User login

When the dissociation curve shifts to the left

A 48-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after 2 days of nonproductive cough, chest discomfort, worsening shortness of breath, and subjective fever. She had a history of systemic sclerosis. She was currently taking prednisone 20 mg daily and aspirin 81 mg daily.

Physical examination revealed tachypnea (28 breaths per minute), and bronchial breath sounds in the left lower chest posteriorly.

The initial laboratory workup revealed:

- Hemoglobin 106 g/L (reference range 115–155)

- Mean corpuscular volume 84 fL (80–100)

- White blood cell count 29.4 × 109/L (3.70–11.0), with 85% neutrophils

- Platelet count 180 × 109/L (150–350)

- Lactate dehydrogenase 312 U/L (100–220).

Chest radiography showed opacification of the lower lobe of the left lung.

She was admitted to the hospital and started treatment with intravenous azithromycin and ceftriaxone for presumed community-acquired pneumonia, based on the clinical presentation and findings on chest radiography. Because of her immunosuppression (due to chronic prednisone therapy) and her high lactate dehydrogenase level, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia was suspected, and because she had a history of allergy to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and pentamidine, she was started on dapsone.

During the next 24 hours, she developed worsening dyspnea, hypoxia, and cyanosis. She was placed on an air-entrainment mask, with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.5. Pulse oximetry showed an oxygen saturation of 85%, but arterial blood gas analysis indicated an oxyhemoglobin concentration of 95%.

THE ‘SATURATION GAP’

1. Which is most likely to have caused the discrepancy between the oxyhemoglobin concentration and the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry in this patient?

- Methemoglobinemia

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Inappropriate placement of the pulse oximeter probe

- Pulmonary embolism

Methemoglobinemia is the most likely cause of the discrepancy between the oxyhemoglobin levels and the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, a phenomenon also known as the “saturation gap.” Other common causes are cyanide poisoning and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Carbon monoxide poisoning, however, does not explain our patient’s cyanosis. On the contrary, carbon monoxide poisoning can actually cause the patient’s lips and mucous membranes to appear unnaturally bright pink. Also, carbon monoxide poisoning raises the blood concentration of carboxyhemoglobin (which has a high affinity for oxygen), and this usually causes pulse oximetry to read inappropriately high, whereas in our patient it read low.

Incorrect placement of the pulse oximeter probe can result in an inaccurate measurement of oxygen saturation. Visualization of the waveform on the plethysmograph or the signal quality index can be used to assess adequate placement of the pulse oximeter probe. However, inadequate probe placement does not explain our patient’s dyspnea and cyanosis.

Pulmonary embolism can lead to hypoxia as a result of ventilation-perfusion mismatch. However, pulmonary embolism leading to low oxygen saturation on pulse oximetry will also lead to concomitantly low oxyhemoglobin levels as measured by arterial blood gas analysis, and this was not seen in our patient.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

Because there was a discrepancy between our patient’s pulse oximetry reading and oxyhemoglobin concentration by arterial blood gas measurement, her methemoglobin level was checked and was found to be 30%, thus confirming the diagnosis of methemoglobinemia.

WHAT IS METHEMOGLOBINEMIA, AND WHAT CAUSES IT?

Oxygen is normally bound to iron in its ferrous (Fe2+) form in hemoglobin to form oxyhemoglobin. Oxidative stress in the body can cause iron to change from the ferrous to the ferric (Fe3+) state, forming methemoglobin. Methemoglobin is normally present in the blood in low levels (< 1% of the total hemoglobin), and ferric iron is reduced and recycled back to the ferrous form by NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase, an enzyme present in red blood cells. This protective mechanism maintains methemoglobin levels within safe limits. But increased production can lead to accumulation of methemoglobin, resulting in dyspnea and hypoxia and the condition referred to as methemoglobinemia.1

Increased levels of methemoglobin relative to normal hemoglobin cause tissue hypoxia by several mechanisms. Methemoglobin cannot efficiently carry oxygen; instead, it binds to water or to a hydroxide ion depending on the pH of the environment.2 Therefore, the hemoglobin molecule does not carry its usual load of oxygen, and hypoxia results from the reduced delivery of oxygen to tissues. In addition, an increased concentration of methemoglobin causes a leftward shift in the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve, representing an increased affinity to bound oxygen in the remaining heme groups. The tightly bound oxygen is not adequately released at the tissue level, thus causing cellular hypoxia.

Methemoglobinemia is most often caused by exposure to an oxidizing chemical or drug that increases production of methemoglobin. In rare cases, it is caused by a congenital deficiency of NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase.3

2. Which of the following drugs can cause methemoglobinemia?

- Acetaminophen

- Dapsone

- Benzocaine

- Primaquine

All four of these drugs are common culprits for causing acquired methemoglobinemia; others include chloroquine, nitroglycerin, and sulfonamides.4–6

The increased production of methemoglobin caused by these drugs overwhelms the protective effect of reducing enzymes and can lead to an accumulation of methemoglobin. However, because of variability in cellular metabolism, not every person who takes these drugs develops dangerous levels of methemoglobin.

Dapsone and benzocaine are the most commonly encountered drugs known to cause methemoglobinemia (Table 1). Dapsone is an anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial agent most commonly used for treating lepromatous leprosy and dermatitis herpetiformis. It is also often prescribed for prophylaxis and treatment of P jirovecii pneumonia in immunosuppressed individuals.7 Benzocaine is a local anesthetic and was commonly used before procedures such as oral or dental surgery, transesophageal echocardiography, and endoscopy.8–10 Even low doses of benzocaine can lead to high levels of methemoglobinemia. However, the availability of other, safer anesthetics now limits the use of benzocaine in major US centers. In addition, the topical anesthetic Emla (lidocaine plus prilocaine) has been recently reported as a cause of methemoglobinemia in infants and children.11,12

Also, potentially fatal methemoglobinemia has been reported in patients with a deficiency of G-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) who received rasburicase, a recombinant version of urate oxidase enzyme used to prevent and treat tumor lysis syndrome.13,14

Lastly, methemoglobinemia has been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with mesalamine.

Although this adverse reaction is rare, clinicians should be aware of it, since these agents are commonly used in everyday medical practice.15

RECOGNIZING THE DANGER SIGNS

The clinical manifestations of methemoglobinemia are directly proportional to the percentage of methemoglobin in red blood cells. Cyanosis generally becomes apparent at concentrations around 15%, at which point the patient may still have no symptoms. Anxiety, lightheadedness, tachycardia, and dizziness manifest at levels of 20% to 30%. Fatigue, confusion, dizziness, tachypnea, and worsening tachycardia occur at levels of 30% to 50%. Levels of 50% to 70% cause coma, seizures, arrhythmias, and acidosis, and levels over 70% are considered lethal.16

While these levels provide a general guideline of symptomatology in an otherwise healthy person, it is important to remember that patients with underlying conditions such as anemia, lung disease (both of which our patient had), sepsis, thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, and sickle cell disease can manifest symptoms at lower concentrations of methemoglobin.1,17

Most patients who develop clinically significant levels of methemoglobin do so within the first few hours of starting one of the culprit drugs.

DIAGNOSIS: METHEMOGLOBINEMIA AND THE SATURATION GAP

In patients with methemoglobinemia, pulse oximetry gives lower values than arterial blood gas oxygen measurements. Regular pulse oximetry works by measuring light absorbance at two distinct wavelengths (660 and 940 nm) to calculate the ratio of oxyhemoglobin to deoxyhemoglobin. Methemoglobin absorbs light at both these wavelengths, thus lowering the pulse oximetry values.1

In contrast, oxygen saturation of arterial blood gas (oxyhemoglobin) is calculated indirectly from the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the blood and does not include oxygen bound to hemoglobin. Therefore, the measured arterial oxygen saturation is often normal in patients with methemoglobinemia since it relies only on inspired oxygen content and is independent of the methemoglobin concentration.18

Oxygen supplementation can raise the level of oxyhemoglobin, which is a measure of dissolved oxygen, but the oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry remains largely unchanged—ie, the saturation gap. A difference of more than 5% between the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry and blood gas analysis is abnormal. Patients with clinically significant methemoglobinemia usually have a saturation gap greater than 10%.

