User login

A middle-aged man with progressive fatigue

A 61-year-old white man presents with progressive fatigue, which began several months ago and has accelerated in severity over the past week. He says he has had no shortness of breath, chest pain, or symptoms of heart failure, but he has noticed a decrease in exertional capacity and now has trouble completing his daily 5-mile walk.

He saw his primary physician, who obtained an electrocardiogram that showed a new left bundle branch block. Transthoracic echocardiography indicated that his left ventricular ejection fraction, which was 60% a year earlier, was now 35%.

He has hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Although he was previously morbidly obese, he has lost more than 100 pounds with diet and exercise over the past 10 years. He also used to smoke; in fact, he has a 30-pack-year history, but he quit in 1987. He has a family history of premature coronary artery disease.

Physical examination. His heart rate is 75 beats per minute, blood pressure 142/85 mm Hg, and blood oxygen saturation 96% while breathing room air. He weighs 169 pounds (76.6 kg) and he is 6 feet tall (182.9 cm), so his body mass index is 22.9 kg/m2.

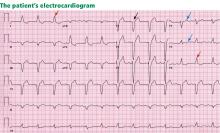

Electrocardiography reveals sinus rhythm with a left bundle branch block and left axis deviation (Figure 1), which were not present 1 year ago.

Chest roentgenography is normal.

A WORRISOME PICTURE

1. Which of the following is associated with left bundle branch block?

- Myocardial injury

- Hypertension

- Aortic stenosis

- Intrinsic conduction system disease

- All of the above

All of the above are true. For left bundle branch block to be diagnosed, the rhythm must be supraventricular and the QRS duration must be 120 ms or more. There should be a QS or RS complex in V1 and a monophasic R wave in I and V6. Also, the T wave should be deflected opposite the terminal deflection of the QRS complex. This is known as appropriate T-wave discordance with bundle branch block. A concordant T wave is nonspecific but suggests ischemia or myocardial infarction.

Potential causes of a new left bundle branch block include hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, aortic stenosis, and conduction system disease. A new left bundle branch block with a concomitant decrease in ejection fraction, especially in a patient with cardiac risk factors, is very worrisome, raising the possibility of ischemic heart disease.

MORE CARDIAC TESTING

The patient undergoes more cardiac testing.

Transthoracic echocardiography is done again. The left ventricle is normal in size, but the ejection fraction is 35%. In addition, stage 1 diastolic dysfunction (abnormal relaxation) and evidence of mechanical dyssynchrony (disruption in the normal sequence of activation and contraction of segments of the left ventricular wall) are seen. The right ventricle is normal in size and function. There is trivial mitral regurgitation and mild tricuspid regurgitation with normal right-sided pressures.

A gated rubidium-82 dipyridamole stress test yields no evidence of a fixed or reversible perfusion defect.

Left heart catheterization reveals angiographically normal coronary arteries.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a moderately hypertrophied left ventricle with moderately to severely depressed systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction 27%). The left ventricle appears dyssynchronous. Delayed-enhancement imaging reveals patchy delayed enhancement in the basal septum and the basal inferolateral walls. These findings suggest cardiac sarcoidosis, with a sensitivity of nearly 100% and a specificity of approximately 78%.1

SARCOIDOSIS IS A MULTISYSTEM DISEASE

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease characterized by noncaseating granulomas. Almost any organ can be affected, but it most commonly involves the respiratory and lymphatic systems.2 Although infectious, environmental, and genetic factors have been implicated, the cause remains unknown. The prevalence is approximately 20 per 100,000, being higher in black3 and Japanese 4 populations.

CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

2. What percentage of patients with sarcoidosis have cardiac involvement?

- 10%–20%

- 20%–30%

- 50%

- 80%

Cardiac involvement is seen in 20% to 30% of patients with sarcoidosis.5–7 However, most cases are subclinical, and symptomatic cardiac involvement is present in only about 5% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis.8 Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis has been described in case reports but is rare.9

The clinical manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis depend on the location and extent of granulomatous inflammation. In a necropsy study of 113 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, the left ventricular free wall was the most common location, followed by the interventricular septum.10

3. How does cardiac sarcoidosis most commonly present?

- Conduction abnormalities

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Cardiomyopathy

- Sudden death

- None of the above

Common presentations of cardiac sarcoidosis include conduction system disease and arrhythmias (which can sometimes result in sudden death), and heart failure.

Conduction abnormalities due to granulomas (in the active phase of sarcoidosis) and fibrosis (in the fibrotic phase) in the atrioventricular node or bundle of His are the most common presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis.9 These lesions may result in relatively benign first-degree heart block or may be as potentially devastating as complete heart block.

In almost all patients with conduction abnormalities, the basal interventricular septum is involved.11 Patients who develop complete heart block from sarcoidosis tend to be younger than those with idiopathic heart block. Therefore, complete heart block in a young patient should raise the possibility of this diagnosis. 12

Ventricular tachycardia (sustained or nonsustained) and ventricular premature beats are the second most common presentation. Up to 22% of patients with sarcoidosis have electrocardiographic evidence of ventricular arrythmias. 13 The cause is believed to be myocardial scar tissue resulting from the sarcoid granulomas, leading to electrical reentry.14 Sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or conduction blocks accounts for 25% to 65% of deaths from cardiac sarcoidosis.9,15,16

Heart failure may result from sarcoidosis when there is extensive granulomatous disease in the myocardium. Depending on the location of the granulomas, both systolic and diastolic dysfunction can occur. In severe cases, extensive granulomas can cause left ventricular aneurysms.

The diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis as the cause of heart failure can be difficult to establish, especially in patients without evidence of sarcoidosis elsewhere. Such patients are often given a diagnosis of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. However, compared with patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, those with cardiac sarcoidosis have a greater incidence of advanced atrioventricular block, abnormal wall thickness, focal wall motion abnormalities, and perfusion defects of the anteroseptal and apical regions.17

Progressive heart failure is the second most frequent cause of death (after sudden death) and accounts for 25% to 75% of sarcoid-related cardiac deaths.9,18,19

DIAGNOSING CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

4. How is cardiac sarcoidosis diagnosed?

- Electrocardiography

- Echocardiography

- Computed tomography

- Endomyocardial biopsy

- There are no guidelines for diagnosis

Given the variable extent and location of granulomas in sarcoidosis, the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis is often challenging.

To make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in general, the American Thoracic Society2 says that the clinical picture should be compatible with this diagnosis, noncaseating granulomas should be histologically confirmed, and other diseases capable of producing a similar clinical or histologic picture should be excluded.

A newer diagnostic tool, the Sarcoidosis Three-Dimensional Assessment Instrument,20 incorporates two earlier tools.20,21 It assesses three axes: organ involvement, sarcoidosis severity, and sarcoidosis activity and categorizes the diagnosis of sarcoidosis as “definite,” “probable,” or “possible.”20

In Japan, where sarcoidosis is more common, the Ministry of Health and Welfare22 says that cardiac sarcoidosis can be diagnosed histologically if operative or endomyocardial biopsy specimens contain noncaseating granuloma. In addition, the diagnosis can be suspected in patients who have a histologic diagnosis of extracardiac sarcoidosis if the first item in the list below and one or more of the rest are present:

- Complete right bundle branch block, left axis deviation, atrioventricular block, ventricular tachycardia, premature ventricular contractions (> grade 2 of the Lown classification), or Q or ST-T wave abnormalities

- Abnormal wall motion, regional wall thinning, or dilation of the left ventricle on echocardiography

- Perfusion defects on thallium 201 myocardial scintigraphy or abnormal accumulation of gallium citrate Ga 67 or technetium 99m on myocardial scintigraphy

- Abnormal intracardiac pressure, low cardiac output, or abnormal wall motion or depressed left ventricular ejection fraction on cardiac catheterization

- Nonspecific interstitial fibrosis or cellular infiltration on myocardial biopsy.

The current diagnostic guidelines from the American Thoracic Society2 and the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare22 and the Sarcoidosis Three-Dimensional Assessment Instrument,20 however, do not incorporate newer imaging studies as part of their criteria.

