User login

Approaching intraoperative bowel injury

Enterotomy can be a serious complication in abdominopelvic surgery, particularly if it is not immediately recognized and treated. Risk of visceral injury increases when complex dissection is required for treatment of cancer, resection of endometriosis, and extensive lysis of adhesions.

In a retrospective review from 1984 to 2003, investigators assessed intestinal injuries at the time of gynecologic operations. Of the 110 cases reported, about 37% occurred during the opening of the peritoneal cavity, 38% during adhesiolysis and pelvic dissection, 9% during laparoscopy, 9% during vaginal surgery, and 8% during dilation and curettage. Of the bowel injuries, more than 75% were minor.1 Mortality from unrecognized bowel injury is significant, and as such, appropriate recognition and management of these injuries is critical.2

Some basic principles are critical when surgeons face a bowel injury:

1. Recognize the extent of the injury, including the size of the breach, the depth (full or partial thickness), and the nature of the injury (thermal or cold).

2. Assess the integrity of the bowel, including adequacy of blood supply, prior bowel damage from radiation, and absence of downstream obstruction.

3. Ensure no other occult injuries exist in other segments.

4. Obtain adequate exposure and mobilization of the bowel beyond the site of injury, including the adjacent bowel. This involves releasing other adhesions so that adequate bowel length is available for a tension-free repair.

Methods of repair

The decision to employ each is influenced by multiple factors. Primary closure is best suited to small lesions (1 cm or less) that are a result of cold or sharp injury. However, thermal injury sustained via electrosurgical devices induces delayed tissue damage beyond the visible edges of the immediate defect, and surgeons should consider a resection of bowel to at least 1 cm beyond the immediately apparent injury site. Additionally, resection and re-anastamosis should also be considered if the damaged segment of bowel has poor blood supply, integrity, or the repair would result in tension along the suture/staple line or luminal narrowing.

Simple small bowel closures

Serosal abrasions need not be repaired; however, small tears of the serosa and muscularis can be managed with a single layer of interrupted 3-0 absorbable or permanent silk suture on a tapered needle. The suture line should be perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bowel at 2-mm to 3-mm intervals in order to prevent narrowing of the lumen. The suture should pass through serosal and muscular layers in an imbricating (Lembert) stitch. For smaller defects of less than 6 mm, a single layer closure is typically adequate.

Small bowel resection

Some larger defects, thermal injuries, and segments with multiple enterotomies may be best repaired with resection and re-anastamosis technique. A segment of resectable bowel is chosen such that the afferent and efferent limbs to be re-anastamosed can be reapproximated in a tension-free fashion. A mesenterotomy is made at the proximal and distal portions of the involved bowel. A gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is then inserted perpendicularly across the bowel. The remaining wedge of connected mesentery can then be efficiently excised with an electrothermal bipolar coagulator device ensuring that maximal mesentery and blood supply are preserved to the remaining limbs of intestine. The proximal and distal segments are then aligned at the antimesenteric sides.

Large bowel repair

Defects in the serosa and small lacerations can be managed with a primary closure, similar to the small intestine. For more extensive injuries that may require resection, diversion, or complicated repair, consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or general or colorectal surgeon may be indicated as colotomy repairs are associated with higher rates of breakdown and fistula. If fecal contamination is present, copious irrigation should be performed and placement of a peritoneal drain to reduce the likelihood of abscess formation should be considered. If appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for colonic surgery has not been given prior to skin incision, it should be administered once the colotomy is identified.

Standard prophylaxis for hysterectomy (such as a first-generation cephalosporin like cefazolin) is not adequate for large bowel surgery, and either metronidazole should be added or a second-generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin should be given. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin with either gentamicin or a fluoroquinolone should be administered.6

Postoperative management

The potential for postoperative morbidity must be understood for appropriate management following bowel surgery. Ileus is common and the clinician should understand how to diagnose and manage it. Additionally, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, fistula formation, and mechanical obstruction are complications that may require surgical intervention and must be vigilantly managed.

The routine use of postoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) does not hasten return of bowel function or prevent leak from sites of gastrointestinal repair. In fact, early feeding has been associated with reduced perioperative complications and earlier return of bowel function has been observed without the use of NGT.7 In general, for small and large intestinal injuries, early feeding is considered acceptable.8

Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis, beyond 24 hours, is not recommended.6

Avoiding injury

Gynecologic surgeons should adhere to surgical principles with sharp dissection for adhesions, gentle tissue handling, adequate exposure, and light retraction to prevent bowel injury or minimize their extent. Laparoscopic entry sites should be chosen based on the likelihood of abdominal adhesions. When the patient’s history predicts a high likelihood of intraperitoneal adhesions, the left upper quadrant site should be strongly considered as the entry site. The likelihood of gastrointestinal injury is not influenced by open versus closed laparoscopic entry and surgeons should use the technique with which they have the greatest experience and skill.9 However, in patients who have had prior laparotomies, there is an increased risk of periumbilical adhesions, and consideration should be made for a nonumbilical entry site.10 Methodical sharp dissection and sparing use of thermal energy should be used with adhesiolysis. When injury occurs, prompt recognition, preparation, and methodical management can mitigate the impact.

Dr. Staley is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Int Surg. 2006 Nov-Dec;91(6):336-40.

2. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Jun;192(6):677-83.

3. Doherty, G. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Surgery. Thirteenth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010.

4. Hoffman B. Williams Gynecology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2016.

5. Berek J, Hacker N. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

6. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;14(1):73-156.

7. Br J Surg. 2005 Jun;92(6):673-80.

8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jul;185(1):1-4.

9. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 31;8:CD006583.

10. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):595-600.

Enterotomy can be a serious complication in abdominopelvic surgery, particularly if it is not immediately recognized and treated. Risk of visceral injury increases when complex dissection is required for treatment of cancer, resection of endometriosis, and extensive lysis of adhesions.

