User login

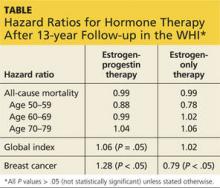

Managing menopausal symptoms in women with a BRCA mutation

This audiocast was recorded at the North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting held September 30 to October 3, 2015, in Las Vegas, Nevada

For more on this topic, read Dr. Kaunitz's August 2015 Cases in Menopause article, Is menopausal hormone therapy safe when your patient carries a BRCA mutation?

This audiocast was recorded at the North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting held September 30 to October 3, 2015, in Las Vegas, Nevada

For more on this topic, read Dr. Kaunitz's August 2015 Cases in Menopause article, Is menopausal hormone therapy safe when your patient carries a BRCA mutation?

This audiocast was recorded at the North American Menopause Society Annual Meeting held September 30 to October 3, 2015, in Las Vegas, Nevada

For more on this topic, read Dr. Kaunitz's August 2015 Cases in Menopause article, Is menopausal hormone therapy safe when your patient carries a BRCA mutation?

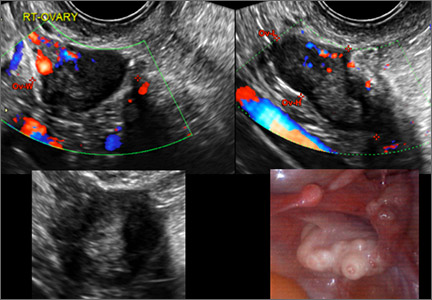

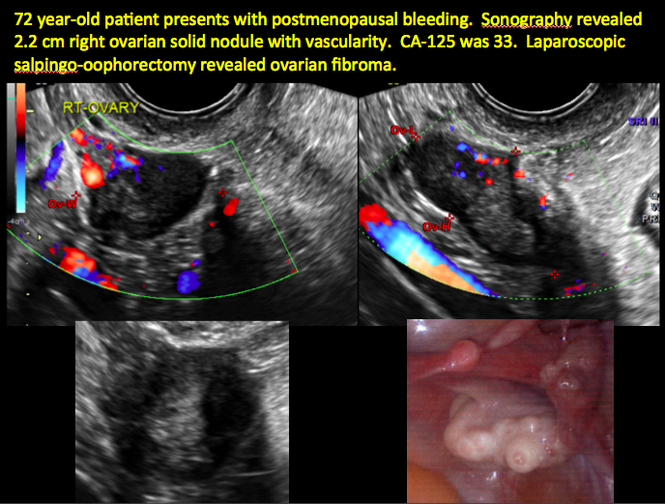

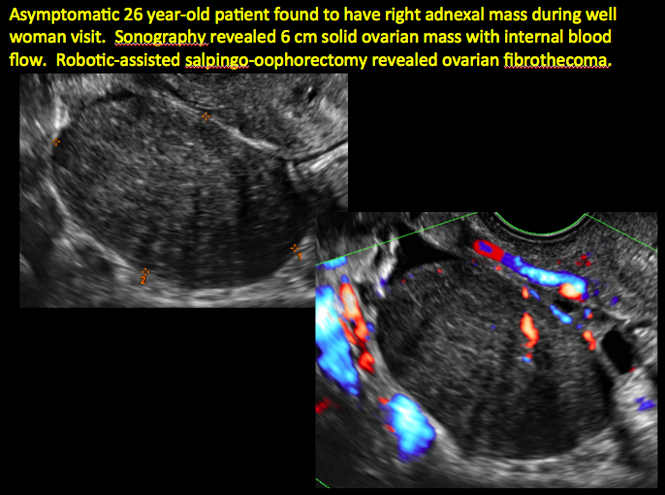

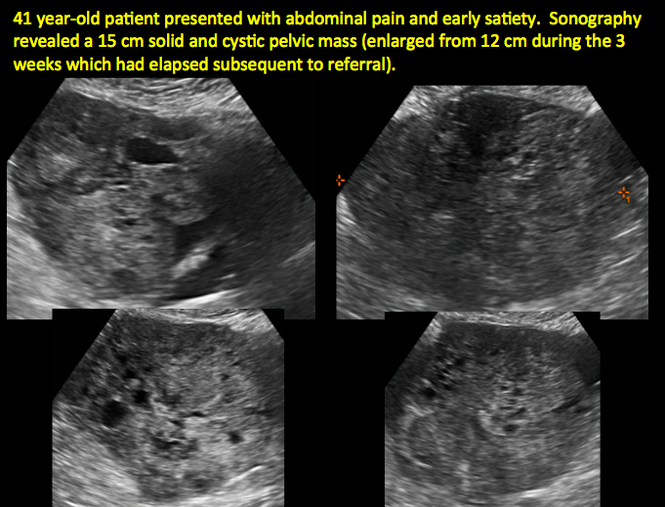

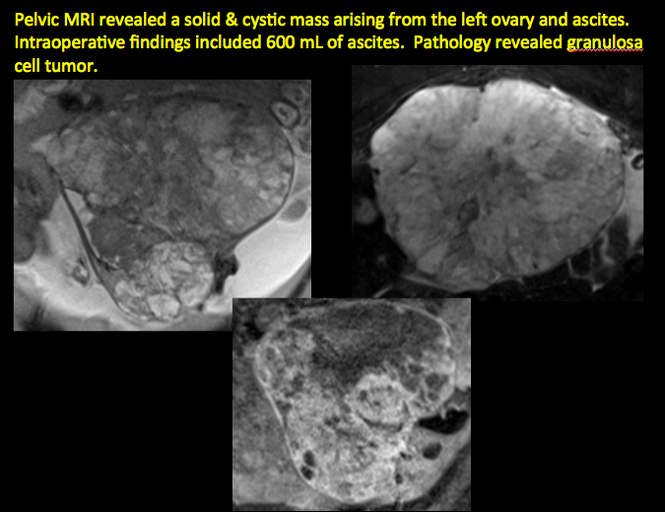

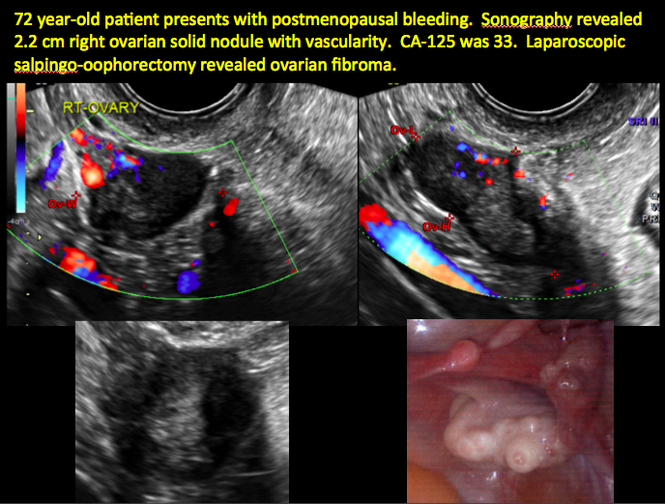

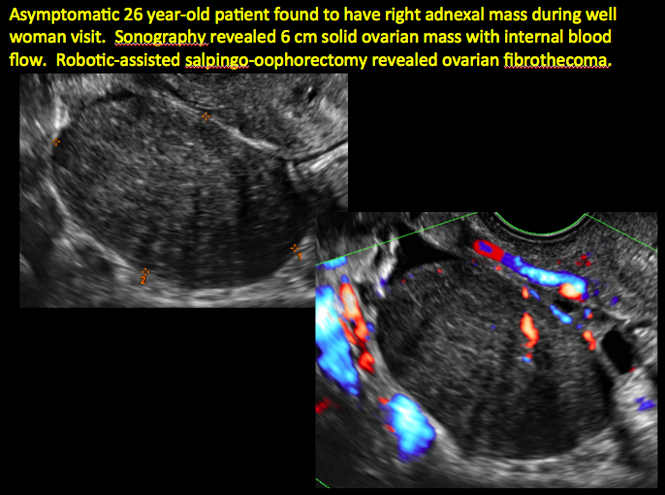

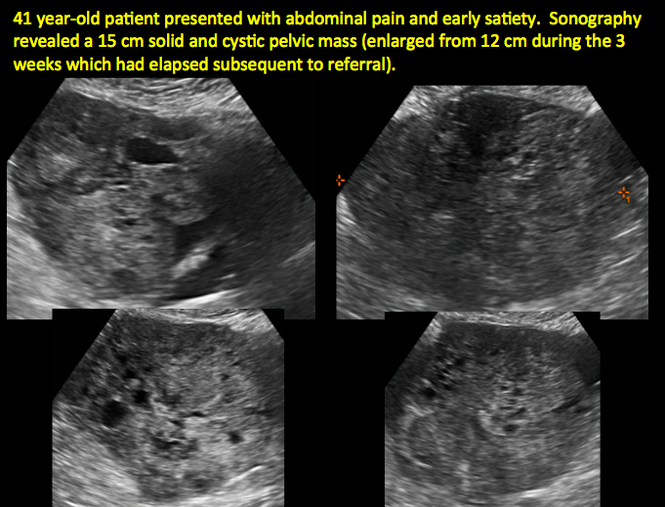

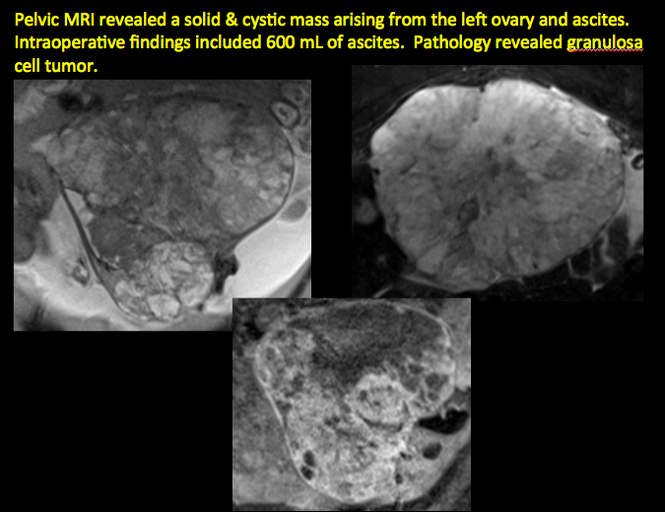

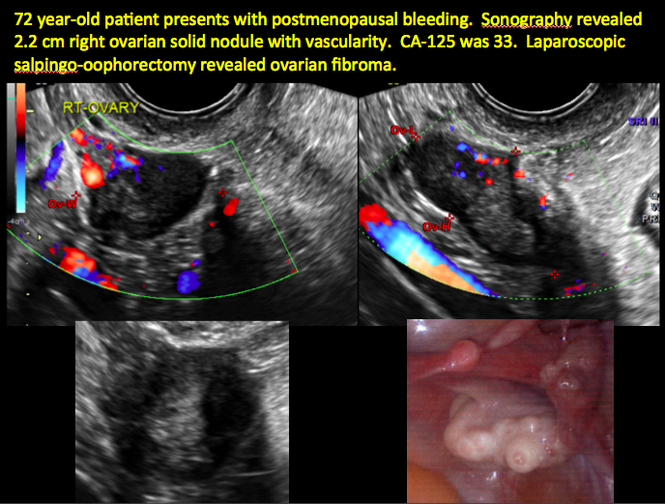

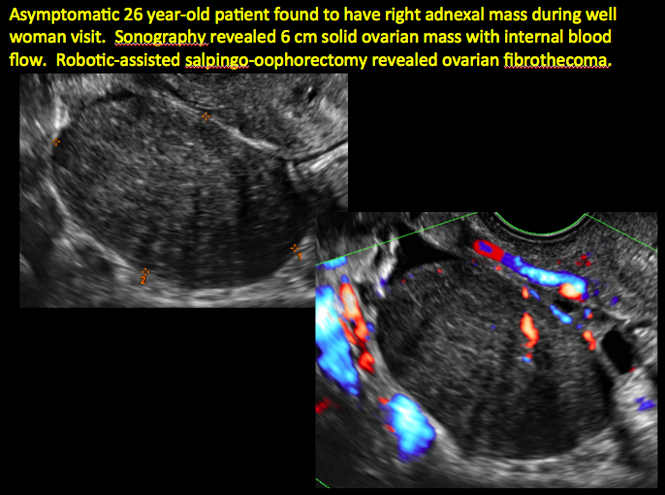

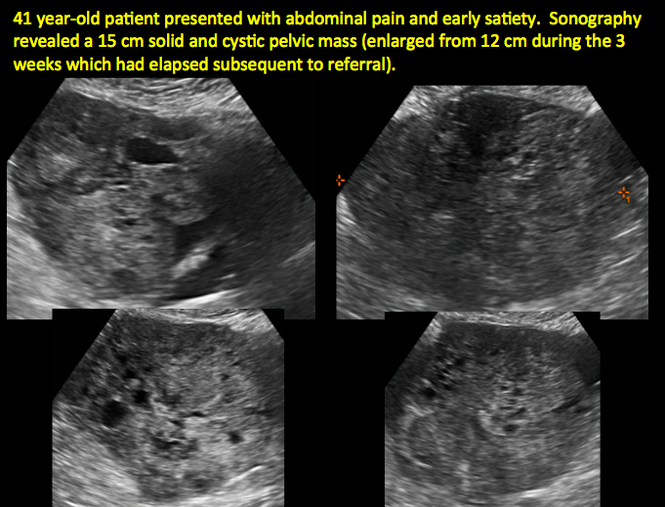

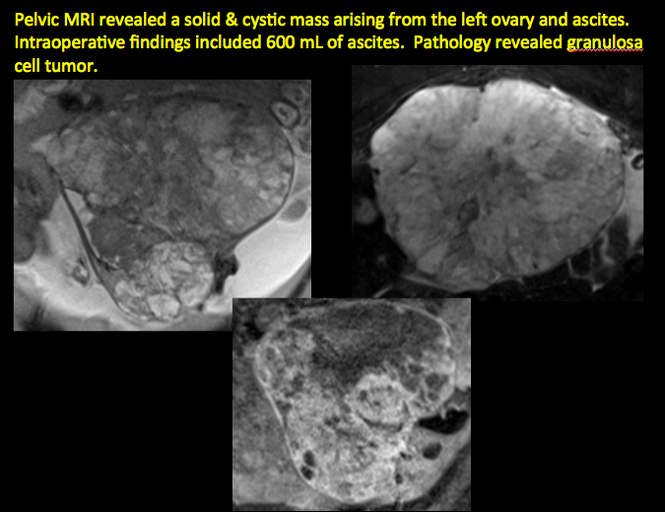

Imaging the suspected ovarian malignancy: 14 cases

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts given its ability to characterize such cysts with high resolution and accuracy. Most cystic adnexal masses have characteristic findings that can guide counseling and management decisions. For instance, mature cystic teratomas have hyperechoic lines/dots and acoustic shadowing; hydrosalpinx are tubular or s shaped and show a “waist sign.”

