User login

Tips for avoiding nerve injuries in gynecologic surgery

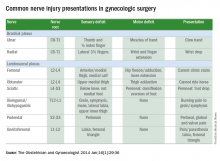

Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at [email protected].

Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at [email protected].

Upper- and lower-extremity injuries can occur during gynecologic surgery. The incidence of lower-extremity injury is 1.1%-1.9% and upper-extremity injuries can occur in 0.16% of cases.1-5 Fortunately, most of the injuries are transient, sensory injuries that resolve spontaneously. However, a small percentage of injuries result in long-term sequelae.

The pathophysiology of the nerve injuries can be mechanistically separated into three categories: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neuropraxia results from nerve demyelination at the site of injury because of compression and typically resolves within weeks to months as the nerve is remyelinated. Axonotmesis results from severe compression with axon damage. This may take up to a year to resolve as axonal regeneration proceeds at the rate of 1 mm per day. This can be separated into second and third degree and refers to the severity of damage and the resultant persistent deficit. Neurotmesis results from complete transection and is associated with a poor prognosis without reparative surgery.

Brachial plexus

Stretch injury is the most common reason for a brachial plexus injury. This can occur if the arm board is extended to greater than 90 degrees from the patient’s torso or if the patient’s arm falls off of the arm board. Careful positioning and securing the patient’s arm on the arm board before draping can avoid this injury. A brachial plexus injury can also occur if shoulder braces are placed too laterally during minimally invasive surgery. Radial nerve injuries can occur if there is too much pressure on the humerus during positioning. Ulnar injuries arise from pressure placed on the medial aspect of the elbow.

Tip #1: When tucking a patient’s arm for minimally invasive surgery, appropriate padding should be placed around the elbow and wrist, and the arm should be in the “thumbs-up” position.

Tip #2: Shoulder blocks should be placed over the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Lumbosacral plexus

The femoral nerve is the nerve most commonly injured during gynecologic surgery and this usually occurs because of compression of the nerve from the lateral blades of self-retaining retractors. One study showed an 8% incidence of injury from self-retaining retractors, compared with less than 1% when the retractors were not used.6 The femoral nerve can also be stretched when patients are placed in the lithotomy position and the hip is hyperflexed.

As with brachial injury prevention, patients should be positioned prior to draping and care must be taken to not hyperflex or externally rotate the hip during minimally invasive surgical procedures. With the introduction of robot-assisted surgery, care must be taken when docking the robot and surgeons must resist excessive movement of the stirrups.

Tip #3: During laparotomy, surgeons should use the shortest blades that allow for adequate visualization and check the blades during the procedure to ensure that excessive pressure is not placed on the psoas muscle. Consider intermittently releasing the pressure on the lateral blades during other portions of the procedure.

Tip #4: Make sure the stirrups are at the same height and that the leg is in line with the patient’s contralateral shoulder.

Obturator nerve injuries can occur during retroperitoneal dissection for pelvic lymphadenectomy (obturator nodes) and can be either a transection or a cautery injury. It can also be injured during urogynecologic procedures including paravaginal defect repairs and during the placement of transobturator tapes.

The sciatic nerve and its branch, the common peroneal, are generally injured because of excessive stretch or pressure. Both nerves can be injured from hyperflexion of the thigh and the common peroneal can suffer a pressure injury as it courses around the lateral head of the fibula. Therefore, care during lithotomy positioning with both candy cane and Allen stirrups is critical during vaginal surgery.

Tip #5: Ensure that the lateral fibula is not touching the stirrup or that padding is placed between the fibular head and the stirrup.

The ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves are typically injured via suture entrapment from low transverse skin incisions, though laparoscopic injury has also been reported. The incidence after a Pfannenstiel incision is about 3.7%.7

Tip #6: Avoid extending the low transverse incision beyond the lateral margin of the rectus muscle, and do not extend the fascial closure suture more than 1.5 cm from the lateral edge of the fascial incision to avoid catching the nerve with the suture.

The pudendal nerve is most commonly injured during vaginal procedures such as sacrospinous fixation. Pain is typically worse when seated.

The genitofemoral nerve is typically injured during retroperitoneal lymph node dissection, particularly the external iliac nodes. The nerve is small and runs lateral to the external iliac artery. It can suffer cautery and transection injuries. Usually, the paresthesias over the mons pubis, labia majora, and medial inner thigh are temporary.

Tip #7: Care should be taken to identify and spare the nerve during retroperitoneal dissection or external iliac node removal.

Nerve injuries during gynecologic surgery are common and are a significant cause of potential morbidity. While occasionally unavoidable and inherent to the surgical procedure, many times the injury could be prevented with proper attention and care to patient positioning and retractor use. Gynecologists should be aware of the risks and have a through understanding of the anatomy. However, should an injury occur, the patient can be reassured that most are self-limited and full recovery is generally expected. In a prospective study, the median time to resolution of symptoms was 31.5 days (range, 1 day to 6 months).5

References

1. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2014;16:29-36.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 1988 Nov;31(3):462-6.

3. Fertil Steril. 1993 Oct;60(4):729-32.

4. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007 Sep-Oct;14(5):664-72.

5. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov;201(5):531.e1-7.

6. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1985 Dec;20(6):385-92.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Apr;111(4):839-46.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email her at [email protected].

Enhanced recovery pathways in gynecology

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

The role of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer, Part 1

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers present at an early stage with excellent overall survival – approximately 85% – in clinical stage I disease. Since 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer has required surgical staging reflecting increasing data on the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and the treatment implications for node positive cancers.