A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS

5. Endomyocardial biopsy often provides the definitive diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.

- True

- False

False. Endomyocardial biopsy often fails to reveal noncaseating granulomas, which have a patchy distribution.13 Table 2 summarizes the accuracy of tests for cardiac sarcoidosis.

Electrocardiography is abnormal in up to 50% of patients with sarcoidosis,23 reflecting the conduction disease or arrhythmias commonly seen in cardiac involvement.

Chest radiography classically shows hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial disease, and may show cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion, or left ventricular aneurysm.

Echocardiography is nonspecific for sarcoid disease, but granulomatous involvement and scar tissue of cardiac tissue may appear hyperechogenic, particularly in the ventricular septum or left ventricular free wall.24

Angiography. Primary sarcoidosis rarely involves the coronary arteries,25 so angiography is most useful in excluding the diagnosis of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.

Radionuclide imaging with thallium 201 in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis may be useful to suggest myocardial involvement and to exclude cardiac dysfunction secondary to coronary artery disease. Segmental areas with defective thallium 201 uptake correspond to fibrogranulomatous tissue. In resting images, the pattern may be similar to that seen in coronary artery disease. However, during exercise, perfusion defects increase in patients who have ischemia but actually decrease in those with cardiac sarcoidosis.26

Nevertheless, some conclude that thallium scanning is too nonspecific for it to be used as a diagnostic or screening test.27,28 The combined use of thallium 201 and gallium 67 may better detect cardiac sarcoidosis, as gallium is taken up in areas of active inflammation.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose F 18 (FDG), with the patient fasting, appears to be useful in detecting the early inflammation of cardiac sarcoidosis29–34 and monitoring disease activity.30,31 FDG is a glucose analogue that is taken up by granulomatous tissue in the myocardium.34 The uptake in cardiac sarcoidosis is in a focal distribution.30,31,34 The abnormal FDG uptake resolves with steroid treatment.31,32

MRI has promise for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis. With gadolinium contrast, MRI has superior image resolution and can detect cardiac involvement early in its course.27,29,35–44

Inflammation of the myocardium due to sarcoid involvement appears as focal zones of increased signal intensity on both T2-weighted and early gadolinium T1-weighted images. Late myocardial enhancement after gadolinium infusion is the most typical finding of cardiac sarcoidosis on MRI, and likely represents fibrogranulomatous tissue.27 Delayed gadolinium enhancement is also seen in myocardial infarction but differs in its distribution.1,35,45 Cardiac sarcoidosis most commonly affects the basal and lateral segments. In one study, the finding of delayed enhancement had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 78%,1,27 though it may not sufficiently differentiate active inflammation from scar.30

Like FDG-PET, MRI has also been shown to be useful for monitoring treatment.33,46 However, PET is more useful for follow-up in patients who receive a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, in whom MRI is contraindicated. One case report29 described using both delayed-enhancement MRI and FDG-PET to diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis.

TREATMENT

6. How is cardiac sarcoidosis currently treated?

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- Corticosteroids

- Heart transplantation

- All of the above

- None of the above

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis, as they attenuate the characteristic inflammation and fibrosis of sarcoid granulomas. The goal is to prevent compromise of cardiac structure or function.47 Although most of the supporting data are anecdotal, steroids have been shown to improve ventricular contractility,48 arrhythmias,49 and conduction abnormalities.50 MRI and FDG-PET studies have shown cardiac lesions resolving after steroids were started.31,45,46

The optimal dosage remains unknown. Initial doses of 30 to 60 mg daily, gradually tapered over 6 to 12 months to maintenance doses of 5 to 10 mg daily, have been effective.45,51

Relapses are common and require vigilant monitoring.

Alternative agents such as cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan),52 methotrexate (Rheumatrex), 53 and cyclosporine (Sandimmune)54 can be given to patients whose disease does not respond to corticosteroids or who cannot tolerate their side effects.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or conduction block accounts for 30% to 65% of deaths in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.10 The rates of recurrent ventricular tachycardia and sudden death are high, even with antiarrhythmic drug therapy.55

Although experience with implantable cardiac defibrillators is limited in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis,55–58 some have argued that they be strongly considered to prevent sudden cardiac death in this high-risk group.57,58

Heart transplantation

The largest body of data on transplantation comes from the United Network for Organ Sharing database. In the 65 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis who underwent cardiac transplantation in the 18 years from October 1987 to September 2005, the 1-year post-transplant survival rate was 88%, which was better than in patients with all other diagnoses (85%). The 5-year survival rate was 80%.59,60

Recurrence of sarcoidosis within the cardiac allograft and transmission of sarcoidosis from donor to recipient have both been documented after heart transplantation.61,62

CAUSES OF DEATH

7. What is the most common cause of death in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis?

- Respiratory failure

- Conduction disturbances

- Progressive heart failure

- Ventricular tachyarrhythmias

- None of the above

The prognosis of symptomatic cardiac sarcoidosis is not well defined, owing to the variable extent and severity of the disease. The mortality rate in sarcoidosis without cardiac involvement is about 1% to 5% per year.63,64 Cardiac involvement portends a worse prognosis, with a 55% survival rate at 5 years and 44% at 10 years.17,65 Most patients in the reported series ultimately died of cardiac complications of sarcoidosis, including ventricular tachyarrhythmias, conduction disturbances, and progressive cardiomyopathy.10,17

Since corticosteroids, pacemakers, and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators have begun to be used, the cause of death has shifted from sudden death to progressive heart failure.66

CASE CONTINUED

Electrophysiologic testing revealed inducible monomorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia. The patient subsequently had a biventricular cardioverter-defibrillator implanted. He was started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a beta-blocker for his heart failure. Further imaging of his chest and abdomen revealed lesions in his thyroid and liver. As of this writing, he is undergoing further workup. Because of active infection with Clostridium difficile, steroid therapy was deferred.

- Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1683–1690.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736–755.

- Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145:234–241.

- Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, et al. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1976; 278:455–469.

- Chapelon-Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:315–334.

- Iwai K, Sekiguti M, Hosoda Y, et al. Racial difference in cardiac sarcoidosis incidence observed at autopsy. Sarcoidosis 1994; 11:26–31.

- Thomsen TK, Eriksson T. Myocardial sarcoidosis in forensic medicine. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1999; 20:52–56.

- Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Buckley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation 1978; 58:1204–1211.

- Roberts WC, McAllister HA, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med 1977; 63:86–108.

- Bargout R, Kelly R. Sarcoid heart disease: clinical course and treatment. Int J Cardiol 2004; 97:173–182.

- Abeler V. Sarcoidosis of the cardiac conducting system. Am Heart J 1979; 97:701–707.

- Fleming HA, Bailey SM. Sarcoid heart disease. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1981; 15:245–253.

- Sekiguchi M, Numao Y, Imai M, Furuie T, Mikami R. Clinical and histological profile of sarcoidosis of the heart and acute idiopathic myocarditis. Concepts through a study employing endomyocardial biopsy. I. Sarcoidosis. Jpn Circ J 1980; 44:249–263.

- Furushima H, Chinushi M, Sugiura H, Kasai H, Washizuka T, Aizawa Y. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia associated with cardiac sarcoidosis: its mechanisms and outcome. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:217–222.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:1006–1010.

- Reuhl J, Schneider M, Sievert H, Lutz FU, Zieger G. Myocardial sarcoidosis as a rare cause of sudden cardiac death. Forensic Sci Int 1997; 89:145–153.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiramitsu S, et al. Comparison of clinical features and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82:537–540.

- Fleming H. Cardiac sarcoidosis. In:James DG, editor. Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. New York, NY: Dekker 1994; 73:323–334.

- Padilla M. Cardiac sarcoidosis. In:Baughman R, editor. Lung Biology in Health and Disease (Sarcoidosis), vol 210. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group; 2006:515–552.

- Judson MA. A proposed solution to the clinical assessment of sarcoidosis: the sarcoidosis three-dimensional assessment instrument (STAI). Med Hypotheses 2007; 68:1080–1087.

- Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Terrin ML, Yeager H. Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:75–86.

- Hiraga H, Yuwai K, Hiroe M, et al. Guideline for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Study report of diffuse pulmonary diseases. Tokyo, Japan: The Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1993:23–24 (in Japanese).

- Stein E, Jackler I, Stimmel B, Stein W, Siltzbach LE. Asymptomatic electrocardiographic alterations in sarcoidosis. Am Heart J 1973; 86:474–477.

- Fahy GJ, Marwick T, McCreery CJ, Quigley PJ, Maurer BJ. Doppler echocardiographic detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest 1996; 109:62–66.

- Butany J, Bahl NE, Morales K, et al. The intricacies of cardiac sarcoidosis: a case report involving the coronary arteries and a review of the literature. Cardiovasc Pathol 2006; 15:222–227.

- Haywood LJ, Sharma OP, Siegel ME, et al. Detection of myocardial sarcoidosis by thallium-201 imaging. J Natl Med Assoc 1982; 74:959–964.

- Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, Kubo S, et al. Effectiveness of delayed enhanced MRI for identification of cardiac sarcoidosis: comparison with radionuclide imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185:110–115.

- Kinney EL, Caldwell JW. Do thallium myocardial perfusion scan abnormalities predict survival in sarcoid patients without cardiac symptoms? Angiology 1990; 41:573–576.

- Pandya C, Brunken RC, Tchou P, Schoenhagen P, Culver DA. Detecting cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis: a call for prospective studies of newer imaging techniques. Eur Respir J 2007; 29:418–422.

- Ohira H, Tsujino I, Ishimaru S, et al. Myocardial imaging with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008; 35:933–941.

- Yamagishi H, Shirai N, Takagi M, et al. Identification of cardiac sarcoidosis with 13N-NH3/18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 2003; 44:1030–1036.

- Takeda N, Yokoyama I, Hiroi Y, et al. Positron emission tomography predicted recovery of complete A-V nodal dysfunction in a patient with cardiac sarcoidosis. Circulation 2002; 105:1144–1145.

- Ishimaru S, Tsujino I, Takei T, et al. Focal uptake on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography images indicates cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J 2005; 26:1538–1543.

- Okumura W, Iwasaki T, Toyama T, et al. Usefulness of fasting 18F-FDG PET in identification of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med 2004; 45:1989–1998.

- Schulz-Menger J, Wassmuth R, Abdel-Aty H, et al. Patterns of myocardial inflammation and scarring in sarcoidosis as assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Heart 2006; 92:399–400.

- Kiuchi S, Teraoka K, Koizumi K, Takazawa K, Yamashina A. Usefulness of late gadolinium enhancement combined with MRI and 67-Ga scintigraphy in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and disease activity evaluation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2007; 23:237–241.

- Matsuki M, Matsuo M. MR findings of myocardial sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol 2000; 55:323–325.

- Inoue S, Shimada T, Murakami Y. Clinical significance of gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced MRI for detection of myocardial lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol 1999; 54:70–72.

- Vignaux O, Dhote R, Dudoc D, et al. Detection of myocardial involvement in patients with sarcoidosis applying T2-weighted, contrastenhanced, and cine magnetic resonance imaging: initial results of a prospective study. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2002; 26:762–767.

- Vignaux O. Cardiac sarcoidosis: spectrum of MRI features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184:249–254.

- Smedema JP, Snoep G, Van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1683–1690.

- Doherty MJ, Kumar SK, Nicholson AA, McGivern DV. Cardiac sarcoidosis: the value of magnetic resonance imagine in diagnosis and assessment of response to treatment. Respir Med 1998; 92:697–699.

- Smedema JP, Truter R, de Klerk PA, Zaaiman L, White L, Doubell AF. Cardiac sarcoidosis evaluated with gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance and contrast-enhanced 64-slice computed tomography. Int J Cardiol 2006; 112:261–263.

- Kanao S, Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, et al. Demonstration of cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis by contrast-enhanced multislice computed tomography and delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29:745–748.

- Vignaux O, Dhote R, Duboc D, et al. Clinical significance of myocardial magnetic resonance abnormalities in patients with sarcoidosis: a 1-year follow-up study. Chest 2002; 122:1895–1901.

- Shimada T, Shimada K, Sakane T, et al. Diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and evaluation of the effects of steroid therapy by gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Med 2001; 110:520–527.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, et al. Prognostic determinants of longterm survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:1006–1010.

- Ishikawa T, Kondoh H, Nakagawa S, Koiwaya Y, Tanaka K. Steroid therapy in cardiac sarcoidosis. Increased left ventricular contractility concomitant with electrocardiographic improvement after prednisolone. Chest 1984; 85:445–447.

- Walsh MJ. Systemic sarcoidosis with refractory ventricular tachycardia and heart failure. Br Heart J 1978; 40:931–933.

- Lash R, Coker J, Wong BY. Treatment of heart block due to sarcoid heart disease. J Electrocardiol 1979; 12:325–329.

- Johns CJ, Schonfeld SA, Scott PP, Zachary JB, MacGregor MI. Longitudinal study of chronic sarcoidosis with low-dose maintenance corticosteroid therapy. Outcome and implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986; 465:702–712.

- Demeter SL. Myocardial sarcoidosis unresponsive to steroids. Treatment with cyclophosphamide. Chest 1988; 94:202–203.

- Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:846–851.

- York EL, Kovithavongs T, Man SF, Rebuck AS, Sproule BJ. Cyclosporine and chronic sarcoidosis. Chest 1990; 98:1026–1029.

- Winters SL, Cohen M, Greenberg S, et al. Sustained ventricular tachycardia associated with sarcoidosis: assessment of the underlying cardiac anatomy and the prospective utility of programmed ventricular stimulation, drug therapy and an implantable antitachycardia device. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18:937–943.

- Bajaj AK, Kopelman HA, Echt DS. Cardiac sarcoidosis with sudden death: treatment with automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Am Heart J 1988; 116:557–560.

- Paz HL, McCormick DJ, Kutalek SP, Patchefsky A. The automated implantable cardiac defibrillator. Prophylaxis in cardiac sarcoidosis. Chest 1994; 106:1603–1607.

- Becker D, Berger E, Chmielewski C. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a report of four cases with ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1990; 1:214–219.

- Zaidi AR, Zaidi A, Vaitkus PT. Outcome of heart transplantation in patients with sarcoid cardiomyopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007; 26:714–717.

- Valantine HA, Tazelaar HD, Macoviak J, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: response to steroids and transplantation. J Heart Transplant 1987; 6:244–250.

- Oni AA, Hershberger RE, Norman DJ, et al. Recurrence of sarcoidosis in a cardiac allograft: control with augmented corticosteroids. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992; 11:367–369.

- Burke WM, Keogh A, Maloney PJ, Delprado W, Bryant DH, Spratt P. Transmission of sarcoidosis via cardiac transplantation. Lancet 1990; 336:1579.

- Johns CJ, Schonfeld SA, Scott PP, Zachary JB, MacGregor MI. Longitudinal study of chronic sarcoidosis with low-dose maintenance corticosteroid therapy. Outcome and complications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986; 465:702–712.

- Gideon NM, Mannino DM. Sarcoidosis mortality in the United States 1979–1991: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Med 1996; 100:423–427.

- Fleming HA, Bailey SM. The prognosis of sarcoid heart disease in the United Kingdom. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986; 465:543–550.

- Takada K, Ina Y, Yamamoto M, Satoh T, Morishita M. Prognosis after pacemaker implantation in cardiac sarcoidosis in Japan. Clinical evaluation of corticosteroid therapy. Sarcoidosis 1994; 11:113–117.

A 61-year-old white man presents with progressive fatigue, which began several months ago and has accelerated in severity over the past week. He says he has had no shortness of breath, chest pain, or symptoms of heart failure, but he has noticed a decrease in exertional capacity and now has trouble completing his daily 5-mile walk.

