User login

Erythematous and Necrotic Papules in an Immunosuppressed Woman

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Fusariosis

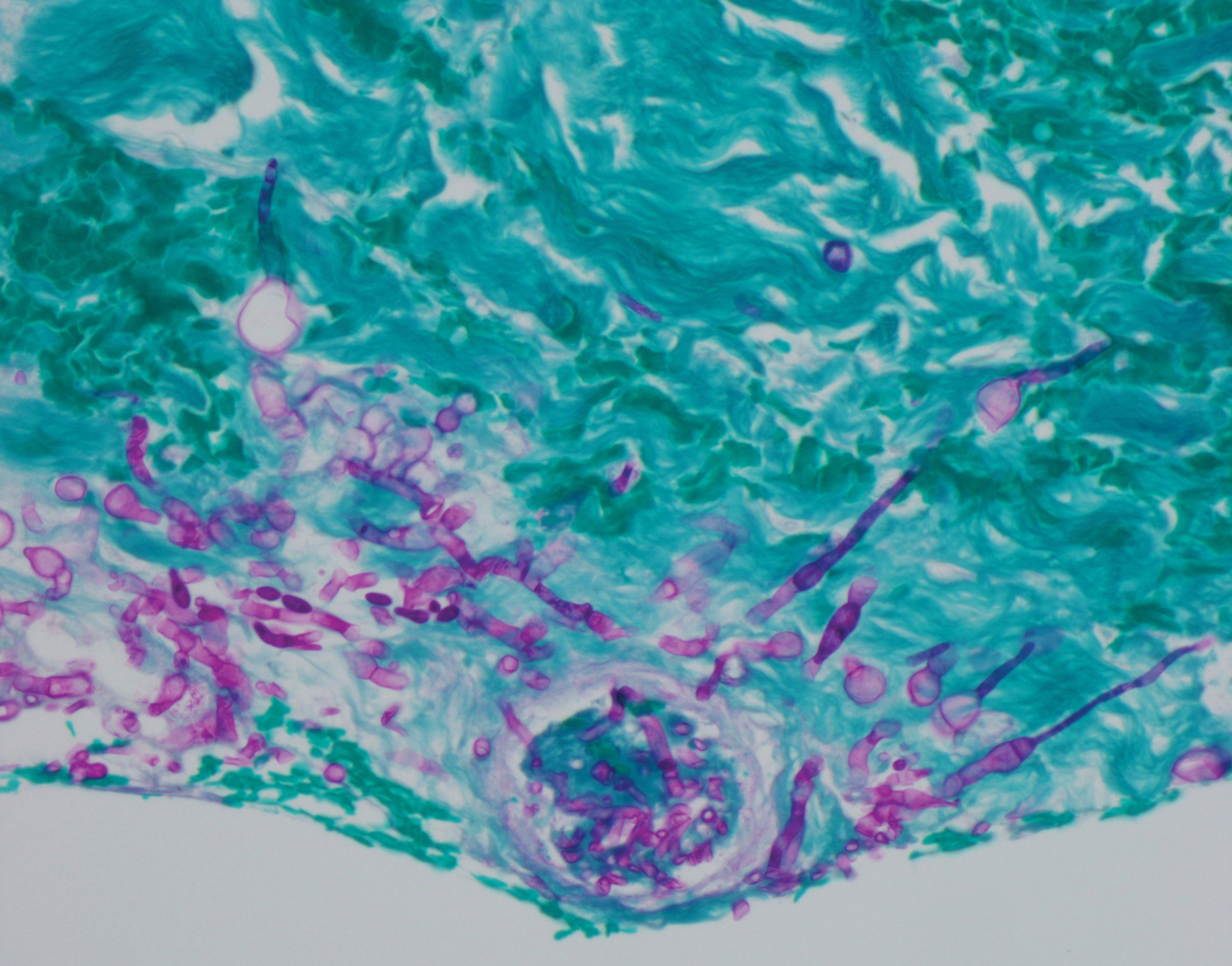

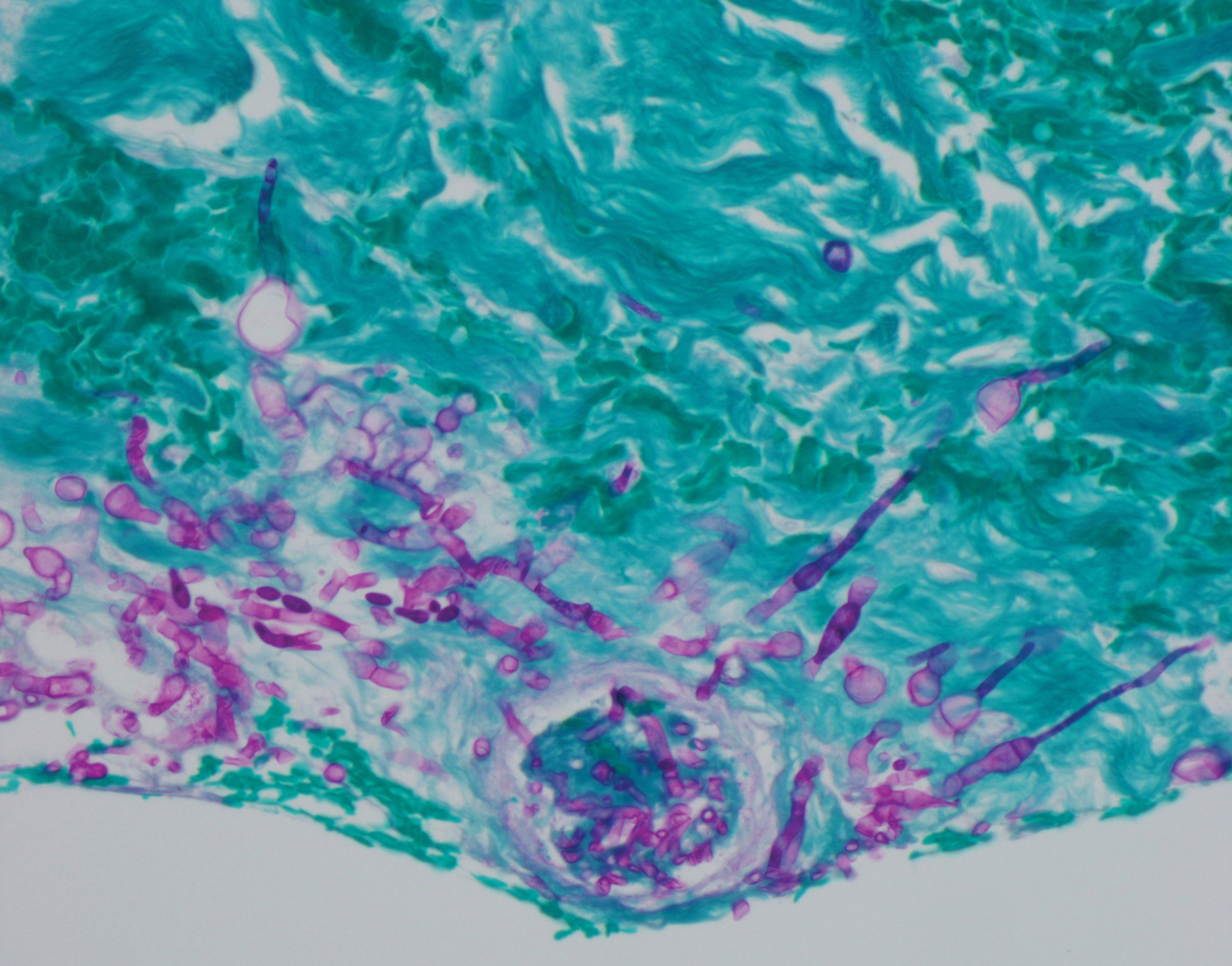

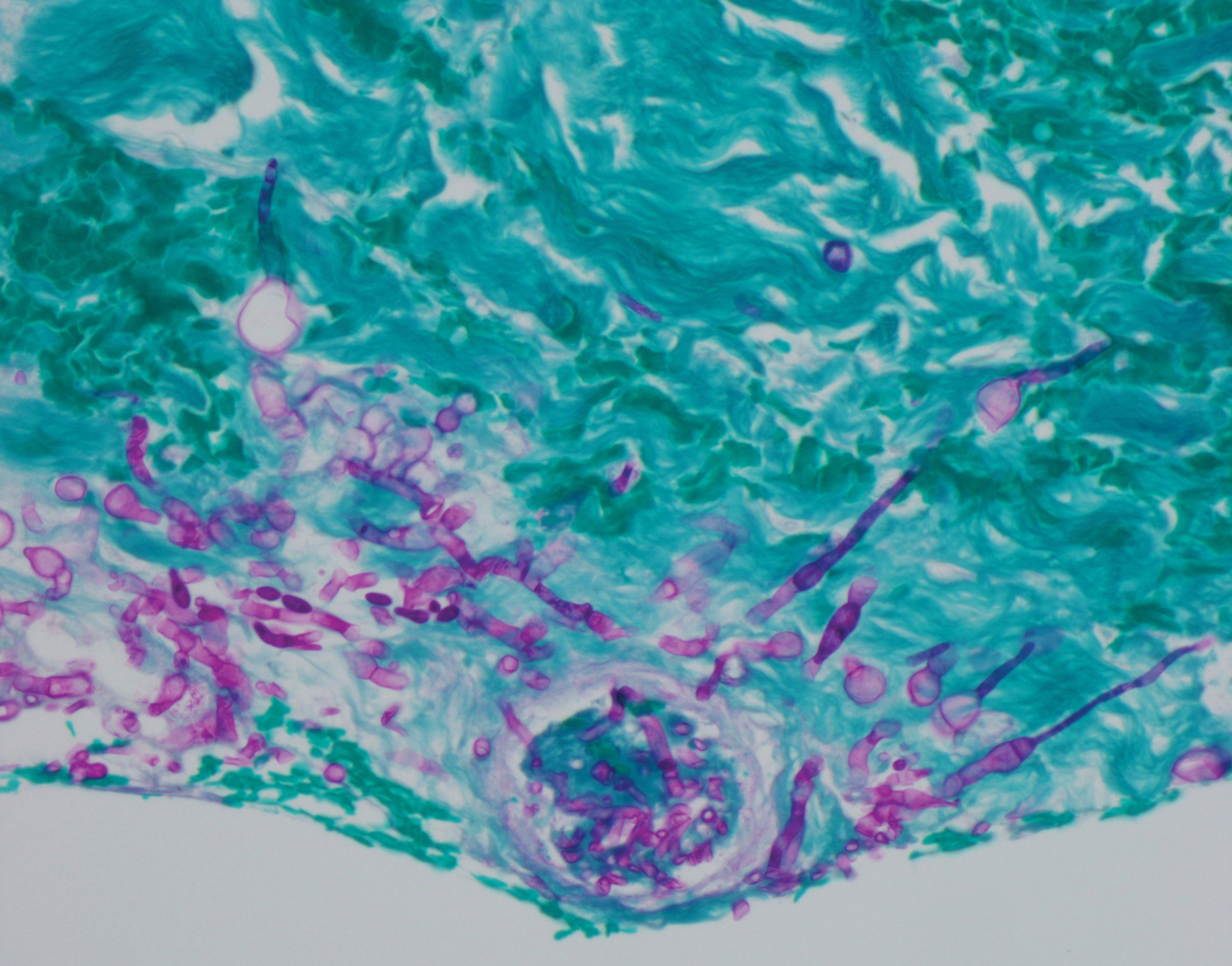

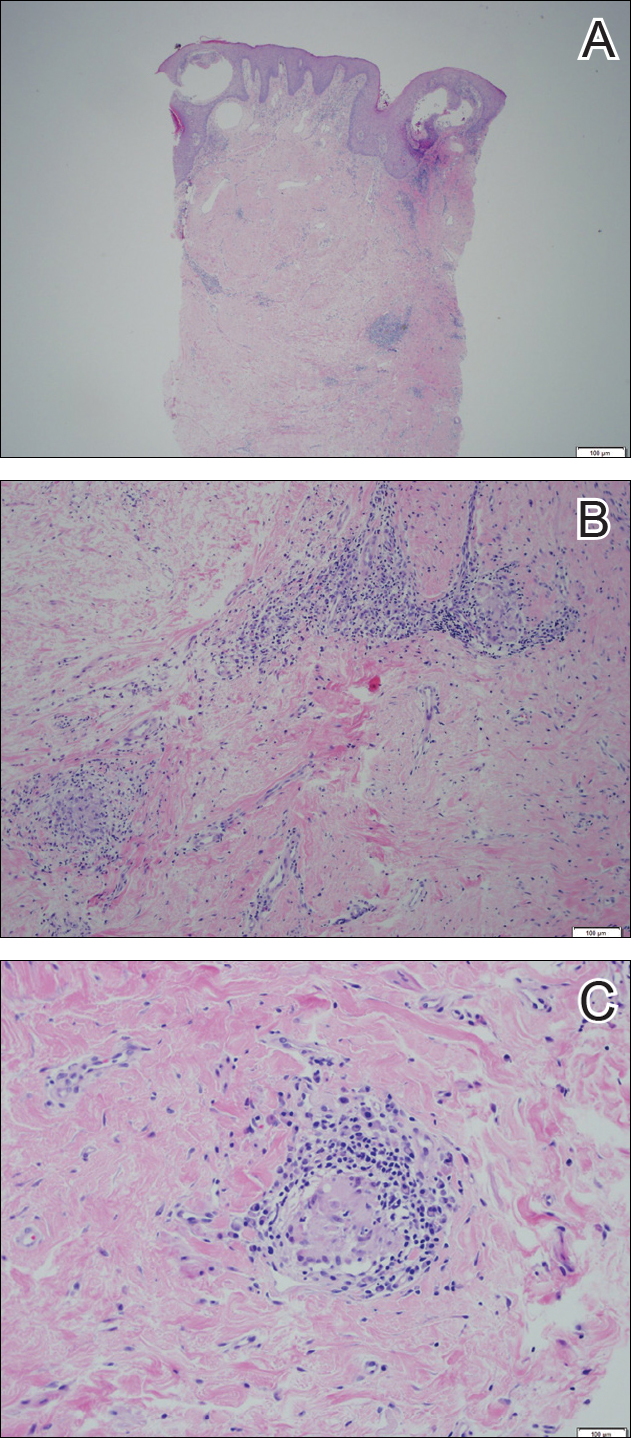

Histologic evaluation of the punch biopsy demonstrated thrombosed vessels in the deep dermis and along fibrous septae of subcutaneous tissue, as well as delicate, thin-walled, branching hyphae with vesicular swellings (Figure). The hyphae were present within the vascular thrombi and extended into surrounding tissue. The fungal tissue culture eventually grew scant Fusarium. At the time of biopsy, there was a high index of suspicion for fungal infection, which supported the decision to empirically treat with anidulafungin and voriconazole.

Differentiating the diagnosis in this case was done primarily with histopathology. Although Aspergillus also has slender hyphae, it lacks the vesicular swellings characteristic of fusariosis. Disseminated candidiasis would demonstrate budding yeast and pseudohyphae in the dermis. Ecthyma gangrenosum histologically presents as necrotizing hemorrhagic vasculitis with gram-negative rods in the walls of deeper vessels, characteristically sparing the intima. Leukemia cutis histologically varies but would display a neoplastic infiltrate of atypical monocytoid cells with nuclear pleomorphism.

Our patient had been treated with palliative chemotherapy as a salvage regimen with idarubicin and cytarabine. She had persistent pancytopenia despite granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor therapy. The mortality rate for disseminated Fusarium infection approaches 100% when risk factors such as angiotropism and prolonged neutropenia are present.1,2 Additionally, our patient's susceptibility profile subsequently demonstrated an elevated minimum inhibitory concentration to amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole. The neutropenia and Fusarium infection were not responsive to treatment. She was discharged on palliative voriconazole with home hospice care.

