User login

Large Indurated Plaque on the Chest With Ulceration and Necrosis

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

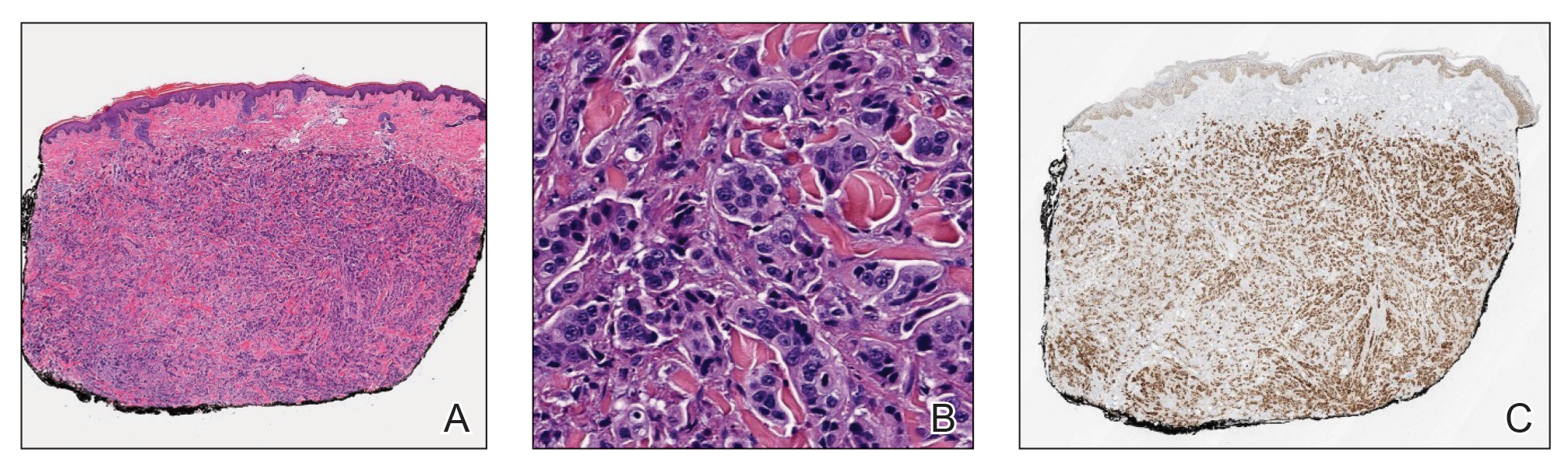

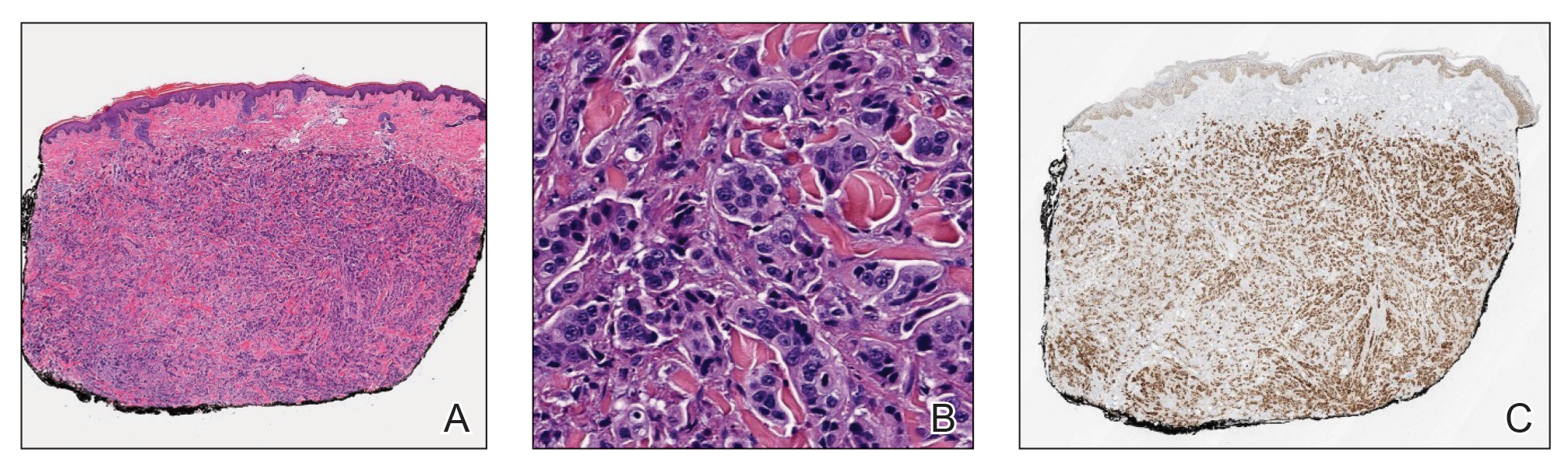

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

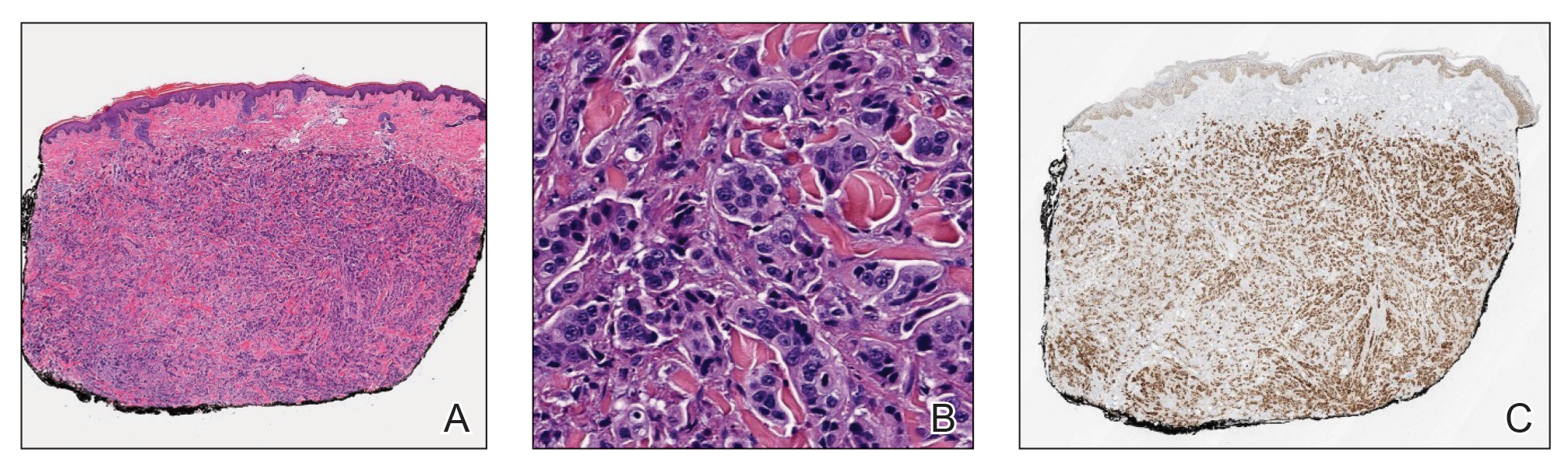