Indeed, lymph nodes represent the most common location for extrauterine spread in endometrial cancer. The lymphatic drainage from the uterus is to both the pelvic and the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lymphatic channels from the uterus can drain directly from the fundus via the infundibulopelvic ligament to the aortic lymph node chain, thereby bypassing the pelvic lymph nodes. As a result, there is a 2%-3% risk of isolated aortic metastasis with negative pelvic lymph nodes.

The extent of lymph node evaluation required for staging is debatable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend complete hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional procedures based on preoperative and intraoperative findings. During surgery, the surgeon should evaluate all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal lymphatic chains for abnormalities. All suspicious lymph nodes should be removed, but the extent of lymphadenectomy should be based on the NCCN guidelines.1 The NCCN offers the option for use of sentinel lymph node evaluation with adherence to specific staging algorithms for this technology.

Proponents of lymphadenectomy cite the need for accurate staging to guide adjuvant therapies, to provide prognostic information, and to eradicate metastatic lymph nodes with possible therapeutic benefit. However, criticisms of lymphadenectomy include a lack of randomized studies demonstrating a therapeutic benefit and the morbidity of lymphedema with its corresponding quality of life and cost implications. As a result, practices regarding lymph node evaluation vary widely.

There is conflicting data on whether there is a therapeutic benefit to performing lymphadenectomy. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit, but this was not seen in two prospective trials. There appears to be clear benefit for debulking of clinically enlarged nodal metastasis,2,3 and likely benefit to resection of microscopic metastasis, particularly with combined pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.4,5,6,7,8

The ASTEC trial by Kitchener et al and an Italian collaborative trial by Benedetti et al, however, both evaluated the role of lymph node dissection in predominantly low-risk endometrial cancer and found no benefit.9,10 Both studies documented no difference in overall survival, but increased morbidity with lymphadenectomy. No prospective trials have evaluated the role of lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.

Universal use of complete lymphadenectomy in all patients with endometrial cancer would subject a large percent of low risk patients to undo surgical risk. The two most commonly utilized strategies are risk factor based lymphadenectomy and sentinel lymph node evaluation.

Tumors are considered low risk if they are less than 2cm in size, grade 1 or 2, and superficially invasive (less than 50% myometrial invasion).11 The risk of lymph node metastasis in these patients was exceedingly low with no lymph node metastasis detect in more than 400 women who prospectively underwent this evaluation, thus lymphadenectomy can be safely avoided. Utilizing risk factor based lymphadenectomy does require the availability of reliable frozen section pathology evaluation, which may be a limitation for some institutions.

A key argument against routine use of systematic lymphadenectomy is the concern for postoperative complications and lymphedema. The estimated incidence of lymphedema following lymphadenectomy is 20%-30%.12 However, there are challenges in studying lymphedema that likely limit our understanding of the true incidence. The ASTEC trial and Italian cooperative trial have demonstrated that there is an eight-fold increased risk of lymphedema in women who undergo lymphadenectomy, compared with those who do not.13 The development of lymphedema requires ongoing treatment with associated costs of care. Thus, the selective lymphadenectomy or sentinel nodes have the ability to reduce healthcare costs.14 Sentinel lymph nodes will be covered in Part Two of this article.

References

1. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Feb;12(2):248-80.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Dec;99(3):689-95.

3. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003 Sep-Oct;13(5):664-72.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Jan;56(1):29-33.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):3668-75.

6. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1165-72.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 1998 Dec;71(3):340-3.

8. Cancer. 2006 Oct 15;107(8):1823-30.

9. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

10. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Apr;109(1):11-8.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;124(2 Pt 1):307-15.

13. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 21;(9):CD007585.

14. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):518-24.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers present at an early stage with excellent overall survival – approximately 85% – in clinical stage I disease. Since 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer has required surgical staging reflecting increasing data on the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and the treatment implications for node positive cancers.

Indeed, lymph nodes represent the most common location for extrauterine spread in endometrial cancer. The lymphatic drainage from the uterus is to both the pelvic and the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lymphatic channels from the uterus can drain directly from the fundus via the infundibulopelvic ligament to the aortic lymph node chain, thereby bypassing the pelvic lymph nodes. As a result, there is a 2%-3% risk of isolated aortic metastasis with negative pelvic lymph nodes.

The extent of lymph node evaluation required for staging is debatable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend complete hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional procedures based on preoperative and intraoperative findings. During surgery, the surgeon should evaluate all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal lymphatic chains for abnormalities. All suspicious lymph nodes should be removed, but the extent of lymphadenectomy should be based on the NCCN guidelines.1 The NCCN offers the option for use of sentinel lymph node evaluation with adherence to specific staging algorithms for this technology.

Proponents of lymphadenectomy cite the need for accurate staging to guide adjuvant therapies, to provide prognostic information, and to eradicate metastatic lymph nodes with possible therapeutic benefit. However, criticisms of lymphadenectomy include a lack of randomized studies demonstrating a therapeutic benefit and the morbidity of lymphedema with its corresponding quality of life and cost implications. As a result, practices regarding lymph node evaluation vary widely.

There is conflicting data on whether there is a therapeutic benefit to performing lymphadenectomy. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit, but this was not seen in two prospective trials. There appears to be clear benefit for debulking of clinically enlarged nodal metastasis,2,3 and likely benefit to resection of microscopic metastasis, particularly with combined pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.4,5,6,7,8

The ASTEC trial by Kitchener et al and an Italian collaborative trial by Benedetti et al, however, both evaluated the role of lymph node dissection in predominantly low-risk endometrial cancer and found no benefit.9,10 Both studies documented no difference in overall survival, but increased morbidity with lymphadenectomy. No prospective trials have evaluated the role of lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.

