User login

Asymptomatic Violaceous Plaques on the Face and Back

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

A biopsy of a plaque on the back confirmed cutaneous sarcoidosis (CS). A chest radiograph demonstrated hilar nodes, and a referral was placed for comanagement with a pulmonologist. Histopathology was critical in making the diagnosis, with well-circumscribed noncaseating granulomas present in the dermis. The granulomas in CS often are described as naked, as there are minimal lymphocytes present and plasma cells normally are absent.1 Because the lungs are the most common site of involvement, a chest radiograph is necessary to examine for systemic sarcoidosis. Laboratory workup is used to evaluate for lymphopenia, hypercalcemia, elevated blood sedimentation rate, and elevated angiotensin- converting enzyme levels, which are common in systemic sarcoidosis.1

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disorder with an unknown etiology. It is believed to develop in genetically predisposed individuals as a reaction to unidentified antigens in the environment.1 Helper T cells (TH1) respond to these environmental antigens in those who are susceptible, which leads to the disease process, but paradoxically, even with the elevation of cellular immune activity at the sites of the granulomatous inflammation, the peripheral immune response in these patients is suppressed as shown by lymphopenia.2

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is found in approximately one-third of patients with systemic sarcoidosis but can occur without systemic involvement.1,2 Sarcoidosis is reported worldwide and affects patients of all races and ethnicities, ages, and sexes but does have a higher prevalence among Black individuals in the United States, patients younger than 40 years (peak incidence, 20–29 years of age), and females.2 In 80% of patients, CS occurs before systemic sarcoidosis develops, or they may develop simultaneously.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations that are classified as specific and nonspecific. Specific lesions in CS contain noncaseating granulomas while nonspecific lesions in CS appear as reactive processes.2 The most common specific presentation of CS includes papules that are brown in pigmentation in lighter skin tones and red to violaceous in darker skin tones (Figure). The most common nonspecific skin manifestation is erythema nodosum, which represents a hypersensitivity reaction. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can appear as hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or plaques.1

Treatments for CS vary based on the individual.1 For milder and more localized cases, topical or intralesional steroids may be used. If systemic sarcoidosis is suspected or if there is diffuse involvement of the skin, systemic steroids, antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine), low-dose methotrexate, minocycline, allopurinol, azathioprine, isotretinoin, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, or psoralen plus long-wave UVA radiation may be used. If systemic sarcoidosis is present, referral to a pulmonologist is recommended for co-management.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is known as the “great imitator,” and there are multiple diseases to consider in the differential that are distinguished by the physical findings.1 In our case of a middle-aged Black woman with indurated plaques, a few diagnoses to consider were psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), mycosis fungoides (MF), and tinea infection.

Psoriasis is a common disease, and 90% of patients have chronic plaquelike disease with well-demarcated erythematous plaques that have a silver-gray scale and a positive Auspitz sign (also known as pinpoint bleeding).3 Plaques often are distributed on the trunk, limb extensors, and scalp, along with nail changes. Some patients also have joint pain, indicating psoriatic arthritis. The etiology of psoriasis is unknown, but it develops due to unrestrained keratinocyte proliferation and defective differentiation, which leads to histopathology showing regular acanthosis and papillary dermal ectasia with rouleaux. Mild cases typically are treated with topical steroids or vitamin D, while more severe cases are treated with methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, or biologics.3

Discoid lupus erythematosus occurs 4 times more often in Black patients than in White patients. Clinically, DLE begins as well-defined, erythematous, scaly patches that expand with hyperpigmentation at the periphery and leave an atrophic, scarred, hypopigmented center.4 It typically is localized to the head and neck, but in cases where it disseminates elsewhere on the body, the risk for systemic lupus erythematosus increases from 1.2% to 28%.5 Histopathology of DLE shows vacuolar degeneration of the basal cell layer in the epidermis along with patchy lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Treatments range from topical steroids for mild cases to antimalarial agents, retinoids, anti-inflammatory drugs, and calcineurin inhibitors for more severe cases.4

Although there are multiple types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the most common is MF, which traditionally is nonaggressive. The typical patient with MF is older than 60 years and presents with indolent, ongoing, flat to minimally indurated patches or plaques that have cigarette paper scale. As MF progresses, some plaques grow into tumors and can become more aggressive. Histologically, MF changes based on its clinical stage, with the initial phase showing epidermotropic atypical lymphocytes and later phases showing less epitheliotropic, larger, atypical lymphocytes. The treatment algorithm varies depending on cutaneous T-cell lymphoma staging.6

Tinea infections are caused by dermatophytes. In prepubertal children, they predominantly appear as tinea corporis (on the body) or tinea capitis (on the scalp), but in adults they appear as tinea cruris (on the groin), tinea pedis (on the feet), or tinea unguium (on the nails).7 Tinea infections classically are known to appear as an annular patch with an active erythematous scaling border and central clearing. The patches can be pruritic. Potassium hydroxide preparation of a skin scraping is a quick test to use in the office; if the results are inconclusive, a culture may be required. Treatment depends on the location of the infection but typically involves either topical or oral antifungal agents.7

- Tchernev G, Cardoso JC, Chokoeva AA, et al. The “mystery” of cutaneous sarcoidosis: facts and controversies. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27:321-330. doi:10.1177/039463201402700302

- Ali MM, Atwan AA, Gonzalez ML. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: updates in the pathogenesis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:747-755. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03517.x

- Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment [published online March 23, 2019]. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Bhat MR, Hulmani M, Dandakeri S, et al. Disseminated discoid lupus erythematosus leading to squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:158-161. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.94298

- Pulitzer M. Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:527-546. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.006

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

A biopsy of a plaque on the back confirmed cutaneous sarcoidosis (CS). A chest radiograph demonstrated hilar nodes, and a referral was placed for comanagement with a pulmonologist. Histopathology was critical in making the diagnosis, with well-circumscribed noncaseating granulomas present in the dermis. The granulomas in CS often are described as naked, as there are minimal lymphocytes present and plasma cells normally are absent.1 Because the lungs are the most common site of involvement, a chest radiograph is necessary to examine for systemic sarcoidosis. Laboratory workup is used to evaluate for lymphopenia, hypercalcemia, elevated blood sedimentation rate, and elevated angiotensin- converting enzyme levels, which are common in systemic sarcoidosis.1

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disorder with an unknown etiology. It is believed to develop in genetically predisposed individuals as a reaction to unidentified antigens in the environment.1 Helper T cells (TH1) respond to these environmental antigens in those who are susceptible, which leads to the disease process, but paradoxically, even with the elevation of cellular immune activity at the sites of the granulomatous inflammation, the peripheral immune response in these patients is suppressed as shown by lymphopenia.2

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is found in approximately one-third of patients with systemic sarcoidosis but can occur without systemic involvement.1,2 Sarcoidosis is reported worldwide and affects patients of all races and ethnicities, ages, and sexes but does have a higher prevalence among Black individuals in the United States, patients younger than 40 years (peak incidence, 20–29 years of age), and females.2 In 80% of patients, CS occurs before systemic sarcoidosis develops, or they may develop simultaneously.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations that are classified as specific and nonspecific. Specific lesions in CS contain noncaseating granulomas while nonspecific lesions in CS appear as reactive processes.2 The most common specific presentation of CS includes papules that are brown in pigmentation in lighter skin tones and red to violaceous in darker skin tones (Figure). The most common nonspecific skin manifestation is erythema nodosum, which represents a hypersensitivity reaction. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can appear as hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or plaques.1

Treatments for CS vary based on the individual.1 For milder and more localized cases, topical or intralesional steroids may be used. If systemic sarcoidosis is suspected or if there is diffuse involvement of the skin, systemic steroids, antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine), low-dose methotrexate, minocycline, allopurinol, azathioprine, isotretinoin, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, or psoralen plus long-wave UVA radiation may be used. If systemic sarcoidosis is present, referral to a pulmonologist is recommended for co-management.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is known as the “great imitator,” and there are multiple diseases to consider in the differential that are distinguished by the physical findings.1 In our case of a middle-aged Black woman with indurated plaques, a few diagnoses to consider were psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), mycosis fungoides (MF), and tinea infection.

