User login

Infant with bilious emesis

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

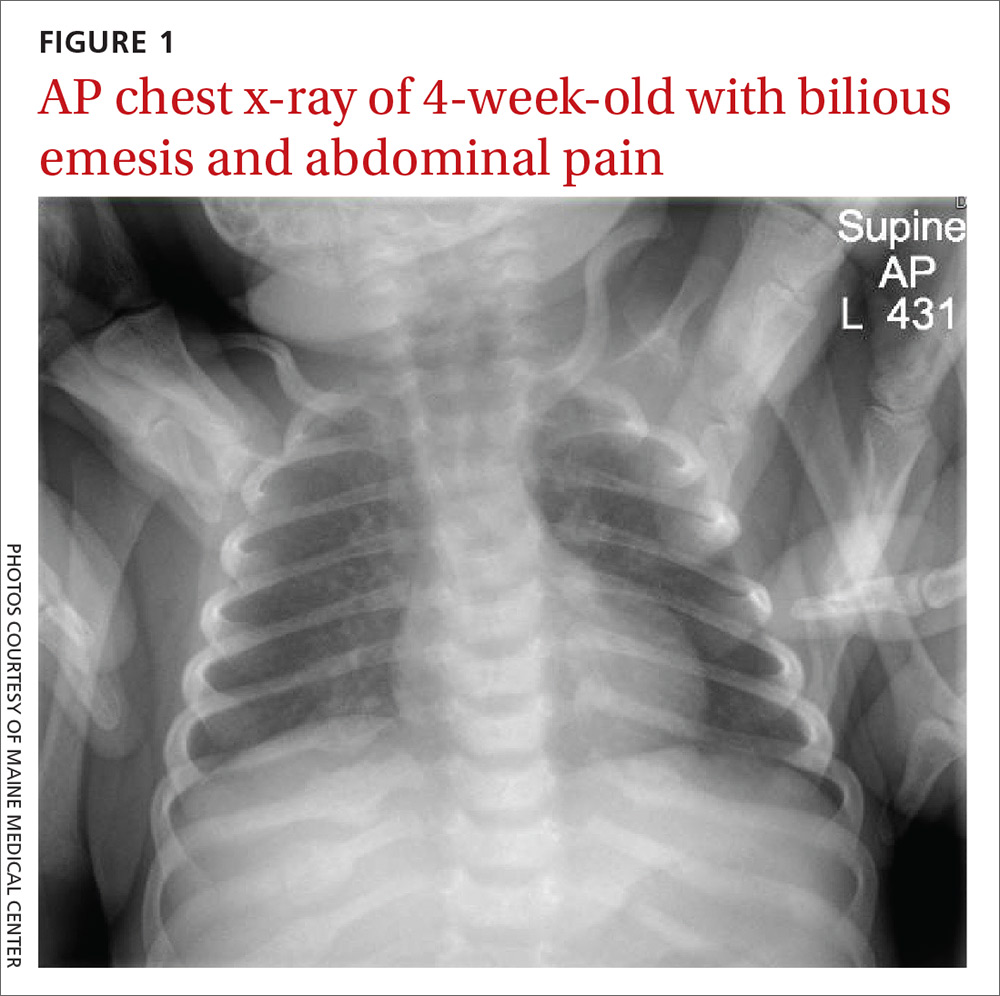

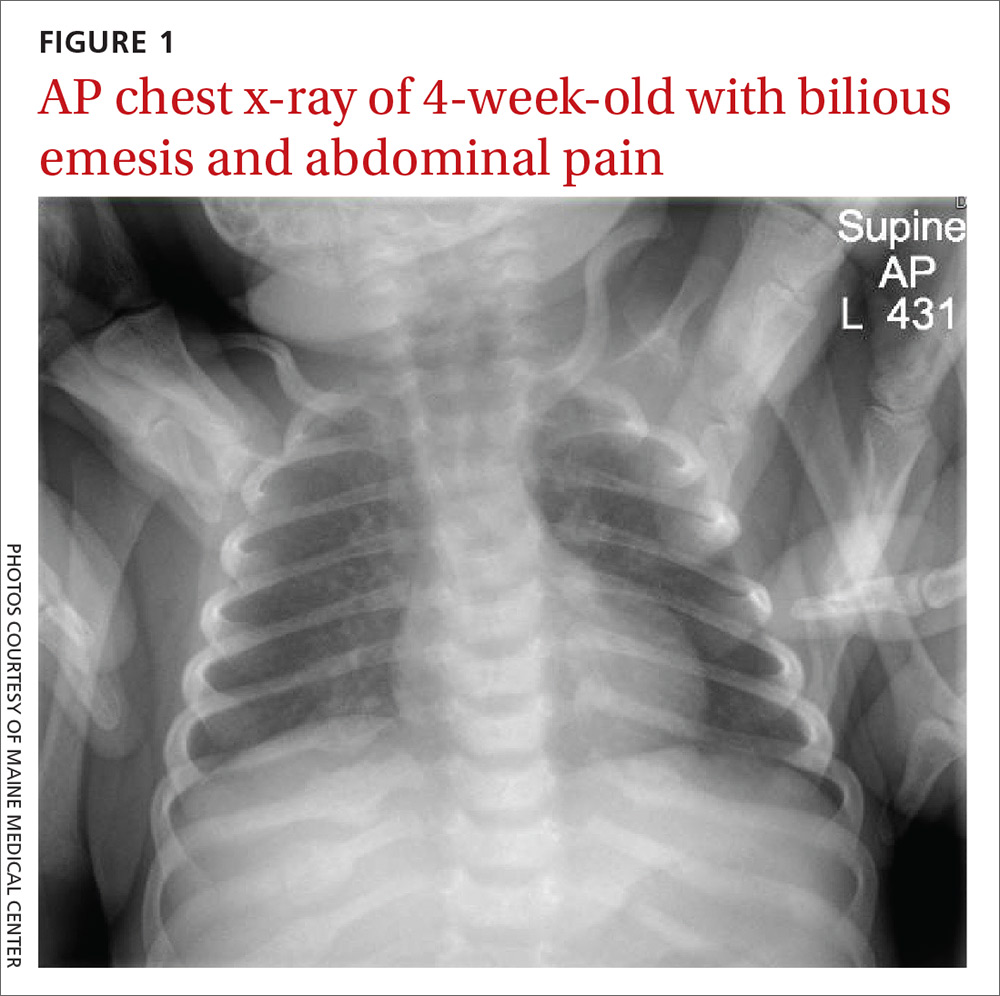

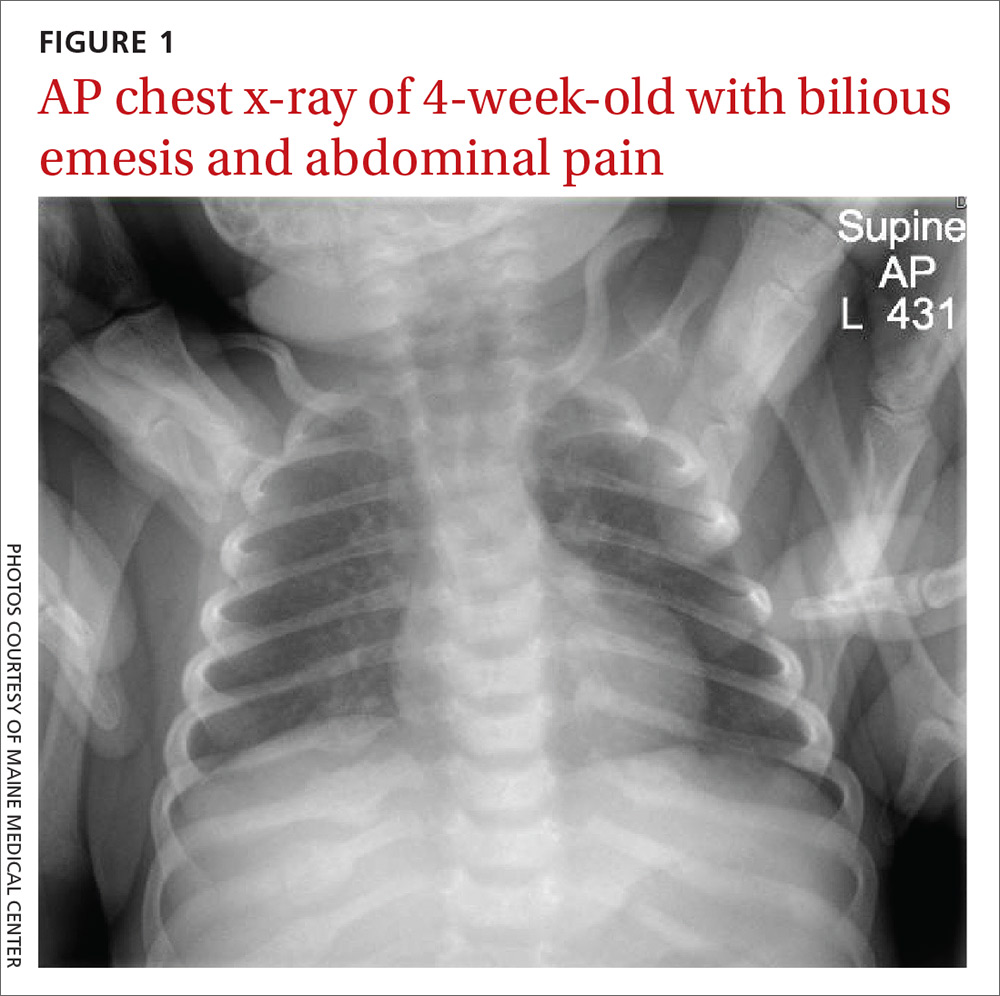

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

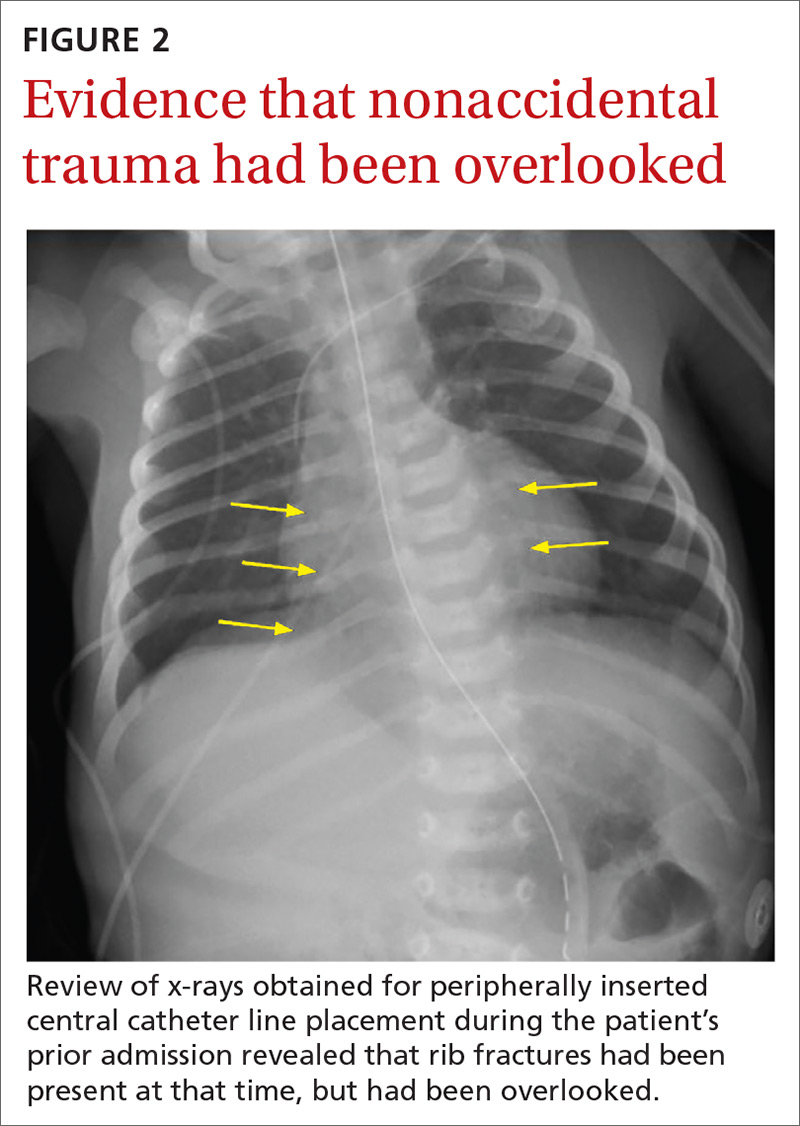

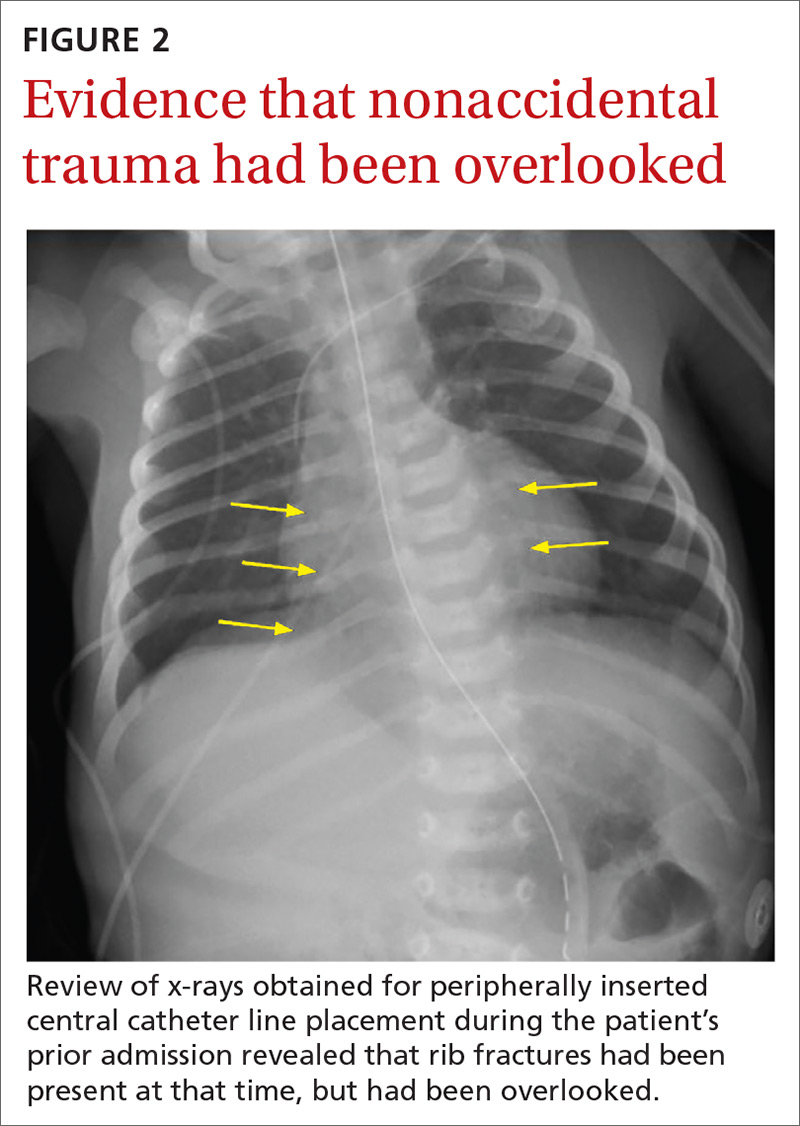

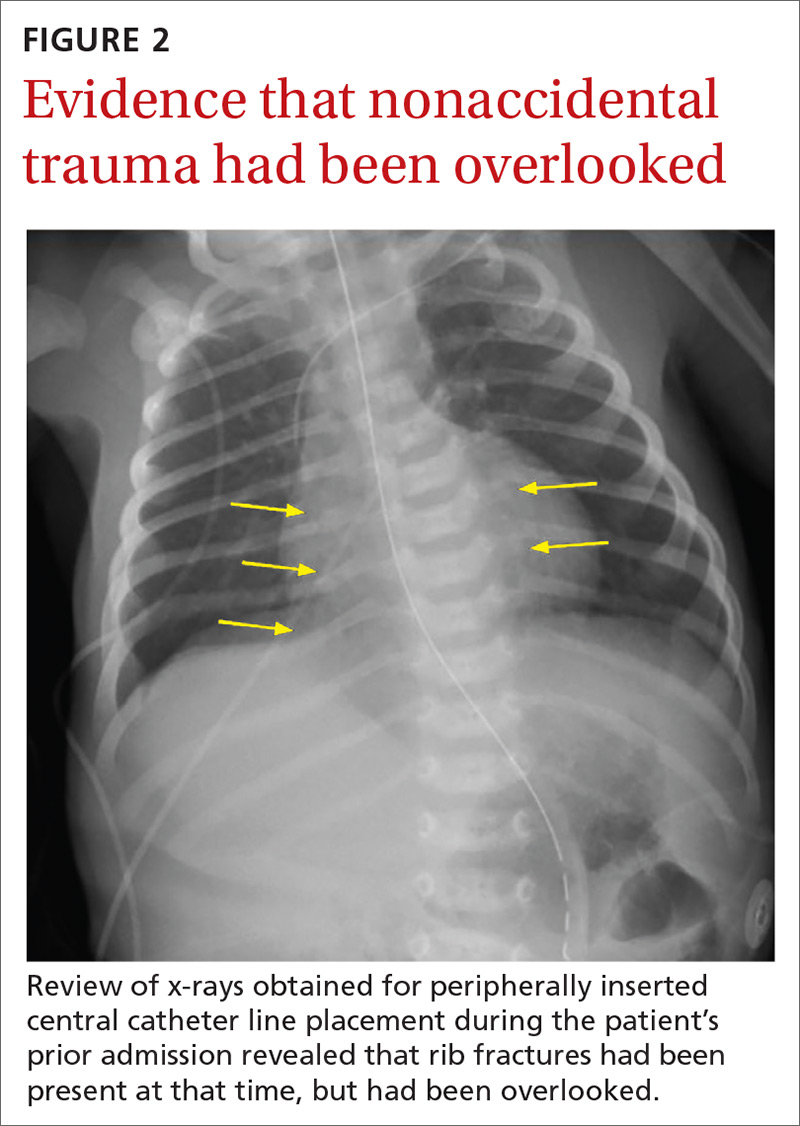

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A 4-week-old term boy presented to the emergency department (ED) with recurrent bilious emesis. He had a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome, related to his mother’s use of Subutex (a form of suboxone that is considered safer during pregnancy) for her opioid addiction, and a Ladd procedure at Day 7 of life for intestinal malrotation with volvulus. He had been discharged from the hospital 4 days earlier, after recovery from surgery.

He had been doing well until the prior evening, when he developed “yellow-green” emesis and appeared to have intermittent abdominal pain. His parents said that he was refusing to take formula and he’d had frequent bilious emesis. They also noted he’d had 1 wet diaper in the past 12 hours and appeared “sleepier” than usual.

In the ED, the patient was listless, with thin and tremulous extremities. His fontanelle was flat, and his pupils were equal, round, and reactive. His mucous membranes were dry, skin was mottled, and capillary refill was delayed. His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. His abdomen was soft, mildly distended, and diffusely tender to palpation, with well-healing laparotomy scars. His reflexes were normal, with slightly increased tone. No bruising was noted.