He saw his primary physician, who obtained an electrocardiogram that showed a new left bundle branch block. Transthoracic echocardiography indicated that his left ventricular ejection fraction, which was 60% a year earlier, was now 35%.

He has hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Although he was previously morbidly obese, he has lost more than 100 pounds with diet and exercise over the past 10 years. He also used to smoke; in fact, he has a 30-pack-year history, but he quit in 1987. He has a family history of premature coronary artery disease.

Physical examination. His heart rate is 75 beats per minute, blood pressure 142/85 mm Hg, and blood oxygen saturation 96% while breathing room air. He weighs 169 pounds (76.6 kg) and he is 6 feet tall (182.9 cm), so his body mass index is 22.9 kg/m2.

Electrocardiography reveals sinus rhythm with a left bundle branch block and left axis deviation (Figure 1), which were not present 1 year ago.

Chest roentgenography is normal.

A WORRISOME PICTURE

1. Which of the following is associated with left bundle branch block?

- Myocardial injury

- Hypertension

- Aortic stenosis

- Intrinsic conduction system disease

- All of the above

All of the above are true. For left bundle branch block to be diagnosed, the rhythm must be supraventricular and the QRS duration must be 120 ms or more. There should be a QS or RS complex in V1 and a monophasic R wave in I and V6. Also, the T wave should be deflected opposite the terminal deflection of the QRS complex. This is known as appropriate T-wave discordance with bundle branch block. A concordant T wave is nonspecific but suggests ischemia or myocardial infarction.

Potential causes of a new left bundle branch block include hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, aortic stenosis, and conduction system disease. A new left bundle branch block with a concomitant decrease in ejection fraction, especially in a patient with cardiac risk factors, is very worrisome, raising the possibility of ischemic heart disease.

MORE CARDIAC TESTING

The patient undergoes more cardiac testing.

Transthoracic echocardiography is done again. The left ventricle is normal in size, but the ejection fraction is 35%. In addition, stage 1 diastolic dysfunction (abnormal relaxation) and evidence of mechanical dyssynchrony (disruption in the normal sequence of activation and contraction of segments of the left ventricular wall) are seen. The right ventricle is normal in size and function. There is trivial mitral regurgitation and mild tricuspid regurgitation with normal right-sided pressures.

A gated rubidium-82 dipyridamole stress test yields no evidence of a fixed or reversible perfusion defect.

Left heart catheterization reveals angiographically normal coronary arteries.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a moderately hypertrophied left ventricle with moderately to severely depressed systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction 27%). The left ventricle appears dyssynchronous. Delayed-enhancement imaging reveals patchy delayed enhancement in the basal septum and the basal inferolateral walls. These findings suggest cardiac sarcoidosis, with a sensitivity of nearly 100% and a specificity of approximately 78%.1

SARCOIDOSIS IS A MULTISYSTEM DISEASE

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease characterized by noncaseating granulomas. Almost any organ can be affected, but it most commonly involves the respiratory and lymphatic systems.2 Although infectious, environmental, and genetic factors have been implicated, the cause remains unknown. The prevalence is approximately 20 per 100,000, being higher in black3 and Japanese 4 populations.

CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

2. What percentage of patients with sarcoidosis have cardiac involvement?

- 10%–20%

- 20%–30%

- 50%

- 80%

Cardiac involvement is seen in 20% to 30% of patients with sarcoidosis.5–7 However, most cases are subclinical, and symptomatic cardiac involvement is present in only about 5% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis.8 Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis has been described in case reports but is rare.9

The clinical manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis depend on the location and extent of granulomatous inflammation. In a necropsy study of 113 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, the left ventricular free wall was the most common location, followed by the interventricular septum.10

3. How does cardiac sarcoidosis most commonly present?

- Conduction abnormalities

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Cardiomyopathy

- Sudden death

- None of the above

Common presentations of cardiac sarcoidosis include conduction system disease and arrhythmias (which can sometimes result in sudden death), and heart failure.

Conduction abnormalities due to granulomas (in the active phase of sarcoidosis) and fibrosis (in the fibrotic phase) in the atrioventricular node or bundle of His are the most common presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis.9 These lesions may result in relatively benign first-degree heart block or may be as potentially devastating as complete heart block.

In almost all patients with conduction abnormalities, the basal interventricular septum is involved.11 Patients who develop complete heart block from sarcoidosis tend to be younger than those with idiopathic heart block. Therefore, complete heart block in a young patient should raise the possibility of this diagnosis. 12

Ventricular tachycardia (sustained or nonsustained) and ventricular premature beats are the second most common presentation. Up to 22% of patients with sarcoidosis have electrocardiographic evidence of ventricular arrythmias. 13 The cause is believed to be myocardial scar tissue resulting from the sarcoid granulomas, leading to electrical reentry.14 Sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or conduction blocks accounts for 25% to 65% of deaths from cardiac sarcoidosis.9,15,16

Heart failure may result from sarcoidosis when there is extensive granulomatous disease in the myocardium. Depending on the location of the granulomas, both systolic and diastolic dysfunction can occur. In severe cases, extensive granulomas can cause left ventricular aneurysms.

The diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis as the cause of heart failure can be difficult to establish, especially in patients without evidence of sarcoidosis elsewhere. Such patients are often given a diagnosis of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. However, compared with patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, those with cardiac sarcoidosis have a greater incidence of advanced atrioventricular block, abnormal wall thickness, focal wall motion abnormalities, and perfusion defects of the anteroseptal and apical regions.17

Progressive heart failure is the second most frequent cause of death (after sudden death) and accounts for 25% to 75% of sarcoid-related cardiac deaths.9,18,19

DIAGNOSING CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

4. How is cardiac sarcoidosis diagnosed?

- Electrocardiography

- Echocardiography

- Computed tomography

- Endomyocardial biopsy

- There are no guidelines for diagnosis

Given the variable extent and location of granulomas in sarcoidosis, the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis is often challenging.

To make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in general, the American Thoracic Society2 says that the clinical picture should be compatible with this diagnosis, noncaseating granulomas should be histologically confirmed, and other diseases capable of producing a similar clinical or histologic picture should be excluded.

A newer diagnostic tool, the Sarcoidosis Three-Dimensional Assessment Instrument,20 incorporates two earlier tools.20,21 It assesses three axes: organ involvement, sarcoidosis severity, and sarcoidosis activity and categorizes the diagnosis of sarcoidosis as “definite,” “probable,” or “possible.”20

In Japan, where sarcoidosis is more common, the Ministry of Health and Welfare22 says that cardiac sarcoidosis can be diagnosed histologically if operative or endomyocardial biopsy specimens contain noncaseating granuloma. In addition, the diagnosis can be suspected in patients who have a histologic diagnosis of extracardiac sarcoidosis if the first item in the list below and one or more of the rest are present:

- Complete right bundle branch block, left axis deviation, atrioventricular block, ventricular tachycardia, premature ventricular contractions (> grade 2 of the Lown classification), or Q or ST-T wave abnormalities

- Abnormal wall motion, regional wall thinning, or dilation of the left ventricle on echocardiography

- Perfusion defects on thallium 201 myocardial scintigraphy or abnormal accumulation of gallium citrate Ga 67 or technetium 99m on myocardial scintigraphy

- Abnormal intracardiac pressure, low cardiac output, or abnormal wall motion or depressed left ventricular ejection fraction on cardiac catheterization

- Nonspecific interstitial fibrosis or cellular infiltration on myocardial biopsy.

The current diagnostic guidelines from the American Thoracic Society2 and the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare22 and the Sarcoidosis Three-Dimensional Assessment Instrument,20 however, do not incorporate newer imaging studies as part of their criteria.

A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS

5. Endomyocardial biopsy often provides the definitive diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.

- True

- False

False. Endomyocardial biopsy often fails to reveal noncaseating granulomas, which have a patchy distribution.13 Table 2 summarizes the accuracy of tests for cardiac sarcoidosis.

Electrocardiography is abnormal in up to 50% of patients with sarcoidosis,23 reflecting the conduction disease or arrhythmias commonly seen in cardiac involvement.