Several other unique features should raise suspicion of methemoglobinemia. It should be considered in a patient presenting with cyanosis out of proportion to the oxygen saturation and in a patient with low oxygen saturation and a normal chest radiograph. Other clues include blood that is chocolate-colored on gross examination, rather than the dark red of deoxygenated blood.

Co-oximetry measures oxygen saturation using different wavelengths of light to distinguish between fractions of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin, but it is not widely available.

THE NEXT STEP

3. What is the next step in the management of our patient?

- Discontinue the dapsone

- Start methylene blue

- Start hyperbaric oxygen

- Give sodium thiosulfate

- Discontinue dapsone and start methylene blue

The next step in her management should be to stop the dapsone and start an infusion of methylene blue. Hyperbaric oxygen is used in treating carbon monoxide poisoning, and sodium thiosulfate is used in treating cyanide toxicity. They would not be appropriate in this patient’s care.

MANAGEMENT OF ACQUIRED METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

The first, most critical step in managing acquired methemoglobinemia is to immediately discontinue the suspected offending agent. In most patients without a concomitant condition such as anemia or lung disease and with a methemoglobin level below 20%, discontinuing the offending agent may suffice. Patients with a level of 20% or greater and patients with cardiac and pulmonary disease, who develop symptoms at lower concentrations of methemoglobin, require infusion of methylene blue.

Methylene blue is converted to its reduced form, leukomethylene blue, by NADPH-methemoglobin reductase. As it is oxidized, leukomethylene blue reduces methemoglobin to hemoglobin. A dose of 1 mg/kg intravenously is given at first. The response is usually dramatic, with a reduction in methemoglobin levels and improvement in symptoms often within 30 to 60 minutes. If levels remain high, the dose can be repeated 1 hour later.19

A caveat: methylene blue therapy should be avoided in patients with complete G6PD deficiency. Methylene blue works through the enzyme NADPH-methemoglobin reductase, and since patients with G6PD deficiency lack this enzyme, methylene blue is ineffective. In fact, since it cannot be reduced, excessive methylene blue can oxidize hemoglobin to methemoglobin, further exacerbating the condition. In patients with partial G6PD deficiency, methylene blue is still recommended as a first-line treatment, but at a lower initial dose (0.3–0.5 mg/kg). However, in patients with significant hemolysis, an exchange transfusion is the only treatment option.

CASE CONCLUDED

Since dapsone was identified as the likely cause of methemoglobinemia in our patient, it was immediately discontinued. Because she was symptomatic, 70 mg of methylene blue was given intravenously. Over the next 60 minutes, her clinical condition improved significantly. A repeat methemoglobin measurement was 3%.

She was discharged home the next day on oral antibiotics to complete treatment for community-acquired pneumonia.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Consider methemoglobinemia in a patient with unexplained cyanosis.

- Pulse oximetry gives lower values than arterial blood gas oxygen measurements in patients with methemoglobinemia, and pulse oximetry readings do not improve with supplemental oxygen.

- A saturation gap greater than 5% strongly suggests methemoglobinemia.

- The diagnosis of methemoglobinemia is confirmed by measuring the methemoglobin concentration.

- Most healthy patients develop symptoms at methemoglobin levels of 20%, but patients with comorbidities can develop symptoms at lower levels.

- A number of drugs can cause methemoglobinemia, even at therapeutic dosages.

- Treatment is generally indicated in patients who have symptoms or in healthy patients who have a methemoglobin level of 20% or greater.

- Identifying and promptly discontinuing the causative agent and initiating methylene blue infusion (1 mg/kg over 5 minutes) is the preferred treatment.

- Cortazzo JA, Lichtman AD. Methemoglobinemia: a review and recommendations for management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014; 28:1055–1059.

- Margulies DR, Manookian CM. Methemoglobinemia as a cause of respiratory failure. J Trauma 2002; 52:796–797.

- Skold A, Cosco DL, Klein R. Methemoglobinemia: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. South Med J 2011; 104:757–761.

- Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:265–273.

- Kanji HD, Mithani S, Boucher P, Dias VC, Yarema MC. Coma, metabolic acidosis, and methemoglobinemia in a patient with acetaminophen toxicity. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2013; 20:e207–e211.

- Kawasumi H, Tanaka E, Hoshi D, Kawaguchi Y, Yamanaka H. Methemoglobinemia induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Intern Med 2013; 52:1741–1743.

- Wieringa A, Bethlehem C, Hoogendoorn M, van der Maten J, van Roon EN. Very late recovery of dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014; 52:80–81.

- Barclay JA, Ziemba SE, Ibrahim RB. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia: a primer for clinicians. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:1103–1115.

- Taleb M, Ashraf Z, Valavoor S, Tinkel J. Evaluation and management of acquired methemoglobinemia associated with topical benzocaine use. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2013; 13:325–330.

- Chowdhary S, Bukoye B, Bhansali AM, et al. Risk of topical anesthetic-induced methemoglobinemia: a 10-year retrospective case-control study. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:771–776.

- Larson A, Stidham T, Banerji S, Kaufman J. Seizures and methemoglobinemia in an infant after excessive EMLA application. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013; 29:377–379.

- Schmitt C, Matulic M, Kervégant M, et al. Methaemoglobinaemia in a child treated with Emla cream: circumstances and consequences of overdose [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2012; 139:824–827.

- Bucklin MH, Groth CM. Mortality following rasburicase-induced methemoglobinemia. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47:1353–1358.

- Cheah CY, Lew TE, Seymour JF, Burbury K. Rasburicase causing severe oxidative hemolysis and methemoglobinemia in a patient with previously unrecognized glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Acta Haematol 2013; 130:254–259.

- Druez A, Rahier JF, Hébuterne X. Methaemoglobinaemia and renal failure following mesalazine for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8:900–901.

- Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 34:646–656.

- Groeper K, Katcher K, Tobias JD. Anesthetic management of a patient with methemoglobinemia. South Med J 2003; 96:504–509.

- Haymond S, Cariappa R, Eby CS, Scott MG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenation in methemoglobinemia. Clin Chem 2005; 51:434–444.

- Jang DH, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. Methylene blue for distributive shock: a potential new use of an old antidote. J Med Toxicol 2013; 9:242–249.

A 48-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after 2 days of nonproductive cough, chest discomfort, worsening shortness of breath, and subjective fever. She had a history of systemic sclerosis. She was currently taking prednisone 20 mg daily and aspirin 81 mg daily.

Physical examination revealed tachypnea (28 breaths per minute), and bronchial breath sounds in the left lower chest posteriorly.

The initial laboratory workup revealed:

- Hemoglobin 106 g/L (reference range 115–155)

- Mean corpuscular volume 84 fL (80–100)

- White blood cell count 29.4 × 109/L (3.70–11.0), with 85% neutrophils

- Platelet count 180 × 109/L (150–350)

- Lactate dehydrogenase 312 U/L (100–220).

Chest radiography showed opacification of the lower lobe of the left lung.

She was admitted to the hospital and started treatment with intravenous azithromycin and ceftriaxone for presumed community-acquired pneumonia, based on the clinical presentation and findings on chest radiography. Because of her immunosuppression (due to chronic prednisone therapy) and her high lactate dehydrogenase level, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia was suspected, and because she had a history of allergy to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and pentamidine, she was started on dapsone.

