User login

Quality and Quantity of the Elbow Arthroscopy Literature: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

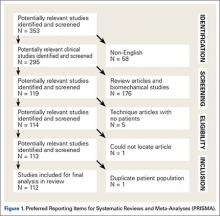

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

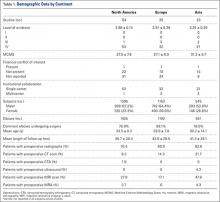

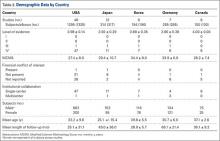

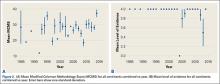

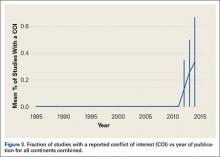

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

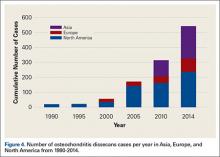

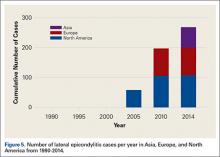

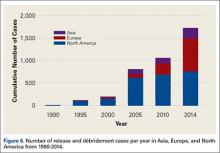

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

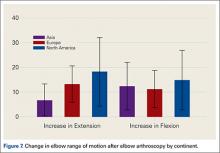

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

Although elbow arthroscopy was first described in the 1930s, it has become increasingly popular in the last 30 years.1 While initially considered as a tool for diagnosis and loose body removal, indications have expanded to include treatment of osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), treatment of lateral epicondylitis, fixation of fractures, and others.2-5 Miyake and colleagues6 found a significant improvement in range of motion, both flexion and extension, and outcome scores when elbow arthroscopy was used to remove impinging osteophytes. Babaqi and colleagues7 found significant improvement in pain, satisfaction, and outcome scores in 31 patients who underwent elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis refractory to nonsurgical management. The technical difficulty of the procedure, lower frequency of pathology amenable to arthroscopic intervention, and potential neurovascular complications make the elbow less frequently evaluated with the arthroscope vs other joints, such as the knee and shoulder.2,8,9

Geographic distribution of subjects undergoing elbow arthroscopy, the indications used, surgical techniques being performed, and their associated clinical outcomes have received little to no recognition in the peer-reviewed literature.10 Differences in the elbow arthroscopy literature include characteristics related to the patient (age, gender, hand dominance, duration of symptoms), study (level of evidence, number of subjects, number of participating centers, design), indication (lateral epicondylitis, loose bodies, olecranon osteophytes, OCD), surgical technique, and outcome. Evidence-based medicine and clinical practice guidelines direct surgeons in clinical decision-making. Payers investigate the cost of surgical interventions and the value that surgery may provide, while following trends in different surgical techniques. Regulatory agencies and associations emphasize subjective patient-reported outcomes as the primary outcome measured in high-quality trials. Thus, in discussion of complex surgical interventions such as elbow arthroscopy, it is important to characterize the studies, subjects, and surgeries across the world to understand the geographic similarities and differences to optimize care in this clinical situation.

The goal of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of elbow arthroscopy literature to identify and compare the characteristics of the studies published, the subjects analyzed, and surgical techniques performed across continents and countries to answer these questions: “Across the world, what demographic of patients are undergoing elbow arthroscopy, what are the most common indications for elbow arthroscopy, and how good is the evidence?” The authors hypothesized that patients who undergo elbow arthroscopy will be largely age <40 years, the most common indication for elbow arthroscopy will be a release/débridement, and the evidence for elbow arthroscopy will be poor. Also, no significant differences will exist in elbow arthroscopy publications, subjects, outcomes, and techniques based on continent/country of publication.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.11 Systematic review registration was performed using the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number, CRD42014010580; registration date, July 15, 2014).12 Two study authors independently conducted the search on June 23, 2014 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm used was: (elbow) AND arthroscopy) NOT shoulder) NOT knee) NOT ankle) NOT wrist) NOT hip) NOT dog) NOT cadaver). English language Level I-IV evidence (2012 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine13) clinical studies were eligible for inclusion into this study. Abstracts were ineligible for inclusion. All references in selected studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if they were missed during the initial search. Duplicate subject publications within separate unique studies were not reported twice. The study with longer duration follow-up, higher level of evidence, greater number of subjects, or more detailed subject, surgical technique, or outcome reporting was retained for inclusion. Level V evidence reviews, expert opinion articles, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, open elbow surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded.