Fusarium species are soil-dwelling saprophytes and important plant pathogens that have increasingly emerged as rare but notable causes of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients.1-3 More specifically, Fusarium infection is most commonly observed in patients with hematologic malignancy complicated by persistent neutropenia. The 3 most frequently encountered Fusarium species in human disease are Fusarium solani, Fusarium oxysporum, and Fusarium moniliforme, with F solani being the most virulent.1,2 Infection with Fusarium may manifest as a broad range of presentations depending on the route of entry, such as endophthalmitis, sinusitis, pneumonia, and cutaneous lesions.1 Disseminated infection is marked by skin lesions or positive blood cultures for Fusarium.3 This fungus is notorious for its limited susceptibility profile.1 It requires systemic antifungal medications such as triazoles and amphotericin B. Fusarium is most susceptible in vitro to amphotericin B but often requires toxic dosages to be effective in decreasing fungal load.2,3 The high mortality rate of disseminated fusariosis further emphasizes that prevention is an important component to protecting high-risk patients. Keeping patients in rooms with high-efficiency particulate arresting filters and limiting exposure to unsanitized tap water faucets can help decrease exposure; however, reducing immunosuppression and improving neutropenia are the most effective ways to prevent fusariosis.1 Although skin breakdown can facilitate the spread of infection, it has been observed that immunosuppressed individuals do not necessarily have this finding.4

This case emphasizes the importance of considering disseminated fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancy or other immunosuppressed conditions. The most important factors that should raise clinical suspicion are persistent neutropenia and recent corticosteroid therapy.1 A clinical picture that suggests fungal infection should warrant consideration of prophylactic treatment as well as tissue and blood cultures to determine species and susceptibility.