During the next 24 hours, she developed worsening dyspnea, hypoxia, and cyanosis. She was placed on an air-entrainment mask, with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.5. Pulse oximetry showed an oxygen saturation of 85%, but arterial blood gas analysis indicated an oxyhemoglobin concentration of 95%.

THE ‘SATURATION GAP’

1. Which is most likely to have caused the discrepancy between the oxyhemoglobin concentration and the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry in this patient?

- Methemoglobinemia

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Inappropriate placement of the pulse oximeter probe

- Pulmonary embolism

Methemoglobinemia is the most likely cause of the discrepancy between the oxyhemoglobin levels and the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, a phenomenon also known as the “saturation gap.” Other common causes are cyanide poisoning and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Carbon monoxide poisoning, however, does not explain our patient’s cyanosis. On the contrary, carbon monoxide poisoning can actually cause the patient’s lips and mucous membranes to appear unnaturally bright pink. Also, carbon monoxide poisoning raises the blood concentration of carboxyhemoglobin (which has a high affinity for oxygen), and this usually causes pulse oximetry to read inappropriately high, whereas in our patient it read low.

Incorrect placement of the pulse oximeter probe can result in an inaccurate measurement of oxygen saturation. Visualization of the waveform on the plethysmograph or the signal quality index can be used to assess adequate placement of the pulse oximeter probe. However, inadequate probe placement does not explain our patient’s dyspnea and cyanosis.

Pulmonary embolism can lead to hypoxia as a result of ventilation-perfusion mismatch. However, pulmonary embolism leading to low oxygen saturation on pulse oximetry will also lead to concomitantly low oxyhemoglobin levels as measured by arterial blood gas analysis, and this was not seen in our patient.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

Because there was a discrepancy between our patient’s pulse oximetry reading and oxyhemoglobin concentration by arterial blood gas measurement, her methemoglobin level was checked and was found to be 30%, thus confirming the diagnosis of methemoglobinemia.

WHAT IS METHEMOGLOBINEMIA, AND WHAT CAUSES IT?

Oxygen is normally bound to iron in its ferrous (Fe2+) form in hemoglobin to form oxyhemoglobin. Oxidative stress in the body can cause iron to change from the ferrous to the ferric (Fe3+) state, forming methemoglobin. Methemoglobin is normally present in the blood in low levels (< 1% of the total hemoglobin), and ferric iron is reduced and recycled back to the ferrous form by NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase, an enzyme present in red blood cells. This protective mechanism maintains methemoglobin levels within safe limits. But increased production can lead to accumulation of methemoglobin, resulting in dyspnea and hypoxia and the condition referred to as methemoglobinemia.1

Increased levels of methemoglobin relative to normal hemoglobin cause tissue hypoxia by several mechanisms. Methemoglobin cannot efficiently carry oxygen; instead, it binds to water or to a hydroxide ion depending on the pH of the environment.2 Therefore, the hemoglobin molecule does not carry its usual load of oxygen, and hypoxia results from the reduced delivery of oxygen to tissues. In addition, an increased concentration of methemoglobin causes a leftward shift in the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve, representing an increased affinity to bound oxygen in the remaining heme groups. The tightly bound oxygen is not adequately released at the tissue level, thus causing cellular hypoxia.

Methemoglobinemia is most often caused by exposure to an oxidizing chemical or drug that increases production of methemoglobin. In rare cases, it is caused by a congenital deficiency of NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase.3

2. Which of the following drugs can cause methemoglobinemia?

- Acetaminophen

- Dapsone

- Benzocaine

- Primaquine

All four of these drugs are common culprits for causing acquired methemoglobinemia; others include chloroquine, nitroglycerin, and sulfonamides.4–6

The increased production of methemoglobin caused by these drugs overwhelms the protective effect of reducing enzymes and can lead to an accumulation of methemoglobin. However, because of variability in cellular metabolism, not every person who takes these drugs develops dangerous levels of methemoglobin.

Dapsone and benzocaine are the most commonly encountered drugs known to cause methemoglobinemia (Table 1). Dapsone is an anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial agent most commonly used for treating lepromatous leprosy and dermatitis herpetiformis. It is also often prescribed for prophylaxis and treatment of P jirovecii pneumonia in immunosuppressed individuals.7 Benzocaine is a local anesthetic and was commonly used before procedures such as oral or dental surgery, transesophageal echocardiography, and endoscopy.8–10 Even low doses of benzocaine can lead to high levels of methemoglobinemia. However, the availability of other, safer anesthetics now limits the use of benzocaine in major US centers. In addition, the topical anesthetic Emla (lidocaine plus prilocaine) has been recently reported as a cause of methemoglobinemia in infants and children.11,12

Also, potentially fatal methemoglobinemia has been reported in patients with a deficiency of G-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) who received rasburicase, a recombinant version of urate oxidase enzyme used to prevent and treat tumor lysis syndrome.13,14

Lastly, methemoglobinemia has been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with mesalamine.

Although this adverse reaction is rare, clinicians should be aware of it, since these agents are commonly used in everyday medical practice.15

RECOGNIZING THE DANGER SIGNS

The clinical manifestations of methemoglobinemia are directly proportional to the percentage of methemoglobin in red blood cells. Cyanosis generally becomes apparent at concentrations around 15%, at which point the patient may still have no symptoms. Anxiety, lightheadedness, tachycardia, and dizziness manifest at levels of 20% to 30%. Fatigue, confusion, dizziness, tachypnea, and worsening tachycardia occur at levels of 30% to 50%. Levels of 50% to 70% cause coma, seizures, arrhythmias, and acidosis, and levels over 70% are considered lethal.16

While these levels provide a general guideline of symptomatology in an otherwise healthy person, it is important to remember that patients with underlying conditions such as anemia, lung disease (both of which our patient had), sepsis, thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, and sickle cell disease can manifest symptoms at lower concentrations of methemoglobin.1,17

Most patients who develop clinically significant levels of methemoglobin do so within the first few hours of starting one of the culprit drugs.

DIAGNOSIS: METHEMOGLOBINEMIA AND THE SATURATION GAP

In patients with methemoglobinemia, pulse oximetry gives lower values than arterial blood gas oxygen measurements. Regular pulse oximetry works by measuring light absorbance at two distinct wavelengths (660 and 940 nm) to calculate the ratio of oxyhemoglobin to deoxyhemoglobin. Methemoglobin absorbs light at both these wavelengths, thus lowering the pulse oximetry values.1

In contrast, oxygen saturation of arterial blood gas (oxyhemoglobin) is calculated indirectly from the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the blood and does not include oxygen bound to hemoglobin. Therefore, the measured arterial oxygen saturation is often normal in patients with methemoglobinemia since it relies only on inspired oxygen content and is independent of the methemoglobin concentration.18

Oxygen supplementation can raise the level of oxyhemoglobin, which is a measure of dissolved oxygen, but the oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry remains largely unchanged—ie, the saturation gap. A difference of more than 5% between the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry and blood gas analysis is abnormal. Patients with clinically significant methemoglobinemia usually have a saturation gap greater than 10%.

Several other unique features should raise suspicion of methemoglobinemia. It should be considered in a patient presenting with cyanosis out of proportion to the oxygen saturation and in a patient with low oxygen saturation and a normal chest radiograph. Other clues include blood that is chocolate-colored on gross examination, rather than the dark red of deoxygenated blood.

Co-oximetry measures oxygen saturation using different wavelengths of light to distinguish between fractions of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin, but it is not widely available.

THE NEXT STEP

3. What is the next step in the management of our patient?

- Discontinue the dapsone

- Start methylene blue

- Start hyperbaric oxygen

- Give sodium thiosulfate

- Discontinue dapsone and start methylene blue

The next step in her management should be to stop the dapsone and start an infusion of methylene blue. Hyperbaric oxygen is used in treating carbon monoxide poisoning, and sodium thiosulfate is used in treating cyanide toxicity. They would not be appropriate in this patient’s care.