Psoriasis is a common disease, and 90% of patients have chronic plaquelike disease with well-demarcated erythematous plaques that have a silver-gray scale and a positive Auspitz sign (also known as pinpoint bleeding).3 Plaques often are distributed on the trunk, limb extensors, and scalp, along with nail changes. Some patients also have joint pain, indicating psoriatic arthritis. The etiology of psoriasis is unknown, but it develops due to unrestrained keratinocyte proliferation and defective differentiation, which leads to histopathology showing regular acanthosis and papillary dermal ectasia with rouleaux. Mild cases typically are treated with topical steroids or vitamin D, while more severe cases are treated with methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, or biologics.3

Discoid lupus erythematosus occurs 4 times more often in Black patients than in White patients. Clinically, DLE begins as well-defined, erythematous, scaly patches that expand with hyperpigmentation at the periphery and leave an atrophic, scarred, hypopigmented center.4 It typically is localized to the head and neck, but in cases where it disseminates elsewhere on the body, the risk for systemic lupus erythematosus increases from 1.2% to 28%.5 Histopathology of DLE shows vacuolar degeneration of the basal cell layer in the epidermis along with patchy lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Treatments range from topical steroids for mild cases to antimalarial agents, retinoids, anti-inflammatory drugs, and calcineurin inhibitors for more severe cases.4

Although there are multiple types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the most common is MF, which traditionally is nonaggressive. The typical patient with MF is older than 60 years and presents with indolent, ongoing, flat to minimally indurated patches or plaques that have cigarette paper scale. As MF progresses, some plaques grow into tumors and can become more aggressive. Histologically, MF changes based on its clinical stage, with the initial phase showing epidermotropic atypical lymphocytes and later phases showing less epitheliotropic, larger, atypical lymphocytes. The treatment algorithm varies depending on cutaneous T-cell lymphoma staging.6

Tinea infections are caused by dermatophytes. In prepubertal children, they predominantly appear as tinea corporis (on the body) or tinea capitis (on the scalp), but in adults they appear as tinea cruris (on the groin), tinea pedis (on the feet), or tinea unguium (on the nails).7 Tinea infections classically are known to appear as an annular patch with an active erythematous scaling border and central clearing. The patches can be pruritic. Potassium hydroxide preparation of a skin scraping is a quick test to use in the office; if the results are inconclusive, a culture may be required. Treatment depends on the location of the infection but typically involves either topical or oral antifungal agents.7

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Sarcoidosis

A biopsy of a plaque on the back confirmed cutaneous sarcoidosis (CS). A chest radiograph demonstrated hilar nodes, and a referral was placed for comanagement with a pulmonologist. Histopathology was critical in making the diagnosis, with well-circumscribed noncaseating granulomas present in the dermis. The granulomas in CS often are described as naked, as there are minimal lymphocytes present and plasma cells normally are absent.1 Because the lungs are the most common site of involvement, a chest radiograph is necessary to examine for systemic sarcoidosis. Laboratory workup is used to evaluate for lymphopenia, hypercalcemia, elevated blood sedimentation rate, and elevated angiotensin- converting enzyme levels, which are common in systemic sarcoidosis.1

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disorder with an unknown etiology. It is believed to develop in genetically predisposed individuals as a reaction to unidentified antigens in the environment.1 Helper T cells (TH1) respond to these environmental antigens in those who are susceptible, which leads to the disease process, but paradoxically, even with the elevation of cellular immune activity at the sites of the granulomatous inflammation, the peripheral immune response in these patients is suppressed as shown by lymphopenia.2

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is found in approximately one-third of patients with systemic sarcoidosis but can occur without systemic involvement.1,2 Sarcoidosis is reported worldwide and affects patients of all races and ethnicities, ages, and sexes but does have a higher prevalence among Black individuals in the United States, patients younger than 40 years (peak incidence, 20–29 years of age), and females.2 In 80% of patients, CS occurs before systemic sarcoidosis develops, or they may develop simultaneously.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations that are classified as specific and nonspecific. Specific lesions in CS contain noncaseating granulomas while nonspecific lesions in CS appear as reactive processes.2 The most common specific presentation of CS includes papules that are brown in pigmentation in lighter skin tones and red to violaceous in darker skin tones (Figure). The most common nonspecific skin manifestation is erythema nodosum, which represents a hypersensitivity reaction. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can appear as hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or plaques.1

Treatments for CS vary based on the individual.1 For milder and more localized cases, topical or intralesional steroids may be used. If systemic sarcoidosis is suspected or if there is diffuse involvement of the skin, systemic steroids, antimalarials (eg, hydroxychloroquine), low-dose methotrexate, minocycline, allopurinol, azathioprine, isotretinoin, tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, or psoralen plus long-wave UVA radiation may be used. If systemic sarcoidosis is present, referral to a pulmonologist is recommended for co-management.1

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is known as the “great imitator,” and there are multiple diseases to consider in the differential that are distinguished by the physical findings.1 In our case of a middle-aged Black woman with indurated plaques, a few diagnoses to consider were psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), mycosis fungoides (MF), and tinea infection.

Psoriasis is a common disease, and 90% of patients have chronic plaquelike disease with well-demarcated erythematous plaques that have a silver-gray scale and a positive Auspitz sign (also known as pinpoint bleeding).3 Plaques often are distributed on the trunk, limb extensors, and scalp, along with nail changes. Some patients also have joint pain, indicating psoriatic arthritis. The etiology of psoriasis is unknown, but it develops due to unrestrained keratinocyte proliferation and defective differentiation, which leads to histopathology showing regular acanthosis and papillary dermal ectasia with rouleaux. Mild cases typically are treated with topical steroids or vitamin D, while more severe cases are treated with methotrexate, cyclosporine, retinoids, or biologics.3

Discoid lupus erythematosus occurs 4 times more often in Black patients than in White patients. Clinically, DLE begins as well-defined, erythematous, scaly patches that expand with hyperpigmentation at the periphery and leave an atrophic, scarred, hypopigmented center.4 It typically is localized to the head and neck, but in cases where it disseminates elsewhere on the body, the risk for systemic lupus erythematosus increases from 1.2% to 28%.5 Histopathology of DLE shows vacuolar degeneration of the basal cell layer in the epidermis along with patchy lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis. Treatments range from topical steroids for mild cases to antimalarial agents, retinoids, anti-inflammatory drugs, and calcineurin inhibitors for more severe cases.4

Although there are multiple types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the most common is MF, which traditionally is nonaggressive. The typical patient with MF is older than 60 years and presents with indolent, ongoing, flat to minimally indurated patches or plaques that have cigarette paper scale. As MF progresses, some plaques grow into tumors and can become more aggressive. Histologically, MF changes based on its clinical stage, with the initial phase showing epidermotropic atypical lymphocytes and later phases showing less epitheliotropic, larger, atypical lymphocytes. The treatment algorithm varies depending on cutaneous T-cell lymphoma staging.6

Tinea infections are caused by dermatophytes. In prepubertal children, they predominantly appear as tinea corporis (on the body) or tinea capitis (on the scalp), but in adults they appear as tinea cruris (on the groin), tinea pedis (on the feet), or tinea unguium (on the nails).7 Tinea infections classically are known to appear as an annular patch with an active erythematous scaling border and central clearing. The patches can be pruritic. Potassium hydroxide preparation of a skin scraping is a quick test to use in the office; if the results are inconclusive, a culture may be required. Treatment depends on the location of the infection but typically involves either topical or oral antifungal agents.7

- Tchernev G, Cardoso JC, Chokoeva AA, et al. The “mystery” of cutaneous sarcoidosis: facts and controversies. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27:321-330. doi:10.1177/039463201402700302

- Ali MM, Atwan AA, Gonzalez ML. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: updates in the pathogenesis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:747-755. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03517.x

- Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment [published online March 23, 2019]. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Bhat MR, Hulmani M, Dandakeri S, et al. Disseminated discoid lupus erythematosus leading to squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:158-161. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.94298

- Pulitzer M. Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:527-546. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.006

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Tchernev G, Cardoso JC, Chokoeva AA, et al. The “mystery” of cutaneous sarcoidosis: facts and controversies. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27:321-330. doi:10.1177/039463201402700302

- Ali MM, Atwan AA, Gonzalez ML. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: updates in the pathogenesis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:747-755. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03517.x

- Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment [published online March 23, 2019]. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi:10.3390/ijms20061475

- McDaniel B, Sukumaran S, Koritala T, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493145/

- Bhat MR, Hulmani M, Dandakeri S, et al. Disseminated discoid lupus erythematosus leading to squamous cell carcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:158-161. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.94298

- Pulitzer M. Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017; 37:527-546. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.06.006

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

A 35-year-old Black woman presented to dermatology as a new patient for evaluation of an asymptomatic rash that had enlarged and spread to involve both the face and back over the last 4 months. She had not tried any treatments. She had no notable medical history and was uncertain of her family history. Physical examination showed indurated, flesh-colored to violaceous plaques around the alar-facial groove (top), nasal tip, chin, and back (bottom). The mucosae and nails were not involved.