All included patients underwent elbow arthroscopy for either intra- or extra-articular elbow pathology (ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis, lateral epicondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, post-traumatic contracture, osteonecrosis of the capitellum or radial head, osteoid osteoma, and others). There was no minimum follow-up duration or rehabilitation requirement. The study and subject demographic parameters that we analyzed included year of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and elbows, elbow dominance, gender, age, body mass index, diagnoses treated, type of anesthesia (block or general), and surgical positioning. Postoperative splint application and pain management, and whether a continuous passive motion machine was used and whether a drain was placed were recorded. Clinical outcome scores were DASH (Disability of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand), Morrey score, MEPS (Mayo Elbow Performance Score), Andrews-Carson score, Timmerman-Andrews score, LES (Liverpool Elbow Score), Tegner score, HSS (Hospital for Special Surgery Score), VAS (Visual Analog Scale), EFA (Elbow Functional Assessment), Short Form-12 (SF-12), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic (KJOC) Shoulder and Elbow Questionnaire, and MAESS (Modified Andrews Elbow Scoring System). Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), computed tomography arthrography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) data were extracted when available. Range of motion (flexion, extension, supination, and pronation) and grip strength data, both preoperative and postoperative, were extracted when available. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).14

Statistical Analysis

Study descriptive statistics were calculated. Continuous variable data were reported as weighted means ± weighted standard deviations. Categorical variable data were reported as frequencies with percentages. For all statistical analysis either measured and calculated from study data extraction or directly reported from the individual studies, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were compared using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Where applicable, study, subject, and surgical outcomes data were also compared using 2-sample and 2-proportion Z-test calculators with α .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups. To examine trends over time, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. For the purposes of analysis, the indications of “osteoarthritis,” “arthrofibrosis,” “loose body removal,” “ulnotrochlear osteoarthritis causing stiffness,” “post-traumatic contracture/stiffness,” and “post-operative elbow contracture” were combined into the indication “release and débridement.” For the 3 most common indications for arthroscopy (OCD, lateral epicondylitis, and release and débridement) data were combined into 5-year increments to overcome the smaller sample size within each of these categories, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine if number of reported cases covaried with year period. Within these 3 diagnoses, ANOVA analyses were performed to determine whether the number of cases differed between continents and countries.

Results

A total of 353 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 112 studies were included in the final analysis (Figure 1; 3093 subjects; 3168 elbows; 64% male; mean age, 34.9 ± 14.68 years). There was a mean of 33.4 ± 26.02 months of follow-up, and 75% of surgeries involved the dominant elbow (Table 1). Most studies were level IV evidence (94.6%), had a low MCMS (mean 28.1 ± 8.06; poor rating), and were single-center investigations (94.6%). Most studies did not report financial conflicts of interest (56.3%) (Tables 1 and 2). From 1985 through 2014, the number of publications significantly increased with time (P = .004) among all continents. The MCMS was unchanged over time (P = .247) (Figure 2A), as was the level of evidence (P = .094) (Figure 2B). Conflicts of interest significantly increased with time (P = .025) (Figure 3).

Among continents, North America published the largest number of studies (54), and had the largest number of patients (1395) and elbow surgeries (1425) (Table 1). The United States published the largest number of studies (43%). There were no significant differences between age (P = .331), length of follow-up (P = .403), MCMS (P = .123), and level of evidence (P = .288) between continents. Of the 32 studies that reported the use of preoperative MRI, studies from Asia reported significantly more MRI scans than those from other continents (P = .040); there were no other significant differences between continents in reference to preoperative imaging studies or other demographic information.