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:695-704.

- Jossi M, Ambrosioni J, Macedo-Vinas M, et al. Invasive fusariosis with prolonged fungemia in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E354-E356.

- Tan R, Ng KP, Gan GG, et al. Fusarium sp. infection in a patient with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68:479-480.

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:909-920.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Fusariosis

Histologic evaluation of the punch biopsy demonstrated thrombosed vessels in the deep dermis and along fibrous septae of subcutaneous tissue, as well as delicate, thin-walled, branching hyphae with vesicular swellings (Figure). The hyphae were present within the vascular thrombi and extended into surrounding tissue. The fungal tissue culture eventually grew scant Fusarium. At the time of biopsy, there was a high index of suspicion for fungal infection, which supported the decision to empirically treat with anidulafungin and voriconazole.

Differentiating the diagnosis in this case was done primarily with histopathology. Although Aspergillus also has slender hyphae, it lacks the vesicular swellings characteristic of fusariosis. Disseminated candidiasis would demonstrate budding yeast and pseudohyphae in the dermis. Ecthyma gangrenosum histologically presents as necrotizing hemorrhagic vasculitis with gram-negative rods in the walls of deeper vessels, characteristically sparing the intima. Leukemia cutis histologically varies but would display a neoplastic infiltrate of atypical monocytoid cells with nuclear pleomorphism.

Our patient had been treated with palliative chemotherapy as a salvage regimen with idarubicin and cytarabine. She had persistent pancytopenia despite granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor therapy. The mortality rate for disseminated Fusarium infection approaches 100% when risk factors such as angiotropism and prolonged neutropenia are present.1,2 Additionally, our patient's susceptibility profile subsequently demonstrated an elevated minimum inhibitory concentration to amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole. The neutropenia and Fusarium infection were not responsive to treatment. She was discharged on palliative voriconazole with home hospice care.

Fusarium species are soil-dwelling saprophytes and important plant pathogens that have increasingly emerged as rare but notable causes of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients.1-3 More specifically, Fusarium infection is most commonly observed in patients with hematologic malignancy complicated by persistent neutropenia. The 3 most frequently encountered Fusarium species in human disease are Fusarium solani, Fusarium oxysporum, and Fusarium moniliforme, with F solani being the most virulent.1,2 Infection with Fusarium may manifest as a broad range of presentations depending on the route of entry, such as endophthalmitis, sinusitis, pneumonia, and cutaneous lesions.1 Disseminated infection is marked by skin lesions or positive blood cultures for Fusarium.3 This fungus is notorious for its limited susceptibility profile.1 It requires systemic antifungal medications such as triazoles and amphotericin B. Fusarium is most susceptible in vitro to amphotericin B but often requires toxic dosages to be effective in decreasing fungal load.2,3 The high mortality rate of disseminated fusariosis further emphasizes that prevention is an important component to protecting high-risk patients. Keeping patients in rooms with high-efficiency particulate arresting filters and limiting exposure to unsanitized tap water faucets can help decrease exposure; however, reducing immunosuppression and improving neutropenia are the most effective ways to prevent fusariosis.1 Although skin breakdown can facilitate the spread of infection, it has been observed that immunosuppressed individuals do not necessarily have this finding.4

This case emphasizes the importance of considering disseminated fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancy or other immunosuppressed conditions. The most important factors that should raise clinical suspicion are persistent neutropenia and recent corticosteroid therapy.1 A clinical picture that suggests fungal infection should warrant consideration of prophylactic treatment as well as tissue and blood cultures to determine species and susceptibility.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Fusariosis

Histologic evaluation of the punch biopsy demonstrated thrombosed vessels in the deep dermis and along fibrous septae of subcutaneous tissue, as well as delicate, thin-walled, branching hyphae with vesicular swellings (Figure). The hyphae were present within the vascular thrombi and extended into surrounding tissue. The fungal tissue culture eventually grew scant Fusarium. At the time of biopsy, there was a high index of suspicion for fungal infection, which supported the decision to empirically treat with anidulafungin and voriconazole.

Differentiating the diagnosis in this case was done primarily with histopathology. Although Aspergillus also has slender hyphae, it lacks the vesicular swellings characteristic of fusariosis. Disseminated candidiasis would demonstrate budding yeast and pseudohyphae in the dermis. Ecthyma gangrenosum histologically presents as necrotizing hemorrhagic vasculitis with gram-negative rods in the walls of deeper vessels, characteristically sparing the intima. Leukemia cutis histologically varies but would display a neoplastic infiltrate of atypical monocytoid cells with nuclear pleomorphism.

Our patient had been treated with palliative chemotherapy as a salvage regimen with idarubicin and cytarabine. She had persistent pancytopenia despite granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor therapy. The mortality rate for disseminated Fusarium infection approaches 100% when risk factors such as angiotropism and prolonged neutropenia are present.1,2 Additionally, our patient's susceptibility profile subsequently demonstrated an elevated minimum inhibitory concentration to amphotericin B, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole. The neutropenia and Fusarium infection were not responsive to treatment. She was discharged on palliative voriconazole with home hospice care.

Fusarium species are soil-dwelling saprophytes and important plant pathogens that have increasingly emerged as rare but notable causes of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients.1-3 More specifically, Fusarium infection is most commonly observed in patients with hematologic malignancy complicated by persistent neutropenia. The 3 most frequently encountered Fusarium species in human disease are Fusarium solani, Fusarium oxysporum, and Fusarium moniliforme, with F solani being the most virulent.1,2 Infection with Fusarium may manifest as a broad range of presentations depending on the route of entry, such as endophthalmitis, sinusitis, pneumonia, and cutaneous lesions.1 Disseminated infection is marked by skin lesions or positive blood cultures for Fusarium.3 This fungus is notorious for its limited susceptibility profile.1 It requires systemic antifungal medications such as triazoles and amphotericin B. Fusarium is most susceptible in vitro to amphotericin B but often requires toxic dosages to be effective in decreasing fungal load.2,3 The high mortality rate of disseminated fusariosis further emphasizes that prevention is an important component to protecting high-risk patients. Keeping patients in rooms with high-efficiency particulate arresting filters and limiting exposure to unsanitized tap water faucets can help decrease exposure; however, reducing immunosuppression and improving neutropenia are the most effective ways to prevent fusariosis.1 Although skin breakdown can facilitate the spread of infection, it has been observed that immunosuppressed individuals do not necessarily have this finding.4

This case emphasizes the importance of considering disseminated fusariosis in patients with hematologic malignancy or other immunosuppressed conditions. The most important factors that should raise clinical suspicion are persistent neutropenia and recent corticosteroid therapy.1 A clinical picture that suggests fungal infection should warrant consideration of prophylactic treatment as well as tissue and blood cultures to determine species and susceptibility.

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:695-704.

- Jossi M, Ambrosioni J, Macedo-Vinas M, et al. Invasive fusariosis with prolonged fungemia in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E354-E356.

- Tan R, Ng KP, Gan GG, et al. Fusarium sp. infection in a patient with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68:479-480.

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:909-920.

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Fusarium infections in immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:695-704.

- Jossi M, Ambrosioni J, Macedo-Vinas M, et al. Invasive fusariosis with prolonged fungemia in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: case report and review of the literature. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E354-E356.

- Tan R, Ng KP, Gan GG, et al. Fusarium sp. infection in a patient with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68:479-480.

- Nucci M, Anaissie E. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:909-920.

Acral Cutaneous Metastasis From a Primary Breast Carcinoma Following Chemotherapy With Bevacizumab and Paclitaxel

Cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancy is a relatively uncommon phenomenon, with an overall incidence of 5.3% in cancer patients.1 Cutaneous involvement typically occurs late in the course of disease but can occasionally be the first extranodal sign of metastatic disease. Breast cancer has the highest rate of cutaneous metastasis, most often involving the chest wall1; however, cutaneous metastasis to the acral sites is exceedingly rare. The hand is the site of 0.1% of all metastatic lesions, with only 10% of these being cutaneous lesions and the remaining 90% being osseous metastases.2 Herein, we report a case of multiple cutaneous metastases to acral sites involving the palmar and plantar surfaces of the hands and feet.

