User login

Sweet Syndrome Presenting With an Unusual Morphology

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that typically presents as an acute onset of multiple, painful, sharply demarcated, small (measuring a few centimeters), raised, red plaques that occasionally present with superimposed pustules, vesicles, or bullae on the face, neck, upper chest, back, and extremities. Patients are often febrile and may have mucosal and systemic involvement.1 Although 71% of cases are idiopathic, others are associated with malignancy; autoimmune disorders; infections; pregnancy; and rarely medications, especially all-trans-retinoic acid, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, vaccines, and antibiotics.1,2 We present a case of Sweet syndrome induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with an unusual clinical presentation.

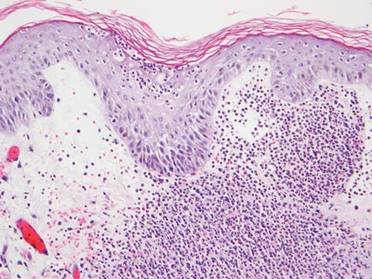

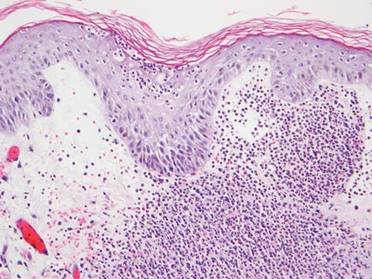

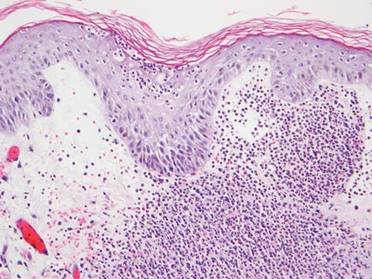

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of nonmelanoma skin cancer initiated a course of TMP-SMX for a wound infection of the lower leg following Mohs micrographic surgery. Eight days later, he developed a painful eruption preceded by 1 day of fever, malaise, blurry vision, and myalgia. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was discontinued. Physical examination revealed ill-defined, discrete and coalescing, 1- to 6-mm edematous erythematous papules studded with pustules involving the scalp, face, neck, back (Figure 1), and extremities. The patient also had conjunctival erythema and an elevated temperature (38.3°C). Laboratory workup revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,300/mL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), blood urea nitrogen level (33 mg/µL [reference range, 7–20 mg/dL]), and creatinine level (2.00 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Liver function tests were normal. A biopsy demonstrated marked papillary dermal edema with a dense, bandlike, superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 2). A few neutrophils were present in the epidermis with formation of minute intraepidermal pustules. The patient was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg 3 times daily (1.5 mg/kg body weight) tapered over 17 days and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily. His fever and leukocytosis resolved within 1 day and the eruption improved within 2 days with residual desquamation that cleared by 3 weeks.

|

|

Morphologically, our case resembled acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which presents with edematous erythema studded with pustules.3 Although fever and leukocytosis are often present in both AGEP and Sweet syndrome, our patient’s pain, malaise, and myalgia favored Sweet syndrome, as did his conjunctivitis, which is unusual in AGEP.1,3 Histologically, our case was characteristic for Sweet syndrome, which presents with marked papillary dermal edema and a dense neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with neutrophil exocytosis and spongiform pustules in 21% of cases.1 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, characterized by spongiform pustules and a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, does not exhibit the dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate of Sweet syndrome.3 Mecca et al4 also reported a case displaying overlapping features of Sweet syndrome and AGEP. The patient presented with photodistributed papules and pinpoint pustules on an erythematous base favoring a diagnosis of AGEP with histologic findings compatible with Sweet syndrome. The authors suggested a clinicopathologic continuum may exist among drug-related neutrophilic dermatoses.4

In conclusion, we present a case of TMP-SMX–induced Sweet syndrome that morphologically resembled AGEP. It is important to recognize that Sweet syndrome may present in this unusual manner, as it may have notable internal involvement, and responds rapidly to systemic steroids, whereas AGEP has minimal systemic involvement and clears spontaneously.

1. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Kluger N, Marque M, Stoebner PE, et al. Possible drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:637-638.

3. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

4. Mecca P, Tobin E, Andrew Carlson J. Photo-distributed neutrophilic drug eruption and adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with antidepressant therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:189-194.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that typically presents as an acute onset of multiple, painful, sharply demarcated, small (measuring a few centimeters), raised, red plaques that occasionally present with superimposed pustules, vesicles, or bullae on the face, neck, upper chest, back, and extremities. Patients are often febrile and may have mucosal and systemic involvement.1 Although 71% of cases are idiopathic, others are associated with malignancy; autoimmune disorders; infections; pregnancy; and rarely medications, especially all-trans-retinoic acid, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, vaccines, and antibiotics.1,2 We present a case of Sweet syndrome induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with an unusual clinical presentation.

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of nonmelanoma skin cancer initiated a course of TMP-SMX for a wound infection of the lower leg following Mohs micrographic surgery. Eight days later, he developed a painful eruption preceded by 1 day of fever, malaise, blurry vision, and myalgia. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was discontinued. Physical examination revealed ill-defined, discrete and coalescing, 1- to 6-mm edematous erythematous papules studded with pustules involving the scalp, face, neck, back (Figure 1), and extremities. The patient also had conjunctival erythema and an elevated temperature (38.3°C). Laboratory workup revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,300/mL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), blood urea nitrogen level (33 mg/µL [reference range, 7–20 mg/dL]), and creatinine level (2.00 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Liver function tests were normal. A biopsy demonstrated marked papillary dermal edema with a dense, bandlike, superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 2). A few neutrophils were present in the epidermis with formation of minute intraepidermal pustules. The patient was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg 3 times daily (1.5 mg/kg body weight) tapered over 17 days and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily. His fever and leukocytosis resolved within 1 day and the eruption improved within 2 days with residual desquamation that cleared by 3 weeks.

|

|

Morphologically, our case resembled acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which presents with edematous erythema studded with pustules.3 Although fever and leukocytosis are often present in both AGEP and Sweet syndrome, our patient’s pain, malaise, and myalgia favored Sweet syndrome, as did his conjunctivitis, which is unusual in AGEP.1,3 Histologically, our case was characteristic for Sweet syndrome, which presents with marked papillary dermal edema and a dense neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with neutrophil exocytosis and spongiform pustules in 21% of cases.1 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, characterized by spongiform pustules and a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, does not exhibit the dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate of Sweet syndrome.3 Mecca et al4 also reported a case displaying overlapping features of Sweet syndrome and AGEP. The patient presented with photodistributed papules and pinpoint pustules on an erythematous base favoring a diagnosis of AGEP with histologic findings compatible with Sweet syndrome. The authors suggested a clinicopathologic continuum may exist among drug-related neutrophilic dermatoses.4

In conclusion, we present a case of TMP-SMX–induced Sweet syndrome that morphologically resembled AGEP. It is important to recognize that Sweet syndrome may present in this unusual manner, as it may have notable internal involvement, and responds rapidly to systemic steroids, whereas AGEP has minimal systemic involvement and clears spontaneously.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that typically presents as an acute onset of multiple, painful, sharply demarcated, small (measuring a few centimeters), raised, red plaques that occasionally present with superimposed pustules, vesicles, or bullae on the face, neck, upper chest, back, and extremities. Patients are often febrile and may have mucosal and systemic involvement.1 Although 71% of cases are idiopathic, others are associated with malignancy; autoimmune disorders; infections; pregnancy; and rarely medications, especially all-trans-retinoic acid, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, vaccines, and antibiotics.1,2 We present a case of Sweet syndrome induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with an unusual clinical presentation.

