User login

Ectatic Vessels on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

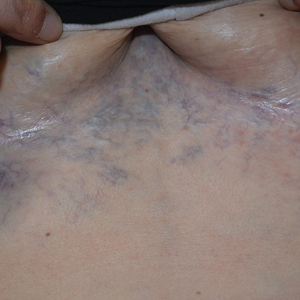

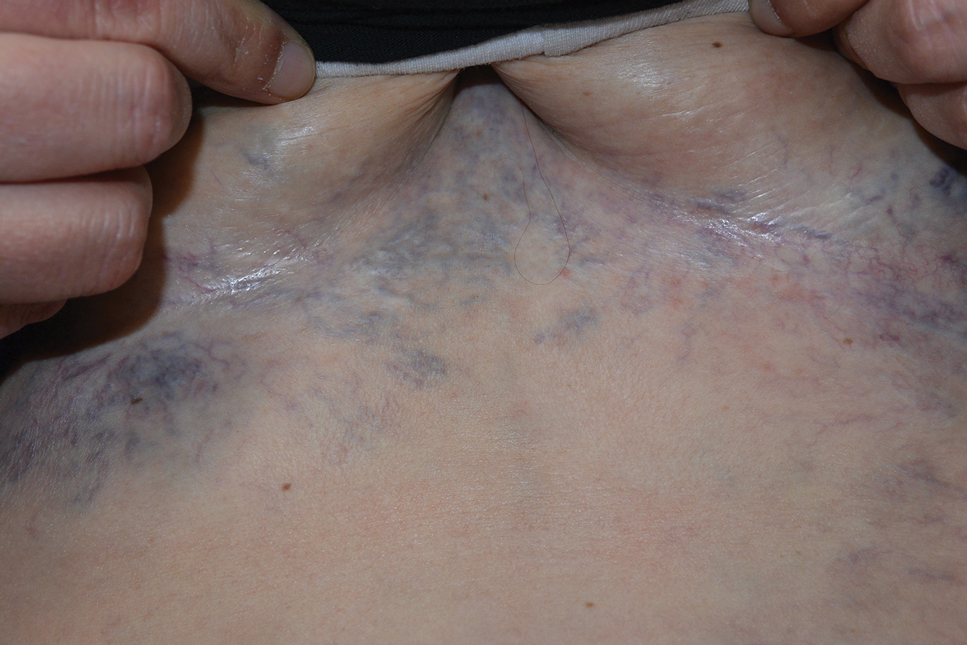

Computed tomography angiography of the chest confirmed a diagnosis of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome due to external pressure of the indwelling catheter. Upon diagnosis, the left indwelling catheter was removed. Further testing to assess for a potential pulmonary embolism was negative. Resolution of the ectatic spider veins and patientreported intermittent facial swelling was achieved after catheter removal.

Superior vena cava syndrome occurs when the SVC is occluded due to extrinsic pressure or thrombosis. Although classically thought to be due to underlying bronchogenic carcinomas, all pathologies that cause compression of the SVC also can lead to vessel occlusion.1 Superior vena cava syndrome initially can be detected on physical examination. The most prominent skin finding includes diffusely dilated blood vessels on the central chest wall, which indicate the presence of collateral blood vessels.1 Imaging studies such as abdominal computed tomography can provide information on the etiology of the condition but are not required for diagnosis. Given the high correlation of SVC syndrome with underlying lung and mediastinal carcinomas, imaging was warranted in our patient. Imaging also can distinguish if the condition is due to external pressure or thrombosis.2 For SVC syndrome due to thrombosis, endovascular therapy is first-line management; however, mechanical thrombectomy may be preferred in patients with absolute contraindication to thrombolytic agents.3 In the setting of increased external pressure on the SVC, treatment includes the removal of the source of pressure.4