In parts 1 through 3 of this 4-part series on adnexal pathology, we presented images detailing common benign adnexal cysts, including:

- simple and hemorrhagic cysts (Part 1:Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts)

- mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) and endometriomas (Part 2: Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3: “Cogwheel” and other signs of hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts)

In this conclusion to the series, we detail imaging for ovarian neoplasias (including cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma).

OVARIAN NEOPLASIA

A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for suspected ovarian malignancy is 5% to 10% in the United States, and only about 13% to 21% of those undergoing surgery will actually be diagnosed with ovarian cancer.1 Therefore, the goal of diagnostic evaluation is to exclude malignancy.

Diagnostic evaluation includes:

- imaging

- lab work

- history

- physical findings.

The preferred imaging modality for a pelvic mass in asymptomatic premenopausal and postmenopausal women is transvaginal ultrasonography according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) practice bulletin, which was reaffirmed in 2013.1 “No alternative imaging modality has demonstrated sufficient superiority to transvaginal ultrasonography to justify its routine use.”1

Transvaginal ultrasonography with color Doppler interrogation has demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.86% and a specificity of 0.91% for discriminating between malignant and benign ovarian masses.

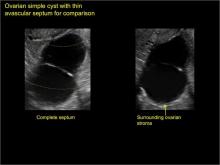

Sonographic features that are worrisome for malignancy include:

- Multiple thin septations (if indeterminate, the mass may possibly be benign)

- Thick (> 3 mm), irregular septations

- Focal areas of wall thickening (> 3 mm)

- Mural nodules or papillary projections

- Levine and colleagues note that a cyst with a mural nodule with internal blood flow on color Doppler has the highest likelihood of being malignant2

- Moderate or large amount of ascitic fluid in pelvis (in conjunction with ovarian mass showing the above characteristics)

Various morphology indices have been developed that combine these criteria with ovarian mass volume to determine the preoperative predictive value for malignancy.

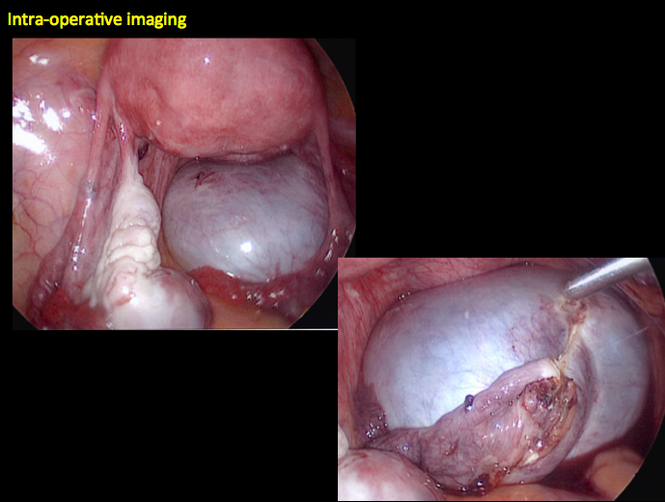

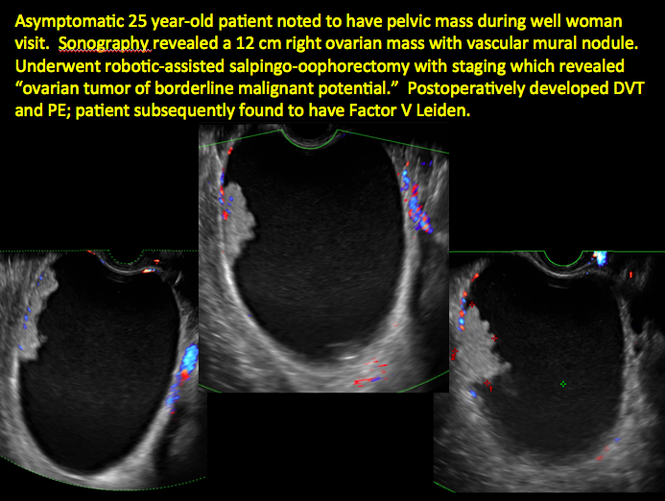

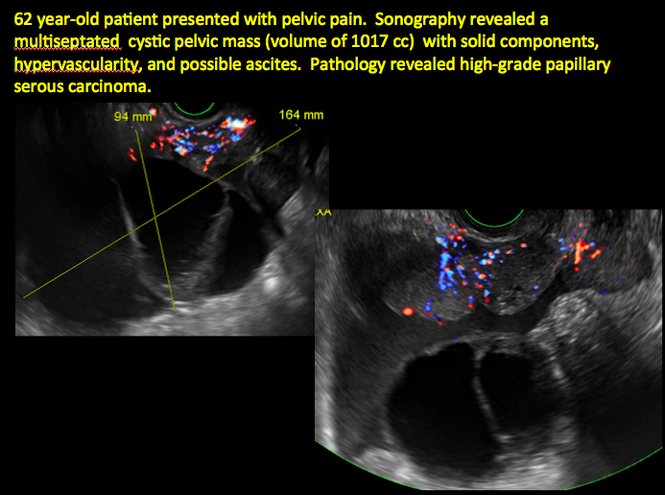

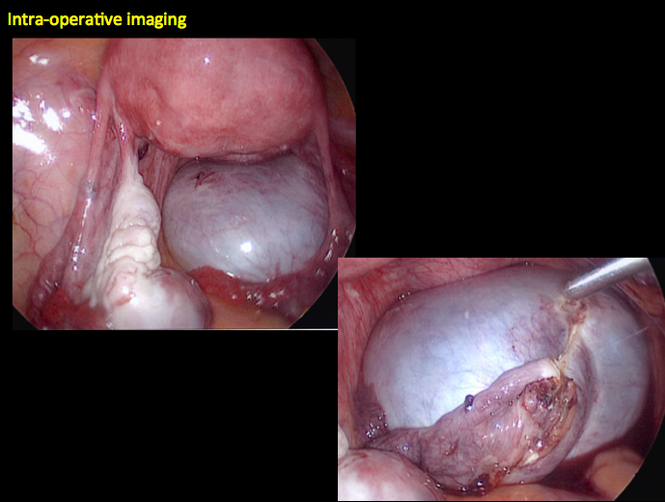

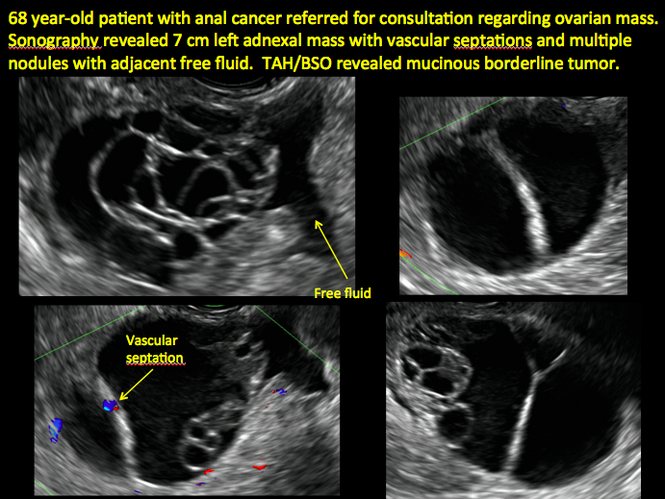

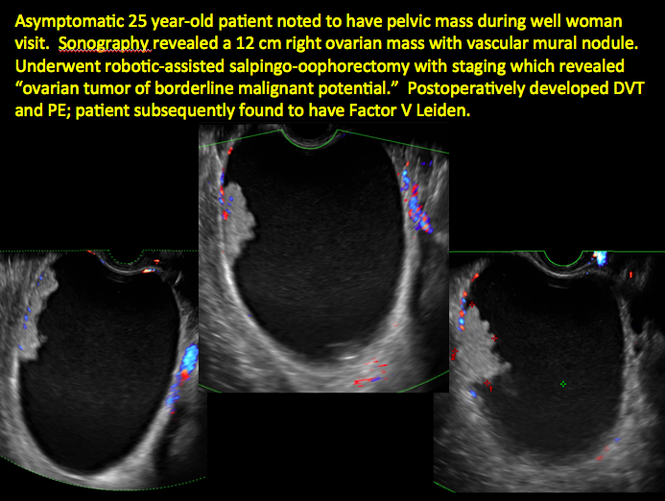

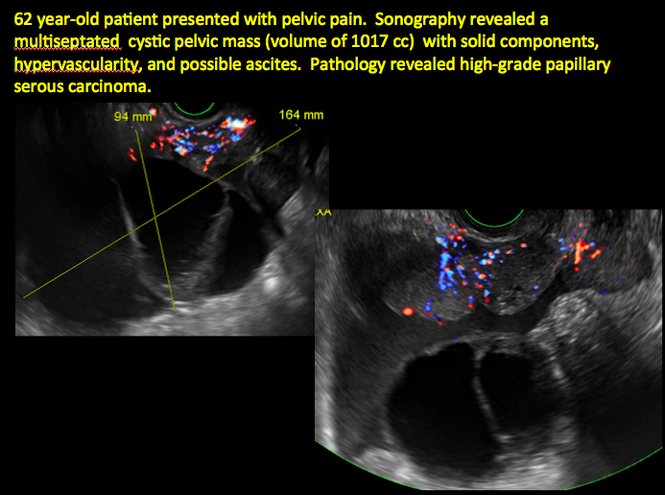

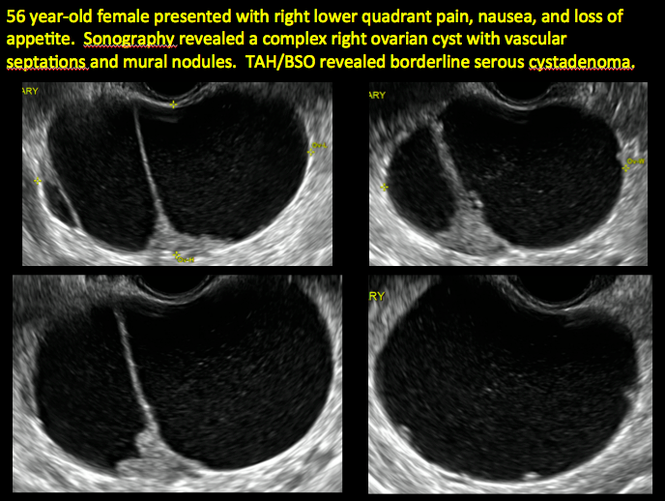

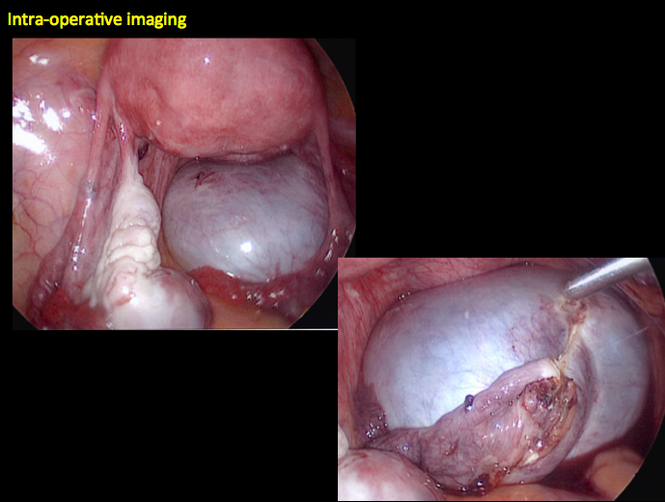

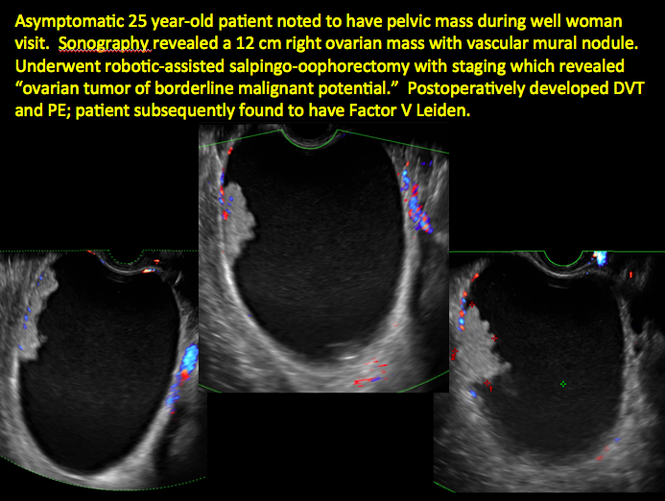

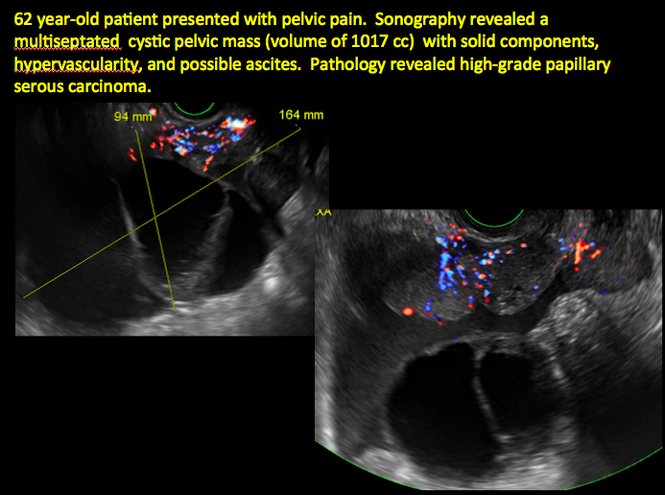

In the images that follow, we present 14 cases that demonstrate cystadenoma, low malignant potential tumors, and ovarian neoplasia.

