User login

Coalescing Papules on Bilateral Mastectomy Scars

The Diagnosis: Scar Sarcoidosis

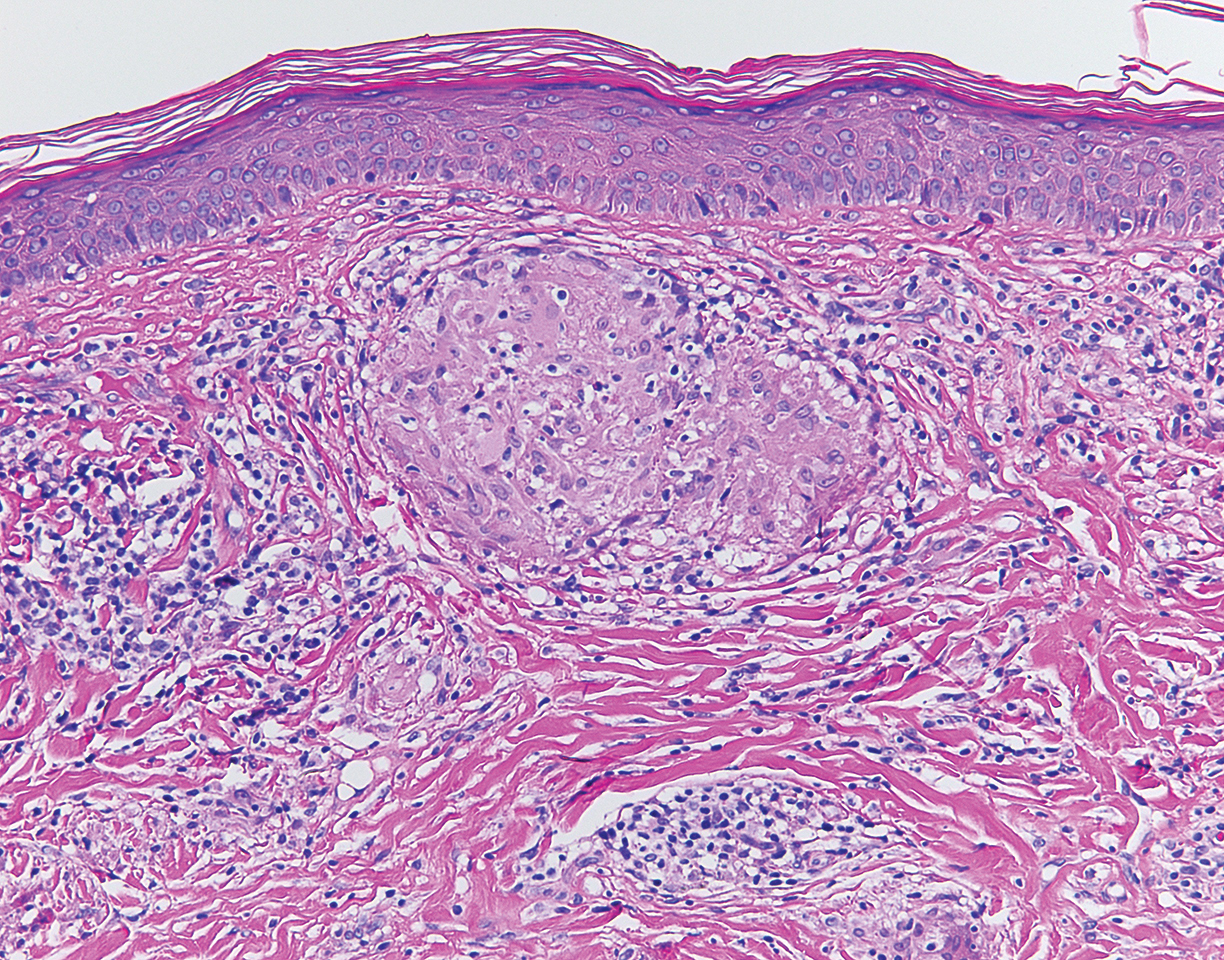

Although scars on both breasts were involved, the decision was made to biopsy the right breast because the patient reported more pain on the left breast. Biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with scar sarcoidosis (Figure). Additional screening tests were performed to evaluate for any systemic involvement of sarcoidosis, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, tuberculosis serology screening, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests. She also was referred to rheumatology and ophthalmology for consultation. The results of all screenings were within reference range, and no sign of systemic sarcoidosis was found. She was treated with hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% for several weeks without notable improvement. She elected not to pursue any additional treatment and to monitor the symptoms with close follow-up only. One year after the initial visit, the skin lesions spontaneously and notably improved.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs. It also can involve the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bones, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been documented in the literature since the late 1800s and occurs in up to one-third of sarcoid patients.1 Cutaneous lesions developing within a preexisting scar is a well-known variant, occurring in 29% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis in one clinical study (N=818).2 There have been many reports describing scar sarcoidosis, with its development at prior sites of surgery, trauma, acne, or venipuncture.3 Other case reports have described variants of scar sarcoidosis developing at sites of hyaluronic acid injection, laser surgery, ritual scarification, tattoos, and desensitization injections, as well as prior herpes zoster infections.4-9

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations. Lesions can be described as specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions demonstrate the typical sarcoid granuloma on histology and more often are seen in chronic disease, while nonspecific lesions more often are seen in acute disease.3,10 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of a specific lesion in which old scars become infiltrated with noncaseating granulomas. The granulomas typically are in the superficial dermis but may involve the full thickness of the dermis, extending into the subcutaneous tissue.11 The cause of granulomas developing in scars is unknown. Prior contamination of the scar with foreign material, possibly at the time of the trauma, is a possible underlying cause.12

Typical scar sarcoidosis presents as swollen, erythematous, indurated lesions with a purple-red hue that may become brown.3,12 Tenderness or pruritus also may be present.13 Interestingly, our patient's scar sarcoidosis presented with a yellow hue at both mastectomy sites.

Diagnosing scar sarcoidosis can be challenging. Patients are diagnosed with sarcoidosis when a compatible clinical or radiologic picture is present along with histologic evidence of a noncaseating granuloma and other potential causes are excluded.11 The differential includes an infectious etiology, other types of granulomatous dermatitis, hypertrophic scar, keloid, or foreign body granuloma.

Scar sarcoidosis can be isolated in occurrence. It also can precede or occur concomitantly or during a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.10 Most commonly, patients with scar sarcoidosis also have systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, and changing scars may be an indicator of disease exacerbation or relapse.10 For patients who only demonstrate specific skin lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, approximately 30% develop systemic involvement later in life.3 For this reason, close monitoring and regular follow-up are necessary.

Treatment of scar sarcoidosis is dependent on the extent of the disease and presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine phosphate, and methotrexate all have been shown to be helpful in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.3 For scar sarcoidosis that is limited to only the scar site, as seen in our case, monitoring and close follow-up is acceptable. Topical steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. Scar sarcoidosis can resolve slowly and spontaneously over time.10 Our patient notably improved 1 year after the initial presentation without treatment.

Scar sarcoidosis is a well-documented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that can have important implications for diagnosing systemic sarcoidosis. Although there are typical lesions that represent scar sarcoidosis, it is important to have a high degree of suspicion with any changing scar. Once diagnosed through biopsy, a thorough investigation for systemic signs of sarcoidosis needs to be performed to guide treatment.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888.

- Dal Sacco D, Cozzani E, Parodi A, et al. Scar sarcoidosis after hyaluronic acid injection. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:411-412.

- Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis. 2004;73:53-55.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

- Healsmith MF, Hutchinson PE. The development of scar sarcoidosis at the site of desensitization injections. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:369-370.

- Singal A, Vij A, Pandhi D. Post herpes-zoster scar sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:77-79.

- Chudomirova K, Velichkova L, Anavi B, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:360-361.

- Selim A, Ehrsam E, Atassi MB, et al. Scar sarcoidosis: a case report and brief review. Cutis. 2006;78:418-422.