Botanical Briefs: Australian Stinging Tree (Dendrocnide moroides)

Clinical Importance

Dendrocnide moroides is arguably the most brutal of stinging plants, even leading to death in dogs, horses, and humans in rare cases.1-3 Commonly called gympie-gympie (based on its discovery by gold miners near the town of Gympie in Queensland, Australia), D moroides also has been referred to as the mulberrylike stinging tree or stinger.2,4-6

Family and Nomenclature

The Australian stinging tree belongs to the family Urticaceae (known as the nettle family) within the order Rosales.1,2,3,5 Urticaceae is derived from the Latin term urere (to burn)—an apt description of the clinical experience of patients with D moroides–induced urticaria.

Urticaceae includes 54 genera, comprising herbs, shrubs, small trees, and vines found predominantly in tropical regions. Dendrocnide comprises approximately 40 species, all commonly known in Australia as stinging trees.2,7,8

Distribution

Dendrocnide moroides is found in the rainforests of Australia and Southeast Asia.2 Because the plant has a strong need for sunlight and wind protection, it typically is found in light-filled gaps within the rainforest, in moist ravines, along the edges of creeks, and on land bordering the rainforest.3,6

Appearance

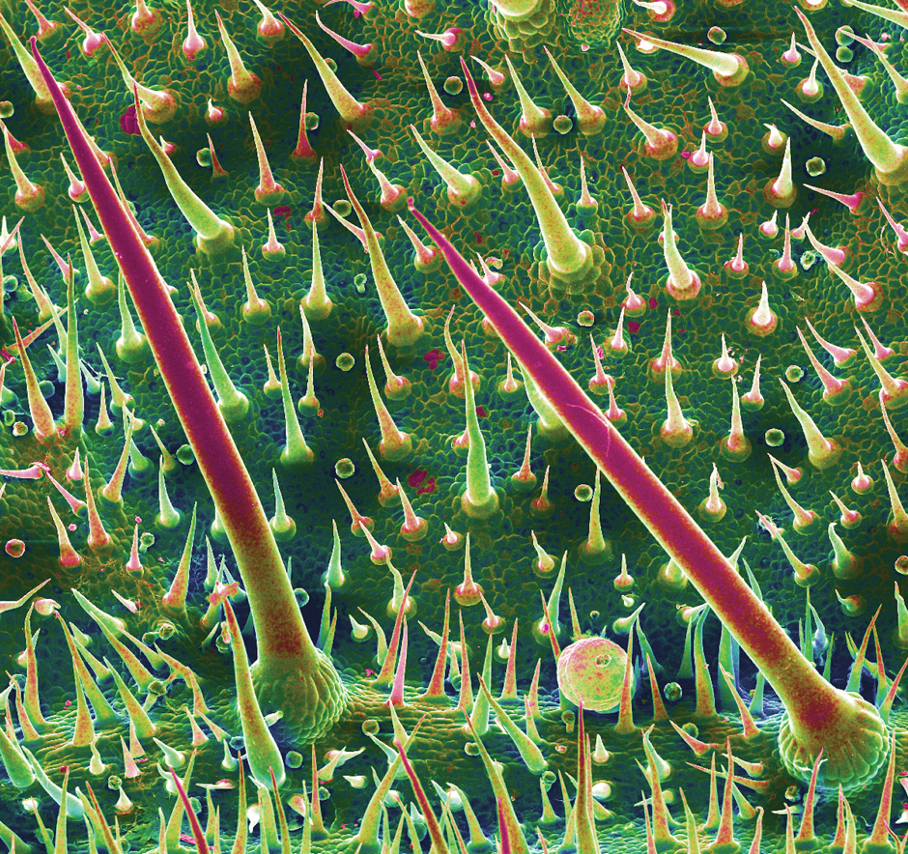

Although D moroides is referred to as a tree, it is an understory shrub that typically grows to 3 m, with heart-shaped, serrated, dark green leaves that are 50-cm wide (Figure 1).6 The leaves are produced consistently through the year, with variable growth depending on the season.9

The plant is covered in what appears to be soft downy fur made up of trichomes (or plant hairs).1,6 The density of the hairs on leaves decreases as they age.2,9 The fruit, which is actually edible (if one is careful to avoid hairs), appears similar to red to dark purple raspberries growing on long stems.5,6

Cutaneous Manifestations

Symptoms of contact with the stems and leaves of D moroides range from slight irritation to serious neurologic disorders, including neuropathy. The severity of the reaction depends on the person, how much skin was contacted, and how one came into contact with the plant.1,5 Upon touch, there is an immediate reaction, with burning, urticaria, and edema. Pain increases, peaking 30 minutes later; then the pain slowly subsides.1 Tachycardia and throbbing regional lymphadenopathy can occur for 1 to 4 hours.1,6

Cutaneous Findings—Examination reveals immediate piloerection, erythema due to arteriolar dilation, and local swelling.2 These findings may disappear after 1 hour or last as long as 24 hours.1 Although objective signs may fade, subjective pain, pruritus, and burning can persist for months.3

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

After contact with the stems or leaves, the sharp trichomes become embedded in the skin, making them difficult to remove.1 The toxins are contained in siliceous hairs that the human body cannot break down.3 Symptoms can be experienced for as long as 1 year after contact, especially when the skin is pressed firmly or washed with hot or cold water.3,6 Because the plant’s hairs are shed continuously, being in close proximity to D moroides for longer than 20 minutes can lead to extreme sneezing, nosebleeds, and major respiratory damage from inhaling hairs.1,6,9