The most common surgical indications were OCD (Figure 4), lateral epicondylitis (Figure 5), and release and débridement (Figure 6, Table 3; all studies listed indications). The number of reported cases for these 3 indications significantly increased over time (OCD P = .005, lateral epicondylitis P = .044, release and débridement P = .042) but did not significantly differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

Thirty-two (28.6%) studies reported the use of outcome measures (16 different outcome scores were used by the included studies). Asia reported outcome measures in 9 of 23 studies (39%), Europe in 12 of 35 studies (34%) and North America in 11 of 54 (20%) of studies. The MEPS was the most frequently used outcome score in 9.8% of studies, followed by VAS for pain in 5.3% of cases. North American studies reported a significantly higher increase in extension after elbow arthroscopy than Asia (P = .0432) (Figure 7), with no differences in flexion (P = .699), pronation (P = .376), or supination (P = .408). No significant differences were observed between continents in the type of anesthesia chosen (general anesthesia [P = .94] or regional anesthesia [P = .85]). Asia and Europe performed elbow arthroscopy most frequently in the lateral decubitus position, while North American studies most often used the supine position (Table 4).

Twenty (17.9%) studies reported the use of a postoperative splint, 12 (10.7%) studies reported use of a drain, 2 (1.79%) studies reported use of a hinged elbow brace, 9 (8.03%) studies reported use of a continuous passive motion machine postoperatively, and 3 (2.68%) studies reported use of an indwelling axillary catheter for postoperative pain management. Of 130 reported surgical complications (4.1%), the most frequent complication was transient sensory ulnar nerve palsy (1.5%), followed by persistent wound drainage (.76%), and transient sensory radial nerve palsy (.38%). Other reported complications included infection (.22%), transient sensory palsy of the median nerve (.19%), heterotopic ossification (.13%), complete transection of the ulnar nerve (.10%), loose body formation (.06%), hematoma formation (.06%), transient sensory palsy of the posterior interosseous (.06%), or anterior interosseous nerve (.03%), and complete transection of the radial (.03%), or median nerve (.03%).

Discussion

Elbow arthroscopy is an evolving surgical procedure that is used to treat intra- and extra-articular pathologies of the elbow. Outcomes of elbow arthroscopy for certain conditions have generally been reported as good, with improvements seen in pain, functional scores, and range of motion.6,15-17 The authors’ hypotheses were mostly confirmed in that the average age of patients undergoing elbow arthroscopy was <40 years, release/débridement was one of the most common indications (along with lateral epicondylitis and OCD), and the general evidence for elbow arthroscopy was poor. Also, there were almost no differences between continents/countries related to patient indications, preoperative imaging, anesthesia choice, indications, postoperative protocols, and outcomes (although the number of studies that reported outcomes was low and could have skewed the results), with the exception of a higher number of preoperative MRI scans in Asia. Some of the notable findings of this study included: 1) the number of studies published on elbow arthroscopy is significantly increasing with time, despite a lack of improvement in the level of evidence; 2) the majority of studies on elbow arthroscopy do not report a surgical outcome score; and 3) the number of reported cases for the 3 most common indications significantly increased over time (OCD, P = .005; lateral epicondylitis, P = .044; release and débridement, P = .042) but did not differ between regions (P > .05 in all cases).

The indications for elbow arthroscopy have grown dramatically in the past 2 decades to include both intra- and extra-articular pathologies.18 Despite this increase in the number of indications for elbow arthroscopy, the study did not find a significant difference between countries/continents in the indications each used for elbow arthroscopy patients. There was a trend towards an increase in OCD cases in all continents, especially Asia (Figure 4), with time. Interestingly, while not statistically significant, there was variation among countries for surgical indications. In North America, removal of loose bodies accounts for 18% of patients, while in Europe this accounted for only 9% and in Asia for 1%. Post-traumatic stiffness was the indication for elbow arthroscopy in Europe in 19% of patients vs 7% in North America and 10% in Asia. In Asia, OCD accounts for 40% of arthroscopies, 7% in Europe, and 14% in North America (Figure 4) (Table 3).