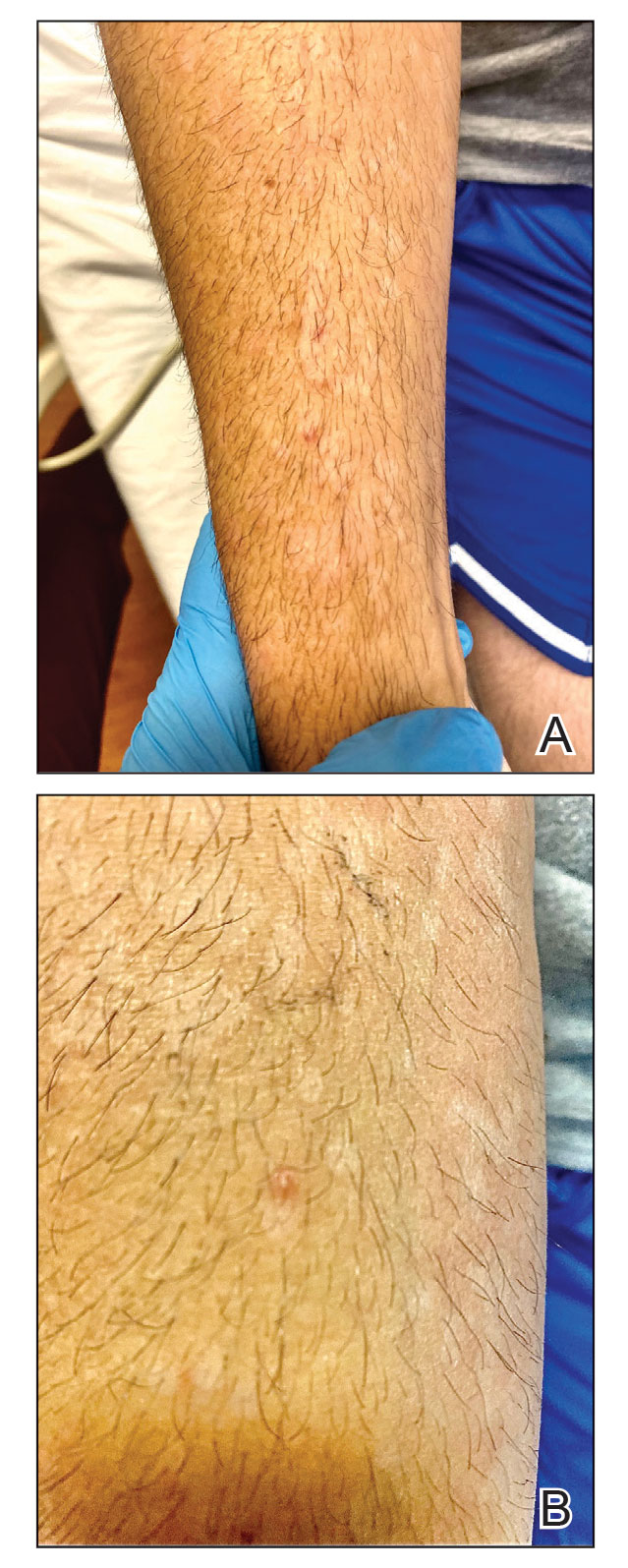

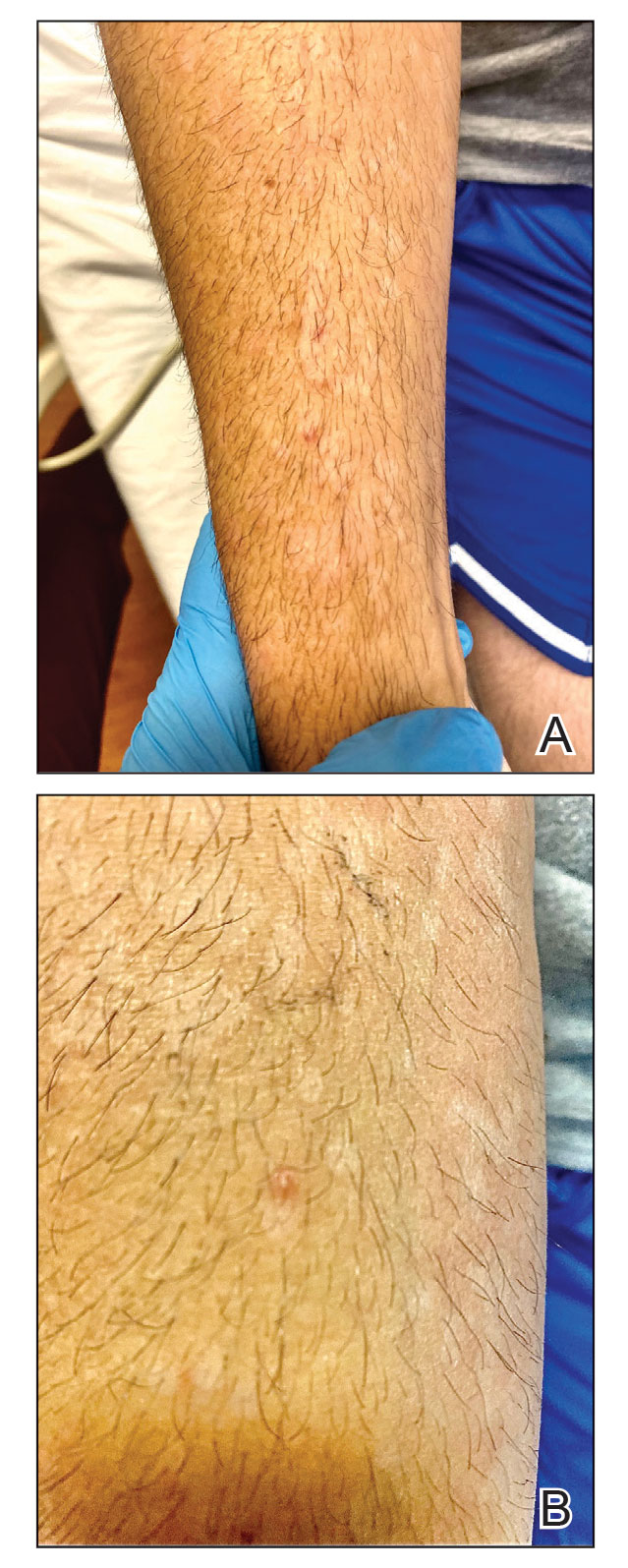

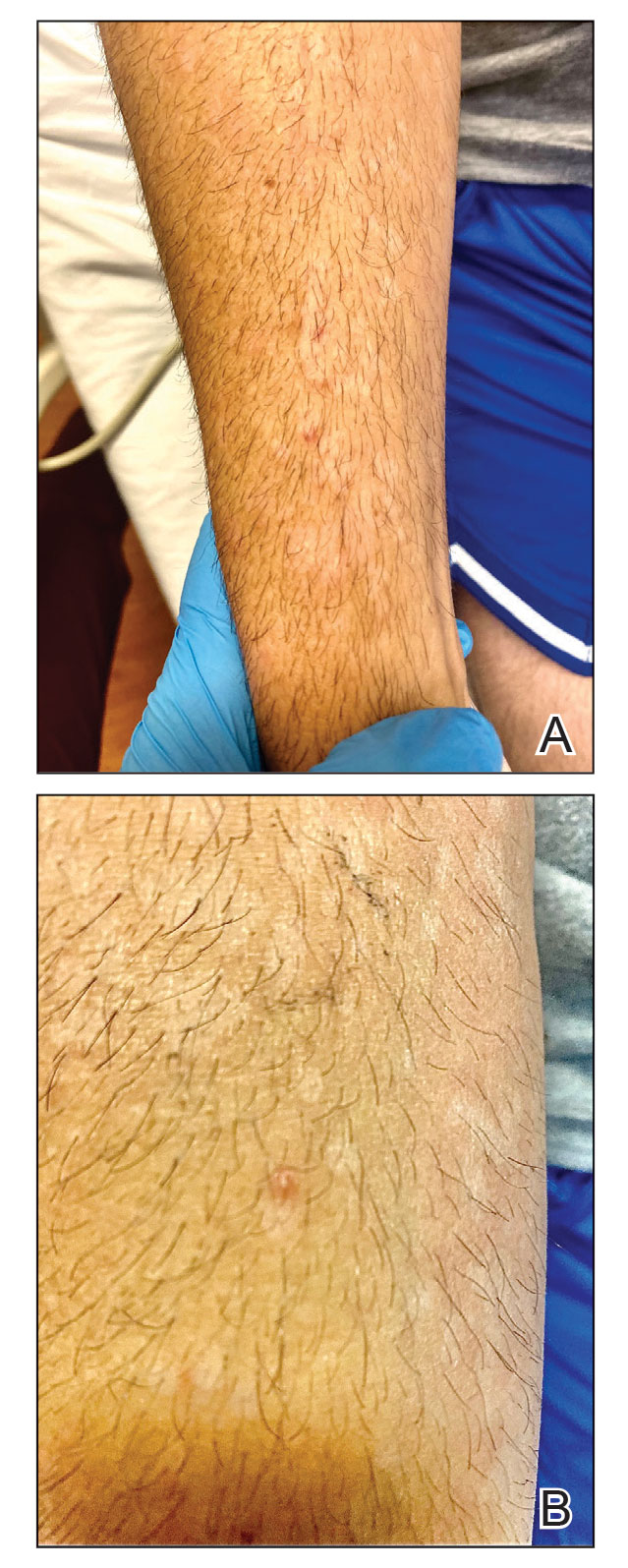

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

A 47-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath on simple exertion as well as a large lesion on the chest that had slowly increased in size over the last 3 years. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and she had been treating it with topical emollients without substantial improvement. Physical examination revealed a large indurated plaque with areas of ulceration and necrosis spanning the mid to lateral chest. Additionally, ichthyotic brown scaling was present on the arms and legs. Upon further questioning, the patient reported that the scales on the extremities appeared in the last 3 months and were not previously noted. She had no recent routine cancer screenings, and her family history was notable for a brother with brain cancer. A punch biopsy of the chest plaque was performed.