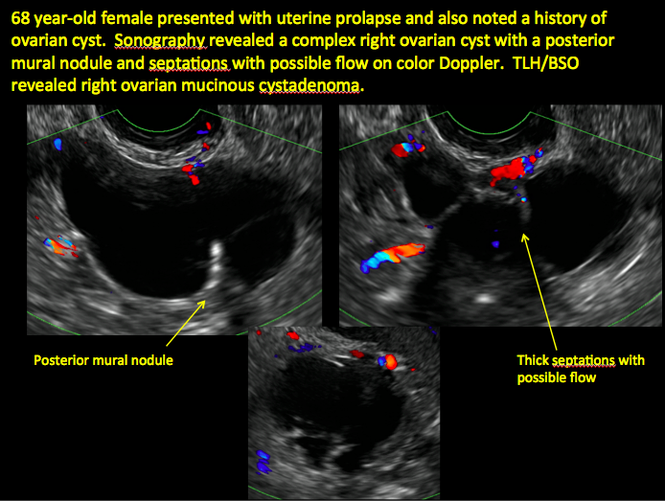

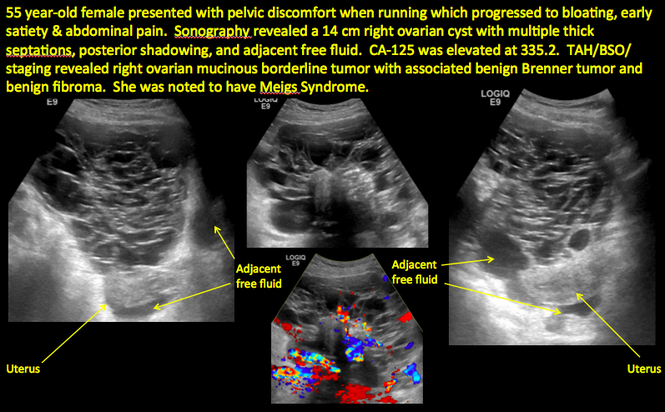

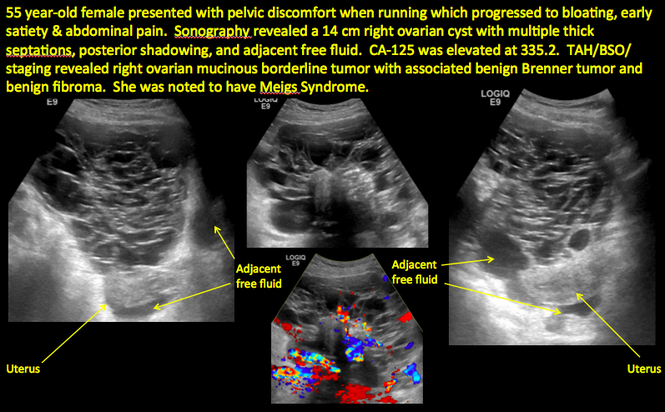

CASE 1. Right ovarian mucinous cystadenoma in 68-year-old woman with uterine prolapse and history of ovarian cyst

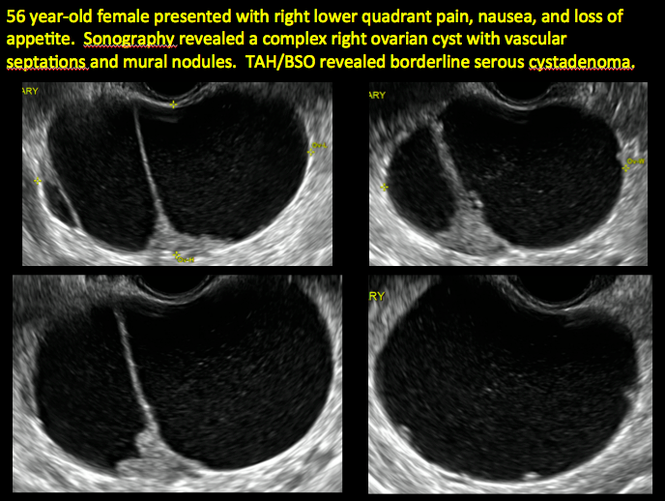

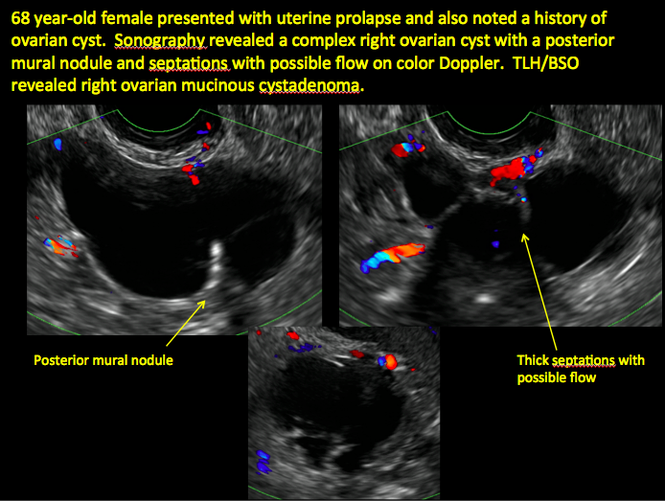

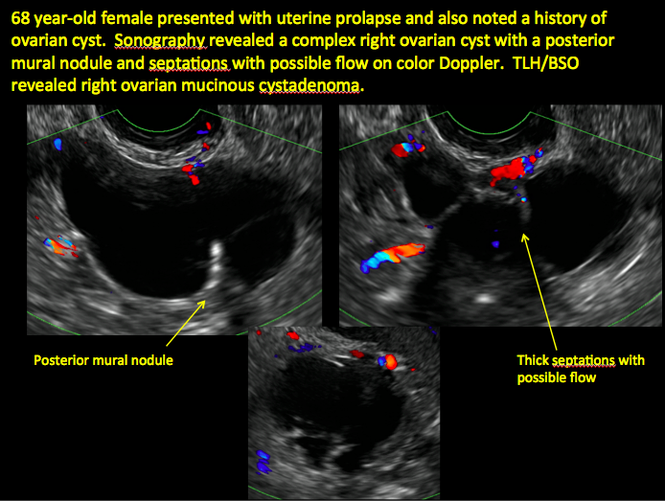

CASE 2. Borderline serous cystadenoma in 56-year-old woman with right lower quadrant pain, nausea, and loss of appetite

CASE 3. Mucinous cystadenoma in 38-year-old woman undergoing sonography for spontaneous abortion

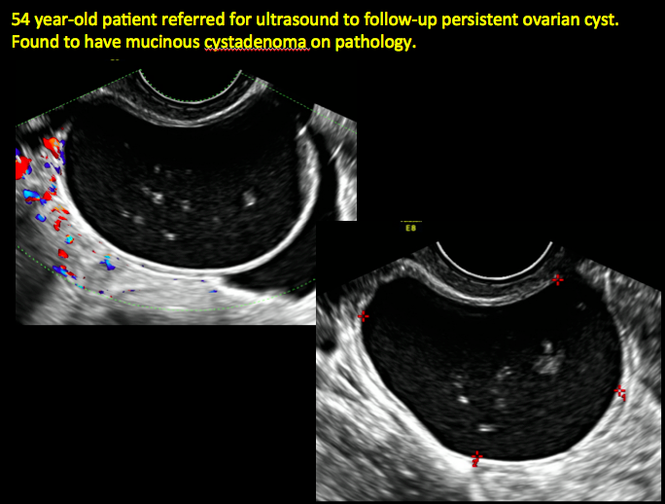

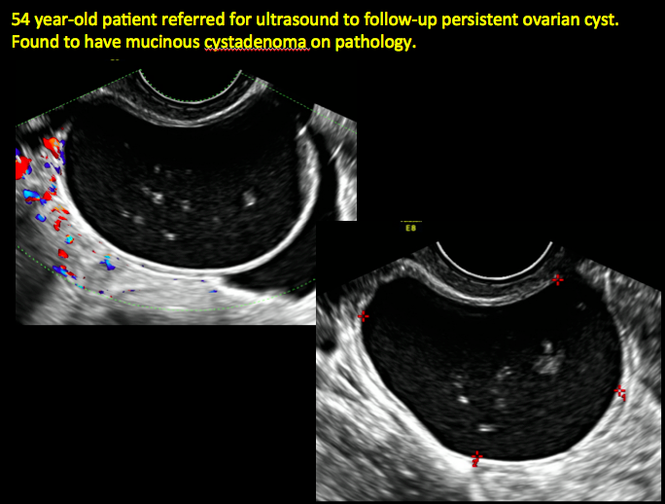

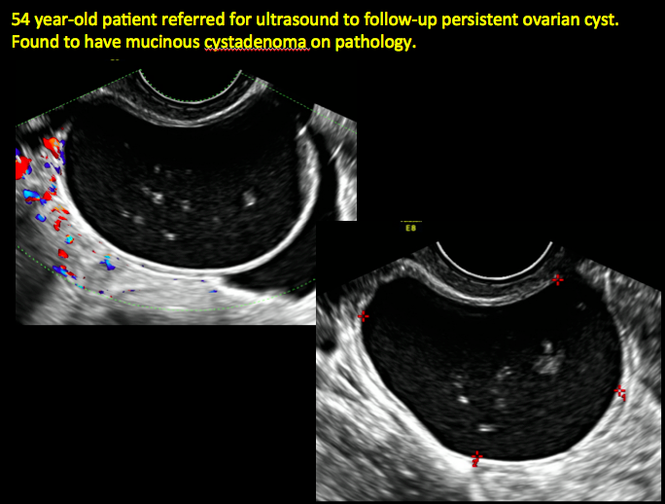

CASE 4. Mucinous cystadenoma in 54-year-old woman undergoing follow-up ultrasound for persistent ovarian cyst

CASE 7. Mature cystic teratoma in 31-year-old woman with progressively heavier bleeding and pelvic pain