An acute abdominal series, including an AP view chest x-ray (FIGURE 1), was obtained to rule out recurrent volvulus, free air, or small bowel obstruction.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nonaccidental trauma

The chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) showed multiple bilateral posterior rib fractures concerning for nonaccidental trauma (NAT). The remaining acute abdominal series films (not shown) revealed the reason for his bilious emesis: a partial bowel obstruction related to his surgical procedure. Review of x-rays obtained for peripherally inserted central catheter line confirmation during his previous admission (FIGURE 2) revealed that the rib fractures had been present at that time but had been overlooked.

This case illustrates the importance of considering NAT in the differential diagnosis of any sick infant. There are an estimated 700,000 cases of child abuse and neglect and 600 fatalities per year in the United States.1,2 The differential diagnosis for fracture or bruising in infants includes accidental trauma, bony abnormalities (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta), bleeding disorders, and trauma from medical procedures such as CPR or surgery.1

Ask these questions, look beyond that single bruise

When evaluating for NAT, the history and physical exam are crucial. It is essential to ask if there were any witnesses, establish who was caring for the child, and investigate any delays in seeking medical evaluation.1 During the exam, undress the child and examine every inch of skin, looking for bruising or abrasions, especially on the face, ear, neck, and oral cavity.

Any bruising in a nonambulatory infant should raise suspicion for NAT. One study showed that more than half of infants with a single bruise had additional injuries identified upon further work-up.3 Fundoscopic exam with photographs should be completed to evaluate for retinal hemorrhage.

Additional work-up should include a skeletal survey for all children younger than 24 months2 in addition to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the head, complete blood count, and a coagulation panel. If there is concern for abdominal trauma, a complete metabolic panel and lipase test may be useful.4 If liver function tests show elevated liver enzymes (> 80 IU/L), abdominal CT with contrast is indicated.4

Continue to: Research has underscored...

Research has underscored the importance of screening siblings and other contacts of abused children. In particular, the twin of an abused child has a much higher risk for abuse.5 A skeletal survey should be obtained in contacts (< 24 months) of abused children—regardless of their physical exam findings.5

Management depends on injury type

The management of children with NAT depends on the injuries. Once these injuries are addressed, the next step is to determine the safest place for the infant/child to be discharged. The involvement of local social workers and Child Protective Services (CPS) is pivotal for this determination.2

Our patient. To treat the partial small bowel obstruction noted on an abdominal CT, the patient received intravenous fluids and nasogastric tube decompression. However, due to ongoing distension and high nasogastric tube output, the patient was taken to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy. An adhesive band in the right lower quadrant was found to be causing the obstruction and was lysed.