Genital Ulcerations With Swelling

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

The Diagnosis: Mpox (Monkeypox)

Tests for active herpes simplex virus (HHV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis were negative. Swabs from the penile lesion demonstrated positivity for the West African clade of mpox (monkeypox) virus (MPXV) by polymerase chain reaction. The patient was treated supportively without the addition of antiviral therapy, and he experienced a complete recovery.

Mpox virus was first isolated in 1958 in a research facility and was named after the laboratory animals that were housed there. The first human documentation of the disease occurred in 1970, and it was first documented in the United States in 2003 in an infection that was traced to a shipment of small mammals from Ghana to Texas.1 The disease has always been endemic to Africa; however, the incidence has been increasing.2 A new MPXV outbreak was reported in many countries in early 2022, including the United States.1

The MPXV is a double-stranded DNA virus of the genus Orthopoxvirus, and 2 genetic clades have been identified: clade I (formerly the Central African clade) and clade II (formerly the West African clade). The virus has the capability to infect many mammals; however, its host remains unidentified.1 The exact mechanism of transmission from infected animals to humans largely is unknown; however, direct or indirect contact with infected animals likely is responsible. Human-to-human transmission can occur by many mechanisms including contact with large respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, and contaminated surfaces. The incubation period is 5 to 21 days, and the symptoms last 2 to 5 weeks.1

The clinical manifestations of MPXV during the most recent outbreak differ from prior outbreaks. Patients are more likely to experience minimal to no systemic symptoms, and cutaneous lesions can be few and localized to a focal area, especially on the face and in the anogenital region,3 similar to the presentation in our patient (Figure 1). Cutaneous lesions of the most recent MPXV outbreak also include painless ulcerations similar to syphilitic chancres and lesions that are in various stages of healing.3 Lesions often begin as pseudopustules, which are firm white papules with or without a necrotic center that resemble pustules; unlike true pustules, there is no identifiable purulent material within it. Bacterial superinfection of the lesions is not uncommon.4 Over time, a secondary pustular eruption resembling folliculitis also may occur,4 as noted in our patient (Figure 2).

Although we did not have a biopsy to support the diagnosis of associated erythema multiforme (EM) in our patient, features supportive of this diagnosis included the classic clinical appearance of typical, well-defined, targetoid plaques with 3 distinct zones (Figure 3); the association with a known infection; the distribution on the arms with truncal sparing; and self-limited lesions. More than 90% of EM cases are associated with infection, with HHV representing the most common culprit5; therefore, the relationship with a different virus is not an unreasonable suggestion. Additionally, there have been rare reports of EM in association with MPXV.4

Histopathology of MPXV may have distinctive features. Lesions often demonstrate keratinocytic necrosis and basal layer vacuolization with an associated superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. When the morphology of the lesion is vesicular, histopathology reveals spongiosis and ballooning degeneration with epidermal necrosis. Viral inclusion bodies within keratinocytes may be identified.1 Death rates from MPXV has been reported from 1% to 11%, with increased mortality among high-risk populations including children and immunocompromised individuals. Treatment of the disease largely consists of supportive care and management of any associated complications including bacterial infection, pneumonia, and encephalitis.1

The differential diagnosis of MPXV includes other ulcerative lesions that can occur on the genital skin. Fixed drug eruptions often present on the penis,6 but there was no identifiable inciting drug in our patient. Herpes simplex virus infection was very high on the differential given our patient’s history of recurrent infections and association with a targetoid rash, but HHV type 1 and HHV type 2 testing of the lesion was negative. A syphilitic chancre also may present with the nontender genital ulceration7 that was seen in our patient, but serology did not support this diagnosis. Cutaneous Crohn disease also may manifest with genital ulceration even before a diagnosis of Crohn disease is made, but these lesions often present as linear knife-cut ulcerations of the anogenital region.8

Our case further supports a clinical presentation that diverges from the more traditional cases of MPXV. Additionally, associated EM may be a clue to infection, especially in cases of negative HHV and other sexually transmitted infection testing.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—a potential threat? a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:E0010141.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, et al. The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus. J Autoimmun. 2022;131:102855.

- Eisenstadt R, Liszewski WJ, Nguyen CV. Recognizing minimal cutaneous involvement or systemic symptoms in monkeypox. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1457-1458.