- Singal A, Thami GP, Goraya JS. Scar sarcoidosis in childhood: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:244-246.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

The Diagnosis: Scar Sarcoidosis

Although scars on both breasts were involved, the decision was made to biopsy the right breast because the patient reported more pain on the left breast. Biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with scar sarcoidosis (Figure). Additional screening tests were performed to evaluate for any systemic involvement of sarcoidosis, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, tuberculosis serology screening, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests. She also was referred to rheumatology and ophthalmology for consultation. The results of all screenings were within reference range, and no sign of systemic sarcoidosis was found. She was treated with hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% for several weeks without notable improvement. She elected not to pursue any additional treatment and to monitor the symptoms with close follow-up only. One year after the initial visit, the skin lesions spontaneously and notably improved.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs. It also can involve the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bones, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been documented in the literature since the late 1800s and occurs in up to one-third of sarcoid patients.1 Cutaneous lesions developing within a preexisting scar is a well-known variant, occurring in 29% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis in one clinical study (N=818).2 There have been many reports describing scar sarcoidosis, with its development at prior sites of surgery, trauma, acne, or venipuncture.3 Other case reports have described variants of scar sarcoidosis developing at sites of hyaluronic acid injection, laser surgery, ritual scarification, tattoos, and desensitization injections, as well as prior herpes zoster infections.4-9

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations. Lesions can be described as specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions demonstrate the typical sarcoid granuloma on histology and more often are seen in chronic disease, while nonspecific lesions more often are seen in acute disease.3,10 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of a specific lesion in which old scars become infiltrated with noncaseating granulomas. The granulomas typically are in the superficial dermis but may involve the full thickness of the dermis, extending into the subcutaneous tissue.11 The cause of granulomas developing in scars is unknown. Prior contamination of the scar with foreign material, possibly at the time of the trauma, is a possible underlying cause.12

Typical scar sarcoidosis presents as swollen, erythematous, indurated lesions with a purple-red hue that may become brown.3,12 Tenderness or pruritus also may be present.13 Interestingly, our patient's scar sarcoidosis presented with a yellow hue at both mastectomy sites.

Diagnosing scar sarcoidosis can be challenging. Patients are diagnosed with sarcoidosis when a compatible clinical or radiologic picture is present along with histologic evidence of a noncaseating granuloma and other potential causes are excluded.11 The differential includes an infectious etiology, other types of granulomatous dermatitis, hypertrophic scar, keloid, or foreign body granuloma.

Scar sarcoidosis can be isolated in occurrence. It also can precede or occur concomitantly or during a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.10 Most commonly, patients with scar sarcoidosis also have systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, and changing scars may be an indicator of disease exacerbation or relapse.10 For patients who only demonstrate specific skin lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, approximately 30% develop systemic involvement later in life.3 For this reason, close monitoring and regular follow-up are necessary.

Treatment of scar sarcoidosis is dependent on the extent of the disease and presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine phosphate, and methotrexate all have been shown to be helpful in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.3 For scar sarcoidosis that is limited to only the scar site, as seen in our case, monitoring and close follow-up is acceptable. Topical steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. Scar sarcoidosis can resolve slowly and spontaneously over time.10 Our patient notably improved 1 year after the initial presentation without treatment.

Scar sarcoidosis is a well-documented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that can have important implications for diagnosing systemic sarcoidosis. Although there are typical lesions that represent scar sarcoidosis, it is important to have a high degree of suspicion with any changing scar. Once diagnosed through biopsy, a thorough investigation for systemic signs of sarcoidosis needs to be performed to guide treatment.

The Diagnosis: Scar Sarcoidosis

Although scars on both breasts were involved, the decision was made to biopsy the right breast because the patient reported more pain on the left breast. Biopsy showed noncaseating granulomas consistent with scar sarcoidosis (Figure). Additional screening tests were performed to evaluate for any systemic involvement of sarcoidosis, including a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, tuberculosis serology screening, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function tests. She also was referred to rheumatology and ophthalmology for consultation. The results of all screenings were within reference range, and no sign of systemic sarcoidosis was found. She was treated with hydrocortisone ointment 2.5% for several weeks without notable improvement. She elected not to pursue any additional treatment and to monitor the symptoms with close follow-up only. One year after the initial visit, the skin lesions spontaneously and notably improved.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs. It also can involve the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bones, gastrointestinal tract, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous sarcoidosis has been documented in the literature since the late 1800s and occurs in up to one-third of sarcoid patients.1 Cutaneous lesions developing within a preexisting scar is a well-known variant, occurring in 29% of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis in one clinical study (N=818).2 There have been many reports describing scar sarcoidosis, with its development at prior sites of surgery, trauma, acne, or venipuncture.3 Other case reports have described variants of scar sarcoidosis developing at sites of hyaluronic acid injection, laser surgery, ritual scarification, tattoos, and desensitization injections, as well as prior herpes zoster infections.4-9

Cutaneous sarcoidosis has a wide range of clinical presentations. Lesions can be described as specific or nonspecific. Specific lesions demonstrate the typical sarcoid granuloma on histology and more often are seen in chronic disease, while nonspecific lesions more often are seen in acute disease.3,10 Scar sarcoidosis is an example of a specific lesion in which old scars become infiltrated with noncaseating granulomas. The granulomas typically are in the superficial dermis but may involve the full thickness of the dermis, extending into the subcutaneous tissue.11 The cause of granulomas developing in scars is unknown. Prior contamination of the scar with foreign material, possibly at the time of the trauma, is a possible underlying cause.12

Typical scar sarcoidosis presents as swollen, erythematous, indurated lesions with a purple-red hue that may become brown.3,12 Tenderness or pruritus also may be present.13 Interestingly, our patient's scar sarcoidosis presented with a yellow hue at both mastectomy sites.

Diagnosing scar sarcoidosis can be challenging. Patients are diagnosed with sarcoidosis when a compatible clinical or radiologic picture is present along with histologic evidence of a noncaseating granuloma and other potential causes are excluded.11 The differential includes an infectious etiology, other types of granulomatous dermatitis, hypertrophic scar, keloid, or foreign body granuloma.

Scar sarcoidosis can be isolated in occurrence. It also can precede or occur concomitantly or during a relapse of systemic sarcoidosis.10 Most commonly, patients with scar sarcoidosis also have systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis, and changing scars may be an indicator of disease exacerbation or relapse.10 For patients who only demonstrate specific skin lesions of cutaneous sarcoidosis, approximately 30% develop systemic involvement later in life.3 For this reason, close monitoring and regular follow-up are necessary.

Treatment of scar sarcoidosis is dependent on the extent of the disease and presence of systemic sarcoidosis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine phosphate, and methotrexate all have been shown to be helpful in treating cutaneous sarcoidosis.3 For scar sarcoidosis that is limited to only the scar site, as seen in our case, monitoring and close follow-up is acceptable. Topical steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. Scar sarcoidosis can resolve slowly and spontaneously over time.10 Our patient notably improved 1 year after the initial presentation without treatment.

Scar sarcoidosis is a well-documented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that can have important implications for diagnosing systemic sarcoidosis. Although there are typical lesions that represent scar sarcoidosis, it is important to have a high degree of suspicion with any changing scar. Once diagnosed through biopsy, a thorough investigation for systemic signs of sarcoidosis needs to be performed to guide treatment.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888.

- Dal Sacco D, Cozzani E, Parodi A, et al. Scar sarcoidosis after hyaluronic acid injection. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:411-412.

- Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis. 2004;73:53-55.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

- Healsmith MF, Hutchinson PE. The development of scar sarcoidosis at the site of desensitization injections. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:369-370.

- Singal A, Vij A, Pandhi D. Post herpes-zoster scar sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:77-79.

- Chudomirova K, Velichkova L, Anavi B, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:360-361.

- Selim A, Ehrsam E, Atassi MB, et al. Scar sarcoidosis: a case report and brief review. Cutis. 2006;78:418-422.

- Singal A, Thami GP, Goraya JS. Scar sarcoidosis in childhood: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:244-246.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

- Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, et al. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis: relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882-888.

- Dal Sacco D, Cozzani E, Parodi A, et al. Scar sarcoidosis after hyaluronic acid injection. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:411-412.

- Kormeili T, Neel V, Moy RL. Cutaneous sarcoidosis at sites of previous laser surgery. Cutis. 2004;73:53-55.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- James WD, Elston DM, Berger TG, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011.

- Healsmith MF, Hutchinson PE. The development of scar sarcoidosis at the site of desensitization injections. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:369-370.

- Singal A, Vij A, Pandhi D. Post herpes-zoster scar sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:77-79.

- Chudomirova K, Velichkova L, Anavi B, et al. Recurrent sarcoidosis in skin scars accompanying systemic sarcoidosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:360-361.

- Selim A, Ehrsam E, Atassi MB, et al. Scar sarcoidosis: a case report and brief review. Cutis. 2006;78:418-422.

- Singal A, Thami GP, Goraya JS. Scar sarcoidosis in childhood: case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:244-246.

- Marchell RM, Judson MA. Chronic cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:295-302.

A 57-year-old woman with triple-negative ductal breast cancer presented with a mildly pruritic rash on bilateral mastectomy scars of 3 to 4 months' duration. More than a year prior to presentation, she was diagnosed with breast cancer and treated with a bilateral mastectomy and chemotherapy. On physical examination, faintly yellow, slightly indurated, coalescing papules with red rims were present on the bilateral mastectomy scars, with the scar on the left side appearing worse than the right. She previously had not sought treatment.