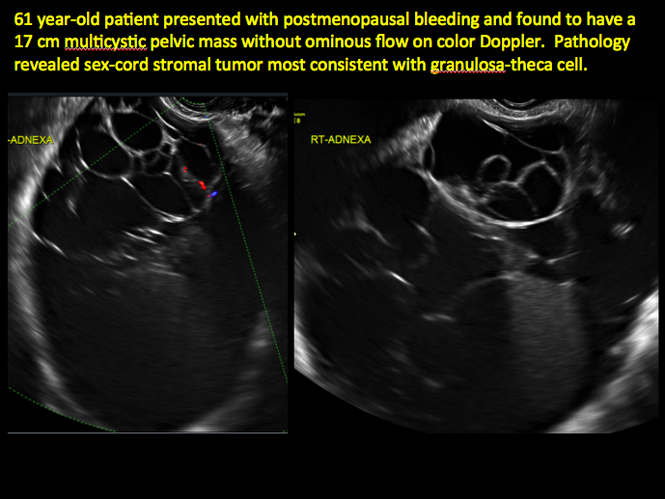

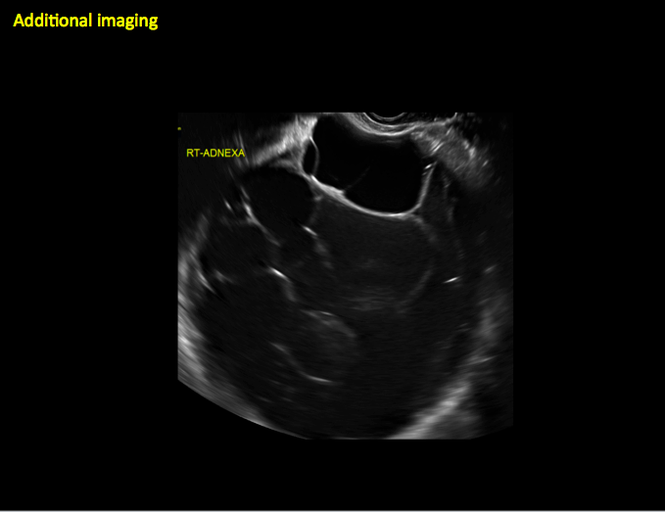

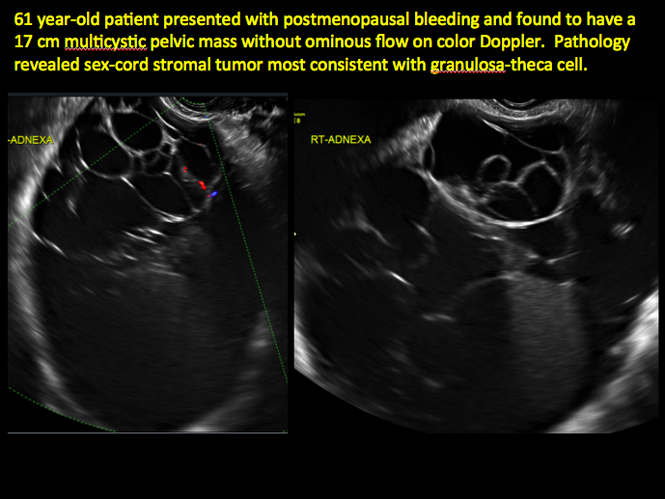

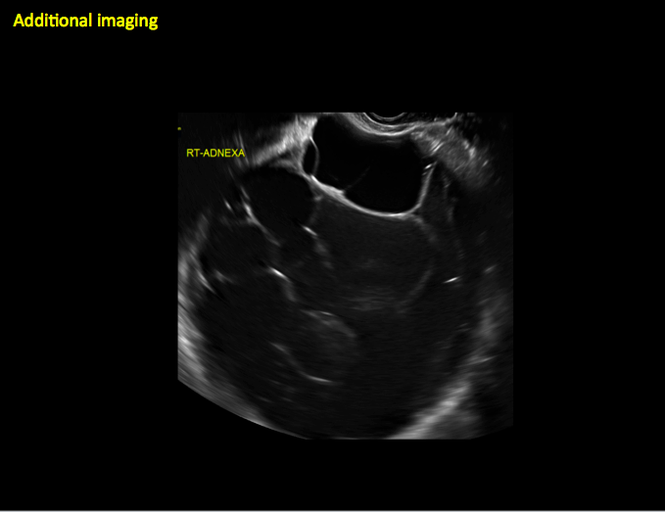

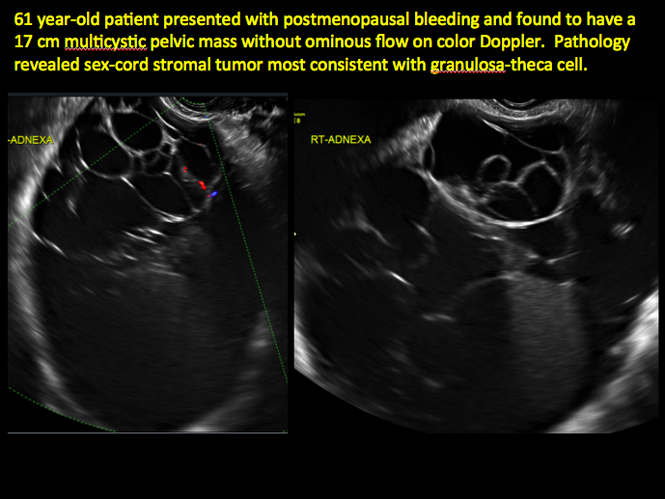

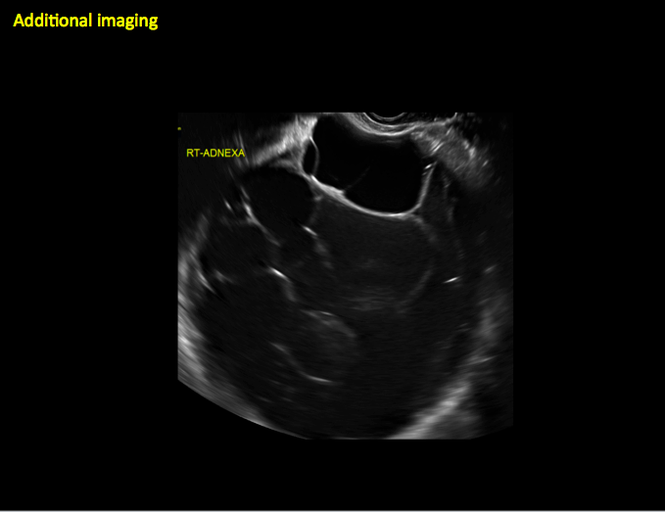

CASE 11. Sex-cord stromal tumor in 61-year-old woman with postmenopausal bleeding

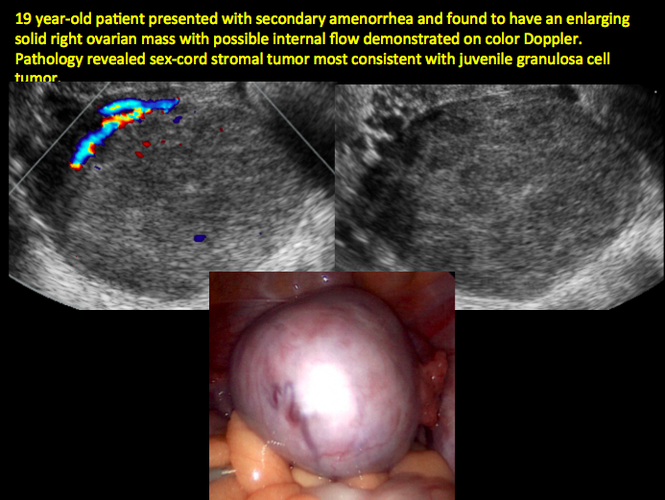

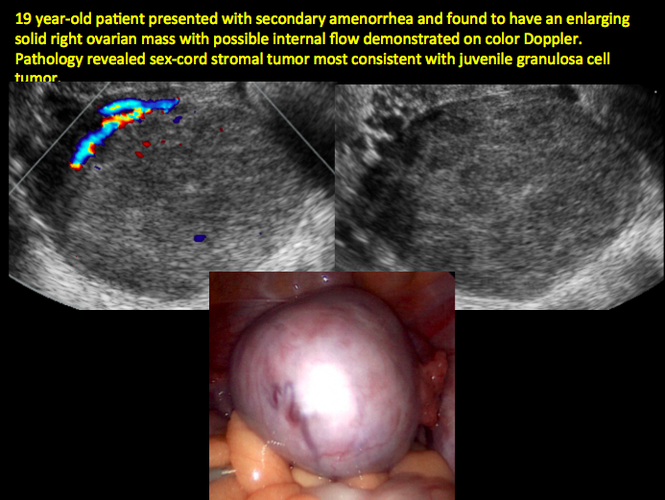

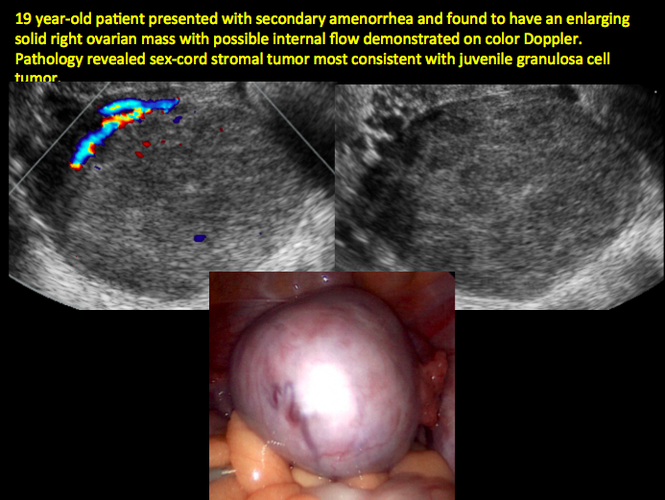

CASE 12. Juvenile granulosa cell tumor in 19-year-old patient with secondary amenorrhea

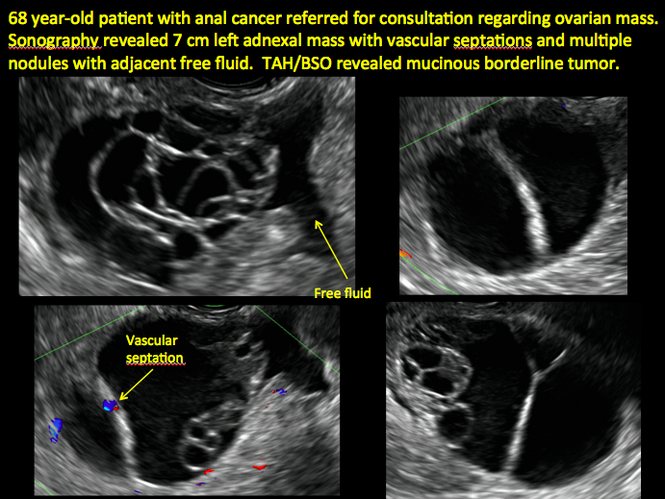

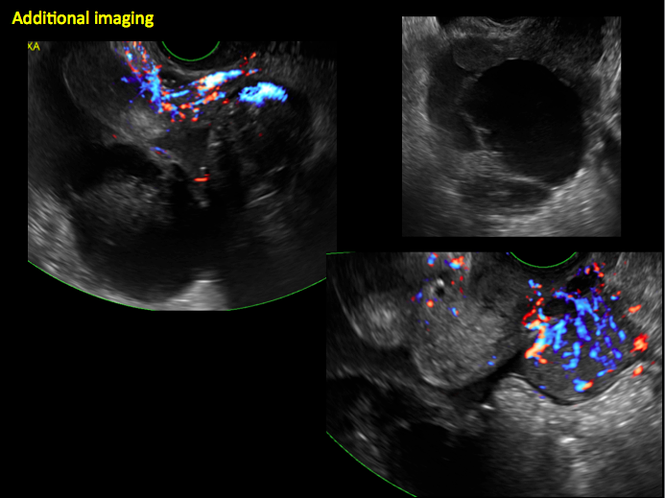

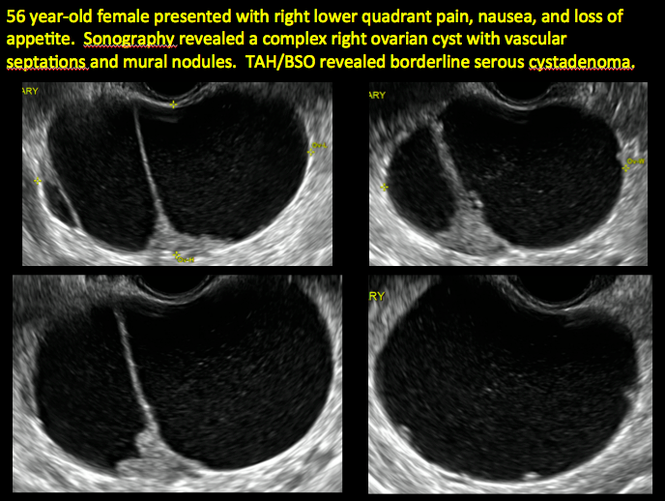

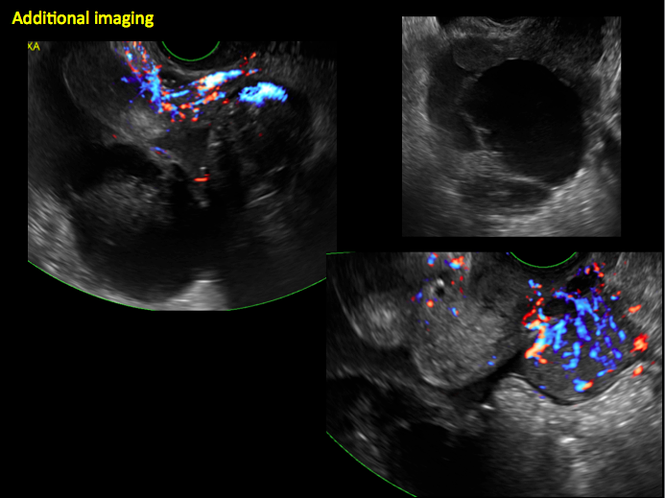

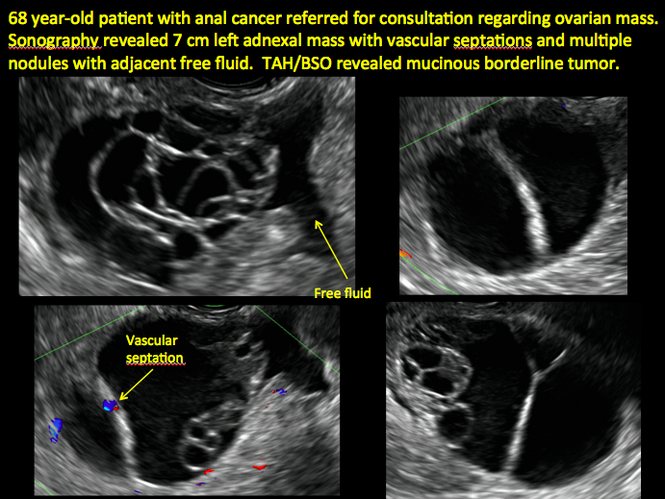

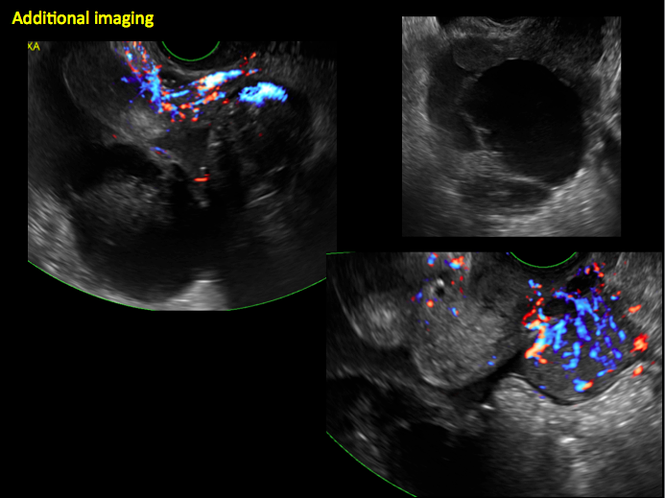

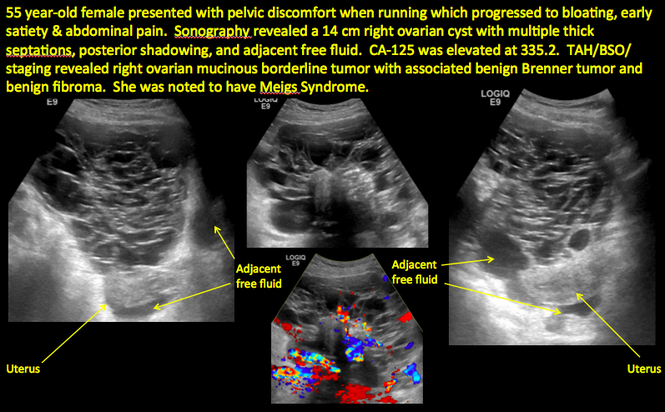

CASE 14. Mucinous borderline tumor in 55-year-old woman with pelvic discomfort

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts given its ability to characterize such cysts with high resolution and accuracy. Most cystic adnexal masses have characteristic findings that can guide counseling and management decisions. For instance, mature cystic teratomas have hyperechoic lines/dots and acoustic shadowing; hydrosalpinx are tubular or s shaped and show a “waist sign.”