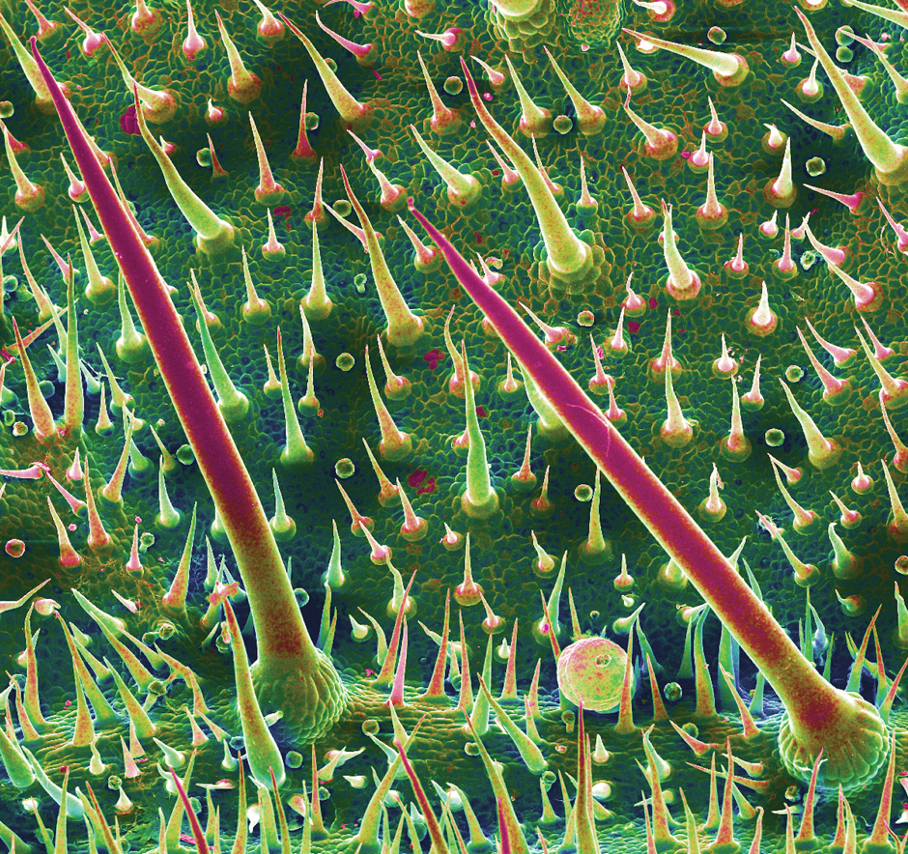

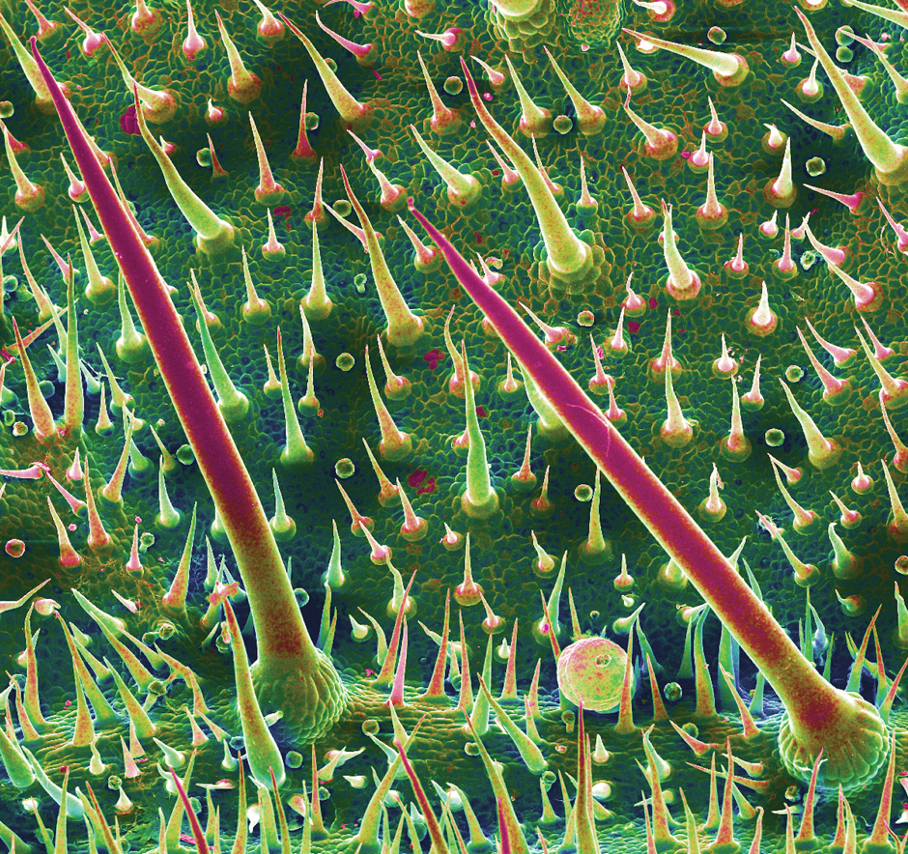

The stinging hairs of D moroides differ from irritant hairs on other plants because they contain physiologically active substances. Stinging hairs are classified as either a hypodermic syringe, which expels liquid only, or as a tragia-type syringe, in which liquid and sharp crystals are injected.

The Australian stinging tree falls into the first of these 2 groups (Figure 2)1; the sharp tip of the hair breaks on contact, leading to expulsion of the toxin into skin.1,4 The hairs function as a defense against mammalian herbivores but typically have no impact on pests.1 Nocturnal beetles and on occasion possums and red-legged pademelons dare to eat D moroides.3,6

The Irritant

Initially, formic acid was proposed as the irritant chemical in D moroides1; other candidates have included neurotransmitters, such as histamine, acetylcholine, and serotonin, as well as inorganic ions, such as potassium. These compounds may play a role but none explain the persistent sensory effects and years-long stable nature of the toxin.1,4

The most likely culprit irritant is a member of a newly discovered family of neurotoxins, the gympietides. These knot-shaped chemicals, found in D moroides and some spider venoms, have the ability to activate voltage-gated sodium channels of cutaneous neurons and cause local cutaneous vasodilation by stimulating neurotransmitter release.4 These neurotoxins not only generate pain but also suppress the mechanism used to interrupt those pain signals.10 Synthesized gympietides can replicate the effects of natural contact, indicating that they are the primary active toxins. These toxins are ultrastable, thus producing lasting effects.1

Although much is understood about the evolution and distribution of D moroides and the ecological role that it plays, there is still more to learn about the plant’s toxicology.

Prevention and Treatment

Prevention—Dendrocnide moroides dermatitis is best prevented by avoiding contact with the plant and related species, as well as wearing upper body clothing with long sleeves, pants, and boots, though plant hairs can still penetrate garments and sting.2,3

Therapy—There is no reversal therapy of D moroides dermatitis but symptoms can be managed.4 For pain, analgesics, such as opioids, have been used; on occasion, however, pain is so intense that even morphine does not help.4,10

Systemic or topical corticosteroids are the main therapy for many forms of plant-induced dermatitis because they are able to decrease cytokine production and stop lymphocyte production. Adding an oral antihistamine can alleviate histamine-mediated pruritus but not pruritus that is mediated by other chemicals.11

Other methods of relieving symptoms of D moroides dermatitis have been proposed or reported anecdotally. Diluted hydrochloric acid can be applied to the skin to denature remaining toxin.4 The sap of Alocasia brisbanensis (the cunjevoi plant) can be rubbed on affected areas to provide a cooling effect, but do not allow A brisbanensis sap to enter the mouth, as it contains calcium oxalate, a toxic irritant found in dumb cane (Dieffenbachia species). The roots of the Australian stinging tree also can be ground and made into a paste, which is applied to the skin.3 However, given the stability of the toxin, we do not recommend these remedies.

Instead, heavy-duty masking tape or hot wax can be applied to remove plant hairs from the skin. The most successful method of removing plant hair is hair removal wax strips, which are considered an essential component of a first aid kit where D moroides is found.3

- Ensikat H-J, Wessely H, Engeser M, et al. Distribution, ecology, chemistry and toxicology of plant stinging hairs. Toxins (Basel). 2021;13:141. doi:10.3390/toxins13020141

- Schmitt C, Parola P, de Haro L. Painful sting after exposure to Dendrocnide sp: two case reports. Wilderness Environ Med. 2013;24:471-473. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2013.03.021

- Hurley M. Selective stingers. ECOS. 2000;105:18-23. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.writingclearscience.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/stingers.pdf

- Gilding EK, Jami S, Deuis JR, et al. Neurotoxic peptides from the venom of the giant Australian stinging tree. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabb8828. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb8828

- Dendrocnide moroides. James Cook University Australia website. Accessed Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.jcu.edu.au/discover-nature-at-jcu/plants/plants-by-scientific-name2/dendrocnide-moroides

- Hurley M. ‘The worst kind of pain you can imagine’—what it’s like to be stung by a stinging tree. The Conversation. September 28, 2018. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://theconversation.com/the-worst-kind-of-pain-you-can-imagine-what-its-like-to-be-stung-by-a-stinging-tree-103220

- Urticaceae: plant family. Britannica [Internet]. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Urticaceae

- Stinging trees (genus Dendrocnide). iNaturalist.ca [Internet]. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://inaturalist.ca/taxa/129502-Dendrocnide

- Hurley M. Growth dynamics and leaf quality of the stinging trees Dendrocnide moroides and Dendrocnide cordifolia (family Urticaceae) in Australian tropical rainforest: implications for herbivores. Aust J Bot. 2000;48:191-201. doi:10.1071/BT98006

- How the giant stinging tree of Australia can inflict months of agony. Nature. September 17, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02668-9

- Chang Y-T, Shen J-J, Wong W-R, et al. Alternative therapy for autosensitization dermatitis. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:668-673.