The h-Index for Associate and Full Professors of Dermatology in the United States: An Epidemiologic Study of Scholastic Production

Academic promotion requires evidence of scholastic production. The number of publications by a scientist is the most frequently reported metric of scholastic production, but it does not account for the impact of publications. The h-index is a bibliometric measure that combines both volume and impact of scientific contributions. The physicist Jorge E. Hirsch introduced this metric in 2005.1 He defined it as the number of publications (h) by an author that have been cited at least h times. For example, a scientist with 30 publications including 12 that have been cited at least 12 times each has an h-index of 12. h-Index is a superior predictor of future scientific achievement in physics compared with total citation count, total publication count, and citations per publication. Hirsch2 proposed h-index thresholds of 12 and 18 for advancement to associate professor and full professor in physics, respectively.2

h-Index values are not comparable across academic disciplines because they are influenced by the number of journals and authors within the field. Scientists in disciplines with numerous scholars and publications will have higher h-indices. For example, the mean h-index for full professors of cardiothoracic anesthesiology is 12, but the mean h-index for full professors of urology is 22.3,4 Hence, h-index thresholds for professional advancement cannot be generalized but must be calculated on a granular, specialty-specific basis.

In a prior study on h-index among academic dermatologists in the United States, John et al5 reported that fellowship-trained dermatologists had a significantly higher mean h-index than those without fellowship training (13.2 vs 11.7; P<.001). They further found the mean h-index increased with academic rank.5

In our study, we measured mean and median h-indices among associate and full professors of dermatology in academic training programs in the United States with the goal of describing h-index distributions in these 2 academic ranks. We further sought to measure regional differences in h-index between northeastern, southern, central, and western states as defined by the National Resident Matching Program.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was deferred because the study did not require patient information or participation. Using the Association of American Medical Colleges Electronic Residency Application Service website (https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/) we identified dermatology residency training programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and participating in the Electronic Residency Application Service for the National Resident Matching Program in the United States. We visited the official website of each residency program and identified all associate and full professors of dermatology for further study. We included all faculty members listed as professor, clinical professor, associate professor, or clinical associate professor, and excluded assistant professor, volunteer faculty, research professor, and research associate professor. All faculty held an MD degree or an equivalent degree, such as MBBS or MDCM.

We used the Thomson Reuters (now Clarivate Analytics) Web of Science to calculate h-index and publication counts. The initial search was basic using the professor’s last name and first initial. We then augmented this list by searching for all variations of each professor’s name, with or without middle initial. Each publication in the search results was confirmed as belonging to the author of interest by verifying coauthors, institution information, and subject material. For authors with common names, we additionally consulted their online university profiles for specific names used in their “Selected Publications” lists. In a minority of cases, we also limited Research Domain to “dermatology.” Referring to the verified publication list for each dermatology professor, we used the Web of Science Citation Report function to determine number of publications and h-index for the individual. We tabulated results for associate and full professors and subgrouped those results into 4 geographic regions—northeastern, southern, central, and western states—according to the map used by the National Resident Matching Program. Descriptive statistics were performed with Microsoft Excel.