This study demonstrated that the mean increase in elbow extension gained after surgery in North America was significantly greater when compared with studies from Asia, but the gain in flexion, pronation, and supination was similar across continents. The underlying cause of this difference in improvement in elbow extension between nations is unclear, although differences in diagnosis could account for some variation. This study did not examine differences in rehabilitation protocols, and certainly, it is plausible that protocol variations by country could account for some discrepancy. Furthermore, differences in functional needs may vary by continent and could have driven this result.

This study found no routine reporting of outcome scores by elbow arthroscopy studies from any continent, and that when outcome scores are reported, there is substantial inconsistency with regard to the actual scoring system used. No continent reported outcome scores in more than 40% of the studies published from that area, and the variation of outcome scores used, even from a single region, was large. This makes comparing clinical outcomes between studies difficult, even when performing identical procedures for identical indications, because there is no standardized method of reporting outcomes. To allow comparison of studies and generalizability of the results to different populations, a more standardized approach to outcome reporting needs to be instituted in the elbow arthroscopy literature. To date, there is no standardized score that has been validated for reporting clinical outcomes after elbow arthroscopy.19 Hence, it is not surprising that there were 16 different outcome scores reported throughout the 112 studies analyzed in this review, with the most frequent score, the MEPS, reported in a total of 10 studies. As medicine moves towards pay scales that are based on patient outcomes, it will become more important to define a clear outcome score that can be used to assess these patients, and reliably report scores. This will allow comparison of patients across nations to determine the best surgical treatment for different clinical problems. A validation study comparing these outcome scores to determine which score best summarizes the patient’s level of pain and function after surgery would be beneficial, because this could identify 1 score that could be standardized to allow comparison among reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Despite having 2 authors search independently for studies, some studies could have been missed during the search process, introducing possible selection bias. Including only published studies could have introduced publication bias. Numerous studies did not report all the variables the authors examined. This could have skewed some results, and had additional variables been reported, could have altered the data to show significant differences in some measured variables. Because this study did not compare outcome measures for varying pathologies, conclusions cannot be drawn on the best treatment options for different indications. Case reports could have lowered the MCMS score and the average in studies reporting outcomes. Furthermore, the poor quality of the underlying data used in this study could limit the validity/generalizability of the results because this is a systematic review, and its level of evidence is only as high as the studies it includes. Because the primary aim was to report on demographics, this study did not examine concomitant pathology at the time of surgery or rehabilitation protocols.

Conclusion

The quantity, but not the quality, of arthroscopic elbow publications has significantly increased over time. Most patients undergo elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, OCD, and release and débridement. Pathology and indications do not appear to differ geographically with more men undergoing elbow arthroscopy than women.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

1. Khanchandani P. Elbow arthroscopy: review of the literature and case reports. Case Rep Orthop. 2012;2012:478214.

2. Dodson CC, Nho SJ, Williams RJ 3rd, Altchek DW. Elbow arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(10):574-585.

3. Takahara M, Mura N, Sasaki J, Harada M, Ogino T. Classification, treatment, and outcome of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2 Pt 1):47-62.

4. Kelly EW, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A(1):25-34.

5. Rajeev A, Pooley J. Lateral compartment cartilage changes and lateral elbow pain. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):37-40.

6. Miyake J, Shimada K, Oka K, et al. Arthroscopic debridement in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the elbow, based on computer simulation. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(2):237-241.

7. Babaqi AA, Kotb MM, Said HG, AbdelHamid MM, ElKady HA, ElAssal MA. Short-term evaluation of arthroscopic management of tennis elbow; including resection of radio-capitellar capsular complex. J Orthop. 2014;11(2):82-86.

8. Gay DM, Raphael BS, Weiland AJ. Revision arthroscopic contracture release in the elbow resulting in an ulnar nerve transection: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1246-1249.

9. Haapaniemi T, Berggren M, Adolfsson L. Complete transection of the median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):784-787.

10. Yeoh KM, King GJ, Faber KJ, Glazebrook MA, Athwal GS. Evidence-based indications for elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(2):272-282.

11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

12. PROSPERO. International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews. The University of York CfRaDP-Iprosr-v. 2013 [cited 2014]. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed March 17, 2016.

13. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine - levels of evidence (March 2009). Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Web site. http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009/. Accessed July 6, 2016.

14. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderόn S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

15. Jones GS, Savoie FH 3rd. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(3):277-283.

16. O’Brien MJ, Lee Murphy R, Savoie FH 3rd. A preliminary report of acute and subacute arthroscopic repair of the radial ulnohumeral ligament after elbow dislocation in the high-demand patient. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(6):679-687.

17. Rhyou IH, Kim KW. Is posterior synovial plica excision necessary for refractory lateral epicondylitis of the elbow? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):284-290.

18. Jerosch J, Schunck J. Arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis: indication, technique and early results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(4):379-382.

19. Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, de Visser E. Patient-Reported Outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:117.

Predicting and Preventing Injury in Major League Baseball

Major league baseball (MLB) is one of the most popular sports in the United States, with an average annual viewership of 11 million for the All-Star game and almost 14 million for the World Series.1 MLB has an average annual revenue of almost $10 billion, while the net worth of all 30 MLB teams combined is estimated at $36 billion; an increase of 48% from 1 year ago.2 As the sport continues to grow in popularity and receives more social media coverage, several issues, specifically injuries to its players, have come to the forefront of the news. Injuries to MLB players, specifically pitchers, have become a significant concern in recent years. The active and extended rosters in MLB include 750 and 1200 athletes, respectively, with approximately 360 active spots taken up by pitchers.3 Hence, MLB employs a large number of elite athletes within its organization. It is important to understand not only what injuries are occurring in these athletes, but also how these injuries may be prevented.

Epidemiology

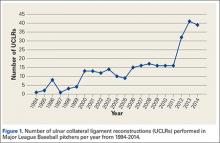

Injuries to MLB players, specifically pitchers, have increased over the past several years.4 Between 2005 and 2008, there was an overall increase of 37% in total number of injuries, with more injuries occurring in pitchers than any other position.5 While position players are more likely to sustain an injury to the lower extremity, pitchers are more likely to sustain an injury to the upper extremity.5 The month with the most injuries to MLB players was April, while the fewest number of injuries occurred in September.5 One injury that has been in the spotlight due to its dramatically increasing incidence is tear of the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL). Several studies have shown that the number of pitchers undergoing ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction (UCLR), commonly known as Tommy John surgery, has significantly increased over the past 20 years (Figure 1).4,6 Between 25% to 33% of all MLB pitchers have undergone UCLR.

While the number of primary UCLR in MLB pitchers has become a significant concern, an even more pressing concern is the number of pitchers undergoing revision UCLR, as this number has increased over the past several years.7 Currently, there is some debate as to how to best address the UCL during primary UCLR (graft type, exposure, treatment of the ulnar nerve, and graft fixation methods) because no study has shown one fixation method or graft type to be superior to others. Similarly, no study has definitively proven how to best manage the ulnar nerve (transpose in all patients, only transpose if preoperative symptoms of numbness/tingling, subluxation, etc. exist). Unfortunately, the results following revision UCLR are inferior to those following primary UCLR.4,7,8 Hence, given this information, it is imperative to both determine and implement strategies aimed at minimizing the need for revision.

Risk Factors for Injury

Although MLB has received more media attention than lower levels of baseball competition, there is relatively sparse evidence surrounding injury risk factors among MLB players. The majority of studies performed have evaluated risk factors for injury in younger baseball athletes (adolescent, high school, and college). The number of athletes at these lower levels sustaining injuries has increased over the past several years as well.9 Several large prospective studies have evaluated risk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball players. The risk factors include pitching year-round, pitching more than 100 innings per year, high pitch counts, pitching for multiple teams, geography, pitching on consecutive days, pitching while fatigued, breaking pitches, higher elbow valgus torque, pitching with higher velocity, pitching with supraspinatus weakness, and pitching with a glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD).10-17 The large majority of these risk factors are essentially part of a pitcher’s cumulative work, which consists of number of games pitched, total pitches thrown, total innings pitched, innings pitched per game, and pitches thrown per game. One prior study has evaluated cumulative work as a predictor for injury in MLB pitchers.18 While there were several issues with the study methodology, the authors found no correlation between a MLB pitcher’s cumulative work and risk for injury.