In a case series including 78 patients, ports and indwelling catheters accounted for 71% of benign SVC cases.5 Our patient’s SVC syndrome most likely was due to the indwelling catheter pressing on the SVC. The goal of treatment is to address the underlying cause—whether it be pressure or thrombosis. In the setting of increased external pressure, treatment includes removal of the source of pressure from the SVC.4

Other differential diagnoses to consider for newonset ectatic vessels on the chest wall include generalized essential telangiectasia, scleroderma, poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, and caput medusae. Generalized essential telangiectasia is characterized by red or pink dilated capillary blood vessels in a branch or lacelike pattern predominantly on the lower limbs. The eruption primarily is asymptomatic, though tingling or numbness may be reported.6 The diagnosis can be made with a punch biopsy, with histopathology showing dilated vessels in the dermis.7

Scleroderma is a connective tissue fibrosis disorder with variable clinical presentations. The systemic sclerosis subset can be divided into localized systemic sclerosis and diffuse systemic sclerosis. Physical examination reveals cutaneous sclerosis in various areas of the body. Localized systemic sclerosis includes sclerosis of the fingers and face, while diffuse systemic sclerosis is notable for progression to the arms, legs, and trunk.8 In addition to sclerosis, diffuse telangiectases also can be observed. Systemic sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and laboratory studies to identify antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is a variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The initial presentation is characterized by plaques of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with atrophy and telangiectases. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and classically involve the trunk and flexural areas.9 The diagnosis is made with skin biopsy and immunohistochemical studies, with findings reflective of mycosis fungoides.

Caput medusae (palm tree sign) is a cardinal feature of portal hypertension characterized by grossly dilated and engorged periumbilical veins. To shunt blood from the portal venous system, cutaneous collateral veins between the umbilical veins and abdominal wall veins are used, resulting in the appearance of engorged veins in the anterior abdominal wall.10 The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography showing the direction of blood flow through abdominal vessels.

- Drouin L, Pistorius MA, Lafforgue A, et al. Upper-extremity venous thrombosis: a retrospective study about 160 cases [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2019;40:9-15.

- Richie E. Clinical pearl: diagnosing superior vena cava syndrome. Emergency Medicine News. 2017;39:22. doi:10.1097/01 .EEM.0000522220.37441.d2

- Azizi A, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2896-2910. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.038

- Dumantepe M, Tarhan A, Ozler A. Successful treatment of central venous catheter induced superior vena cava syndrome with ultrasound accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E269-E273.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37-42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0

- Long D, Marshman G. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:67-69. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00033.x

- Braverman IM. Ultrastructure and organization of the cutaneous microvasculature in normal and pathologic states. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(2 suppl):2S-9S.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336. doi:10.1007 /s12016-017-8625-4

- Bloom B, Marchbein S, Fischer M, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:494. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159322

The Diagnosis: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Computed tomography angiography of the chest confirmed a diagnosis of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome due to external pressure of the indwelling catheter. Upon diagnosis, the left indwelling catheter was removed. Further testing to assess for a potential pulmonary embolism was negative. Resolution of the ectatic spider veins and patientreported intermittent facial swelling was achieved after catheter removal.

Superior vena cava syndrome occurs when the SVC is occluded due to extrinsic pressure or thrombosis. Although classically thought to be due to underlying bronchogenic carcinomas, all pathologies that cause compression of the SVC also can lead to vessel occlusion.1 Superior vena cava syndrome initially can be detected on physical examination. The most prominent skin finding includes diffusely dilated blood vessels on the central chest wall, which indicate the presence of collateral blood vessels.1 Imaging studies such as abdominal computed tomography can provide information on the etiology of the condition but are not required for diagnosis. Given the high correlation of SVC syndrome with underlying lung and mediastinal carcinomas, imaging was warranted in our patient. Imaging also can distinguish if the condition is due to external pressure or thrombosis.2 For SVC syndrome due to thrombosis, endovascular therapy is first-line management; however, mechanical thrombectomy may be preferred in patients with absolute contraindication to thrombolytic agents.3 In the setting of increased external pressure on the SVC, treatment includes the removal of the source of pressure.4