In parts 1 through 3 of this 4-part series on adnexal pathology, we presented images detailing common benign adnexal cysts, including:

- simple and hemorrhagic cysts (Part 1:Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts)

- mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) and endometriomas (Part 2: Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3: “Cogwheel” and other signs of hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts)

In this conclusion to the series, we detail imaging for ovarian neoplasias (including cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma).

OVARIAN NEOPLASIA

A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for suspected ovarian malignancy is 5% to 10% in the United States, and only about 13% to 21% of those undergoing surgery will actually be diagnosed with ovarian cancer.1 Therefore, the goal of diagnostic evaluation is to exclude malignancy.

Diagnostic evaluation includes:

- imaging

- lab work

- history

- physical findings.

The preferred imaging modality for a pelvic mass in asymptomatic premenopausal and postmenopausal women is transvaginal ultrasonography according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) practice bulletin, which was reaffirmed in 2013.1 “No alternative imaging modality has demonstrated sufficient superiority to transvaginal ultrasonography to justify its routine use.”1

Transvaginal ultrasonography with color Doppler interrogation has demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.86% and a specificity of 0.91% for discriminating between malignant and benign ovarian masses.

Sonographic features that are worrisome for malignancy include:

- Multiple thin septations (if indeterminate, the mass may possibly be benign)

- Thick (> 3 mm), irregular septations

- Focal areas of wall thickening (> 3 mm)

- Mural nodules or papillary projections

- Levine and colleagues note that a cyst with a mural nodule with internal blood flow on color Doppler has the highest likelihood of being malignant2

- Moderate or large amount of ascitic fluid in pelvis (in conjunction with ovarian mass showing the above characteristics)

Various morphology indices have been developed that combine these criteria with ovarian mass volume to determine the preoperative predictive value for malignancy.

In the images that follow, we present 14 cases that demonstrate cystadenoma, low malignant potential tumors, and ovarian neoplasia.

CASE 1. Right ovarian mucinous cystadenoma in 68-year-old woman with uterine prolapse and history of ovarian cyst

CASE 2. Borderline serous cystadenoma in 56-year-old woman with right lower quadrant pain, nausea, and loss of appetite

CASE 3. Mucinous cystadenoma in 38-year-old woman undergoing sonography for spontaneous abortion

CASE 4. Mucinous cystadenoma in 54-year-old woman undergoing follow-up ultrasound for persistent ovarian cyst

CASE 7. Mature cystic teratoma in 31-year-old woman with progressively heavier bleeding and pelvic pain

CASE 11. Sex-cord stromal tumor in 61-year-old woman with postmenopausal bleeding

CASE 12. Juvenile granulosa cell tumor in 19-year-old patient with secondary amenorrhea

CASE 14. Mucinous borderline tumor in 55-year-old woman with pelvic discomfort

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts given its ability to characterize such cysts with high resolution and accuracy. Most cystic adnexal masses have characteristic findings that can guide counseling and management decisions. For instance, mature cystic teratomas have hyperechoic lines/dots and acoustic shadowing; hydrosalpinx are tubular or s shaped and show a “waist sign.”

In parts 1 through 3 of this 4-part series on adnexal pathology, we presented images detailing common benign adnexal cysts, including:

- simple and hemorrhagic cysts (Part 1:Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts)

- mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) and endometriomas (Part 2: Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3: “Cogwheel” and other signs of hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts)

In this conclusion to the series, we detail imaging for ovarian neoplasias (including cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma).

OVARIAN NEOPLASIA

A woman’s lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for suspected ovarian malignancy is 5% to 10% in the United States, and only about 13% to 21% of those undergoing surgery will actually be diagnosed with ovarian cancer.1 Therefore, the goal of diagnostic evaluation is to exclude malignancy.

Diagnostic evaluation includes:

- imaging

- lab work

- history

- physical findings.

The preferred imaging modality for a pelvic mass in asymptomatic premenopausal and postmenopausal women is transvaginal ultrasonography according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) practice bulletin, which was reaffirmed in 2013.1 “No alternative imaging modality has demonstrated sufficient superiority to transvaginal ultrasonography to justify its routine use.”1

Transvaginal ultrasonography with color Doppler interrogation has demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.86% and a specificity of 0.91% for discriminating between malignant and benign ovarian masses.

Sonographic features that are worrisome for malignancy include:

- Multiple thin septations (if indeterminate, the mass may possibly be benign)

- Thick (> 3 mm), irregular septations

- Focal areas of wall thickening (> 3 mm)

- Mural nodules or papillary projections

- Levine and colleagues note that a cyst with a mural nodule with internal blood flow on color Doppler has the highest likelihood of being malignant2

- Moderate or large amount of ascitic fluid in pelvis (in conjunction with ovarian mass showing the above characteristics)

Various morphology indices have been developed that combine these criteria with ovarian mass volume to determine the preoperative predictive value for malignancy.

In the images that follow, we present 14 cases that demonstrate cystadenoma, low malignant potential tumors, and ovarian neoplasia.

CASE 1. Right ovarian mucinous cystadenoma in 68-year-old woman with uterine prolapse and history of ovarian cyst

CASE 2. Borderline serous cystadenoma in 56-year-old woman with right lower quadrant pain, nausea, and loss of appetite

CASE 3. Mucinous cystadenoma in 38-year-old woman undergoing sonography for spontaneous abortion

CASE 4. Mucinous cystadenoma in 54-year-old woman undergoing follow-up ultrasound for persistent ovarian cyst

CASE 7. Mature cystic teratoma in 31-year-old woman with progressively heavier bleeding and pelvic pain

CASE 11. Sex-cord stromal tumor in 61-year-old woman with postmenopausal bleeding

CASE 12. Juvenile granulosa cell tumor in 19-year-old patient with secondary amenorrhea

CASE 14. Mucinous borderline tumor in 55-year-old woman with pelvic discomfort

Which vaginal procedure is best for uterine prolapse?

More than one-third of women aged 45 years or older experience uterine prolapse, a condition that can impair physical, psychological, and sexual function. To compare vaginal vault suspension with hysterectomy, investigators at 4 large Dutch teaching hospitals from 2009 to 2012 randomly assigned women with uterine prolapse to sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSLF) or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS). The primary outcome was recurrent stage 2 or greater prolapse (within 1 cm or more of the hymenal ring) with bothersome bulge symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse by 12 months follow-up.

Details of the trialOne hundred two women assigned to SSLF (median age, 62.7 years) and 100 assigned to hysterectomy with ULS (median age, 61.9 years) were analyzed for the primary outcome. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 85 years.

Surgical failure rates and adverse events were similarMean hospital stay was 3 days in both groups and the occurrence of urinary retention was likewise similar (15% for SSLF and 11% for hysterectomy with ULS). At 12 months, 0 and 4 women in the SSLF and hysterectomy with ULS groups, respectively, met the primary outcome. Study participants were considered a “surgical failure” if any type of prolapse with bothersome symptoms or repeat surgery or pessary use occurred. Failures occurred in approximately one-half of the women in both groups.

Rates of serious adverse events were low, and none were related to type of surgery. Nine women experienced buttock pain following SSLF hysteropexy, a known complication of this surgery. This pain resolved within 6 weeks in 8 of these women. In the remaining woman, persistent pain led to release of the hysteropexy suture and vaginal hysterectomy 4 months after her initial procedure.

What this evidence means for practice

Advantages of hysterectomy at the time of vaginal vault suspension include prevention of endometrial and cervical cancers as well as elimination of uterine bleeding. However, data from published surveys indicate that many US women with prolapse prefer to avoid hysterectomy if effective alternate surgeries are available.1

In the previously published 2014 Barber and colleagues’ OPTIMAL trial,1,2 the efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with either SSLF or USL was equivalent (63.1% versus 64.5%, respectively). The success rates are lower for both procedures in this trial by Detollenaere and colleagues.

Both SSLF and ULS may result in life-altering buttock or leg pain, necessitating removal of the offending sutures; however, the ULS procedure offers a more anatomically correct result. Although the short follow-up interval represents a limitation, these trial results suggest that sacrospinous fixation without hysterectomy represents a reasonable option for women with bothersome uterine prolapse who would like to avoid hysterectomy.

—Meadow M. Good, DO, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Korbly N, Kassis N, Good MM, et al. Patient preference for uterine preservation in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a fellow’s pelvic network research study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1−e6.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse. The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

More than one-third of women aged 45 years or older experience uterine prolapse, a condition that can impair physical, psychological, and sexual function. To compare vaginal vault suspension with hysterectomy, investigators at 4 large Dutch teaching hospitals from 2009 to 2012 randomly assigned women with uterine prolapse to sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSLF) or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS). The primary outcome was recurrent stage 2 or greater prolapse (within 1 cm or more of the hymenal ring) with bothersome bulge symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse by 12 months follow-up.

Details of the trialOne hundred two women assigned to SSLF (median age, 62.7 years) and 100 assigned to hysterectomy with ULS (median age, 61.9 years) were analyzed for the primary outcome. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 85 years.

Surgical failure rates and adverse events were similarMean hospital stay was 3 days in both groups and the occurrence of urinary retention was likewise similar (15% for SSLF and 11% for hysterectomy with ULS). At 12 months, 0 and 4 women in the SSLF and hysterectomy with ULS groups, respectively, met the primary outcome. Study participants were considered a “surgical failure” if any type of prolapse with bothersome symptoms or repeat surgery or pessary use occurred. Failures occurred in approximately one-half of the women in both groups.

Rates of serious adverse events were low, and none were related to type of surgery. Nine women experienced buttock pain following SSLF hysteropexy, a known complication of this surgery. This pain resolved within 6 weeks in 8 of these women. In the remaining woman, persistent pain led to release of the hysteropexy suture and vaginal hysterectomy 4 months after her initial procedure.

What this evidence means for practice

Advantages of hysterectomy at the time of vaginal vault suspension include prevention of endometrial and cervical cancers as well as elimination of uterine bleeding. However, data from published surveys indicate that many US women with prolapse prefer to avoid hysterectomy if effective alternate surgeries are available.1

In the previously published 2014 Barber and colleagues’ OPTIMAL trial,1,2 the efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with either SSLF or USL was equivalent (63.1% versus 64.5%, respectively). The success rates are lower for both procedures in this trial by Detollenaere and colleagues.

Both SSLF and ULS may result in life-altering buttock or leg pain, necessitating removal of the offending sutures; however, the ULS procedure offers a more anatomically correct result. Although the short follow-up interval represents a limitation, these trial results suggest that sacrospinous fixation without hysterectomy represents a reasonable option for women with bothersome uterine prolapse who would like to avoid hysterectomy.

—Meadow M. Good, DO, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

More than one-third of women aged 45 years or older experience uterine prolapse, a condition that can impair physical, psychological, and sexual function. To compare vaginal vault suspension with hysterectomy, investigators at 4 large Dutch teaching hospitals from 2009 to 2012 randomly assigned women with uterine prolapse to sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSLF) or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS). The primary outcome was recurrent stage 2 or greater prolapse (within 1 cm or more of the hymenal ring) with bothersome bulge symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse by 12 months follow-up.

Details of the trialOne hundred two women assigned to SSLF (median age, 62.7 years) and 100 assigned to hysterectomy with ULS (median age, 61.9 years) were analyzed for the primary outcome. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 85 years.

Surgical failure rates and adverse events were similarMean hospital stay was 3 days in both groups and the occurrence of urinary retention was likewise similar (15% for SSLF and 11% for hysterectomy with ULS). At 12 months, 0 and 4 women in the SSLF and hysterectomy with ULS groups, respectively, met the primary outcome. Study participants were considered a “surgical failure” if any type of prolapse with bothersome symptoms or repeat surgery or pessary use occurred. Failures occurred in approximately one-half of the women in both groups.

Rates of serious adverse events were low, and none were related to type of surgery. Nine women experienced buttock pain following SSLF hysteropexy, a known complication of this surgery. This pain resolved within 6 weeks in 8 of these women. In the remaining woman, persistent pain led to release of the hysteropexy suture and vaginal hysterectomy 4 months after her initial procedure.