In a retrospective review from 1984 to 2003, investigators assessed intestinal injuries at the time of gynecologic operations. Of the 110 cases reported, about 37% occurred during the opening of the peritoneal cavity, 38% during adhesiolysis and pelvic dissection, 9% during laparoscopy, 9% during vaginal surgery, and 8% during dilation and curettage. Of the bowel injuries, more than 75% were minor.1 Mortality from unrecognized bowel injury is significant, and as such, appropriate recognition and management of these injuries is critical.2

Some basic principles are critical when surgeons face a bowel injury:

1. Recognize the extent of the injury, including the size of the breach, the depth (full or partial thickness), and the nature of the injury (thermal or cold).

2. Assess the integrity of the bowel, including adequacy of blood supply, prior bowel damage from radiation, and absence of downstream obstruction.

3. Ensure no other occult injuries exist in other segments.

4. Obtain adequate exposure and mobilization of the bowel beyond the site of injury, including the adjacent bowel. This involves releasing other adhesions so that adequate bowel length is available for a tension-free repair.

Methods of repair

The decision to employ each is influenced by multiple factors. Primary closure is best suited to small lesions (1 cm or less) that are a result of cold or sharp injury. However, thermal injury sustained via electrosurgical devices induces delayed tissue damage beyond the visible edges of the immediate defect, and surgeons should consider a resection of bowel to at least 1 cm beyond the immediately apparent injury site. Additionally, resection and re-anastamosis should also be considered if the damaged segment of bowel has poor blood supply, integrity, or the repair would result in tension along the suture/staple line or luminal narrowing.

Simple small bowel closures

Serosal abrasions need not be repaired; however, small tears of the serosa and muscularis can be managed with a single layer of interrupted 3-0 absorbable or permanent silk suture on a tapered needle. The suture line should be perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bowel at 2-mm to 3-mm intervals in order to prevent narrowing of the lumen. The suture should pass through serosal and muscular layers in an imbricating (Lembert) stitch. For smaller defects of less than 6 mm, a single layer closure is typically adequate.

Small bowel resection

Some larger defects, thermal injuries, and segments with multiple enterotomies may be best repaired with resection and re-anastamosis technique. A segment of resectable bowel is chosen such that the afferent and efferent limbs to be re-anastamosed can be reapproximated in a tension-free fashion. A mesenterotomy is made at the proximal and distal portions of the involved bowel. A gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is then inserted perpendicularly across the bowel. The remaining wedge of connected mesentery can then be efficiently excised with an electrothermal bipolar coagulator device ensuring that maximal mesentery and blood supply are preserved to the remaining limbs of intestine. The proximal and distal segments are then aligned at the antimesenteric sides.

Large bowel repair

Defects in the serosa and small lacerations can be managed with a primary closure, similar to the small intestine. For more extensive injuries that may require resection, diversion, or complicated repair, consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or general or colorectal surgeon may be indicated as colotomy repairs are associated with higher rates of breakdown and fistula. If fecal contamination is present, copious irrigation should be performed and placement of a peritoneal drain to reduce the likelihood of abscess formation should be considered. If appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for colonic surgery has not been given prior to skin incision, it should be administered once the colotomy is identified.

Standard prophylaxis for hysterectomy (such as a first-generation cephalosporin like cefazolin) is not adequate for large bowel surgery, and either metronidazole should be added or a second-generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin should be given. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin with either gentamicin or a fluoroquinolone should be administered.6

Postoperative management

The potential for postoperative morbidity must be understood for appropriate management following bowel surgery. Ileus is common and the clinician should understand how to diagnose and manage it. Additionally, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, fistula formation, and mechanical obstruction are complications that may require surgical intervention and must be vigilantly managed.

The routine use of postoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) does not hasten return of bowel function or prevent leak from sites of gastrointestinal repair. In fact, early feeding has been associated with reduced perioperative complications and earlier return of bowel function has been observed without the use of NGT.7 In general, for small and large intestinal injuries, early feeding is considered acceptable.8

Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis, beyond 24 hours, is not recommended.6

Avoiding injury

Gynecologic surgeons should adhere to surgical principles with sharp dissection for adhesions, gentle tissue handling, adequate exposure, and light retraction to prevent bowel injury or minimize their extent. Laparoscopic entry sites should be chosen based on the likelihood of abdominal adhesions. When the patient’s history predicts a high likelihood of intraperitoneal adhesions, the left upper quadrant site should be strongly considered as the entry site. The likelihood of gastrointestinal injury is not influenced by open versus closed laparoscopic entry and surgeons should use the technique with which they have the greatest experience and skill.9 However, in patients who have had prior laparotomies, there is an increased risk of periumbilical adhesions, and consideration should be made for a nonumbilical entry site.10 Methodical sharp dissection and sparing use of thermal energy should be used with adhesiolysis. When injury occurs, prompt recognition, preparation, and methodical management can mitigate the impact.

Dr. Staley is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Int Surg. 2006 Nov-Dec;91(6):336-40.

2. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Jun;192(6):677-83.

3. Doherty, G. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Surgery. Thirteenth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010.

4. Hoffman B. Williams Gynecology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2016.

5. Berek J, Hacker N. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

6. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;14(1):73-156.

7. Br J Surg. 2005 Jun;92(6):673-80.

8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jul;185(1):1-4.

9. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 31;8:CD006583.

10. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):595-600.

Enterotomy can be a serious complication in abdominopelvic surgery, particularly if it is not immediately recognized and treated. Risk of visceral injury increases when complex dissection is required for treatment of cancer, resection of endometriosis, and extensive lysis of adhesions.