We consulted CPS and social workers about the rib fractures identified on x-ray. We considered osteogenesis imperfecta as a possible cause, but genetic testing was negative. The ophthalmology exam was negative for retinal hemorrhages. A bone scan confirmed posterior rib fractures with no other injuries. CPS was unable to confirm that the fractures had not been sustained while the child was an inpatient, so it was ultimately determined that the patient should be discharged home with his parents with supervision.

CORRESPONDENCE

Anne Huyler, MD, Maine Medical Center, 22 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

1. Berkowitz CD. Physical abuse of children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1659-1666.

2. Lindberg DM, Berger RP, Reynolds MS, et al. Yield of skeletal survey by age in children referred to abuse specialists. J Pediatr. 2014;164:1268-1273.e1.

3. Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, et al. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165:383-388.e1.

4. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, et al. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131:268-275.

5. Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Laskey AL, et al. Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:193-201.

Unusual shoulder injury from a motorcycle crash

A 38-YEAR-OLD MAN was brought into our emergency department (ED) after driving his motorcycle at high speed into a tree. The patient, who hadn’t been wearing a helmet, was thrown 30 feet. When EMS arrived, the patient was unresponsive, with his right arm in the air. En route, the patient regained consciousness; he appeared intoxicated and became combative.

The patient was evaluated in the ED and his vital signs were normal. His right arm was abducted and over his head (FIGURE 1). He reported significant pain with palpation and attempts at range of motion. We were unable to place the patient’s arm at his side. Other than some minor abrasions, the patient appeared to have no other injuries.

FIGURE 1Right upper extremity on presentation

Routine laboratory tests showed an alcohol level of 0.175 g/dL and urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and tetrahydrocannabinol. A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was negative. We ordered a right shoulder x-ray and a chest x-ray.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Inferior dislocation of the shoulder

The right shoulder x-ray (FIGURE 2) revealed luxatio erecta—an inferior dislocation of the shoulder. The humeral head was displaced inferiorly with respect to the glenoid fossa and there was an associated greater tuberosity fracture. The chest x-ray demonstrated mild pulmonary contusions.

FIGURE 2

Right shoulder radiograph reveals luxatio erecta with greater tuberosity fracture

An uncommon dislocation

Inferior shoulder dislocation or luxatio erecta is the least common type of glenohumeral dislocation, comprising only about 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 The 2 other types of shoulder dislocations—anterior and posterior—account for 95% to 97% and 2% to 4% of dislocations, respectively.2

Injury occurs in one of 2 ways, either by a direct or indirect mechanism. A direct dislocation occurs when there is axial loading on an arm that is fully abducted at the shoulder.3 The indirect mechanism, which is more common, is caused by a hyperabduction stress that directs the humeral neck superiorly against the acromion process, forcing the humeral head out of the glenoid fossa inferiorly.2 The indirect mechanism usually occurs when a patient falls and reacts by grasping an object above his or her head, resulting in hyperabduction.

Sometimes, there is no trauma. True inferior dislocations have also been reported in patients with stroke, septic arthritis, and other neuromuscular diseases.4

The presentation is distinctive

Patients with this type of dislocation present with their arm elevated, elbow flexed, and hand behind their head. Due to mechanical entrapment of the humeral head, patients can’t move their arm. The abducted position of the arm may hinder further assessment with computed tomography (CT) for life-threatening injuries, as was the case with our patient.

While an immobile, abducted arm is virtually pathognomonic, radiographs are useful for confirming the diagnosis and assessing for associated fractures. It is essential to obtain anteroposterior, axillary, and Y views.5 Radiographs typically show the shaft of the humerus directed superiorly and parallel to the scapular spine, with the humeral head below the coracoid process or glenoid fossa.3,5

Rotator cuff tears are a common complication

There are a number of complications associated with luxatio erecta. Eighty percent of patients with this injury have either an associated rotator cuff tear or a fracture of the greater tuberosity (which we’ll get to in a bit).3 Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown rotator cuff injuries to involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and, less frequently, the subscapularis tendon.6 It’s believed that rotator cuff tears may be even more prevalent than reported in the literature since they are often underrecognized at the time of presentation with the dislocation.6

Other complications. Sixty percent of patients report some degree of neurologic dysfunction after the dislocation.5 The most common nerve affected is the axillary, followed by the radial, ulnar, and median nerves.3 These injuries are more likely to occur with associated fractures of the greater tuberosity or axillary artery injuries.7 Symptoms generally resolve after reduction, although there have been cases that have taken up to 6 weeks to resolve.8

Vascular compromise, most commonly occurring as a result of axillary artery injury, has been reported in 3.3% of cases.5 This injury is most common in elderly patients, with 75% of cases occurring in patients older than 60 years.7 It’s been hypothesized that this is due to the loss of arterial elasticity as an individual ages. The most common presenting signs and symptoms include absent radial and/or brachial pulses, severe pain, axillary swelling, axillary masses due to hematoma formation, and neurologic deficits.7 Complications are minimal if diagnosed and treated early.

The most expeditious way to diagnose this complication is to obtain a Doppler ultrasound of the injured extremity. If surgery is indicated, saphenous vein graft has been reported as a successful treatment.3

Fractures are another complication to watch for. The most common fractures are of the greater tuberosity, although fractures to the glenoid, humeral head, acromion, and scapular body have also been reported.8 Fracture management depends on the characteristics of the fracture, including displacement, size of the fragment, and joint stability.

Treatment involves traction and countertraction

Luxatio erecta is normally treated by closed reduction using the traction-countertraction technique. In this maneuver, the shoulder is reduced with direct traction, while countertraction is applied with a sheet wrapped over the clavicle on the affected side and pulled down and across the chest toward the unaffected side. The affected arm is pulled in a cephalad direction and further abducted until the humeral head is reduced within the glenoid fossa. After reduction, the arm is gradually moved downwards toward the patient’s side and splinted in the adducted position.8

Special care should be taken with patients who are at risk of cervical spine injuries. Postreduction radiographs should be obtained to verify proper humeral placement and to assess for any associated fractures. While closed reduction is the definitive treatment, patients run the risk of recurrent instability that may necessitate capsular reconstruction.1

Our patient recovered well

Our patient was sedated with fentanyl and midazolam, and his shoulder was reduced with the traction-countertraction technique described earlier. Postreduction radiographs revealed satisfactory alignment of the right glenohumeral joint and that the greater tuberosity was reduced to within a centimeter of its normal position. No additional fractures were identified.

After the reduction, a head CT scan was done; it revealed a small intracerebral hemorrhage. The patient was admitted overnight and discharged the following day with a sling and swathe and instructions to follow up with orthopedics.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA, Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:423-426.

2. Goldstein JR, Eilbert WP. Locked anterior-inferior shoulder subluxation presenting as luxatio erecta. J Emerg Med 2004;27:245-248.

3. Yamamoto T, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M, et al. Luxatio erecta: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop 2003;32:601-603.

4. Sonanis SV, Das S, Deshmukh N, et al. A true traumatic inferior dislocation of shoulder. Injury 2002;33:842-844.

5. Yanturali S, Aksay E, Holliman CJ, et al. Luxatio erecta: clinical presentation and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:85-89.

6. Krug DK, Vinson EN, Helms CA. MRI findings associated with luxatio erecta humeri. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:27-33.