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of nonmelanoma skin cancer initiated a course of TMP-SMX for a wound infection of the lower leg following Mohs micrographic surgery. Eight days later, he developed a painful eruption preceded by 1 day of fever, malaise, blurry vision, and myalgia. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was discontinued. Physical examination revealed ill-defined, discrete and coalescing, 1- to 6-mm edematous erythematous papules studded with pustules involving the scalp, face, neck, back (Figure 1), and extremities. The patient also had conjunctival erythema and an elevated temperature (38.3°C). Laboratory workup revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,300/mL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), blood urea nitrogen level (33 mg/µL [reference range, 7–20 mg/dL]), and creatinine level (2.00 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Liver function tests were normal. A biopsy demonstrated marked papillary dermal edema with a dense, bandlike, superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 2). A few neutrophils were present in the epidermis with formation of minute intraepidermal pustules. The patient was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg 3 times daily (1.5 mg/kg body weight) tapered over 17 days and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily. His fever and leukocytosis resolved within 1 day and the eruption improved within 2 days with residual desquamation that cleared by 3 weeks.

|

|

Morphologically, our case resembled acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which presents with edematous erythema studded with pustules.3 Although fever and leukocytosis are often present in both AGEP and Sweet syndrome, our patient’s pain, malaise, and myalgia favored Sweet syndrome, as did his conjunctivitis, which is unusual in AGEP.1,3 Histologically, our case was characteristic for Sweet syndrome, which presents with marked papillary dermal edema and a dense neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with neutrophil exocytosis and spongiform pustules in 21% of cases.1 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, characterized by spongiform pustules and a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, does not exhibit the dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate of Sweet syndrome.3 Mecca et al4 also reported a case displaying overlapping features of Sweet syndrome and AGEP. The patient presented with photodistributed papules and pinpoint pustules on an erythematous base favoring a diagnosis of AGEP with histologic findings compatible with Sweet syndrome. The authors suggested a clinicopathologic continuum may exist among drug-related neutrophilic dermatoses.4

In conclusion, we present a case of TMP-SMX–induced Sweet syndrome that morphologically resembled AGEP. It is important to recognize that Sweet syndrome may present in this unusual manner, as it may have notable internal involvement, and responds rapidly to systemic steroids, whereas AGEP has minimal systemic involvement and clears spontaneously.

1. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Kluger N, Marque M, Stoebner PE, et al. Possible drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:637-638.

3. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

4. Mecca P, Tobin E, Andrew Carlson J. Photo-distributed neutrophilic drug eruption and adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with antidepressant therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:189-194.

1. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Kluger N, Marque M, Stoebner PE, et al. Possible drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:637-638.

3. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

4. Mecca P, Tobin E, Andrew Carlson J. Photo-distributed neutrophilic drug eruption and adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with antidepressant therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:189-194.

Multiple Firm Pink Papules and Nodules

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

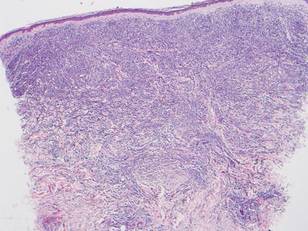

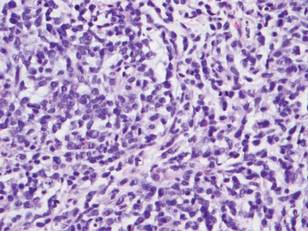

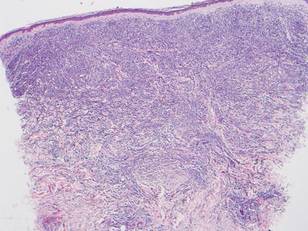

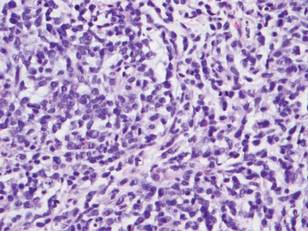

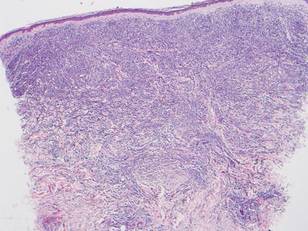

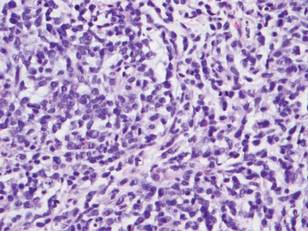

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

A 91-year-old man presented with numerous, scattered, asymptomatic, 3- to 9-mm, smooth, firm, pink papules and nodules involving the neck, trunk, and arms and legs of 1 week’s duration.