In a retrospective review from 1984 to 2003, investigators assessed intestinal injuries at the time of gynecologic operations. Of the 110 cases reported, about 37% occurred during the opening of the peritoneal cavity, 38% during adhesiolysis and pelvic dissection, 9% during laparoscopy, 9% during vaginal surgery, and 8% during dilation and curettage. Of the bowel injuries, more than 75% were minor.1 Mortality from unrecognized bowel injury is significant, and as such, appropriate recognition and management of these injuries is critical.2

Some basic principles are critical when surgeons face a bowel injury:

1. Recognize the extent of the injury, including the size of the breach, the depth (full or partial thickness), and the nature of the injury (thermal or cold).

2. Assess the integrity of the bowel, including adequacy of blood supply, prior bowel damage from radiation, and absence of downstream obstruction.

3. Ensure no other occult injuries exist in other segments.

4. Obtain adequate exposure and mobilization of the bowel beyond the site of injury, including the adjacent bowel. This involves releasing other adhesions so that adequate bowel length is available for a tension-free repair.

Methods of repair

The decision to employ each is influenced by multiple factors. Primary closure is best suited to small lesions (1 cm or less) that are a result of cold or sharp injury. However, thermal injury sustained via electrosurgical devices induces delayed tissue damage beyond the visible edges of the immediate defect, and surgeons should consider a resection of bowel to at least 1 cm beyond the immediately apparent injury site. Additionally, resection and re-anastamosis should also be considered if the damaged segment of bowel has poor blood supply, integrity, or the repair would result in tension along the suture/staple line or luminal narrowing.

Simple small bowel closures

Serosal abrasions need not be repaired; however, small tears of the serosa and muscularis can be managed with a single layer of interrupted 3-0 absorbable or permanent silk suture on a tapered needle. The suture line should be perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bowel at 2-mm to 3-mm intervals in order to prevent narrowing of the lumen. The suture should pass through serosal and muscular layers in an imbricating (Lembert) stitch. For smaller defects of less than 6 mm, a single layer closure is typically adequate.

Small bowel resection

Some larger defects, thermal injuries, and segments with multiple enterotomies may be best repaired with resection and re-anastamosis technique. A segment of resectable bowel is chosen such that the afferent and efferent limbs to be re-anastamosed can be reapproximated in a tension-free fashion. A mesenterotomy is made at the proximal and distal portions of the involved bowel. A gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is then inserted perpendicularly across the bowel. The remaining wedge of connected mesentery can then be efficiently excised with an electrothermal bipolar coagulator device ensuring that maximal mesentery and blood supply are preserved to the remaining limbs of intestine. The proximal and distal segments are then aligned at the antimesenteric sides.

Large bowel repair

Defects in the serosa and small lacerations can be managed with a primary closure, similar to the small intestine. For more extensive injuries that may require resection, diversion, or complicated repair, consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or general or colorectal surgeon may be indicated as colotomy repairs are associated with higher rates of breakdown and fistula. If fecal contamination is present, copious irrigation should be performed and placement of a peritoneal drain to reduce the likelihood of abscess formation should be considered. If appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for colonic surgery has not been given prior to skin incision, it should be administered once the colotomy is identified.

Standard prophylaxis for hysterectomy (such as a first-generation cephalosporin like cefazolin) is not adequate for large bowel surgery, and either metronidazole should be added or a second-generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin should be given. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin with either gentamicin or a fluoroquinolone should be administered.6

Postoperative management

The potential for postoperative morbidity must be understood for appropriate management following bowel surgery. Ileus is common and the clinician should understand how to diagnose and manage it. Additionally, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, fistula formation, and mechanical obstruction are complications that may require surgical intervention and must be vigilantly managed.

The routine use of postoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) does not hasten return of bowel function or prevent leak from sites of gastrointestinal repair. In fact, early feeding has been associated with reduced perioperative complications and earlier return of bowel function has been observed without the use of NGT.7 In general, for small and large intestinal injuries, early feeding is considered acceptable.8

Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis, beyond 24 hours, is not recommended.6

Avoiding injury

Gynecologic surgeons should adhere to surgical principles with sharp dissection for adhesions, gentle tissue handling, adequate exposure, and light retraction to prevent bowel injury or minimize their extent. Laparoscopic entry sites should be chosen based on the likelihood of abdominal adhesions. When the patient’s history predicts a high likelihood of intraperitoneal adhesions, the left upper quadrant site should be strongly considered as the entry site. The likelihood of gastrointestinal injury is not influenced by open versus closed laparoscopic entry and surgeons should use the technique with which they have the greatest experience and skill.9 However, in patients who have had prior laparotomies, there is an increased risk of periumbilical adhesions, and consideration should be made for a nonumbilical entry site.10 Methodical sharp dissection and sparing use of thermal energy should be used with adhesiolysis. When injury occurs, prompt recognition, preparation, and methodical management can mitigate the impact.

Dr. Staley is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Int Surg. 2006 Nov-Dec;91(6):336-40.

2. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Jun;192(6):677-83.

3. Doherty, G. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Surgery. Thirteenth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010.

4. Hoffman B. Williams Gynecology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2016.

5. Berek J, Hacker N. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

6. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;14(1):73-156.

7. Br J Surg. 2005 Jun;92(6):673-80.

8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jul;185(1):1-4.

9. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 31;8:CD006583.

10. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):595-600.

Management of adnexal masses in pregnancy

Roughly 1%-2% of pregnancies are complicated by an adnexal mass, and prenatal ultrasound for fetal evaluation has detected more asymptomatic ovarian masses as a result.

The differential diagnosis for adnexal mass is broad and includes follicular or corpus luteum cysts, mature teratoma, theca lutein cyst, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, cystadenoma, pedunculated leiomyoma, luteoma, as well as malignant neoplasms of epithelial, germ cell, and sex cord–stromal origin (J Ultrasound Med. 2004 Jun;23[6]:805-19). Most masses will be benign neoplasms, with a fraction identified as malignancies.