In a case series including 78 patients, ports and indwelling catheters accounted for 71% of benign SVC cases.5 Our patient’s SVC syndrome most likely was due to the indwelling catheter pressing on the SVC. The goal of treatment is to address the underlying cause—whether it be pressure or thrombosis. In the setting of increased external pressure, treatment includes removal of the source of pressure from the SVC.4

Other differential diagnoses to consider for newonset ectatic vessels on the chest wall include generalized essential telangiectasia, scleroderma, poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, and caput medusae. Generalized essential telangiectasia is characterized by red or pink dilated capillary blood vessels in a branch or lacelike pattern predominantly on the lower limbs. The eruption primarily is asymptomatic, though tingling or numbness may be reported.6 The diagnosis can be made with a punch biopsy, with histopathology showing dilated vessels in the dermis.7

Scleroderma is a connective tissue fibrosis disorder with variable clinical presentations. The systemic sclerosis subset can be divided into localized systemic sclerosis and diffuse systemic sclerosis. Physical examination reveals cutaneous sclerosis in various areas of the body. Localized systemic sclerosis includes sclerosis of the fingers and face, while diffuse systemic sclerosis is notable for progression to the arms, legs, and trunk.8 In addition to sclerosis, diffuse telangiectases also can be observed. Systemic sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and laboratory studies to identify antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is a variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The initial presentation is characterized by plaques of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with atrophy and telangiectases. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and classically involve the trunk and flexural areas.9 The diagnosis is made with skin biopsy and immunohistochemical studies, with findings reflective of mycosis fungoides.

Caput medusae (palm tree sign) is a cardinal feature of portal hypertension characterized by grossly dilated and engorged periumbilical veins. To shunt blood from the portal venous system, cutaneous collateral veins between the umbilical veins and abdominal wall veins are used, resulting in the appearance of engorged veins in the anterior abdominal wall.10 The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography showing the direction of blood flow through abdominal vessels.

The Diagnosis: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Computed tomography angiography of the chest confirmed a diagnosis of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome due to external pressure of the indwelling catheter. Upon diagnosis, the left indwelling catheter was removed. Further testing to assess for a potential pulmonary embolism was negative. Resolution of the ectatic spider veins and patientreported intermittent facial swelling was achieved after catheter removal.

Superior vena cava syndrome occurs when the SVC is occluded due to extrinsic pressure or thrombosis. Although classically thought to be due to underlying bronchogenic carcinomas, all pathologies that cause compression of the SVC also can lead to vessel occlusion.1 Superior vena cava syndrome initially can be detected on physical examination. The most prominent skin finding includes diffusely dilated blood vessels on the central chest wall, which indicate the presence of collateral blood vessels.1 Imaging studies such as abdominal computed tomography can provide information on the etiology of the condition but are not required for diagnosis. Given the high correlation of SVC syndrome with underlying lung and mediastinal carcinomas, imaging was warranted in our patient. Imaging also can distinguish if the condition is due to external pressure or thrombosis.2 For SVC syndrome due to thrombosis, endovascular therapy is first-line management; however, mechanical thrombectomy may be preferred in patients with absolute contraindication to thrombolytic agents.3 In the setting of increased external pressure on the SVC, treatment includes the removal of the source of pressure.4

In a case series including 78 patients, ports and indwelling catheters accounted for 71% of benign SVC cases.5 Our patient’s SVC syndrome most likely was due to the indwelling catheter pressing on the SVC. The goal of treatment is to address the underlying cause—whether it be pressure or thrombosis. In the setting of increased external pressure, treatment includes removal of the source of pressure from the SVC.4