Universal use of complete lymphadenectomy in all patients with endometrial cancer would subject a large percent of low risk patients to undo surgical risk. The two most commonly utilized strategies are risk factor based lymphadenectomy and sentinel lymph node evaluation.

Tumors are considered low risk if they are less than 2cm in size, grade 1 or 2, and superficially invasive (less than 50% myometrial invasion).11 The risk of lymph node metastasis in these patients was exceedingly low with no lymph node metastasis detect in more than 400 women who prospectively underwent this evaluation, thus lymphadenectomy can be safely avoided. Utilizing risk factor based lymphadenectomy does require the availability of reliable frozen section pathology evaluation, which may be a limitation for some institutions.

A key argument against routine use of systematic lymphadenectomy is the concern for postoperative complications and lymphedema. The estimated incidence of lymphedema following lymphadenectomy is 20%-30%.12 However, there are challenges in studying lymphedema that likely limit our understanding of the true incidence. The ASTEC trial and Italian cooperative trial have demonstrated that there is an eight-fold increased risk of lymphedema in women who undergo lymphadenectomy, compared with those who do not.13 The development of lymphedema requires ongoing treatment with associated costs of care. Thus, the selective lymphadenectomy or sentinel nodes have the ability to reduce healthcare costs.14 Sentinel lymph nodes will be covered in Part Two of this article.

References

1. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Feb;12(2):248-80.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Dec;99(3):689-95.

3. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003 Sep-Oct;13(5):664-72.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Jan;56(1):29-33.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):3668-75.

6. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1165-72.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 1998 Dec;71(3):340-3.

8. Cancer. 2006 Oct 15;107(8):1823-30.

9. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

10. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Apr;109(1):11-8.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;124(2 Pt 1):307-15.

13. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 21;(9):CD007585.

14. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):518-24.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States. Fortunately, most endometrial cancers present at an early stage with excellent overall survival – approximately 85% – in clinical stage I disease. Since 1988, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of endometrial cancer has required surgical staging reflecting increasing data on the prognostic significance of lymph node metastasis and the treatment implications for node positive cancers.

Indeed, lymph nodes represent the most common location for extrauterine spread in endometrial cancer. The lymphatic drainage from the uterus is to both the pelvic and the para-aortic lymph nodes. Lymphatic channels from the uterus can drain directly from the fundus via the infundibulopelvic ligament to the aortic lymph node chain, thereby bypassing the pelvic lymph nodes. As a result, there is a 2%-3% risk of isolated aortic metastasis with negative pelvic lymph nodes.

The extent of lymph node evaluation required for staging is debatable. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend complete hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and additional procedures based on preoperative and intraoperative findings. During surgery, the surgeon should evaluate all peritoneal surfaces and the retroperitoneal lymphatic chains for abnormalities. All suspicious lymph nodes should be removed, but the extent of lymphadenectomy should be based on the NCCN guidelines.1 The NCCN offers the option for use of sentinel lymph node evaluation with adherence to specific staging algorithms for this technology.

Proponents of lymphadenectomy cite the need for accurate staging to guide adjuvant therapies, to provide prognostic information, and to eradicate metastatic lymph nodes with possible therapeutic benefit. However, criticisms of lymphadenectomy include a lack of randomized studies demonstrating a therapeutic benefit and the morbidity of lymphedema with its corresponding quality of life and cost implications. As a result, practices regarding lymph node evaluation vary widely.

There is conflicting data on whether there is a therapeutic benefit to performing lymphadenectomy. Retrospective studies have shown a benefit, but this was not seen in two prospective trials. There appears to be clear benefit for debulking of clinically enlarged nodal metastasis,2,3 and likely benefit to resection of microscopic metastasis, particularly with combined pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.4,5,6,7,8

The ASTEC trial by Kitchener et al and an Italian collaborative trial by Benedetti et al, however, both evaluated the role of lymph node dissection in predominantly low-risk endometrial cancer and found no benefit.9,10 Both studies documented no difference in overall survival, but increased morbidity with lymphadenectomy. No prospective trials have evaluated the role of lymphadenectomy in high-risk endometrial cancers.

Universal use of complete lymphadenectomy in all patients with endometrial cancer would subject a large percent of low risk patients to undo surgical risk. The two most commonly utilized strategies are risk factor based lymphadenectomy and sentinel lymph node evaluation.

Tumors are considered low risk if they are less than 2cm in size, grade 1 or 2, and superficially invasive (less than 50% myometrial invasion).11 The risk of lymph node metastasis in these patients was exceedingly low with no lymph node metastasis detect in more than 400 women who prospectively underwent this evaluation, thus lymphadenectomy can be safely avoided. Utilizing risk factor based lymphadenectomy does require the availability of reliable frozen section pathology evaluation, which may be a limitation for some institutions.

A key argument against routine use of systematic lymphadenectomy is the concern for postoperative complications and lymphedema. The estimated incidence of lymphedema following lymphadenectomy is 20%-30%.12 However, there are challenges in studying lymphedema that likely limit our understanding of the true incidence. The ASTEC trial and Italian cooperative trial have demonstrated that there is an eight-fold increased risk of lymphedema in women who undergo lymphadenectomy, compared with those who do not.13 The development of lymphedema requires ongoing treatment with associated costs of care. Thus, the selective lymphadenectomy or sentinel nodes have the ability to reduce healthcare costs.14 Sentinel lymph nodes will be covered in Part Two of this article.

References

1. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014 Feb;12(2):248-80.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Dec;99(3):689-95.

3. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003 Sep-Oct;13(5):664-72.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Jan;56(1):29-33.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 1;23(16):3668-75.

6. Lancet. 2010 Apr 3;375(9721):1165-72.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 1998 Dec;71(3):340-3.

8. Cancer. 2006 Oct 15;107(8):1823-30.

9. Lancet. 2009 Jan 10;373(9658):125-36.

10. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Dec 3;100(23):1707-16.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Apr;109(1):11-8.

12. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Aug;124(2 Pt 1):307-15.

13. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Sep 21;(9):CD007585.

14. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Dec;135(3):518-24.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Clark is a fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at [email protected].

Recognizing granulosa cell ovarian tumors

Granulosa cell tumors arise from ovarian sex cords and make up an estimated 1% of all ovarian cancer cases but comprise more than 70% of all sex cord stromal tumors.

Granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) can be divided into adult and juvenile types. Adult GCTs are much more common, representing 95% of all GCTs. Women diagnosed with adult GCTs are typically younger as compared with those with epithelial ovarian cancer. The average age of diagnosis for adult GCTs is 50 years, and for women with juvenile GCTs, the average age at diagnosis is 20 years.

Granulosa cell tumors have been shown to be more common in nonwhite women, those with a high body mass index, and a family history of breast or ovarian cancer.1

Adult GCTs can be associated with Peutz-Jeghers and Potter syndromes. Juvenile GCTs are exceedingly rare but can also be associated with mesodermal dysplastic syndromes characterized by the presence of enchondromatosis and hemangioma formation, such as Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome.

Adult granulosa cell tumors are large, hormonally active tumors; typically secreting estrogen and associated with symptoms of hyperestrogenism. In one study, 55% of women with GCTs were reported to have hyperestrogenic findings such as breast tenderness, virulism, abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding, and hyperplasia, and those with juvenile GCTs may present with precocious puberty.2,3

In pregnancy, hormonal symptoms are temporized, thus the most common presentation is acute rupture. Initial evaluation of women with adult GCTs will reveal a palpable unilateral pelvic mass typically larger than 10cm. Juvenile and adult GCTs are unilateral in 95% of cases.4

In women presenting with a large adnexal mass, the appropriate initial clinical evaluation includes radiographic and laboratory studies. Endovaginal ultrasound typically reveals a large adnexal mass with heterogeneous solid and cystic components, areas of hemorrhage or necrosis and increased vascularity on Doppler. Juvenile GCTs have a more distinct appearance of solid growth with focal areas of follicular formation.

Laboratory findings suggestive of GCT include elevated inhibin-A, inhibin-B, anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), and CA-125. Inhibin-B is the most commonly used tumor marker for the clinical monitoring of adult GCTs, but AMH may be the most specific.5 Lastly, an endometrial biopsy should be considered in all patients with abnormal uterine bleeding and in all postmenopausal women with an adnexal mass and an endometrial stripe greater than 5mm.6

Surgical staging for adult GCTs is the standard of care. For women who do not desire fertility, this includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and removal of all gross disease. Comprehensive nodal dissection is not indicated except when necessary for complete cytoreduction. In contrast to epithelial ovarian cancer, approximately 80% of women with adult GCTs are diagnosed with stage I disease. For stage IA disease, treatment with surgery alone is sufficient, yet in women with stage II-IV disease or with tumors that are ruptured intraoperatively, platinum-based chemotherapy is recommended. The most common regimen is bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, though there is increasing experience with an outpatient regimen of paclitaxel and carboplatin.

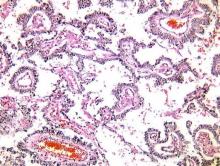

The gross appearance of both adult and juvenile GCTs are of a large, tan-yellow tumor with cystic, solid, and hemorrhagic components. Microscopically, juvenile GCTs are more distinct than that of adult GCTs. Whereas adult GCTs comprise diffuse cords or trabeculae and small follicles termed Call-Exner bodies of rounded cells with scant cytoplasm and pale “coffee-bean” nuclei, juvenile GCTs have nuclei that are rounded, hyperchromatic with moderate to abundant eosinophilic or vacuolated cytoplasm.

The prognosis of GCTs is largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis and presence of residual disease after debulking. Negative prognostic factors for recurrence include tumor size, rupture, atypia and increased mitotic activity.

There are distinct clinical, radiographic, and laboratory characteristics that may raise the suspicion of the practicing gynecologist for a GCT. In such cases, expedient referral for surgical exploration to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the tumor is encountered inadvertently, intraoperative consultation from a gynecologic oncologist should be requested. If a gynecologic oncologist is not available, it is paramount to optimize surgical exposure to clearly document any abnormal pelvic or intra-abdominal findings, take care to prevent surgical spillage, and preserve fertility if indicated.

If referred appropriately and completely resected, the 5-year overall survival of stage IA disease can be upward of 90%. Recurrences are stage dependent with an average time to recurrence of just under 5 years. When recurrences occur, they tend to happen in the pelvis. All women with a history of GCT will require surveillance and monitoring.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 May;97(2):519-23.

2. “Rare and Uncommon Gynecological Cancers: A Clinical Guide” (Heidelberg: Springer, 2011): Reed N.

3. Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Feb;55(2):231-8.

4. “Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology” (Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013): Barakat R.

5. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar;4(1):37-47.

6. “Uncommon Gynecologic Cancers” (Indianapolis: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014): Del Carmen M.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Castellano is a resident physician in the obstetrics and gynecology program at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. To comment, email them at [email protected].