Case Report

A 54-year-old black woman with a history of stage IV carcinoma of the breast was admitted to the university medical center with exquisitely painful cutaneous nodules on the hands and feet of 5 weeks’ duration that had started to cause difficulty with walking and daily activities. The patient reported that the breast carcinoma had initially been diagnosed in Nigeria 2 years prior, but she did not receive treatment until moving to the United States. She received a total of 4 cycles of chemotherapy with paclitaxel and bevacizumab, which was discontinued 6 weeks prior to admission due to pain in the lower extremities that was thought to be secondary to neuropathy. One week after discontinuation of chemotherapy, the patient reported increasing pain in the extremities and new-onset painful nodules on the hands and feet. Treatment with gabapentin as well as several courses of antibiotics failed to improve the condition.

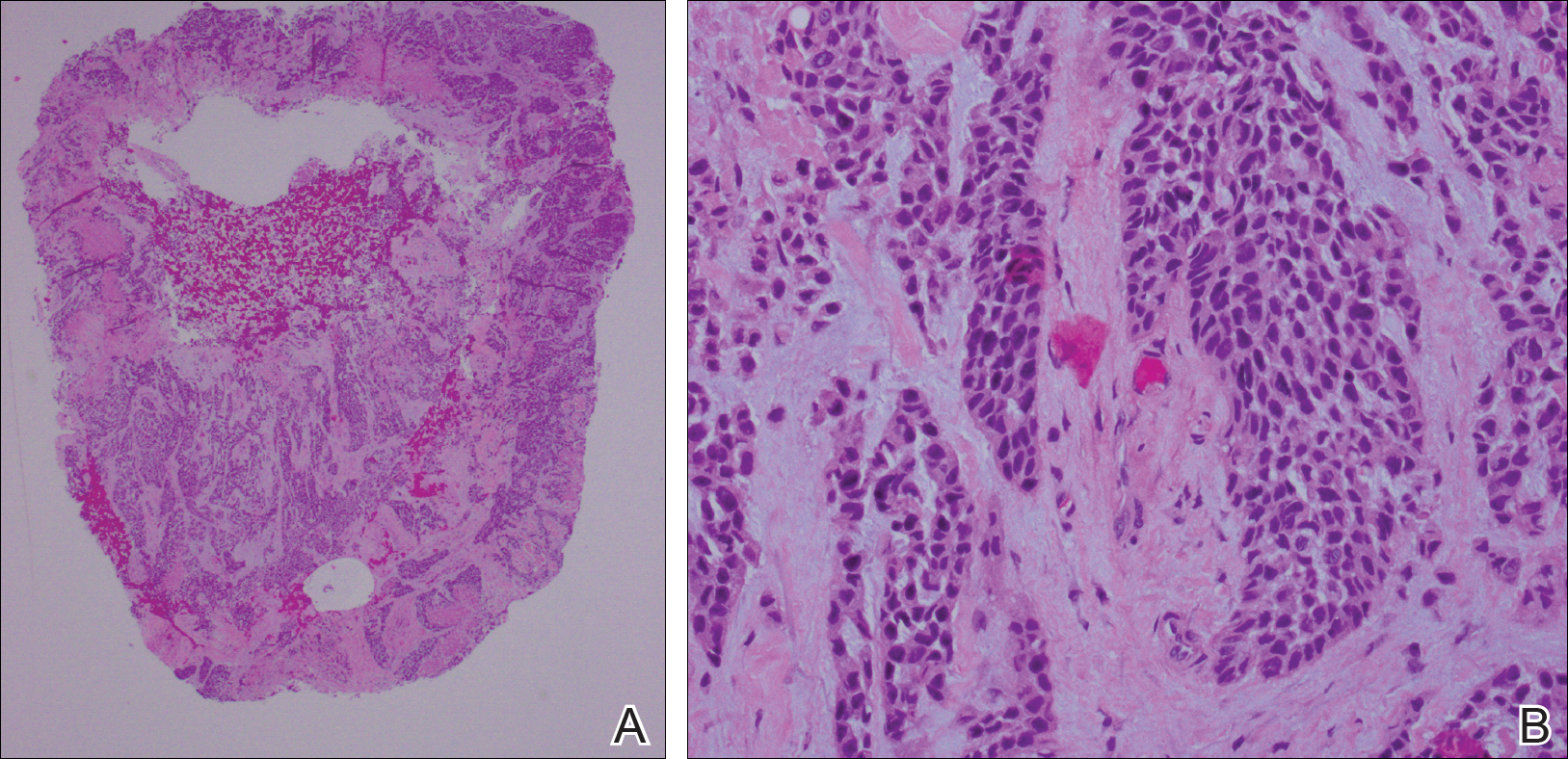

She was admitted for symptomatic pain control and a dermatology consultation. Physical examination revealed multiple firm, tender, subcutaneous nodules on the volar surfaces of the soles, toes, palms, and fingertips (Figure 1). A nodule also was noted on the scalp. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the right fourth finger revealed a dermal carcinoma (Figure 2). On immunohistochemistry, the tumor stained positive for cytokeratin 5/6, cytokeratin 7, and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. It did not demonstrate connection to the epidermis or adnexal structures. Although the tumor did not express estrogen or progesterone receptors, the findings were compatible with metastasis from the patient’s primary breast carcinoma with poor differentiation. A biopsy of the primary breast carcinoma was not available for review from Nigeria.

Comment

The majority of cases reporting acral cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies are unilateral, involving only one extremity. Several hypotheses have been provided, including spread from localized trauma, which causes disruption of blood vessels and consequent extravasation and localization of tumor cells into the extravascular space.3 The distal extremities are particularly vulnerable to trauma, making this hypothesis plausible.

Considering the overall rarity of metastases to acral sites, it is interesting that our patient developed multiple distal nodules on both the hands and feet. The rapid onset of cutaneous nodules shortly after a course of chemotherapy led the team to consider the physiologic effects of paclitaxel and bevacizumab in the etiology of the acral cutaneous metastases. Karamouzis et al3 described a similar case of multiple cutaneous metastases with a bilateral acral distribution. This case also was associated with chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer. The authors proposed hand-foot syndrome, a chemotherapy-related eruption localized to acral skin, as a possible mechanism for hematogenous spread of malignant cells.3 The pathogenesis of hand-foot syndrome is not well understood, but the unique anatomy and physiology of acral skin including temperature gradients, rapidly dividing epidermal cells, absence of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, wide dermal papillae, and exposure to high pressures from carrying body weight and repetitive minor trauma may contribute to the localization of signs and symptoms.3,4 Our case supports a chemotherapy-related etiology of acral cutaneous metastasis of a primary breast cancer; however, our patient did not have apparent signs or symptoms of hand-foot syndrome during the course of treatment. We propose that effects of bevacizumab on acral skin may have contributed to the development of our patient’s metastatic pattern.

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor A, has well-known vascular side effects. Unlike the inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor A provided by the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib, bevacizumab typically is not associated with hand-foot syndrome.5 However, several cases have been reported with chemotherapy-associated palmoplantar eruptions that resolved after withholding bevacizumab while continuing other chemotherapeutic agents, suggesting that bevacizumab-induced changes in acral skin contributed to the eruption.6 Specific factors that could contribute to acral metastasis in patients taking bevacizumab are endothelial dysfunction and capillary rarefaction of the acral skin, as well as hemorrhage, decreased wound healing, and changes in vascular permeability.5,7

We present a rare case of acral cutaneous metastasis associated with bevacizumab, one of few reported cases associated with a taxane chemotherapeutic agent.3 More cases need to be identified and reported to establish a causative association, if indeed existent, between acral cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma and the use of bevacizumab as well as other chemotherapeutic drugs.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:409-410.

- Karamouzis MV, Ardavanis A, Alexopoulos A, et al. Multiple cutaneous acral metastases in a woman with breast adenocarcinoma treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: incidental or aetiological association? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2005;14:267-271.

- Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartin O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand-foot’) syndrome. incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:225-234.

- Wozel G, Sticherling M, Schon MP. Cutaneous side effects of inhibition of VEGF signal transduction. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:243-249.

- Munehiro A, Yoneda K, Nakai K, et al. Bevacizumab-induced hand-foot syndrome: circumscribed type. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1411-1413.

- Mourad JJ, des Guetz G, Debbabi H, et al. Blood pressure rise following angiogenesis inhibition by bevacizumab. a crucial role for microcirculation. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:927-934.

Cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancy is a relatively uncommon phenomenon, with an overall incidence of 5.3% in cancer patients.1 Cutaneous involvement typically occurs late in the course of disease but can occasionally be the first extranodal sign of metastatic disease. Breast cancer has the highest rate of cutaneous metastasis, most often involving the chest wall1; however, cutaneous metastasis to the acral sites is exceedingly rare. The hand is the site of 0.1% of all metastatic lesions, with only 10% of these being cutaneous lesions and the remaining 90% being osseous metastases.2 Herein, we report a case of multiple cutaneous metastases to acral sites involving the palmar and plantar surfaces of the hands and feet.