Chest radiography classically shows hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial disease, and may show cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion, or left ventricular aneurysm.

Echocardiography is nonspecific for sarcoid disease, but granulomatous involvement and scar tissue of cardiac tissue may appear hyperechogenic, particularly in the ventricular septum or left ventricular free wall.24

Angiography. Primary sarcoidosis rarely involves the coronary arteries,25 so angiography is most useful in excluding the diagnosis of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.

Radionuclide imaging with thallium 201 in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis may be useful to suggest myocardial involvement and to exclude cardiac dysfunction secondary to coronary artery disease. Segmental areas with defective thallium 201 uptake correspond to fibrogranulomatous tissue. In resting images, the pattern may be similar to that seen in coronary artery disease. However, during exercise, perfusion defects increase in patients who have ischemia but actually decrease in those with cardiac sarcoidosis.26

Nevertheless, some conclude that thallium scanning is too nonspecific for it to be used as a diagnostic or screening test.27,28 The combined use of thallium 201 and gallium 67 may better detect cardiac sarcoidosis, as gallium is taken up in areas of active inflammation.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose F 18 (FDG), with the patient fasting, appears to be useful in detecting the early inflammation of cardiac sarcoidosis29–34 and monitoring disease activity.30,31 FDG is a glucose analogue that is taken up by granulomatous tissue in the myocardium.34 The uptake in cardiac sarcoidosis is in a focal distribution.30,31,34 The abnormal FDG uptake resolves with steroid treatment.31,32

MRI has promise for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis. With gadolinium contrast, MRI has superior image resolution and can detect cardiac involvement early in its course.27,29,35–44

Inflammation of the myocardium due to sarcoid involvement appears as focal zones of increased signal intensity on both T2-weighted and early gadolinium T1-weighted images. Late myocardial enhancement after gadolinium infusion is the most typical finding of cardiac sarcoidosis on MRI, and likely represents fibrogranulomatous tissue.27 Delayed gadolinium enhancement is also seen in myocardial infarction but differs in its distribution.1,35,45 Cardiac sarcoidosis most commonly affects the basal and lateral segments. In one study, the finding of delayed enhancement had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 78%,1,27 though it may not sufficiently differentiate active inflammation from scar.30

Like FDG-PET, MRI has also been shown to be useful for monitoring treatment.33,46 However, PET is more useful for follow-up in patients who receive a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, in whom MRI is contraindicated. One case report29 described using both delayed-enhancement MRI and FDG-PET to diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis.

TREATMENT

6. How is cardiac sarcoidosis currently treated?

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- Corticosteroids

- Heart transplantation

- All of the above

- None of the above

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis, as they attenuate the characteristic inflammation and fibrosis of sarcoid granulomas. The goal is to prevent compromise of cardiac structure or function.47 Although most of the supporting data are anecdotal, steroids have been shown to improve ventricular contractility,48 arrhythmias,49 and conduction abnormalities.50 MRI and FDG-PET studies have shown cardiac lesions resolving after steroids were started.31,45,46

The optimal dosage remains unknown. Initial doses of 30 to 60 mg daily, gradually tapered over 6 to 12 months to maintenance doses of 5 to 10 mg daily, have been effective.45,51

Relapses are common and require vigilant monitoring.

Alternative agents such as cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan),52 methotrexate (Rheumatrex), 53 and cyclosporine (Sandimmune)54 can be given to patients whose disease does not respond to corticosteroids or who cannot tolerate their side effects.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or conduction block accounts for 30% to 65% of deaths in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.10 The rates of recurrent ventricular tachycardia and sudden death are high, even with antiarrhythmic drug therapy.55

Although experience with implantable cardiac defibrillators is limited in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis,55–58 some have argued that they be strongly considered to prevent sudden cardiac death in this high-risk group.57,58

Heart transplantation

The largest body of data on transplantation comes from the United Network for Organ Sharing database. In the 65 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis who underwent cardiac transplantation in the 18 years from October 1987 to September 2005, the 1-year post-transplant survival rate was 88%, which was better than in patients with all other diagnoses (85%). The 5-year survival rate was 80%.59,60

Recurrence of sarcoidosis within the cardiac allograft and transmission of sarcoidosis from donor to recipient have both been documented after heart transplantation.61,62

CAUSES OF DEATH

7. What is the most common cause of death in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis?

- Respiratory failure

- Conduction disturbances

- Progressive heart failure

- Ventricular tachyarrhythmias

- None of the above

The prognosis of symptomatic cardiac sarcoidosis is not well defined, owing to the variable extent and severity of the disease. The mortality rate in sarcoidosis without cardiac involvement is about 1% to 5% per year.63,64 Cardiac involvement portends a worse prognosis, with a 55% survival rate at 5 years and 44% at 10 years.17,65 Most patients in the reported series ultimately died of cardiac complications of sarcoidosis, including ventricular tachyarrhythmias, conduction disturbances, and progressive cardiomyopathy.10,17

Since corticosteroids, pacemakers, and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators have begun to be used, the cause of death has shifted from sudden death to progressive heart failure.66

CASE CONTINUED

Electrophysiologic testing revealed inducible monomorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia. The patient subsequently had a biventricular cardioverter-defibrillator implanted. He was started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a beta-blocker for his heart failure. Further imaging of his chest and abdomen revealed lesions in his thyroid and liver. As of this writing, he is undergoing further workup. Because of active infection with Clostridium difficile, steroid therapy was deferred.

A 61-year-old white man presents with progressive fatigue, which began several months ago and has accelerated in severity over the past week. He says he has had no shortness of breath, chest pain, or symptoms of heart failure, but he has noticed a decrease in exertional capacity and now has trouble completing his daily 5-mile walk.

He saw his primary physician, who obtained an electrocardiogram that showed a new left bundle branch block. Transthoracic echocardiography indicated that his left ventricular ejection fraction, which was 60% a year earlier, was now 35%.

He has hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. Although he was previously morbidly obese, he has lost more than 100 pounds with diet and exercise over the past 10 years. He also used to smoke; in fact, he has a 30-pack-year history, but he quit in 1987. He has a family history of premature coronary artery disease.

Physical examination. His heart rate is 75 beats per minute, blood pressure 142/85 mm Hg, and blood oxygen saturation 96% while breathing room air. He weighs 169 pounds (76.6 kg) and he is 6 feet tall (182.9 cm), so his body mass index is 22.9 kg/m2.

Electrocardiography reveals sinus rhythm with a left bundle branch block and left axis deviation (Figure 1), which were not present 1 year ago.

Chest roentgenography is normal.

A WORRISOME PICTURE

1. Which of the following is associated with left bundle branch block?

- Myocardial injury

- Hypertension

- Aortic stenosis

- Intrinsic conduction system disease

- All of the above

All of the above are true. For left bundle branch block to be diagnosed, the rhythm must be supraventricular and the QRS duration must be 120 ms or more. There should be a QS or RS complex in V1 and a monophasic R wave in I and V6. Also, the T wave should be deflected opposite the terminal deflection of the QRS complex. This is known as appropriate T-wave discordance with bundle branch block. A concordant T wave is nonspecific but suggests ischemia or myocardial infarction.

Potential causes of a new left bundle branch block include hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, aortic stenosis, and conduction system disease. A new left bundle branch block with a concomitant decrease in ejection fraction, especially in a patient with cardiac risk factors, is very worrisome, raising the possibility of ischemic heart disease.

MORE CARDIAC TESTING

The patient undergoes more cardiac testing.

Transthoracic echocardiography is done again. The left ventricle is normal in size, but the ejection fraction is 35%. In addition, stage 1 diastolic dysfunction (abnormal relaxation) and evidence of mechanical dyssynchrony (disruption in the normal sequence of activation and contraction of segments of the left ventricular wall) are seen. The right ventricle is normal in size and function. There is trivial mitral regurgitation and mild tricuspid regurgitation with normal right-sided pressures.

A gated rubidium-82 dipyridamole stress test yields no evidence of a fixed or reversible perfusion defect.