Clinical Importance

Dendrocnide moroides is arguably the most brutal of stinging plants, even leading to death in dogs, horses, and humans in rare cases.1-3 Commonly called gympie-gympie (based on its discovery by gold miners near the town of Gympie in Queensland, Australia), D moroides also has been referred to as the mulberrylike stinging tree or stinger.2,4-6

Family and Nomenclature

The Australian stinging tree belongs to the family Urticaceae (known as the nettle family) within the order Rosales.1,2,3,5 Urticaceae is derived from the Latin term urere (to burn)—an apt description of the clinical experience of patients with D moroides–induced urticaria.

Urticaceae includes 54 genera, comprising herbs, shrubs, small trees, and vines found predominantly in tropical regions. Dendrocnide comprises approximately 40 species, all commonly known in Australia as stinging trees.2,7,8

Distribution

Dendrocnide moroides is found in the rainforests of Australia and Southeast Asia.2 Because the plant has a strong need for sunlight and wind protection, it typically is found in light-filled gaps within the rainforest, in moist ravines, along the edges of creeks, and on land bordering the rainforest.3,6

Appearance

Although D moroides is referred to as a tree, it is an understory shrub that typically grows to 3 m, with heart-shaped, serrated, dark green leaves that are 50-cm wide (Figure 1).6 The leaves are produced consistently through the year, with variable growth depending on the season.9

The plant is covered in what appears to be soft downy fur made up of trichomes (or plant hairs).1,6 The density of the hairs on leaves decreases as they age.2,9 The fruit, which is actually edible (if one is careful to avoid hairs), appears similar to red to dark purple raspberries growing on long stems.5,6

Cutaneous Manifestations

Symptoms of contact with the stems and leaves of D moroides range from slight irritation to serious neurologic disorders, including neuropathy. The severity of the reaction depends on the person, how much skin was contacted, and how one came into contact with the plant.1,5 Upon touch, there is an immediate reaction, with burning, urticaria, and edema. Pain increases, peaking 30 minutes later; then the pain slowly subsides.1 Tachycardia and throbbing regional lymphadenopathy can occur for 1 to 4 hours.1,6

Cutaneous Findings—Examination reveals immediate piloerection, erythema due to arteriolar dilation, and local swelling.2 These findings may disappear after 1 hour or last as long as 24 hours.1 Although objective signs may fade, subjective pain, pruritus, and burning can persist for months.3

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

After contact with the stems or leaves, the sharp trichomes become embedded in the skin, making them difficult to remove.1 The toxins are contained in siliceous hairs that the human body cannot break down.3 Symptoms can be experienced for as long as 1 year after contact, especially when the skin is pressed firmly or washed with hot or cold water.3,6 Because the plant’s hairs are shed continuously, being in close proximity to D moroides for longer than 20 minutes can lead to extreme sneezing, nosebleeds, and major respiratory damage from inhaling hairs.1,6,9

The stinging hairs of D moroides differ from irritant hairs on other plants because they contain physiologically active substances. Stinging hairs are classified as either a hypodermic syringe, which expels liquid only, or as a tragia-type syringe, in which liquid and sharp crystals are injected.

The Australian stinging tree falls into the first of these 2 groups (Figure 2)1; the sharp tip of the hair breaks on contact, leading to expulsion of the toxin into skin.1,4 The hairs function as a defense against mammalian herbivores but typically have no impact on pests.1 Nocturnal beetles and on occasion possums and red-legged pademelons dare to eat D moroides.3,6

The Irritant

Initially, formic acid was proposed as the irritant chemical in D moroides1; other candidates have included neurotransmitters, such as histamine, acetylcholine, and serotonin, as well as inorganic ions, such as potassium. These compounds may play a role but none explain the persistent sensory effects and years-long stable nature of the toxin.1,4

The most likely culprit irritant is a member of a newly discovered family of neurotoxins, the gympietides. These knot-shaped chemicals, found in D moroides and some spider venoms, have the ability to activate voltage-gated sodium channels of cutaneous neurons and cause local cutaneous vasodilation by stimulating neurotransmitter release.4 These neurotoxins not only generate pain but also suppress the mechanism used to interrupt those pain signals.10 Synthesized gympietides can replicate the effects of natural contact, indicating that they are the primary active toxins. These toxins are ultrastable, thus producing lasting effects.1

Although much is understood about the evolution and distribution of D moroides and the ecological role that it plays, there is still more to learn about the plant’s toxicology.

Prevention and Treatment

Prevention—Dendrocnide moroides dermatitis is best prevented by avoiding contact with the plant and related species, as well as wearing upper body clothing with long sleeves, pants, and boots, though plant hairs can still penetrate garments and sting.2,3

Therapy—There is no reversal therapy of D moroides dermatitis but symptoms can be managed.4 For pain, analgesics, such as opioids, have been used; on occasion, however, pain is so intense that even morphine does not help.4,10

Systemic or topical corticosteroids are the main therapy for many forms of plant-induced dermatitis because they are able to decrease cytokine production and stop lymphocyte production. Adding an oral antihistamine can alleviate histamine-mediated pruritus but not pruritus that is mediated by other chemicals.11

Other methods of relieving symptoms of D moroides dermatitis have been proposed or reported anecdotally. Diluted hydrochloric acid can be applied to the skin to denature remaining toxin.4 The sap of Alocasia brisbanensis (the cunjevoi plant) can be rubbed on affected areas to provide a cooling effect, but do not allow A brisbanensis sap to enter the mouth, as it contains calcium oxalate, a toxic irritant found in dumb cane (Dieffenbachia species). The roots of the Australian stinging tree also can be ground and made into a paste, which is applied to the skin.3 However, given the stability of the toxin, we do not recommend these remedies.

Instead, heavy-duty masking tape or hot wax can be applied to remove plant hairs from the skin. The most successful method of removing plant hair is hair removal wax strips, which are considered an essential component of a first aid kit where D moroides is found.3

Clinical Importance

Dendrocnide moroides is arguably the most brutal of stinging plants, even leading to death in dogs, horses, and humans in rare cases.1-3 Commonly called gympie-gympie (based on its discovery by gold miners near the town of Gympie in Queensland, Australia), D moroides also has been referred to as the mulberrylike stinging tree or stinger.2,4-6

Family and Nomenclature

The Australian stinging tree belongs to the family Urticaceae (known as the nettle family) within the order Rosales.1,2,3,5 Urticaceae is derived from the Latin term urere (to burn)—an apt description of the clinical experience of patients with D moroides–induced urticaria.

Urticaceae includes 54 genera, comprising herbs, shrubs, small trees, and vines found predominantly in tropical regions. Dendrocnide comprises approximately 40 species, all commonly known in Australia as stinging trees.2,7,8

Distribution

Dendrocnide moroides is found in the rainforests of Australia and Southeast Asia.2 Because the plant has a strong need for sunlight and wind protection, it typically is found in light-filled gaps within the rainforest, in moist ravines, along the edges of creeks, and on land bordering the rainforest.3,6

Appearance

Although D moroides is referred to as a tree, it is an understory shrub that typically grows to 3 m, with heart-shaped, serrated, dark green leaves that are 50-cm wide (Figure 1).6 The leaves are produced consistently through the year, with variable growth depending on the season.9

The plant is covered in what appears to be soft downy fur made up of trichomes (or plant hairs).1,6 The density of the hairs on leaves decreases as they age.2,9 The fruit, which is actually edible (if one is careful to avoid hairs), appears similar to red to dark purple raspberries growing on long stems.5,6

Cutaneous Manifestations

Symptoms of contact with the stems and leaves of D moroides range from slight irritation to serious neurologic disorders, including neuropathy. The severity of the reaction depends on the person, how much skin was contacted, and how one came into contact with the plant.1,5 Upon touch, there is an immediate reaction, with burning, urticaria, and edema. Pain increases, peaking 30 minutes later; then the pain slowly subsides.1 Tachycardia and throbbing regional lymphadenopathy can occur for 1 to 4 hours.1,6

Cutaneous Findings—Examination reveals immediate piloerection, erythema due to arteriolar dilation, and local swelling.2 These findings may disappear after 1 hour or last as long as 24 hours.1 Although objective signs may fade, subjective pain, pruritus, and burning can persist for months.3

Dermatitis-Inducing Plant Parts

After contact with the stems or leaves, the sharp trichomes become embedded in the skin, making them difficult to remove.1 The toxins are contained in siliceous hairs that the human body cannot break down.3 Symptoms can be experienced for as long as 1 year after contact, especially when the skin is pressed firmly or washed with hot or cold water.3,6 Because the plant’s hairs are shed continuously, being in close proximity to D moroides for longer than 20 minutes can lead to extreme sneezing, nosebleeds, and major respiratory damage from inhaling hairs.1,6,9

The stinging hairs of D moroides differ from irritant hairs on other plants because they contain physiologically active substances. Stinging hairs are classified as either a hypodermic syringe, which expels liquid only, or as a tragia-type syringe, in which liquid and sharp crystals are injected.