Results

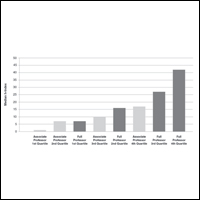

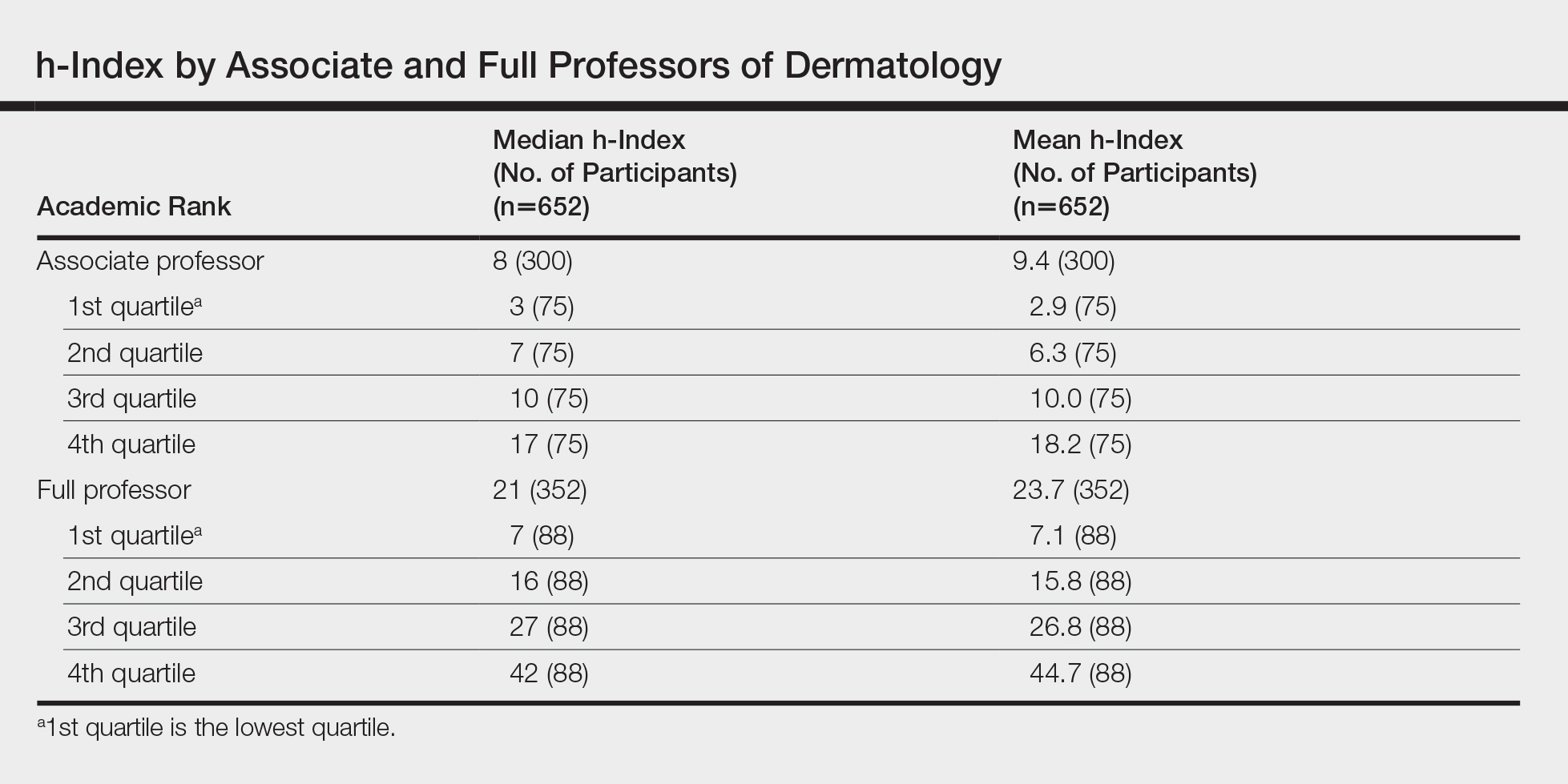

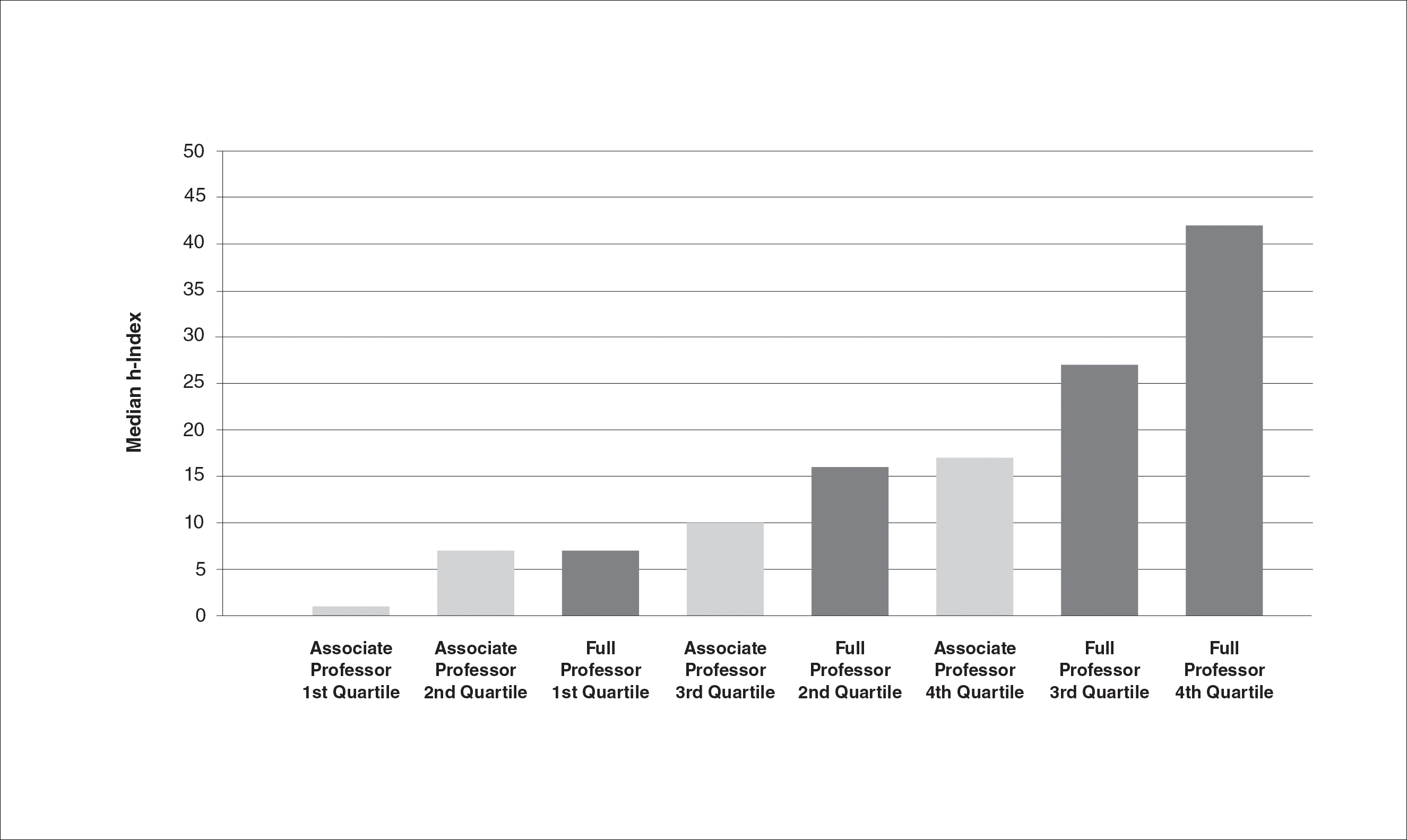

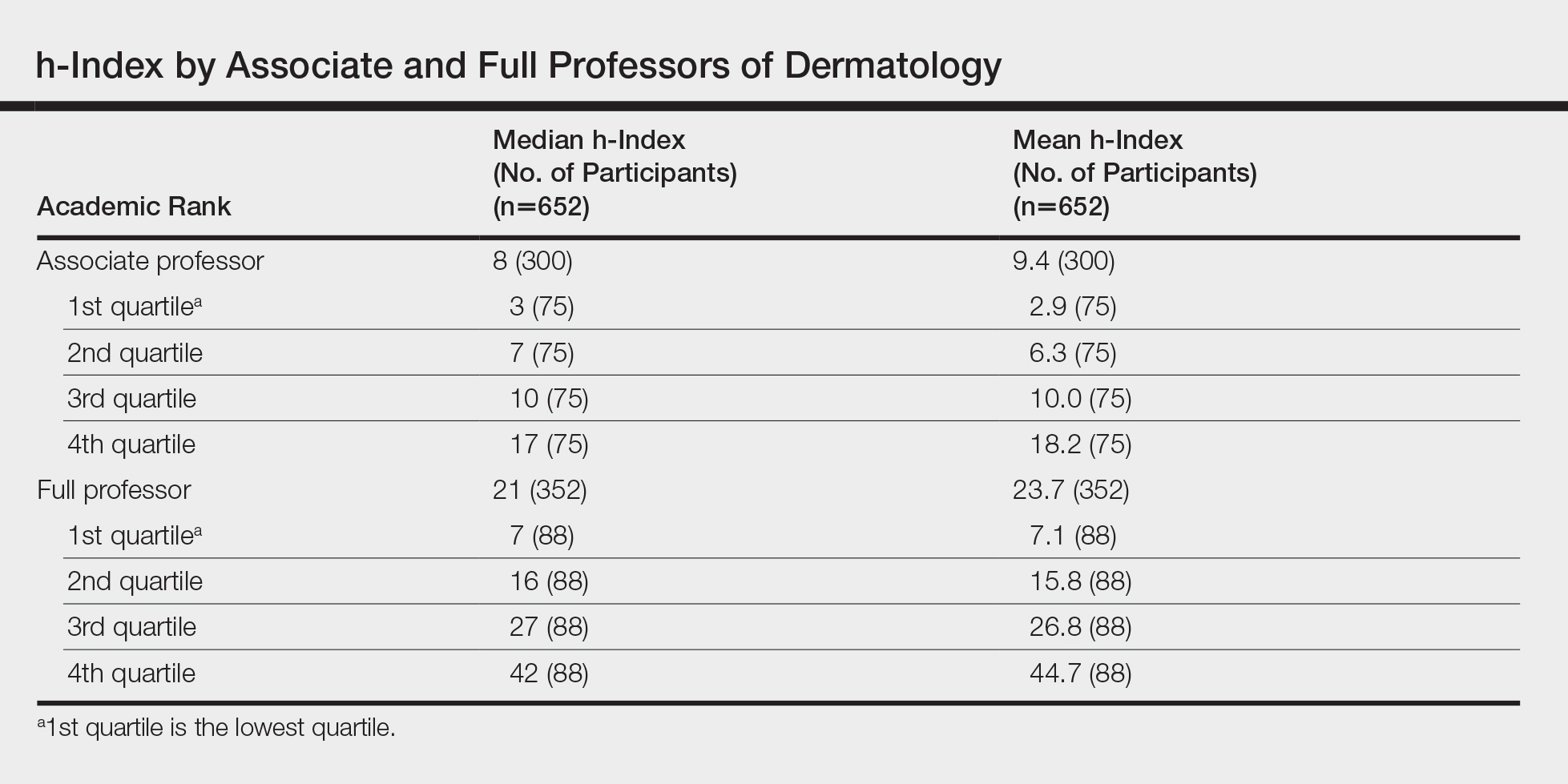

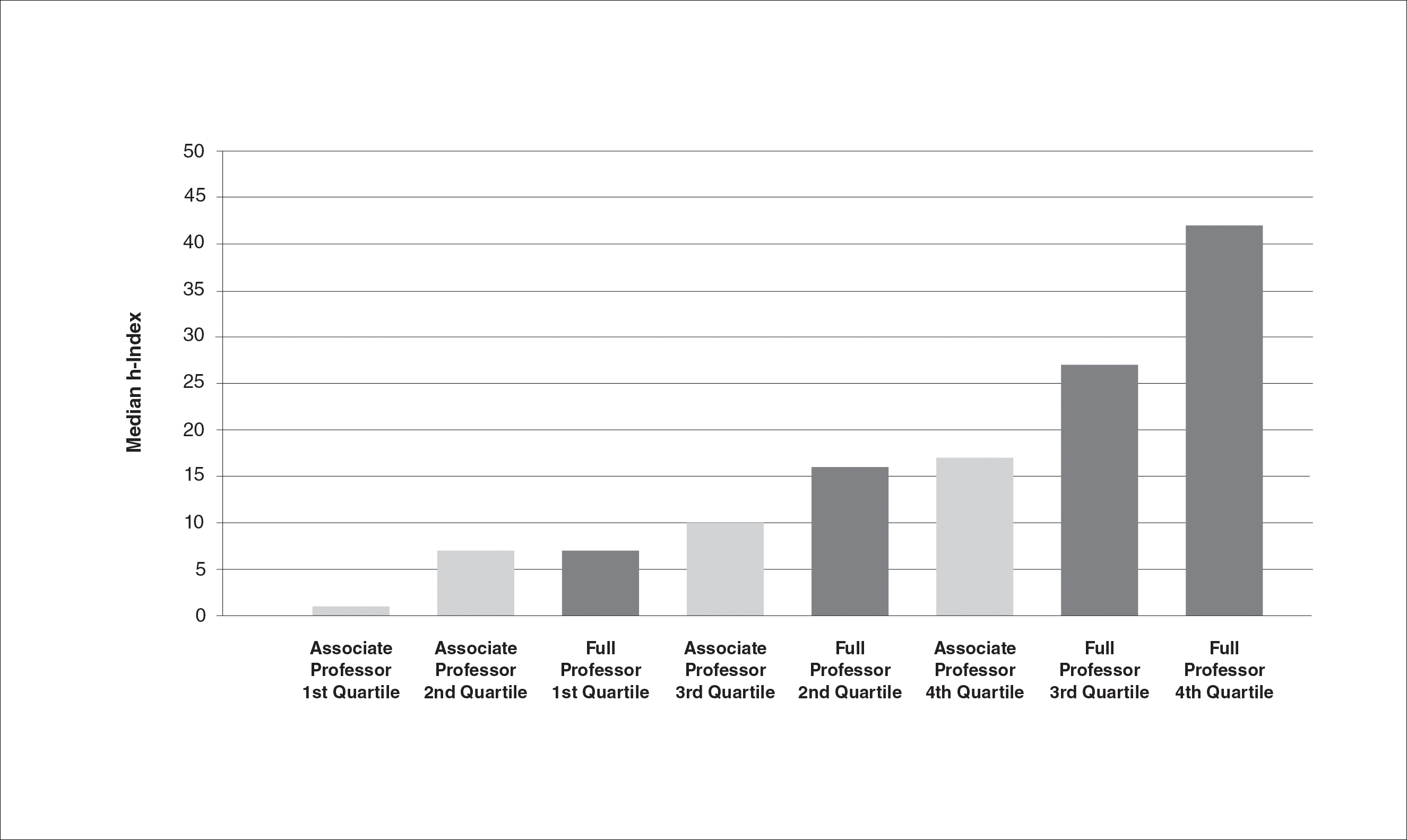

We identified 300 associate professors and 352 full professors from 81 academic institutions. The number of associate professors per institution ranged from 1 to 25; the number of full professors per institution ranged from 1 to 16. The median and mean h-indices for associate and full professors, including interquartile values, are shown in the Table. There was a broad range of h-index scores among both academic ranks; median and mean h-indices varied more than 5-fold between the bottom and upper quartiles in both associate and full professor cohorts. Median interquartile h-index values for upper-quartile associate professors overlapped with those of lower-quartile full professors (Figure 1). h-Index for associate and full professors was similar across the 4 regions defined by the National Resident Matching Program. Median h-index was highest for full professors in western states and lowest for associate professors in southern states (Figure 2).

Comment

Professional advancement in academic medicine requires scholastic production. The h-index, defined as the number of publications (h) that have been cited at least h times, is a bibliometric measure that accounts for both volume and impact of an individual’s scientific productivity. The h-index would be a useful tool for determining professional advancement in academic dermatology departments. In this project, we calculated h-index values for 300 associate professors and 352 full professors of dermatology in the United States. We found the median h-index for associate professors was 8 and the median h-index for full professors was 21. There was more than a 5-fold variation in median and mean h-indices between lower and upper quartiles within both the associate and full professor cohorts. The highest median and mean h-indices were found among full professors of dermatology in western states. These results provide the opportunity for academic dermatologists and institutions to compare their research contributions with peers across the United States.

Our results support those of John et al5 who also found academic rank in dermatology was correlated with h-index. Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar can be used to calculate h-index, but they may return different scores for the same individual.6 John et al5 used the Scopus database to calculate h-index. We used Web of Science because Scopus only includes citations since 1996 and Web of Science was used in the original h-index studies by Hirsch.1,2 Institutions that adopt h-index criteria for advancement and resource distribution decisions should be aware that database selection can affect h-index scores.

Caveats With the h-Index

Flaws in the h-index include inflationary effects of self-citation, time bias, and excessive coauthorship. Individuals can increase their h-index by routinely citing their own publications. However, Engqvist and Frommen7 found tripling self-citations increased the h-index by only 1.

Citations tend to increase with time, and authors who have been active for longer periods will have a higher h-index. It is more difficult for junior faculty to distinguish themselves with the h-index, as it takes time for even the most impactful publications to gain citations. Major scientific papers can take years from conception to publication, and an outstanding paper that is 1 year old would have fewer citations than an equally impactful paper that is 10 years old. To adjust for the effect of time bias, Hirsch2 proposed the m-index, in which the h-index is divided by the years between the author’s first and last publication. He proposed that an m-index of 1 would indicate a successful scientist, 2 an outstanding scientist, and 3 a unique individual.2

The literature is increasingly dominated by teams of coauthors, and the number of coauthors within each team has increased over the last 5 decades.8 h-Indices will increase if this trend continues, making it difficult to compare h-indices between different eras. Prosperi et al9 found national differences in kinship-based coauthorship, suggesting nepotism may influence decisions in assigning authorship status. h-Index valuations do not require evidence of meaningful contribution to the work but simply rely on contributors’ self-governance in assigning authorship status.

The h-index also has a bias against highly cited papers. A scientist with a small number of highly influential papers may have a smaller h-index than a scientist with more papers of modest impact. Finally, an author who has changed names (eg, due to marriage) may have an artificially low h-index, as a standard database search would miss publications under a maiden name.

Limitations

This study is limited by possible operator error when compiling each author’s publication list through Web of Science. Our search and refinement methodology took into account that authors may publish with slight variations in name, in various subject areas and fields, and with different institutions and coauthors. Each publication populated through Web of Science was carefully verified by the principal investigator; however, overestimation or underestimation of the number of publications and citations was possible, as the publication lists were not verified by the studied associate and full professors themselves. Our results are consistent with the h-index bar charts published by John et al5 using an alternate citation index, Scopus, which tends to corroborate our findings. This study also is limited by possible time bias because we did not correct the h-index for years of active publication (m-index).