MANAGEMENT OF ACQUIRED METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

The first, most critical step in managing acquired methemoglobinemia is to immediately discontinue the suspected offending agent. In most patients without a concomitant condition such as anemia or lung disease and with a methemoglobin level below 20%, discontinuing the offending agent may suffice. Patients with a level of 20% or greater and patients with cardiac and pulmonary disease, who develop symptoms at lower concentrations of methemoglobin, require infusion of methylene blue.

Methylene blue is converted to its reduced form, leukomethylene blue, by NADPH-methemoglobin reductase. As it is oxidized, leukomethylene blue reduces methemoglobin to hemoglobin. A dose of 1 mg/kg intravenously is given at first. The response is usually dramatic, with a reduction in methemoglobin levels and improvement in symptoms often within 30 to 60 minutes. If levels remain high, the dose can be repeated 1 hour later.19

A caveat: methylene blue therapy should be avoided in patients with complete G6PD deficiency. Methylene blue works through the enzyme NADPH-methemoglobin reductase, and since patients with G6PD deficiency lack this enzyme, methylene blue is ineffective. In fact, since it cannot be reduced, excessive methylene blue can oxidize hemoglobin to methemoglobin, further exacerbating the condition. In patients with partial G6PD deficiency, methylene blue is still recommended as a first-line treatment, but at a lower initial dose (0.3–0.5 mg/kg). However, in patients with significant hemolysis, an exchange transfusion is the only treatment option.

CASE CONCLUDED

Since dapsone was identified as the likely cause of methemoglobinemia in our patient, it was immediately discontinued. Because she was symptomatic, 70 mg of methylene blue was given intravenously. Over the next 60 minutes, her clinical condition improved significantly. A repeat methemoglobin measurement was 3%.

She was discharged home the next day on oral antibiotics to complete treatment for community-acquired pneumonia.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Consider methemoglobinemia in a patient with unexplained cyanosis.

- Pulse oximetry gives lower values than arterial blood gas oxygen measurements in patients with methemoglobinemia, and pulse oximetry readings do not improve with supplemental oxygen.

- A saturation gap greater than 5% strongly suggests methemoglobinemia.

- The diagnosis of methemoglobinemia is confirmed by measuring the methemoglobin concentration.

- Most healthy patients develop symptoms at methemoglobin levels of 20%, but patients with comorbidities can develop symptoms at lower levels.

- A number of drugs can cause methemoglobinemia, even at therapeutic dosages.

- Treatment is generally indicated in patients who have symptoms or in healthy patients who have a methemoglobin level of 20% or greater.

- Identifying and promptly discontinuing the causative agent and initiating methylene blue infusion (1 mg/kg over 5 minutes) is the preferred treatment.

A 48-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after 2 days of nonproductive cough, chest discomfort, worsening shortness of breath, and subjective fever. She had a history of systemic sclerosis. She was currently taking prednisone 20 mg daily and aspirin 81 mg daily.

Physical examination revealed tachypnea (28 breaths per minute), and bronchial breath sounds in the left lower chest posteriorly.

The initial laboratory workup revealed:

- Hemoglobin 106 g/L (reference range 115–155)

- Mean corpuscular volume 84 fL (80–100)

- White blood cell count 29.4 × 109/L (3.70–11.0), with 85% neutrophils

- Platelet count 180 × 109/L (150–350)

- Lactate dehydrogenase 312 U/L (100–220).

Chest radiography showed opacification of the lower lobe of the left lung.

She was admitted to the hospital and started treatment with intravenous azithromycin and ceftriaxone for presumed community-acquired pneumonia, based on the clinical presentation and findings on chest radiography. Because of her immunosuppression (due to chronic prednisone therapy) and her high lactate dehydrogenase level, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia was suspected, and because she had a history of allergy to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and pentamidine, she was started on dapsone.

During the next 24 hours, she developed worsening dyspnea, hypoxia, and cyanosis. She was placed on an air-entrainment mask, with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.5. Pulse oximetry showed an oxygen saturation of 85%, but arterial blood gas analysis indicated an oxyhemoglobin concentration of 95%.

THE ‘SATURATION GAP’

1. Which is most likely to have caused the discrepancy between the oxyhemoglobin concentration and the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry in this patient?

- Methemoglobinemia

- Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Inappropriate placement of the pulse oximeter probe

- Pulmonary embolism

Methemoglobinemia is the most likely cause of the discrepancy between the oxyhemoglobin levels and the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry, a phenomenon also known as the “saturation gap.” Other common causes are cyanide poisoning and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Carbon monoxide poisoning, however, does not explain our patient’s cyanosis. On the contrary, carbon monoxide poisoning can actually cause the patient’s lips and mucous membranes to appear unnaturally bright pink. Also, carbon monoxide poisoning raises the blood concentration of carboxyhemoglobin (which has a high affinity for oxygen), and this usually causes pulse oximetry to read inappropriately high, whereas in our patient it read low.

Incorrect placement of the pulse oximeter probe can result in an inaccurate measurement of oxygen saturation. Visualization of the waveform on the plethysmograph or the signal quality index can be used to assess adequate placement of the pulse oximeter probe. However, inadequate probe placement does not explain our patient’s dyspnea and cyanosis.

Pulmonary embolism can lead to hypoxia as a result of ventilation-perfusion mismatch. However, pulmonary embolism leading to low oxygen saturation on pulse oximetry will also lead to concomitantly low oxyhemoglobin levels as measured by arterial blood gas analysis, and this was not seen in our patient.

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

Because there was a discrepancy between our patient’s pulse oximetry reading and oxyhemoglobin concentration by arterial blood gas measurement, her methemoglobin level was checked and was found to be 30%, thus confirming the diagnosis of methemoglobinemia.

WHAT IS METHEMOGLOBINEMIA, AND WHAT CAUSES IT?

Oxygen is normally bound to iron in its ferrous (Fe2+) form in hemoglobin to form oxyhemoglobin. Oxidative stress in the body can cause iron to change from the ferrous to the ferric (Fe3+) state, forming methemoglobin. Methemoglobin is normally present in the blood in low levels (< 1% of the total hemoglobin), and ferric iron is reduced and recycled back to the ferrous form by NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase, an enzyme present in red blood cells. This protective mechanism maintains methemoglobin levels within safe limits. But increased production can lead to accumulation of methemoglobin, resulting in dyspnea and hypoxia and the condition referred to as methemoglobinemia.1

Increased levels of methemoglobin relative to normal hemoglobin cause tissue hypoxia by several mechanisms. Methemoglobin cannot efficiently carry oxygen; instead, it binds to water or to a hydroxide ion depending on the pH of the environment.2 Therefore, the hemoglobin molecule does not carry its usual load of oxygen, and hypoxia results from the reduced delivery of oxygen to tissues. In addition, an increased concentration of methemoglobin causes a leftward shift in the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve, representing an increased affinity to bound oxygen in the remaining heme groups. The tightly bound oxygen is not adequately released at the tissue level, thus causing cellular hypoxia.

Methemoglobinemia is most often caused by exposure to an oxidizing chemical or drug that increases production of methemoglobin. In rare cases, it is caused by a congenital deficiency of NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase.3

2. Which of the following drugs can cause methemoglobinemia?

- Acetaminophen

- Dapsone

- Benzocaine

- Primaquine

All four of these drugs are common culprits for causing acquired methemoglobinemia; others include chloroquine, nitroglycerin, and sulfonamides.4–6

The increased production of methemoglobin caused by these drugs overwhelms the protective effect of reducing enzymes and can lead to an accumulation of methemoglobin. However, because of variability in cellular metabolism, not every person who takes these drugs develops dangerous levels of methemoglobin.