In 2013, Baser et al. performed a retrospective study of 151 women who underwent surgery of an adnexal mass at time of cesarean delivery. Of the 151 cases reviewed, 148 (98%) of the masses were benign (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;123[2]:124-6). Additionally, if the patient presents with pain, diagnoses such as ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, degenerating fibroid, and torsion should also be considered.

Diagnostic evaluation and management

The majority of adnexal masses identified in pregnancy are benign simple cysts measuring less than 5 cm in diameter. Approximately 70% of cystic masses detected in the first trimester will spontaneously resolve by the second trimester (Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;49[3]:492-505). However, for some masses, surgical resection is warranted.

Masses present after the first trimester and that are (1) greater than 10cm in diameter or (2) are solid or contain solid and cystic areas or have septated or papillary areas, are generally managed surgically as these features increase the risk of malignancy or complications such as adnexal torsion, rupture, or labor dystocia (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):315-21).

Adnexal masses without these features often resolve during pregnancy and can be expectantly managed (Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105[5 Pt 1]:1098-103). The optimal time for surgical intervention is after the first trimester as organogenesis is largely complete, therefore minimizing the risk of drug-induced teratogenesis, and any necessary cystectomy or oophorectomy will not disrupt the required progesterone production of the corpus luteum as this has been replaced by the placenta.

Preoperative assessment

For most cases, imaging with ultrasound is adequate for preoperative evaluation; however, in some cases, further imaging is needed for appropriate characterization of the mass. In this situation, further imaging with MRI is preferred as this modality has good resolution for visualization of soft tissue pathology and does not expose the patient and fetus to ionizing radiation. Of note, Gadolinium-based contrast should be avoided as effects have not been well established in pregnancy (AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Aug;191[2]:364-70).

If there is concern for malignancy during pregnancy, drawing serum tumor markers preoperatively is typically not suggested. Oncofetal antigens, including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), are elevated during gestation, making them poor markers for malignancy. If malignancy is ultimately diagnosed, then tumor markers can be obtained immediately postoperatively.

Surgical approach and prognosis

If there is low suspicion for malignancy, a laparoscopic approach is preferable and reasonable at all stages of pregnancy, although early second trimester is ideal. Entry at Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant versus the umbilicus is preferable in order to minimize risk of uterine injury.

If malignancy is suspected, maximum exposure should be obtained with a midline vertical incision. Peritoneal washings should be obtained on immediate entry of the peritoneal cavity, and the contralateral ovary should also be adequately examined along with a general abdominopelvic survey. If the mass demonstrates concerning features, such as solid features or presence of ascites, then the specimen should be sent for intraoperative frozen pathology, and the pathologist should be made aware of the concurrent pregnancy. If malignancy is confirmed on frozen pathology, a full staging procedure should be performed and a gynecologic oncologist consulted.

Roughly three-quarters of invasive ovarian cancers diagnosed in pregnancy are early stage disease, and the 5-year survival of ovarian cancers associated with pregnancy is between 72% and 90% (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 Jan-Feb;16[1]:8-15).

In a retrospective cohort study of 101 pregnant women, 31% of adnexal masses resected in pregnant women greater than 14 weeks gestation were teratomas. In total, 23% of masses were luteal cysts. Less commonly, patients were diagnosed with serous cystadenoma (14%), endometrioma (8%), mucinous cystadenoma (7%), benign cyst (6%), tumor of low malignant potential (5%), and paratubal cyst (3%).

In this study, approximately half of the women underwent minimally invasive surgery and half had surgery via laparotomy. There were more complications in the women undergoing laparotomy (ileus) and there were no differences between the groups with regards to pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Nov-Dec;18[6]:720-5).

In general, characteristics that are favorable for spontaneous resolution include masses that are simple in nature by ultrasound and less than 5 cm to 6 cm in diameter.

For women with simple-appearing masses on ultrasound, reimaging can occur during the remainder of the pregnancy at the discretion of the physician or during the postpartum period. All women should be provided with torsion and rupture precautions during the pregnancy (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;205[2]:97-102). For women with more concerning features on ultrasound, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the decision for surgical management is made, minimally invasive surgery should be strongly considered due to minimal maternal and perinatal morbidity.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Roughly 1%-2% of pregnancies are complicated by an adnexal mass, and prenatal ultrasound for fetal evaluation has detected more asymptomatic ovarian masses as a result.

The differential diagnosis for adnexal mass is broad and includes follicular or corpus luteum cysts, mature teratoma, theca lutein cyst, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, cystadenoma, pedunculated leiomyoma, luteoma, as well as malignant neoplasms of epithelial, germ cell, and sex cord–stromal origin (J Ultrasound Med. 2004 Jun;23[6]:805-19). Most masses will be benign neoplasms, with a fraction identified as malignancies.

In 2013, Baser et al. performed a retrospective study of 151 women who underwent surgery of an adnexal mass at time of cesarean delivery. Of the 151 cases reviewed, 148 (98%) of the masses were benign (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;123[2]:124-6). Additionally, if the patient presents with pain, diagnoses such as ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, degenerating fibroid, and torsion should also be considered.

Diagnostic evaluation and management

The majority of adnexal masses identified in pregnancy are benign simple cysts measuring less than 5 cm in diameter. Approximately 70% of cystic masses detected in the first trimester will spontaneously resolve by the second trimester (Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;49[3]:492-505). However, for some masses, surgical resection is warranted.

Masses present after the first trimester and that are (1) greater than 10cm in diameter or (2) are solid or contain solid and cystic areas or have septated or papillary areas, are generally managed surgically as these features increase the risk of malignancy or complications such as adnexal torsion, rupture, or labor dystocia (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):315-21).