Conclusion

In summary, we found the median h-index for associate professors was 8 and the median h-index for full professors was 21. We found a broad range of h-index values within each academic rank. h-Index for upper-quartile associate professors overlapped with those of lower-quartile full professors. Our results suggest professional advancement occurs over a broad range of scholastic production. Adopting requirements for minimum h-index thresholds for application for promotion might reduce disparities between rank and scientific contributions. We encourage use of the h-index for tracking academic progression and as a parameter to consider in academic promotion.

- Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16569-16572.

- Hirsch JE. Does the H index have predictive power? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19193-19198.

- Pagel PS, Hudetz JA. Scholarly productivity of United States academic cardiothoracic anesthesiologists: influence of fellowship accreditation and transesophageal echocardiographic credentials on h-index and other citation bibliometrics. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesthesia. 2011;25:761-765.

- Benway BM, Kalidas P, Cabello JM, et al. Does citation analysis reveal association between h-index and academic rank in urology? Urology. 2009;74:30-33.

- John AM, Gupta AB, John ES, et al. The impact of fellowship training on scholarly productivity in academic dermatology. Cutis. 2016;97:353-358.

- Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I, et al. Comparisons of citations in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302:1092-1096.

- Engqvist L, Frommen JG. The h-index and self-citations. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:250-252.

- Wuchty S, Jones BF, Uzzi B. The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science. 2007;316:1036-1039.

- Prosperi M, Buchan I, Fanti I, et al. Kin of coauthorship in five decades of health science literature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:8957-8962.

Academic promotion requires evidence of scholastic production. The number of publications by a scientist is the most frequently reported metric of scholastic production, but it does not account for the impact of publications. The h-index is a bibliometric measure that combines both volume and impact of scientific contributions. The physicist Jorge E. Hirsch introduced this metric in 2005.1 He defined it as the number of publications (h) by an author that have been cited at least h times. For example, a scientist with 30 publications including 12 that have been cited at least 12 times each has an h-index of 12. h-Index is a superior predictor of future scientific achievement in physics compared with total citation count, total publication count, and citations per publication. Hirsch2 proposed h-index thresholds of 12 and 18 for advancement to associate professor and full professor in physics, respectively.2

h-Index values are not comparable across academic disciplines because they are influenced by the number of journals and authors within the field. Scientists in disciplines with numerous scholars and publications will have higher h-indices. For example, the mean h-index for full professors of cardiothoracic anesthesiology is 12, but the mean h-index for full professors of urology is 22.3,4 Hence, h-index thresholds for professional advancement cannot be generalized but must be calculated on a granular, specialty-specific basis.

In a prior study on h-index among academic dermatologists in the United States, John et al5 reported that fellowship-trained dermatologists had a significantly higher mean h-index than those without fellowship training (13.2 vs 11.7; P<.001). They further found the mean h-index increased with academic rank.5

In our study, we measured mean and median h-indices among associate and full professors of dermatology in academic training programs in the United States with the goal of describing h-index distributions in these 2 academic ranks. We further sought to measure regional differences in h-index between northeastern, southern, central, and western states as defined by the National Resident Matching Program.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was deferred because the study did not require patient information or participation. Using the Association of American Medical Colleges Electronic Residency Application Service website (https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/) we identified dermatology residency training programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and participating in the Electronic Residency Application Service for the National Resident Matching Program in the United States. We visited the official website of each residency program and identified all associate and full professors of dermatology for further study. We included all faculty members listed as professor, clinical professor, associate professor, or clinical associate professor, and excluded assistant professor, volunteer faculty, research professor, and research associate professor. All faculty held an MD degree or an equivalent degree, such as MBBS or MDCM.