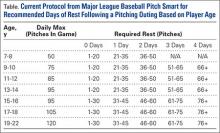

Given our current understanding of repetitive microtrauma as the pathophysiology behind these injuries, it remains unclear why cumulative work would be predictive of injury in youth pitchers but not in MLB pitchers.16 Several potential reasons exist as to why cumulative work may relate to risk of injury in youth pitchers and not MLB pitchers. Achieving MLB status may infer the element of natural selection based on technique and talent that supersedes the effect of “cumulative trauma” in many players. In MLB pitchers, cumulative work is closely monitored. In addition, these players are only playing for a single team and are not pitching competitively year-round, while many youth players play for multiple teams and may pitch year-round. To combat youth injuries, MLB Pitch Smart has developed recommendations on pitch counts and days of rest for pitchers of all age groups (Table).19 While data do not yet exist to clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of these guidelines, given the risk factors previously mentioned, it seems that these recommendations will show some reduction in youth injuries in years to come.

Some studies have evaluated anatomic variation among pitchers as a risk factor for injury. Polster and colleagues20 performed computed tomography (CT) scans with 3-dimensional reconstructions on the humeri of both the throwing and non-throwing arms of 25 MLB pitchers to determine if humeral torsion was related to the incidence and severity of upper extremity injuries in these athletes. The authors defined a severe injury as those which kept the player out for >30 days. Overall, 11 pitchers were injured during the 2-year study period. There was a strong inverse relationship between torsion and injury severity such that lower degrees of dominant humeral torsion correlated with higher injury severity (P = .005). However, neither throwing arm humeral torsion nor the difference in torsion between throwing and non-throwing humeri were predictive of overall injury incidence. While this is a nonmodifiable risk factor, it is important to understand how the pitcher’s anatomy plays a role in risk of injury.20 Understanding nonmodifiable risk factors may be helpful in the future to risk stratify, prognosticate, and modulate modifiable risk factors such as cumulative work.

Elbow

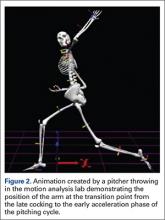

Injuries to the elbow have become more common in recent years amongst MLB players, although the literature regarding risk factors for elbow injuries is sparse.4,6 Wilk and colleagues21 performed a prospective study to determine if deficits in glenohumeral passive range of motion (ROM) increased the risk of elbow injury in MLB pitchers. Between 2005-2012, the authors measured passive shoulder ROM of both the throwing and non-throwing shoulder of 296 major and minor league pitchers and followed them for a median of 53.4 months. In total, 38 players suffered 49 elbow injuries and required 8 surgeries, accounting for a total of 2551 days spent on the disabled list (DL). GIRD and external rotation insufficiency were not correlated with elbow injuries. However, pitchers with deficits of >5° in total rotation between the throwing and non-throwing shoulders had a 2.6 times greater risk for injury (P = .007) and pitchers with deficits of ≥5° in flexion of the throwing shoulder compared to the non-throwing shoulder had a 2.8 times greater risk for injury (P = .008).21 Prior studies have demonstrated trends towards increased elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers with an increase in both elbow valgus torque as well as shoulder external rotation torque; maximum pitch velocity was also shown to be an independent risk factor for elbow injury in professional baseball pitchers.10,11 These injuries typically occur during the late cocking/early acceleration phase of the pitching cycle, when the shoulder and elbow experience the most significant force of any point in time during a pitch (Figure 2).17 At our institution, there are several ongoing studies to determine the relative contributions of pitch velocity, number, and type to elbow injury rates. Prospective studies are also ongoing at other institutions.