- Català A, Clavo-Escribano P, Riera-Monroig J, et al. Monkeypox outbreak in Spain: clinical and epidemiological findings in a prospective cross-sectional study of 185 cases [published online August 2, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:765-772.

- Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:889-902.

- Waleryie-Allanore L, Obeid G, Revuz J. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:348-375.

- Stary G, Stary A. Sexually transmitted infections. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1447-1469.

- Rosenbach MA, Wanat KA, Reisenauer A, et al. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Elsevier; 2018:1644-1663.

A 50-year-old man with a history of recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infections presented to the hospital with genital lesions and swelling of 5 days’ duration. Prior to admission, the patient was treated with a course of valacyclovir by an urgent care physician without improvement. Physical examination revealed a 3-cm, nontender, shallow, ulcerative plaque with irregular borders and a purulent yellow base distributed on the distal shaft of the penis with extension into the coronal sulcus. A few other scattered erosions were noted on the distal penile shaft. He had associated diffuse nonpitting edema of the penis and scrotum as well as tender bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. Three days after the genital ulcerations began, the patient developed a nontender erythematous papule with a necrotic center on the right jaw followed by an eruption of erythematous papulopustules on the arms and trunk. The patient denied dysuria, purulent penile discharge, fevers, chills, headaches, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. The patient was sexually active exclusively with females and had more than 10 partners in the prior year. Shortly after hospital admission, the patient developed red targetoid plaques on the groin, trunk, and arms. No oral mucosal lesions were identified.

Ulcerated Nodule on the Lip

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastasis

A shave biopsy of the lip revealed a diffuse cellular infiltrate filling the superficial and deep dermis (Figure 1A). Morphologically, the cells had abundant clear cytoplasm with eccentrically located, pleomorphic, hyperchromatic nuclei with occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 1B). The cells stained positive for AE1/ AE3 on immunohistochemistry (Figure 2). A punch biopsy of the nodule in the right axillary vault revealed a morphologically similar proliferation of cells. A colonoscopy revealed a completely obstructing circumferential mass in the distal ascending colon. A biopsy of the mass confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma, supporting a diagnosis of cutaneous metastases from adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient underwent resection of the lip tumor and started multiagent chemotherapy for his newly diagnosed stage IV adenocarcinoma of the colon. The patient died, despite therapy.

Cutaneous metastasis from solid malignancies is uncommon, as only 1.3% of them exhibit cutaneous manifestations at presentation.1 Cutaneous metastasis from signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCA) of the colon is uncommon, and cutaneous metastasis of colorectal SRCA rarely precedes the diagnosis of the primary lesion.2 Among the colorectal cancers that metastasize to the skin, metastasis to the face occurs in only 0.5% of patients.3

Signet ring cell adenocarcinomas are poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas histologically characterized by the neoplastic cells’ circular to ovoid appearance with a flattened top.4,5 This distinctive shape is from the displacement of the nucleus to the periphery of the cell due to the accumulation of intracytoplasmic mucin.4 Classically, malignancies are characterized as an SRCA if more than 50% of the cells have a signet ring cell morphology; if the signet ring cells comprise less than 50% of the neoplasm, the tumor is designated as an adenocarcinoma with signet ring morphology.4 The most common cause of cutaneous metastasis with signet ring morphology is gastric cancer, while colorectal carcinoma is less common.1 Colorectal SRCAs usually are found in the right colon or the rectum in comparison to other colonic sites.6

Clinically, cutaneous metastasis can present in a variety of ways. The most common presentation is nodular lesions that may coalesce to become zosteriform in configuration or lesions that mimic inflammatory dermatoses.7 Cutaneous metastasis is more common in breast and lung cancer, and when it occurs secondary to colorectal cancer, cutaneous metastasis rarely predates the detection of the primary neoplasm.2