Left heart catheterization reveals angiographically normal coronary arteries.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a moderately hypertrophied left ventricle with moderately to severely depressed systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction 27%). The left ventricle appears dyssynchronous. Delayed-enhancement imaging reveals patchy delayed enhancement in the basal septum and the basal inferolateral walls. These findings suggest cardiac sarcoidosis, with a sensitivity of nearly 100% and a specificity of approximately 78%.1

SARCOIDOSIS IS A MULTISYSTEM DISEASE

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease characterized by noncaseating granulomas. Almost any organ can be affected, but it most commonly involves the respiratory and lymphatic systems.2 Although infectious, environmental, and genetic factors have been implicated, the cause remains unknown. The prevalence is approximately 20 per 100,000, being higher in black3 and Japanese 4 populations.

CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

2. What percentage of patients with sarcoidosis have cardiac involvement?

- 10%–20%

- 20%–30%

- 50%

- 80%

Cardiac involvement is seen in 20% to 30% of patients with sarcoidosis.5–7 However, most cases are subclinical, and symptomatic cardiac involvement is present in only about 5% of patients with systemic sarcoidosis.8 Isolated cardiac sarcoidosis has been described in case reports but is rare.9

The clinical manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis depend on the location and extent of granulomatous inflammation. In a necropsy study of 113 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis, the left ventricular free wall was the most common location, followed by the interventricular septum.10

3. How does cardiac sarcoidosis most commonly present?

- Conduction abnormalities

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Cardiomyopathy

- Sudden death

- None of the above

Common presentations of cardiac sarcoidosis include conduction system disease and arrhythmias (which can sometimes result in sudden death), and heart failure.

Conduction abnormalities due to granulomas (in the active phase of sarcoidosis) and fibrosis (in the fibrotic phase) in the atrioventricular node or bundle of His are the most common presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis.9 These lesions may result in relatively benign first-degree heart block or may be as potentially devastating as complete heart block.

In almost all patients with conduction abnormalities, the basal interventricular septum is involved.11 Patients who develop complete heart block from sarcoidosis tend to be younger than those with idiopathic heart block. Therefore, complete heart block in a young patient should raise the possibility of this diagnosis. 12

Ventricular tachycardia (sustained or nonsustained) and ventricular premature beats are the second most common presentation. Up to 22% of patients with sarcoidosis have electrocardiographic evidence of ventricular arrythmias. 13 The cause is believed to be myocardial scar tissue resulting from the sarcoid granulomas, leading to electrical reentry.14 Sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or conduction blocks accounts for 25% to 65% of deaths from cardiac sarcoidosis.9,15,16

Heart failure may result from sarcoidosis when there is extensive granulomatous disease in the myocardium. Depending on the location of the granulomas, both systolic and diastolic dysfunction can occur. In severe cases, extensive granulomas can cause left ventricular aneurysms.

The diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis as the cause of heart failure can be difficult to establish, especially in patients without evidence of sarcoidosis elsewhere. Such patients are often given a diagnosis of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. However, compared with patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, those with cardiac sarcoidosis have a greater incidence of advanced atrioventricular block, abnormal wall thickness, focal wall motion abnormalities, and perfusion defects of the anteroseptal and apical regions.17

Progressive heart failure is the second most frequent cause of death (after sudden death) and accounts for 25% to 75% of sarcoid-related cardiac deaths.9,18,19

DIAGNOSING CARDIAC SARCOIDOSIS

4. How is cardiac sarcoidosis diagnosed?

- Electrocardiography

- Echocardiography

- Computed tomography

- Endomyocardial biopsy

- There are no guidelines for diagnosis

Given the variable extent and location of granulomas in sarcoidosis, the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis is often challenging.

To make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis in general, the American Thoracic Society2 says that the clinical picture should be compatible with this diagnosis, noncaseating granulomas should be histologically confirmed, and other diseases capable of producing a similar clinical or histologic picture should be excluded.

A newer diagnostic tool, the Sarcoidosis Three-Dimensional Assessment Instrument,20 incorporates two earlier tools.20,21 It assesses three axes: organ involvement, sarcoidosis severity, and sarcoidosis activity and categorizes the diagnosis of sarcoidosis as “definite,” “probable,” or “possible.”20

In Japan, where sarcoidosis is more common, the Ministry of Health and Welfare22 says that cardiac sarcoidosis can be diagnosed histologically if operative or endomyocardial biopsy specimens contain noncaseating granuloma. In addition, the diagnosis can be suspected in patients who have a histologic diagnosis of extracardiac sarcoidosis if the first item in the list below and one or more of the rest are present:

- Complete right bundle branch block, left axis deviation, atrioventricular block, ventricular tachycardia, premature ventricular contractions (> grade 2 of the Lown classification), or Q or ST-T wave abnormalities

- Abnormal wall motion, regional wall thinning, or dilation of the left ventricle on echocardiography

- Perfusion defects on thallium 201 myocardial scintigraphy or abnormal accumulation of gallium citrate Ga 67 or technetium 99m on myocardial scintigraphy

- Abnormal intracardiac pressure, low cardiac output, or abnormal wall motion or depressed left ventricular ejection fraction on cardiac catheterization

- Nonspecific interstitial fibrosis or cellular infiltration on myocardial biopsy.

The current diagnostic guidelines from the American Thoracic Society2 and the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare22 and the Sarcoidosis Three-Dimensional Assessment Instrument,20 however, do not incorporate newer imaging studies as part of their criteria.

A DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS

5. Endomyocardial biopsy often provides the definitive diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis.

- True

- False

False. Endomyocardial biopsy often fails to reveal noncaseating granulomas, which have a patchy distribution.13 Table 2 summarizes the accuracy of tests for cardiac sarcoidosis.

Electrocardiography is abnormal in up to 50% of patients with sarcoidosis,23 reflecting the conduction disease or arrhythmias commonly seen in cardiac involvement.

Chest radiography classically shows hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial disease, and may show cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion, or left ventricular aneurysm.

Echocardiography is nonspecific for sarcoid disease, but granulomatous involvement and scar tissue of cardiac tissue may appear hyperechogenic, particularly in the ventricular septum or left ventricular free wall.24

Angiography. Primary sarcoidosis rarely involves the coronary arteries,25 so angiography is most useful in excluding the diagnosis of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.

Radionuclide imaging with thallium 201 in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis may be useful to suggest myocardial involvement and to exclude cardiac dysfunction secondary to coronary artery disease. Segmental areas with defective thallium 201 uptake correspond to fibrogranulomatous tissue. In resting images, the pattern may be similar to that seen in coronary artery disease. However, during exercise, perfusion defects increase in patients who have ischemia but actually decrease in those with cardiac sarcoidosis.26

Nevertheless, some conclude that thallium scanning is too nonspecific for it to be used as a diagnostic or screening test.27,28 The combined use of thallium 201 and gallium 67 may better detect cardiac sarcoidosis, as gallium is taken up in areas of active inflammation.

Positron-emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose F 18 (FDG), with the patient fasting, appears to be useful in detecting the early inflammation of cardiac sarcoidosis29–34 and monitoring disease activity.30,31 FDG is a glucose analogue that is taken up by granulomatous tissue in the myocardium.34 The uptake in cardiac sarcoidosis is in a focal distribution.30,31,34 The abnormal FDG uptake resolves with steroid treatment.31,32

MRI has promise for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis. With gadolinium contrast, MRI has superior image resolution and can detect cardiac involvement early in its course.27,29,35–44

Inflammation of the myocardium due to sarcoid involvement appears as focal zones of increased signal intensity on both T2-weighted and early gadolinium T1-weighted images. Late myocardial enhancement after gadolinium infusion is the most typical finding of cardiac sarcoidosis on MRI, and likely represents fibrogranulomatous tissue.27 Delayed gadolinium enhancement is also seen in myocardial infarction but differs in its distribution.1,35,45 Cardiac sarcoidosis most commonly affects the basal and lateral segments. In one study, the finding of delayed enhancement had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 78%,1,27 though it may not sufficiently differentiate active inflammation from scar.30

Like FDG-PET, MRI has also been shown to be useful for monitoring treatment.33,46 However, PET is more useful for follow-up in patients who receive a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, in whom MRI is contraindicated. One case report29 described using both delayed-enhancement MRI and FDG-PET to diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis.