Dapsone and benzocaine are the most commonly encountered drugs known to cause methemoglobinemia (Table 1). Dapsone is an anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial agent most commonly used for treating lepromatous leprosy and dermatitis herpetiformis. It is also often prescribed for prophylaxis and treatment of P jirovecii pneumonia in immunosuppressed individuals.7 Benzocaine is a local anesthetic and was commonly used before procedures such as oral or dental surgery, transesophageal echocardiography, and endoscopy.8–10 Even low doses of benzocaine can lead to high levels of methemoglobinemia. However, the availability of other, safer anesthetics now limits the use of benzocaine in major US centers. In addition, the topical anesthetic Emla (lidocaine plus prilocaine) has been recently reported as a cause of methemoglobinemia in infants and children.11,12

Also, potentially fatal methemoglobinemia has been reported in patients with a deficiency of G-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) who received rasburicase, a recombinant version of urate oxidase enzyme used to prevent and treat tumor lysis syndrome.13,14

Lastly, methemoglobinemia has been reported in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with mesalamine.

Although this adverse reaction is rare, clinicians should be aware of it, since these agents are commonly used in everyday medical practice.15

RECOGNIZING THE DANGER SIGNS

The clinical manifestations of methemoglobinemia are directly proportional to the percentage of methemoglobin in red blood cells. Cyanosis generally becomes apparent at concentrations around 15%, at which point the patient may still have no symptoms. Anxiety, lightheadedness, tachycardia, and dizziness manifest at levels of 20% to 30%. Fatigue, confusion, dizziness, tachypnea, and worsening tachycardia occur at levels of 30% to 50%. Levels of 50% to 70% cause coma, seizures, arrhythmias, and acidosis, and levels over 70% are considered lethal.16

While these levels provide a general guideline of symptomatology in an otherwise healthy person, it is important to remember that patients with underlying conditions such as anemia, lung disease (both of which our patient had), sepsis, thalassemia, G6PD deficiency, and sickle cell disease can manifest symptoms at lower concentrations of methemoglobin.1,17

Most patients who develop clinically significant levels of methemoglobin do so within the first few hours of starting one of the culprit drugs.

DIAGNOSIS: METHEMOGLOBINEMIA AND THE SATURATION GAP

In patients with methemoglobinemia, pulse oximetry gives lower values than arterial blood gas oxygen measurements. Regular pulse oximetry works by measuring light absorbance at two distinct wavelengths (660 and 940 nm) to calculate the ratio of oxyhemoglobin to deoxyhemoglobin. Methemoglobin absorbs light at both these wavelengths, thus lowering the pulse oximetry values.1

In contrast, oxygen saturation of arterial blood gas (oxyhemoglobin) is calculated indirectly from the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the blood and does not include oxygen bound to hemoglobin. Therefore, the measured arterial oxygen saturation is often normal in patients with methemoglobinemia since it relies only on inspired oxygen content and is independent of the methemoglobin concentration.18

Oxygen supplementation can raise the level of oxyhemoglobin, which is a measure of dissolved oxygen, but the oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry remains largely unchanged—ie, the saturation gap. A difference of more than 5% between the oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry and blood gas analysis is abnormal. Patients with clinically significant methemoglobinemia usually have a saturation gap greater than 10%.

Several other unique features should raise suspicion of methemoglobinemia. It should be considered in a patient presenting with cyanosis out of proportion to the oxygen saturation and in a patient with low oxygen saturation and a normal chest radiograph. Other clues include blood that is chocolate-colored on gross examination, rather than the dark red of deoxygenated blood.

Co-oximetry measures oxygen saturation using different wavelengths of light to distinguish between fractions of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin, but it is not widely available.

THE NEXT STEP

3. What is the next step in the management of our patient?

- Discontinue the dapsone

- Start methylene blue

- Start hyperbaric oxygen

- Give sodium thiosulfate

- Discontinue dapsone and start methylene blue

The next step in her management should be to stop the dapsone and start an infusion of methylene blue. Hyperbaric oxygen is used in treating carbon monoxide poisoning, and sodium thiosulfate is used in treating cyanide toxicity. They would not be appropriate in this patient’s care.

MANAGEMENT OF ACQUIRED METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

The first, most critical step in managing acquired methemoglobinemia is to immediately discontinue the suspected offending agent. In most patients without a concomitant condition such as anemia or lung disease and with a methemoglobin level below 20%, discontinuing the offending agent may suffice. Patients with a level of 20% or greater and patients with cardiac and pulmonary disease, who develop symptoms at lower concentrations of methemoglobin, require infusion of methylene blue.

Methylene blue is converted to its reduced form, leukomethylene blue, by NADPH-methemoglobin reductase. As it is oxidized, leukomethylene blue reduces methemoglobin to hemoglobin. A dose of 1 mg/kg intravenously is given at first. The response is usually dramatic, with a reduction in methemoglobin levels and improvement in symptoms often within 30 to 60 minutes. If levels remain high, the dose can be repeated 1 hour later.19

A caveat: methylene blue therapy should be avoided in patients with complete G6PD deficiency. Methylene blue works through the enzyme NADPH-methemoglobin reductase, and since patients with G6PD deficiency lack this enzyme, methylene blue is ineffective. In fact, since it cannot be reduced, excessive methylene blue can oxidize hemoglobin to methemoglobin, further exacerbating the condition. In patients with partial G6PD deficiency, methylene blue is still recommended as a first-line treatment, but at a lower initial dose (0.3–0.5 mg/kg). However, in patients with significant hemolysis, an exchange transfusion is the only treatment option.

CASE CONCLUDED

Since dapsone was identified as the likely cause of methemoglobinemia in our patient, it was immediately discontinued. Because she was symptomatic, 70 mg of methylene blue was given intravenously. Over the next 60 minutes, her clinical condition improved significantly. A repeat methemoglobin measurement was 3%.

She was discharged home the next day on oral antibiotics to complete treatment for community-acquired pneumonia.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Consider methemoglobinemia in a patient with unexplained cyanosis.

- Pulse oximetry gives lower values than arterial blood gas oxygen measurements in patients with methemoglobinemia, and pulse oximetry readings do not improve with supplemental oxygen.

- A saturation gap greater than 5% strongly suggests methemoglobinemia.

- The diagnosis of methemoglobinemia is confirmed by measuring the methemoglobin concentration.

- Most healthy patients develop symptoms at methemoglobin levels of 20%, but patients with comorbidities can develop symptoms at lower levels.

- A number of drugs can cause methemoglobinemia, even at therapeutic dosages.

- Treatment is generally indicated in patients who have symptoms or in healthy patients who have a methemoglobin level of 20% or greater.

- Identifying and promptly discontinuing the causative agent and initiating methylene blue infusion (1 mg/kg over 5 minutes) is the preferred treatment.

- Cortazzo JA, Lichtman AD. Methemoglobinemia: a review and recommendations for management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014; 28:1055–1059.

- Margulies DR, Manookian CM. Methemoglobinemia as a cause of respiratory failure. J Trauma 2002; 52:796–797.

- Skold A, Cosco DL, Klein R. Methemoglobinemia: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. South Med J 2011; 104:757–761.

- Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:265–273.

- Kanji HD, Mithani S, Boucher P, Dias VC, Yarema MC. Coma, metabolic acidosis, and methemoglobinemia in a patient with acetaminophen toxicity. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2013; 20:e207–e211.

- Kawasumi H, Tanaka E, Hoshi D, Kawaguchi Y, Yamanaka H. Methemoglobinemia induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Intern Med 2013; 52:1741–1743.

- Wieringa A, Bethlehem C, Hoogendoorn M, van der Maten J, van Roon EN. Very late recovery of dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014; 52:80–81.

- Barclay JA, Ziemba SE, Ibrahim RB. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia: a primer for clinicians. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:1103–1115.