What this evidence means for practice

Advantages of hysterectomy at the time of vaginal vault suspension include prevention of endometrial and cervical cancers as well as elimination of uterine bleeding. However, data from published surveys indicate that many US women with prolapse prefer to avoid hysterectomy if effective alternate surgeries are available.1

In the previously published 2014 Barber and colleagues’ OPTIMAL trial,1,2 the efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with either SSLF or USL was equivalent (63.1% versus 64.5%, respectively). The success rates are lower for both procedures in this trial by Detollenaere and colleagues.

Both SSLF and ULS may result in life-altering buttock or leg pain, necessitating removal of the offending sutures; however, the ULS procedure offers a more anatomically correct result. Although the short follow-up interval represents a limitation, these trial results suggest that sacrospinous fixation without hysterectomy represents a reasonable option for women with bothersome uterine prolapse who would like to avoid hysterectomy.

—Meadow M. Good, DO, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Korbly N, Kassis N, Good MM, et al. Patient preference for uterine preservation in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a fellow’s pelvic network research study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1−e6.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse. The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

- Korbly N, Kassis N, Good MM, et al. Patient preference for uterine preservation in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a fellow’s pelvic network research study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1−e6.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse. The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

Does the injection of ketorolac prior to IUD placement reduce pain?

Although the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs) is increasing, these highly effective contraceptives remain underutilized in the United States, compared with other developed countries. Concerns about pain with insertion represent one barrier to use.

In a double-blind trial, Ngo and colleagues randomly assigned women presenting for first-time IUD placement from 2012 to 2014 to either:

- ketorolac, a potent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (1-mL gluteal intramuscular injection of 30 mg of ketorolac) or

- saline (1-mL saline intramuscular injection).

The injection was given 30 minutes prior to IUD placement.

Pain associated with injection of the study drug, speculum and tenaculum placement, uterine sounding, IUD placement, and postinsertion pain were measured using a visual analog scale from 0 cm (no pain) to 10 cm (worst pain possible).

Of 67 participants (mean age, approximately 27 years; white race, 33%; African-American race, 33%; median parity, 1), pain was similar between ketorolac and placebo arms for all parameters except postinsertion pain, which was 0 cm and 1.3 cm for ketorolac and placebo, respectively, 15 minutes after placement (P<.001).

Although approximately 75% of participants reported that pain from the injection was “not as bad” as the pain from IUD placement, about 1 in 5 indicated that injection pain was equivalent to pain from IUD placement. Regardless of study group allocation, more than 90% of participants reported being satisfied or very satisfied with IUD placement overall, and more than 75% said they would recommend IUD placement to a friend.

More than 90% of women were satisfied with IUD placement, regardless of study allocation

As Ngo and colleagues observe, the analgesic effect of ketorolac peaks 1 to 2 hours after injection. This observation may explain why pain reduction was noted only after IUD insertion. Although ketorolac is not expensive, logistic considerations may make its routine use prior to IUD placement unrealistic in many ambulatory settings. Further, the great majority of participants (>90%) reported being satisfied with their IUD placement experience overall, regardless of study allocation.

Earlier studies suggesting that preplacement oral NSAIDs are ineffective in reducing placement pain involved the administration of analgesia in the clinic less than 1 hour before IUD insertion. I agree with Ngo and colleagues that future trials of oral NSAIDs should focus on administration of the medication prior to arrival at the clinic.

What this evidence means for practice

Findings from this randomized controlled trial provide only limited support for injection of an NSAID prior to IUD placement.

--Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Although the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs) is increasing, these highly effective contraceptives remain underutilized in the United States, compared with other developed countries. Concerns about pain with insertion represent one barrier to use.

In a double-blind trial, Ngo and colleagues randomly assigned women presenting for first-time IUD placement from 2012 to 2014 to either:

- ketorolac, a potent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (1-mL gluteal intramuscular injection of 30 mg of ketorolac) or

- saline (1-mL saline intramuscular injection).

The injection was given 30 minutes prior to IUD placement.

Pain associated with injection of the study drug, speculum and tenaculum placement, uterine sounding, IUD placement, and postinsertion pain were measured using a visual analog scale from 0 cm (no pain) to 10 cm (worst pain possible).

Of 67 participants (mean age, approximately 27 years; white race, 33%; African-American race, 33%; median parity, 1), pain was similar between ketorolac and placebo arms for all parameters except postinsertion pain, which was 0 cm and 1.3 cm for ketorolac and placebo, respectively, 15 minutes after placement (P<.001).

Although approximately 75% of participants reported that pain from the injection was “not as bad” as the pain from IUD placement, about 1 in 5 indicated that injection pain was equivalent to pain from IUD placement. Regardless of study group allocation, more than 90% of participants reported being satisfied or very satisfied with IUD placement overall, and more than 75% said they would recommend IUD placement to a friend.

More than 90% of women were satisfied with IUD placement, regardless of study allocation

As Ngo and colleagues observe, the analgesic effect of ketorolac peaks 1 to 2 hours after injection. This observation may explain why pain reduction was noted only after IUD insertion. Although ketorolac is not expensive, logistic considerations may make its routine use prior to IUD placement unrealistic in many ambulatory settings. Further, the great majority of participants (>90%) reported being satisfied with their IUD placement experience overall, regardless of study allocation.

Earlier studies suggesting that preplacement oral NSAIDs are ineffective in reducing placement pain involved the administration of analgesia in the clinic less than 1 hour before IUD insertion. I agree with Ngo and colleagues that future trials of oral NSAIDs should focus on administration of the medication prior to arrival at the clinic.

What this evidence means for practice

Findings from this randomized controlled trial provide only limited support for injection of an NSAID prior to IUD placement.

--Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Although the use of intrauterine devices (IUDs) is increasing, these highly effective contraceptives remain underutilized in the United States, compared with other developed countries. Concerns about pain with insertion represent one barrier to use.

In a double-blind trial, Ngo and colleagues randomly assigned women presenting for first-time IUD placement from 2012 to 2014 to either:

- ketorolac, a potent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (1-mL gluteal intramuscular injection of 30 mg of ketorolac) or

- saline (1-mL saline intramuscular injection).

The injection was given 30 minutes prior to IUD placement.

Pain associated with injection of the study drug, speculum and tenaculum placement, uterine sounding, IUD placement, and postinsertion pain were measured using a visual analog scale from 0 cm (no pain) to 10 cm (worst pain possible).

Of 67 participants (mean age, approximately 27 years; white race, 33%; African-American race, 33%; median parity, 1), pain was similar between ketorolac and placebo arms for all parameters except postinsertion pain, which was 0 cm and 1.3 cm for ketorolac and placebo, respectively, 15 minutes after placement (P<.001).

Although approximately 75% of participants reported that pain from the injection was “not as bad” as the pain from IUD placement, about 1 in 5 indicated that injection pain was equivalent to pain from IUD placement. Regardless of study group allocation, more than 90% of participants reported being satisfied or very satisfied with IUD placement overall, and more than 75% said they would recommend IUD placement to a friend.

More than 90% of women were satisfied with IUD placement, regardless of study allocation

As Ngo and colleagues observe, the analgesic effect of ketorolac peaks 1 to 2 hours after injection. This observation may explain why pain reduction was noted only after IUD insertion. Although ketorolac is not expensive, logistic considerations may make its routine use prior to IUD placement unrealistic in many ambulatory settings. Further, the great majority of participants (>90%) reported being satisfied with their IUD placement experience overall, regardless of study allocation.

Earlier studies suggesting that preplacement oral NSAIDs are ineffective in reducing placement pain involved the administration of analgesia in the clinic less than 1 hour before IUD insertion. I agree with Ngo and colleagues that future trials of oral NSAIDs should focus on administration of the medication prior to arrival at the clinic.

What this evidence means for practice

Findings from this randomized controlled trial provide only limited support for injection of an NSAID prior to IUD placement.

--Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

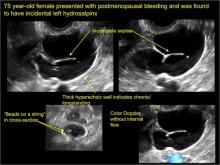

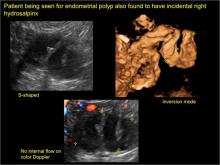

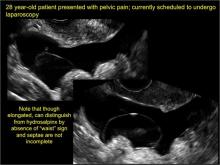

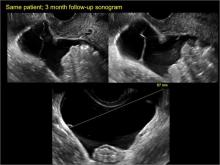

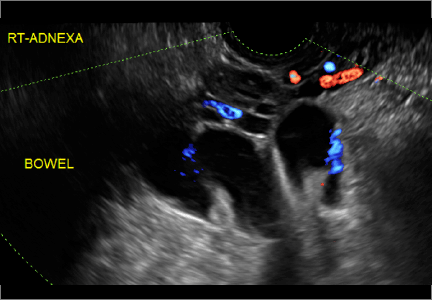

“Cogwheel” and other signs of hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts

Ultrasonography is the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts. Most types of pelvic cyst pathology have characteristic findings that, when identified, can guide counseling and management decisions. For instance, simple cysts have thin walls, are uniformly hypoechoic, and show no blood flow on color Doppler. Endometriomas, on the other hand, demonstrate diffuse, low-level internal echoes on ultrasonography.

In parts 1 and 2 of this 4-part series on adnexal pathology, we presented images detailing common benign adnexal cysts, including:

- simple and hemorrhagic cysts (Part 1:Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts)

- and mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) and endometriomas (Part 2: Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma).

In this part 3, we detail imaging for hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts. In part 4 we will consider cystadenomas and ovarian neoplasias.

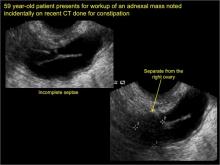

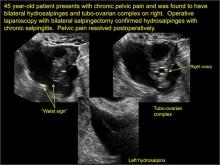

hydrosalpinx

These cysts are caused by fimbrial obstruction and result in tubal distention with serous fluid. A hydrosalpinx may occur following an episode of salpingitis or pelvic surgery.

Sonographic features diagnostic for hydrosalpinx include a tubular or S-shaped cystic mass separate from the ovary, with:

- “beads on a string” or “cogwheel” appearance (small round nodules less than 3 mm in size that represent endosalpingeal folds when viewed in cross section)

- “waist sign” (indentations on opposite sides)

- incomplete septations, which result from segments of distended tube folding over/adhering to other tubal segments

Levine and colleagues noted that 3-dimensional imaging may be helpful when the diagnosis is uncertain.1

When a mass is noted that has features classic for hydrosalpinx, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommends1:

- no further imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis

- frequency of follow-up imaging should be based on the patient’s age and clinical symptoms

In FIGURES 1 through 6 below (slides of image collections), we present 5 cases, including one of a 45-year-old patient presenting with chronic pelvic pain who was found to have bilateral hydrosalginges and right-sided tubo-ovarian complex.

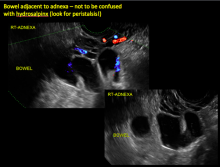

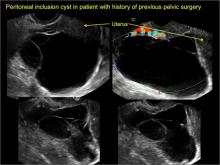

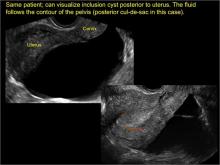

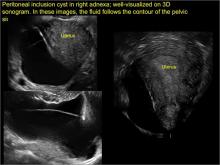

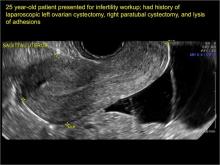

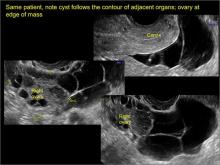

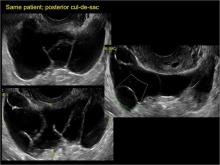

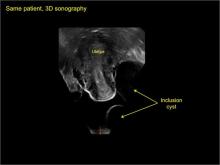

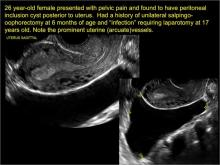

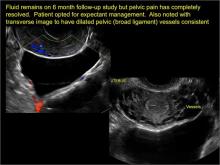

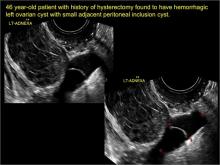

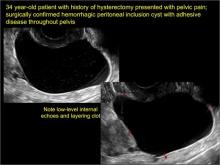

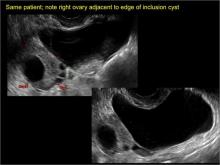

pelvic inclusion cysts

Pelvic/peritoneal inclusion cysts, or peritoneal pseudocysts, are typically associated with factors that increase the risk for pelvic adhesive disease (including endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or prior pelvic surgery).

Classic sonographic features of pelvic inclusion cysts are:

- cystic mass, usually with septations/loculations

- the mass follows the contour of adjacent organs

- ovary at edge of the mass or sometimes suspended within it

- with or without flow in septation on color Doppler

When a mass is noted that has features classic for a peritoneal inclusion cyst, the US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommends that1:

- no further imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis (although further imaging may be needed if the diagnosis is uncertain)

- the frequency of follow-up imaging should be based on the patient’s age and clinical symptoms

In FIGURES 7 through 22 below (slides of image collections), we present several cases that demonstrate pelvic inclusion cysts on imaging. One case involves a 25-year-old patient presenting for 2- and 3-dimensional pelvic imaging due to infertility. She had a history of laparoscopic left ovarian cystectomy, right paratubal cystectomy, and lysis of adhesions. She was found to have a pelvic inclusion cyst and an endometrioma in the left ovary.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Ultrasound Q. 2010;26(3):121−131.