TREATMENT

6. How is cardiac sarcoidosis currently treated?

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- Corticosteroids

- Heart transplantation

- All of the above

- None of the above

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis, as they attenuate the characteristic inflammation and fibrosis of sarcoid granulomas. The goal is to prevent compromise of cardiac structure or function.47 Although most of the supporting data are anecdotal, steroids have been shown to improve ventricular contractility,48 arrhythmias,49 and conduction abnormalities.50 MRI and FDG-PET studies have shown cardiac lesions resolving after steroids were started.31,45,46

The optimal dosage remains unknown. Initial doses of 30 to 60 mg daily, gradually tapered over 6 to 12 months to maintenance doses of 5 to 10 mg daily, have been effective.45,51

Relapses are common and require vigilant monitoring.

Alternative agents such as cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan),52 methotrexate (Rheumatrex), 53 and cyclosporine (Sandimmune)54 can be given to patients whose disease does not respond to corticosteroids or who cannot tolerate their side effects.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Sudden death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias or conduction block accounts for 30% to 65% of deaths in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis.10 The rates of recurrent ventricular tachycardia and sudden death are high, even with antiarrhythmic drug therapy.55

Although experience with implantable cardiac defibrillators is limited in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis,55–58 some have argued that they be strongly considered to prevent sudden cardiac death in this high-risk group.57,58

Heart transplantation

The largest body of data on transplantation comes from the United Network for Organ Sharing database. In the 65 patients with cardiac sarcoidosis who underwent cardiac transplantation in the 18 years from October 1987 to September 2005, the 1-year post-transplant survival rate was 88%, which was better than in patients with all other diagnoses (85%). The 5-year survival rate was 80%.59,60

Recurrence of sarcoidosis within the cardiac allograft and transmission of sarcoidosis from donor to recipient have both been documented after heart transplantation.61,62

CAUSES OF DEATH

7. What is the most common cause of death in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis?

- Respiratory failure

- Conduction disturbances

- Progressive heart failure

- Ventricular tachyarrhythmias

- None of the above

The prognosis of symptomatic cardiac sarcoidosis is not well defined, owing to the variable extent and severity of the disease. The mortality rate in sarcoidosis without cardiac involvement is about 1% to 5% per year.63,64 Cardiac involvement portends a worse prognosis, with a 55% survival rate at 5 years and 44% at 10 years.17,65 Most patients in the reported series ultimately died of cardiac complications of sarcoidosis, including ventricular tachyarrhythmias, conduction disturbances, and progressive cardiomyopathy.10,17

Since corticosteroids, pacemakers, and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators have begun to be used, the cause of death has shifted from sudden death to progressive heart failure.66

CASE CONTINUED

Electrophysiologic testing revealed inducible monomorphic sustained ventricular tachycardia. The patient subsequently had a biventricular cardioverter-defibrillator implanted. He was started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a beta-blocker for his heart failure. Further imaging of his chest and abdomen revealed lesions in his thyroid and liver. As of this writing, he is undergoing further workup. Because of active infection with Clostridium difficile, steroid therapy was deferred.

- Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1683–1690.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736–755.

- Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145:234–241.

- Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, et al. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1976; 278:455–469.

- Chapelon-Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:315–334.

- Iwai K, Sekiguti M, Hosoda Y, et al. Racial difference in cardiac sarcoidosis incidence observed at autopsy. Sarcoidosis 1994; 11:26–31.

- Thomsen TK, Eriksson T. Myocardial sarcoidosis in forensic medicine. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1999; 20:52–56.

- Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Buckley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation 1978; 58:1204–1211.

- Roberts WC, McAllister HA, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med 1977; 63:86–108.

- Bargout R, Kelly R. Sarcoid heart disease: clinical course and treatment. Int J Cardiol 2004; 97:173–182.

- Abeler V. Sarcoidosis of the cardiac conducting system. Am Heart J 1979; 97:701–707.

- Fleming HA, Bailey SM. Sarcoid heart disease. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1981; 15:245–253.

- Sekiguchi M, Numao Y, Imai M, Furuie T, Mikami R. Clinical and histological profile of sarcoidosis of the heart and acute idiopathic myocarditis. Concepts through a study employing endomyocardial biopsy. I. Sarcoidosis. Jpn Circ J 1980; 44:249–263.

- Furushima H, Chinushi M, Sugiura H, Kasai H, Washizuka T, Aizawa Y. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia associated with cardiac sarcoidosis: its mechanisms and outcome. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:217–222.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:1006–1010.

- Reuhl J, Schneider M, Sievert H, Lutz FU, Zieger G. Myocardial sarcoidosis as a rare cause of sudden cardiac death. Forensic Sci Int 1997; 89:145–153.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiramitsu S, et al. Comparison of clinical features and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82:537–540.

- Fleming H. Cardiac sarcoidosis. In:James DG, editor. Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. New York, NY: Dekker 1994; 73:323–334.

- Padilla M. Cardiac sarcoidosis. In:Baughman R, editor. Lung Biology in Health and Disease (Sarcoidosis), vol 210. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group; 2006:515–552.

- Judson MA. A proposed solution to the clinical assessment of sarcoidosis: the sarcoidosis three-dimensional assessment instrument (STAI). Med Hypotheses 2007; 68:1080–1087.

- Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Terrin ML, Yeager H. Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:75–86.

- Hiraga H, Yuwai K, Hiroe M, et al. Guideline for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Study report of diffuse pulmonary diseases. Tokyo, Japan: The Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1993:23–24 (in Japanese).

- Stein E, Jackler I, Stimmel B, Stein W, Siltzbach LE. Asymptomatic electrocardiographic alterations in sarcoidosis. Am Heart J 1973; 86:474–477.

- Fahy GJ, Marwick T, McCreery CJ, Quigley PJ, Maurer BJ. Doppler echocardiographic detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Chest 1996; 109:62–66.

- Butany J, Bahl NE, Morales K, et al. The intricacies of cardiac sarcoidosis: a case report involving the coronary arteries and a review of the literature. Cardiovasc Pathol 2006; 15:222–227.

- Haywood LJ, Sharma OP, Siegel ME, et al. Detection of myocardial sarcoidosis by thallium-201 imaging. J Natl Med Assoc 1982; 74:959–964.

- Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, Kubo S, et al. Effectiveness of delayed enhanced MRI for identification of cardiac sarcoidosis: comparison with radionuclide imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185:110–115.

- Kinney EL, Caldwell JW. Do thallium myocardial perfusion scan abnormalities predict survival in sarcoid patients without cardiac symptoms? Angiology 1990; 41:573–576.

- Pandya C, Brunken RC, Tchou P, Schoenhagen P, Culver DA. Detecting cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis: a call for prospective studies of newer imaging techniques. Eur Respir J 2007; 29:418–422.

- Ohira H, Tsujino I, Ishimaru S, et al. Myocardial imaging with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008; 35:933–941.

- Yamagishi H, Shirai N, Takagi M, et al. Identification of cardiac sarcoidosis with 13N-NH3/18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 2003; 44:1030–1036.

- Takeda N, Yokoyama I, Hiroi Y, et al. Positron emission tomography predicted recovery of complete A-V nodal dysfunction in a patient with cardiac sarcoidosis. Circulation 2002; 105:1144–1145.

- Ishimaru S, Tsujino I, Takei T, et al. Focal uptake on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography images indicates cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J 2005; 26:1538–1543.

- Okumura W, Iwasaki T, Toyama T, et al. Usefulness of fasting 18F-FDG PET in identification of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med 2004; 45:1989–1998.

- Schulz-Menger J, Wassmuth R, Abdel-Aty H, et al. Patterns of myocardial inflammation and scarring in sarcoidosis as assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Heart 2006; 92:399–400.