Other differential diagnoses to consider for newonset ectatic vessels on the chest wall include generalized essential telangiectasia, scleroderma, poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, and caput medusae. Generalized essential telangiectasia is characterized by red or pink dilated capillary blood vessels in a branch or lacelike pattern predominantly on the lower limbs. The eruption primarily is asymptomatic, though tingling or numbness may be reported.6 The diagnosis can be made with a punch biopsy, with histopathology showing dilated vessels in the dermis.7

Scleroderma is a connective tissue fibrosis disorder with variable clinical presentations. The systemic sclerosis subset can be divided into localized systemic sclerosis and diffuse systemic sclerosis. Physical examination reveals cutaneous sclerosis in various areas of the body. Localized systemic sclerosis includes sclerosis of the fingers and face, while diffuse systemic sclerosis is notable for progression to the arms, legs, and trunk.8 In addition to sclerosis, diffuse telangiectases also can be observed. Systemic sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and laboratory studies to identify antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is a variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The initial presentation is characterized by plaques of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with atrophy and telangiectases. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and classically involve the trunk and flexural areas.9 The diagnosis is made with skin biopsy and immunohistochemical studies, with findings reflective of mycosis fungoides.

Caput medusae (palm tree sign) is a cardinal feature of portal hypertension characterized by grossly dilated and engorged periumbilical veins. To shunt blood from the portal venous system, cutaneous collateral veins between the umbilical veins and abdominal wall veins are used, resulting in the appearance of engorged veins in the anterior abdominal wall.10 The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography showing the direction of blood flow through abdominal vessels.

- Drouin L, Pistorius MA, Lafforgue A, et al. Upper-extremity venous thrombosis: a retrospective study about 160 cases [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2019;40:9-15.

- Richie E. Clinical pearl: diagnosing superior vena cava syndrome. Emergency Medicine News. 2017;39:22. doi:10.1097/01 .EEM.0000522220.37441.d2

- Azizi A, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2896-2910. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.038

- Dumantepe M, Tarhan A, Ozler A. Successful treatment of central venous catheter induced superior vena cava syndrome with ultrasound accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E269-E273.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37-42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0

- Long D, Marshman G. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:67-69. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00033.x

- Braverman IM. Ultrastructure and organization of the cutaneous microvasculature in normal and pathologic states. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(2 suppl):2S-9S.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336. doi:10.1007 /s12016-017-8625-4

- Bloom B, Marchbein S, Fischer M, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:494. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159322

- Drouin L, Pistorius MA, Lafforgue A, et al. Upper-extremity venous thrombosis: a retrospective study about 160 cases [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2019;40:9-15.

- Richie E. Clinical pearl: diagnosing superior vena cava syndrome. Emergency Medicine News. 2017;39:22. doi:10.1097/01 .EEM.0000522220.37441.d2

- Azizi A, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2896-2910. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.038

- Dumantepe M, Tarhan A, Ozler A. Successful treatment of central venous catheter induced superior vena cava syndrome with ultrasound accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E269-E273.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37-42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0

- Long D, Marshman G. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:67-69. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00033.x

- Braverman IM. Ultrastructure and organization of the cutaneous microvasculature in normal and pathologic states. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(2 suppl):2S-9S.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336. doi:10.1007 /s12016-017-8625-4

- Bloom B, Marchbein S, Fischer M, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:494. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159322

A 32-year-old woman presented to vascular surgery for evaluation of spider veins of 2 years’ duration that originated on the breasts but later spread to include the central chest, inframammary folds, and back. She reported associated pain and discomfort as well as intermittent facial swelling and tachycardia but denied pruritus and bleeding. The patient had a history of a kidney transplant 6 months prior, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and Sjögren syndrome with a left indwelling catheter. Her current medications included systemic immunosuppressive agents. Physical examination revealed blue-purple ectatic vessels on the inframammary folds and central chest extending to the back. Erythema on the face, neck, and arms was not appreciated. No palpable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary lymph nodes were noted.