Case Report

A 54-year-old black woman with a history of stage IV carcinoma of the breast was admitted to the university medical center with exquisitely painful cutaneous nodules on the hands and feet of 5 weeks’ duration that had started to cause difficulty with walking and daily activities. The patient reported that the breast carcinoma had initially been diagnosed in Nigeria 2 years prior, but she did not receive treatment until moving to the United States. She received a total of 4 cycles of chemotherapy with paclitaxel and bevacizumab, which was discontinued 6 weeks prior to admission due to pain in the lower extremities that was thought to be secondary to neuropathy. One week after discontinuation of chemotherapy, the patient reported increasing pain in the extremities and new-onset painful nodules on the hands and feet. Treatment with gabapentin as well as several courses of antibiotics failed to improve the condition.

She was admitted for symptomatic pain control and a dermatology consultation. Physical examination revealed multiple firm, tender, subcutaneous nodules on the volar surfaces of the soles, toes, palms, and fingertips (Figure 1). A nodule also was noted on the scalp. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the right fourth finger revealed a dermal carcinoma (Figure 2). On immunohistochemistry, the tumor stained positive for cytokeratin 5/6, cytokeratin 7, and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. It did not demonstrate connection to the epidermis or adnexal structures. Although the tumor did not express estrogen or progesterone receptors, the findings were compatible with metastasis from the patient’s primary breast carcinoma with poor differentiation. A biopsy of the primary breast carcinoma was not available for review from Nigeria.

Comment

The majority of cases reporting acral cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies are unilateral, involving only one extremity. Several hypotheses have been provided, including spread from localized trauma, which causes disruption of blood vessels and consequent extravasation and localization of tumor cells into the extravascular space.3 The distal extremities are particularly vulnerable to trauma, making this hypothesis plausible.

Considering the overall rarity of metastases to acral sites, it is interesting that our patient developed multiple distal nodules on both the hands and feet. The rapid onset of cutaneous nodules shortly after a course of chemotherapy led the team to consider the physiologic effects of paclitaxel and bevacizumab in the etiology of the acral cutaneous metastases. Karamouzis et al3 described a similar case of multiple cutaneous metastases with a bilateral acral distribution. This case also was associated with chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer. The authors proposed hand-foot syndrome, a chemotherapy-related eruption localized to acral skin, as a possible mechanism for hematogenous spread of malignant cells.3 The pathogenesis of hand-foot syndrome is not well understood, but the unique anatomy and physiology of acral skin including temperature gradients, rapidly dividing epidermal cells, absence of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, wide dermal papillae, and exposure to high pressures from carrying body weight and repetitive minor trauma may contribute to the localization of signs and symptoms.3,4 Our case supports a chemotherapy-related etiology of acral cutaneous metastasis of a primary breast cancer; however, our patient did not have apparent signs or symptoms of hand-foot syndrome during the course of treatment. We propose that effects of bevacizumab on acral skin may have contributed to the development of our patient’s metastatic pattern.

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor A, has well-known vascular side effects. Unlike the inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor A provided by the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib, bevacizumab typically is not associated with hand-foot syndrome.5 However, several cases have been reported with chemotherapy-associated palmoplantar eruptions that resolved after withholding bevacizumab while continuing other chemotherapeutic agents, suggesting that bevacizumab-induced changes in acral skin contributed to the eruption.6 Specific factors that could contribute to acral metastasis in patients taking bevacizumab are endothelial dysfunction and capillary rarefaction of the acral skin, as well as hemorrhage, decreased wound healing, and changes in vascular permeability.5,7

We present a rare case of acral cutaneous metastasis associated with bevacizumab, one of few reported cases associated with a taxane chemotherapeutic agent.3 More cases need to be identified and reported to establish a causative association, if indeed existent, between acral cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma and the use of bevacizumab as well as other chemotherapeutic drugs.

Cutaneous metastasis of internal malignancy is a relatively uncommon phenomenon, with an overall incidence of 5.3% in cancer patients.1 Cutaneous involvement typically occurs late in the course of disease but can occasionally be the first extranodal sign of metastatic disease. Breast cancer has the highest rate of cutaneous metastasis, most often involving the chest wall1; however, cutaneous metastasis to the acral sites is exceedingly rare. The hand is the site of 0.1% of all metastatic lesions, with only 10% of these being cutaneous lesions and the remaining 90% being osseous metastases.2 Herein, we report a case of multiple cutaneous metastases to acral sites involving the palmar and plantar surfaces of the hands and feet.

Case Report

A 54-year-old black woman with a history of stage IV carcinoma of the breast was admitted to the university medical center with exquisitely painful cutaneous nodules on the hands and feet of 5 weeks’ duration that had started to cause difficulty with walking and daily activities. The patient reported that the breast carcinoma had initially been diagnosed in Nigeria 2 years prior, but she did not receive treatment until moving to the United States. She received a total of 4 cycles of chemotherapy with paclitaxel and bevacizumab, which was discontinued 6 weeks prior to admission due to pain in the lower extremities that was thought to be secondary to neuropathy. One week after discontinuation of chemotherapy, the patient reported increasing pain in the extremities and new-onset painful nodules on the hands and feet. Treatment with gabapentin as well as several courses of antibiotics failed to improve the condition.

She was admitted for symptomatic pain control and a dermatology consultation. Physical examination revealed multiple firm, tender, subcutaneous nodules on the volar surfaces of the soles, toes, palms, and fingertips (Figure 1). A nodule also was noted on the scalp. A punch biopsy of a nodule on the right fourth finger revealed a dermal carcinoma (Figure 2). On immunohistochemistry, the tumor stained positive for cytokeratin 5/6, cytokeratin 7, and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. It did not demonstrate connection to the epidermis or adnexal structures. Although the tumor did not express estrogen or progesterone receptors, the findings were compatible with metastasis from the patient’s primary breast carcinoma with poor differentiation. A biopsy of the primary breast carcinoma was not available for review from Nigeria.

Comment

The majority of cases reporting acral cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies are unilateral, involving only one extremity. Several hypotheses have been provided, including spread from localized trauma, which causes disruption of blood vessels and consequent extravasation and localization of tumor cells into the extravascular space.3 The distal extremities are particularly vulnerable to trauma, making this hypothesis plausible.

Considering the overall rarity of metastases to acral sites, it is interesting that our patient developed multiple distal nodules on both the hands and feet. The rapid onset of cutaneous nodules shortly after a course of chemotherapy led the team to consider the physiologic effects of paclitaxel and bevacizumab in the etiology of the acral cutaneous metastases. Karamouzis et al3 described a similar case of multiple cutaneous metastases with a bilateral acral distribution. This case also was associated with chemotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer. The authors proposed hand-foot syndrome, a chemotherapy-related eruption localized to acral skin, as a possible mechanism for hematogenous spread of malignant cells.3 The pathogenesis of hand-foot syndrome is not well understood, but the unique anatomy and physiology of acral skin including temperature gradients, rapidly dividing epidermal cells, absence of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, wide dermal papillae, and exposure to high pressures from carrying body weight and repetitive minor trauma may contribute to the localization of signs and symptoms.3,4 Our case supports a chemotherapy-related etiology of acral cutaneous metastasis of a primary breast cancer; however, our patient did not have apparent signs or symptoms of hand-foot syndrome during the course of treatment. We propose that effects of bevacizumab on acral skin may have contributed to the development of our patient’s metastatic pattern.

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor A, has well-known vascular side effects. Unlike the inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor A provided by the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib, bevacizumab typically is not associated with hand-foot syndrome.5 However, several cases have been reported with chemotherapy-associated palmoplantar eruptions that resolved after withholding bevacizumab while continuing other chemotherapeutic agents, suggesting that bevacizumab-induced changes in acral skin contributed to the eruption.6 Specific factors that could contribute to acral metastasis in patients taking bevacizumab are endothelial dysfunction and capillary rarefaction of the acral skin, as well as hemorrhage, decreased wound healing, and changes in vascular permeability.5,7

We present a rare case of acral cutaneous metastasis associated with bevacizumab, one of few reported cases associated with a taxane chemotherapeutic agent.3 More cases need to be identified and reported to establish a causative association, if indeed existent, between acral cutaneous metastasis of breast carcinoma and the use of bevacizumab as well as other chemotherapeutic drugs.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:409-410.

- Karamouzis MV, Ardavanis A, Alexopoulos A, et al. Multiple cutaneous acral metastases in a woman with breast adenocarcinoma treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: incidental or aetiological association? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2005;14:267-271.

- Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartin O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand-foot’) syndrome. incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:225-234.

- Wozel G, Sticherling M, Schon MP. Cutaneous side effects of inhibition of VEGF signal transduction. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:243-249.

- Munehiro A, Yoneda K, Nakai K, et al. Bevacizumab-induced hand-foot syndrome: circumscribed type. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1411-1413.

- Mourad JJ, des Guetz G, Debbabi H, et al. Blood pressure rise following angiogenesis inhibition by bevacizumab. a crucial role for microcirculation. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:927-934.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Wu CY, Gao HW, Huang WH, et al. Infection-like acral cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign of an occult breast cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:409-410.

- Karamouzis MV, Ardavanis A, Alexopoulos A, et al. Multiple cutaneous acral metastases in a woman with breast adenocarcinoma treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: incidental or aetiological association? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2005;14:267-271.

- Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartin O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand-foot’) syndrome. incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:225-234.

- Wozel G, Sticherling M, Schon MP. Cutaneous side effects of inhibition of VEGF signal transduction. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:243-249.

- Munehiro A, Yoneda K, Nakai K, et al. Bevacizumab-induced hand-foot syndrome: circumscribed type. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1411-1413.

- Mourad JJ, des Guetz G, Debbabi H, et al. Blood pressure rise following angiogenesis inhibition by bevacizumab. a crucial role for microcirculation. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:927-934.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous involvement of internal malignancy typically occurs late in the disease course but can occasionally be the first extranodal sign of metastatic disease.

- Acral cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies typically is unilateral, involving only one extremity; however, this case demonstrates involvement on both the hands and feet.

- This case support a chemotherapy-related etiology of acral cutaneous metastasis of a primary breast cancer.

Metastatic Vulvovaginal Crohn Disease in the Setting of Well-Controlled Intestinal Disease

The cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) are varied, including pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and metastatic CD (MCD). First described by Parks et al,1 MCD is defined as the occurrence of granulomatous lesions at a skin site distant from the gastrointestinal tract.1-20 Metastatic CD presents a diagnostic challenge because it is a rare component in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease complications, and many physicians are unaware of its existence. It may precede, coincide with, or develop after the diagnosis of intestinal disease.2-5 Vulvoperineal involvement is particularly problematic because a multitude of other, more likely disease processes are considered first. Typically it is initially diagnosed as a presumed infection prompting reflexive treatment with antivirals, antifungals, and antibiotics. Patients may experience symptoms for years prior to correct diagnosis and institution of proper therapy. A variety of clinical presentations have been described, including nonspecific pain and swelling, erythematous papules and plaques, and nonhealing ulcers. Skin biopsy characteristically confirms the diagnosis and reveals dermal noncaseating granulomas. Multiple oral and parenteral therapies are available, with surgical intervention reserved for resistant cases. We present a case of vulvovaginal MCD in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. We also provide a review of the literature regarding genital CD and emphasize the need to keep MCD in the differential of vulvoperineal pathology.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic with vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus of 14 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for CD following a colectomy with colostomy. Prior therapies included methotrexate with infliximab for 5 years followed by a 2-year regimen with adalimumab, which induced remission of the intestinal disease.

The patient previously had taken a variety of topical and oral antimicrobials based on treatment from a primary care physician because fungal, bacterial, and viral infections initially were suspected; however, the vulvar disease persisted, and drug-induced immunosuppression was considered to be an underlying factor. Thus, adalimumab was discontinued. Despite elimination of the biologic, the vulvar disease progressed, which prompted referral to the dermatology clinic.

Physical examination revealed diffuse vulvar edema with overlying erythema and scale (Figure 1A). Upon closer inspection, scattered violaceous papules atop a backdrop of lichenification were evident, imparting a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B). Additionally, a fissure was present on the gluteal cleft. Biopsy from the left labia majora demonstrated well-formed granulomas within a fibrotic reticular dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The granulomas consisted of both mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, rimmed peripherally by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 2C). Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polarizing microscopy were negative.

Given the patient’s history, a diagnosis of vulvoperineal MCD was rendered. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 250 mg 3 times daily with topical fluocinonide and tacrolimus. She responded well to this treatment regimen and was referred back to the gastroenterologist for management of the intestinal disease.

Comment

Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. It is characterized by transmural inflammation and fissures that can extend beyond the muscularis propria.4,6 Extraintestinal manifestations are common.3

Cutaneous CD often presents as perianal, perifistular, or peristomal inflammation or ulceration.7 Other skin manifestations include pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and palmar erythema.7 Metastatic CD involves skin noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal tract1-20 and may involve any portion of the cutis. Although rare, MCD is the typical etiology underlying vulvar CD.8

Approximately 20% of MCD patients have cutaneous lesions without a history of gastrointestinal disease. More than half of cases in adults and approximately two-thirds in children involve the genitalia. Although more common in adults, vulvar involvement has been reported in children as young as 6 years of age.2 Diagnosis is especially challenging when bowel symptoms are absent; those patients should be evaluated and followed for subsequent intestinal involvement.6

Clinically, symptoms may include general discomfort, pain, pruritus, and dyspareunia. Psychosocial and sexual dysfunction are prevalent and also should be addressed.9 Depending on the stage of the disease, physical examination may reveal erythema, edema, papules, pustules, nodules, condylomatous lesions, abscesses, fissures, fistulas, ulceration, acrochordons, and scarring.2-6,10,11

A host of infections (ie, mycobacterial, actinomycosis, deep fungal, sexually transmitted, schistosomiasis), inflammatory conditions (ie, sarcoid, hidradenitis suppurativa), foreign body reactions, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, and sexual abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis.2,6,10-12 Once infection, sarcoid, and foreign body reaction have been ruled out, noncaseating granulomas in skin are highly suggestive of CD.7

Histopathologic findings of MCD reveal myriad morphological reaction patterns,5,13 including high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma of the vulva; therefore, it may be imprudent to withhold diagnosis based on the absence of the historically pathognomonic noncaseating granulomas.5

The etiopathogenesis of MCD remains an enigma. Dermatopathologic examinations consistently reveal a vascular injury syndrome,13 implicating a possible circulatory system contribution via deposition of immune complexes or antigens in skin.7 Bacterial infection has been implicated in the intestinal manifestations of CD; however, failure to detect microbial ribosomal RNA in MCD biopsies refutes theories of hematogenous spread of microbes.13 Another plausible explanation is that antibodies are formed to conserved microbial epitopes following loss of tolerance to gut flora, which results in an excessive immunologic response at distinct sites in susceptible individuals.13 A T-lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also has been proposed via cross-reactivity of lymphocytes, with skin antigens precipitating extraintestinal granuloma formation and vascular injury.3 Clearly, further investigation is needed.

Magnetic resonanance imaging can identify the extent and anatomy of intestinal and pelvic disease and can assist in the diagnosis of vulvar CD.10,11,14 For these reasons, some experts propose that imaging should be instituted prior to therapy,12,15,16 especially when direct extension is suspected.17

Treatment is challenging and often involves collaboration among several specialties.12 Many treatment options exist because therapeutic responses vary and genital MCD is frequently recalcitrant to therapy.4 Medical therapy includes antibiotics such as metronidazole, corticosteroids (ie, topical, intralesional, systemic), and immune modulators (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors).2,3,6,10,16,18 Thalidomide has been used for refractory cases.19 These treatments can be used alone or in combination. Patients should be monitored for side effects and informed that many treatment regimens may be required before a sustained response is achieved.4,16,18 Surgery is reserved for the most resistant cases. Extensive radical excision of the involved area is the best approach, as limited local excision often is followed by recurrence.20

Conclusion

Our case highlights that vulvar CD can develop in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. Vulvoperineal CD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus, especially in cases resistant to standard therapies and regardless of whether or not gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present. Physicians must be cognizant that vulvar signs and symptoms may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of intestinal CD. Increased awareness of this entity may facilitate its early recognition and prompt more timely treatment among women with vulvar disease caused by MCD.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn’s disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulvar metastatic Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, et al. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;33:588-593.

- Urbanek M, Neill SM, McKee PH. Vulval Crohn’s disease: difficulties in diagnosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:211-214.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg. 2010;8:2-5.

- Feller E, Ribaudo S, Jackson N. Gynecologic aspects of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1725-1728.

- Corbett SL, Walsh CM, Spitzer RF, et al. Vulvar inflammation as the only clinical manifestation of Crohn disease in an 8-year-old girl [published online May 10, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E1518-E1522.

- Tonolini M, Villa C, Campari A, et al. Common and unusual urogenital Crohn’s disease complications: spectrum of cross-sectional imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:32-41.