- Kiuchi S, Teraoka K, Koizumi K, Takazawa K, Yamashina A. Usefulness of late gadolinium enhancement combined with MRI and 67-Ga scintigraphy in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and disease activity evaluation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2007; 23:237–241.

- Matsuki M, Matsuo M. MR findings of myocardial sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol 2000; 55:323–325.

- Inoue S, Shimada T, Murakami Y. Clinical significance of gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced MRI for detection of myocardial lesions in a patient with sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol 1999; 54:70–72.

- Vignaux O, Dhote R, Dudoc D, et al. Detection of myocardial involvement in patients with sarcoidosis applying T2-weighted, contrastenhanced, and cine magnetic resonance imaging: initial results of a prospective study. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2002; 26:762–767.

- Vignaux O. Cardiac sarcoidosis: spectrum of MRI features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184:249–254.

- Smedema JP, Snoep G, Van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1683–1690.

- Doherty MJ, Kumar SK, Nicholson AA, McGivern DV. Cardiac sarcoidosis: the value of magnetic resonance imagine in diagnosis and assessment of response to treatment. Respir Med 1998; 92:697–699.

- Smedema JP, Truter R, de Klerk PA, Zaaiman L, White L, Doubell AF. Cardiac sarcoidosis evaluated with gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance and contrast-enhanced 64-slice computed tomography. Int J Cardiol 2006; 112:261–263.

- Kanao S, Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, et al. Demonstration of cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis by contrast-enhanced multislice computed tomography and delayed-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2005; 29:745–748.

- Vignaux O, Dhote R, Duboc D, et al. Clinical significance of myocardial magnetic resonance abnormalities in patients with sarcoidosis: a 1-year follow-up study. Chest 2002; 122:1895–1901.

- Shimada T, Shimada K, Sakane T, et al. Diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and evaluation of the effects of steroid therapy by gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Med 2001; 110:520–527.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, et al. Prognostic determinants of longterm survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:1006–1010.

- Ishikawa T, Kondoh H, Nakagawa S, Koiwaya Y, Tanaka K. Steroid therapy in cardiac sarcoidosis. Increased left ventricular contractility concomitant with electrocardiographic improvement after prednisolone. Chest 1984; 85:445–447.

- Walsh MJ. Systemic sarcoidosis with refractory ventricular tachycardia and heart failure. Br Heart J 1978; 40:931–933.

- Lash R, Coker J, Wong BY. Treatment of heart block due to sarcoid heart disease. J Electrocardiol 1979; 12:325–329.

- Johns CJ, Schonfeld SA, Scott PP, Zachary JB, MacGregor MI. Longitudinal study of chronic sarcoidosis with low-dose maintenance corticosteroid therapy. Outcome and implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986; 465:702–712.

- Demeter SL. Myocardial sarcoidosis unresponsive to steroids. Treatment with cyclophosphamide. Chest 1988; 94:202–203.

- Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:846–851.

- York EL, Kovithavongs T, Man SF, Rebuck AS, Sproule BJ. Cyclosporine and chronic sarcoidosis. Chest 1990; 98:1026–1029.

- Winters SL, Cohen M, Greenberg S, et al. Sustained ventricular tachycardia associated with sarcoidosis: assessment of the underlying cardiac anatomy and the prospective utility of programmed ventricular stimulation, drug therapy and an implantable antitachycardia device. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18:937–943.

- Bajaj AK, Kopelman HA, Echt DS. Cardiac sarcoidosis with sudden death: treatment with automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Am Heart J 1988; 116:557–560.

- Paz HL, McCormick DJ, Kutalek SP, Patchefsky A. The automated implantable cardiac defibrillator. Prophylaxis in cardiac sarcoidosis. Chest 1994; 106:1603–1607.

- Becker D, Berger E, Chmielewski C. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a report of four cases with ventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1990; 1:214–219.

- Zaidi AR, Zaidi A, Vaitkus PT. Outcome of heart transplantation in patients with sarcoid cardiomyopathy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007; 26:714–717.

- Valantine HA, Tazelaar HD, Macoviak J, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: response to steroids and transplantation. J Heart Transplant 1987; 6:244–250.

- Oni AA, Hershberger RE, Norman DJ, et al. Recurrence of sarcoidosis in a cardiac allograft: control with augmented corticosteroids. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992; 11:367–369.

- Burke WM, Keogh A, Maloney PJ, Delprado W, Bryant DH, Spratt P. Transmission of sarcoidosis via cardiac transplantation. Lancet 1990; 336:1579.

- Johns CJ, Schonfeld SA, Scott PP, Zachary JB, MacGregor MI. Longitudinal study of chronic sarcoidosis with low-dose maintenance corticosteroid therapy. Outcome and complications. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986; 465:702–712.

- Gideon NM, Mannino DM. Sarcoidosis mortality in the United States 1979–1991: an analysis of multiple-cause mortality data. Am J Med 1996; 100:423–427.

- Fleming HA, Bailey SM. The prognosis of sarcoid heart disease in the United Kingdom. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1986; 465:543–550.

- Takada K, Ina Y, Yamamoto M, Satoh T, Morishita M. Prognosis after pacemaker implantation in cardiac sarcoidosis in Japan. Clinical evaluation of corticosteroid therapy. Sarcoidosis 1994; 11:113–117.

- Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:1683–1690.

- Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:736–755.

- Rybicki BA, Major M, Popovich J, Maliarik MJ, Iannuzzi MC. Racial differences in sarcoidosis incidence: a 5-year study in a health maintenance organization. Am J Epidemiol 1997; 145:234–241.

- Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, et al. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1976; 278:455–469.

- Chapelon-Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:315–334.

- Iwai K, Sekiguti M, Hosoda Y, et al. Racial difference in cardiac sarcoidosis incidence observed at autopsy. Sarcoidosis 1994; 11:26–31.

- Thomsen TK, Eriksson T. Myocardial sarcoidosis in forensic medicine. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 1999; 20:52–56.

- Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Buckley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation 1978; 58:1204–1211.

- Roberts WC, McAllister HA, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med 1977; 63:86–108.

- Bargout R, Kelly R. Sarcoid heart disease: clinical course and treatment. Int J Cardiol 2004; 97:173–182.

- Abeler V. Sarcoidosis of the cardiac conducting system. Am Heart J 1979; 97:701–707.

- Fleming HA, Bailey SM. Sarcoid heart disease. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1981; 15:245–253.

- Sekiguchi M, Numao Y, Imai M, Furuie T, Mikami R. Clinical and histological profile of sarcoidosis of the heart and acute idiopathic myocarditis. Concepts through a study employing endomyocardial biopsy. I. Sarcoidosis. Jpn Circ J 1980; 44:249–263.

- Furushima H, Chinushi M, Sugiura H, Kasai H, Washizuka T, Aizawa Y. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia associated with cardiac sarcoidosis: its mechanisms and outcome. Clin Cardiol 2004; 27:217–222.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiroe M, et al. Prognostic determinants of long-term survival in Japanese patients with cardiac sarcoidosis treated with prednisone. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:1006–1010.

- Reuhl J, Schneider M, Sievert H, Lutz FU, Zieger G. Myocardial sarcoidosis as a rare cause of sudden cardiac death. Forensic Sci Int 1997; 89:145–153.

- Yazaki Y, Isobe M, Hiramitsu S, et al. Comparison of clinical features and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82:537–540.

- Fleming H. Cardiac sarcoidosis. In:James DG, editor. Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. New York, NY: Dekker 1994; 73:323–334.

- Padilla M. Cardiac sarcoidosis. In:Baughman R, editor. Lung Biology in Health and Disease (Sarcoidosis), vol 210. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group; 2006:515–552.

- Judson MA. A proposed solution to the clinical assessment of sarcoidosis: the sarcoidosis three-dimensional assessment instrument (STAI). Med Hypotheses 2007; 68:1080–1087.

- Judson MA, Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Terrin ML, Yeager H. Defining organ involvement in sarcoidosis: the ACCESS proposed instrument. ACCESS Research Group. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16:75–86.