Granulosa cell tumors arise from ovarian sex cords and make up an estimated 1% of all ovarian cancer cases but comprise more than 70% of all sex cord stromal tumors.

Granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) can be divided into adult and juvenile types. Adult GCTs are much more common, representing 95% of all GCTs. Women diagnosed with adult GCTs are typically younger as compared with those with epithelial ovarian cancer. The average age of diagnosis for adult GCTs is 50 years, and for women with juvenile GCTs, the average age at diagnosis is 20 years.

Granulosa cell tumors have been shown to be more common in nonwhite women, those with a high body mass index, and a family history of breast or ovarian cancer.1

Adult GCTs can be associated with Peutz-Jeghers and Potter syndromes. Juvenile GCTs are exceedingly rare but can also be associated with mesodermal dysplastic syndromes characterized by the presence of enchondromatosis and hemangioma formation, such as Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome.

Adult granulosa cell tumors are large, hormonally active tumors; typically secreting estrogen and associated with symptoms of hyperestrogenism. In one study, 55% of women with GCTs were reported to have hyperestrogenic findings such as breast tenderness, virulism, abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding, and hyperplasia, and those with juvenile GCTs may present with precocious puberty.2,3

In pregnancy, hormonal symptoms are temporized, thus the most common presentation is acute rupture. Initial evaluation of women with adult GCTs will reveal a palpable unilateral pelvic mass typically larger than 10cm. Juvenile and adult GCTs are unilateral in 95% of cases.4

In women presenting with a large adnexal mass, the appropriate initial clinical evaluation includes radiographic and laboratory studies. Endovaginal ultrasound typically reveals a large adnexal mass with heterogeneous solid and cystic components, areas of hemorrhage or necrosis and increased vascularity on Doppler. Juvenile GCTs have a more distinct appearance of solid growth with focal areas of follicular formation.

Laboratory findings suggestive of GCT include elevated inhibin-A, inhibin-B, anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), and CA-125. Inhibin-B is the most commonly used tumor marker for the clinical monitoring of adult GCTs, but AMH may be the most specific.5 Lastly, an endometrial biopsy should be considered in all patients with abnormal uterine bleeding and in all postmenopausal women with an adnexal mass and an endometrial stripe greater than 5mm.6

Surgical staging for adult GCTs is the standard of care. For women who do not desire fertility, this includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and removal of all gross disease. Comprehensive nodal dissection is not indicated except when necessary for complete cytoreduction. In contrast to epithelial ovarian cancer, approximately 80% of women with adult GCTs are diagnosed with stage I disease. For stage IA disease, treatment with surgery alone is sufficient, yet in women with stage II-IV disease or with tumors that are ruptured intraoperatively, platinum-based chemotherapy is recommended. The most common regimen is bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, though there is increasing experience with an outpatient regimen of paclitaxel and carboplatin.

The gross appearance of both adult and juvenile GCTs are of a large, tan-yellow tumor with cystic, solid, and hemorrhagic components. Microscopically, juvenile GCTs are more distinct than that of adult GCTs. Whereas adult GCTs comprise diffuse cords or trabeculae and small follicles termed Call-Exner bodies of rounded cells with scant cytoplasm and pale “coffee-bean” nuclei, juvenile GCTs have nuclei that are rounded, hyperchromatic with moderate to abundant eosinophilic or vacuolated cytoplasm.

The prognosis of GCTs is largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis and presence of residual disease after debulking. Negative prognostic factors for recurrence include tumor size, rupture, atypia and increased mitotic activity.

There are distinct clinical, radiographic, and laboratory characteristics that may raise the suspicion of the practicing gynecologist for a GCT. In such cases, expedient referral for surgical exploration to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the tumor is encountered inadvertently, intraoperative consultation from a gynecologic oncologist should be requested. If a gynecologic oncologist is not available, it is paramount to optimize surgical exposure to clearly document any abnormal pelvic or intra-abdominal findings, take care to prevent surgical spillage, and preserve fertility if indicated.

If referred appropriately and completely resected, the 5-year overall survival of stage IA disease can be upward of 90%. Recurrences are stage dependent with an average time to recurrence of just under 5 years. When recurrences occur, they tend to happen in the pelvis. All women with a history of GCT will require surveillance and monitoring.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 May;97(2):519-23.

2. “Rare and Uncommon Gynecological Cancers: A Clinical Guide” (Heidelberg: Springer, 2011): Reed N.

3. Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Feb;55(2):231-8.

4. “Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology” (Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013): Barakat R.

5. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar;4(1):37-47.

6. “Uncommon Gynecologic Cancers” (Indianapolis: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014): Del Carmen M.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Castellano is a resident physician in the obstetrics and gynecology program at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. To comment, email them at [email protected].

Granulosa cell tumors arise from ovarian sex cords and make up an estimated 1% of all ovarian cancer cases but comprise more than 70% of all sex cord stromal tumors.

Granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) can be divided into adult and juvenile types. Adult GCTs are much more common, representing 95% of all GCTs. Women diagnosed with adult GCTs are typically younger as compared with those with epithelial ovarian cancer. The average age of diagnosis for adult GCTs is 50 years, and for women with juvenile GCTs, the average age at diagnosis is 20 years.

Granulosa cell tumors have been shown to be more common in nonwhite women, those with a high body mass index, and a family history of breast or ovarian cancer.1

Adult GCTs can be associated with Peutz-Jeghers and Potter syndromes. Juvenile GCTs are exceedingly rare but can also be associated with mesodermal dysplastic syndromes characterized by the presence of enchondromatosis and hemangioma formation, such as Ollier disease or Maffucci syndrome.