The clinical appearance of metastasis is not specific and can mimic many entities8; therefore, a high index of suspicion must be employed when managing patients, even those without a history of internal malignancy. In our patient, the smooth nodular lesion appeared similar to a basal cell carcinoma; however, basal cell carcinomas appear more pearly, and arborizing telangiectasia often is seen.9 Merkel cell carcinoma is common on sundamaged skin of the head and neck but clinically appears more violaceous than the lesion seen in our patient.10 Paracoccidioidomycosis may form ulcerated papulonodules or plaques, especially around the nose and mouth. In many of these cases, lesions develop from contiguous lesions of the oral mucosa; therefore, the presence of oral lesions will help distinguish this infectious entity from cutaneous metastasis. Multiple lesions usually are identified when there is hematogenous dissemination.11 Mycosis fungoides is a subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by multiple patches, plaques, and nodules on sun-protected areas. Involvement of the head and neck is not common, except in the folliculotropic subtype, which has a separate and distinct clinical morphology.12

The development of signet ring morphology from an adenocarcinoma can be attributed to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to downstream activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the subsequent loss of intercellular tight junctions. The mucin 4 gene, MUC4, also is upregulated by PI3K activation and possesses antiapoptotic and mitogenic effects in addition to its mucin secretory function.13

The neoplastic cells in SRCAs stain positive for mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid–Schiff, which highlights the mucinous component of the cells.7 Immunohistochemical stains with CK7, CK20, AE1/AE3, and epithelial membrane antigen can be implemented to confirm an epithelial origin of the primary cancer.7,13 CK20 is a low-molecular-weight cytokeratin normally expressed by Merkel cells and by the epithelium of the gastrointestinal tract and urothelium, whereas CK7 expression typically is expressed in the lungs, ovaries, endometrium, and breasts, but not in the lower gastrointestinal tract.14 Differentiating primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma from cutaneous metastasis can be accomplished with a thorough clinical history; however, p63 positivity supports a primary cutaneous lesion and may be useful in certain situations.7 CDX2 stains can be utilized to aid in localizing the primary neoplasm when it is unknown, and when positive, it suggests a lower gastrointestinal tract origin. However, special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) recently has been proposed as a replacement immunohistochemical marker for CDX2, as it has greater specificity for SRCA of the lower gastrointestinal tract.15 Benign entities with signet ring cell morphology are difficult to distinguish from SRCA; however, malignant lesions are more likely to demonstrate an infiltrative growth pattern, frequent mitotic figures, and apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry also can be utilized to support the diagnosis of benign proliferation with signet ring morphology, as benign lesions often will demonstrate E-cadherin positivity and negativity for p53 and Ki-67.13

Cutaneous metastasis usually correlates to advanced disease and generally indicates a worse prognosis.13 Signet ring cell morphology in both gastric and colorectal cancer portends a poor prognosis, and there is a lower overall survival in patients with these malignancies compared to cancers of the same organ with non–signet ring cell morphology.4,8

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

- Mandzhieva B, Jalil A, Nadeem M, et al. Most common pathway of metastasis of rectal signet ring cell carcinoma to the skin: hematogenous. Cureus. 2020;12:E6890.

- Parente P, Ciardiello D, Reggiani Bonetti L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from colorectal cancer: making light on an unusual and misdiagnosed event. Life. 2021;11:954.

- Picciariello A, Tomasicchio G, Lantone G, et al. Synchronous “skip” facial metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:68.

- Benesch MGK, Mathieson A. Epidemiology of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas. Cancers. 2020;12:1544.

- Xu Q, Karouji Y, Kobayashi M, et al. The PI 3-kinase-Rac-p38 MAP kinase pathway is involved in the formation of signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:5537-5544.

- Morales-Cruz M, Salgado-Nesme N, Trolle-Silva AM, et al. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the rectum: atypical metastatic presentation. BMJ Case Rep CP. 2019;12:E229135.

- Demirciog˘lu D, Öztürk Durmaz E, Demirkesen C, et al. Livedoid cutaneous metastasis of signet‐ring cell gastric carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:785-788.

- Dong X, Sun G, Qu H, et al. Prognostic significance of signet-ring cell components in patients with gastric carcinoma of different stages. Front Surg. 2021;8:642468.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Nguyen AH, Tahseen AI, Vaudreuil AM, et al. Clinical features and treatment of vulvar Merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol Res Pract. 2017;4:2.

- Marques, SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:610-615.

- Larocca C, Kupper T. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin. 2019;33:103-120.

- Gündüz Ö, Emeksiz MC, Atasoy P, et al. Signet-ring cells in the skin: a case of late-onset cutaneous metastasis of gastric carcinoma and a brief review of histological approach. Dermatol Rep. 2017;8:6819.

- Al-Taee A, Almukhtar R, Lai J, et al. Metastatic signet ring cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:283.