The Australian stinging tree falls into the first of these 2 groups (Figure 2)1; the sharp tip of the hair breaks on contact, leading to expulsion of the toxin into skin.1,4 The hairs function as a defense against mammalian herbivores but typically have no impact on pests.1 Nocturnal beetles and on occasion possums and red-legged pademelons dare to eat D moroides.3,6

The Irritant

Initially, formic acid was proposed as the irritant chemical in D moroides1; other candidates have included neurotransmitters, such as histamine, acetylcholine, and serotonin, as well as inorganic ions, such as potassium. These compounds may play a role but none explain the persistent sensory effects and years-long stable nature of the toxin.1,4

The most likely culprit irritant is a member of a newly discovered family of neurotoxins, the gympietides. These knot-shaped chemicals, found in D moroides and some spider venoms, have the ability to activate voltage-gated sodium channels of cutaneous neurons and cause local cutaneous vasodilation by stimulating neurotransmitter release.4 These neurotoxins not only generate pain but also suppress the mechanism used to interrupt those pain signals.10 Synthesized gympietides can replicate the effects of natural contact, indicating that they are the primary active toxins. These toxins are ultrastable, thus producing lasting effects.1

Although much is understood about the evolution and distribution of D moroides and the ecological role that it plays, there is still more to learn about the plant’s toxicology.

Prevention and Treatment

Prevention—Dendrocnide moroides dermatitis is best prevented by avoiding contact with the plant and related species, as well as wearing upper body clothing with long sleeves, pants, and boots, though plant hairs can still penetrate garments and sting.2,3

Therapy—There is no reversal therapy of D moroides dermatitis but symptoms can be managed.4 For pain, analgesics, such as opioids, have been used; on occasion, however, pain is so intense that even morphine does not help.4,10

Systemic or topical corticosteroids are the main therapy for many forms of plant-induced dermatitis because they are able to decrease cytokine production and stop lymphocyte production. Adding an oral antihistamine can alleviate histamine-mediated pruritus but not pruritus that is mediated by other chemicals.11

Other methods of relieving symptoms of D moroides dermatitis have been proposed or reported anecdotally. Diluted hydrochloric acid can be applied to the skin to denature remaining toxin.4 The sap of Alocasia brisbanensis (the cunjevoi plant) can be rubbed on affected areas to provide a cooling effect, but do not allow A brisbanensis sap to enter the mouth, as it contains calcium oxalate, a toxic irritant found in dumb cane (Dieffenbachia species). The roots of the Australian stinging tree also can be ground and made into a paste, which is applied to the skin.3 However, given the stability of the toxin, we do not recommend these remedies.

Instead, heavy-duty masking tape or hot wax can be applied to remove plant hairs from the skin. The most successful method of removing plant hair is hair removal wax strips, which are considered an essential component of a first aid kit where D moroides is found.3

- Ensikat H-J, Wessely H, Engeser M, et al. Distribution, ecology, chemistry and toxicology of plant stinging hairs. Toxins (Basel). 2021;13:141. doi:10.3390/toxins13020141

- Schmitt C, Parola P, de Haro L. Painful sting after exposure to Dendrocnide sp: two case reports. Wilderness Environ Med. 2013;24:471-473. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2013.03.021

- Hurley M. Selective stingers. ECOS. 2000;105:18-23. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.writingclearscience.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/stingers.pdf

- Gilding EK, Jami S, Deuis JR, et al. Neurotoxic peptides from the venom of the giant Australian stinging tree. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabb8828. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb8828

- Dendrocnide moroides. James Cook University Australia website. Accessed Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.jcu.edu.au/discover-nature-at-jcu/plants/plants-by-scientific-name2/dendrocnide-moroides

- Hurley M. ‘The worst kind of pain you can imagine’—what it’s like to be stung by a stinging tree. The Conversation. September 28, 2018. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://theconversation.com/the-worst-kind-of-pain-you-can-imagine-what-its-like-to-be-stung-by-a-stinging-tree-103220

- Urticaceae: plant family. Britannica [Internet]. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Urticaceae

- Stinging trees (genus Dendrocnide). iNaturalist.ca [Internet]. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://inaturalist.ca/taxa/129502-Dendrocnide

- Hurley M. Growth dynamics and leaf quality of the stinging trees Dendrocnide moroides and Dendrocnide cordifolia (family Urticaceae) in Australian tropical rainforest: implications for herbivores. Aust J Bot. 2000;48:191-201. doi:10.1071/BT98006

- How the giant stinging tree of Australia can inflict months of agony. Nature. September 17, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02668-9

- Chang Y-T, Shen J-J, Wong W-R, et al. Alternative therapy for autosensitization dermatitis. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:668-673.

- Ensikat H-J, Wessely H, Engeser M, et al. Distribution, ecology, chemistry and toxicology of plant stinging hairs. Toxins (Basel). 2021;13:141. doi:10.3390/toxins13020141

- Schmitt C, Parola P, de Haro L. Painful sting after exposure to Dendrocnide sp: two case reports. Wilderness Environ Med. 2013;24:471-473. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2013.03.021

- Hurley M. Selective stingers. ECOS. 2000;105:18-23. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.writingclearscience.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/stingers.pdf

- Gilding EK, Jami S, Deuis JR, et al. Neurotoxic peptides from the venom of the giant Australian stinging tree. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eabb8828. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb8828

- Dendrocnide moroides. James Cook University Australia website. Accessed Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.jcu.edu.au/discover-nature-at-jcu/plants/plants-by-scientific-name2/dendrocnide-moroides

- Hurley M. ‘The worst kind of pain you can imagine’—what it’s like to be stung by a stinging tree. The Conversation. September 28, 2018. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://theconversation.com/the-worst-kind-of-pain-you-can-imagine-what-its-like-to-be-stung-by-a-stinging-tree-103220

- Urticaceae: plant family. Britannica [Internet]. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Urticaceae

- Stinging trees (genus Dendrocnide). iNaturalist.ca [Internet]. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://inaturalist.ca/taxa/129502-Dendrocnide

- Hurley M. Growth dynamics and leaf quality of the stinging trees Dendrocnide moroides and Dendrocnide cordifolia (family Urticaceae) in Australian tropical rainforest: implications for herbivores. Aust J Bot. 2000;48:191-201. doi:10.1071/BT98006

- How the giant stinging tree of Australia can inflict months of agony. Nature. September 17, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02668-9

- Chang Y-T, Shen J-J, Wong W-R, et al. Alternative therapy for autosensitization dermatitis. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:668-673.

Practice Points

- Dendrocnide moroides is arguably the most brutal of stinging plants, even leading to death in dogs, horses, and humans in rare cases.

- Clinical observations after contact reveal immediate piloerection and local swelling, which may disappear after 1 hour or last as long as 24 hours, but subjective pain, pruritus, and burning can persist for months.

- The most successful method of removing plant hair is hair removal wax strips, which are considered an essential component of a first aid kit where D moroides is found.