7. Plaga BR, Looby P, Feldhaus SJ, et al. Axillary artery injury secondary to inferior shoulder dislocation. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:599-601.

8. Sewecke JJ, Varitimidis SE. Bilateral luxatio erecta: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2006;35:578-580.

A 38-YEAR-OLD MAN was brought into our emergency department (ED) after driving his motorcycle at high speed into a tree. The patient, who hadn’t been wearing a helmet, was thrown 30 feet. When EMS arrived, the patient was unresponsive, with his right arm in the air. En route, the patient regained consciousness; he appeared intoxicated and became combative.

The patient was evaluated in the ED and his vital signs were normal. His right arm was abducted and over his head (FIGURE 1). He reported significant pain with palpation and attempts at range of motion. We were unable to place the patient’s arm at his side. Other than some minor abrasions, the patient appeared to have no other injuries.

FIGURE 1Right upper extremity on presentation

Routine laboratory tests showed an alcohol level of 0.175 g/dL and urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and tetrahydrocannabinol. A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was negative. We ordered a right shoulder x-ray and a chest x-ray.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Inferior dislocation of the shoulder

The right shoulder x-ray (FIGURE 2) revealed luxatio erecta—an inferior dislocation of the shoulder. The humeral head was displaced inferiorly with respect to the glenoid fossa and there was an associated greater tuberosity fracture. The chest x-ray demonstrated mild pulmonary contusions.

FIGURE 2

Right shoulder radiograph reveals luxatio erecta with greater tuberosity fracture

An uncommon dislocation

Inferior shoulder dislocation or luxatio erecta is the least common type of glenohumeral dislocation, comprising only about 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 The 2 other types of shoulder dislocations—anterior and posterior—account for 95% to 97% and 2% to 4% of dislocations, respectively.2

Injury occurs in one of 2 ways, either by a direct or indirect mechanism. A direct dislocation occurs when there is axial loading on an arm that is fully abducted at the shoulder.3 The indirect mechanism, which is more common, is caused by a hyperabduction stress that directs the humeral neck superiorly against the acromion process, forcing the humeral head out of the glenoid fossa inferiorly.2 The indirect mechanism usually occurs when a patient falls and reacts by grasping an object above his or her head, resulting in hyperabduction.

Sometimes, there is no trauma. True inferior dislocations have also been reported in patients with stroke, septic arthritis, and other neuromuscular diseases.4

The presentation is distinctive

Patients with this type of dislocation present with their arm elevated, elbow flexed, and hand behind their head. Due to mechanical entrapment of the humeral head, patients can’t move their arm. The abducted position of the arm may hinder further assessment with computed tomography (CT) for life-threatening injuries, as was the case with our patient.

While an immobile, abducted arm is virtually pathognomonic, radiographs are useful for confirming the diagnosis and assessing for associated fractures. It is essential to obtain anteroposterior, axillary, and Y views.5 Radiographs typically show the shaft of the humerus directed superiorly and parallel to the scapular spine, with the humeral head below the coracoid process or glenoid fossa.3,5

Rotator cuff tears are a common complication

There are a number of complications associated with luxatio erecta. Eighty percent of patients with this injury have either an associated rotator cuff tear or a fracture of the greater tuberosity (which we’ll get to in a bit).3 Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown rotator cuff injuries to involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and, less frequently, the subscapularis tendon.6 It’s believed that rotator cuff tears may be even more prevalent than reported in the literature since they are often underrecognized at the time of presentation with the dislocation.6

Other complications. Sixty percent of patients report some degree of neurologic dysfunction after the dislocation.5 The most common nerve affected is the axillary, followed by the radial, ulnar, and median nerves.3 These injuries are more likely to occur with associated fractures of the greater tuberosity or axillary artery injuries.7 Symptoms generally resolve after reduction, although there have been cases that have taken up to 6 weeks to resolve.8

Vascular compromise, most commonly occurring as a result of axillary artery injury, has been reported in 3.3% of cases.5 This injury is most common in elderly patients, with 75% of cases occurring in patients older than 60 years.7 It’s been hypothesized that this is due to the loss of arterial elasticity as an individual ages. The most common presenting signs and symptoms include absent radial and/or brachial pulses, severe pain, axillary swelling, axillary masses due to hematoma formation, and neurologic deficits.7 Complications are minimal if diagnosed and treated early.

The most expeditious way to diagnose this complication is to obtain a Doppler ultrasound of the injured extremity. If surgery is indicated, saphenous vein graft has been reported as a successful treatment.3

Fractures are another complication to watch for. The most common fractures are of the greater tuberosity, although fractures to the glenoid, humeral head, acromion, and scapular body have also been reported.8 Fracture management depends on the characteristics of the fracture, including displacement, size of the fragment, and joint stability.

Treatment involves traction and countertraction

Luxatio erecta is normally treated by closed reduction using the traction-countertraction technique. In this maneuver, the shoulder is reduced with direct traction, while countertraction is applied with a sheet wrapped over the clavicle on the affected side and pulled down and across the chest toward the unaffected side. The affected arm is pulled in a cephalad direction and further abducted until the humeral head is reduced within the glenoid fossa. After reduction, the arm is gradually moved downwards toward the patient’s side and splinted in the adducted position.8

Special care should be taken with patients who are at risk of cervical spine injuries. Postreduction radiographs should be obtained to verify proper humeral placement and to assess for any associated fractures. While closed reduction is the definitive treatment, patients run the risk of recurrent instability that may necessitate capsular reconstruction.1

Our patient recovered well

Our patient was sedated with fentanyl and midazolam, and his shoulder was reduced with the traction-countertraction technique described earlier. Postreduction radiographs revealed satisfactory alignment of the right glenohumeral joint and that the greater tuberosity was reduced to within a centimeter of its normal position. No additional fractures were identified.

After the reduction, a head CT scan was done; it revealed a small intracerebral hemorrhage. The patient was admitted overnight and discharged the following day with a sling and swathe and instructions to follow up with orthopedics.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A 38-YEAR-OLD MAN was brought into our emergency department (ED) after driving his motorcycle at high speed into a tree. The patient, who hadn’t been wearing a helmet, was thrown 30 feet. When EMS arrived, the patient was unresponsive, with his right arm in the air. En route, the patient regained consciousness; he appeared intoxicated and became combative.

The patient was evaluated in the ED and his vital signs were normal. His right arm was abducted and over his head (FIGURE 1). He reported significant pain with palpation and attempts at range of motion. We were unable to place the patient’s arm at his side. Other than some minor abrasions, the patient appeared to have no other injuries.

FIGURE 1Right upper extremity on presentation

Routine laboratory tests showed an alcohol level of 0.175 g/dL and urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and tetrahydrocannabinol. A focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exam was negative. We ordered a right shoulder x-ray and a chest x-ray.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Inferior dislocation of the shoulder

The right shoulder x-ray (FIGURE 2) revealed luxatio erecta—an inferior dislocation of the shoulder. The humeral head was displaced inferiorly with respect to the glenoid fossa and there was an associated greater tuberosity fracture. The chest x-ray demonstrated mild pulmonary contusions.