Chronic Ulcerative Lesion

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

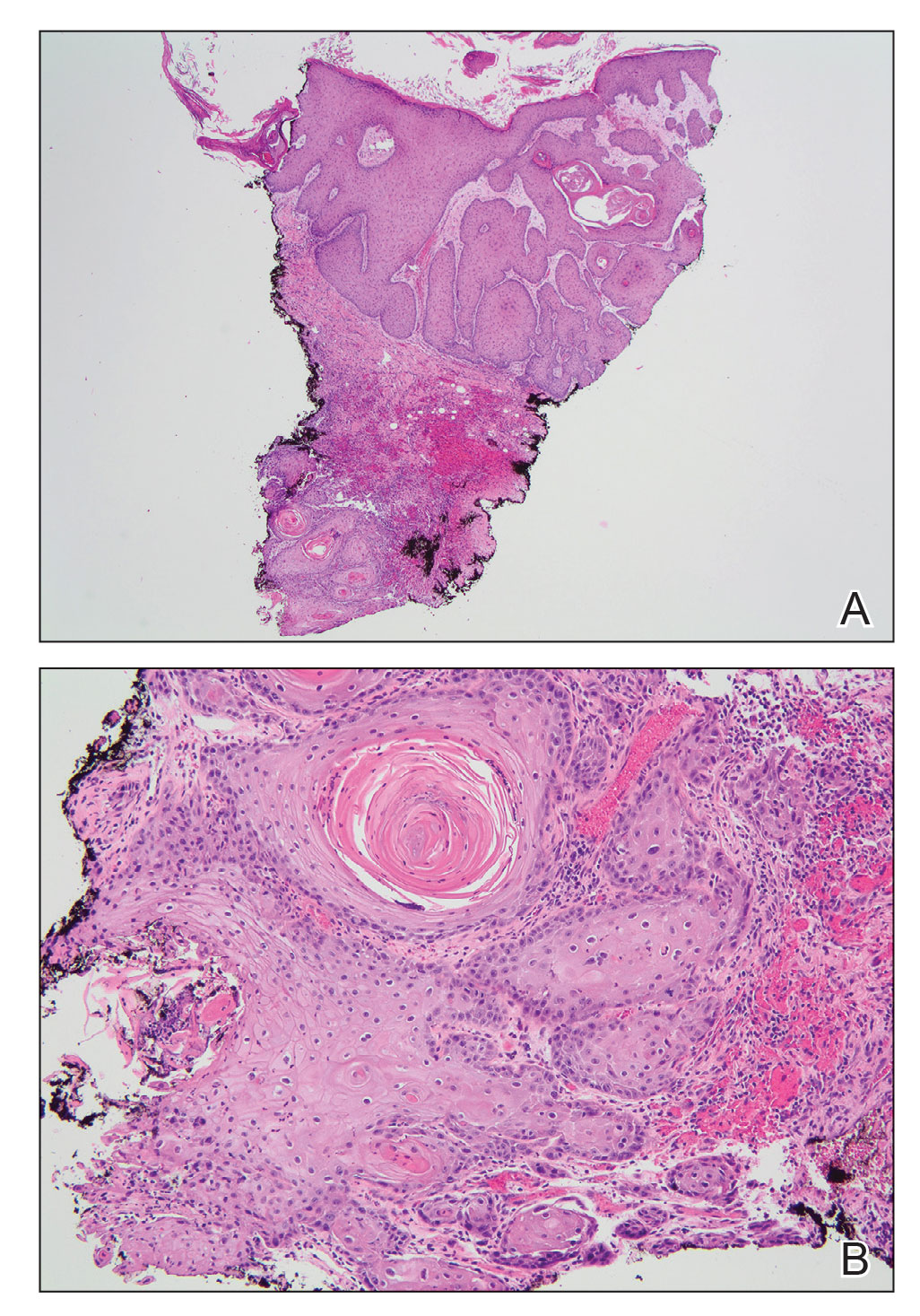

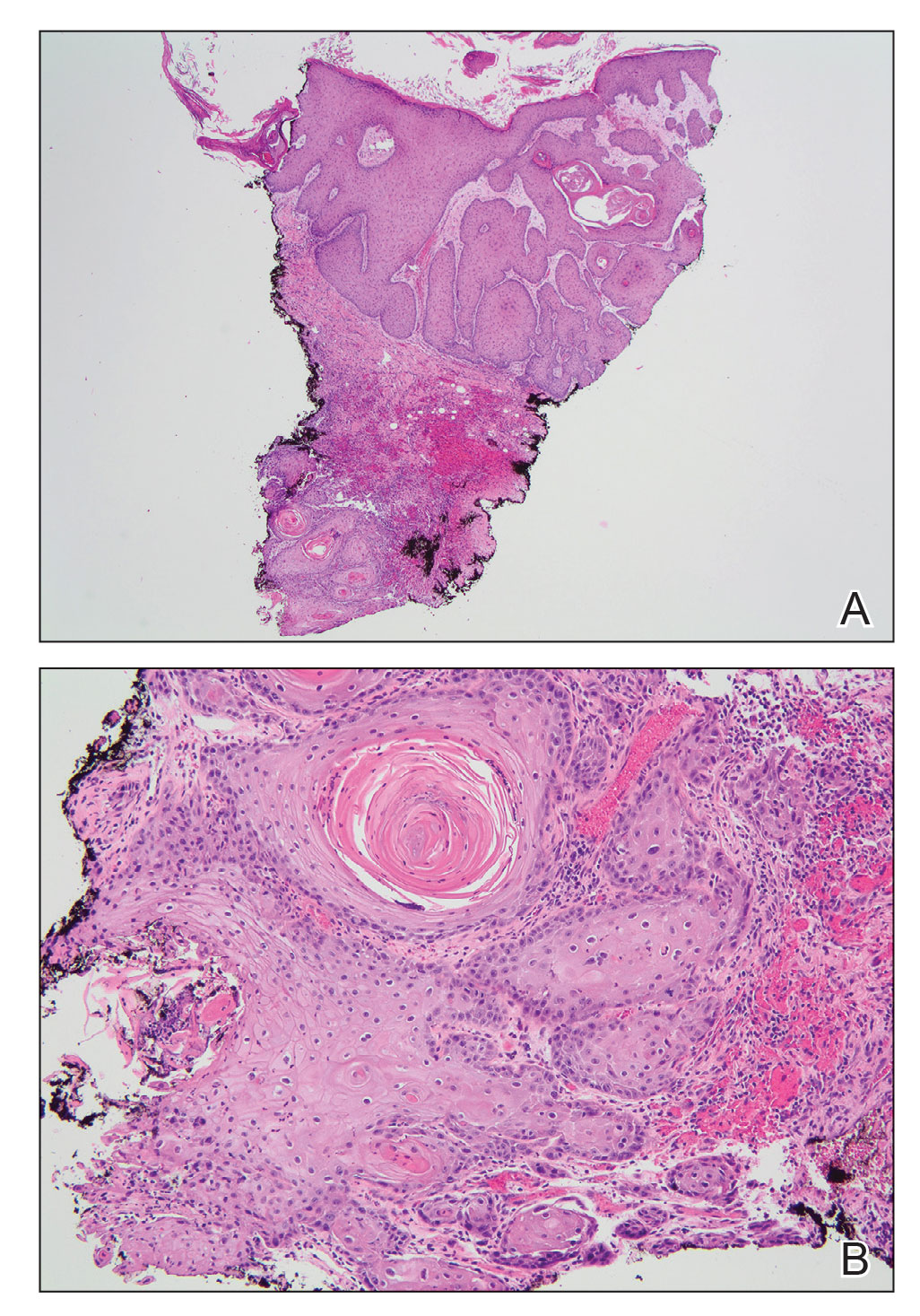

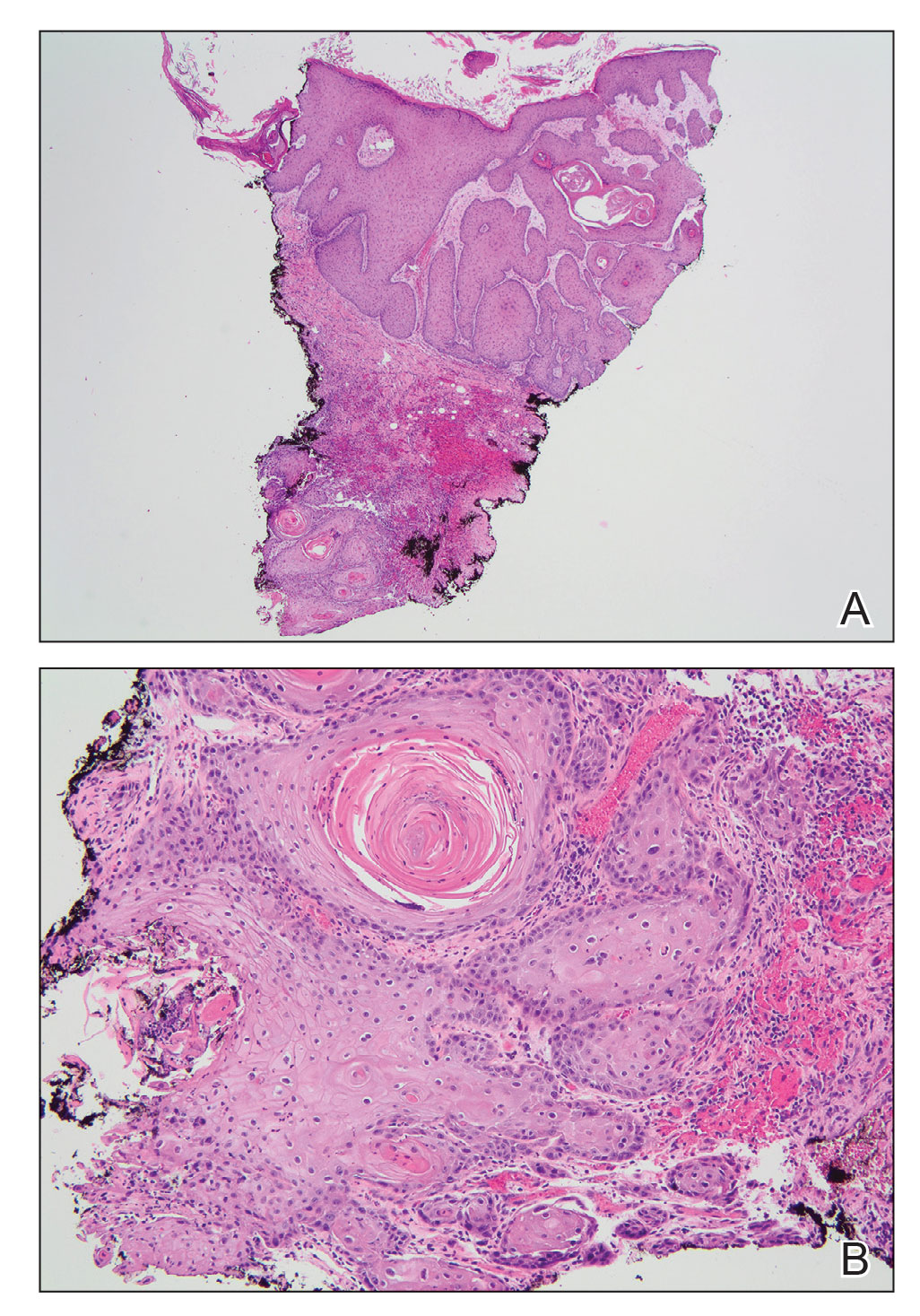

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

The Diagnosis: Marjolin Ulcer

A skin biopsy during his prior hospital admission demonstrated an ulcer with granulation tissue and mixed inflammation, and the patient was discharged with close outpatient follow-up. Two repeat skin biopsies from the peripheral margin at the time of the outpatient follow-up confirmed an invasive, well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Figure), consistent with a Marjolin ulcer. Radiography demonstrated multiple left iliac chain and inguinal lymphadenopathies with extensive subcutaneous disease overlying the left medial tibia. After tumor board discussion, surgery was not recommended due to the size and likely penetration into the muscle. The patient began treatment with cemiplimab-rwlc, a PD-1 inhibitor. Within 4 cycles of treatment, he had improved pain and ambulation, and a 3-month follow-up positron emission tomography scan revealed decreased lymph node and cutaneous metabolic activity as well as clinical improvement.