We used the Thomson Reuters (now Clarivate Analytics) Web of Science to calculate h-index and publication counts. The initial search was basic using the professor’s last name and first initial. We then augmented this list by searching for all variations of each professor’s name, with or without middle initial. Each publication in the search results was confirmed as belonging to the author of interest by verifying coauthors, institution information, and subject material. For authors with common names, we additionally consulted their online university profiles for specific names used in their “Selected Publications” lists. In a minority of cases, we also limited Research Domain to “dermatology.” Referring to the verified publication list for each dermatology professor, we used the Web of Science Citation Report function to determine number of publications and h-index for the individual. We tabulated results for associate and full professors and subgrouped those results into 4 geographic regions—northeastern, southern, central, and western states—according to the map used by the National Resident Matching Program. Descriptive statistics were performed with Microsoft Excel.

Results

We identified 300 associate professors and 352 full professors from 81 academic institutions. The number of associate professors per institution ranged from 1 to 25; the number of full professors per institution ranged from 1 to 16. The median and mean h-indices for associate and full professors, including interquartile values, are shown in the Table. There was a broad range of h-index scores among both academic ranks; median and mean h-indices varied more than 5-fold between the bottom and upper quartiles in both associate and full professor cohorts. Median interquartile h-index values for upper-quartile associate professors overlapped with those of lower-quartile full professors (Figure 1). h-Index for associate and full professors was similar across the 4 regions defined by the National Resident Matching Program. Median h-index was highest for full professors in western states and lowest for associate professors in southern states (Figure 2).

Comment

Professional advancement in academic medicine requires scholastic production. The h-index, defined as the number of publications (h) that have been cited at least h times, is a bibliometric measure that accounts for both volume and impact of an individual’s scientific productivity. The h-index would be a useful tool for determining professional advancement in academic dermatology departments. In this project, we calculated h-index values for 300 associate professors and 352 full professors of dermatology in the United States. We found the median h-index for associate professors was 8 and the median h-index for full professors was 21. There was more than a 5-fold variation in median and mean h-indices between lower and upper quartiles within both the associate and full professor cohorts. The highest median and mean h-indices were found among full professors of dermatology in western states. These results provide the opportunity for academic dermatologists and institutions to compare their research contributions with peers across the United States.

Our results support those of John et al5 who also found academic rank in dermatology was correlated with h-index. Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar can be used to calculate h-index, but they may return different scores for the same individual.6 John et al5 used the Scopus database to calculate h-index. We used Web of Science because Scopus only includes citations since 1996 and Web of Science was used in the original h-index studies by Hirsch.1,2 Institutions that adopt h-index criteria for advancement and resource distribution decisions should be aware that database selection can affect h-index scores.

Caveats With the h-Index

Flaws in the h-index include inflationary effects of self-citation, time bias, and excessive coauthorship. Individuals can increase their h-index by routinely citing their own publications. However, Engqvist and Frommen7 found tripling self-citations increased the h-index by only 1.

Citations tend to increase with time, and authors who have been active for longer periods will have a higher h-index. It is more difficult for junior faculty to distinguish themselves with the h-index, as it takes time for even the most impactful publications to gain citations. Major scientific papers can take years from conception to publication, and an outstanding paper that is 1 year old would have fewer citations than an equally impactful paper that is 10 years old. To adjust for the effect of time bias, Hirsch2 proposed the m-index, in which the h-index is divided by the years between the author’s first and last publication. He proposed that an m-index of 1 would indicate a successful scientist, 2 an outstanding scientist, and 3 a unique individual.2

The literature is increasingly dominated by teams of coauthors, and the number of coauthors within each team has increased over the last 5 decades.8 h-Indices will increase if this trend continues, making it difficult to compare h-indices between different eras. Prosperi et al9 found national differences in kinship-based coauthorship, suggesting nepotism may influence decisions in assigning authorship status. h-Index valuations do not require evidence of meaningful contribution to the work but simply rely on contributors’ self-governance in assigning authorship status.

The h-index also has a bias against highly cited papers. A scientist with a small number of highly influential papers may have a smaller h-index than a scientist with more papers of modest impact. Finally, an author who has changed names (eg, due to marriage) may have an artificially low h-index, as a standard database search would miss publications under a maiden name.

Limitations

This study is limited by possible operator error when compiling each author’s publication list through Web of Science. Our search and refinement methodology took into account that authors may publish with slight variations in name, in various subject areas and fields, and with different institutions and coauthors. Each publication populated through Web of Science was carefully verified by the principal investigator; however, overestimation or underestimation of the number of publications and citations was possible, as the publication lists were not verified by the studied associate and full professors themselves. Our results are consistent with the h-index bar charts published by John et al5 using an alternate citation index, Scopus, which tends to corroborate our findings. This study also is limited by possible time bias because we did not correct the h-index for years of active publication (m-index).

Conclusion

In summary, we found the median h-index for associate professors was 8 and the median h-index for full professors was 21. We found a broad range of h-index values within each academic rank. h-Index for upper-quartile associate professors overlapped with those of lower-quartile full professors. Our results suggest professional advancement occurs over a broad range of scholastic production. Adopting requirements for minimum h-index thresholds for application for promotion might reduce disparities between rank and scientific contributions. We encourage use of the h-index for tracking academic progression and as a parameter to consider in academic promotion.

Academic promotion requires evidence of scholastic production. The number of publications by a scientist is the most frequently reported metric of scholastic production, but it does not account for the impact of publications. The h-index is a bibliometric measure that combines both volume and impact of scientific contributions. The physicist Jorge E. Hirsch introduced this metric in 2005.1 He defined it as the number of publications (h) by an author that have been cited at least h times. For example, a scientist with 30 publications including 12 that have been cited at least 12 times each has an h-index of 12. h-Index is a superior predictor of future scientific achievement in physics compared with total citation count, total publication count, and citations per publication. Hirsch2 proposed h-index thresholds of 12 and 18 for advancement to associate professor and full professor in physics, respectively.2

h-Index values are not comparable across academic disciplines because they are influenced by the number of journals and authors within the field. Scientists in disciplines with numerous scholars and publications will have higher h-indices. For example, the mean h-index for full professors of cardiothoracic anesthesiology is 12, but the mean h-index for full professors of urology is 22.3,4 Hence, h-index thresholds for professional advancement cannot be generalized but must be calculated on a granular, specialty-specific basis.

In a prior study on h-index among academic dermatologists in the United States, John et al5 reported that fellowship-trained dermatologists had a significantly higher mean h-index than those without fellowship training (13.2 vs 11.7; P<.001). They further found the mean h-index increased with academic rank.5

In our study, we measured mean and median h-indices among associate and full professors of dermatology in academic training programs in the United States with the goal of describing h-index distributions in these 2 academic ranks. We further sought to measure regional differences in h-index between northeastern, southern, central, and western states as defined by the National Resident Matching Program.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was deferred because the study did not require patient information or participation. Using the Association of American Medical Colleges Electronic Residency Application Service website (https://www.aamc.org/services/eras/) we identified dermatology residency training programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and participating in the Electronic Residency Application Service for the National Resident Matching Program in the United States. We visited the official website of each residency program and identified all associate and full professors of dermatology for further study. We included all faculty members listed as professor, clinical professor, associate professor, or clinical associate professor, and excluded assistant professor, volunteer faculty, research professor, and research associate professor. All faculty held an MD degree or an equivalent degree, such as MBBS or MDCM.

We used the Thomson Reuters (now Clarivate Analytics) Web of Science to calculate h-index and publication counts. The initial search was basic using the professor’s last name and first initial. We then augmented this list by searching for all variations of each professor’s name, with or without middle initial. Each publication in the search results was confirmed as belonging to the author of interest by verifying coauthors, institution information, and subject material. For authors with common names, we additionally consulted their online university profiles for specific names used in their “Selected Publications” lists. In a minority of cases, we also limited Research Domain to “dermatology.” Referring to the verified publication list for each dermatology professor, we used the Web of Science Citation Report function to determine number of publications and h-index for the individual. We tabulated results for associate and full professors and subgrouped those results into 4 geographic regions—northeastern, southern, central, and western states—according to the map used by the National Resident Matching Program. Descriptive statistics were performed with Microsoft Excel.

Results

We identified 300 associate professors and 352 full professors from 81 academic institutions. The number of associate professors per institution ranged from 1 to 25; the number of full professors per institution ranged from 1 to 16. The median and mean h-indices for associate and full professors, including interquartile values, are shown in the Table. There was a broad range of h-index scores among both academic ranks; median and mean h-indices varied more than 5-fold between the bottom and upper quartiles in both associate and full professor cohorts. Median interquartile h-index values for upper-quartile associate professors overlapped with those of lower-quartile full professors (Figure 1). h-Index for associate and full professors was similar across the 4 regions defined by the National Resident Matching Program. Median h-index was highest for full professors in western states and lowest for associate professors in southern states (Figure 2).