FIGURE 2

Right shoulder radiograph reveals luxatio erecta with greater tuberosity fracture

An uncommon dislocation

Inferior shoulder dislocation or luxatio erecta is the least common type of glenohumeral dislocation, comprising only about 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations.1 The 2 other types of shoulder dislocations—anterior and posterior—account for 95% to 97% and 2% to 4% of dislocations, respectively.2

Injury occurs in one of 2 ways, either by a direct or indirect mechanism. A direct dislocation occurs when there is axial loading on an arm that is fully abducted at the shoulder.3 The indirect mechanism, which is more common, is caused by a hyperabduction stress that directs the humeral neck superiorly against the acromion process, forcing the humeral head out of the glenoid fossa inferiorly.2 The indirect mechanism usually occurs when a patient falls and reacts by grasping an object above his or her head, resulting in hyperabduction.

Sometimes, there is no trauma. True inferior dislocations have also been reported in patients with stroke, septic arthritis, and other neuromuscular diseases.4

The presentation is distinctive

Patients with this type of dislocation present with their arm elevated, elbow flexed, and hand behind their head. Due to mechanical entrapment of the humeral head, patients can’t move their arm. The abducted position of the arm may hinder further assessment with computed tomography (CT) for life-threatening injuries, as was the case with our patient.

While an immobile, abducted arm is virtually pathognomonic, radiographs are useful for confirming the diagnosis and assessing for associated fractures. It is essential to obtain anteroposterior, axillary, and Y views.5 Radiographs typically show the shaft of the humerus directed superiorly and parallel to the scapular spine, with the humeral head below the coracoid process or glenoid fossa.3,5

Rotator cuff tears are a common complication

There are a number of complications associated with luxatio erecta. Eighty percent of patients with this injury have either an associated rotator cuff tear or a fracture of the greater tuberosity (which we’ll get to in a bit).3 Magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown rotator cuff injuries to involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and, less frequently, the subscapularis tendon.6 It’s believed that rotator cuff tears may be even more prevalent than reported in the literature since they are often underrecognized at the time of presentation with the dislocation.6

Other complications. Sixty percent of patients report some degree of neurologic dysfunction after the dislocation.5 The most common nerve affected is the axillary, followed by the radial, ulnar, and median nerves.3 These injuries are more likely to occur with associated fractures of the greater tuberosity or axillary artery injuries.7 Symptoms generally resolve after reduction, although there have been cases that have taken up to 6 weeks to resolve.8

Vascular compromise, most commonly occurring as a result of axillary artery injury, has been reported in 3.3% of cases.5 This injury is most common in elderly patients, with 75% of cases occurring in patients older than 60 years.7 It’s been hypothesized that this is due to the loss of arterial elasticity as an individual ages. The most common presenting signs and symptoms include absent radial and/or brachial pulses, severe pain, axillary swelling, axillary masses due to hematoma formation, and neurologic deficits.7 Complications are minimal if diagnosed and treated early.

The most expeditious way to diagnose this complication is to obtain a Doppler ultrasound of the injured extremity. If surgery is indicated, saphenous vein graft has been reported as a successful treatment.3

Fractures are another complication to watch for. The most common fractures are of the greater tuberosity, although fractures to the glenoid, humeral head, acromion, and scapular body have also been reported.8 Fracture management depends on the characteristics of the fracture, including displacement, size of the fragment, and joint stability.

Treatment involves traction and countertraction

Luxatio erecta is normally treated by closed reduction using the traction-countertraction technique. In this maneuver, the shoulder is reduced with direct traction, while countertraction is applied with a sheet wrapped over the clavicle on the affected side and pulled down and across the chest toward the unaffected side. The affected arm is pulled in a cephalad direction and further abducted until the humeral head is reduced within the glenoid fossa. After reduction, the arm is gradually moved downwards toward the patient’s side and splinted in the adducted position.8

Special care should be taken with patients who are at risk of cervical spine injuries. Postreduction radiographs should be obtained to verify proper humeral placement and to assess for any associated fractures. While closed reduction is the definitive treatment, patients run the risk of recurrent instability that may necessitate capsular reconstruction.1

Our patient recovered well

Our patient was sedated with fentanyl and midazolam, and his shoulder was reduced with the traction-countertraction technique described earlier. Postreduction radiographs revealed satisfactory alignment of the right glenohumeral joint and that the greater tuberosity was reduced to within a centimeter of its normal position. No additional fractures were identified.

After the reduction, a head CT scan was done; it revealed a small intracerebral hemorrhage. The patient was admitted overnight and discharged the following day with a sling and swathe and instructions to follow up with orthopedics.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA, Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:423-426.

2. Goldstein JR, Eilbert WP. Locked anterior-inferior shoulder subluxation presenting as luxatio erecta. J Emerg Med 2004;27:245-248.

3. Yamamoto T, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M, et al. Luxatio erecta: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop 2003;32:601-603.

4. Sonanis SV, Das S, Deshmukh N, et al. A true traumatic inferior dislocation of shoulder. Injury 2002;33:842-844.

5. Yanturali S, Aksay E, Holliman CJ, et al. Luxatio erecta: clinical presentation and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:85-89.

6. Krug DK, Vinson EN, Helms CA. MRI findings associated with luxatio erecta humeri. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:27-33.

7. Plaga BR, Looby P, Feldhaus SJ, et al. Axillary artery injury secondary to inferior shoulder dislocation. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:599-601.

8. Sewecke JJ, Varitimidis SE. Bilateral luxatio erecta: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2006;35:578-580.

1. Groh GI, Wirth MA, Rockwood CA, Jr. Results of treatment of luxatio erecta (inferior shoulder dislocation). J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:423-426.

2. Goldstein JR, Eilbert WP. Locked anterior-inferior shoulder subluxation presenting as luxatio erecta. J Emerg Med 2004;27:245-248.

3. Yamamoto T, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M, et al. Luxatio erecta: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Orthop 2003;32:601-603.

4. Sonanis SV, Das S, Deshmukh N, et al. A true traumatic inferior dislocation of shoulder. Injury 2002;33:842-844.

5. Yanturali S, Aksay E, Holliman CJ, et al. Luxatio erecta: clinical presentation and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:85-89.

6. Krug DK, Vinson EN, Helms CA. MRI findings associated with luxatio erecta humeri. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:27-33.

7. Plaga BR, Looby P, Feldhaus SJ, et al. Axillary artery injury secondary to inferior shoulder dislocation. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:599-601.

8. Sewecke JJ, Varitimidis SE. Bilateral luxatio erecta: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 2006;35:578-580.

Blistering rash in an older man

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 76-YEAR-OLD MAN sought care for a rash that had gotten progressively worse over the previous 3 weeks. He indicated that the rash was initially red, itchy, and located over his abdomen, but as time went by, new blisters developed in the axillae and groin, and they were painful. The patient did not have any arthralgias or systemic symptoms. The medications he was taking included simvastatin, albuterol, and finasteride.

On physical examination, the patient was in mild distress due to the pain and anxiety, and his temperature was 36.5°C (97.7°F). He had confluent areas of erythematous, denuded skin spanning his trunk, back, and proximal upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). Tense, fluid-filled blisters were most prominent in the groin and in the axillae, bilaterally.

FIGURE 1

Diffuse rash on the trunk and in the axillae

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Bullous pemphigoid

This patient had a severe and refractory case of bullous pemphigoid (BP), which was confirmed with a biopsy of the lesions.