Adult granulosa cell tumors are large, hormonally active tumors; typically secreting estrogen and associated with symptoms of hyperestrogenism. In one study, 55% of women with GCTs were reported to have hyperestrogenic findings such as breast tenderness, virulism, abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding, and hyperplasia, and those with juvenile GCTs may present with precocious puberty.2,3

In pregnancy, hormonal symptoms are temporized, thus the most common presentation is acute rupture. Initial evaluation of women with adult GCTs will reveal a palpable unilateral pelvic mass typically larger than 10cm. Juvenile and adult GCTs are unilateral in 95% of cases.4

In women presenting with a large adnexal mass, the appropriate initial clinical evaluation includes radiographic and laboratory studies. Endovaginal ultrasound typically reveals a large adnexal mass with heterogeneous solid and cystic components, areas of hemorrhage or necrosis and increased vascularity on Doppler. Juvenile GCTs have a more distinct appearance of solid growth with focal areas of follicular formation.

Laboratory findings suggestive of GCT include elevated inhibin-A, inhibin-B, anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), and CA-125. Inhibin-B is the most commonly used tumor marker for the clinical monitoring of adult GCTs, but AMH may be the most specific.5 Lastly, an endometrial biopsy should be considered in all patients with abnormal uterine bleeding and in all postmenopausal women with an adnexal mass and an endometrial stripe greater than 5mm.6

Surgical staging for adult GCTs is the standard of care. For women who do not desire fertility, this includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and removal of all gross disease. Comprehensive nodal dissection is not indicated except when necessary for complete cytoreduction. In contrast to epithelial ovarian cancer, approximately 80% of women with adult GCTs are diagnosed with stage I disease. For stage IA disease, treatment with surgery alone is sufficient, yet in women with stage II-IV disease or with tumors that are ruptured intraoperatively, platinum-based chemotherapy is recommended. The most common regimen is bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin, though there is increasing experience with an outpatient regimen of paclitaxel and carboplatin.

The gross appearance of both adult and juvenile GCTs are of a large, tan-yellow tumor with cystic, solid, and hemorrhagic components. Microscopically, juvenile GCTs are more distinct than that of adult GCTs. Whereas adult GCTs comprise diffuse cords or trabeculae and small follicles termed Call-Exner bodies of rounded cells with scant cytoplasm and pale “coffee-bean” nuclei, juvenile GCTs have nuclei that are rounded, hyperchromatic with moderate to abundant eosinophilic or vacuolated cytoplasm.

The prognosis of GCTs is largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis and presence of residual disease after debulking. Negative prognostic factors for recurrence include tumor size, rupture, atypia and increased mitotic activity.

There are distinct clinical, radiographic, and laboratory characteristics that may raise the suspicion of the practicing gynecologist for a GCT. In such cases, expedient referral for surgical exploration to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the tumor is encountered inadvertently, intraoperative consultation from a gynecologic oncologist should be requested. If a gynecologic oncologist is not available, it is paramount to optimize surgical exposure to clearly document any abnormal pelvic or intra-abdominal findings, take care to prevent surgical spillage, and preserve fertility if indicated.

If referred appropriately and completely resected, the 5-year overall survival of stage IA disease can be upward of 90%. Recurrences are stage dependent with an average time to recurrence of just under 5 years. When recurrences occur, they tend to happen in the pelvis. All women with a history of GCT will require surveillance and monitoring.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 May;97(2):519-23.

2. “Rare and Uncommon Gynecological Cancers: A Clinical Guide” (Heidelberg: Springer, 2011): Reed N.

3. Obstet Gynecol. 1980 Feb;55(2):231-8.

4. “Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology” (Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013): Barakat R.

5. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar;4(1):37-47.

6. “Uncommon Gynecologic Cancers” (Indianapolis: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014): Del Carmen M.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Castellano is a resident physician in the obstetrics and gynecology program at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. To comment, email them at [email protected].

Management of adnexal masses in pregnancy

Roughly 1%-2% of pregnancies are complicated by an adnexal mass, and prenatal ultrasound for fetal evaluation has detected more asymptomatic ovarian masses as a result.

The differential diagnosis for adnexal mass is broad and includes follicular or corpus luteum cysts, mature teratoma, theca lutein cyst, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, cystadenoma, pedunculated leiomyoma, luteoma, as well as malignant neoplasms of epithelial, germ cell, and sex cord–stromal origin (J Ultrasound Med. 2004 Jun;23[6]:805-19). Most masses will be benign neoplasms, with a fraction identified as malignancies.

In 2013, Baser et al. performed a retrospective study of 151 women who underwent surgery of an adnexal mass at time of cesarean delivery. Of the 151 cases reviewed, 148 (98%) of the masses were benign (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;123[2]:124-6). Additionally, if the patient presents with pain, diagnoses such as ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, degenerating fibroid, and torsion should also be considered.

Diagnostic evaluation and management

The majority of adnexal masses identified in pregnancy are benign simple cysts measuring less than 5 cm in diameter. Approximately 70% of cystic masses detected in the first trimester will spontaneously resolve by the second trimester (Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;49[3]:492-505). However, for some masses, surgical resection is warranted.

Masses present after the first trimester and that are (1) greater than 10cm in diameter or (2) are solid or contain solid and cystic areas or have septated or papillary areas, are generally managed surgically as these features increase the risk of malignancy or complications such as adnexal torsion, rupture, or labor dystocia (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):315-21).