Ultrasonography is the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts. Most types of pelvic cyst pathology have characteristic findings that, when identified, can guide counseling and management decisions. For instance, simple cysts have thin walls, are uniformly hypoechoic, and show no blood flow on color Doppler. Endometriomas, on the other hand, demonstrate diffuse, low-level internal echoes on ultrasonography.

In parts 1 and 2 of this 4-part series on adnexal pathology, we presented images detailing common benign adnexal cysts, including:

- simple and hemorrhagic cysts (Part 1:Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts)

- and mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) and endometriomas (Part 2: Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma).

In this part 3, we detail imaging for hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts. In part 4 we will consider cystadenomas and ovarian neoplasias.

hydrosalpinx

These cysts are caused by fimbrial obstruction and result in tubal distention with serous fluid. A hydrosalpinx may occur following an episode of salpingitis or pelvic surgery.

Sonographic features diagnostic for hydrosalpinx include a tubular or S-shaped cystic mass separate from the ovary, with:

- “beads on a string” or “cogwheel” appearance (small round nodules less than 3 mm in size that represent endosalpingeal folds when viewed in cross section)

- “waist sign” (indentations on opposite sides)

- incomplete septations, which result from segments of distended tube folding over/adhering to other tubal segments

Levine and colleagues noted that 3-dimensional imaging may be helpful when the diagnosis is uncertain.1

When a mass is noted that has features classic for hydrosalpinx, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommends1:

- no further imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis

- frequency of follow-up imaging should be based on the patient’s age and clinical symptoms

In FIGURES 1 through 6 below (slides of image collections), we present 5 cases, including one of a 45-year-old patient presenting with chronic pelvic pain who was found to have bilateral hydrosalginges and right-sided tubo-ovarian complex.

pelvic inclusion cysts

Pelvic/peritoneal inclusion cysts, or peritoneal pseudocysts, are typically associated with factors that increase the risk for pelvic adhesive disease (including endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or prior pelvic surgery).

Classic sonographic features of pelvic inclusion cysts are:

- cystic mass, usually with septations/loculations

- the mass follows the contour of adjacent organs

- ovary at edge of the mass or sometimes suspended within it

- with or without flow in septation on color Doppler

When a mass is noted that has features classic for a peritoneal inclusion cyst, the US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommends that1:

- no further imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis (although further imaging may be needed if the diagnosis is uncertain)

- the frequency of follow-up imaging should be based on the patient’s age and clinical symptoms

In FIGURES 7 through 22 below (slides of image collections), we present several cases that demonstrate pelvic inclusion cysts on imaging. One case involves a 25-year-old patient presenting for 2- and 3-dimensional pelvic imaging due to infertility. She had a history of laparoscopic left ovarian cystectomy, right paratubal cystectomy, and lysis of adhesions. She was found to have a pelvic inclusion cyst and an endometrioma in the left ovary.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Ultrasonography is the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts. Most types of pelvic cyst pathology have characteristic findings that, when identified, can guide counseling and management decisions. For instance, simple cysts have thin walls, are uniformly hypoechoic, and show no blood flow on color Doppler. Endometriomas, on the other hand, demonstrate diffuse, low-level internal echoes on ultrasonography.

In parts 1 and 2 of this 4-part series on adnexal pathology, we presented images detailing common benign adnexal cysts, including:

- simple and hemorrhagic cysts (Part 1:Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts)

- and mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) and endometriomas (Part 2: Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma).

In this part 3, we detail imaging for hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts. In part 4 we will consider cystadenomas and ovarian neoplasias.

hydrosalpinx

These cysts are caused by fimbrial obstruction and result in tubal distention with serous fluid. A hydrosalpinx may occur following an episode of salpingitis or pelvic surgery.

Sonographic features diagnostic for hydrosalpinx include a tubular or S-shaped cystic mass separate from the ovary, with:

- “beads on a string” or “cogwheel” appearance (small round nodules less than 3 mm in size that represent endosalpingeal folds when viewed in cross section)

- “waist sign” (indentations on opposite sides)

- incomplete septations, which result from segments of distended tube folding over/adhering to other tubal segments

Levine and colleagues noted that 3-dimensional imaging may be helpful when the diagnosis is uncertain.1

When a mass is noted that has features classic for hydrosalpinx, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommends1:

- no further imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis

- frequency of follow-up imaging should be based on the patient’s age and clinical symptoms

In FIGURES 1 through 6 below (slides of image collections), we present 5 cases, including one of a 45-year-old patient presenting with chronic pelvic pain who was found to have bilateral hydrosalginges and right-sided tubo-ovarian complex.

pelvic inclusion cysts

Pelvic/peritoneal inclusion cysts, or peritoneal pseudocysts, are typically associated with factors that increase the risk for pelvic adhesive disease (including endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or prior pelvic surgery).

Classic sonographic features of pelvic inclusion cysts are:

- cystic mass, usually with septations/loculations

- the mass follows the contour of adjacent organs

- ovary at edge of the mass or sometimes suspended within it

- with or without flow in septation on color Doppler

When a mass is noted that has features classic for a peritoneal inclusion cyst, the US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommends that1:

- no further imaging is necessary to establish the diagnosis (although further imaging may be needed if the diagnosis is uncertain)

- the frequency of follow-up imaging should be based on the patient’s age and clinical symptoms

In FIGURES 7 through 22 below (slides of image collections), we present several cases that demonstrate pelvic inclusion cysts on imaging. One case involves a 25-year-old patient presenting for 2- and 3-dimensional pelvic imaging due to infertility. She had a history of laparoscopic left ovarian cystectomy, right paratubal cystectomy, and lysis of adhesions. She was found to have a pelvic inclusion cyst and an endometrioma in the left ovary.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Ultrasound Q. 2010;26(3):121−131.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound consensus conference statement. Ultrasound Q. 2010;26(3):121−131.

Is menopausal hormone therapy safe when your patient carries a BRCA mutation?

Case: Disabling vasomotor symptoms in a BRCA1 mutation carrier

Christine is a 39-year-old mother of 2 who underwent risk-reducing, minimally invasive bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy 4 months ago for a BRCA1 mutation (with benign findings on pathology). Eighteen months before that surgery, she had risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (implants) and was advised by her surgeon that she no longer needs breast imaging.

Today she reports disabling hot flashes, insomnia, vaginal dryness, and painful sex. Her previous ObGyn, who performed the hysterectomy, was unwilling to prescribe hormone therapy (HT) due to safety concerns. Christine tried venlafaxine at 37 to 75 mg but noted little relief of her vasomotor symptoms.

In discussing her symptoms with you during this initial visit, Christine, a practicing accountant, also reveals that she does not feel as intellectually “sharp” as she did before her gynecologic surgery.

What can you offer for relief of her symptoms?

More BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and choosing to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral mastectomy. Accordingly, clinicians are likely to face more questions about the use of systemic HT in this population. Because mutation carriers may worry about the safety of HT, given their BRCA status, some may delay or avoid salpingo-oophorectomy—a surgery that not only reduces the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer by 80% but also decreases the risk of breast cancer by 48%.1

Surgically menopausal women in their 30s or 40s who are not treated with HT appear to have an elevated risk for dementia and Parkinsonism.2 In addition, vasomotor symptoms are often more severe, and the risks for osteoporosis and, likely, cardiovascular disease are elevated in women with early menopause who are not treated with HT. For these reasons, systemic HT is recommended for women with early menopause, and generally should be continued at least until the normal age of menopause unless specific contraindications are present.3

Because Christine not only has had risk-reducing gynecologic surgery but also risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, her current risk for breast cancer is very low whether or not she uses HT. Because she does not have a uterus, her symptoms can effectively and safely be treated with systemic estrogen-only therapy.

Among clinicians with special expertise in the management of BRCA mutation carriers, the use of systemic HT would be considered appropriate—and not controversial—in this setting.4

Angelina Jolie details her surgeries

In March 2015, 39-year-old Oscar-winning actress and filmmaker Angelina Jolie Pitt published an opinion piece in the New York Times detailing her recent laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and initiation of HT.5 Ms. Jolie Pitt, who carries the BRCA1 mutation, lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Two years earlier, Ms. Jolie Pitt made news by describing her decision to move ahead with risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Following her risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, she initiated systemic HT using transdermal estradiol and off-label use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection.

Her courageous decision to publicly describe her surgery and subsequent initiation of systemic HT will likely encourage women with ominous family histories to seek out genetic counseling and testing. Her decision to “go public” regarding surgery should help mutation carriers without a history of cancer (known in the BRCA community as “previvors”) who have completed their families to move forward with risk-reducing gynecologic surgery and, when appropriate, use of systemic HT.6

The outlook for previvors with intact breasts

Three studies address the risk of breast cancer with use of systemic HT among previvors with intact breasts. A 2005 study followed a cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts, 155 of whom had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, for a mean of 3.6 years. Of these women, 60% and 7%, respectively, of those who had and had not undergone salpingo-oophorectomy used HT. The authors noted that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduced the risk of breast cancer by some 60%, whether or not women used HT.7

A 2008 case-control study focused on 472 menopausal BRCA1 carriers, half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer (cases); the other half had not received this diagnosis (controls). A 43% reduction in the risk of breast cancer was associated with prior use of HT.8

A 2011 presentation described a cohort study in which 1,299 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts who had undergone salpingo-oophorectomy were followed for a mean of 5.4 years postoperatively. In this population, use of HT was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Among women with BRCA1 mutations, use of systemic HT was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer.9

Viewed in aggregate, these studies reassure us that short-term use of systemic HT does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.

Dr. Simon

Nevertheless, I think it is important to point out that a properly powered study to assess actual risk in this setting is not available in the literature.

When a patient refuses HT

Dr. Pinkerton

Some BRCA mutation carriers may refuse HT despite reassurance that it is safe. Nonhormonal therapies are not as effective at relieving severe menopausal symptoms. Almost all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be offered, although only low-dose paroxetine salt is approved for treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes.10,11 Gabapentin also has shown efficacy in relieving hot flashes.

For genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; formerly known as vulvovaginal atrophy), lubricants and moisturizers may provide some benefit, but they don’t improve the vaginal superficial cells and, therefore, are not as effective as hormonal options. There is now a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved to treat GSM—ospemifene. However, in clinical trials, ospemifene has been shown to increase hot flashes, so it would not be a good option for our patient.12

Case: Continued

Christine follows up 3 months after initiating estrogen therapy (oral estradiol 2 mg daily). She reports significant improvement in her hot flashes, with improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions. In addition, she feels that her “mental sharpness” has returned.

Dr. Pinkerton

What if this patient had an intact uterus? Then she would not be a candidate for estrogen-only therapy because she would need continued endometrial protection. Options then would include low-dose continuous or cyclic progestogen therapy, often starting with micronized progesterone, as the E3N Study suggested it has a less negative effect on the uterus.13 Or she could use a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system off label, as Ms. Jolie Pitt elected to do.

Another option would be combining estrogen with a SERM. The only estrogen/SERM combination currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conjugated estrogen/bazedoxefine, which showed no increase in breast tenderness, breast density, or bleeding rates, compared with placebo, in multiple trials up to 5 years in duration.14

Case: Resolved

Christine says she would like to continue HT, although she still experiences dryness and discomfort when sexually active with her husband, despite use of a vaginal lubricant. A pelvic examination is consistent with early changes of GSM.15

You discuss GSM with Christine and suggest that she consider 1 of 2 strategies:

- Switch from daily use of oral estradiol to the 3-month systemic 0.1-mg estradiol ring (Femring), which would address both her vasomotor symptoms and her GSM.

- Continue oral estradiol and add low-dose vaginal estrogen (cream, tablets, or Estring 2 mg).

Christine chooses Option 2. When she returns 6 months later for her well-woman visit, she reports that all of her menopausal symptoms have resolved, and a pelvic examination no longer reveals changes of GSM.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–1553.

2. Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007;69(11):1074–1083.

3. North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

4. Finch AP, Evans G, Narod SA. BRCA carriers, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and menopause: clinical management considerations and recommendations. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8(5):543–555.

5. Pitt AJ. Angelina Jolie Pitt: Diary of a Surgery. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html. Published March 24, 2015. Accessed July 9, 2015.

6. Holman L, Brandt A, Daniels M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy among BRCA mutation “previvors.” Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1 suppl):S17.

7. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7804–7810.

8. Eisen A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1361–1367.

9. Domchek SM, Mitchell G, Lindeman GJ, et al. Challenges to the development of new agents for molecularly defined patient subsets: lessons from BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4224–4226.

10. Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):163–179.

11. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1030.

12. Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

13. Fournier A, Fabre A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor–defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260–1268.

14. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

15. Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

Angelina Jolie, previvors, systemic HT, nonhormonal therapy, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, SNRIs, paroxetine salt, gabapentin, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, GSM, vaginal lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, selective estrogen receptor modulator, SERM, ospemifene, estrogen therapy, oral estradiol, endometrial protection, progestogen therapy, micronized progesterone,

Case: Disabling vasomotor symptoms in a BRCA1 mutation carrier

Christine is a 39-year-old mother of 2 who underwent risk-reducing, minimally invasive bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy 4 months ago for a BRCA1 mutation (with benign findings on pathology). Eighteen months before that surgery, she had risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (implants) and was advised by her surgeon that she no longer needs breast imaging.

Today she reports disabling hot flashes, insomnia, vaginal dryness, and painful sex. Her previous ObGyn, who performed the hysterectomy, was unwilling to prescribe hormone therapy (HT) due to safety concerns. Christine tried venlafaxine at 37 to 75 mg but noted little relief of her vasomotor symptoms.

In discussing her symptoms with you during this initial visit, Christine, a practicing accountant, also reveals that she does not feel as intellectually “sharp” as she did before her gynecologic surgery.