BP is a rare autoimmune, blistering skin disease that typically occurs after age 60.1 The incidence rises with age, and is higher among women than men.1 The pathogenesis of BP involves development of autoantibodies against the subepidermal basement membrane. Deposition of immunoglobulin G (IgG) occurs, leading to immune-mediated destruction and subepidermal blistering.2

Patients will present with new-onset, widespread eruptions of bullous lesions and urticarial plaques (FIGURE 2).2 Bullae are frequent on flexural surfaces such as the groin and axillae. Urticarial plaques are often pruritic. Oral involvement occurs in a minority of cases.2 Nikolsky’s sign—exfoliation of the outermost layer of skin upon slight rubbing—is absent in BP.

FIGURE 2

Fluid-filled vesicles and bullae on right anterior thigh

Differential: Other autoimmune and blistering skin conditions

Two additional pemphigoid subtypes are part of the differential when a patient presents with a blistering skin condition: pemphigoid gestationis and mucous membrane pemphigoid.2

Pemphigoid gestationis occurs exclusively during pregnancy and the puerperium, and is self-limited.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is pathophysiologically similar to BP, but distributes preferentially on mucosal surfaces.

Pemphigus vulgaris, another autoimmune blistering skin disease, is characterized by sparse intact bullae. The mucous membrane is frequently involved, and there is a positive Nikolsky’s sign.

Additional conditions to keep in mind include epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous erythema multiforme, and bullous lupus erythematosus.

Biopsy confirms the Dx

A biopsy of a lesion confirms the diagnosis of BP and will help differentiate it from the conditions mentioned above.

Light microscopy shows eosinophil-rich subepidermal inflammatory infiltrate.2 Direct immunofluorescence displays the characteristic linear deposits of IgG and complement C3 along the basement membrane. Immunofluorescent testing on human salt-split skin may also be performed.

Drug induced? There is a subset of BP, called drug-induced BP, in which the onset of the disease is associated with the initiation of a medication. Furosemide is the most common culprit,3 although many additional medications have been described.

The pathophysiology of drug-induced BP is poorly understood.3 In some cases, discontinuation of the offending medication may halt progression and prevent recurrence. In other cases, the disease will progress to a chronic form regardless of medication discontinuation. It is reasonable to attempt medication discontinuation trials in cases where drug-induced BP is suspected.

Treat with corticosteroids

The traditional treatment of BP is high-dose oral corticosteroids. However, long-term use of systemic corticosteroids can cause significant morbidity and has been linked to an increased mortality rate in the elderly population.4 A potent topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol propionate cream 10 to 30 g/d tapering over 4 months, or 40 g/d tapering over 12 months,5,6 is an effective alternative (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Other options include methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine, niacinamide, doxycycline, intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange. These therapies are typically used in combination with corticosteroids, or after initial treatment failure. Evidence regarding their effectiveness is limited7 (SOR: B).

Although the disease is occasionally self-limited after the initial episode, most patients with BP will achieve clinical remission with medical intervention. Patients often experience recurrent outbreaks and require chronic use of immunosuppressive agents.

Our patient required ongoing care

Our patient was prescribed prednisone 80 mg/d PO in combination with topical clobetasol cream. Despite these treatments, the disease progressed. One week later, approximately 80% of his body surface was involved. He was admitted for fluid replacement and monitoring for infection.

Subsequent initiation of methotrexate, niacinamide, doxycycline, and topical clobetasol led to clinical remission. Unfortunately, the patient relapsed approximately 3 months later and required a second hospital stay.

In the ensuing months, the patient’s course was marked by frequent relapses and significant morbidity. Further treatment trials have included IV immunoglobulin, mycophenolate, and azathioprine.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Langan SM, Smeeth L, Hubbard R, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris—incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a180.-

2. Yancey KB, Egan CA. Pemphigoid: clinical, histological, immunopathologic, and therapeutic considerations. JAMA. 2000;248:350-356.

3. Lee JJ, Downham TF, 2nd. Furosemide-induced bullous pemphigoid: case report and review of literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:562-564.

4. Rzany B, Partscht K, Jung M, et al. Risk factors for lethal outcome in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:903-908.

5. Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, et al. A comparison of oral and topical corticosteroids in patients with bullous pemphigoid. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:321-327.

6. Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, et al. A comparison of two regimens of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with bullous pemphigoid: a multicenter randomized study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1681-1687.

7. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD002292.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 76-YEAR-OLD MAN sought care for a rash that had gotten progressively worse over the previous 3 weeks. He indicated that the rash was initially red, itchy, and located over his abdomen, but as time went by, new blisters developed in the axillae and groin, and they were painful. The patient did not have any arthralgias or systemic symptoms. The medications he was taking included simvastatin, albuterol, and finasteride.

On physical examination, the patient was in mild distress due to the pain and anxiety, and his temperature was 36.5°C (97.7°F). He had confluent areas of erythematous, denuded skin spanning his trunk, back, and proximal upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). Tense, fluid-filled blisters were most prominent in the groin and in the axillae, bilaterally.

FIGURE 1

Diffuse rash on the trunk and in the axillae

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Bullous pemphigoid

This patient had a severe and refractory case of bullous pemphigoid (BP), which was confirmed with a biopsy of the lesions.

BP is a rare autoimmune, blistering skin disease that typically occurs after age 60.1 The incidence rises with age, and is higher among women than men.1 The pathogenesis of BP involves development of autoantibodies against the subepidermal basement membrane. Deposition of immunoglobulin G (IgG) occurs, leading to immune-mediated destruction and subepidermal blistering.2

Patients will present with new-onset, widespread eruptions of bullous lesions and urticarial plaques (FIGURE 2).2 Bullae are frequent on flexural surfaces such as the groin and axillae. Urticarial plaques are often pruritic. Oral involvement occurs in a minority of cases.2 Nikolsky’s sign—exfoliation of the outermost layer of skin upon slight rubbing—is absent in BP.

FIGURE 2

Fluid-filled vesicles and bullae on right anterior thigh

Differential: Other autoimmune and blistering skin conditions

Two additional pemphigoid subtypes are part of the differential when a patient presents with a blistering skin condition: pemphigoid gestationis and mucous membrane pemphigoid.2

Pemphigoid gestationis occurs exclusively during pregnancy and the puerperium, and is self-limited.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is pathophysiologically similar to BP, but distributes preferentially on mucosal surfaces.

Pemphigus vulgaris, another autoimmune blistering skin disease, is characterized by sparse intact bullae. The mucous membrane is frequently involved, and there is a positive Nikolsky’s sign.

Additional conditions to keep in mind include epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous erythema multiforme, and bullous lupus erythematosus.

Biopsy confirms the Dx

A biopsy of a lesion confirms the diagnosis of BP and will help differentiate it from the conditions mentioned above.

Light microscopy shows eosinophil-rich subepidermal inflammatory infiltrate.2 Direct immunofluorescence displays the characteristic linear deposits of IgG and complement C3 along the basement membrane. Immunofluorescent testing on human salt-split skin may also be performed.

Drug induced? There is a subset of BP, called drug-induced BP, in which the onset of the disease is associated with the initiation of a medication. Furosemide is the most common culprit,3 although many additional medications have been described.

The pathophysiology of drug-induced BP is poorly understood.3 In some cases, discontinuation of the offending medication may halt progression and prevent recurrence. In other cases, the disease will progress to a chronic form regardless of medication discontinuation. It is reasonable to attempt medication discontinuation trials in cases where drug-induced BP is suspected.

