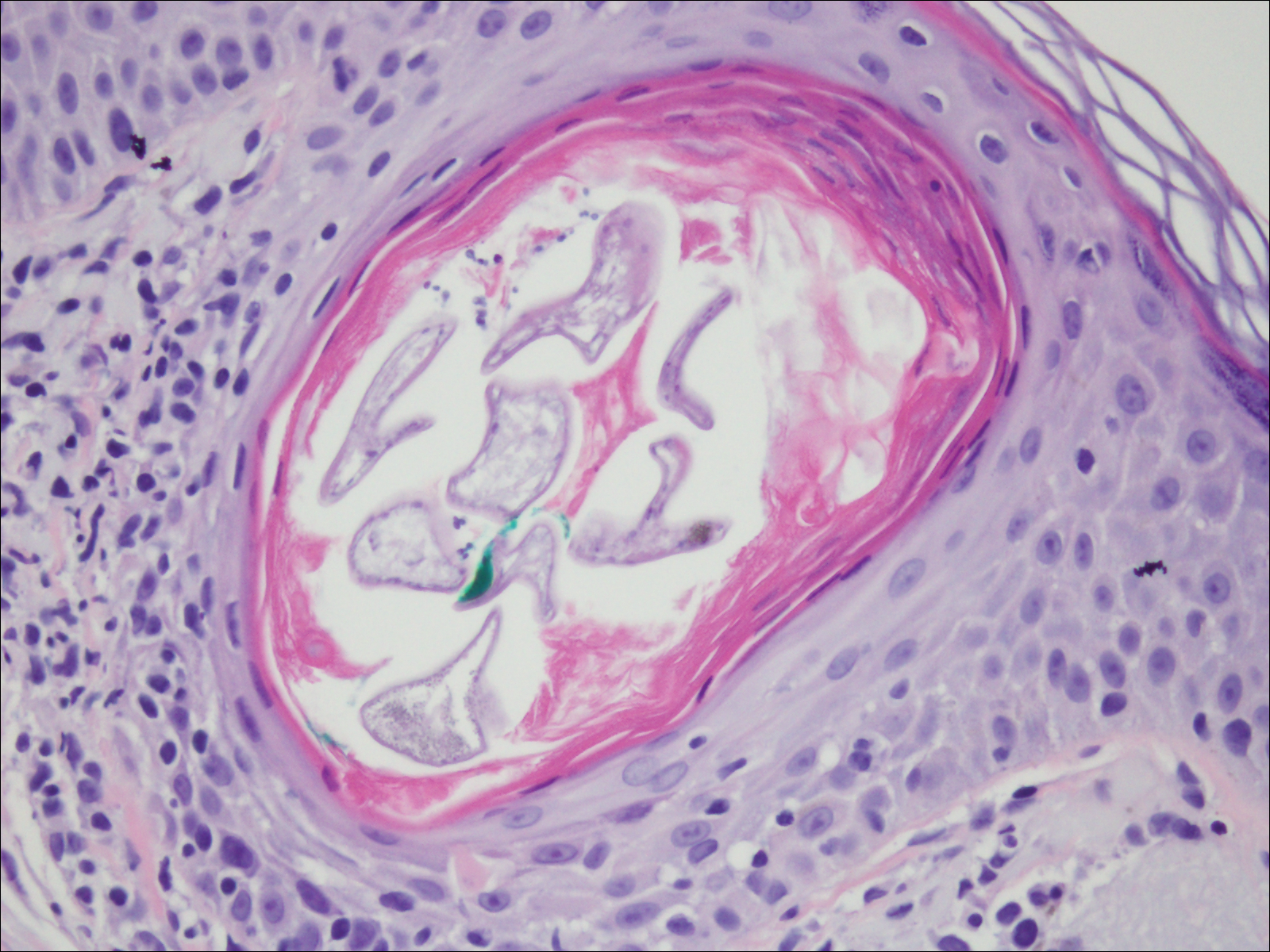

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14 Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13 Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1 Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3 Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7 Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14 Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13 Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

A 72-year-old woman with a medical history notable for multiple sclerosis and intravenous drug abuse presented to the dermatology clinic with a 0.6×0.5-cm, pruritic, wartlike, inflamed, keratotic papule on the palmar aspect of the right finger of more than 1 month's duration. A shave biopsy was performed that showed excoriation with serum crust, parakeratosis, and neutrophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis. Within the serum crust and at the dermoepidermal junction, clusters of refractive basophilic bodies (arrows) in tetrad arrangement also were noted (inset). The papule resolved after the biopsy without any additional treatment.