- Bhaduri S, Jenkinson S, Lewis F. Vulval Crohn’s disease—a multi-specialty approach. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:512-514.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Pai D, Dillman JR, Mahani MG, et al. MRI of vulvar Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:537-541.

- Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, et al. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:342-344.

- Makhija S, Trotter M, Wagner E, et al. Refractory Crohn’s disease of the vulva treated with infliximab: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:835-837.

- Fahmy N, Kalidindi M, Khan R. Direct colo-labial Crohn’s abscess mimicking bartholinitis. Am J Obstret Gynecol. 2010;30:741-742.

- Preston PW, Hudson N, Lewis FM. Treatment of vulval Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Clin Exp Derm. 2006;31:378-380.

- Kolivras A, De Maubeuge J, André J, et al. Thalidomide in refractory vulvar ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 2003;206:381-383.

- Kao MS, Paulson JD, Askin FB. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:329-333.

The cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) are varied, including pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and metastatic CD (MCD). First described by Parks et al,1 MCD is defined as the occurrence of granulomatous lesions at a skin site distant from the gastrointestinal tract.1-20 Metastatic CD presents a diagnostic challenge because it is a rare component in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease complications, and many physicians are unaware of its existence. It may precede, coincide with, or develop after the diagnosis of intestinal disease.2-5 Vulvoperineal involvement is particularly problematic because a multitude of other, more likely disease processes are considered first. Typically it is initially diagnosed as a presumed infection prompting reflexive treatment with antivirals, antifungals, and antibiotics. Patients may experience symptoms for years prior to correct diagnosis and institution of proper therapy. A variety of clinical presentations have been described, including nonspecific pain and swelling, erythematous papules and plaques, and nonhealing ulcers. Skin biopsy characteristically confirms the diagnosis and reveals dermal noncaseating granulomas. Multiple oral and parenteral therapies are available, with surgical intervention reserved for resistant cases. We present a case of vulvovaginal MCD in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. We also provide a review of the literature regarding genital CD and emphasize the need to keep MCD in the differential of vulvoperineal pathology.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic with vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus of 14 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for CD following a colectomy with colostomy. Prior therapies included methotrexate with infliximab for 5 years followed by a 2-year regimen with adalimumab, which induced remission of the intestinal disease.

The patient previously had taken a variety of topical and oral antimicrobials based on treatment from a primary care physician because fungal, bacterial, and viral infections initially were suspected; however, the vulvar disease persisted, and drug-induced immunosuppression was considered to be an underlying factor. Thus, adalimumab was discontinued. Despite elimination of the biologic, the vulvar disease progressed, which prompted referral to the dermatology clinic.

Physical examination revealed diffuse vulvar edema with overlying erythema and scale (Figure 1A). Upon closer inspection, scattered violaceous papules atop a backdrop of lichenification were evident, imparting a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B). Additionally, a fissure was present on the gluteal cleft. Biopsy from the left labia majora demonstrated well-formed granulomas within a fibrotic reticular dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The granulomas consisted of both mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, rimmed peripherally by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 2C). Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polarizing microscopy were negative.

Given the patient’s history, a diagnosis of vulvoperineal MCD was rendered. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 250 mg 3 times daily with topical fluocinonide and tacrolimus. She responded well to this treatment regimen and was referred back to the gastroenterologist for management of the intestinal disease.

Comment

Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. It is characterized by transmural inflammation and fissures that can extend beyond the muscularis propria.4,6 Extraintestinal manifestations are common.3

Cutaneous CD often presents as perianal, perifistular, or peristomal inflammation or ulceration.7 Other skin manifestations include pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and palmar erythema.7 Metastatic CD involves skin noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal tract1-20 and may involve any portion of the cutis. Although rare, MCD is the typical etiology underlying vulvar CD.8

Approximately 20% of MCD patients have cutaneous lesions without a history of gastrointestinal disease. More than half of cases in adults and approximately two-thirds in children involve the genitalia. Although more common in adults, vulvar involvement has been reported in children as young as 6 years of age.2 Diagnosis is especially challenging when bowel symptoms are absent; those patients should be evaluated and followed for subsequent intestinal involvement.6

Clinically, symptoms may include general discomfort, pain, pruritus, and dyspareunia. Psychosocial and sexual dysfunction are prevalent and also should be addressed.9 Depending on the stage of the disease, physical examination may reveal erythema, edema, papules, pustules, nodules, condylomatous lesions, abscesses, fissures, fistulas, ulceration, acrochordons, and scarring.2-6,10,11

A host of infections (ie, mycobacterial, actinomycosis, deep fungal, sexually transmitted, schistosomiasis), inflammatory conditions (ie, sarcoid, hidradenitis suppurativa), foreign body reactions, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, and sexual abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis.2,6,10-12 Once infection, sarcoid, and foreign body reaction have been ruled out, noncaseating granulomas in skin are highly suggestive of CD.7

Histopathologic findings of MCD reveal myriad morphological reaction patterns,5,13 including high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma of the vulva; therefore, it may be imprudent to withhold diagnosis based on the absence of the historically pathognomonic noncaseating granulomas.5

The etiopathogenesis of MCD remains an enigma. Dermatopathologic examinations consistently reveal a vascular injury syndrome,13 implicating a possible circulatory system contribution via deposition of immune complexes or antigens in skin.7 Bacterial infection has been implicated in the intestinal manifestations of CD; however, failure to detect microbial ribosomal RNA in MCD biopsies refutes theories of hematogenous spread of microbes.13 Another plausible explanation is that antibodies are formed to conserved microbial epitopes following loss of tolerance to gut flora, which results in an excessive immunologic response at distinct sites in susceptible individuals.13 A T-lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also has been proposed via cross-reactivity of lymphocytes, with skin antigens precipitating extraintestinal granuloma formation and vascular injury.3 Clearly, further investigation is needed.

Magnetic resonanance imaging can identify the extent and anatomy of intestinal and pelvic disease and can assist in the diagnosis of vulvar CD.10,11,14 For these reasons, some experts propose that imaging should be instituted prior to therapy,12,15,16 especially when direct extension is suspected.17

Treatment is challenging and often involves collaboration among several specialties.12 Many treatment options exist because therapeutic responses vary and genital MCD is frequently recalcitrant to therapy.4 Medical therapy includes antibiotics such as metronidazole, corticosteroids (ie, topical, intralesional, systemic), and immune modulators (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors).2,3,6,10,16,18 Thalidomide has been used for refractory cases.19 These treatments can be used alone or in combination. Patients should be monitored for side effects and informed that many treatment regimens may be required before a sustained response is achieved.4,16,18 Surgery is reserved for the most resistant cases. Extensive radical excision of the involved area is the best approach, as limited local excision often is followed by recurrence.20

Conclusion

Our case highlights that vulvar CD can develop in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. Vulvoperineal CD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus, especially in cases resistant to standard therapies and regardless of whether or not gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present. Physicians must be cognizant that vulvar signs and symptoms may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of intestinal CD. Increased awareness of this entity may facilitate its early recognition and prompt more timely treatment among women with vulvar disease caused by MCD.

The cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease (CD) are varied, including pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, and metastatic CD (MCD). First described by Parks et al,1 MCD is defined as the occurrence of granulomatous lesions at a skin site distant from the gastrointestinal tract.1-20 Metastatic CD presents a diagnostic challenge because it is a rare component in the spectrum of inflammatory bowel disease complications, and many physicians are unaware of its existence. It may precede, coincide with, or develop after the diagnosis of intestinal disease.2-5 Vulvoperineal involvement is particularly problematic because a multitude of other, more likely disease processes are considered first. Typically it is initially diagnosed as a presumed infection prompting reflexive treatment with antivirals, antifungals, and antibiotics. Patients may experience symptoms for years prior to correct diagnosis and institution of proper therapy. A variety of clinical presentations have been described, including nonspecific pain and swelling, erythematous papules and plaques, and nonhealing ulcers. Skin biopsy characteristically confirms the diagnosis and reveals dermal noncaseating granulomas. Multiple oral and parenteral therapies are available, with surgical intervention reserved for resistant cases. We present a case of vulvovaginal MCD in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. We also provide a review of the literature regarding genital CD and emphasize the need to keep MCD in the differential of vulvoperineal pathology.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic with vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus of 14 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for CD following a colectomy with colostomy. Prior therapies included methotrexate with infliximab for 5 years followed by a 2-year regimen with adalimumab, which induced remission of the intestinal disease.

The patient previously had taken a variety of topical and oral antimicrobials based on treatment from a primary care physician because fungal, bacterial, and viral infections initially were suspected; however, the vulvar disease persisted, and drug-induced immunosuppression was considered to be an underlying factor. Thus, adalimumab was discontinued. Despite elimination of the biologic, the vulvar disease progressed, which prompted referral to the dermatology clinic.