Adnexal masses without these features often resolve during pregnancy and can be expectantly managed (Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105[5 Pt 1]:1098-103). The optimal time for surgical intervention is after the first trimester as organogenesis is largely complete, therefore minimizing the risk of drug-induced teratogenesis, and any necessary cystectomy or oophorectomy will not disrupt the required progesterone production of the corpus luteum as this has been replaced by the placenta.

Preoperative assessment

For most cases, imaging with ultrasound is adequate for preoperative evaluation; however, in some cases, further imaging is needed for appropriate characterization of the mass. In this situation, further imaging with MRI is preferred as this modality has good resolution for visualization of soft tissue pathology and does not expose the patient and fetus to ionizing radiation. Of note, Gadolinium-based contrast should be avoided as effects have not been well established in pregnancy (AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Aug;191[2]:364-70).

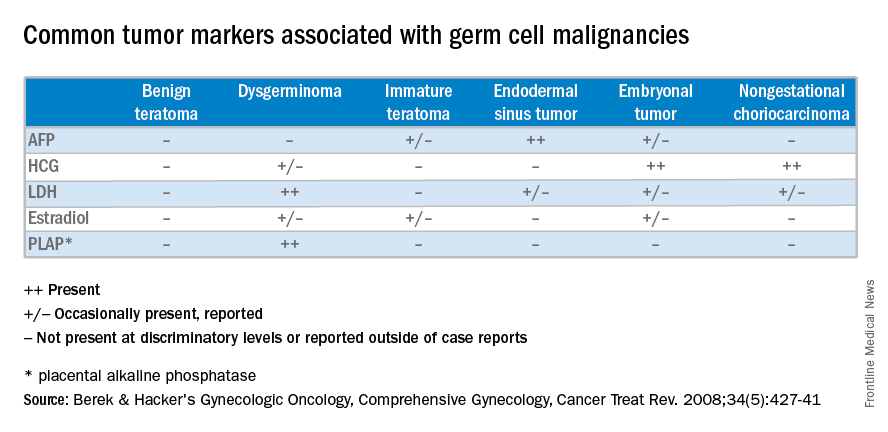

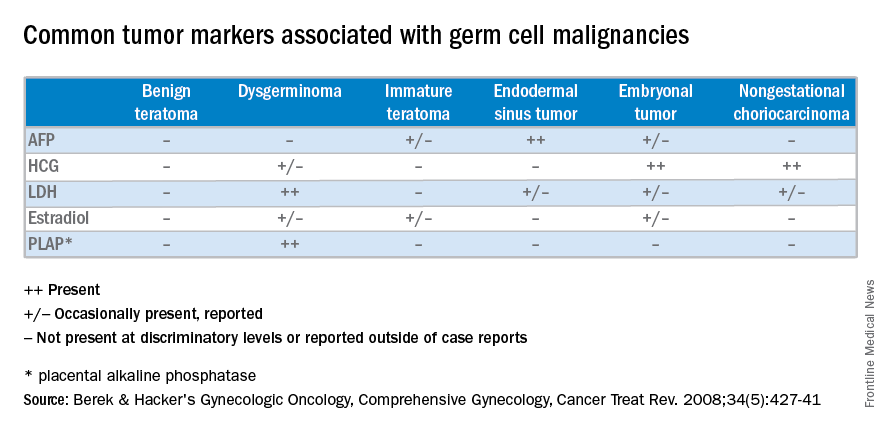

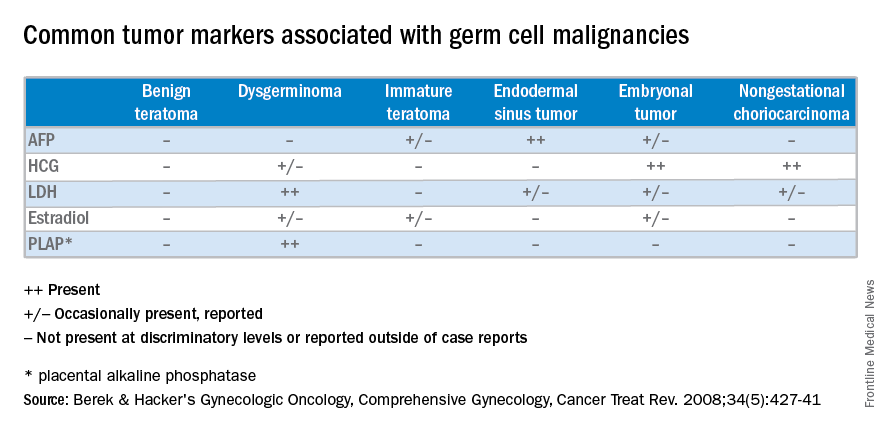

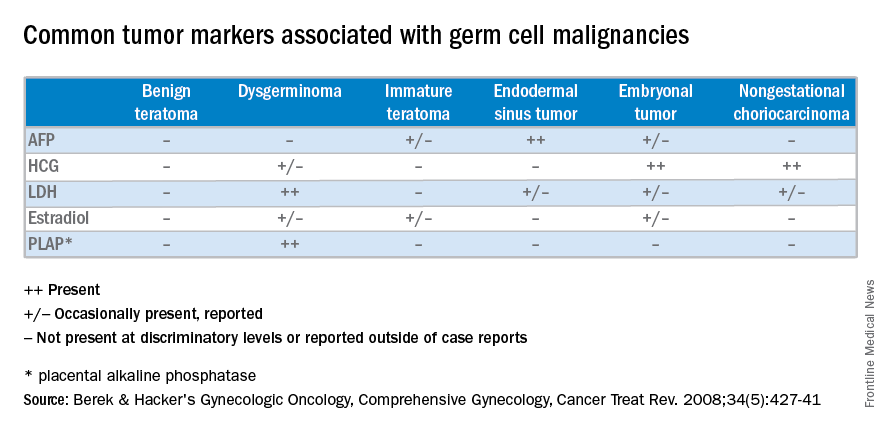

If there is concern for malignancy during pregnancy, drawing serum tumor markers preoperatively is typically not suggested. Oncofetal antigens, including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), are elevated during gestation, making them poor markers for malignancy. If malignancy is ultimately diagnosed, then tumor markers can be obtained immediately postoperatively.