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy With Ocular Involvement

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

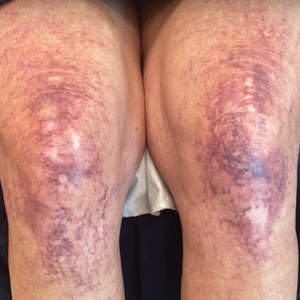

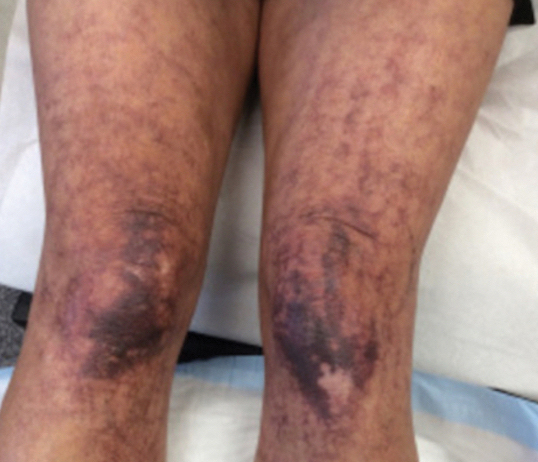

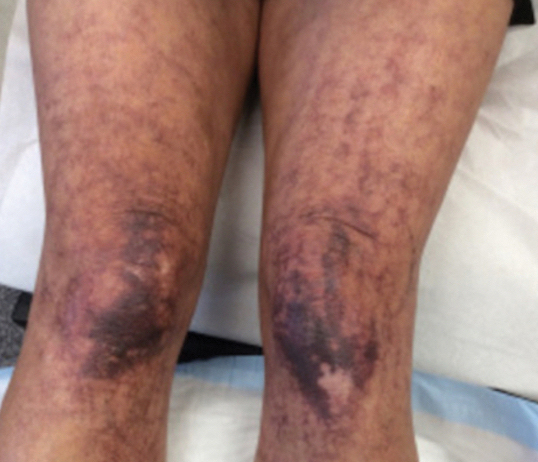

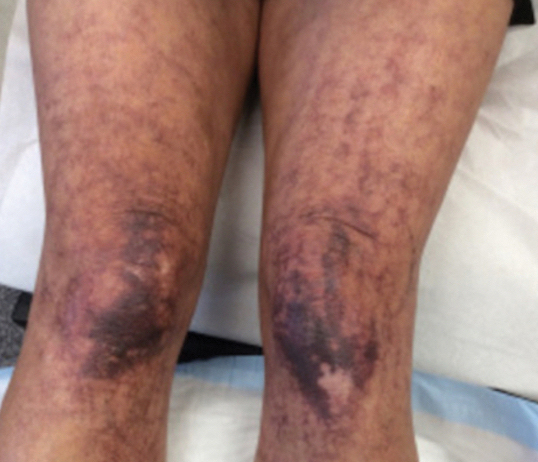

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

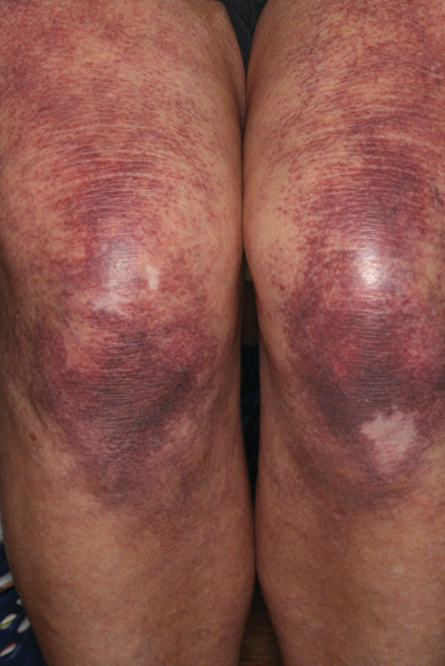

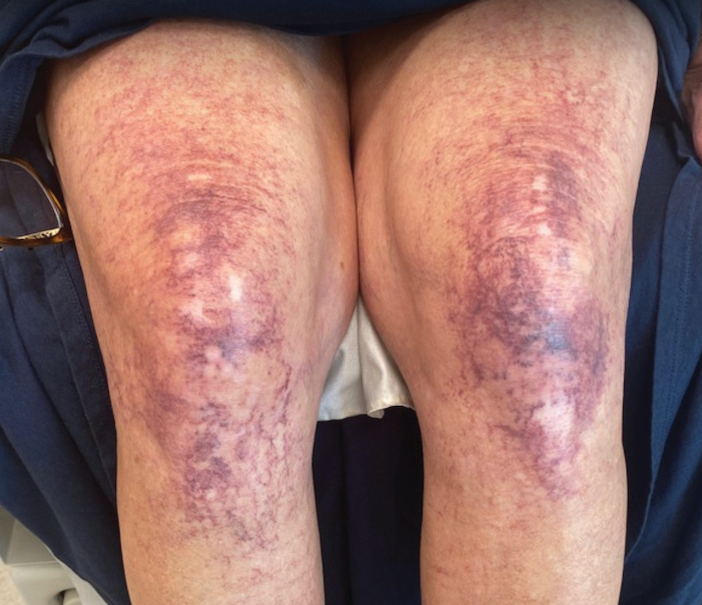

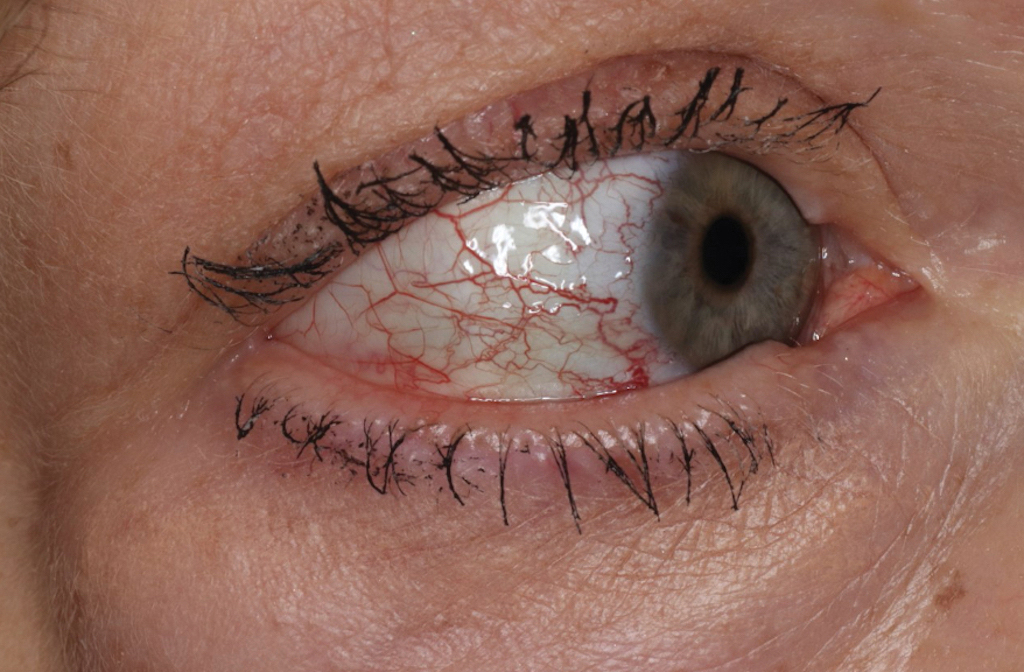

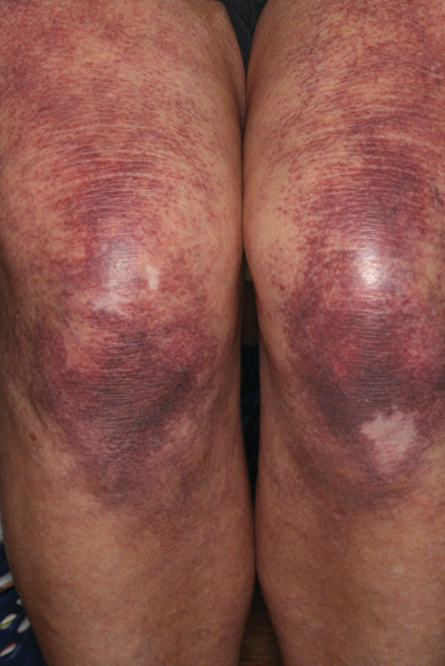