- Taleb M, Ashraf Z, Valavoor S, Tinkel J. Evaluation and management of acquired methemoglobinemia associated with topical benzocaine use. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2013; 13:325–330.

- Chowdhary S, Bukoye B, Bhansali AM, et al. Risk of topical anesthetic-induced methemoglobinemia: a 10-year retrospective case-control study. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:771–776.

- Larson A, Stidham T, Banerji S, Kaufman J. Seizures and methemoglobinemia in an infant after excessive EMLA application. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013; 29:377–379.

- Schmitt C, Matulic M, Kervégant M, et al. Methaemoglobinaemia in a child treated with Emla cream: circumstances and consequences of overdose [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2012; 139:824–827.

- Bucklin MH, Groth CM. Mortality following rasburicase-induced methemoglobinemia. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47:1353–1358.

- Cheah CY, Lew TE, Seymour JF, Burbury K. Rasburicase causing severe oxidative hemolysis and methemoglobinemia in a patient with previously unrecognized glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Acta Haematol 2013; 130:254–259.

- Druez A, Rahier JF, Hébuterne X. Methaemoglobinaemia and renal failure following mesalazine for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8:900–901.

- Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 34:646–656.

- Groeper K, Katcher K, Tobias JD. Anesthetic management of a patient with methemoglobinemia. South Med J 2003; 96:504–509.

- Haymond S, Cariappa R, Eby CS, Scott MG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenation in methemoglobinemia. Clin Chem 2005; 51:434–444.

- Jang DH, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. Methylene blue for distributive shock: a potential new use of an old antidote. J Med Toxicol 2013; 9:242–249.

- Cortazzo JA, Lichtman AD. Methemoglobinemia: a review and recommendations for management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014; 28:1055–1059.

- Margulies DR, Manookian CM. Methemoglobinemia as a cause of respiratory failure. J Trauma 2002; 52:796–797.

- Skold A, Cosco DL, Klein R. Methemoglobinemia: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. South Med J 2011; 104:757–761.

- Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:265–273.

- Kanji HD, Mithani S, Boucher P, Dias VC, Yarema MC. Coma, metabolic acidosis, and methemoglobinemia in a patient with acetaminophen toxicity. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2013; 20:e207–e211.

- Kawasumi H, Tanaka E, Hoshi D, Kawaguchi Y, Yamanaka H. Methemoglobinemia induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Intern Med 2013; 52:1741–1743.

- Wieringa A, Bethlehem C, Hoogendoorn M, van der Maten J, van Roon EN. Very late recovery of dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014; 52:80–81.

- Barclay JA, Ziemba SE, Ibrahim RB. Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia: a primer for clinicians. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45:1103–1115.

- Taleb M, Ashraf Z, Valavoor S, Tinkel J. Evaluation and management of acquired methemoglobinemia associated with topical benzocaine use. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2013; 13:325–330.

- Chowdhary S, Bukoye B, Bhansali AM, et al. Risk of topical anesthetic-induced methemoglobinemia: a 10-year retrospective case-control study. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173:771–776.

- Larson A, Stidham T, Banerji S, Kaufman J. Seizures and methemoglobinemia in an infant after excessive EMLA application. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013; 29:377–379.

- Schmitt C, Matulic M, Kervégant M, et al. Methaemoglobinaemia in a child treated with Emla cream: circumstances and consequences of overdose [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2012; 139:824–827.

- Bucklin MH, Groth CM. Mortality following rasburicase-induced methemoglobinemia. Ann Pharmacother 2013; 47:1353–1358.

- Cheah CY, Lew TE, Seymour JF, Burbury K. Rasburicase causing severe oxidative hemolysis and methemoglobinemia in a patient with previously unrecognized glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Acta Haematol 2013; 130:254–259.

- Druez A, Rahier JF, Hébuterne X. Methaemoglobinaemia and renal failure following mesalazine for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8:900–901.

- Wright RO, Lewander WJ, Woolf AD. Methemoglobinemia: etiology, pharmacology, and clinical management. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 34:646–656.

- Groeper K, Katcher K, Tobias JD. Anesthetic management of a patient with methemoglobinemia. South Med J 2003; 96:504–509.

- Haymond S, Cariappa R, Eby CS, Scott MG. Laboratory assessment of oxygenation in methemoglobinemia. Clin Chem 2005; 51:434–444.

- Jang DH, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. Methylene blue for distributive shock: a potential new use of an old antidote. J Med Toxicol 2013; 9:242–249.

Why are we doing cardiovascular outcome trials in type 2 diabetes?

A 50-year-old man with hypertension presents to the internal medicine clinic. He has been an active smoker for 15 years and smokes 1 pack of cigarettes a day. He was recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus after routine blood work revealed his hemoglobin A1c level was elevated at 7.5%. He has no current complaints but is concerned about his future risk of a heart attack or stroke.

THE BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in US adults (age > 20) has tripled during the last 30 years to 28.9 million, or 12% of the population in this age group.1 Globally, 382 million people had a diagnosis of diabetes in 2013, and with the increasing prevalence of obesity and adoption of a Western diet, this number is expected to escalate to 592 million by 2035.2

HOW GREAT IS THE CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PEOPLE WITH DIABETES?

Diabetes mellitus is linked to a twofold increase in the risk of adverse cardiovascular events even after adjusting for risk from hypertension and smoking.3 In early studies, diabetic people with no history of myocardial infarction were shown to have a lifetime risk of infarction similar to that in nondiabetic people who had already had an infarction,4 thus establishing diabetes as a “coronary artery disease equivalent.” Middle-aged men diagnosed with diabetes lose an average of 6 years of life and women lose 7 years compared with those without diabetes, with cardiovascular morbidity contributing to more than half of this reduction in life expectancy (Figure 1).5

Numerous mechanisms have been hypothesized to account for the association between diabetes and cardiovascular risk, including increased inflammation, endothelial and platelet dysfunction, and autonomic dysregulation.6

Can we modify cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes?

Although fasting blood glucose levels strongly correlate with future cardiovascular risk, whether lowering blood glucose levels with medications will reduce cardiovascular risk has been uncertain.3 Lowering glucose beyond what is current standard practice has not been shown to significantly improve cardiovascular outcomes or mortality rates, and it comes at the price of an increased risk of hypoglycemic events.

No macrovascular benefit from lowering hemoglobin A1c beyond the standard of care

UKPDS.7 Launched in 1977, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study was designed to investigate whether intensive blood glucose control reduces the risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. The study randomized nearly 4,000 patients newly diagnosed with diabetes to intensive treatment (with a sulfonylurea or insulin to keep fasting blood glucose levels below 110 mg/dL) or to conventional treatment (with diet alone unless hyperglycemic symptoms or a fasting blood glucose more than 270 mg/dL arose) for 10 years.

Multivariate analysis from the overall study population revealed a direct correlation between hemoglobin A1c levels and adverse cardiovascular events. Higher hemoglobin A1c was associated with markedly more:

- Fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarctions (14% increased risk for every 1% rise in hemoglobin A1c)

- Fatal and nonfatal strokes (12% increased risk per 1% rise in hemoglobin A1c)

- Amputations or deaths from peripheral vascular disease (43% increase per 1% rise)

- Heart failure (16% increase per 1% rise).

While intensive therapy was associated with significant reductions in microvascular events (retinopathy and proteinuria), there was no significant difference in the incidence of major macrovascular events (myocardial infarction or stroke).

The mean hemoglobin A1c level at the end of the study was about 8% in the standard-treatment group and about 7% in the intensive-treatment group. Were these levels low enough to yield a significant risk reduction? Since lower hemoglobin A1c levels are associated with lower risk of myocardial infarction, it seemed reasonable to do further studies with more intensive treatment to further lower hemoglobin A1c goals.