Marjolin ulcers are rare and aggressive squamous cell carcinomas that arise from chronic wounds such as burn scars or pressure ulcers.1 Although an underlying well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma is the most common etiology, patients also may present with underlying basal cell carcinomas, melanomas, or angiosarcomas.2 The exact pathogenesis underlying the malignant degeneration is unclear but appears to be driven by chronic inflammation. Patients classically present with a nonhealing ulcer associated with raised, friable, or crusty borders, as well as surrounding scar tissue. There is a median latency of 30 years after the trauma, though acute transformation within 12 months of an injury is possible.3 The diagnosis is confirmed with a peripheral wound biopsy. Surgical excision with wide margins remains the most common and effective intervention, especially for localized disease.1 The addition of lymph node dissection remains controversial, but treatment decisions can be guided by radiographic staging.4

The prognosis of Marjolin ulcers remains poor, with a predicted 5-year survival rate ranging from 43% to 58%.1 Dermatologists and trainees should be aware of Marjolin ulcers, especially as a mimicker of other chronic ulcerating conditions. Among the differential diagnosis, ulcerative lichen planus is a condition that commonly affects the oral and genital regions; however, patients with erosive lichen planus may develop an increased risk for the subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in the region.5 Furthermore, arterial ulcers typically develop on the distal lower extremities with other signs of chronic ischemia, including absent peripheral pulses, atrophic skin, hair loss, and ankle-brachial indices less than 0.5. Conversely, a venous ulcer classically affects the medial malleolus and will have evidence of venous insufficiency, including stasis dermatitis and peripheral edema.6

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

- Iqbal FM, Sinha Y, Jaffe W. Marjolin’s ulcer: a rare entity with a call for early diagnosis [published online July 15, 2015]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208176

- Kanth AM, Heiman AJ, Nair L, et al. Current trends in management of Marjolin’s ulcer: a systematic review. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42:144-151. doi:10.1093/jbcr/iraa128

- Copcu E. Marjolin’s ulcer: a preventable complication of burns? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:E156-E164. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8082e

- Pekarek B, Buck S, Osher L. A comprehensive review on Marjolin’s ulcers: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Certif Wound Spec. 2011; 3:60-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcws.2012.04.001

- Tziotzios C, Lee JYW, Brier T, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:789-804.

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1242204

A 46-year-old man with a history of a left leg burn during childhood that was unsuccessfully treated with multiple skin grafts presented as a hospital follow-up for outpatient management of an ulcer. The patient had an ulcer that gradually increased in size over 7 years. Over the course of 2 weeks prior to the hospital presentation, he noted increased pain and severe difficulty with ambulation but remained afebrile without other systemic symptoms. Prior to the outpatient follow-up, he had been admitted to the hospital where he underwent imaging, laboratory studies, and skin biopsy, as well as treatment with empiric vancomycin. Physical examination revealed a large undermined ulcer with an elevated peripheral margin and crusting on the left lower leg with surrounding chronic scarring.