Adnexal masses without these features often resolve during pregnancy and can be expectantly managed (Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105[5 Pt 1]:1098-103). The optimal time for surgical intervention is after the first trimester as organogenesis is largely complete, therefore minimizing the risk of drug-induced teratogenesis, and any necessary cystectomy or oophorectomy will not disrupt the required progesterone production of the corpus luteum as this has been replaced by the placenta.

Preoperative assessment

For most cases, imaging with ultrasound is adequate for preoperative evaluation; however, in some cases, further imaging is needed for appropriate characterization of the mass. In this situation, further imaging with MRI is preferred as this modality has good resolution for visualization of soft tissue pathology and does not expose the patient and fetus to ionizing radiation. Of note, Gadolinium-based contrast should be avoided as effects have not been well established in pregnancy (AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Aug;191[2]:364-70).

If there is concern for malignancy during pregnancy, drawing serum tumor markers preoperatively is typically not suggested. Oncofetal antigens, including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), are elevated during gestation, making them poor markers for malignancy. If malignancy is ultimately diagnosed, then tumor markers can be obtained immediately postoperatively.

Surgical approach and prognosis

If there is low suspicion for malignancy, a laparoscopic approach is preferable and reasonable at all stages of pregnancy, although early second trimester is ideal. Entry at Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant versus the umbilicus is preferable in order to minimize risk of uterine injury.

If malignancy is suspected, maximum exposure should be obtained with a midline vertical incision. Peritoneal washings should be obtained on immediate entry of the peritoneal cavity, and the contralateral ovary should also be adequately examined along with a general abdominopelvic survey. If the mass demonstrates concerning features, such as solid features or presence of ascites, then the specimen should be sent for intraoperative frozen pathology, and the pathologist should be made aware of the concurrent pregnancy. If malignancy is confirmed on frozen pathology, a full staging procedure should be performed and a gynecologic oncologist consulted.

Roughly three-quarters of invasive ovarian cancers diagnosed in pregnancy are early stage disease, and the 5-year survival of ovarian cancers associated with pregnancy is between 72% and 90% (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 Jan-Feb;16[1]:8-15).

In a retrospective cohort study of 101 pregnant women, 31% of adnexal masses resected in pregnant women greater than 14 weeks gestation were teratomas. In total, 23% of masses were luteal cysts. Less commonly, patients were diagnosed with serous cystadenoma (14%), endometrioma (8%), mucinous cystadenoma (7%), benign cyst (6%), tumor of low malignant potential (5%), and paratubal cyst (3%).

In this study, approximately half of the women underwent minimally invasive surgery and half had surgery via laparotomy. There were more complications in the women undergoing laparotomy (ileus) and there were no differences between the groups with regards to pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Nov-Dec;18[6]:720-5).

In general, characteristics that are favorable for spontaneous resolution include masses that are simple in nature by ultrasound and less than 5 cm to 6 cm in diameter.

For women with simple-appearing masses on ultrasound, reimaging can occur during the remainder of the pregnancy at the discretion of the physician or during the postpartum period. All women should be provided with torsion and rupture precautions during the pregnancy (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;205[2]:97-102). For women with more concerning features on ultrasound, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the decision for surgical management is made, minimally invasive surgery should be strongly considered due to minimal maternal and perinatal morbidity.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Roughly 1%-2% of pregnancies are complicated by an adnexal mass, and prenatal ultrasound for fetal evaluation has detected more asymptomatic ovarian masses as a result.

The differential diagnosis for adnexal mass is broad and includes follicular or corpus luteum cysts, mature teratoma, theca lutein cyst, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, cystadenoma, pedunculated leiomyoma, luteoma, as well as malignant neoplasms of epithelial, germ cell, and sex cord–stromal origin (J Ultrasound Med. 2004 Jun;23[6]:805-19). Most masses will be benign neoplasms, with a fraction identified as malignancies.

In 2013, Baser et al. performed a retrospective study of 151 women who underwent surgery of an adnexal mass at time of cesarean delivery. Of the 151 cases reviewed, 148 (98%) of the masses were benign (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;123[2]:124-6). Additionally, if the patient presents with pain, diagnoses such as ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, degenerating fibroid, and torsion should also be considered.

Diagnostic evaluation and management

The majority of adnexal masses identified in pregnancy are benign simple cysts measuring less than 5 cm in diameter. Approximately 70% of cystic masses detected in the first trimester will spontaneously resolve by the second trimester (Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;49[3]:492-505). However, for some masses, surgical resection is warranted.

Masses present after the first trimester and that are (1) greater than 10cm in diameter or (2) are solid or contain solid and cystic areas or have septated or papillary areas, are generally managed surgically as these features increase the risk of malignancy or complications such as adnexal torsion, rupture, or labor dystocia (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):315-21).

Adnexal masses without these features often resolve during pregnancy and can be expectantly managed (Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105[5 Pt 1]:1098-103). The optimal time for surgical intervention is after the first trimester as organogenesis is largely complete, therefore minimizing the risk of drug-induced teratogenesis, and any necessary cystectomy or oophorectomy will not disrupt the required progesterone production of the corpus luteum as this has been replaced by the placenta.

Preoperative assessment

For most cases, imaging with ultrasound is adequate for preoperative evaluation; however, in some cases, further imaging is needed for appropriate characterization of the mass. In this situation, further imaging with MRI is preferred as this modality has good resolution for visualization of soft tissue pathology and does not expose the patient and fetus to ionizing radiation. Of note, Gadolinium-based contrast should be avoided as effects have not been well established in pregnancy (AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Aug;191[2]:364-70).

If there is concern for malignancy during pregnancy, drawing serum tumor markers preoperatively is typically not suggested. Oncofetal antigens, including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), are elevated during gestation, making them poor markers for malignancy. If malignancy is ultimately diagnosed, then tumor markers can be obtained immediately postoperatively.