ADVANCE.8 The Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease trial randomized more than 11,000 participants with type 2 diabetes to either usual care or intensive therapy with a goal of achieving a hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or less. During 5 years of follow-up, the usual-care group averaged a hemoglobin A1c of 7.3%, compared with 6.5% in the intensive-treatment group.

No significant differences between the two groups were observed in the incidence of major macrovascular events, including myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from any cause. The intensive-treatment group had fewer major microvascular events, with most of the benefit being in the form of a lower incidence of proteinuria, and with no significant effect on retinopathy. Severe hypoglycemia, although uncommon, was more frequent in the intensive-treatment group.

ACCORD.9 The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes trial went one step further. This trial randomized more than 10,000 patients with type 2 diabetes to receive either intensive therapy (targeting hemoglobin A1c ≤ 6.0%) or standard therapy (hemoglobin A1c 7.0%–7.9%). At 1 year, the mean hemoglobin A1c levels were stable at 6.4% in the intensive-therapy group and 7.5% in the standard-therapy group.

The trial was stopped at 3.5 years because of a higher rate of death in the intensive-therapy group, with a hazard ratio of 1.22, predominantly from an increase in adverse cardiovascular events. The intensive-therapy group also had a significantly higher incidence of hypoglycemia.

VADT.10 The Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial randomized 1,791 patients with type 2 diabetes who had a suboptimal response to conventional therapy to receive intensive therapy aimed at reducing hemoglobin A1c by 1.5 percentage points or standard therapy. After a follow-up of 5.6 years, median hemoglobin A1c levels were 8.4% in the standard-therapy group and 6.9% in the intensive-therapy group. No differences were found between the two groups in the incidence of major cardiovascular events, death, or microvascular complications, with the exception of a lower rate of progression of albuminuria in the intensive-therapy group. The rates of adverse events, primarily hypoglycemia, were higher in the intensive-therapy group.

Based on these negative trials and concern about potential harm with intensive glucose-lowering strategies, standard guidelines continue to recommend moderate glucose-lowering strategies for patients with diabetes. The guidelines broadly recommend targeting a hemoglobin A1c of 7% or less while advocating a less ambitious goal of lower than 7.5% or 8.0% in older patients who may be prone to hypoglycemia.11

STRATEGIES TO REDUCE CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN DIABETES

While the incidence of diabetes mellitus has risen alarmingly, the incidence of cardiovascular complications of diabetes has declined over the years. Lowering blood glucose has not been the critical factor mediating this risk reduction. In addition to smoking cessation, proven measures that clearly reduce long-term cardiovascular risk in diabetes are blood pressure control and reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with statins.

Lower the blood pressure to less than 140 mm Hg

ADVANCE.12 In the ADVANCE trial, in addition to being randomized to usual vs intensive glucose-lowering therapy, participants were also simultaneously randomized to receive either placebo or the combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a diuretic (ie, perindopril and indapamide). Blood pressure was reduced by a mean of 5.6 mm Hg systolic and 2.2 mm Hg diastolic in the active-treatment group. This moderate reduction in blood pressure was associated with an 18% relative risk reduction in death from cardiovascular disease and a 14% relative risk reduction in death from any cause.

The ACCORD trial13 lowered systolic blood pressure even more in the intensive-treatment group, with a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg compared with less than 140 mm Hg in the control group. Intensive therapy did not prove to significantly reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events and was associated with a significantly higher rate of serious adverse events.

Therefore, while antihypertensive therapy lowered the mortality rate in diabetic patients, lowering blood pressure beyond conventional blood pressure targets did not decrease the risk more. The latest hypertension treatment guidelines (from the eighth Joint National Committee) emphasize a blood pressure goal of 140/90 mm Hg or less in adults with diabetes.14

Prescribe a statin regardless of the baseline lipid level

The Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS) randomized nearly 3,000 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and no history of cardiovascular disease to either atorvastatin 10 mg or placebo regardless of cholesterol status. The trial was terminated 2 years early because a prespecified efficacy end point had already been met: the treatment group experienced a markedly lower incidence of major cardiovascular events, including stroke.15

A large meta-analysis of randomized trials of statins noted a 9% reduction in all-cause mortality (relative risk [RR] 0.91, 99% confidence interval 0.82–1.01; P = .02) per mmol/L reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with diabetes mellitus.16 Use of statins also led to significant reductions in rates of major coronary events (RR 0.78), coronary revascularization (RR 0.75), and stroke (RR 0.79).

The latest American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines endorse moderate-intensity or high-intensity statin treatment in patients with diabetes who are over age 40.17

Encourage smoking cessation

Smoking increases the lifetime risk of developing type 2 diabetes.18 It is also associated with premature development of microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes,19 and it leads to increased mortality risk in people with diabetes mellitus in a dose-dependent manner.20 Therefore, smoking cessation remains paramount in reducing cardiovascular risk, and patients should be encouraged to quit as soon as possible.

Role of antiplatelet agents

Use of antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes is controversial. Initial studies showed a potential reduction in the incidence of myocardial infarction in men and stroke in women with diabetes with low-dose aspirin.21,22 Subsequent randomized trials and meta-analyses, however, yielded contrasting results, showing no benefit in cardiovascular risk reduction and potential risk of bleeding and other gastrointestinal adverse effects.23,24

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people who have no history of cardiovascular disease. In contrast, the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association endorse low-dose aspirin (75–162 mg/day) for adults with diabetes and no history of vascular disease who are at increased cardiovascular risk (estimated 10-year risk of events > 10%) and who are not at increased risk of bleeding.

In the absence of a clear consensus and given the lack of randomized data, the role of aspirin in patients with diabetes remains controversial.

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF STRESS TESTING IN ASYMPTOMATIC DIABETIC PATIENTS?

People with diabetes also have a high incidence of silent (asymptomatic) ischemia that potentially leads to worse outcomes.25 Whether screening for silent ischemia improves outcomes in these patients is debatable.

The Detection of Anemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics (DIAD) trial randomized more than 1,000 asymptomatic diabetic participants to either screening for coronary artery disease with stress testing or no screening.26 Over a 5-year follow-up, there was no significant difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction and death from cardiac causes.

The guidelines remain divided on this clinical conundrum. While the American Diabetes Association recommends against routine screening for coronary artery disease in asymptomatic patients with diabetes, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend screening with radionuclide imaging in patients with diabetes and a high risk of coronary artery disease.27

ROLE OF REVASCULARIZATION IN DIABETIC PATIENTS WITH STABLE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Patients with coronary artery disease and diabetes fare worse than those without diabetes, despite revascularization by coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).28

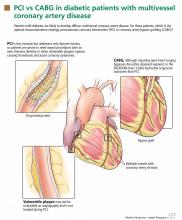

The choice of CABG or PCI as the preferred revascularization strategy was recently studied in the Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients With DM: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease (FREEDOM) trial.29 This study randomized 1,900 patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease to revascularization with PCI or CABG. After 5 years, there was a significantly lower rate of death and myocardial infarction with CABG than with PCI.

The role of revascularization in patients with diabetes and stable coronary artery disease has also been questioned. The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 DM (BARI-2D) randomized 2,368 patients with diabetes and stable coronary artery disease to undergo revascularization (PCI or CABG) or to receive intensive medical therapy alone.30 At 5 years, there was no significant difference in the rates of death and major cardiovascular events between patients undergoing revascularization and those undergoing medical therapy alone. Subgroup analysis revealed a potential benefit with CABG over medical therapy in patients with more extensive coronary artery disease.31

CAN DIABETES THERAPY CAUSE HARM?