- Ma C, Lowenthal BM, Pai RK. SATB2 is superior to CDX2 in distinguishing signet ring cell carcinoma of the upper gastrointestinal tract and lower gastrointestinal tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018; 42:1715-1722.

A 79-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and atrial fibrillation presented with an enlarging lesion on the right side of the upper cutaneous lip of 5 weeks’ duration. He had no personal history of skin cancer or other malignancy and was up to date on all routine cancer screenings. He reported associated lip and oral cavity tenderness, weakness, and a 13.6-kg (30-lb) unintentional weight loss over the last 6 months. He had used over-the-counter bacitracin ointment on the lesion without relief. A full-body skin examination revealed a firm, mobile, flesh-colored, nondraining nodule in the right axillary vault.

Polycyclic Scaly Eruption

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

A punch biopsy from the right lower back supported the clinical diagnosis of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. The patient underwent genetic testing and was found to have a heterozygous mutation in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 5 gene, SPINK5, that was consistent with a diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.

Netherton syndrome is an autosomal-recessive genodermatosis characterized by a triad of congenital ichthyosis, hair shaft abnormalities, and atopic diatheses.1,2 It affects approximately 1 in 200,000 live births2,3; however, it is considered by many to be underdiagnosed due to the variability in the clinical appearance. Therefore, the incidence of Netherton syndrome may actually be closer 1 in 50,000 live births.1 The manifestations of the disease are caused by a germline mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes the serine protease inhibitor LEKTI.1,2 Dysfunctional LEKTI results in increased proteolytic activity of the lipid-processing enzymes in the stratum corneum, resulting in a disruption in the lipid bilayer.1 Dysfunctional LEKTI also results in a loss of the antiinflammatory and antimicrobial function of the stratum corneum. Clinical features of Netherton syndrome usually present at birth or shortly thereafter.1 Congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, or the continuous peeling of the skin, is a common presentation seen at birth and in the neonatal period.2 As the patient ages, the dermatologic manifestations evolve into serpiginous and circinate, erythematous plaques with a characteristic peripheral, double-edged scaling.1,2 This distinctive finding is termed ichthyosis linearis circumflexa and is pathognomonic for the syndrome.2 Lesions often affect the trunk and extremities and demonstrate an undulating course.1 Because eczematous and lichenified plaques in flexural areas as well as pruritus are common clinical features, this disease often is misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis,1,3 as was the case in our patient.

Patients with Netherton syndrome can present with various hair abnormalities. Trichorrhexis invaginata, known as bamboo hair, is the intussusception of the hair shaft and is characteristic of the disease.3 It develops from a reduced number of disulfide bonds, which results in cortical softening.1 Trichorrhexis invaginata may not be present at birth and often improves with age.1,3 Other hair shaft abnormalities such as pili torti, trichorrhexis nodosa, and helical hair also may be observed in Netherton syndrome.1 Extracutaneous manifestations also are typical. There is immune dysregulation of memory B cells and natural killer cells, which manifests as frequent respiratory and skin infections as well as sepsis.1,2 Patients also may have increased levels of serum IgE and eosinophilia resulting in atopy and allergic reactions to various triggers such as foods.1 The neonatal period also may be complicated by dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, inability to regulate body temperature, and failure to thrive.1,3

When there is an extensive disruption of the skin barrier during the neonatal period, there may be severe electrolyte imbalances and thermoregulatory challenges necessitating treatment in the neonatal intensive care unit. Cutaneous disease can be treated with topical therapies with variable success.1 Topical therapies for symptom management include emollients, corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, calcipotriene, and retinoids; however, utmost caution must be employed with these therapies due to the increased risk for systemic absorption resulting from the disturbance of the skin barrier. When therapy with topical tacrolimus is implemented, monitoring of serum drug levels is required.1 Pruritus may be treated symptomatically with oral antihistamines. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been shown to decrease the frequency of infections and improve skin inflammation. Systemic retinoids have unpredictable effects and result in improvement of disease in some patients but exacerbation in others. Phototherapy with narrowband UVB, psoralen plus UVA, UVA1, and balneophototherapy also are effective treatments for cutaneous disease.1 Dupilumab has been shown to decrease pruritus, improve hair abnormalities, and improve skin disease, thereby demonstrating its effectiveness in treating the atopy and ichthyosis in Netherton syndrome.4