User login

Large Indurated Plaque on the Chest With Ulceration and Necrosis

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

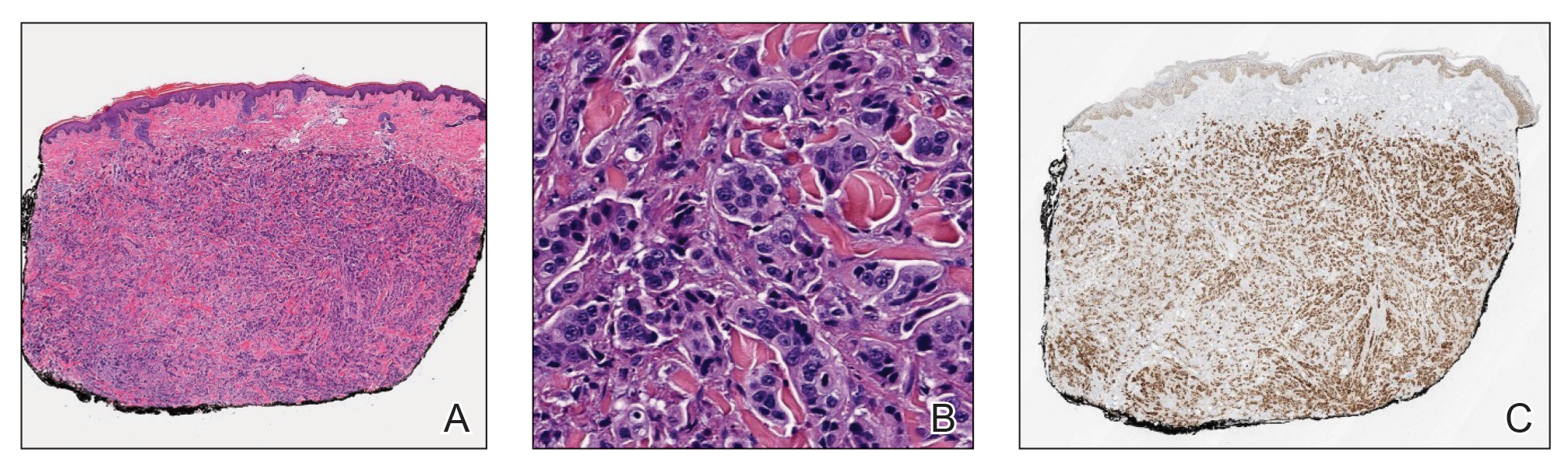

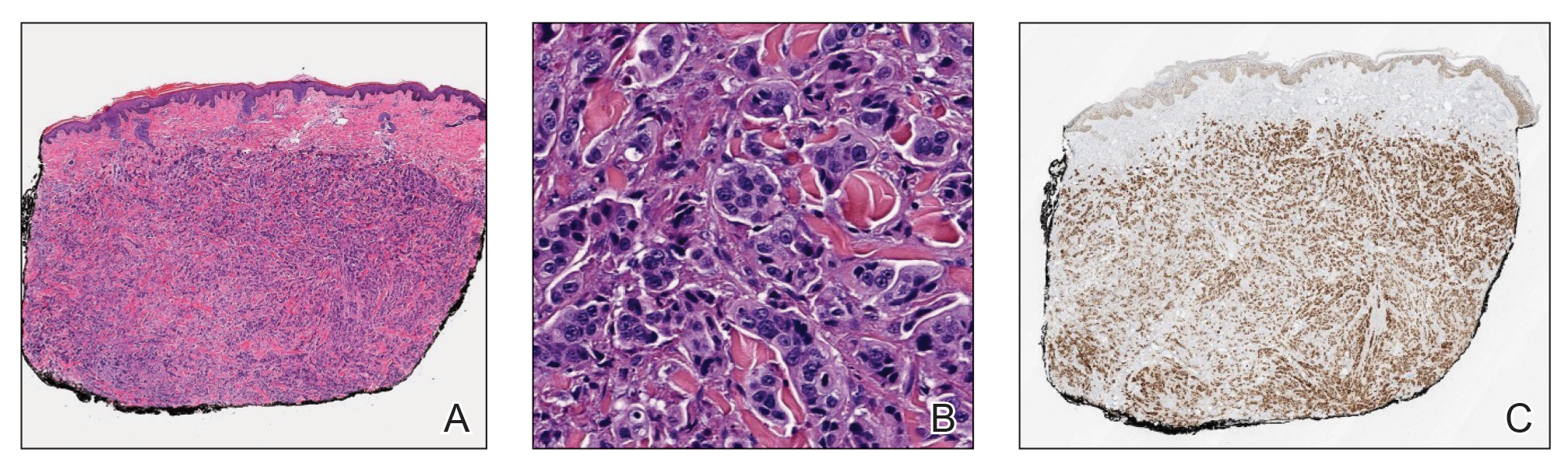

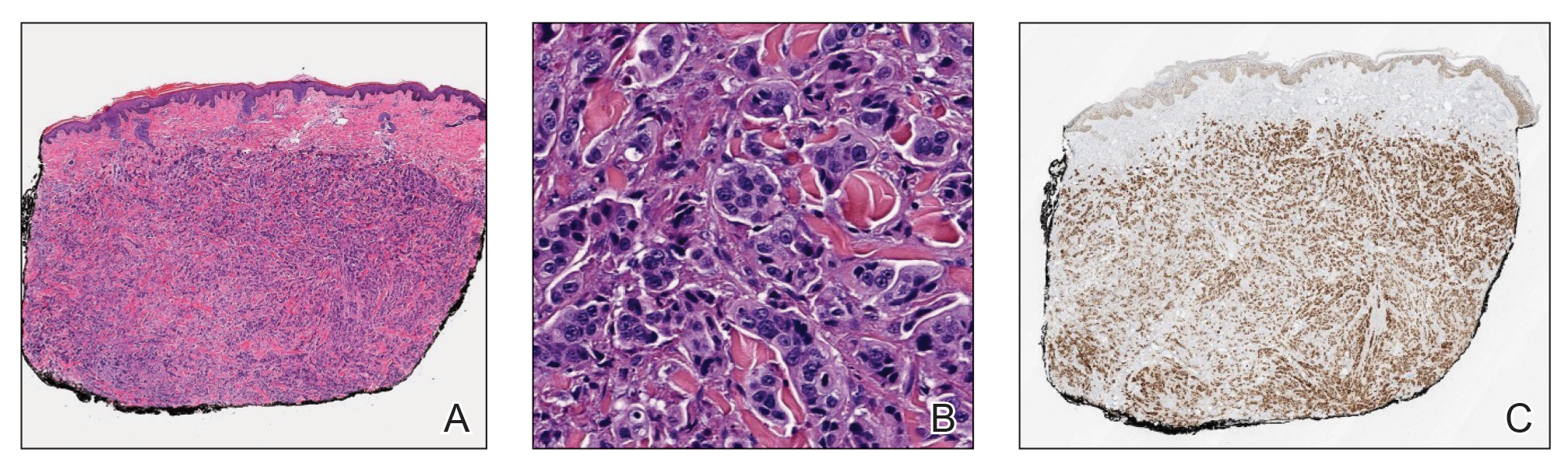

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

A 47-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath on simple exertion as well as a large lesion on the chest that had slowly increased in size over the last 3 years. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and she had been treating it with topical emollients without substantial improvement. Physical examination revealed a large indurated plaque with areas of ulceration and necrosis spanning the mid to lateral chest. Additionally, ichthyotic brown scaling was present on the arms and legs. Upon further questioning, the patient reported that the scales on the extremities appeared in the last 3 months and were not previously noted. She had no recent routine cancer screenings, and her family history was notable for a brother with brain cancer. A punch biopsy of the chest plaque was performed.