What can you offer for relief of her symptoms?

More BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and choosing to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral mastectomy. Accordingly, clinicians are likely to face more questions about the use of systemic HT in this population. Because mutation carriers may worry about the safety of HT, given their BRCA status, some may delay or avoid salpingo-oophorectomy—a surgery that not only reduces the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer by 80% but also decreases the risk of breast cancer by 48%.1

Surgically menopausal women in their 30s or 40s who are not treated with HT appear to have an elevated risk for dementia and Parkinsonism.2 In addition, vasomotor symptoms are often more severe, and the risks for osteoporosis and, likely, cardiovascular disease are elevated in women with early menopause who are not treated with HT. For these reasons, systemic HT is recommended for women with early menopause, and generally should be continued at least until the normal age of menopause unless specific contraindications are present.3

Because Christine not only has had risk-reducing gynecologic surgery but also risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, her current risk for breast cancer is very low whether or not she uses HT. Because she does not have a uterus, her symptoms can effectively and safely be treated with systemic estrogen-only therapy.

Among clinicians with special expertise in the management of BRCA mutation carriers, the use of systemic HT would be considered appropriate—and not controversial—in this setting.4

Angelina Jolie details her surgeries

In March 2015, 39-year-old Oscar-winning actress and filmmaker Angelina Jolie Pitt published an opinion piece in the New York Times detailing her recent laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and initiation of HT.5 Ms. Jolie Pitt, who carries the BRCA1 mutation, lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Two years earlier, Ms. Jolie Pitt made news by describing her decision to move ahead with risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Following her risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, she initiated systemic HT using transdermal estradiol and off-label use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection.

Her courageous decision to publicly describe her surgery and subsequent initiation of systemic HT will likely encourage women with ominous family histories to seek out genetic counseling and testing. Her decision to “go public” regarding surgery should help mutation carriers without a history of cancer (known in the BRCA community as “previvors”) who have completed their families to move forward with risk-reducing gynecologic surgery and, when appropriate, use of systemic HT.6

The outlook for previvors with intact breasts

Three studies address the risk of breast cancer with use of systemic HT among previvors with intact breasts. A 2005 study followed a cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts, 155 of whom had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, for a mean of 3.6 years. Of these women, 60% and 7%, respectively, of those who had and had not undergone salpingo-oophorectomy used HT. The authors noted that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduced the risk of breast cancer by some 60%, whether or not women used HT.7

A 2008 case-control study focused on 472 menopausal BRCA1 carriers, half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer (cases); the other half had not received this diagnosis (controls). A 43% reduction in the risk of breast cancer was associated with prior use of HT.8

A 2011 presentation described a cohort study in which 1,299 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts who had undergone salpingo-oophorectomy were followed for a mean of 5.4 years postoperatively. In this population, use of HT was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Among women with BRCA1 mutations, use of systemic HT was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer.9

Viewed in aggregate, these studies reassure us that short-term use of systemic HT does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.

Dr. Simon

Nevertheless, I think it is important to point out that a properly powered study to assess actual risk in this setting is not available in the literature.

When a patient refuses HT

Dr. Pinkerton

Some BRCA mutation carriers may refuse HT despite reassurance that it is safe. Nonhormonal therapies are not as effective at relieving severe menopausal symptoms. Almost all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be offered, although only low-dose paroxetine salt is approved for treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes.10,11 Gabapentin also has shown efficacy in relieving hot flashes.

For genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; formerly known as vulvovaginal atrophy), lubricants and moisturizers may provide some benefit, but they don’t improve the vaginal superficial cells and, therefore, are not as effective as hormonal options. There is now a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved to treat GSM—ospemifene. However, in clinical trials, ospemifene has been shown to increase hot flashes, so it would not be a good option for our patient.12

Case: Continued

Christine follows up 3 months after initiating estrogen therapy (oral estradiol 2 mg daily). She reports significant improvement in her hot flashes, with improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions. In addition, she feels that her “mental sharpness” has returned.

Dr. Pinkerton

What if this patient had an intact uterus? Then she would not be a candidate for estrogen-only therapy because she would need continued endometrial protection. Options then would include low-dose continuous or cyclic progestogen therapy, often starting with micronized progesterone, as the E3N Study suggested it has a less negative effect on the uterus.13 Or she could use a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system off label, as Ms. Jolie Pitt elected to do.

Another option would be combining estrogen with a SERM. The only estrogen/SERM combination currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conjugated estrogen/bazedoxefine, which showed no increase in breast tenderness, breast density, or bleeding rates, compared with placebo, in multiple trials up to 5 years in duration.14

Case: Resolved

Christine says she would like to continue HT, although she still experiences dryness and discomfort when sexually active with her husband, despite use of a vaginal lubricant. A pelvic examination is consistent with early changes of GSM.15

You discuss GSM with Christine and suggest that she consider 1 of 2 strategies:

- Switch from daily use of oral estradiol to the 3-month systemic 0.1-mg estradiol ring (Femring), which would address both her vasomotor symptoms and her GSM.

- Continue oral estradiol and add low-dose vaginal estrogen (cream, tablets, or Estring 2 mg).

Christine chooses Option 2. When she returns 6 months later for her well-woman visit, she reports that all of her menopausal symptoms have resolved, and a pelvic examination no longer reveals changes of GSM.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Case: Disabling vasomotor symptoms in a BRCA1 mutation carrier

Christine is a 39-year-old mother of 2 who underwent risk-reducing, minimally invasive bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with hysterectomy 4 months ago for a BRCA1 mutation (with benign findings on pathology). Eighteen months before that surgery, she had risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy with reconstruction (implants) and was advised by her surgeon that she no longer needs breast imaging.

Today she reports disabling hot flashes, insomnia, vaginal dryness, and painful sex. Her previous ObGyn, who performed the hysterectomy, was unwilling to prescribe hormone therapy (HT) due to safety concerns. Christine tried venlafaxine at 37 to 75 mg but noted little relief of her vasomotor symptoms.

In discussing her symptoms with you during this initial visit, Christine, a practicing accountant, also reveals that she does not feel as intellectually “sharp” as she did before her gynecologic surgery.

What can you offer for relief of her symptoms?

More BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and choosing to undergo risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral mastectomy. Accordingly, clinicians are likely to face more questions about the use of systemic HT in this population. Because mutation carriers may worry about the safety of HT, given their BRCA status, some may delay or avoid salpingo-oophorectomy—a surgery that not only reduces the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer by 80% but also decreases the risk of breast cancer by 48%.1

Surgically menopausal women in their 30s or 40s who are not treated with HT appear to have an elevated risk for dementia and Parkinsonism.2 In addition, vasomotor symptoms are often more severe, and the risks for osteoporosis and, likely, cardiovascular disease are elevated in women with early menopause who are not treated with HT. For these reasons, systemic HT is recommended for women with early menopause, and generally should be continued at least until the normal age of menopause unless specific contraindications are present.3

Because Christine not only has had risk-reducing gynecologic surgery but also risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, her current risk for breast cancer is very low whether or not she uses HT. Because she does not have a uterus, her symptoms can effectively and safely be treated with systemic estrogen-only therapy.

Among clinicians with special expertise in the management of BRCA mutation carriers, the use of systemic HT would be considered appropriate—and not controversial—in this setting.4

Angelina Jolie details her surgeries

In March 2015, 39-year-old Oscar-winning actress and filmmaker Angelina Jolie Pitt published an opinion piece in the New York Times detailing her recent laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy and initiation of HT.5 Ms. Jolie Pitt, who carries the BRCA1 mutation, lost her mother, grandmother, and aunt to hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Two years earlier, Ms. Jolie Pitt made news by describing her decision to move ahead with risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy.

Following her risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, she initiated systemic HT using transdermal estradiol and off-label use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection.

Her courageous decision to publicly describe her surgery and subsequent initiation of systemic HT will likely encourage women with ominous family histories to seek out genetic counseling and testing. Her decision to “go public” regarding surgery should help mutation carriers without a history of cancer (known in the BRCA community as “previvors”) who have completed their families to move forward with risk-reducing gynecologic surgery and, when appropriate, use of systemic HT.6

The outlook for previvors with intact breasts

Three studies address the risk of breast cancer with use of systemic HT among previvors with intact breasts. A 2005 study followed a cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts, 155 of whom had undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, for a mean of 3.6 years. Of these women, 60% and 7%, respectively, of those who had and had not undergone salpingo-oophorectomy used HT. The authors noted that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy reduced the risk of breast cancer by some 60%, whether or not women used HT.7

A 2008 case-control study focused on 472 menopausal BRCA1 carriers, half of whom had been diagnosed with breast cancer (cases); the other half had not received this diagnosis (controls). A 43% reduction in the risk of breast cancer was associated with prior use of HT.8

A 2011 presentation described a cohort study in which 1,299 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers with intact breasts who had undergone salpingo-oophorectomy were followed for a mean of 5.4 years postoperatively. In this population, use of HT was not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Among women with BRCA1 mutations, use of systemic HT was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer.9

Viewed in aggregate, these studies reassure us that short-term use of systemic HT does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.

Dr. Simon

Nevertheless, I think it is important to point out that a properly powered study to assess actual risk in this setting is not available in the literature.

When a patient refuses HT

Dr. Pinkerton

Some BRCA mutation carriers may refuse HT despite reassurance that it is safe. Nonhormonal therapies are not as effective at relieving severe menopausal symptoms. Almost all selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) can be offered, although only low-dose paroxetine salt is approved for treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes.10,11 Gabapentin also has shown efficacy in relieving hot flashes.

For genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM; formerly known as vulvovaginal atrophy), lubricants and moisturizers may provide some benefit, but they don’t improve the vaginal superficial cells and, therefore, are not as effective as hormonal options. There is now a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) approved to treat GSM—ospemifene. However, in clinical trials, ospemifene has been shown to increase hot flashes, so it would not be a good option for our patient.12

Case: Continued

Christine follows up 3 months after initiating estrogen therapy (oral estradiol 2 mg daily). She reports significant improvement in her hot flashes, with improved sleep and fewer sleep disruptions. In addition, she feels that her “mental sharpness” has returned.

Dr. Pinkerton

What if this patient had an intact uterus? Then she would not be a candidate for estrogen-only therapy because she would need continued endometrial protection. Options then would include low-dose continuous or cyclic progestogen therapy, often starting with micronized progesterone, as the E3N Study suggested it has a less negative effect on the uterus.13 Or she could use a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system off label, as Ms. Jolie Pitt elected to do.

Another option would be combining estrogen with a SERM. The only estrogen/SERM combination currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conjugated estrogen/bazedoxefine, which showed no increase in breast tenderness, breast density, or bleeding rates, compared with placebo, in multiple trials up to 5 years in duration.14

Case: Resolved

Christine says she would like to continue HT, although she still experiences dryness and discomfort when sexually active with her husband, despite use of a vaginal lubricant. A pelvic examination is consistent with early changes of GSM.15

You discuss GSM with Christine and suggest that she consider 1 of 2 strategies:

- Switch from daily use of oral estradiol to the 3-month systemic 0.1-mg estradiol ring (Femring), which would address both her vasomotor symptoms and her GSM.

- Continue oral estradiol and add low-dose vaginal estrogen (cream, tablets, or Estring 2 mg).

Christine chooses Option 2. When she returns 6 months later for her well-woman visit, she reports that all of her menopausal symptoms have resolved, and a pelvic examination no longer reveals changes of GSM.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–1553.

2. Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007;69(11):1074–1083.

3. North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

4. Finch AP, Evans G, Narod SA. BRCA carriers, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and menopause: clinical management considerations and recommendations. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8(5):543–555.

5. Pitt AJ. Angelina Jolie Pitt: Diary of a Surgery. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html. Published March 24, 2015. Accessed July 9, 2015.

6. Holman L, Brandt A, Daniels M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy among BRCA mutation “previvors.” Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1 suppl):S17.

7. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7804–7810.

8. Eisen A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1361–1367.

9. Domchek SM, Mitchell G, Lindeman GJ, et al. Challenges to the development of new agents for molecularly defined patient subsets: lessons from BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4224–4226.

10. Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):163–179.

11. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1030.

12. Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

13. Fournier A, Fabre A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor–defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260–1268.

14. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

15. Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV, et al; Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(6):1147–1156.

1. Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1547–1553.

2. Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology. 2007;69(11):1074–1083.

3. North American Menopause Society. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

4. Finch AP, Evans G, Narod SA. BRCA carriers, prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy and menopause: clinical management considerations and recommendations. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2012;8(5):543–555.

5. Pitt AJ. Angelina Jolie Pitt: Diary of a Surgery. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/24/opinion/angelina-jolie-pitt-diary-of-a-surgery.html. Published March 24, 2015. Accessed July 9, 2015.

6. Holman L, Brandt A, Daniels M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy and prophylactic mastectomy among BRCA mutation “previvors.” Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1 suppl):S17.

7. Rebbeck TR, Friebel T, Wagner T, et al; PROSE Study Group. Effect of short-term hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer risk reduction after bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):7804–7810.

8. Eisen A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, et al; Hereditary Breast Cancer Clinical Study Group. Hormone therapy and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(19):1361–1367.

9. Domchek SM, Mitchell G, Lindeman GJ, et al. Challenges to the development of new agents for molecularly defined patient subsets: lessons from BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4224–4226.

10. Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):163–179.

11. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1030.

12. Bachmann GA, Komi JO; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study. Menopause. 2010;17(3):480–486.

13. Fournier A, Fabre A, Mesrine S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Use of different postmenopausal hormone therapies and risk of histology- and hormone receptor–defined invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1260–1268.

14. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.