Surgical approach and prognosis

If there is low suspicion for malignancy, a laparoscopic approach is preferable and reasonable at all stages of pregnancy, although early second trimester is ideal. Entry at Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant versus the umbilicus is preferable in order to minimize risk of uterine injury.

If malignancy is suspected, maximum exposure should be obtained with a midline vertical incision. Peritoneal washings should be obtained on immediate entry of the peritoneal cavity, and the contralateral ovary should also be adequately examined along with a general abdominopelvic survey. If the mass demonstrates concerning features, such as solid features or presence of ascites, then the specimen should be sent for intraoperative frozen pathology, and the pathologist should be made aware of the concurrent pregnancy. If malignancy is confirmed on frozen pathology, a full staging procedure should be performed and a gynecologic oncologist consulted.

Roughly three-quarters of invasive ovarian cancers diagnosed in pregnancy are early stage disease, and the 5-year survival of ovarian cancers associated with pregnancy is between 72% and 90% (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 Jan-Feb;16[1]:8-15).

In a retrospective cohort study of 101 pregnant women, 31% of adnexal masses resected in pregnant women greater than 14 weeks gestation were teratomas. In total, 23% of masses were luteal cysts. Less commonly, patients were diagnosed with serous cystadenoma (14%), endometrioma (8%), mucinous cystadenoma (7%), benign cyst (6%), tumor of low malignant potential (5%), and paratubal cyst (3%).

In this study, approximately half of the women underwent minimally invasive surgery and half had surgery via laparotomy. There were more complications in the women undergoing laparotomy (ileus) and there were no differences between the groups with regards to pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Nov-Dec;18[6]:720-5).

In general, characteristics that are favorable for spontaneous resolution include masses that are simple in nature by ultrasound and less than 5 cm to 6 cm in diameter.

For women with simple-appearing masses on ultrasound, reimaging can occur during the remainder of the pregnancy at the discretion of the physician or during the postpartum period. All women should be provided with torsion and rupture precautions during the pregnancy (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;205[2]:97-102). For women with more concerning features on ultrasound, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the decision for surgical management is made, minimally invasive surgery should be strongly considered due to minimal maternal and perinatal morbidity.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Managing menopause symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

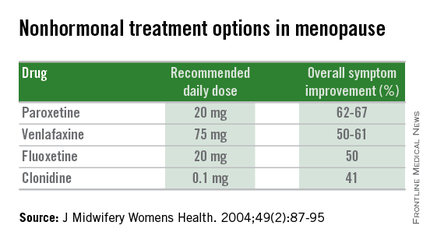

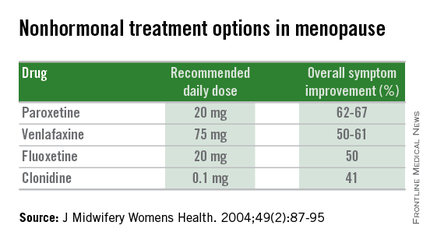

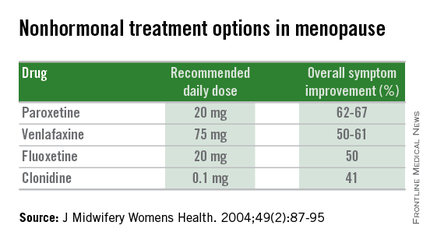

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Due to advancements in surgical treatment, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, gynecologic cancer survival rates are continuing to improve and quality of life is evolving into an even more significant focus in cancer care.

Roughly 30%-40% of all women with a gynecologic malignancy will experience climacteric symptoms and menopause prior to the anticipated time of natural menopause (J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27[8]:1214-9). Cessation of ovarian estrogen and progesterone production can result in short-term as well as long-term sequelae, including vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, osteoporosis, and mood disturbances. Iatrogenic menopause after cancer treatment can be more sudden and severe when compared with the natural course of physiologic menopause. As a result, determination of safe, effective modalities for treating these symptoms is of particular importance for survivor quality of life.

Both combination and estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HT) provide greater improvement in these specific symptoms and overall quality of life than placebo as demonstrated in several observational and randomized control trials (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;[2]:CD004143).

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy, with approximately 54,000 new cases anticipated in the United States in 2015. Twenty-five percent of these new cases will be in premenopausal women, and with an ever-increasing obesity rate, this number may continue to climb.

Women with early-stage Type 1 endometrial cancer who have vasomotor symptoms after surgery may be offered a short course of estrogen-based HT at the lowest effective dose following hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging procedure (J Clin Oncol. 2006 Feb 1;24[4]:587-92). For women with genitourinary symptoms, vaginal moisturizers and/or low-dose vaginal estrogen are reasonable options. Unfortunately, there are no data to guide the use of estrogen replacement therapy in women with Type 2 endometrial cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54).

Ovarian cancer

There is minimal data implicating a hormonal causation to ovarian carcinogenesis. Most women with epithelial ovarian cancer do not express tumor estrogen or progesterone receptors. Treatment will result in abrupt, iatrogenic menopause, raising the question of whether it is safe to use HT in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Multiple studies have failed to demonstrate a difference in 5-year survival rates in women with epithelial cancer using HT for 2 years or less (JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302[3]:298-305, Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21[2]:192-6, Cancer. 1999 Sep 15;86[6]:1013-8). As such, symptomatic patients could be offered a course of HT; however, caution should be exercised in women with estrogen/progesterone–expressing tumors or nonepithelial tumors. As with endometrial cancer patients, the lowest effective doses should be prescribed.

Cervical cancer

Most cervical squamous and adenocarcinomas are not hormone dependent. For women with early-stage squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian conservation may be possible or oophoropexy may be offered. However, for many patients, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy is more common, and the local effect of radiation therapy can result in vaginal atrophy with subsequent dyspareunia or ovarian failure from radiation scatter. Even for patients who undergo oophoropexy, radiation scatter may still result in ovarian failure. In a few observational studies, there are no data to infer that cervical cancer is hormonally related or that survival rates are decreased.