Surgical approach and prognosis

If there is low suspicion for malignancy, a laparoscopic approach is preferable and reasonable at all stages of pregnancy, although early second trimester is ideal. Entry at Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant versus the umbilicus is preferable in order to minimize risk of uterine injury.

If malignancy is suspected, maximum exposure should be obtained with a midline vertical incision. Peritoneal washings should be obtained on immediate entry of the peritoneal cavity, and the contralateral ovary should also be adequately examined along with a general abdominopelvic survey. If the mass demonstrates concerning features, such as solid features or presence of ascites, then the specimen should be sent for intraoperative frozen pathology, and the pathologist should be made aware of the concurrent pregnancy. If malignancy is confirmed on frozen pathology, a full staging procedure should be performed and a gynecologic oncologist consulted.

Roughly three-quarters of invasive ovarian cancers diagnosed in pregnancy are early stage disease, and the 5-year survival of ovarian cancers associated with pregnancy is between 72% and 90% (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 Jan-Feb;16[1]:8-15).

In a retrospective cohort study of 101 pregnant women, 31% of adnexal masses resected in pregnant women greater than 14 weeks gestation were teratomas. In total, 23% of masses were luteal cysts. Less commonly, patients were diagnosed with serous cystadenoma (14%), endometrioma (8%), mucinous cystadenoma (7%), benign cyst (6%), tumor of low malignant potential (5%), and paratubal cyst (3%).

In this study, approximately half of the women underwent minimally invasive surgery and half had surgery via laparotomy. There were more complications in the women undergoing laparotomy (ileus) and there were no differences between the groups with regards to pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 Nov-Dec;18[6]:720-5).

In general, characteristics that are favorable for spontaneous resolution include masses that are simple in nature by ultrasound and less than 5 cm to 6 cm in diameter.

For women with simple-appearing masses on ultrasound, reimaging can occur during the remainder of the pregnancy at the discretion of the physician or during the postpartum period. All women should be provided with torsion and rupture precautions during the pregnancy (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;205[2]:97-102). For women with more concerning features on ultrasound, referral to a gynecologic oncologist is warranted. If the decision for surgical management is made, minimally invasive surgery should be strongly considered due to minimal maternal and perinatal morbidity.

Dr. Staley is a resident physician in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Roughly 1%-2% of pregnancies are complicated by an adnexal mass, and prenatal ultrasound for fetal evaluation has detected more asymptomatic ovarian masses as a result.

The differential diagnosis for adnexal mass is broad and includes follicular or corpus luteum cysts, mature teratoma, theca lutein cyst, hydrosalpinx, endometrioma, cystadenoma, pedunculated leiomyoma, luteoma, as well as malignant neoplasms of epithelial, germ cell, and sex cord–stromal origin (J Ultrasound Med. 2004 Jun;23[6]:805-19). Most masses will be benign neoplasms, with a fraction identified as malignancies.

In 2013, Baser et al. performed a retrospective study of 151 women who underwent surgery of an adnexal mass at time of cesarean delivery. Of the 151 cases reviewed, 148 (98%) of the masses were benign (Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;123[2]:124-6). Additionally, if the patient presents with pain, diagnoses such as ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, degenerating fibroid, and torsion should also be considered.

Diagnostic evaluation and management

The majority of adnexal masses identified in pregnancy are benign simple cysts measuring less than 5 cm in diameter. Approximately 70% of cystic masses detected in the first trimester will spontaneously resolve by the second trimester (Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Sep;49[3]:492-505). However, for some masses, surgical resection is warranted.

Masses present after the first trimester and that are (1) greater than 10cm in diameter or (2) are solid or contain solid and cystic areas or have septated or papillary areas, are generally managed surgically as these features increase the risk of malignancy or complications such as adnexal torsion, rupture, or labor dystocia (Gynecol Oncol. 2006 May;101(2):315-21).

Adnexal masses without these features often resolve during pregnancy and can be expectantly managed (Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105[5 Pt 1]:1098-103). The optimal time for surgical intervention is after the first trimester as organogenesis is largely complete, therefore minimizing the risk of drug-induced teratogenesis, and any necessary cystectomy or oophorectomy will not disrupt the required progesterone production of the corpus luteum as this has been replaced by the placenta.

Preoperative assessment

For most cases, imaging with ultrasound is adequate for preoperative evaluation; however, in some cases, further imaging is needed for appropriate characterization of the mass. In this situation, further imaging with MRI is preferred as this modality has good resolution for visualization of soft tissue pathology and does not expose the patient and fetus to ionizing radiation. Of note, Gadolinium-based contrast should be avoided as effects have not been well established in pregnancy (AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008 Aug;191[2]:364-70).

If there is concern for malignancy during pregnancy, drawing serum tumor markers preoperatively is typically not suggested. Oncofetal antigens, including alpha fetoprotein (AFP), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), are elevated during gestation, making them poor markers for malignancy. If malignancy is ultimately diagnosed, then tumor markers can be obtained immediately postoperatively.

Surgical approach and prognosis