Physical examination revealed diffuse vulvar edema with overlying erythema and scale (Figure 1A). Upon closer inspection, scattered violaceous papules atop a backdrop of lichenification were evident, imparting a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B). Additionally, a fissure was present on the gluteal cleft. Biopsy from the left labia majora demonstrated well-formed granulomas within a fibrotic reticular dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The granulomas consisted of both mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, rimmed peripherally by lymphocytes and plasma cells (Figure 2C). Periodic acid–Schiff–diastase and acid-fast bacilli stains as well as polarizing microscopy were negative.

Given the patient’s history, a diagnosis of vulvoperineal MCD was rendered. The patient was started on oral metronidazole 250 mg 3 times daily with topical fluocinonide and tacrolimus. She responded well to this treatment regimen and was referred back to the gastroenterologist for management of the intestinal disease.

Comment

Crohn disease is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory condition that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. It is characterized by transmural inflammation and fissures that can extend beyond the muscularis propria.4,6 Extraintestinal manifestations are common.3

Cutaneous CD often presents as perianal, perifistular, or peristomal inflammation or ulceration.7 Other skin manifestations include pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and palmar erythema.7 Metastatic CD involves skin noncontiguous with the gastrointestinal tract1-20 and may involve any portion of the cutis. Although rare, MCD is the typical etiology underlying vulvar CD.8

Approximately 20% of MCD patients have cutaneous lesions without a history of gastrointestinal disease. More than half of cases in adults and approximately two-thirds in children involve the genitalia. Although more common in adults, vulvar involvement has been reported in children as young as 6 years of age.2 Diagnosis is especially challenging when bowel symptoms are absent; those patients should be evaluated and followed for subsequent intestinal involvement.6

Clinically, symptoms may include general discomfort, pain, pruritus, and dyspareunia. Psychosocial and sexual dysfunction are prevalent and also should be addressed.9 Depending on the stage of the disease, physical examination may reveal erythema, edema, papules, pustules, nodules, condylomatous lesions, abscesses, fissures, fistulas, ulceration, acrochordons, and scarring.2-6,10,11

A host of infections (ie, mycobacterial, actinomycosis, deep fungal, sexually transmitted, schistosomiasis), inflammatory conditions (ie, sarcoid, hidradenitis suppurativa), foreign body reactions, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome, and sexual abuse should be included in the differential diagnosis.2,6,10-12 Once infection, sarcoid, and foreign body reaction have been ruled out, noncaseating granulomas in skin are highly suggestive of CD.7

Histopathologic findings of MCD reveal myriad morphological reaction patterns,5,13 including high-grade dysplasia and carcinoma of the vulva; therefore, it may be imprudent to withhold diagnosis based on the absence of the historically pathognomonic noncaseating granulomas.5

The etiopathogenesis of MCD remains an enigma. Dermatopathologic examinations consistently reveal a vascular injury syndrome,13 implicating a possible circulatory system contribution via deposition of immune complexes or antigens in skin.7 Bacterial infection has been implicated in the intestinal manifestations of CD; however, failure to detect microbial ribosomal RNA in MCD biopsies refutes theories of hematogenous spread of microbes.13 Another plausible explanation is that antibodies are formed to conserved microbial epitopes following loss of tolerance to gut flora, which results in an excessive immunologic response at distinct sites in susceptible individuals.13 A T-lymphocyte–mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction also has been proposed via cross-reactivity of lymphocytes, with skin antigens precipitating extraintestinal granuloma formation and vascular injury.3 Clearly, further investigation is needed.

Magnetic resonanance imaging can identify the extent and anatomy of intestinal and pelvic disease and can assist in the diagnosis of vulvar CD.10,11,14 For these reasons, some experts propose that imaging should be instituted prior to therapy,12,15,16 especially when direct extension is suspected.17

Treatment is challenging and often involves collaboration among several specialties.12 Many treatment options exist because therapeutic responses vary and genital MCD is frequently recalcitrant to therapy.4 Medical therapy includes antibiotics such as metronidazole, corticosteroids (ie, topical, intralesional, systemic), and immune modulators (eg, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors).2,3,6,10,16,18 Thalidomide has been used for refractory cases.19 These treatments can be used alone or in combination. Patients should be monitored for side effects and informed that many treatment regimens may be required before a sustained response is achieved.4,16,18 Surgery is reserved for the most resistant cases. Extensive radical excision of the involved area is the best approach, as limited local excision often is followed by recurrence.20

Conclusion

Our case highlights that vulvar CD can develop in the setting of well-controlled intestinal disease. Vulvoperineal CD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chronic vulvar pain, swelling, and pruritus, especially in cases resistant to standard therapies and regardless of whether or not gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present. Physicians must be cognizant that vulvar signs and symptoms may precede, coincide with, or follow the diagnosis of intestinal CD. Increased awareness of this entity may facilitate its early recognition and prompt more timely treatment among women with vulvar disease caused by MCD.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn’s disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulvar metastatic Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, et al. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;33:588-593.

- Urbanek M, Neill SM, McKee PH. Vulval Crohn’s disease: difficulties in diagnosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:211-214.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg. 2010;8:2-5.

- Feller E, Ribaudo S, Jackson N. Gynecologic aspects of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1725-1728.

- Corbett SL, Walsh CM, Spitzer RF, et al. Vulvar inflammation as the only clinical manifestation of Crohn disease in an 8-year-old girl [published online May 10, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E1518-E1522.

- Tonolini M, Villa C, Campari A, et al. Common and unusual urogenital Crohn’s disease complications: spectrum of cross-sectional imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:32-41.

- Bhaduri S, Jenkinson S, Lewis F. Vulval Crohn’s disease—a multi-specialty approach. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:512-514.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Pai D, Dillman JR, Mahani MG, et al. MRI of vulvar Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:537-541.

- Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, et al. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:342-344.

- Makhija S, Trotter M, Wagner E, et al. Refractory Crohn’s disease of the vulva treated with infliximab: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:835-837.

- Fahmy N, Kalidindi M, Khan R. Direct colo-labial Crohn’s abscess mimicking bartholinitis. Am J Obstret Gynecol. 2010;30:741-742.

- Preston PW, Hudson N, Lewis FM. Treatment of vulval Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Clin Exp Derm. 2006;31:378-380.

- Kolivras A, De Maubeuge J, André J, et al. Thalidomide in refractory vulvar ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 2003;206:381-383.

- Kao MS, Paulson JD, Askin FB. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:329-333.

- Parks AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241-242.

- Ploysangam T, Heubi JE, Eisen D, et al. Cutaneous Crohn’s disease in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:697-704.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Leu S, Sun PK, Collyer J, et al. Clinical spectrum of vulvar metastatic Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1565-1571.

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, et al. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;33:588-593.

- Urbanek M, Neill SM, McKee PH. Vulval Crohn’s disease: difficulties in diagnosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:211-214.

- Burgdorf W. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:689-695.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, et al. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg. 2010;8:2-5.

- Feller E, Ribaudo S, Jackson N. Gynecologic aspects of Crohn’s disease. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1725-1728.

- Corbett SL, Walsh CM, Spitzer RF, et al. Vulvar inflammation as the only clinical manifestation of Crohn disease in an 8-year-old girl [published online May 10, 2010]. Pediatrics. 2010;125:E1518-E1522.

- Tonolini M, Villa C, Campari A, et al. Common and unusual urogenital Crohn’s disease complications: spectrum of cross-sectional imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:32-41.

- Bhaduri S, Jenkinson S, Lewis F. Vulval Crohn’s disease—a multi-specialty approach. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:512-514.

- Crowson AN, Nuovo GJ, Mihm MC Jr, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease, its spectrum, and its pathogenesis: intracellular consensus bacterial 16S rRNA is associated with the gastrointestinal but not the cutaneous manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1185-1192.

- Pai D, Dillman JR, Mahani MG, et al. MRI of vulvar Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41:537-541.

- Madnani NA, Desai D, Gandhi N, et al. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:342-344.

- Makhija S, Trotter M, Wagner E, et al. Refractory Crohn’s disease of the vulva treated with infliximab: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:835-837.

- Fahmy N, Kalidindi M, Khan R. Direct colo-labial Crohn’s abscess mimicking bartholinitis. Am J Obstret Gynecol. 2010;30:741-742.

- Preston PW, Hudson N, Lewis FM. Treatment of vulval Crohn’s disease with infliximab. Clin Exp Derm. 2006;31:378-380.

- Kolivras A, De Maubeuge J, André J, et al. Thalidomide in refractory vulvar ulcerations associated with Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 2003;206:381-383.

- Kao MS, Paulson JD, Askin FB. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:329-333.