New diabetes drugs must show no cardiovascular harm

Several drugs that were approved purely on the basis of their potential to reduce blood glucose were reevaluated for impact on adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Muraglitazar is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist that was shown in phase 2 and 3 studies to dramatically lower triglyceride levels in a dose-dependent fashion while raising high-density lipoprotein levels and being neutral to low-density lipoprotein levels. It also lowers blood glucose. The FDA Advisory Committee voted to approve its use for type 2 diabetes based on phase 2 trial data. But soon after, a meta-analysis revealed that the drug was associated with more than twice the incidence of cardiovascular complications and death than standard therapy.32 Further development of this drug subsequently ceased.

A similar meta-analysis was performed on rosiglitazone, a drug that has been available since 1997 and had been used by millions of patients. Rosiglitazone was also found to be associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular death, as well as death from all causes.33

In light of these findings, the FDA in 2008 issued new guidelines to the diabetes drug development industry. Henceforth, new diabetes drugs must not only lower blood glucose, they must also be shown in a large clinical trial not to increase cardiovascular risk.

Current trials will provide critical information

Numerous trials are now under way to assess cardiovascular outcomes with promising new diabetes drugs. Tens of thousands of patients are involved in trials testing dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, sodium-glucose-linked transporter-2 agents, and a GPR40 agonist. Because of the change in guidelines, results over the next decade should reveal much more about the impact of lowering blood glucose on heart disease than we learned in the previous century.

Two apparently neutral but clinically relevant trials recently examined cardiovascular outcomes associated with diabetes drugs.

EXAMINE.34 The Examination of Cardiovascular Outcomes Study of Alogliptin Versus Standard of Care study randomized 5,380 patients with type 2 diabetes and a recent acute coronary syndrome event (acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina requiring hospitalization) to receive either alogliptin (a DPP-4 inhibitor) or placebo in addition to existing standard diabetes and cardiovascular therapy. Patients were followed for up to 40 months (median 18 months). Hemoglobin A1c levels were significantly lower with alogliptin than with placebo, but the time to the primary end point of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was not significantly different between the two groups.

SAVOR.35 The Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with DM (SAVOR–TIMI 53) trial randomized more than 16,000 patients with established cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors to either the DPP-4 inhibitor saxagliptin or placebo. The patients’ physicians were permitted to adjust all other medications, including standard diabetes medications. The median treatment period was just over 2 years. Similar to EXAMINE, this study found no difference between the two groups in the primary end point of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke, even though glycemic control was better in the saxagliptin group.

Thus, both drugs were shown not to increase cardiovascular risk, an FDA criterion for drug marketing and approval.

CONTROL MODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

There has been an alarming rise in the incidence of diabetes and obesity throughout the world. Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in patients with diabetes. While elevated blood glucose in diabetic patients leads to increased cardiovascular risk, efforts to reduce blood glucose to euglycemic levels may not lead to a reduction in this risk and may even cause harm.

Success in cardiovascular risk reduction in addition to glucose-lowering remains the holy grail in the development of new diabetes drugs. But in the meantime, aggressive control of other modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and hyperlipidemia remains critical to reducing cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2014.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th edition. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2013.

- Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010; 375:2215–2222.

- Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:229–234.

- Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:829–841.

- Hess K, Marx N, Lehrke M. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes: the vulnerable patient. Eur Heart J Suppl 2012; 14(suppl B):B4–B13.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- ADVANCE Collaborative Group; Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2560–2572.

- Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group; Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2545–2559.

- Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al; VADT Investigators. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:129–139.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35:1364–1379.

- Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370:829–840.

- Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:1575–1585.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee. JAMA 2014; 311:507–520.

- Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 364:685–696.

- Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2008; 371:117–125.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. Treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: synopsis of the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:339–343.

- Benjamin RM. A report of the Surgeon General. How tobacco smoke causes disease...what it means to you. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2010/consumer_booklet/pdfs/consumer.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2014.

- Haire-Joshu D, Glasgow RE, Tibbs TL. Smoking and diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999; 22:1887–1898.

- Chaturvedi N, Stevens L, Fuller JH. Which features of smoking determine mortality risk in former cigarette smokers with diabetes? The World Health Organization Multinational Study Group. Diabetes Care 1997; 20:1266–1272.

- ETDRS Investigators. Aspirin effects on mortality and morbidity in patients with diabetes mellitus. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report 14. JAMA 1992; 268:1292–1300.

- Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1293–1304.

- Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, et al. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2008; 337:a1840.

- Simpson SH, Gamble JM, Mereu L, Chambers T. Effect of aspirin dose on mortality and cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26:1336–1344.

- Janand-Delenne B, Savin B, Habib G, Bory M, Vague P, Lassmann-Vague V. Silent myocardial ischemia in patients with diabetes: who to screen. Diabetes Care 1999; 22:1396–1400.

- Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, et al. Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 301:1547–1555.

- Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56:e50–e103.

- Roffi M, Angiolillo DJ, Kappetein AP. Current concepts on coronary revascularization in diabetic patients. Eur Heart J 2011; 32:2748–2757.

- Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2375–2384.

- Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, et al. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2503–2515.

- Chaitman BR, Hardison RM, Adler D, et al. The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes randomized trial of different treatment strategies in type 2 diabetes mellitus with stable ischemic heart disease: impact of treatment strategy on cardiac mortality and myocardial infarction. Circulation 2009; 120:2529–2540.

- Nissen SE, Wolski K, Topol EJ. Effect of muraglitazar on death and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2005; 294:2581–2586.

- Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457–2471.

- White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1327–1335.

- Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1317–1326.

A 50-year-old man with hypertension presents to the internal medicine clinic. He has been an active smoker for 15 years and smokes 1 pack of cigarettes a day. He was recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus after routine blood work revealed his hemoglobin A1c level was elevated at 7.5%. He has no current complaints but is concerned about his future risk of a heart attack or stroke.

THE BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in US adults (age > 20) has tripled during the last 30 years to 28.9 million, or 12% of the population in this age group.1 Globally, 382 million people had a diagnosis of diabetes in 2013, and with the increasing prevalence of obesity and adoption of a Western diet, this number is expected to escalate to 592 million by 2035.2

HOW GREAT IS THE CARDIOVASCULAR RISK IN PEOPLE WITH DIABETES?

Diabetes mellitus is linked to a twofold increase in the risk of adverse cardiovascular events even after adjusting for risk from hypertension and smoking.3 In early studies, diabetic people with no history of myocardial infarction were shown to have a lifetime risk of infarction similar to that in nondiabetic people who had already had an infarction,4 thus establishing diabetes as a “coronary artery disease equivalent.” Middle-aged men diagnosed with diabetes lose an average of 6 years of life and women lose 7 years compared with those without diabetes, with cardiovascular morbidity contributing to more than half of this reduction in life expectancy (Figure 1).5

Numerous mechanisms have been hypothesized to account for the association between diabetes and cardiovascular risk, including increased inflammation, endothelial and platelet dysfunction, and autonomic dysregulation.6

Can we modify cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes?

Although fasting blood glucose levels strongly correlate with future cardiovascular risk, whether lowering blood glucose levels with medications will reduce cardiovascular risk has been uncertain.3 Lowering glucose beyond what is current standard practice has not been shown to significantly improve cardiovascular outcomes or mortality rates, and it comes at the price of an increased risk of hypoglycemic events.

No macrovascular benefit from lowering hemoglobin A1c beyond the standard of care

UKPDS.7 Launched in 1977, the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study was designed to investigate whether intensive blood glucose control reduces the risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. The study randomized nearly 4,000 patients newly diagnosed with diabetes to intensive treatment (with a sulfonylurea or insulin to keep fasting blood glucose levels below 110 mg/dL) or to conventional treatment (with diet alone unless hyperglycemic symptoms or a fasting blood glucose more than 270 mg/dL arose) for 10 years.

Multivariate analysis from the overall study population revealed a direct correlation between hemoglobin A1c levels and adverse cardiovascular events. Higher hemoglobin A1c was associated with markedly more:

- Fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarctions (14% increased risk for every 1% rise in hemoglobin A1c)