Currently, HT use in cervical cancer survivors is considered safe. Of note, for women with more advanced-stage cervical cancer and who received chemoradiation for primary treatment, combination therapy with estrogen and progesterone may be more appropriate if the uterus remains in situ. However, for women who have undergone hysterectomy, combination therapy with progesterone may not be warranted and estrogen alone (orally or vaginally) is acceptable (Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Aug;122[2]:447-54)

Nonhormonal therapies

Women presenting with menopausal symptoms in whom estrogen therapy is contraindicated or not desired can also consider using nonhormonal therapies as an alternative. These include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine. Albeit not as effective as HT, these alternative therapies are reasonable options, particularly for management of vasomotor symptoms.

From a limited number of observational studies and a few randomized trials, short-term hormone replacement therapy does not present increased risk to survivors of gynecologic cancers. Additionally, patients have the added option of using nonhormonal therapies, which may provide some benefit. The decision to institute HT should occur after a thorough discussion of the potential to optimize symptom control and the theoretical risk of stimulating quiescent malignant disease.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Managing menopausal symptoms after risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy

Compared to the general population, women with mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes have a significantly higher lifetime risk of ovarian and breast cancers (Science. 2003 Oct 24;302[5645]:643-6). Since the occurrence of ovarian and breast cancer in BRCA carriers is often prior to menopause, and because we have no screening test to detect early stage ovarian cancer, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy has been recommended around age 40.

It has been shown that risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy significantly reduces ovarian cancer risk by 85%-95% in BRCA-affected women. Also, this surgery can reduce breast cancer risk by 53%-68% (N Engl J Med. 2002 May 23;346[21]:1609-15). The 2008 Practice Bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations after the completion of childbearing or age 40 (Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jan;111[1]:231-41).

Health implications

Nearly 60% of women who have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation will elect to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy between the ages of 35 and 40 years (Open Med. 2007 Aug 13;1[2]:e92-8). As such, surgical menopause can result in hot flashes, vaginal dryness, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and cognitive changes, which may significantly impact a woman’s quality of life. In addition, increased risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis following bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may have a significant impact on a woman’s health.

Since these women undergo surgical menopause as opposed to natural menopause, they have an abrupt loss in hormones, and due to their younger age at the time of surgery, they may also have a longer exposure period to the detrimental effects of hypoestrogenism.

Symptom management

Various treatment options exist for relief of menopausal symptoms, including nonhormonal therapies and hormone replacement therapies (HT).

Nonhormonal therapies include serotonin receptor inhibitors (venlafaxine and paroxetine) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (clonidine), which are most appropriate for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Unfortunately, these options have proved to be as effective as HT. Also, women should be adequately counseled regarding the various side effects of these nonhormonal medications. Alternative approaches such as phytoestrogens are unproven and are still undergoing investigation. As such, HT remains the standard for treatment of menopausal symptoms, and many trials have confirmed that HT can effectively treat menopausal symptoms following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

This then raises the question of safety regarding use of HT in this patient population; especially the possibility of increased risk of breast cancer. Interestingly, only 10%-25% of BRCA1 carriers will have estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, while 65%-79% of BRCA2-associated breast cancers will be positive for the receptor (Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Mar 15;10[6]:2029-34).

Unfortunately, we do not have adequate trials or studies with sufficient long-term follow-up to validate whether HT increases the risk of breast cancer or recurrence. However, the PROSE Study Group did report on a prospective cohort of 462 women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. In this study, HT did not alter the reduction in breast cancer risk from risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (J Clin Oncol. 2005 Nov 1;23[31]:7804-10). In addition to a paucity of data regarding systemic HT, there is little data in the BRCA-positive population to confirm the safety of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy (J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 15;22[6]:1045-54).

Understanding the options

Use of HT in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations requires further investigation. There should be shared decision making between the patient and provider when counseling on the management of menopausal symptoms following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Most importantly, women should understand the options of nonhormonal therapies and their specific side effects. They should also understand the lack of significant data regarding use of systemic HT, and that if use is elected, there may be an increased risk of breast cancer.

Women who do elect to use systemic HT following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy have options that can help reduce the risk of HT-associated breast cancer, including a shorter duration of systemic HT or concurrent hysterectomy to allow for estrogen-only HT, which has a decreased risk of breast cancer compared with combined therapies that include progestins. These women may also be considering prophylactic mastectomy, which would change the concerns regarding HT and an increased risk of breast cancer.

Increased awareness of these options among physicians and patients alike can help to decrease unsatisfactory symptoms and improve quality of life in women undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

Compared to the general population, women with mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes have a significantly higher lifetime risk of ovarian and breast cancers (Science. 2003 Oct 24;302[5645]:643-6). Since the occurrence of ovarian and breast cancer in BRCA carriers is often prior to menopause, and because we have no screening test to detect early stage ovarian cancer, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy has been recommended around age 40.

It has been shown that risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy significantly reduces ovarian cancer risk by 85%-95% in BRCA-affected women. Also, this surgery can reduce breast cancer risk by 53%-68% (N Engl J Med. 2002 May 23;346[21]:1609-15). The 2008 Practice Bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations after the completion of childbearing or age 40 (Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jan;111[1]:231-41).

Health implications

Nearly 60% of women who have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation will elect to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy between the ages of 35 and 40 years (Open Med. 2007 Aug 13;1[2]:e92-8). As such, surgical menopause can result in hot flashes, vaginal dryness, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and cognitive changes, which may significantly impact a woman’s quality of life. In addition, increased risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis following bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may have a significant impact on a woman’s health.

Since these women undergo surgical menopause as opposed to natural menopause, they have an abrupt loss in hormones, and due to their younger age at the time of surgery, they may also have a longer exposure period to the detrimental effects of hypoestrogenism.