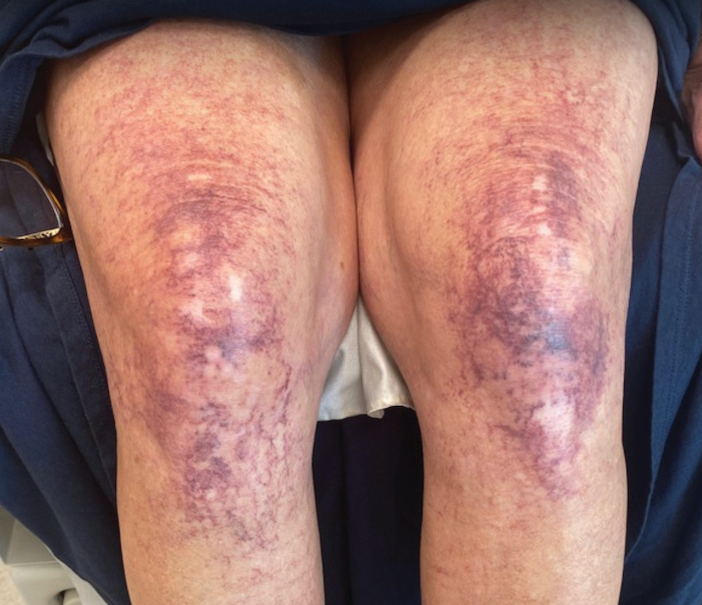

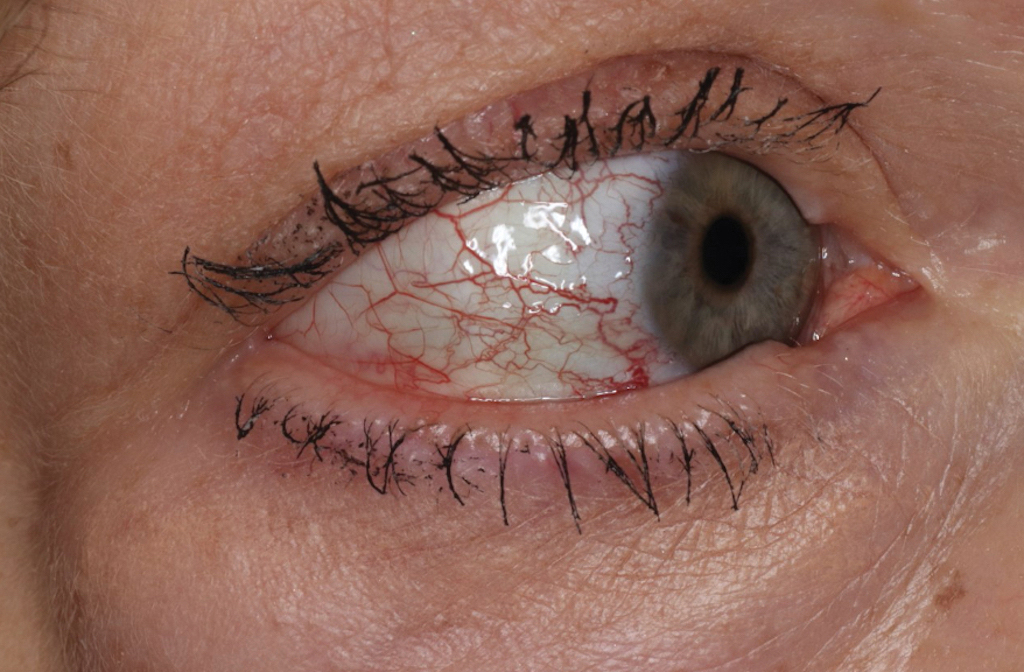

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

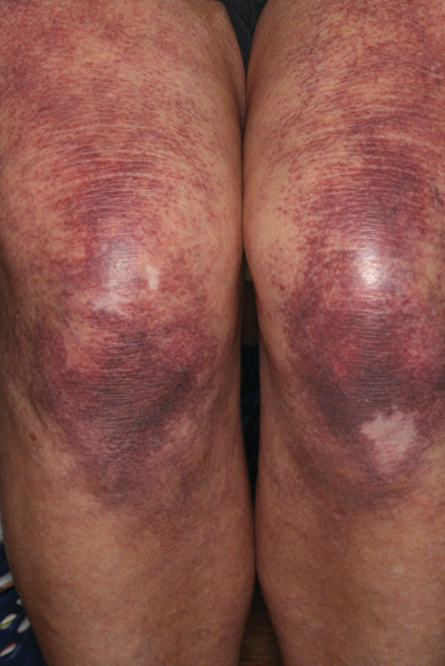

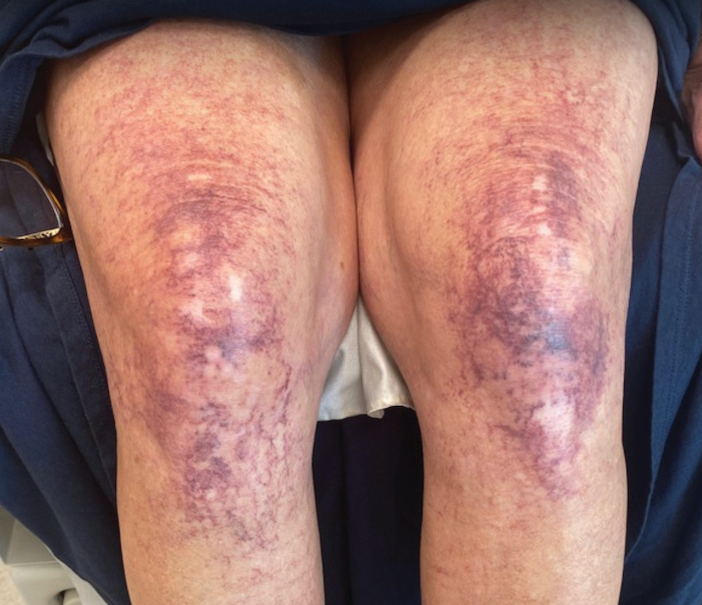

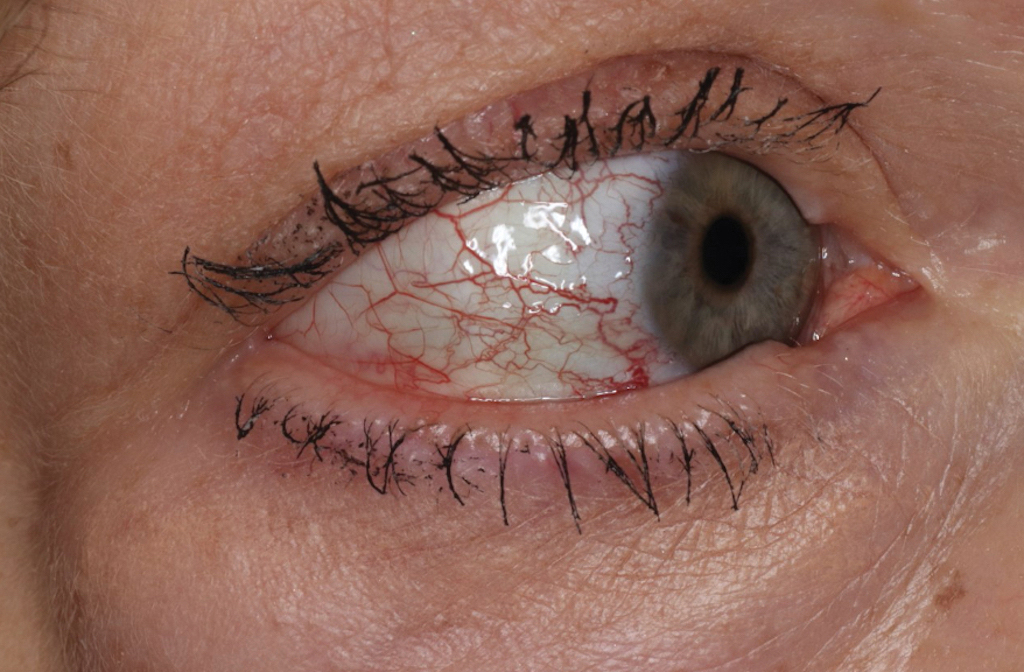

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

Practice Points

- Collagenous vasculopathy is an underrecognized entity.

- Although most patients exhibit only cutaneous disease, systemic involvement also should be assessed.