Comment

Professional advancement in academic medicine requires scholastic production. The h-index, defined as the number of publications (h) that have been cited at least h times, is a bibliometric measure that accounts for both volume and impact of an individual’s scientific productivity. The h-index would be a useful tool for determining professional advancement in academic dermatology departments. In this project, we calculated h-index values for 300 associate professors and 352 full professors of dermatology in the United States. We found the median h-index for associate professors was 8 and the median h-index for full professors was 21. There was more than a 5-fold variation in median and mean h-indices between lower and upper quartiles within both the associate and full professor cohorts. The highest median and mean h-indices were found among full professors of dermatology in western states. These results provide the opportunity for academic dermatologists and institutions to compare their research contributions with peers across the United States.

Our results support those of John et al5 who also found academic rank in dermatology was correlated with h-index. Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar can be used to calculate h-index, but they may return different scores for the same individual.6 John et al5 used the Scopus database to calculate h-index. We used Web of Science because Scopus only includes citations since 1996 and Web of Science was used in the original h-index studies by Hirsch.1,2 Institutions that adopt h-index criteria for advancement and resource distribution decisions should be aware that database selection can affect h-index scores.

Caveats With the h-Index

Flaws in the h-index include inflationary effects of self-citation, time bias, and excessive coauthorship. Individuals can increase their h-index by routinely citing their own publications. However, Engqvist and Frommen7 found tripling self-citations increased the h-index by only 1.

Citations tend to increase with time, and authors who have been active for longer periods will have a higher h-index. It is more difficult for junior faculty to distinguish themselves with the h-index, as it takes time for even the most impactful publications to gain citations. Major scientific papers can take years from conception to publication, and an outstanding paper that is 1 year old would have fewer citations than an equally impactful paper that is 10 years old. To adjust for the effect of time bias, Hirsch2 proposed the m-index, in which the h-index is divided by the years between the author’s first and last publication. He proposed that an m-index of 1 would indicate a successful scientist, 2 an outstanding scientist, and 3 a unique individual.2

The literature is increasingly dominated by teams of coauthors, and the number of coauthors within each team has increased over the last 5 decades.8 h-Indices will increase if this trend continues, making it difficult to compare h-indices between different eras. Prosperi et al9 found national differences in kinship-based coauthorship, suggesting nepotism may influence decisions in assigning authorship status. h-Index valuations do not require evidence of meaningful contribution to the work but simply rely on contributors’ self-governance in assigning authorship status.

The h-index also has a bias against highly cited papers. A scientist with a small number of highly influential papers may have a smaller h-index than a scientist with more papers of modest impact. Finally, an author who has changed names (eg, due to marriage) may have an artificially low h-index, as a standard database search would miss publications under a maiden name.

Limitations

This study is limited by possible operator error when compiling each author’s publication list through Web of Science. Our search and refinement methodology took into account that authors may publish with slight variations in name, in various subject areas and fields, and with different institutions and coauthors. Each publication populated through Web of Science was carefully verified by the principal investigator; however, overestimation or underestimation of the number of publications and citations was possible, as the publication lists were not verified by the studied associate and full professors themselves. Our results are consistent with the h-index bar charts published by John et al5 using an alternate citation index, Scopus, which tends to corroborate our findings. This study also is limited by possible time bias because we did not correct the h-index for years of active publication (m-index).

Conclusion

In summary, we found the median h-index for associate professors was 8 and the median h-index for full professors was 21. We found a broad range of h-index values within each academic rank. h-Index for upper-quartile associate professors overlapped with those of lower-quartile full professors. Our results suggest professional advancement occurs over a broad range of scholastic production. Adopting requirements for minimum h-index thresholds for application for promotion might reduce disparities between rank and scientific contributions. We encourage use of the h-index for tracking academic progression and as a parameter to consider in academic promotion.

- Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16569-16572.

- Hirsch JE. Does the H index have predictive power? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19193-19198.

- Pagel PS, Hudetz JA. Scholarly productivity of United States academic cardiothoracic anesthesiologists: influence of fellowship accreditation and transesophageal echocardiographic credentials on h-index and other citation bibliometrics. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesthesia. 2011;25:761-765.

- Benway BM, Kalidas P, Cabello JM, et al. Does citation analysis reveal association between h-index and academic rank in urology? Urology. 2009;74:30-33.

- John AM, Gupta AB, John ES, et al. The impact of fellowship training on scholarly productivity in academic dermatology. Cutis. 2016;97:353-358.

- Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I, et al. Comparisons of citations in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302:1092-1096.

- Engqvist L, Frommen JG. The h-index and self-citations. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:250-252.

- Wuchty S, Jones BF, Uzzi B. The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science. 2007;316:1036-1039.

- Prosperi M, Buchan I, Fanti I, et al. Kin of coauthorship in five decades of health science literature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:8957-8962.

- Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16569-16572.

- Hirsch JE. Does the H index have predictive power? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19193-19198.

- Pagel PS, Hudetz JA. Scholarly productivity of United States academic cardiothoracic anesthesiologists: influence of fellowship accreditation and transesophageal echocardiographic credentials on h-index and other citation bibliometrics. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesthesia. 2011;25:761-765.

- Benway BM, Kalidas P, Cabello JM, et al. Does citation analysis reveal association between h-index and academic rank in urology? Urology. 2009;74:30-33.

- John AM, Gupta AB, John ES, et al. The impact of fellowship training on scholarly productivity in academic dermatology. Cutis. 2016;97:353-358.

- Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I, et al. Comparisons of citations in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA. 2009;302:1092-1096.

- Engqvist L, Frommen JG. The h-index and self-citations. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23:250-252.

- Wuchty S, Jones BF, Uzzi B. The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science. 2007;316:1036-1039.

- Prosperi M, Buchan I, Fanti I, et al. Kin of coauthorship in five decades of health science literature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:8957-8962.

Practice Points

- Promotion in academic dermatology requires evidence of scholastic production. The h-index is a bibliometric measure that combines both volume and impact of scientific contributions.

- Our study’s findings provide data-driven parameters to consider in academic promotion.

- Institutions that adopt h-index criteria for advancement and resource distribution decisions should be aware that database selection can affect h-index scores.

Recalcitrant Solitary Erythematous Scaly Patch on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