Symptom management

Various treatment options exist for relief of menopausal symptoms, including nonhormonal therapies and hormone replacement therapies (HT).

Nonhormonal therapies include serotonin receptor inhibitors (venlafaxine and paroxetine) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (clonidine), which are most appropriate for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Unfortunately, these options have proved to be as effective as HT. Also, women should be adequately counseled regarding the various side effects of these nonhormonal medications. Alternative approaches such as phytoestrogens are unproven and are still undergoing investigation. As such, HT remains the standard for treatment of menopausal symptoms, and many trials have confirmed that HT can effectively treat menopausal symptoms following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

This then raises the question of safety regarding use of HT in this patient population; especially the possibility of increased risk of breast cancer. Interestingly, only 10%-25% of BRCA1 carriers will have estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, while 65%-79% of BRCA2-associated breast cancers will be positive for the receptor (Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Mar 15;10[6]:2029-34).

Unfortunately, we do not have adequate trials or studies with sufficient long-term follow-up to validate whether HT increases the risk of breast cancer or recurrence. However, the PROSE Study Group did report on a prospective cohort of 462 women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. In this study, HT did not alter the reduction in breast cancer risk from risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (J Clin Oncol. 2005 Nov 1;23[31]:7804-10). In addition to a paucity of data regarding systemic HT, there is little data in the BRCA-positive population to confirm the safety of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy (J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 15;22[6]:1045-54).

Understanding the options

Use of HT in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations requires further investigation. There should be shared decision making between the patient and provider when counseling on the management of menopausal symptoms following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Most importantly, women should understand the options of nonhormonal therapies and their specific side effects. They should also understand the lack of significant data regarding use of systemic HT, and that if use is elected, there may be an increased risk of breast cancer.

Women who do elect to use systemic HT following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy have options that can help reduce the risk of HT-associated breast cancer, including a shorter duration of systemic HT or concurrent hysterectomy to allow for estrogen-only HT, which has a decreased risk of breast cancer compared with combined therapies that include progestins. These women may also be considering prophylactic mastectomy, which would change the concerns regarding HT and an increased risk of breast cancer.

Increased awareness of these options among physicians and patients alike can help to decrease unsatisfactory symptoms and improve quality of life in women undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].

Compared to the general population, women with mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes have a significantly higher lifetime risk of ovarian and breast cancers (Science. 2003 Oct 24;302[5645]:643-6). Since the occurrence of ovarian and breast cancer in BRCA carriers is often prior to menopause, and because we have no screening test to detect early stage ovarian cancer, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy has been recommended around age 40.

It has been shown that risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy significantly reduces ovarian cancer risk by 85%-95% in BRCA-affected women. Also, this surgery can reduce breast cancer risk by 53%-68% (N Engl J Med. 2002 May 23;346[21]:1609-15). The 2008 Practice Bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy should be performed in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations after the completion of childbearing or age 40 (Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jan;111[1]:231-41).

Health implications

Nearly 60% of women who have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation will elect to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy between the ages of 35 and 40 years (Open Med. 2007 Aug 13;1[2]:e92-8). As such, surgical menopause can result in hot flashes, vaginal dryness, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbances, and cognitive changes, which may significantly impact a woman’s quality of life. In addition, increased risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis following bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may have a significant impact on a woman’s health.

Since these women undergo surgical menopause as opposed to natural menopause, they have an abrupt loss in hormones, and due to their younger age at the time of surgery, they may also have a longer exposure period to the detrimental effects of hypoestrogenism.

Symptom management

Various treatment options exist for relief of menopausal symptoms, including nonhormonal therapies and hormone replacement therapies (HT).

Nonhormonal therapies include serotonin receptor inhibitors (venlafaxine and paroxetine) and alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (clonidine), which are most appropriate for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Unfortunately, these options have proved to be as effective as HT. Also, women should be adequately counseled regarding the various side effects of these nonhormonal medications. Alternative approaches such as phytoestrogens are unproven and are still undergoing investigation. As such, HT remains the standard for treatment of menopausal symptoms, and many trials have confirmed that HT can effectively treat menopausal symptoms following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

This then raises the question of safety regarding use of HT in this patient population; especially the possibility of increased risk of breast cancer. Interestingly, only 10%-25% of BRCA1 carriers will have estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, while 65%-79% of BRCA2-associated breast cancers will be positive for the receptor (Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Mar 15;10[6]:2029-34).

Unfortunately, we do not have adequate trials or studies with sufficient long-term follow-up to validate whether HT increases the risk of breast cancer or recurrence. However, the PROSE Study Group did report on a prospective cohort of 462 women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. In this study, HT did not alter the reduction in breast cancer risk from risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (J Clin Oncol. 2005 Nov 1;23[31]:7804-10). In addition to a paucity of data regarding systemic HT, there is little data in the BRCA-positive population to confirm the safety of local vaginal estrogen for treatment of vaginal atrophy (J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar 15;22[6]:1045-54).

Understanding the options

Use of HT in women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations requires further investigation. There should be shared decision making between the patient and provider when counseling on the management of menopausal symptoms following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Most importantly, women should understand the options of nonhormonal therapies and their specific side effects. They should also understand the lack of significant data regarding use of systemic HT, and that if use is elected, there may be an increased risk of breast cancer.

Women who do elect to use systemic HT following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy have options that can help reduce the risk of HT-associated breast cancer, including a shorter duration of systemic HT or concurrent hysterectomy to allow for estrogen-only HT, which has a decreased risk of breast cancer compared with combined therapies that include progestins. These women may also be considering prophylactic mastectomy, which would change the concerns regarding HT and an increased risk of breast cancer.

Increased awareness of these options among physicians and patients alike can help to decrease unsatisfactory symptoms and improve quality of life in women undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at [email protected].