Shoulder

Shoulder injuries are one of the most common injuries seen in MLB players, specifically pitchers. Similar to the prior study, Wilk and colleagues22 recently performed a prospective study to determine if passive ROM of the glenohumeral joint in MLB pitchers was predictive of shoulder injury or shoulder surgery. As in the previous study, the authors’ measured passive shoulder ROM of the throwing and non-throwing shoulder of 296 major and minor league pitchers during spring training between 2005-2012 and obtained an average follow-up of 48.4 months. The authors found a total of 75 shoulder injuries and 20 surgeries among 51 pitchers (17%) that resulted in 5570 days on the DL. While total rotation deficit, GIRD, and flexion deficit had no relation to shoulder injury or surgery, pitchers with <5° greater external rotation in the throwing shoulder compared to the non-throwing shoulder were more than 2 times more likely to be placed on the DL for a shoulder injury (P = .014) and were 4 times more likely to require shoulder surgery (P = .009).22 The authors concluded that an insufficient side-to-side difference in external rotation of the throwing shoulder increased a pitcher’s likelihood of shoulder injury as well as surgery.

Other

One area that has not received as much attention as repetitive use injuries of the shoulder and elbow is acute collision injuries. Collision injuries include concussions, hyperextension injuries to the knees, shoulder dislocations, fractures of the foot and ankle, and others.23 Catchers and base runners during scoring plays are at a high risk for collision injury. Recent evidence has shown that catchers average approximately 2.75 collision injuries per 1000 athletic exposures (AE), accounting for an average of 39.1 days on the DL per collision injury.23 However, despite these collision injuries, catchers spend more time on the DL from non-collision injuries (specifically shoulder injuries requiring surgical intervention), as studies have shown 19 different non-collision injuries that accounted for >100 days on the DL for catchers compared to no collision injuries that caused a catcher to be on the DL for >100 days.23 The position of catcher is not an independent risk factor for sustaining an injury in MLB players.5

Preventative Measures

Given that recent evidence has identified certain modifiable risk factors, largely regarding shoulder ROM, for injuries to MLB pitchers, it stands to reason that by modifying these risk factors, the number of injuries to MLB pitchers can be decreased.21,22 However, to the authors’ knowledge, there have been no studies in the current literature that have clearly demonstrated the ability to prevent injuries in MLB players. Based on the prior studies, it seems logical that lowering peak pitch velocity and ensuring proper shoulder ROM would help prevent injuries in MLB players, but this remains speculative. Stretching techniques that have been shown to increase posterior shoulder soft tissue flexibility, including sleeper stretches and modified cross-body stretches, as well as closely monitoring ROM may be helpful in modifying these risk factors.24-26

Although the number of collision injuries is significantly lower than non-collision repetitive use injuries, MLB has implemented rule changes in recent years to prevent injuries to catchers and base runners alike.23,27 The rule change, which went into effect in 2014, prohibits catchers from blocking home plate unless they are actively fielding the ball or are in possession of the ball. Similarly, base runners are not allowed to deviate from their path to collide with the catcher while attempting to score.27 However, no study has analyzed whether this rule change has decreased the number of collision injuries sustained by MLB catchers, so it is unclear if this rule change has accomplished its goal.

Outcomes Following Injuries

One of the driving forces behind injury prevention in MLB players is to allow players to reach and maintain their full potential while minimizing time missed because of injury. Furthermore, as with any sport, the clinical outcomes and return to sport (RTS) rates for MLB players following injuries, especially injuries requiring surgical intervention, can be improved.4,28,29 Several studies have evaluated MLB pitchers following UCLR and have shown that over 80% of pitchers are able to RTS following surgery.4,30 When critically evaluated in multiple statistical parameters upon RTS, these players perform better in some areas and worse in others.4,30 However, the results following revision UCLR are not as encouraging as those following primary UCLR in MLB pitchers.7 Following revision UCLR, only 65% of pitchers were able to RTS, and those who were able to RTS pitched, on average, almost 1 year less than matched controls.7 Unfortunately, results following surgeries about the shoulder in MLB players have been worse than those about the elbow. Cohen and colleagues28 reported on 22 MLB players who underwent labral repair of the shoulder and found that only 32% were able to return to the same or higher level following surgery, while over 45% retired from baseball following surgery. Hence, it is imperative these injuries are prevented, as the RTS rate following treatment is less than ideal.

Future Directions