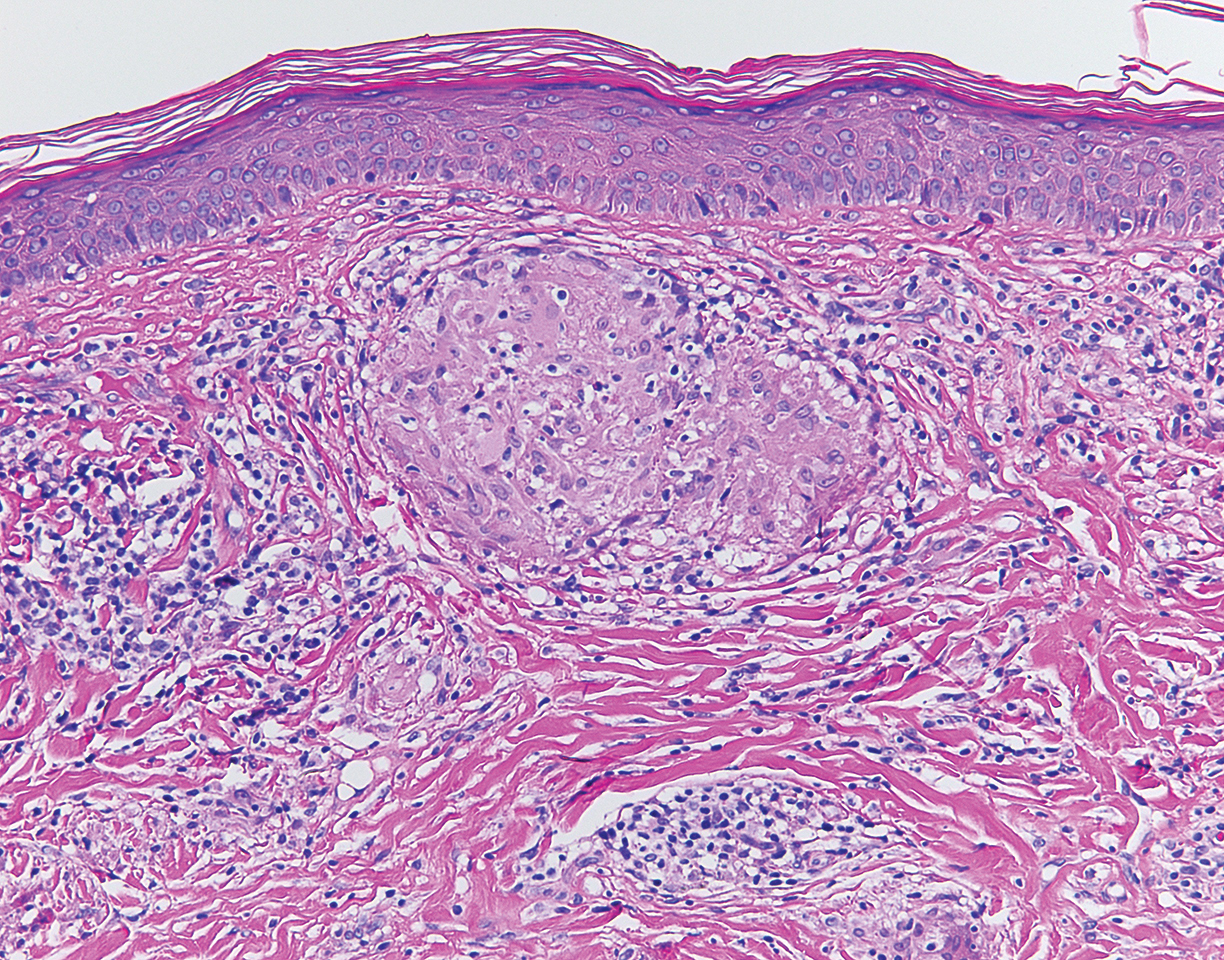

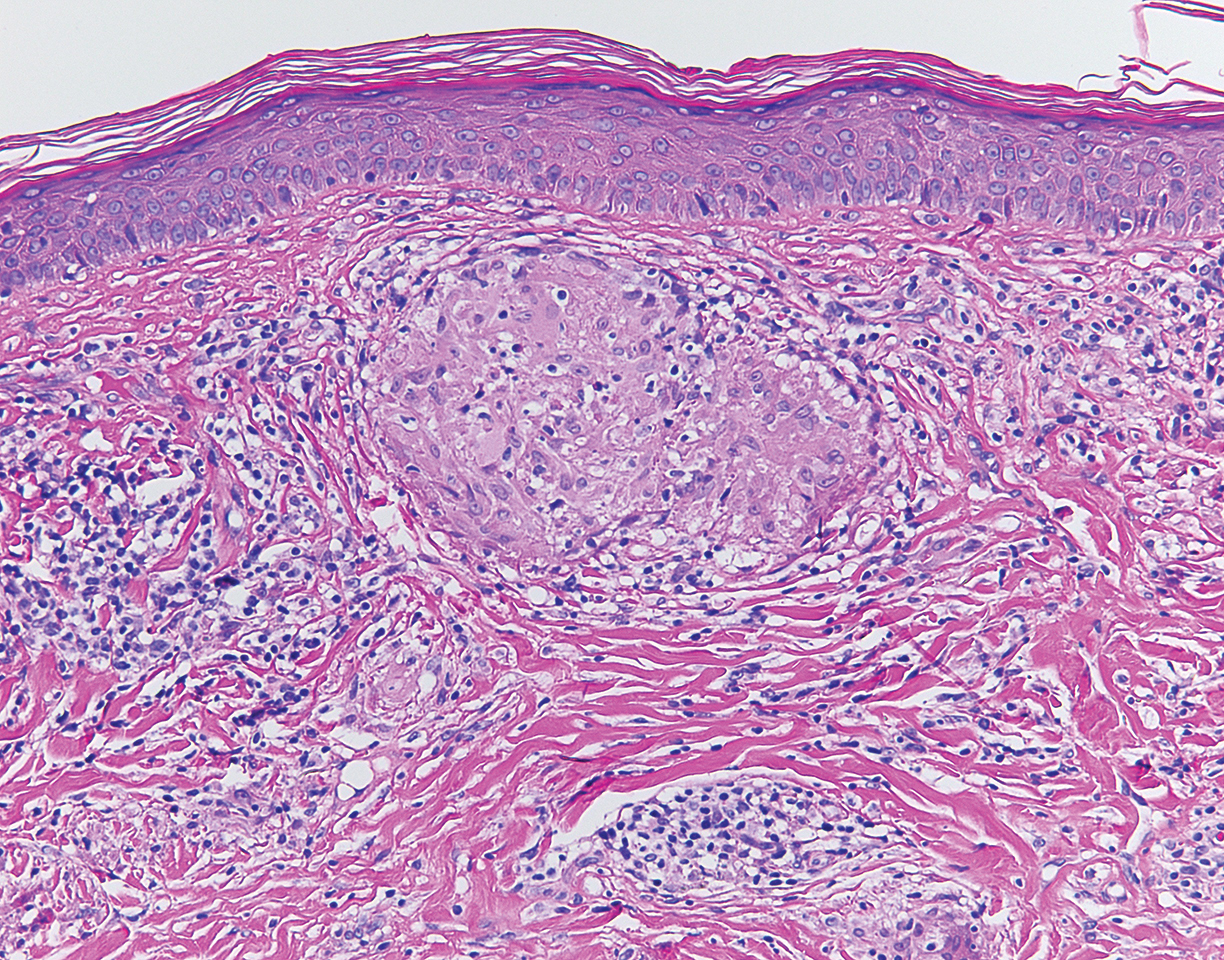

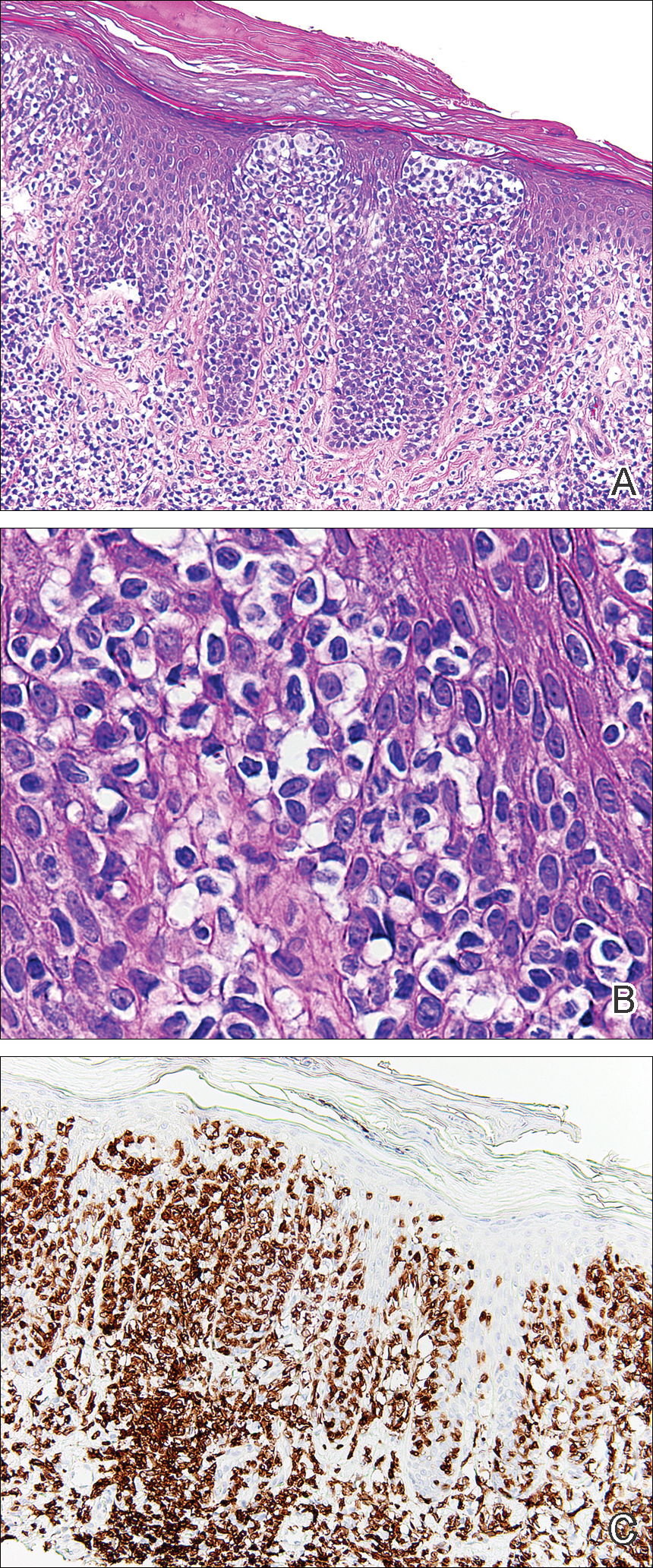

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

An 80-year-old man with a history of malignant melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma presented to the dermatology clinic with a chronic rash of 20 years' duration on the right ankle that extended to the instep of the right foot. His medical history was notable for hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Family history was unremarkable. The patient described the rash as red and scaly but denied associated pain or pruritus. Over the last 2 to 3 years he had tried treating the affected area with petroleum jelly, topical and oral antifungals, and mild topical steroids with minimal improvement. Complete review of systems was performed and was negative other than some mild constipation. Physical examination revealed an erythematous scaly patch on the dorsal aspect of the right ankle. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal culture swab yielded negative results, and a shave biopsy was performed.