Treat with corticosteroids

The traditional treatment of BP is high-dose oral corticosteroids. However, long-term use of systemic corticosteroids can cause significant morbidity and has been linked to an increased mortality rate in the elderly population.4 A potent topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol propionate cream 10 to 30 g/d tapering over 4 months, or 40 g/d tapering over 12 months,5,6 is an effective alternative (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Other options include methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine, niacinamide, doxycycline, intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange. These therapies are typically used in combination with corticosteroids, or after initial treatment failure. Evidence regarding their effectiveness is limited7 (SOR: B).

Although the disease is occasionally self-limited after the initial episode, most patients with BP will achieve clinical remission with medical intervention. Patients often experience recurrent outbreaks and require chronic use of immunosuppressive agents.

Our patient required ongoing care

Our patient was prescribed prednisone 80 mg/d PO in combination with topical clobetasol cream. Despite these treatments, the disease progressed. One week later, approximately 80% of his body surface was involved. He was admitted for fluid replacement and monitoring for infection.

Subsequent initiation of methotrexate, niacinamide, doxycycline, and topical clobetasol led to clinical remission. Unfortunately, the patient relapsed approximately 3 months later and required a second hospital stay.

In the ensuing months, the patient’s course was marked by frequent relapses and significant morbidity. Further treatment trials have included IV immunoglobulin, mycophenolate, and azathioprine.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 76-YEAR-OLD MAN sought care for a rash that had gotten progressively worse over the previous 3 weeks. He indicated that the rash was initially red, itchy, and located over his abdomen, but as time went by, new blisters developed in the axillae and groin, and they were painful. The patient did not have any arthralgias or systemic symptoms. The medications he was taking included simvastatin, albuterol, and finasteride.

On physical examination, the patient was in mild distress due to the pain and anxiety, and his temperature was 36.5°C (97.7°F). He had confluent areas of erythematous, denuded skin spanning his trunk, back, and proximal upper and lower extremities (FIGURE 1). Tense, fluid-filled blisters were most prominent in the groin and in the axillae, bilaterally.

FIGURE 1

Diffuse rash on the trunk and in the axillae

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Bullous pemphigoid

This patient had a severe and refractory case of bullous pemphigoid (BP), which was confirmed with a biopsy of the lesions.

BP is a rare autoimmune, blistering skin disease that typically occurs after age 60.1 The incidence rises with age, and is higher among women than men.1 The pathogenesis of BP involves development of autoantibodies against the subepidermal basement membrane. Deposition of immunoglobulin G (IgG) occurs, leading to immune-mediated destruction and subepidermal blistering.2

Patients will present with new-onset, widespread eruptions of bullous lesions and urticarial plaques (FIGURE 2).2 Bullae are frequent on flexural surfaces such as the groin and axillae. Urticarial plaques are often pruritic. Oral involvement occurs in a minority of cases.2 Nikolsky’s sign—exfoliation of the outermost layer of skin upon slight rubbing—is absent in BP.

FIGURE 2

Fluid-filled vesicles and bullae on right anterior thigh

Differential: Other autoimmune and blistering skin conditions

Two additional pemphigoid subtypes are part of the differential when a patient presents with a blistering skin condition: pemphigoid gestationis and mucous membrane pemphigoid.2

Pemphigoid gestationis occurs exclusively during pregnancy and the puerperium, and is self-limited.

Mucous membrane pemphigoid is pathophysiologically similar to BP, but distributes preferentially on mucosal surfaces.

Pemphigus vulgaris, another autoimmune blistering skin disease, is characterized by sparse intact bullae. The mucous membrane is frequently involved, and there is a positive Nikolsky’s sign.

Additional conditions to keep in mind include epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous erythema multiforme, and bullous lupus erythematosus.

Biopsy confirms the Dx

A biopsy of a lesion confirms the diagnosis of BP and will help differentiate it from the conditions mentioned above.

Light microscopy shows eosinophil-rich subepidermal inflammatory infiltrate.2 Direct immunofluorescence displays the characteristic linear deposits of IgG and complement C3 along the basement membrane. Immunofluorescent testing on human salt-split skin may also be performed.

Drug induced? There is a subset of BP, called drug-induced BP, in which the onset of the disease is associated with the initiation of a medication. Furosemide is the most common culprit,3 although many additional medications have been described.

The pathophysiology of drug-induced BP is poorly understood.3 In some cases, discontinuation of the offending medication may halt progression and prevent recurrence. In other cases, the disease will progress to a chronic form regardless of medication discontinuation. It is reasonable to attempt medication discontinuation trials in cases where drug-induced BP is suspected.

Treat with corticosteroids

The traditional treatment of BP is high-dose oral corticosteroids. However, long-term use of systemic corticosteroids can cause significant morbidity and has been linked to an increased mortality rate in the elderly population.4 A potent topical corticosteroid, such as clobetasol propionate cream 10 to 30 g/d tapering over 4 months, or 40 g/d tapering over 12 months,5,6 is an effective alternative (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A).

Other options include methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine, niacinamide, doxycycline, intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange. These therapies are typically used in combination with corticosteroids, or after initial treatment failure. Evidence regarding their effectiveness is limited7 (SOR: B).

Although the disease is occasionally self-limited after the initial episode, most patients with BP will achieve clinical remission with medical intervention. Patients often experience recurrent outbreaks and require chronic use of immunosuppressive agents.

Our patient required ongoing care

Our patient was prescribed prednisone 80 mg/d PO in combination with topical clobetasol cream. Despite these treatments, the disease progressed. One week later, approximately 80% of his body surface was involved. He was admitted for fluid replacement and monitoring for infection.

Subsequent initiation of methotrexate, niacinamide, doxycycline, and topical clobetasol led to clinical remission. Unfortunately, the patient relapsed approximately 3 months later and required a second hospital stay.

In the ensuing months, the patient’s course was marked by frequent relapses and significant morbidity. Further treatment trials have included IV immunoglobulin, mycophenolate, and azathioprine.

CORRESPONDENCE

Casey Z. MacVane, MD, MPH, Department of Emergency Medicine, Maine Medical Center, 47 Bramhall Street, Portland, ME 04102; [email protected]

1. Langan SM, Smeeth L, Hubbard R, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris—incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a180.-

2. Yancey KB, Egan CA. Pemphigoid: clinical, histological, immunopathologic, and therapeutic considerations. JAMA. 2000;248:350-356.

3. Lee JJ, Downham TF, 2nd. Furosemide-induced bullous pemphigoid: case report and review of literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:562-564.

4. Rzany B, Partscht K, Jung M, et al. Risk factors for lethal outcome in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:903-908.

5. Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, et al. A comparison of oral and topical corticosteroids in patients with bullous pemphigoid. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:321-327.

6. Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, et al. A comparison of two regimens of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with bullous pemphigoid: a multicenter randomized study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1681-1687.

7. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD002292.

1. Langan SM, Smeeth L, Hubbard R, et al. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris—incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a180.-

2. Yancey KB, Egan CA. Pemphigoid: clinical, histological, immunopathologic, and therapeutic considerations. JAMA. 2000;248:350-356.

3. Lee JJ, Downham TF, 2nd. Furosemide-induced bullous pemphigoid: case report and review of literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:562-564.

4. Rzany B, Partscht K, Jung M, et al. Risk factors for lethal outcome in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:903-908.

5. Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, et al. A comparison of oral and topical corticosteroids in patients with bullous pemphigoid. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:321-327.

6. Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, et al. A comparison of two regimens of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with bullous pemphigoid: a multicenter randomized study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1681-1687.

7. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD002292.